↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Object detection models often struggle with complex scenes and ambiguous objects. Existing methods, such as using large backbones, often face computational limitations and performance bottlenecks. This research addresses these issues by proposing a new paradigm.

The proposed Frozen-DETR uses frozen foundation models as a plug-and-play module to boost object detection performance. This is done by integrating the class token (representing the global image context) and patch tokens (providing fine-grained details) from frozen foundation models into a query-based detector. Experiments show significant improvements in accuracy across several datasets, demonstrating the effectiveness and efficiency of this novel approach. This is particularly important for addressing challenges like class imbalance and open-vocabulary scenarios, which highlight the method’s versatility and significant contributions to the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to enhance object detection models by leveraging the power of frozen foundation models. This method significantly improves detection accuracy without the computational burden of fine-tuning large foundation models, opening new avenues for research in efficient and high-performing object detection. The results showcase its effectiveness across various datasets and settings, including challenges like class imbalance and open vocabulary detection, establishing its potential for broader applications and impact on computer vision.

Visual Insights#

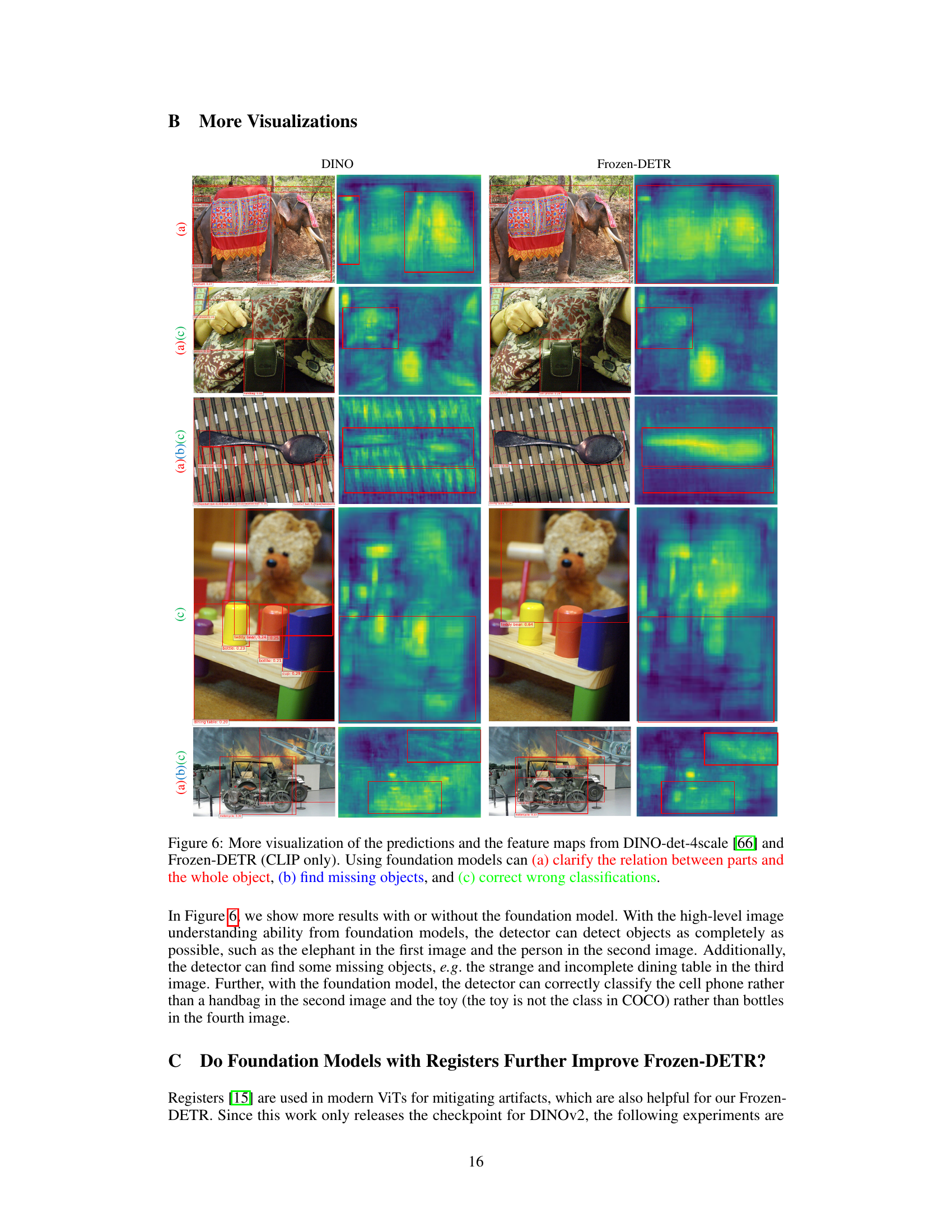

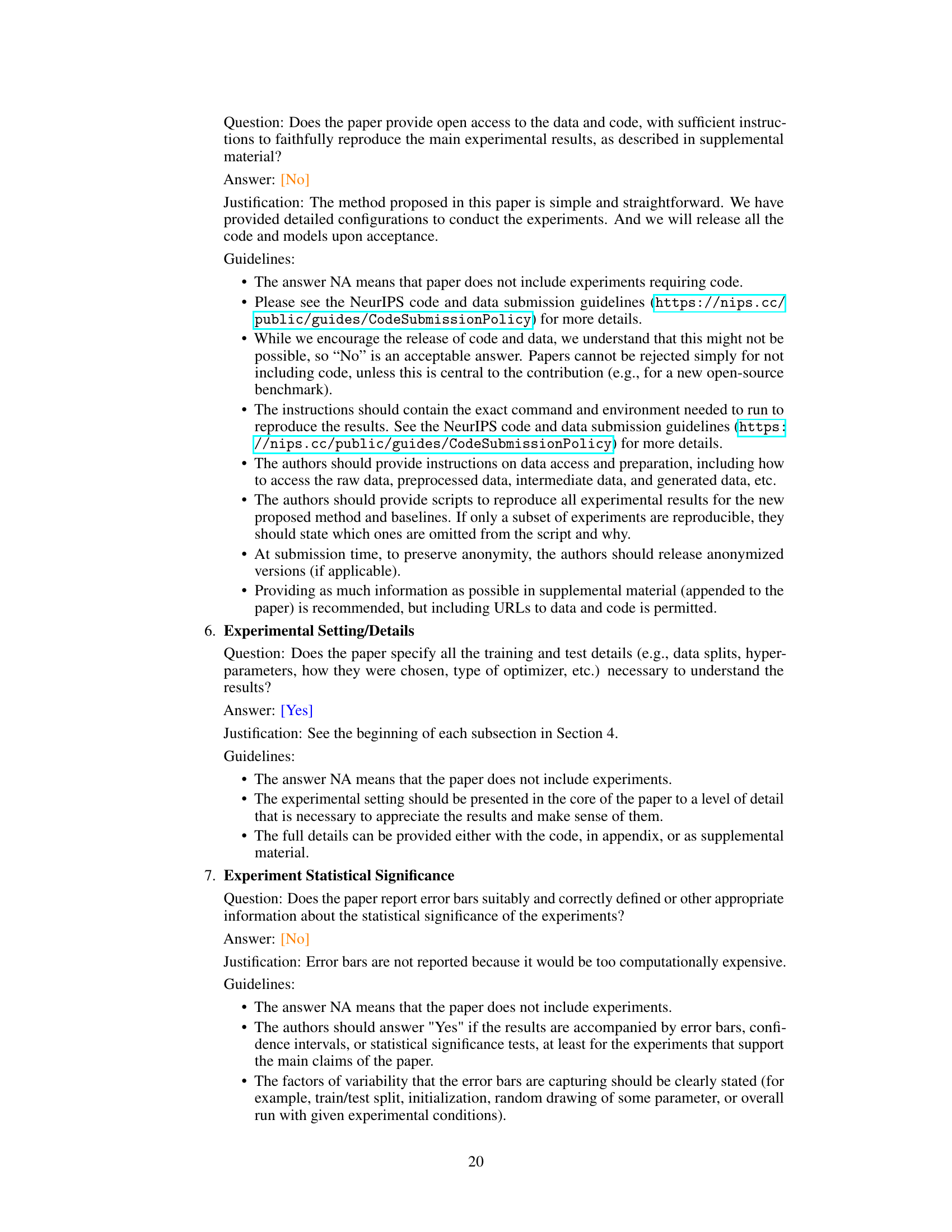

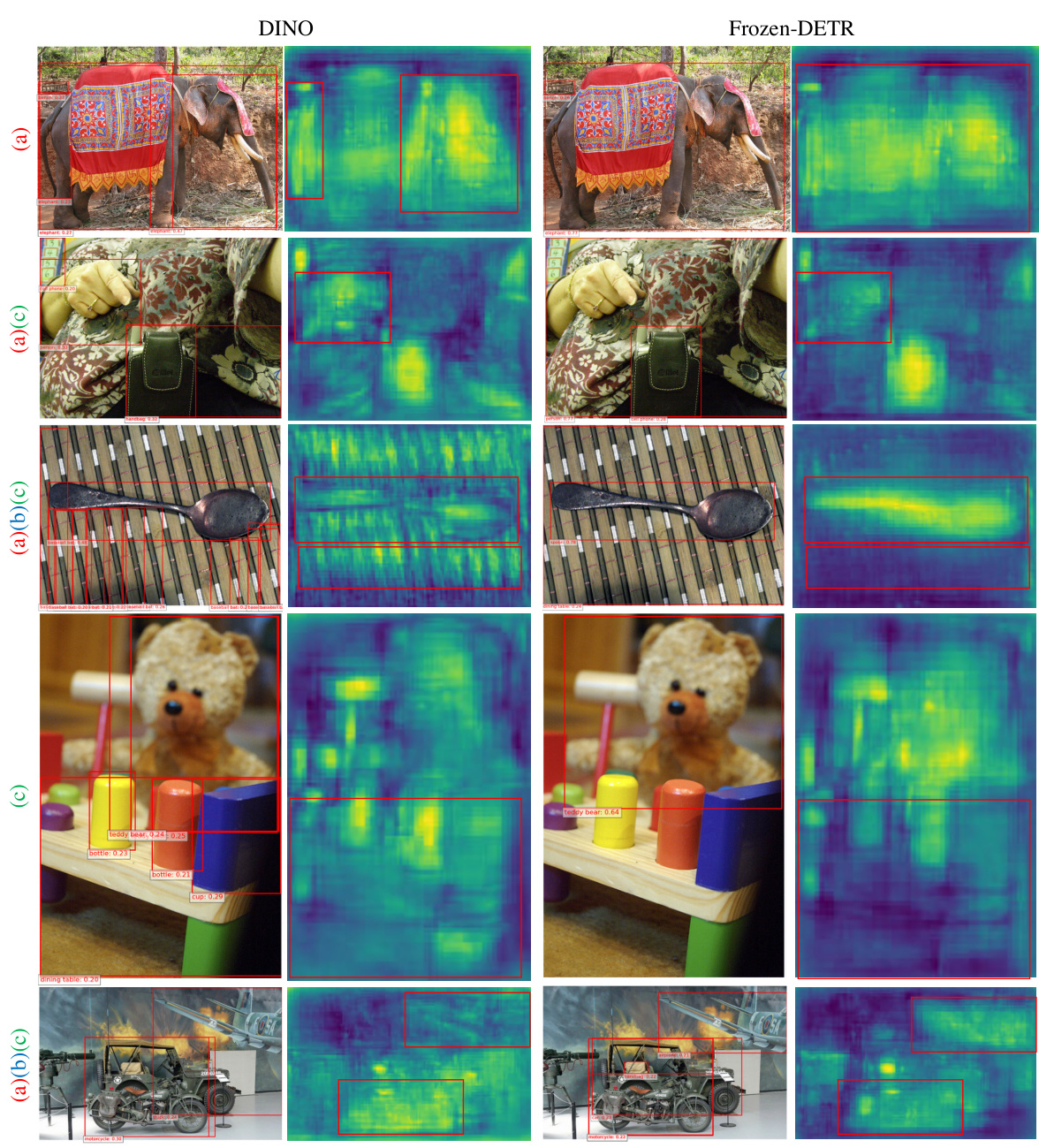

This figure shows three examples of how a deeper understanding of the image context improves object detection results. (a) clarifies the relationship between object parts and the whole, addressing the issue of detecting parts of occluded objects. (b) demonstrates that knowing the co-occurrence of objects can help find missing or occluded objects. (c) highlights how understanding the image context aids in distinguishing similar objects, reducing misclassifications. Red and green boxes differentiate incorrect and correct predictions.

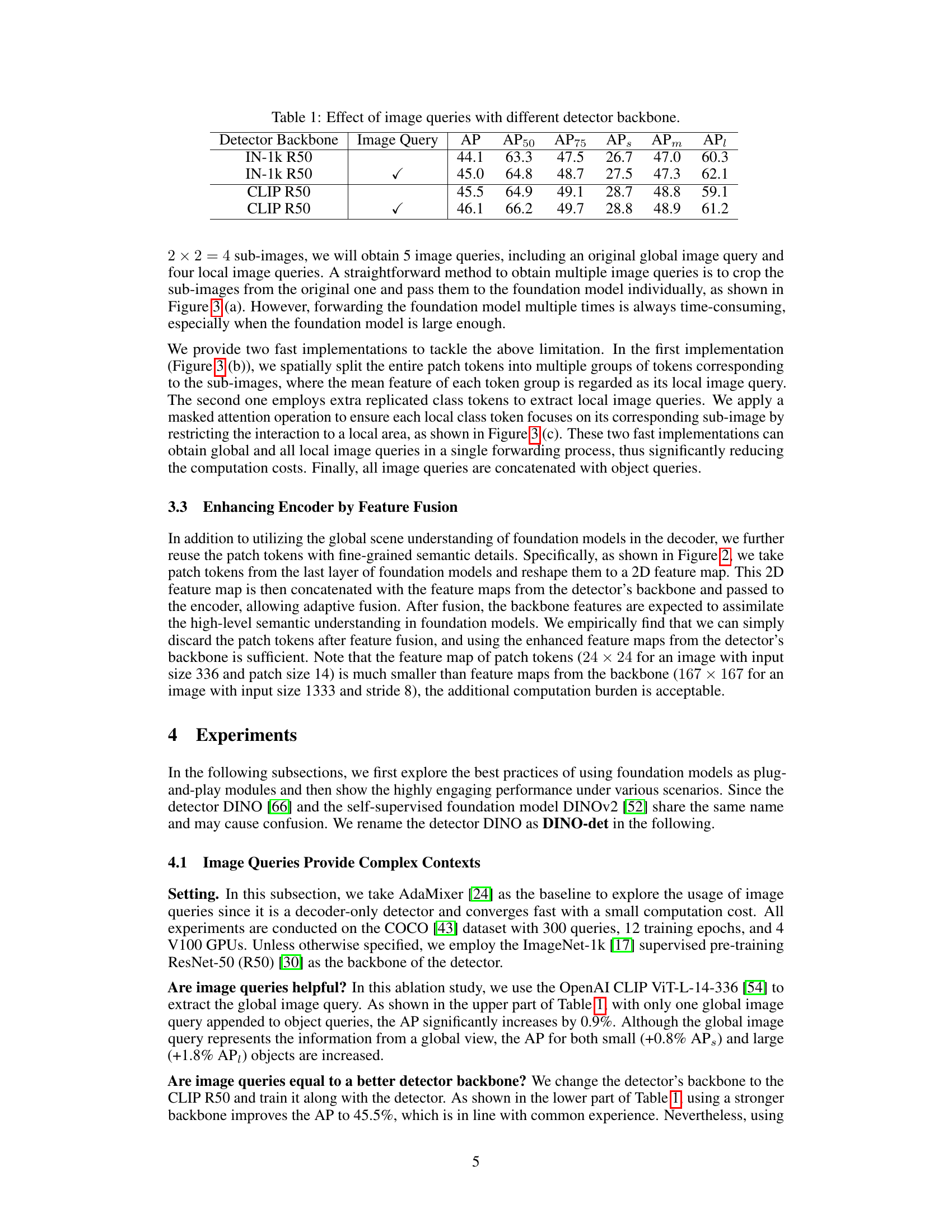

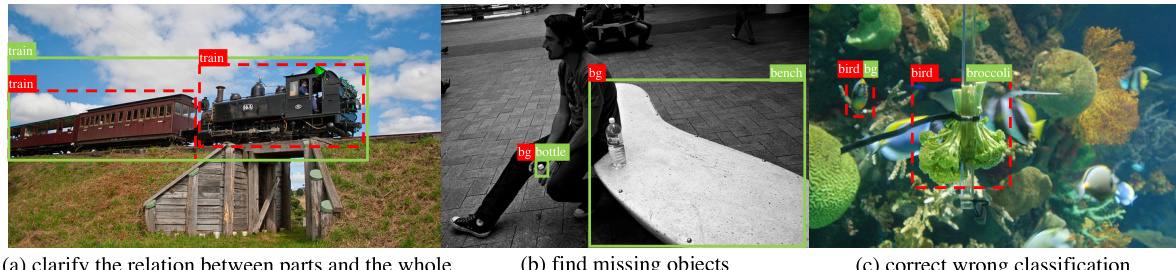

This table presents an ablation study on the impact of adding image queries to different detector backbones (ImageNet-1k R50 and CLIP R50). It shows the Average Precision (AP) and its variations (AP50, AP75, etc.) with and without the addition of image queries. The results demonstrate that integrating image queries improves the model’s performance across various metrics, regardless of the backbone used.

In-depth insights#

Frozen-DETR: A Deep Dive#

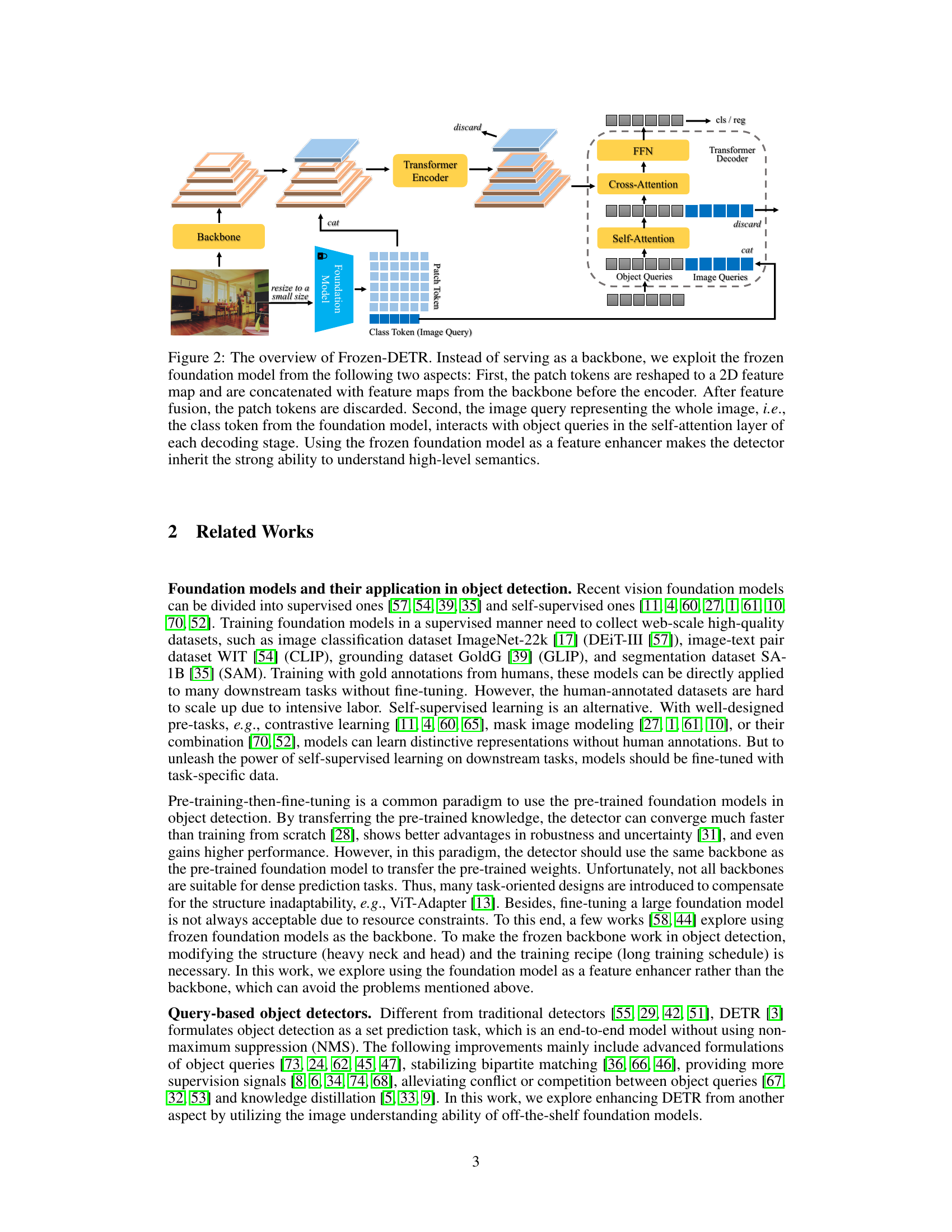

Frozen-DETR offers a novel approach to object detection by integrating pre-trained foundation models as feature enhancers, not as backbones. This avoids architectural constraints and the need for extensive fine-tuning, making it a more versatile and efficient method. The core innovation lies in using the class token as an “image query,” providing a rich contextual understanding to the detector’s decoder, and integrating patch tokens to enrich encoder features. This plug-and-play methodology significantly improves performance while maintaining computational efficiency. The effectiveness is demonstrated through substantial AP gains on various datasets, showcasing strong generalization and open-vocabulary capabilities. However, future work could explore handling more challenging scenarios and further optimize resource usage.

Foundation Model Fusion#

Foundation model fusion in computer vision involves combining the outputs or representations from multiple pre-trained foundation models to improve performance on downstream tasks. The core idea is that different models excel at capturing various aspects of image data, so combining them can leverage these strengths for a more holistic understanding. This approach offers advantages over single-model architectures, particularly for complex tasks like object detection. Fusion strategies can range from simple concatenation to more sophisticated techniques like attention mechanisms or cross-modal transformations. Key design choices involve selecting appropriate foundation models, determining the optimal fusion method, and managing computational costs. Successful fusion hinges on aligning model outputs and resolving potential conflicts between differing representations. Ultimately, the efficacy depends heavily on data and task specificity. Effective fusion strategies can boost accuracy and robustness, but careful design and evaluation are critical for optimal results.

Image Query Enhancers#

The concept of ‘Image Query Enhancers’ in the context of object detection using vision transformers is a novel approach to boost performance. It leverages the power of pre-trained foundation models, specifically their ability to extract high-level image understanding, without requiring extensive fine-tuning. Instead of replacing the backbone, the foundation model acts as a plug-and-play module, enhancing the existing detector’s capabilities. This is achieved by incorporating the class token (as an ‘image query’) into the detector’s decoder, providing a rich global context for object queries. Furthermore, patch tokens from the foundation model are fused with the detector’s encoder features, enriching low-level features with semantic information. This modular approach avoids architectural constraints and allows for flexible integration with various detector designs, offering a significant advantage in terms of efficiency and performance gains. The effectiveness of this method is demonstrated by the substantial improvement in detection accuracy observed in the experiments.

Ablation Studies & Results#

An effective ‘Ablation Studies & Results’ section would systematically dissect the proposed model’s components, evaluating their individual contributions. Key aspects like image queries, feature fusion, and the choice of foundation model should each have dedicated ablation experiments. Results should be presented clearly, ideally with tables and graphs showing quantitative performance metrics (e.g., AP, AP50, etc.) for different configurations. A thorough analysis should discuss the impact of each component on the overall model performance, explaining why certain design choices were superior to alternatives. The discussion should highlight unexpected findings and offer insightful interpretations of the results, ultimately strengthening the paper’s contribution and robustness.

Limitations & Future Work#

The section on limitations should thoroughly address the model’s shortcomings. A crucial aspect is acknowledging the reliance on pre-trained foundation models, as their inherent biases and limitations directly impact the detector’s performance. The dependence on specific foundation models should be discussed, and the potential for improvements with alternative models explored. Computational costs, especially during training with large foundation models, represent another critical limitation that demands careful consideration. The evaluation methodology should be critiqued, acknowledging any potential biases or limitations in the chosen datasets or metrics. Finally, future work could involve exploring different foundation model architectures, investigating more robust training strategies, and extending the approach to handle different object detection tasks and datasets. Addressing these limitations would enhance the overall impact and reliability of the proposed method.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure illustrates the Frozen-DETR architecture. It highlights how the frozen foundation model enhances the detector in two ways: 1) By incorporating the class token (image query) to the decoder’s self-attention mechanism, providing a richer global context to object queries, and 2) By fusing the reshaped patch tokens with the backbone features in the encoder to enrich local feature representations. The foundation model isn’t trained, but acts as a plug-and-play module to improve performance.

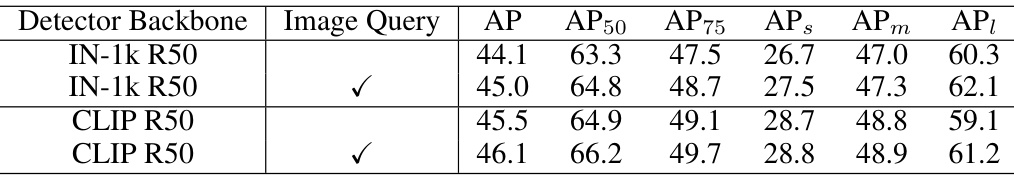

This figure illustrates three different methods for extracting image queries from a foundation model for use in object detection. Method (a) involves dividing the image into sub-images, processing each sub-image through the foundation model separately, and then using the class token of each sub-image as an individual image query. Method (b) takes a faster approach by calculating the mean feature vector of all patch tokens corresponding to each sub-image. Lastly, Method (c) uses replicated class tokens, each one restricted via an attention mask that focuses the class token on a specific sub-image. The figure highlights the trade-off between accuracy (more sub-images, more passes) and speed/efficiency (fewer passes).

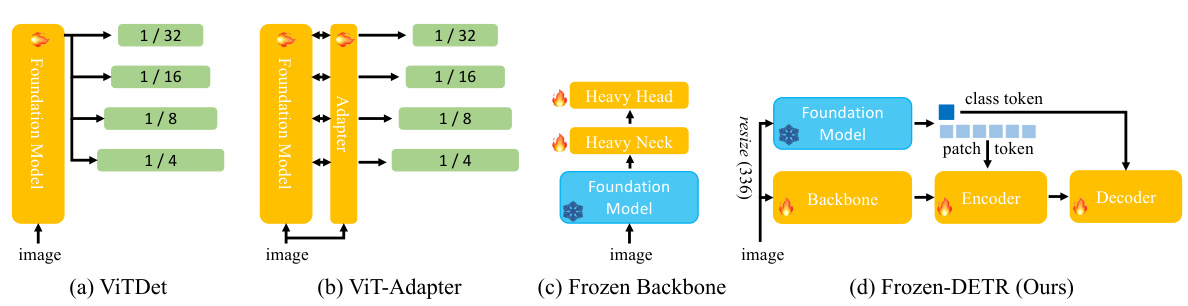

This figure compares four different methods of using pre-trained vision foundation models in object detection. (a) shows ViTDet, which fully fine-tunes the entire foundation model. (b) illustrates ViT-Adapter, which adds task-specific adapters to a pre-trained model and fine-tunes both the model and the adapters. (c) depicts the use of a frozen foundation model as the backbone, requiring a heavy neck and head to compensate for the lack of trainable parameters. Finally, (d) showcases Frozen-DETR, which uses a frozen foundation model as a plug-and-play module, keeping the foundation model frozen during training and using a smaller input image size.

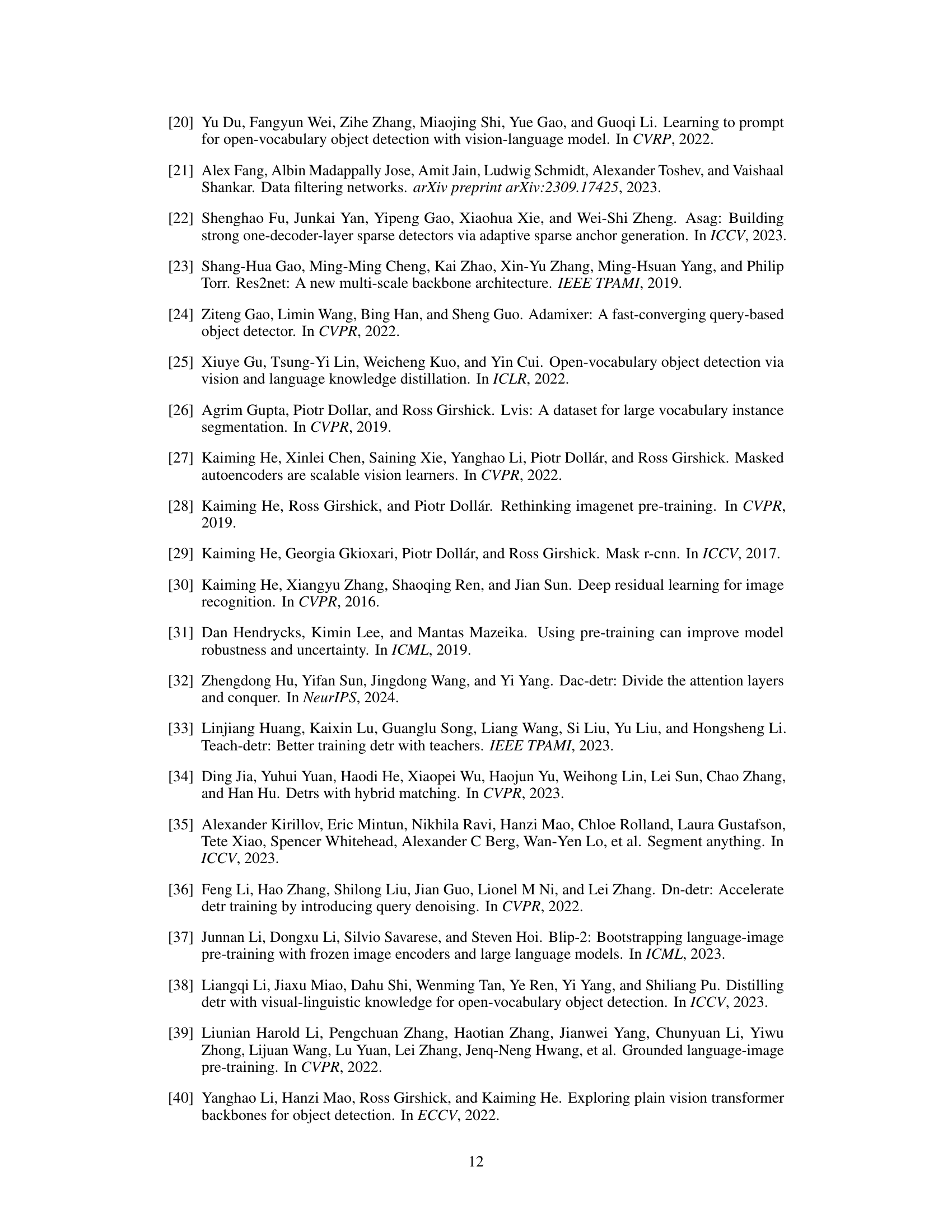

This figure shows a comparison of the detection results and feature maps between DINO and Frozen-DETR. The left column shows the DINO model results, while the right column shows the Frozen-DETR model results. The top row shows a picture of an elephant. Both models successfully identified the elephant. However, DINO only detected one elephant while Frozen-DETR correctly identified two elephants. The second row shows a picture of a cell phone. Again, both models successfully detected the cell phone. However, DINO only detected one cell phone while Frozen-DETR correctly identified two cell phones. The third row shows a picture of a spoon. Both models successfully detected the spoon. However, DINO only detected one spoon while Frozen-DETR correctly identified two spoons. The bottom row shows a picture of a teddy bear. Both models successfully detected the teddy bear. However, DINO only detected one teddy bear while Frozen-DETR correctly identified two teddy bears. The visualization of the feature maps show that the Frozen-DETR model produces more continuous and complete activation of objects than DINO. This shows that the foundation model can improve the performance of the detector by providing richer context information and finer-grained details.

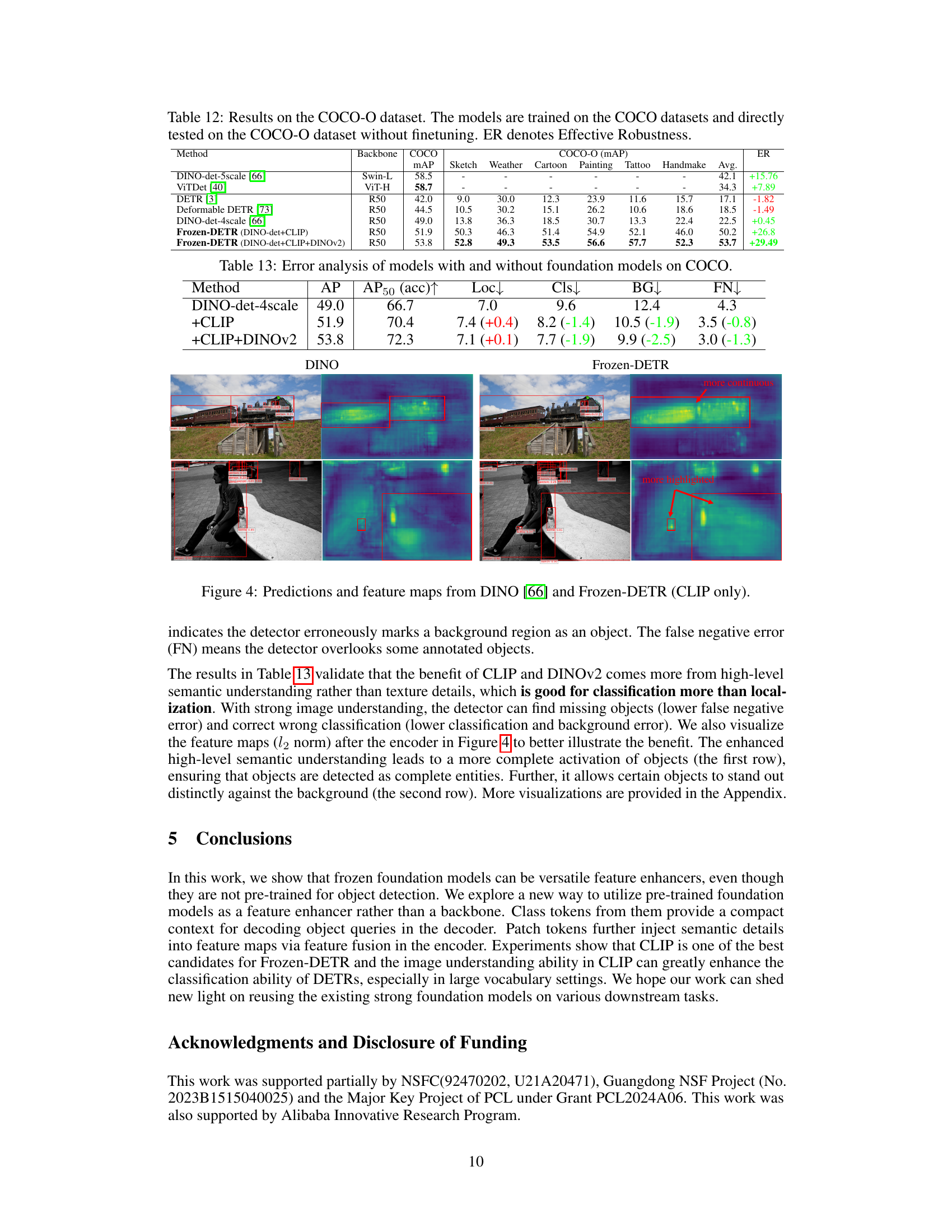

More on tables

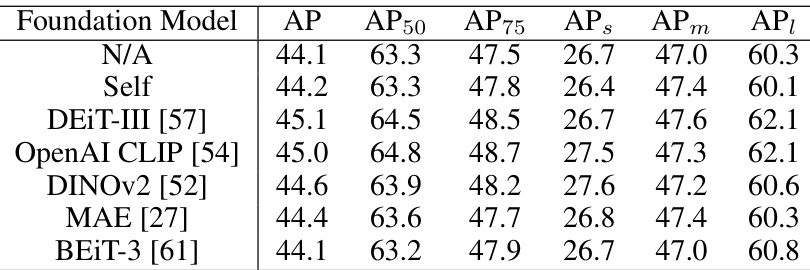

This table presents the results of an ablation study comparing different foundation models used for extracting image queries. The goal is to determine which pre-trained model provides the best high-level image understanding for enhancing object detection. The models compared include several popular vision transformers trained using both supervised and self-supervised methods. The table shows that OpenAI CLIP and DEIT-III perform comparably well, outperforming other models.

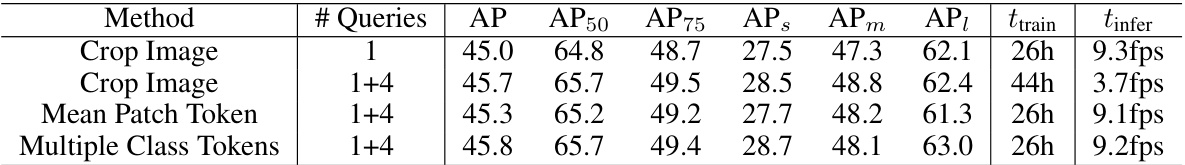

This table presents the ablation study on different methods of extracting image queries. The methods compared are: 1) cropping sub-images and feeding them into the foundation model individually to get class tokens as image queries; 2) using mean features of patch tokens as image queries; 3) using multiple class tokens as image queries constrained by attention masks. The table shows the AP, AP50, AP75, APs, APm, API, training time, and inference speed for each method with one image query or multiple image queries (1+4).

This table presents the ablation study results on feature fusion within the encoder. It compares the performance of the baseline model (no foundation model) against three variations: adding 5 image queries, incorporating patch tokens into the encoder, and adding patch tokens to both the encoder and the decoder. The results are evaluated using metrics such as AP, AP50, AP75, APs, APm, and APl, along with memory usage (Mem), GFLOPs, and FPS.

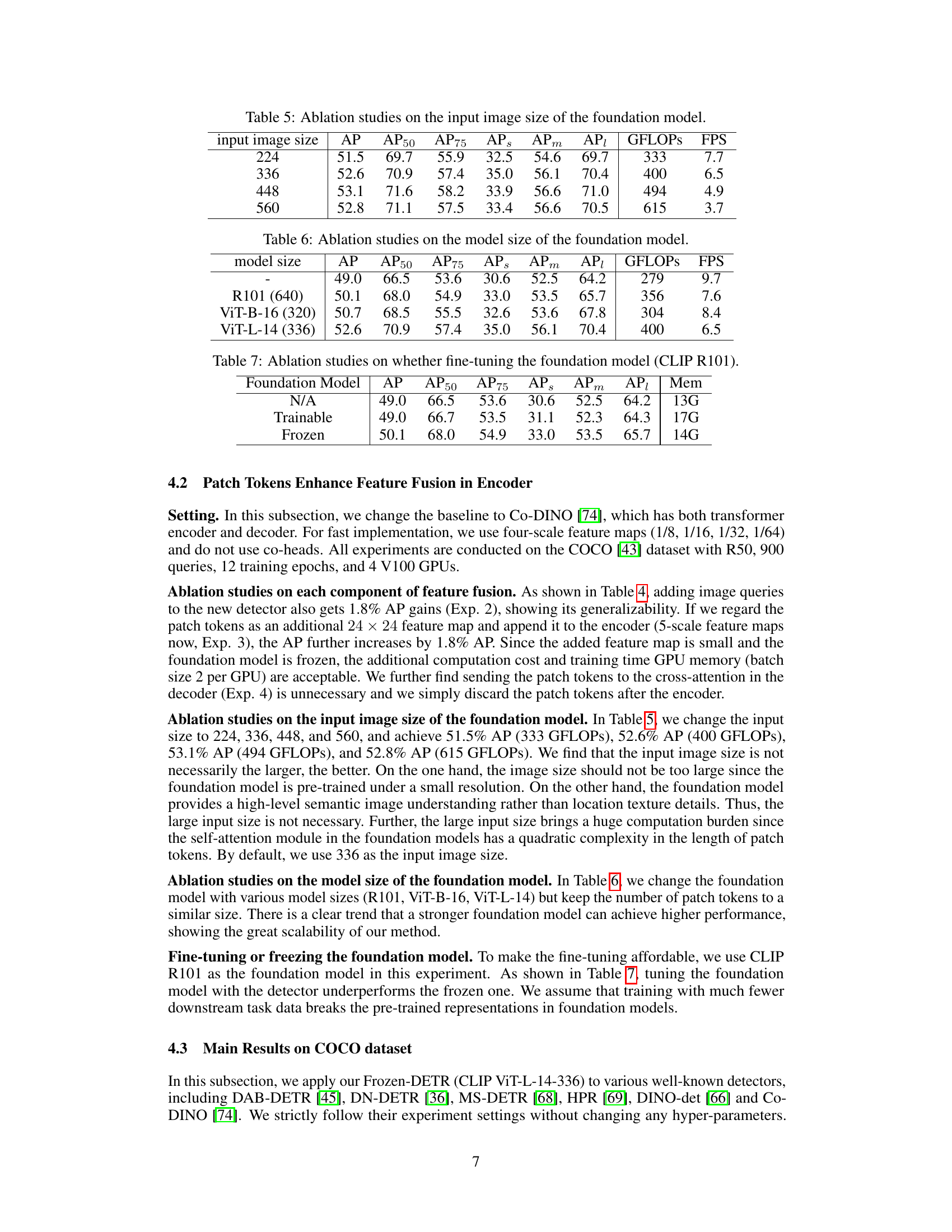

This table presents the ablation study on the input image size of the foundation model used in Frozen-DETR. Different input image sizes (224, 336, 448, and 560) were tested, and the resulting Average Precision (AP) metrics, along with breakdowns by AP50, AP75, APs, APm, and API, are reported. Additionally, the table shows the GFLOPs (giga floating-point operations) and FPS (frames per second) for each input size, illustrating the computational cost and speed tradeoffs associated with different input resolutions.

This table presents the ablation study results on the model size of the foundation model used in Frozen-DETR. It shows how the detector’s performance (measured by Average Precision (AP) and its variants) changes when using different sized foundation models (R101, ViT-B-16, ViT-L-14). The table also includes the computational cost (GFLOPS) and speed (FPS) for each model size.

This table presents the results of ablation studies conducted to evaluate the impact of fine-tuning the CLIP R101 foundation model on the performance of the object detection model. The table compares three scenarios: 1) No foundation model used, 2) The foundation model is trainable (fine-tuned), and 3) The foundation model is frozen (not fine-tuned). The metrics used for comparison are Average Precision (AP), AP at 50% IoU (AP50), AP at 75% IoU (AP75), AP for small objects (APs), AP for medium objects (APm), AP for large objects (APl), and memory consumption (Mem). The results indicate the performance differences based on training the foundation model or keeping it frozen.

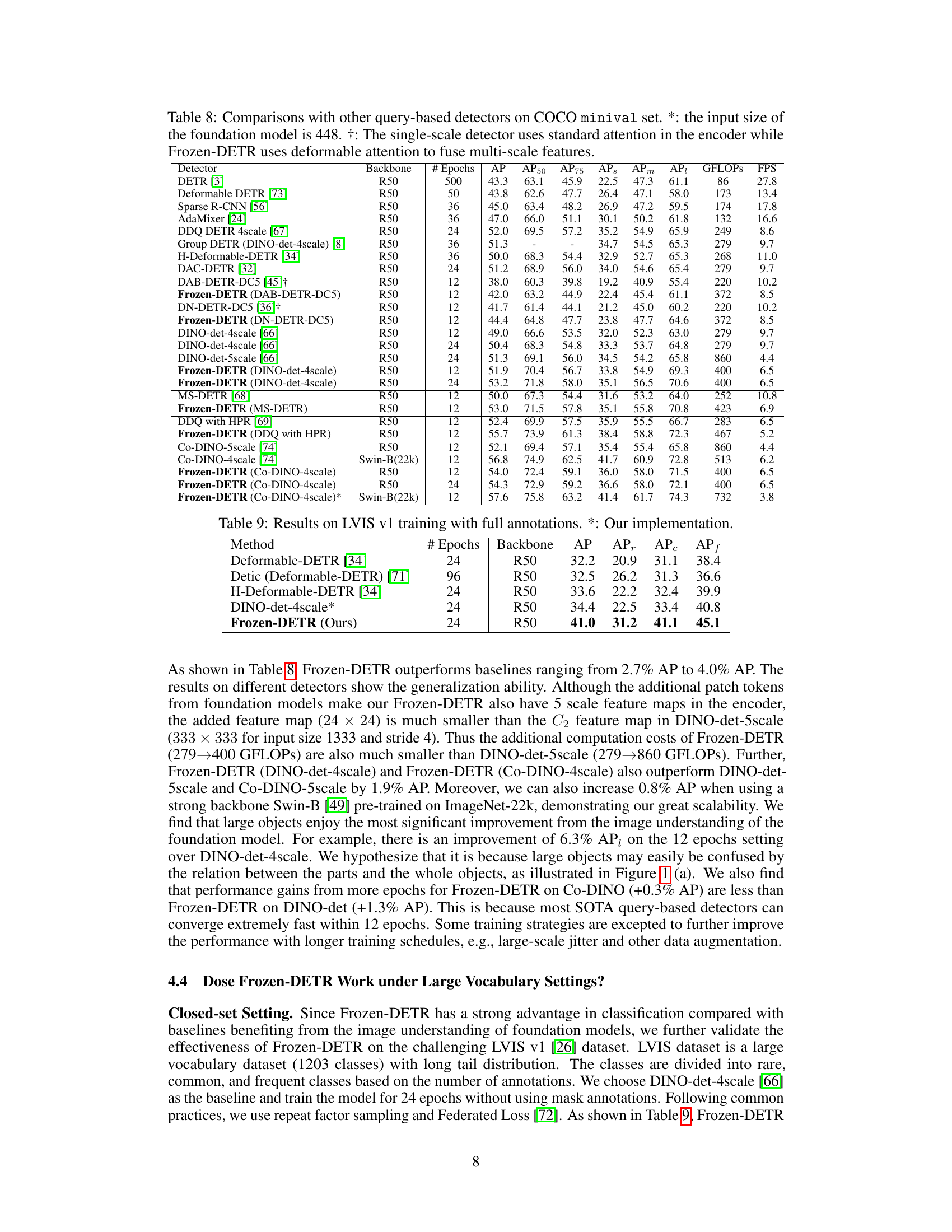

This table compares the performance of Frozen-DETR with other query-based object detectors on the COCO minival dataset. It shows the backbone used, number of training epochs, and various metrics including Average Precision (AP) at different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds (AP50, AP75), as well as AP for small, medium, and large objects. The table also notes when the foundation model input size is 448 and highlights the use of deformable attention in Frozen-DETR for multi-scale feature fusion. It demonstrates Frozen-DETR’s performance gains over existing methods.

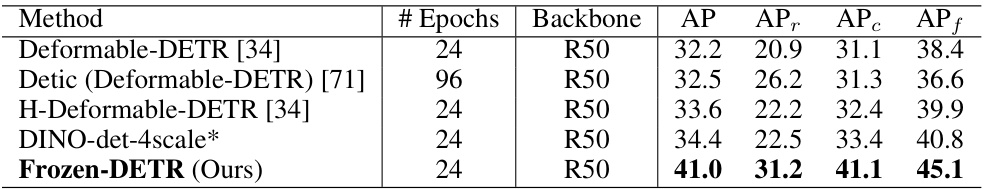

This table presents the results of different object detection methods on the LVIS v1 dataset, trained with full annotations. The results show average precision (AP), average precision for rare classes (APr), average precision for common classes (APc), and average precision for frequent classes (APf). The table highlights the performance of the proposed Frozen-DETR method in comparison to several other state-of-the-art detectors.

This table presents the results of different open-vocabulary object detection methods on the LVIS dataset. The results are broken down by several metrics, including AP (average precision), APr (average precision for rare classes), APc (average precision for common classes), and APf (average precision for frequent classes). The table highlights that the proposed Frozen-DETR method significantly outperforms other state-of-the-art methods, demonstrating its effectiveness in open-vocabulary object detection scenarios.

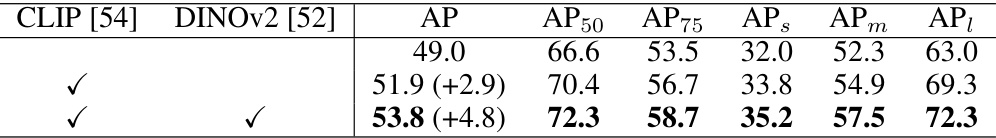

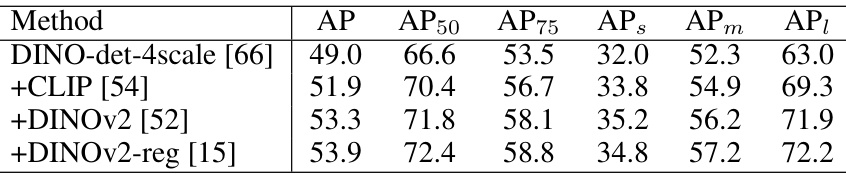

This table shows the performance of the DINO-det-4scale model with different combinations of foundation models (CLIP and DINOv2). It demonstrates that incorporating multiple foundation models can lead to further performance improvements. The AP, AP50, AP75, APs, APm and API metrics are provided, along with the absolute and relative gains in AP compared to the baseline (DINO-det-4scale).

This table presents an ablation study on the impact of adding image queries to different detector backbones (ResNet-50 and CLIP ResNet-50). It shows the Average Precision (AP), and its variations (AP50, AP75, APS, APM, API) for object detection with and without the addition of image queries. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of image queries in improving detection performance, regardless of the backbone used.

This table compares the performance and computational cost of four different methods for improving object detection performance. The baseline is DINO-det-4scale. The table shows the memory usage (Mem) and training time per epoch for each method, as well as the inference memory usage and frames per second (FPS), and the GFLOPS (floating point operations per second) for each method. The methods compared are: * DINO-det-4scale baseline: The original DINO-det-4scale model serves as the baseline for comparison. * Frozen-DETR (DINO-det-4scale): The proposed Frozen-DETR method applied to DINO-det-4scale. * DINO-det-5scale: The DINO-det model with 5 scales. * DINO-det-4scale + ViT-L backbone: The DINO-det-4scale model, but uses the ViT-L as a backbone instead of the standard backbone.

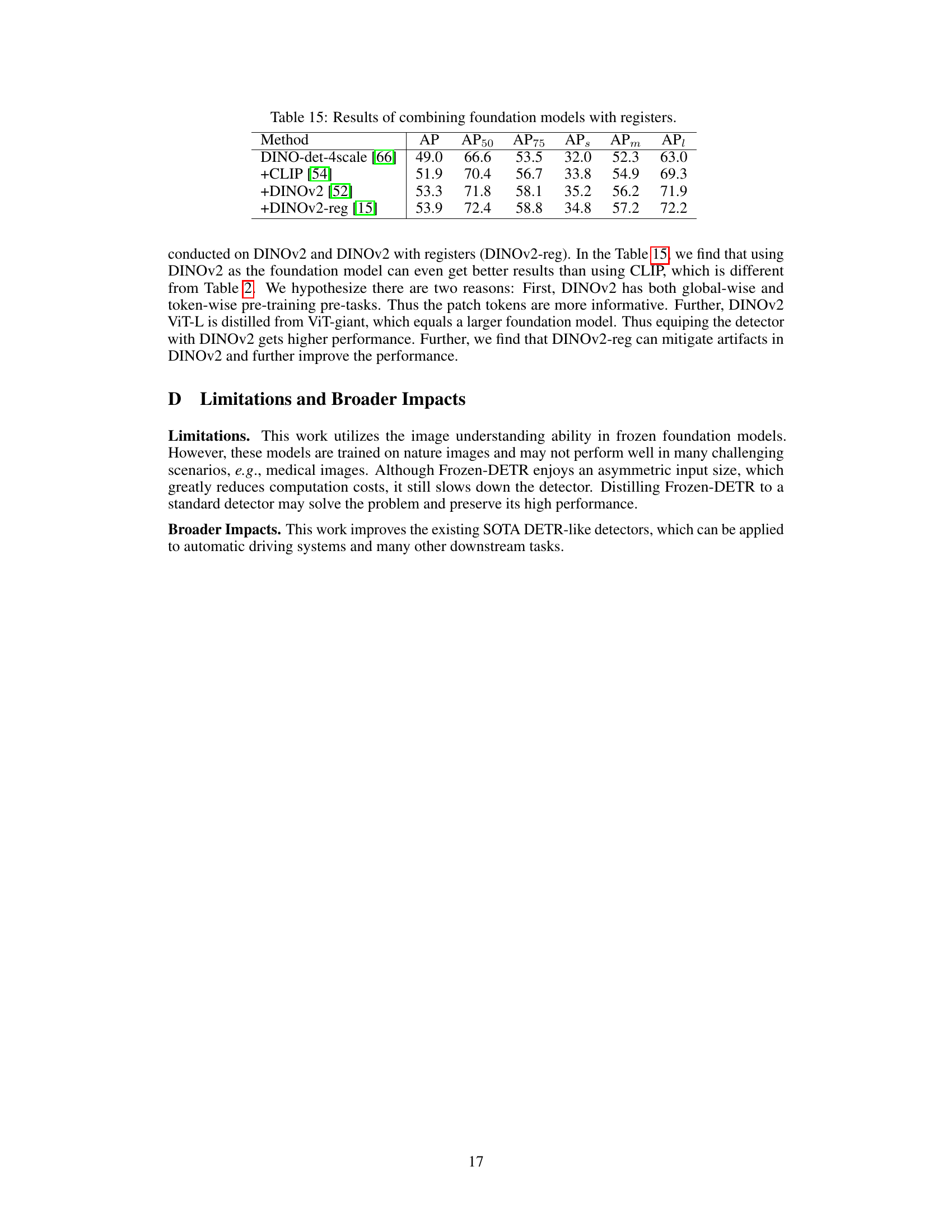

This table presents the results of experiments combining multiple foundation models (CLIP and DINOv2) with and without registers, demonstrating the impact of these additions on the performance metrics (AP, AP50, AP75, APS, APm, API). The baseline is DINO-det-4scale. The table shows a progressive improvement in performance metrics as more foundation models and registers are included, highlighting the benefits of integrating these components.

Full paper#