↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in online algorithms and machine learning. It addresses the brittleness of Pareto-optimal algorithms, a significant limitation hindering real-world applications. By introducing the concept of performance profiles and adaptive algorithms, it opens new avenues for designing robust and efficient algorithms in dynamic environments with imperfect predictions. This is especially relevant in fields like finance and AI, where smooth performance under prediction errors is vital.

Visual Insights#

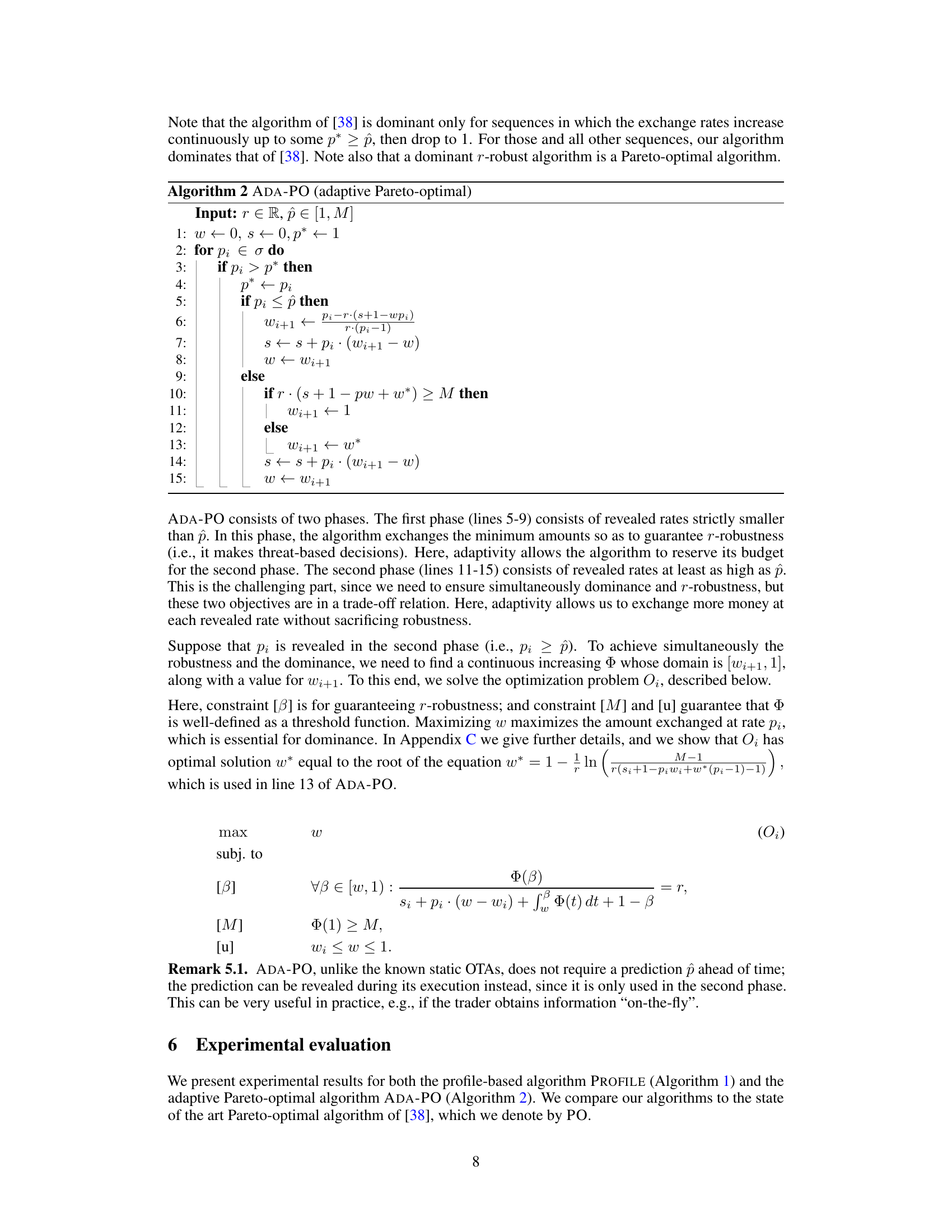

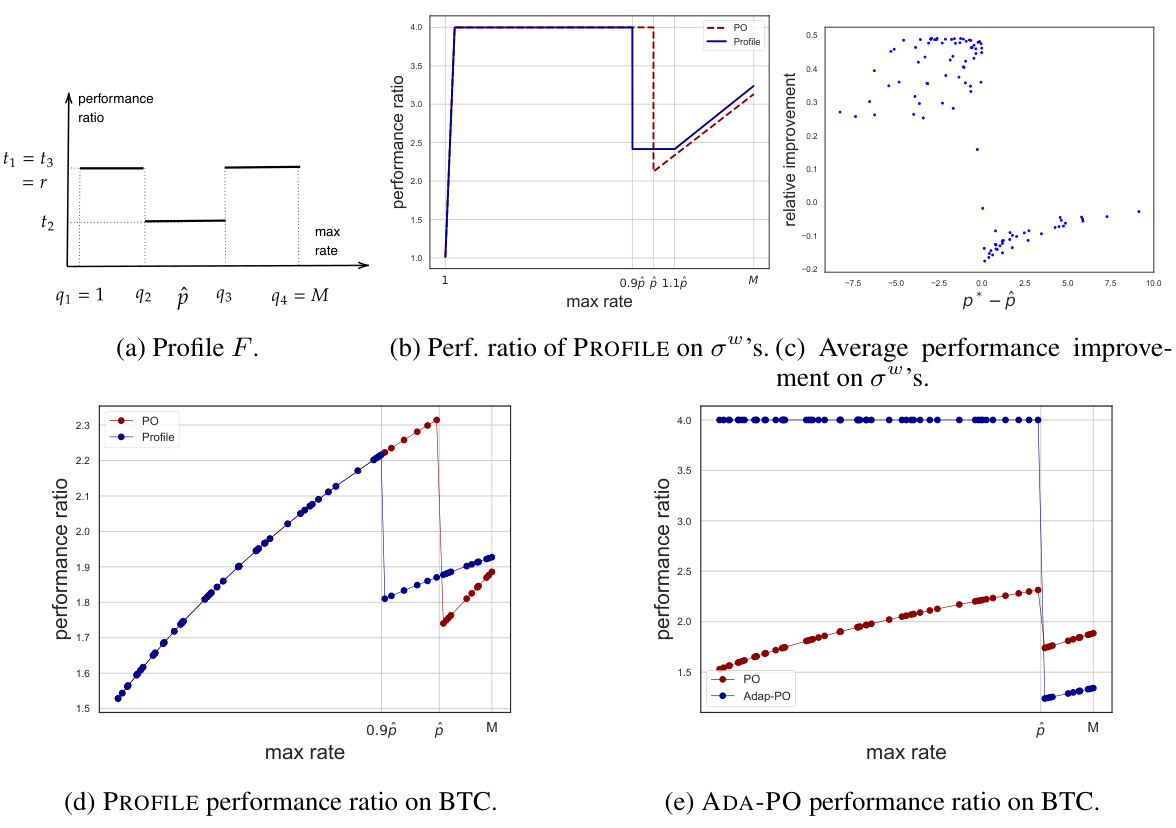

The figure illustrates two examples of profile functions. Figure 1(a) shows a profile function with six intervals, illustrating an asymmetric dependency on the prediction error. The performance ratio decreases with increasing error up to a point and then increases. Figure 1(b) shows a Pareto profile, a special case where the performance ratio is at most t1 for any error, except when the prediction is error-free (t2 < t1). This demonstrates the difference between a general profile and the extreme cases encompassed by Pareto optimality.

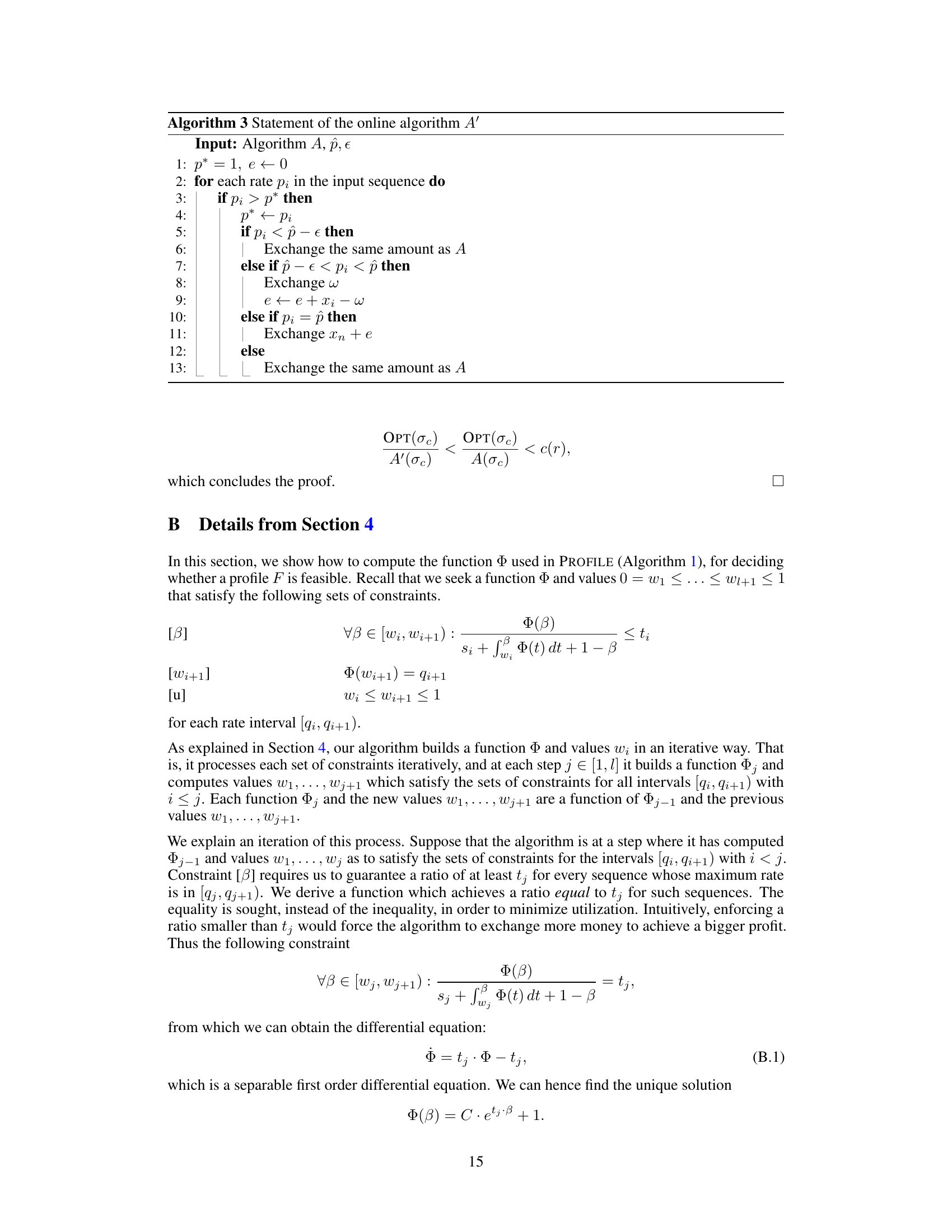

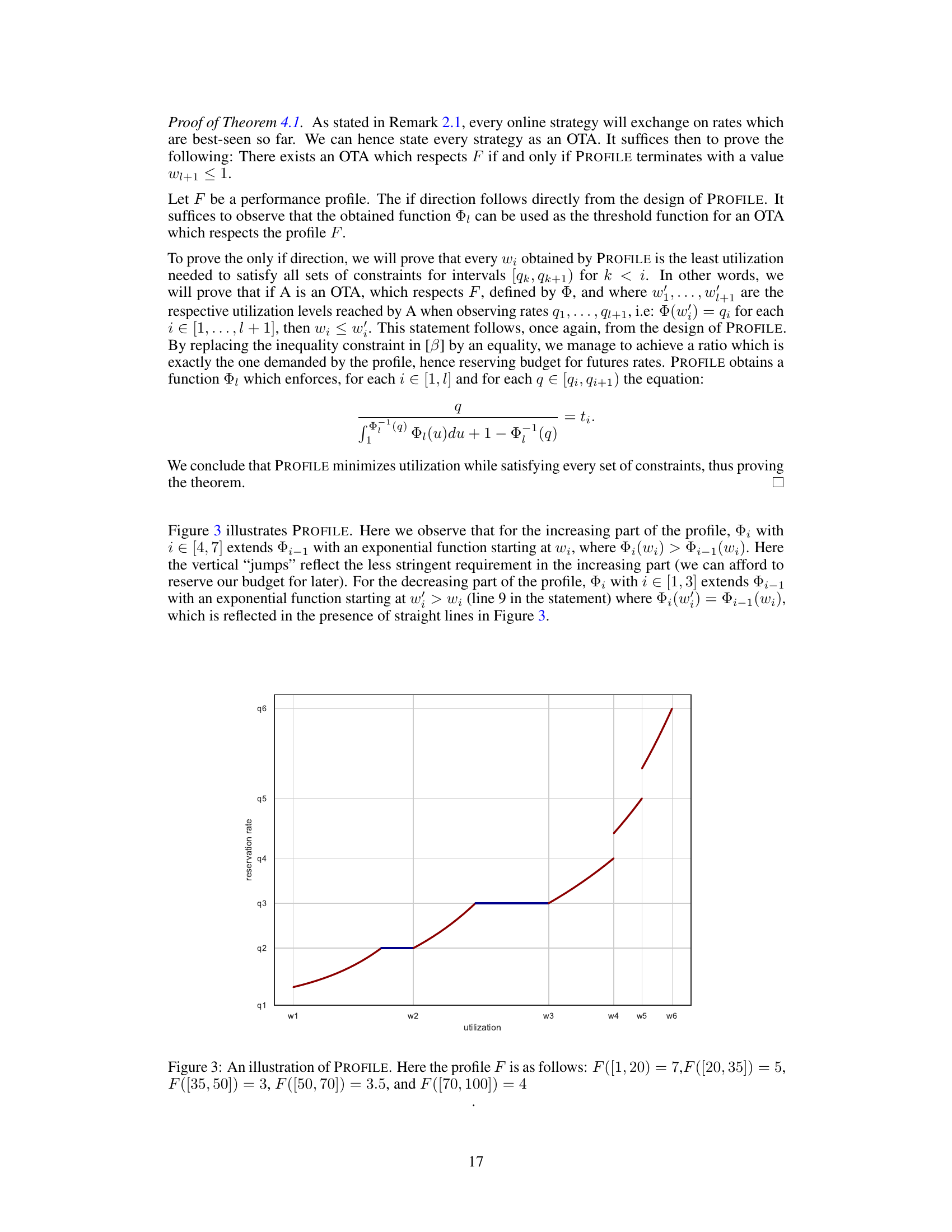

This figure summarizes the experimental results for both the profile-based algorithm (PROFILE) and the adaptive Pareto-optimal algorithm (ADA-PO), comparing them to the state-of-the-art Pareto-optimal algorithm (PO). It shows performance ratios for worst-case sequences and real Bitcoin exchange rate data, illustrating the impact of prediction error and highlighting PROFILE’s robustness and ADA-PO’s dominance in certain scenarios.

In-depth insights#

Pareto-Optimality’s Limits#

The concept of Pareto-optimality, while valuable in multi-objective optimization, reveals critical limitations when applied to online algorithms with learned predictions. A core issue is brittleness: Pareto-optimal algorithms, designed for optimal tradeoffs between consistency (perfect predictions) and robustness (adversarial predictions), can exhibit severely degraded performance with even minor prediction errors. This fragility undermines their practical applicability in real-world scenarios where prediction imperfections are inevitable. The pursuit of smoothness, ensuring a gradual performance degradation as prediction error increases, becomes crucial. This necessitates moving beyond the simple Pareto-optimal framework to incorporate user-specified performance profiles. Such profiles provide a flexible mechanism to regulate the algorithm’s behavior based on prediction accuracy, thereby mitigating brittleness and adapting the algorithm to realistic noise levels. Worst-case assumptions inherent in some Pareto-optimal algorithms further limit their efficacy. Algorithms tailored to extreme, unrealistic input sequences may perform suboptimally in typical scenarios. Adaptive algorithms that leverage deviations from worst-case inputs, thus improving performance in more realistic settings, become highly desirable. A nuanced approach is crucial: While Pareto-optimality offers valuable theoretical insights into extreme performance limits, combining it with considerations of smoothness and adaptive behavior is essential for creating robust and practical learning-augmented algorithms.

Profile-Based Algorithm#

The Profile-Based Algorithm section introduces a novel framework for designing online algorithms that are robust to prediction errors. Instead of solely focusing on Pareto optimality, which can be brittle, this approach incorporates a user-specified performance profile. This profile maps prediction error to an acceptable performance bound, allowing for a more flexible and practical design. The algorithm determines the feasibility of a given profile and constructs an online strategy that respects it, offering a balance between consistency (perfect predictions) and robustness (adversarial predictions), tailored to the user’s risk tolerance and prediction accuracy expectations. This contrasts with traditional Pareto-optimal approaches, which often perform poorly with even small prediction errors. The framework’s key strength lies in its adaptability and control over the algorithm’s behavior across the entire spectrum of prediction errors, moving beyond the limitations of extreme-case analysis prevalent in Pareto-optimal techniques. The ability to tailor the algorithm’s performance via the profile makes it significantly more resilient and practical for real-world applications, particularly where perfect prediction is unrealistic.

Adaptive Trading#

Adaptive trading strategies represent a significant advancement in algorithmic trading by dynamically adjusting to changing market conditions. Unlike traditional rule-based systems, which rely on pre-programmed rules and indicators, adaptive systems leverage machine learning techniques to learn and adapt to complex market dynamics. This adaptability is crucial because markets are inherently non-stationary, with patterns and trends shifting over time. Adaptive algorithms can identify and exploit these changes, potentially resulting in improved performance compared to static strategies. Reinforcement learning is a prominent method for developing adaptive trading agents, enabling them to learn optimal trading decisions through trial and error. These agents interact with market simulations or real-time data, learning to maximize returns while managing risk. However, challenges remain. Developing robust and generalizable adaptive trading models requires extensive data, careful model selection and parameter tuning, and rigorous backtesting. The risk of overfitting to past market data is a significant concern, and the unpredictable nature of financial markets means that any model, however sophisticated, is subject to unexpected events and potential losses. Ethical considerations are also paramount. The use of sophisticated algorithms raises concerns regarding transparency, fairness and the potential for market manipulation.

Smoothness & Brittleness#

The concept of “Smoothness & Brittleness” in the context of Pareto-optimal learning-augmented algorithms highlights a crucial trade-off. Smoothness refers to the algorithm’s performance gracefully degrading as prediction error increases, ideally interpolating smoothly between perfect prediction performance and worst-case (robustness) performance. Brittleness, conversely, signifies a drastic performance drop with even minor prediction errors, rendering the Pareto-optimal algorithm potentially worse than a non-prediction based algorithm. The authors argue that the standard Pareto-optimal framework, focusing solely on the extremes of perfect and adversarial predictions, is insufficient because it fails to account for this brittleness. They propose a novel framework incorporating user-specified performance profiles to regulate performance based on prediction error, thereby achieving the desired smoothness and mitigating the brittleness inherent in existing Pareto-optimal approaches. This emphasis on managing the impact of prediction uncertainty across the entire spectrum of errors, rather than just at the extremes, is a significant contribution. The introduction of performance profiles allows for a more practical and adaptable approach to designing learning-augmented algorithms. This flexible framework facilitates a balance between the ideal consistency under accurate predictions and robust performance against prediction errors.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work on overcoming brittleness in Pareto-optimal learning-augmented algorithms could explore several key areas. Extending the performance profile framework to a broader class of online problems beyond one-way trading is crucial to establish its general applicability and effectiveness. This involves carefully adapting the profile concept to the unique characteristics of various online decision-making scenarios. Investigating the interplay between the smoothness enforced by the profile and the algorithm’s computational complexity is also critical. While the current work demonstrates improvements, it’s necessary to understand the trade-off between enhanced robustness and computational efficiency. Developing more sophisticated adaptive algorithms that leverage deviations from the worst-case input more efficiently is another important direction. The proposed adaptive algorithm is a promising first step, but further refinement is needed to optimize its performance and robustness across diverse real-world datasets. Finally, empirical evaluations on a wider range of real-world datasets are crucial to validate the findings and ensure the robustness of the proposed framework across different problem instances and prediction models. Incorporating noisy or uncertain predictions, beyond maximum rate prediction, would also make the framework more realistic.

More visual insights#

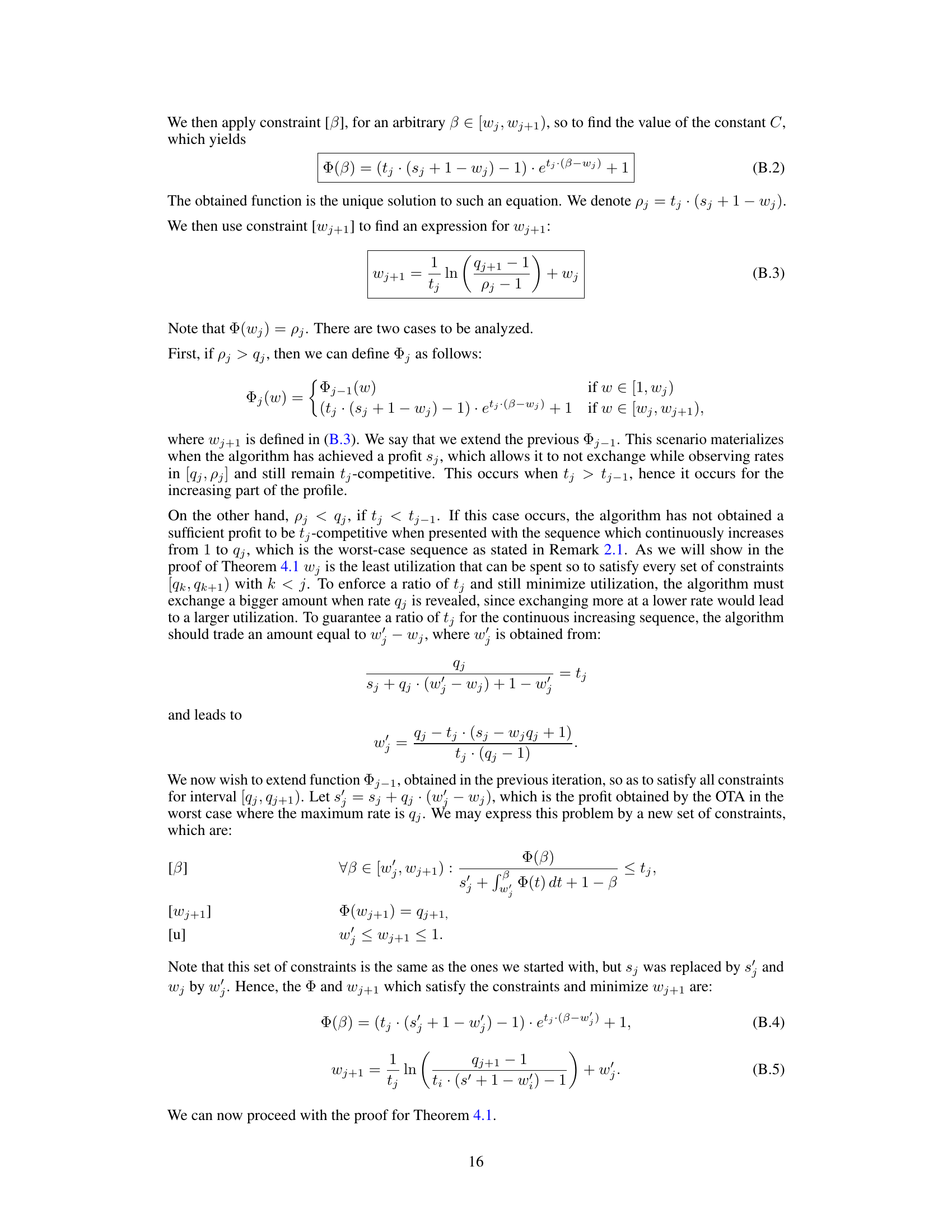

More on figures

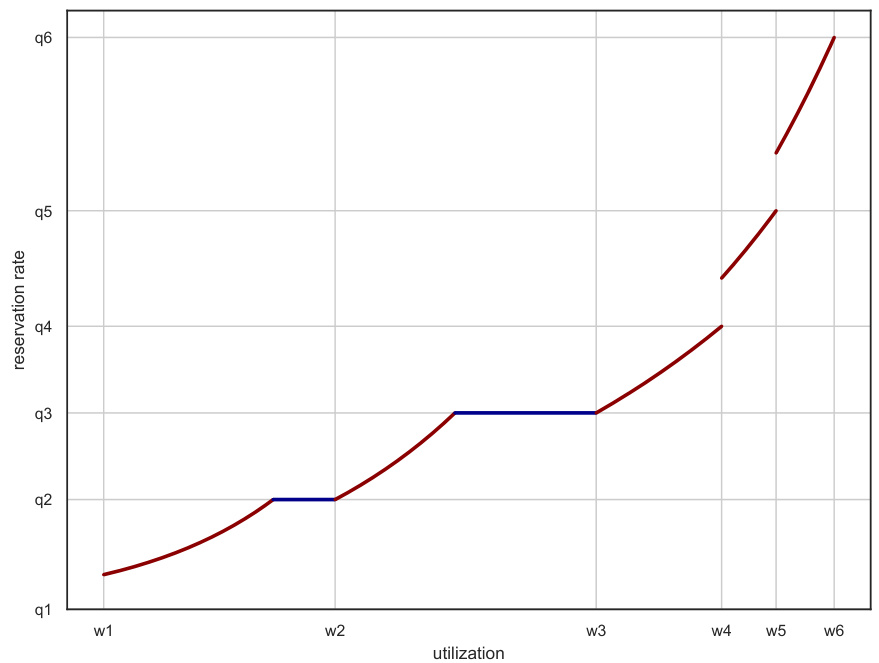

The figure consists of two subfigures. Figure 1a shows a sample profile function F with six intervals. The intervals [q1, q2), [q2, q3), [q3, q4) correspond to a decreasing portion of the profile, and the rest to the increasing portion. The prediction pˆ belongs to both portions. Figure 1b illustrates a Pareto profile in which there are only three intervals and where the prediction pˆ is in the middle interval. The Pareto profile leads to Pareto optimality, by virtue of the definition of Pareto optimality.

This figure summarizes the experimental results presented in the paper. It shows the performance comparison of different algorithms, PROFILE and PO, in different settings. Subfigure (a) illustrates the profile F used in the experiments. Subfigures (b) and (c) show the performance of PROFILE and PO on worst-case sequences as a function of the prediction error, highlighting PROFILE’s robustness and smoothness around the prediction. Subfigure (d) demonstrates the performance of the algorithms on real Bitcoin exchange rate data, while subfigure (e) compares the performance of ADA-PO and PO on the same real data. The results confirm that PROFILE is less brittle than PO and ADA-PO leverages deviations from worst-case scenarios, highlighting the improvements of these new algorithms over existing methods.

This figure illustrates how the PROFILE algorithm constructs the threshold function in an iterative manner. For the increasing part of the profile, the function extends the previous one with an exponential function, reflecting less stringent requirements. Conversely, for the decreasing part, the function is extended with a steeper exponential function to satisfy tighter constraints. The vertical jumps in the graph represent the transitions between consecutive intervals in the profile, highlighting how PROFILE balances competing performance requirements across various prediction error ranges.

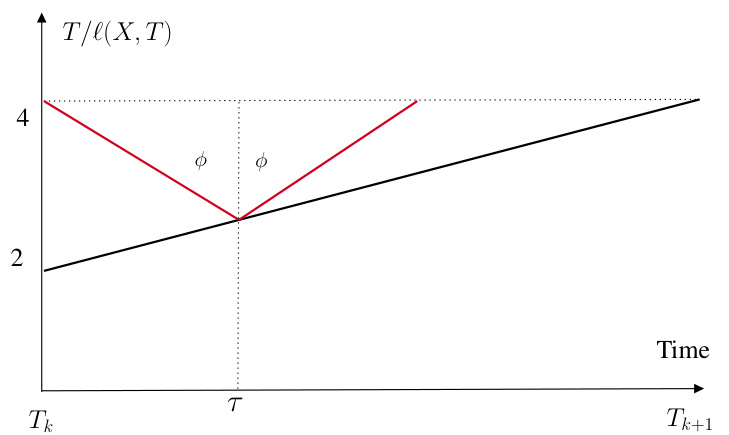

This figure illustrates a profile function F for contract scheduling. The profile is a symmetric, bilinear function that is decreasing for T < τ and increasing for T > τ. The angle φ captures the smoothness of the degradation of the schedule as a function of the prediction error. The profile function is used in the analysis of the learning-augmented contract scheduling problem.

This figure illustrates the profile function F used in the contract scheduling problem. The profile defines a desired performance of the schedule as a function of the prediction error. It’s a symmetric, bilinear function, decreasing for T < τ and increasing for T > τ, with a slope of φ. The angle φ represents how quickly the algorithm’s performance degrades as the prediction error increases. The profile aims to balance optimal performance with robustness to prediction error.

This figure illustrates a profile function F which is used to specify the desired performance of an online algorithm as a function of prediction error. The profile is symmetric around the prediction τ and is decreasing for T < τ and increasing for T > τ. The slope of the function captures the smoothness with which the algorithm’s performance is allowed to degrade as the prediction error increases. This profile is defined by the end-user and is an important element of the profile-based framework introduced in the paper.

This figure summarizes the experimental results of the paper, comparing the performance of PROFILE and PO algorithms under different settings. Panel (a) shows the profile F used in the experiment, illustrating the desired relationship between prediction error and performance ratio. Panel (b) plots the performance ratio of PROFILE and PO on worst-case sequences as a function of the maximum rate, highlighting PROFILE’s resilience to prediction error compared to the brittleness of PO. Panel (c) quantifies the average performance improvement of PROFILE over PO across multiple worst-case sequences. Panel (d) and (e) present the performance ratios on sequences from real Bitcoin (BTC) exchange rate data for PROFILE and ADA-PO respectively, demonstrating PROFILE’s smoothness and ADA-PO’s dominance over PO.

Full paper#