↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Bilevel optimization (BiLO) problems, particularly those with mixed-integer non-linear constraints, are notoriously hard to solve. Existing methods struggle with scalability and generalizability. This paper addresses these limitations by proposing NEUR2BILO, a data-driven framework that leverages the power of neural networks. BiLO is challenging because of its nested structure, where a leader makes decisions that account for the follower’s response. Finding the optimal solution in such scenarios is complex and computationally expensive.

NEUR2BILO tackles this by embedding neural network approximations of either the leader or follower’s value function within an easy-to-solve mixed-integer program. These neural networks are trained via supervised learning on a dataset of previously solved instances. The framework then uses this approximation to quickly solve the problem. The results show NEUR2BILO delivers high-quality solutions significantly faster than existing state-of-the-art methods across multiple applications, including network design and interdiction problems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on bilevel optimization problems, especially those dealing with mixed-integer non-linear cases. It introduces a novel, data-driven approach that significantly improves the speed and scalability of solving such problems, an area where existing methods often fall short. The framework’s ability to integrate neural networks into MIP solvers opens up new avenues for research into high-efficiency algorithms in data-driven algorithm design settings.

Visual Insights#

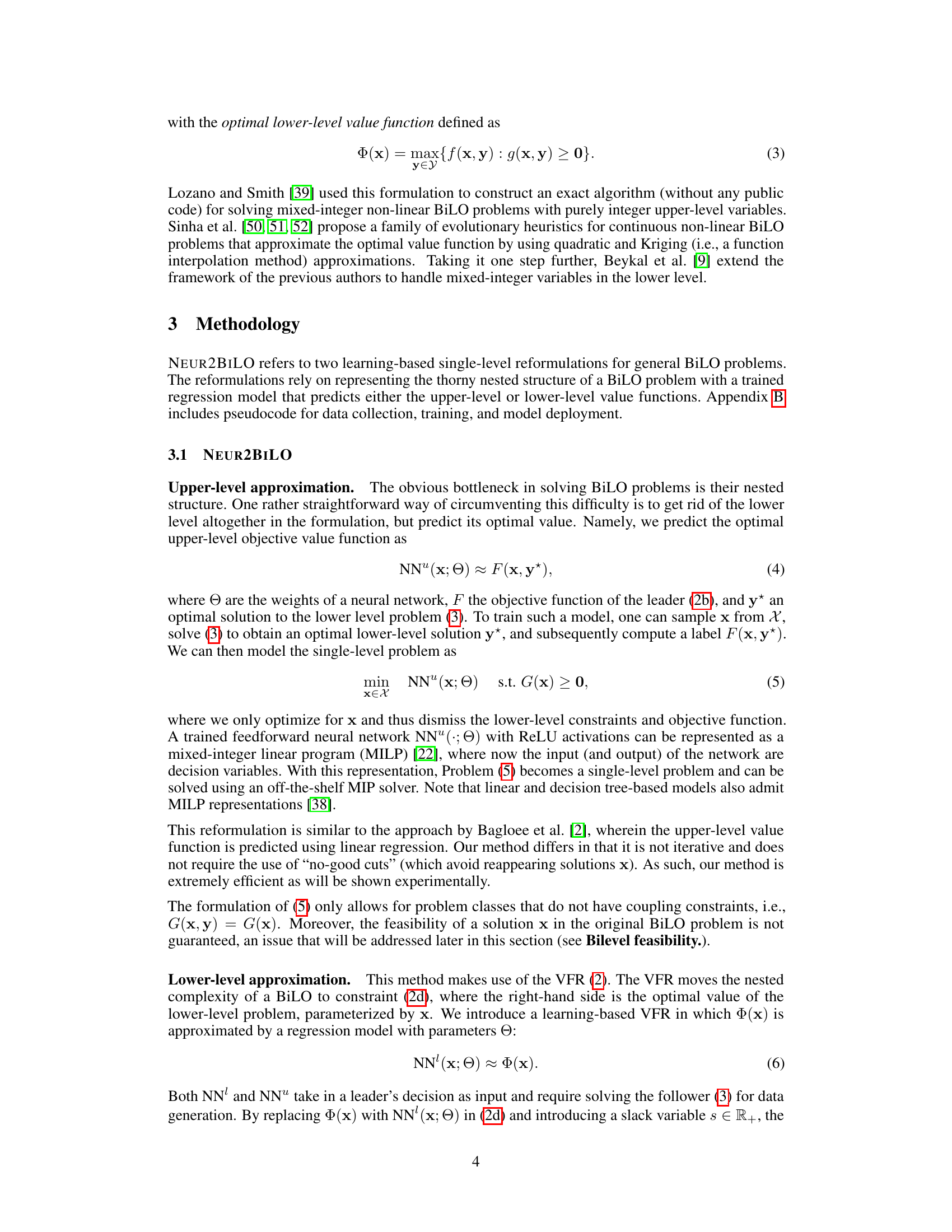

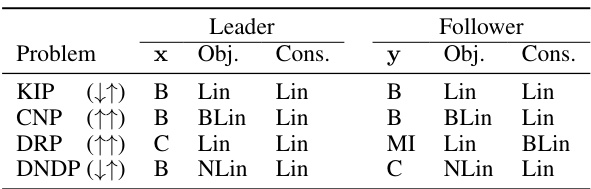

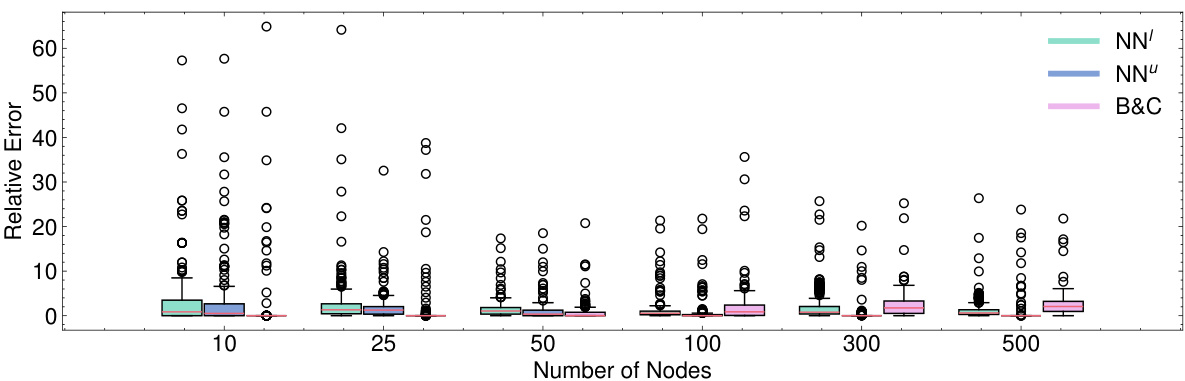

This box plot visualizes the distribution of relative errors for the Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP) when the interdiction budget (k) is set to one-fourth of the total number of items (n). It compares the performance of four different methods: NEUR2BILO (NN¹, NN²), the greedy value function approximation (G-VFA), and the branch-and-cut (B&C) algorithm. The plot shows the median, quartiles, and outliers of the relative errors for various problem sizes (n). The purpose of the figure is to illustrate NEUR2BILO’s ability to quickly and efficiently find high-quality solutions compared to other methods.

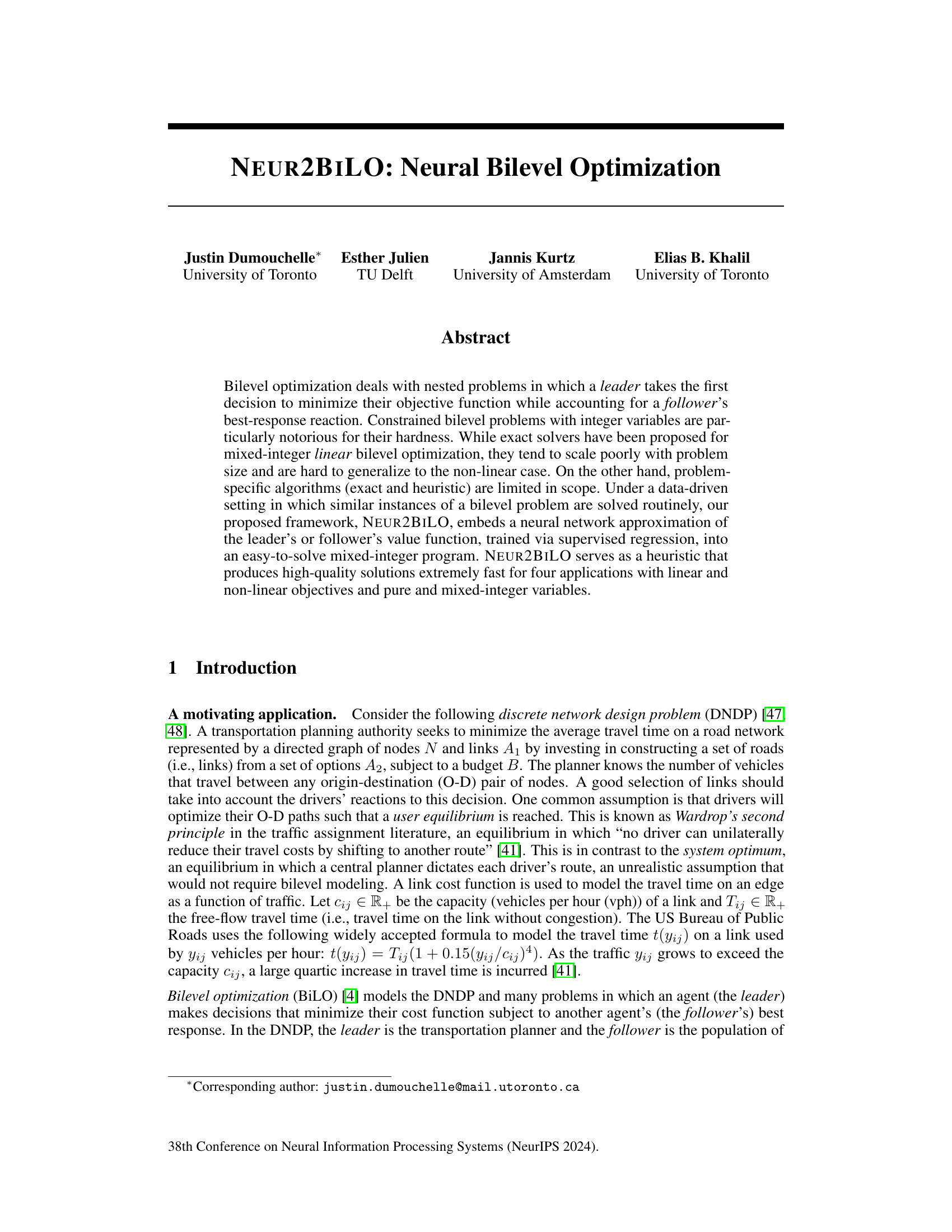

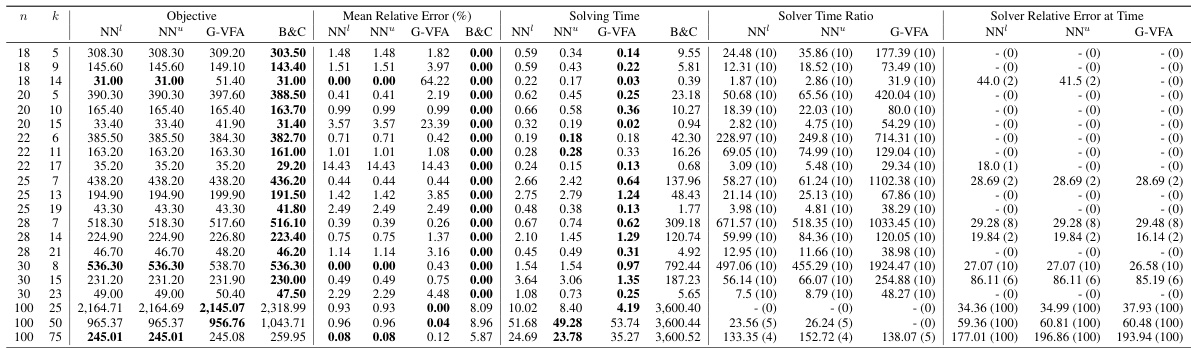

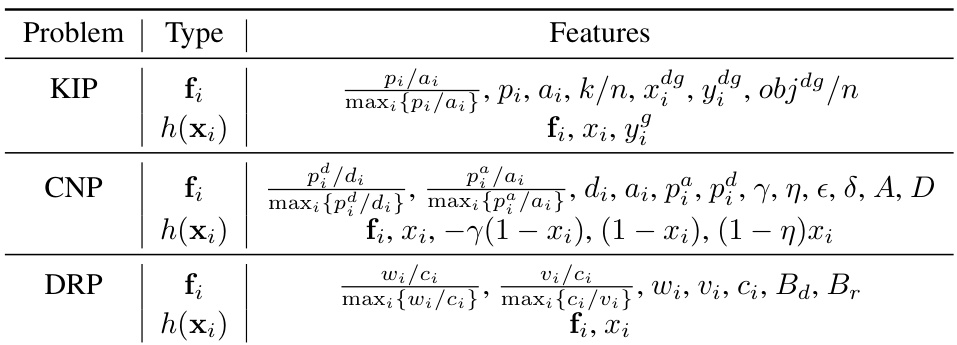

This table summarizes the characteristics of four benchmark bilevel optimization problems used in the paper: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), Donor-Recipient Problem (DRP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). For each problem, it specifies the type of variables for the leader (x) and follower (y) (Binary, Continuous, or Mixed-Integer), the type of objective function (Linear, Bilinear, or Non-Linear), and the type of constraints (Linear, Bilinear, or Non-Linear). It also indicates whether the leader’s objective is to minimize or maximize, and the same for the follower’s objective.

In-depth insights#

Bi-level Optimization#

Bi-level optimization (BiLO) tackles hierarchical problems where a leader’s decisions influence a follower’s optimal response. The core challenge lies in the nested structure, where the leader’s objective function depends on the follower’s reaction, creating intricate interdependence. Exact solutions are computationally expensive, especially with integer variables, thus highlighting the need for efficient approximation techniques. Many applications exist across diverse domains, including transportation planning, resource allocation, and network security, showcasing the versatility and importance of BiLO. Data-driven approaches, such as using neural networks to approximate value functions, represent a promising avenue for tackling the computational complexities inherent in BiLO problems. These methods offer the potential for faster, high-quality solutions in scenarios where similar instances are solved repeatedly, making them attractive for practical applications. However, approximation methods need careful consideration, as accuracy directly impacts the solution quality and feasibility. Future research may concentrate on developing more robust approximation methods and expanding into related areas like stochastic and robust bilevel programming.

Neural Network Embedding#

Neural network embedding, in the context of bilevel optimization, presents a powerful technique for approximating complex value functions. Instead of explicitly solving the computationally expensive lower-level problem repeatedly, a neural network is trained to learn the relationship between the leader’s decisions and the follower’s optimal response. This embedding approach offers significant speedups since it replaces nested optimization with a single-level problem. The accuracy of the embedding directly impacts solution quality. A well-trained network can provide high-quality approximations, making the overall approach highly efficient, especially for mixed-integer non-linear bilevel problems. The choice of neural network architecture and training techniques is critical for achieving optimal performance; factors to consider include network depth, activation functions, and regularization strategies. The ability to embed the neural network into a mixed-integer program (MIP) is a key feature, allowing seamless integration within existing optimization solvers and enabling the use of established MIP techniques for finding high-quality solutions. However, limitations exist due to potential approximation errors. The trade-off between approximation accuracy and computational cost needs careful consideration.

Data-driven BiLO#

Data-driven Bilevel Optimization (BiLO) represents a significant paradigm shift in addressing complex, nested optimization problems. Traditional BiLO methods often struggle with scalability and generalizability, particularly when dealing with real-world scenarios involving large datasets and intricate constraints. A data-driven approach leverages historical data to learn patterns and relationships within the bilevel problem structure. This learning process can be achieved through various machine learning techniques such as neural networks or regression models, enabling the approximation of complex value functions or the direct prediction of optimal solutions. The key advantage lies in the potential for significantly faster solution times compared to traditional methods, as the computationally expensive steps of the nested optimization are replaced by relatively quicker inference operations from the trained model. However, challenges remain in ensuring the accuracy and robustness of the learned models, requiring careful selection of training data, appropriate model architectures, and robust evaluation metrics. Furthermore, a data-driven strategy requires sufficient high-quality data, which can be expensive or even unavailable for certain problem domains. Despite these challenges, the potential benefits in scalability, speed, and generalization make data-driven BiLO a promising area of research, particularly given the increase in availability of computational power and relevant datasets.

Approximation Limits#

The heading ‘Approximation Limits’ in a research paper would likely discuss the inherent constraints and inaccuracies associated with using approximation methods. This section would be crucial for establishing the reliability and validity of the research findings. A thoughtful analysis would delve into the types of approximations used, such as linear or neural network approximations, examining the sources of error introduced by each. The discussion should highlight the trade-off between approximation accuracy and computational efficiency, addressing the question of whether the chosen level of accuracy is sufficient to support the paper’s conclusions. It’s vital to acknowledge that approximation limits aren’t merely technical challenges; they have methodological implications. The study’s generalizability and the robustness of its findings in diverse settings depend significantly on the nature and magnitude of approximation errors. Therefore, a rigorous evaluation of these limits is essential for establishing the credibility and impact of the research.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from the NEUR2BILO framework are plentiful. Extending NEUR2BILO to handle more complex bilevel structures, such as those with coupled constraints or multiple followers, is a critical next step. This could involve investigating more sophisticated neural network architectures or exploring alternative value function approximations. Improving the theoretical guarantees provided for NEUR2BILO is another avenue, particularly in the case of the upper-level approximation where no guarantee currently exists. This could involve refining the analysis or developing novel approximation methods. Exploring different model architectures and feature engineering techniques will also yield improvements in prediction accuracy and computational efficiency. Investigating the application of other types of machine learning models to BiLO such as graph neural networks or tree-based models is also important. Finally, empirical evaluation on a broader range of bilevel problems and comparative studies with state-of-the-art methods are crucial for demonstrating the generality and effectiveness of NEUR2BILO across diverse applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This box plot visualizes the distribution of relative errors for the Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP) when the interdiction budget (k) is set to n/4, where n is the number of items. Each box represents a different problem size (number of items), and the boxes show the median (line inside the box), the interquartile range (the box itself), and the whiskers extending to the minimum and maximum values (excluding outliers, which are shown as individual points). The plot compares the relative errors achieved by four different methods: NEUR2BILO’s upper-level (NNu) and lower-level (NNl) approximations, the greedy value function approximation (G-VFA), and the branch-and-cut (B&C) method. This allows for visual comparison of the performance of these methods in terms of the accuracy of their solutions for varying problem sizes.

This box plot visualizes the distribution of relative errors for the Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP) when the interdiction budget (k) is set to a quarter of the total number of items (n). The plot compares the performance of four different methods: NN¹ (lower-level approximation with neural network), NN

This box plot visualizes the distribution of relative errors for the Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP) when the interdiction budget (k) is set to a quarter of the number of items (n). It compares the performance of four different methods: NEUR2BILO’s upper-level approximation (NNu), NEUR2BILO’s lower-level approximation (NNl), a greedy value function approximation (G-VFA), and a state-of-the-art branch-and-cut algorithm (B&C). The plot shows the median, quartiles, and outliers of the relative errors for each method across various problem instance sizes, illustrating the variability and relative performance of each approach.

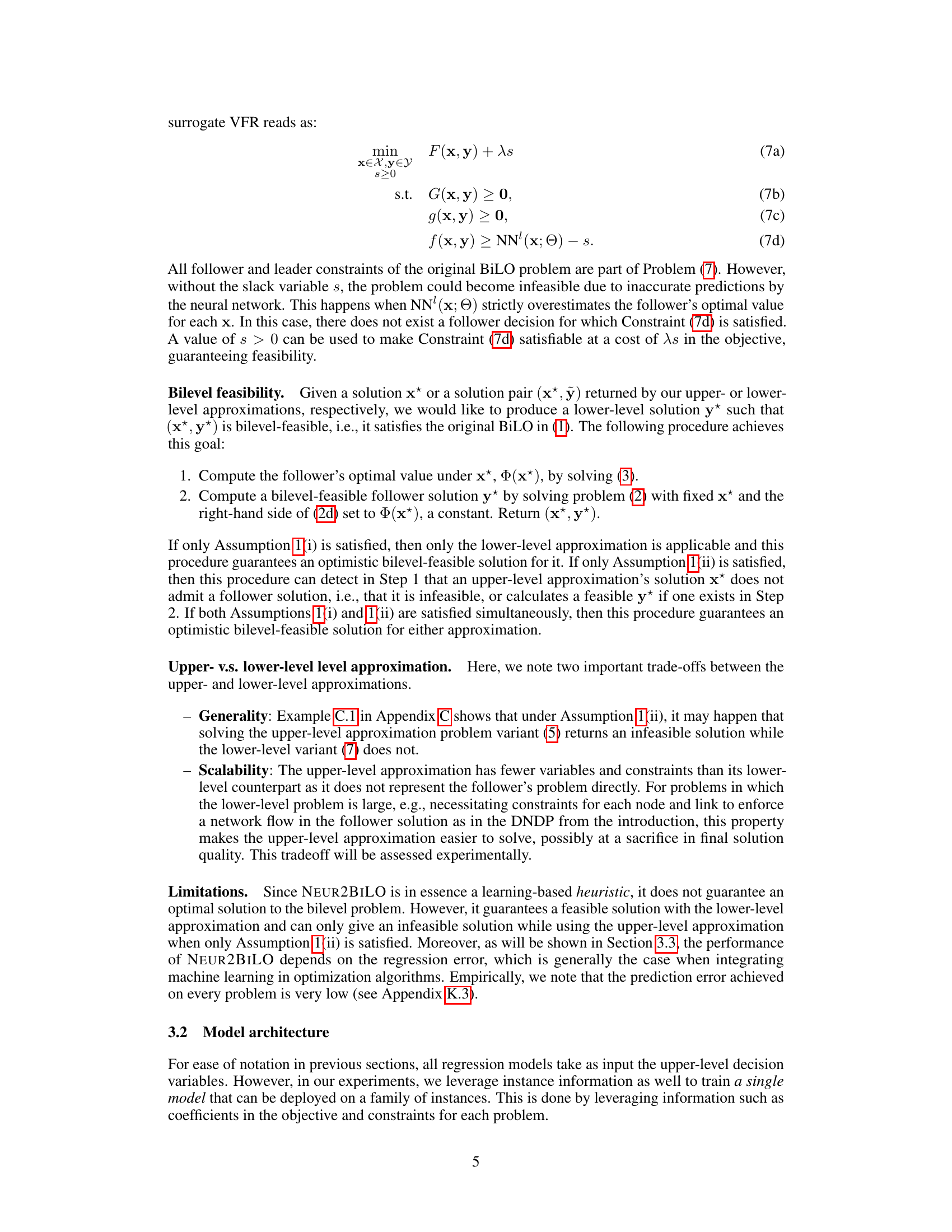

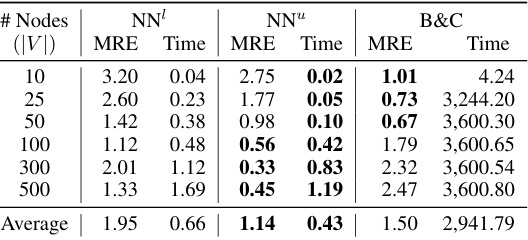

The figure shows the box plot of relative errors for the Critical Node Problem (CNP). The box plots compare the performance of the Neural Bilevel Optimization (NEUR2BILO) upper-level (NNu) and lower-level (NNl) approximations against the traditional Branch and Cut (B&C) method. The x-axis represents the number of nodes in the network, and the y-axis represents the relative error. It highlights that NEUR2BILO methods, particularly the lower-level approximation, offer substantially faster and more accurate solutions than the standard B&C approach, especially as the problem size (number of nodes) increases. Note that for the largest problem size (500 nodes), B&C failed to find a solution for two of the instances.

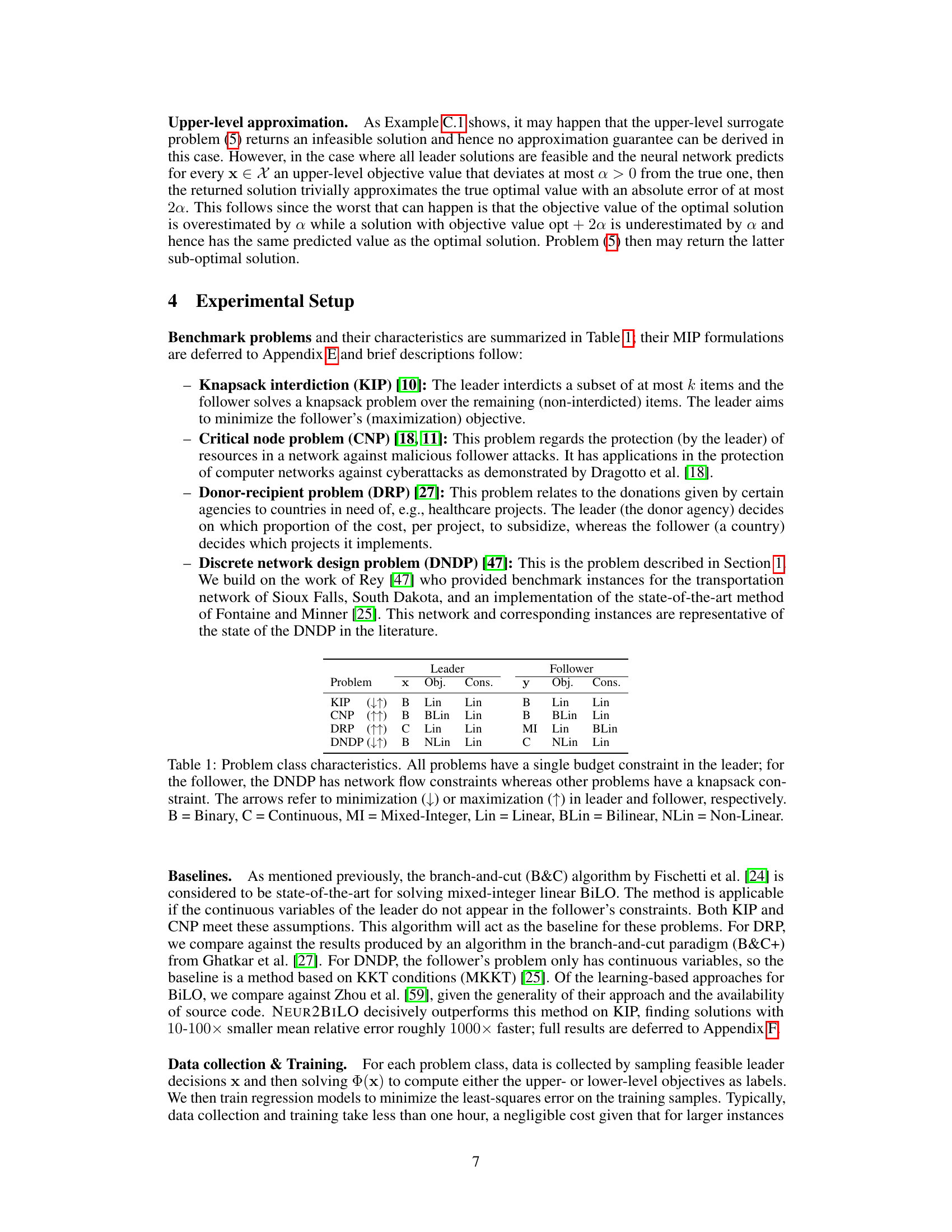

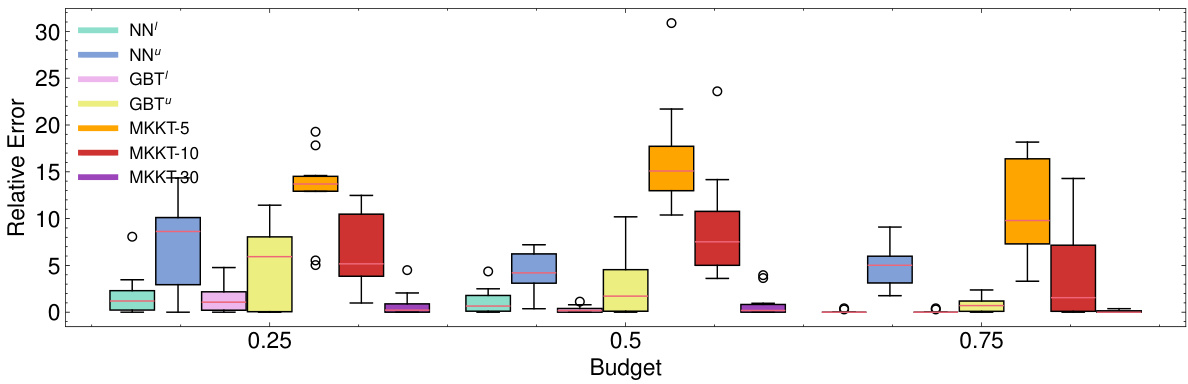

The figure shows box plots of relative errors for the Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP) with 10 edges. It compares the performance of the NEUR2BILO neural network models (NN’, NNu, GBT’, GBTu) against the baseline MKKT method. The MKKT results are shown for three different time limits (5, 10, and 30 seconds). The x-axis represents the budget, and the y-axis represents the relative error. The plot helps visualize the distribution of errors for each method across different budget levels and highlights the speed and accuracy of NEUR2BILO compared to the baseline approach.

This figure shows a comparison of the relative errors for different methods in solving the Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP) with 10 edges. The methods compared include three neural network-based approaches (NN¹, NN’, GBT¹, GBTU) and three Mixed-Integer Knapsack Technique (MKKT) runs with varying time limits (5, 10, and 30 seconds). The x-axis represents the budget, and the y-axis represents the relative error. The box plots show the distribution of relative errors for each method across different budget levels.

More on tables

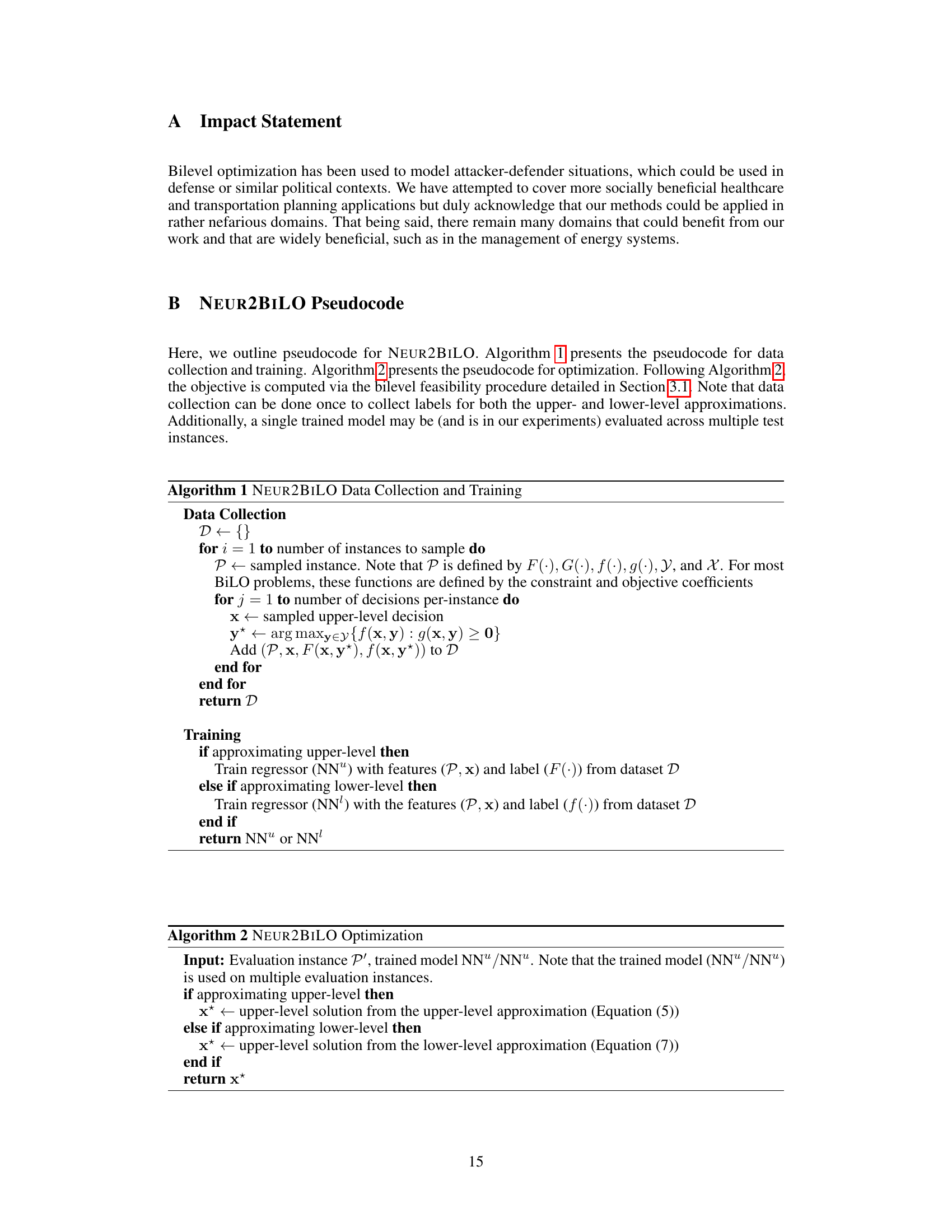

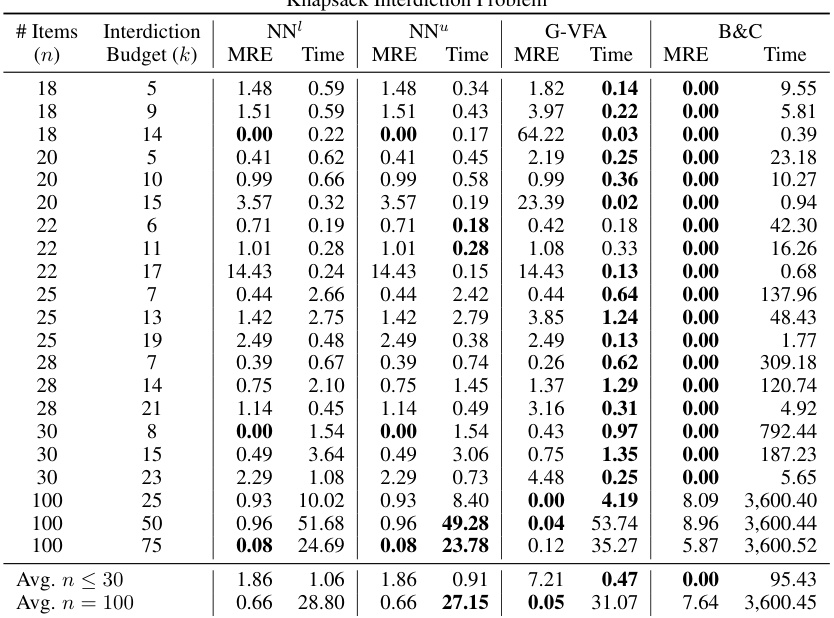

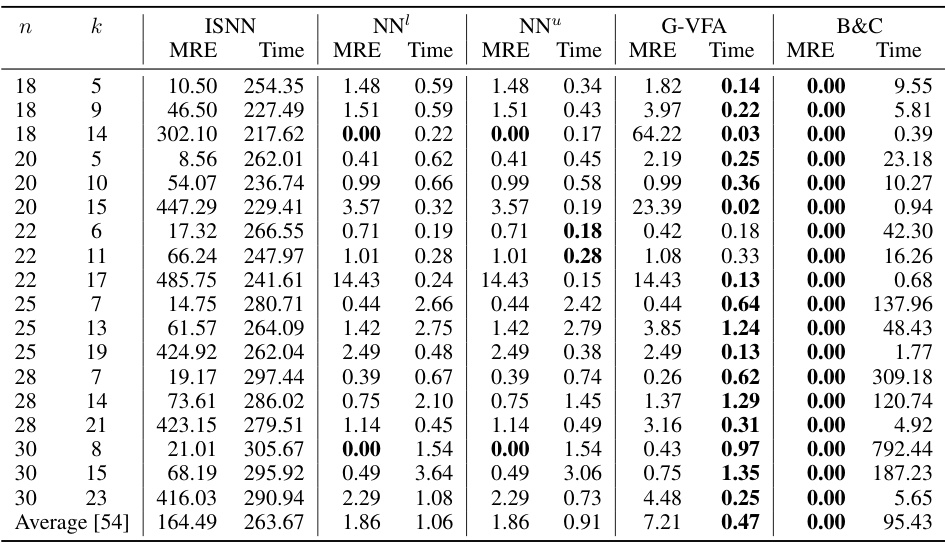

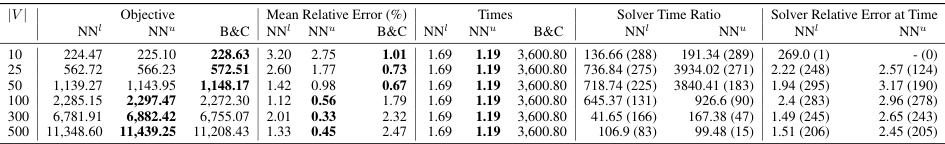

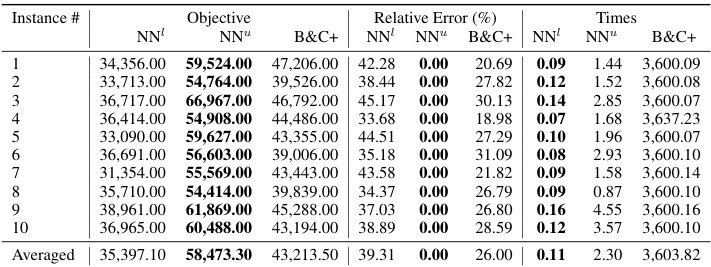

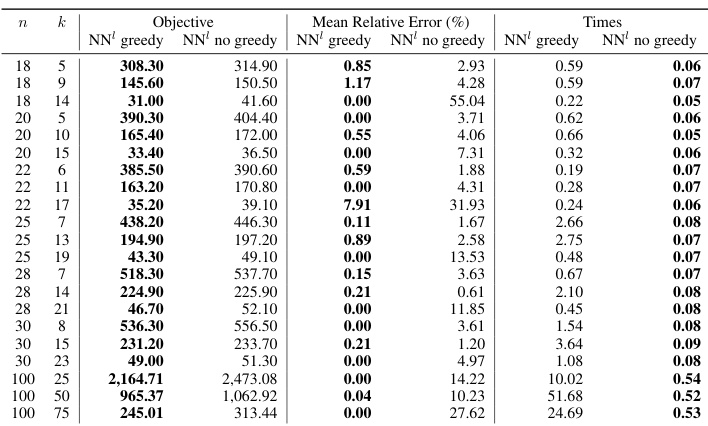

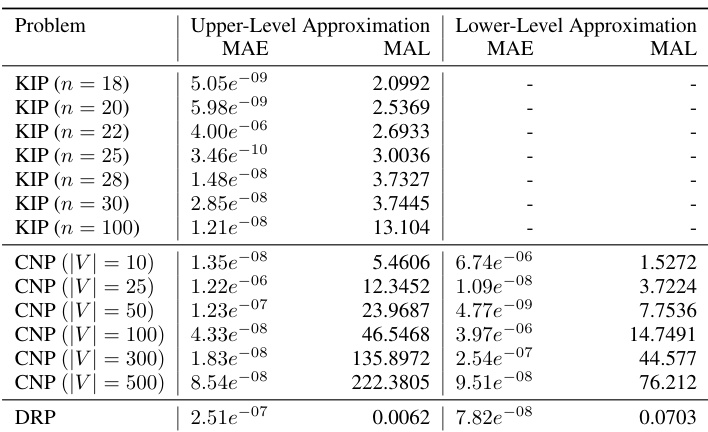

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). For KIP, results are shown for different problem sizes and budget constraints, comparing the neural network-based approach (NEUR2BILO) with a greedy value function approximation and a branch-and-cut method. For CNP and DNDP, the table presents average results for various problem instances and compares NEUR2BILO against other baselines. The table highlights the computational efficiency and solution quality of NEUR2BILO in comparison to established techniques.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving time for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). For KIP, results are shown for different problem sizes (number of items). The no-learning baseline G-VFA is included for comparison. For CNP and DNDP, problem instances are generated randomly according to procedures in the referenced literature. The table shows that the proposed method (NEUR2BILO) is competitive with or significantly outperforms state-of-the-art methods in terms of both solution quality and computation time.

The table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and average solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of NEUR2BILO’s upper-level and lower-level approximations against existing baselines (B&C, G-VFA, MKKT) for various problem sizes and parameters. The results show that NEUR2BILO is significantly faster than the baselines while maintaining competitive solution quality.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of the proposed Neural Bilevel Optimization (NEUR2BILO) framework (using both upper and lower-level approximations) against existing baselines (e.g., branch-and-cut algorithms). The table shows that NEUR2BILO achieves high-quality solutions much faster than traditional methods for all three problems, even with complex constraints.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of the proposed NEUR2BILO method (using both upper-level and lower-level neural network approximations, NN¹ and NN™) against existing baseline methods (B&C, G-VFA, and MKKT). The table shows that NEUR2BILO achieves high accuracy and significantly faster solving times, especially for larger problem instances. Different problem sizes and budget constraints are considered for each problem. The no-learning baseline, G-VFA, uses a simplified approach based on the greedy solution of the follower problem.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of the proposed NEUR2BILO method (using both upper-level and lower-level approximations) against existing baselines (B&C, G-VFA, MKKT). The table shows that NEUR2BILO achieves high accuracy within significantly less time compared to the baseline methods for the problems examined, even for large instances and non-linear problems.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of the proposed Neural Bilevel Optimization (NEUR2BILO) approach (using both upper-level and lower-level approximations) against existing baseline methods (Branch and Cut, G-VFA, MKKT). The table shows that NEUR2BILO generally achieves comparable or better solution quality with significantly faster solving times, especially for larger problem instances.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of the proposed NEUR2BILO method (using both upper and lower-level approximations) against existing baseline methods. The table shows that NEUR2BILO achieves high accuracy and speed, particularly compared to exact methods.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of the proposed NEUR2BILO method (using both upper and lower-level approximations) against existing baselines (B&C, G-VFA, MKKT) across different problem sizes and parameter settings. The table highlights the speed and accuracy of NEUR2BILO, particularly for larger and more complex instances.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). For KIP, results are shown for different problem sizes (number of items, n). For CNP, the results represent averages over 300 randomly sampled instances, and for DNDP, averages over 10 instances are shown. The table also includes a comparison with baseline methods (G-VFA for KIP and B&C for CNP). The budget constraints for each problem are also specified.

This table summarizes the performance of NEUR2BILO and baseline methods on three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It shows the mean relative error (MRE) and solution times for each method and problem instance size, illustrating NEUR2BILO’s efficiency and solution quality compared to state-of-the-art techniques.

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of the proposed Neural Bilevel Optimization (NEUR2BILO) method (using both upper and lower-level approximations) against existing baseline methods for each problem. The table shows that NEUR2BILO achieves high accuracy within significantly shorter computation times, especially as the problem size increases. The baseline methods used vary depending on the problem; for KIP, it’s branch and cut (B&C), for CNP it’s B&C again, for DNDP it’s modified KKT conditions (MKKT).

This table presents the mean relative error (MRE) and solving times for three different bilevel optimization problems: Knapsack Interdiction Problem (KIP), Critical Node Problem (CNP), and Discrete Network Design Problem (DNDP). It compares the performance of the proposed NEUR2BILO method (using both upper and lower-level approximations) against existing baseline methods. The table highlights the computational efficiency and solution quality of NEUR2BILO, especially when compared to exact methods which struggle to scale to larger problem sizes. Note that different numbers of instances are used for each problem, along with varying solution methods and data generation procedures.

Full paper#