↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Hugging Face ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Open-vocabulary object counting, crucial for various applications, faces challenges in accuracy and generality. Existing methods struggle to accurately count objects when only given textual descriptions or a few visual examples. They also often lack the flexibility to combine both types of input for improved performance. This limits their applicability to real-world scenarios where data might be incomplete or ambiguous.

COUNTGD addresses these challenges with a novel multi-modal approach. By integrating both text and visual exemplar inputs, COUNTGD achieves state-of-the-art accuracy on multiple benchmarks, demonstrating superior performance to previous text-only or visual-exemplar-only methods. The model leverages a pre-trained vision-language foundation model, incorporating new modules to seamlessly fuse text and visual information, enhancing its ability to specify the target object and achieve higher counting accuracy. This significantly enhances the flexibility and applicability of open-world object counting.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly advances the field of open-vocabulary object counting by introducing a novel multi-modal approach. COUNTGD improves accuracy and generality by allowing the model to interpret both text and visual prompts, pushing the state-of-the-art in several benchmark datasets. This opens exciting avenues for further research into multi-modal learning and its application in complex computer vision tasks.

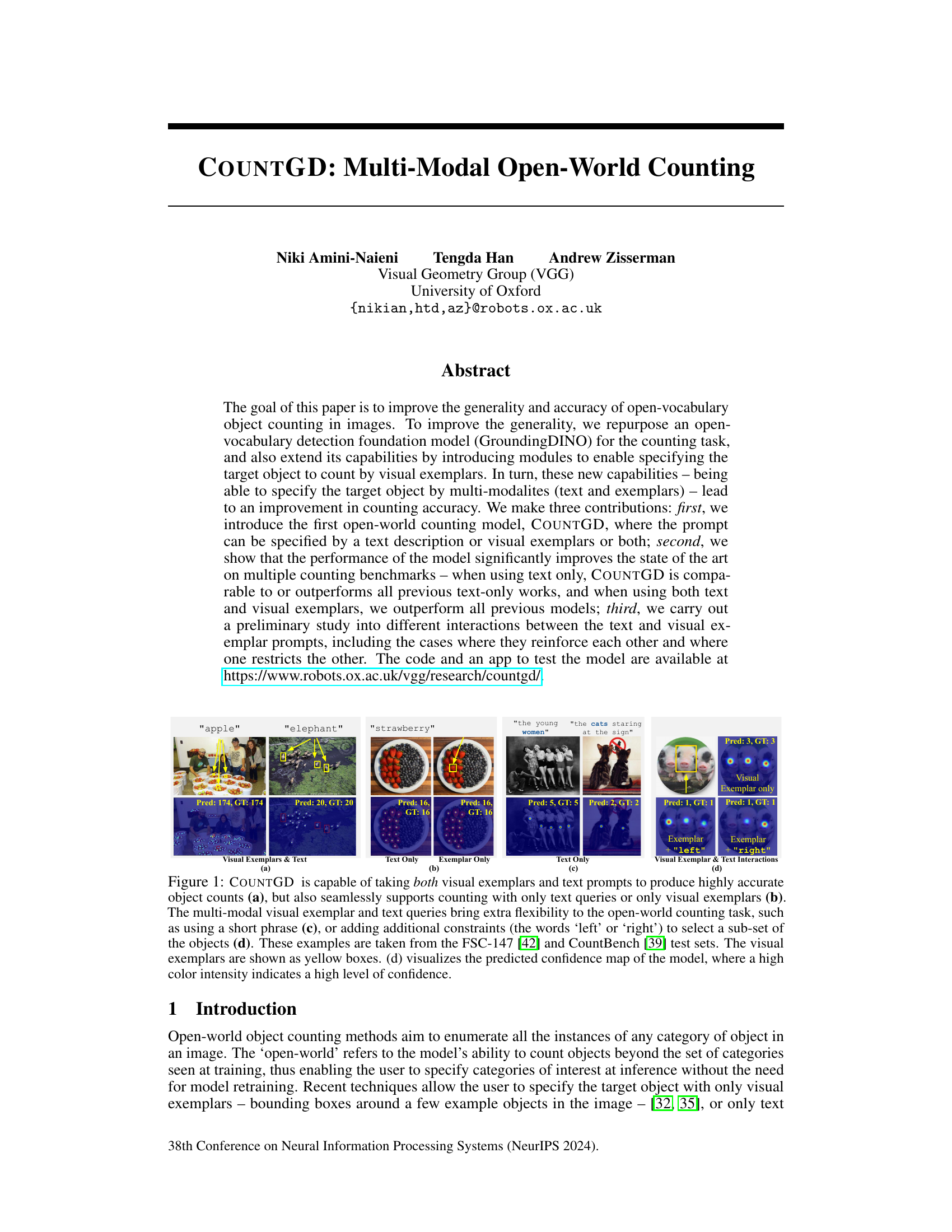

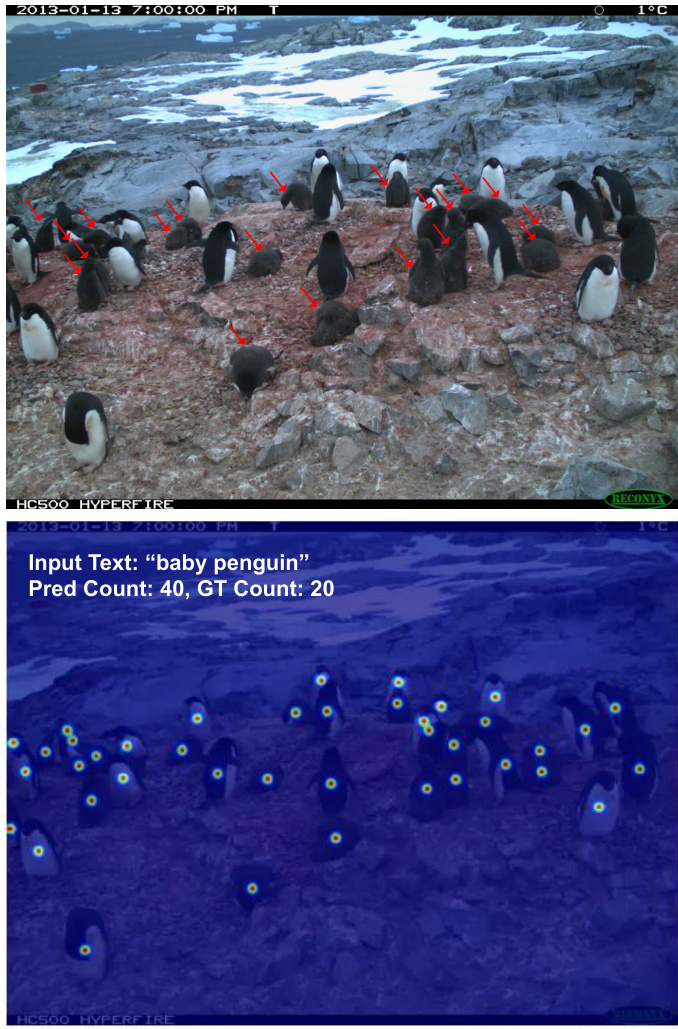

Visual Insights#

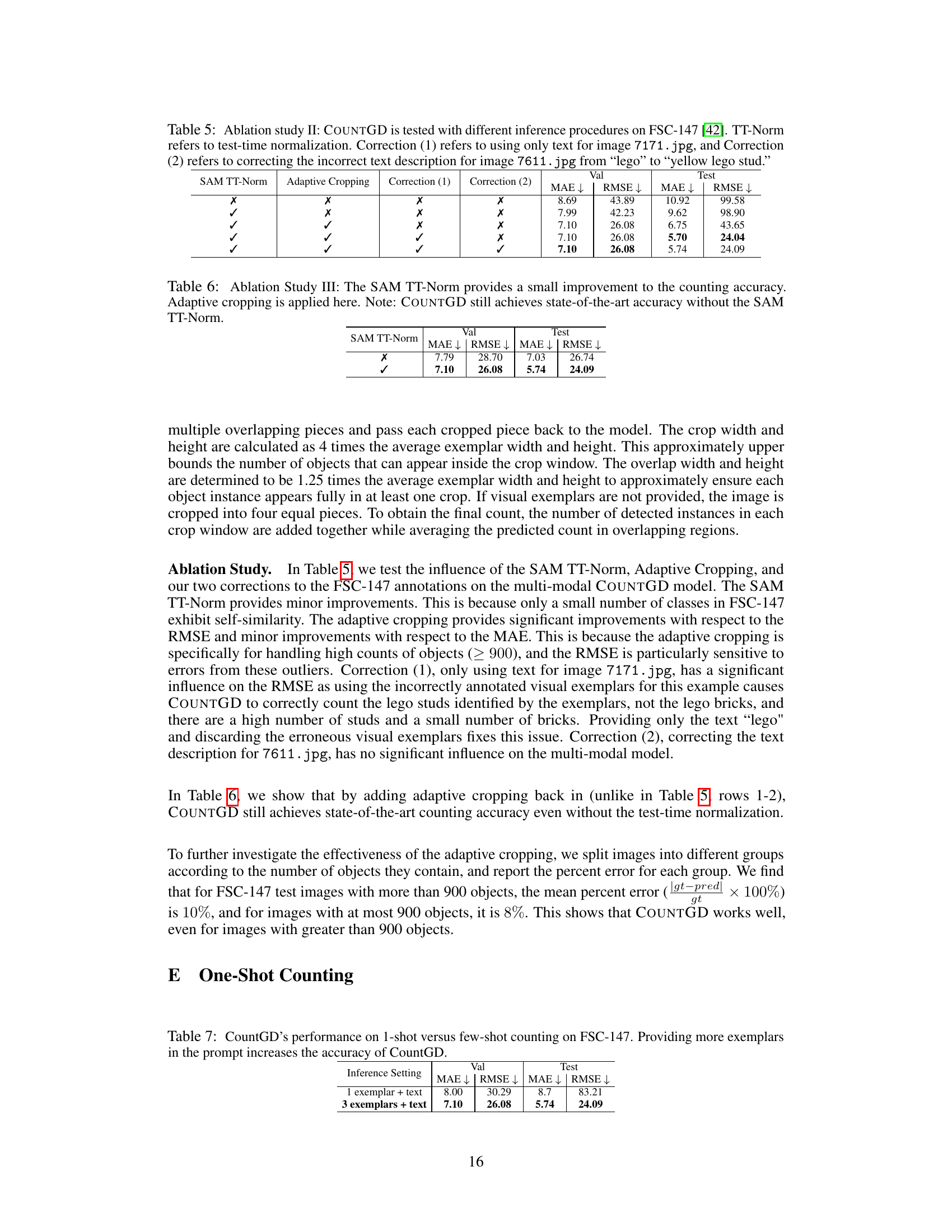

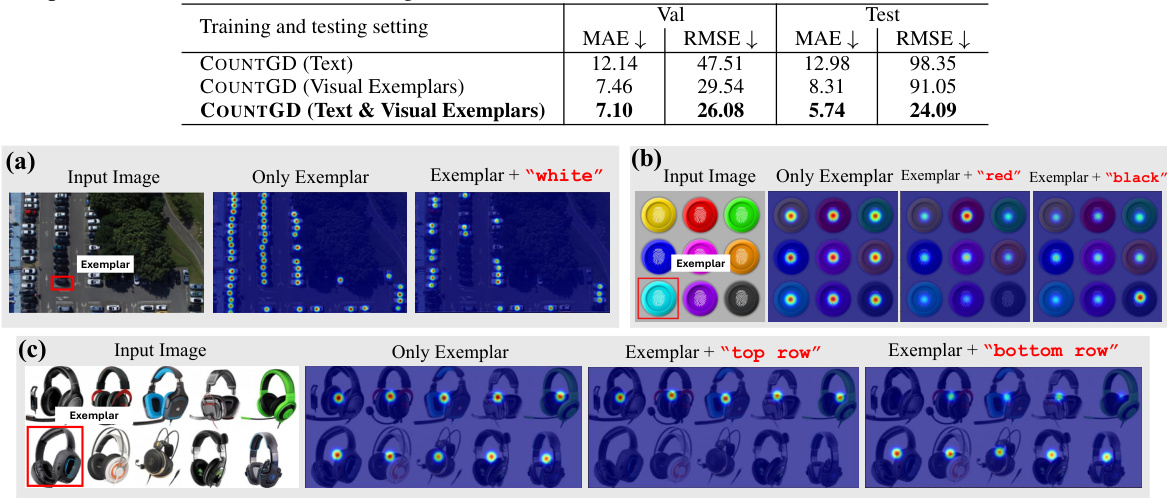

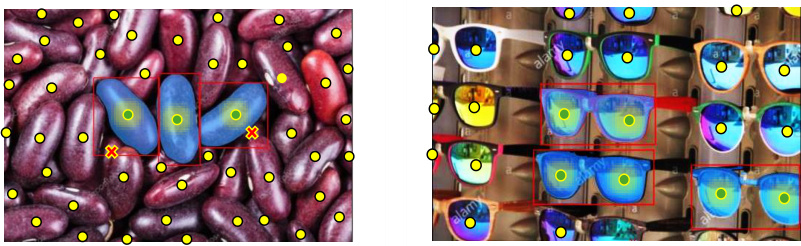

This figure demonstrates the capabilities of the COUNTGD model in open-world object counting. It showcases the model’s ability to accurately count objects using various combinations of input: text descriptions only, visual exemplars only, and a combination of both. The multi-modal approach (text and exemplars) offers enhanced flexibility, allowing for more precise object selection using constraints like spatial location (’left’, ‘right’). Examples are drawn from the FSC-147 and CountBench datasets, with visual exemplars highlighted by yellow bounding boxes. The heatmap in (d) visually represents the model’s confidence in its predictions.

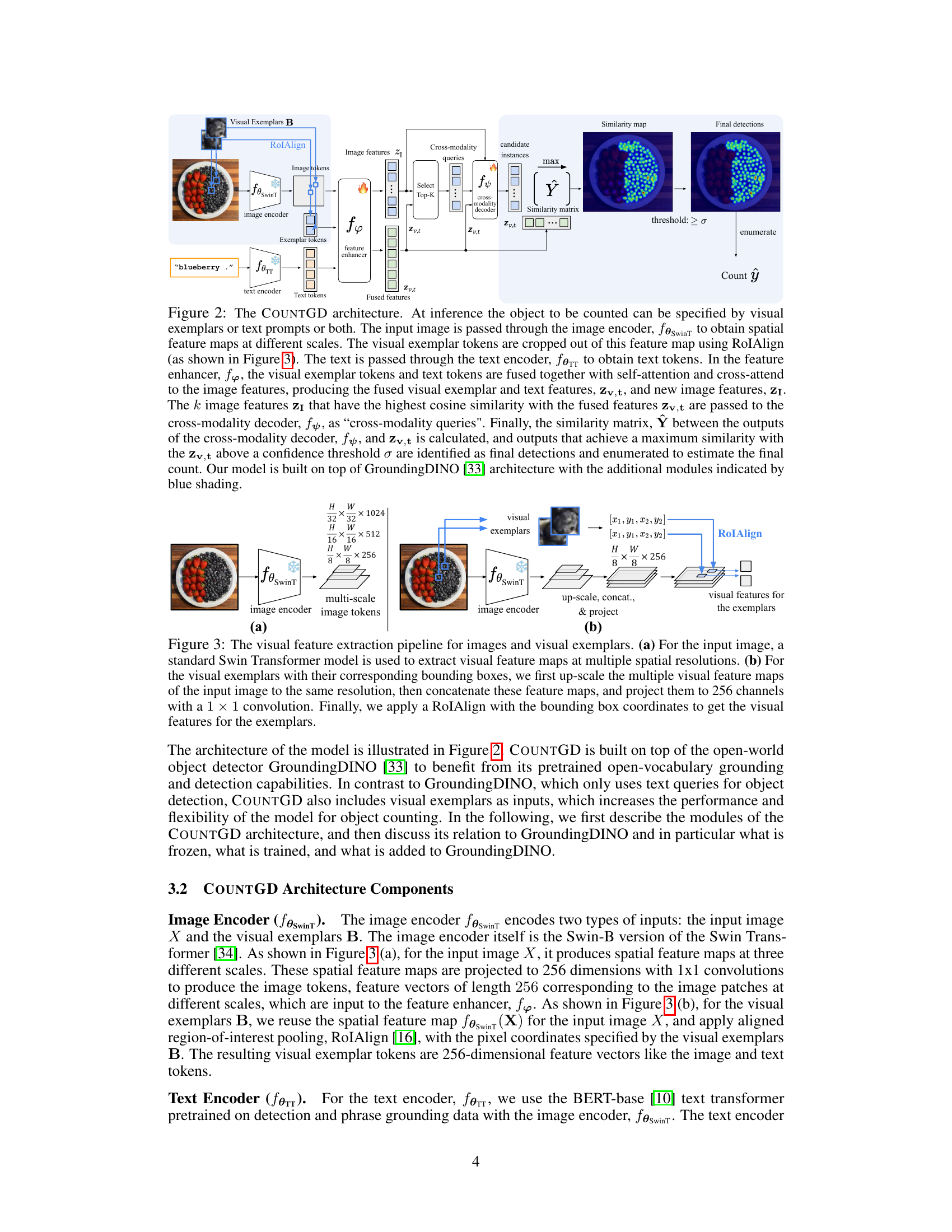

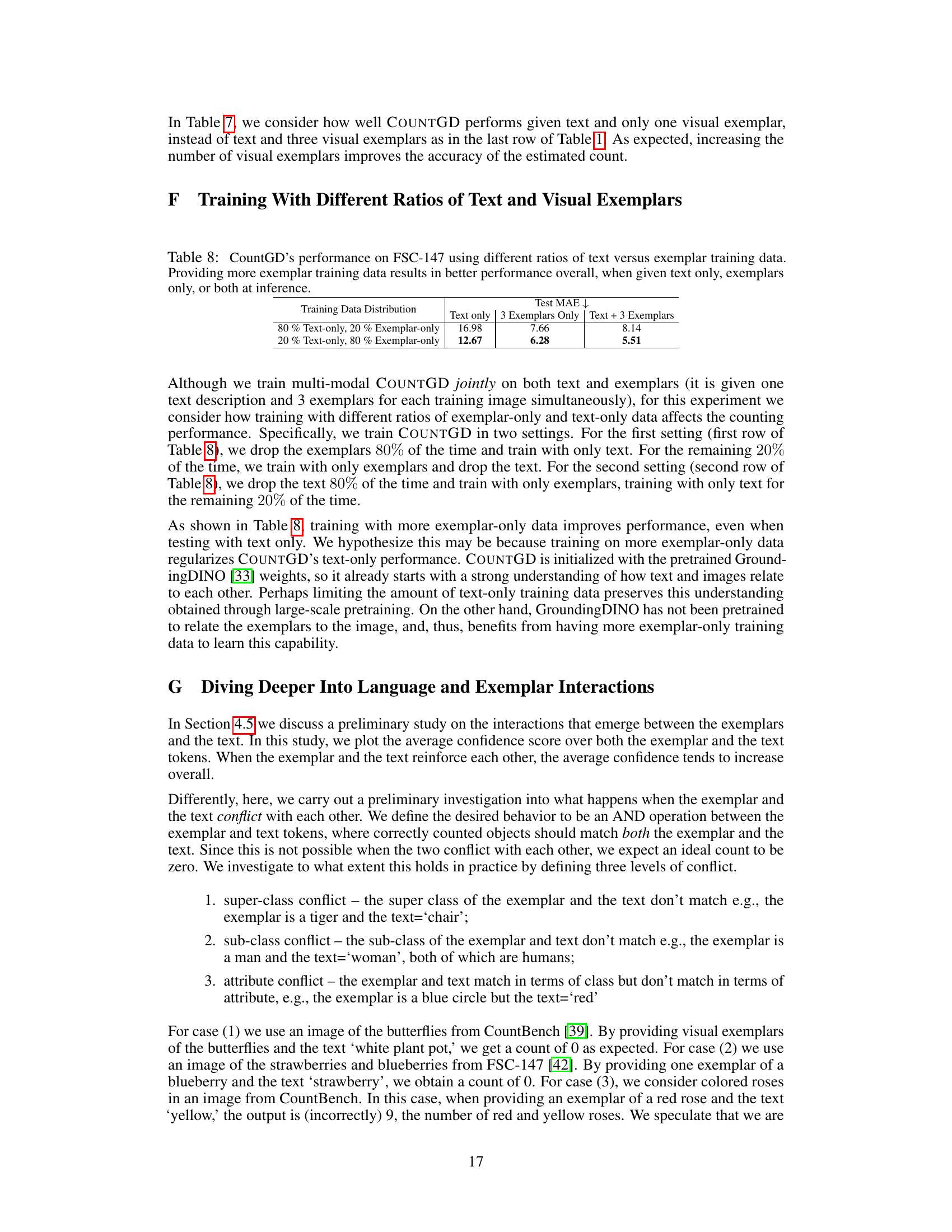

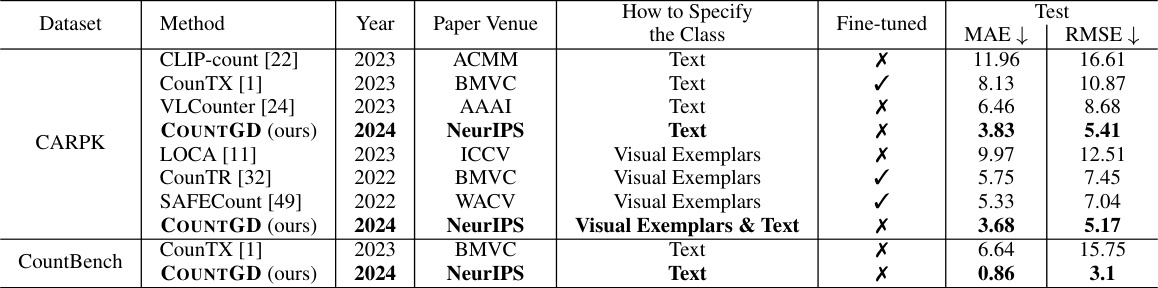

This table compares the performance of COUNTGD with other state-of-the-art open-world object counting methods on the FSC-147 dataset. It shows COUNTGD’s superior accuracy when using both text and visual exemplars, and its comparable performance to the best text-only methods when only using text. The table highlights COUNTGD’s advancement in open-world object counting.

In-depth insights#

Multimodal Counting#

Multimodal counting, as a concept, significantly advances object counting by integrating diverse data modalities, such as text descriptions and visual exemplars. This approach enhances both the generality and accuracy of the task. Generality is improved because the system can accept various forms of input, allowing users to specify the target objects in flexible ways. The accuracy benefits because combining modalities provides richer and more precise information about the target object than relying on a single modality alone. Visual exemplars, for example, offer detailed visual characteristics while text descriptions offer semantic information. The synergistic use of both, as seen in COUNTGD, yields state-of-the-art results. Challenges remain in resolving conflicts between modalities (e.g., text specifying a color that differs from visual exemplars) and in handling very fine-grained counting scenarios where subtle visual distinctions make accurate object enumeration difficult. Despite such challenges, multimodal counting represents a crucial step toward building more robust and versatile object counting systems.

GroundingDINO#

GroundingDINO, as a foundational vision-language model, plays a crucial role in the COUNTGD architecture. Its pre-trained capabilities in open-vocabulary grounding and object detection are leveraged to improve the generality and accuracy of COUNTGD’s object counting. COUNTGD builds upon GroundingDINO by introducing modules to handle visual exemplars, enabling multi-modal prompts (text and images). The integration of GroundingDINO allows COUNTGD to handle the open-world nature of the counting problem, significantly enhancing its ability to count objects beyond those seen during training. However, it’s also important to note that GroundingDINO’s limitations, such as potential bias in its pre-training data, could influence COUNTGD’s performance. Therefore, understanding GroundingDINO’s strengths and weaknesses is crucial for a comprehensive evaluation of COUNTGD’s capabilities and limitations.

Visual-Text Fusion#

Visual-text fusion is a crucial aspect of multimodal learning, aiming to integrate visual and textual information for enhanced understanding. Effective fusion methods are essential for leveraging the complementary strengths of both modalities, such as visual details and semantic context provided by text. Approaches often involve joint embedding techniques, where visual and textual features are mapped into a shared representation space for comparison and combined analysis. Challenges include aligning the different granularities of visual and textual data and addressing potential biases stemming from inconsistencies in data representation or labeling. The success of fusion depends heavily on the quality of individual visual and textual feature extractors, as well as the chosen fusion strategy. Recent advancements focus on attention mechanisms to adaptively weight the contribution of different modalities and transformers for effective sequential processing of multimodal data.

Benchmark Results#

A dedicated ‘Benchmark Results’ section would ideally present a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed multi-modal open-world counting model (COUNTGD) against existing state-of-the-art techniques. This would involve presenting quantitative results on multiple established benchmarks (e.g., FSC-147, CARPK, CountBench), clearly showing COUNTGD’s performance in terms of metrics such as Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). Key aspects to highlight include comparisons under various prompting modalities (text-only, exemplar-only, and multimodal). The analysis should also demonstrate the model’s generalizability across different datasets and its robustness to variations in object density and image complexity. Visualizations, such as tables and graphs, would significantly enhance understanding. A discussion of the results, explaining any significant performance differences and potential limitations, is crucial. Furthermore, a thorough ablation study analyzing the contribution of each component (e.g., visual exemplar module, text encoder, fusion mechanism) to the overall performance is vital for establishing the efficacy and validity of the proposed model’s design choices.

Future Extensions#

Future extensions of this multi-modal open-world counting model, COUNTGD, could explore several promising avenues. Improving the robustness to challenging scenarios such as significant occlusions, extreme variations in lighting, and dense object arrangements is crucial for broader real-world applicability. Enhancing the model’s capability to handle diverse object interactions would allow for accurate counting in complex scenes with overlapping or intertwined objects. Investigating different methods for fusing textual and visual information, potentially incorporating more sophisticated attention mechanisms, could boost accuracy and efficiency. Exploring the scalability of COUNTGD to very large images and video sequences is essential. Finally, extending the framework to count objects with finer-grained attributes or across different object classes simultaneously is another potentially impactful area of investigation. Addressing these points would significantly enhance the capabilities of COUNTGD, making it a more versatile and widely applicable solution for a variety of open-world counting tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

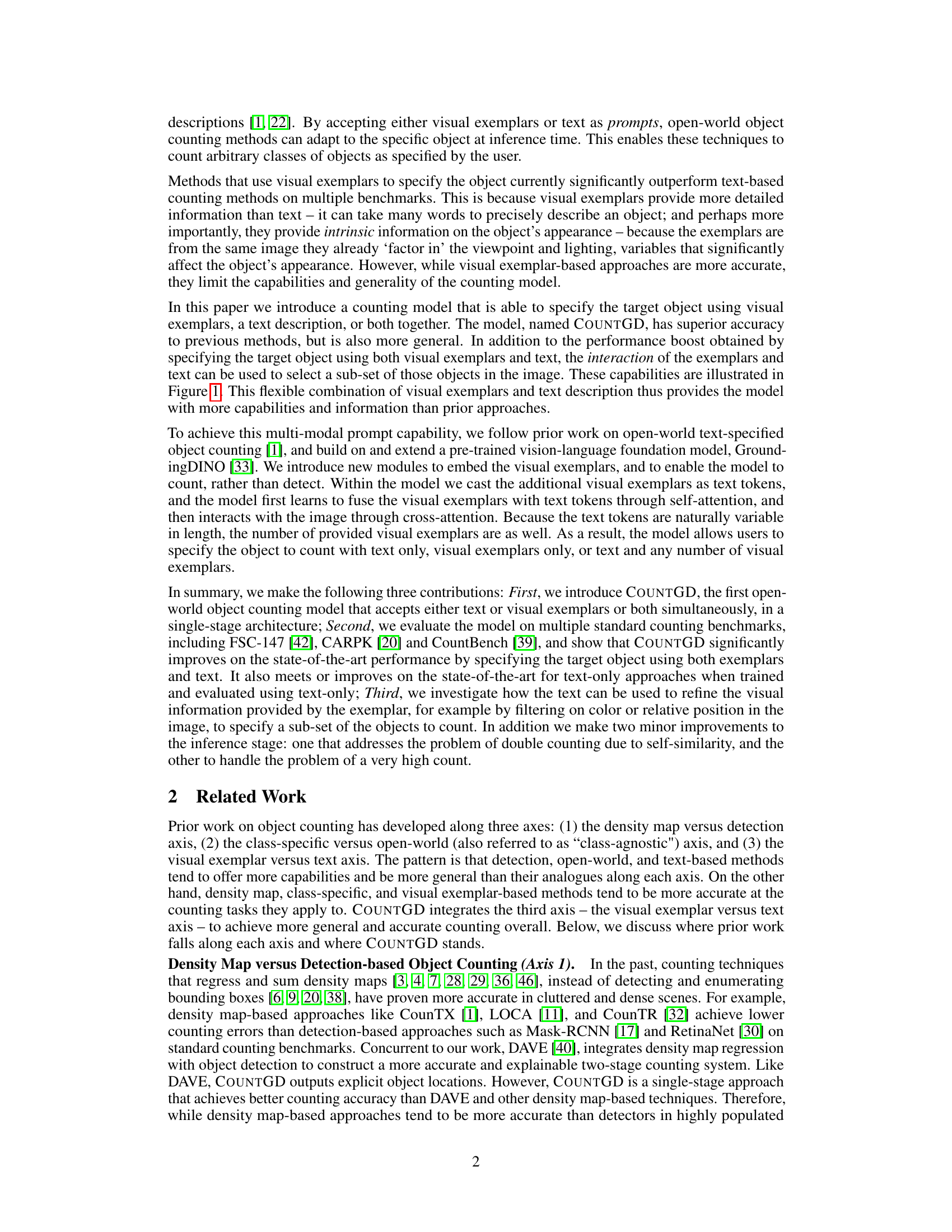

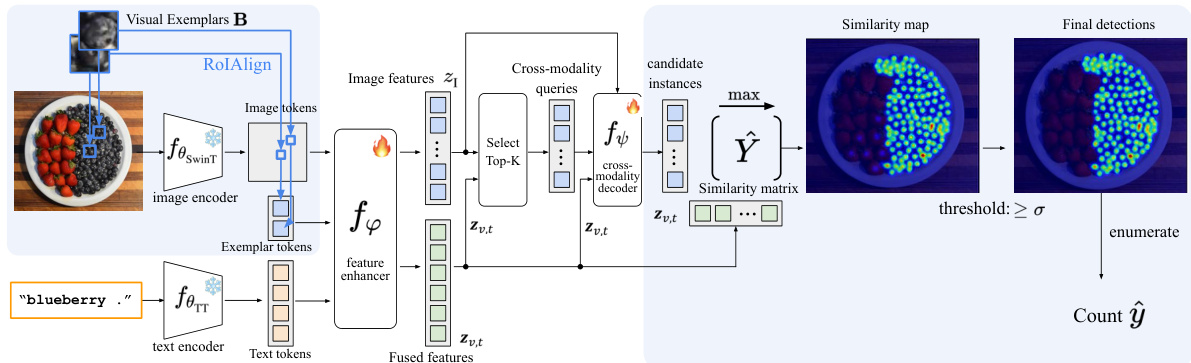

This figure illustrates the COUNTGD architecture, which is a multi-modal open-world object counting model. The model takes as input an image, text description of the target object, and/or visual exemplars (bounding boxes around example instances). The image is processed through a Swin Transformer-based image encoder to extract multi-scale feature maps. Visual exemplars are extracted using RoIAlign, and the text is processed through a BERT-based text encoder. A feature enhancer module fuses the image, text, and visual exemplar features using self- and cross-attention mechanisms. A cross-modality decoder then processes the fused features to generate a similarity map, where high-similarity regions correspond to instances of the target object. These instances are enumerated to obtain the final object count. The architecture extends GroundingDINO by incorporating modules for handling visual exemplars and fusing multi-modal information.

This figure shows how the model extracts visual features from both the input image and the visual exemplars. For the input image (a), a Swin Transformer extracts multi-scale feature maps, which are then projected to 256 dimensions. For the visual exemplars (b), the image features are first upscaled to the same resolution, then concatenated, projected to 256 dimensions, and finally, RoIAlign is used to extract features within the bounding boxes of the exemplars.

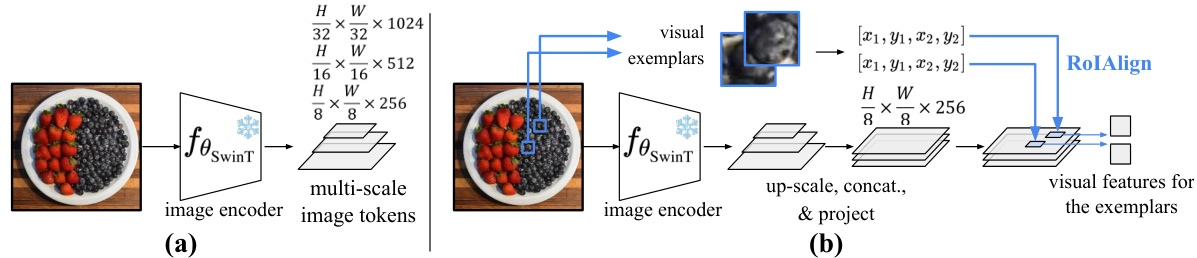

This figure shows examples of COUNTGD’s counting performance using different input modalities. (a) demonstrates accurate counting with both text and visual exemplars. (b) shows that COUNTGD can also count using text-only or visual exemplar-only prompts. (c) illustrates the flexibility of using short phrases as input. Finally, (d) shows how COUNTGD can use text to refine the selection of objects specified by visual exemplars, visualizing the confidence map of the model’s predictions.

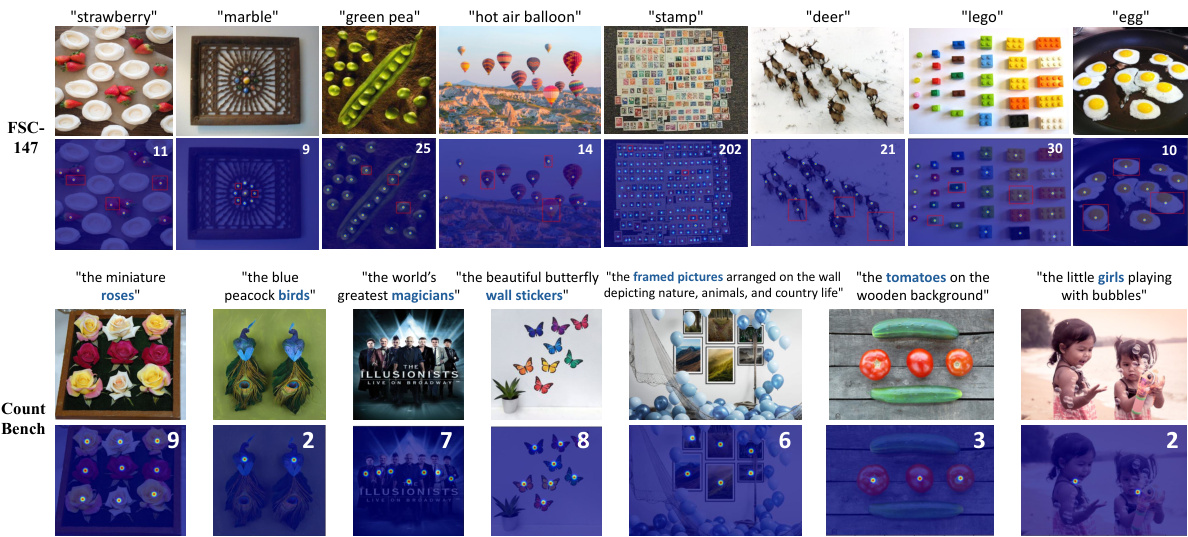

This figure demonstrates the interaction between visual exemplars and text in COUNTGD. It visually shows how using both modalities allows for more specific object counting than either method alone. (a) and (b) illustrate how shape can be specified via an exemplar, while color is modified by additional text input, showing that the model only counts objects of the specified color matching the visual exemplars. (c) shows how spatial location (top/bottom row) can be selected via text, while shape is still specified by the visual exemplar, resulting in counting only the specific objects within the specified location and shape.

This figure shows examples of the COUNTGD model’s ability to count objects accurately using different input modalities. Subfigure (a) demonstrates the model’s ability to accurately count objects using both visual exemplars (yellow boxes) and text prompts. Subfigure (b) showcases the model’s functionality when using only text queries or visual exemplars. Subfigure (c) illustrates the flexibility of using short text phrases to specify the objects to count. Lastly, subfigure (d) visualizes the predicted confidence map, illustrating the model’s high confidence in its predictions by means of color intensity.

This figure demonstrates the results of an experiment designed to test the model’s ability to handle conflicting information from visual exemplars and text prompts. Three scenarios are presented: butterflies with text prompt “white plant pot”, strawberries and blueberries with text prompt “strawberry”, and roses with text prompt “yellow”. In the first two cases, the model correctly identifies no instances matching both the visual exemplar and text description. However, in the third case, the model incorrectly counts nine roses even though the text specified only yellow roses, demonstrating a limitation in handling conflicting information. The top row shows the input, with red boxes highlighting the exemplar selections. The bottom row displays the model’s output with numbers indicating the detected objects.

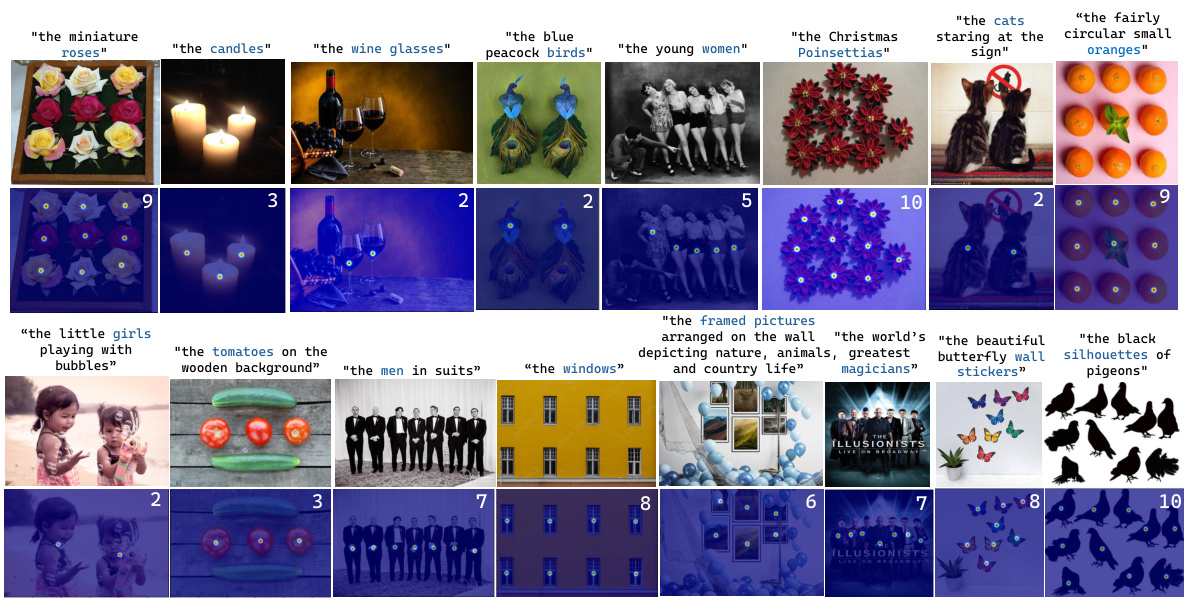

This figure shows qualitative examples of object counting results using the COUNTGD model. The top row shows examples from the FSC-147 dataset, where the model was trained and tested with both text and visual exemplars. The input text is provided above each image, and red boxes indicate the visual exemplars. The bottom row presents zero-shot results from the CountBench dataset; here, only the text prompts were used. The model achieves 100% accuracy across all examples. The figure highlights the model’s ability to accurately count objects even when multiple object types are present.

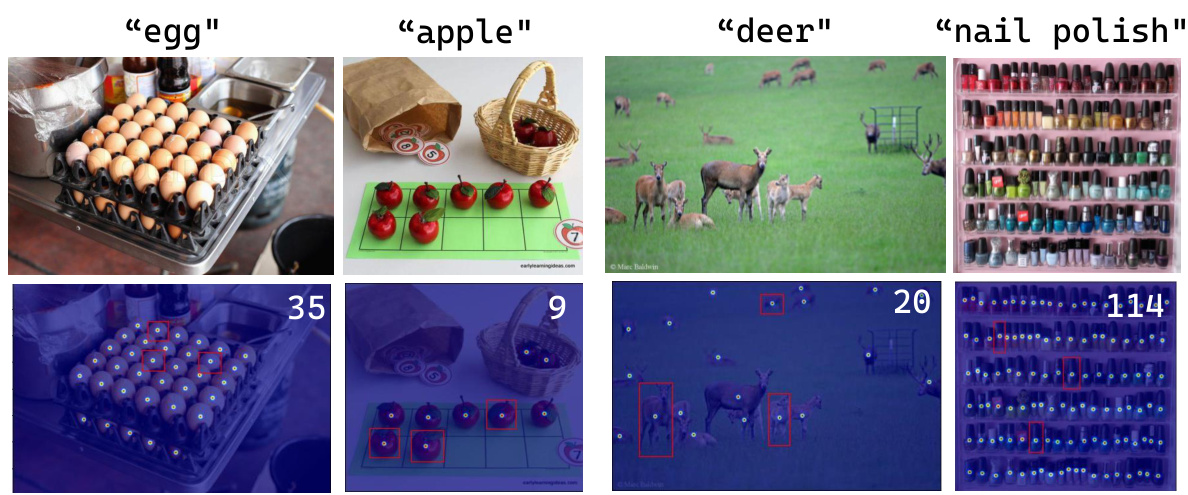

This figure shows four examples from the FSC-147 test set where the COUNTGD model correctly identifies the number of objects in each image. The top row displays the input images, with the corresponding text prompts shown above each image. The bottom row shows the heatmap of predictions overlaid onto the input images. The red bounding boxes indicate the objects that were detected by the model, and the numbers in the bottom right corner of each image represent the final object counts predicted by the model. The model accurately counts eggs, apples, deer, and nail polish in each of the four example images.

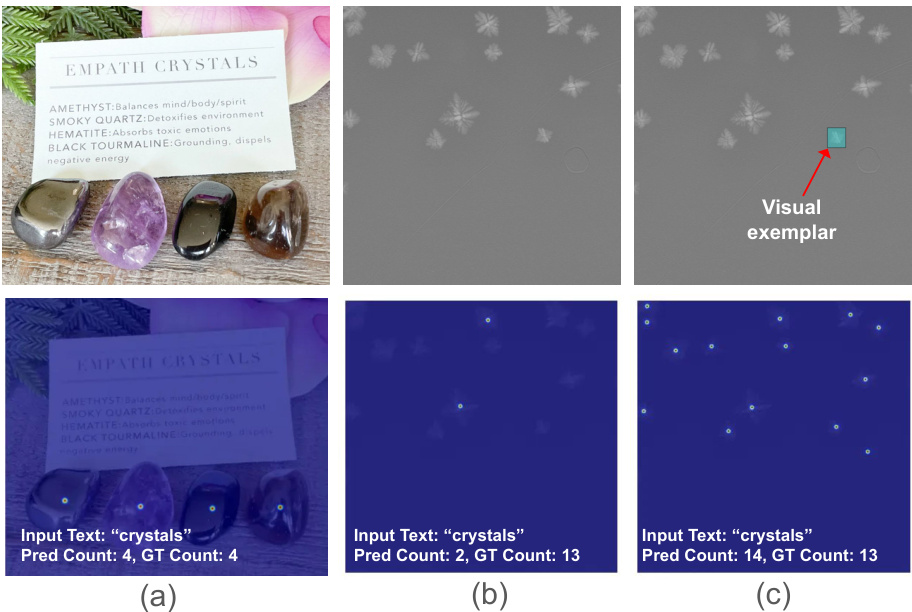

This figure shows three examples where the model’s counting performance is affected by the input modality and whether a visual exemplar is provided. In the first example, only text is provided, and the model accurately counts the number of crystals. In the second example, only text is provided, and the model fails to accurately count the crystals in an X-ray image where they appear less distinct. In the third example, both text and a visual exemplar are provided, and the model successfully counts the crystals.

This figure demonstrates the capabilities of the COUNTGD model in open-world object counting. It showcases four scenarios: (a) Using both visual exemplars (yellow boxes) and text to achieve highly accurate object counts. (b) Demonstrating the model’s ability to count using text-only or visual exemplar-only prompts. (c) Highlighting flexibility by using short phrases for object specification. (d) Illustrating refined counting by adding spatial constraints (e.g., ’left’, ‘right’) to select subsets of objects, along with a visualization of the model’s confidence map.

More on tables

This table compares the performance of COUNTGD against other state-of-the-art open-world object counting methods on two benchmark datasets: CARPK and CountBench. The top section shows results for CARPK, comparing COUNTGD’s performance using only text and using both text and visual exemplars against other models using either method. The bottom section shows results for CountBench, comparing COUNTGD’s zero-shot text-only performance against the best performing text-only method.

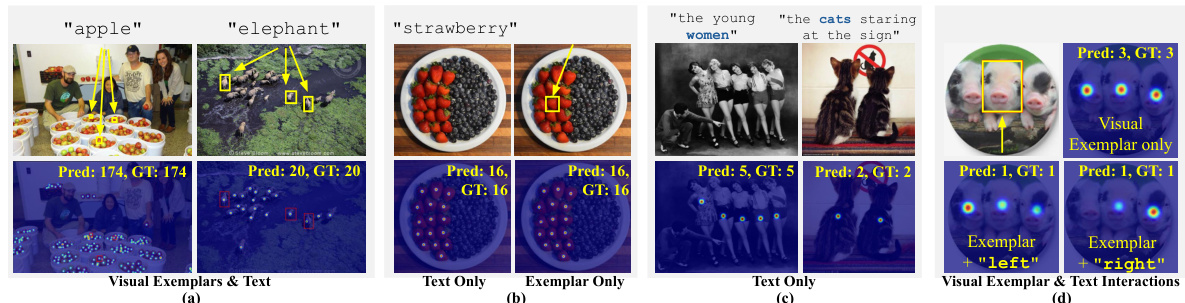

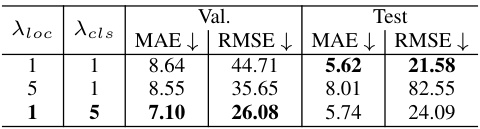

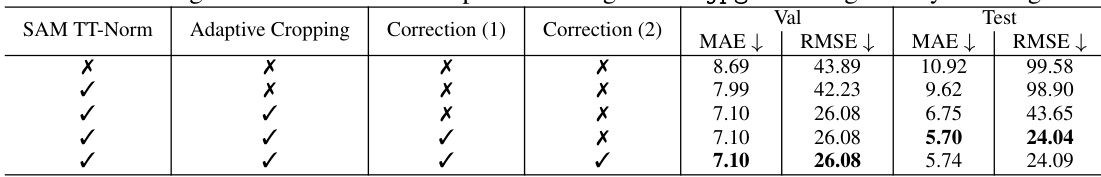

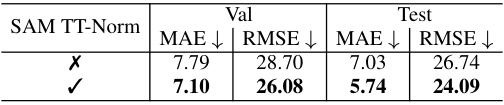

This table presents the ablation study on the impact of different inference procedures on COUNTGD’s performance. The study includes the test-time normalization (TT-Norm) technique, a correction for incorrectly labeled visual exemplars in image 7171.jpg (using only text instead of both text and visual exemplars), and a correction for an incorrect text description in image 7611.jpg (changing ’lego’ to ‘yellow lego stud’). The results, measured by Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE), are reported for both the validation and test sets of the FSC-147 dataset. The table shows how each correction or technique impacts model accuracy.

This table presents an ablation study on the COUNTGD model’s performance using different inference methods. It shows the impact of using the SAM TT-Norm for handling self-similarity, the use of adaptive cropping for managing a large number of objects, and corrections made to the dataset (correcting incorrect visual exemplars and text descriptions). The results are reported in terms of Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) on both the validation and test sets of the FSC-147 dataset.

This table presents the ablation study on the COUNTGD model’s performance using different inference procedures. It shows the impact of using SAM TT-Norm, adaptive cropping, and corrections to the FSC-147 dataset on the model’s accuracy, measured by MAE and RMSE on both validation and test sets. The results demonstrate the effect of each modification individually and in combination.

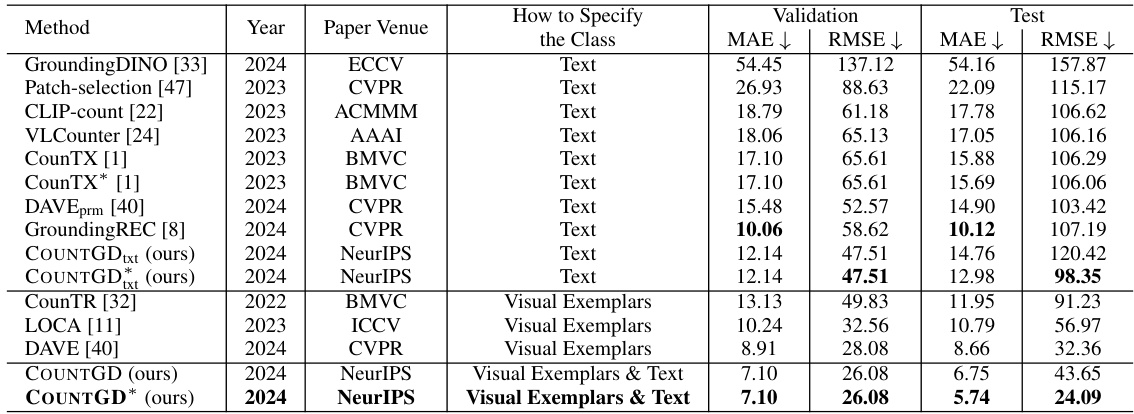

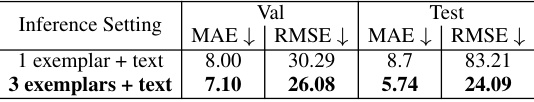

This table presents the results of a comparison between one-shot and few-shot counting experiments using the COUNTGD model on the FSC-147 dataset. It shows that increasing the number of visual exemplars provided as input to the model improves counting accuracy, as measured by Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The table highlights the trade-off between the number of exemplars used and the resulting counting accuracy.

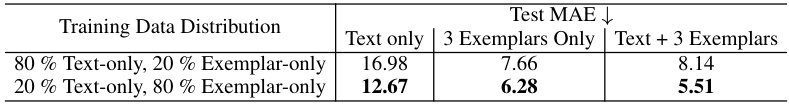

This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted to evaluate the impact of different training data ratios on the performance of the COUNTGD model. The model was trained with varying proportions of text-only and exemplar-only data. The test performance (measured by Mean Absolute Error or MAE) is reported for three different inference settings: using text only, using exemplars only, or using both text and exemplars. The results demonstrate that increasing the proportion of exemplar-only data in the training set leads to improved overall performance, regardless of the inference setting.

Full paper#