TL;DR#

Protecting the copyright of high-quality public datasets is crucial for the advancement of deep learning research. Existing methods for dataset ownership verification (DOV) rely on watermarks embedded within the dataset, but these methods are vulnerable because the watermark itself can be revealed during the verification process, potentially jeopardizing security. This can lead to unauthorized use and copyright infringement. This vulnerability necessitates a new approach that prioritizes security and privacy.

ZeroMark offers a solution by performing ownership verification without directly using watermarks. This innovative approach leverages the inherent properties of deep neural networks (DNNs) trained on watermarked datasets. It uses boundary samples and their gradients, calculated without exposing watermarks, to determine whether a model was trained on the protected dataset. The method is shown to be effective and resistant to common attacks. This contribution is important to researchers as it advances the field of data security and protection, introducing new methods to protect intellectual property rights while maintaining privacy.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses a critical challenge in dataset ownership verification: existing methods often compromise privacy by revealing watermarks. By proposing ZeroMark, a novel approach, this research opens up avenues for more secure and robust copyright protection of datasets, driving further research in secure machine learning and data provenance.

Visual Insights#

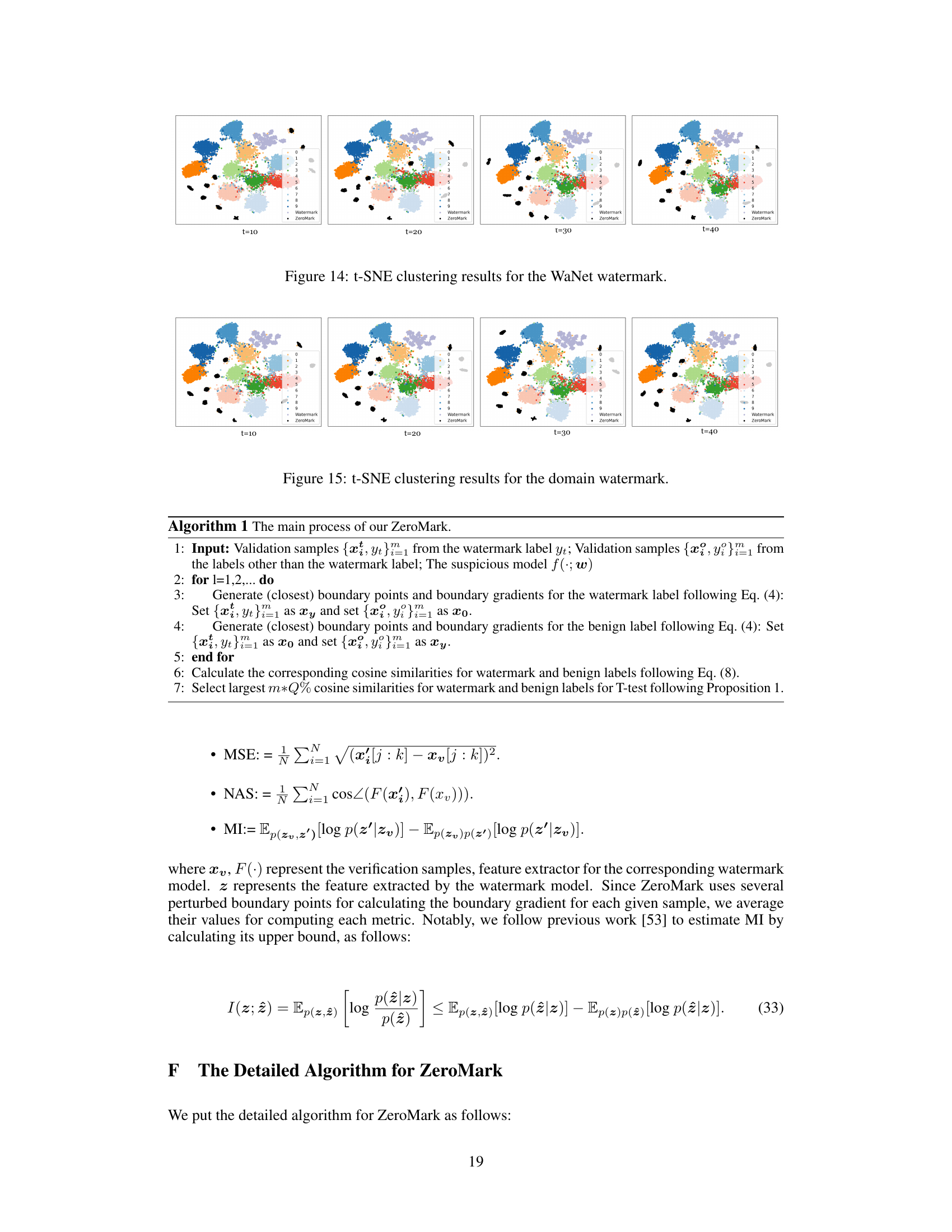

🔼 This figure compares existing Dataset Ownership Verification (DOV) methods with the proposed ZeroMark method. Existing DOV methods use watermarked samples directly for verification, making them vulnerable if the watermark is discovered. ZeroMark addresses this by using boundary samples instead, which don’t reveal the specific watermark, thus protecting the dataset’s copyright more effectively. The figure visually represents the steps in both approaches: watermark embedding, and verification with either watermarked samples or boundary samples.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of existing dataset ownership verification (DOV) methods and our ZeroMark. In the verification phase, existing DOV approaches directly exploit watermarked samples for verification purposes. In contrast, ZeroMark queries the suspicious model with boundary samples without disclosing dataset-specified watermarks to safeguard the verification process.

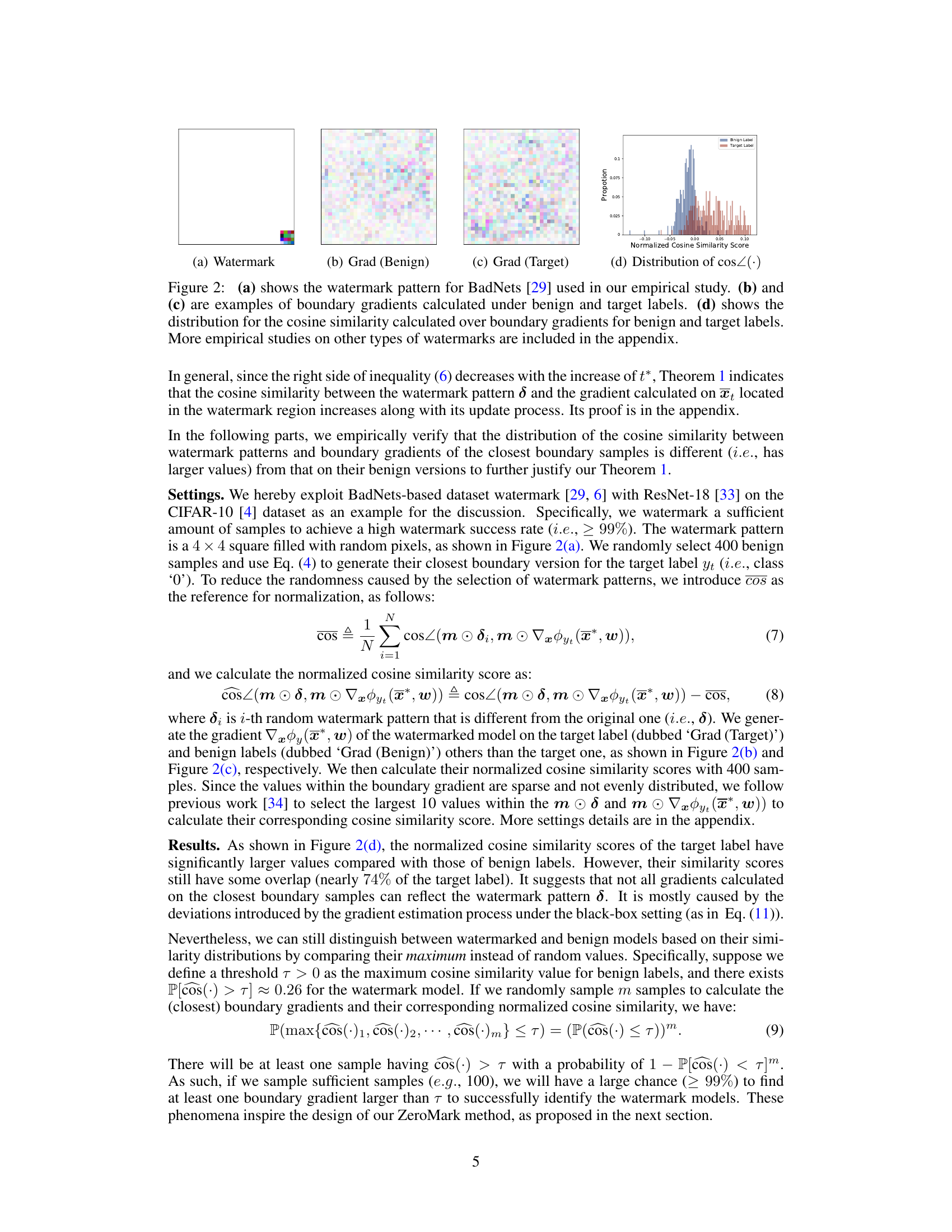

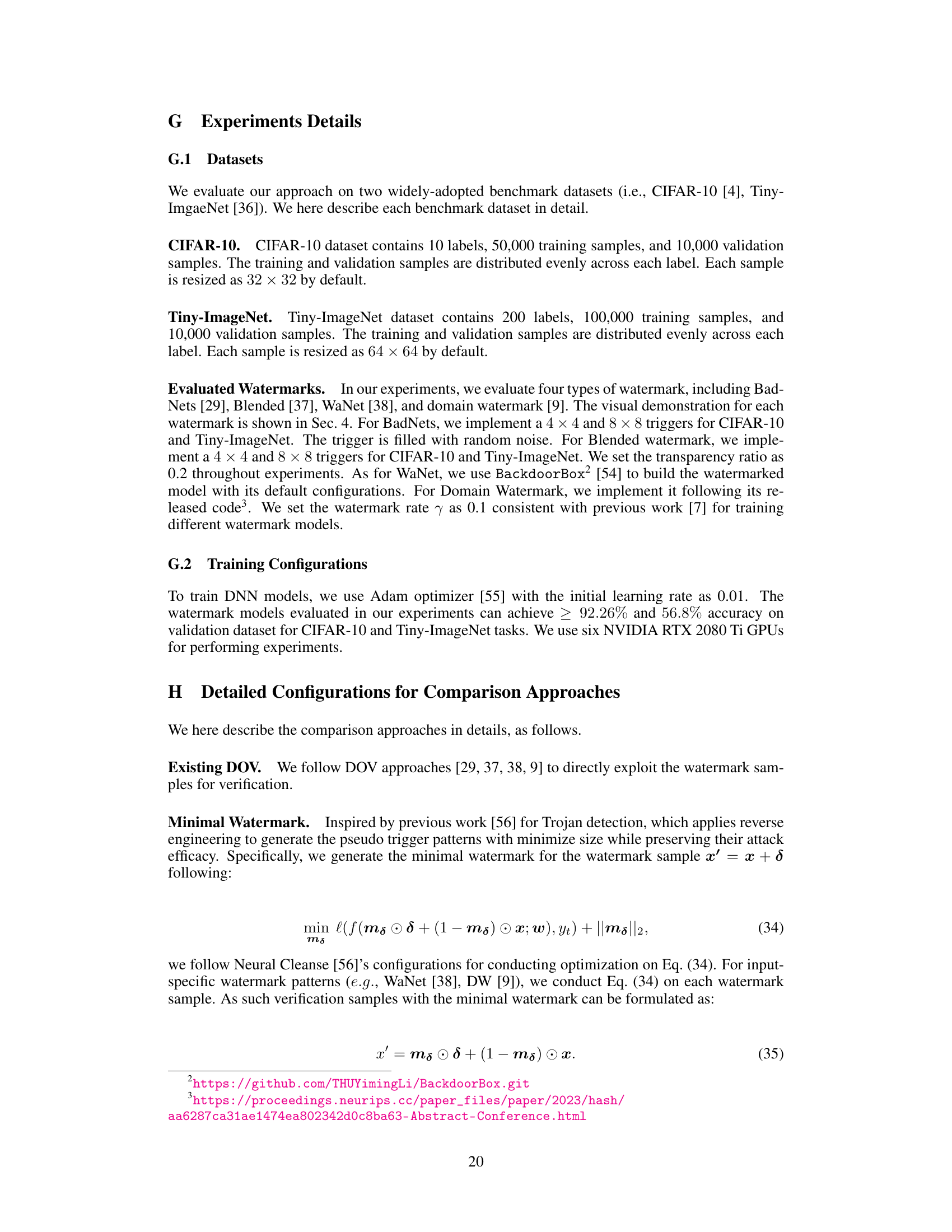

🔼 This table presents the average of the largest Q% cosine similarity scores achieved by the proposed ZeroMark method across different watermarking techniques (BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) and on two datasets (CIFAR-10, TinyImageNet). The scores are separated into ‘Benign’ (non-watermarked) and ‘Target’ (watermarked) labels to show the distinguishing capability of ZeroMark in identifying watermarked data.

read the caption

Table 1: The averaged largest Q% cosine similarity of our method on different watermarks.

In-depth insights#

DOV Revisited#

A revisit of existing Dataset Ownership Verification (DOV) methods reveals a critical reliance on watermarking techniques for both the initial embedding and subsequent verification stages. This approach inherently assumes a one-time, privacy-preserving verification process, which is often unrealistic in practice. Adversaries could potentially adapt, removing the watermark or otherwise circumventing the verification process. This calls for a paradigm shift that moves beyond the limitations of current techniques. Therefore, a more robust method is needed, one that prioritizes secure verification without exposing watermarks, improving the overall security of DOV and protecting intellectual property rights.

ZeroMark Method#

The core of the ZeroMark method lies in its ability to verify dataset ownership without directly using watermarked samples, thus addressing a critical weakness in existing techniques. It leverages the intrinsic properties of DNNs trained on watermarked data, focusing on the gradients calculated at the decision boundary. By generating the closest boundary versions of benign samples and calculating their boundary gradients, ZeroMark avoids revealing the watermark itself. The cosine similarity between these gradients and the known watermark pattern serves as the basis for a hypothesis test, determining whether a suspect model was trained on the protected dataset. This approach is particularly innovative due to its black-box setting, requiring only prediction labels from the suspect model, and demonstrates robustness against potential adaptive attacks by adversaries. ZeroMark’s effectiveness lies in its clever use of boundary gradients, exploiting a subtle but crucial characteristic of watermarked models. This is a significant advancement towards secure dataset ownership verification.

Boundary Gradients#

The concept of “Boundary Gradients” in the context of this research paper appears to be a crucial innovation for dataset ownership verification. The authors seem to have discovered that gradients calculated at the decision boundary of a model trained on a watermarked dataset exhibit a unique pattern closely related to the watermark itself. This is a significant departure from existing methods which directly rely on the watermarked samples, thereby being vulnerable to attacks that reveal or remove the watermark. The use of boundary gradients, obtained without directly accessing watermarked samples, offers enhanced security and privacy. This approach provides a more robust and stealthy method for verification, as it leverages the intrinsic properties of the trained model rather than relying on explicit features of the watermark. The theoretical underpinnings of this relationship between boundary gradients and watermarks would be central to the paper’s contribution, requiring a rigorous mathematical demonstration to establish the efficacy and reliability of this novel approach. The exploration and verification of this intriguing property are what makes this ‘Boundary Gradients’ section particularly compelling and innovative.

Adaptive Attacks#

Adaptive attacks are a significant concern in the field of data security, especially concerning dataset ownership verification (DOV). These attacks involve adversaries who adjust their strategies based on the system’s response. In the context of DOV, adaptive attacks could involve adversaries attempting to identify and exploit weaknesses in the watermarking or verification methods to gain unauthorized access to the dataset. A robust DOV system needs to account for adaptive attacks and employ techniques to mitigate their effectiveness. This might involve incorporating randomness into the watermarking process, employing more sophisticated verification methods that are resistant to manipulation, or developing detection mechanisms for adaptive attack patterns. Understanding the different types of adaptive attacks that could be launched is crucial for building effective defenses. The success of an adaptive attack depends largely on the adversary’s capabilities and the sophistication of the DOV system employed. Research into adaptive attacks helps researchers develop stronger, more resilient DOV systems and to stay ahead of sophisticated attackers who seek to exploit the vulnerabilities of such systems. The development of defensive strategies against adaptive attacks is a continuous process of refinement and improvement, driven by the constant evolution of attack methods.

Future of DOV#

The future of Dataset Ownership Verification (DOV) hinges on addressing its current limitations. Moving beyond one-time verification is crucial; current methods often rely on revealing watermarks, leaving datasets vulnerable to subsequent attacks. Developing more robust watermarking techniques resistant to removal or adaptation is essential. This includes exploring methods that subtly alter the statistical properties of trained models without relying on easily detectable patterns. Exploring alternative verification methods that don’t directly rely on watermarked samples is also key. Techniques like analyzing model behavior on boundary samples, as seen in ZeroMark, demonstrate promising avenues. Enhanced security is paramount; future DOV should incorporate cryptographic techniques and potentially leverage blockchain technology for tamper-proof record-keeping. Finally, considering broader societal impacts is vital. As DOV matures, it must address fairness concerns and prevent misuse for discriminatory purposes. The ultimate goal is creating a system that effectively protects dataset ownership without hindering accessibility or innovation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

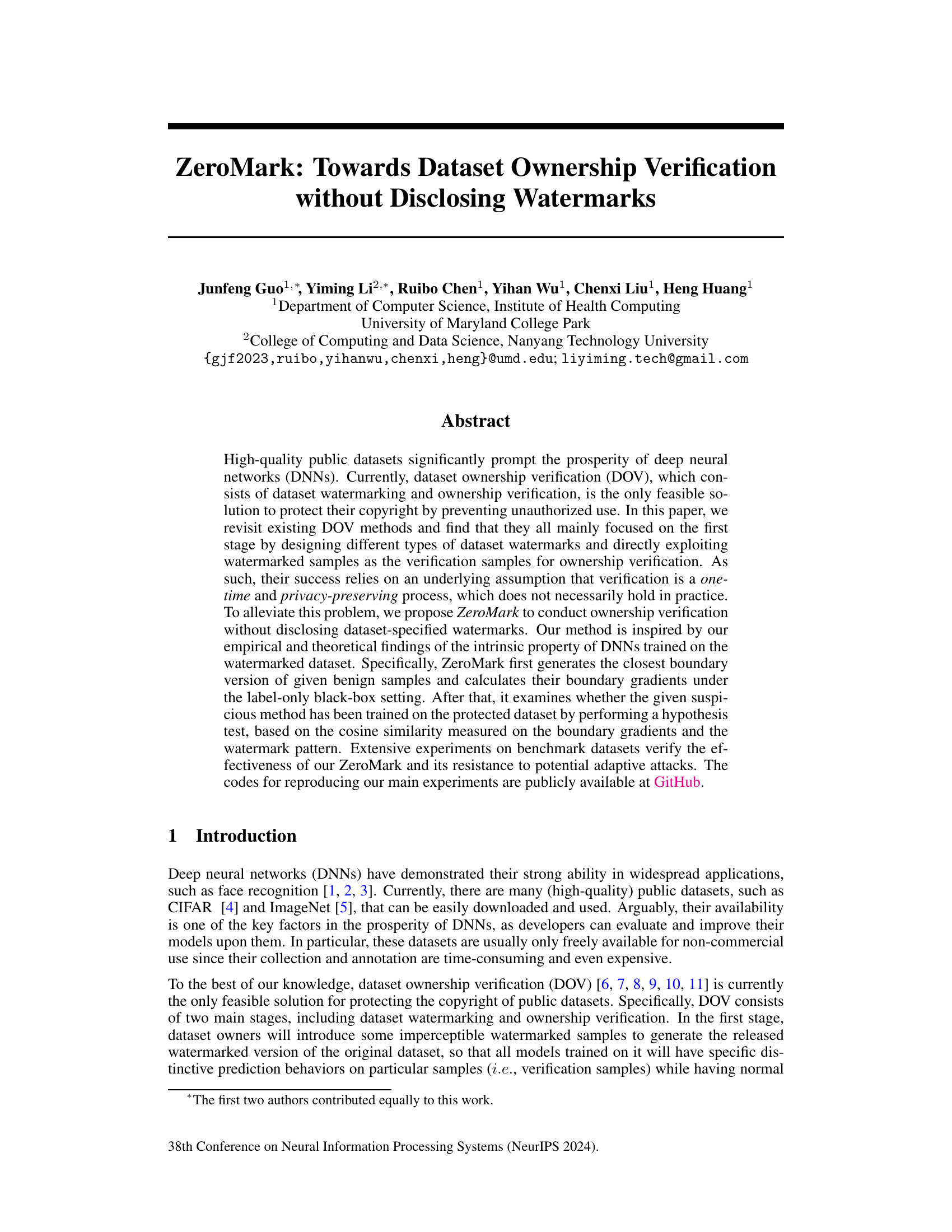

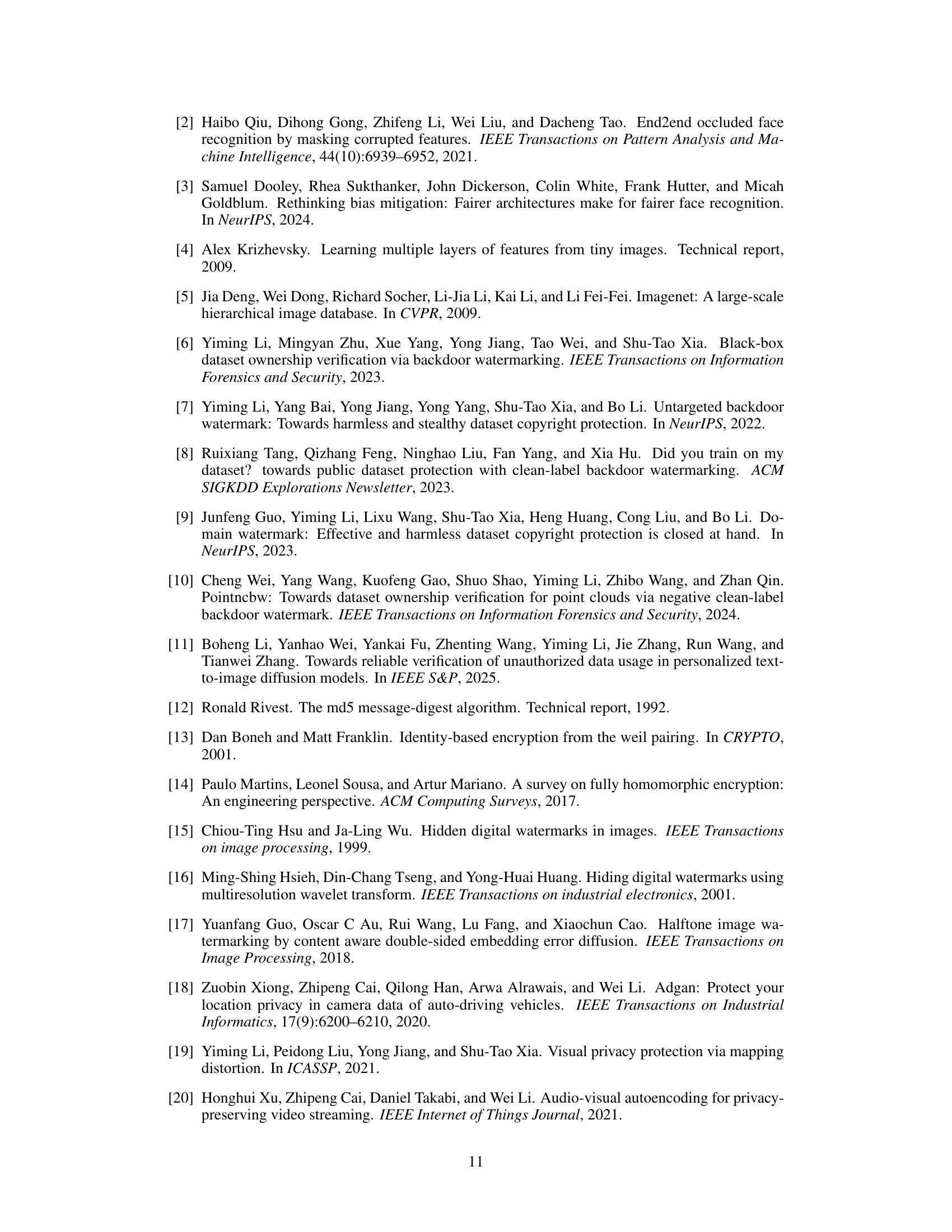

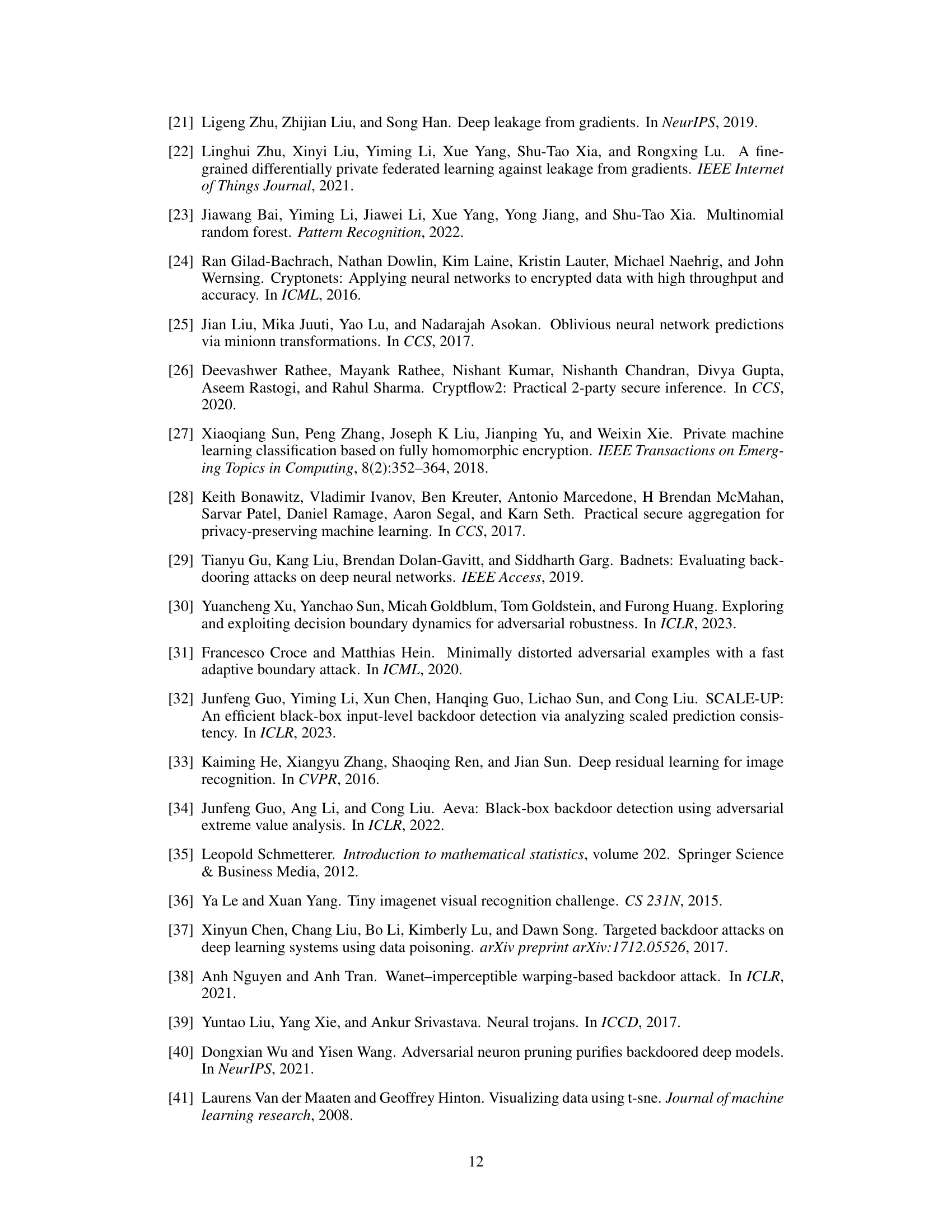

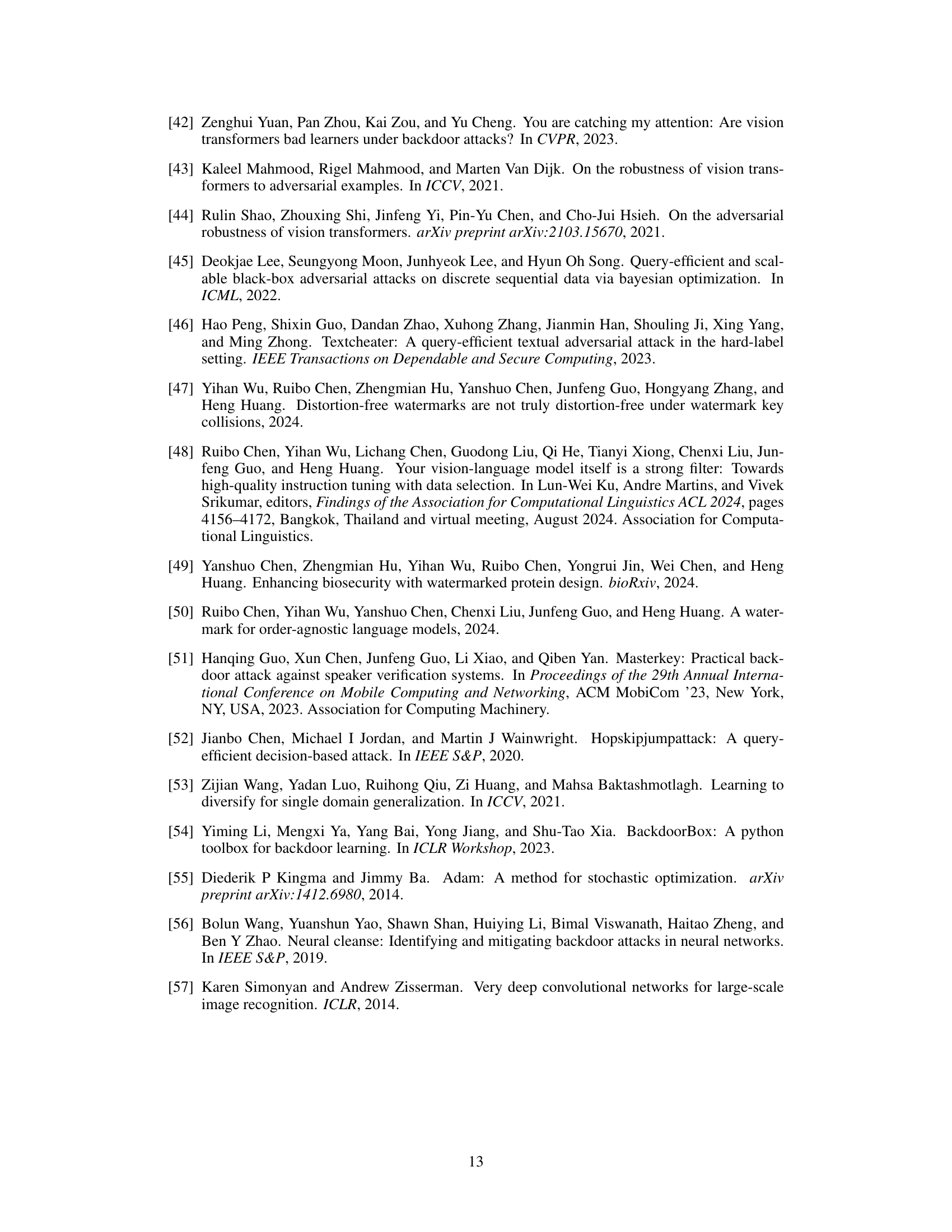

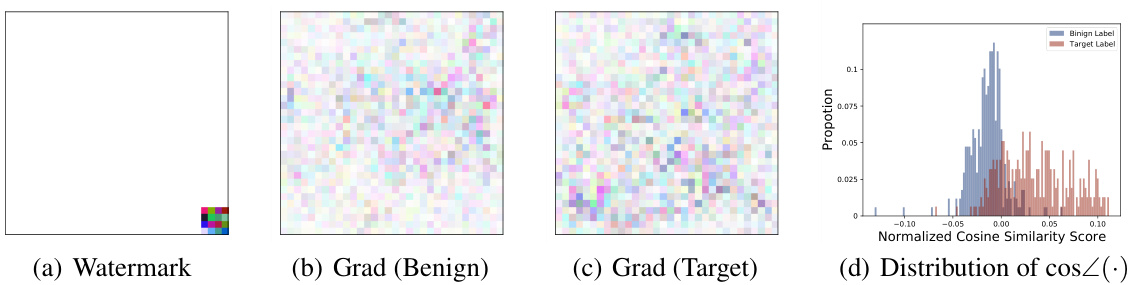

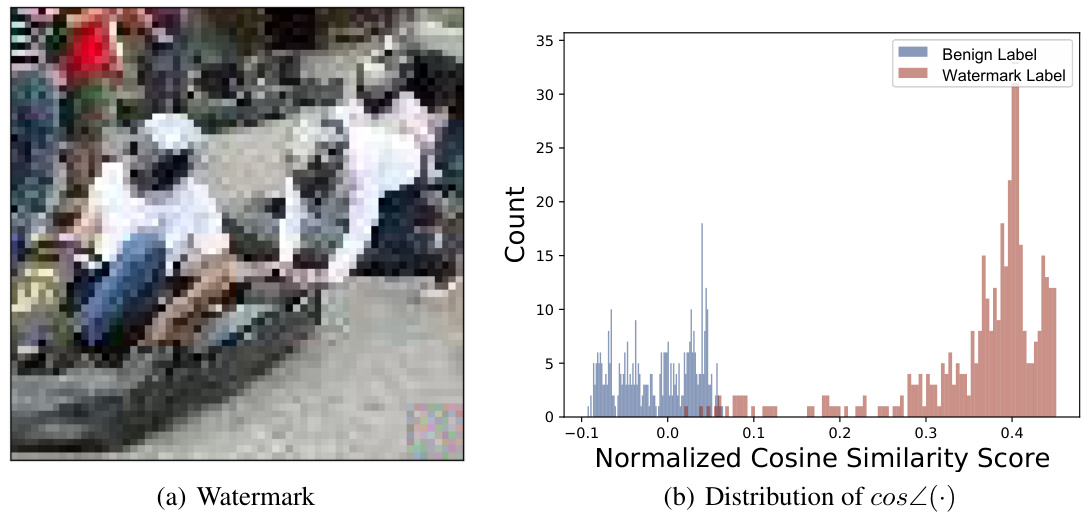

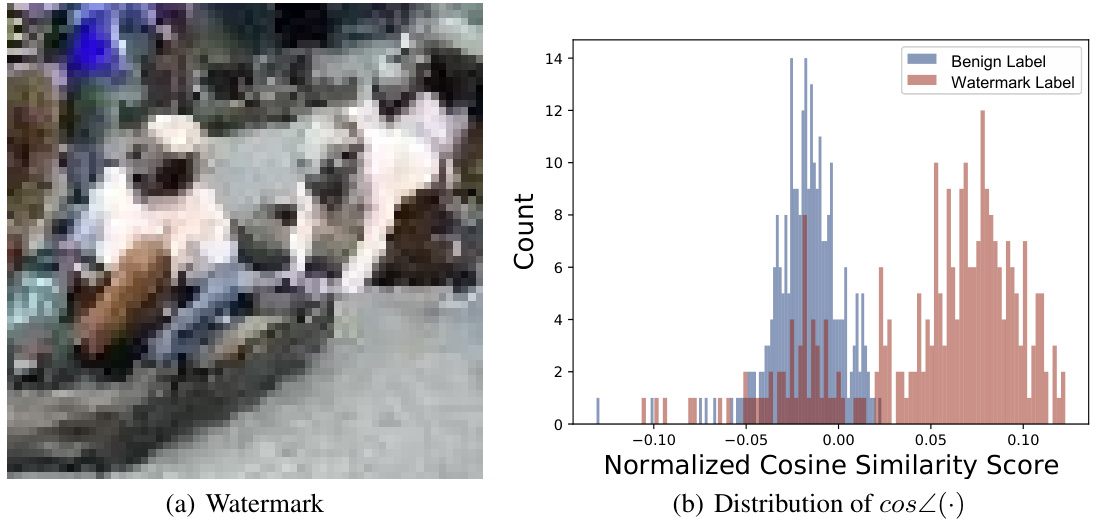

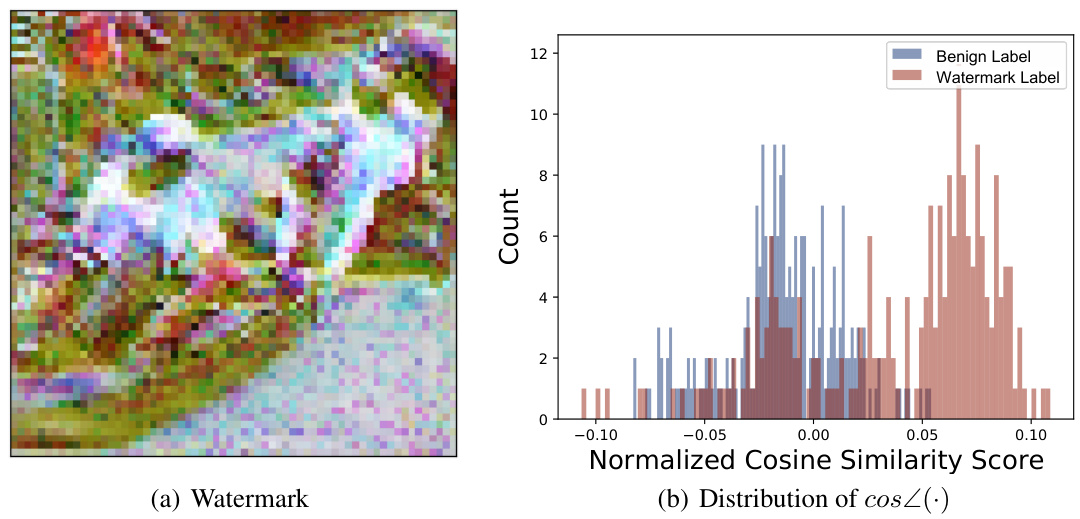

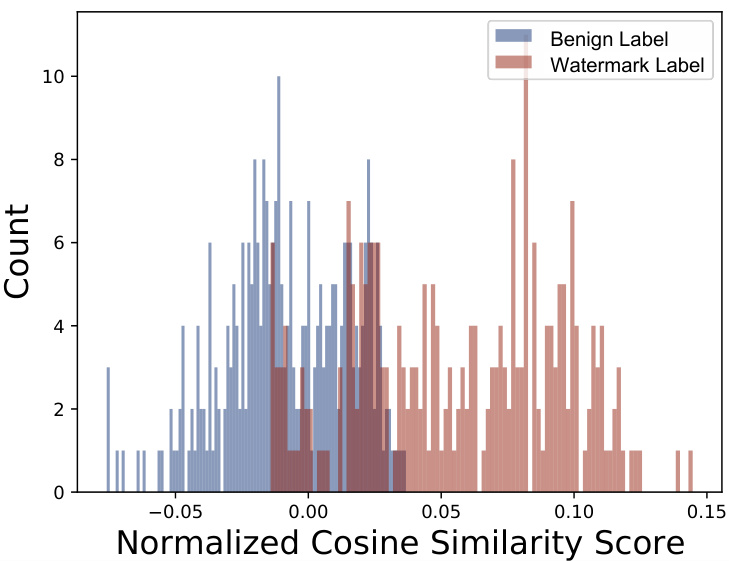

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of an empirical study on the relationship between watermark patterns and boundary gradients in a watermarked DNN. Panel (a) displays the watermark pattern used. Panels (b) and (c) showcase example boundary gradients calculated for benign and target labels, respectively. Finally, panel (d) presents the distribution of cosine similarity scores between these boundary gradients and the watermark pattern, highlighting a key finding of the study.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) shows the watermark pattern for BadNets [29] used in our empirical study. (b) and (c) are examples of boundary gradients calculated under benign and target labels. (d) shows the distribution for the cosine similarity calculated over boundary gradients for benign and target labels. More empirical studies on other types of watermarks are included in the appendix.

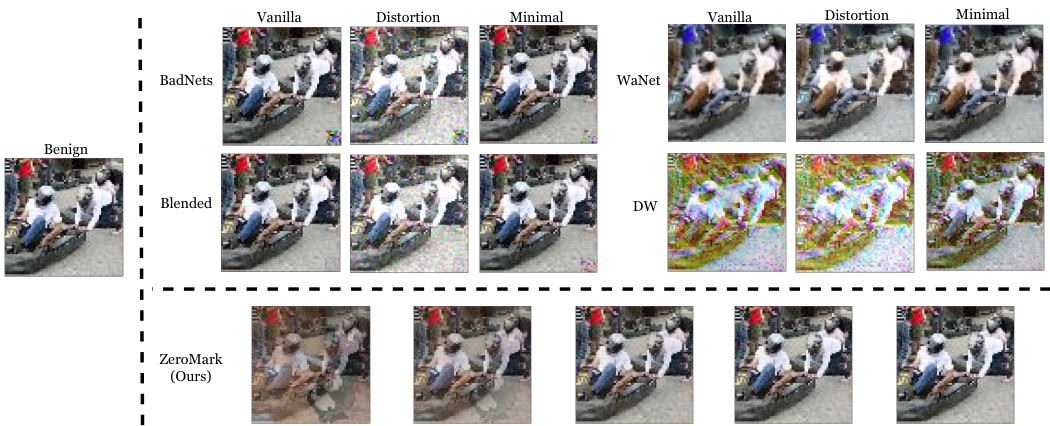

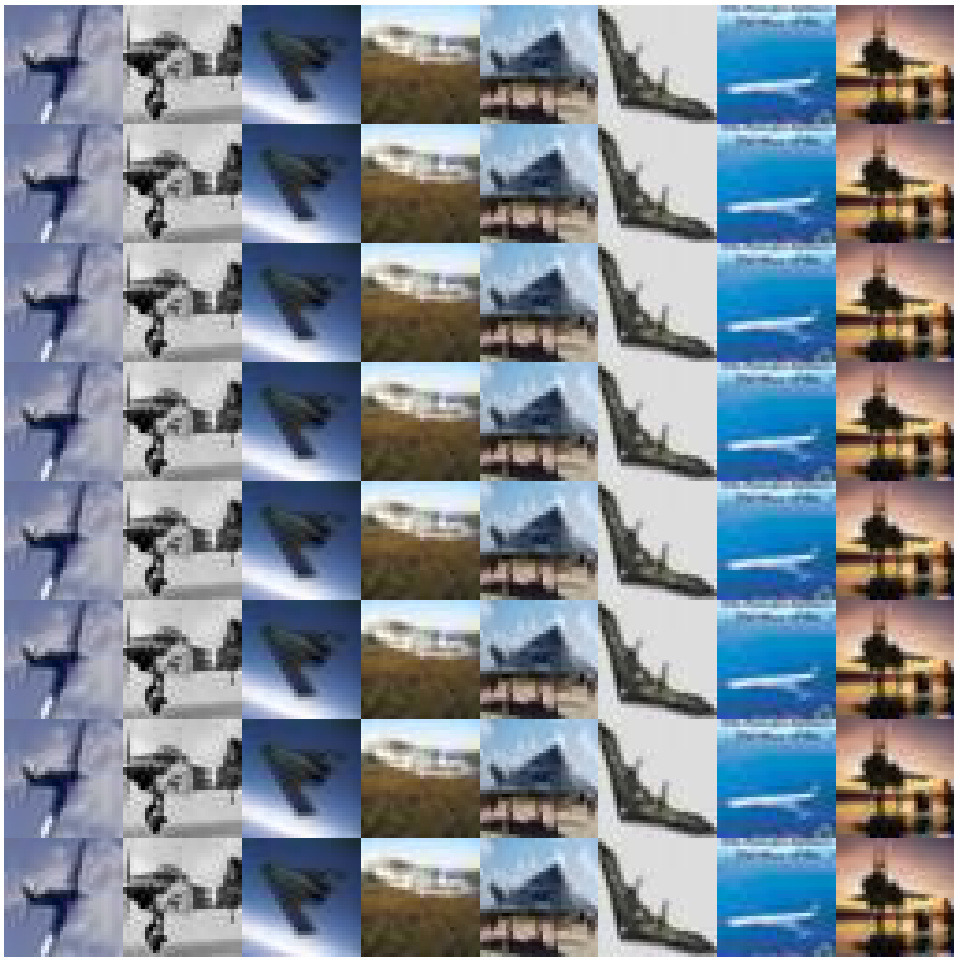

🔼 This figure shows example verification samples generated by different watermarking methods (BadNets, Blended, WaNet, and DW) and verification methods (Vanilla, Minimal, and Distortion). It visually demonstrates how each method affects the appearance of verification samples on the Tiny-ImageNet dataset. The figure highlights the differences between original benign samples and the variations introduced by each watermarking and verification technique.

read the caption

Figure 4: The example of verification samples across different watermarks (i.e., BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) and verification methods (i.e., Vanilla, Minimal, Distortion) on Tiny-ImageNet.

🔼 This figure compares existing Dataset Ownership Verification (DOV) methods with the proposed ZeroMark method. Existing DOV methods use watermarked samples in the verification stage, which makes them vulnerable if the watermark is compromised. ZeroMark addresses this by using boundary samples instead, which do not contain dataset-specific watermarks and thus increase the security of the verification process.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of existing dataset ownership verification (DOV) methods and our ZeroMark. In the verification phase, existing DOV approaches directly exploit watermarked samples for verification purposes. In contrast, ZeroMark queries the suspicious model with boundary samples without disclosing dataset-specified watermarks to safeguard the verification process.

🔼 This figure presents an empirical study on the properties of boundary gradients in watermarked DNNs. It shows (a) a BadNets watermark pattern, (b) boundary gradients calculated for benign labels, (c) boundary gradients calculated for target labels, and (d) a distribution illustrating the cosine similarity between these gradients and the watermark pattern. The distribution shows a significant difference in cosine similarity between the benign and target labels, highlighting that boundary gradients calculated on the target label are more similar to the watermark pattern.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) shows the watermark pattern for BadNets [29] used in our empirical study. (b) and (c) are examples of boundary gradients calculated under benign and target labels. (d) shows the distribution for the cosine similarity calculated over boundary gradients for benign and target labels.

🔼 This figure shows the watermark pattern used in the empirical study and the distribution of cosine similarity between watermark patterns and boundary gradients of the closest boundary samples. Panels (b) and (c) show example boundary gradients for benign and target labels, illustrating that the distribution of cosine similarity is different (has larger values) for target labels compared to benign labels.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) shows the watermark pattern for BadNets [29] used in our empirical study. (b) and (c) are examples of boundary gradients calculated under benign and target labels. (d) shows the distribution for the cosine similarity calculated over boundary gradients for benign and target labels.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the empirical results supporting Theorem 1, which states that the cosine similarity between watermark patterns and boundary gradients increases as the boundary sample is updated. Subfigure (a) shows the watermark pattern itself. (b) and (c) illustrate example boundary gradients calculated for benign and target labels, respectively, highlighting their differing patterns. Finally, (d) presents a distribution of the cosine similarity scores, visually showing that higher cosine similarity scores are obtained for target labels.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) shows the watermark pattern for BadNets [29] used in our empirical study. (b) and (c) are examples of boundary gradients calculated under benign and target labels. (d) shows the distribution for the cosine similarity calculated over boundary gradients for benign and target labels.

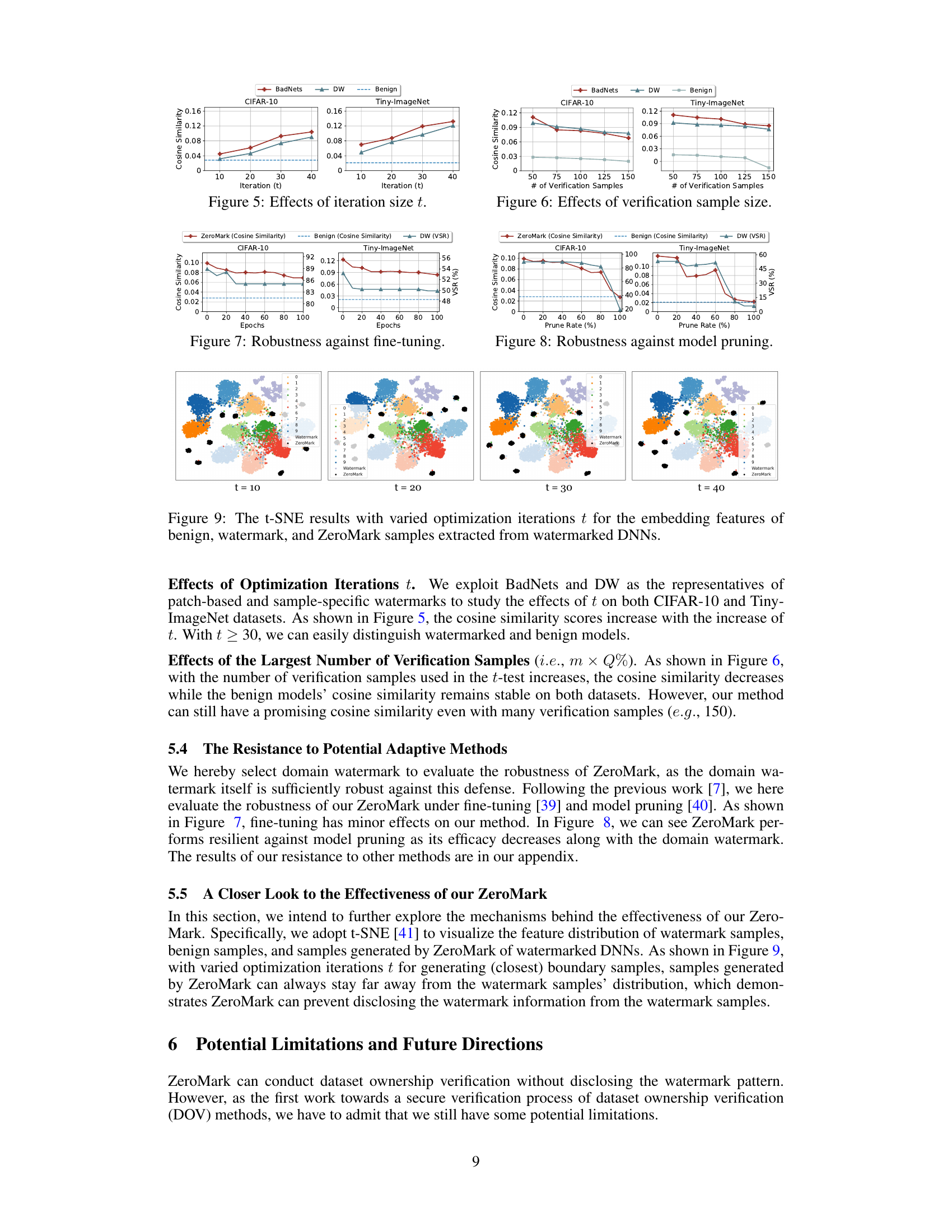

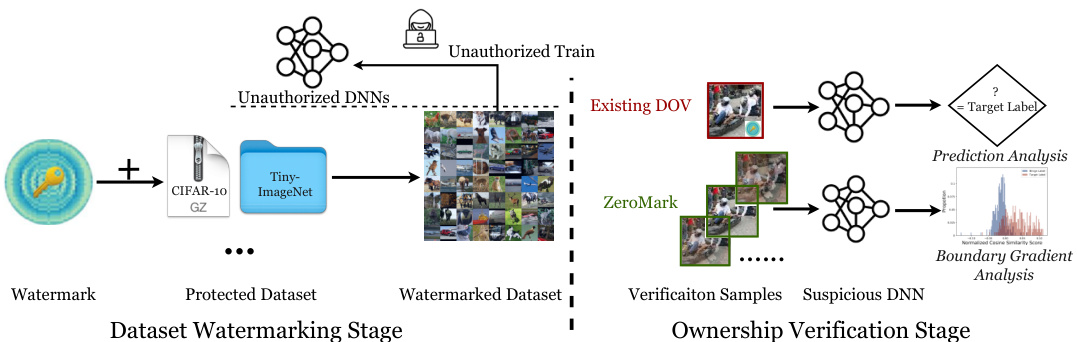

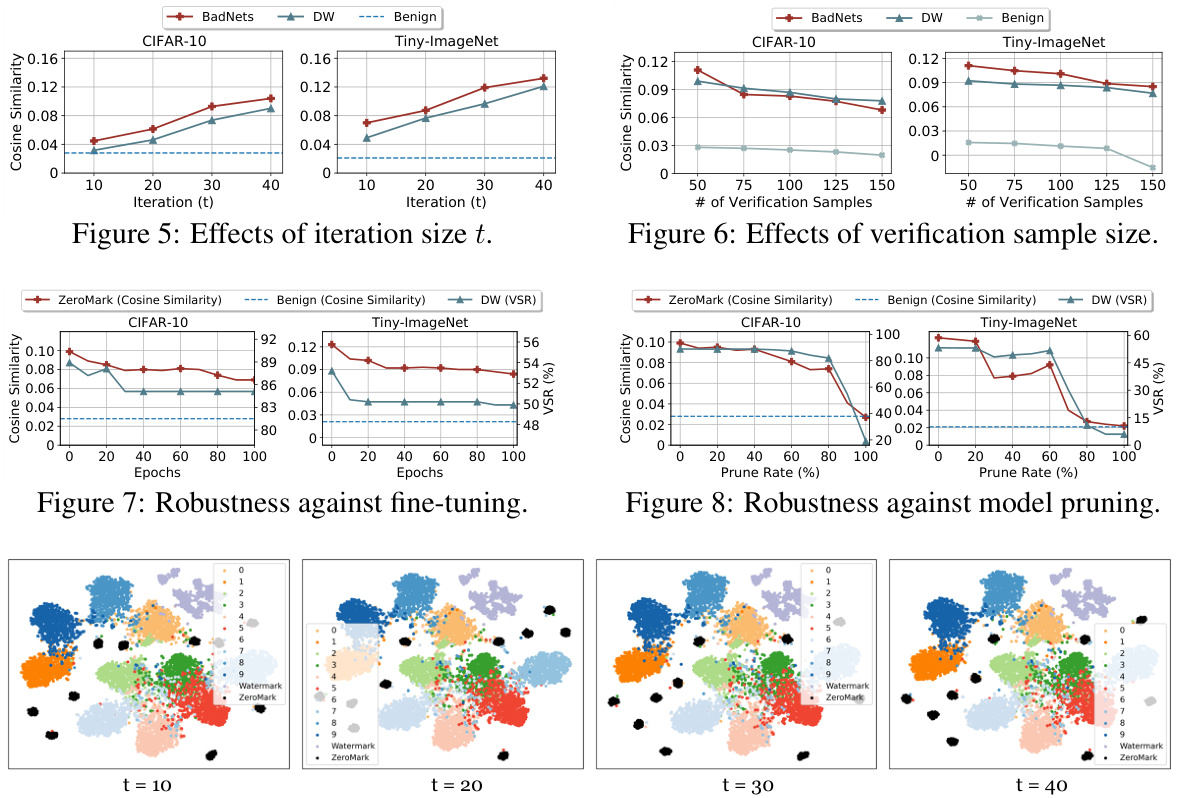

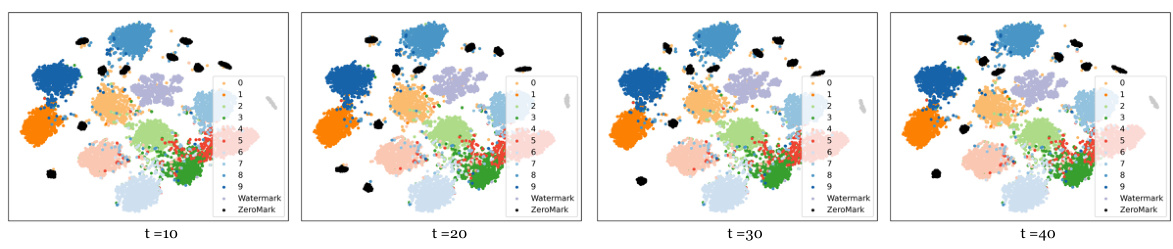

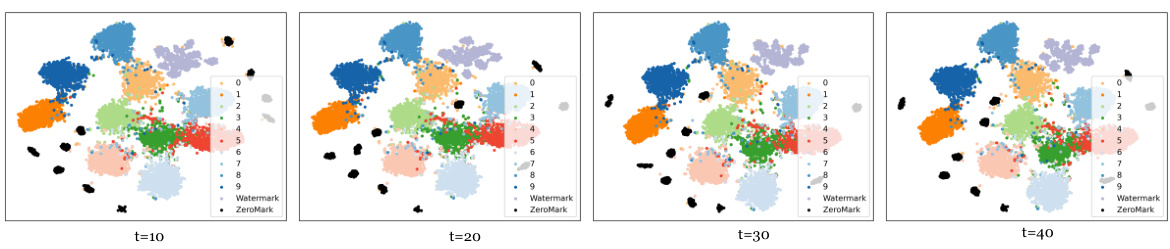

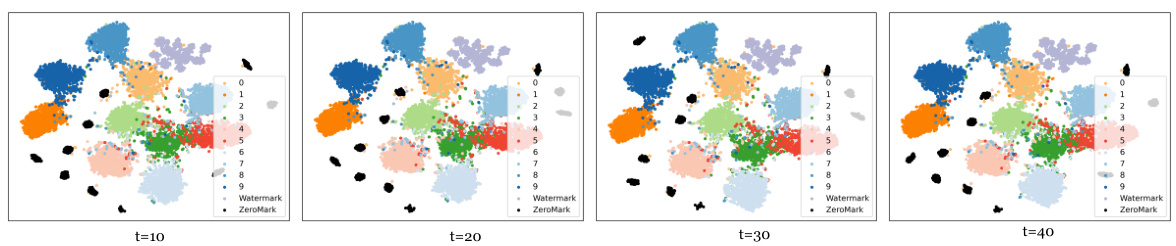

🔼 This figure shows the results of t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) applied to the embedding features extracted from watermarked deep neural networks (DNNs). Four different optimization iteration counts (t=10, 20, 30, 40) are shown, each with visualizations of benign samples, watermarked samples, and samples generated by the ZeroMark method. The t-SNE plots illustrate how the feature representations of ZeroMark-generated samples differ from those of both benign and watermarked samples across different optimization levels, supporting the algorithm’s ability to distinguish between them without revealing watermark information.

read the caption

Figure 9: The t-SNE results with varied optimization iterations t for the embedding features of benign, watermark, and ZeroMark samples extracted from watermarked DNNs.

🔼 This figure visualizes the embedding features of benign samples, watermarked samples, and samples generated by ZeroMark using t-SNE. It shows how the features cluster together with varying optimization iteration steps (t=10, 20, 30, 40). The goal is to demonstrate that ZeroMark generates samples whose features are distinct from the watermarked samples, thus protecting the watermark.

read the caption

Figure 9: The t-SNE results with varied optimization iterations t for the embedding features of benign, watermark, and ZeroMark samples extracted from watermarked DNNs.

🔼 This figure visualizes the embedding features of benign samples, watermarked samples, and samples generated by the ZeroMark method using t-SNE. The visualization shows how the different sample types cluster in the feature space for different numbers of optimization iterations (t). It demonstrates that ZeroMark samples are distinctly separated from the watermarked samples, indicating that ZeroMark effectively avoids revealing watermark information.

read the caption

Figure 9: The t-SNE results with varied optimization iterations t for the embedding features of benign, watermark, and ZeroMark samples extracted from watermarked DNNs.

🔼 This figure shows the watermark pattern used and examples of boundary gradients calculated for benign and target labels. The distribution of cosine similarity between the watermark pattern and the boundary gradients is also shown. This illustrates the key finding that boundary gradients for the target label (watermarked samples) show significantly higher cosine similarity with the watermark pattern than those for benign labels.

read the caption

Figure 2: (a) shows the watermark pattern for BadNets [29] used in our empirical study. (b) and (c) are examples of boundary gradients calculated under benign and target labels. (d) shows the distribution for the cosine similarity calculated over boundary gradients for benign and target labels.

🔼 This figure compares the existing Dataset Ownership Verification (DOV) methods with the proposed ZeroMark method. Existing methods directly use watermarked samples for verification, potentially revealing the watermark and making the system vulnerable. In contrast, ZeroMark uses boundary samples to verify ownership without exposing the watermarks, enhancing security.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of existing dataset ownership verification (DOV) methods and our ZeroMark. In the verification phase, existing DOV approaches directly exploit watermarked samples for verification purposes. In contrast, ZeroMark queries the suspicious model with boundary samples without disclosing dataset-specified watermarks to safeguard the verification process.

🔼 This figure illustrates the difference between existing Dataset Ownership Verification (DOV) methods and the proposed ZeroMark method. Existing DOV methods use watermarked samples directly in the verification stage, making them vulnerable if the watermark pattern is leaked. ZeroMark, on the other hand, uses boundary samples, which do not contain dataset-specific watermarks, to verify ownership of a dataset more securely.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of existing dataset ownership verification (DOV) methods and our Zero-Mark. In the verification phase, existing DOV approaches directly exploit watermarked samples for verification purposes. In contrast, ZeroMark queries the suspicious model with boundary samples without disclosing dataset-specified watermarks to safeguard the verification process.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of verification samples generated using different watermarking techniques (BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) and verification methods (Vanilla, Minimal, Distortion) on the Tiny-ImageNet dataset. Each watermarking technique embeds a unique pattern into the dataset, making the models trained on the watermarked data exhibit specific behaviors on particular samples. The verification methods then try to identify if a model was trained on the watermarked data by examining its prediction behavior on these samples. The figure visually demonstrates the differences in verification samples generated by different approaches, highlighting the variations introduced by each watermarking technique and verification method.

read the caption

Figure 4: The example of verification samples across different watermarks (i.e., BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) and verification methods (i.e., Vanilla, Minimal, Distortion) on Tiny-ImageNet.

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of verification samples generated by different watermarking methods (BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) and verification approaches (Vanilla, Minimal, Distortion). Each watermarking technique embeds a unique pattern into the dataset, and the verification methods use different strategies to check if the model was trained on the watermarked dataset. The image displays example samples from each combination, visually illustrating the differences in how the watermarks and verification methods affect the generated images.

read the caption

Figure 4: The example of verification samples across different watermarks (i.e., BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) and verification methods (i.e., Vanilla, Minimal, Distortion) on Tiny-ImageNet.

🔼 This figure visually demonstrates the verification samples generated by different watermarking methods (BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) and verification approaches (Vanilla, Minimal, Distortion) on the Tiny-ImageNet dataset. Each watermarking method embeds a unique pattern into the dataset, and each verification method has a unique way of using those samples to check if a model was trained on the watermarked dataset. The image shows sample images from each combination to illustrate the differences.

read the caption

Figure 4: The example of verification samples across different watermarks (i.e., BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) and verification methods (i.e., Vanilla, Minimal, Distortion) on Tiny-ImageNet.

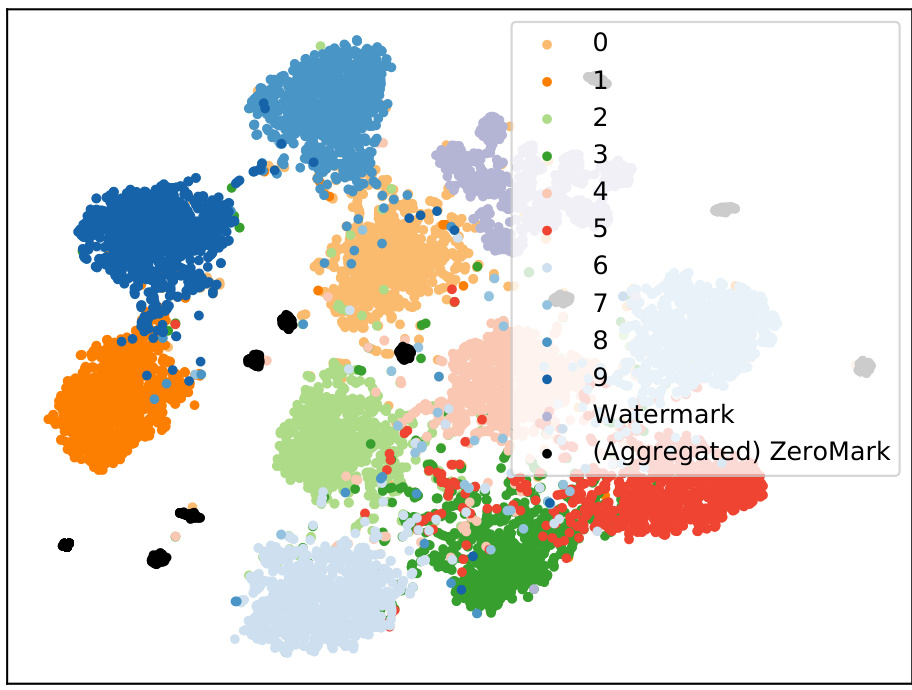

🔼 This figure shows the results of t-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) applied to aggregated boundary samples. It visually represents the separation between watermark samples and those generated by ZeroMark. The goal is to demonstrate that the aggregated boundary samples, even after an attempt to recover the watermark pattern, are distinct from the actual watermark samples, thus supporting the effectiveness of the ZeroMark method. The black points represent the (Aggregated) ZeroMark samples, while the colored points represent the watermark samples from different classes.

read the caption

Figure 22: The t-SNE clustering results for aggregated boundary samples.

More on tables

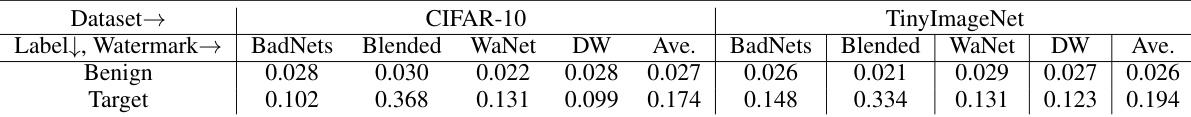

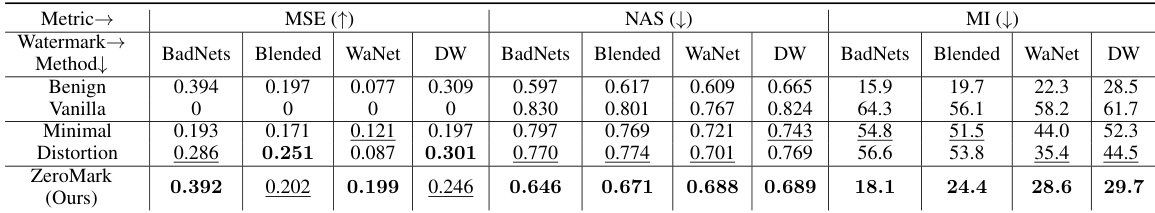

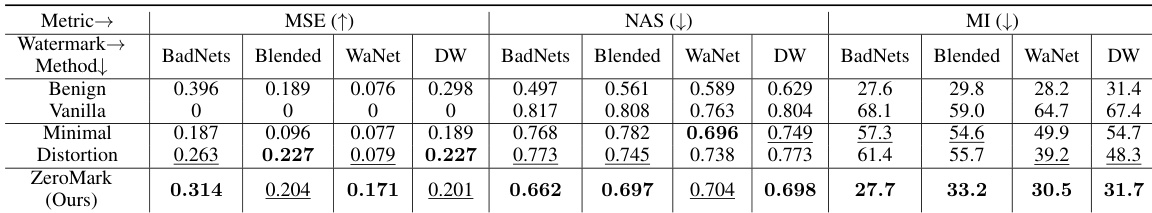

🔼 This table presents the performance evaluation of different methods on the CIFAR-10 dataset using three metrics: MSE (Mean Squared Error), NAS (Neuron Activation Similarity), and MI (Mutual Information). The methods compared include Vanilla (using original watermarked samples), Minimal (using minimally distorted watermarks), Distortion (using distorted watermarks), and ZeroMark (the proposed method). The results are shown for four different watermarking techniques (BadNets, Blended, WaNet, and DW). Lower MSE and MI values, and higher NAS values indicate better performance in protecting watermark information.

read the caption

Table 2: The performance on CIFAR-10. In particular, we mark the best results in bold while the value within the underline denotes the second-best results (except the benign samples).

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different methods for dataset ownership verification on the CIFAR-10 dataset using BadNets, Blended, WaNet, and DW watermarks. The metrics used for comparison are MSE (Mean Squared Error), NAS (Neuron Activation Similarity), and MI (Mutual Information). Lower MSE and MI values, and higher NAS values are better. The ‘Benign’ row shows results for benign samples (no watermark), while ‘Vanilla’ shows results using original watermarked samples. ‘Minimal’ and ‘Distortion’ represent attempts to protect the watermark by using minimal or distorted watermarks, respectively. ‘ZeroMark (Ours)’ presents the results of the proposed method.

read the caption

Table 2: The performance on CIFAR-10. In particular, we mark the best results in bold while the value within the underline denotes the second-best results (except the benign samples).

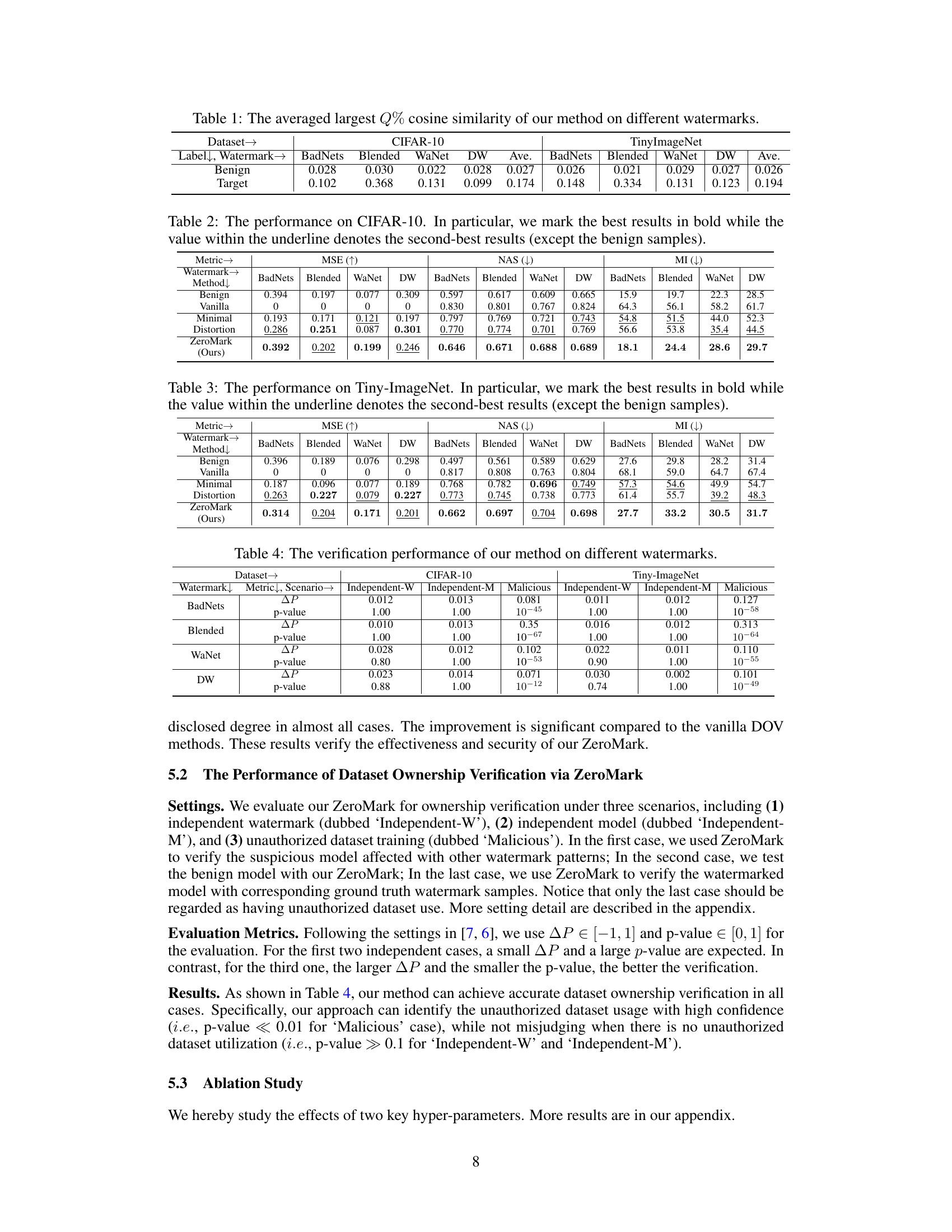

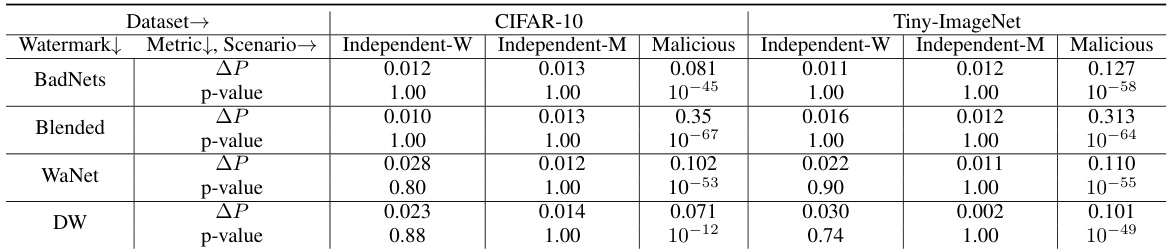

🔼 This table presents the results of the dataset ownership verification experiment using the proposed ZeroMark method. It compares the performance across four different watermarking techniques (BadNets, Blended, WaNet, DW) under three scenarios: independent watermark (Independent-W), independent model (Independent-M), and malicious usage (Malicious). For each scenario and watermark, it reports the change in the largest Q% cosine similarity (ΔP) between benign and watermarked samples and the p-value from a t-test. The p-value indicates whether the hypothesis that the suspicious model was trained on the watermarked dataset is rejected; very low p-values in the Malicious scenarios (e.g., 10^-45) suggest successful identification of malicious usage.

read the caption

Table 4: The verification performance of our method on different watermarks.

Full paper#