TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) often generate factually incorrect information (hallucinations) and suffer from the “reversal curse,” where their ability to recall information is highly sensitive to the presentation order. This paper introduces the concept of the “factorization curse” to explain these issues: LLMs fail to learn the same underlying data distribution when presented with different factorizations. The authors propose a novel training approach (factorization-agnostic objectives) that allows the model to learn equally well across all possible input orderings. This strategy proves highly effective in mitigating the reversal curse across several experiments, significantly improving information retrieval accuracy.

The research uses controlled experiments with increasing levels of complexity and realism (including a WikiReversal task), demonstrating that the factorization curse is an inherent limitation of the next-token prediction objective used in many LLMs. They show that simply increasing model size, reversing training sequences, or using naive bidirectional attention is insufficient to resolve this issue. Their proposed factorization-agnostic objectives represent a promising path towards more robust knowledge storage and planning capabilities within LLMs, indicating potential benefits for applications beyond basic information retrieval.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working with large language models because it identifies a fundamental limitation (“factorization curse”) hindering reliable knowledge retrieval. It proposes innovative factorization-agnostic training strategies to mitigate this issue, potentially advancing the field towards more robust and reliable models. The findings open new avenues for research into improved knowledge storage and planning capabilities in LLMs, impacting various downstream applications.

Visual Insights#

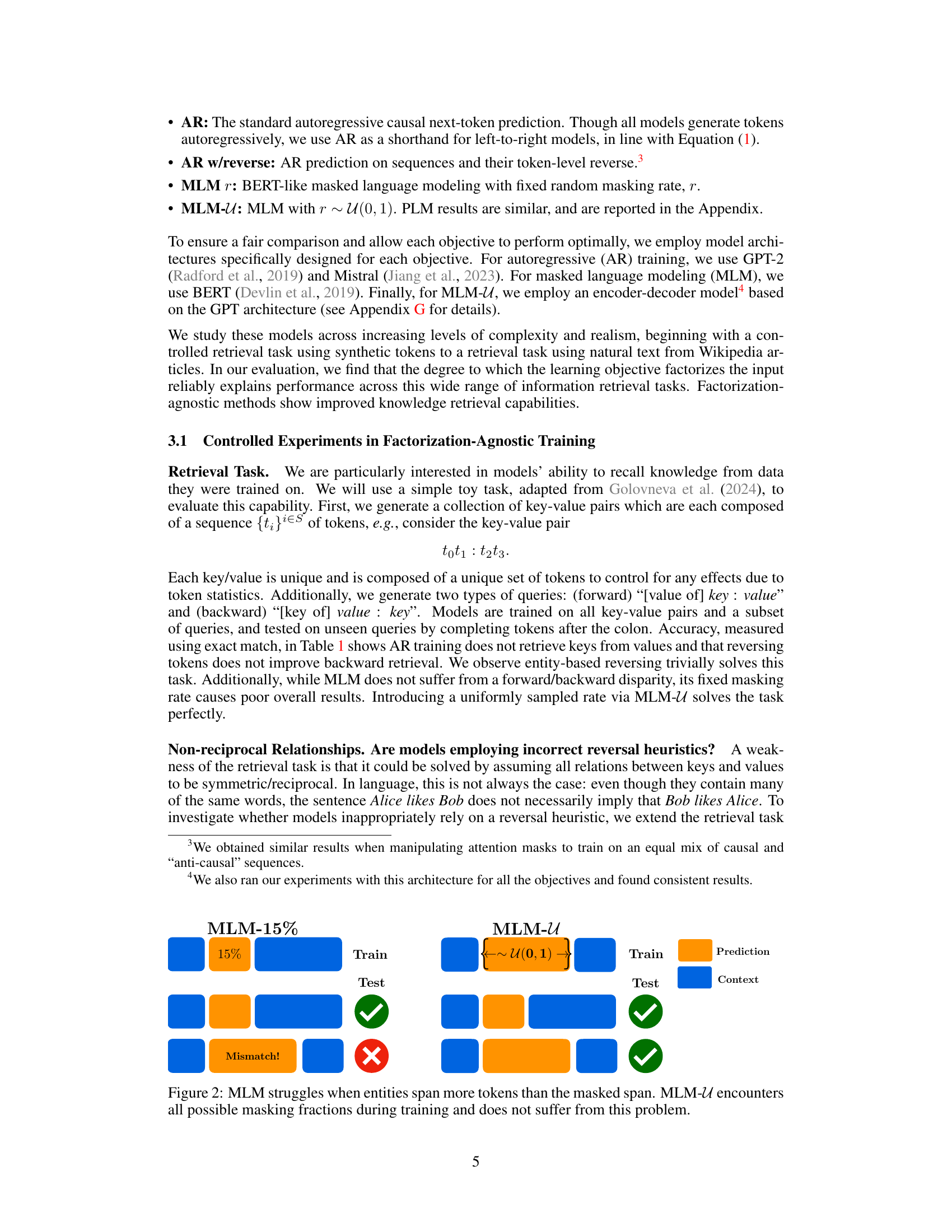

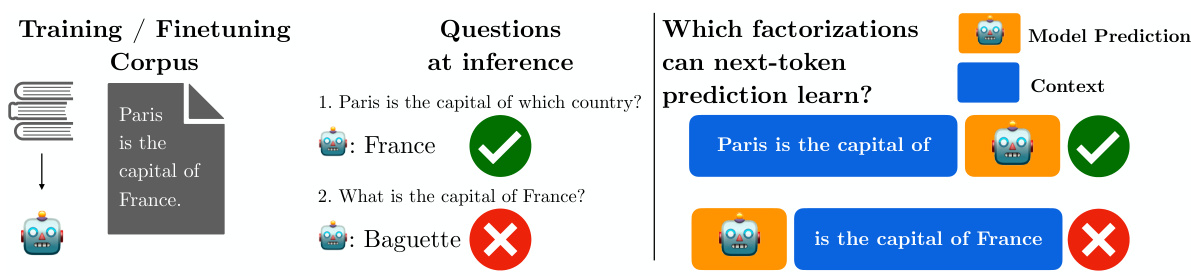

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of the reversal curse and how it relates to the factorization curse. On the left, it shows how training a model on sentences where ‘Paris’ always precedes ‘France’ leads to the model’s inability to answer a question about France’s capital when phrased differently. On the right, a visual representation clarifies how the left-to-right training objective prevents the model from learning to predict earlier tokens based on later tokens, even if the semantic meaning remains the same. This highlights how models become overly reliant on a particular sequence of tokens and fail to generalize to different factorizations of the information.

read the caption

Figure 1: (Left) Reversal curse from training a model on sentences with Paris before France. (Right) Left-to-right objective does not learn how to predict early tokens from later ones even if the information content is the same. The model overfits to a specific factorization of the joint distribution over tokens, and is unable to answer questions that require reasoning about a different factorization.

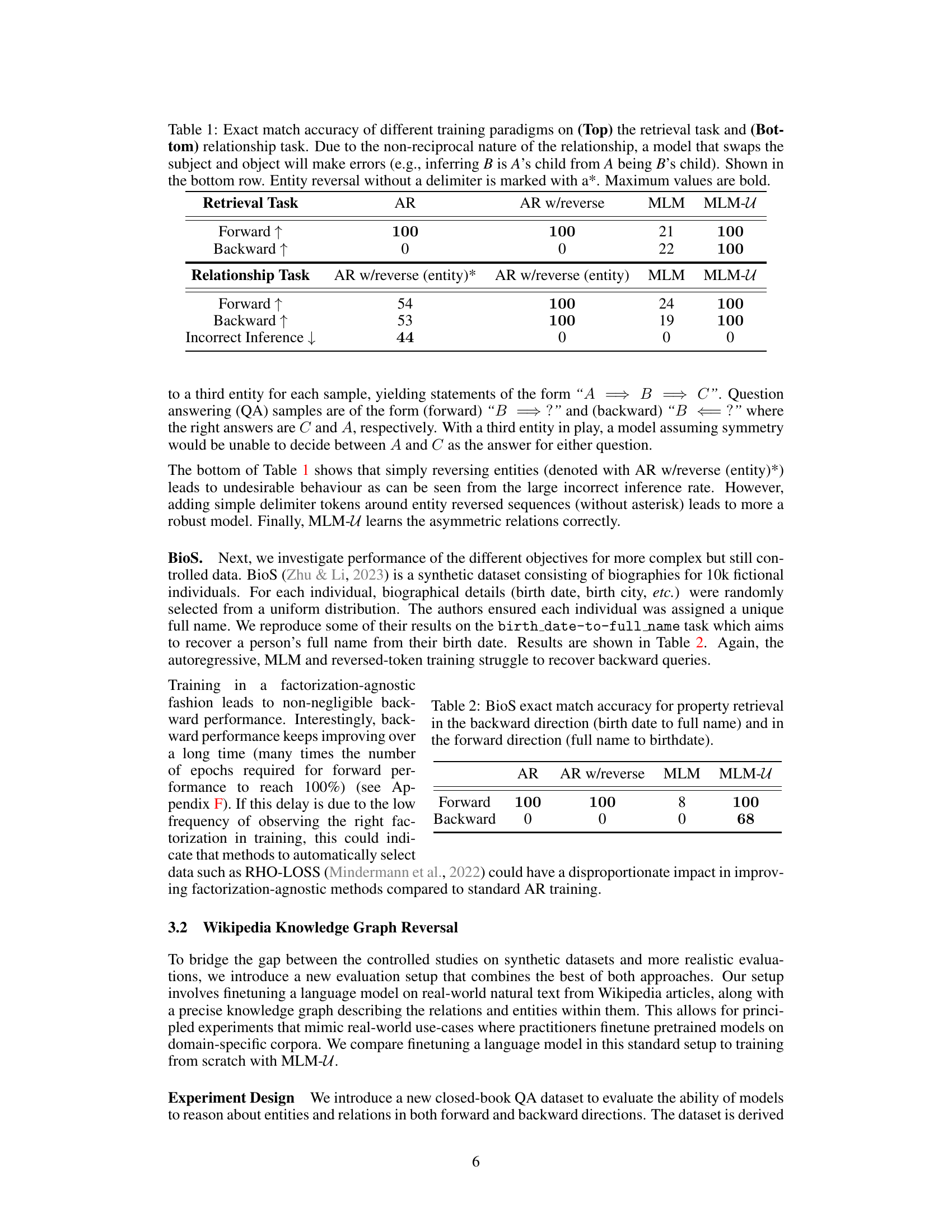

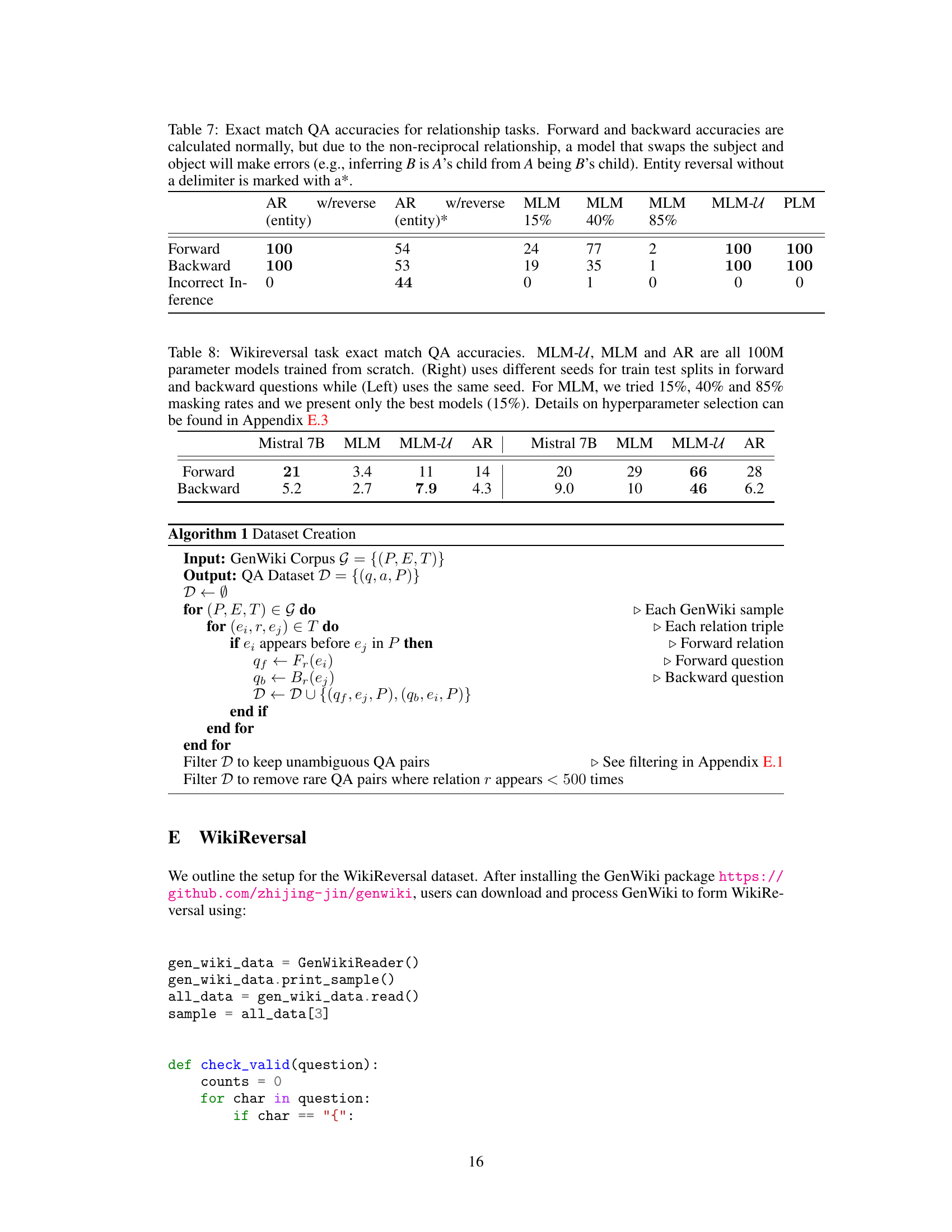

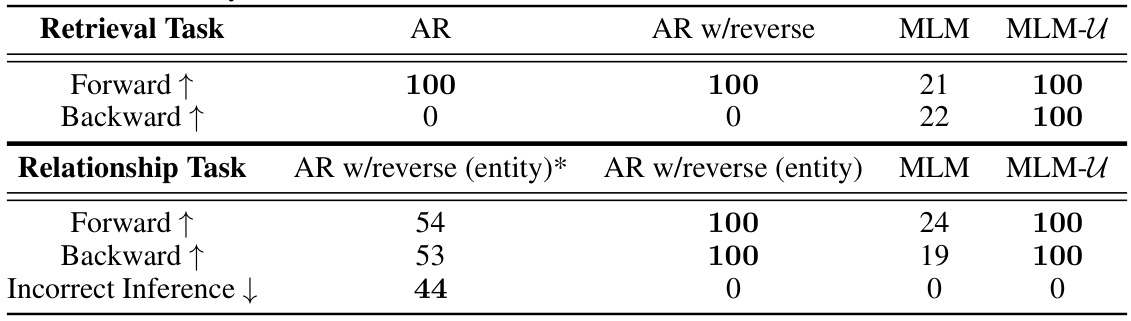

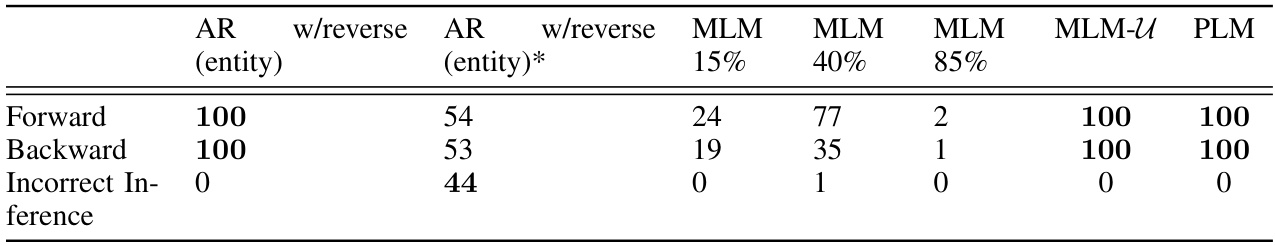

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments comparing different training methods (AR, AR with reversed sequences, MLM, and MLM-U) on two tasks: a simple retrieval task and a more complex relationship task. The retrieval task involves retrieving a key given a value or vice versa. The relationship task involves understanding asymmetric relationships between entities. The table shows that MLM-U, a factorization-agnostic method, significantly outperforms other methods on both tasks, especially in cases involving backward retrieval or understanding asymmetric relationships.

read the caption

Table 1: Exact match accuracy of different training paradigms on (Top) the retrieval task and (Bottom) relationship task. Due to the non-reciprocal nature of the relationship, a model that swaps the subject and object will make errors (e.g., inferring B is A's child from A being B's child). Shown in the bottom row. Entity reversal without a delimiter is marked with a*. Maximum values are bold.

In-depth insights#

Factorization Curse#

The “Factorization Curse” concept, as presented in the research paper, offers a novel perspective on the limitations of current large language models (LLMs). It argues that the prevalent left-to-right autoregressive training paradigm, while effective for text generation, hinders the models’ ability to retrieve and reason about information when presented in a different order or factorization. The core of the curse lies in the model’s overfitting to a specific ordering of tokens, failing to generalize to other equivalent representations of the same underlying knowledge. This is crucial because information retrieval and reasoning often necessitate the manipulation of data in ways that differ from the training sequences, highlighting a significant gap in the capabilities of current LLMs. The researchers propose that factorization-agnostic training objectives could mitigate this issue, enabling better knowledge storage and planning capabilities. This suggests a crucial shift away from simply modeling sequential patterns towards a deeper, more robust understanding of the underlying semantic structure, which is a critical challenge for the ongoing development of LLMs.

WikiReversal Task#

The WikiReversal task, as described in the research paper, presents a novel and realistic evaluation benchmark for assessing language models’ ability to handle information retrieval in scenarios requiring both forward and backward reasoning. It leverages real-world Wikipedia articles combined with their associated knowledge graph, introducing a level of complexity not found in purely synthetic datasets. This approach addresses limitations of prior benchmarks that may rely on overly simplistic relationships between entities and fail to capture the nuances of real-world knowledge. The task directly evaluates the model’s capacity to answer questions posed in both directions, thus challenging the model’s ability to retrieve information regardless of the order it was initially encountered during training. Unlike many benchmarks that focus on single relations or short sequences, WikiReversal tests the model’s ability to handle more complex relationships extracted from multi-sentence passages, making it a robust and informative evaluation. The results from this task highlight the challenges of existing language models in handling reversed or bidirectional information retrieval, emphasizing the need for new training methodologies and model architectures.

Agnostic Training#

The concept of “agnostic training” in the context of large language models (LLMs) centers on designing training methodologies that are less sensitive to the specific ordering or factorization of input data. Traditional autoregressive models heavily rely on sequential information, leading to issues like the “reversal curse.” Agnostic training aims to overcome this by enabling the model to learn underlying relationships and knowledge regardless of input arrangement. This is achieved through techniques that promote factorization-invariant learning, allowing the model to generalize better and retrieve information effectively regardless of how the data is presented. Key benefits include improved robustness and knowledge storage, but the approach often presents significant computational challenges and potentially slower convergence rates during training. Finding the optimal balance between computational efficiency and improved generalization capabilities remains a crucial challenge. Furthermore, agnostic training could lead to advancements in reasoning and planning, areas where traditional LLMs struggle.

Planning & AR#

The interplay between planning and autoregressive (AR) models is a critical area in AI research. AR models, known for their impressive text generation capabilities, often struggle with complex planning tasks. This limitation stems from their inherent sequential nature; AR models predict the next token based solely on the preceding sequence, limiting their ability to consider long-term goals or explore alternative paths. A key challenge is overcoming the “Clever Hans” effect, where models exploit superficial cues in the training data rather than developing genuine planning abilities. Researchers are exploring various approaches, including modifying training objectives to encourage more holistic planning, but it remains a significant area for further investigation and development. Factorization-agnostic objectives show promise in mitigating the inherent limitations of AR models. These methods focus on learning the underlying joint distribution of tokens rather than relying on a specific sequential order. This allows for more robust knowledge retrieval and potentially enhanced planning capabilities. Further research should explore different training paradigms, such as incorporating reinforcement learning to better guide model exploration and decision-making processes.

Future Directions#

The paper’s exploration of future directions is crucial. Factorization-agnostic training is highlighted as a promising avenue for addressing the reversal curse and improving knowledge storage. This approach shows potential for enhanced planning capabilities, suggesting broader implications beyond information retrieval. Further research is needed to address the computational challenges of factorization-agnostic objectives and their scalability to larger models and datasets. Exploring alternative objectives that enable more robust handling of varying sequence lengths and entity structures will be beneficial. Investigating the relationship between factorization-agnostic training and emergent abilities such as reasoning and planning is also essential. Developing more sophisticated evaluation metrics that capture the nuances of information retrieval and planning would facilitate a better understanding of progress in this area. In addition, investigating the interactions between factorization-agnostic training and different pretraining strategies could lead to synergistic improvements. Ultimately, a deeper understanding of the relationship between learning objectives, model architecture, and emergent capabilities is critical for advancing the field of large language models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

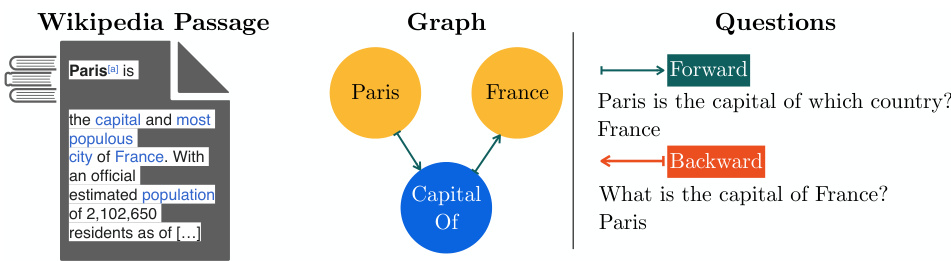

🔼 This figure illustrates the WikiReversal dataset used in the paper. It shows an example of a Wikipedia passage containing information about Paris being the capital of France, represented as a knowledge graph with nodes for ‘Paris’, ‘France’, and the relation ‘Capital Of’. Two types of questions are shown: a ‘forward’ question that follows the direction of the triple (e.g., ‘Paris is the capital of which country?’), and a ‘backward’ question that reverses this direction (e.g., ‘What is the capital of France?’). The WikiReversal dataset consists of many such passages and corresponding question-answer pairs designed to test the model’s ability to retrieve information regardless of the order it was presented during training.

read the caption

Figure 3: An example passage with a forward relation triple. The forward question queries the tail, backward queries the head. WikiReversal is a collection of passages and forward/backward QAs.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of MLM with fixed masking rates (15%, 40%, 85%) against MLM-U, a variation that uses uniformly sampled masking rates. Panel (a) shows that MLM with fixed masking rates is inconsistent, while MLM-U performs better. Panels (b) and (c) use PCA to visualize the representations learned by AR (autoregressive) and MLM-U models respectively. The visualizations reveal that MLM-U learns more structured entities than AR, suggesting improved knowledge representation.

read the caption

Figure 4: In panel (a) we compare MLM with varying masking ratios to MLM-U. In panels (b) and (c) we visualize the two main principal components of representations learned via AR versus MLM-U.

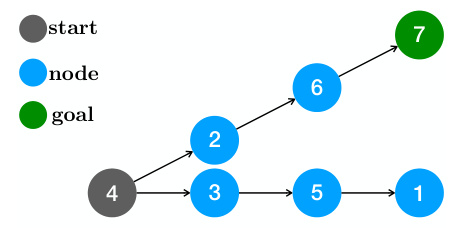

🔼 This figure illustrates a simple path-finding task used to evaluate planning capabilities of language models. The task involves predicting a sequence of nodes (2,6,7) to reach a goal node (7) starting from a start node (4). The figure highlights the ‘Clever Hans’ failure mode, where a model trained with autoregressive next-token prediction may simply predict each node based on the previously predicted node, without needing true planning abilities.

read the caption

Figure 5: Star Graph Task: Illustration and Performance Comparison. The illustration shows the 'Clever Hans' failure mode with teacher-forced AR ((Bachmann & Nagarajan, 2024) adapted).

🔼 This figure demonstrates why simply reversing the training sequences in autoregressive models (AR w/reverse) does not solve the reversal curse. The left side shows that while the model can successfully predict tokens in a reversed sequence when the entity is already provided, it fails when asked a question that necessitates reasoning about the entity in the opposite direction. The right side illustrates that true backward reasoning requires the model to be able to predict the earlier tokens based on the later context which AR models are not trained to do. It highlights a key limitation of solely relying on reversing the training order and the need for a fundamentally different approach to learn factorization-agnostic models.

read the caption

Figure 6: AR w/reverse cannot predict (left-to-right) entities that appeared on the left during training as it only learned to complete them from right to left. The two sequences in the bottom right indicate that backward retrieval is roughly equivalent to refactorizing the conditionals such that the entity of interest is predicted last conditioned on everything else. This is only approximate because answering a backward QA might require adding new tokens like 'The answer to the question is ...' but we make a weak assumption that such differences are generally irrelevant compared to the entities and relations of interest.

🔼 The figure shows the performance comparison of MLM-U and AR models on a simplified retrieval task with only two tokens. MLM-U achieves perfect accuracy (100%) in both forward and backward directions, while the AR model struggles significantly with the backward direction. This highlights the advantage of the MLM-U objective in overcoming the reversal curse and shows that it can learn to retrieve information regardless of the order in which it was presented during training.

read the caption

Figure 7: Performance of MLM-U versus AR in the two-token setting. We train both MLM-U and AR in a two-token variant of the retrieval task from from Section 3.1. We find MLM-U reaches 100% forward and backward whereas AR struggles to learn the backwards setting.

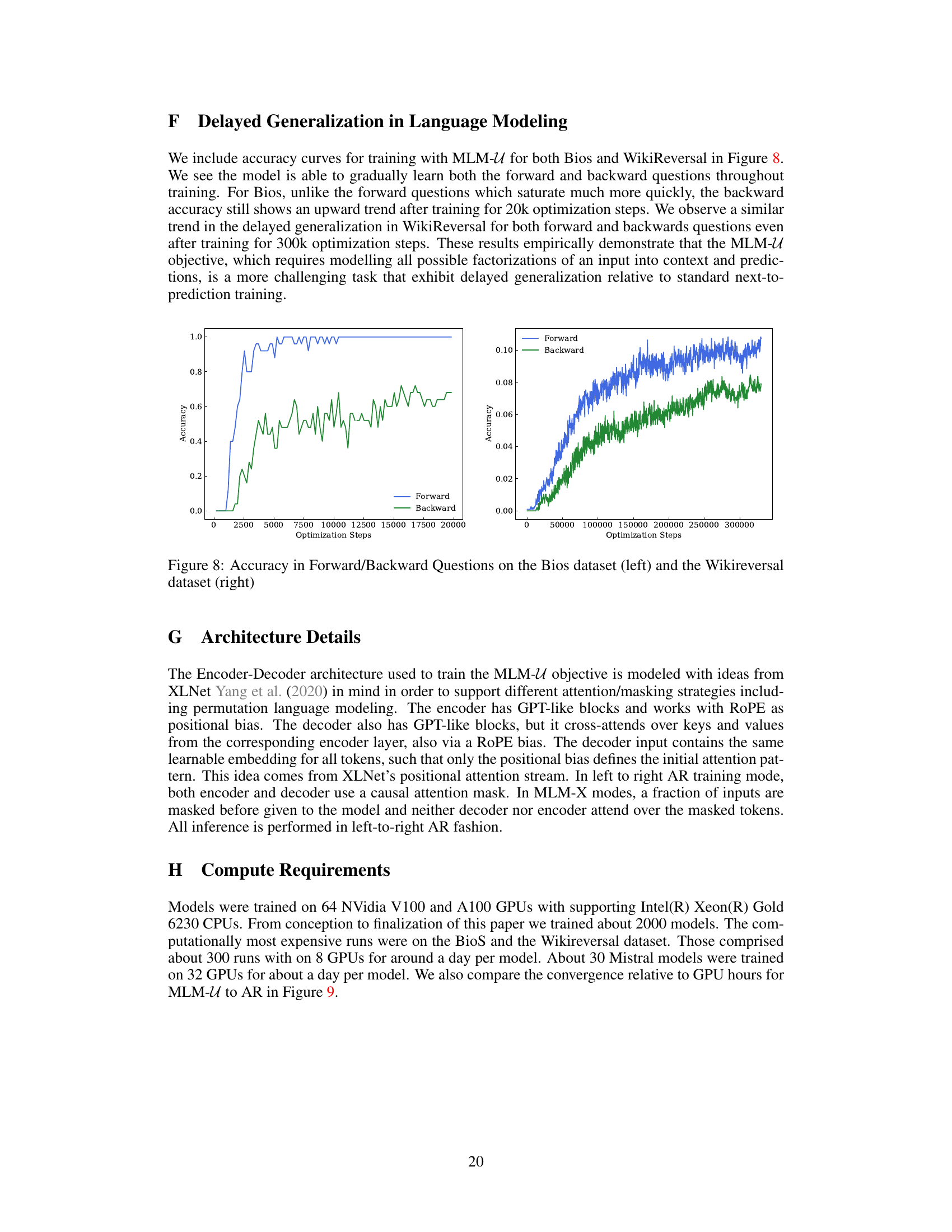

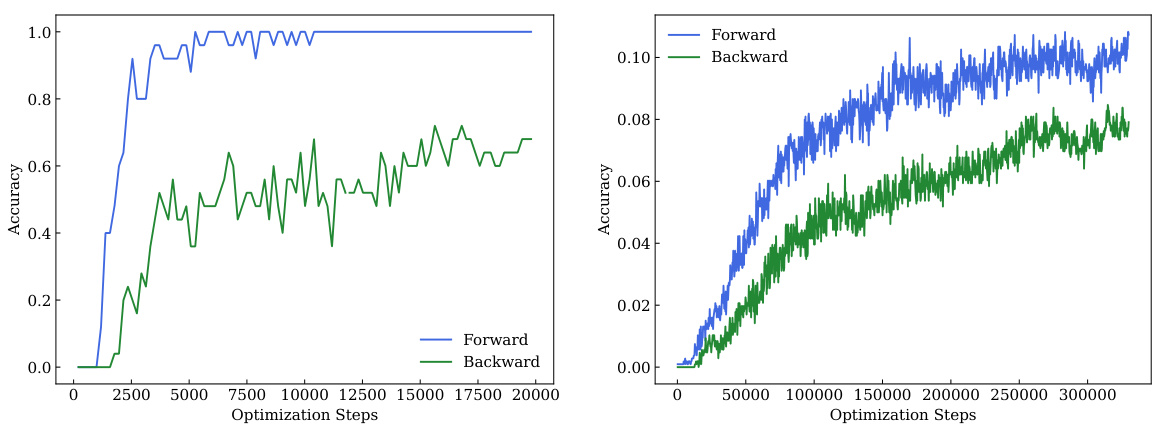

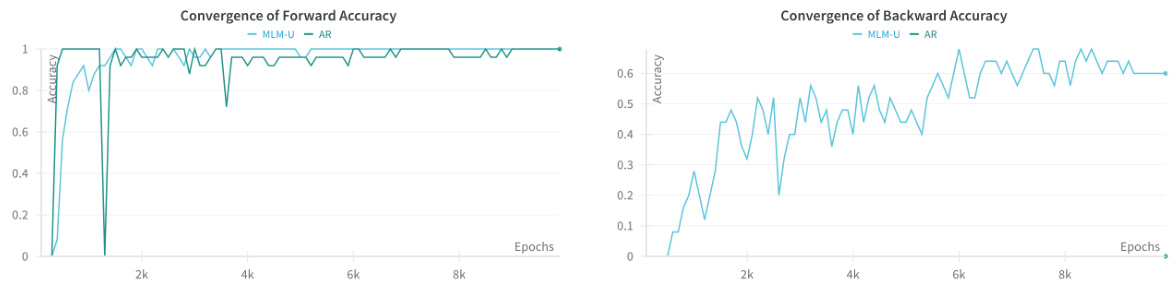

🔼 This figure shows the accuracy curves for training with MLM-U for both Bios and WikiReversal datasets. The left panel shows that the model gradually learns both forward and backward questions throughout training. The backward accuracy shows an upward trend even after 20k optimization steps. The right panel shows a similar trend in the delayed generalization in WikiReversal for both forward and backward questions after 300k optimization steps. These results demonstrate that the MLM-U objective is more challenging and exhibits delayed generalization relative to standard next-token prediction training.

read the caption

Figure 8: Accuracy in Forward/Backward Questions on the Bios dataset (left) and the Wikireversal dataset (right)

🔼 This figure compares the performance of MLM-U and AR models on a simplified retrieval task with only two tokens. It shows that MLM-U achieves perfect accuracy in both forward and backward retrieval scenarios, while AR struggles to learn the backward direction. This highlights the superior ability of MLM-U to handle different factorizations of the data, addressing the factorization curse.

read the caption

Figure 7: Performance of MLM-U versus AR in the two-token setting. We train both MLM-U and AR in a two-token variant of the retrieval task from from Section 3.1. We find MLM-U reaches 100% forward and backward whereas AR struggles to learn the backwards setting.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments evaluating different training methods on two tasks: a simple retrieval task and a more complex relationship task. The retrieval task tests the model’s ability to retrieve information given a key and value, in both forward and reverse order. The relationship task tests whether the model understands non-reciprocal relationships—that is, relationships that don’t work both ways. The table compares standard autoregressive (AR) training, AR training with reversed sequences, masked language modeling (MLM), and a novel uniform-rate MLM (MLM-U). The results highlight the superior performance of MLM-U in handling non-reciprocal relationships, illustrating its ability to resolve the ‘reversal curse’.

read the caption

Table 1: Exact match accuracy of different training paradigms on (Top) the retrieval task and (Bottom) relationship task. Due to the non-reciprocal nature of the relationship, a model that swaps the subject and object will make errors (e.g., inferring B is A's child from A being B's child). Shown in the bottom row. Entity reversal without a delimiter is marked with a*. Maximum values are bold.

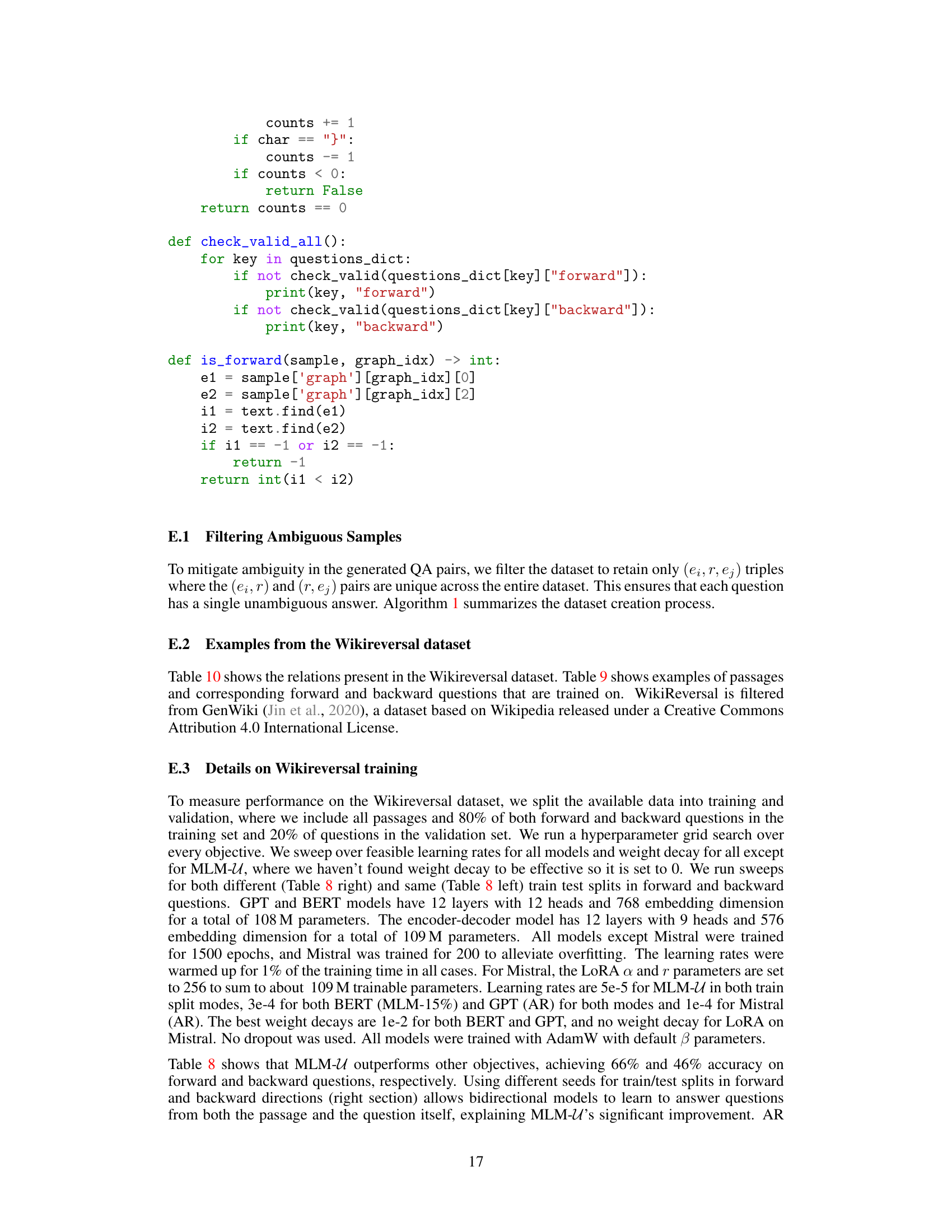

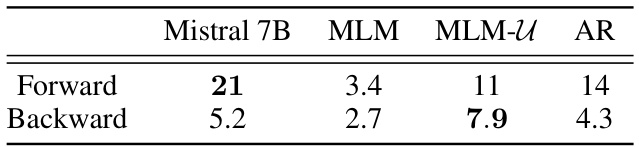

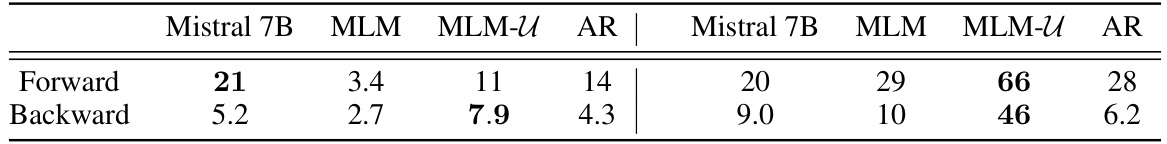

🔼 This table shows the accuracy of different models (Mistral 7B, MLM, MLM-U, and AR) on a question answering task using the WikiReversal dataset. The WikiReversal dataset consists of passages and corresponding forward and backward questions extracted from Wikipedia articles. The table shows that MLM-U performs significantly better on the backward questions, demonstrating its robustness to the reversal curse.

read the caption

Table 3: Wikireversal task exact match QA accuracies. MLM-U, MLM and AR are are 100M parameter models trained from scratch.

🔼 This table presents the results of a simple path-finding task designed to test the planning capabilities of language models. The task involves predicting the sequence of nodes along a path leading to a specified final node, given a symbolic representation of the graph. The table compares the performance of standard autoregressive (AR) training, AR with reversed sequences, and MLM-U (Uniform Rate Masked Language Modeling) which is factorization-agnostic. The results show that MLM-U significantly outperforms the other methods, demonstrating its ability to perform planning tasks effectively.

read the caption

Figure 5: Star Graph Task: Illustration and Performance Comparison. The illustration shows the 'Clever Hans' failure mode with teacher-forced AR ((Bachmann & Nagarajan, 2024) adapted).

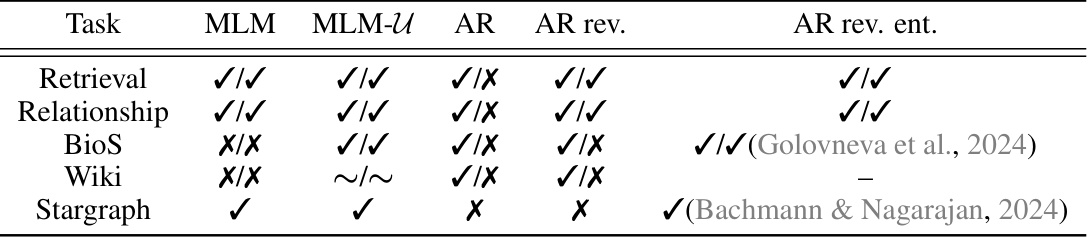

🔼 This table summarizes the performance of different training methods (MLM, MLM-U, AR, AR with reversed sequences, AR with reversed entities) across various tasks (Retrieval, Relationship, BioS, Wiki, Stargraph). Each cell represents whether the method successfully performed the task in the forward and backward directions, indicated by ✓ (success) and X (failure). The ~ symbol in the Wiki task indicates that MLM-U’s performance was not strong enough to declare success or failure unequivocally. The table highlights the strengths and weaknesses of each method in different scenarios, showcasing the effects of training objective and data characteristics on the ability to retrieve information in various directions.

read the caption

Table 4: Summary of qualitative results, formatted as (forward)/(backward). Stargraph only has one direction.

🔼 This table presents the per-token accuracy results for a retrieval task, broken down by training method (AR, AR with reversed sequences, MLM with various masking rates, MLM-U, and PLM). It shows the accuracy for both forward (predicting the value given the key) and backward (predicting the key given the value) directions. The results highlight the differences in performance between various training methods. Specifically, it shows how MLM-U and PLM achieve near-perfect accuracy in both directions, whereas others struggle with the backward direction.

read the caption

Table 5: Retrieval Task forward and backward per token accuracy of different training paradigms.

🔼 This table presents the results of the BioS experiment, focusing on the accuracy of property retrieval in both forward and backward directions. The forward direction involves predicting the full name given the birthdate, while the backward direction predicts the birthdate given the full name. Different training methods (AR, AR w/reverse, MLM variants, PLM, and MLM-U) are compared to assess their effectiveness in handling both directions of the task. The table shows that MLM-U achieves the best performance, with the autoregressive methods (AR) failing completely in the backward direction.

read the caption

Table 6: BioS exact match accuracy for property retrieval in the backward direction (birth date to full name) and in the forward direction (full name to birthdate).

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments comparing different training methods (Autoregressive (AR), AR with reversed sequences, Masked Language Modeling (MLM) with different masking rates, and Uniform-Rate MLM (MLM-U)) on two tasks: a simple retrieval task and a relationship task. The retrieval task evaluates the models’ ability to retrieve information regardless of the order it was presented during training, while the relationship task assesses the models’ understanding of asymmetric relationships. The results showcase the effectiveness of MLM-U in handling both symmetric and asymmetric relationships, while AR and reversed sequence AR training methods exhibit limitations, particularly in handling asymmetric relationships.

read the caption

Table 1: Exact match accuracy of different training paradigms on (Top) the retrieval task and (Bottom) relationship task. Due to the non-reciprocal nature of the relationship, a model that swaps the subject and object will make errors (e.g., inferring B is A's child from A being B's child). Shown in the bottom row. Entity reversal without a delimiter is marked with a*. Maximum values are bold.

🔼 This table presents the results of a question-answering task on the WikiReversal dataset. The task involves answering questions about factual knowledge in both forward and backward directions. Three different model training objectives are compared: MLM-U (uniform-rate masked language modeling), MLM (standard masked language modeling), and AR (autoregressive). Mistral 7B is included as a larger pretrained model, finetuned on the dataset. The table shows that MLM-U significantly outperforms other models, especially in answering backward questions which test the model’s ability to retrieve information based on later rather than prior context. This demonstrates that factorization-agnostic training is better at knowledge retrieval compared to the common left-to-right training used in most LLMs.

read the caption

Table 3: Wikireversal task exact match QA accuracies. MLM-U, MLM and AR are are 100M parameter models trained from scratch.

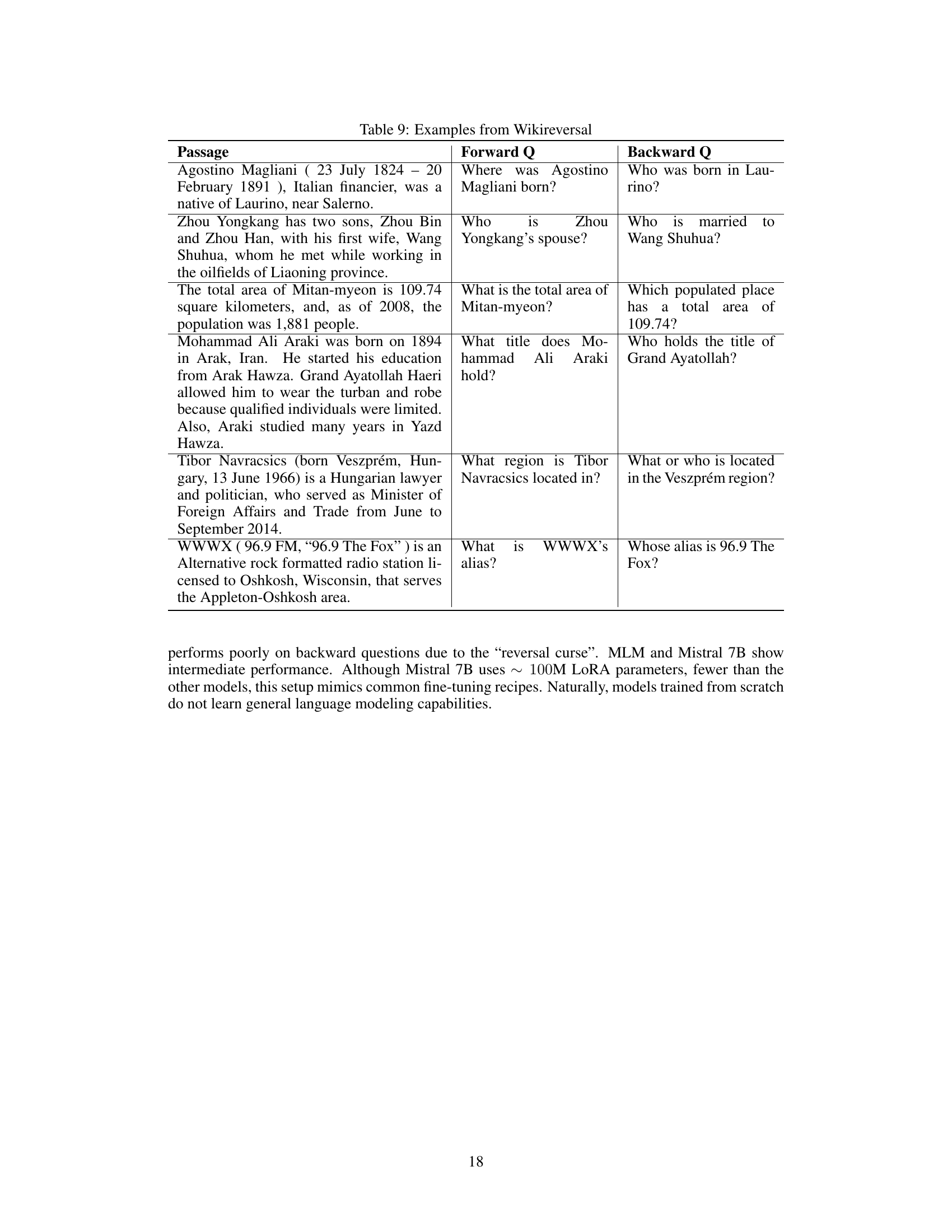

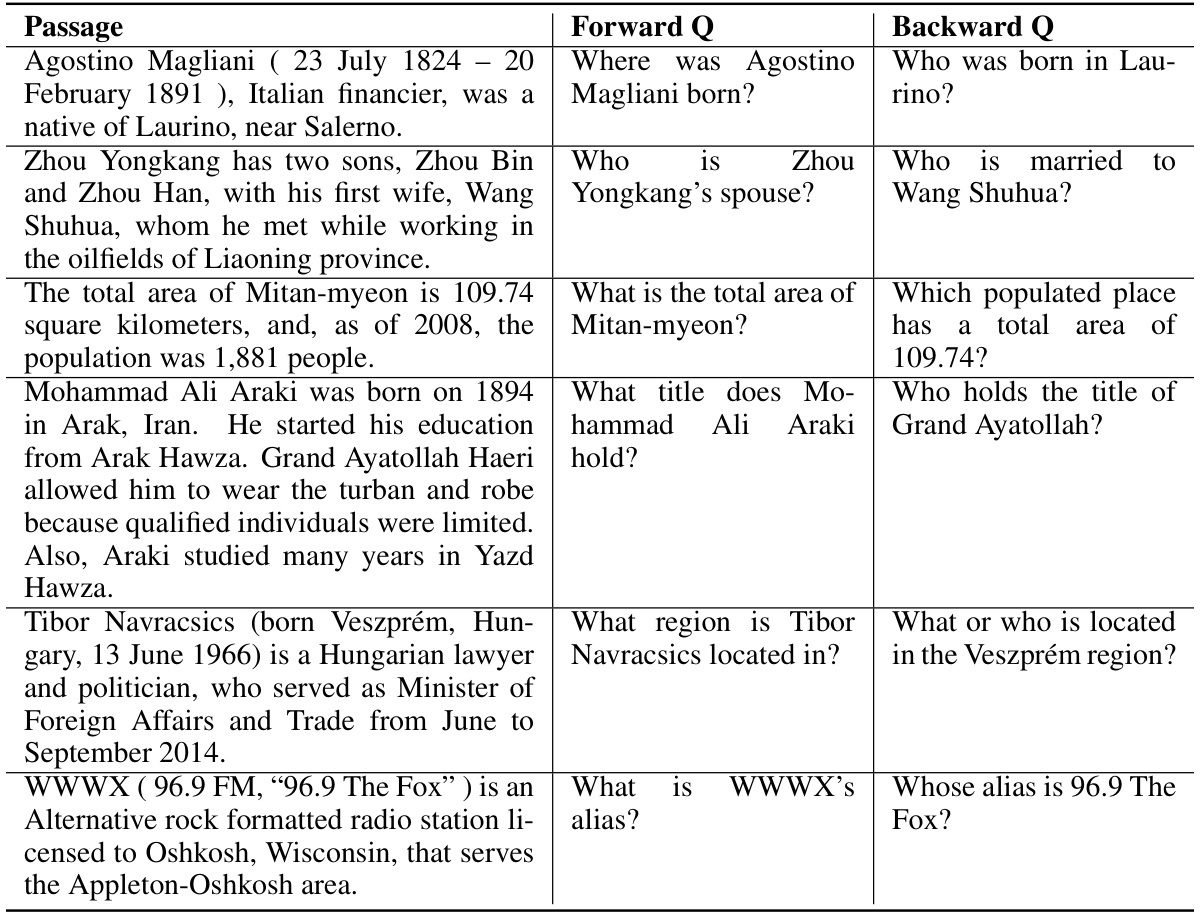

🔼 This table presents example passages from the Wikireversal dataset, along with their corresponding forward and backward questions. The forward questions query the tail of a relation triple, while the backward questions query the head. This illustrates the challenge of the reversal curse, where the model struggles to answer questions when the information is presented in a different order than during training.

read the caption

Table 9: Examples from Wikireversal

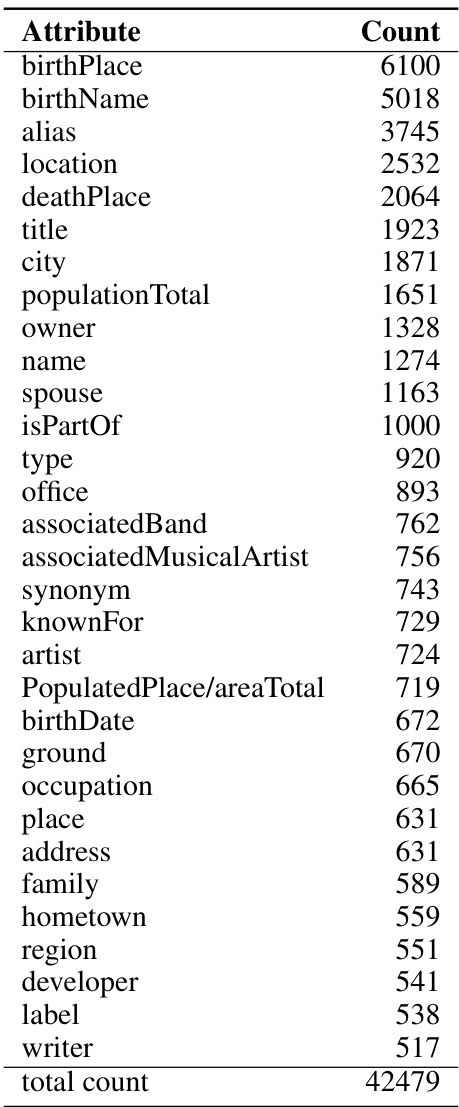

🔼 This table lists the different relations present in the WikiReversal dataset and their respective counts. The relations represent connections between entities in the dataset, such as ‘birthPlace’ linking a person to their birthplace. The counts indicate how many times each relation appears in the dataset.

read the caption

Table 10: Relations in Wikireversal

Full paper#