TL;DR#

Many machine learning problems involve solving nonconvex minimax optimization problems, but existing zeroth-order (ZO) algorithms suffer from high computational complexity and require strict assumptions. This is particularly true for solving problems in the black-box setting where gradient information is unavailable. The lack of efficient and robust algorithms limits the application of ZO optimization to many practical machine learning tasks.

This paper introduces a novel algorithm called ZO-GDEGA that solves these issues by offering a unified framework for both deterministic and stochastic nonconvex-concave minimax problems. ZO-GDEGA achieves a lower overall complexity compared to existing methods while requiring weaker assumptions on ZO estimations. The algorithm also demonstrates improved robustness through experimental evaluations on data poisoning attacks and AUC maximization tasks. This makes it a significant advance for solving real-world minimax optimization problems in the black-box setting.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in optimization and machine learning because it addresses the high complexity and stringent conditions of existing zeroth-order minimax optimization algorithms. By introducing ZO-GDEGA, the paper offers a more robust and efficient solution with theoretical guarantees, particularly relevant to black-box optimization problems prevalent in fields like adversarial attacks and AUC maximization. The weaker assumptions and improved complexity make it highly impactful for future research and applications.

Visual Insights#

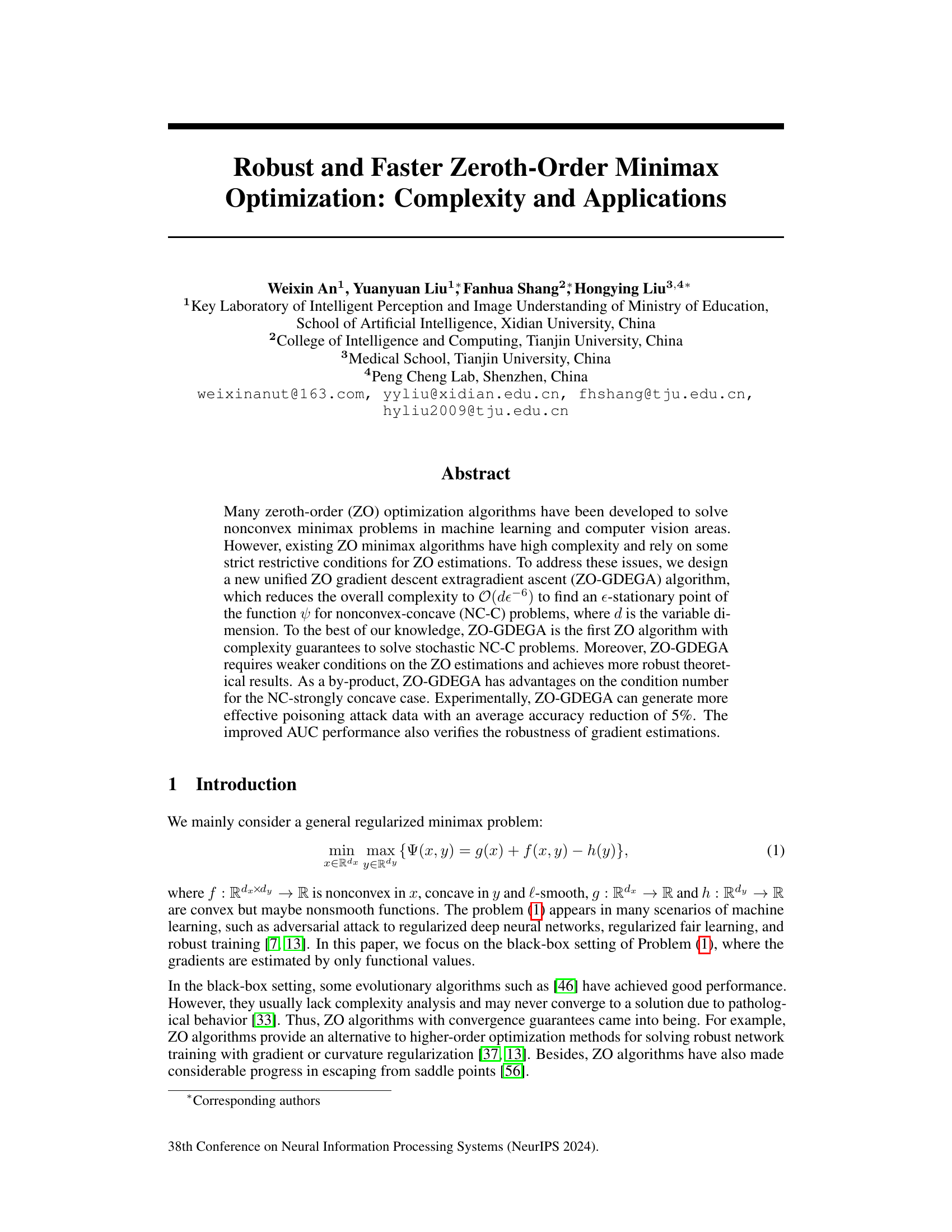

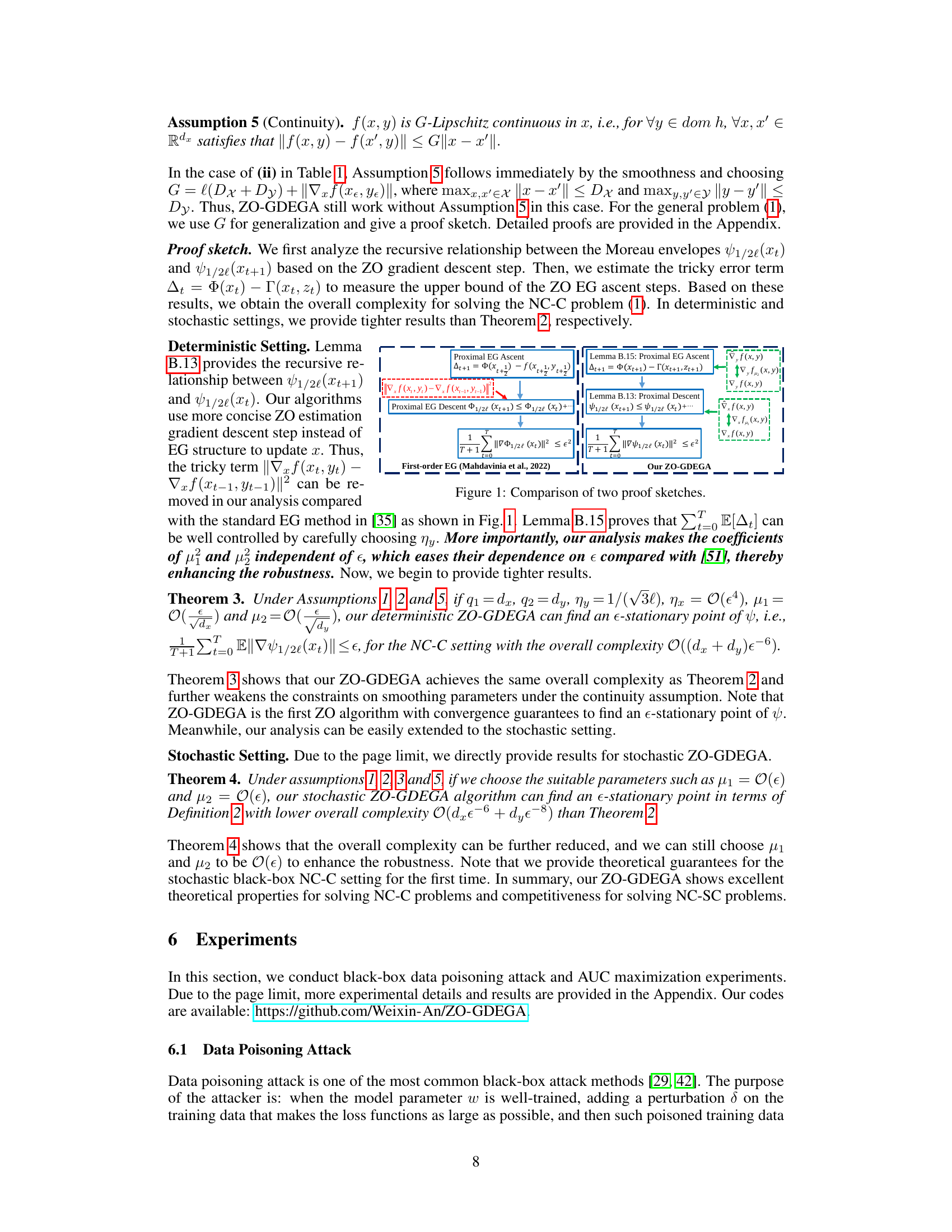

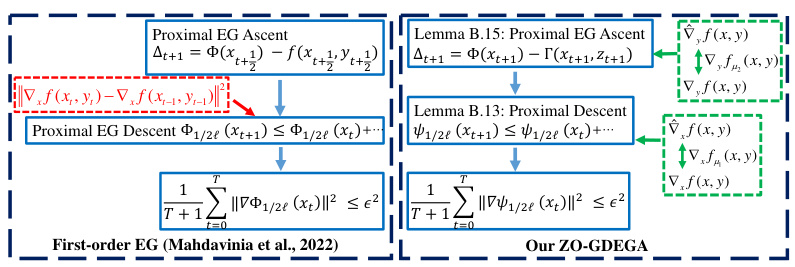

🔼 This figure compares the proof sketches of the standard extragradient (EG) method and the proposed ZO-GDEGA algorithm. The standard EG method involves two proximal gradient steps for both x and y updates, while ZO-GDEGA simplifies the x update using a proximal gradient descent step and uses an extra gradient ascent step for y update to leverage concavity and improve robustness. Both methods aim to minimize the Moreau envelope of the objective function and bound the error term (∆t) related to the EG ascent steps.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of two proof sketches.

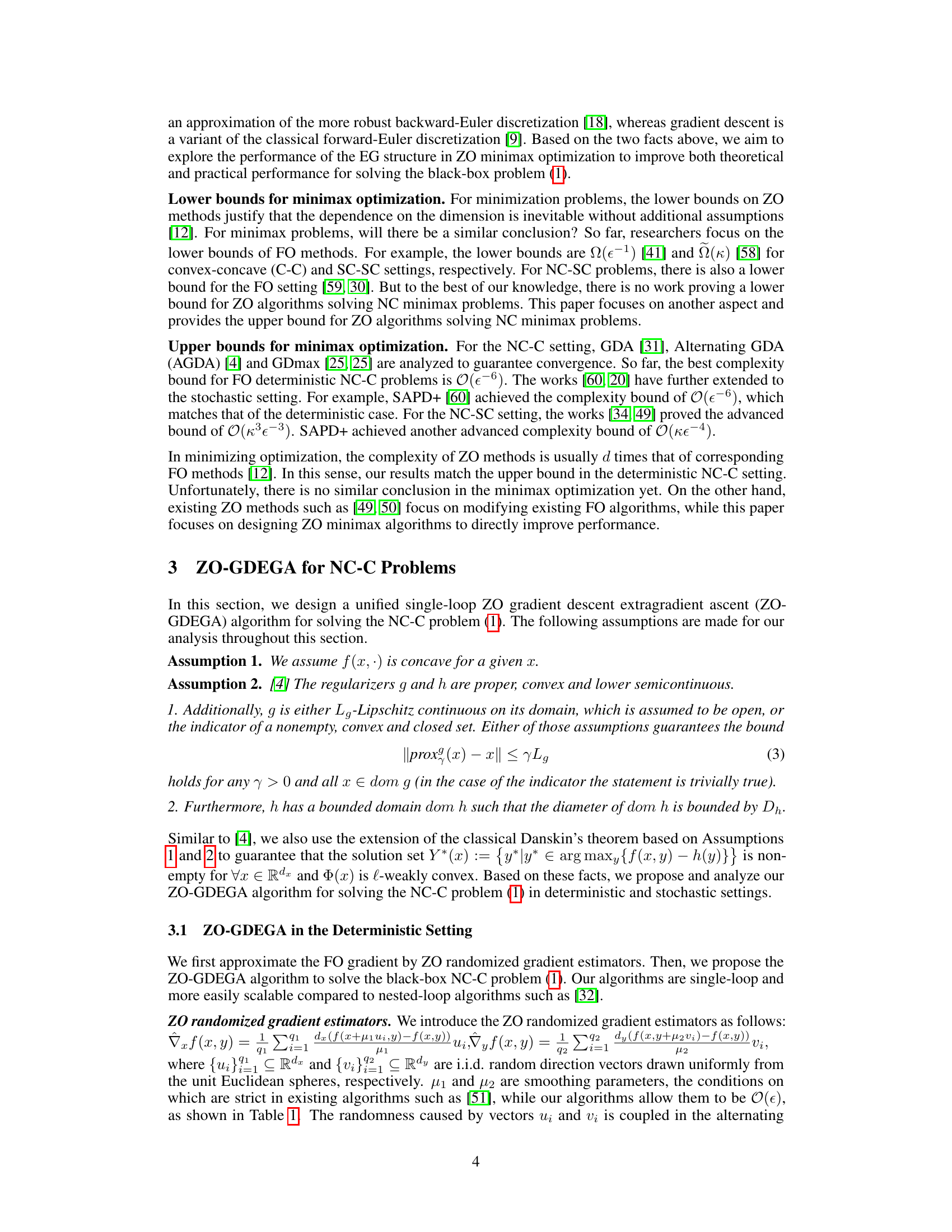

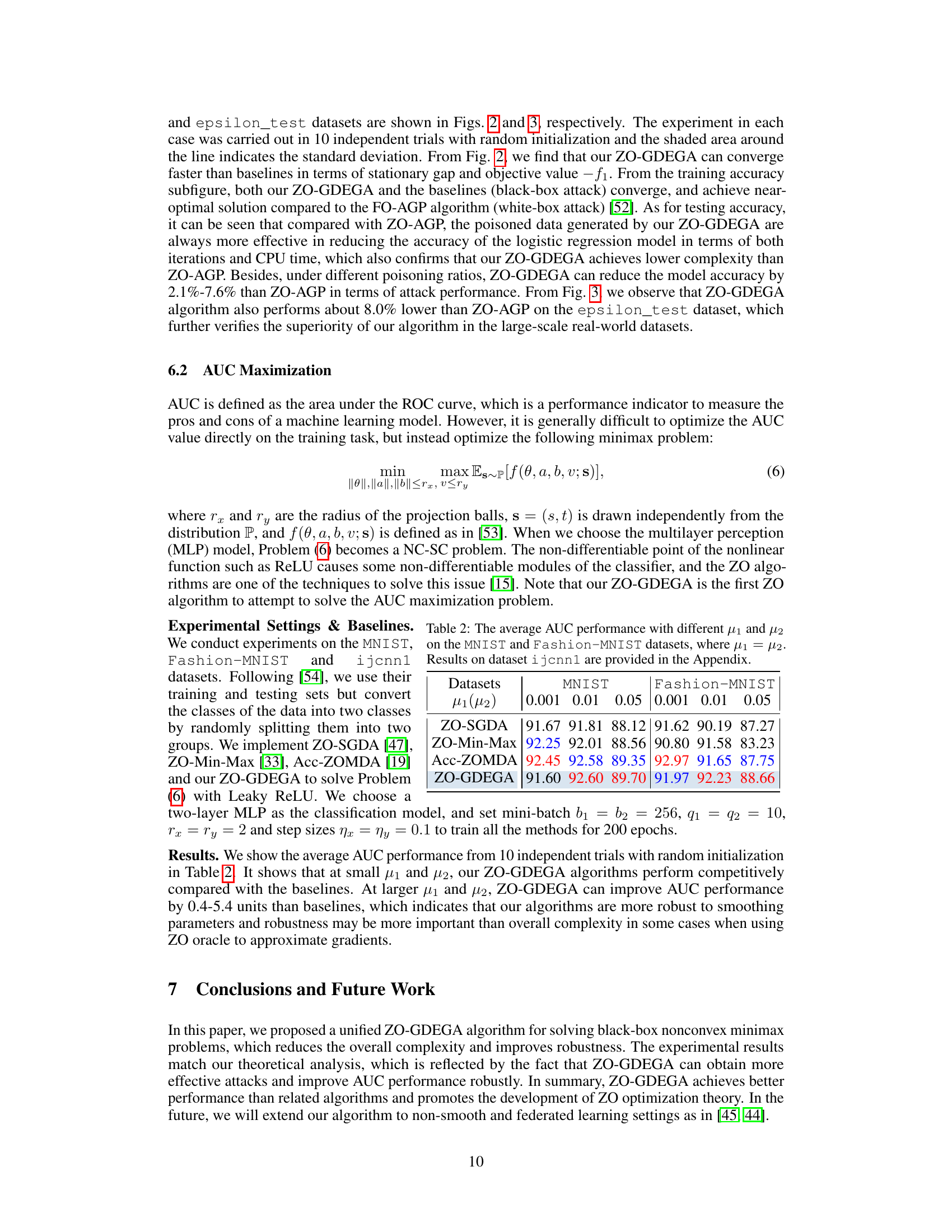

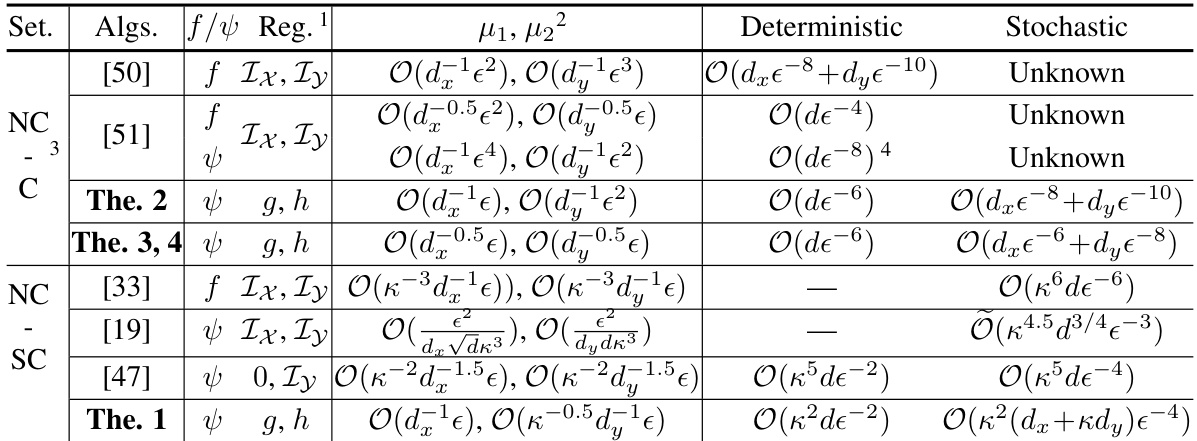

🔼 This table compares the overall zeroth-order (ZO) oracle complexity of different algorithms for finding an e-stationary point in solving nonconvex minimax problems. It shows the complexity for various settings (nonconvex-concave, nonconvex-strongly concave), algorithms, and regularization choices. The complexity is expressed in terms of the dimension (d), condition number (κ), and accuracy (ε). It also distinguishes between deterministic and stochastic settings.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the overall ZO oracle complexity of single-loop algorithms to find an e-stationary point of f (Definition 3) or ψ (Definition 2). κ = l/µ denotes the condition number, d = dx + dy and Õ(·) hides logarithmic terms. Abbreviation: Settings (Set.), Algorithms (Algs.), Regular (Reg.), Theorem (The.).

In-depth insights#

ZO-GDEGA Algorithm#

The proposed ZO-GDEGA algorithm presents a novel approach to zeroth-order minimax optimization, addressing the limitations of existing methods. Its unified single-loop structure offers computational efficiency, achieving a lower overall complexity compared to previous algorithms. A key innovation lies in its integration of the extragradient method, enhancing robustness by allowing for larger tolerance in zeroth-order estimations. This is particularly beneficial when dealing with noisy or inaccurate gradient approximations, a common challenge in black-box optimization scenarios. The algorithm’s effectiveness is supported by theoretical analysis providing complexity guarantees under weaker assumptions, and its practical performance is validated through experiments showcasing improved results in data poisoning attacks and AUC maximization tasks. The algorithm’s robustness to noisy gradients is a significant advantage, broadening its applicability to challenging real-world problems.

Complexity Analysis#

A complexity analysis of an algorithm rigorously examines its resource usage, typically time and space, as a function of input size. For optimization algorithms, this often involves analyzing the number of iterations required to achieve a certain level of accuracy or the amount of memory needed to store intermediate results. The analysis frequently focuses on characterizing the algorithm’s scaling behavior, identifying whether the runtime or space requirements grow linearly, polynomially, or exponentially with the input size. Different types of complexity exist: worst-case, average-case, and best-case complexities all offer distinct perspectives on performance. A key aspect is considering the specific computational model underlying the analysis: for instance, is each arithmetic operation considered a single time unit, or are more nuanced assessments made based on hardware-specific instructions? Identifying and carefully managing dominant factors affecting complexity, such as the condition number of a matrix in linear algebra problems or the smoothness of functions in optimization, are often crucial for effective optimization. Tight bounds on computational complexity, indicating both upper and lower limits, provide the most informative characterization, although in practice obtaining tight bounds can be extremely challenging. Stochastic algorithms introduce further complexities due to randomness. The analysis often involves probabilistic arguments and expectations, focusing on convergence rates, making it necessary to carefully distinguish between expected and high-probability bounds.

Robustness of ZO#

The robustness of zeroth-order (ZO) optimization methods is a crucial consideration, as they rely on noisy estimations of gradients. ZO algorithms’ performance is sensitive to the choice of smoothing parameters and the quality of function evaluations. The paper’s contribution likely involves demonstrating enhanced robustness compared to existing ZO algorithms. This might be achieved through theoretical analysis proving tolerance to larger smoothing parameters or empirical results showcasing superior performance under noisy conditions. A key aspect would be quantifying the impact of noisy estimations on the algorithm’s convergence rate and the accuracy of the solution. The discussion should address how ZO-GDEGA specifically mitigates the adverse effects of noisy estimations and how this impacts its practical applicability in black-box scenarios where gradient information is unavailable. The overall analysis should highlight the trade-off between robustness and computational complexity. A robust method will ideally maintain reasonable efficiency even when facing significant noise levels.

Poisoning Attacks#

Data poisoning attacks, a significant concern in machine learning, involve surreptitiously injecting malicious data into training datasets to compromise model accuracy or functionality. The goal is to manipulate the model’s behavior towards a specific, adversarial objective. The paper explores this through a robust zeroth-order gradient descent extragradient ascent (ZO-GDEGA) algorithm. This algorithm is especially relevant because it operates effectively in black-box scenarios where the model’s internal workings and gradient information are unavailable, a common constraint in real-world poisoning attacks. ZO-GDEGA achieves lower complexity compared to existing methods while demonstrating enhanced robustness in handling the inherent uncertainties of zeroth-order estimations. The experimental evaluation on a data poisoning task demonstrates its efficacy in generating effective poisoning data, achieving an average accuracy reduction of 5% in the target model. This work highlights the practical advantages of ZO-GDEGA for generating more effective poisoning attacks than prior approaches under various settings, and opens up opportunities for studying more sophisticated attack strategies in future research.

AUC Maximization#

The section on “AUC Maximization” explores a common challenge in machine learning: optimizing the Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC). AUC, a crucial metric for evaluating classifier performance, is often difficult to optimize directly. The authors frame AUC maximization as a minimax problem, a strategic move that allows them to leverage their proposed zeroth-order gradient descent extragradient ascent (ZO-GDEGA) algorithm. This approach is particularly valuable when dealing with black-box models or situations where gradient calculations are computationally expensive or infeasible, as is often the case with complex neural network architectures and non-differentiable activation functions. The experiments on benchmark datasets, such as MNIST and Fashion-MNIST, demonstrate the effectiveness of ZO-GDEGA in achieving competitive AUC scores. A key strength highlighted is the algorithm’s robustness to noisy or imprecise gradient estimations, a common issue in zeroth-order methods. The results suggest that ZO-GDEGA not only provides a practical solution for AUC maximization in challenging scenarios but also offers improved robustness compared to existing zeroth-order optimization techniques.

More visual insights#

More on figures

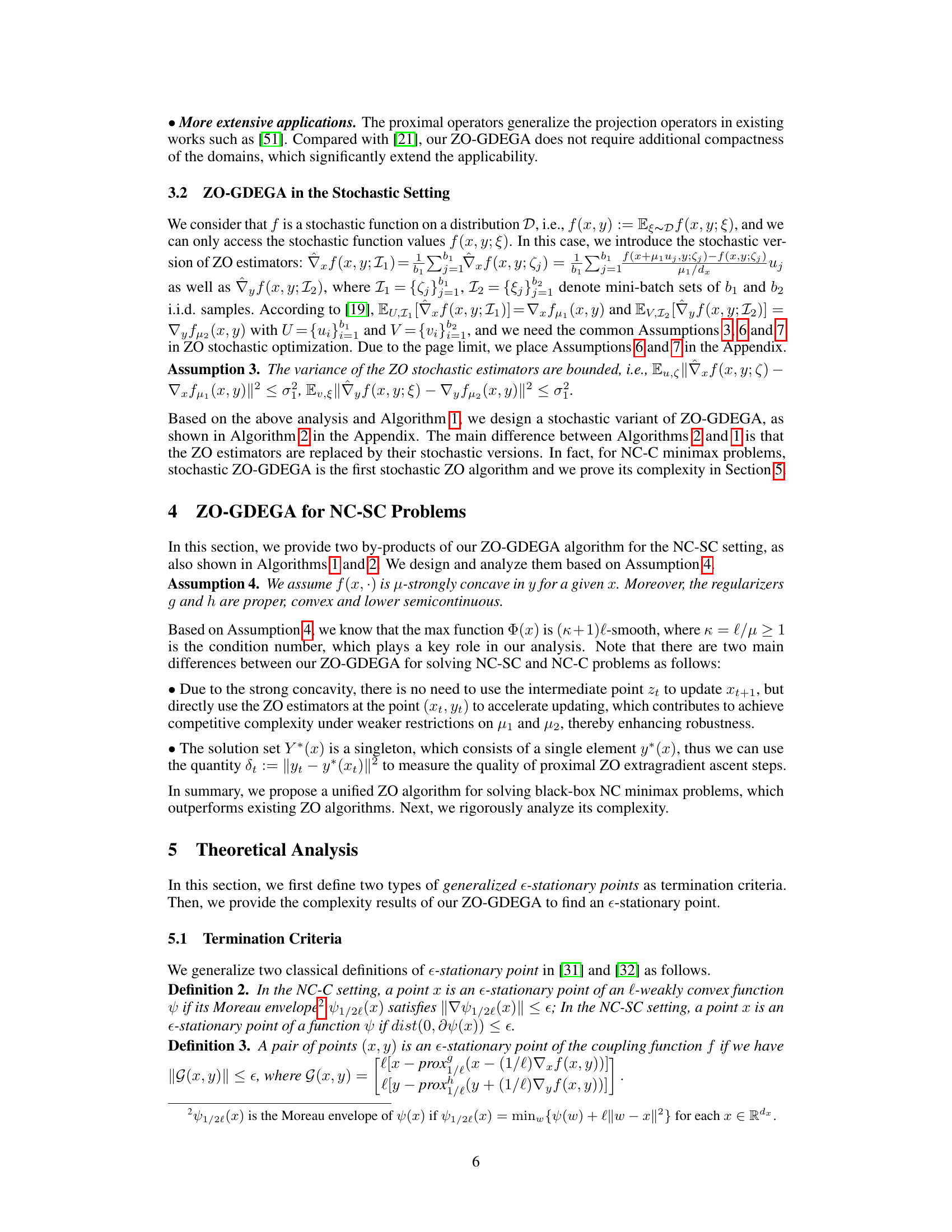

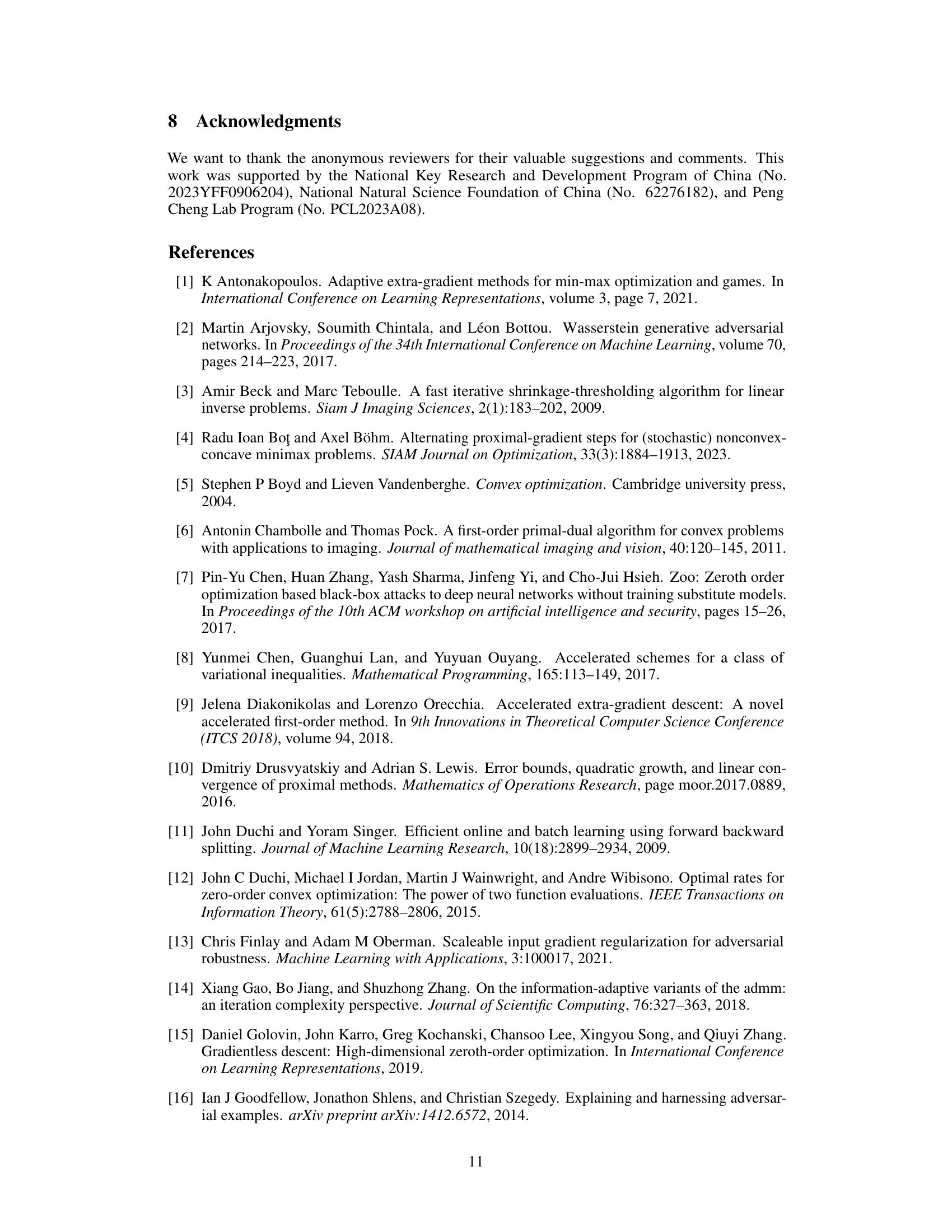

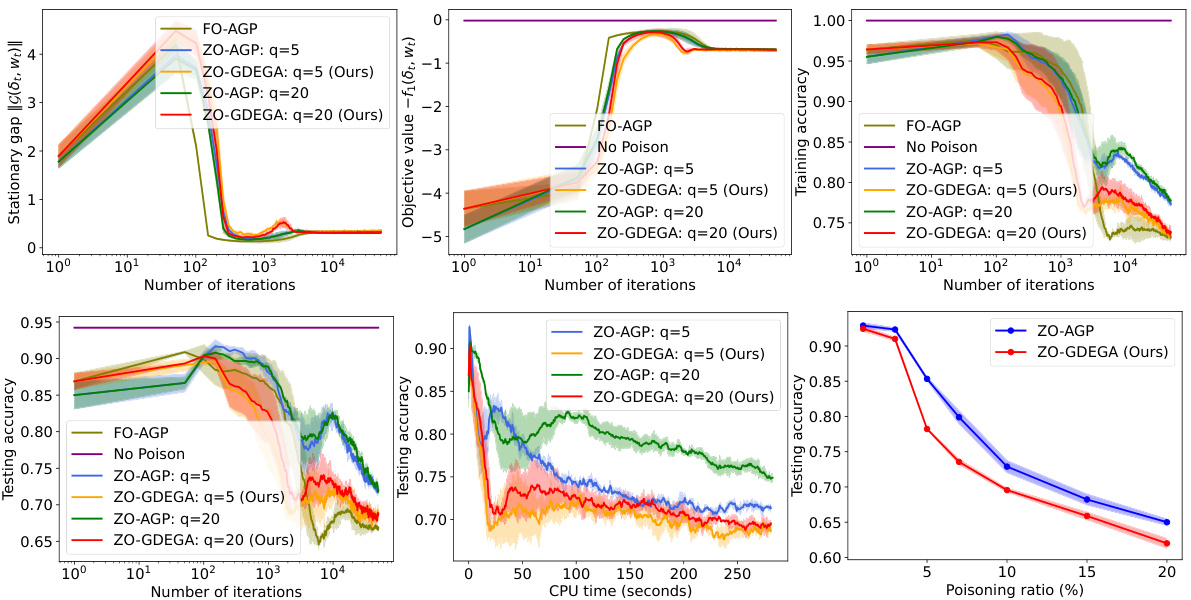

🔼 This figure compares the performance of ZO-AGP and the proposed ZO-GDEGA algorithm on a synthetic dataset for a data poisoning attack against a logistic regression model. It shows plots of the stationary gap (a measure of convergence), the objective function value, training accuracy, testing accuracy, CPU time, and poisoning ratio. The results demonstrate that ZO-GDEGA converges faster and achieves a lower testing accuracy (indicating a more effective attack) than ZO-AGP, especially for larger values of the smoothing parameter (q).

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of the results for the logistic regression model attacked by poisoned data generated by ZO-AGP and ZO-GDEGA on the synthetic dataset.

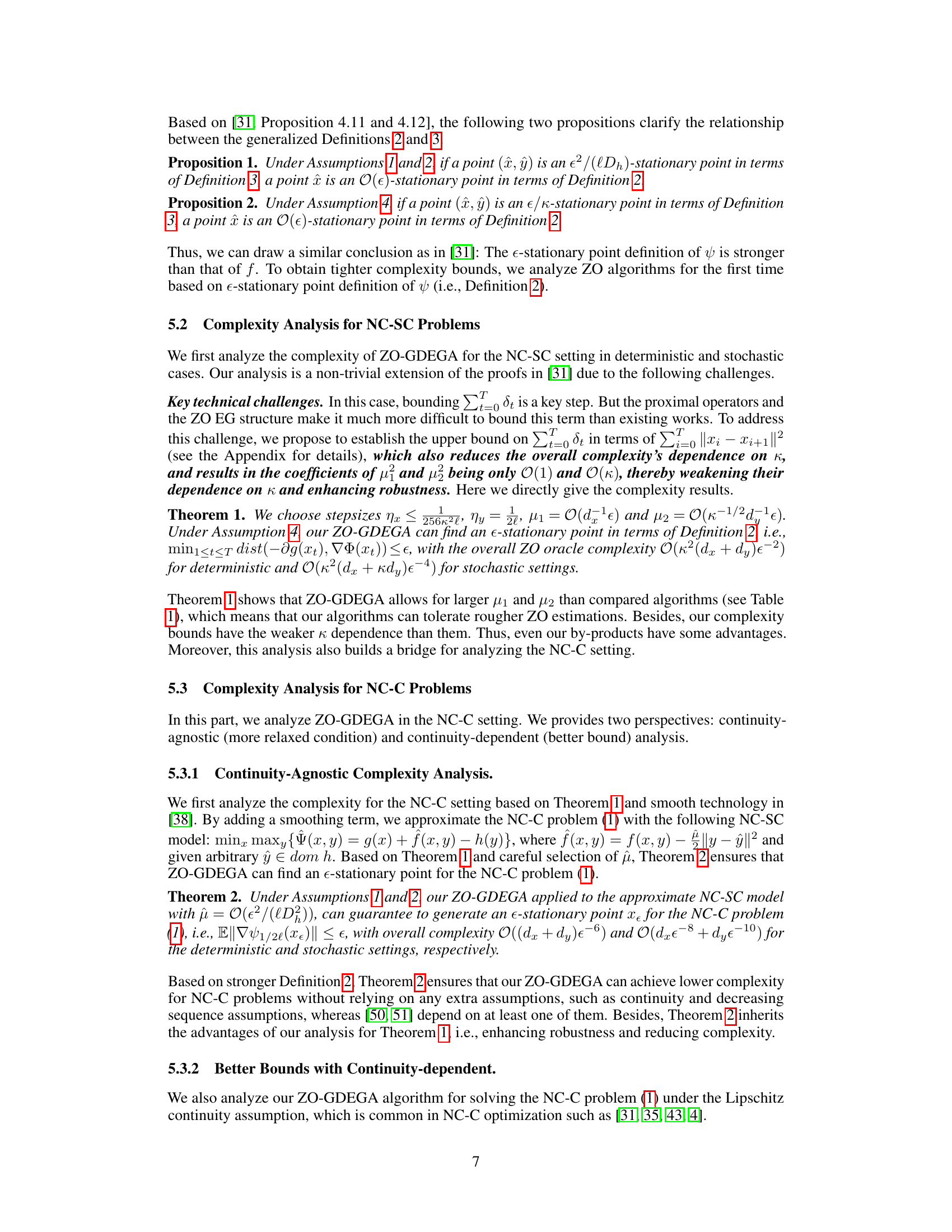

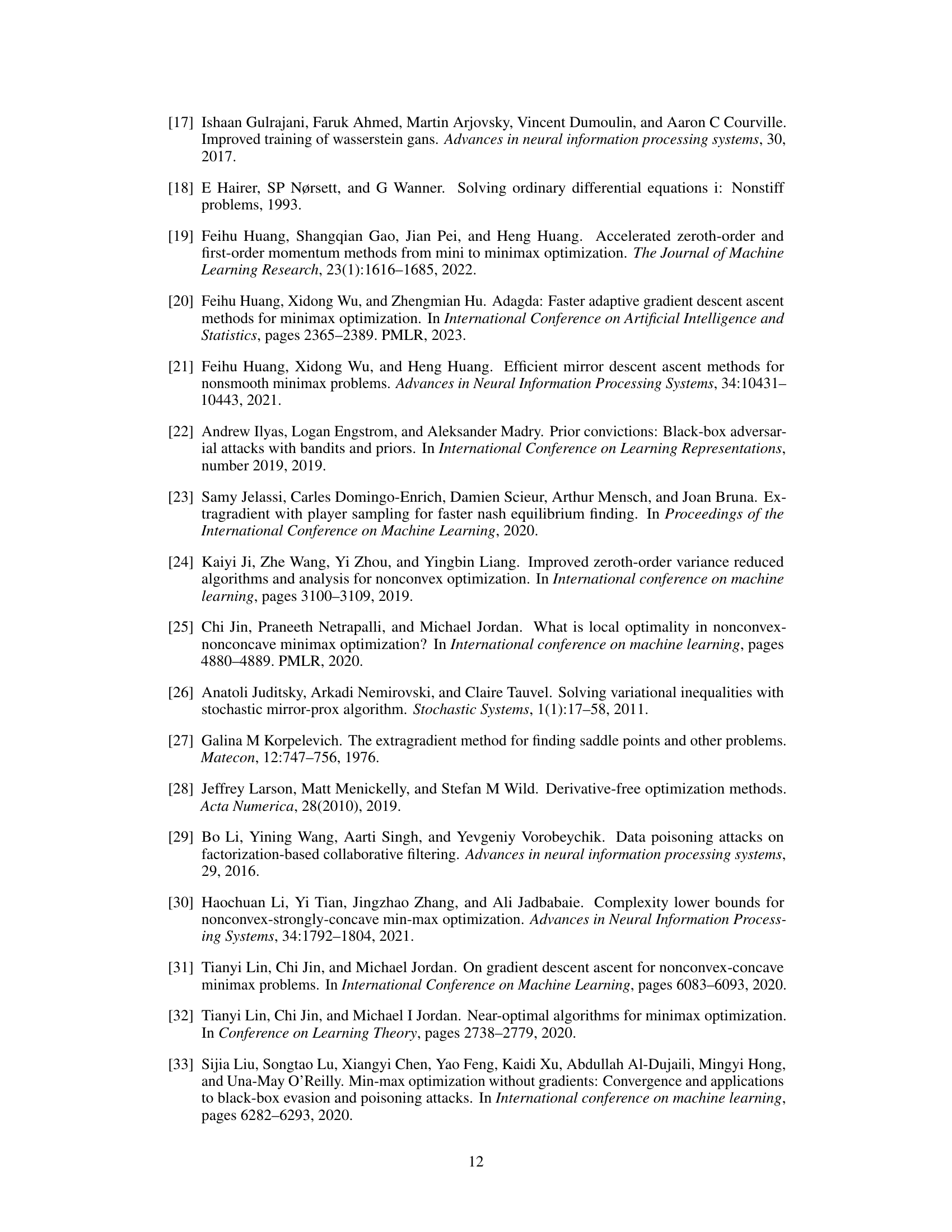

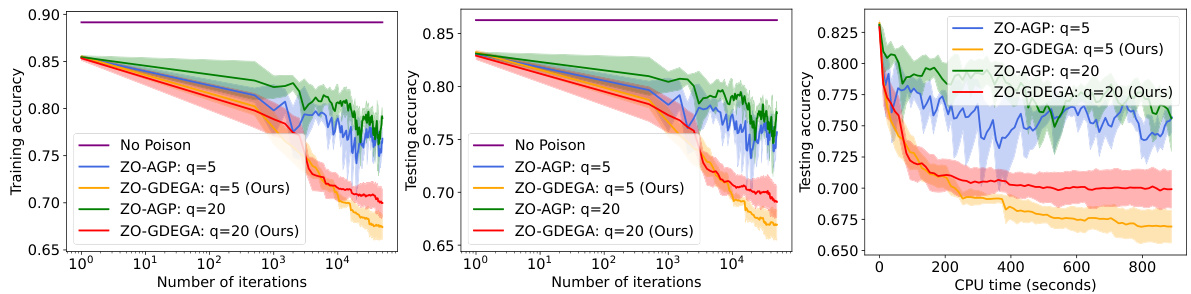

🔼 This figure compares the performance of ZO-AGP and ZO-GDEGA in a data poisoning attack on the large-scale epsilon_test dataset. It shows training accuracy, testing accuracy, and objective function values (-f1) over the number of iterations and CPU time. The results demonstrate that ZO-GDEGA converges faster and achieves a lower objective function value compared to ZO-AGP, suggesting improved efficiency and robustness. The poisoning ratio is a parameter that influences the degree of attack success.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of the attack results for data poisoning attack on the large-scale epsilon_test dataset.

Full paper#