TL;DR#

Many scientific and engineering problems involve solving nonlinear partial differential equations (PDEs). Traditional numerical methods often struggle with nonlinear solvers, especially when multiple solutions exist. These methods can be computationally expensive and may fail near bifurcation points. This necessitates the development of new methods that can efficiently and reliably find all solutions.

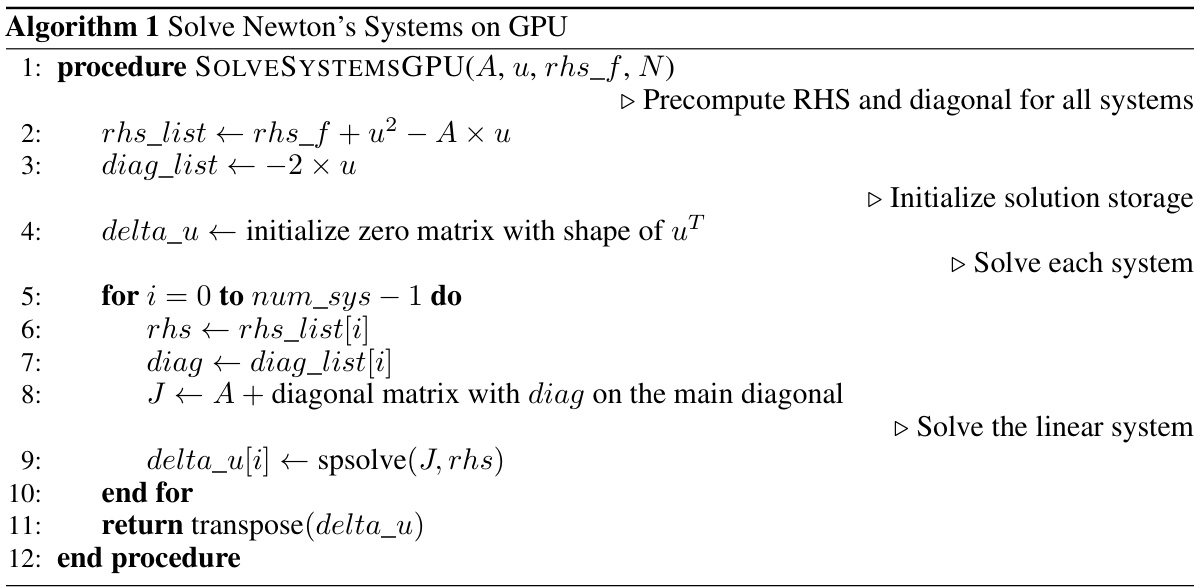

This research proposes a novel approach: the Newton Informed Neural Operator. This method leverages the power of neural networks to learn the Newton solver for nonlinear PDEs. By integrating traditional numerical techniques with a neural network, this approach efficiently learns the nonlinear mapping at each iteration of the Newton’s method. The result is a single learning process that yields multiple solutions while using far less data than other neural network methods. This significantly reduces computational cost and makes the method applicable to problems with limited data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to solving nonlinear PDEs with multiple solutions, a significant challenge in many scientific fields. The Newton Informed Neural Operator efficiently learns the Newton solver, leading to faster computation and the ability to discover multiple solutions with limited data. This opens new avenues for tackling complex, real-world problems where traditional numerical methods struggle.

Visual Insights#

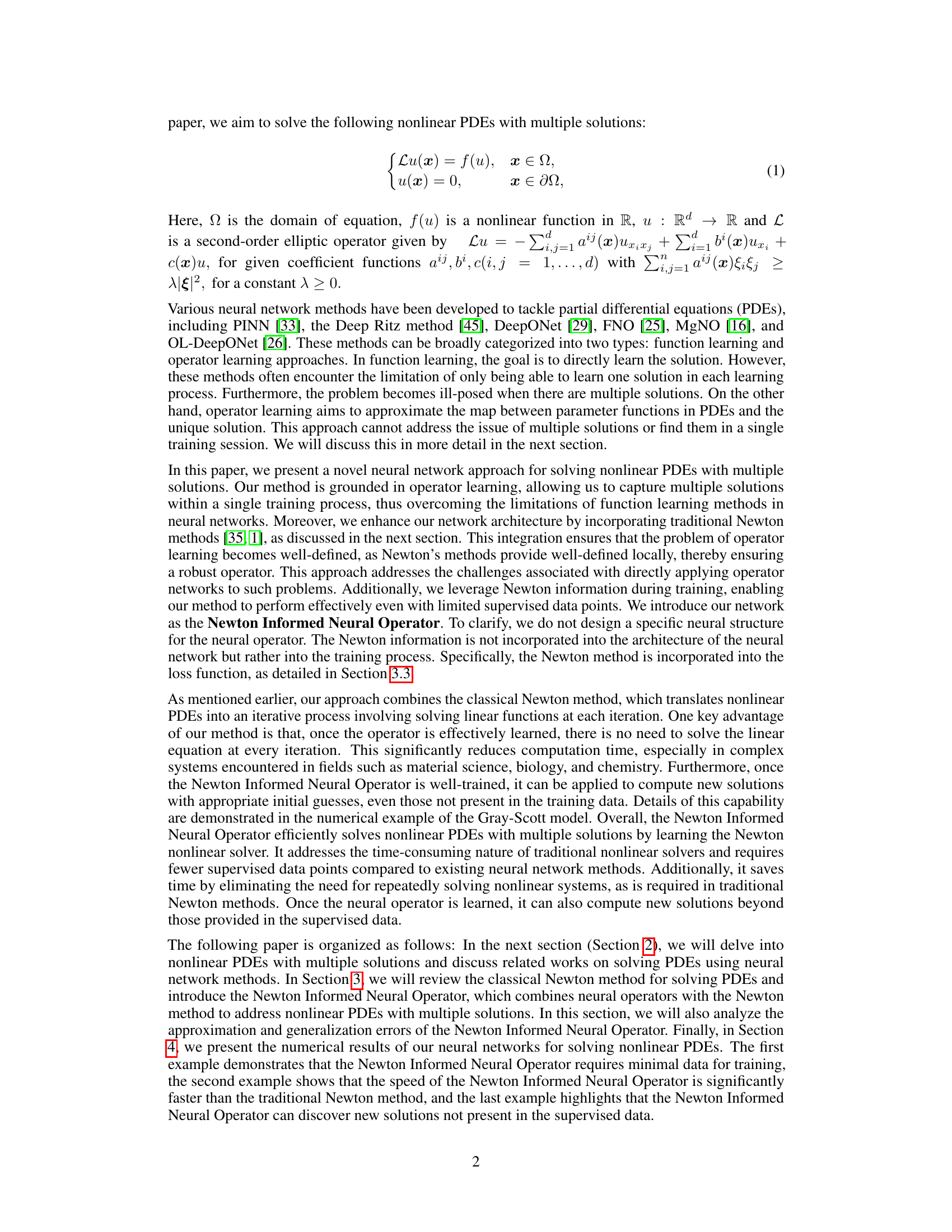

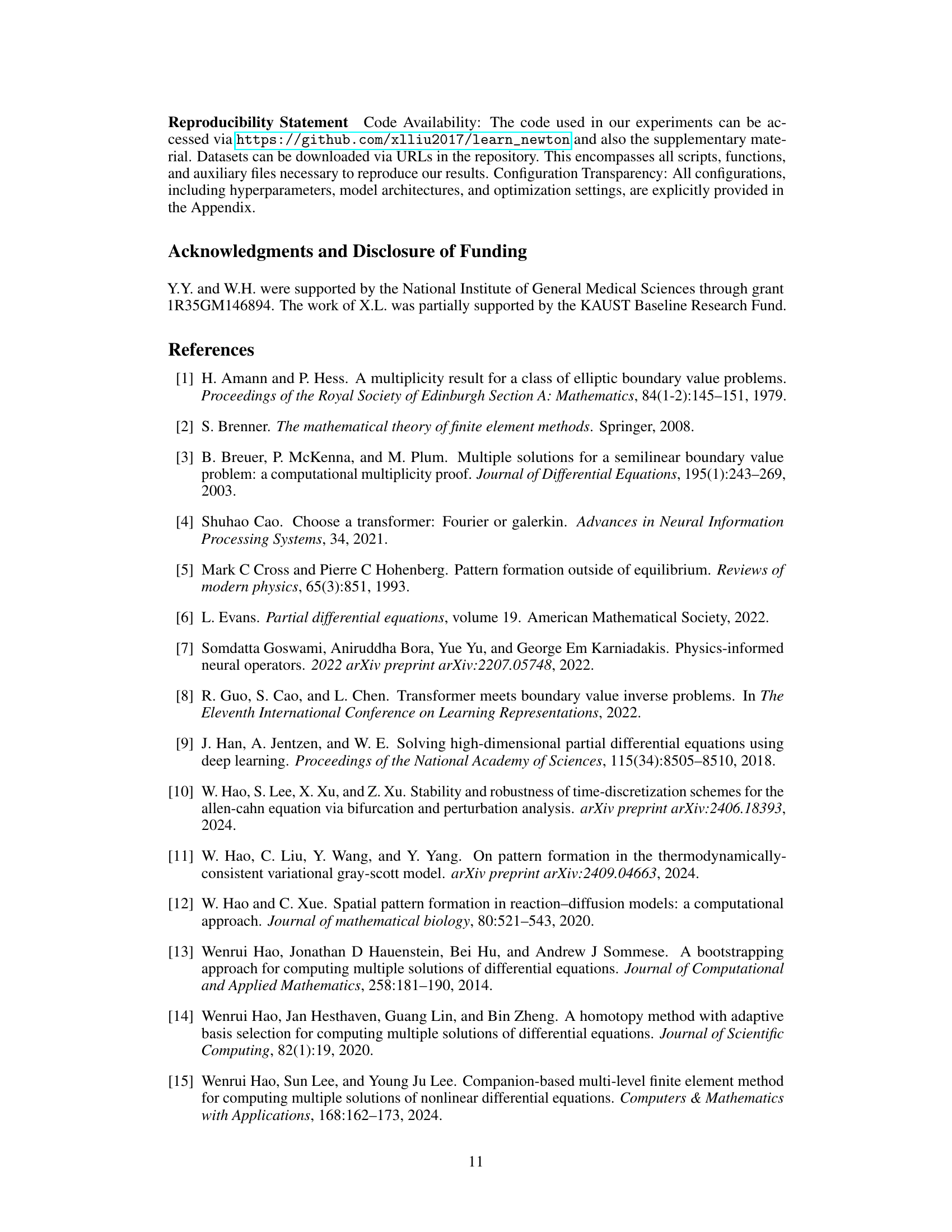

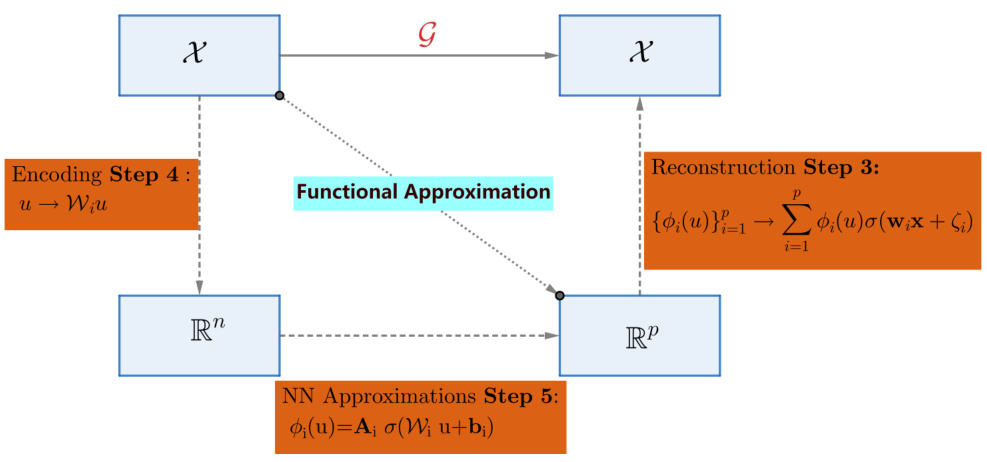

🔼 This figure is a sketch of the proof for Theorem 1. It illustrates the steps involved in approximating the Newton operator using a neural network. The process begins with an encoding step, followed by functional approximation using a neural network. Finally, a reconstruction step produces the desired output. The diagram highlights the core components and flow of the proof, which involves combining classical numerical methods with neural networks.

read the caption

Figure 1: The sketch of proof for Theorem 1.

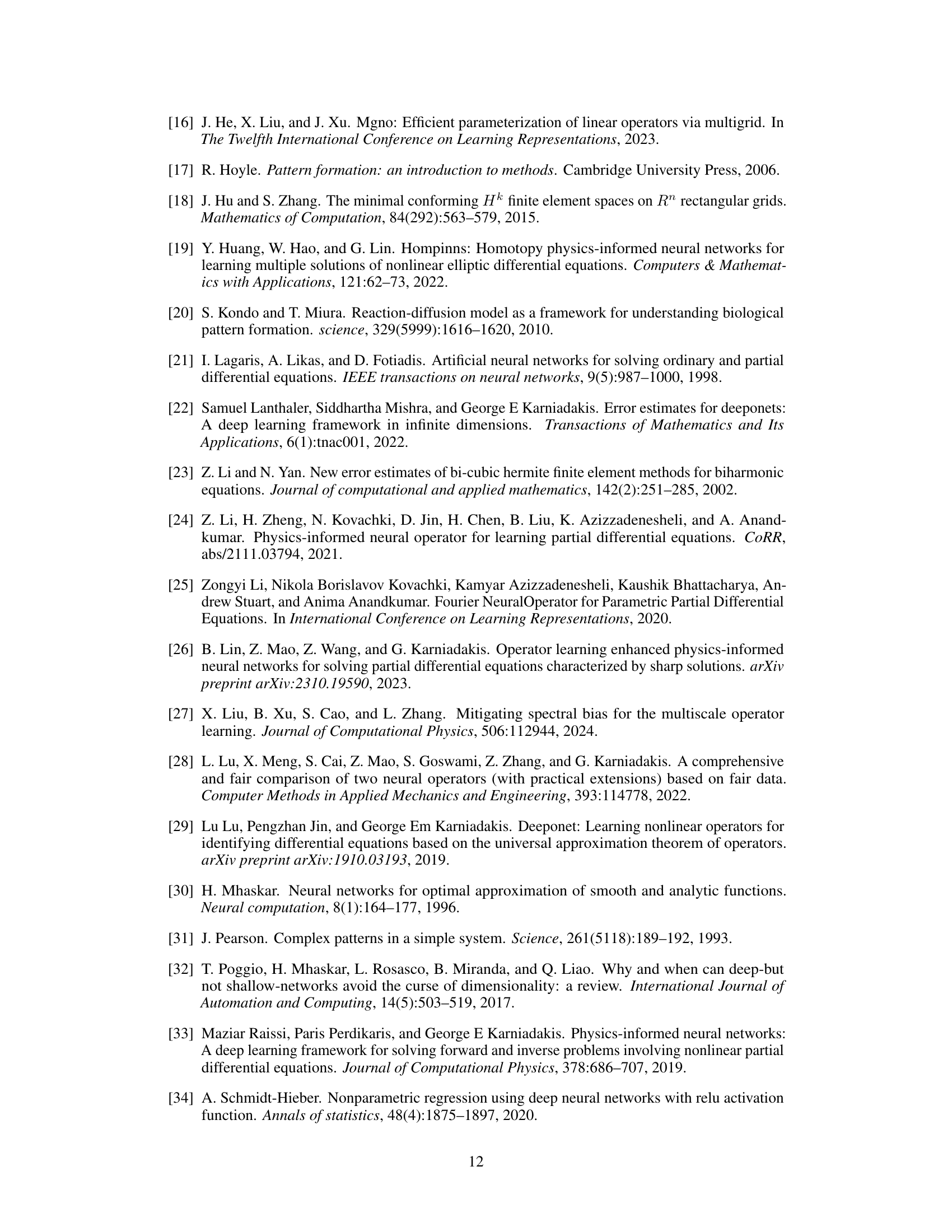

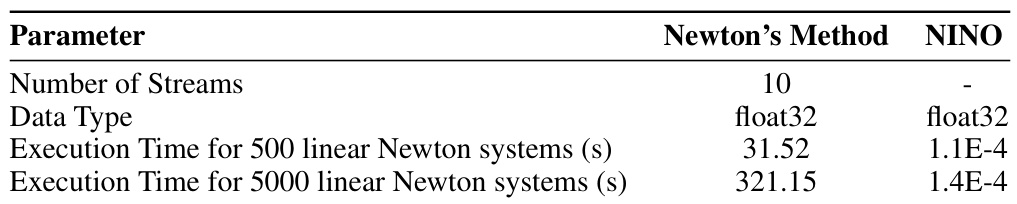

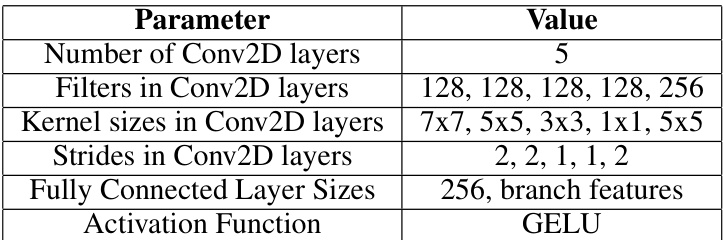

🔼 This table compares the computational time required for solving 500 and 5000 linear Newton systems using both the traditional Newton’s method and the proposed Newton Informed Neural Operator (NINO). It highlights NINO’s superior efficiency, especially when scaling to a larger number of systems.

read the caption

Table 1: Benchmarking the efficiency of Newton Informed Neural Operator. Computational Time Comparison for Solving 500 and 5000 Initial Conditions.

In-depth insights#

Newton’s Method Fusion#

The concept of “Newton’s Method Fusion” in the context of solving nonlinear partial differential equations (PDEs) suggests a hybrid approach that intelligently combines the strengths of classical Newton’s method with the power of modern machine learning techniques. Newton’s method, known for its rapid convergence near a solution, is often computationally expensive and struggles with ill-posed problems or those featuring multiple solutions. Machine learning methods, conversely, may not guarantee convergence but can efficiently learn complex mappings. A fusion strategy would likely involve training a neural network to approximate the Newton iteration mapping or the solution of the linearized system at each Newton step. This fusion could dramatically reduce computational cost, allowing faster solutions for complex PDEs. However, challenges remain. The neural network needs sufficient training data, including examples of multiple solutions if applicable, to generalize accurately. Careful consideration of the loss function is critical to both effectively learning the Newton iteration and ensuring the method converges to the desired solution. Further research should explore novel architectures and training strategies to address these challenges and unlock the full potential of this promising hybrid approach.

DeepONet’s Role#

DeepONet, a type of neural operator, plays a crucial role in approximating the solution of Partial Differential Equations (PDEs). Its strength lies in its ability to learn complex nonlinear mappings between input parameters and solutions, effectively acting as a surrogate for traditional numerical solvers. DeepONet’s architecture allows for efficient handling of high-dimensional input spaces, which is often challenging for conventional methods. While DeepONet excels at operator learning, directly applying it to nonlinear PDEs with multiple solutions might present challenges because its original design assumes a unique solution for each input. The paper proposes a novel approach that integrates DeepONet with a Newton iterative solver to overcome these limitations. The Newton Informed Neural Operator enhances DeepONet’s ability to find multiple solutions by efficiently learning the Newton solver’s iterative steps. This hybrid approach combines the strengths of both operator learning and traditional numerical methods, leading to a more robust and effective method for solving complex nonlinear PDEs. It also reduces the computational burden associated with repeatedly solving linear systems at each iteration of Newton’s method.

Multi-Solution PDEs#

The concept of “Multi-Solution PDEs” highlights a significant challenge in the field of partial differential equations. Traditional numerical methods often struggle with nonlinear PDEs possessing multiple solutions, as they may converge to different solutions depending on initial conditions or solver parameters. This non-uniqueness poses computational difficulties, increasing the expense and complexity of obtaining all potential solutions. The paper addresses this challenge by proposing a novel method that efficiently computes multiple solutions simultaneously using a combination of traditional numerical techniques like Newton’s method integrated with machine learning approaches. This approach leverages the strengths of both methods, using the Newton method’s iterative nature for solving non-linear equations and utilizing neural networks to efficiently learn the solution space. The result is a more efficient and effective means of tackling the complexity inherent in these systems, paving the way for better exploration of nonlinear phenomena in various scientific fields.

Limited Data Regime#

The concept of a ‘Limited Data Regime’ in the context of solving nonlinear partial differential equations (PDEs) using neural networks is crucial. Traditional methods often falter due to computational cost and ill-posedness. Neural networks offer a potential solution, but usually require vast amounts of training data, making them impractical in many real-world scenarios where data is scarce. A limited data regime highlights the need for methods which are data-efficient. This necessitates either innovative network architectures that effectively leverage existing data points or the incorporation of prior knowledge, such as physics-informed methods, to guide the learning process. The effectiveness of these approaches depends on the inherent complexity of the PDE. For simpler PDEs, fewer data points may suffice, whereas more complex scenarios, like those with multiple solutions, necessitate more sophisticated techniques, possibly involving the integration of traditional numerical solvers to provide robust, data-efficient learning. Successfully navigating the challenges of limited data regimes is key to the wider applicability of neural network-based PDE solvers.

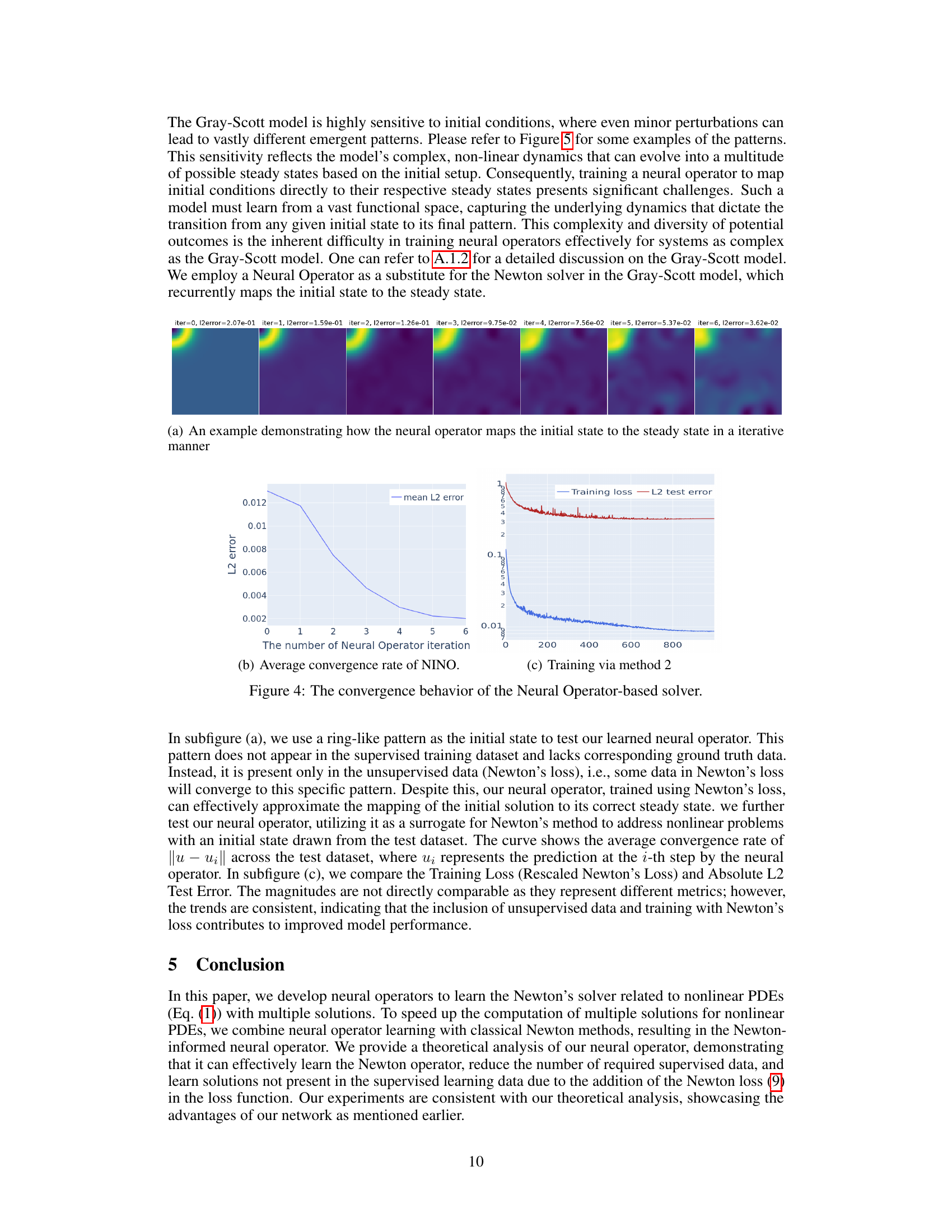

Gray-Scott Dynamics#

The Gray-Scott model, a reaction-diffusion system, presents a fascinating case study for exploring complex pattern formation. Its sensitivity to initial conditions, creating a diverse range of steady states, makes it challenging but rewarding to analyze. The model’s nonlinearity leads to multiple stable solutions, highlighting a significant departure from linear systems. This characteristic makes it an ideal candidate for testing numerical methods designed to handle multiple solutions, particularly machine learning approaches. The model’s relative simplicity belies a rich dynamical behavior, allowing researchers to investigate the interplay between local interactions and global patterns. This interplay makes the Gray-Scott model a valuable tool in understanding various phenomena from biological morphogenesis to chemical oscillations. The challenge of capturing its diverse solutions in a computational context highlights the need for advanced techniques, such as the Newton Informed Neural Operator presented in the paper, which effectively learns the Newton’s method’s nonlinear mapping. By integrating traditional numerical techniques with neural networks, this approach addresses the time-consuming nature of solving nonlinear systems iteratively and provides a powerful methodology for efficiently computing multiple solutions in complex systems like the Gray-Scott model.

More visual insights#

More on figures

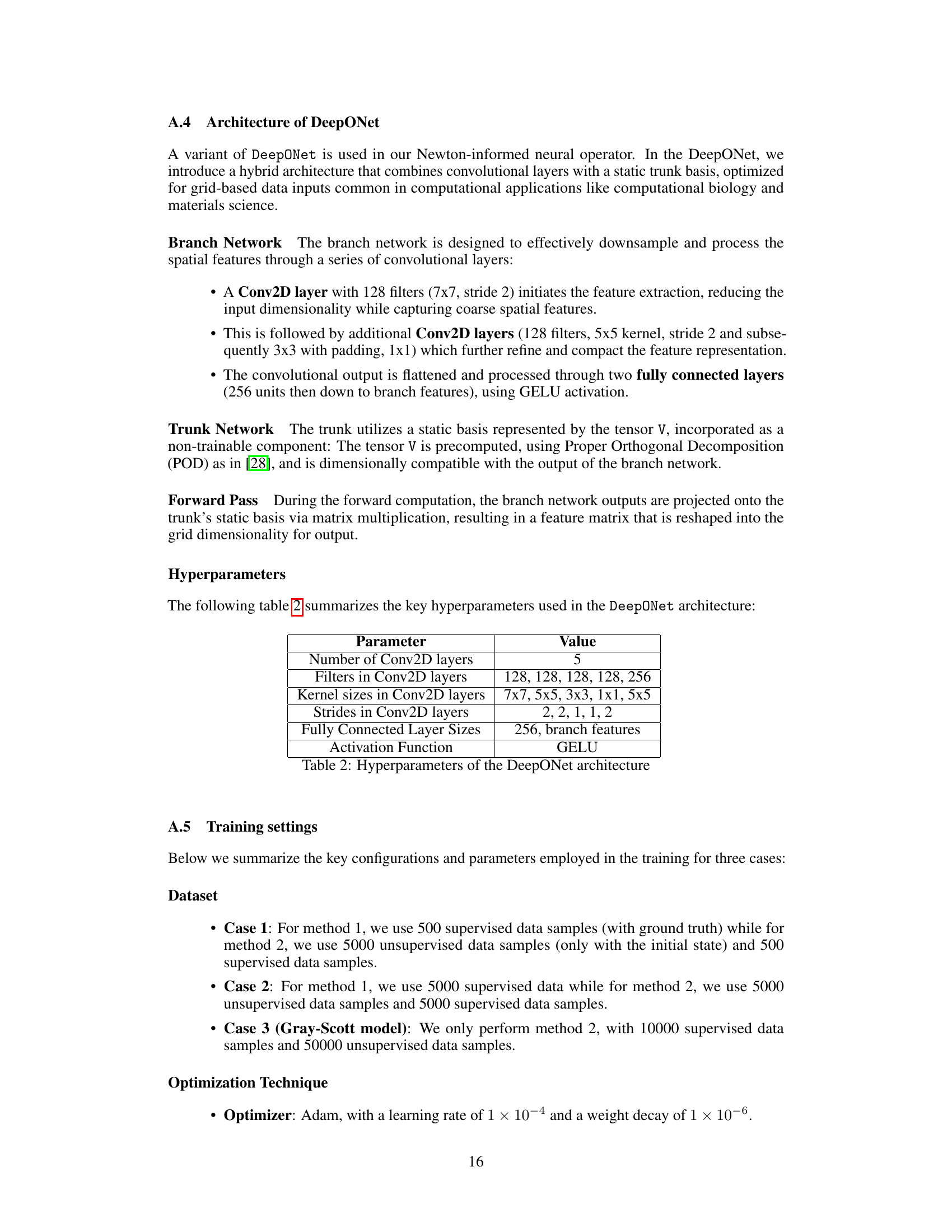

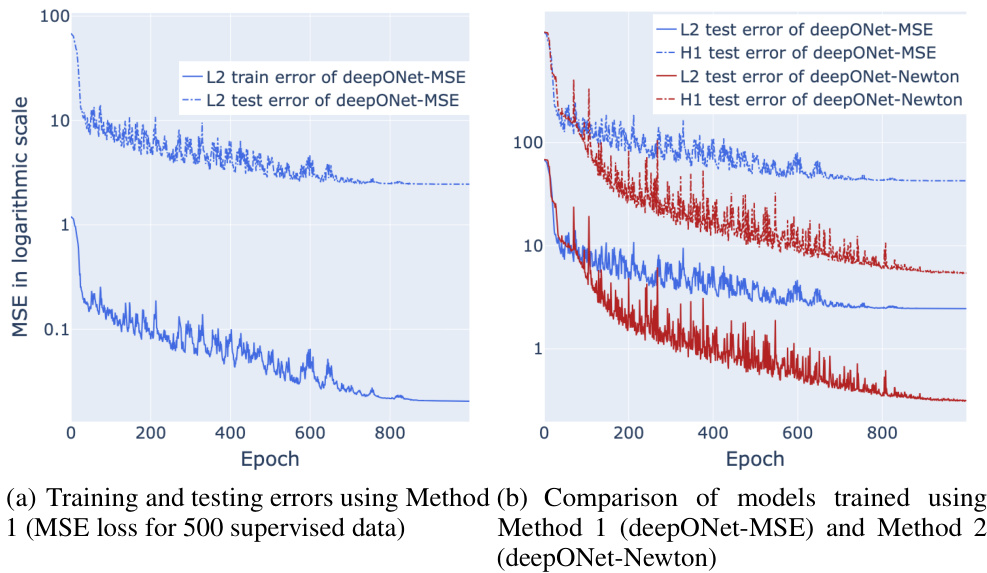

🔼 This figure shows the training and testing performance comparison of two different methods for training the DeepONet model to solve a convex problem. Method 1 uses only Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss with 500 supervised data samples, while Method 2 integrates MSE loss with Newton’s loss, incorporating 5000 unsupervised data samples. The results demonstrate that Method 2, which leverages Newton’s loss and additional unsupervised data, achieves significantly better generalization, with lower L2 and H1 test errors, than Method 1. This illustrates the advantage of using Newton’s method for improved accuracy and generalization in solving nonlinear PDEs.

read the caption

Figure 2: Training and testing performance of DeepONet under different conditions.

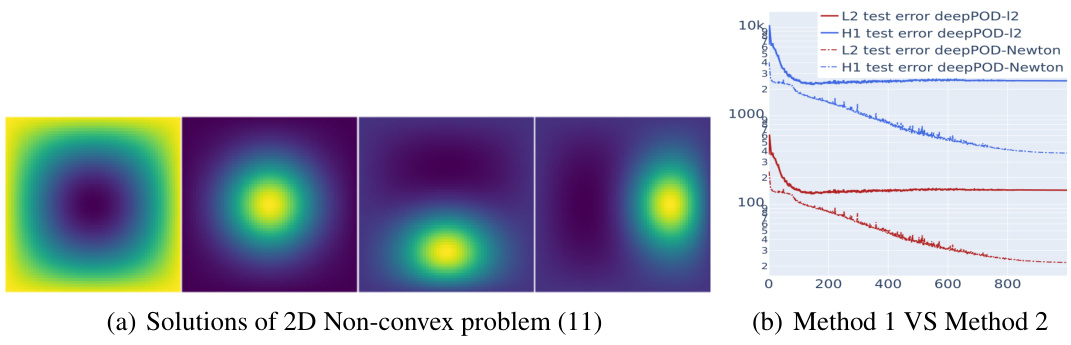

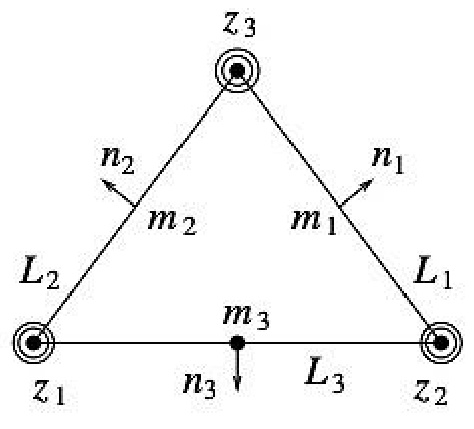

🔼 This figure shows the solutions of the 2D Non-convex problem (11) and the training/testing performance comparison between two different training methods: Method 1 (MSE loss only) and Method 2 (MSE loss + Newton’s loss). Method 2 demonstrates significantly better generalization ability and lower testing errors (L2 and H1) compared to Method 1, highlighting the effectiveness of incorporating Newton’s loss in training the neural network.

read the caption

Figure 3: Solutions of 2D Non-convex problem (11)

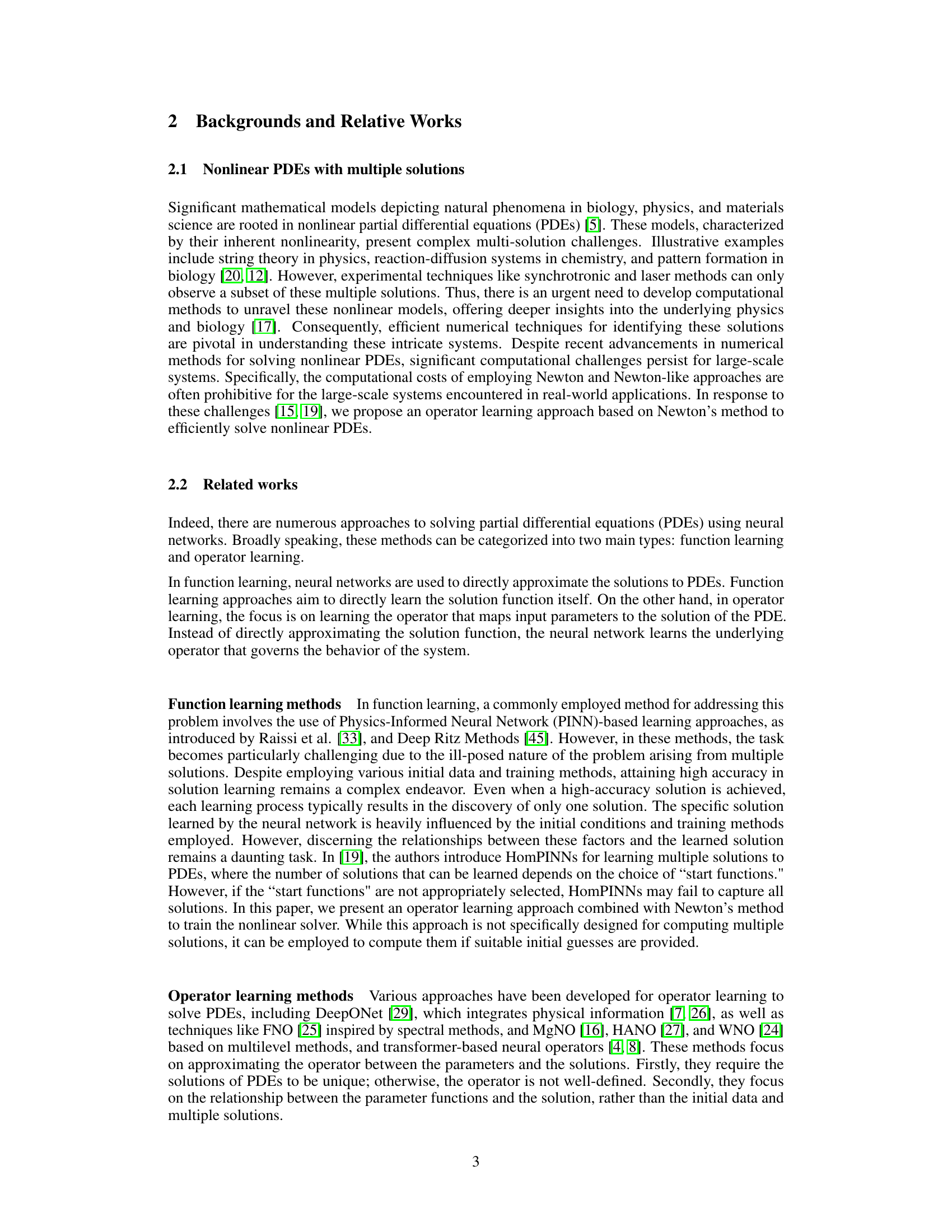

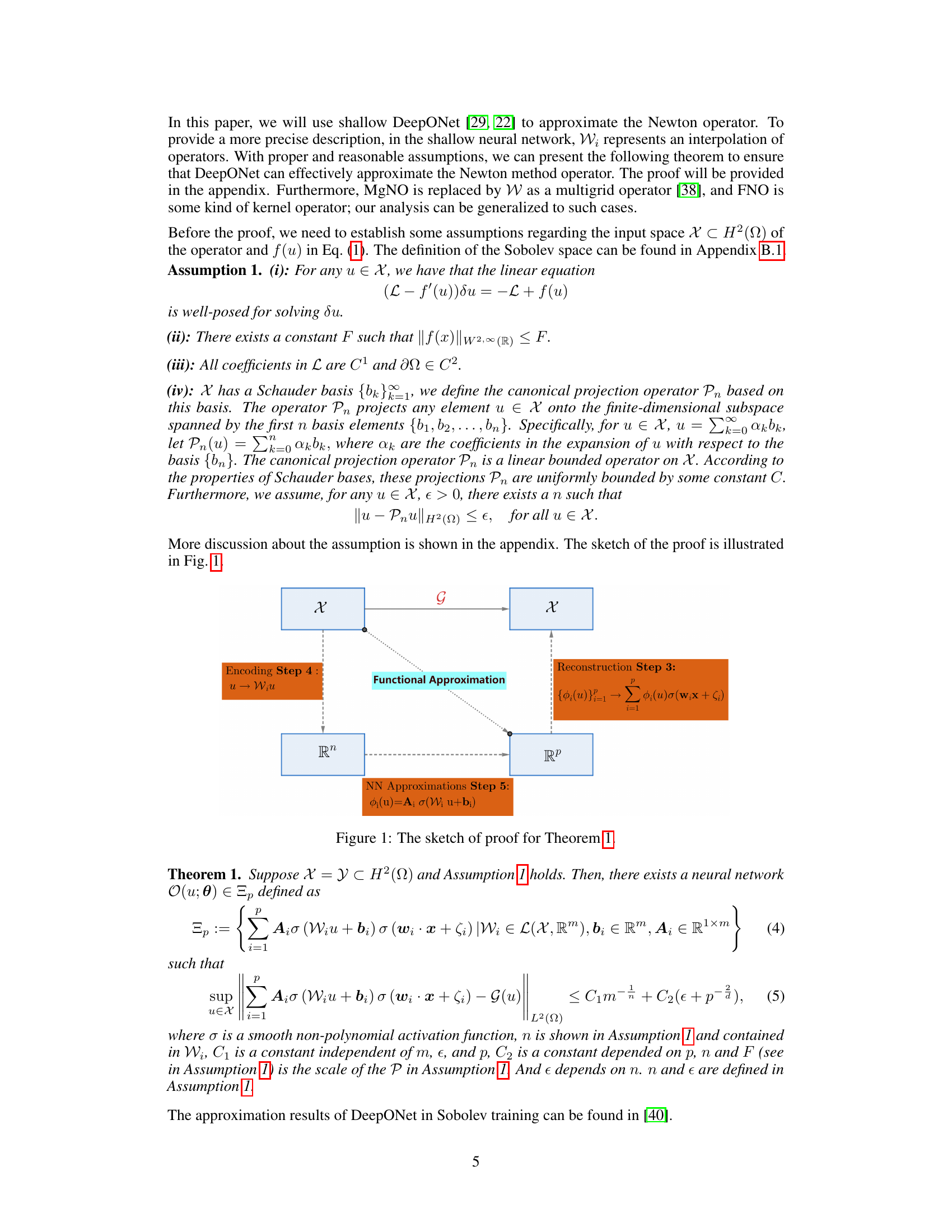

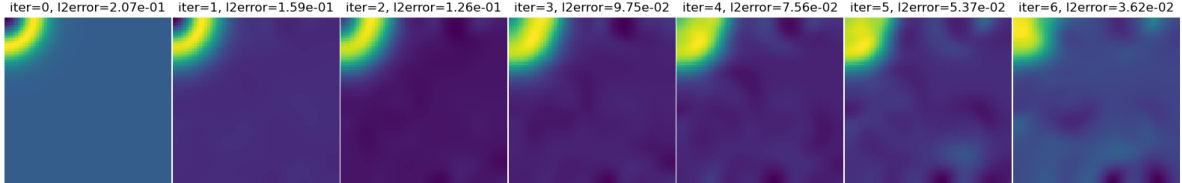

🔼 This figure demonstrates the convergence behavior of the Neural Operator-based solver. Subfigure (a) shows an example of how the neural operator iteratively maps an initial state to a steady state. Subfigure (b) illustrates the average convergence rate of the L2 error during the iterative process. Subfigure (c) presents the training loss and test error over epochs, indicating that unsupervised data and training with Newton’s loss contribute to improved model performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: The convergence behavior of the Neural Operator-based solver.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the convergence behavior of the neural operator-based solver for the Gray-Scott model. Subfigure (a) shows an example of how the neural operator iteratively maps an initial state (a ring-like pattern not present in the training data) to its corresponding steady state. Subfigure (b) displays the average convergence rate of the L2 error over a test dataset, highlighting the efficiency of the method. Subfigure (c) presents the training loss and L2 test error during the training process using method 2 (which incorporates both supervised and unsupervised data). This figure visually illustrates the effectiveness of the proposed method in solving the Gray-Scott model, especially when dealing with limited supervised data.

read the caption

Figure 4: The convergence behavior of the Neural Operator-based solver.

🔼 This figure displays various steady-state patterns produced by the Gray-Scott model under different initial conditions. The Gray-Scott model is a reaction-diffusion system known for its sensitivity to initial conditions, resulting in a wide variety of complex patterns. The images showcase the diversity of these patterns, highlighting the model’s complexity and the challenge of predicting its behavior with only a limited amount of initial data. These patterns illustrate the range of steady-state solutions obtainable by varying initial conditions.

read the caption

Figure 5: Examples of steady states of the Gray Scott model

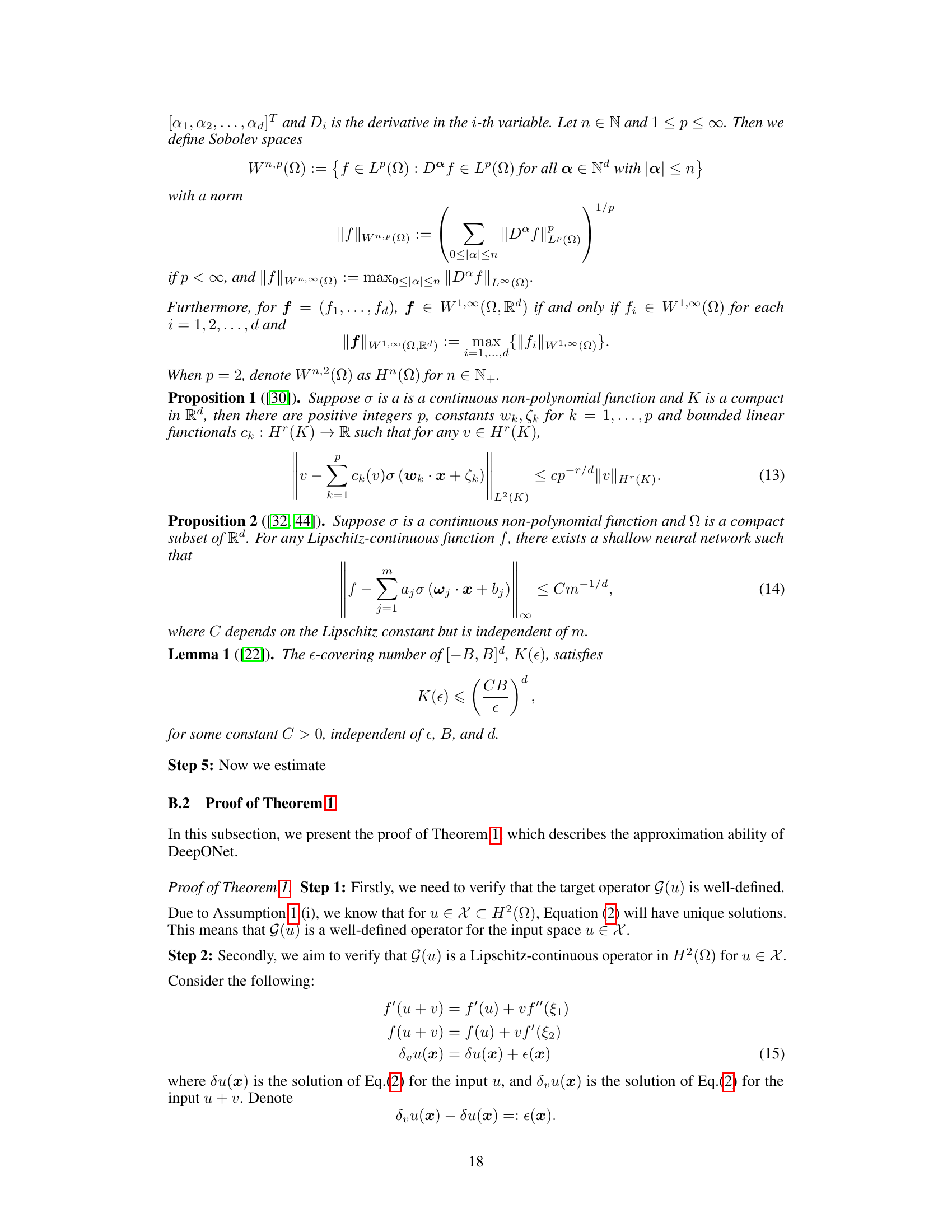

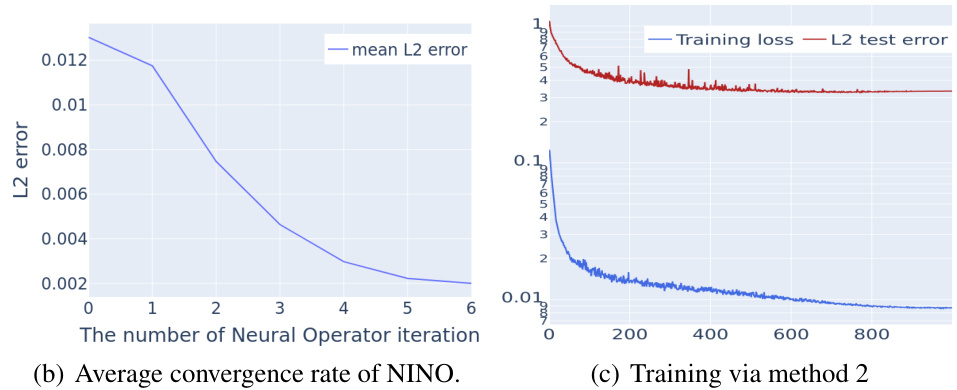

🔼 This figure illustrates the Argyris finite element method for approximating functions and their derivatives. It shows a triangular element with nodes at its vertices (z1, z2, z3) and midpoints (m1, m2, m3). The inner and outer circles at each node represent evaluations of the function and its derivatives, respectively. The arrows indicate the evaluation of normal derivatives at the midpoints. This method provides a high-order approximation of the function by incorporating multiple degrees of freedom at each node. This is used as an example of the embedding operator P in assumption 1 (iv).

read the caption

Figure 7: Argyris method

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the computational time required to solve 500 and 5000 linear systems using Newton’s method and the proposed Newton Informed Neural Operator (NINO). It highlights the significant efficiency gain of NINO, especially when solving a larger number of systems, demonstrating its ability to efficiently handle high-dimensional problems.

read the caption

Table 1: Benchmarking the efficiency of Newton Informed Neural Operator. Computational Time Comparison for Solving 500 and 5000 Initial Conditions.

🔼 This table compares the computational time taken by the traditional Newton’s method and the proposed Newton Informed Neural Operator (NINO) for solving 500 and 5000 linear systems. It demonstrates that NINO is significantly more efficient, especially when dealing with a larger number of systems, highlighting its advantage for handling multiple solutions in nonlinear PDEs.

read the caption

Table 1: Benchmarking the efficiency of Newton Informed Neural Operator. Computational Time Comparison for Solving 500 and 5000 Initial Conditions.

Full paper#