TL;DR#

Characterizing the computational power of transformer neural networks is a significant challenge in AI research. Prior work has focused on establishing upper or lower bounds on the types of problems transformers can solve, but few studies have achieved exact characterizations. This paper addresses this gap for a specific class of transformers. These transformers use a simplified attention mechanism called “hard attention”, meaning they focus on a single position, and “masking”, where each position only considers inputs to its left or right.

This paper introduces a key technique: Boolean RASP, a programming language that compiles directly into the masked hard-attention transformers. It rigorously proves that these transformers recognize exactly the “star-free languages”, a well-studied class of formal languages. This equivalence is established using Boolean RASP as an intermediary between the transformers and another equivalent formalism, Linear Temporal Logic (LTL). The results are extended to include various factors such as position embeddings, masking, and depth, demonstrating precisely how these affect the transformers’ capabilities.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on the expressiveness of transformers, especially those focusing on formal language theory. It bridges the gap between theoretical models and practical applications, offering a clearer understanding of what transformer architectures can achieve and paving the way for the design of more powerful and efficient models.

Visual Insights#

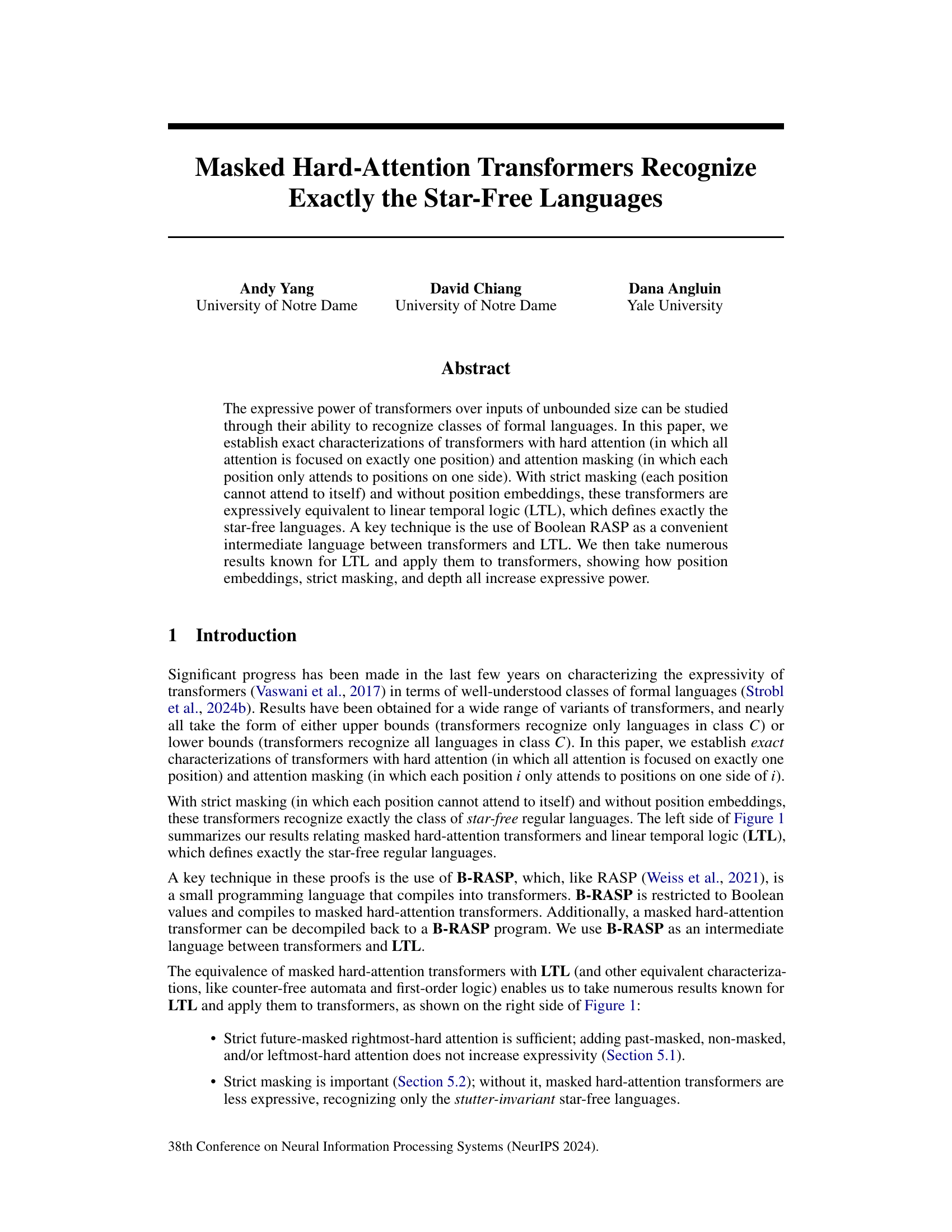

🔼 This figure summarizes the main results of the paper, showing the relationships between different classes of formal languages and their corresponding masked hard-attention transformer models. It illustrates how various factors, such as the type of masking (strict future, strict future and past, non-strict masking), the presence or absence of position embeddings, and the depth of the transformer, affect the expressive power of the model. The relationships are represented using arrows: one-way arrows indicate strict inclusion (a smaller class is strictly contained within a larger class), and two-way arrows indicate equivalence (two classes have the same expressive power). The figure helps to visually understand the hierarchy of expressiveness established in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of results in this paper. One-way arrows denote strict inclusion; two-way arrows denote equivalence. PE = position embedding.

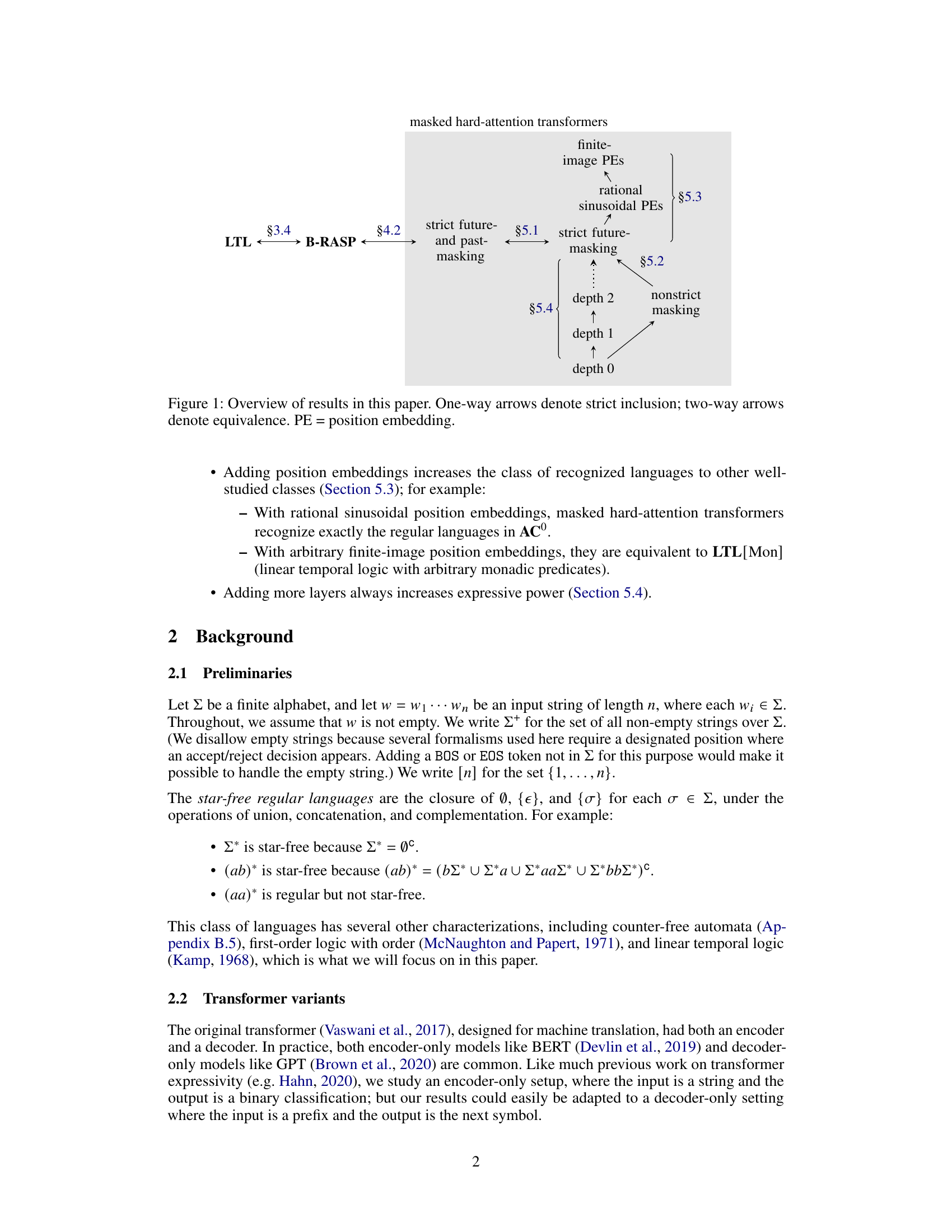

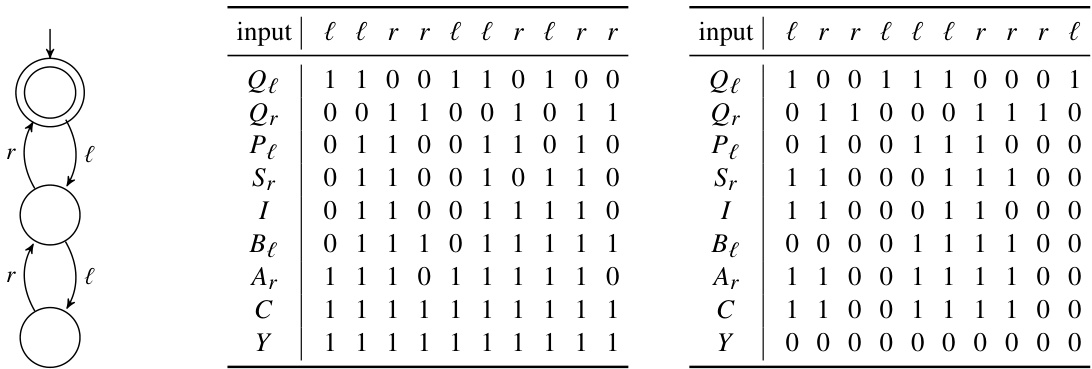

🔼 This figure presents example Boolean vectors computed by a B-RASP program for the Dyck-1 language (depth 2), denoted as L1,2. The left column shows a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA) that recognizes L1,2, illustrating the language’s structure. The middle column details the Boolean vectors when the input string ’llrrllrlrr’ (which is in L1,2) is processed, while the right column shows the Boolean vectors for the input string ’lrrlllrrrl’ (which is not in L1,2). These vectors demonstrate the intermediate computations within the B-RASP program, ultimately leading to a decision of acceptance or rejection based on the final Boolean vector ‘Y’.

read the caption

Figure 2: Examples related to L1,2 (Dyck-1 of depth 2). The left bracket is l and the right bracket is r.

In-depth insights#

Transformer Expressivity#

Research on transformer expressivity explores the boundaries of what these powerful models can represent and compute. A key aspect is understanding the relationship between transformer architecture (e.g., attention mechanisms, depth, masking) and the classes of formal languages they can recognize. Exact characterizations, pinpointing the precise computational power of specific transformer variants, are particularly valuable. This involves rigorous proofs establishing equivalences between transformers and well-understood computational models like linear temporal logic (LTL) or finite automata. Such research highlights the impact of architectural choices, such as strict versus non-strict masking or the inclusion of position embeddings, on the expressive capacity of transformers. Furthermore, investigations into the interaction between depth and expressivity reveal whether adding more layers genuinely enhances computational capabilities, going beyond what simpler configurations can achieve. This line of inquiry is crucial for guiding the design of more efficient and powerful transformer architectures for various applications.

Masked Hard Attention#

Masked hard attention, a mechanism combining the principles of masking and hard attention, presents a unique approach to transformer architecture. Masking restricts the attention scope, preventing certain positions from attending to others, often for reasons of causality or to maintain sequential order. Hard attention focuses each attention head entirely on a single position, unlike soft attention which distributes attention weights. This combination creates a model with a limited, deterministic attention flow, making it easier to analyze and understand than standard soft attention transformers. The constrained attention makes theoretical analysis simpler, potentially enabling precise characterizations of expressiveness and computational complexity. However, this determinism also limits its capacity for capturing intricate patterns and relationships compared to its soft attention counterparts which could be a major drawback. It might be less effective on tasks requiring flexible, nuanced attention patterns. The trade-off between analytical tractability and practical applicability is a central consideration for evaluating masked hard attention’s efficacy.

B-RASP Equivalence#

The B-RASP equivalence section of the research paper is crucial as it bridges the gap between theoretical models and practical implementations. It establishes a formal connection between B-RASP (a restricted Boolean version of the RASP programming language), a masked hard-attention transformer model. This is significant because B-RASP is easier to analyze and reason about than the complex transformer architecture. Demonstrating equivalence means that any computation achievable in one formalism is also achievable in the other. This allows the researchers to leverage existing results from the well-studied field of formal language theory to obtain new insights into the capabilities and limitations of the transformer models. Specifically, it allows them to characterize exactly the class of languages recognizable by masked hard-attention transformers. This is a powerful tool for analyzing the power and limitations of transformer models, paving the way for further research and advancements in the field.

LTL and Star-Free#

The connection between Linear Temporal Logic (LTL) and star-free languages is a cornerstone of automata theory, and this paper leverages this to analyze transformer expressivity. LTL’s ability to express properties of computation over time aligns well with the sequential nature of transformer processing. The equivalence between LTL and star-free languages means that transformers, under certain conditions (hard attention, strict masking, no positional embeddings), can only recognize the same class of languages. This result precisely defines the boundaries of transformer expressivity in this constrained setting. However, the paper also explores how relaxing these constraints (allowing position embeddings, non-strict masking, or increasing depth) extends the expressiveness beyond star-free languages, enriching our understanding of transformers’ capabilities and limitations.

Depth and Embeddings#

The interplay between depth and embeddings in transformer models is crucial for their expressive power. Increasing depth, generally, leads to a richer representational capacity, allowing the model to learn more complex patterns in sequential data. However, simply adding layers isn’t sufficient; the model’s architecture and training process must also accommodate the added complexity. Positional embeddings, providing information about token order, are critical for many tasks. Different embedding types, like sinusoidal or learned embeddings, have distinct effects on the model’s capabilities. Learned embeddings can capture intricate relationships between tokens, but risk overfitting if not properly regularized. Sinusoidal embeddings offer a more computationally efficient alternative, but may not be as expressive for all tasks. The optimal combination of depth and embedding type depends on several factors, including the task’s complexity, the dataset’s properties, and the available computational resources. Furthermore, the interaction between depth and embeddings can be non-trivial; the benefits of additional depth may be diminished if the embeddings are not expressive enough or vice versa. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding requires careful consideration of both elements and their synergistic effects.

More visual insights#

More on figures

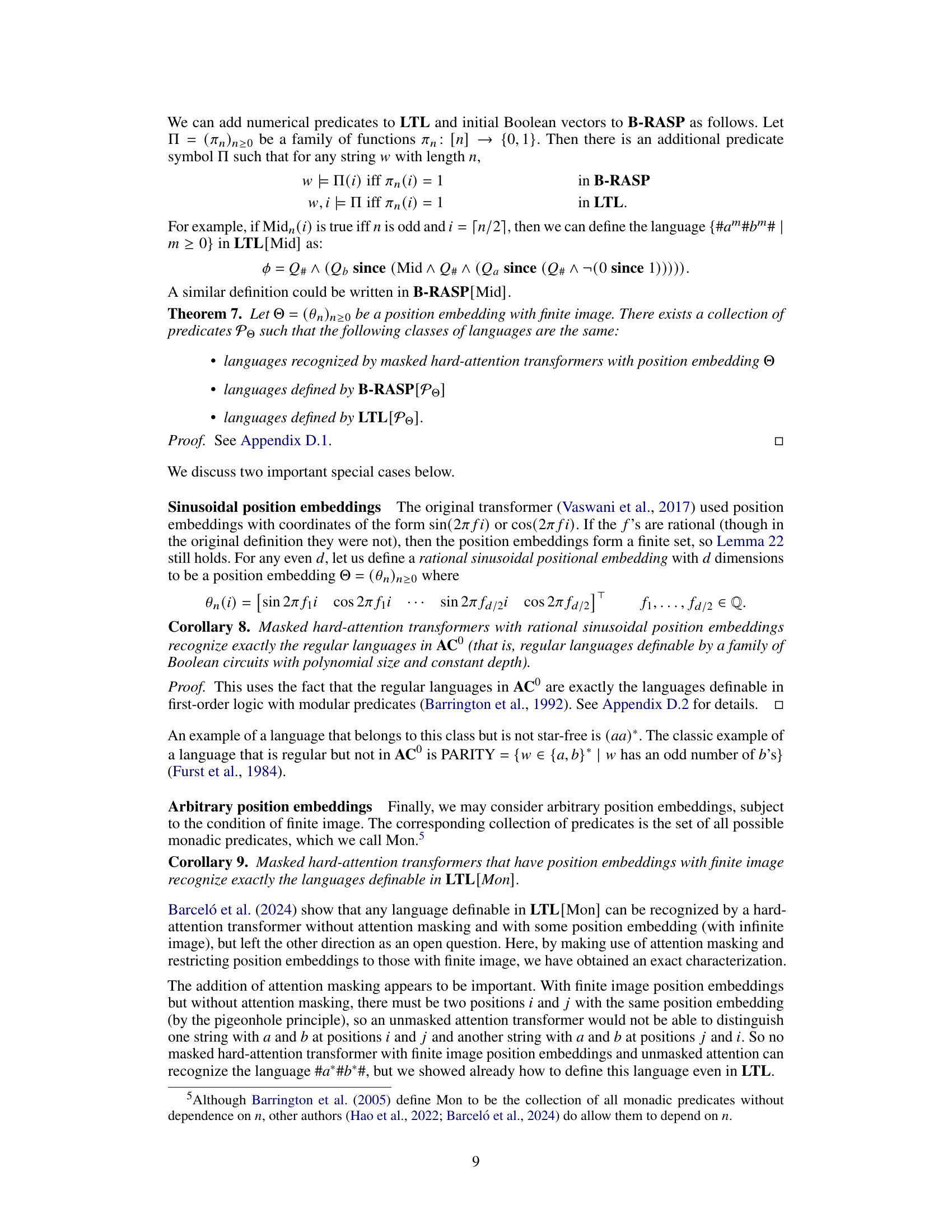

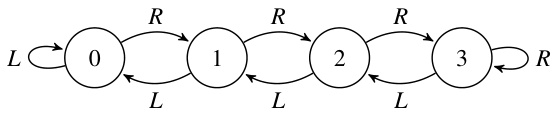

🔼 This figure shows an example of a deterministic finite automaton (DFA) and how it can be decomposed into a cascade product of identity-reset automata. The DFA (A3) is represented visually, showing its states (0-3) and transitions labeled with ‘L’ (left) or ‘R’ (right). The cascade decomposition breaks down the DFA into smaller, simpler automata, which are easier to work with. The final part of the figure depicts the ‘global automaton’ of this cascade product, showing the relationship between the combined states and the original DFA.

read the caption

Figure 3: Example automaton and its cascade decomposition.

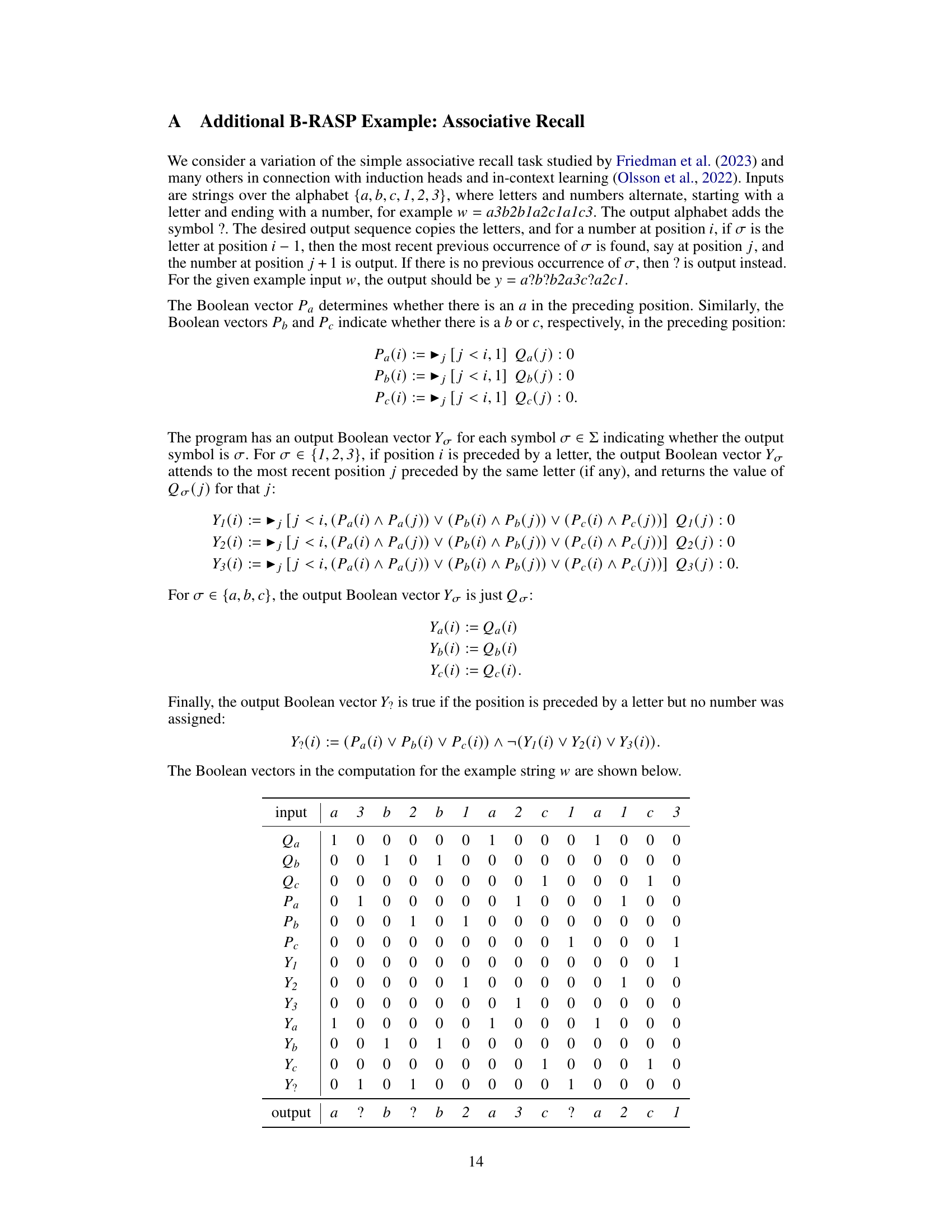

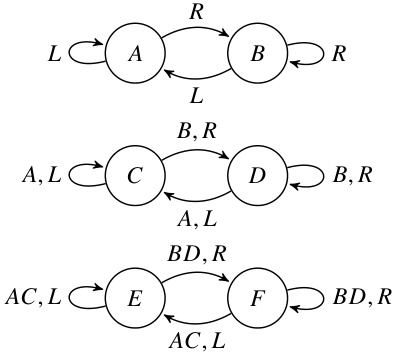

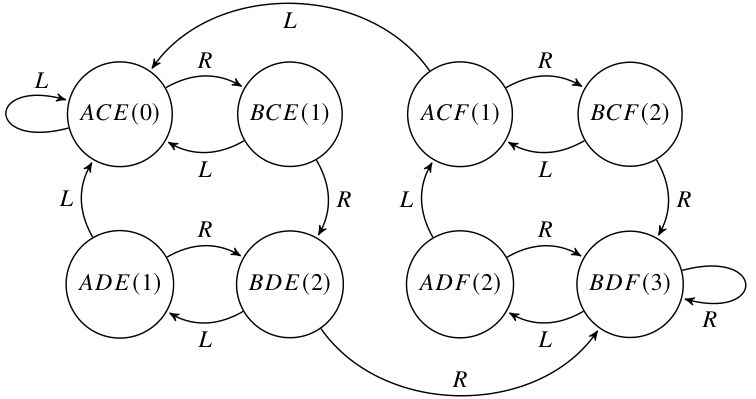

🔼 This figure shows an example of an automaton (a finite state machine) and how it can be decomposed into a cascade of simpler automata. The top panel (a) shows a simple automaton with two states. The middle panel (b) displays a cascade decomposition of the automaton, where the cascade is composed of three simpler automata. Each of these simpler automata has the property that for any input, the transformation of states is either a permutation (each state maps to a different state) or a constant function (all states map to the same state). The bottom panel (c) depicts the global automaton resulting from this cascade decomposition, showing its relationship to the original automaton. This decomposition is a key part of the proof that shows the equivalence between Boolean RASP and linear temporal logic for recognizing star-free languages.

read the caption

Figure 3: Example automaton and its cascade decomposition.

🔼 This figure illustrates an example of an automaton (A3) and its decomposition into a cascade product of identity-reset automata. Part (a) shows the original automaton A3 with states representing the number of left or right brackets currently unmatched. Part (b) shows the cascade decomposition, where each automaton is an identity-reset automaton, meaning it either keeps the state the same or changes to a new state based on the input symbol. The transitions in (b) are simplified by showing only non-self-loop transitions for clarity. Part (c) depicts the global automaton resulting from the cascade product in part (b), showing the combined states and transitions of all the identity-reset automata in a larger automaton. The state number corresponds to the corresponding state in A3. This decomposition is key in explaining how the authors can reduce the complexity of proving the star-free language recognition ability of transformers by breaking them down into more basic manageable units.

read the caption

Figure 3: Example automaton and its cascade decomposition.

Full paper#