TL;DR#

Availability attacks aim to make trained models unusable by poisoning training data. While effective against supervised learning, existing attacks often fail against contrastive learning (CL), which is increasingly popular due to its ability to learn from unlabeled data. This creates a significant vulnerability, as attackers could bypass existing defenses by using CL after supervised learning fails. This research paper highlights the limitation of existing attacks and emphasizes the need for more robust data protection methods that can withstand both SL and CL approaches.

This work proposes two new availability attacks: Augmented Unlearnable Examples (AUE) and Augmented Adversarial Poisoning (AAP). These attacks leverage a novel technique of employing contrastive-like data augmentations within supervised learning frameworks to simultaneously achieve unlearnability against both SL and CL. The authors demonstrate that their methods outperform state-of-the-art attacks in terms of effectiveness and efficiency, providing superior worst-case unlearnability across various algorithms and datasets. The results showcase a promising approach to improving the security of machine learning models, especially in scenarios where sensitive data must be protected from unauthorized use.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in data security and machine learning. It directly addresses the vulnerability of contrastive learning models to availability attacks, a significant gap in current research. By introducing novel attack methods, it motivates further research in developing robust defenses against these attacks, directly contributing to safer and more secure machine learning practices. Its efficient methods offer practical implications for real-world data protection scenarios, which significantly enhances its relevance.

Visual Insights#

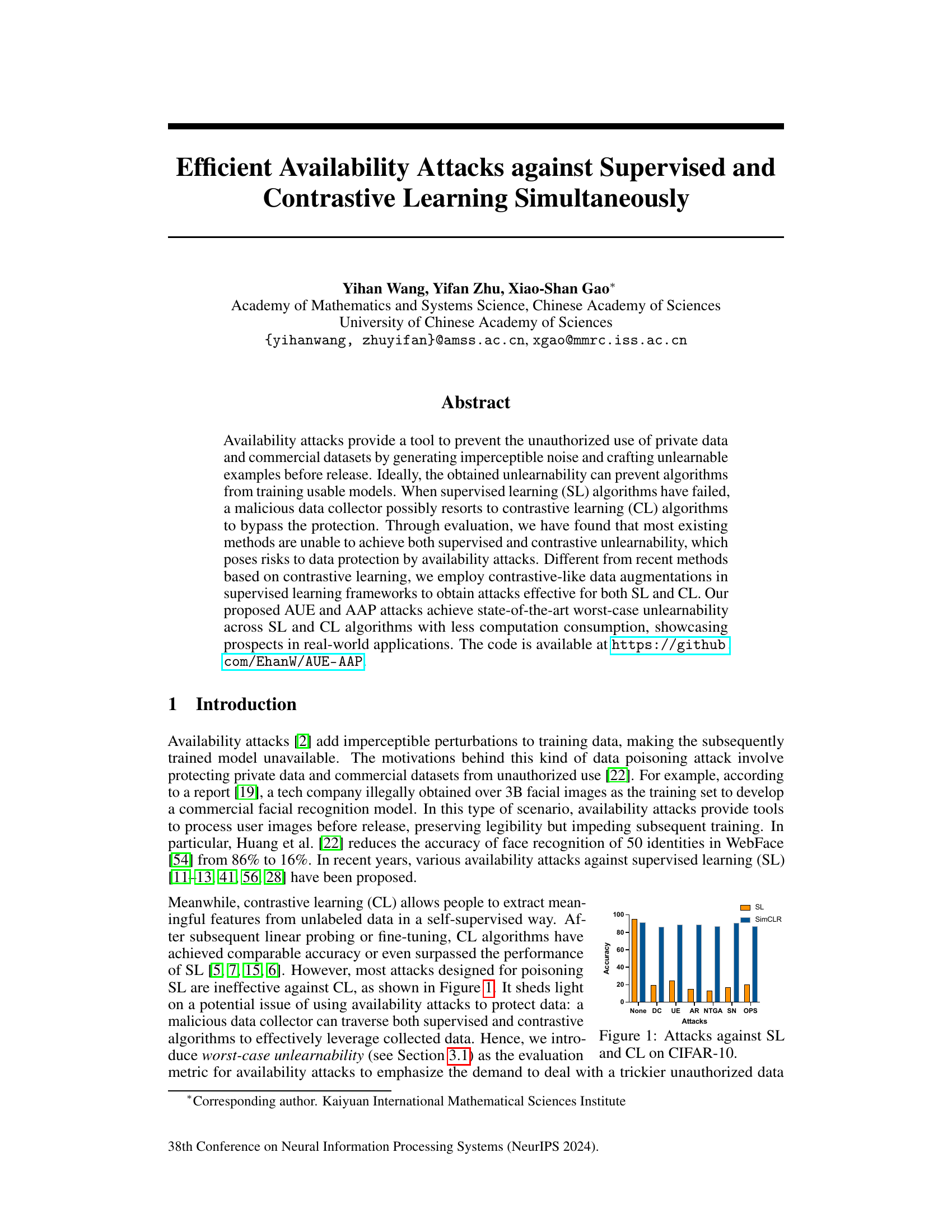

🔼 This figure shows the performance of various attacks against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The x-axis represents different types of attacks (None, DC, UE, AR, NTGA, SN, OPS), while the y-axis shows the accuracy. The bars are grouped by learning method (SL and SimCLR, a contrastive learning method). It illustrates that most attacks are effective against SL but not against CL, highlighting a potential weakness of using only SL-based availability attacks for data protection.

read the caption

Figure 1: Attacks against SL and CL on CIFAR-10.

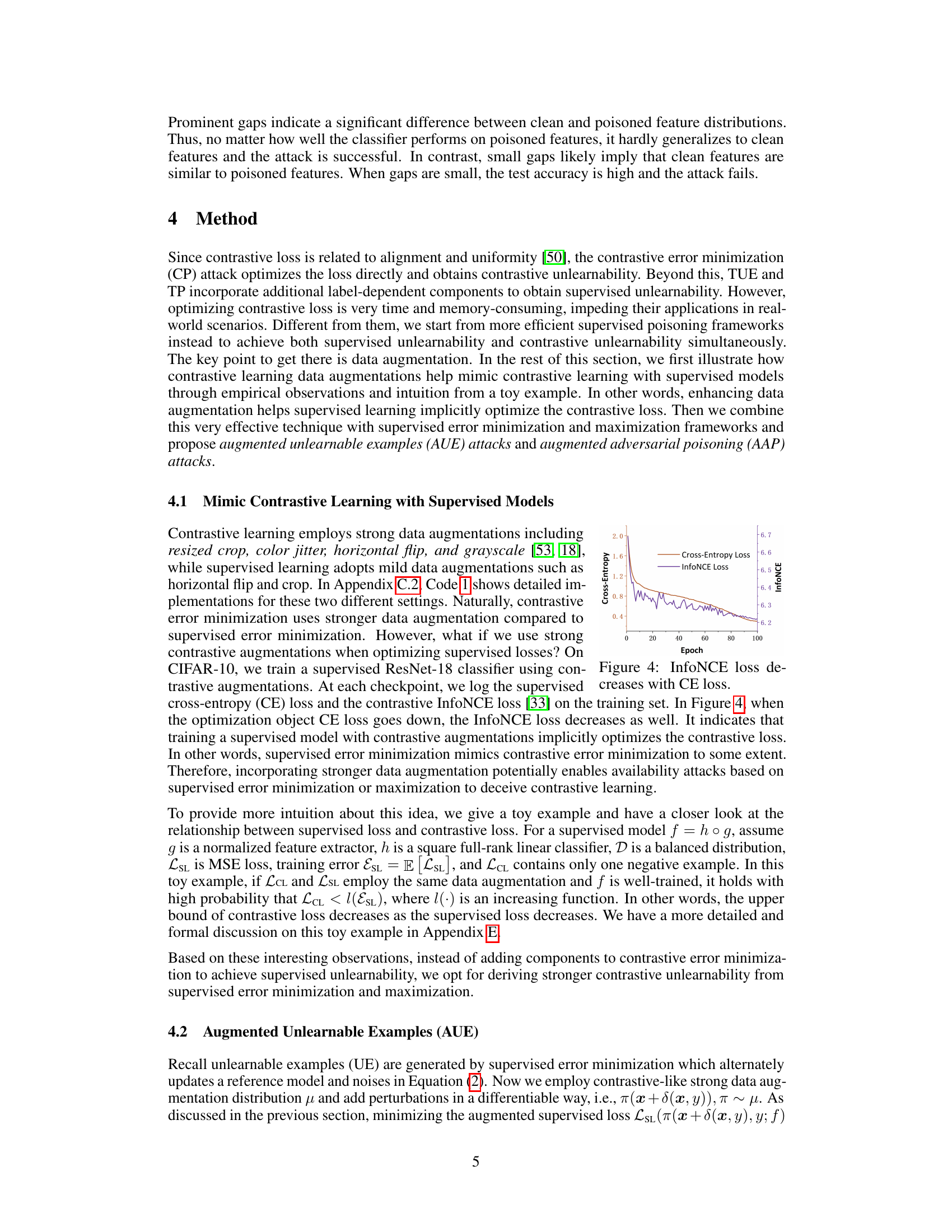

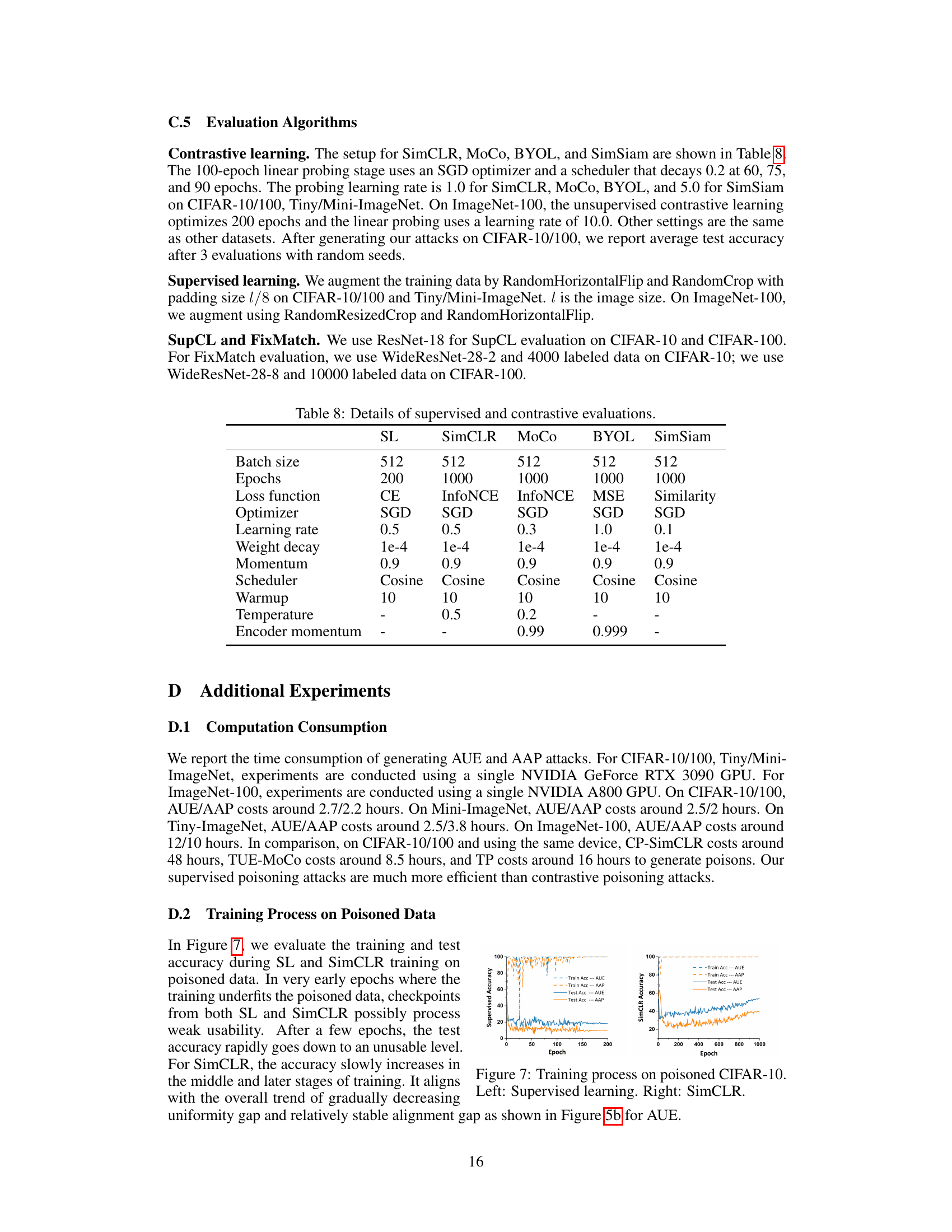

🔼 This table presents the results of various availability attacks against the SimCLR algorithm on the CIFAR-10 dataset. For each attack, it shows the alignment gap, uniformity gap, and test accuracy. The alignment and uniformity gaps measure the difference in feature distributions between the clean and poisoned datasets. The table is organized to highlight the differences in effectiveness between attacks based on contrastive error minimization and other methods. Bold values highlight significant contrastive unlearnability.

read the caption

Table 1: Alignment gap, uniformity gap, and test accuracy(%) of poisoned SimCLR [5] models. Attacks are grouped according to whether they are based on contrastive error minimization. Bold fonts emphasize prominent contrastive unlearnability values.

In-depth insights#

Contrastive Attacks#

Contrastive attacks represent a significant advancement in the field of adversarial machine learning, focusing on the vulnerabilities of contrastive learning models. These attacks leverage the inherent nature of contrastive learning, which learns by comparing similarities and dissimilarities between data points. By carefully crafting adversarial examples that manipulate these comparisons, contrastive attacks aim to disrupt the model’s ability to learn meaningful representations. This is a departure from traditional attacks targeting supervised learning, which often focus on misclassifying individual data points. The effectiveness of contrastive attacks stems from their ability to introduce subtle perturbations that significantly impact the learned feature space, potentially leading to catastrophic failure in downstream tasks even if individual data points remain seemingly unaffected. The development and analysis of such attacks is crucial for enhancing the robustness and security of contrastive learning models, particularly in applications handling sensitive data where maintaining the integrity of learned representations is paramount. Further research is needed to explore the various types of contrastive attacks, their specific vulnerabilities, and the development of effective defense mechanisms. This includes investigating attack transferability across different model architectures and datasets, as well as developing more sophisticated metrics for evaluating the effectiveness of these attacks.

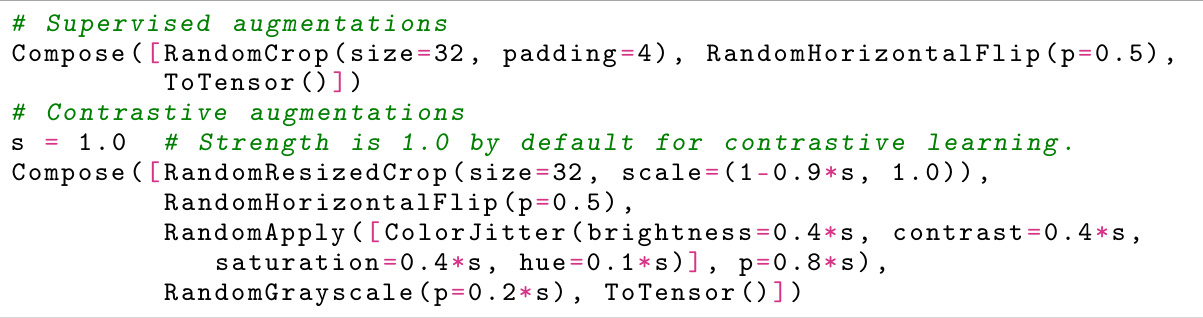

AUE/AAP Methods#

The AUE (Augmented Unlearnable Examples) and AAP (Augmented Adversarial Poisoning) methods represent a novel approach to crafting availability attacks against both supervised and contrastive learning models. Instead of directly targeting the contrastive loss function, as many previous methods do, AUE and AAP leverage the power of strong data augmentations within a supervised learning framework. This clever strategy mimics the effect of contrastive learning, making the generated perturbations effective against both types of algorithms. AUE focuses on error minimization, creating imperceptible noise that fools both supervised and contrastive models, whereas AAP employs error maximization, generating adversarial examples that are similarly disruptive. The key innovation lies in the combined use of supervised learning frameworks with contrastive-like augmentations, resulting in more efficient attacks compared to prior contrastive-learning-based approaches. This efficiency is a significant advantage, making the approach suitable for large datasets and real-world applications where computational resources are a concern. The effectiveness across multiple datasets and different algorithms showcases its potential as a robust defense mechanism against malicious data exploitation.

Worst-Case U-bility#

The concept of “Worst-Case Unlearnability” in the context of availability attacks on machine learning models is a crucial contribution to the field of data security. It directly addresses a weakness in traditional evaluation metrics that focus on average-case performance. By defining unlearnability as the minimum performance achievable across a range of supervised and unsupervised learning algorithms (considering both SL and CL), this metric offers a more robust and realistic assessment of an attack’s effectiveness. This is particularly relevant in adversarial scenarios where a malicious actor could strategically choose the learning method most resistant to a particular attack. Focusing on the worst-case scenario, rather than the average, provides a significantly more conservative and trustworthy evaluation that better reflects the true security implications. The adoption of this metric will drive future research toward the development of more resilient data protection strategies against sophisticated attacks that exploit multiple learning paradigms.

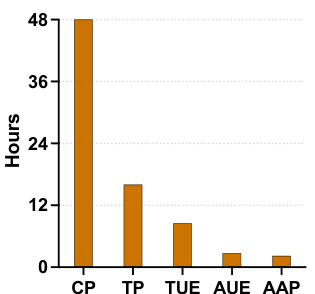

Poisoning Efficiency#

Poisoning efficiency in the context of availability attacks focuses on the trade-off between attack effectiveness and computational cost. Highly effective attacks that significantly degrade model performance are desired, but these often come at a high computational cost, hindering their practical application, especially when dealing with large datasets. The goal is to find attacks that can achieve sufficient unlearnability with minimal resource consumption (time, memory, and processing power). Efficient poisoning methods aim to generate imperceptible perturbations that are highly effective at breaking both supervised and contrastive learning algorithms while remaining computationally feasible. This includes minimizing the time needed to generate the poisoned data, reducing memory usage during attack generation, and ensuring the overall process is scalable for very large datasets. The evaluation of poisoning efficiency therefore goes beyond simple accuracy metrics to include a comprehensive assessment of the required computational resources and the scalability of the attack strategy. Optimal attacks will achieve the best balance between unlearnability and efficiency, allowing for availability attacks to be practically deployed in real-world scenarios safeguarding sensitive data.

Future Directions#

Future research should prioritize enhancing the robustness of availability attacks against adaptive defenses, exploring techniques that can overcome adversarial training and other mitigation strategies. A deeper investigation into the generalizability of these attacks across diverse model architectures and datasets is crucial. Furthermore, research should focus on developing more efficient methods for generating perturbations, especially for large-scale datasets. Finally, a comprehensive analysis of the trade-offs between different types of availability attacks (supervised vs. contrastive) is necessary, to guide the development of optimal protection methods against both. The ethical implications of availability attacks, including considerations for data privacy and fairness, should be thoroughly examined.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed method of generating poisoning attacks against both supervised and contrastive learning. It shows a comparison between existing CL-based poisoning methods (top) and the proposed SL-based methods (bottom). The key difference is the use of stronger contrastive augmentations in the SL-based approach. The left side illustrates the attack generation process, while the right side demonstrates the training process on the poisoned data, showing how the attacks render models unusable.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of our proposed method. Separated by a vertical dashed line, the left side shows the process of generating the poisoning attack, while the right side depicts the training process on the poisoned dataset. On the generation side, above the horizontal dashed line are the existing methods based on contrastive error minimization, while below the dashed line are our proposed methods based on supervised error minimization/maximization (the blue flow). Our attack leverages the stronger contrastive augmentations to obtain effectiveness against both supervised learning and contrastive learning algorithms. Label information is involved in both our method and CL-based methods.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of the proposed AUE and AAP attacks against various supervised and contrastive learning algorithms on the ImageNet-100 dataset. It compares the accuracy achieved by clean data against the accuracy after applying the attacks, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed methods in reducing the accuracy of both supervised and contrastive learning models.

read the caption

Figure 3: Attack performance of our methods on ImageNet-100.

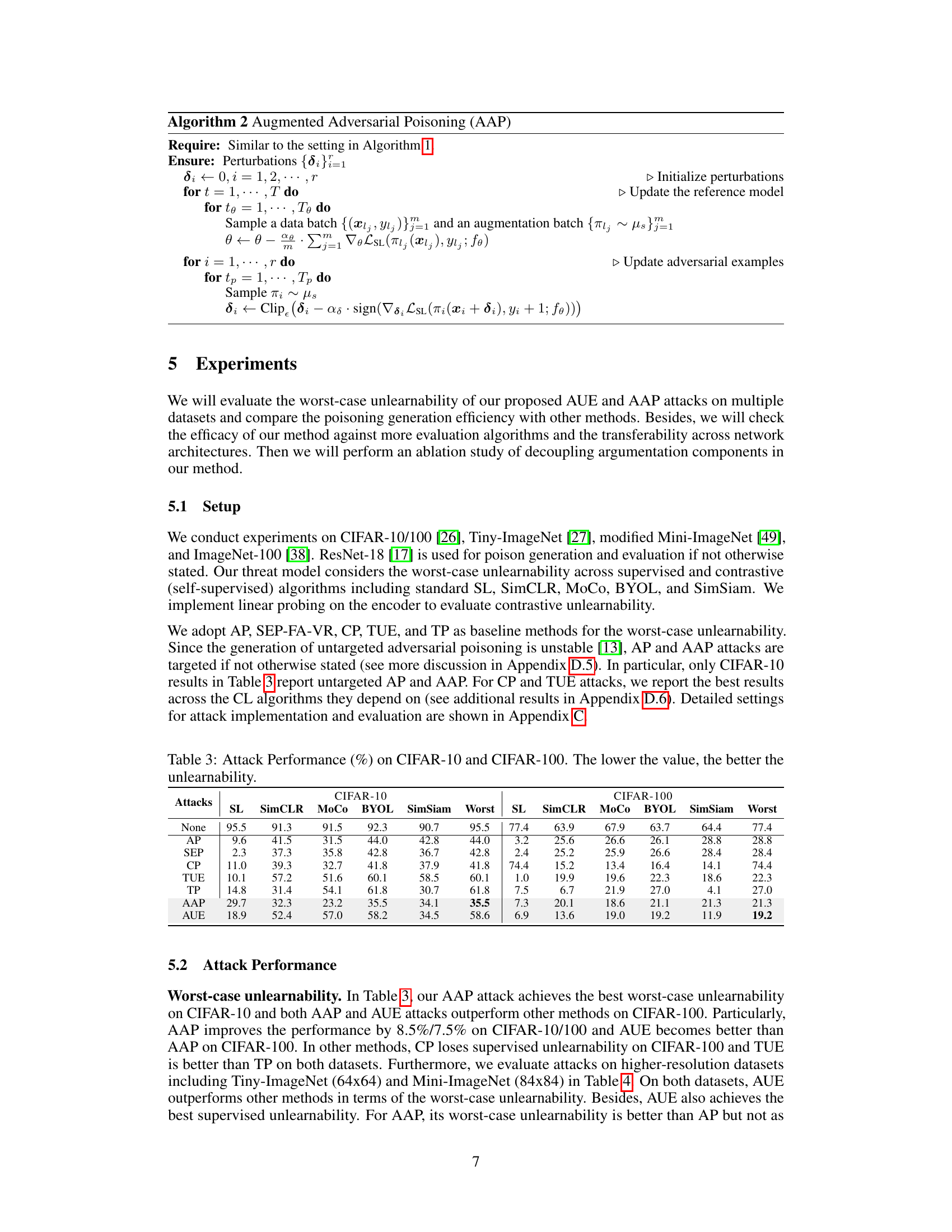

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between cross-entropy loss (CE loss) and InfoNCE loss during the training of a supervised ResNet-18 classifier on CIFAR-10 using contrastive augmentations. The plot demonstrates that as the cross-entropy loss decreases (indicating improved model performance), the InfoNCE loss also decreases. This observation suggests that using strong contrastive augmentations in a supervised learning framework can implicitly optimize the contrastive loss, mimicking the behavior of contrastive learning.

read the caption

Figure 4: InfoNCE loss decreases with CE loss.

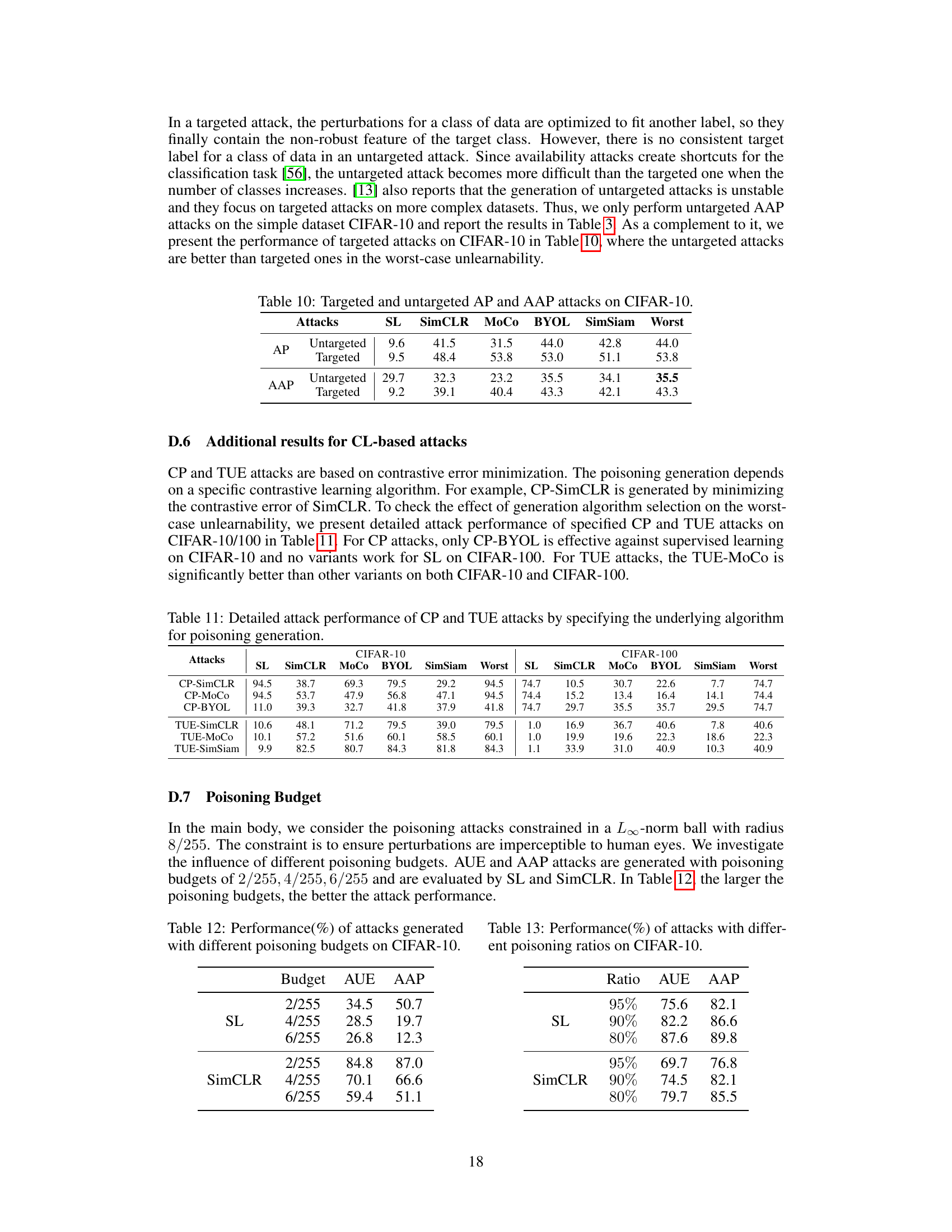

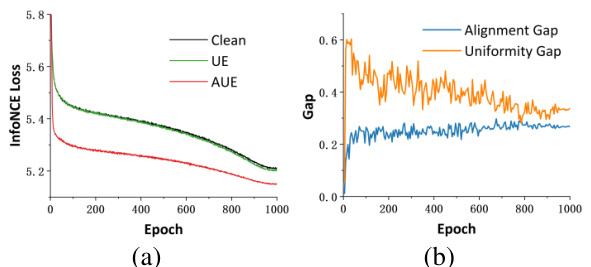

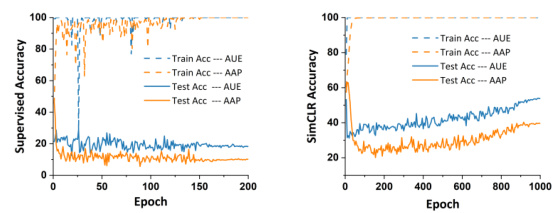

🔼 This figure shows two subfigures. Subfigure (a) presents the contrastive losses during SimCLR training when using the UE and AUE attacks on CIFAR-10. Subfigure (b) illustrates the alignment and uniformity gaps observed during the SimCLR training on a CIFAR-10 dataset that was poisoned using the AUE attack. The comparison of contrastive losses and the alignment/uniformity gap between UE and AUE attacks highlights the effectiveness of AUE in deceiving contrastive learning algorithms by significantly reducing the contrastive loss and increasing the gap between the poisoned and clean data.

read the caption

Figure 5: (a) Contrastive losses during SimCLR training under UE and AUE attacks. (b) Alignment and uniformity gaps during the SimCLR training on CIFAR-10 poisoned by our AUE attack.

🔼 This bar chart displays the time required for generating poisoning attacks using different methods. The methods are CP, TP, TUE, AUE, and AAP. The chart shows that AUE and AAP are significantly faster than CP, TP, and TUE.

read the caption

Figure 6: Time consumption of poisoning generation.

🔼 The figure shows the attack performance of different availability attacks against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It demonstrates that most existing attacks are ineffective against both SL and CL simultaneously, highlighting a potential vulnerability in data protection strategies.

read the caption

Figure 1: Attacks against SL and CL on CIFAR-10.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of various attacks against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It illustrates that many existing attacks are effective against SL but fail against CL, highlighting a vulnerability in the use of availability attacks for data protection. The graph shows the accuracy remaining after different attacks are applied, comparing the results for SL and CL models.

read the caption

Figure 1: Attacks against SL and CL on CIFAR-10.

🔼 The figure shows the performance comparison of various attacks against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It illustrates that most existing attacks are ineffective against both SL and CL simultaneously, highlighting a security risk in data protection using availability attacks. The x-axis represents different types of attacks, and the y-axis represents the accuracy. We can see that the clean data achieves a high accuracy in both SL and CL, while most attacks only slightly decrease the accuracy of SL. Only a few attacks, such as AP and SEP, show a substantial reduction in the accuracy of both SL and CL.

read the caption

Figure 1: Attacks against SL and CL on CIFAR-10.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of various availability attacks against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The x-axis represents different attacks, while the y-axis shows the accuracy. It highlights that most existing attacks are ineffective against CL, even when SL algorithms have failed, indicating a vulnerability in data protection using only SL-based availability attacks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Attacks against SL and CL on CIFAR-10.

🔼 This figure shows the performance of various availability attacks against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It highlights that most existing attacks are ineffective against both SL and CL simultaneously, demonstrating the need for new approaches that consider both learning paradigms. The attacks are compared against a baseline of no attack, showing a significant reduction in accuracy for several attacks.

read the caption

Figure 1: Attacks against SL and CL on CIFAR-10.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different attacks against the SimCLR algorithm on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. It shows the percentage drop in accuracy achieved by different attacks, including the basic UE and AP attacks and the proposed AUE and AAP attacks. The negative values indicate a decrease in accuracy, representing the success of the attacks in making the models less accurate. The table highlights the improved performance of the proposed AUE and AAP attacks compared to the baseline methods.

read the caption

Table 2: Accuracy drop(%) of SimCLR caused by basic attacks and our methods.

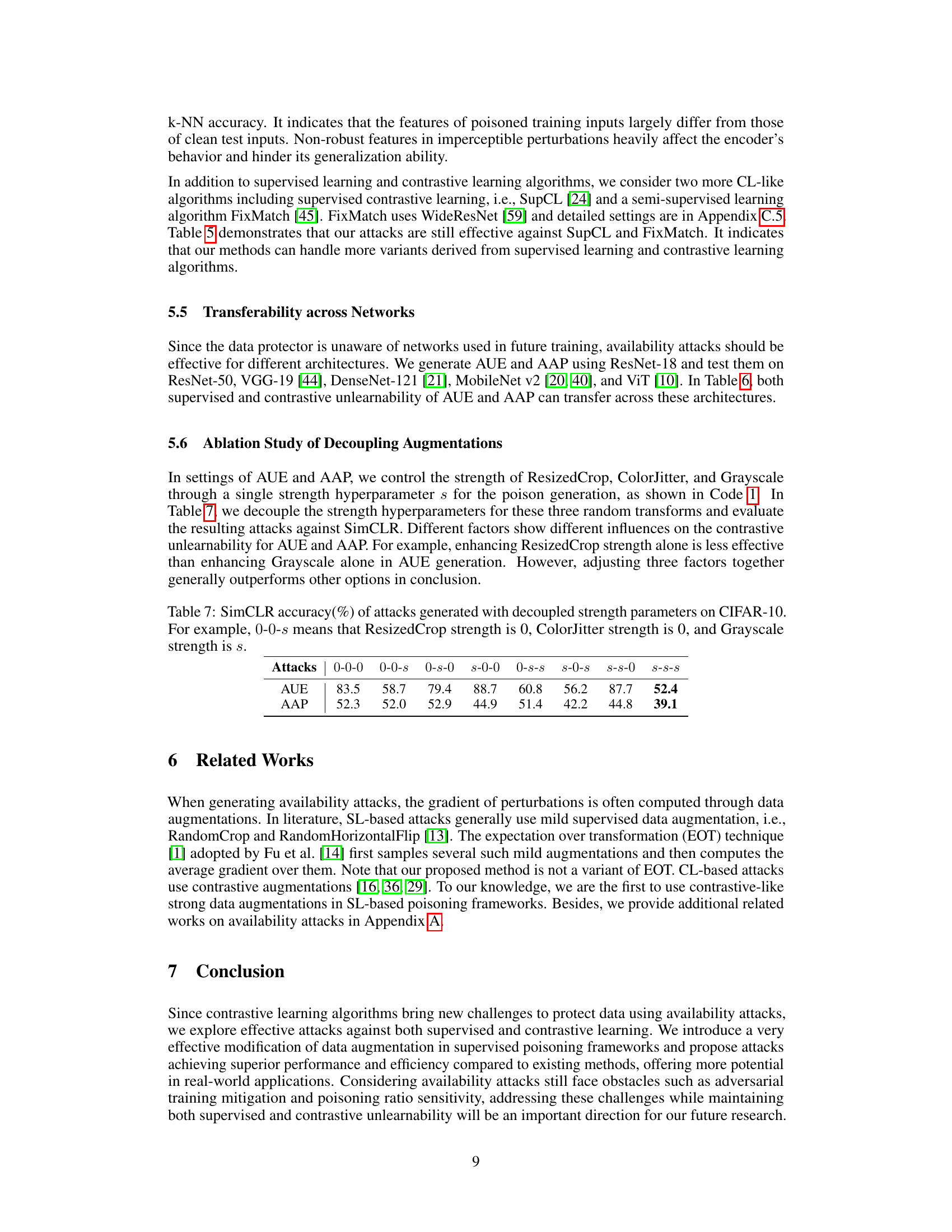

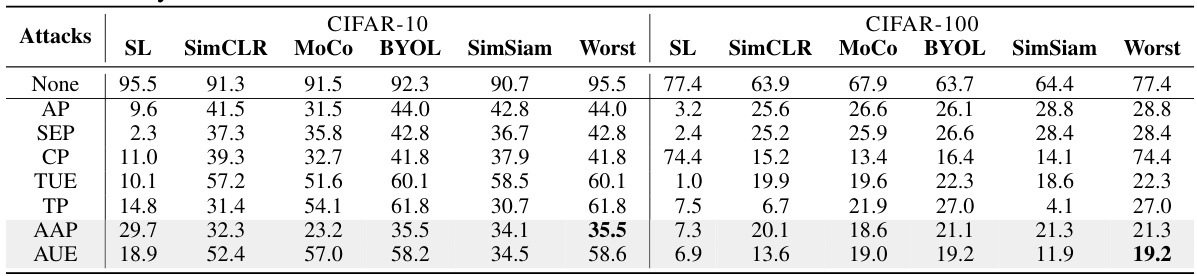

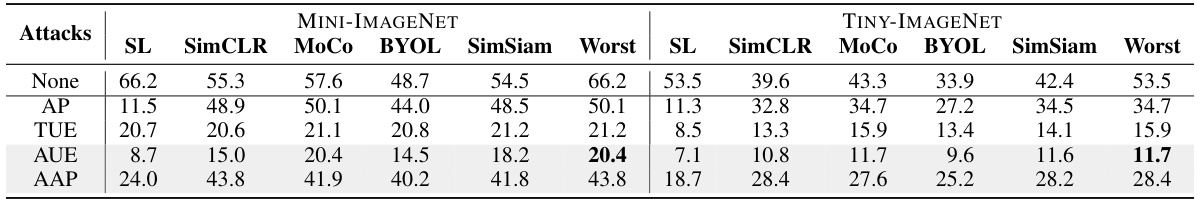

🔼 This table presents the results of various availability attacks on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets, evaluating their effectiveness against both supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms. The lower the accuracy percentage, the better the performance of the attack in rendering the model unusable. It compares several attack methods, including the authors’ proposed AUE and AAP, against baselines. It shows the worst-case unlearnability across different algorithms for each attack, highlighting the effectiveness of the methods in achieving both supervised and contrastive unlearnability simultaneously.

read the caption

Table 3: Attack Performance (%) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100. The lower the value, the better the unlearnability.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different availability attacks (None, AP, SEP, CP, TUE, TP, AAP, AUE) against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning algorithms (SimCLR, MoCo, BYOL, SimSiam) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The ‘Worst’ column indicates the worst performance across all algorithms for each attack. Lower values in each column indicate better unlearnability, meaning that the attack is more effective at making the model unusable. The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed AUE and AAP attacks.

read the caption

Table 3: Attack Performance (%) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100. The lower the value, the better the unlearnability.

🔼 This table presents the performance of various availability attacks on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. It shows the accuracy achieved by supervised learning (SL) and four contrastive learning algorithms (SimCLR, MoCo, BYOL, SimSiam) after training on data poisoned by different attacks (None, AP, SEP, CP, TUE, TP, AAP, AUE). The lower the accuracy, the better the attack’s performance in rendering the data unusable for training. The ‘Worst’ column shows the worst-case accuracy across all five learning algorithms for each attack.

read the caption

Table 3: Attack Performance (%) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100. The lower the value, the better the unlearnability.

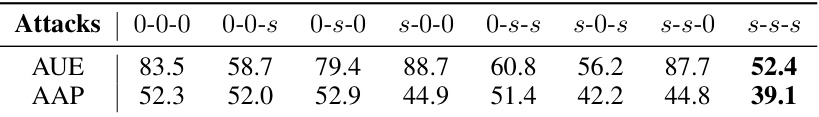

🔼 This table shows the SimCLR accuracy (%) resulting from attacks generated with different combinations of ResizedCrop, ColorJitter, and Grayscale augmentation strength. Each combination is represented by a three-number code (e.g., 0-0-s, where 0 indicates no augmentation and s indicates full augmentation strength). The table helps analyze the individual impact of each augmentation type on the effectiveness of the AUE and AAP attacks.

read the caption

Table 7: SimCLR accuracy(%) of attacks generated with decoupled strength parameters on CIFAR-10. For example, 0-0-s means that ResizedCrop strength is 0, ColorJitter strength is 0, and Grayscale strength is s.

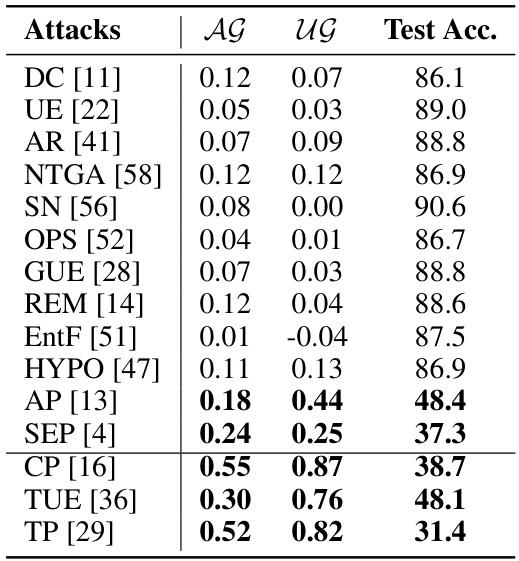

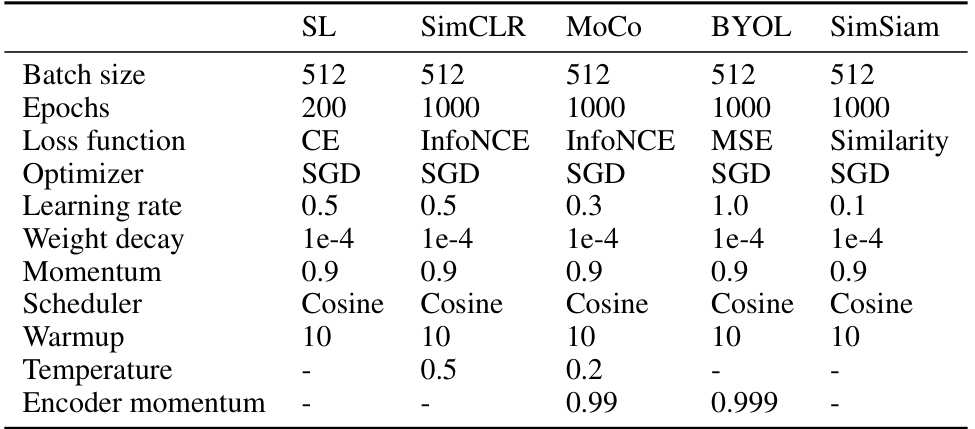

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters used for training the supervised and contrastive learning models in the experiments. It shows the batch size, number of epochs, loss function, optimizer, learning rate, weight decay, momentum, scheduler, warmup period, and temperature (for contrastive learning models). These settings are crucial for reproducibility and understanding the experimental setup. The table provides the details of different settings used for supervised learning and contrastive learning algorithms.

read the caption

Table 8: Details of supervised and contrastive evaluations.

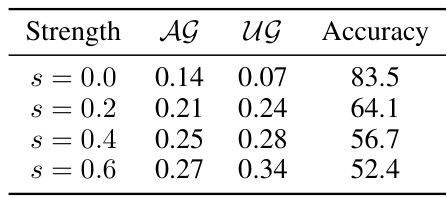

🔼 This table shows the impact of varying augmentation strength (s) on the performance of the Augmented Unlearnable Examples (AUE) attack. It demonstrates how increasing the strength affects the alignment gap (AG), uniformity gap (UG), and the resulting SimCLR accuracy. Higher gaps generally correlate with lower accuracy, indicating a more successful attack.

read the caption

Table 9: Alignment and uniformity gaps of AUE with different strengths.

🔼 This table presents the performance of both targeted and untargeted adversarial poisoning (AP) and augmented adversarial poisoning (AAP) attacks on the CIFAR-10 dataset. It shows the accuracy drop (%) achieved by these attacks against various algorithms, including supervised learning (SL), SimCLR, MoCo, BYOL, and SimSiam. The ‘Worst’ column indicates the worst-case unlearnability across all the algorithms considered, providing a comprehensive evaluation of the attacks’ effectiveness.

read the caption

Table 10: Targeted and untargeted AP and AAP attacks on CIFAR-10.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different availability attacks against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The attacks are compared using the worst-case unlearnability metric, which is calculated as the maximum of the accuracy of supervised and contrastive algorithms. Lower values indicate a more effective attack that leads to lower accuracy of the trained models, thus higher unlearnability. The table shows the effectiveness of various attacks including AP, SEP, CP, TUE, TP, AUE and AAP.

read the caption

Table 3: Attack Performance (%) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100. The lower the value, the better the unlearnability.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different attacks on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The attacks are evaluated using two metrics: SL (Supervised Learning) accuracy and SimCLR (a Contrastive Learning method) accuracy. Lower values indicate better unlearnability, meaning the attacks are more successful in preventing the model from learning effectively. The table allows for a comparison of the effectiveness of various attack methods against both supervised and contrastive learning approaches.

read the caption

Table 3: Attack Performance (%) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100. The lower the value, the better the unlearnability.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different availability attacks against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (SimCLR, MoCo, BYOL, SimSiam) algorithms on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The ‘None’ row indicates the accuracy of clean data. Lower values indicate better attack performance in terms of worst-case unlearnability (meaning the model is less usable). The table shows that the proposed AUE and AAP attacks achieve the best performance compared to other methods (AP, SEP, CP, TUE, TP).

read the caption

Table 3: Attack Performance (%) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100. The lower the value, the better the unlearnability.

🔼 This table presents the performance of different availability attacks (including the proposed AUE and AAP attacks) against supervised learning (SL) and contrastive learning (CL) algorithms on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100 datasets. The lower the percentage, the better the attack’s ability to render the model unusable (i.e., achieve higher unlearnability). The table compares the proposed methods with several existing attacks. It is a key result illustrating the effectiveness of AUE and AAP in achieving state-of-the-art worst-case unlearnability.

read the caption

Table 3: Attack Performance (%) on CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100. The lower the value, the better the unlearnability.

Full paper#