TL;DR#

Large neural networks heavily rely on dense linear layers, which become computationally expensive as model size increases. Previous research focused on a limited set of structured matrices but didn’t fully explore the compute-optimal scaling laws across a broader range of structures and training conditions. This limits their applicability to massive models where training compute is the biggest bottleneck.

This research proposes a unifying framework to search among all linear operators expressible via Einstein summation, encompassing many previously proposed structures, along with novel ones. The authors introduce a continuous parameterization of structured matrices to find the most efficient ones, finding that full-rank structures without parameter sharing provide the best compute scaling laws. A new Mixture-of-Experts architecture, BTT-MoE, is proposed, demonstrating significant gains in compute efficiency over both dense layers and standard MoE in large language model training.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on large-scale neural networks because it directly addresses the computational bottlenecks of dense linear layers, a major obstacle in training massive models. It introduces a novel approach for optimizing computation efficiency and proposes a new architecture, BTT-MoE, that significantly improves upon existing methods. The findings are relevant to current trends in efficient deep learning and open exciting new avenues for research into structured linear layers and mixture-of-experts architectures.

Visual Insights#

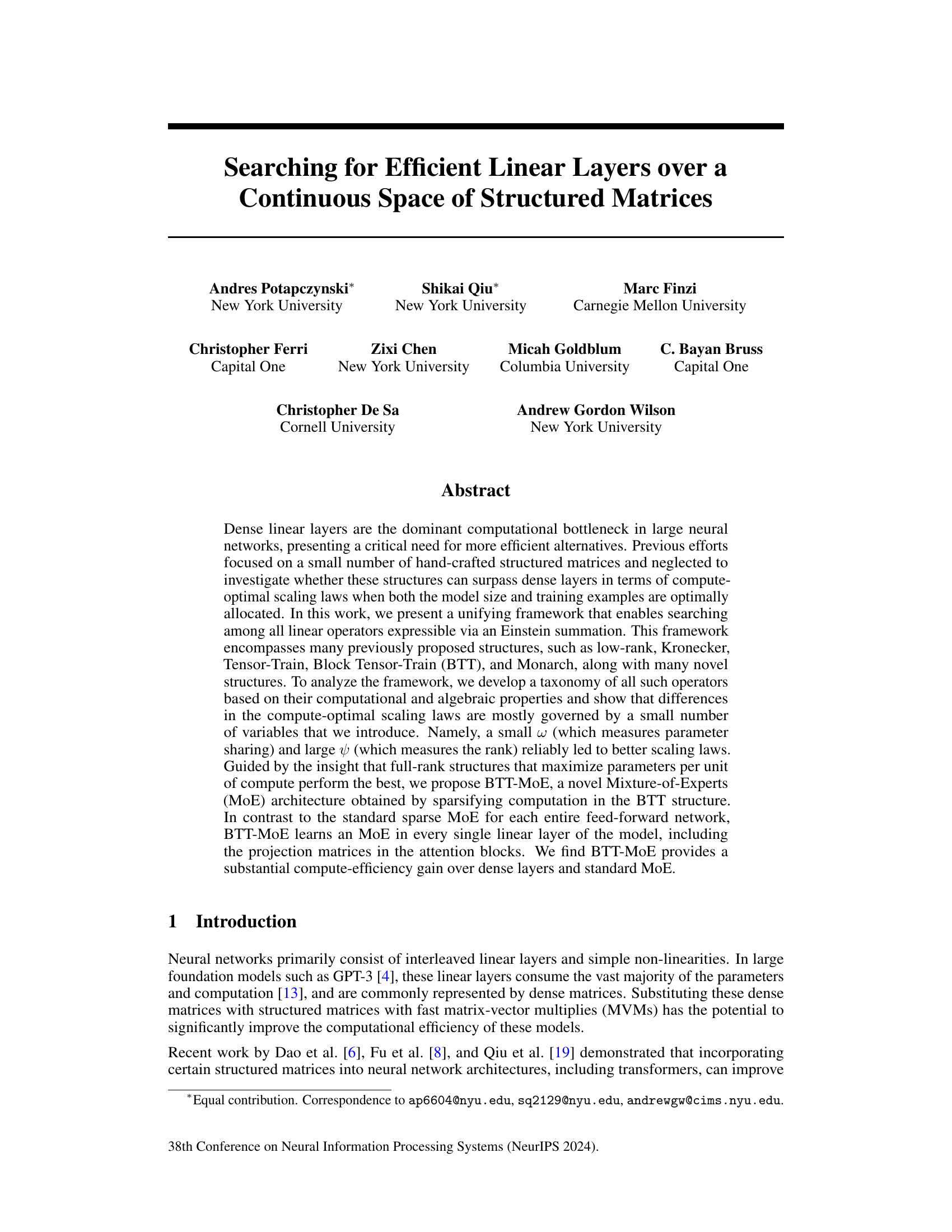

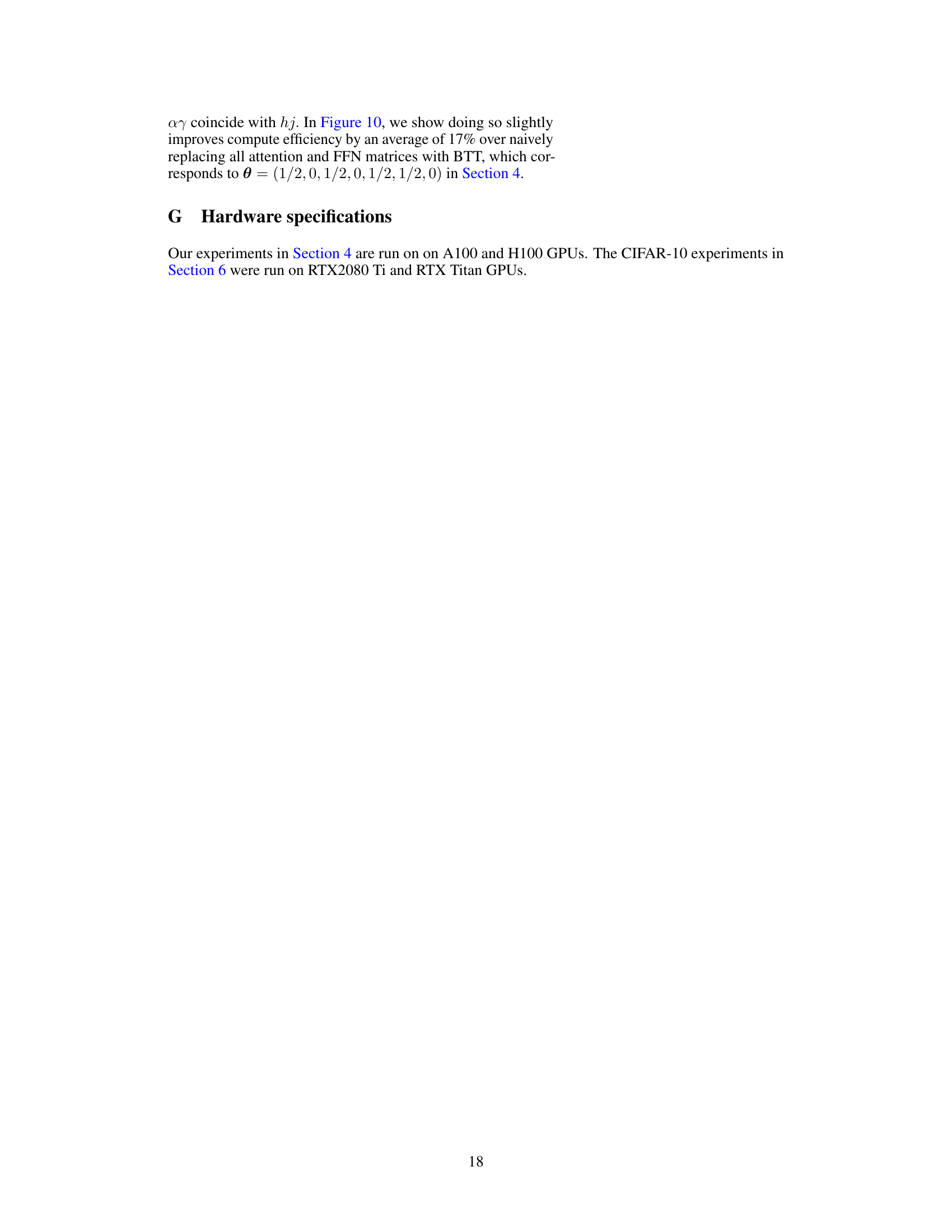

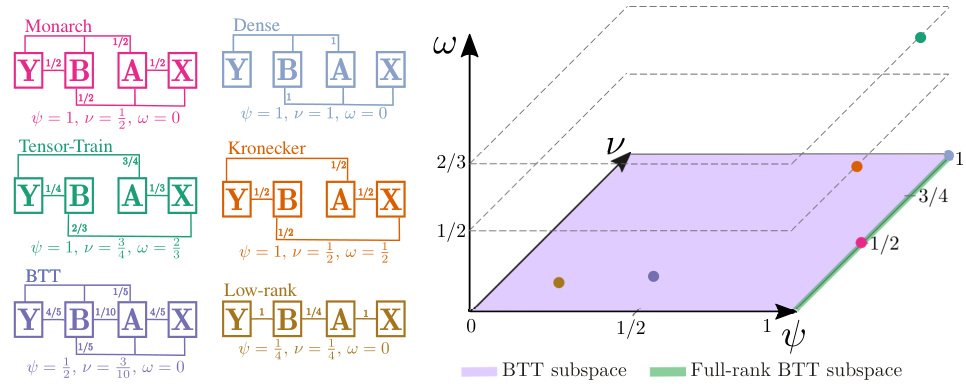

🔼 This figure demonstrates how the authors use Einstein summation (Einsum) to parameterize a wide range of structured matrices and search for the most efficient one for compute-optimal training. The left panel shows a diagram of a general two-factor Einsum. The middle panel lists examples of well-known matrix structures and their corresponding parameters within the Einsum framework. Finally, the right panel displays the compute-optimal scaling laws for various structures when applied to GPT-2 language model training, showcasing the performance differences compared to dense layers.

read the caption

Figure 1: We use Einsums to parameterize a wide range of structured matrices and search for the most efficient structure for compute-optimal training. Left: A diagrammatic representation of a general two-factor Einsum. We parameterize the space of Einsums through a real-valued vector θ = (θα, θβ, θη, θδ, θε, θφ, θρ) ∈ [0, 1]7. This space captures many well-known structures through specific values of 0. Middle: Example of well-known structures with their values. Any omitted line implies the value of the entry in the vector is 0. Right: Compute-optimal scaling laws of example structures for GPT-2 on OpenWebText when substituting its dense layers (see details in Section 4).

In-depth insights#

Einsum Parameterization#

The concept of “Einsum Parameterization” in the context of a research paper likely refers to a novel method for representing and manipulating structured matrices within neural networks using Einstein summation notation. This approach offers a significant advantage by enabling a continuous exploration of the vast space of possible structured matrices, moving beyond a discrete set of hand-crafted designs. A key benefit is the unification of many previously disparate structures (like low-rank, Kronecker, and Tensor-Train) under a single framework. This allows for systematic comparison and optimization of different structures according to their computational efficiency and performance on specific tasks. The parameterization likely involves defining a set of parameters that control the structure of the Einsum, thus allowing for the systematic exploration and optimization of the matrix structure within a continuous search space. This could reveal previously unknown, highly efficient structures that outperform existing designs. The approach may also lend itself to automated search techniques, enabling the discovery of optimal structures for various tasks and computational constraints.

Taxonomy of Einsums#

The proposed taxonomy of Einsums offers a novel way to categorize and understand the vast space of structured linear layers. It moves beyond simply listing existing structures by introducing three key scalar quantities: ω (parameter sharing), ψ (rank), and ν (compute intensity). This framework allows for a more nuanced comparison of different structures based on their computational and algebraic properties. Full-rank structures (ψ = 1) with no parameter sharing (ω = 0) emerge as computationally superior. The taxonomy also helps to explain the observed scaling laws during training, revealing that differences in compute-optimal scaling are primarily determined by these three scalar quantities. This provides a powerful tool for both understanding and designing efficient linear layers within neural networks, enabling targeted exploration of the Einsum space and potentially leading to the discovery of novel, high-performing architectures.

Compute-Optimal Scaling#

The concept of compute-optimal scaling is crucial for evaluating the efficiency of large neural network models. It shifts the focus from simply scaling model size to optimally allocating resources between model size and training data, given a fixed computational budget. The authors demonstrate that many previously lauded structured matrix alternatives to dense linear layers, while showing improvements in smaller-scale experiments, do not necessarily yield superior compute-optimal scaling laws in the context of large language models. This highlights the importance of considering computational cost not just in terms of model parameters but also the tradeoff with training data. The study reveals that parameter sharing and rank significantly impact compute-optimal scaling, favoring full-rank structures without parameter sharing. This counter-intuitive result challenges the prevailing notion that sparsity inherently equates to efficiency, showing that maximizing parameters used per FLOP is key for better scaling in this compute-constrained regime. The development of the BTT-MoE architecture, which achieves this by utilizing a Mixture of Experts approach within the linear layers themselves, provides a strong case study illustrating that carefully designed high-parameter count structures can achieve substantially better compute-optimal scaling laws compared to both standard dense and sparse MoE techniques.

BTT-MoE: A New Model#

The proposed BTT-MoE model presents a novel approach to enhancing the computational efficiency of large neural networks. Instead of applying Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) at the level of entire feed-forward networks, BTT-MoE integrates MoE into individual linear layers. This granular application of MoE, combined with the inherent efficiency of Block Tensor-Train (BTT) matrices, leads to significant compute savings. The model’s effectiveness is demonstrated through experiments on GPT-2, showcasing substantial gains over both dense layers and standard MoE approaches. A key advantage lies in the application of BTT-MoE to all linear layers, including those within attention blocks. This comprehensive integration, unlike standard MoE which typically targets specific network components, maximizes the potential for computational efficiency improvements across the entire model. Furthermore, the theoretical analysis underpinning BTT-MoE provides a valuable framework for understanding the compute-optimal scaling laws of different matrix structures, offering valuable insights into the design and optimization of future efficient neural network architectures.

Limitations and Future#

The research, while demonstrating significant advancements in efficient linear layers for neural networks using a novel continuous parameterization of structured matrices, acknowledges several limitations. Compute-optimal scaling laws, though investigated, may not fully capture real-world scenarios where other factors like memory and inference time are crucial. The study primarily focuses on language modeling and image generation, potentially limiting the generalizability to other tasks. While the proposed BTT-MoE architecture shows promise, its performance heavily depends on proper initialization and scaling laws, aspects which require further research for wider applicability. Future work should explore expanding the framework to other tasks and datasets, and further explore the intricate interplay between parameter sharing, rank, compute intensity, and model architecture. Addressing these limitations would pave the way for more robust and generalizable results, potentially leading to wider adoption of structured linear layers in large-scale neural network training.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates a taxonomy of Einsum linear structures, visualizing their properties in a 3D space defined by parameter sharing (ω), rank (ψ), and compute intensity (ν). The plot shows how various known matrix structures (Monarch, Dense, Tensor-Train, Kronecker, BTT, Low-rank) are positioned within this 3D space, highlighting two key subspaces: the BTT subspace (ω=0, maximizing parameters per FLOP) and the full-rank BTT subspace (ω=0, ψ=1). The figure demonstrates that full-rank BTT structures without parameter sharing generally perform best across multiple tasks.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustrating the Einsum taxonomy. The 3D graph represents relevant quantities of the Einsum structure such as the amount of parameter sharing ω (x-axis), its rank ψ (y-axis), and its compute intensity ν (z-axis). The structures on the left of the figure appear as dots on the graph based on their coordinates θ. We highlight two key subspaces. (a) The BTT subspace, characterized by no parameter sharing ω = 0, learning the maximum number of parameters per FLOP. (b) The full-rank BTT subspace where ω = 0 and ψ = 1. In Section 4 we show that the full-rank BTT subspace contains the most performant structures across multiple tasks.

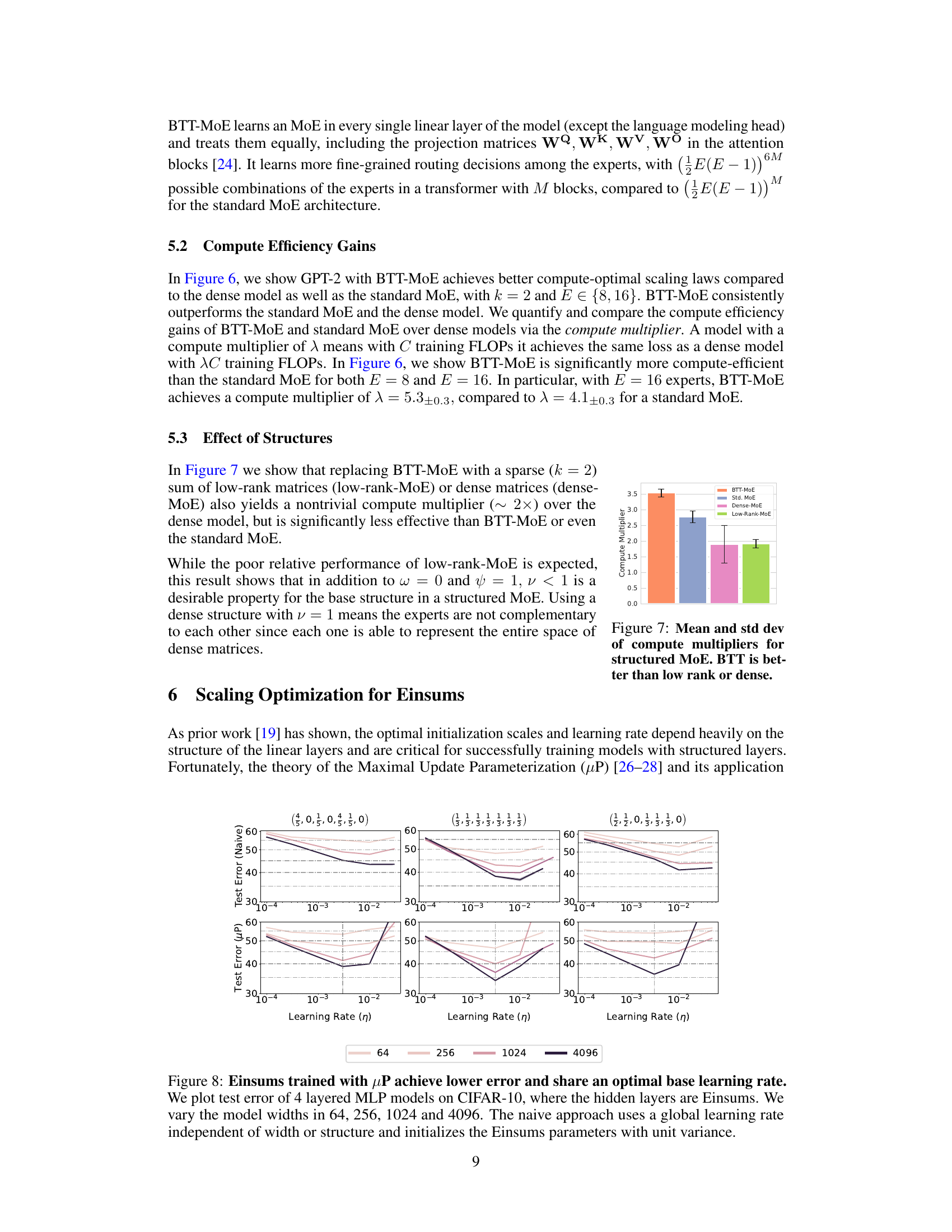

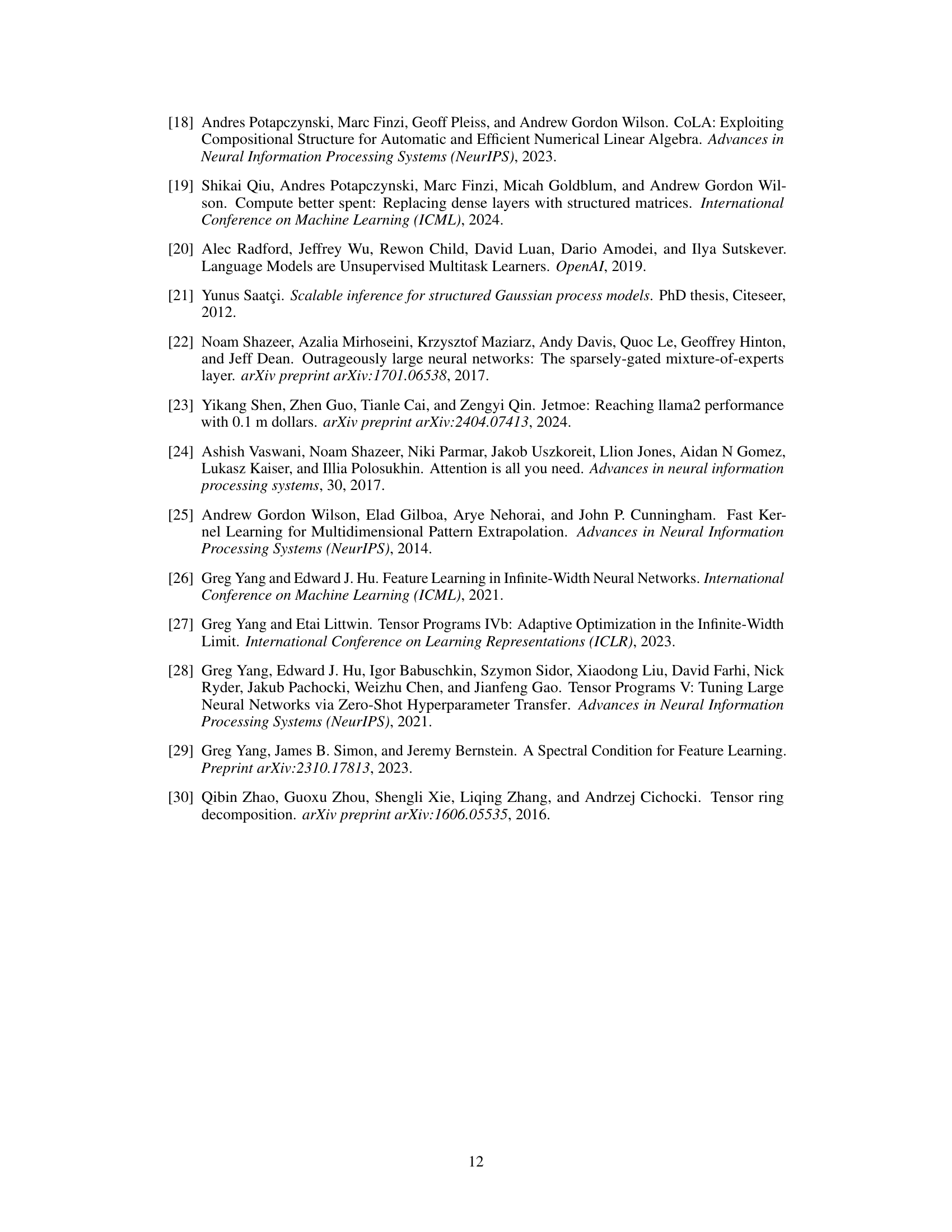

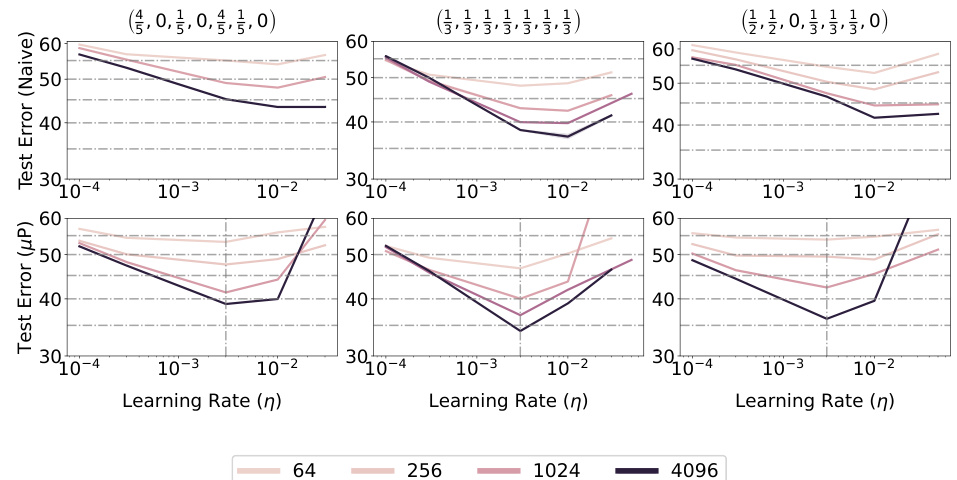

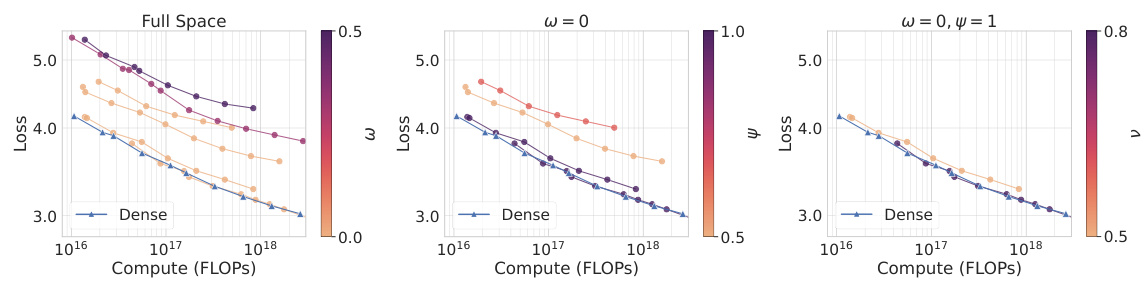

🔼 This figure shows how the three key scalar quantities (ω, ψ, ν) characterizing the space of Einsums affect the compute-optimal scaling laws. The left panel demonstrates that parameter sharing (ω > 0) negatively impacts scaling performance. The middle panel illustrates that, for structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) exhibit better scaling than low-rank ones (ψ < 1). Finally, the right panel indicates that, within the subspace of full-rank structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0, ψ = 1), various structures demonstrate near-identical scaling laws compared to dense matrices, suggesting that the absence of parameter sharing and full rank are key factors for efficient linear layers.

read the caption

Figure 4: The taxonomy parameters (ω, ψ) explain differences in the scaling laws. (Left): parameter sharing (ω > 0) leads to worse scaling. (Middle): among structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) scale better than low-rank structures (ψ < 1). (Right): in the (ω = 0, ψ = 1) subspace, various structures have nearly indistinguishable scaling laws compared to dense matrices, suggesting that not implementing parameter sharing and being full-rank are the necessary and sufficient conditions for a compute-efficient linear layer for GPT-2.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of the three key scalar quantities (ω, ψ, ν) on the scaling laws of different Einsum linear layers in the context of GPT-2 training. The left panel demonstrates that parameter sharing (ω > 0) negatively affects scaling performance. The middle panel illustrates that, within the parameter-sharing-free subspace (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) exhibit superior scaling compared to low-rank ones (ψ < 1). The right panel reveals that, within the subspace where ω = 0 and ψ = 1, various structures demonstrate very similar scaling behavior to dense matrices. This suggests that the absence of parameter sharing and full-rank nature are crucial for achieving efficient linear layers.

read the caption

Figure 4: The taxonomy parameters (ω, ψ, ν) explain differences in the scaling laws. (Left): parameter sharing (ω > 0) leads to worse scaling. (Middle): among structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) scale better than low-rank structures (ψ < 1). (Right): in the (ω = 0, ψ = 1) subspace, various structures have nearly indistinguishable scaling laws compared to dense matrices, suggesting that not implementing parameter sharing and being full-rank are the necessary and sufficient conditions for a compute-efficient linear layer for GPT-2.

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the taxonomy parameters (ω, ψ, ν) and the compute-optimal scaling laws of different Einsum linear layers in the GPT-2 language model. The left panel shows that parameter sharing (ω > 0) leads to worse scaling laws. The middle panel shows that among structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) exhibit better scaling than low-rank structures (ψ < 1). The right panel demonstrates that within the subspace of structures with no parameter sharing (ω = 0) and full rank (ψ = 1), various structures exhibit nearly identical scaling laws to dense matrices, indicating that the absence of parameter sharing and full rank are crucial for efficient linear layers in GPT-2.

read the caption

Figure 4: The taxonomy parameters (ω, ψ, ν) explain differences in the scaling laws. (Left): parameter sharing (ω > 0) leads to worse scaling. (Middle): among structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) scale better than low-rank structures (ψ < 1). (Right): in the (ω = 0, ψ = 1) subspace, various structures have nearly indistinguishable scaling laws compared to dense matrices, suggesting that not implementing parameter sharing and being full-rank are the necessary and sufficient conditions for a compute-efficient linear layer for GPT-2.

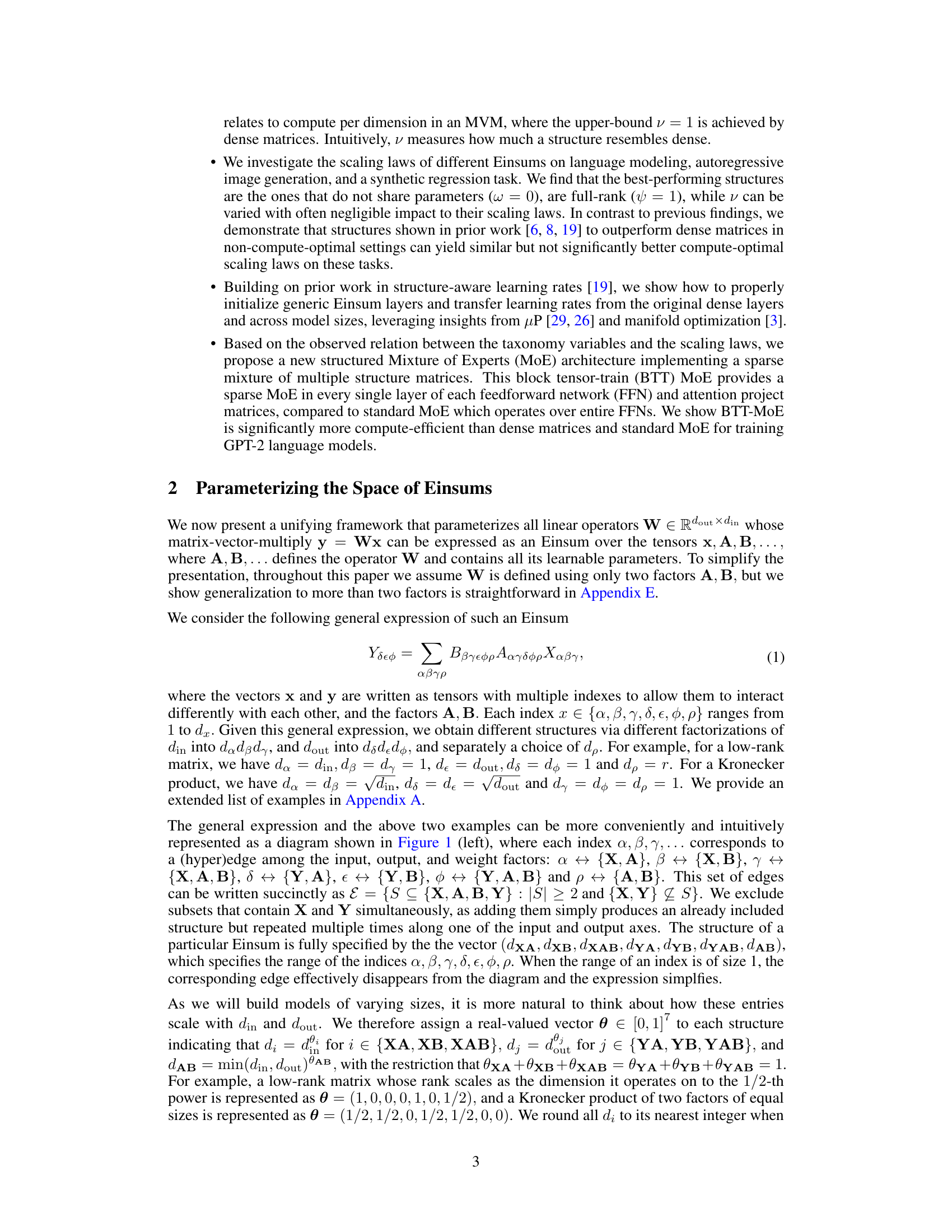

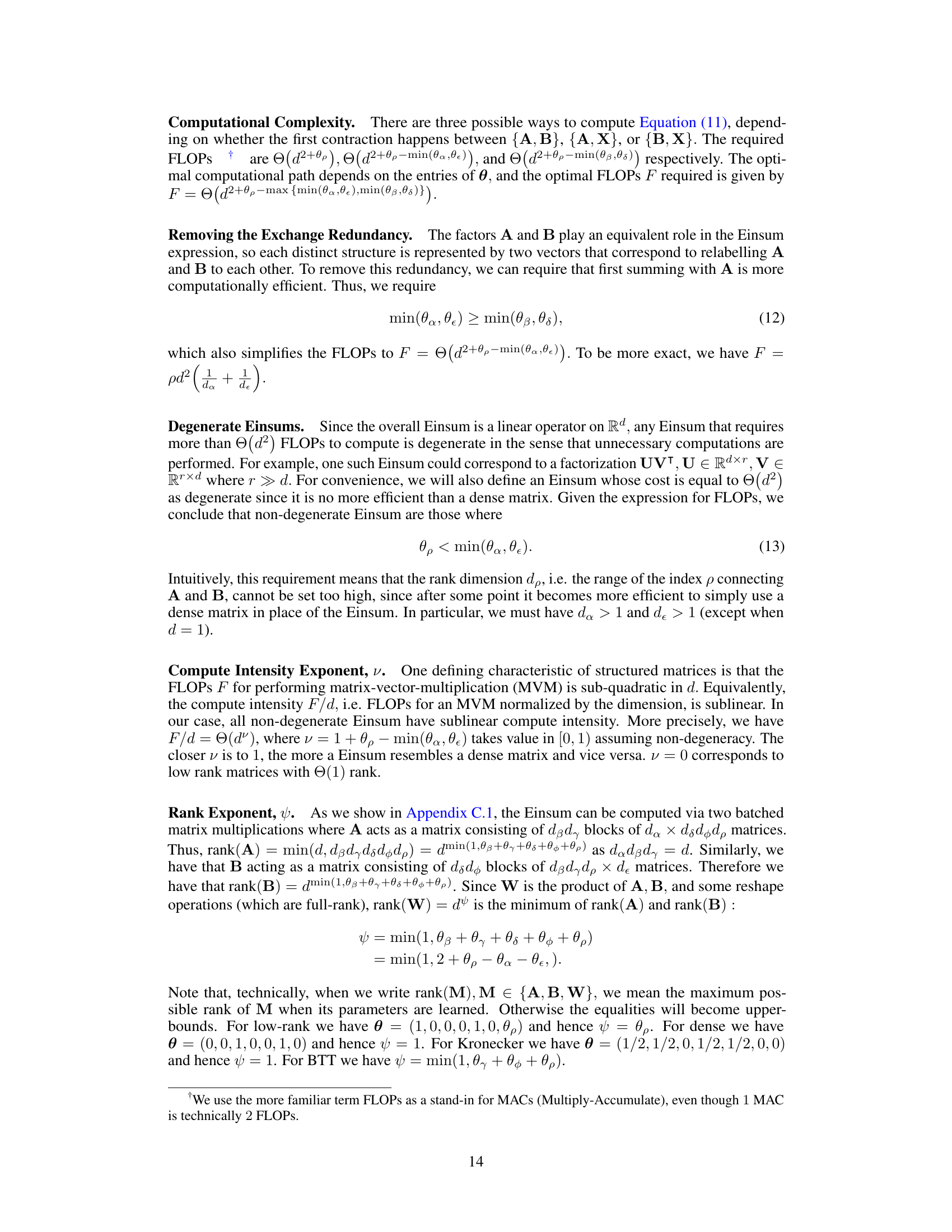

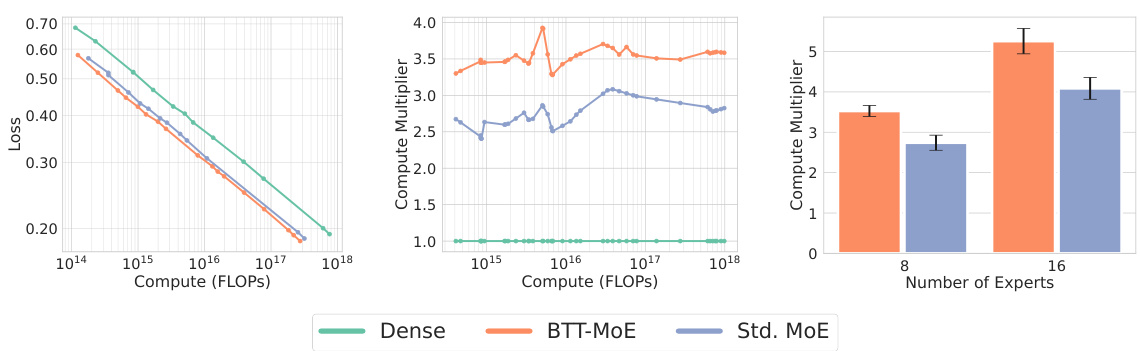

🔼 This figure shows the compute-optimal scaling laws for three different models: dense GPT-2, standard MoE, and BTT-MoE, demonstrating that BTT-MoE has significantly better scaling laws. The left panel shows the compute-optimal frontier for 8 experts. The middle panel shows the compute multiplier of BTT-MoE and standard MoE relative to dense as a function of FLOPs. The right panel shows how increasing the number of experts improves computational savings.

read the caption

Figure 6: BTT Mixture-of-Experts has significantly better compute-optimal scaling laws than dense GPT-2 and its standard MoE variant. (Left): Compute-optimal frontier with 8. (Middle): 8 experts compute multiplier of BTT-MoE and standard MoE relative to dense as a function of FLOPs required by the dense model to achieve the same loss. (Right): Increasing the number of experts improves computational savings. Mean and standard deviation of the compute multiplier over all compute observations for 8 and 16 experts.

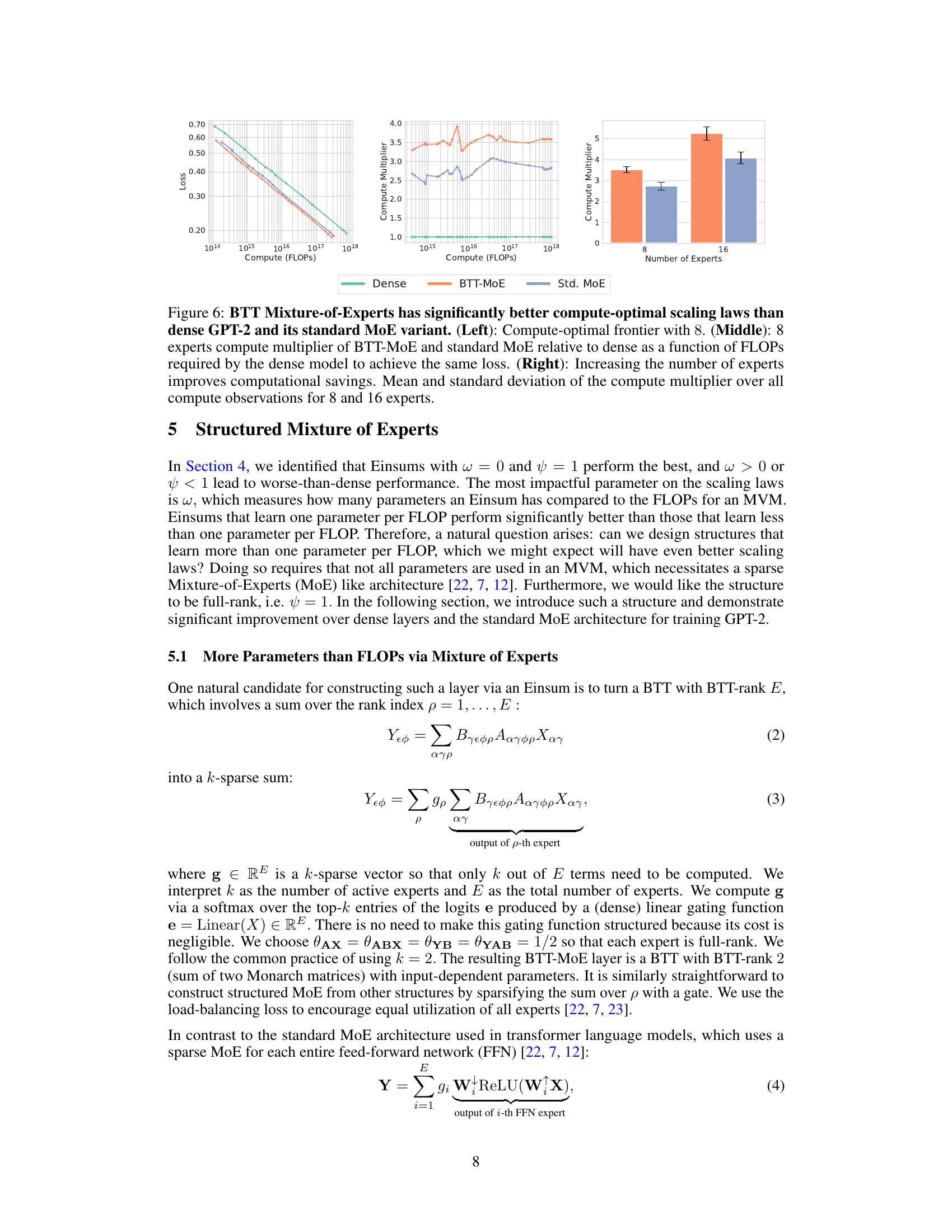

🔼 This bar chart compares the compute efficiency of different Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architectures using various base structures: BTT-MoE (Block Tensor Train), Std. MoE (standard MoE), Dense-MoE (dense MoE), and Low-Rank-MoE (low-rank MoE). The compute multiplier represents the compute efficiency gain over dense models. A higher multiplier indicates greater compute savings. The chart shows that BTT-MoE achieves the highest compute multiplier, demonstrating its superior compute efficiency compared to other MoE architectures.

read the caption

Figure 7: Mean and std dev of compute multipliers for structured MoE. BTT is better than low rank or dense.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of three key parameters (ω, ψ, ν) on the compute-optimal scaling laws of different Einsum linear layers in a GPT-2 language model. It demonstrates that parameter sharing (ω) negatively affects scaling, while full-rank structures (ψ = 1) exhibit better scaling than low-rank structures. Interestingly, the compute intensity (ν) has minimal impact on scaling within the subset of structures without parameter sharing and with full rank.

read the caption

Figure 4: The taxonomy parameters (ω, ψ, ν) explain differences in the scaling laws. (Left): parameter sharing (ω > 0) leads to worse scaling. (Middle): among structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) scale better than low-rank structures (ψ < 1). (Right): in the (ω = 0, ψ = 1) subspace, various structures have nearly indistinguishable scaling laws compared to dense matrices, suggesting that not implementing parameter sharing and being full-rank are the necessary and sufficient conditions for a compute-efficient linear layer for GPT-2.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of the taxonomy parameters (ω, ψ, ν) on the scaling laws of various Einsum structures when used in GPT-2. The left panel demonstrates that parameter sharing (ω > 0) negatively affects scaling. The middle panel highlights that, for structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) exhibit superior scaling compared to low-rank structures (ψ < 1). The right panel indicates that within the subspace where ω = 0 and ψ = 1, numerous structures demonstrate comparable scaling laws to dense matrices, implying that the absence of parameter sharing and full-rank nature are crucial for computational efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 4: The taxonomy parameters (ω, ψ, ν) explain differences in the scaling laws. (Left): parameter sharing (ω > 0) leads to worse scaling. (Middle): among structures without parameter sharing (ω = 0), full-rank structures (ψ = 1) scale better than low-rank structures (ψ < 1). (Right): in the (ω = 0, ψ = 1) subspace, various structures have nearly indistinguishable scaling laws compared to dense matrices, suggesting that not implementing parameter sharing and being full-rank are the necessary and sufficient conditions for a compute-efficient linear layer for GPT-2.

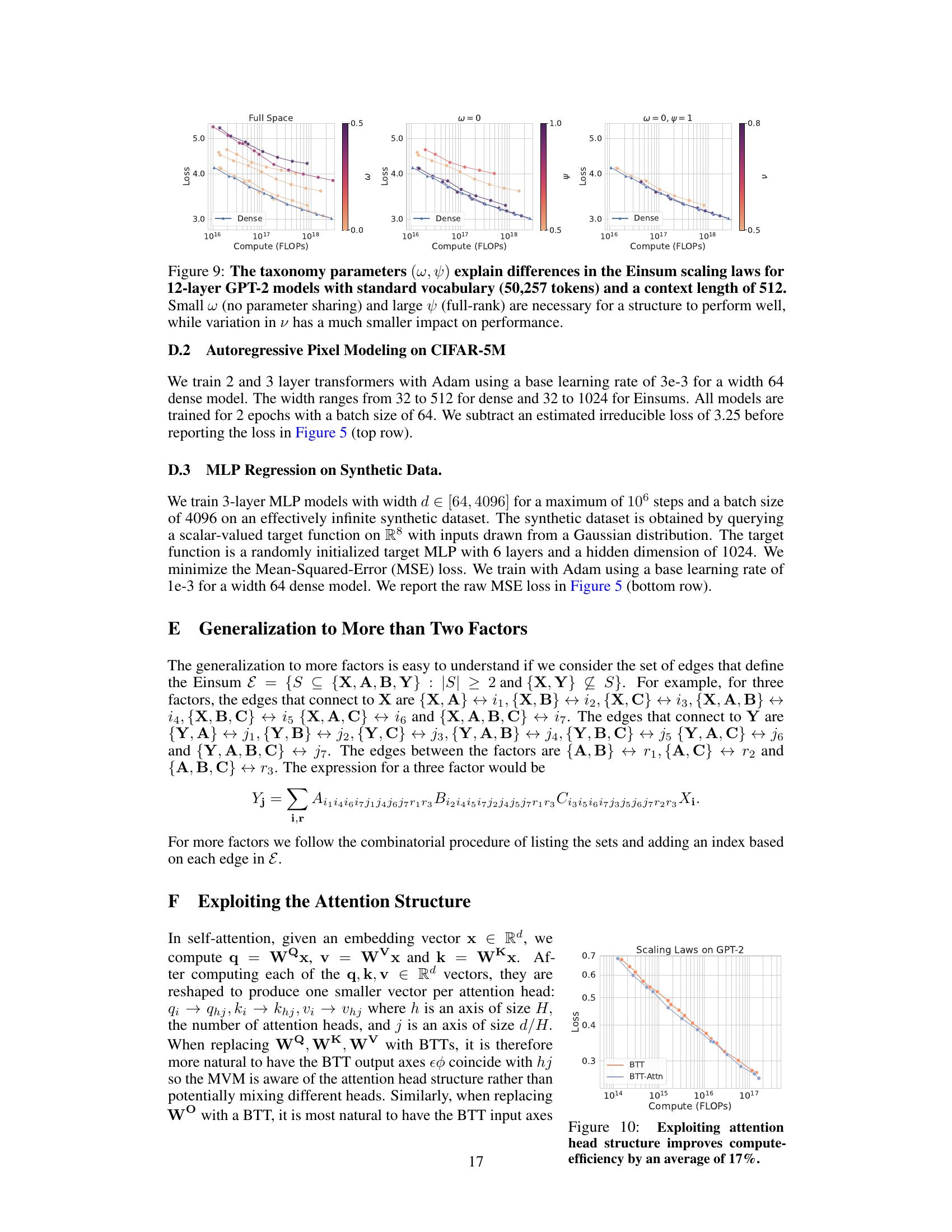

🔼 This figure shows the impact of incorporating the attention head structure into the BTT (Block Tensor Train) model. By aligning the BTT output axes with the attention head structure, the model achieves a 17% improvement in compute efficiency compared to a naive replacement of all attention and FFN (feed-forward network) matrices with BTT.

read the caption

Figure 10: Exploiting attention head structure improves compute-efficiency by an average of 17%.

Full paper#