TL;DR#

Deep reinforcement learning often struggles with interpretability and generalization to long, repetitive tasks. Existing programmatic RL methods, which aim to address this using human-readable programs, often fail to effectively solve such problems or generalize well to longer testing horizons. This paper tackles this issue.

The paper proposes the Hierarchical Programmatic Option framework (HIPO) to address these shortcomings. HIPO employs a program embedding space to represent programs, a search algorithm to select effective, diverse, and compatible programs as options, and a high-level policy to manage option selection. Evaluation demonstrates that HIPO outperforms baselines on various long-horizon tasks, especially in generalization to longer horizons.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses the limitations of existing programmatic reinforcement learning methods by introducing a novel framework (HIPO) that uses human-readable programs as options to solve long and repetitive tasks. HIPO shows improved interpretability and generalizes effectively to longer horizons, offering a valuable approach for researchers working on interpretable and robust AI solutions. Its use of program embedding and CEM-based option selection provides a novel approach, opening avenues for enhancing efficiency and scalability in RL.

Visual Insights#

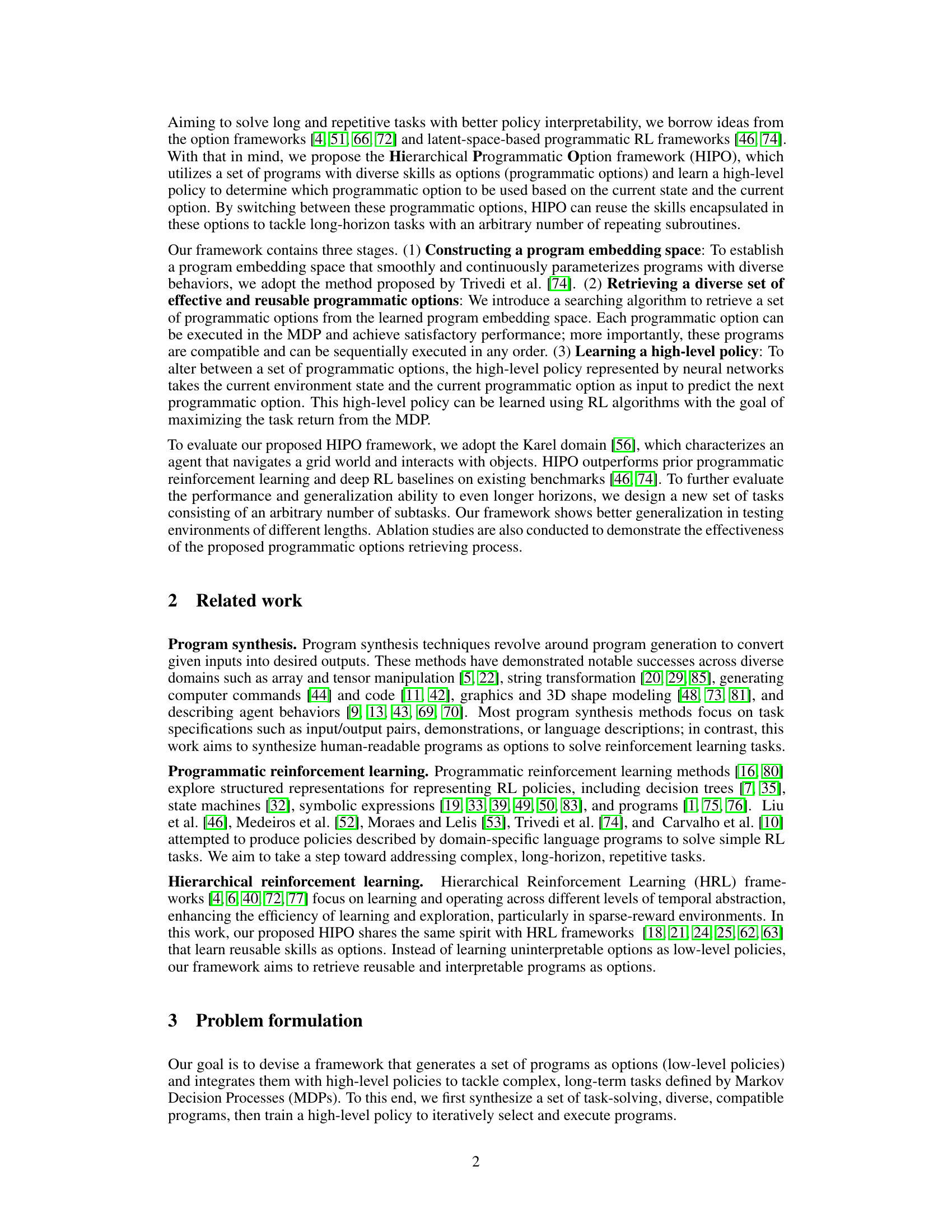

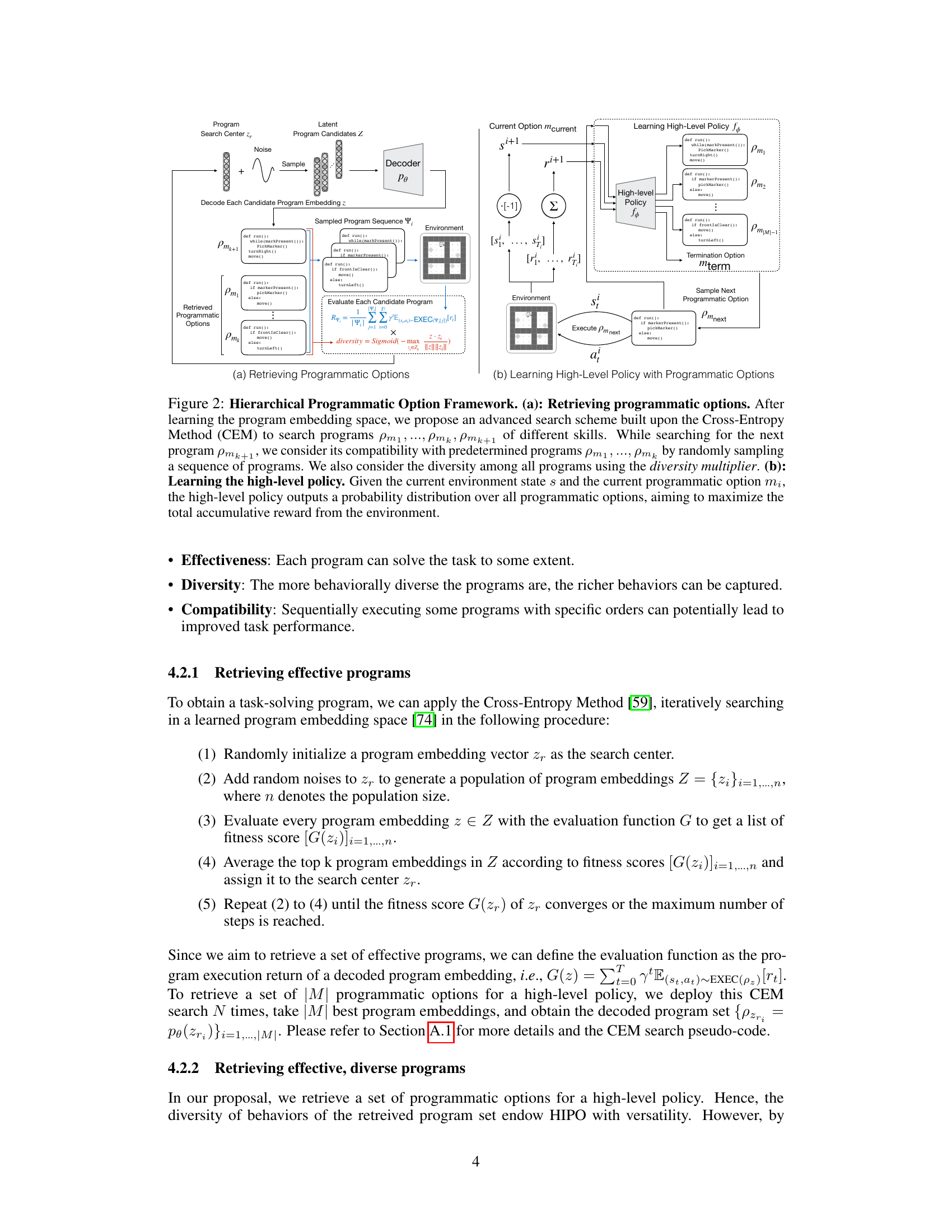

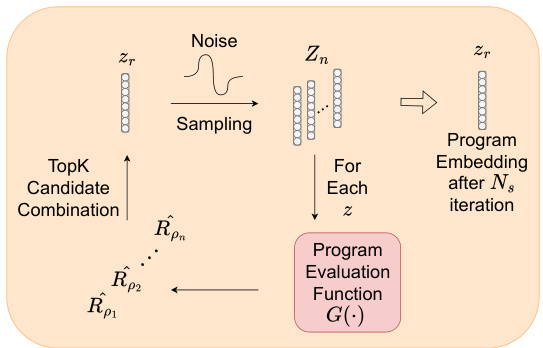

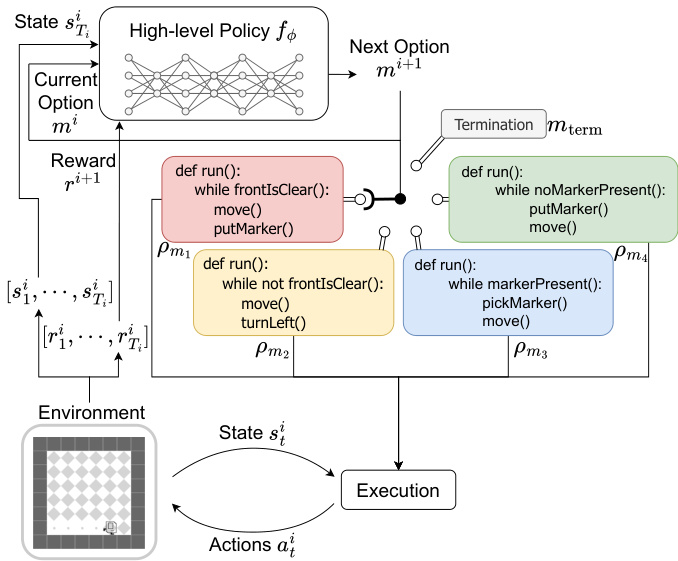

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed HIPO framework, showing two stages: (a) the program search algorithm that retrieves a set of diverse and compatible programs as options and (b) the high-level policy learning process using the retrieved programs to solve long-horizon tasks by switching between these options.

read the caption

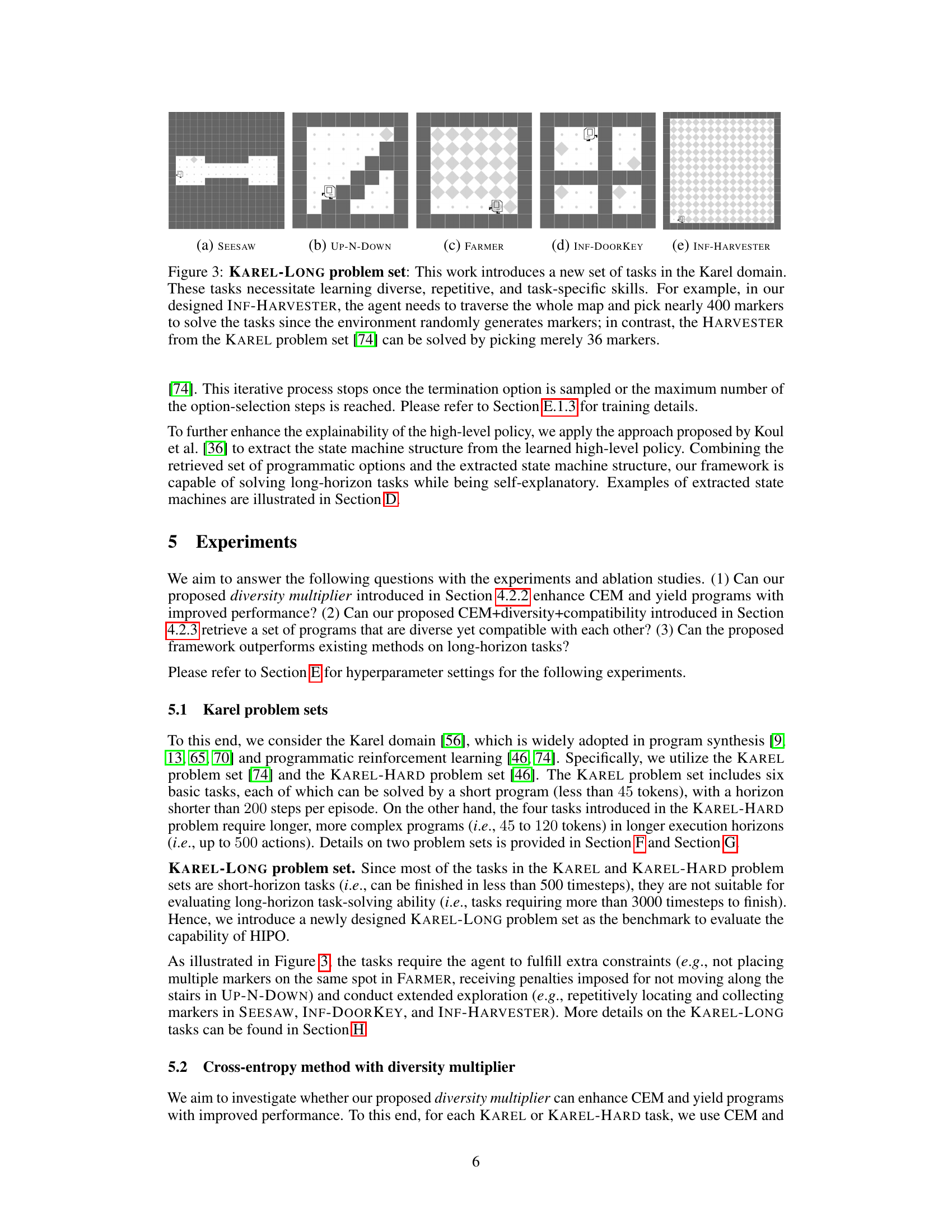

Figure 2: Hierarchical Programmatic Option Framework. (a): Retrieving programmatic options. After learning the program embedding space, we propose an advanced search scheme built upon the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) to search programs pm1,..., Pmk, pmk+1 of different skills. While searching for the next program pmk+1, we consider its compatibility with predetermined programs pm1, …, Pmk by randomly sampling a sequence of programs. We also consider the diversity among all programs using the diversity multiplier. (b): Learning High-Level Policy with Programmatic Options.

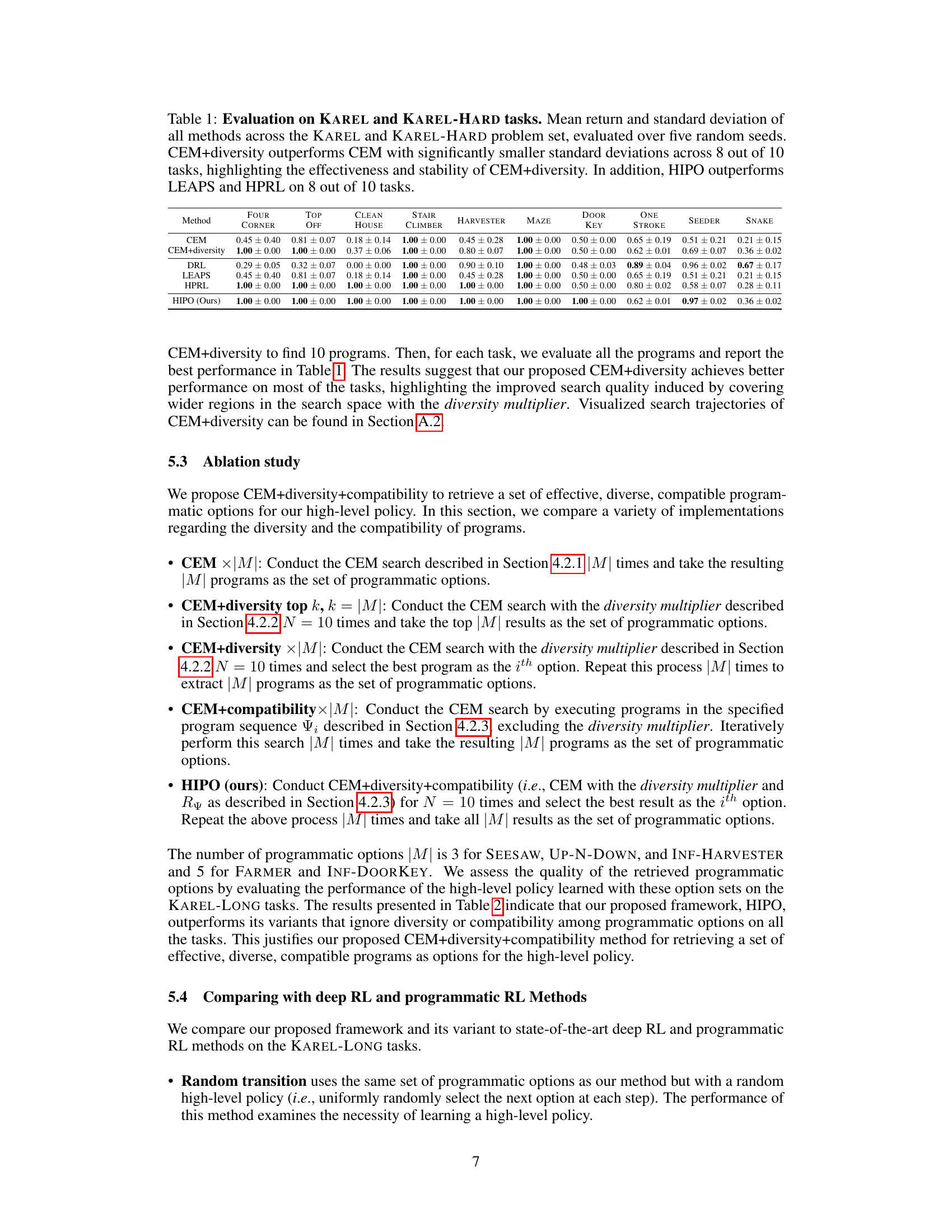

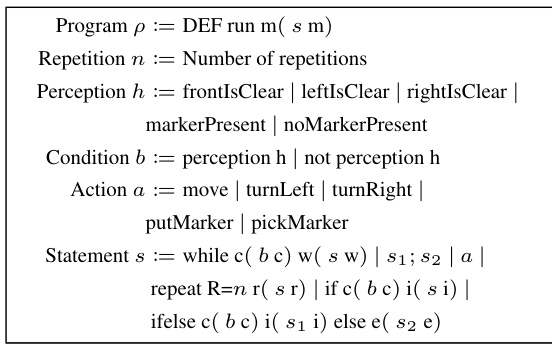

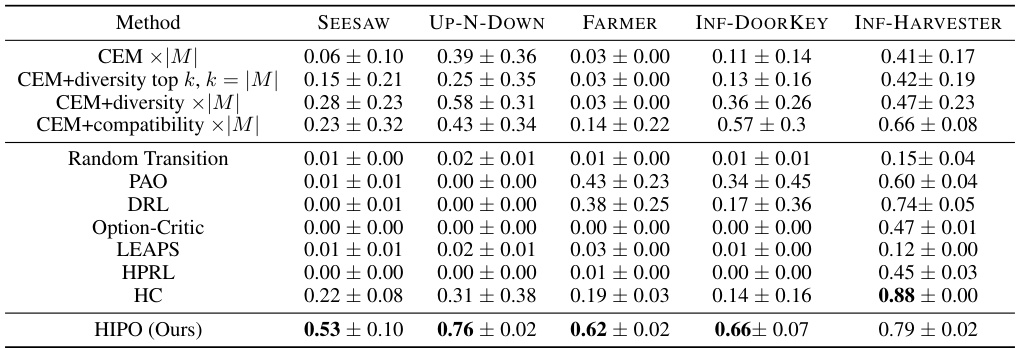

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating different reinforcement learning methods on the KAREL and KAREL-HARD tasks. The metrics used are mean return and standard deviation, calculated across five random seeds for each task. The comparison highlights the superior performance and stability of the CEM+diversity method compared to the standard CEM method. Furthermore, it demonstrates the outperformance of the proposed HIPO framework compared to LEAPS and HPRL on most of the tasks.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation on KAREL and KAREL-HARD tasks. Mean return and standard deviation of all methods across the KAREL and KAREL-HARD problem set, evaluated over five random seeds. CEM+diversity outperforms CEM with significantly smaller standard deviations across 8 out of 10 tasks, highlighting the effectiveness and stability of CEM+diversity. In addition, HIPO outperforms LEAPS and HPRL on 8 out of 10 tasks.

In-depth insights#

Hierarchical Programmatic Options#

The concept of “Hierarchical Programmatic Options” suggests a novel approach to reinforcement learning where human-readable programs serve as building blocks for complex policies. Instead of learning a monolithic, opaque neural network, the system learns a hierarchy of programs, each performing a specific subtask (option). A higher-level policy then decides which option to execute at each time step, based on the current state. This hierarchical structure facilitates better interpretability, as the logic of the system is expressed through modular, understandable programs. It also promotes generalization because learned subtasks can be reused across different situations and potentially scaled to longer horizons than what’s achievable with flat programmatic policies. The key challenge lies in designing efficient methods to search for and select a diverse, yet compatible, set of programs as options. The framework’s effectiveness relies heavily on the compatibility and diversity of options as the higher-level policy depends on their seamless integration. Effective search algorithms are essential to find suitable program options and ensure that they are not overly similar, hence limiting the flexibility of the system. Finally, the high-level policy itself could benefit from techniques enhancing interpretability, perhaps by representing it as a structured model rather than a black box neural network.

CEM Enhancements#

The paper explores enhancements to the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) for program synthesis within a reinforcement learning context. The core enhancement involves a diversity multiplier, which penalizes the selection of programs that are too similar to those already chosen. This encourages exploration of the program space and improves the diversity and ultimately the effectiveness of the synthesized program set. A second, more sophisticated enhancement integrates a compatibility measure into the CEM evaluation function, explicitly rewarding the selection of programs which perform well when executed sequentially with previously selected programs. This addresses the crucial issue of program compatibility when assembling complex task solutions from modular program options. These CEM enhancements are experimentally validated, demonstrating their effectiveness in generating a more diverse and compatible set of program options, leading to improvements in overall reinforcement learning performance across various long-horizon tasks. The combined approach strikes a balance between exploration, exploitation and collaboration, effectively generating a skill set suitable for complex, long and repeated sub-tasks.

Long-Horizon Tasks#

Addressing long-horizon tasks presents a unique challenge in reinforcement learning due to the extended temporal dependencies and sparse reward signals. Traditional methods struggle to effectively learn optimal policies in such scenarios, often resulting in poor generalization and suboptimal performance. The complexity arises from the need for the agent to plan and execute sequences of actions over long time horizons, requiring skill acquisition, temporal abstraction, and effective memory mechanisms. Successfully tackling long-horizon tasks necessitates designing frameworks that leverage these factors. Hierarchical approaches, decomposing complex tasks into subtasks, emerge as an effective solution, enabling better learning, planning and policy representation. Programmatic approaches can enhance interpretability by explicitly modeling policies as human-readable programs, facilitating analysis and improving trust in the learned behaviors. Therefore, a unified framework incorporating hierarchical structures and programmatic policies provides a promising direction, enabling both better performance and improved understandability in solving long-horizon tasks.

Interpretability and Generalization#

The inherent tension between interpretability and generalization in machine learning models is a central theme. Highly interpretable models, such as those employing simple decision trees or rule-based systems, often struggle to achieve the same level of accuracy and generalizability as more complex, less interpretable models like deep neural networks. The choice often involves a trade-off: prioritize the ability to understand how a model arrives at its decisions or its capacity to handle diverse, unseen data effectively? This paper’s proposed Hierarchical Programmatic Option (HIPO) framework attempts to navigate this trade-off. By expressing policies as human-readable programs, HIPO enhances interpretability. However, the success of HIPO hinges on the effectiveness of its program search and high-level policy learning, impacting its generalization capabilities. The experimental results provide some evidence of improved generalization to longer, more complex tasks compared to some standard approaches, highlighting a potential pathway to reconcile interpretability with better generalization in reinforcement learning. Further research could investigate ways to systematically enhance the diversity and compatibility of retrieved programs, crucial for generalization to new task instances that exhibit similar repetitive patterns but vary in length or other subtle characteristics.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Improving the efficiency and scalability of the program search algorithm is crucial; exploring advanced search techniques or incorporating prior knowledge, such as LLMs or offline datasets, could significantly enhance the speed and quality of option retrieval. Another important area is enhancing the generalizability of HIPO, enabling it to handle more diverse and complex tasks across various domains and with varying levels of noise or uncertainty. Further investigation into the potential limitations of using domain-specific languages is needed, considering the challenge of developing DSLs for different domains or adapting them to handle increasingly complex tasks. Finally, a deeper exploration into improving the interpretability of the high-level policy, perhaps through techniques like state machine extraction or formal methods for program verification, would enhance user trust and confidence in the learned policies.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed Hierarchical Programmatic Option framework (HIPO). Panel (a) shows the process of retrieving diverse and compatible programmatic options using a search algorithm based on the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM). The algorithm considers both the effectiveness of individual programs and their compatibility with previously selected programs to ensure a diverse set of skills. The diversity multiplier further enhances this process by discouraging the selection of similar programs. Panel (b) demonstrates how a high-level policy is used to select and execute the appropriate option based on the current state and the previously selected option. This allows the agent to reuse learned skills and efficiently solve long and repetitive tasks.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hierarchical Programmatic Option Framework. (a): Retrieving programmatic options. After learning the program embedding space, we propose an advanced search scheme built upon the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) to search programs pm1,..., Pmk, pmk+1 of different skills. While searching for the next program pmk+1, we consider its compatibility with predetermined programs pm1, …, Pmk by randomly sampling a sequence of programs. We also consider the diversity among all programs using the diversity multiplier. (b): Learning the high-level policy. Given the current environment state s and the current programmatic option mi, the high-level policy outputs a probability distribution over all programmatic options, aiming to maximize the total accumulative reward from the environment.

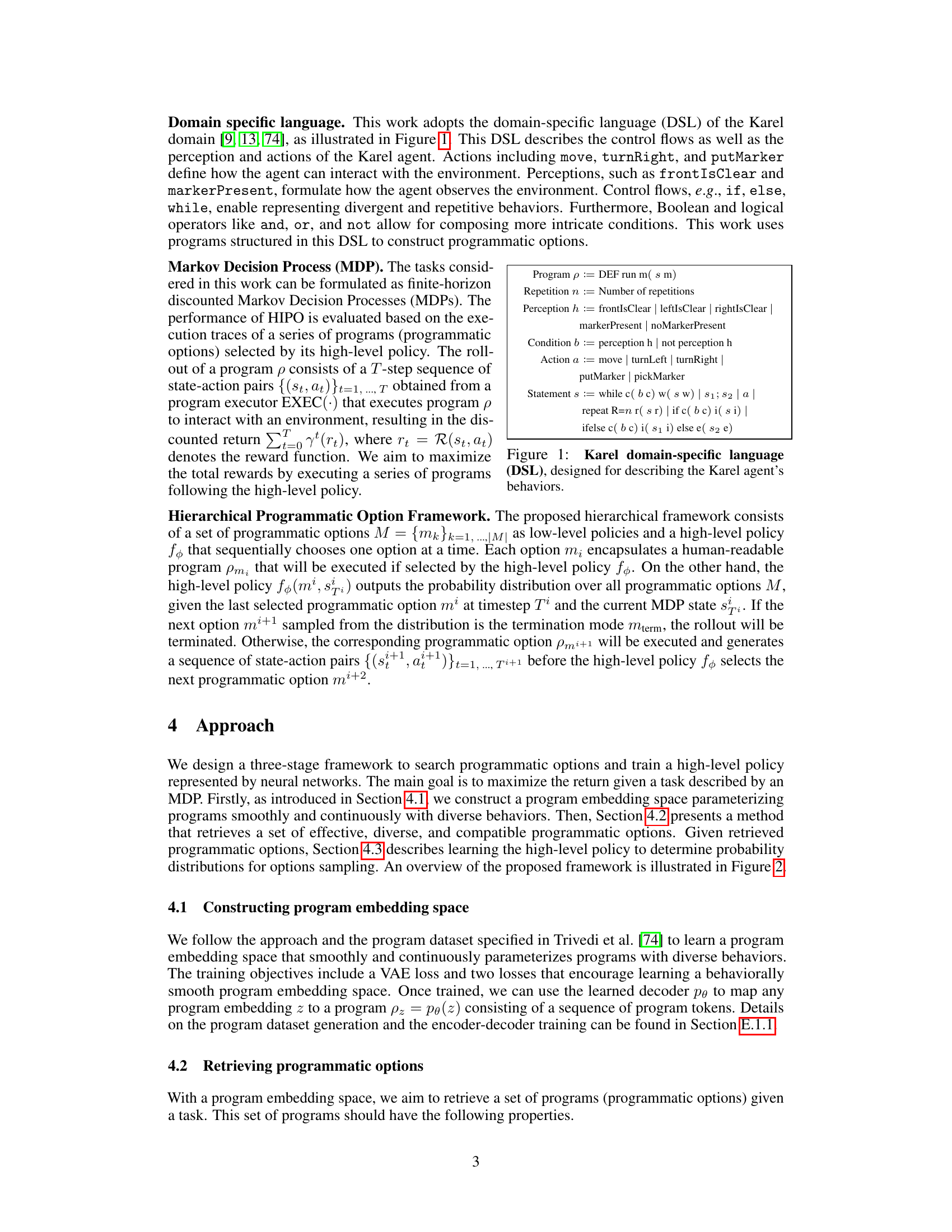

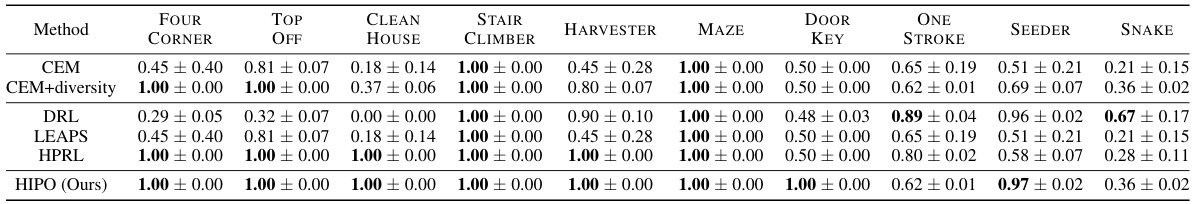

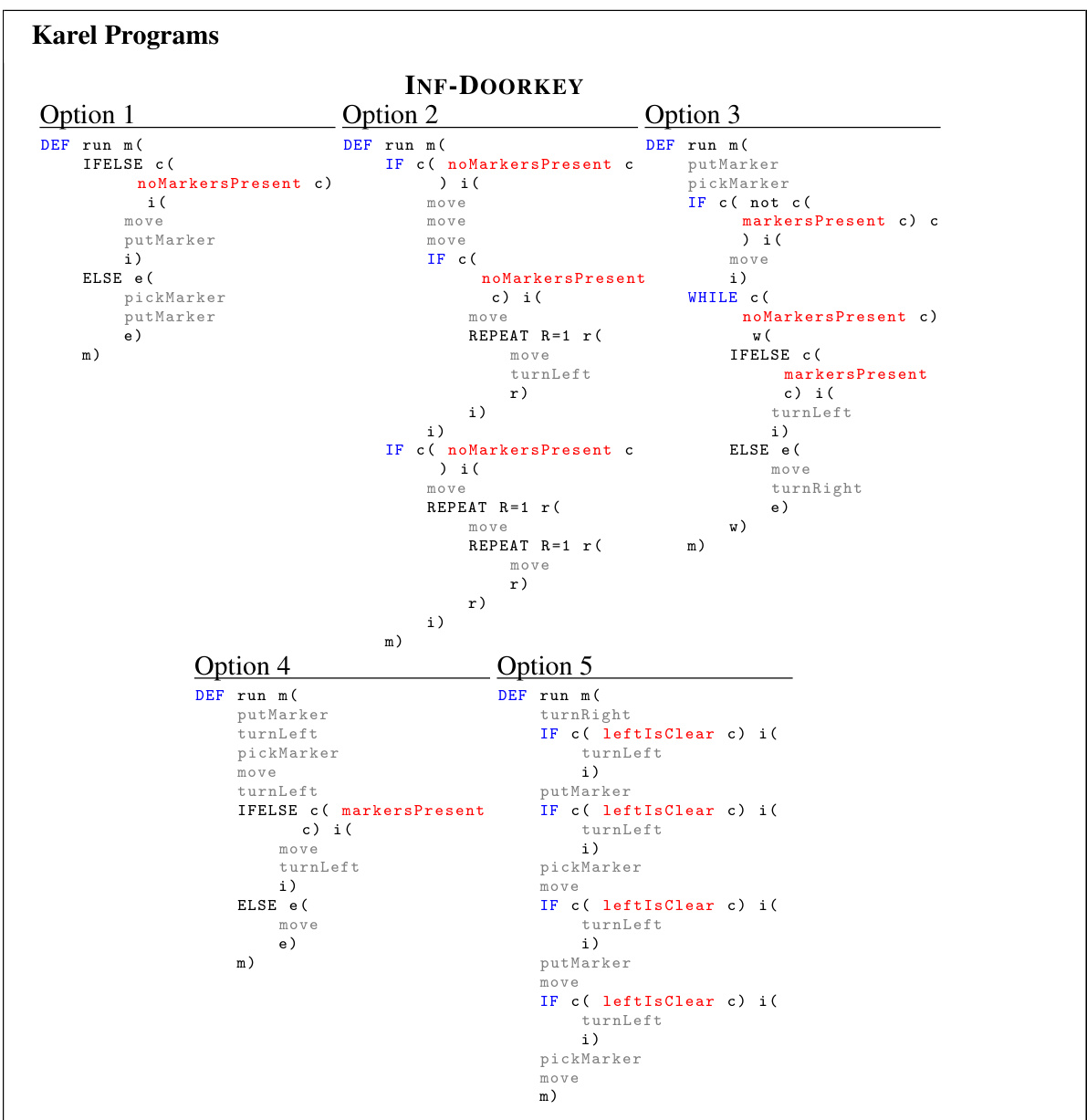

🔼 This figure shows five new complex tasks for the Karel domain, designed to test the capabilities of the proposed HIPO framework for handling long and repetitive tasks that require diverse and reusable skills. Each task involves a longer time horizon than previously studied tasks and requires more sophisticated planning and learning strategies to solve. The complexities are emphasized in the caption, highlighting the significant differences between these new challenges and previous benchmarks.

read the caption

Figure 3: KAREL-LONG problem set: This work introduces a new set of tasks in the Karel domain. These tasks necessitate learning diverse, repetitive, and task-specific skills. For example, in our designed INF-HARVESTER, the agent needs to traverse the whole map and pick nearly 400 markers to solve the tasks since the environment randomly generates markers; in contrast, the HARVESTER from the KAREL problem set [74] can be solved by picking merely 36 markers.

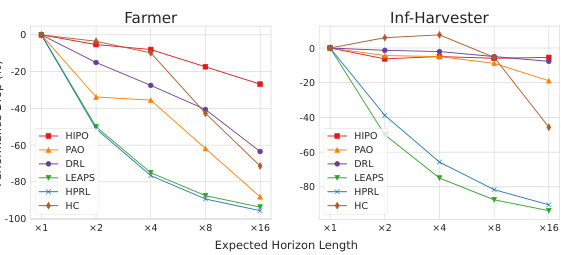

🔼 This figure shows two sub-figures. (a) compares the program sample efficiency of HIPO against other approaches by plotting the maximum validation return against the total number of executed programs. (b) evaluates the inductive generalization ability of HIPO by comparing its performance drop in testing environments with extended horizons against other methods.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) Program sample efficiency. The training curves of HIPO and other programmatic RL approaches, where the x-axis is the total number of executed programs for interacting with the environment, and the y-axis is the maximum validation return. This demonstrates that our proposed framework has better program sample efficiency and converges to better performance. (b) Inductive generalization performance. We evaluate and report the performance drop in the testing environments with an extended horizon, where the x-axis is the extended horizon length compared to the horizon of the training environments, and the y-axis is the performance drop in percentage. Our proposed framework can inductively generalize to longer horizons without any fine-tuning.

🔼 This figure illustrates the HIPO framework, which consists of two main stages: retrieving programmatic options and learning a high-level policy. The first stage uses a program embedding space and an advanced search method (CEM) to identify a set of effective, diverse, and compatible programs (options) with various skills. The compatibility of the selected programs is checked by evaluating random sequences of them. The diversity among selected options is considered to allow high-level versatility. The second stage uses the selected programs as low-level policies, and a neural network trains a high-level policy to choose the best option based on the current environment state and the current option. The final goal is to maximize the total reward obtained from the environment.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hierarchical Programmatic Option Framework. (a): Retrieving programmatic options. After learning the program embedding space, we propose an advanced search scheme built upon the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) to search programs pm1,..., Pmk, pmk+1 of different skills. While searching for the next program pmk+1, we consider its compatibility with predetermined programs pm1, …, Pmk by randomly sampling a sequence of programs. We also consider the diversity among all programs using the diversity multiplier. (b): Learning High-Level Policy with Programmatic Options

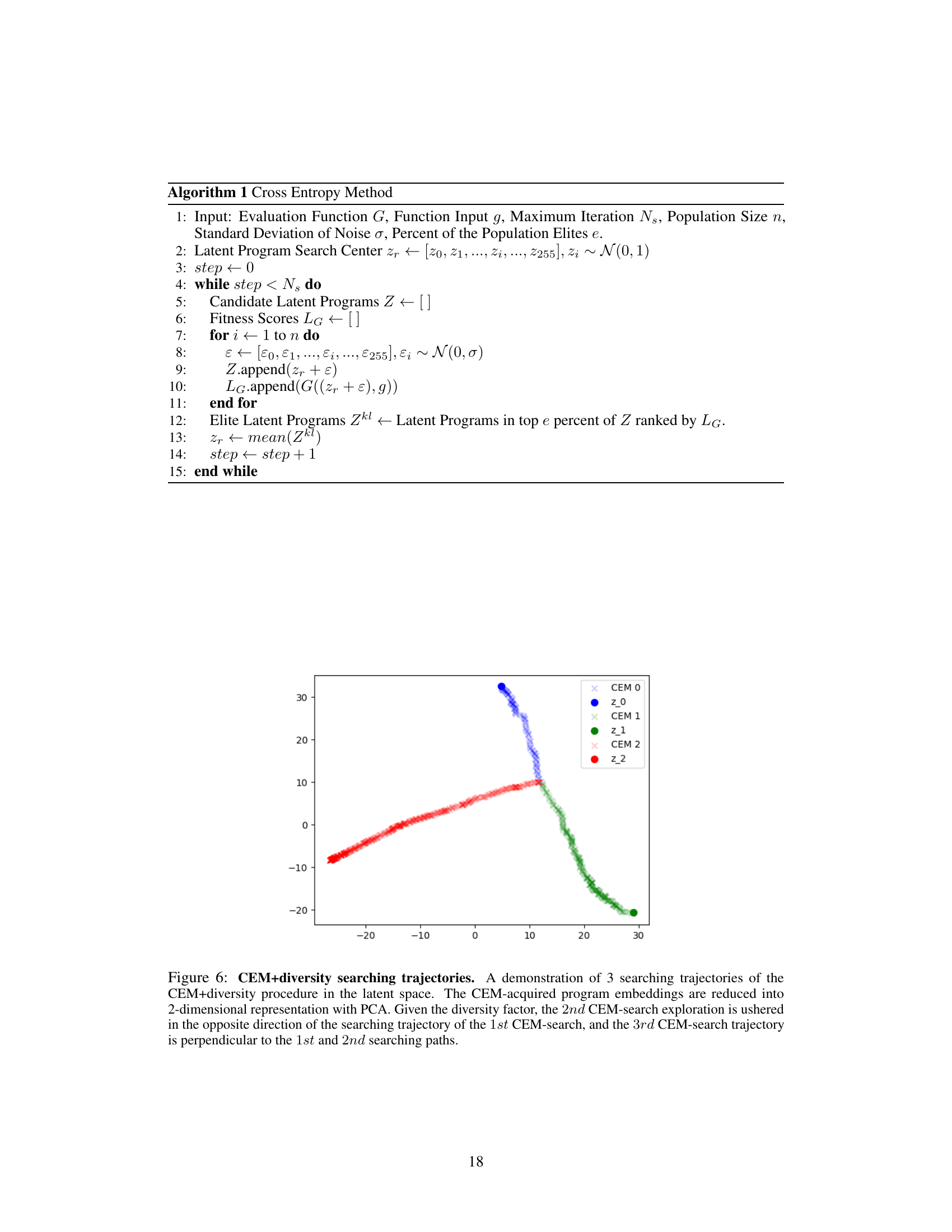

🔼 This figure shows three different searching trajectories obtained from the CEM+diversity algorithm in a 2D latent space (reduced from a higher dimensional space using PCA). The algorithm’s diversity factor influences the search direction. The first search follows a certain path. Subsequent searches, due to the diversity factor, explore directions that are opposite or perpendicular to previous searches, thus covering a wider area of the search space to ensure diversity in retrieved programs.

read the caption

Figure 6: CEM+diversity searching trajectories. A demonstration of 3 searching trajectories of the CEM+diversity procedure in the latent space. The CEM-acquired program embeddings are reduced into 2-dimensional representation with PCA. Given the diversity factor, the 2nd CEM-search exploration is ushered in the opposite direction of the searching trajectory of the 1st CEM-search, and the 3rd CEM-search trajectory is perpendicular to the 1st and 2nd searching paths.

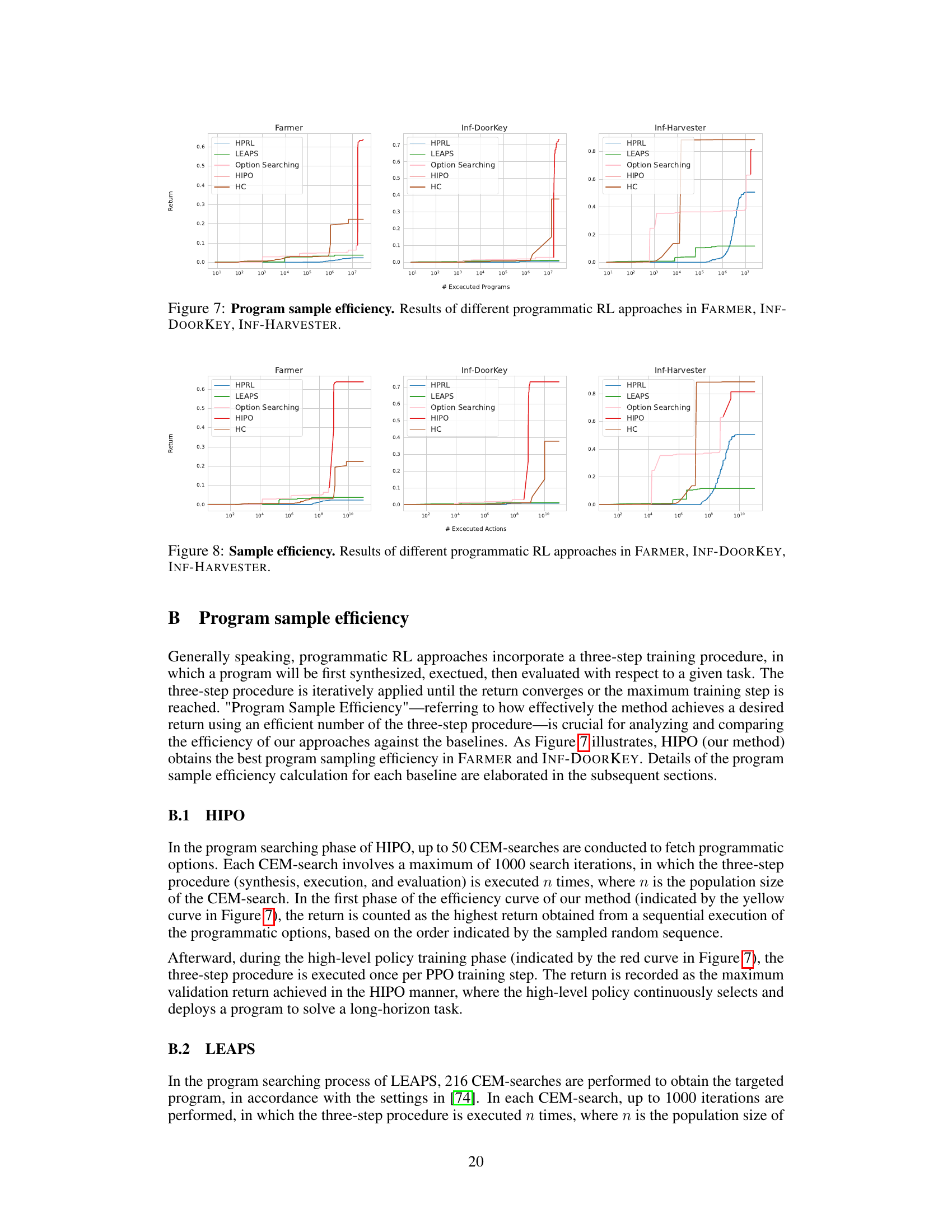

🔼 This figure shows the program sample efficiency of different programmatic reinforcement learning approaches, namely HIPO, LEAPS, HPRL, and HC, across three KAREL-LONG tasks: FARMER, INF-DOORKEY, and INF-HARVESTER. Program sample efficiency measures the total number of program executions required to achieve a certain level of performance. The x-axis represents the number of executed programs, and the y-axis shows the maximum validation return. The figure illustrates that HIPO achieves better program sample efficiency compared to other methods, indicating that it converges to optimal performance with fewer program executions.

read the caption

Figure 7: Program sample efficiency. Results of different programmatic RL approaches in FARMER, INF-DOORKEY, INF-HARVESTER.

🔼 This figure shows two graphs. Graph (a) compares the program sample efficiency of different reinforcement learning algorithms and demonstrates that the proposed HIPO framework has better program sample efficiency and converges faster. Graph (b) shows the inductive generalization performance of the algorithms by testing them in environments with extended horizons. The results show that HIPO maintains good performance in these extended horizon environments, demonstrating its inductive generalization capability.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) Program sample efficiency. The training curves of HIPO and other programmatic RL approaches, where the x-axis is the total number of executed programs for interacting with the environment, and the y-axis is the maximum validation return. This demonstrates that our proposed framework has better program sample efficiency and converges to better performance. (b) Inductive generalization performance. We evaluate and report the performance drop in the testing environments with an extended horizon, where the x-axis is the extended horizon length compared to the horizon of the training environments, and the y-axis is the performance drop in percentage. Our proposed framework can inductively generalize to longer horizons without any fine-tuning.

🔼 This figure shows two sub-figures. Sub-figure (a) compares the program sample efficiency of HIPO against other programmatic RL methods by plotting the maximum validation return achieved against the total number of executed programs. It shows that HIPO achieves better sample efficiency and faster convergence. Sub-figure (b) evaluates the inductive generalization capabilities of HIPO by comparing its performance drop in extended horizon testing environments against baselines. It shows that HIPO maintains its performance better than other methods as the horizon extends.

read the caption

Figure 4: (a) Program sample efficiency. The training curves of HIPO and other programmatic RL approaches, where the x-axis is the total number of executed programs for interacting with the environment, and the y-axis is the maximum validation return. This demonstrates that our proposed framework has better program sample efficiency and converges to better performance. (b) Inductive generalization performance. We evaluate and report the performance drop in the testing environments with an extended horizon, where the x-axis is the extended horizon length compared to the horizon of the training environments, and the y-axis is the performance drop in percentage. Our proposed framework can inductively generalize to longer horizons without any fine-tuning.

🔼 This figure illustrates the HIPO framework, which consists of two main stages: (a) retrieving diverse and compatible programmatic options and (b) learning a high-level policy using these options. Stage (a) uses a modified CEM algorithm to find programs with diverse skills, considering compatibility with already selected programs and overall diversity. Stage (b) shows how the high-level policy determines which option to use based on the current state and the current option, to ultimately maximize rewards.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hierarchical Programmatic Option Framework. (a): Retrieving programmatic options. After learning the program embedding space, we propose an advanced search scheme built upon the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) to search programs pm1,..., Pmk, pmk+1 of different skills. While searching for the next program pmk+1, we consider its compatibility with predetermined programs pm1, …, Pmk by randomly sampling a sequence of programs. We also consider the diversity among all programs using the diversity multiplier. (b): Learning High-Level Policy with Programmatic Options

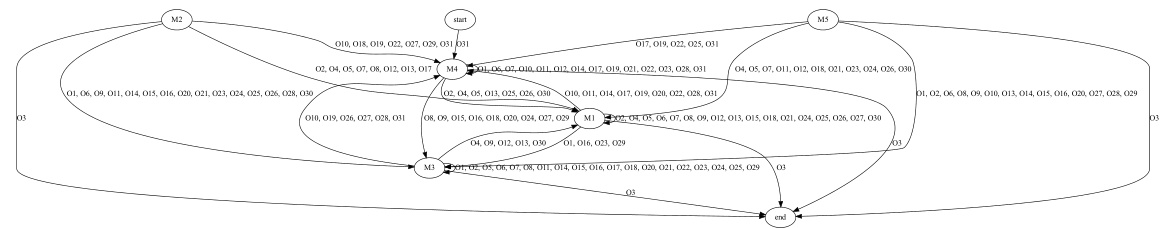

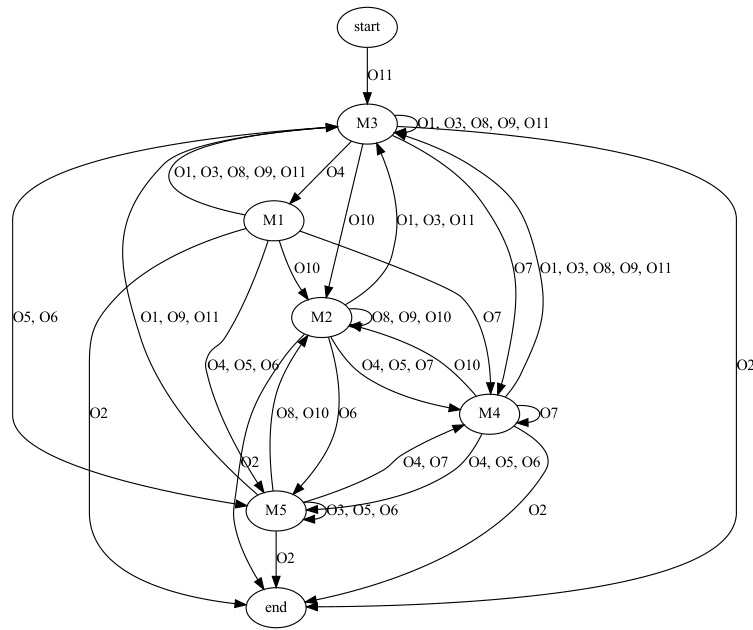

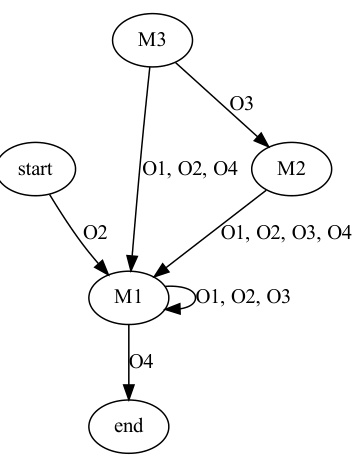

🔼 This figure shows a state machine extracted from the high-level policy of the HIPO framework when applied to the FARMER task. Each node represents a state, and each edge represents a transition between states, labeled with the quantized vector observed from the environment that triggered the transition. The states are further connected to low-level programmatic options (M1-M5) which are human-readable programs that execute actions within the environment. More detail about the specific programs is found in Figure 23. The state machine visualization enhances interpretability, showcasing the high-level policy’s decision-making process in the task.

read the caption

Figure 10: Example of extracted state machine on FARMER. 01 to 031 represent the unique quantized vectors encoded from observations. The corresponding programs of M1 to M5 are displayed in Figure 23.

🔼 This figure shows a state machine extracted from the high-level policy for the FARMER task. Each node represents a state, and each edge represents a transition between states, labeled with the programmatic option selected by the high-level policy. The figure illustrates the flow of the high-level policy’s decisions. The corresponding programs for options M1-M5 are detailed in Figure 23.

read the caption

Figure 10: Example of extracted state machine on FARMER. 01 to 031 represent the unique quantized vectors encoded from observations. The corresponding programs of M1 to M5 are displayed in Figure 23.

🔼 This figure illustrates the HIPO framework, which consists of two main stages: retrieving programmatic options and learning a high-level policy. The first stage (a) uses a search algorithm based on the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) to find a diverse set of programs (options) with different skills. The algorithm considers program compatibility and diversity. The second stage (b) trains a high-level neural network policy to select the appropriate option based on the current state and the last selected option, aiming to maximize the overall reward.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hierarchical Programmatic Option Framework. (a): Retrieving programmatic options. After learning the program embedding space, we propose an advanced search scheme built upon the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) to search programs pm1,..., Pmk, pmk+1 of different skills. While searching for the next program pmk+1, we consider its compatibility with predetermined programs pm1, …, Pmk by randomly sampling a sequence of programs. We also consider the diversity among all programs using the diversity multiplier. (b): Learning High-Level Policy with Programmatic Options.

🔼 This figure shows four example tasks from the KAREL problem set used in the paper. Each task (STAIRCLIMBER, FOURCORNER, TOPOFF, MAZE) is illustrated with three snapshots: a random initial state, an intermediate state, and the goal state. The initial position of the Karel agent and marker locations are randomized for each instance. The details of the problem set are described in Section F of the paper. The figure visually demonstrates the different types of tasks considered, each with varying complexity and goal configurations.

read the caption

Figure 14: Visualization of STAIRCLIMBER, FOURCORNER, TOPOFF, and MAZE in the KAREL problem set presented in Trivedi et al. [74]. For each task, a random initial state, a legitimate internal state, and the ideal end state are shown. In most tasks, the position of markers and the initial location of the Karel agent are randomized. More details of the KAREL problem set can be found in Section F.

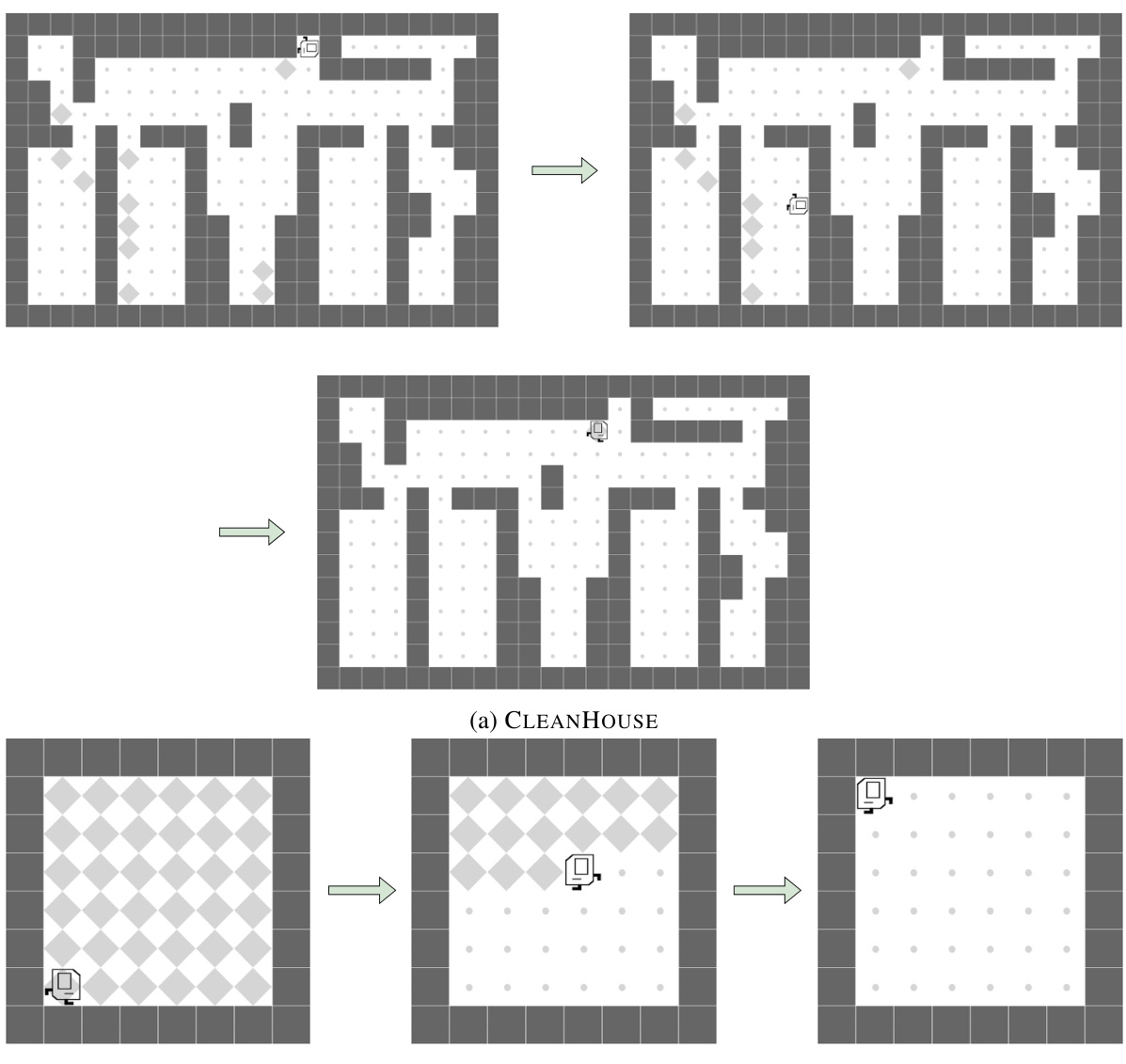

🔼 This figure shows two examples from the KAREL problem set used as a benchmark in the paper. CLEANHOUSE involves collecting scattered markers in a grid world. HARVESTER involves collecting markers from a grid where all cells are initially populated with markers. The figure shows the initial state, an intermediate state, and the goal state for each of the tasks. These are randomly generated states, to avoid bias in the results.

read the caption

Figure 15: Visualization of CLEANHOUSE and HARVESTER in the KAREL problem set presented in Trivedi et al. [74]. For each task, a random initial state, a legitimate internal state, and the ideal end state are shown. More details of the KAREL problem set can be found in Section F.

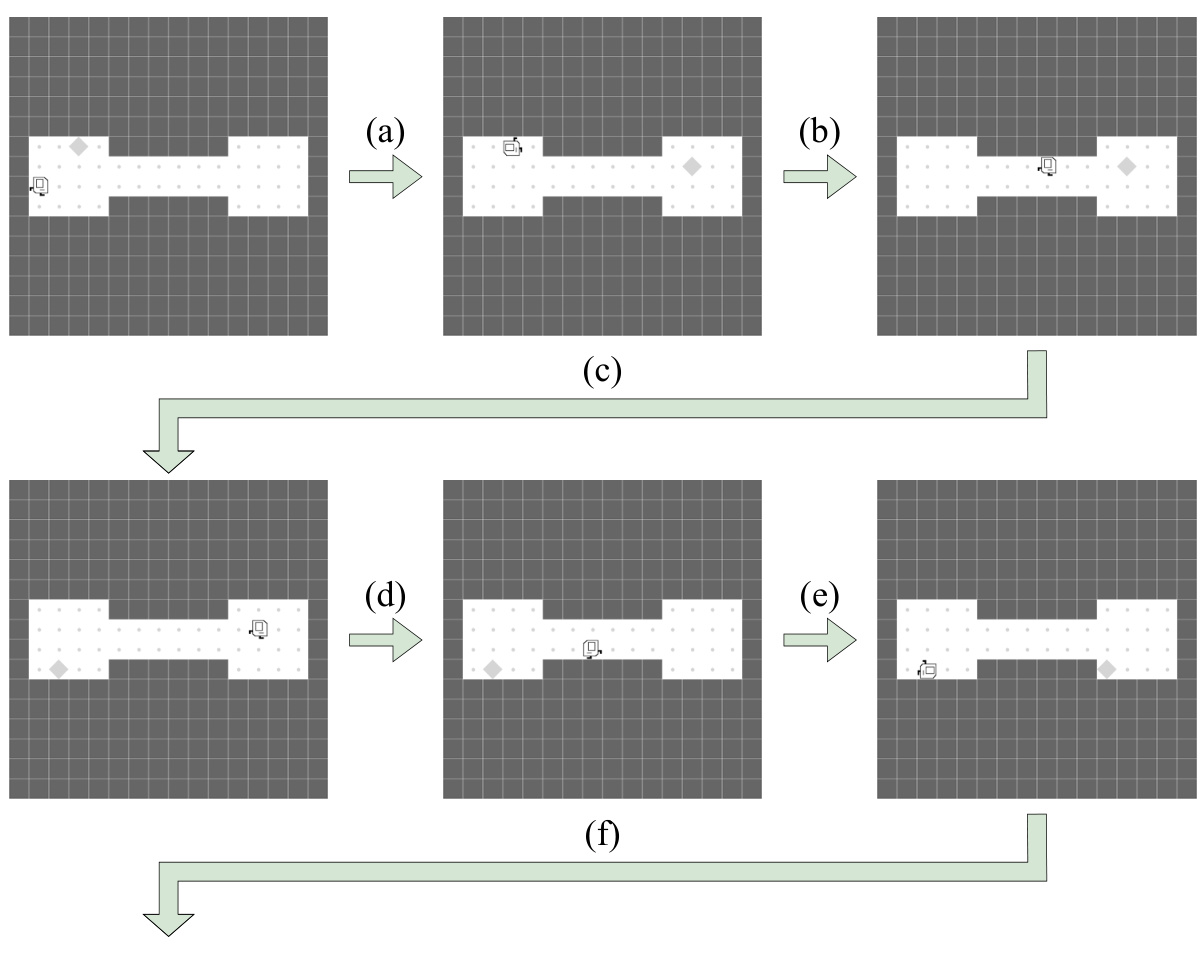

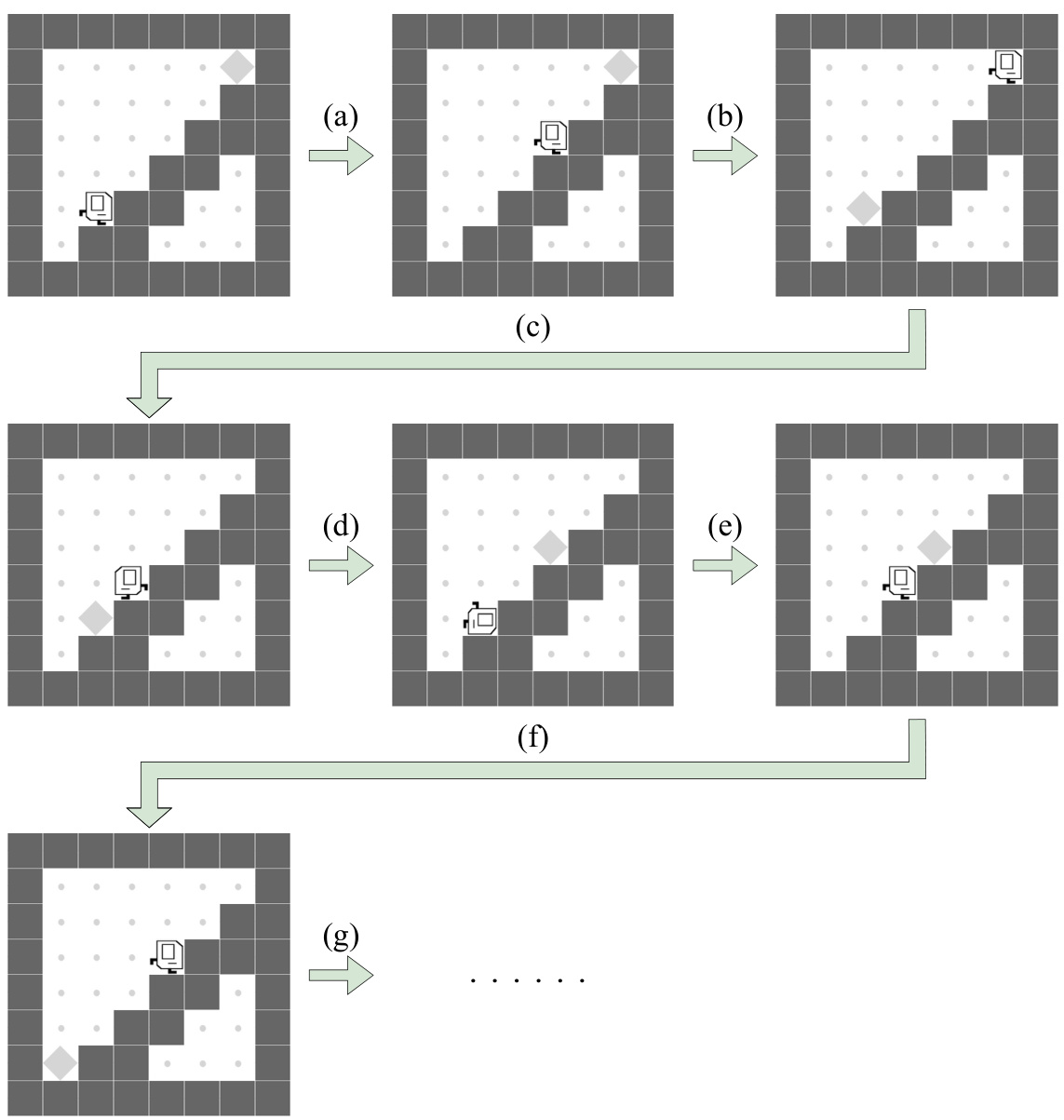

🔼 This figure shows a partial trajectory of the Karel agent in the SEESAW task. The agent moves between two chambers, collecting markers. Each time it collects a marker, a new one appears in the opposite chamber. This demonstrates the repetitive nature of the task, and how the agent’s actions (movement and marker collection) repeat in a cycle.

read the caption

Figure 16: Visualization of SEESAW in the KAREL-LONG problem set. This figure partially illustrates a typical trajectory of the Karel agent during the task SEESAW. (a): Once the Karel agent collects a marker in the left chamber, a new marker appears in the right chamber. (b): The agent must navigate through the central corridor to collect the marker in the right chamber. (c): Once the Karel agent collects a marker in the right chamber, a new marker further appears in the left chamber. (d): Once again, the agent is traversing through the corridor to the left chamber. (e): A new marker appears in the right chamber again after the agent picks up the marker in the left chamber. (f): The agent will move back and forth between the two chambers to collect the emerging markers continuously. Note that the locations of all the emerging markers are randomized. Also, note that we have set the number of emerging markers to 64 during the training phase (i.e., the agent has to pick up 64 markers to fully complete the task.) More details of the task SEESAW can be found in Section H.

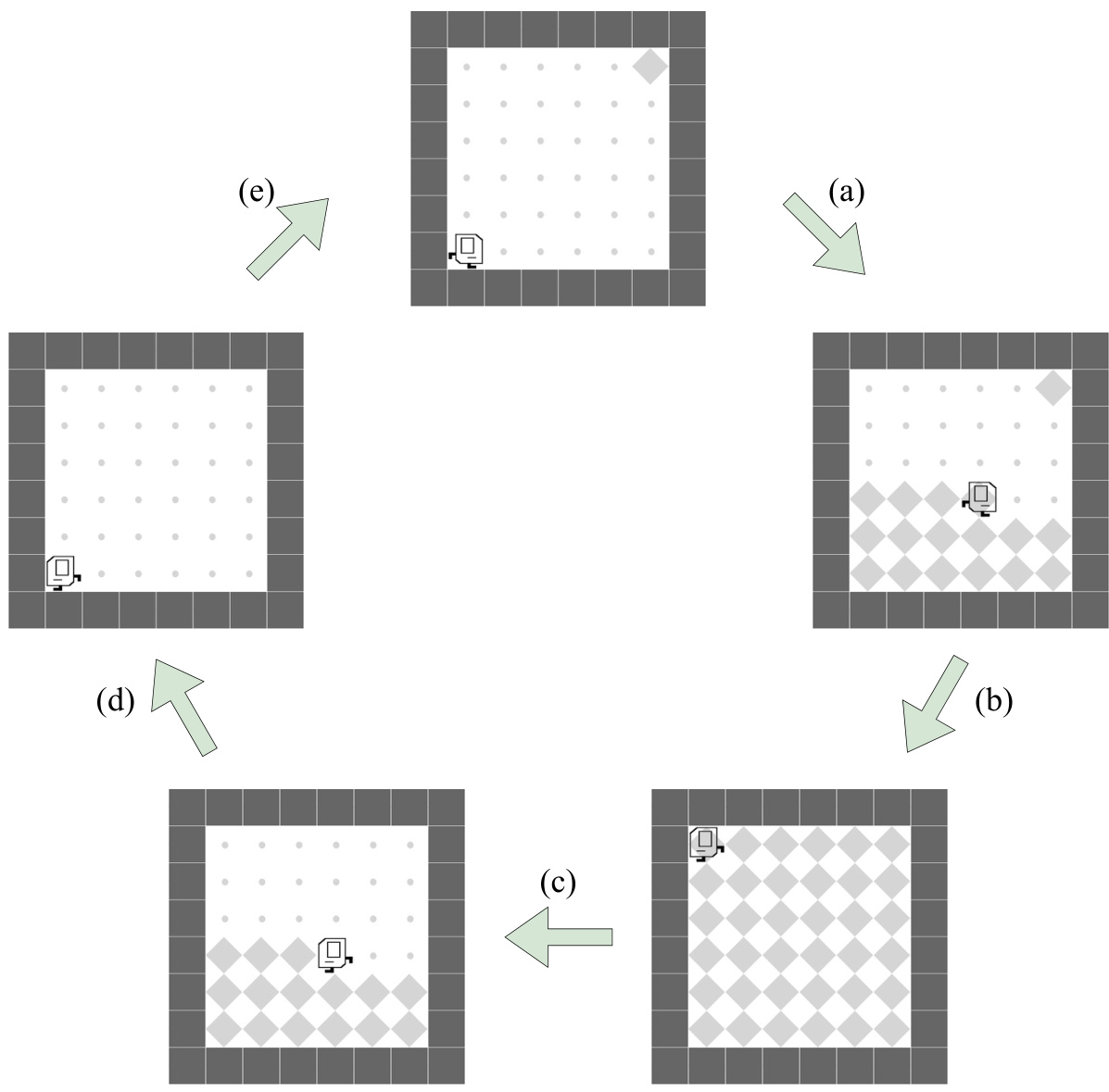

🔼 This figure illustrates a typical trajectory of the Karel agent in the UP-N-DOWN task. The agent repeatedly ascends and descends stairs to collect loads (markers). A new load appears above/below the stairs after the agent collects one, continuing the cycle. The agent is penalized for collecting loads without directly climbing the stairs.

read the caption

Figure 17: Visualization of UP-N-DOWN in the KAREL-LONG problem set. This figure partially illustrates a typical trajectory of the Karel agent during the task UP-N-DOWN. (a): The Karel agent is ascending the stairs to collect a load located above the stairs. Note that the agent can theoretically collect the load without directly climbing up the stairs, but it will receive some penalties for doing so. (b): Once the agent collects the load, a new load appears below the stairs. (c): The agent then descends the stairs to collect a load located below. Note that the agent can theoretically collect the load without directly climbing down the stairs, but it will receive some penalties for doing so. (d): Upon the agent collecting the load, a new load appears above the stairs. (e): The agent once again ascends the stairs to collect a load. (f): A new load appears below the stairs again after the agent collects the load located above. (g): The agent would continue to collect the emerging loads in descend-ascend cycles repeatedly on the stairs. Note that the locations of all the emerging loads are randomly initiated right next to the stairs. The load must appears below/above the stairs after the agent just finished ascending/descending. Also, we have fixed the number of emerging loads to 100 during the training phase (i.e., the agent shall collect 100 loads to complete the task). More details of the task UP-N-DOWN can be found in Section H.

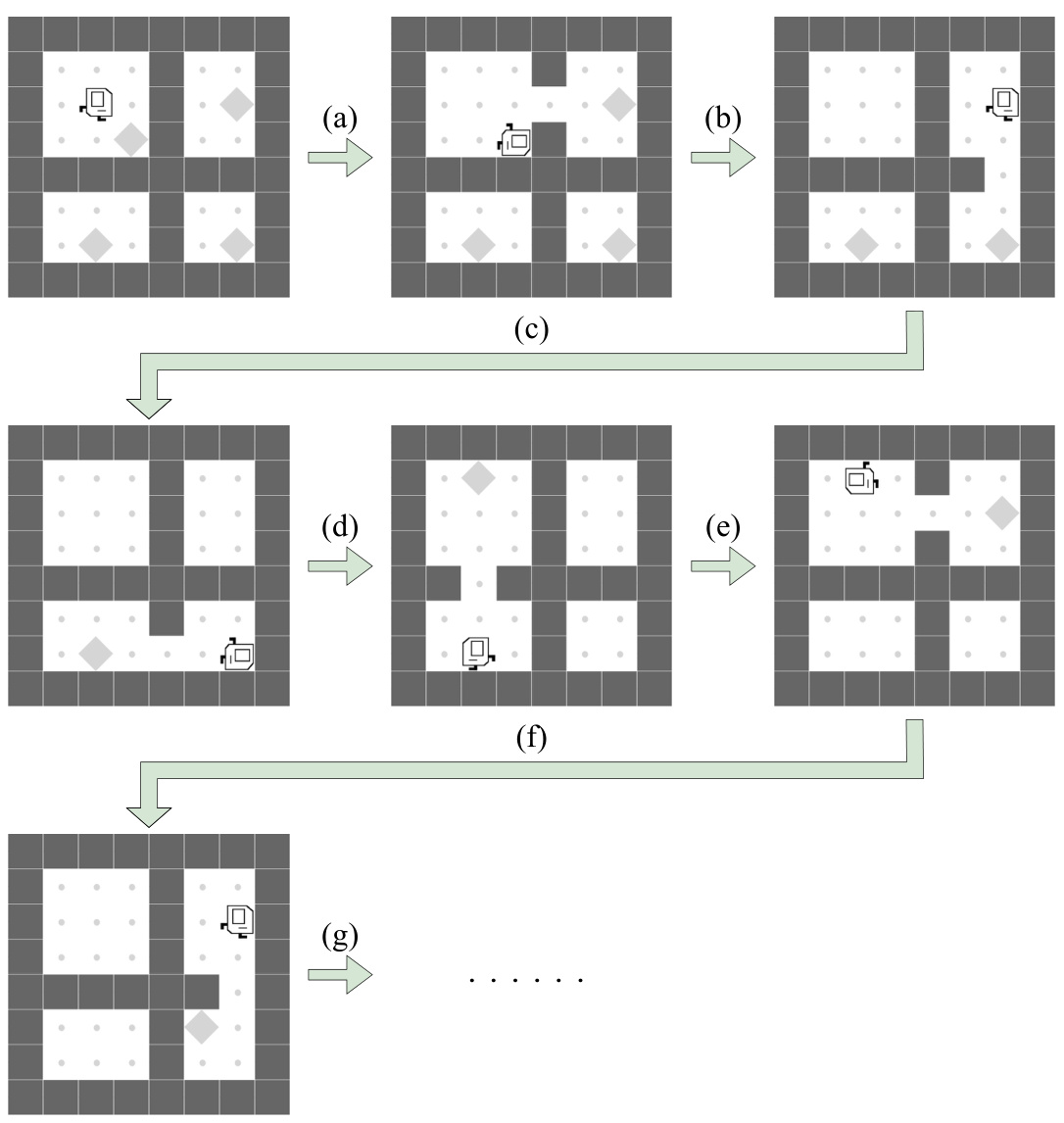

🔼 This figure shows a sample trajectory of an agent executing the INF-HARVESTER task. The agent repeatedly traverses the grid, picking markers. As it does, new markers randomly appear in empty locations. The cycle continues until no markers remain. The figure highlights the dynamic and repetitive nature of the task.

read the caption

Figure 20: Visualization of INF-HARVESTER in the KAREL-LONG problem set. This figure partially illustrates a legitimate trajectory of the Karel agent during the task INF-HARVESTER. (a): The Karel agent picks up markers in the last row. Meanwhile, no new markers are popped out in the last row. (b): The agent turns left and picks up 6 markers in the 7th column while 3 markers appear in 3 previously empty grids in the last row. (c): The agent collects markers in the 8th row while 1 marker appears in a previously empty grid in the 7th column. (d): The agent picks up 6 markers in the 5th column while 2 markers appear in 2 previously empty grids in the 7th column. (e): The agent picks up 2 more markers in the last row while 2 markers appeared in 2 previously empty grids in the 5th column. (f): Since markers appear in previously empty grids based on the emerging probability, the agent will continuously and indefinitely collect markers until none remain and no new markers appear in the environment. The emerging probability has been fixed to 1 during the training phase. More details of the task INF-HARVESTER can be found in Section H.

🔼 This figure shows a partial trajectory of an agent performing the INF-HARVESTER task in the Karel-Long problem set. The agent repeatedly collects markers, and with a certain probability, new markers appear in empty cells. The figure illustrates how the agent’s actions and the environment’s changes cause a progression through the task.

read the caption

Figure 20: Visualization of INF-HARVESTER in the KAREL-LONG problem set. This figure partially illustrates a legitimate trajectory of the Karel agent during the task INF-HARVESTER. (a): The Karel agent picks up markers in the last row. Meanwhile, no new markers are popped out in the last row. (b): The agent turns left and picks up 6 markers in the 7th column while 3 markers appear in 3 previously empty grids in the last row. (c): The agent collects markers in the 8th row while 1 marker appears in a previously empty grid in the 7th column. (d): The agent picks up 6 markers in the 5th column while 2 markers appear in 2 previously empty grids in the 7th column. (e): The agent picks up 2 more markers in the last row while 2 markers appeared in 2 previously empty grids in the 5th column. (f): Since markers appear in previously empty grids based on the emerging probability, the agent will continuously and indefinitely collect markers until none remain and no new markers appear in the environment. The emerging probability has been fixed to during the training phase. More details of the task INF-HARVESTER can be found in Section H.

🔼 This figure shows a partial trajectory of the Karel agent in the SEESAW task. It demonstrates the back-and-forth movement between two chambers, collecting markers. A new marker appears in the opposite chamber after one is collected, creating a continuous cycle. Marker locations are randomized, and the training phase involves collecting 64 markers.

read the caption

Figure 16: Visualization of SEESAW in the KAREL-LONG problem set. This figure partially illustrates a typical trajectory of the Karel agent during the task SEESAW. (a): Once the Karel agent collects a marker in the left chamber, a new marker appears in the right chamber. (b): The agent must navigate through the central corridor to collect the marker in the right chamber. (c): Once the Karel agent collects a marker in the right chamber, a new marker further appears in the left chamber. (d): Once again, the agent is traversing through the corridor to the left chamber. (e): A new marker appears in the right chamber again after the agent picks up the marker in the left chamber. (f): The agent will move back and forth between the two chambers to collect the emerging markers continuously. Note that the locations of all the emerging markers are randomized. Also, note that we have set the number of emerging markers to 64 during the training phase (i.e., the agent has to pick up 64 markers to fully complete the task.) More details of the task SEESAW can be found in Section H.

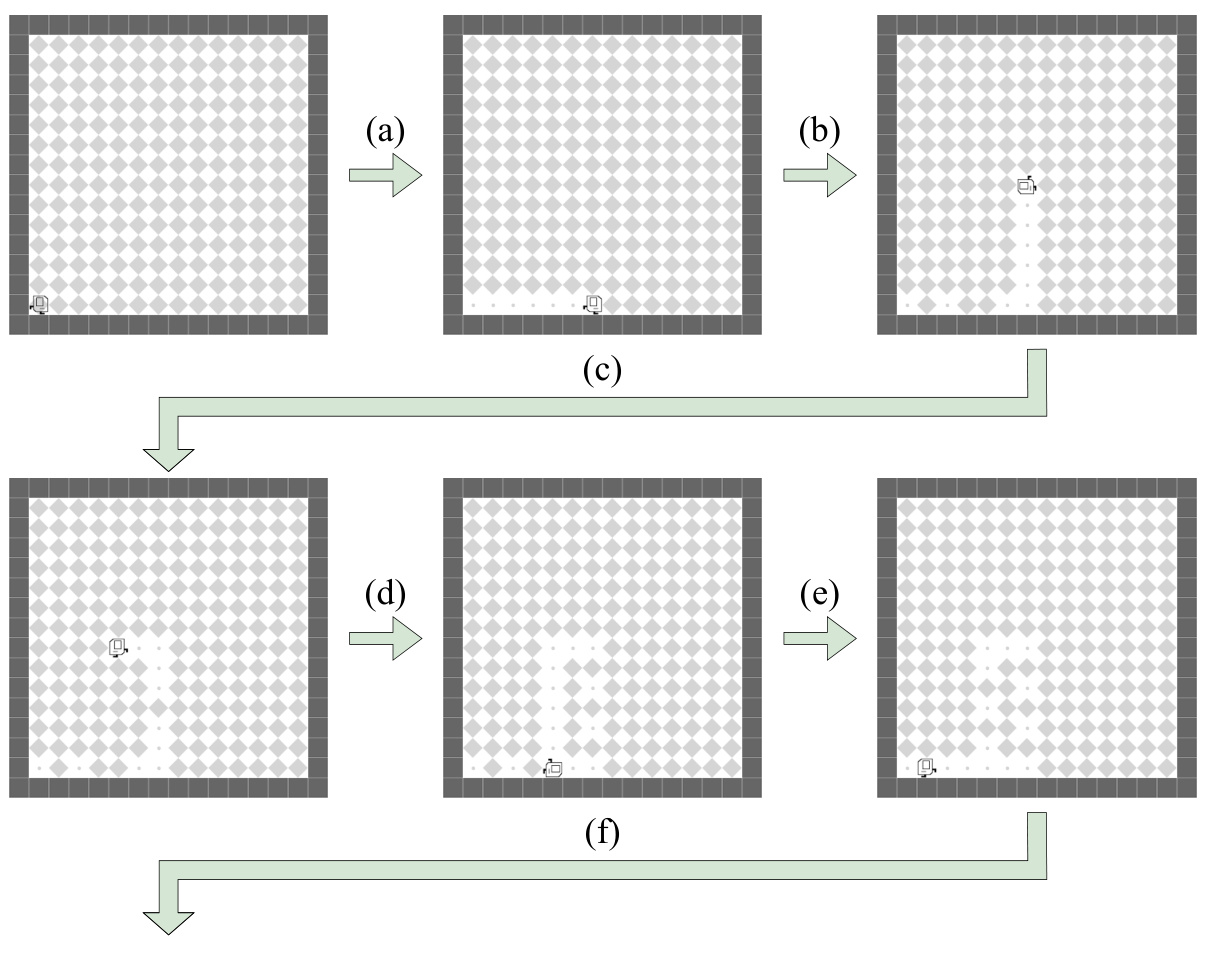

🔼 This figure shows the initial state, intermediate states, and goal state for each of the five tasks in the KAREL-HARD problem set. Each task presents unique challenges and complexities in terms of navigation, marker placement, and goal achievement. The figure serves to visually illustrate the range of scenarios encompassed within this problem set.

read the caption

Figure 21: Visualization of each task in the KAREL-HARD problem set proposed by Liu et al. [46]. For each task, a random initial state, some legitimate internal state(s), and the ideal end state are shown. More details of the KAREL-HARD problem set can be found in Section G.

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed Hierarchical Programmatic Option framework (HIPO). The left panel (a) shows the process of retrieving a diverse set of effective and reusable programmatic options from a program embedding space using an advanced search algorithm based on the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) that considers compatibility and diversity. The right panel (b) shows how a high-level policy, represented by neural networks, learns to select and execute these programmatic options to solve long-horizon RL tasks.

read the caption

Figure 2: Hierarchical Programmatic Option Framework. (a): Retrieving programmatic options. After learning the program embedding space, we propose an advanced search scheme built upon the Cross-Entropy Method (CEM) to search programs pm1,..., Pmk, pmk+1 of different skills. While searching for the next program pmk+1, we consider its compatibility with predetermined programs pm1, …, Pmk by randomly sampling a sequence of programs. We also consider the diversity among all programs using the diversity multiplier. (b): Learning High-Level Policy with Programmatic Options

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the performance results of various methods on the KAREL-LONG tasks. The mean return and standard deviation are calculated across five random seeds. It shows that HIPO, the proposed framework, outperforms other methods by learning a high-level policy that utilizes a set of effective, diverse, and compatible programs.

read the caption

Table 2: KAREL-LONG performance. Mean return and standard deviation of all methods across the KAREL-LONG problem set, evaluated over five random seeds. Our proposed framework achieves the best mean reward across most of the tasks by learning a high-level policy with a set of effective, diverse, and compatible programs.

🔼 This table presents the results of the KAREL-LONG experiments, comparing the performance of different methods on five different tasks that require long sequences of actions. The table shows that the proposed HIPO framework outperforms other methods by learning a high-level policy that uses a set of diverse and compatible programs as options, enabling it to achieve better average returns and lower variance (more consistent performance) across the tasks.

read the caption

Table 2: KAREL-LONG performance. Mean return and standard deviation of all methods across the KAREL-LONG problem set, evaluated over five random seeds. Our proposed framework achieves the best mean reward across most of the tasks by learning a high-level policy with a set of effective, diverse, and compatible programs.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different methods (CEM, CEM+diversity, DRL, LEAPS, HPRL, and HIPO) on the KAREL and KAREL-HARD tasks. The mean return and standard deviation are calculated over five random seeds for each task. The results show that CEM+diversity outperforms the standard CEM algorithm, demonstrating improved effectiveness and stability. Furthermore, the HIPO method outperforms LEAPS and HPRL on most tasks, indicating its superiority in solving these types of problems.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation on KAREL and KAREL-HARD tasks. Mean return and standard deviation of all methods across the KAREL and KAREL-HARD problem set, evaluated over five random seeds. CEM+diversity outperforms CEM with significantly smaller standard deviations across 8 out of 10 tasks, highlighting the effectiveness and stability of CEM+diversity. In addition, HIPO outperforms LEAPS and HPRL on 8 out of 10 tasks.

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating different methods on the KAREL and KAREL-HARD tasks. The mean return and standard deviation are shown for each method across the ten tasks. The results demonstrate that CEM+diversity (a variation of the Cross Entropy Method) significantly improves upon the standard CEM, showing both higher average performance and much lower variance. Furthermore, the Hierarchical Programmatic Option (HIPO) method achieves the best performance across 8 out of 10 tasks compared to LEAPS and HPRL.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation on KAREL and KAREL-HARD tasks. Mean return and standard deviation of all methods across the KAREL and KAREL-HARD problem set, evaluated over five random seeds. CEM+diversity outperforms CEM with significantly smaller standard deviations across 8 out of 10 tasks, highlighting the effectiveness and stability of CEM+diversity. In addition, HIPO outperforms LEAPS and HPRL on 8 out of 10 tasks.

🔼 This table presents the results of the KAREL and KAREL-HARD tasks, comparing the performance of different methods, including CEM, CEM+diversity, DRL, LEAPS, HPRL, and HIPO. The table shows the mean return and standard deviation for each method across ten tasks, averaged over five random seeds. The results demonstrate that CEM+diversity outperforms the standard CEM approach, and HIPO outperforms LEAPS and HPRL in most tasks. This highlights the effectiveness and stability of the CEM+diversity method and the superiority of the proposed HIPO framework.

read the caption

Table 1: Evaluation on KAREL and KAREL-HARD tasks. Mean return and standard deviation of all methods across the KAREL and KAREL-HARD problem set, evaluated over five random seeds. CEM+diversity outperforms CEM with significantly smaller standard deviations across 8 out of 10 tasks, highlighting the effectiveness and stability of CEM+diversity. In addition, HIPO outperforms LEAPS and HPRL on 8 out of 10 tasks.

Full paper#