TL;DR#

Mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) solvers use strong branching (SB) to efficiently explore the solution space, but SB is computationally expensive. This research investigates using Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to approximate SB. Prior work used simple message-passing GNNs (MP-GNNs) which often worked well empirically but lacked a strong theoretical basis.

This paper introduces the concept of “MP-tractability” – a characteristic of MILPs that makes them suitable for accurate approximation by MP-GNNs. The authors then show that MP-GNNs can accurately approximate SB only for MP-tractable problems. However, for non-MP-tractable MILPs, the authors demonstrate that more sophisticated GNN structures, specifically higher-order GNNs (2-FGNNs), can overcome the limitations of MP-GNNs and provide a universal approximation of SB for all MILPs.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) and graph neural networks (GNNs). It provides a theoretical understanding of GNNs’ capacity to approximate strong branching, a computationally expensive but crucial heuristic in MILP solvers. This bridges the gap between empirical successes and theoretical foundations, paving the way for more efficient and theoretically sound GNN-based MILP solvers. The paper’s findings open new avenues for research, including the exploration of higher-order GNNs and a deeper understanding of MP-tractability.

Visual Insights#

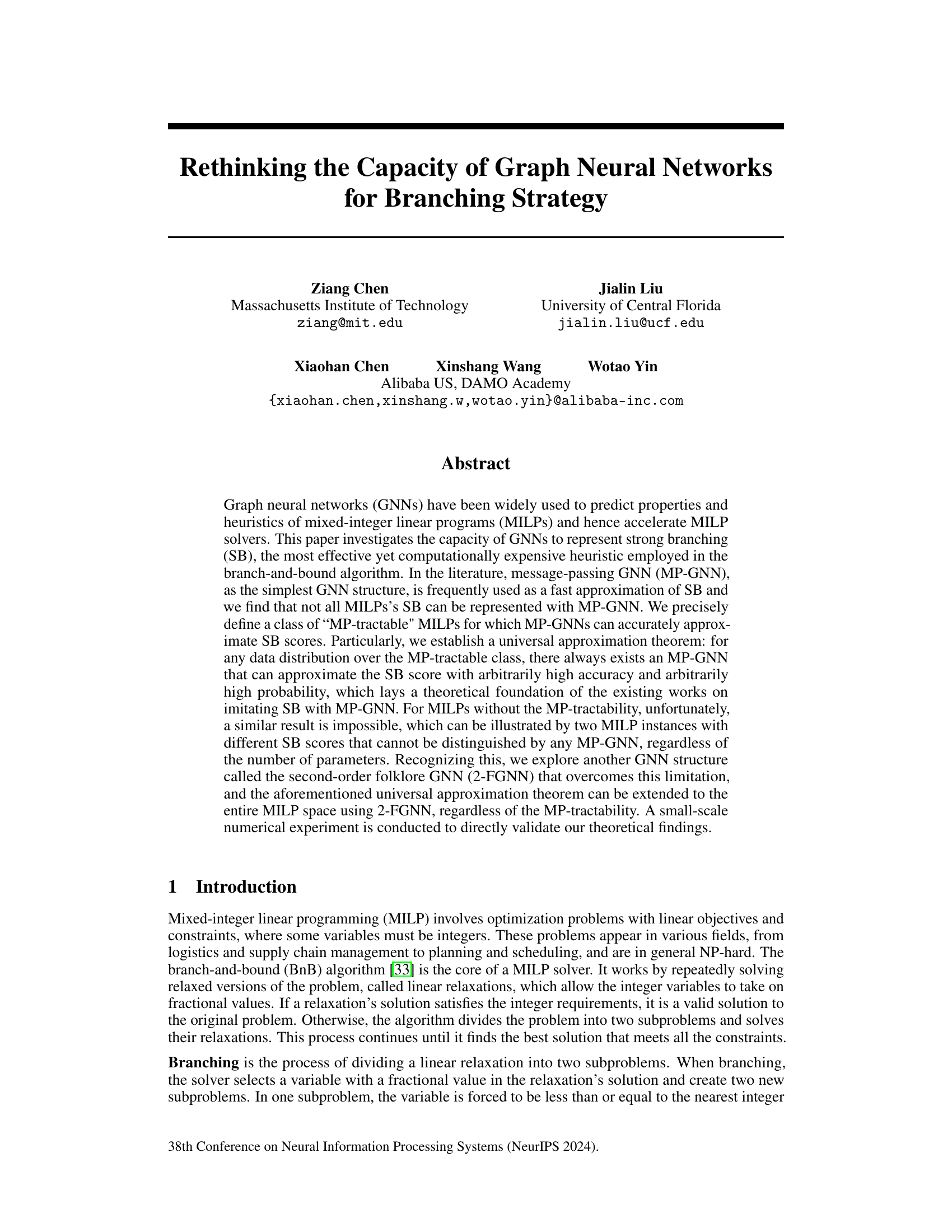

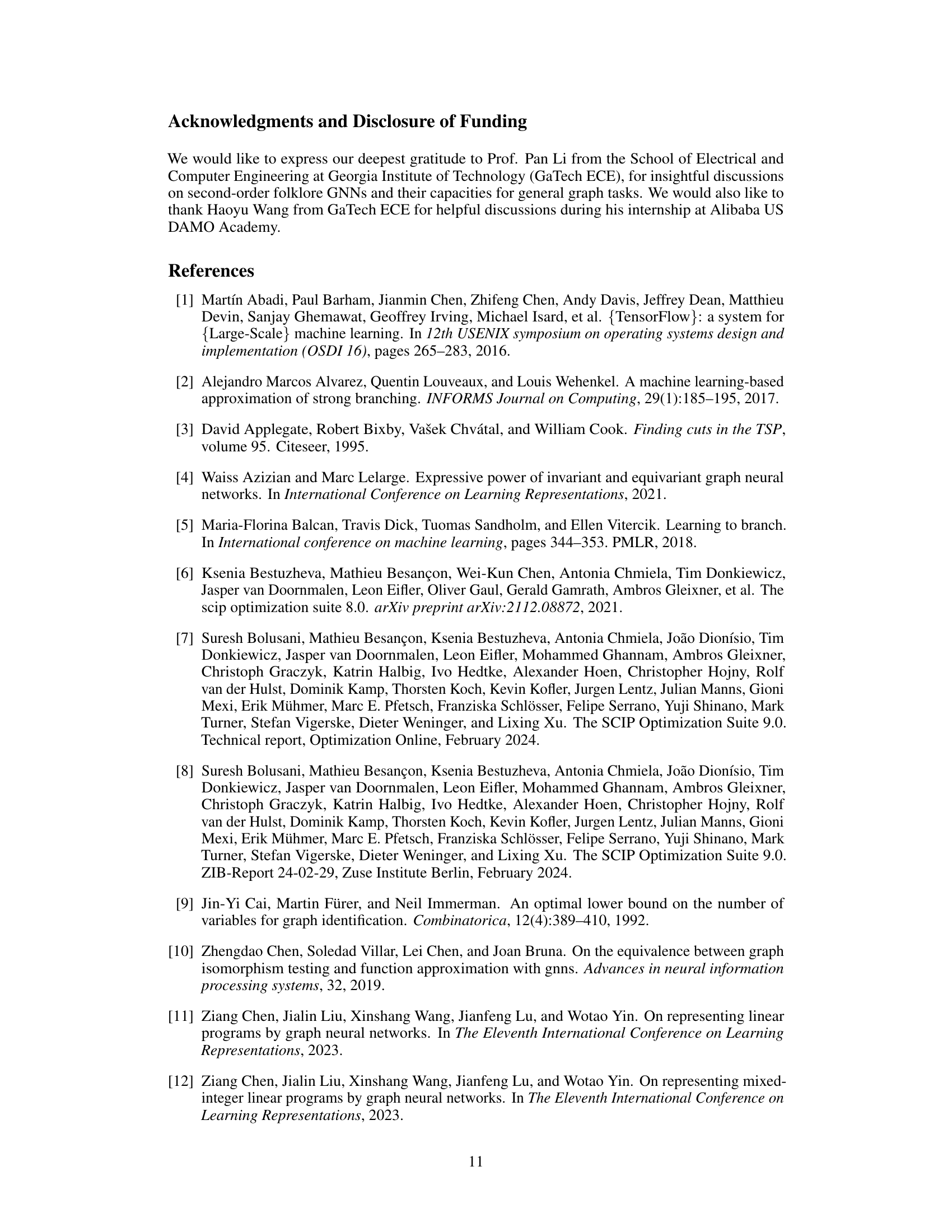

🔼 This figure illustrates how a Mixed Integer Linear Program (MILP) problem can be represented as a graph. The MILP example shows an objective function to minimize and linear constraints involving three variables (x1, x2, x3), with some variables restricted to integer values. The corresponding graph representation is shown, using a bipartite graph structure with constraint nodes (U1, U2) and variable nodes (W1, W2, W3). Edges connect constraint and variable nodes where the corresponding coefficient in the MILP’s constraint matrix is non-zero. The graph nodes are labeled with features relevant to the MILP’s constraints and variables (e.g., coefficients, bounds, integer constraints). This graph representation is crucial for applying Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to solve or analyze MILP problems, as detailed in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 1: An illustrative example of MILP and its graph representation.

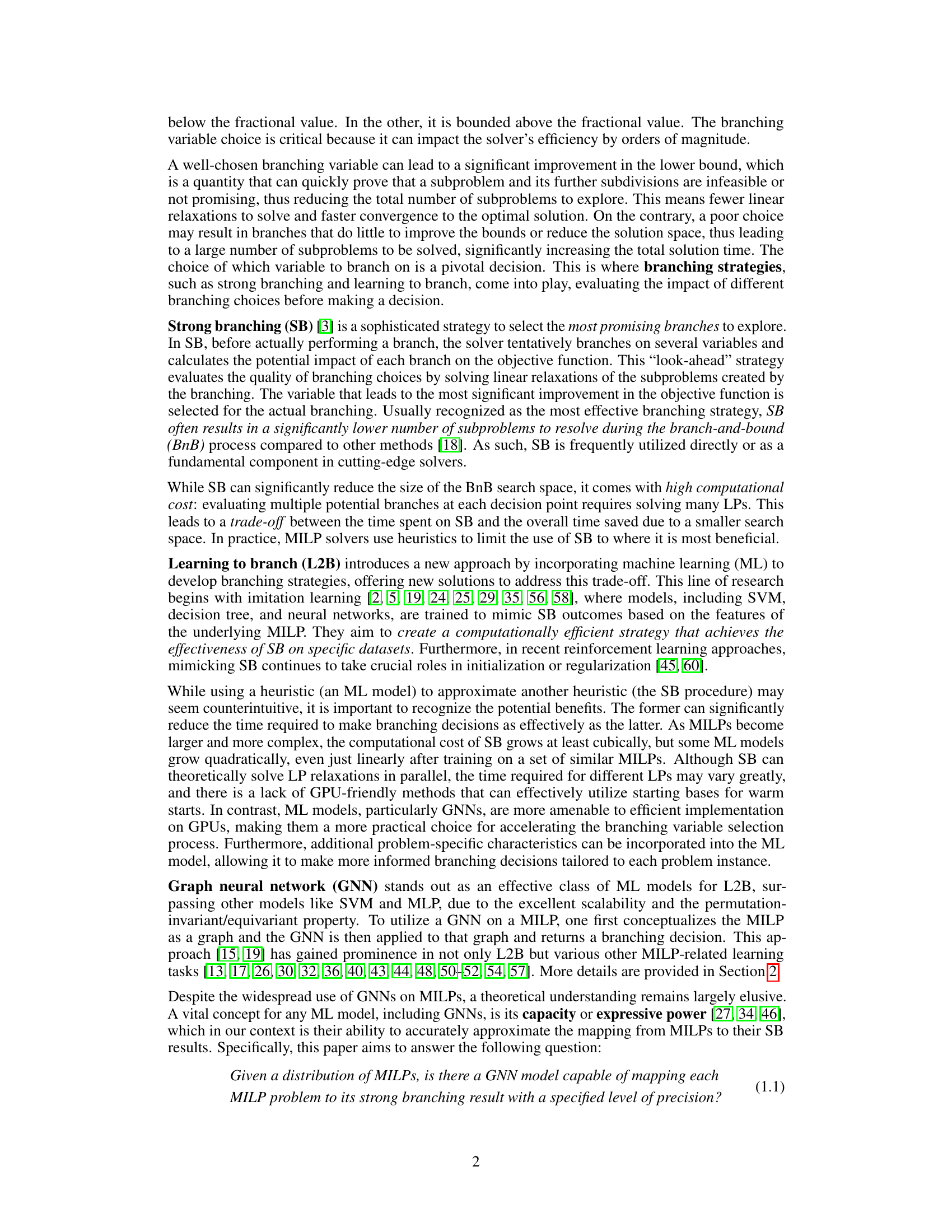

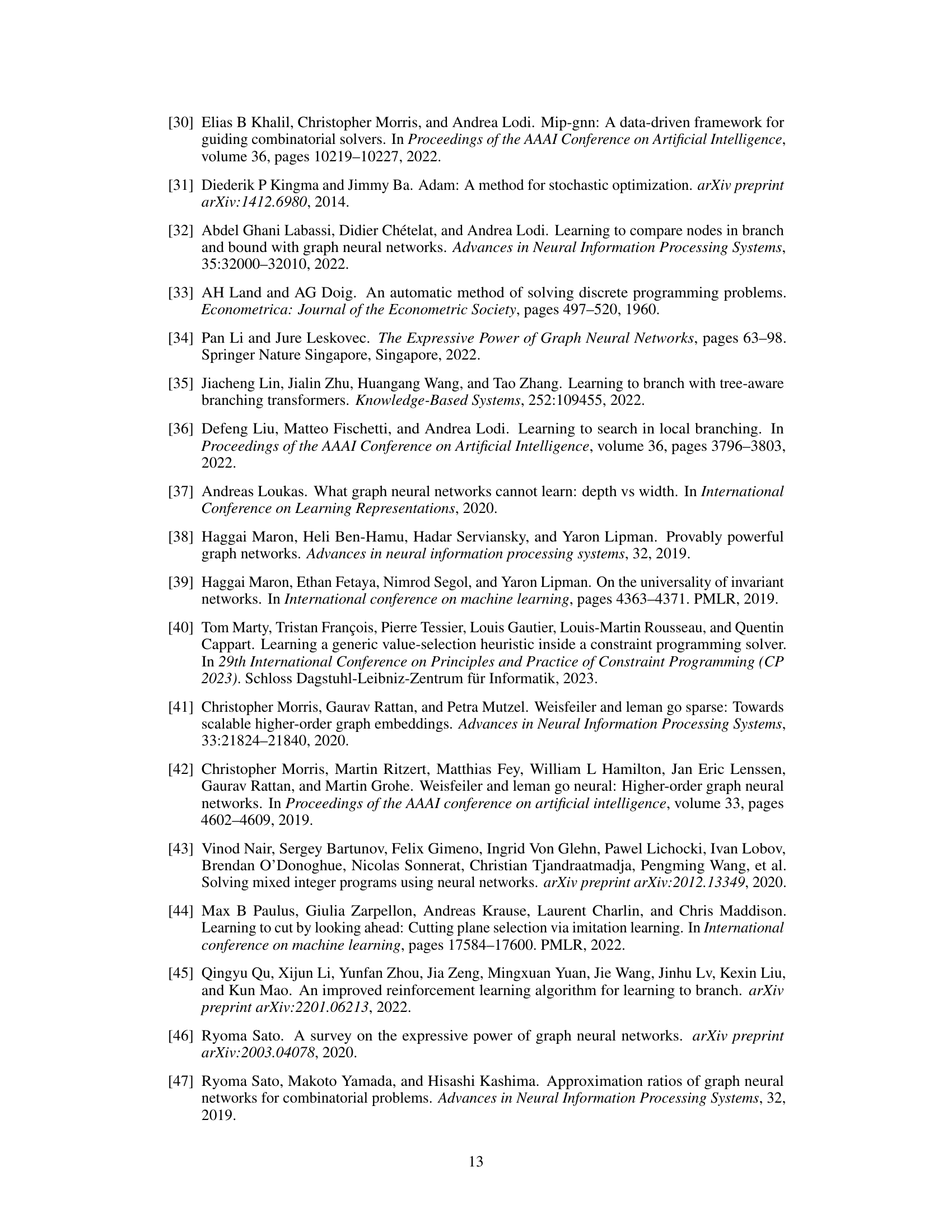

🔼 This table shows the number of training epochs needed to achieve a training error of 10-6 and 10-12 for a 2-FGNN model with different embedding sizes (64, 128, 256, 512, 1024, 2048). It demonstrates the impact of embedding size on training efficiency, showing that larger embedding sizes initially lead to faster convergence but that the gains eventually level off.

read the caption

Table 1: Epochs required to reach specified errors with varying embedding sizes for 2-FGNN.

In-depth insights#

GNN Capacity Limits#

The capacity of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) in approximating strong branching (SB) for Mixed-Integer Linear Programs (MILPs) is explored. Message-passing GNNs (MP-GNNs), while frequently used, have limitations. They can accurately approximate SB only for a subset of MILPs termed “MP-tractable.” This limitation stems from the inherent expressiveness of MP-GNNs, which cannot fully capture the complex relationships in all MILPs. A theoretical result demonstrates the existence of MP-GNNs that can approximate SB scores arbitrarily well within the MP-tractable class. However, a counter-example proves that MP-GNNs cannot universally represent SB across all MILPs. This motivates the investigation of more powerful architectures. Second-order folklore GNNs (2-FGNNs) are shown to overcome this limitation, possessing the capacity to approximate SB for any MILP, regardless of MP-tractability. The findings highlight the crucial role of GNN architecture in determining their capacity to effectively emulate SB, a computationally expensive MILP heuristic. Practical implications suggest assessing MP-tractability before deploying MP-GNNs for SB approximation, and employing 2-FGNNs when MP-tractability is absent or uncertain.

MP-GNN Tractability#

MP-GNN tractability, a concept central to the paper, explores the limitations of using message-passing graph neural networks (MP-GNNs) to approximate strong branching (SB) in mixed-integer linear programs (MILPs). The core idea revolves around the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) test, a graph isomorphism test used to assess MP-GNN expressiveness. The paper defines a class of ‘MP-tractable’ MILPs where the WL test’s partition of the MILP graph results in submatrices with identical entries. This characteristic allows MP-GNNs to accurately approximate SB scores within this class, as proven by a universal approximation theorem. However, the paper demonstrates the fundamental limitation that MP-GNNs cannot universally represent SB scores for all MILPs; they fail for ‘MP-intractable’ instances. These intractable cases highlight the inherent limitations of MP-GNNs’ expressive power in capturing the complex relationships within MILP structures, which is critical for accurate SB score prediction. This limitation motivates the exploration of more powerful GNN architectures, such as second-order folklore GNNs (2-FGNNs), that overcome the MP-tractability constraint and achieve universal approximation.

2-FGNN Expressivity#

The concept of “2-FGNN Expressivity” centers on the capacity of second-order folklore graph neural networks (2-FGNNs) to represent the complex relationships inherent in Mixed Integer Linear Programs (MILPs). Standard message-passing GNNs (MP-GNNs) struggle with certain MILPs, failing to accurately capture the Strong Branching (SB) scores. 2-FGNNs, however, offer a significant advantage by operating on pairs of nodes, rather than individual nodes, thus enabling them to capture higher-order relationships and overcome the limitations of MP-GNNs. This enhanced expressiveness is theoretically grounded and empirically validated, demonstrating the ability of 2-FGNNs to approximate SB scores effectively across a broader range of MILPs, even those previously considered intractable for MP-GNNs. This increased capacity comes with a computational cost, as 2-FGNNs require more resources, but the theoretical foundation for their superior performance is well-established, making them a promising avenue for improving the efficiency of MILP solvers.

SB Approximation#

Strong Branching (SB) is a crucial, yet computationally expensive, technique in Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) solvers. Approximating SB efficiently is critical for improving solver performance, especially for large-scale problems. This research explores the capabilities of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to approximate SB, investigating their capacity to learn the complex relationships inherent in MILPs and map them to SB scores. The study highlights a trade-off between the complexity of the GNN architecture and its expressive power. Simpler MP-GNNs show limitations, accurately approximating SB scores only for a specific class of ‘MP-tractable’ MILPs. This limitation is rigorously proven, highlighting fundamental limitations in their representational capacity. However, more expressive higher-order GNNs, such as 2-FGNNs, demonstrate significantly enhanced capacity, achieving universal approximation of SB scores across all MILP instances. This finding underscores the importance of exploring more sophisticated GNN architectures for effective SB approximation in MILP solvers, balancing the advantages of greater expressive power with potential increases in computational cost.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical analysis to broader classes of MILPs beyond the MP-tractable subset is crucial, potentially investigating the capacity of even higher-order GNNs or alternative architectures. Empirical studies on larger-scale datasets are also needed to fully evaluate the scalability and practical effectiveness of the proposed GNN approaches for strong branching approximation. The computational cost of higher-order GNNs presents a challenge, necessitating research into more efficient training and inference strategies, possibly leveraging techniques such as sparsity or locality. Furthermore, a detailed investigation of the relationship between GNN architecture, expressive power, and the complexity of the MILP problem would provide valuable insights. Finally, exploring the integration of these GNN-based branching strategies with other cutting-edge MILP solver techniques, and testing their efficacy on diverse real-world applications, will be important to ascertain the true impact and potential of this research.

More visual insights#

More on figures

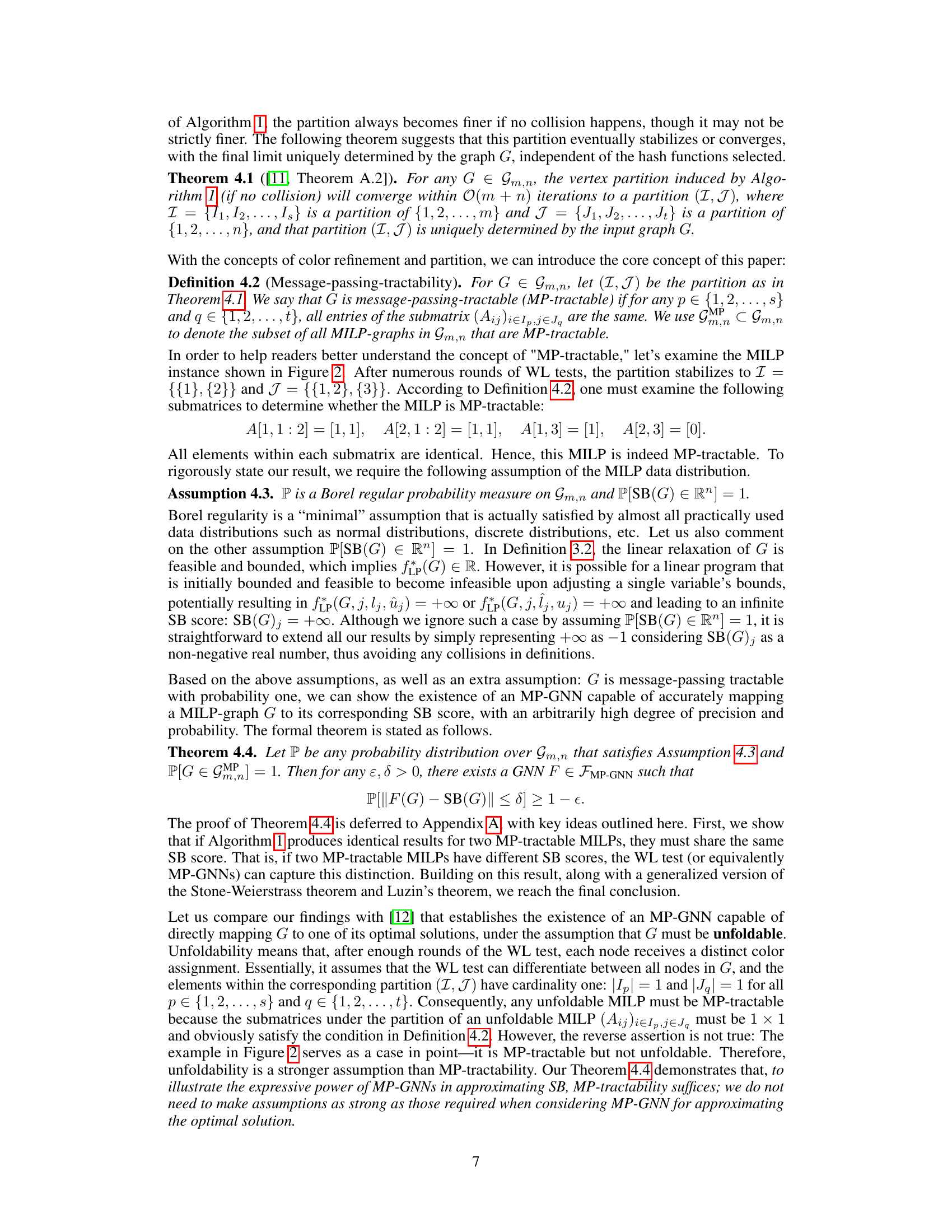

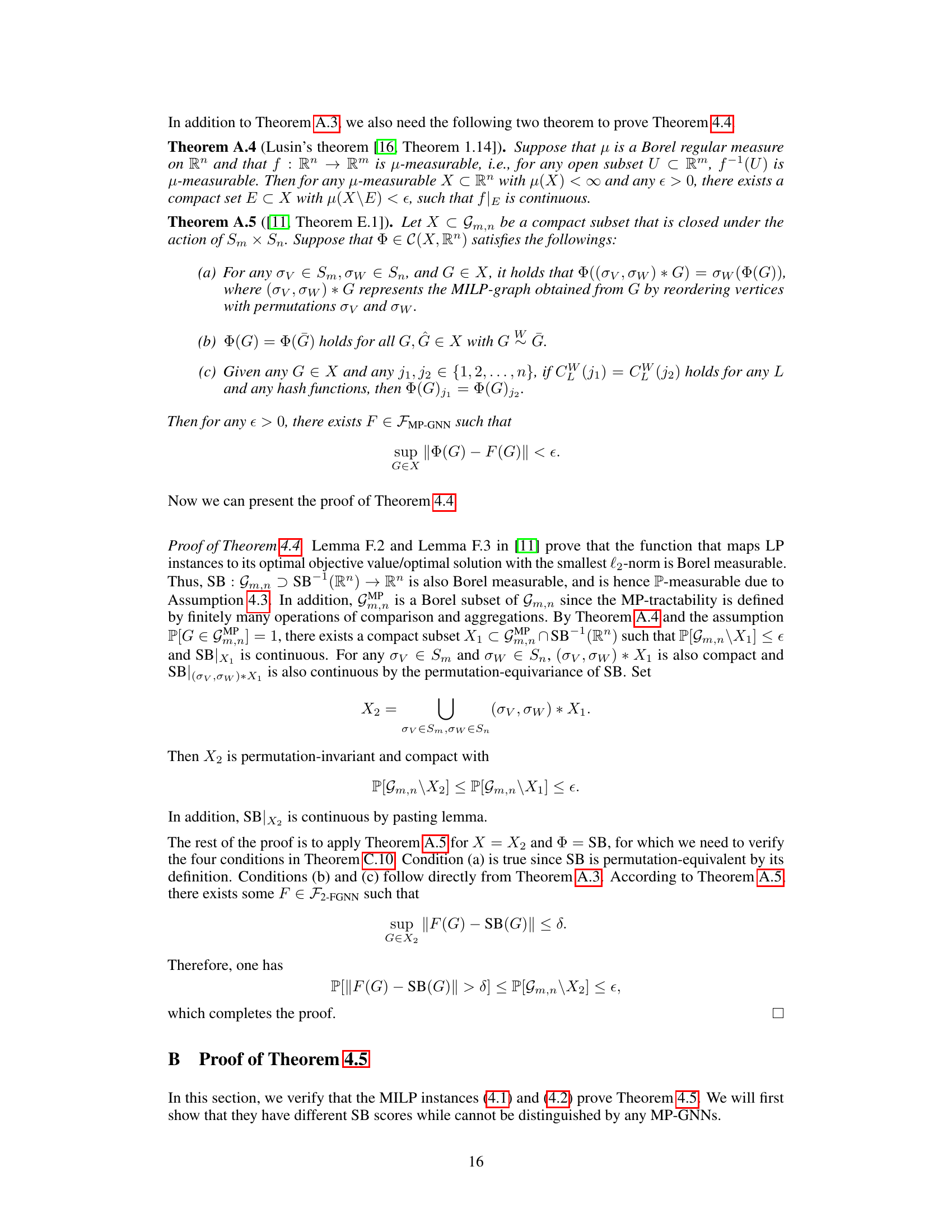

🔼 This figure illustrates the Weisfeiler-Lehman (WL) test, a graph isomorphism test, applied to a Mixed Integer Linear Program (MILP) represented as a graph. The initial state shows all nodes with the same color. After one iteration of the WL test, nodes are recolored based on their neighbors’ colors, resulting in a refined partitioning of the graph. The final partition, stable after further iterations, is shown, demonstrating how the WL test can differentiate nodes based on their structural relationships within the graph.

read the caption

Figure 2: An illustrative example of color refinement and partitions. Initially, all variables share a common color due to their identical node attributes, as do the constraint nodes. After a round of the WL test, x1 and x2 retain their shared color, while x3 is assigned a distinct color, as it connects solely to the first constraint, unlike x1 and x2. Similarly, the colors of the two constraints can also be differentiated. Finally, this partition stabilizes, resulting in I = {{1},{2}}, J = {{1,2}, {3}}.

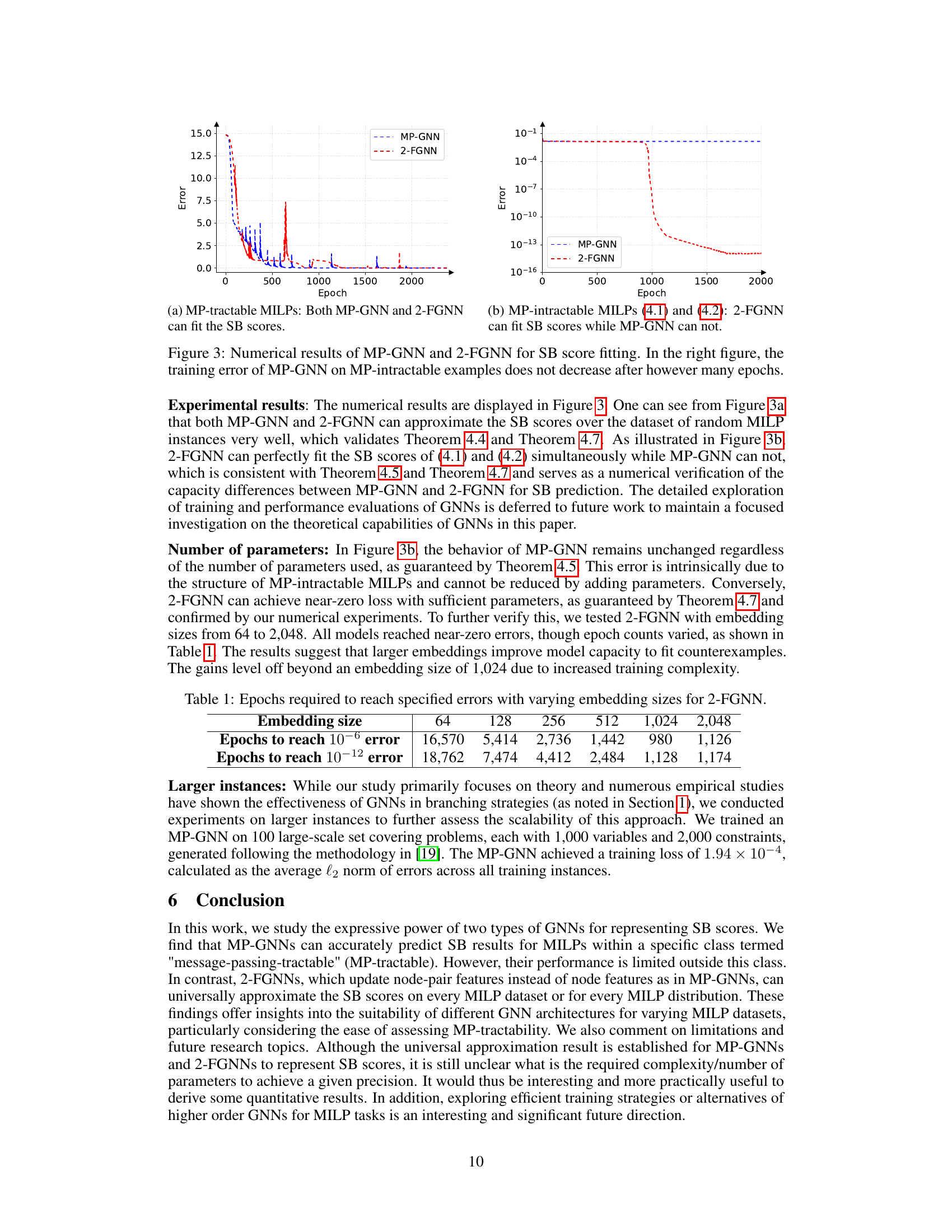

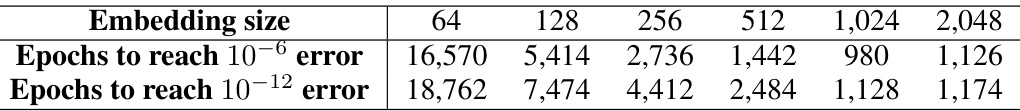

🔼 This figure shows the training error curves for both MP-GNN and 2-FGNN models on two different datasets: one containing MP-tractable MILPs and the other containing two MP-intractable MILPs. The plot on the left demonstrates that both models can effectively fit the SB scores of the MP-tractable dataset, while the plot on the right illustrates that only the 2-FGNN model is capable of fitting the SB scores of the MP-intractable dataset. The MP-GNN model shows no improvement in its training error even after many training epochs.

read the caption

Figure 3: Numerical results of MP-GNN and 2-FGNN for SB score fitting. In the right figure, the training error of MP-GNN on MP-intractable examples does not decrease after however many epochs.

🔼 This figure shows the training error curves for both MP-GNN and 2-FGNN models when training on two different datasets: one with MP-tractable MILPs and the other with MP-intractable MILPs. The left plot demonstrates that both models effectively learn to approximate strong branching (SB) scores on MP-tractable data, achieving low training errors. In contrast, the right plot shows that the MP-GNN fails to reduce training error on MP-intractable data, while the 2-FGNN still successfully learns to approximate SB scores. This illustrates the theoretical findings of the paper about the limitations of MP-GNNs and the capacity of 2-FGNNs for approximating SB.

read the caption

Figure 3: Numerical results of MP-GNN and 2-FGNN for SB score fitting. In the right figure, the training error of MP-GNN on MP-intractable examples does not decrease after however many epochs.

Full paper#