TL;DR#

Many machine learning models struggle when the data distribution shifts, especially over time. Current test-time adaptation (TTA) methods aim to fix this by adjusting the model when new data arrives, but they haven’t been tested thoroughly in scenarios where environments change and then repeat. This paper introduces a “recurring TTA” setting to examine this challenge.

The researchers found that existing TTA methods often fail in this recurring setting, and the error gets worse over time. To solve this, they propose a new method called Persistent TTA (PeTTA). PeTTA continuously monitors the model’s performance and adjusts its adaptation strategy to prevent it from collapsing. Experiments show that PeTTA is significantly better than existing methods in handling long-term adaptation challenges with recurring environments.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it addresses a critical weakness in existing test-time adaptation (TTA) methods: their inability to maintain adaptability over extended periods with recurring environments. By introducing the concept of recurring TTA and proposing a novel persistent TTA (PeTTA) method, it highlights a significant challenge and offers a promising solution for building more robust and reliable AI systems that are better suited to real-world applications.

Visual Insights#

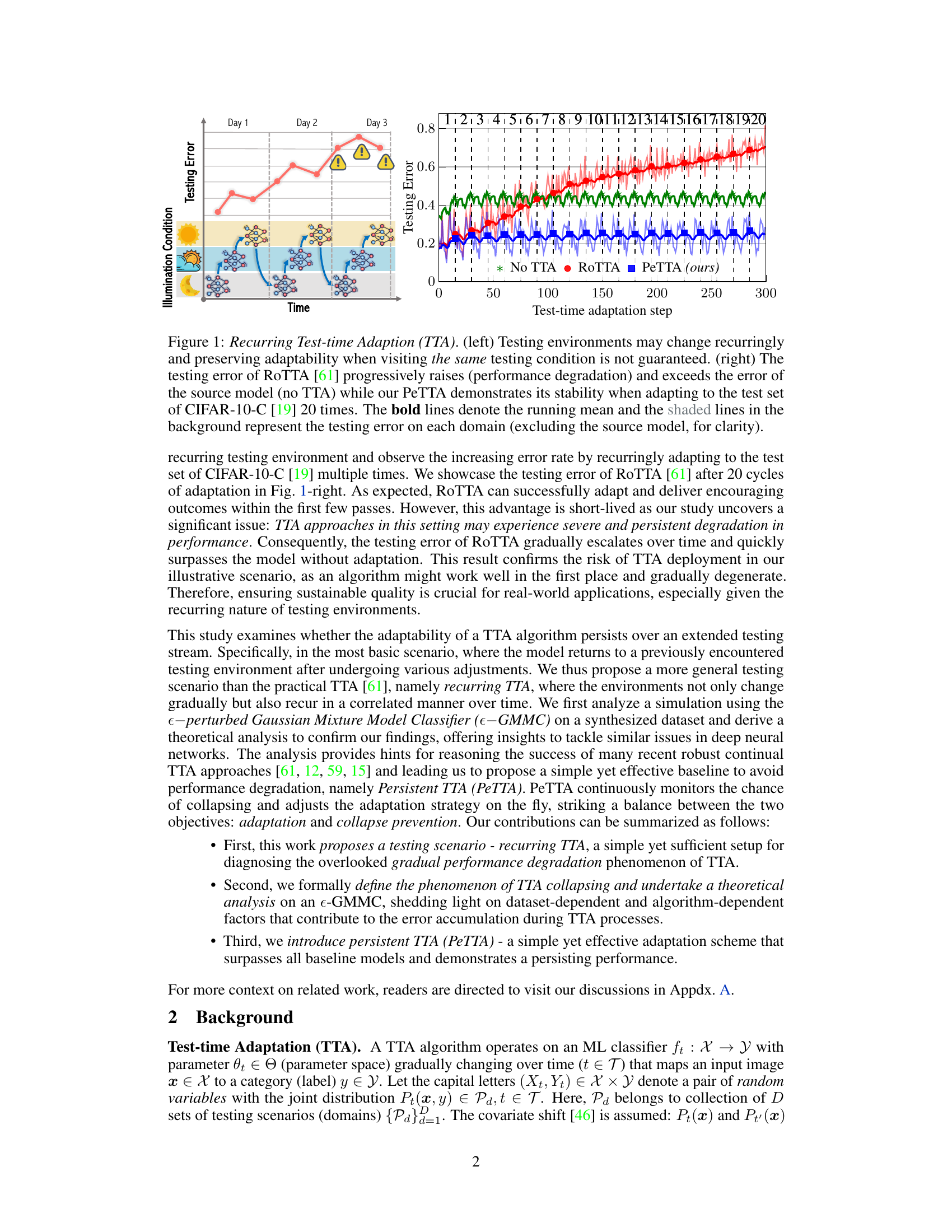

🔼 The left panel shows a recurring test-time adaptation scenario where the testing environments change recurringly, illustrating the challenge of maintaining adaptability when encountering the same testing condition multiple times. The right panel displays the testing error curves for three methods: (1) No TTA (no test-time adaptation), (2) RoTTA (a state-of-the-art recurring test-time adaptation method), and (3) PeTTA (the proposed method). The plot demonstrates that RoTTA’s performance degrades over time, while PeTTA maintains stability.

read the caption

Figure 1: Recurring Test-time Adaption (TTA). (left) Testing environments may change recurringly and preserving adaptability when visiting the same testing condition is not guaranteed. (right) The testing error of RoTTA [61] progressively raises (performance degradation) and exceeds the error of the source model (no TTA) while our PeTTA demonstrates its stability when adapting to the test set of CIFAR-10-C [19] 20 times. The bold lines denote the running mean and the shaded lines in the background represent the testing error on each domain (excluding the source model, for clarity).

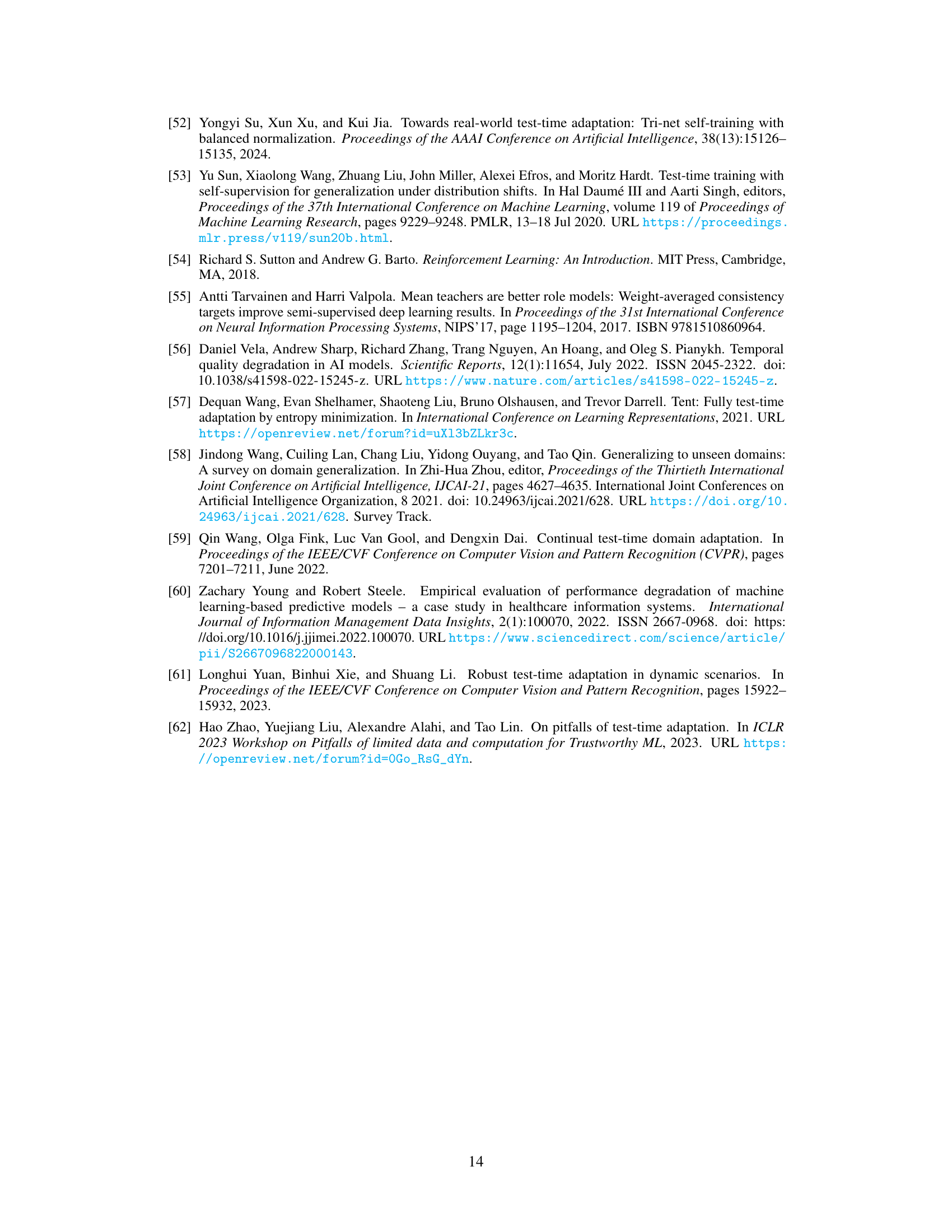

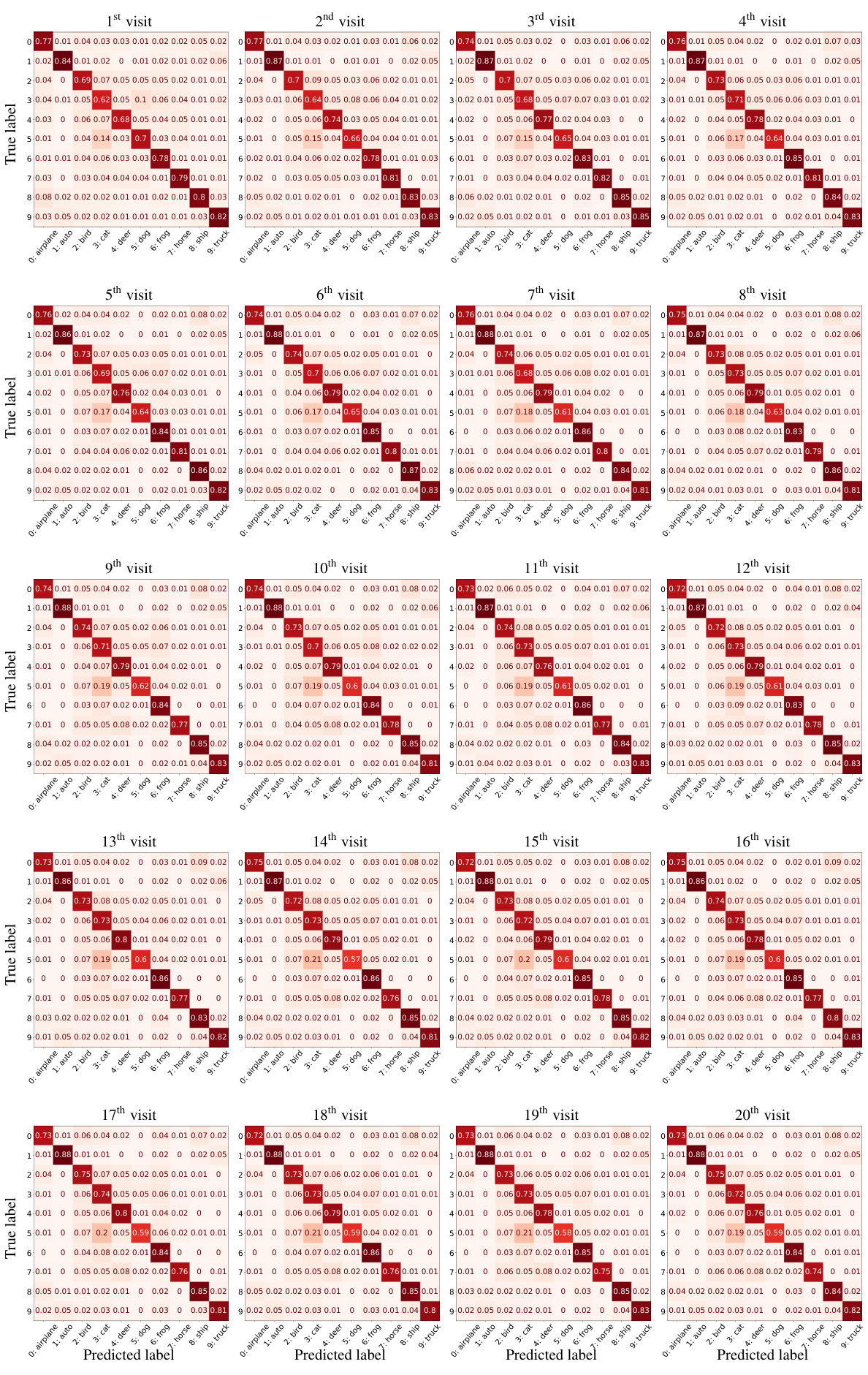

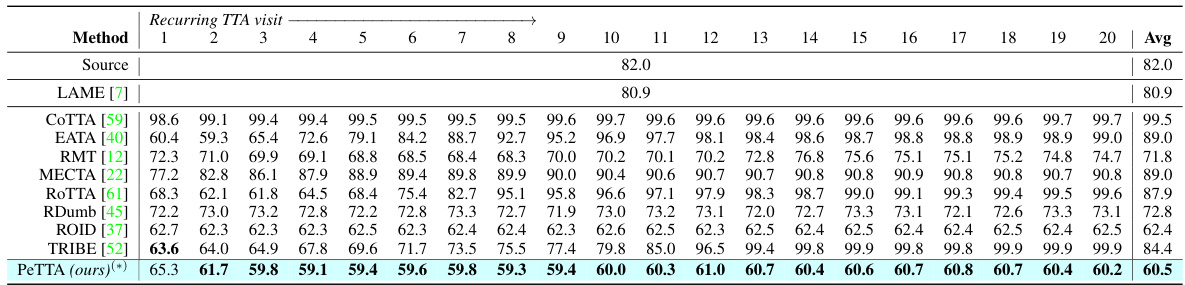

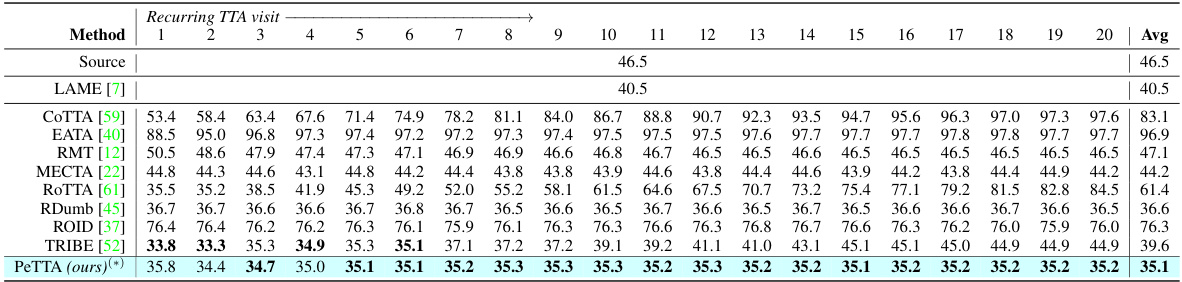

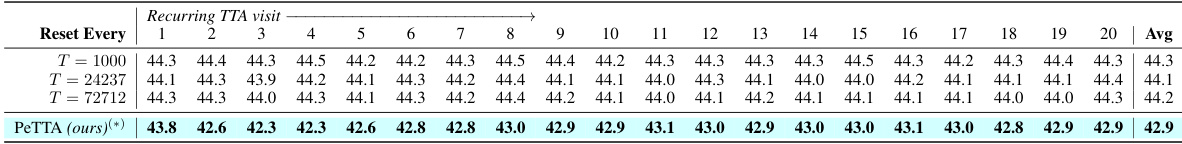

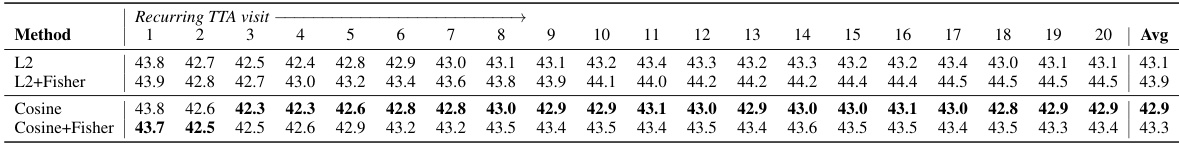

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task in a recurring test-time adaptation (TTA) setting. The results are broken down by the visit number (how many times the model has adapted to the test set), showing how performance changes over time. The lowest error for each visit is shown in bold, and the average performance of the PeTTA model over 5 runs is indicated with an asterisk. The table allows for a comparison of PeTTA’s performance against other TTA methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

In-depth insights#

Recurring TTA Risk#

The concept of “Recurring TTA Risk” highlights a critical vulnerability in test-time adaptation (TTA) methods. Existing TTA approaches often assume that environments are encountered only once, failing to account for the error accumulation that occurs when the same environment is revisited. This repeated exposure to previous environments, even with adaptive mechanisms, leads to performance degradation over time, which is a major concern for real-world applications where environmental changes recur. The recurring TTA scenario, therefore, is a crucial diagnostic setting to evaluate the long-term stability and resilience of TTA algorithms. This highlights the need for new adaptation strategies that can prevent error accumulation and maintain performance even after revisiting the same testing environment numerous times, emphasizing a shift from focusing solely on immediate adaptability to achieving long-term performance stability in dynamic environments. Addressing “Recurring TTA Risk” requires robust mechanisms for detecting model collapse and adjusting the adaptation process accordingly, thereby promoting the development of more resilient and sustainable TTA algorithms. Failure to consider this risk leads to seemingly successful short-term adaptations but ultimately result in long-term performance decline.

PeTTA Algorithm#

The PeTTA algorithm addresses the critical issue of performance degradation in test-time adaptation (TTA) scenarios where environmental changes recur. Unlike previous methods that may experience significant performance drops over prolonged exposure to recurring environments, PeTTA incorporates a novel mechanism for continuously monitoring the model’s divergence from its initial state. This is achieved using a divergence sensing term based on feature embeddings. This crucial information is then leveraged to dynamically adjust the adaptation strategy by adaptively modifying the regularization term and update rate. This approach aims to maintain a balance between adaptation to new conditions and the prevention of model collapse. Key components of PeTTA include the use of a memory bank, mean teacher updates, anchor loss, and the dynamic adaptation scheme. The theoretical analysis and experimental results presented suggest that PeTTA offers significant improvements in stability and adaptability over existing approaches, demonstrating a persistent performance even when faced with many cycles of recurring environmental shifts.

E-GMMC Analysis#

The E-GMMC (epsilon-perturbed Gaussian Mixture Model Classifier) analysis section is crucial because it provides a simplified yet informative model for understanding the core issues of recurring test-time adaptation (TTA). The analysis leverages the simplicity of the GMMC to derive theoretical insights into the factors that contribute to model collapse, a phenomenon where the model’s performance degrades over time due to error accumulation. By introducing a controlled error rate (epsilon) into the pseudo-label predictor, the analysis simulates the real-world scenario where the testing data stream introduces noise, impacting the quality of pseudo-labels. Key findings revolve around the interplay between the false negative rate, the prior distribution of classes, and algorithm hyperparameters. This theoretical framework is essential as it helps explain the reasons for the observed performance degradation in real-world experiments and supports the design of more robust algorithms that mitigate model collapse, ultimately leading to more sustainable test-time adaptation methods. The mathematical rigor employed enables a deeper understanding of model behavior, allowing for the development of solutions that address the issue of performance degradation effectively.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model or system to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a research paper, an ablation study on test-time adaptation (TTA) would likely investigate the impact of different modules or design choices. For example, removing a specific regularization technique might reveal its role in preventing model collapse. Similarly, removing a particular adaptation strategy could isolate its effect on accuracy and stability. By carefully analyzing the performance changes resulting from each ablation, researchers can gain a deeper understanding of how different parts of the TTA system interact and contribute to the overall performance. A well-designed ablation study is crucial for establishing causality and isolating the contributions of different components, leading to stronger conclusions and guiding future research directions. The results demonstrate the importance of the study, by isolating the individual effects of various design choices.

Future of TTA#

The future of test-time adaptation (TTA) hinges on addressing its current limitations and exploring new avenues. Robustness to catastrophic forgetting remains a key challenge; methods preventing gradual performance degradation over extended use are crucial. Theoretical understanding of TTA’s behavior, particularly under complex, recurring scenarios, needs further development. This includes deeper analysis of error accumulation and model collapse. Adaptive strategies dynamically adjusting to varying data characteristics are essential. Future research should also investigate efficient computational methods, minimizing the resources needed for real-time adaptation. Finally, extending TTA’s applicability beyond image classification to other domains, like natural language processing and time series analysis, promises exciting advancements.

More visual insights#

More on figures

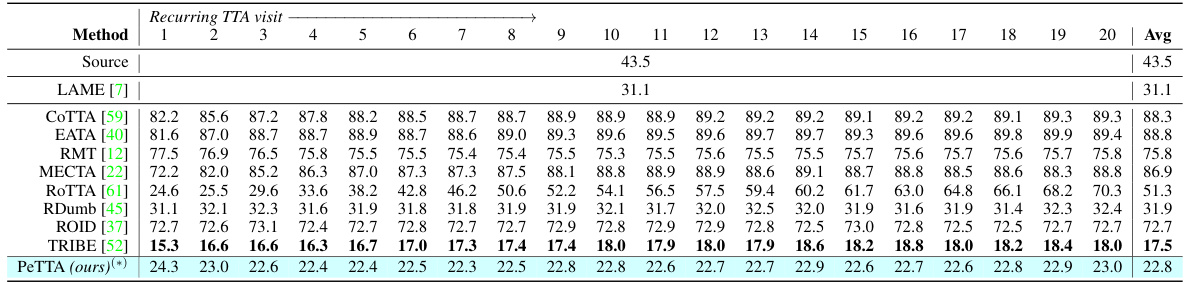

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of a simple e-perturbed binary Gaussian Mixture Model Classifier used for theoretical analysis in the paper. It consists of a pseudo-label predictor that takes in the input data Xt and the previous teacher model parameters θt-1 to produce pseudo labels Ŷt. The pseudo-label predictor is perturbed to simulate the undesirable effects of a real-world testing stream. A mean-teacher update block then takes in the pseudo labels, the current input data, and updates the student model parameters θt’ which are then used to update the teacher model parameters θt via an exponential moving average update. The updated teacher model is then used for future predictions.

read the caption

Figure 2: e-perturbed binary Gaussian Mixture Model Classifier, imitating a continual TTA algorithm for theoretical analysis. Two main components include a pseudo-label predictor (Eq. 1), and a mean teacher update (Eqs. 2, 3). The predictor is perturbed for retaining a false negative rate of et to simulate an undesirable TTA testing stream.

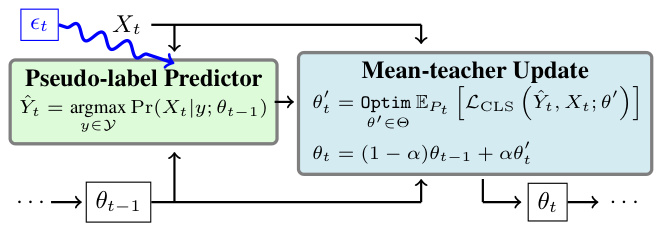

🔼 This figure demonstrates the results of a simulation using an e-perturbed binary Gaussian Mixture Model Classifier to illustrate the theoretical analysis of the paper. Panel (a) shows histograms of model predictions over time for both the perturbed and unperturbed models. Panel (b) shows the probability density functions of the clusters for both models, highlighting how the perturbed model collapses into a single cluster, while the unperturbed model converges to the true distribution. Finally, panel (c) plots the distance from the mean of one cluster to the mean of the other, along with the false negative rate, over time, comparing simulation results to theoretical predictions.

read the caption

Figure 3: Simulation result on e-perturbed Gaussian Mixture Model Classifier (∈-GMMC) and GMMC (perturbed-free). (a) Histogram of model predictions through time. A similar prediction frequency pattern is observed on CIFAR-10-C (Fig. 5a-left). (b) The probability density function of the two clusters after convergence versus the true data distribution. The initial two clusters of E-GMMC collapsed into a single cluster with parameters stated in Lemma 2. In the perturbed-free, GMMC converges to the true data distribution. (c) Distance toward μ₁ (|Ερε [μο,t] – µ₁|) and false-negative rate (et) in simulation coincides with the result in Thm. 1 (with et following Corollary 1).

🔼 The left panel shows a recurring test-time adaptation scenario where the testing environments change over time and recur. The right panel compares the performance of three different test-time adaptation methods in this setting. RoTTA’s performance degrades over time, exceeding the error of the baseline (no adaptation). In contrast, the proposed PeTTA method maintains stability and performance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Recurring Test-time Adaption (TTA). (left) Testing environments may change recurringly and preserving adaptability when visiting the same testing condition is not guaranteed. (right) The testing error of RoTTA [61] progressively raises (performance degradation) and exceeds the error of the source model (no TTA) while our PeTTA demonstrates its stability when adapting to the test set of CIFAR-10-C [19] 20 times. The bold lines denote the running mean and the shaded lines in the background represent the testing error on each domain (excluding the source model, for clarity).

🔼 This figure demonstrates the concept of recurring test-time adaptation (TTA). The left panel illustrates a scenario where environmental conditions (e.g., illumination) change repeatedly. The right panel shows the test error for three methods: no test-time adaptation (baseline), RoTTA (a prior state-of-the-art method), and PeTTA (the authors’ proposed method). PeTTA maintains consistently low error over multiple test cycles (representing repeated exposure to the same conditions), unlike RoTTA which shows error degradation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Recurring Test-time Adaption (TTA). (left) Testing environments may change recurringly and preserving adaptability when visiting the same testing condition is not guaranteed. (right) The testing error of RoTTA [61] progressively raises (performance degradation) and exceeds the error of the source model (no TTA) while our PeTTA demonstrates its stability when adapting to the test set of CIFAR-10-C [19] 20 times. The bold lines denote the running mean and the shaded lines in the background represent the testing error on each domain (excluding the source model, for clarity).

🔼 The left panel of the figure shows a recurring test-time adaptation (TTA) scenario where the testing environments change recurringly, implying that the model’s ability to adapt might not be preserved upon revisiting the same environment. The right panel compares the performance of three different methods in this recurring TTA scenario: No TTA (no test-time adaptation), ROTTA (a previous state-of-the-art TTA method), and PeTTA (the proposed method). The plot shows the test error over 300 adaptation steps, highlighting PeTTA’s superior stability compared to ROTTA, which experiences performance degradation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Recurring Test-time Adaption (TTA). (left) Testing environments may change recurringly and preserving adaptability when visiting the same testing condition is not guaranteed. (right) The testing error of RoTTA [61] progressively raises (performance degradation) and exceeds the error of the source model (no TTA) while our PeTTA demonstrates its stability when adapting to the test set of CIFAR-10-C [19] 20 times. The bold lines denote the running mean and the shaded lines in the background represent the testing error on each domain (excluding the source model, for clarity).

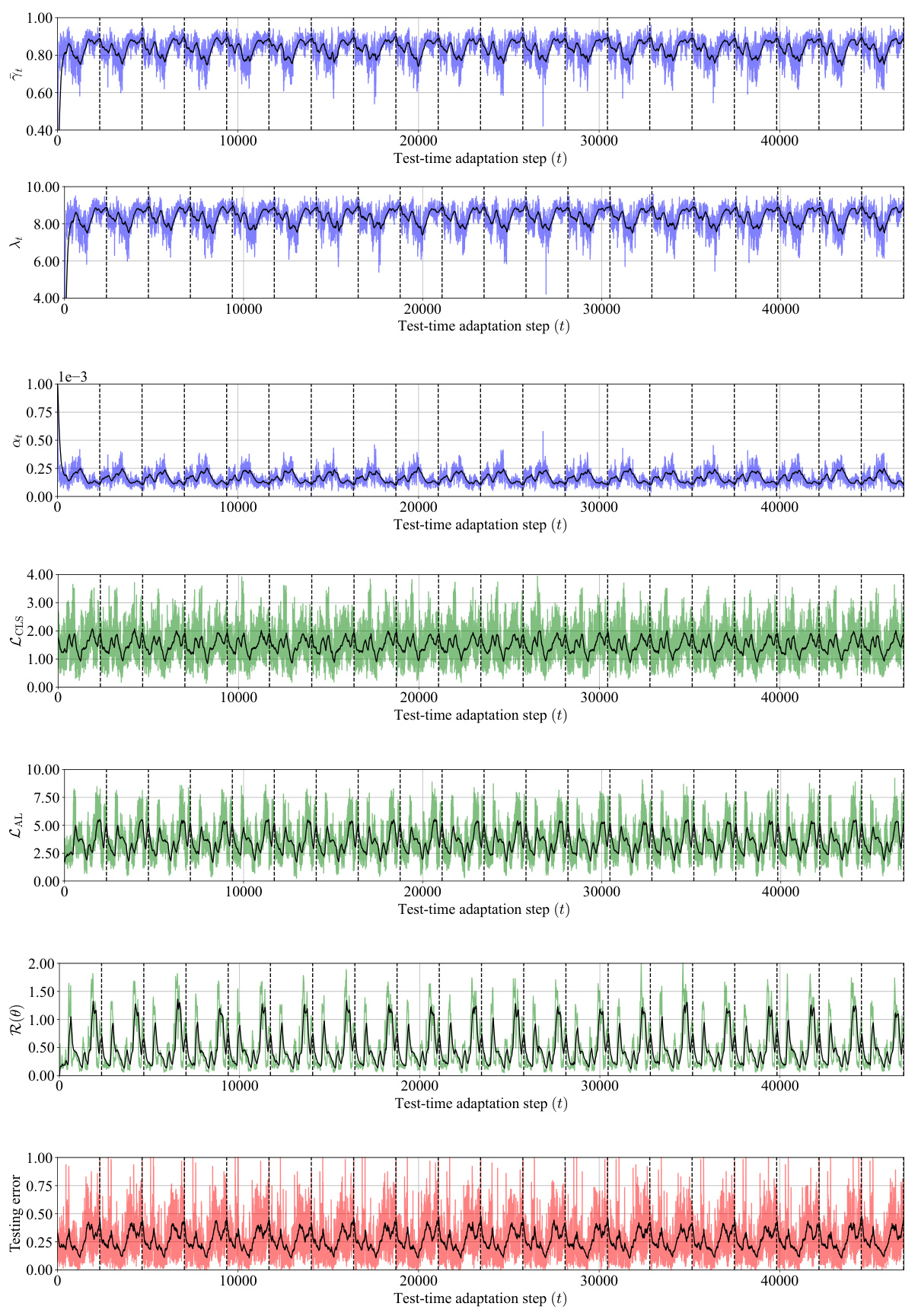

🔼 This figure shows the detailed visualization of the adaptive parameters and loss functions during the recurring test-time adaptation. It demonstrates how PeTTA’s adaptive mechanism maintains performance stability across multiple visits by adjusting its hyperparameters. The plots showcase the dynamic changes of these values, highlighting the balance between adaptation and collapse prevention.

read the caption

Figure 7: An inspection of PeTTA on the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C [19] in a recurring with 20 visits (visits are separated by the vertical dashed lines). Here, we visualize (rows 1-3) the dynamic of PeTTA adaptive parameters (γt, δt, αt), (rows 4-5) the value of the loss functions (LCLS, LAL) and (row 6) the value of the regularization term (R(0)) and (row 7) the classification error rate at each step. The solid line in the foreground of each plot denotes the running mean. The plots show an adaptive change of λt, αt through time in PeTTA, which stabilizes TTA performance, making PeTTA achieve a persisting adaptation process in all observed values across 20 visits.

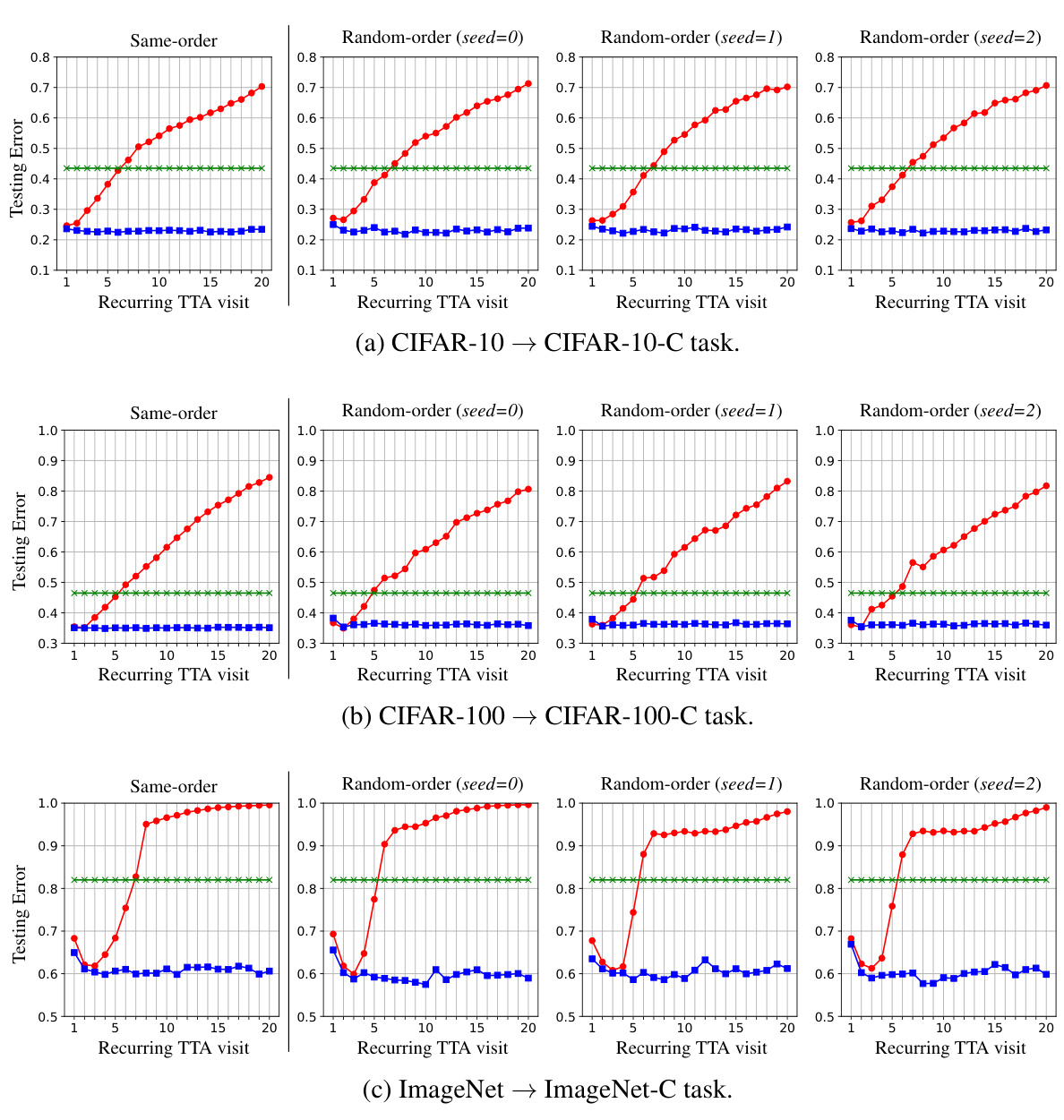

🔼 This figure shows the testing error of PeTTA across 40 recurring visits on three different corrupted image datasets: CIFAR-10-C, CIFAR-100-C, and ImageNet-C. The plot demonstrates PeTTA’s sustained performance over a prolonged period. While the error fluctuates slightly, it doesn’t exhibit the significant, continuous increase observed in other approaches (as shown in Figure 1). This highlights PeTTA’s resilience to model collapse over extended, recurring testing scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 8: Testing error of PeTTA with 40 recurring TTA visits.

🔼 This figure shows the results of an ablation study on CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C using PeTTA with 20 visits. It visualizes how PeTTA’s adaptive parameters (γt, dt, αt), loss functions (LCLS, LAL), regularization term (R(0)), and testing error change over time. The adaptive nature of PeTTA’s parameters helps to stabilize performance over many visits, avoiding the performance degradation observed in other methods.

read the caption

Figure 7: An inspection of PeTTA on the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C [19] in a recurring with 20 visits (visits are separated by the vertical dashed lines). Here, we visualize (rows 1-3) the dynamic of PeTTA adaptive parameters (γt, dt, αt), (rows 4-5) the value of the loss functions (LCLS, LAL) and (row 6) the value of the regularization term (R(0)) and (row 7) the classification error rate at each step. The solid line in the foreground of each plot denotes the running mean. The plots show an adaptive change of λt, αt through time in PeTTA, which stabilizes TTA performance, making PeTTA achieve a persisting adaptation process in all observed values across 20 visits.

🔼 The figure demonstrates the recurring test-time adaptation (TTA) scenario. The left panel shows a real-world example of recurring illumination conditions in a surveillance camera setting, highlighting the challenge of maintaining model adaptability over prolonged exposure to the same conditions. The right panel compares the performance of the proposed PeTTA method with an existing RoTTA method on a recurring TTA task using CIFAR-10-C dataset. PeTTA exhibits superior stability in maintaining its adaptability over multiple cycles, unlike RoTTA, which demonstrates performance degradation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Recurring Test-time Adaption (TTA). (left) Testing environments may change recurringly and preserving adaptability when visiting the same testing condition is not guaranteed. (right) The testing error of RoTTA [61] progressively raises (performance degradation) and exceeds the error of the source model (no TTA) while our PeTTA demonstrates its stability when adapting to the test set of CIFAR-10-C [19] 20 times. The bold lines denote the running mean and the shaded lines in the background represent the testing error on each domain (excluding the source model, for clarity).

🔼 The left panel shows a recurring test-time adaptation scenario where the testing environments change recurringly. The right panel demonstrates the performance of three test-time adaptation methods. RoTTA shows a degradation in performance over multiple cycles of recurring environments. PeTTA demonstrates stability in these same conditions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Recurring Test-time Adaption (TTA). (left) Testing environments may change recurringly and preserving adaptability when visiting the same testing condition is not guaranteed. (right) The testing error of RoTTA [61] progressively raises (performance degradation) and exceeds the error of the source model (no TTA) while our PeTTA demonstrates its stability when adapting to the test set of CIFAR-10-C [19] 20 times. The bold lines denote the running mean and the shaded lines in the background represent the testing error on each domain (excluding the source model, for clarity).

More on tables

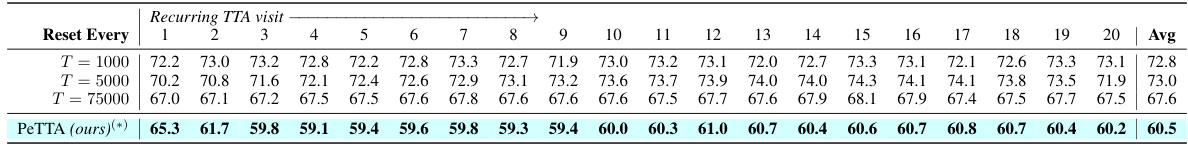

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task in a recurring test-time adaptation (TTA) setting. The results are shown for 20 consecutive visits to the test set, where the same testing environments recur. The table compares various TTA methods, including PeTTA (the proposed method), ROTTA, and others. The lowest error for each visit is highlighted in bold. For PeTTA, the average across 5 independent runs is shown, indicated by an asterisk.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

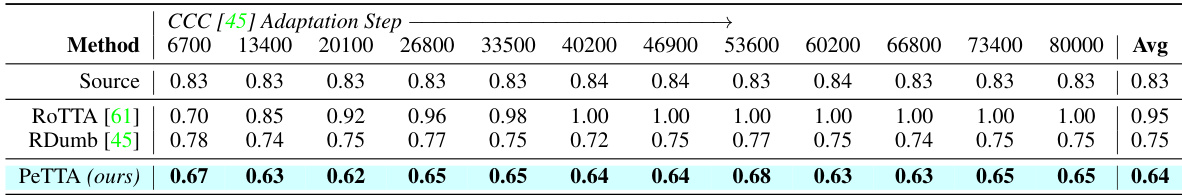

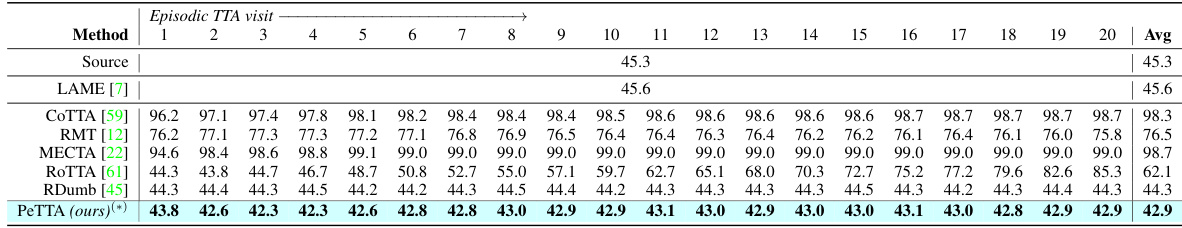

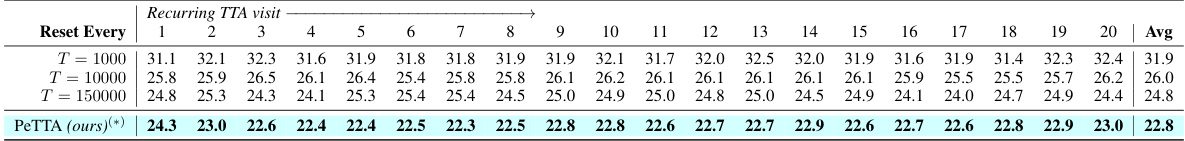

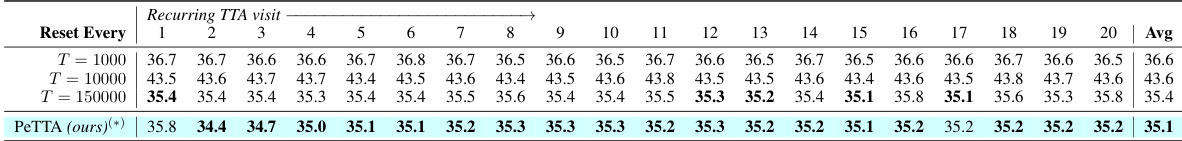

🔼 This table shows the average classification error on the Continuously Changing Corruption (CCC) dataset. The dataset simulates a continuously changing environment, and each column represents the average error over a specific interval of adaptation steps. The results compare several methods, including the proposed PeTTA, ROTTA, and RDumb, demonstrating PeTTA’s superior performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Average classification error on CCC [45] setting. Each column presents the average error within an adaptation interval (e.g., the second column provides the average error between the 6701 and 13400 adaptation steps). Each adaptation step here is performed on a mini-batch of 64 images.

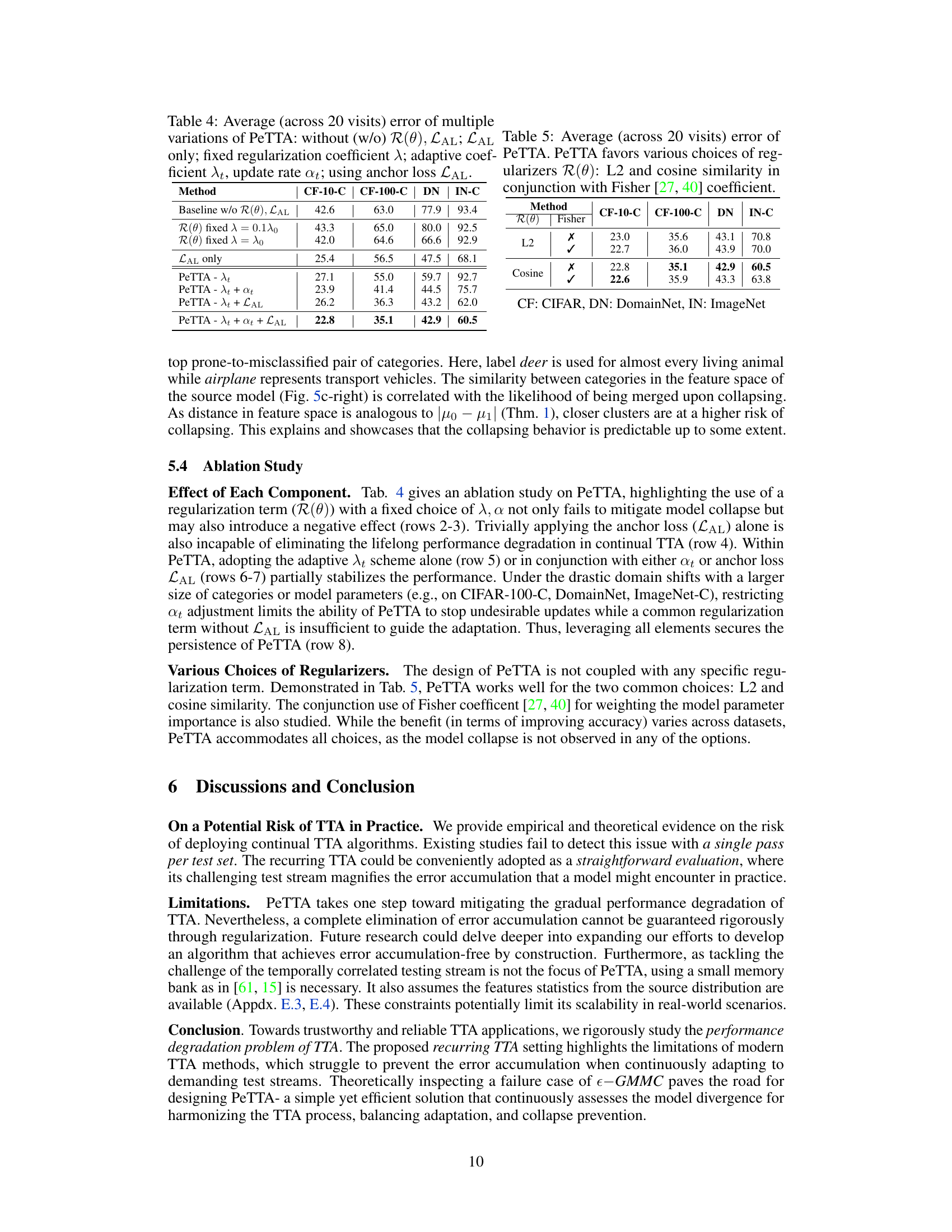

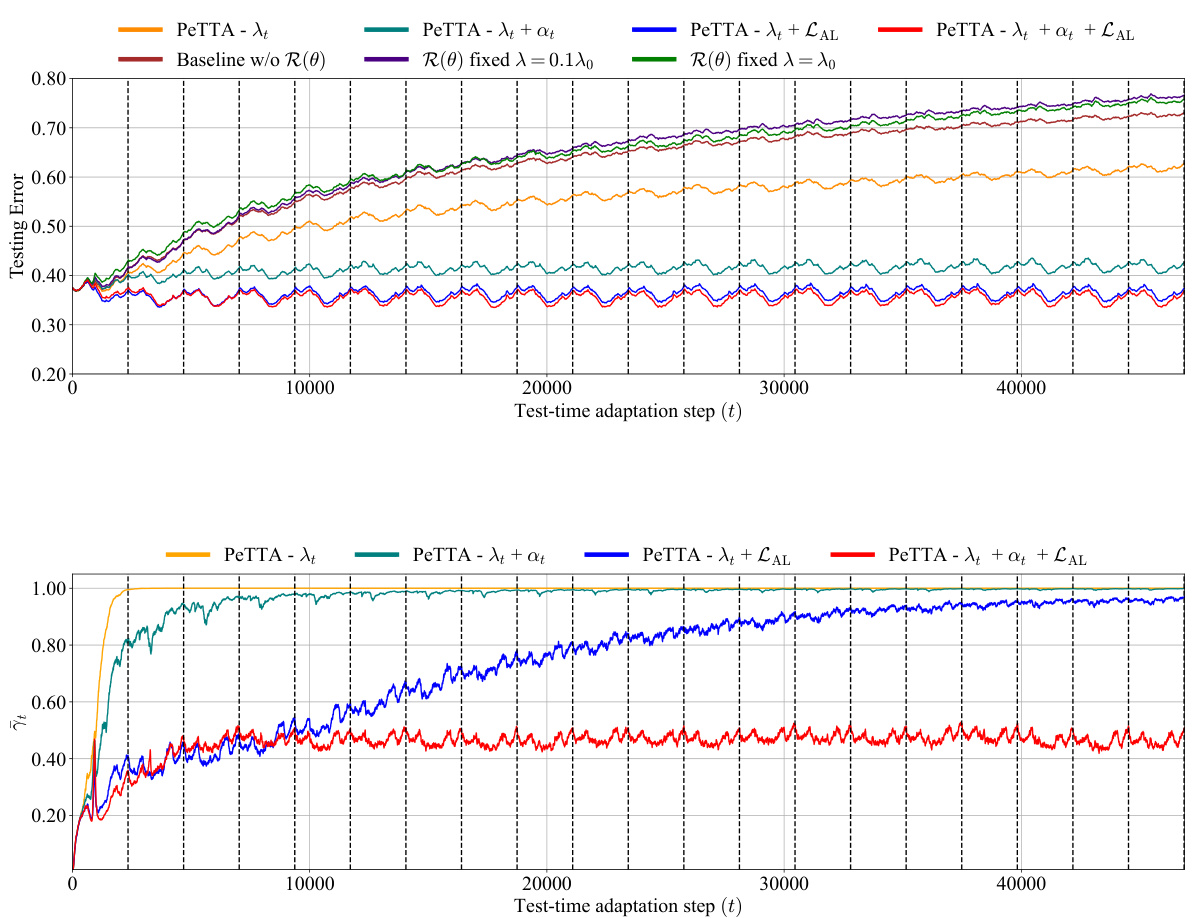

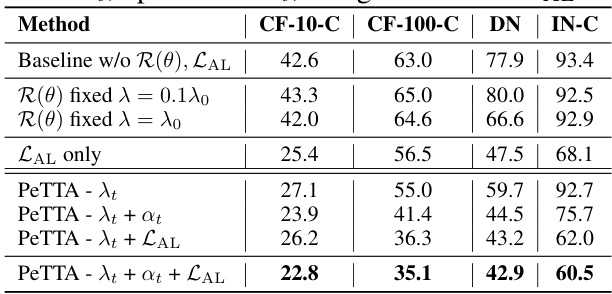

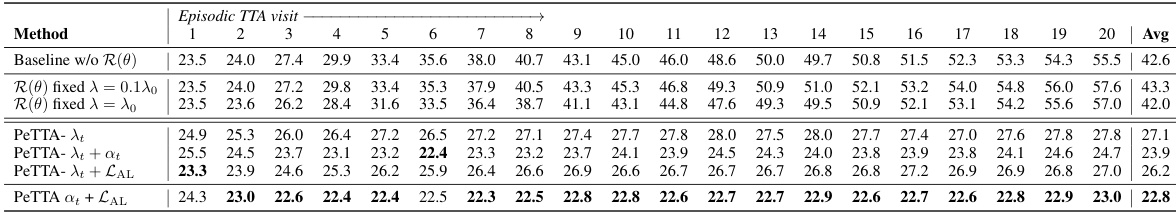

🔼 This ablation study investigates the impact of each component of PeTTA on the final performance. It compares the average error across 20 visits in recurring TTA for variations of PeTTA with different combinations of components removed or fixed. The results show the importance of all components working together for optimal performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Average (across 20 visits) error of multiple variations of PeTTA: without (w/o) R(θ), LAL; LAL only; fixed regularization coefficient ; adaptive coefficient λt, update rate αt; using anchor loss LAL.

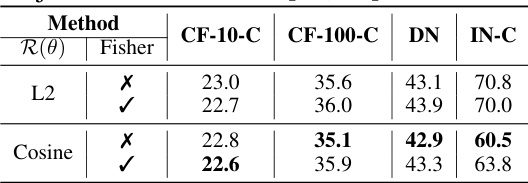

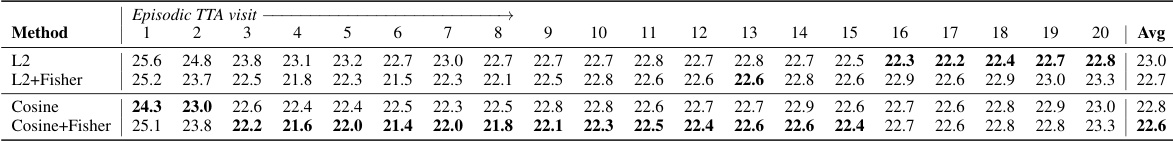

🔼 This table shows the average classification error across 20 visits of PeTTA using different regularizers: L2, cosine similarity, and their combinations with the Fisher coefficient. The results are presented for four different tasks: CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C (CF-10-C), CIFAR-100 to CIFAR-100-C (CF-100-C), DomainNet (DN), and ImageNet to ImageNet-C (IN-C). The table helps to demonstrate that PeTTA performs well regardless of the specific regularizer chosen.

read the caption

Table 5: Average (across 20 visits) error of PeTTA. PeTTA favors various choices of regularizers R(θ): L2 and cosine similarity in conjunction with Fisher [27, 40] coefficient.

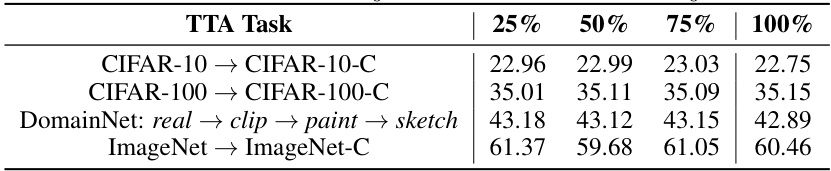

🔼 This table shows the average classification error of the PeTTA model across 20 visits for four different tasks (CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C, CIFAR-100 to CIFAR-100-C, DomainNet: real to clip, paint, sketch, and ImageNet to ImageNet-C). The key variable is the size of the source samples used to compute the empirical mean (μ) and covariance matrix (Σ). The sizes are 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% of the available source samples. The table helps to analyze how the accuracy of PeTTA varies depending on the size of the source sample set used for the calculation of (μ, Σ).

read the caption

Table 6: Average classification error of PeTTA (across 20 visits) with varying sizes of source samples used for computing feature empirical mean (μ) and covariant matrix (Σ).

🔼 This table shows the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task in a recurring test-time adaptation (TTA) setting. The results are broken down by TTA visit (1-20) and method. The methods compared include several existing TTA approaches, a parameter-free baseline (LAME), a reset-based baseline (RDumb), and the proposed PeTTA method. The lowest error rate for each visit is shown in bold. For the PeTTA method, the average of five independent runs is reported.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table shows the average classification error for different TTA methods on the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using recurring TTA. The results are presented for each visit (up to 20) of the recurring testing scenarios. The lowest error for each visit is shown in bold, and the results for PeTTA are averaged over 5 independent runs with different random seeds.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods in a recurring testing scenario. The recurring TTA involves repeatedly exposing the model to the same test set over 20 visits. The lowest error for each visit and the average error across all visits are reported. The table highlights the superior performance of the proposed PeTTA method, especially in later visits where other methods show significant performance degradation.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task across different recurring test-time adaptation (TTA) visits. It shows the performance of several TTA methods, including PeTTA (the proposed method), over 20 cycles of adaptation, where the testing environment is revisited multiple times. The lowest error rate for each visit is highlighted in bold. PeTTA’s results are averaged over 5 runs with different random seeds, indicated by an asterisk (*)

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods in a recurring testing scenario. The recurring TTA involves repeatedly adapting to the same test set over multiple cycles. The table shows the error rate for each method across 20 visits to the test set. The lowest error rate for each visit is shown in bold, and the average error across 5 independent runs of PeTTA is indicated with an asterisk.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table shows the average classification error for different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods on the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task in a recurring TTA setting. The results are presented for 20 consecutive visits to the test set, allowing for observation of error accumulation over time. The lowest error rate for each visit is shown in bold, while the average error rate over the 5 independent runs performed for the PeTTA method is indicated with an asterisk.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task under the recurring test-time adaptation (TTA) setting. The results show the performance of various TTA methods across 20 recurring visits to the same test environments. The lowest error for each visit is highlighted in bold, and the average performance of PeTTA across 5 independent runs with different random seeds is marked with an asterisk. This table provides a quantitative comparison of different TTA methods’ ability to maintain performance over repeated exposure to the same test conditions.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table shows the average classification error of PeTTA on three datasets (CIFAR-10-C, CIFAR-100-C, and ImageNet-C) with different choices of the hyperparameter λ0. The results demonstrate the sensitivity of PeTTA’s performance to this hyperparameter, showing that while optimal performance is achieved around λ0 = 1e1, reasonably similar performance is obtained with values between 5e0 and 5e1. This indicates that the parameter λ0 is not critically sensitive and doesn’t require extremely fine-grained tuning.

read the caption

Table 15: Sensitivity of PeTTA with different choices of λ0.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task under recurring test-time adaptation (TTA). It shows the error rate for different methods across 20 visits to the test set. The lowest error for each visit is highlighted in bold, and the average performance of the PeTTA method (across 5 independent runs with different random seeds) is marked with an asterisk.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for different methods on the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using the recurring TTA setting. It shows the error rate for each method across 20 visits to the test set. The lowest error for each visit is highlighted in bold, and PeTTA results are averaged across 5 runs with different random seeds.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods in a recurring testing scenario. The recurring TTA involves repeatedly exposing the model to the same testing environment after it has undergone various adaptations. The table shows the error for each method across 20 visits to the recurring testing environment. The lowest error for each visit is shown in bold, and the average error across 5 runs of PeTTA (with different random seeds) is marked with an asterisk.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods in a recurring testing scenario. The recurring scenario involves repeatedly adapting to the same test environments over 20 visits. The table shows the performance of various TTA methods (COTTA, EATA, RMT, MECTA, ROTTA, RDumb, ROID, TRIBE, and PeTTA) across these visits. The lowest error rate for each visit is highlighted in bold, and the PeTTA results are averaged across five independent runs.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table shows the average classification error for different TTA methods on the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task across 20 recurring visits. The table compares PeTTA’s performance against several existing TTA methods and a simple reset-based baseline. The lowest error for each visit is highlighted in bold, and PeTTA’s results are averaged over 5 independent runs with different random seeds. The table helps to demonstrate PeTTA’s superior stability compared to existing approaches in recurring TTA.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods in a recurring testing scenario. The recurring scenario involves repeatedly exposing the model to the same test environments over 20 cycles. The table shows the average error for each visit (cycle) and for each method. The lowest error for each visit is highlighted in bold, and the average error for PeTTA (a proposed method) is an average across 5 independent runs with different random seeds. The table helps demonstrate how different TTA methods perform across recurring testing environments, highlighting their stability and showing the superior performance of PeTTA in maintaining low error over time.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods in a recurring testing scenario. The recurring scenario involves repeatedly exposing the model to the same test environments. The table shows the error rate for each visit (repeated exposure to the same test environment) up to 20 visits. The lowest error for each visit is shown in bold. The PeTTA method’s performance is an average across five independent runs with different random seeds.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods in a recurring TTA setting. The results are shown for 20 consecutive visits to the test set. Lower error values indicate better performance. The table includes results for several existing TTA methods (COTTA, EATA, RMT, MECTA, ROTTA, RDumb, ROID, TRIBE) and a parameter-free baseline (LAME). The PeTTA method proposed in the paper is also shown, with the average of 5 independent runs reported.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

🔼 This table presents the average classification error for the CIFAR-10 to CIFAR-10-C task using different test-time adaptation (TTA) methods in a recurring testing scenario. The table shows the error rate for each of the 20 visits to the test set and the average error across all visits. The lowest error rate for each visit is highlighted in bold, and the average error rate for PeTTA is an average across 5 independent runs with different random seeds.

read the caption

Table 1: Average classification error of the task CIFAR-10 → CIFAR-10-C in recurring TTA. The lowest error is in bold, (*) average value across 5 runs (different random seeds) is reported for PeTTA.

Full paper#