TL;DR#

Face recognition struggles with low-resolution and long-range scenarios. Existing methods often require large intermediate representations or metadata, hindering compatibility with legacy systems and real-time applications. They also struggle to generalize to large probe sets.

ProxyFusion tackles these limitations. It uses a novel linear-time O(N) proxy-based sparse expert selection and pooling method. This is order-invariant, generalizes well, is compatible with legacy systems and has low parameter count, allowing for real-time inference. Experiments on IARPA BTS3.1 and DroneSURF datasets demonstrate ProxyFusion’s superiority in unconstrained long-range face recognition.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses crucial challenges in face recognition, particularly in challenging conditions such as low resolution and long-range scenarios. Its novel approach offers a significant improvement in accuracy and efficiency, paving the way for more robust and practical face recognition systems. The proposed method’s linear time complexity opens doors for real-time applications, making it highly relevant to current research trends in edge computing and resource-constrained environments. Furthermore, the code and pre-trained models’ availability fosters reproducibility and facilitates further research and development.

Visual Insights#

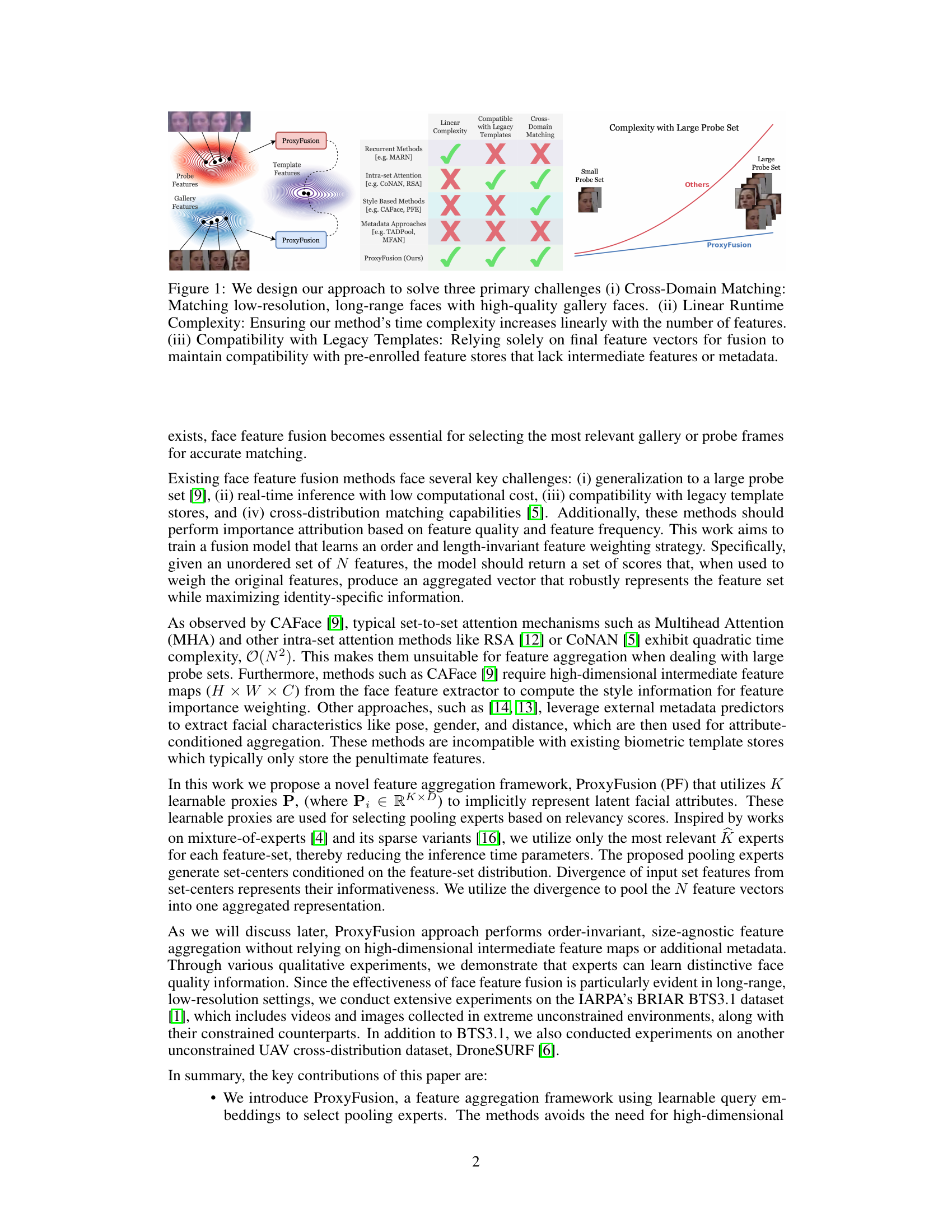

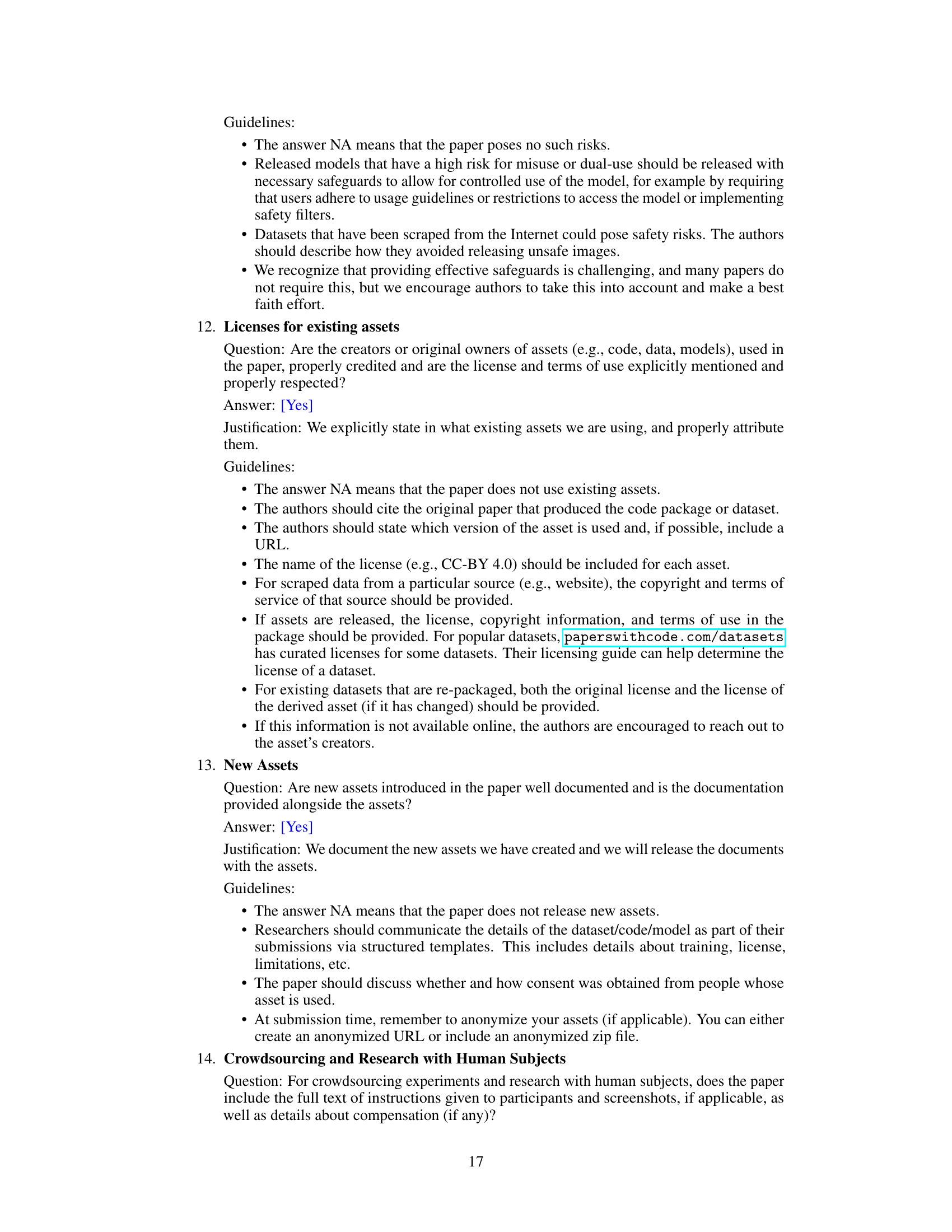

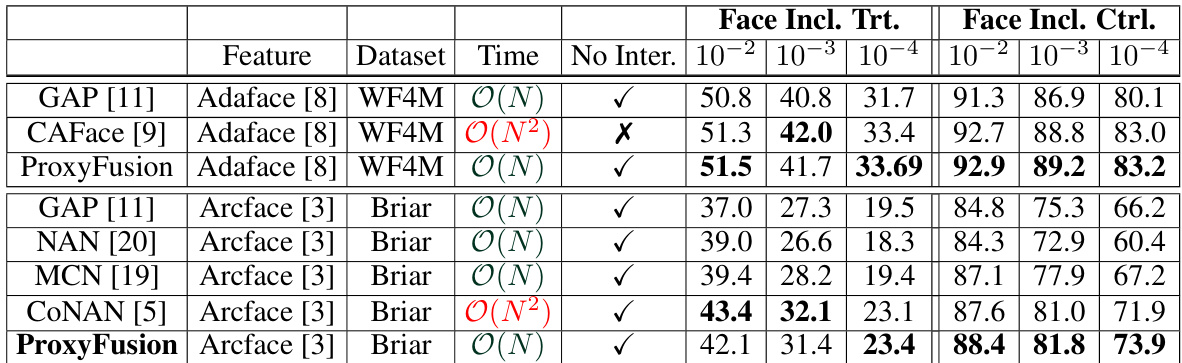

🔼 This figure illustrates the three main challenges that the ProxyFusion method addresses: Cross-domain matching (matching low-resolution, long-range faces with high-quality gallery faces), linear runtime complexity (ensuring linear increase in time complexity with the number of features), and compatibility with legacy templates (using only final feature vectors, compatible with existing template databases that do not store intermediate features or metadata). The figure uses a table to compare ProxyFusion to other existing methods for each of the three challenges, showcasing ProxyFusion’s advantages in terms of solving these challenges simultaneously.

read the caption

Figure 1: We design our approach to solve three primary challenges (i) Cross-Domain Matching: Matching low-resolution, long-range faces with high-quality gallery faces. (ii) Linear Runtime Complexity: Ensuring our method's time complexity increases linearly with the number of features. (iii) Compatibility with Legacy Templates: Relying solely on final feature vectors for fusion to maintain compatibility with pre-enrolled feature stores that lack intermediate features or metadata.

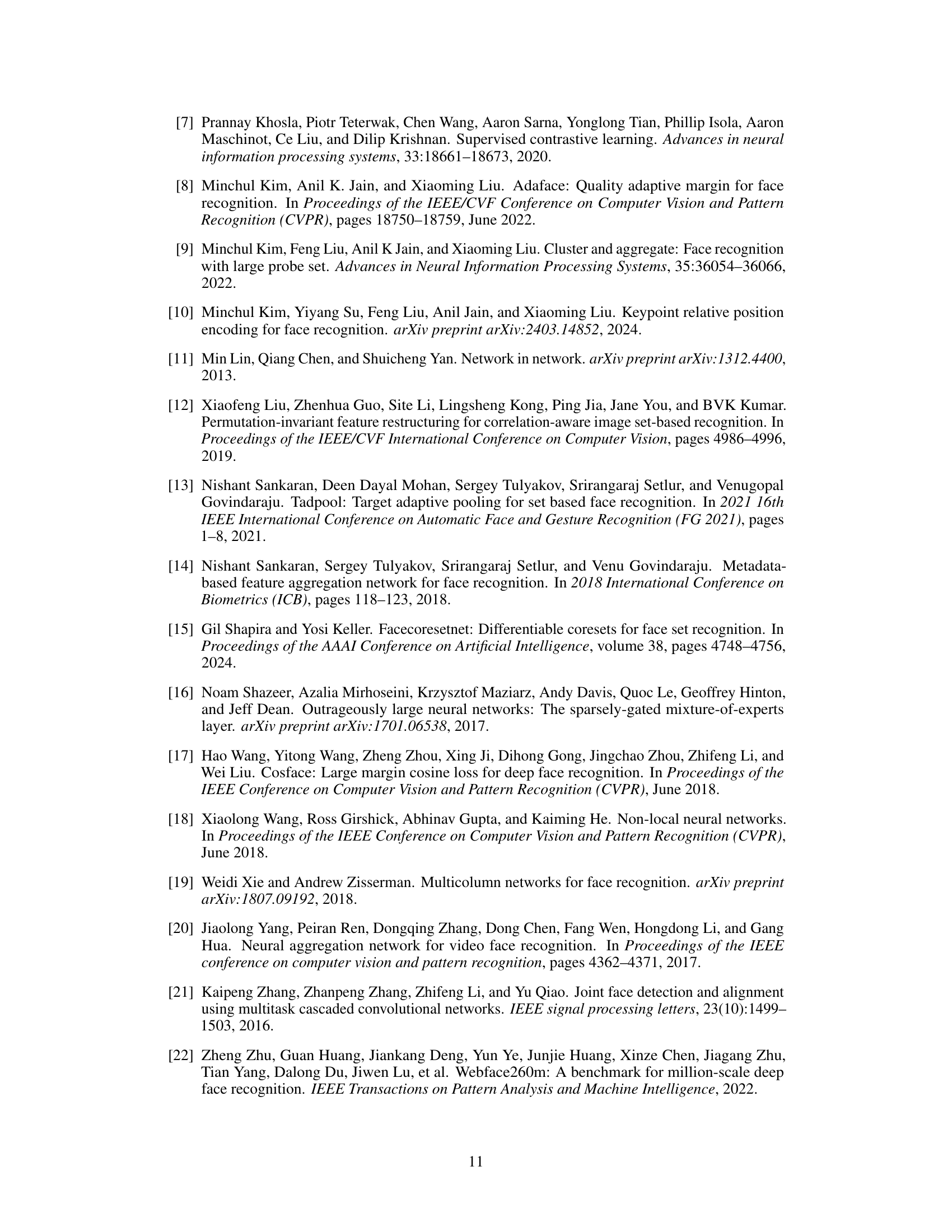

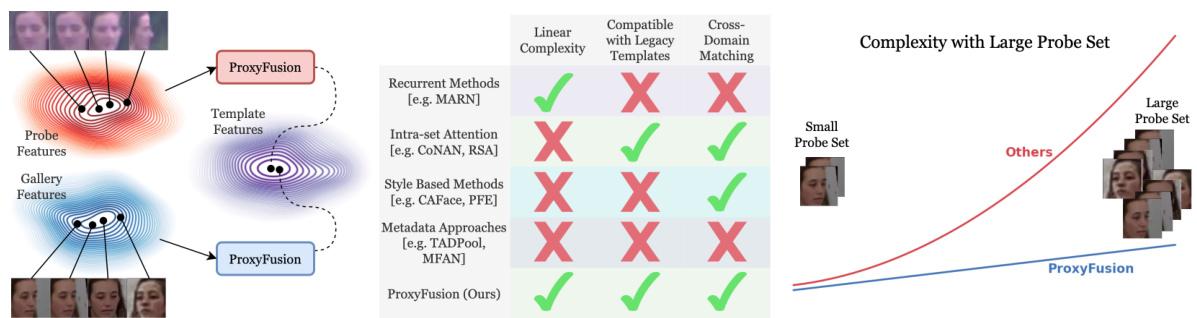

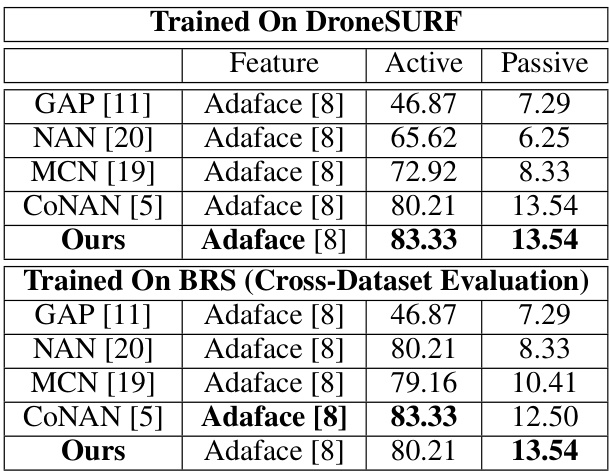

🔼 This table presents the performance analysis of the ProxyFusion model under different training scenarios. It shows the impact of using the proxy loss (LProxy) and varying the number of selected experts (K) on the model’s performance. The results are measured in terms of a certain metric (not specified in the snippet), with higher values indicating better performance. By comparing the performance with and without the proxy loss for different values of K, we can assess the effectiveness of the proxy loss in enhancing the model’s performance and identify the optimal number of selected experts.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance analysis of the model while training with and without proxy loss with varying number of selected experts.

In-depth insights#

Sparse Expert Fusion#

Sparse expert fusion is a promising technique for aggregating facial features, particularly in challenging scenarios like low-resolution or long-range face recognition. The core idea revolves around selecting a subset of the most relevant features (experts) rather than using all available features, thereby significantly reducing computational complexity and improving efficiency. This selection process often involves learning proxies to weigh feature importance, making the method order-invariant and scalable. The sparsity introduces efficiency benefits, enabling real-time inference suitable for resource-constrained environments. Improved generalization to large probe sets and compatibility with legacy biometric databases that store pre-computed features represent additional advantages. However, careful consideration must be given to choosing the number of selected experts and the training process to balance performance gains against potential issues like overfitting or information loss.

Linear Time Complexity#

Achieving linear time complexity in face feature fusion is a significant challenge, particularly when dealing with large datasets. Traditional methods often exhibit quadratic or even higher-order time complexity, limiting their scalability and real-time applicability. The ProxyFusion approach directly addresses this limitation by employing a sparse expert selection mechanism. Instead of processing all features, it strategically selects a subset of relevant features, resulting in a linear runtime that scales gracefully with the number of input features. This efficiency is crucial for handling the large probe sets encountered in unconstrained face recognition settings. Order invariance further enhances practicality, as the algorithm’s performance is not affected by the ordering of the input features, simplifying preprocessing. The use of learnable proxies to implicitly capture relevant facial attributes contributes to the overall efficiency and effectiveness. This innovative strategy allows ProxyFusion to achieve both speed and accuracy, making it suitable for real-world deployment.

Legacy Template Use#

The concept of ‘Legacy Template Use’ in face recognition is crucial because it addresses the compatibility issue between modern algorithms and older, established biometric systems. Many existing biometric databases store pre-computed features, often in formats incompatible with current deep learning approaches. A system that can utilize these legacy templates without requiring extensive feature recalculation offers significant advantages: reduced processing time, lower computational costs, and ease of integration with existing infrastructure. The challenge lies in effectively fusing these legacy features with potentially richer, more modern features while maintaining accuracy and robustness. Success hinges on finding a method that can appropriately weight and combine diverse data sources, handling varying quality and informativeness of features from different origins. This ultimately translates to a system that is more efficient, practical, and adaptable for real-world applications, and it underscores the importance of developing algorithms capable of working effectively with existing resources and databases.

Cross-Domain Matching#

Cross-domain matching in face recognition addresses the challenge of matching faces captured under significantly different conditions, such as low-resolution, long-range images (probe set) with high-resolution, close-range images (gallery set). This discrepancy in image quality and acquisition settings creates a substantial domain gap, hindering accurate matching. Effective cross-domain matching techniques must learn robust feature representations that are invariant to these variations, focusing on identity-preserving features rather than those sensitive to imaging conditions. Addressing this gap is crucial for enhancing the reliability and scope of face recognition systems in real-world applications. Strategies may involve advanced deep learning architectures, domain adaptation methods, and careful selection of robust, discriminatory features. Ultimately, robust cross-domain matching leads to systems capable of accurate and reliable face identification across a wide range of challenging scenarios.

ProxyFusion’s Limits#

ProxyFusion, while demonstrating strong performance in long-range, low-resolution face recognition, exhibits limitations. Its reliance on learnable proxies for feature weighting, though efficient, might restrict its ability to capture intricate intra-set relationships that more complex attention mechanisms could handle. The model’s performance depends on the quality of pre-extracted features, inheriting limitations from the face detection and recognition backbones. Generalization to unseen domains could be a challenge, as the learned proxies might not readily adapt to significantly different facial characteristics or imaging conditions. Furthermore, while linear time complexity is achieved, the actual inference time still depends on the number of selected experts. Therefore, even though ProxyFusion addresses many challenges, it would benefit from further development to expand its robustness and improve its ability to deal with highly variable and complex facial data.

More visual insights#

More on figures

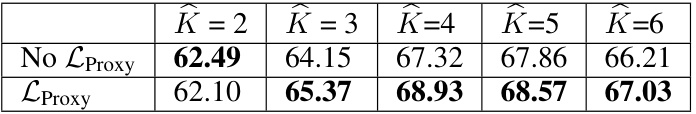

🔼 This figure illustrates the ProxyFusion approach, which consists of two main stages: Expert Selection and Sparse Expert Network Feature Aggregation. The Expert Selection module uses learnable proxies to identify the most relevant expert networks for a given input feature set. These selected networks then generate set-centers, which are used to compute aggregation weights for the input features, producing a final aggregated representation.

read the caption

Figure 2: An overview of our proposed ProxyFusion Approach. Post feature extraction, our method is divided two end-to-end trainable stages: (i) Expert Selection and (ii) Sparse Expert Network Feature Aggregation. The Expert Selection module takes the {fi}_1 and returns the indices of expert networks based on proxy relevancy scores. Next, the selected expert networks compute set-centers conditioned on distribution and aligned proxy. These set-centers attend over the input feature set {fi}1 to compute aggregation weights.

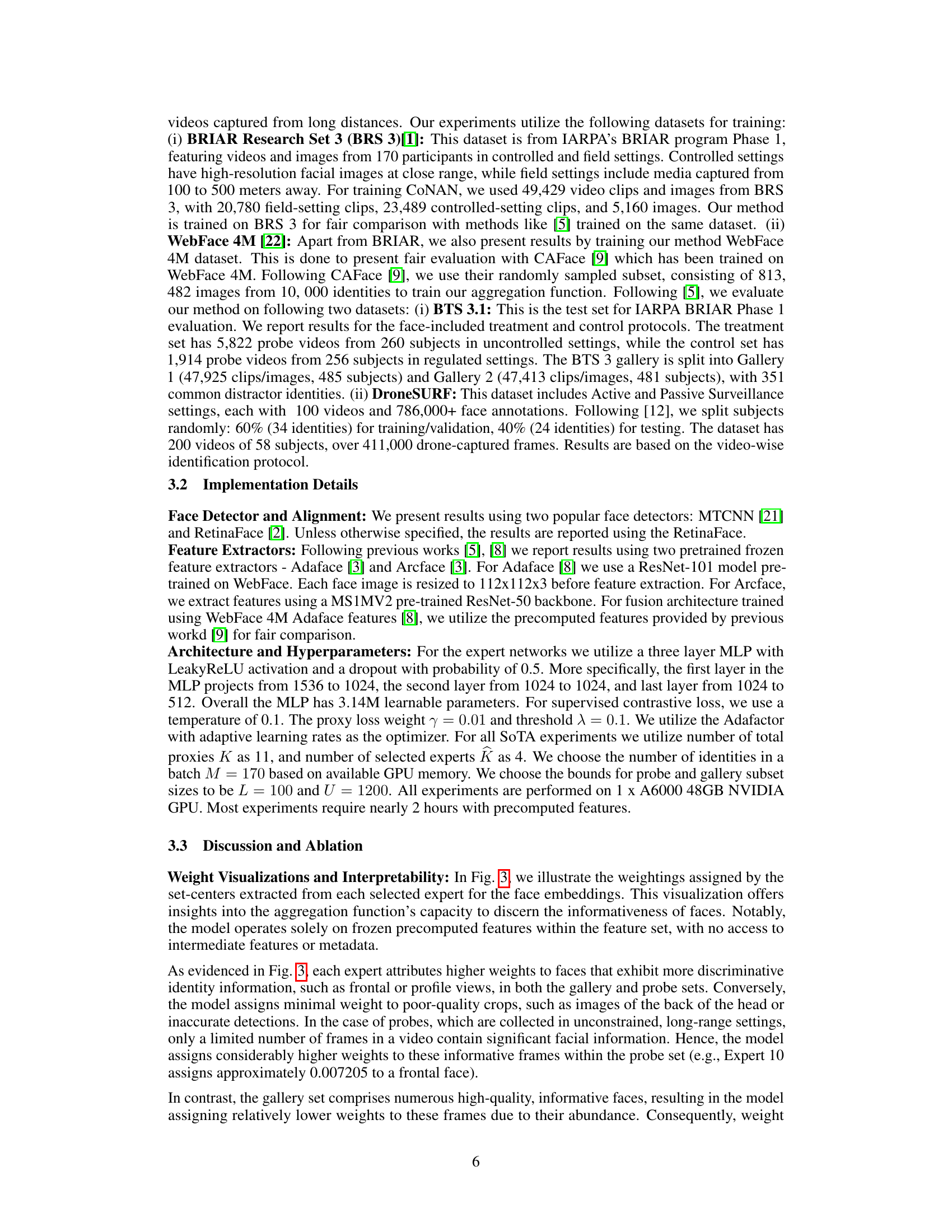

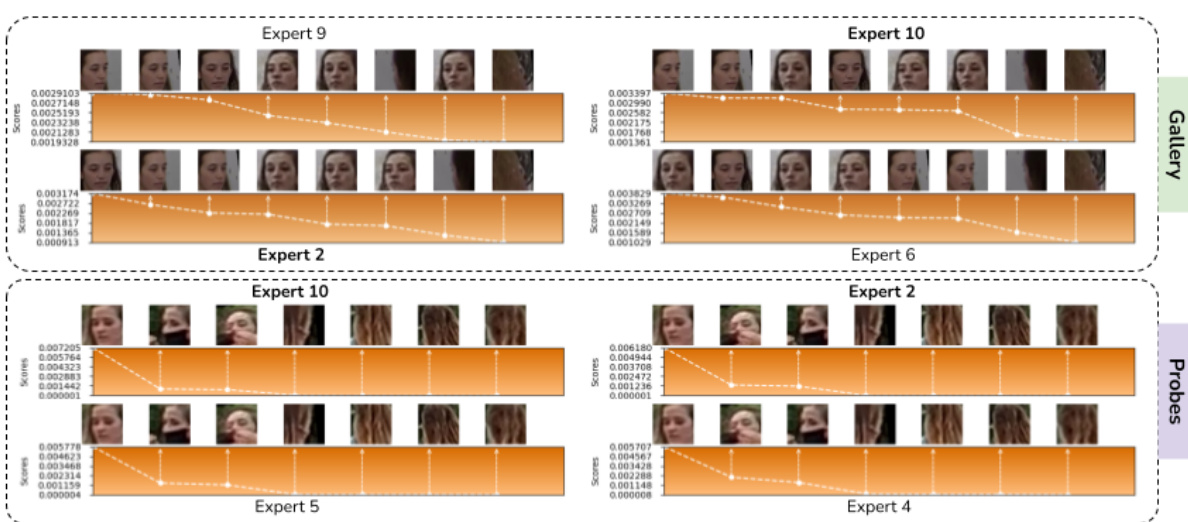

🔼 This figure visualizes the weights assigned by different experts (learned in the ProxyFusion model) to faces within the gallery and probe sets of the BTS3.1 dataset. The images are arranged by their assigned weights, from lowest to highest, revealing how the model prioritizes high-quality, informative faces (frontal views) in the gallery while focusing on the limited number of high-quality frames in the low-resolution probe videos. This demonstrates the model’s ability to learn distinctive face quality information and its effectiveness in long-range, low-resolution face recognition settings.

read the caption

Figure 3: Visualizations of learned weights on BTS3.1 dataset's gallery and probe set. Images on the top are from high quality gallery, and images on the bottom are from low resolution long-range probes. Faces are sorted based on ProxyFusion attention weights from low to high. We present these weights for each of the selected expert.

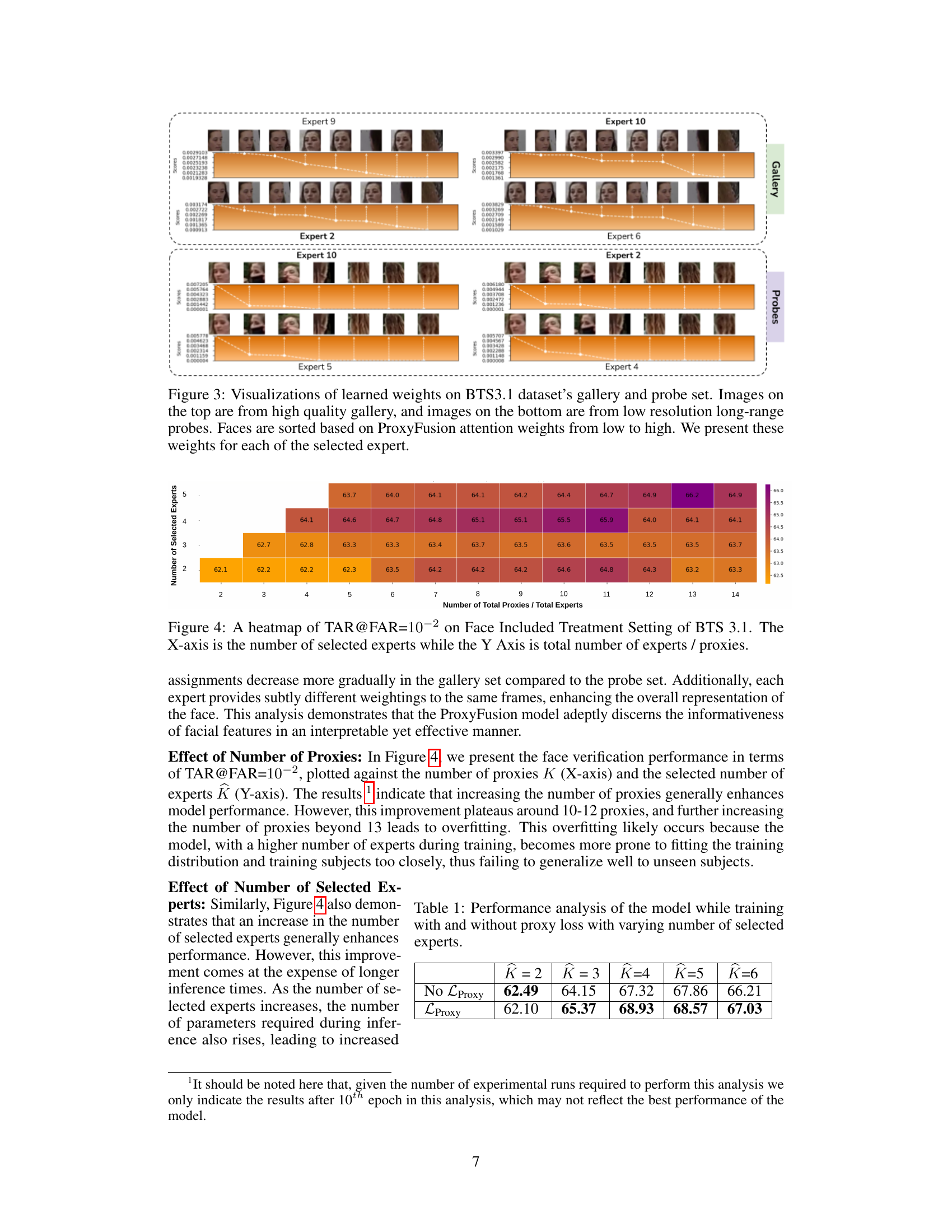

🔼 This heatmap shows the performance of the ProxyFusion model on the BTS 3.1 dataset’s Face Included Treatment Setting. The performance is measured by TAR@FAR=10-2 (True Acceptance Rate at a False Acceptance Rate of 10^-2). The X-axis represents the number of selected experts (out of the total number of experts/proxies), showing how choosing a subset of experts impacts performance. The Y-axis displays the total number of experts/proxies used in the model. The color intensity represents the TAR@FAR=10-2 value, with darker shades indicating better performance.

read the caption

Figure 4: A heatmap of TAR@FAR=10-2 on Face Included Treatment Setting of BTS 3.1. The X-axis is the number of selected experts while the Y Axis is total number of experts / proxies.

🔼 This figure visualizes the attention weights assigned by ProxyFusion to different faces in both gallery (high-quality) and probe (low-resolution, long-range) sets of the BTS3.1 dataset. The images are sorted for each expert by their assigned weights, showing that the model prioritizes high-quality, informative faces in both sets. Experts learn to focus on different aspects of face quality for the aggregation process, for example, prioritizing frontal or profile views and assigning less importance to faces with poor image quality.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visualizations of learned weights on BTS3.1 dataset's gallery and probe set. Images on the top are from high quality gallery, and images on the bottom are from low resolution long-range probes. Faces are sorted based on ProxyFusion attention weights from low to high. We present these weights for each of the selected expert.

More on tables

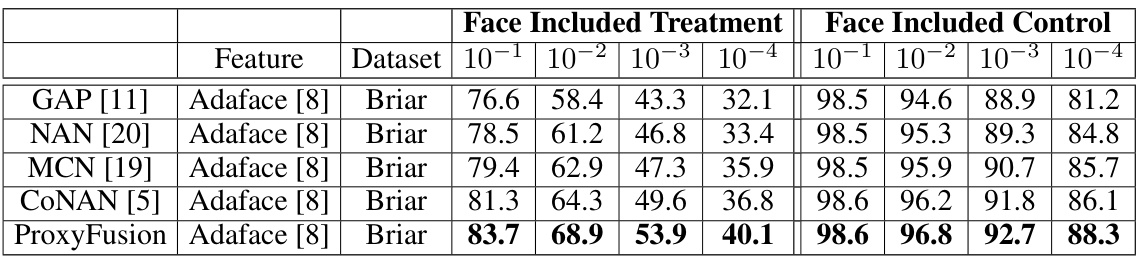

🔼 This table presents the verification performance, specifically True Acceptance Rate (TAR) at various False Acceptance Rates (FAR), for a face recognition system tested on the BRIAR BTS 3.1 dataset. The results are broken down by two settings: Face Included Treatment and Face Included Control. The feature extractor used was Adaface. The table compares the performance of ProxyFusion against other state-of-the-art methods.

read the caption

Table 3: Verification Performance (TAR (%) @FAR=%) for face included treatment and control protocols of the BTS 3.1 dataset. All faces are detected and algined using RetinaFace face detector.

🔼 This table presents the verification performance, measured by TAR (True Acceptance Rate) at various FAR (False Acceptance Rate) levels, for face recognition on the BRIAR BTS 3.1 dataset. It shows the results for both face-included treatment and control protocols. The comparison is made using the RetinaFace face detector for all methods. The table allows for an evaluation of the performance of different methods in different experimental conditions.

read the caption

Table 3: Verification Performance (TAR (%) @FAR=%) for face included treatment and control protocols of the BTS 3.1 dataset. All faces are detected and algined using RetinaFace face detector.

🔼 This table presents the verification performance results for the BRIAR BTS 3.1 dataset, comparing the True Acceptance Rate (TAR) at various False Acceptance Rates (FAR) for both face-included treatment and control conditions. The results are broken down by the feature extraction method used (Adaface [8]) and the face detection and alignment method (RetinaFace). The table allows for a comparison of the proposed ProxyFusion method against several other state-of-the-art methods in terms of accuracy.

read the caption

Table 3: Verification Performance (TAR (%) @FAR=%) for face included treatment and control protocols of the BTS 3.1 dataset. All faces are detected and algined using RetinaFace face detector.

Full paper#