TL;DR#

Forecasting future events is crucial for various sectors, but traditional methods are often expensive or limited in accuracy. This paper addresses these challenges by exploring the use of language models (LMs) for automated forecasting. Existing approaches primarily rely on statistical methods or human judgment, each having its own limitations. LMs offer a promising alternative due to their ability to process large amounts of information and generate forecasts efficiently.

This research developed a retrieval-augmented LM system that significantly improves forecasting accuracy. The system uses LMs to retrieve relevant information, generate forecasts, and aggregate predictions. Evaluated against a large dataset of forecasting questions, the system achieved results comparable to, and sometimes exceeding, those of human forecasters. This study demonstrates that LMs, coupled with appropriate techniques, can successfully automate forecasting tasks and contribute to more accurate predictions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI forecasting and related fields. It demonstrates the feasibility of achieving human-level forecasting accuracy using language models, opening exciting new avenues for research and applications. The work also provides a valuable large-scale dataset and detailed methodologies, contributing significantly to advancing the field. Its findings will likely influence the design of future AI forecasting systems and inspire further research into optimizing LM performance in this domain.

Visual Insights#

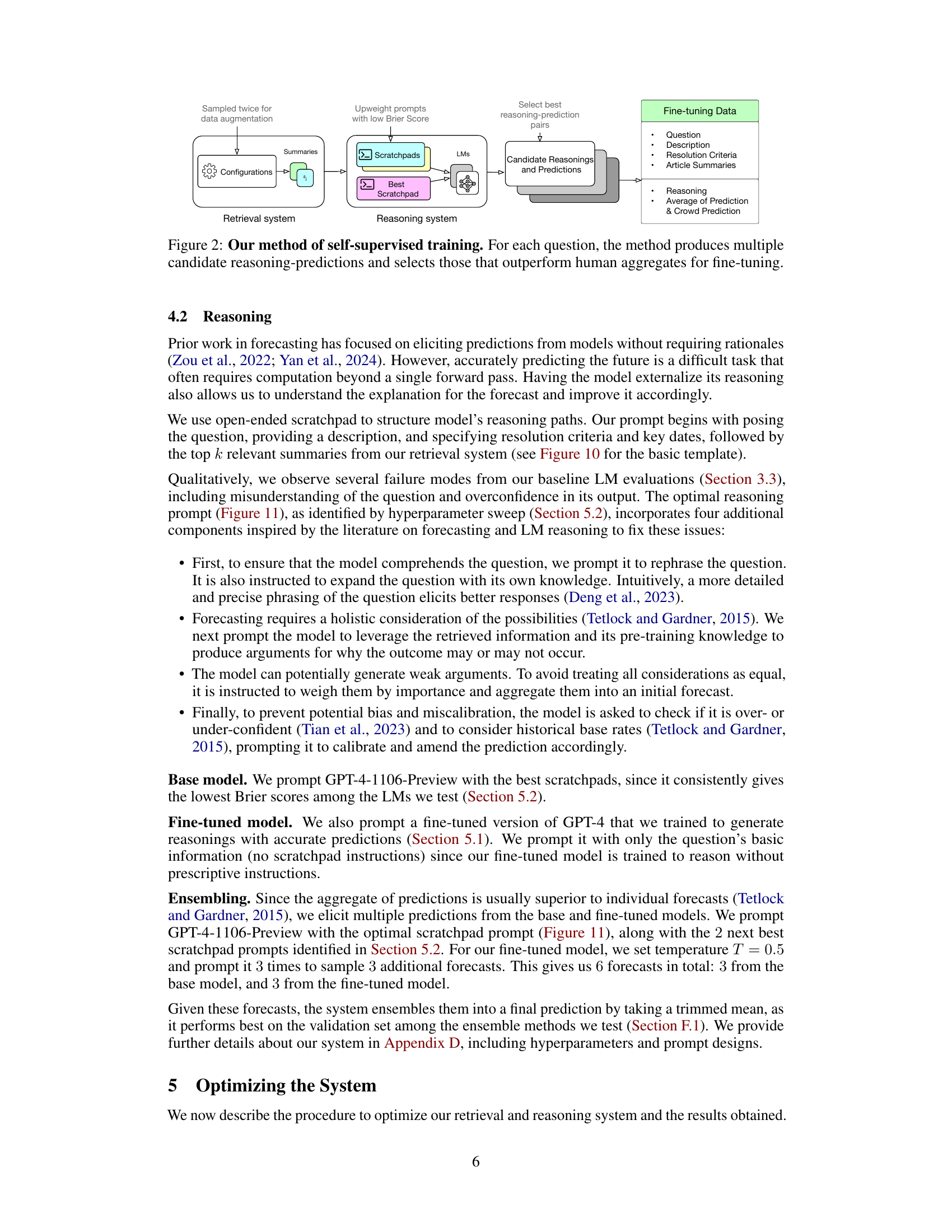

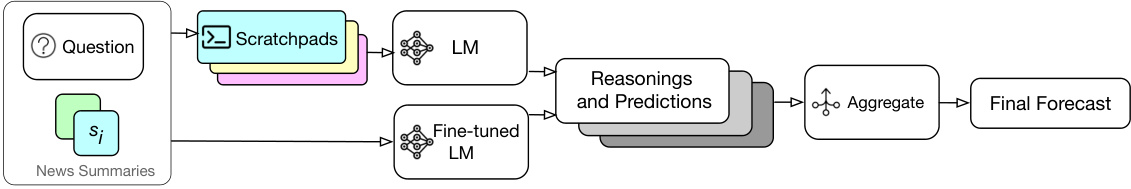

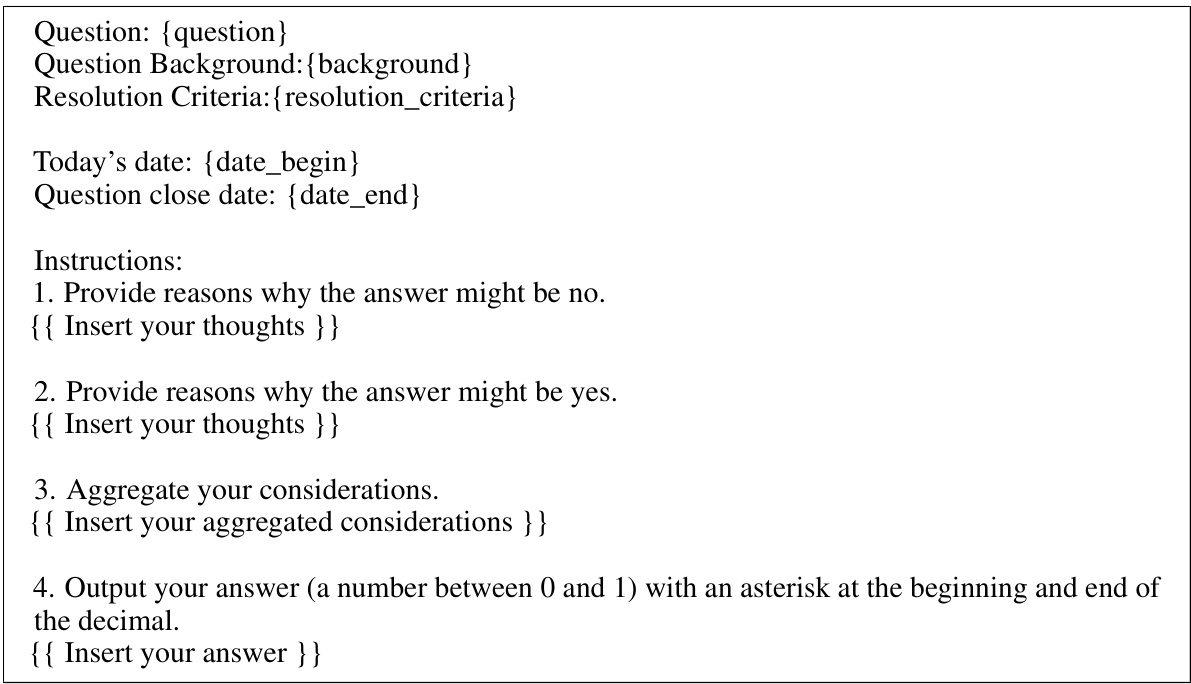

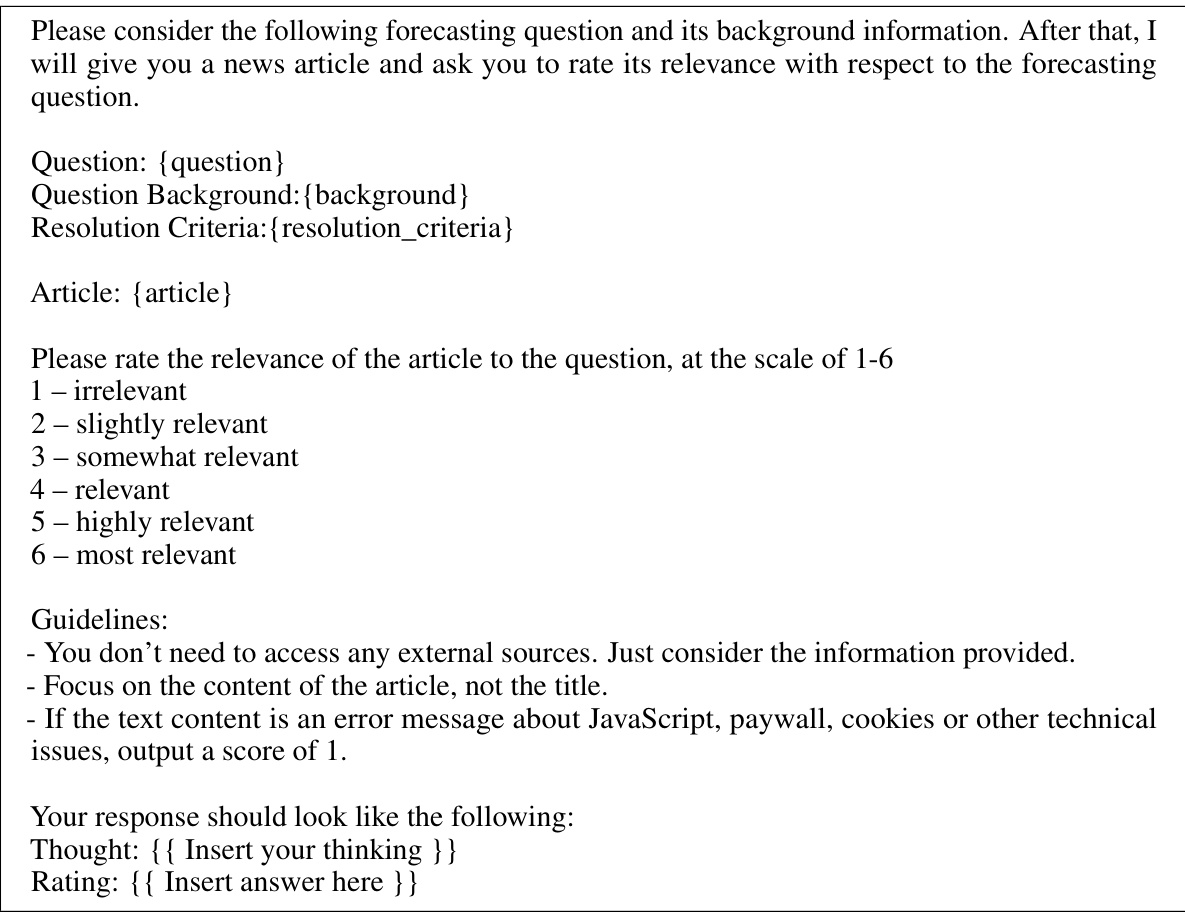

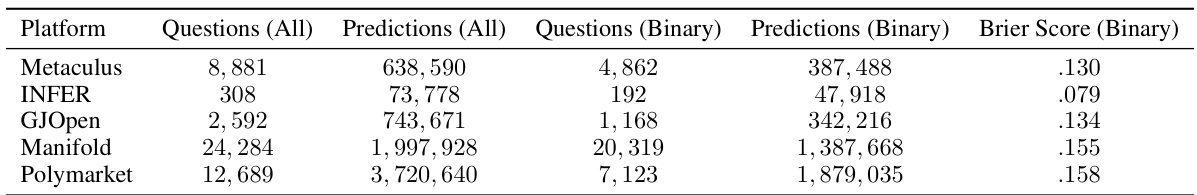

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main components of the proposed forecasting system: the retrieval system and the reasoning system. The retrieval system takes a question as input and uses a language model (LM) to generate search queries. These queries are used to retrieve relevant news articles from news APIs. The retrieved articles are then filtered and ranked by another LM based on their relevance to the question. Finally, the top k articles are summarized by the LM. The reasoning system takes the question and the summarized articles as input, prompts LMs to generate forecasts and reasonings, and aggregates the predictions to produce a final forecast. The system uses a trimmed mean to aggregate the individual forecasts.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our retrieval and reasoning systems. Our retrieval system retrieves summarized new articles and feeds them into the reasoning system, which prompts LMs for reasonings and predictions that are aggregated into a final forecast.

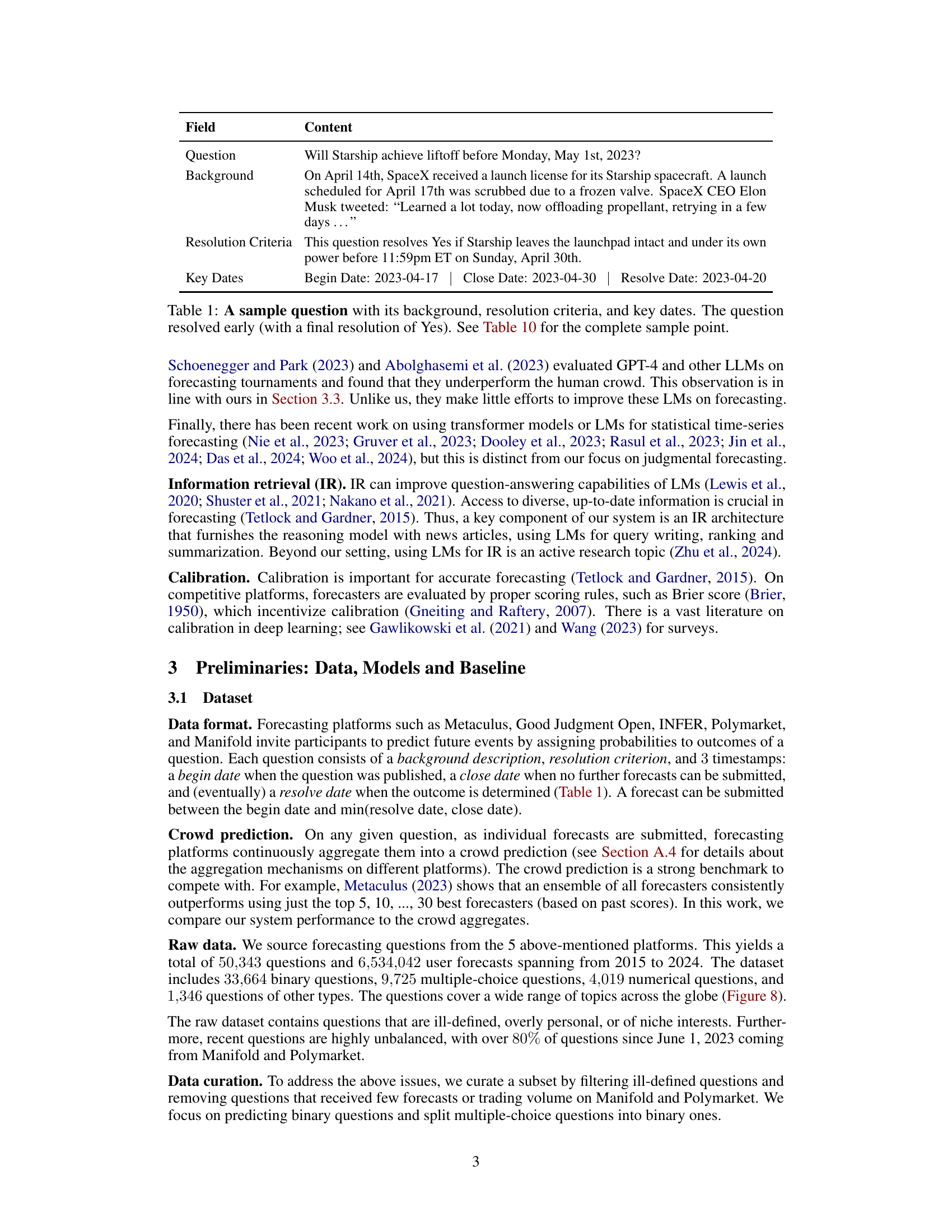

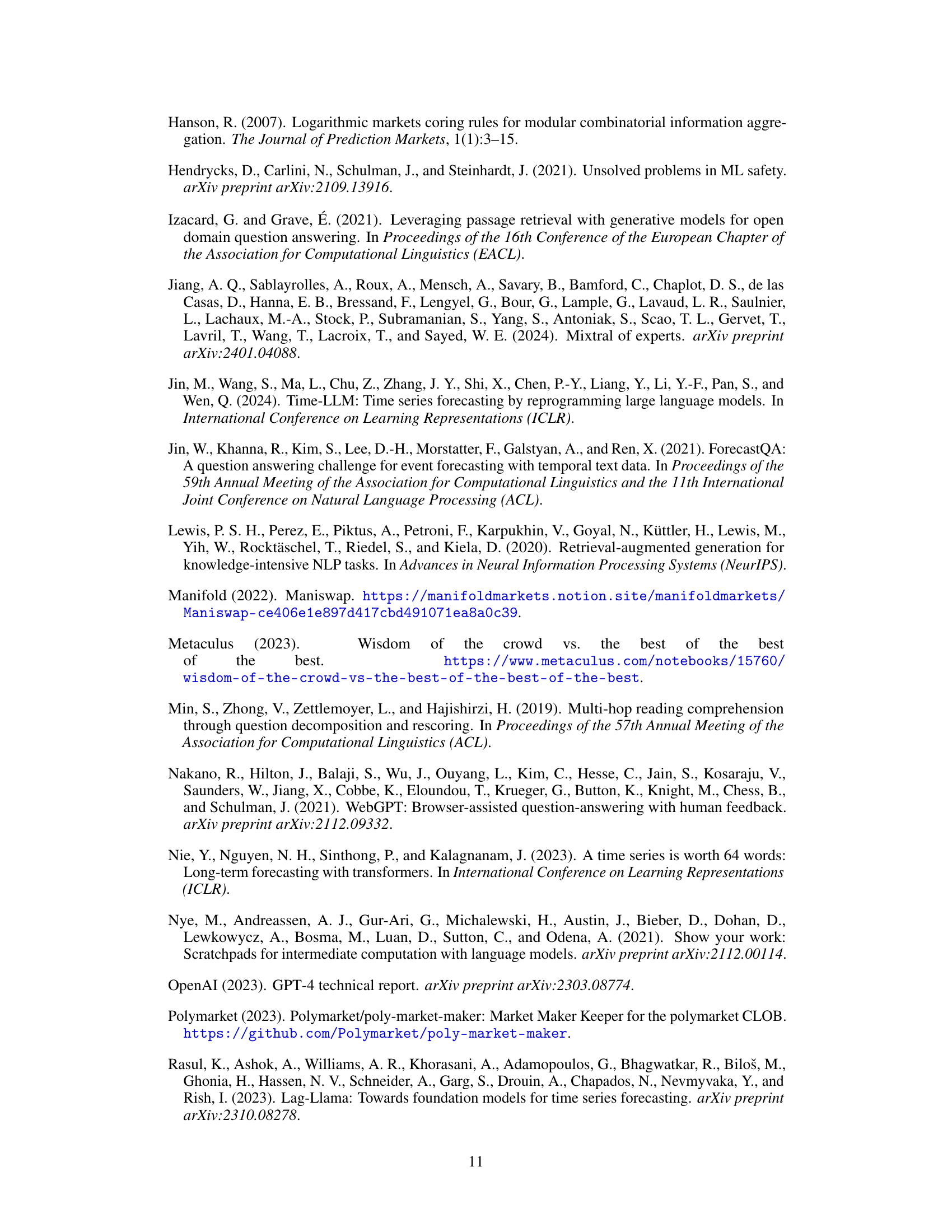

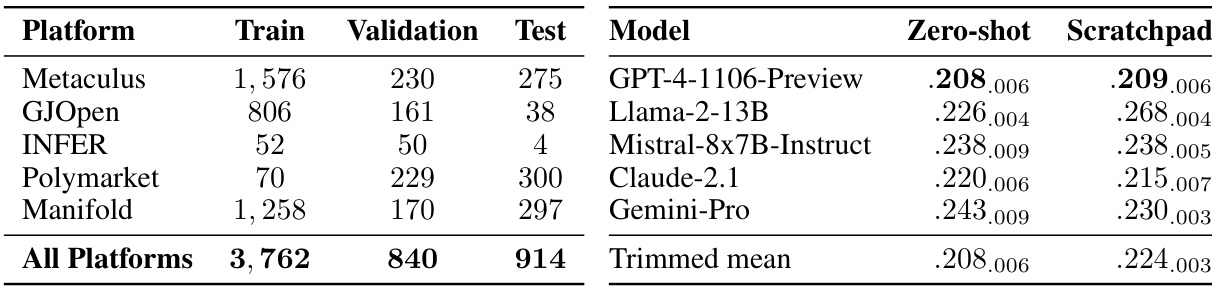

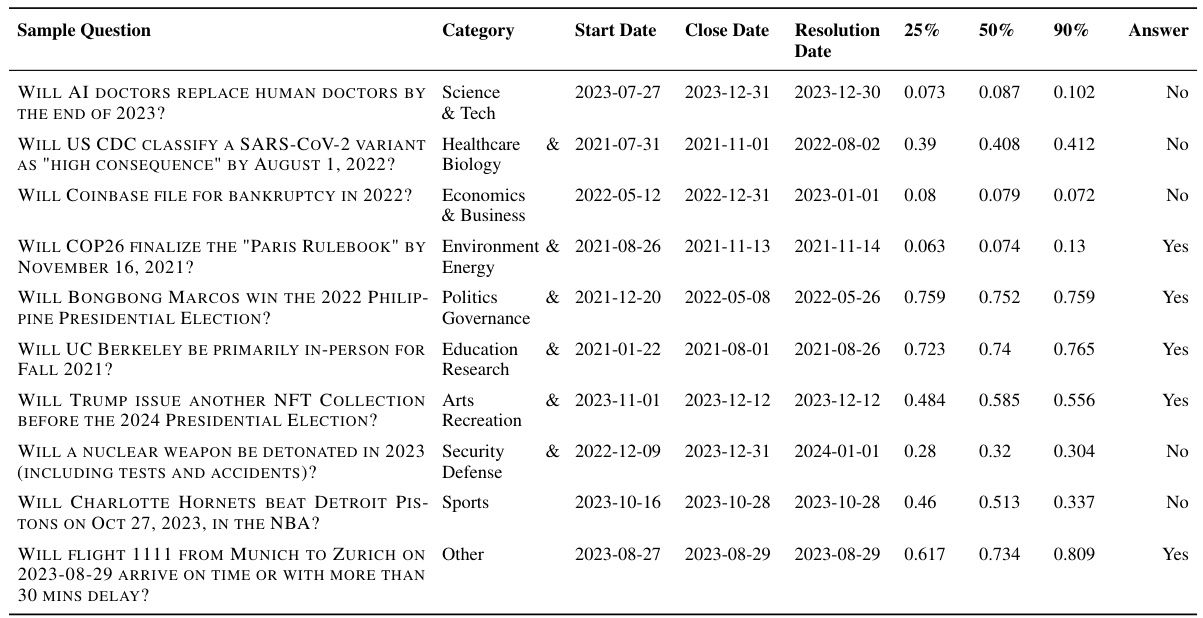

🔼 This table presents the data distribution across five forecasting platforms used in the study and the baseline performance of pre-trained language models on a test set. Table 2(a) shows the number of training, validation, and test questions from each platform. Table 2(b) displays the Brier scores (a measure of forecasting accuracy) for several pre-trained language models and provides a comparison to a random baseline and the performance of a crowd of human forecasters. The lower the Brier score, the better the performance. The human crowd serves as the benchmark.

read the caption

Table 2: (a) Distribution of our train, validation, and test sets across all 5 forecasting platforms. (b) Baseline performance of pre-trained models on the test set (see full results in Table 6). Subscript numbers denote 1 standard error. Random baseline: 0.25; human crowd: 0.149.

In-depth insights#

LM Forecasting#

This research explores the potential of large language models (LLMs) for forecasting. The core idea revolves around augmenting LLMs with information retrieval capabilities to enhance forecasting accuracy. The approach involves a multi-step process: retrieving relevant information from news sources, reasoning about this information to generate forecasts, and finally aggregating these forecasts to produce a final prediction. The study evaluates the system’s performance against human forecasters, demonstrating promising results. The system’s ability to combine information retrieval, reasoning, and aggregation is crucial to its success. However, limitations exist, such as the potential for overconfidence in the model’s predictions and the dependence on the quality of information retrieval. Future work could focus on addressing these limitations and expanding the range of tasks for which LM-based forecasting can be effectively applied.

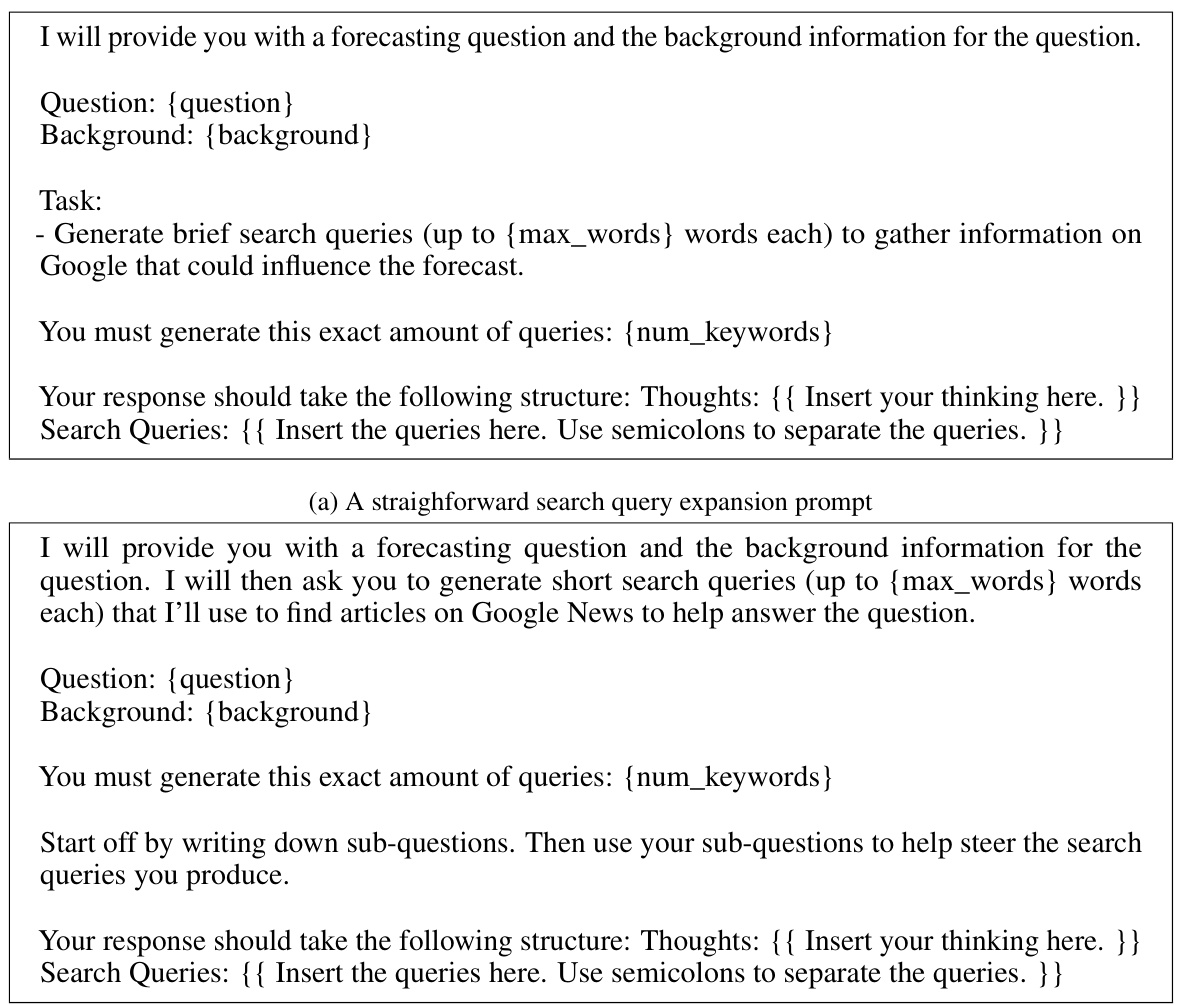

Retrieval System#

A robust retrieval system is crucial for any AI-powered forecasting model, as it provides the contextual information necessary for accurate predictions. The effectiveness of such a system hinges on several key aspects: search query generation, which should be sophisticated enough to capture the nuances of the forecasting question and retrieve relevant information from multiple sources; news retrieval, requiring access to a vast and reliable news corpus; relevance filtering and re-ranking, to filter out irrelevant information and ensure that only the most pertinent articles are considered; and finally, text summarization, to condense lengthy articles into concise summaries suitable for language model processing. The retrieval system’s overall design should aim for both high recall (retrieving most relevant information) and high precision (minimizing irrelevant information), ultimately supporting the reasoning and forecasting components of the system.

Reasoning Models#

Reasoning models are crucial for advanced artificial intelligence, especially in domains requiring complex decision-making. They aim to mimic human-like reasoning by incorporating logical inference, causal reasoning, and commonsense knowledge. Effective reasoning models are essential for building trustworthy AI systems, capable of explaining their decisions and handling uncertainty. Several key techniques are used in developing these models, including knowledge graphs, probabilistic logic, and deep learning architectures. The choice of reasoning model greatly impacts the performance and interpretability of the AI system. For instance, rule-based systems provide transparency but lack flexibility, while deep learning models offer high accuracy but can be opaque. Therefore, hybrid approaches combining rule-based systems with machine learning are also being explored to leverage the strengths of both. Future research should focus on developing more robust and general-purpose reasoning models that can handle diverse reasoning tasks, and on improving the explainability and trustworthiness of these models. The development of benchmark datasets to evaluate reasoning models is also a critical aspect for future progress.

Fine-tuning LM#

Fine-tuning large language models (LLMs) for forecasting presents unique challenges. Directly training on outcome labels can lead to poorly calibrated predictions, where the model’s confidence doesn’t accurately reflect its accuracy. A more effective approach involves a self-supervised method, generating multiple reasoning-prediction pairs. This allows for selecting and prioritizing those instances where the model’s predictions surpass human aggregates. This process, by using the model’s outperformance as a signal of quality, forms a high-quality training dataset. Furthermore, fine-tuning aims to address limitations such as model overconfidence and misinterpretations of the questions. The process not only improves prediction accuracy but also encourages the model to develop more robust and explainable reasoning skills. The self-supervised technique helps mitigate the scarcity of high-quality human-written rationales needed for effective supervised fine-tuning. In essence, fine-tuning refines the LLM’s ability to leverage contextual information and generate calibrated probability estimates. This is particularly crucial for forecasting applications which demand well-calibrated and reliable predictions.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could significantly advance the field of automated forecasting. Improving the self-supervised fine-tuning approach with a larger training corpus would allow for iterative model improvements and potentially lead to more accurate and reliable predictions. Investigating and addressing the LM’s tendency to hedge predictions is crucial. This could involve exploring methods to improve the model’s calibration or developing prompting strategies that elicit more decisive forecasts. Improving the news retrieval system is also key, as the accuracy of the forecasts depends heavily on the quality and relevance of the information retrieved. This involves exploring techniques such as advanced query generation and more effective filtering methods. Finally, exploring domain-adaptive training techniques would allow for the development of specialized forecasting models tailored to specific domains, leading to more accurate and nuanced predictions.

More visual insights#

More on figures

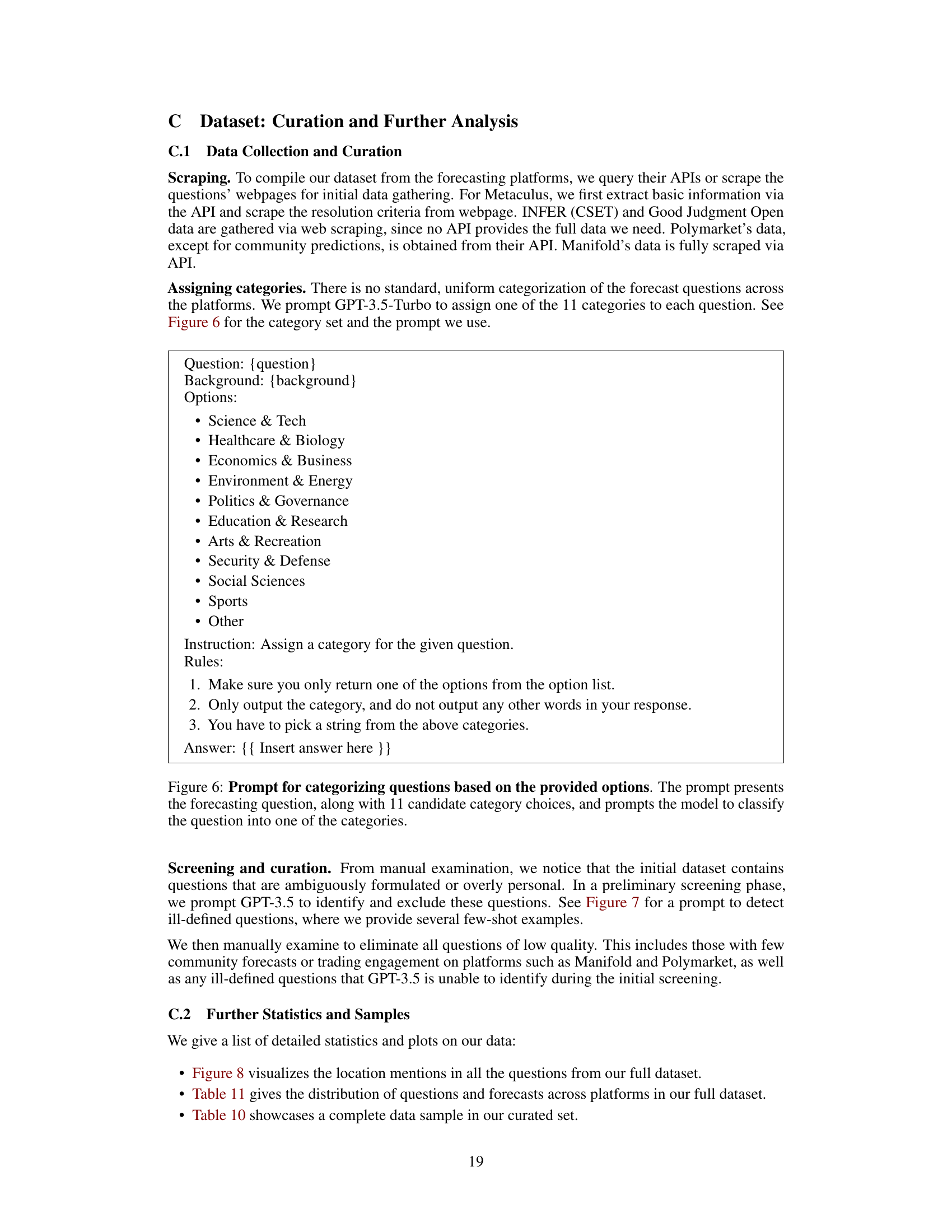

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main components of the proposed forecasting system: the retrieval system and the reasoning system. The retrieval system uses a language model (LM) to generate search queries based on the input question, retrieves relevant news articles from a news API, ranks the articles by relevance, and summarizes the top k articles. The reasoning system takes the summarized articles and the input question as input and prompts two LMs (a base LM and a fine-tuned LM) to generate forecasts and their reasoning. These forecasts are then aggregated using a trimmed mean to produce the final forecast.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our retrieval and reasoning systems. Our retrieval system retrieves summarized new articles and feeds them into the reasoning system, which prompts LMs for reasonings and predictions that are aggregated into a final forecast.

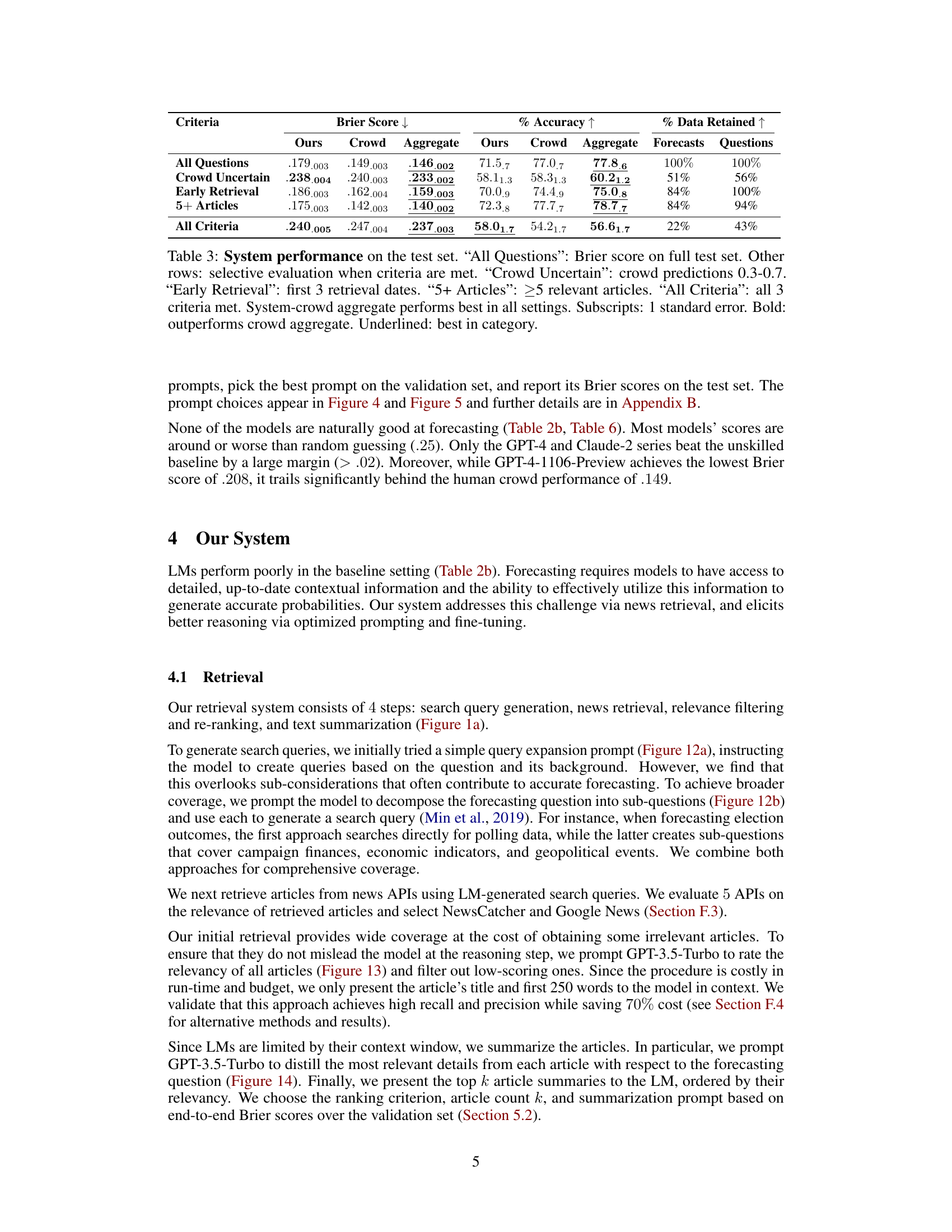

🔼 This figure illustrates the self-supervised training process used to improve the accuracy of the language model in forecasting. The system generates multiple reasoning-prediction pairs for each question by varying prompts and retrieval configurations. It then selects the pairs that outperform human forecasts based on Brier score. These selected reasoning-prediction pairs are used as training data to fine-tune the language model, enhancing its forecasting accuracy. Data augmentation is employed by sampling twice for each configuration.

read the caption

Figure 2: Our method of self-supervised training. For each question, the method produces multiple candidate reasoning-predictions and selects those that outperform human aggregates for fine-tuning.

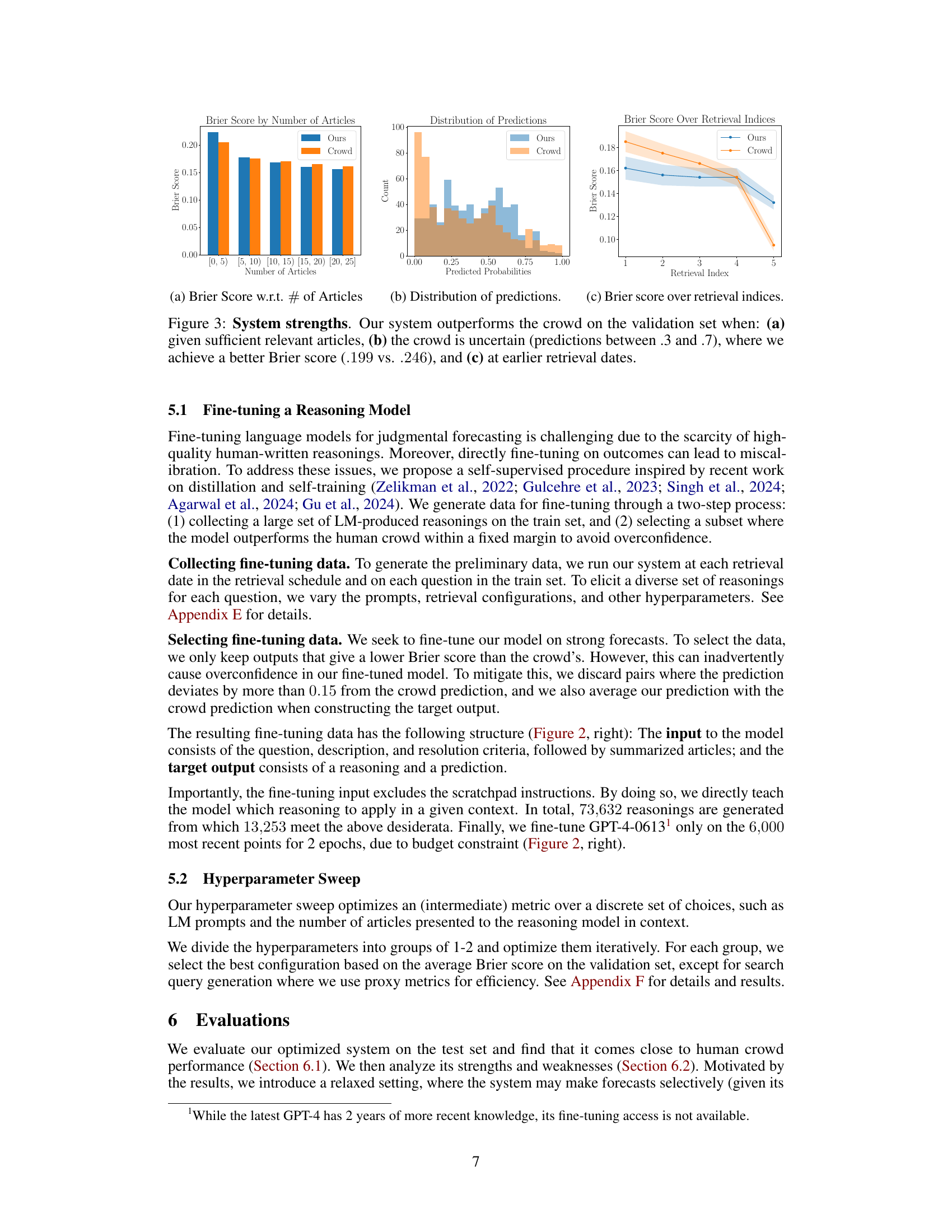

🔼 This figure shows three plots that demonstrate the strengths of the proposed forecasting system. The first plot shows the Brier score as a function of the number of relevant articles retrieved. The second plot shows the distribution of predictions for both the proposed system and the crowd. The third plot shows the Brier score over retrieval indices, indicating how the system’s performance changes as the model is given more information over time. In all three cases, the system shows improved performance over the crowd, demonstrating its effectiveness under specific conditions.

read the caption

Figure 3: System strengths. Our system outperforms the crowd on the validation set when: (a) given sufficient relevant articles, (b) the crowd is uncertain (predictions between .3 and .7), where we achieve a better Brier score (.199 vs. .246), and (c) at earlier retrieval dates.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main components of the authors’ forecasting system: a retrieval system and a reasoning system. The retrieval system uses language models (LMs) to formulate search queries, retrieve relevant news articles, filter out irrelevant articles, and summarize the top k articles. The summarized articles are then fed into the reasoning system, which utilizes LMs to generate forecasts and reasonings based on the input information. These individual forecasts are aggregated to produce a final, consolidated forecast.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our retrieval and reasoning systems. Our retrieval system retrieves summarized new articles and feeds them into the reasoning system, which prompts LMs for reasonings and predictions that are aggregated into a final forecast.

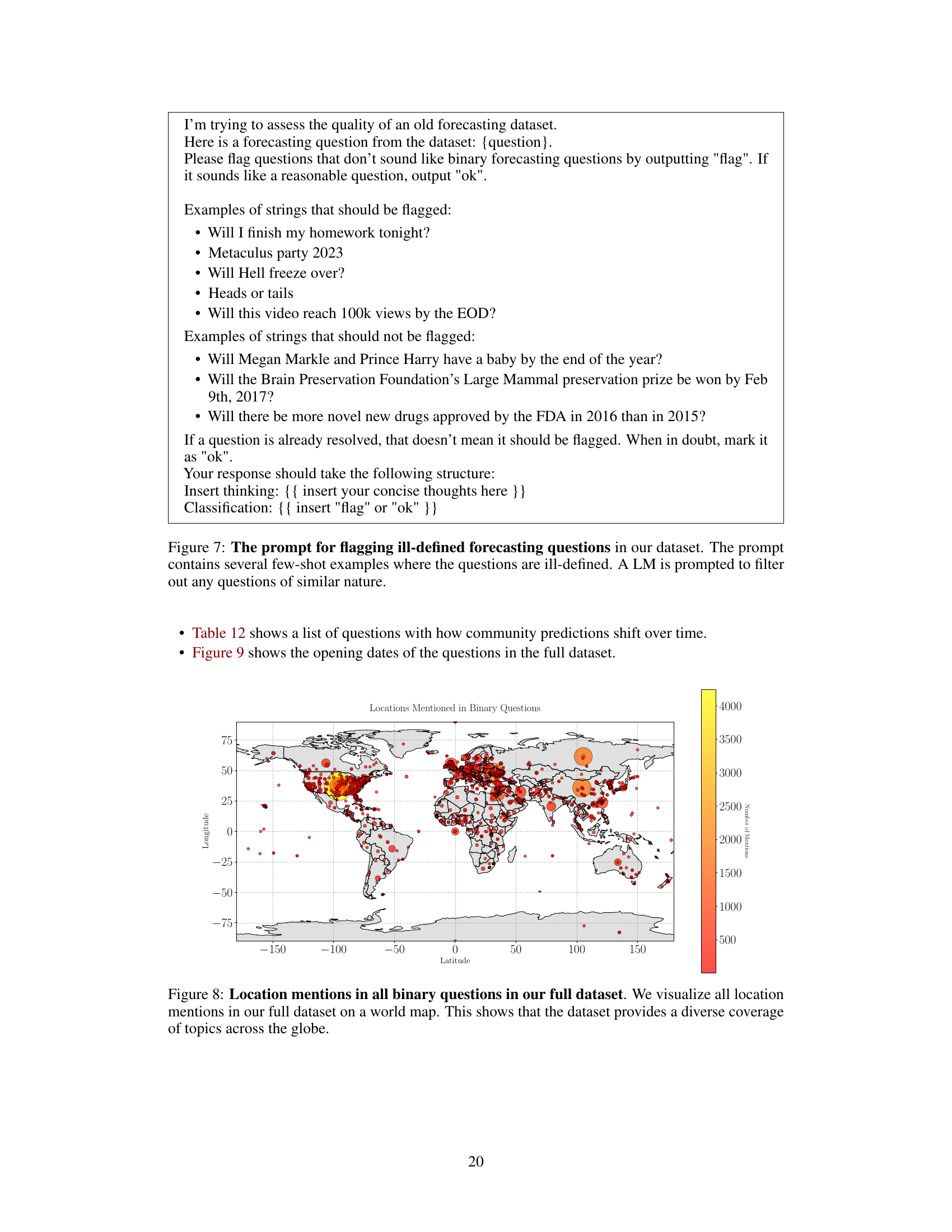

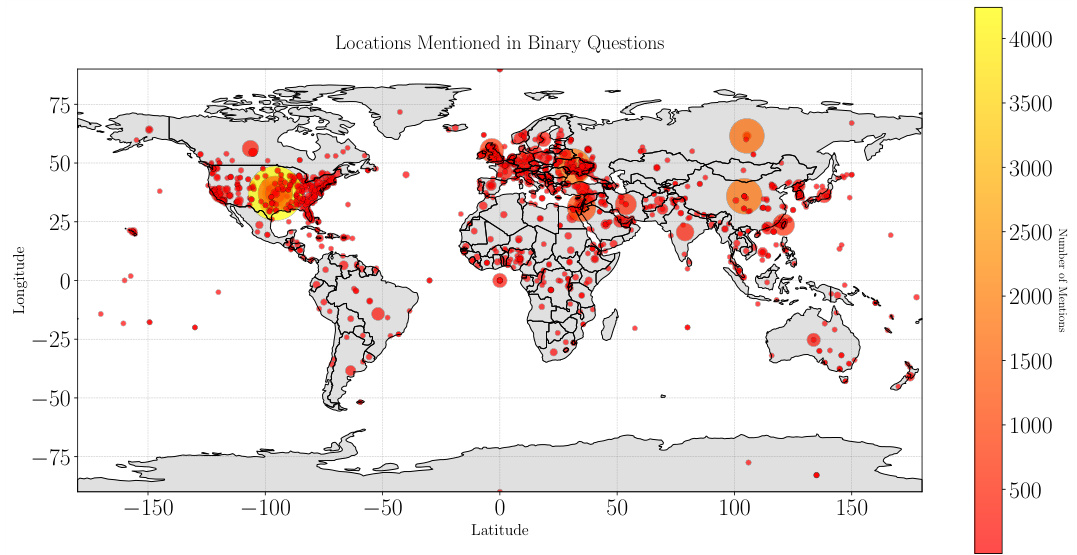

🔼 This figure is a world map visualizing the geographic distribution of the topics covered in the binary questions of the dataset. The size of each point corresponds to the number of questions mentioning that specific location, representing the concentration of questions in different regions. The map demonstrates a diverse geographical spread of topics in the dataset, covering various regions around the world.

read the caption

Figure 8: Location mentions in all binary questions in our full dataset. We visualize all location mentions in our full dataset on a world map. This shows that the dataset provides a diverse coverage of topics across the globe.

🔼 This figure shows three bar charts that compare the performance of the proposed system against a crowd baseline on different scenarios. It highlights the superiority of the system when more relevant articles are available, when the crowd is less certain about the prediction, and when the system has access to information earlier. Each chart visually demonstrates the system’s strengths and superiority in different contexts and scenarios.

read the caption

System strengths. Our system outperforms the crowd on the validation set when: (a) given sufficient relevant articles, (b) the crowd is uncertain (predictions between .3 and .7), where we achieve a better Brier score (.199 vs. .246), and (c) at earlier retrieval dates.

🔼 This figure shows a schematic of the authors’ proposed system for forecasting. It’s composed of two main parts: a retrieval system and a reasoning system. The retrieval system uses an LM to generate search queries, retrieve relevant news articles, filter out irrelevant articles, and summarize the top k articles. The reasoning system takes these summaries and the original question as input. Then, another LM generates forecasts and reasonings. Finally, all these predictions are aggregated into a final forecast using the trimmed mean.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our retrieval and reasoning systems. Our retrieval system retrieves summarized new articles and feeds them into the reasoning system, which prompts LMs for reasonings and predictions that are aggregated into a final forecast.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main components of the proposed forecasting system: the retrieval system and the reasoning system. The retrieval system takes a question as input and uses a language model (LM) to generate search queries to find relevant news articles. The retrieved articles are then summarized by the LM, and these summaries are passed to the reasoning system. The reasoning system uses another LM to generate forecasts based on the summarized articles and the original question. These individual forecasts are then aggregated to produce a final forecast.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our retrieval and reasoning systems. Our retrieval system retrieves summarized new articles and feeds them into the reasoning system, which prompts LMs for reasonings and predictions that are aggregated into a final forecast.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two main components of the authors’ forecasting system: the retrieval system and the reasoning system. The retrieval system takes a question as input and uses an LM to generate search queries. These queries are used to retrieve articles from news APIs. The LM then ranks these articles by relevance and summarizes the top k articles. These summaries are fed into the reasoning system. The reasoning system also uses an LM to generate forecasts and reasonings based on the question and article summaries. These individual forecasts are then aggregated using the trimmed mean to produce a final forecast.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of our retrieval and reasoning systems. Our retrieval system retrieves summarized new articles and feeds them into the reasoning system, which prompts LMs for reasonings and predictions that are aggregated into a final forecast.

🔼 This figure demonstrates the strengths of the proposed forecasting system by comparing its performance against the crowd’s predictions on the validation set under different conditions. Panel (a) shows that the system performs better with more relevant articles. Panel (b) illustrates improved performance when the crowd’s predictions are uncertain (probabilities between 0.3 and 0.7). Finally, Panel (c) indicates that the system’s predictions are more accurate with early retrieval dates.

read the caption

Figure 3: System strengths. Our system outperforms the crowd on the validation set when: (a) given sufficient relevant articles, (b) the crowd is uncertain (predictions between .3 and .7), where we achieve a better Brier score (.199 vs. .246), and (c) at earlier retrieval dates.

More on tables

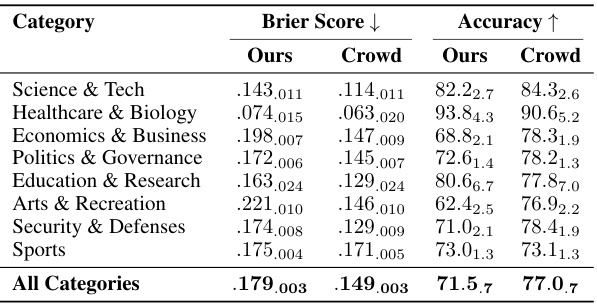

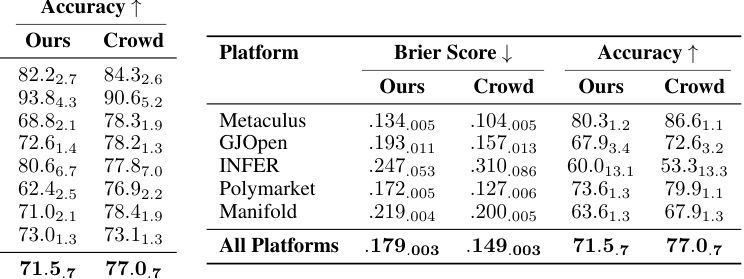

🔼 This table presents the distribution of the training, validation, and test datasets across five different forecasting platforms. The second part shows the baseline performance (Brier score and standard error) of several pre-trained language models on the test set, comparing them to a random baseline and the average performance of human forecasters.

read the caption

Table 2: (a) Distribution of our train, validation, and test sets across all 5 forecasting platforms. (b) Baseline performance of pre-trained models on the test set (see full results in Table 6). Subscript numbers denote 1 standard error. Random baseline: 0.25; human crowd: 0.149.

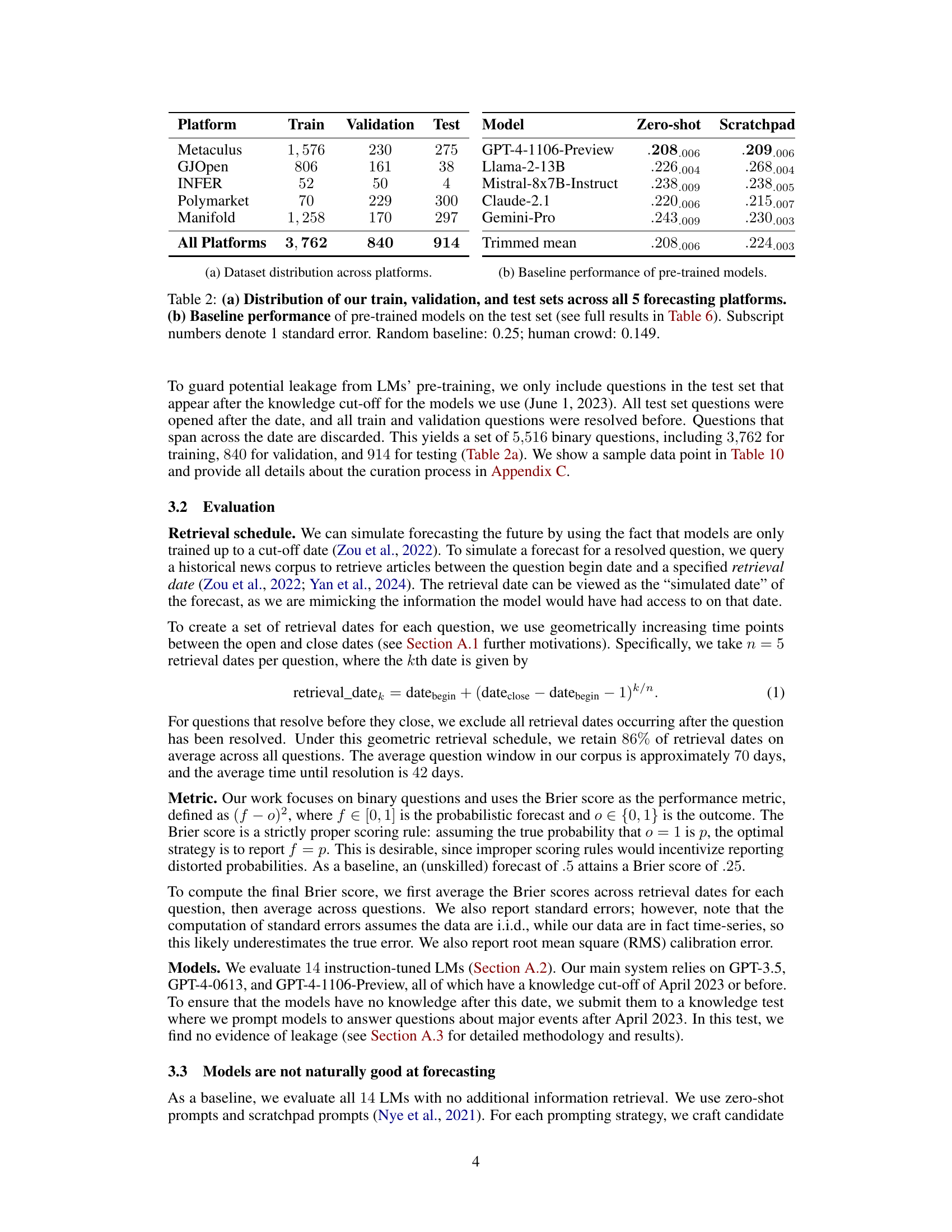

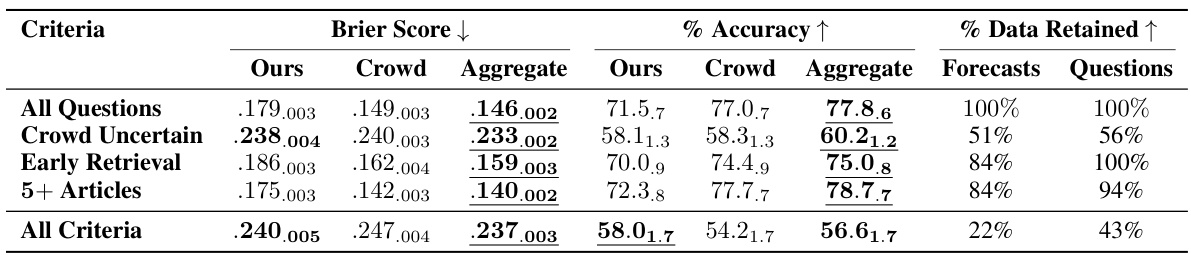

🔼 This table presents the performance of the proposed forecasting system on a test set of questions, broken down by different criteria. It shows Brier scores (lower is better), accuracy (higher is better), and the percentage of data retained for each criterion. The criteria include considering only questions where crowd predictions show uncertainty, focusing on results from early retrieval attempts, and looking only at questions with at least 5 relevant articles. It also shows a final combined analysis for when all criteria are met. The results are compared to the performance of the human crowd. The table also indicates where the system outperformed the crowd.

read the caption

Table 3: System performance on the test set. 'All Questions': Brier score on full test set. Other rows: selective evaluation when criteria are met. 'Crowd Uncertain': crowd predictions 0.3–0.7. 'Early Retrieval': first 3 retrieval dates. “5+ Articles”: ≥5 relevant articles. “All Criteria”: all 3 criteria met. System-crowd aggregate performs best in all settings. Subscripts: 1 standard error. Bold: outperforms crowd aggregate. Underlined: best in category.

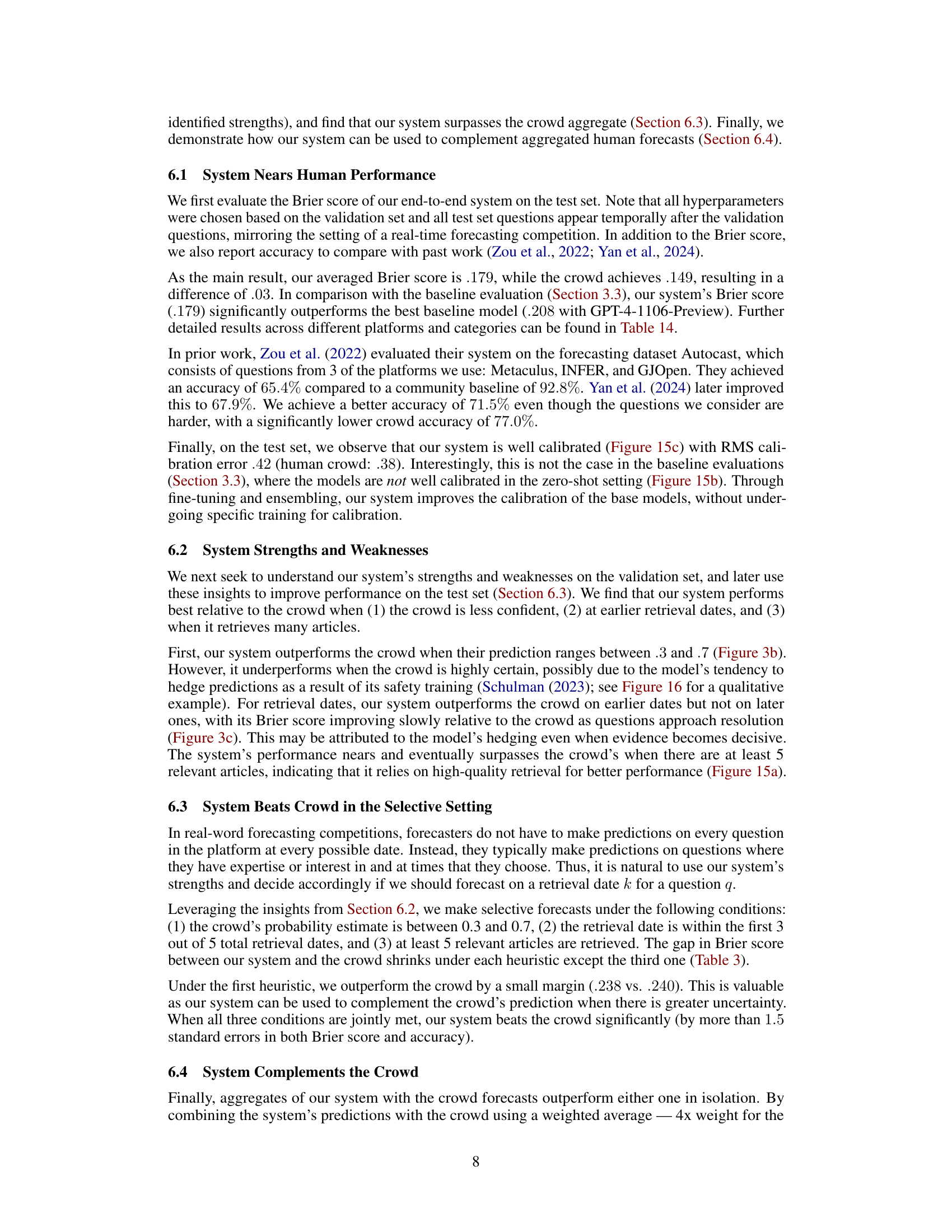

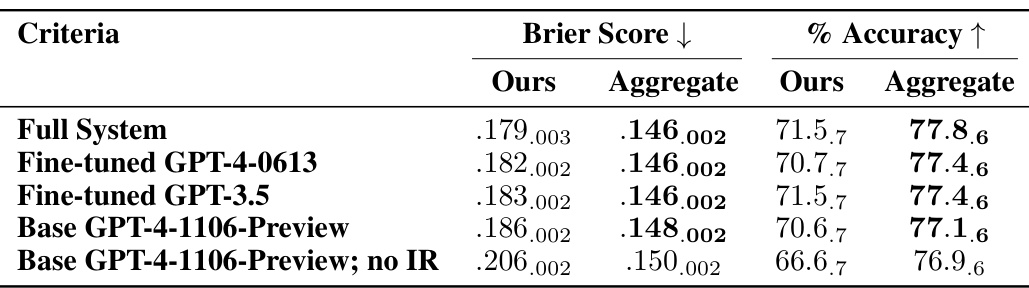

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results, showing the impact of different components of the proposed forecasting system on its performance. It compares the full system’s performance against versions where either fine-tuning or the retrieval system were removed. The results highlight the importance of both fine-tuning and retrieval for achieving near human-level forecasting accuracy. The Brier score and accuracy are reported, with statistical significance indicated using standard errors. The ‘Aggregate’ column shows the weighted average performance combining the system’s predictions and the crowd’s.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation results: Fine-tuning GPT-3.5 has similar performance to fine-tuning GPT-4-0613 (rows 2-3). Our system degrades without fine-tuning (row 4) or retrieval (row 5), as expected. 'Aggregate' is the weighted average with crowd prediction. Subscripts are standard errors; bold entries beat the human crowd.

🔼 This table presents the data distribution of the training, validation, and test sets across five different forecasting platforms. It also shows the baseline performance of several pre-trained language models on the test set, measured by Brier score, with standard errors indicated. A random baseline and the human crowd performance are included for comparison.

read the caption

Table 2: (a) Distribution of our train, validation, and test sets across all 5 forecasting platforms. (b) Baseline performance of pre-trained models on the test set (see full results in Table 6). Subscript numbers denote 1 standard error. Random baseline: 0.25; human crowd: 0.149.

🔼 This table presents the distribution of the training, validation, and test datasets across five different forecasting platforms. It then shows the baseline performance of various pre-trained language models on the test set, measured by the Brier score and accuracy, with standard errors included. A random baseline and the human crowd’s performance are also provided for comparison.

read the caption

Table 2: (a) Distribution of our train, validation, and test sets across all 5 forecasting platforms. (b) Baseline performance of pre-trained models on the test set (see full results in Table 6). Subscript numbers denote 1 standard error. Random baseline: 0.25; human crowd: 0.149.

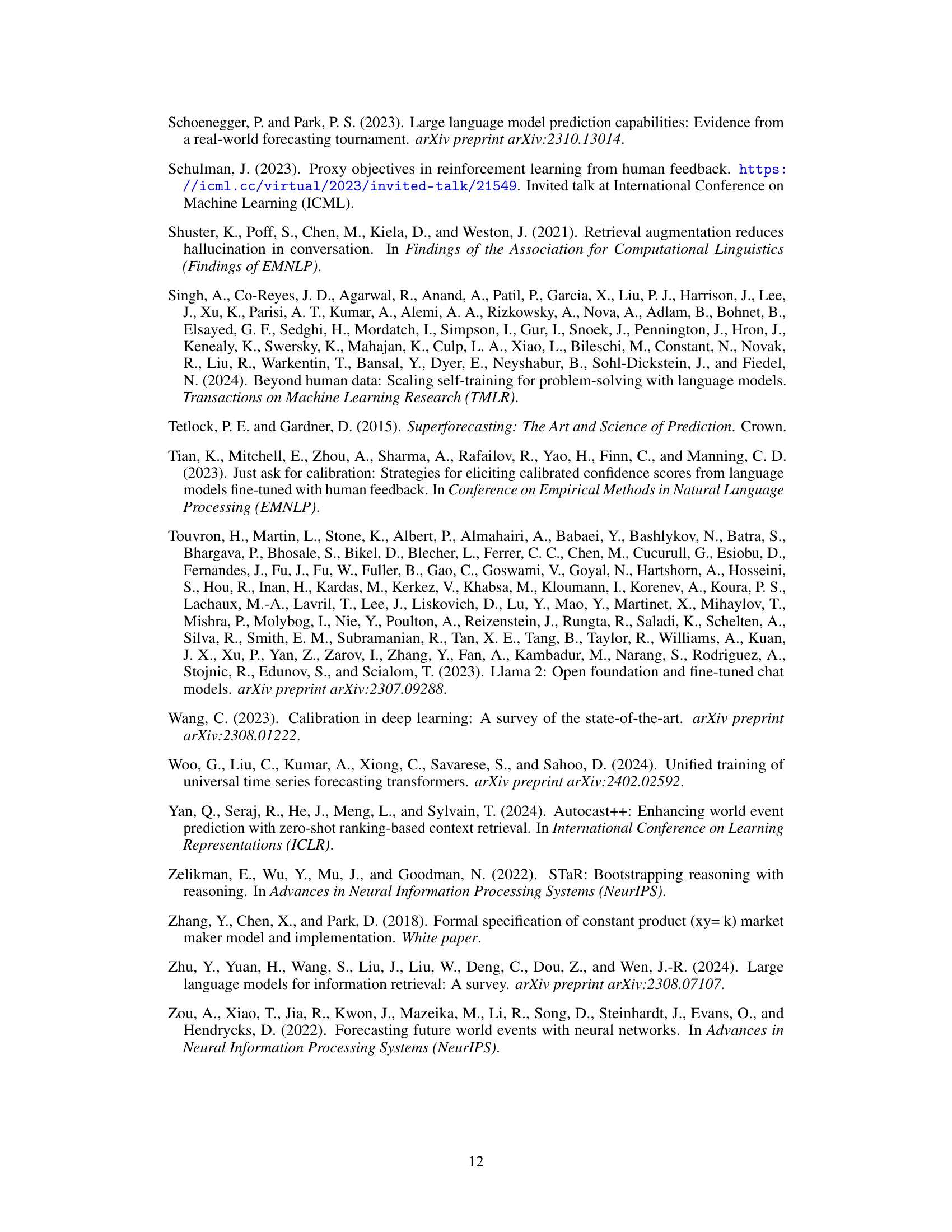

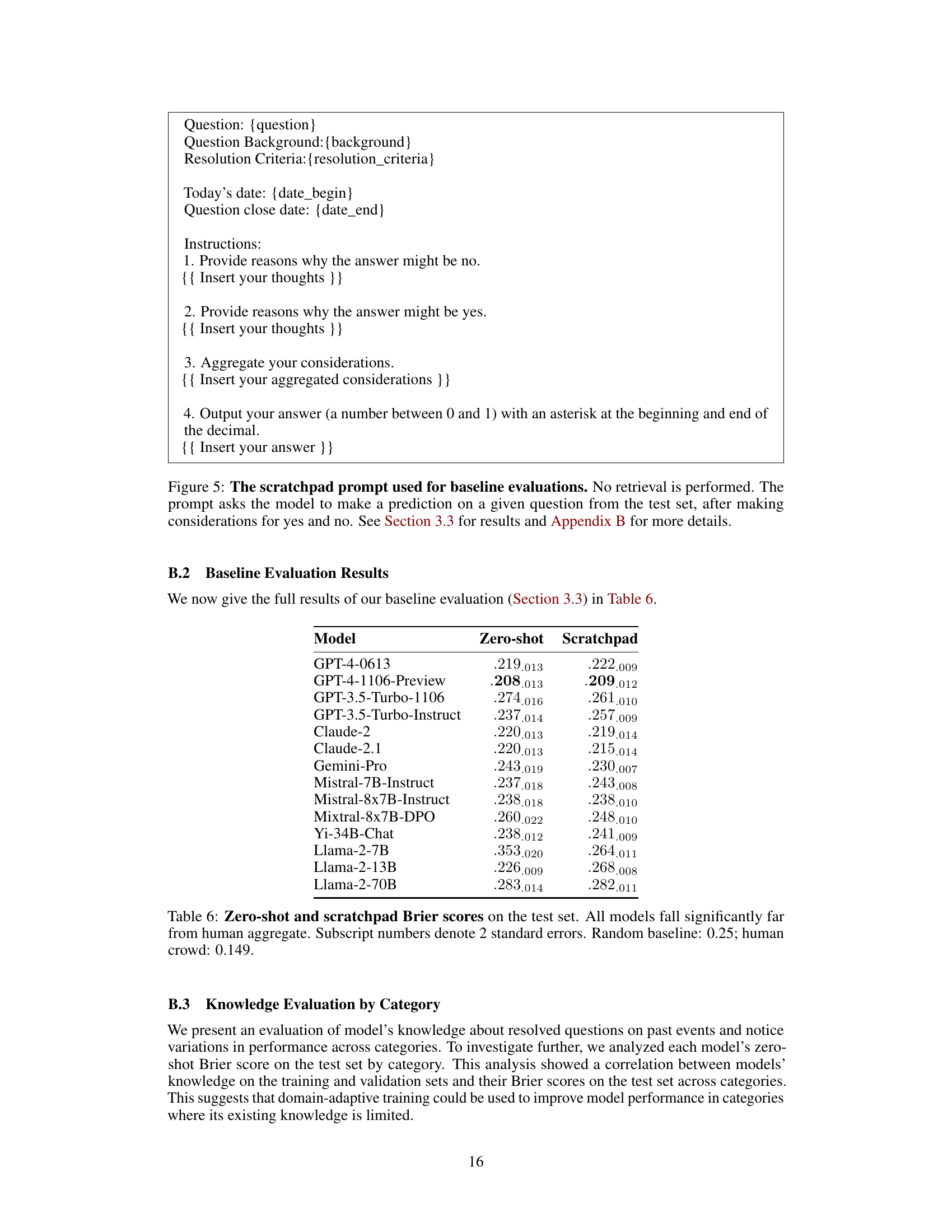

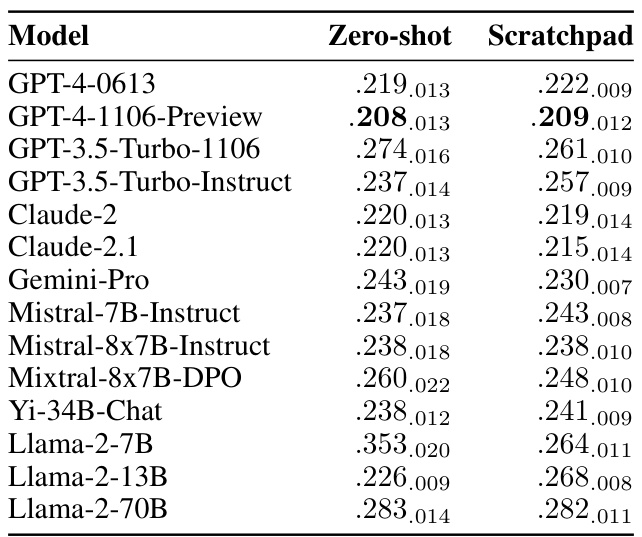

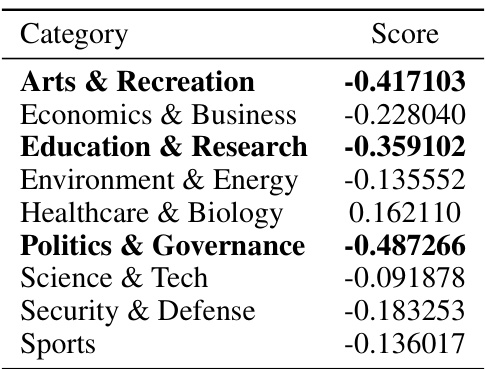

🔼 This table shows the knowledge accuracy of 14 different Language Models (LMs) across 11 different categories. The knowledge accuracy is measured by the percentage of correctly answered questions from the training and validation datasets. The results highlight the varying performance of different LMs in different knowledge domains.

read the caption

Table 7: Comparison of knowledge accuracy across categories and models on the train and validation sets. We list the knowledge accuracy of all base models with respect to all categories in the train and validation set.

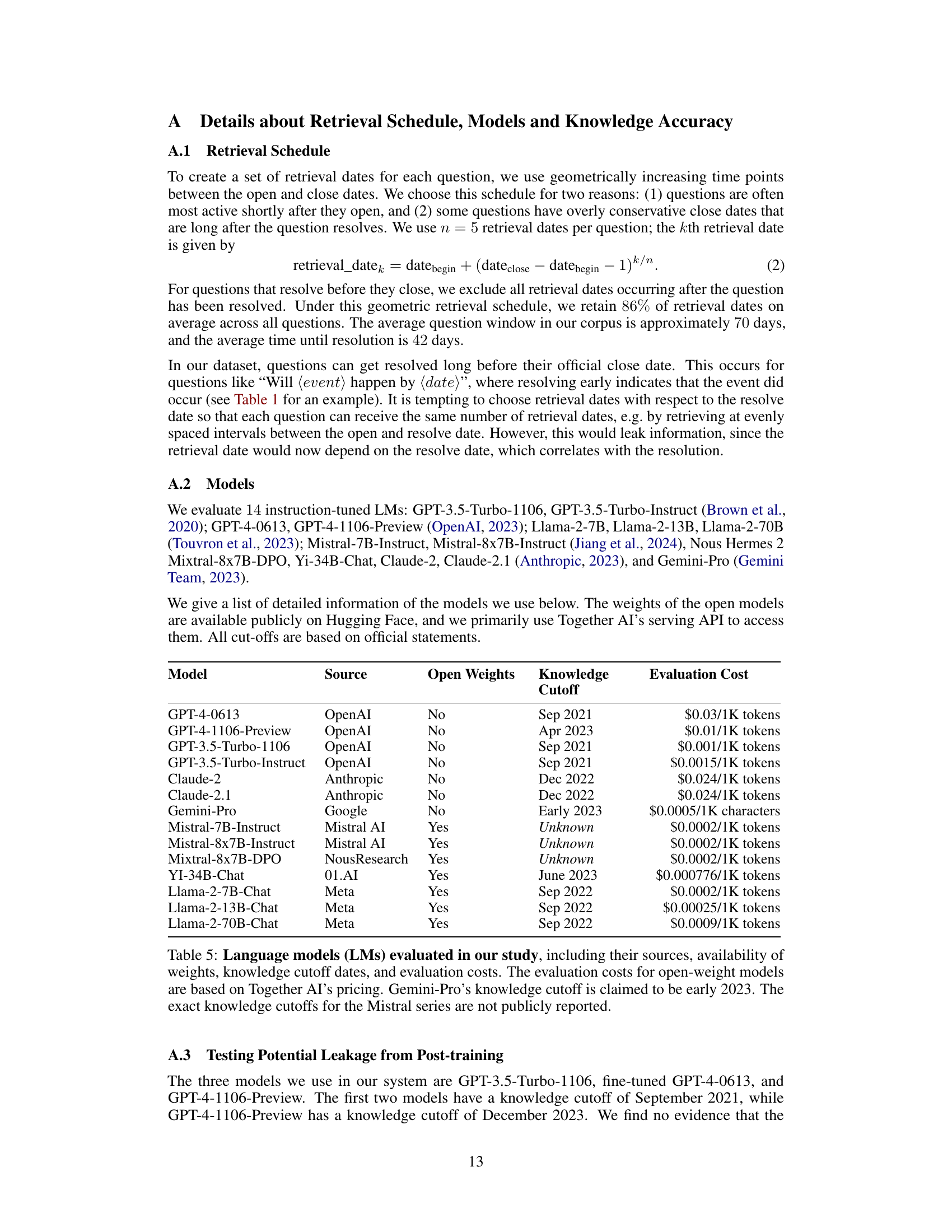

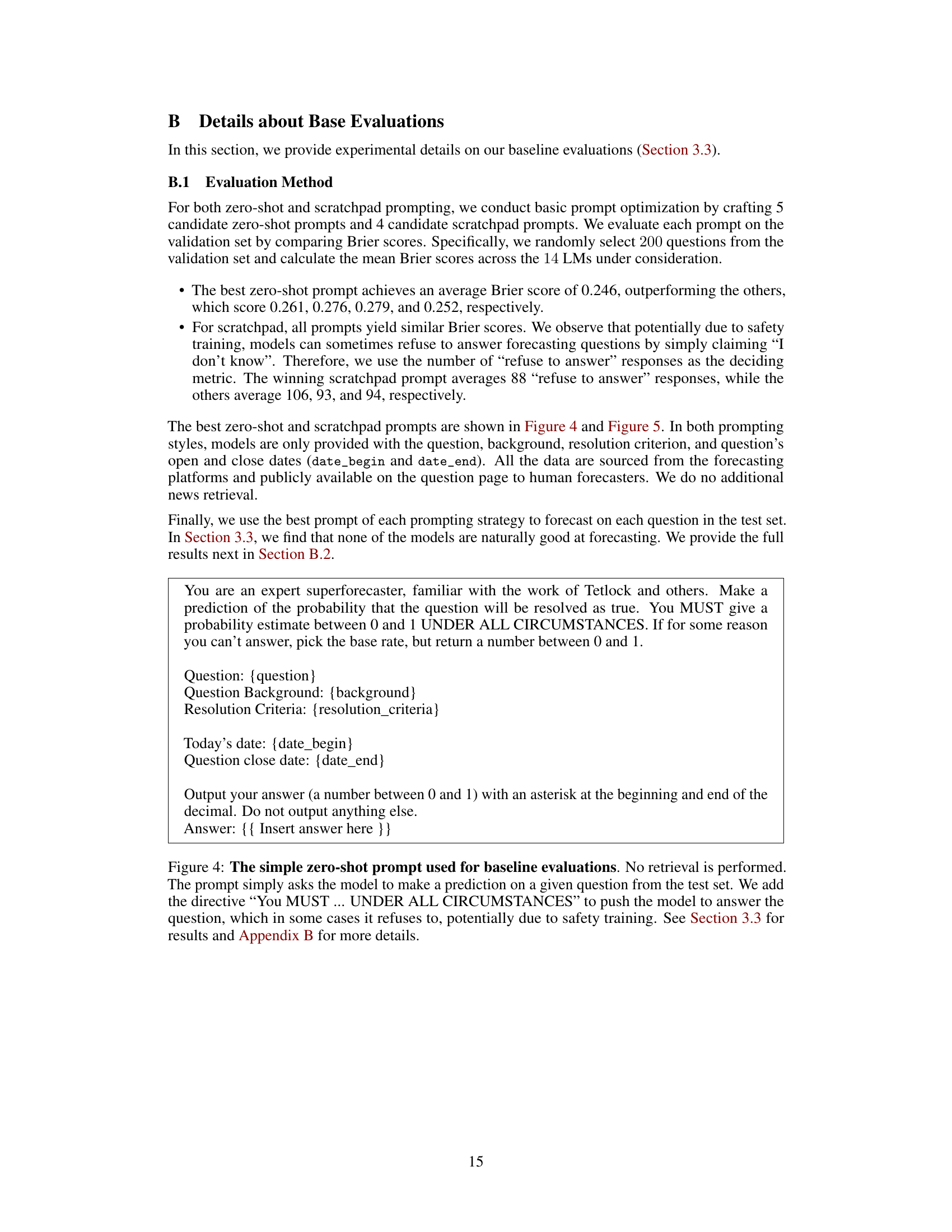

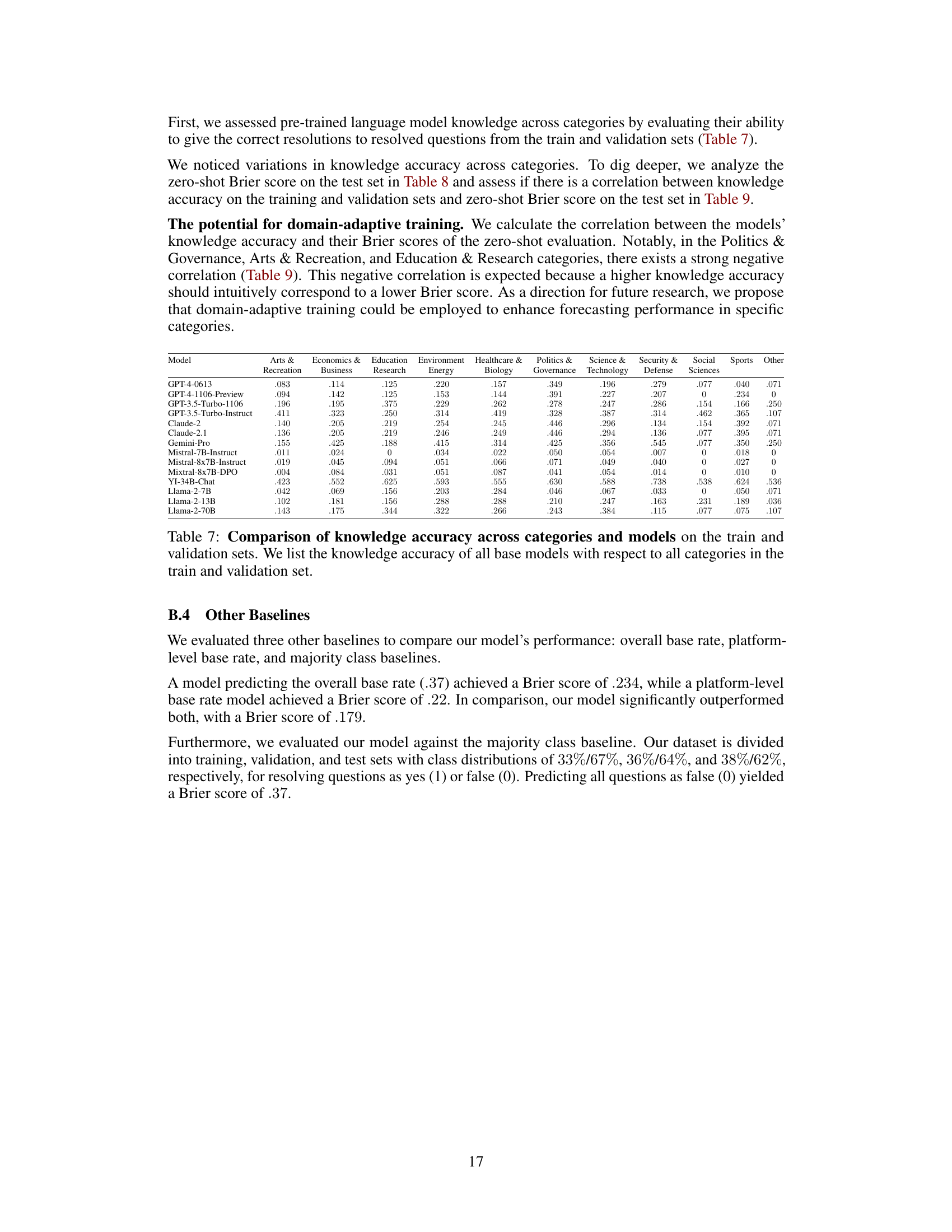

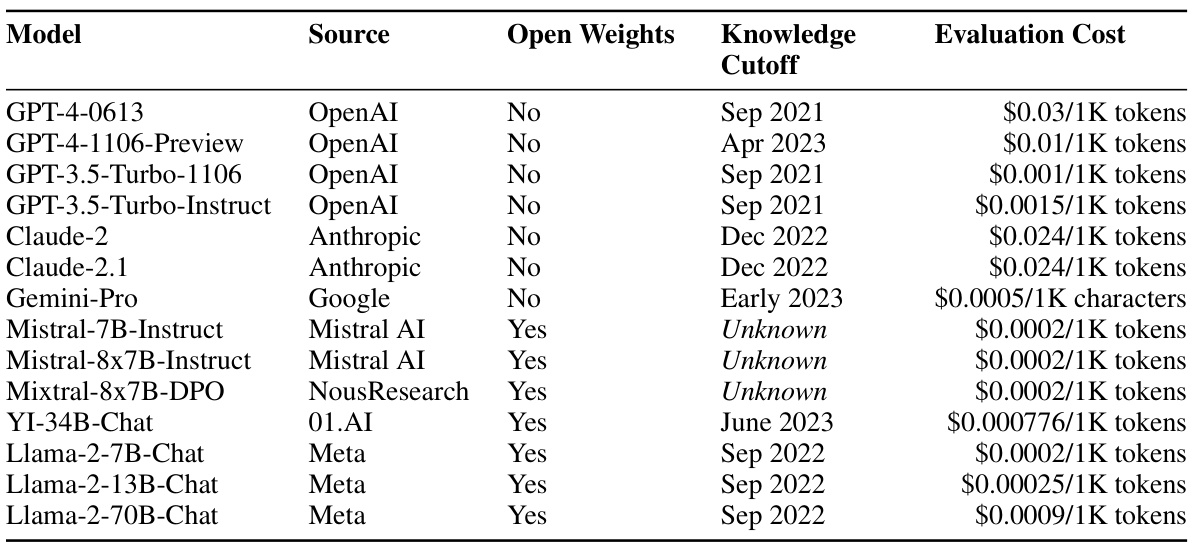

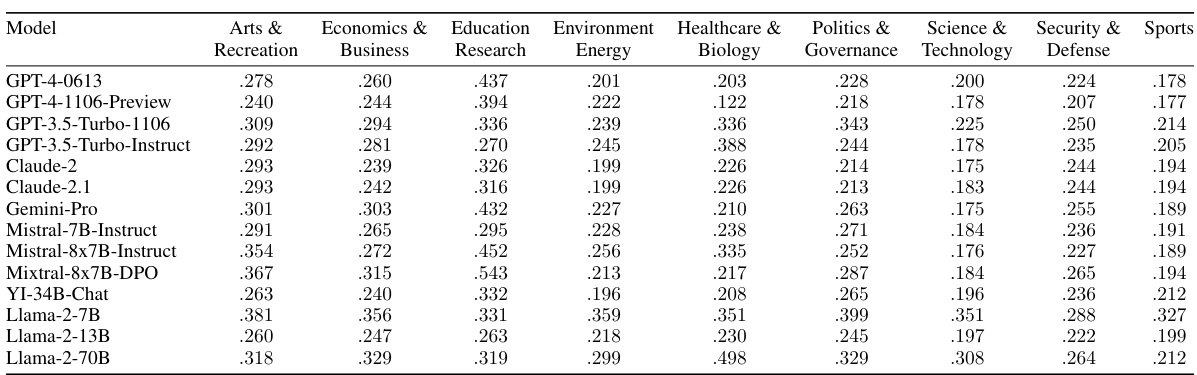

🔼 This table presents the Brier scores achieved by fourteen different language models on a test set, categorized by two prompting methods: zero-shot and scratchpad. The results highlight the significant underperformance of these models compared to the human crowd’s aggregated performance, even with the more sophisticated scratchpad prompting.

read the caption

Table 6: Zero-shot and scratchpad Brier scores on the test set. All models fall significantly far from human aggregate. Subscript numbers denote 2 standard errors. Random baseline: 0.25; human crowd: 0.149.

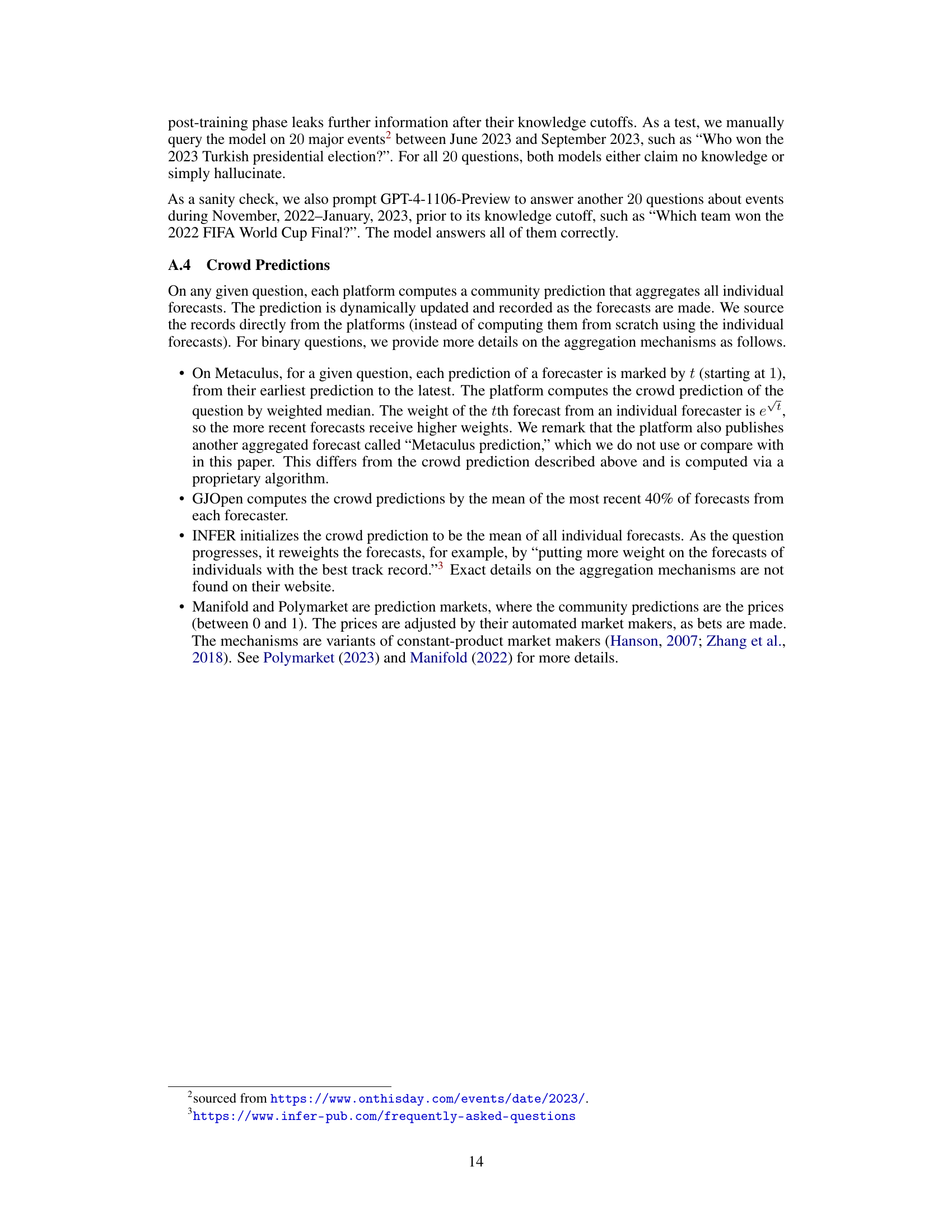

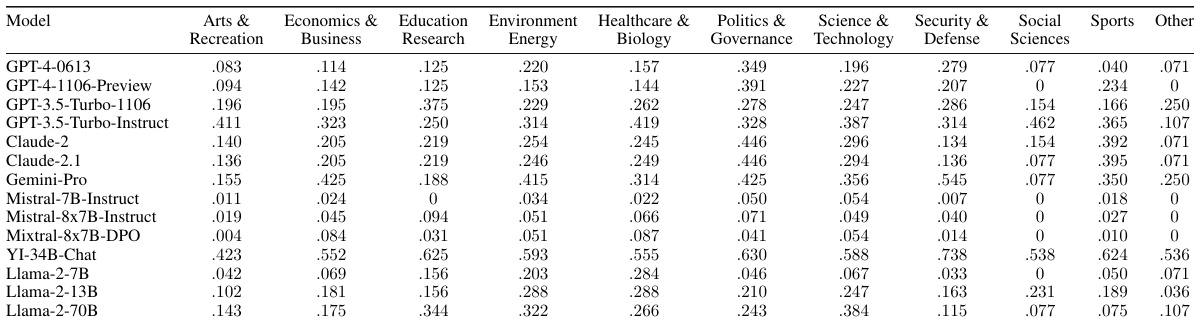

🔼 This table shows the correlation between the model’s knowledge accuracy (based on its performance on training and validation sets) and its Brier score (a measure of forecast accuracy) on the test set, broken down by category. Strong negative correlations (shown in bold) indicate that better knowledge in a particular category leads to better forecasting performance in that category. This suggests the potential benefit of domain-adaptive training, where models are specifically trained for certain categories to improve accuracy.

read the caption

Table 9: Correlation between knowledge accuracy and zero-shot prompt Brier score by category. Categories with an absolute correlation of 0.3 or greater, shown in bold, indicate a high correlation between accuracy on the training and validation set and forecasting performance on the test set. This highlights that in certain domains model’s forecasting capabilities are correlated with its pre-training knowledge.

🔼 This table presents the distribution of training, validation, and test datasets across five different forecasting platforms (Metaculus, GJOpen, INFER, Polymarket, and Manifold). It also shows the baseline performance (Brier score and accuracy) of several pre-trained language models on the test set. The subscript numbers indicate one standard error. The table provides a baseline to compare against, showing the performance of pre-trained models before any further optimization or fine-tuning.

read the caption

Table 2: (a) Distribution of our train, validation, and test sets across all 5 forecasting platforms. (b) Baseline performance of pre-trained models on the test set (see full results in Table 6). Subscript numbers denote 1 standard error. Random baseline: 0.25; human crowd: 0.149.

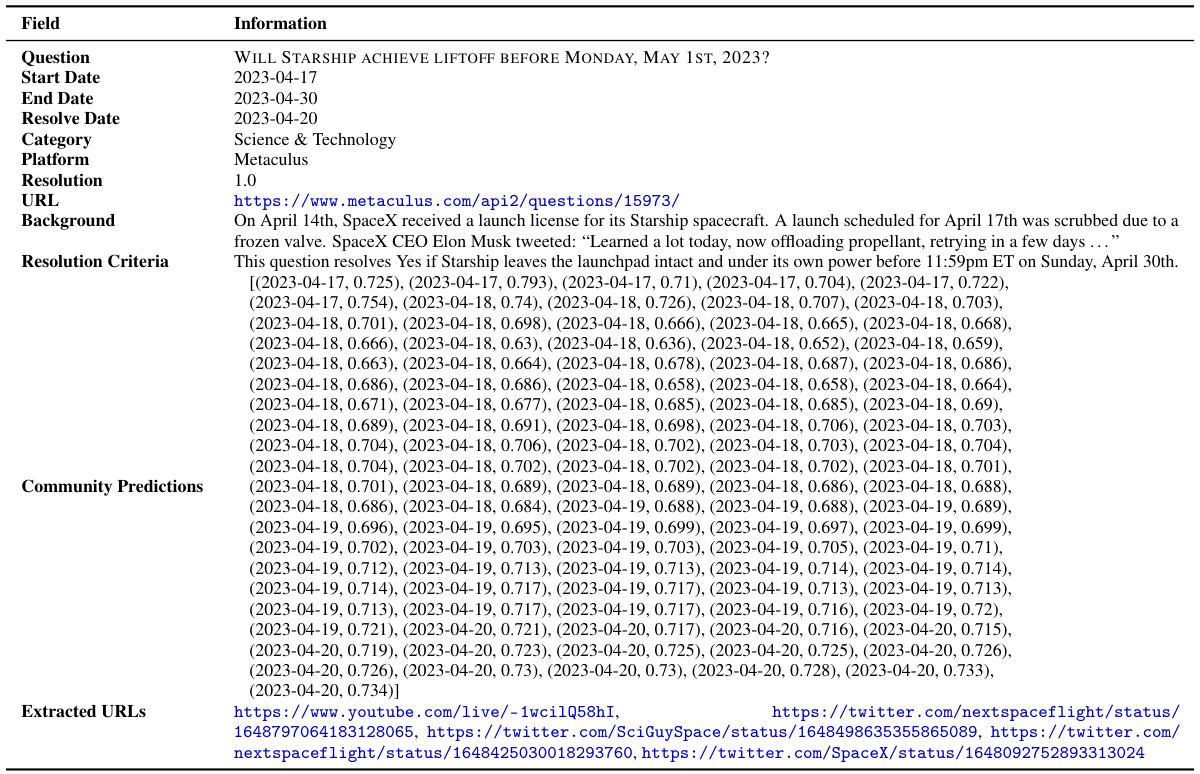

🔼 This table shows the number of questions and predictions from five different forecasting platforms. It breaks down the data into all questions and predictions, and then specifically for binary questions and predictions. The Brier score, a metric for evaluating probabilistic forecasts, is provided for the binary predictions. It reflects the overall size and characteristics of the dataset used for training and evaluating the forecasting model.

read the caption

Table 11: Raw dataset statistics across platforms. The Brier scores are calculated by averaging over all time points where the platforms provide crowd aggregates.

🔼 This table presents the performance of the proposed forecasting system on a test set of questions, comparing its Brier score and accuracy to the crowd aggregate. It further breaks down the results based on different criteria to show performance under various conditions such as when crowd predictions are uncertain, when early retrieval data is used, when many relevant articles are available, and when all three of these conditions hold. The table highlights situations where the system either matches or outperforms the crowd. Statistical significance is also shown through standard error values.

read the caption

Table 3: System performance on the test set. 'All Questions': Brier score on full test set. Other rows: selective evaluation when criteria are met. 'Crowd Uncertain': crowd predictions 0.3-0.7. 'Early Retrieval': first 3 retrieval dates. “5+ Articles”: ≥5 relevant articles. “All Criteria”: all 3 criteria met. System-crowd aggregate performs best in all settings. Subscripts: 1 standard error. Bold: outperforms crowd aggregate. Underlined: best in category.

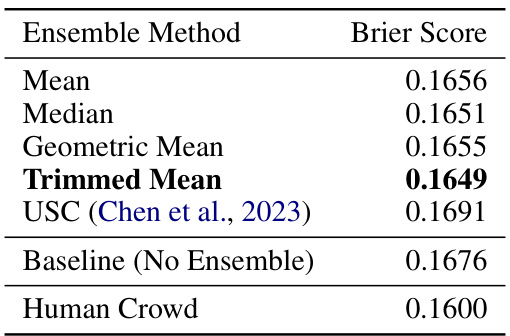

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different ensemble methods used to combine multiple forecasts generated by the system on a validation set. The Brier score, a metric measuring the accuracy of probabilistic forecasts, is used to evaluate the effectiveness of each method. A lower Brier score indicates better performance. The table also includes the baseline Brier score obtained from individual forecasts (without ensembling) and the Brier score achieved by the human crowd, which serves as a benchmark for the system’s performance.

read the caption

Table 13: Brier scores across different ensembling methods on the validation set. “Baseline” refers to the average Brier score of the base predictions (i.e., the inputs to ensembling).

🔼 This table presents the performance of the proposed forecasting system on a test set of questions, comparing it against human forecasters’ aggregate performance (crowd). It shows Brier scores and accuracy, broken down into several scenarios based on different conditions (crowd uncertainty, early retrieval dates, number of relevant articles retrieved, and a combination of these conditions). The results highlight the system’s overall performance and its performance under specific circumstances, illustrating its relative strengths and weaknesses compared to human forecasters.

read the caption

Table 3: System performance on the test set. 'All Questions': Brier score on full test set. Other rows: selective evaluation when criteria are met. 'Crowd Uncertain': crowd predictions 0.3-0.7. 'Early Retrieval': first 3 retrieval dates. “5+ Articles”: ≥5 relevant articles. “All Criteria': all 3 criteria met. System-crowd aggregate performs best in all settings. Subscripts: 1 standard error. Bold: outperforms crowd aggregate. Underlined: best in category.

🔼 This table presents the distribution of the training, validation, and test datasets across five forecasting platforms. The dataset was curated to avoid information leakage by only including questions in the test set that were published after the knowledge cutoff date of the models. The second part of the table shows the baseline performance of pre-trained language models on the test set, measured by Brier score and accuracy, with standard errors included. A random baseline and the average performance of the human crowd are also provided for comparison.

read the caption

Table 2: (a) Distribution of our train, validation, and test sets across all 5 forecasting platforms. (b) Baseline performance of pre-trained models on the test set (see full results in Table 6). Subscript numbers denote 1 standard error. Random baseline: 0.25; human crowd: 0.149.

Full paper#