TL;DR#

Current Transformer models struggle with complex reasoning tasks involving multiple steps, such as composing syllogisms or solving problems requiring global reasoning. This limitation, often referred to as a ‘globality barrier’, arises because these models struggle to capture long-range dependencies and correlations within the data. Existing measures of complexity do not fully address this learnability issue.

This paper addresses this issue by introducing the concept of ‘globality degree’, a measure that quantifies how many tokens a model must attend to in order to efficiently learn a task. The researchers demonstrate a ‘globality barrier’ for high-globality tasks. To overcome this barrier, they propose novel ‘scratchpad’ techniques. These techniques involve providing the model with intermediate reasoning steps or an ‘inductive scratchpad’ allowing more efficient composition of prior information. The authors demonstrate that these improved scratchpad techniques can effectively break through the globality barrier, significantly enhancing both in-distribution and out-of-distribution performance, particularly for tasks that admit an inductive decomposition.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for AI researchers working on Transformers and reasoning. It introduces a novel measure (globality degree) to quantify the difficulty of learning complex tasks and demonstrates limitations of standard Transformers. Furthermore, it proposes innovative scratchpad methods to enhance reasoning capabilities, opening new avenues for future research. The findings challenge existing assumptions about Transformers’ capabilities and are highly relevant to ongoing research in efficient reasoning and generalization.

Visual Insights#

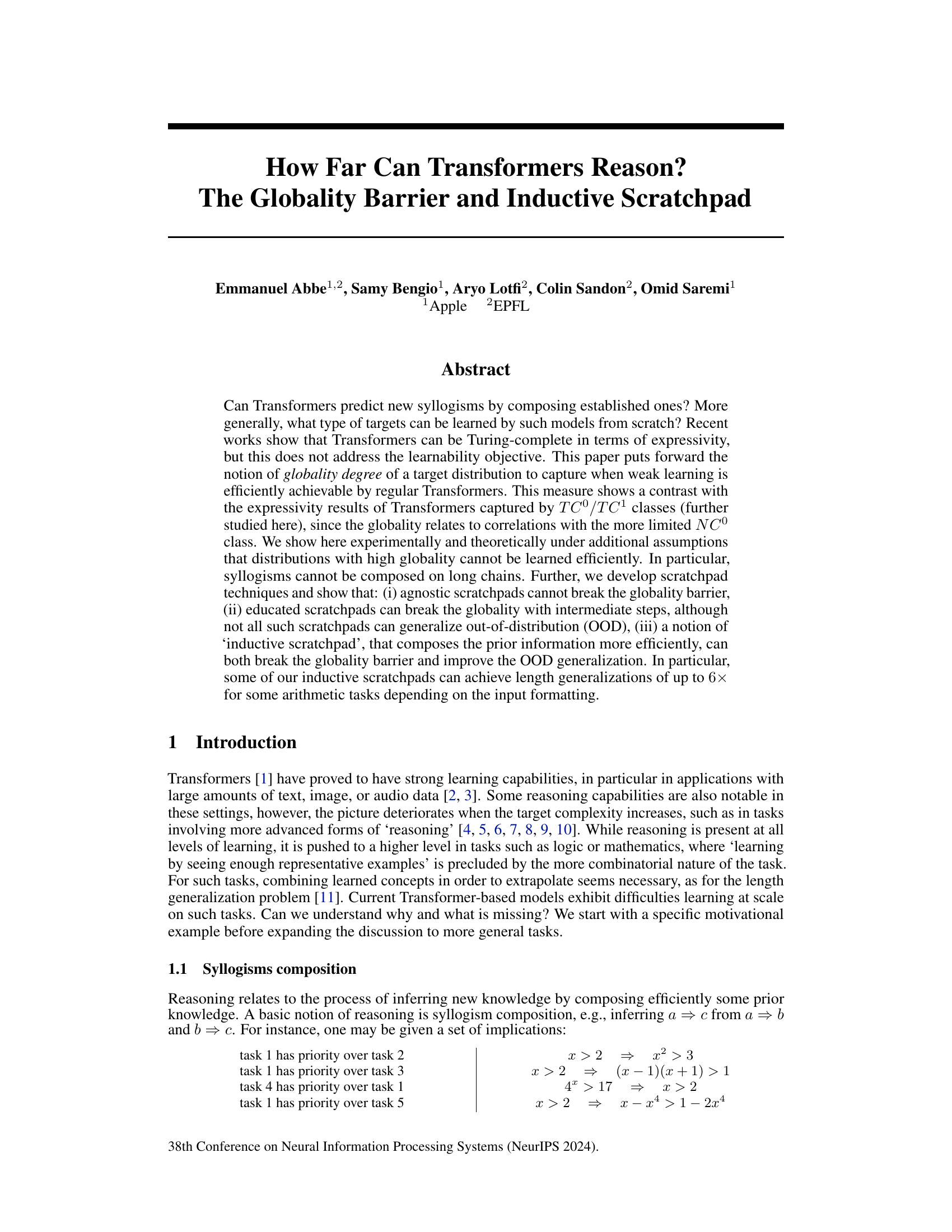

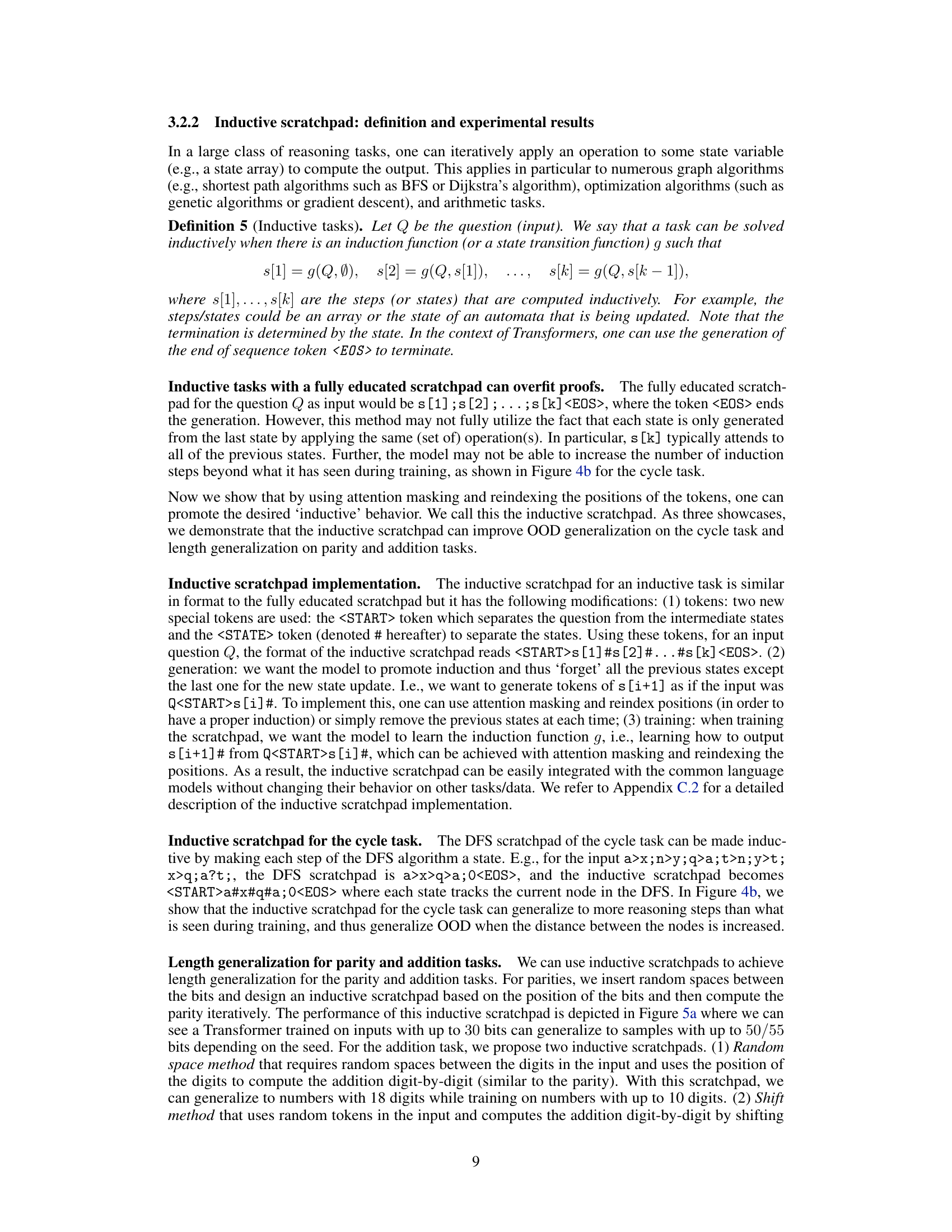

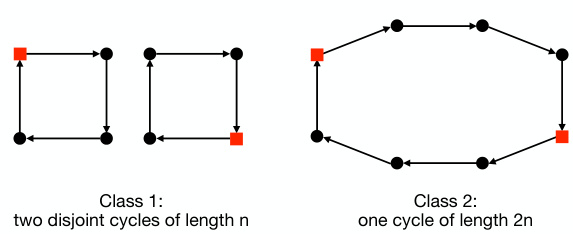

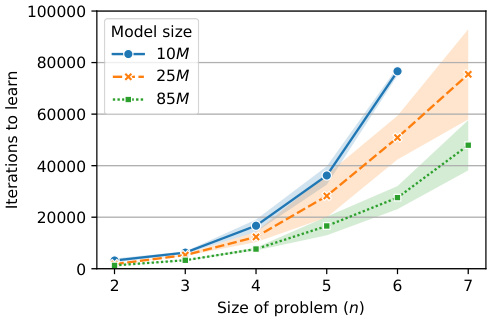

🔼 This figure illustrates the Cycle task used in the paper for evaluating the reasoning capabilities of Transformers. The left panel shows two example graphs used in the binary classification task. Class 1 represents two disjoint cycles of length n, while Class 2 represents a single cycle of length 2n. The red squares highlight the pair of vertices whose connectivity is being predicted. The right panel shows the experimental results, illustrating the number of iterations required to achieve 95% accuracy in training GPT-2 style models with varying parameter sizes (10M, 25M, and 85M) as a function of the problem size (n). This demonstrates the exponential increase in learning difficulty as the problem size grows.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the cycle task for n = 4 (left) and the complexity to learn it (right).

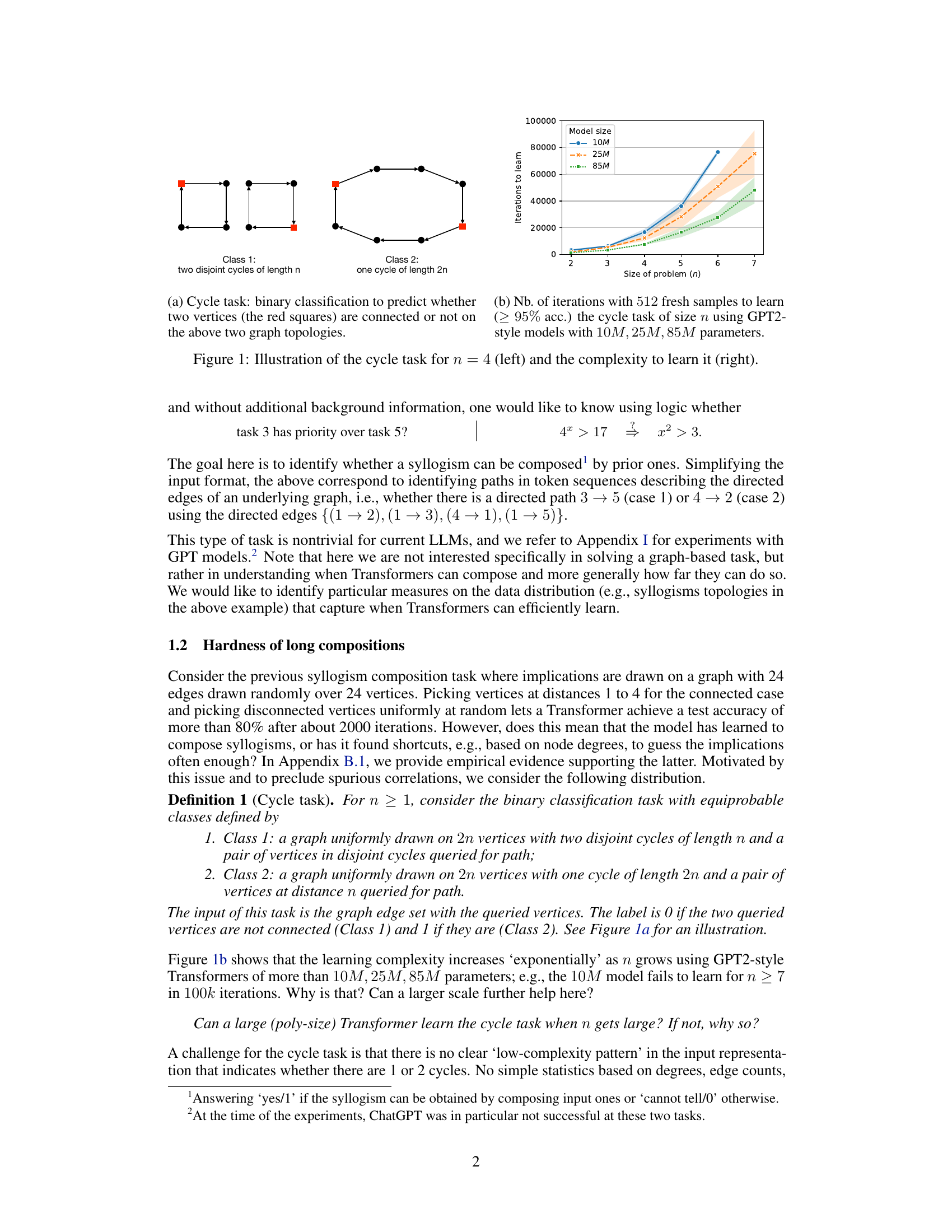

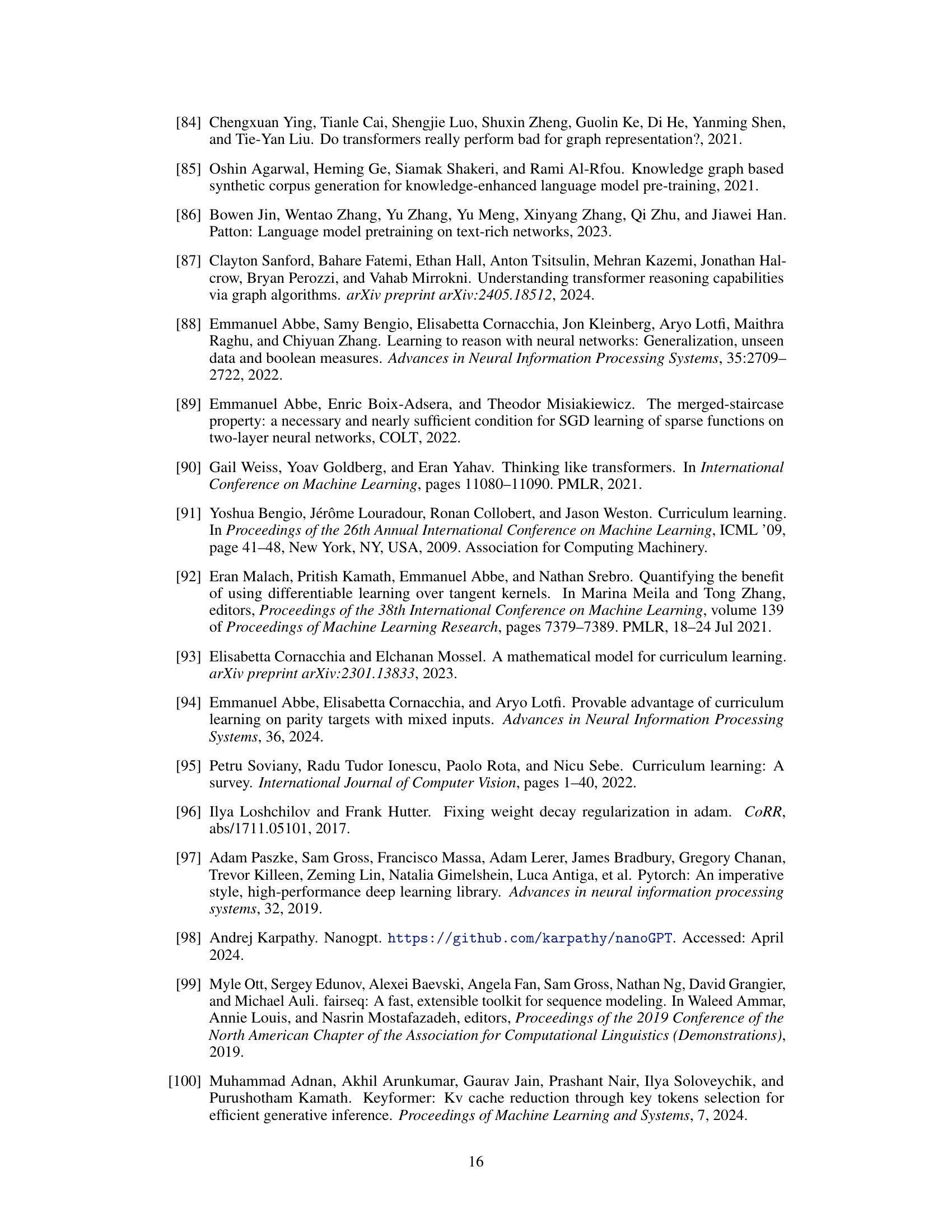

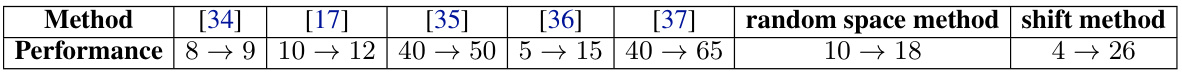

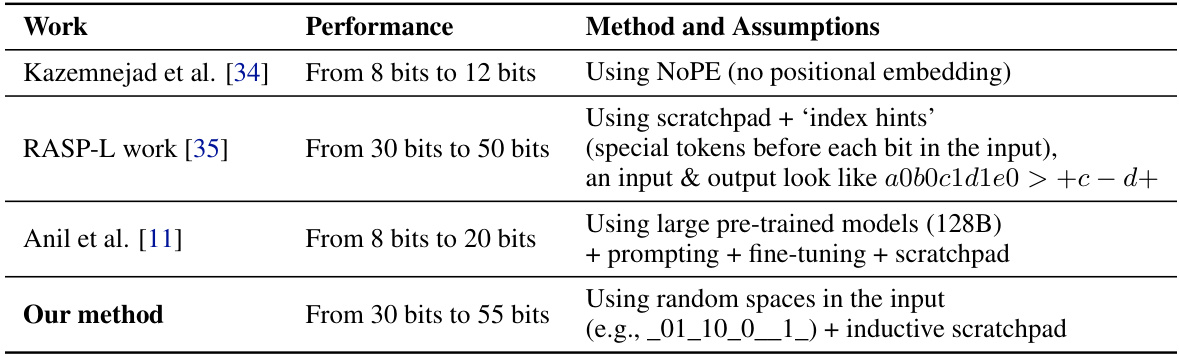

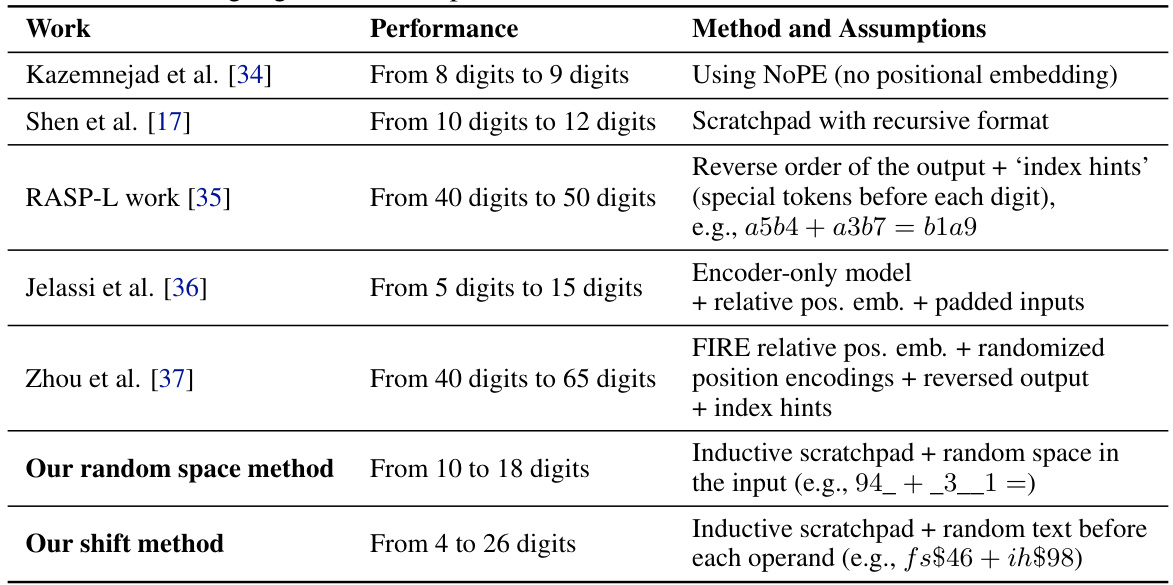

🔼 This table compares the length generalization performance of various methods for the addition task. The ‘Performance’ column shows how many digits the models can generalize to (b) after training on a certain number of digits (a). The methods compared include those from several other research papers, with the authors’ methods highlighted in bold.

read the caption

Table 1: Length generalization of different methods for the addition task where our methods are shown in bold. a → b means generalizing to b digits when trained on a digits.

In-depth insights#

Globality Barrier#

The concept of “Globality Barrier” introduced in the research paper centers on the limitations of standard Transformers when dealing with tasks requiring global reasoning. The authors posit that Transformers struggle with tasks where the solution necessitates considering the entire input simultaneously, rather than focusing on local patterns. Globality degree, a proposed metric, quantifies this difficulty by measuring the minimum number of tokens required to achieve non-trivial correlation with the target, highlighting the contrast between the model’s expressivity and its learning capacity. The paper suggests that high globality tasks—those requiring significant global analysis—form a barrier to efficient learning by standard Transformers. This limitation is not about expressivity (Transformers can express the solutions), but about learnability from scratch. The authors explore ways to overcome this barrier through techniques like scratchpads and particularly inductive scratchpads, which leverage intermediate steps to decompose complex global tasks into simpler sub-tasks. This highlights that efficient reasoning might not only require sufficient expressivity, but also a carefully structured learning process that manages complexity by breaking down global problems into manageable local steps.

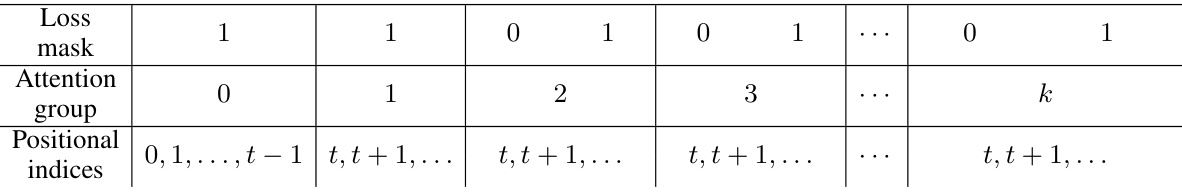

Inductive Scratchpad#

The concept of an ‘Inductive Scratchpad’ presents a novel approach to enhance reasoning capabilities in Transformer models. Unlike traditional scratchpads that provide static intermediate steps, an inductive scratchpad leverages the power of iterative computation by applying an induction function to the previous state. This iterative nature is key to breaking down complex reasoning tasks into manageable sub-tasks, addressing the ‘globality barrier’ that hinders Transformers’ ability to handle long chains of reasoning. The approach is particularly effective in scenarios with a high degree of globality, where the target task necessitates considering a large number of input tokens simultaneously. The inductive scratchpad significantly improves the out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization capabilities of the model by facilitating efficient learning and preventing overfitting. Furthermore, inductive scratchpads demonstrate strong length generalization abilities, successfully extending the capabilities of Transformers to handle significantly longer inputs and more complex operations. This is achieved through the strategic introduction of special tokens that guide the model in the iterative induction process. The empirical results for arithmetic tasks and parity checks reveal substantial improvements in performance by reducing the complexity of the reasoning process and fostering better generalization capabilities.

Transformer Limits#

The heading ‘Transformer Limits’ suggests an exploration of the inherent boundaries of transformer models. A thoughtful analysis would likely cover limitations in long-range dependencies, where transformers struggle to capture relationships between distant tokens in a sequence. Another key aspect would be generalization ability, specifically, the difficulty transformers face in extrapolating knowledge to unseen data or adapting to different task formats. The study may also examine computational costs, as the quadratic complexity of self-attention makes scaling transformers to very long sequences or large datasets prohibitively expensive. Furthermore, the research may investigate limitations in reasoning capabilities, particularly complex reasoning tasks requiring multiple steps of inference or the integration of diverse knowledge sources. Finally, it’s plausible the analysis delves into data efficiency, noting the substantial amounts of data typically required to train high-performing transformers, which contrasts with human learning’s ability to generalize effectively from limited examples. Bias and fairness related to the training data are other concerns that might be discussed.

Scratchpad Methods#

The concept of ‘scratchpad methods’ in the context of large language models (LLMs) centers on augmenting the model’s architecture with external memory to enhance reasoning capabilities. These methods essentially provide LLMs with a working memory, allowing them to store and manipulate intermediate steps during complex reasoning tasks. This addresses the limitation of standard LLMs, which rely on limited internal memory and often struggle with tasks requiring multiple reasoning steps or longer-range dependencies. Different scratchpad approaches exist, ranging from agnostic scratchpads (providing additional memory without supervision) to educated or inductive scratchpads (incorporating prior knowledge or learning intermediate representations). The choice of scratchpad method influences the model’s ability to generalize to out-of-distribution (OOD) examples. While agnostic approaches may fail to break the “globality barrier” for complex tasks, educated scratchpads—particularly inductive ones which promote efficient composition of prior information—show promise for improving OOD generalization and achieving significant length generalization in tasks like arithmetic and parity problems. The key is to structure the scratchpad in a way that facilitates efficient reasoning, avoiding overfitting on the training data. Ultimately, scratchpad methods provide a valuable technique for bridging the gap between LLMs’ impressive abilities in certain tasks and their struggles with complex, multi-step reasoning.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this work could explore more sophisticated globality measures, potentially incorporating notions of ‘globality leap’ to capture stronger learning requirements beyond weak learning. Investigating the role of curriculum learning and its interaction with globality is crucial. Furthermore, the impact of architectural innovations, such as relative positional embeddings, on breaking the globality barrier warrants investigation. A deeper analysis of how inductive scratchpads and other methods can lead to improved out-of-distribution generalization should be undertaken. Finally, research should focus on identifying specific classes of reasoning tasks where inductive decomposition is effective, extending the applicability and practical impact of these findings. The development of scalable methods for designing efficient inductive scratchpads represents a significant challenge. Exploring pre-trained models and automated learning of general scratchpads, utilizing the measures defined in this paper, is a promising avenue for future work.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure consists of two subfigures. The left subfigure illustrates the cycle task for n=4, which is a binary classification problem to predict whether two given vertices are connected in a graph. The graph can be one of two types: two disjoint cycles of length n or one cycle of length 2n. The red squares in the illustration represent the two queried vertices. The right subfigure shows the number of iterations required by GPT2-style models with different sizes (10M, 25M, and 85M parameters) to achieve at least 95% accuracy on the cycle task as the problem size (n) increases. This illustrates the difficulty of learning this task efficiently as the size increases; the learning complexity increases exponentially with n.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the cycle task for n = 4 (left) and the complexity to learn it (right).

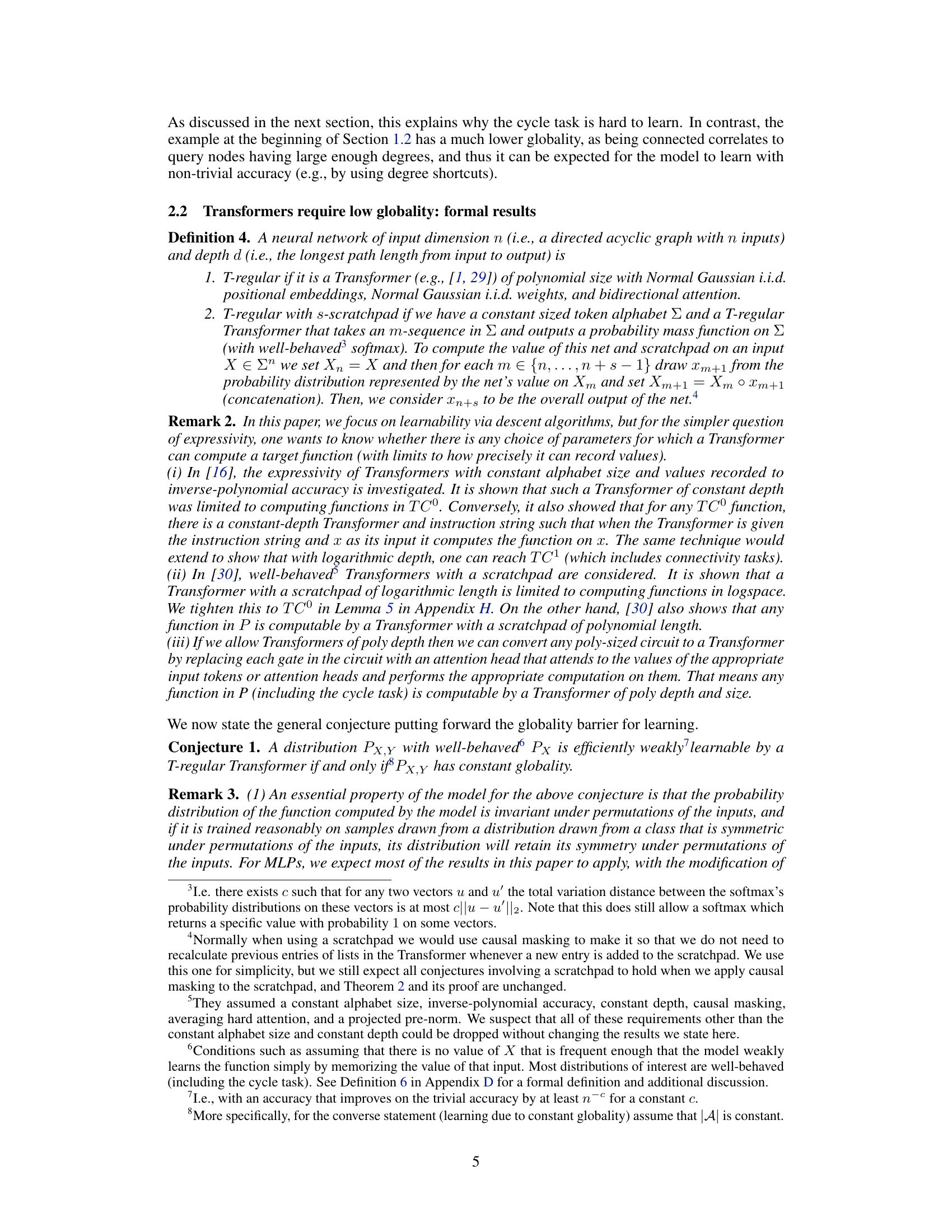

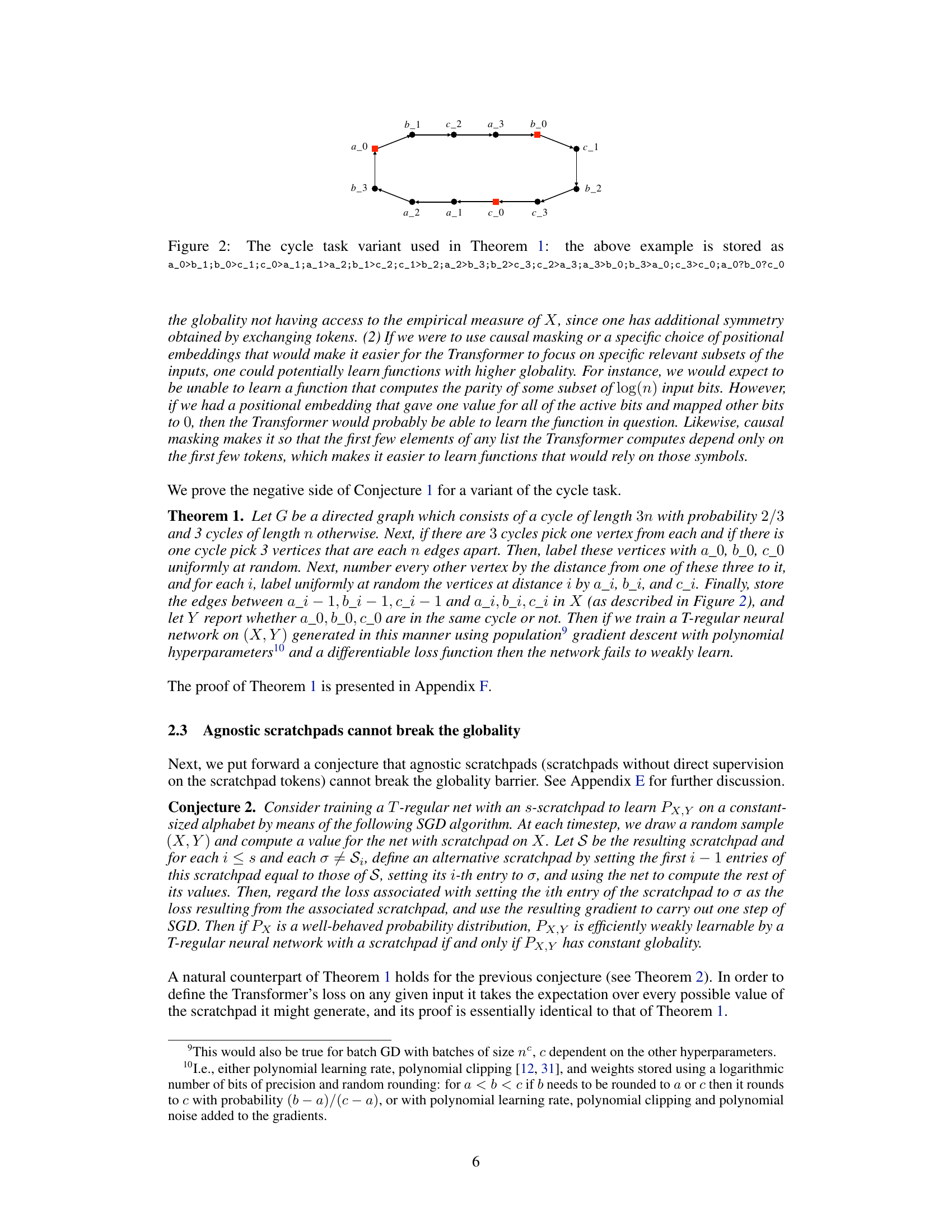

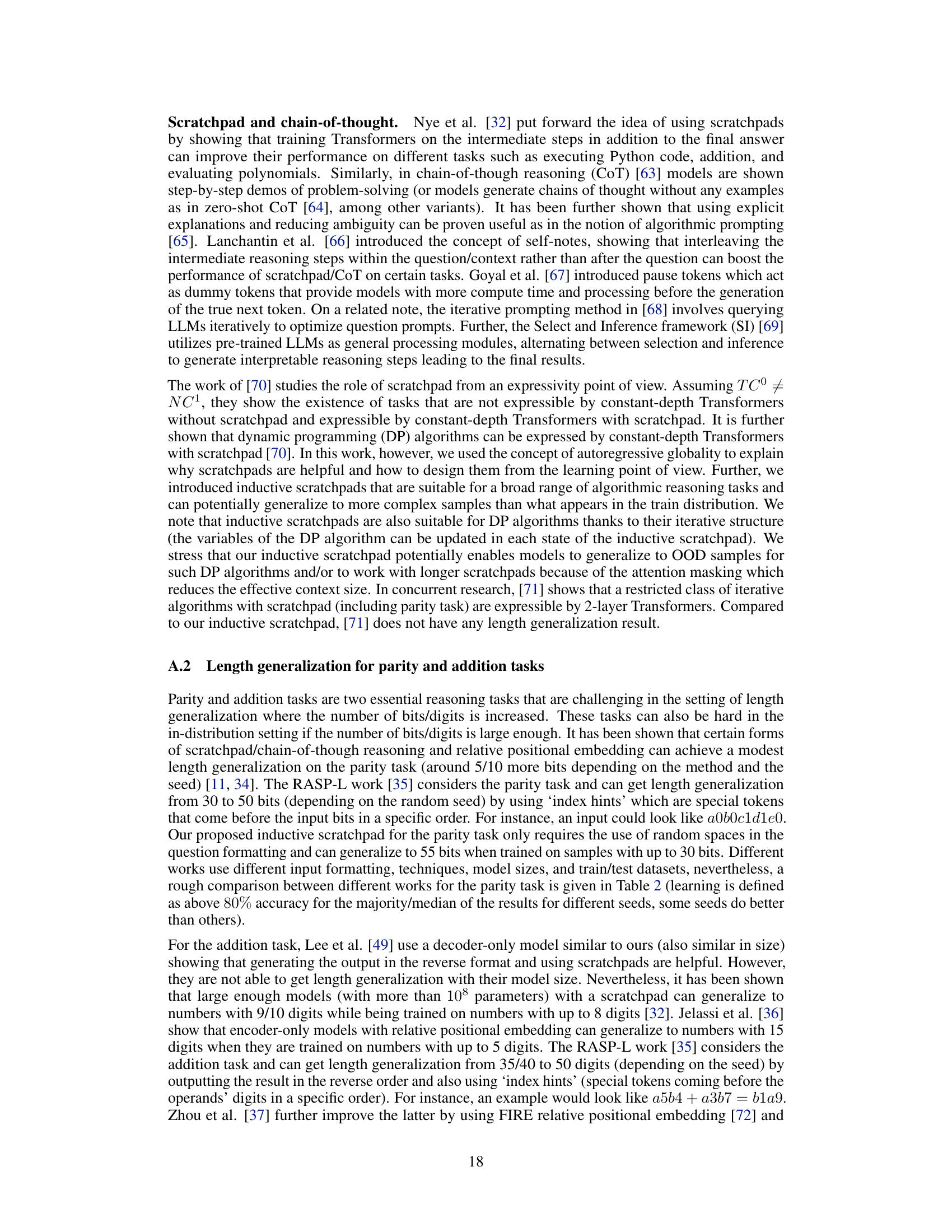

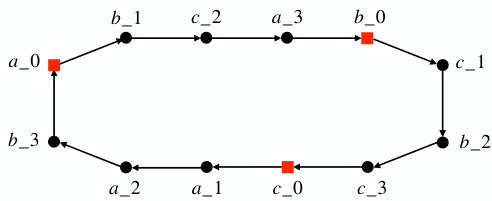

🔼 This figure depicts a variant of the cycle task used to prove Theorem 1 in the paper. The graph consists of a cycle of length 3n with probability 2/3 and 3 cycles of length n otherwise. Vertices are labeled a_i, b_i, c_i according to their distance from a set of three starting vertices (a_0, b_0, c_0), which are chosen randomly from the cycle. The task is to determine whether a_0, b_0, and c_0 are in the same cycle or not, requiring the model to analyze the global structure of the graph.

read the caption

Figure 2: The cycle task variant used in Theorem 1: the above example is stored as a_0>b_1;b_0>c_1;c_0>a_1;a_1>a_2;b_1>c_2;c_1>b_2;a_2>b_3;b_2>c_3;c_2>a_3;a_3>b_0;b_3>a_0;c_3>c_0;a_0?b_0?c_0

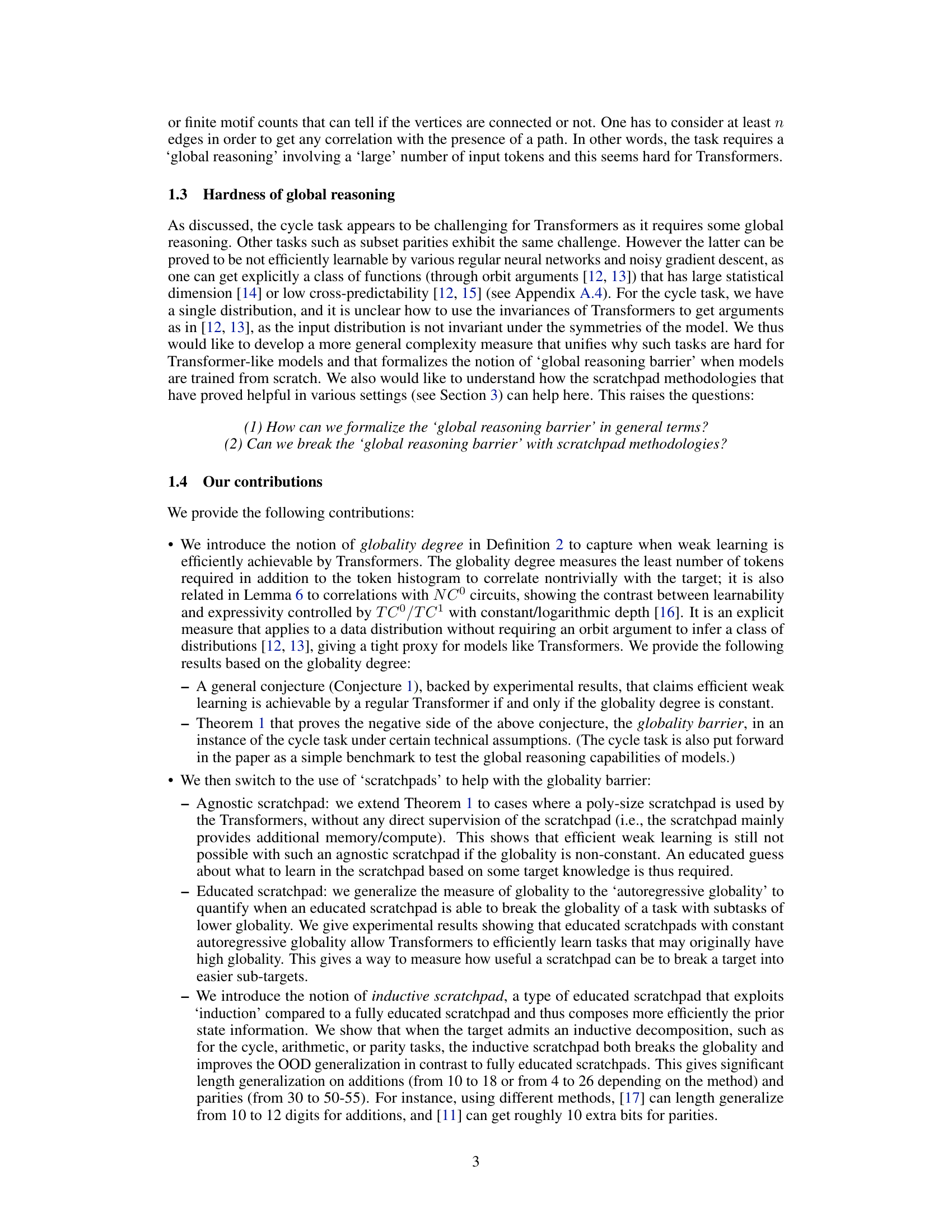

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of educated scratchpads and how they can break the globality barrier in machine learning. The figure shows a sequence of intermediate targets (Y1, Y2, Y3) leading to the final target (Y4). Each step has a low globality, meaning that a small number of input tokens are sufficient to predict the next target in the sequence. By breaking down the complex task into simpler subtasks, the scratchpad helps the model learn more efficiently.

read the caption

Figure 3: An illustration showing how scratchpads can break the globality. The target may be efficiently learned if each scratchpad step is of low globality given the previous ones.

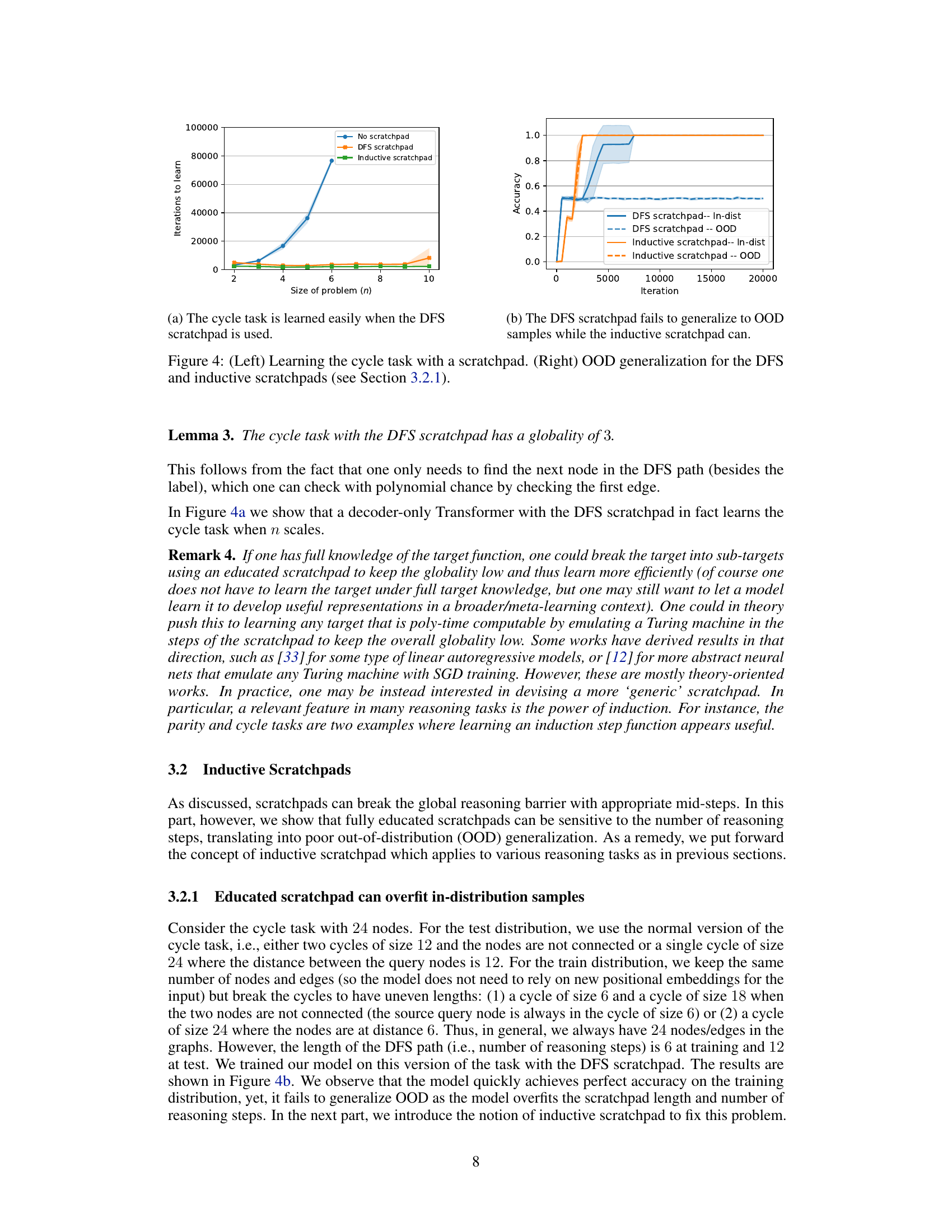

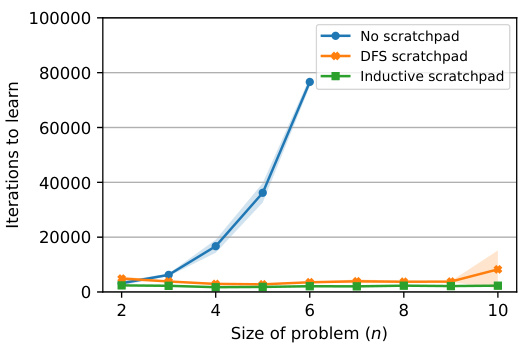

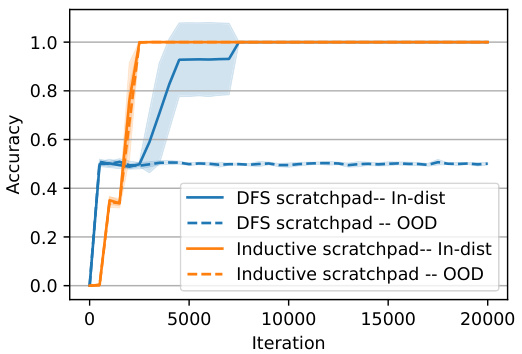

🔼 The left plot shows that using DFS or inductive scratchpad helps the model learn the cycle task easily as the size of the problem scales. The right plot shows that the DFS scratchpad fails to generalize out-of-distribution (OOD) while the inductive scratchpad generalizes to unseen data easily.

read the caption

Figure 4: (Left) Learning the cycle task with a scratchpad. (Right) OOD generalization for the DFS and inductive scratchpads (see Section 3.2.1).

🔼 The figure on the left shows the learning curves for the cycle task with and without the DFS scratchpad. It demonstrates that using the DFS scratchpad significantly improves the learning performance. The figure on the right compares the in-distribution and out-of-distribution generalization performance of the DFS and inductive scratchpads. It highlights that while the DFS scratchpad performs well in-distribution, it fails to generalize out-of-distribution, unlike the inductive scratchpad which maintains good performance in both settings.

read the caption

Figure 4: (Left) Learning the cycle task with a scratchpad. (Right) OOD generalization for the DFS and inductive scratchpads (see Section 3.2.1).

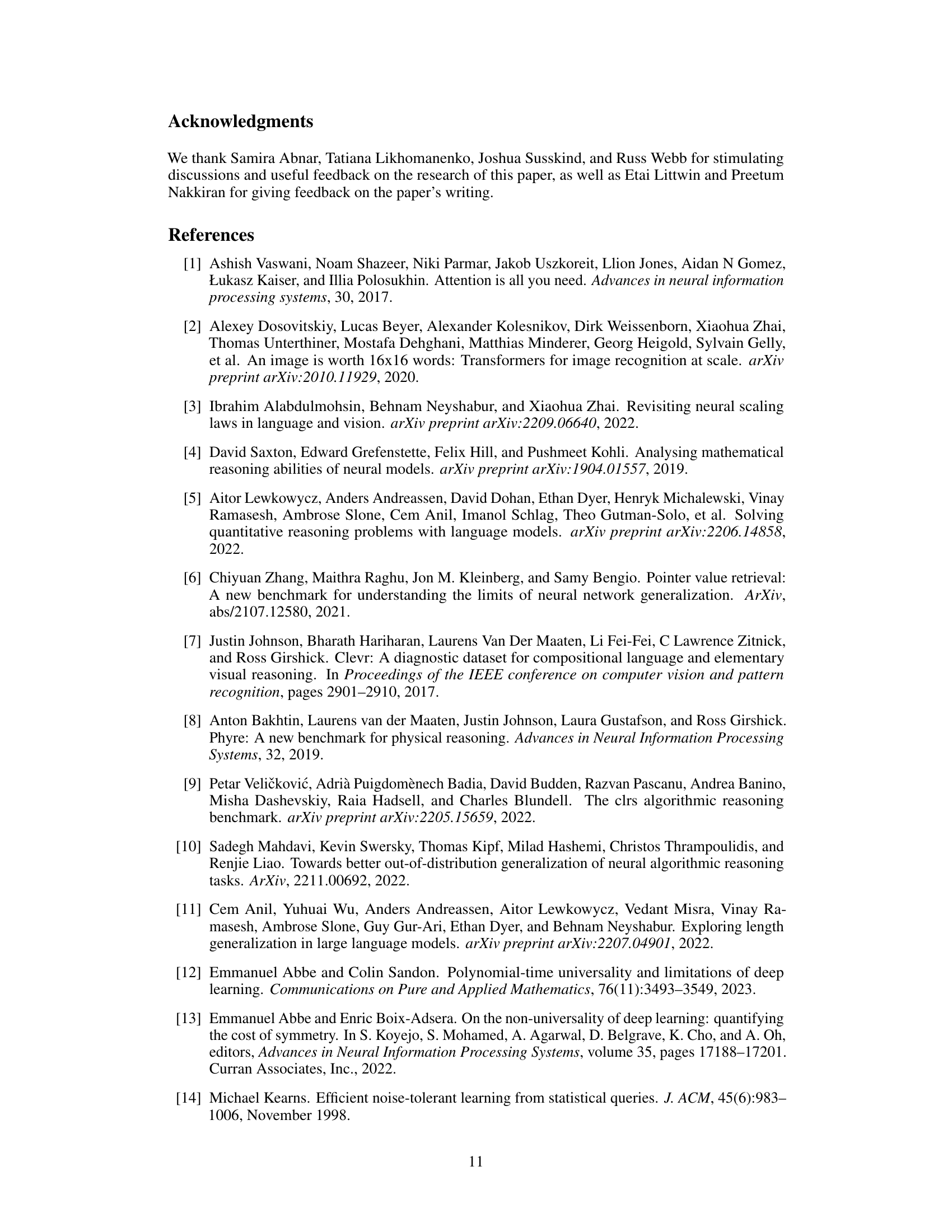

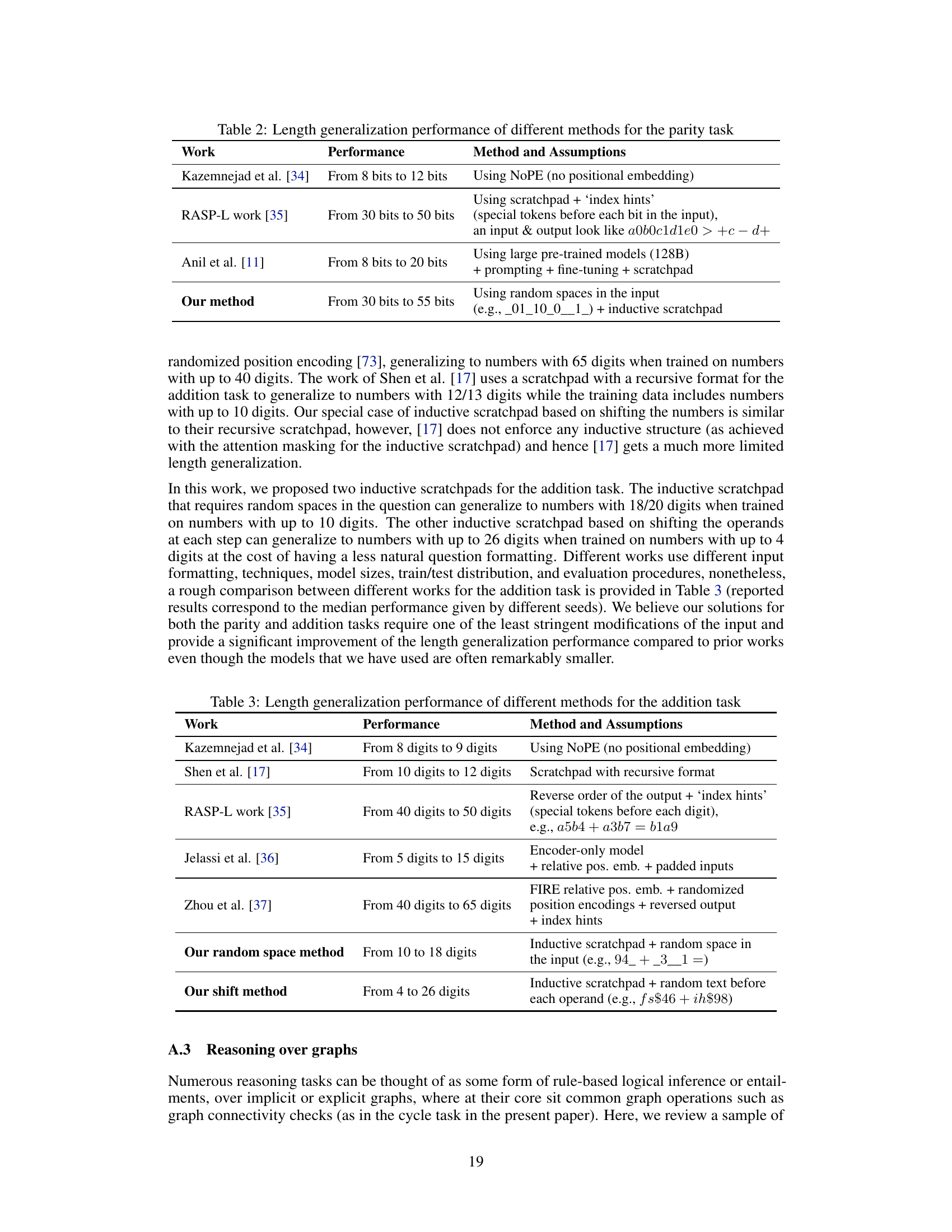

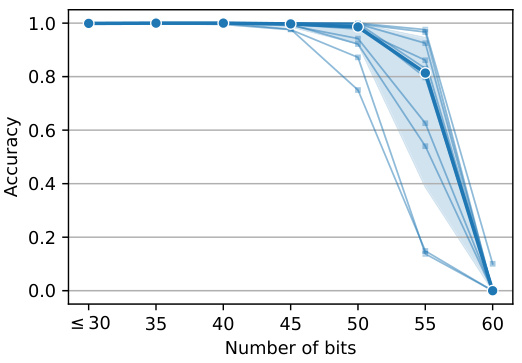

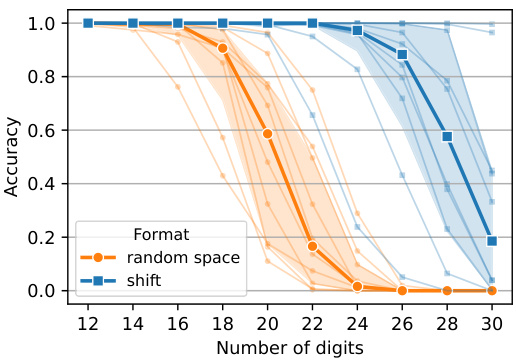

🔼 This figure shows the length generalization results for parity and addition tasks. The left subplot (a) displays the accuracy of the model on parity tasks with varying numbers of bits, demonstrating its ability to generalize to longer sequences than those seen during training (up to 55 bits). The right subplot (b) presents the accuracy for addition tasks, showcasing length generalization capabilities from 4 to 26 digits (using the shift method) and from 10 to 18 digits (using the random space method). The median accuracies are highlighted in bold for each task. The results show the models ability to extrapolate beyond the training data.

read the caption

Figure 5: Length generalization for parity and addition tasks using different random seeds. The medians of the results are highlighted in bold.

🔼 This figure shows the length generalization results for parity and addition tasks using two different inductive scratchpad methods. The x-axis represents the number of bits (for parity) or digits (for addition) in the input, while the y-axis shows the accuracy achieved by the model. Each line represents the results obtained with a different random seed, and the bold line indicates the median across all runs. The figure demonstrates that the inductive scratchpad enables the model to generalize to significantly longer inputs (e.g., up to 55 bits for parity and 26 digits for addition) than those seen during training.

read the caption

Figure 5: Length generalization for parity and addition tasks using different random seeds. The medians of the results are highlighted in bold.

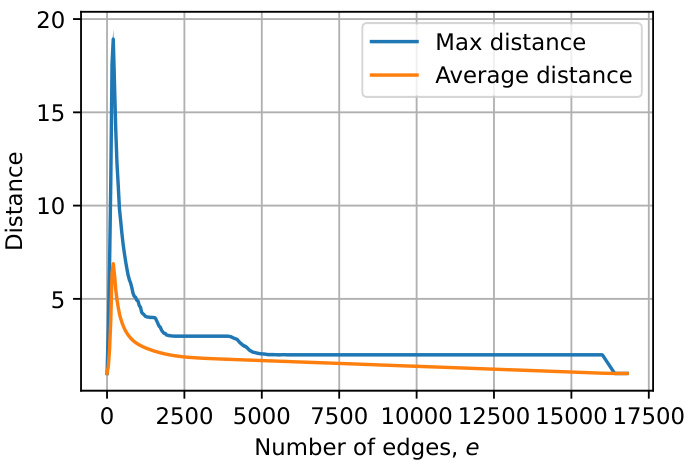

🔼 This figure shows the average maximum distance and average distance between nodes in directed random graphs with 128 nodes. The number of edges varies along the x-axis, while the average distance is plotted on the y-axis. As the number of edges increases, both the average maximum distance and average distance decrease. This illustrates the impact of graph density on connectivity; denser graphs lead to shorter average paths between nodes.

read the caption

Figure 6: The average of the maximum and average distance in directed random graphs with n = 128 nodes and a varying number of edges.

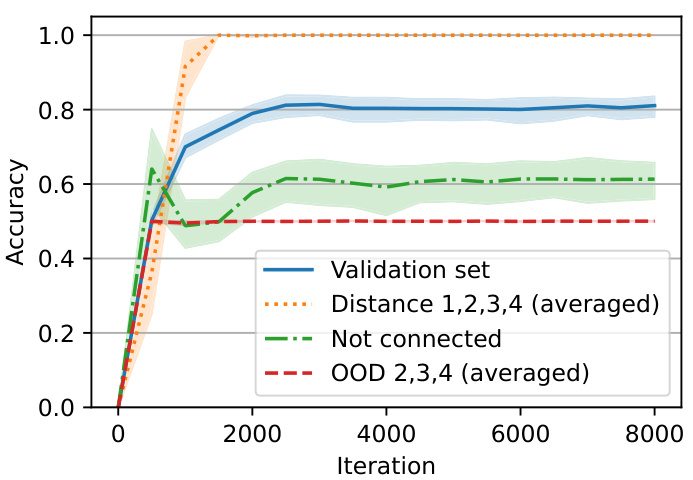

🔼 This figure shows the performance of a model trained on random graphs with 24 nodes and edges. The model achieves high accuracy on the training data, but its performance drops significantly on out-of-distribution (OOD) data where spurious correlations are less present. This suggests that the model is not effectively composing syllogisms, but rather relying on low-level heuristics.

read the caption

Figure 7: Performance of a model trained on a balanced distribution of random graphs with 24 nodes and edges where with probability 0.5 the query nodes are not connected and with probability 0.5 they are connected and their distance is uniformly selected from 1, 2, 3, 4. The validation set has the same distribution as the training set showing that the model reaches around 80% accuracy on in-distribution samples. Particularly, the model has perfect accuracy on connected nodes (distance 1-4) and around 60% accuracy on the nodes that are not connected. However, when we tested the model on OOD samples (where some spurious correlations are not present) the model showed a chance level performance. Note that these samples would be of low complexity if the model was actually checking whether there exists a path or not.

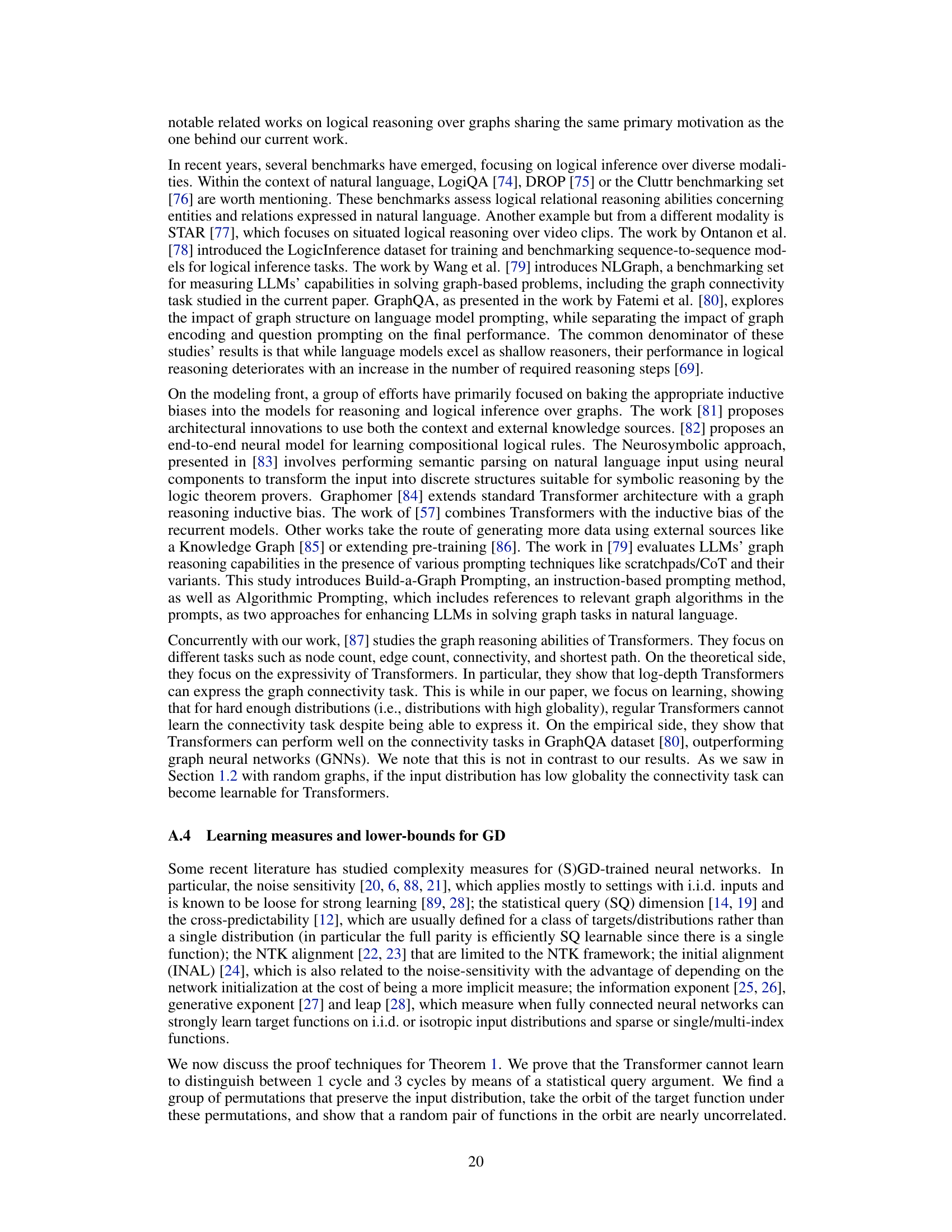

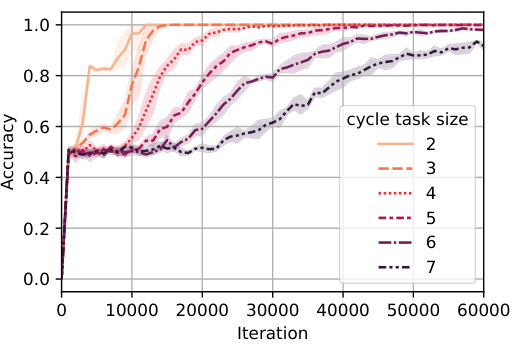

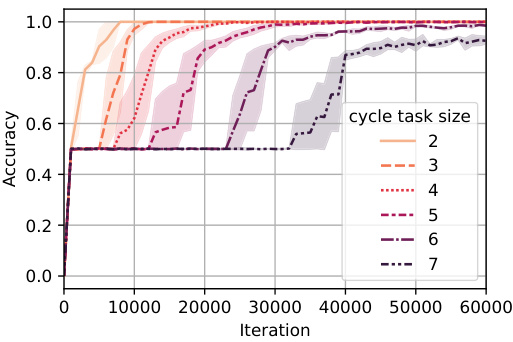

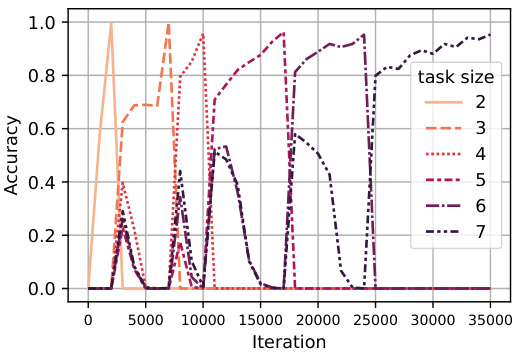

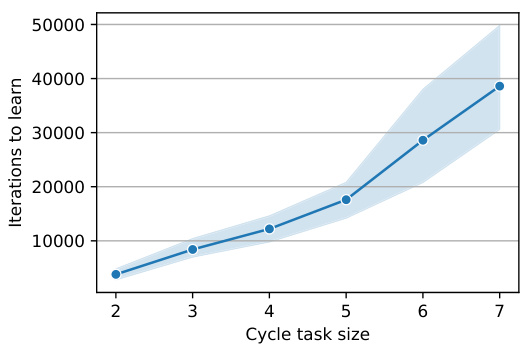

🔼 This figure shows the accuracy curves for training a model on the cycle task with samples of mixed difficulties (left) and curriculum learning (right). The mixed distribution setting involves training on cycle tasks of sizes 2 through 7, each with equal probability. In the curriculum learning setting, the model trains sequentially on tasks of increasing size, starting with the simplest (size 2) and proceeding to the most complex (size 7). The results indicate that both the mixed distribution and curriculum learning approaches reduce the training time compared to training only on the most complex task (size 7).

read the caption

Figure 8: Accuracy for cycle tasks of varying sizes where a mixed distribution (left) and curriculum learning (right) have been used during training. It can be seen that using both a mixed distribution of samples with different difficulties and curriculum learning can reduce the learning time.

🔼 This figure shows the accuracy curves for different sizes of the cycle task (the number of nodes/edges in the graph). The left plot shows the results when the training samples come from a mixture of cycle tasks of different sizes. The right plot shows the results when the training is done using curriculum learning (easier tasks are shown to the model first). The shaded areas represent confidence intervals. Both plots demonstrate that combining mixed difficulty samples and curriculum learning results in faster training convergence.

read the caption

Figure 8: Accuracy for cycle tasks of varying sizes where a mixed distribution (left) and curriculum learning (right) have been used during training. It can be seen that using both a mixed distribution of samples with different difficulties and curriculum learning can reduce the learning time.

🔼 This figure shows the results of two experiments on the cycle task, one using a mixed distribution of training samples and the other using curriculum learning. In both, the model was trained on cycle tasks with varying lengths (n). The left plot shows that a mixed distribution of sample sizes helped the model learn faster. The right plot shows that curriculum learning, where the difficulty gradually increases during training, also resulted in faster learning.

read the caption

Figure 8: Accuracy for cycle tasks of varying sizes where a mixed distribution (left) and curriculum learning (right) have been used during training. It can be seen that using both a mixed distribution of samples with different difficulties and curriculum learning can reduce the learning time.

🔼 The figure shows two plots. The left plot shows the number of iterations needed to learn the cycle task with different sizes (n) using a model with a DFS scratchpad. It demonstrates that using the DFS scratchpad makes learning the cycle task significantly easier. The right plot presents the accuracy of the models with DFS and inductive scratchpads on in-distribution and out-of-distribution (OOD) samples. It shows that the inductive scratchpad generalizes better to OOD samples compared to the DFS scratchpad.

read the caption

Figure 4: (Left) Learning the cycle task with a scratchpad. (Right) OOD generalization for the DFS and inductive scratchpads (see Section 3.2.1).

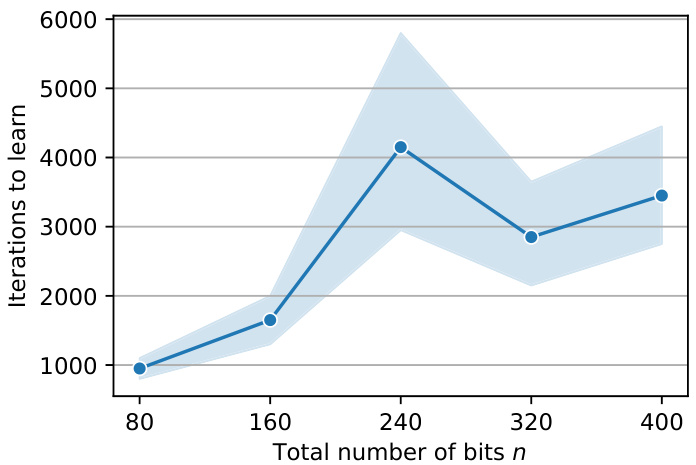

🔼 This figure shows the number of iterations required to learn the half-parity function for different numbers of total bits (n). The half-parity function is defined as the parity of the first n/2 bits. The results demonstrate that using a scratchpad, the model efficiently learns the half-parity function as the number of bits increases. However, there is some variation in the number of iterations due to the randomness introduced by the different random seeds used in the experiments. The shaded area in the plot shows the variability in the results across multiple trials.

read the caption

Figure 10: Learning the half-parity function (learning the parity of the first n/2 bits from the total n bits) for different numbers of bits using a scratchpad. It can be seen that the half-parity targets can be learned efficiently as the number of bits n grows. Note that the random seed of the experiment can cause some variation in the number of iterations required for learning the parity.

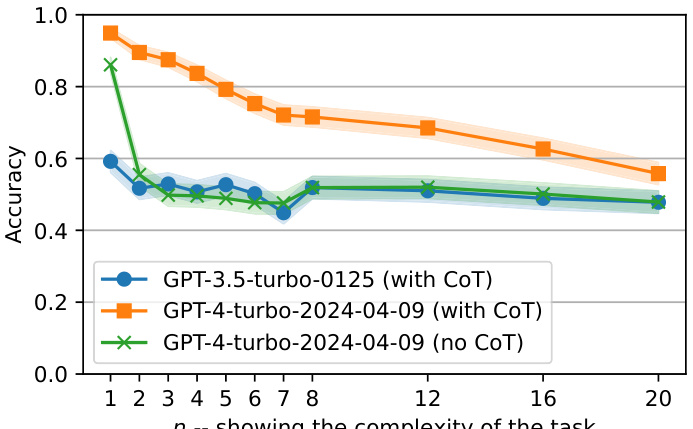

🔼 This figure shows the accuracy of different GPT models (GPT-3.5-turbo-0125, GPT-4-turbo-2024-04-09 with and without chain-of-thought prompting) on a height comparison task. The x-axis represents the complexity of the task (n), and the y-axis represents the accuracy. The results indicate that GPT-4 performs significantly better than GPT-3.5, especially when chain-of-thought reasoning is used. Without chain-of-thought, GPT-4’s performance drops to near random accuracy for n > 1.

read the caption

Figure 11: For complexity n we have 3n + 2 people and there are n people between the two names we query (see example above). We found out that ChatGPT(3.5) can hardly go beyond the random baseline on this task even for n = 1 while GPT4 performs much better. However, if GPT4 does not use CoT reasoning, its performance would be near random for n > 1. Note that we used 1000 examples for each value of n.

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the length generalization performance of several methods for the addition task. It shows how many digits each method can correctly add when trained on a smaller number of digits. The results highlight the improvement achieved by the inductive scratchpad method presented in the paper, showing its superior ability to generalize to longer sequences.

read the caption

Table 1: Length generalization of different methods for the addition task where our methods are shown in bold. a → b means generalizing to b digits when trained on a digits.

🔼 This table compares the length generalization performance of various methods for the addition task. Length generalization refers to a model’s ability to perform addition on numbers with more digits than it was trained on. The table shows the range of digits a model could generalize to after training on a specific number of digits. Our methods (random space and shift methods) are highlighted in bold, showcasing their superior performance compared to prior work.

read the caption

Table 1: Length generalization of different methods for the addition task where our methods are shown in bold. a → b means generalizing to b digits when trained on a digits.

🔼 This table compares the length generalization performance of different methods for the addition task. It shows how many digits each method can accurately predict after being trained on a smaller number of digits. Our methods are highlighted in bold, illustrating superior performance in terms of extrapolating to longer digit sequences.

read the caption

Table 1: Length generalization of different methods for the addition task where our methods are shown in bold. a → b means generalizing to b digits when trained on a digits.

Full paper#