TL;DR#

Vertical Federated Learning (VFL), where multiple parties collaboratively train models without sharing raw data, faces challenges in real-world scenarios. One such challenge is multi-party fuzzy VFL, where parties are linked using imprecise identifiers, leading to performance degradation and increased privacy costs. Existing solutions often address either multi-party or fuzzy aspects, but not both effectively.

The paper introduces Federated Transformer (FeT), a novel framework for multi-party fuzzy VFL. FeT leverages a transformer architecture to encode fuzzy identifiers into data representations, along with three key techniques: positional encoding averaging, dynamic masking, and SplitAvg (a hybrid privacy approach combining encryption and noise). Experiments show that FeT significantly outperforms existing methods, achieving up to 46% accuracy improvement in 50-party settings, while also enhancing privacy.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in federated learning and privacy-preserving machine learning. It addresses the critical challenges of multi-party fuzzy vertical federated learning (VFL), a common scenario in real-world applications involving multiple parties with fuzzily linked data. The proposed Federated Transformer (FeT) offers significant performance improvements and enhanced privacy, opening new avenues for research in more robust and practical VFL methods. The integration of differential privacy techniques and secure multi-party computation further enhances the paper’s significance to the field.

Visual Insights#

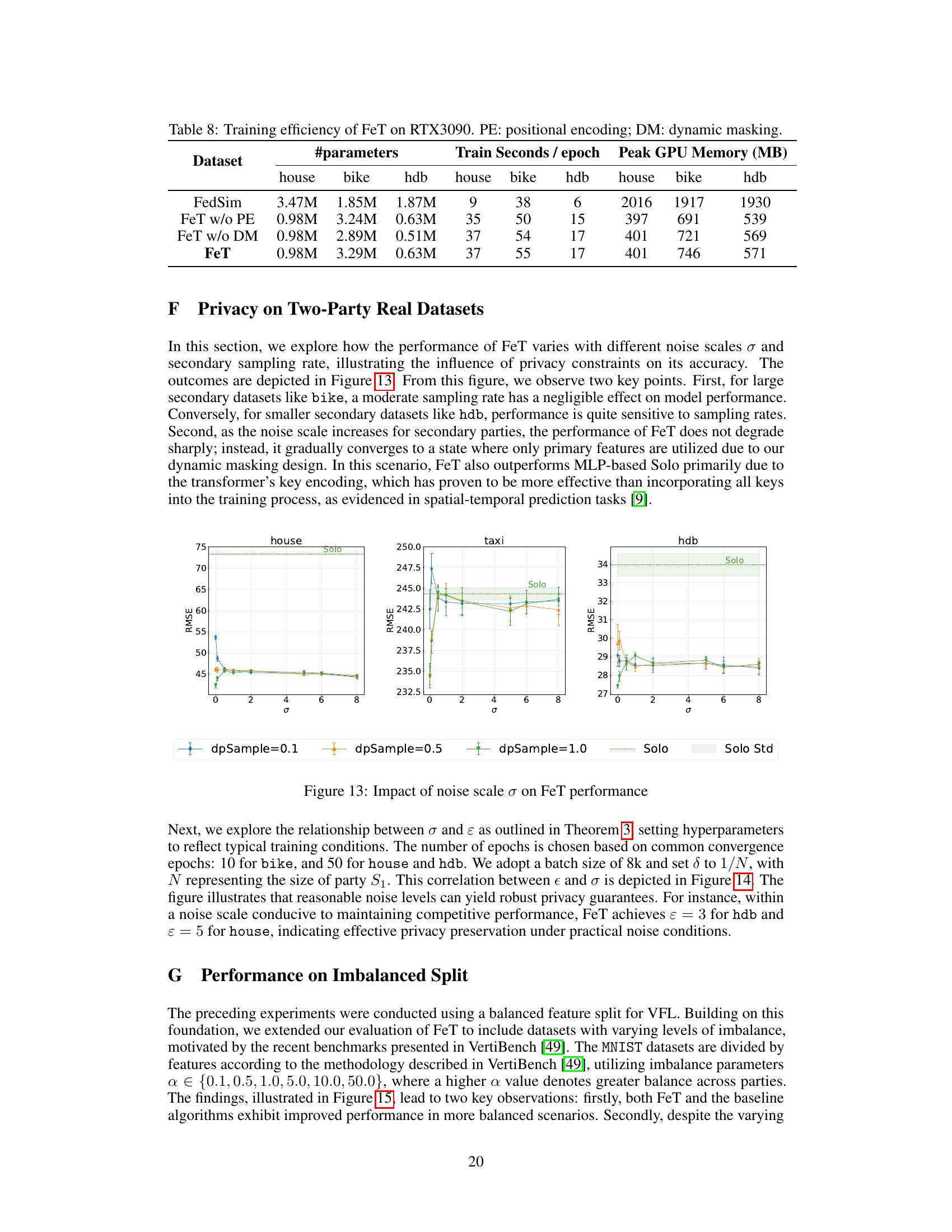

🔼 The figure illustrates a real-world application of multi-party fuzzy Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) for travel cost prediction. Different transportation companies (taxi, bus, car, bike) each possess a unique set of features related to their services (e.g., price, number of passengers, gas cost, availability). However, they share common route identifiers (start and end coordinates, which might be slightly different or fuzzy due to measurement errors or different mapping systems). VFL allows these companies to collaboratively train a model to predict travel costs without directly sharing their private data, leveraging the common, albeit fuzzy, route identifiers to link relevant data.

read the caption

Figure 1: Real application of multi-party fuzzy VFL: travel cost prediction in a city

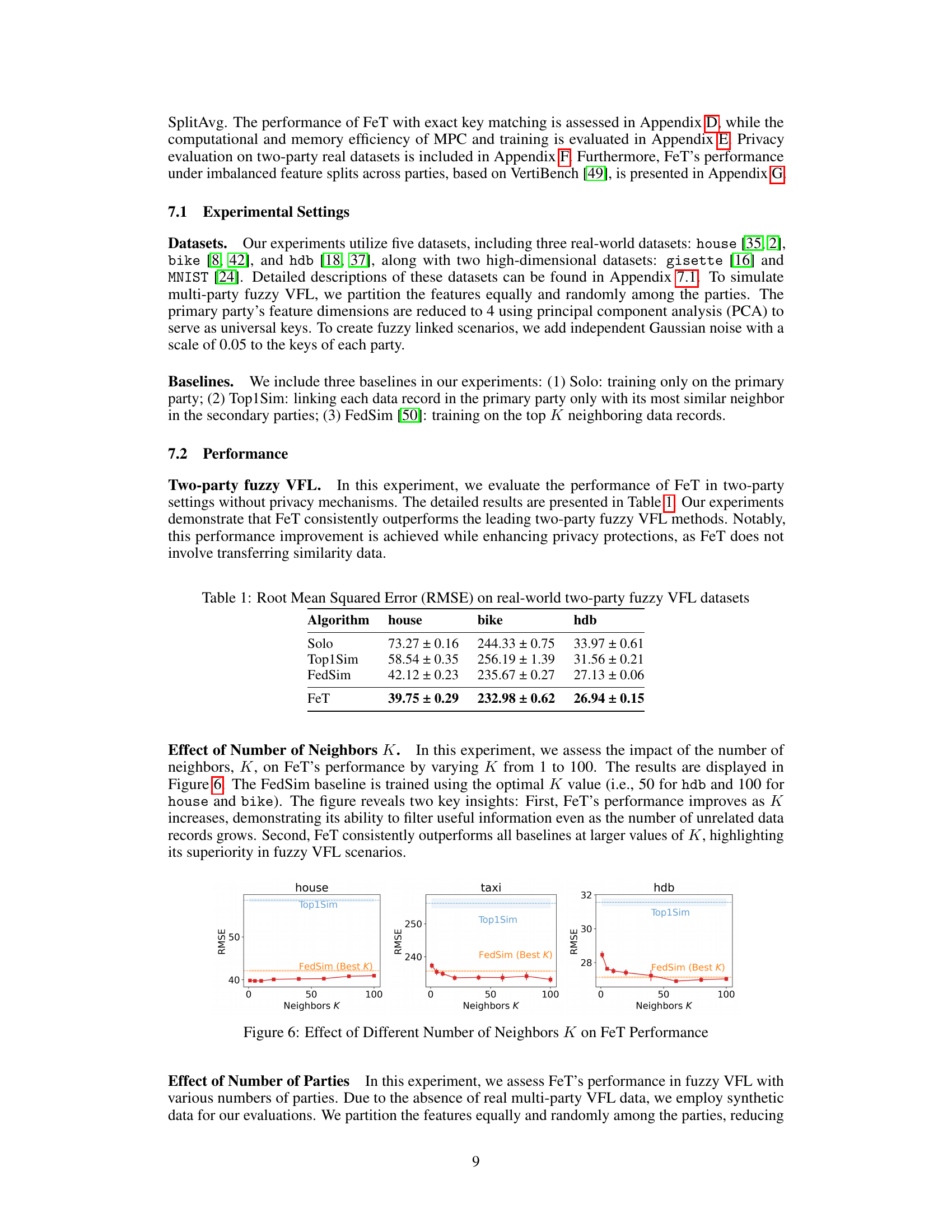

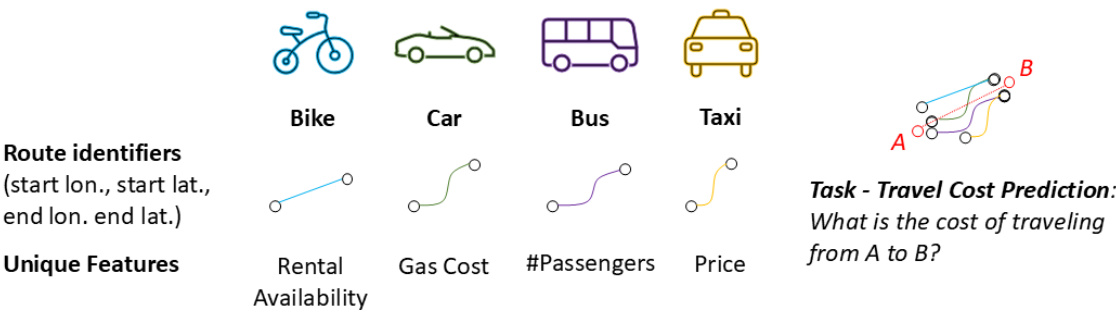

🔼 This table presents the results of the two-party fuzzy VFL experiment without any privacy mechanisms. It compares the performance of FeT against three baselines (Solo, Top1Sim, FedSim) across three real-world datasets (house, bike, hdb) in terms of Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The results show that FeT consistently outperforms other methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) on real-world two-party fuzzy VFL datasets

In-depth insights#

Multi-Party VFL#

Multi-party Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) tackles the challenge of collaborative model training across multiple parties possessing distinct, yet linked, features of the same data instances. Unlike traditional two-party VFL, the multi-party scenario introduces significant complexity. The increased number of parties exponentially increases the difficulty of key matching (linking records across parties), amplifies privacy risks due to potential inference attacks, and escalates computational costs associated with data aggregation and communication. The core problem lies in securely aligning data across multiple sources where identifiers might be imprecise or fuzzy, leading to performance degradation and increased privacy concerns. Effective solutions need to address these challenges by designing scalable and privacy-preserving mechanisms for data linking, aggregation, and model training. This necessitates innovations in secure multi-party computation (MPC), differential privacy techniques, and efficient distributed learning architectures that can handle the inherent complexities of multi-party interaction while minimizing communication overhead and computational resources. Ultimately, resolving these issues within a multi-party VFL framework is crucial for unlocking the full potential of collaborative learning in diverse real-world applications where data privacy and security are paramount.

FeT Architecture#

The Federated Transformer (FeT) architecture is designed for multi-party vertical federated learning (VFL) with fuzzy identifiers. Its core innovation lies in integrating fuzzy identifiers directly into data representations, avoiding the quadratic complexity associated with traditional pairwise comparison methods. This is achieved through a multi-dimensional positional encoding scheme that incorporates key information. The architecture then uses a transformer model, distributed across multiple parties, leveraging three key techniques: dynamic masking to filter out unreliable linkages, SplitAvg for enhancing privacy through a combination of encryption and noise-based methods, and party dropout to mitigate communication bottlenecks and overfitting. The combination of these elements allows FeT to achieve significant performance gains and improved privacy guarantees, especially in large-scale, fuzzy settings. The effectiveness of FeT highlights the potential for transformer-based architectures in addressing the challenges of practical multi-party VFL.

Privacy Framework#

The paper introduces a novel privacy framework crucial for multi-party vertical federated learning (VFL) on fuzzily linked data. It integrates differential privacy (DP) with secure multi-party computation (MPC) to safeguard sensitive information during the training process. This hybrid approach is designed to mitigate the increasing privacy risks associated with more participating parties, addressing a significant limitation of existing methods. A key innovation is SplitAvg, a technique that combines encryption-based and noise-based methods to maintain a balanced level of privacy regardless of the number of parties, reducing communication overhead while preserving the data utility. The framework incorporates theoretical guarantees of differential privacy, providing a rigorous mathematical foundation for its privacy claims. Furthermore, the framework is shown to improve model accuracy and efficiency compared to existing methods, demonstrating its practical viability and effectiveness in real-world scenarios. The emphasis on balancing performance and privacy is particularly noteworthy, as the paper actively addresses the challenge of preserving privacy without sacrificing model accuracy. This is a vital consideration for practical implementations of VFL.

Scalability Limits#

Scalability is a critical concern in multi-party vertical federated learning (VFL), especially when dealing with fuzzily linked data. The challenges increase dramatically as the number of participating parties grows. Increased computational costs associated with secure multi-party computation (MPC) for privacy preservation become a major bottleneck. Communication overhead also explodes quadratically as each party needs to interact with every other party. The number of possible pairings between fuzzy identifiers increases dramatically, leading to a combinatorial explosion of key comparisons and significant performance degradation. Accuracy loss is also likely due to increased model complexity and potential overfitting issues. Data sparsity and inconsistencies due to fuzzy linking can exacerbate these problems, leading to unreliable model training. Effective techniques such as dynamic masking, positional encoding averaging, and party dropout are crucial to mitigate these scalability limits but cannot fully eliminate them. Further research is needed to explore more advanced distributed computing techniques and privacy-preserving mechanisms to enhance scalability in practical multi-party fuzzy VFL scenarios. Efficient data representation and aggregation strategies are essential for future improvements.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from the Federated Transformer (FeT) paper could significantly expand its capabilities and address limitations. Extending FeT to handle more complex real-world scenarios beyond the idealized settings of the current experiments is crucial. This involves exploring settings with more noisy or incomplete data, addressing situations with imbalanced data distributions across parties, and evaluating its robustness in the presence of malicious or Byzantine actors. Improving the efficiency of the SplitAvg privacy mechanism is also key. While SplitAvg offers enhanced privacy, further investigation into reducing its computational overhead and communication complexity is warranted, particularly for large-scale deployments. Theoretical analysis and formal proofs for FeT’s privacy guarantees under more realistic threat models should be developed, going beyond the current differential privacy bounds. Investigating alternative privacy-preserving techniques that might offer better performance or utility trade-offs is important, and exploring the compatibility of FeT with other privacy-enhancing technologies should be considered. Finally, empirical evaluation across a wider range of datasets and tasks is necessary to establish FeT’s generalizability and demonstrate its practical effectiveness beyond the specific applications presented in the paper. These future avenues of investigation would significantly strengthen the applicability and impact of the FeT framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

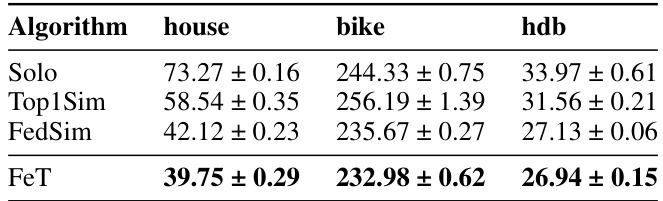

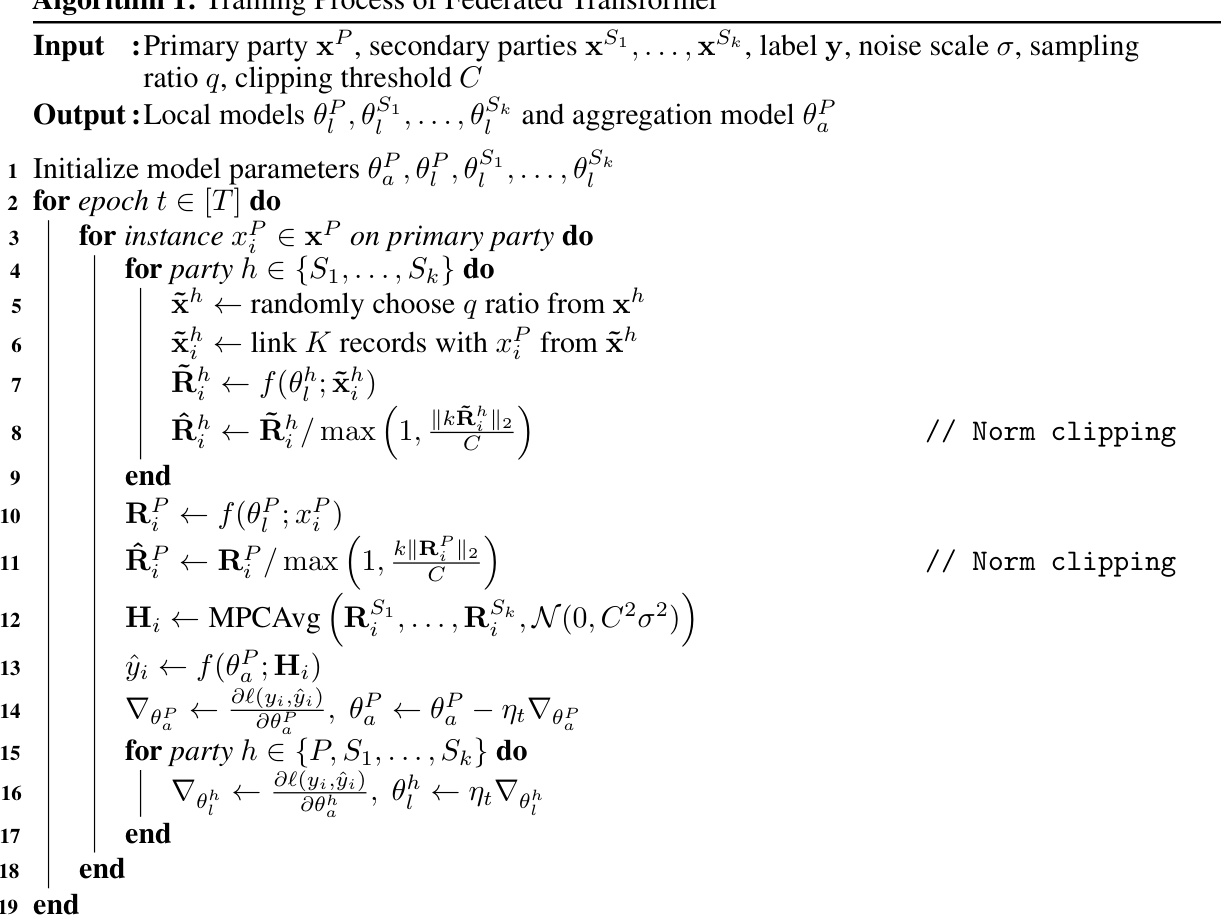

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model, which is a transformer-based architecture designed for multi-party fuzzy VFL. It shows how the model encodes keys into data representations using multi-dimensional positional encoding and employs a dynamic masking module to filter out incorrectly linked data records. The figure also depicts the secure multi-party summation process used during the aggregation of outputs from the encoders at the secondary parties and the usage of the party dropout strategy to improve performance and reduce communication costs.

read the caption

Figure 2: Structure of federated transformer (PE: multi-dimensional positional encoding)

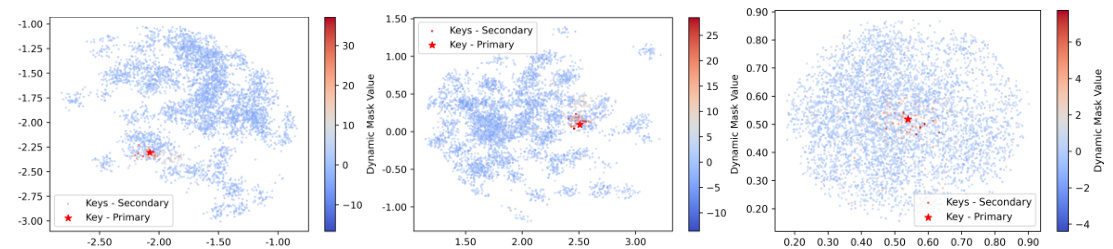

🔼 This figure visualizes the output of the trainable dynamic masking module in the Federated Transformer (FeT) model. Each plot shows a single data point from the primary party (red star) and its 4900 nearest neighbors from 49 secondary parties (blue circles). The x and y axes represent the key identifiers, while the color intensity represents the learned dynamic mask value. Larger, warmer colors indicate stronger attention weights assigned by the model to these data points during training, effectively filtering out less relevant data points with weaker connections.

read the caption

Figure 3: Learned dynamic masks of different samples: Each figure displays one sample (red star) from the primary party fuzzily linked with 4900 samples (circles) from 49 secondary parties. The position indicates the sample’s identifier, and colors reflect learned dynamic mask values. Larger mask values signify higher importance in attention layers.

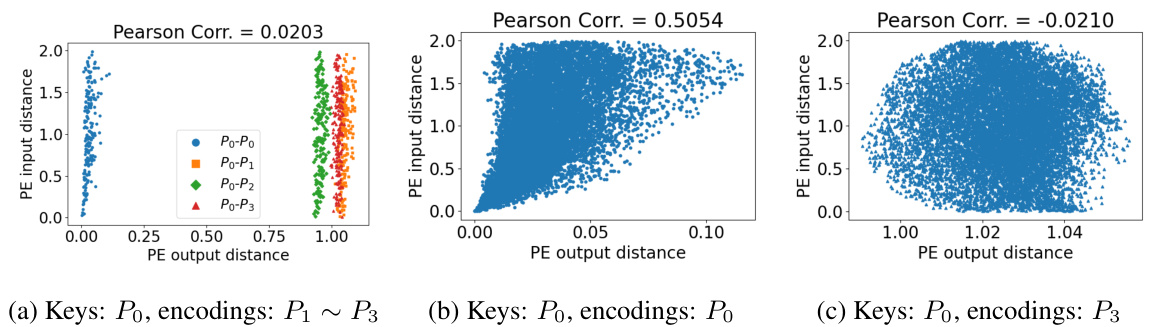

🔼 This figure visualizes the misalignment issue of positional encoding in the Federated Transformer model. It shows scatter plots illustrating the correlation between input and output distances of positional encoding across different parties. Panel (a) displays a low correlation between the primary party’s positional encodings and those of secondary parties (P₁-P₃). Panel (b) shows a high positive correlation between input and output positional encodings within the primary party. Panel (c) shows a negligible correlation between the primary party’s inputs and the encodings of a specific secondary party (P₃). This highlights the problem of positional encoding misalignment across parties which the proposed positional encoding averaging technique aims to solve.

read the caption

Figure 4: Misalignment of positional encoding (P): primary party; P₁ ~ P3: secondary parties)

🔼 This figure shows the architecture of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model. It illustrates how the data flows between the primary party (holding labels) and the secondary parties (without labels) during the training process. The primary party has both an encoder and a decoder, while each secondary party has only an encoder. Key information is integrated into feature vectors using multi-dimensional positional encoding. The outputs from the secondary parties’ encoders are aggregated and fed into the decoder of the primary party. The figure also highlights components like multi-head attention, feed-forward layers, layer normalization, and dynamic masking, which are key elements of the FeT’s design to improve performance and privacy.

read the caption

Figure 2: Structure of federated transformer (PE: multi-dimensional positional encoding)

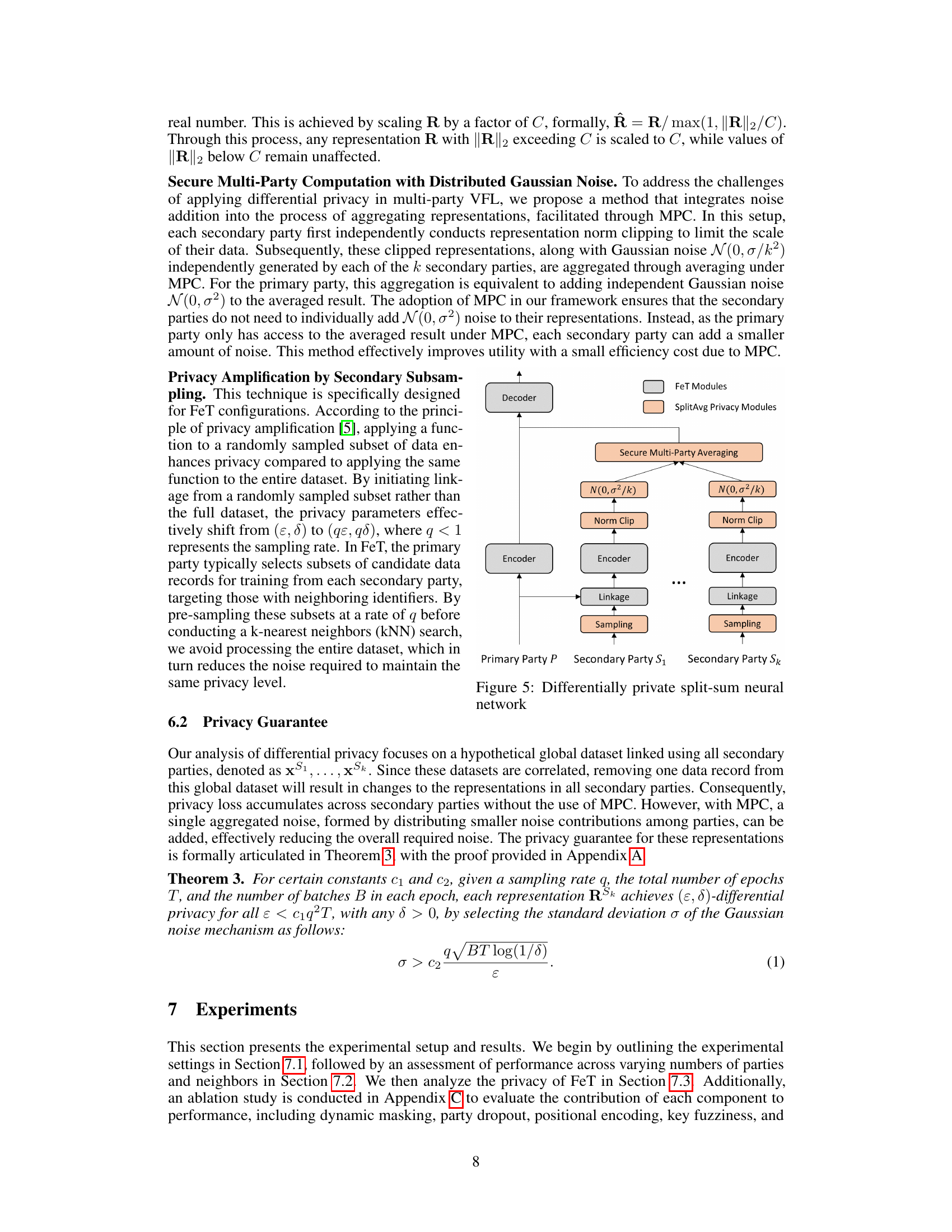

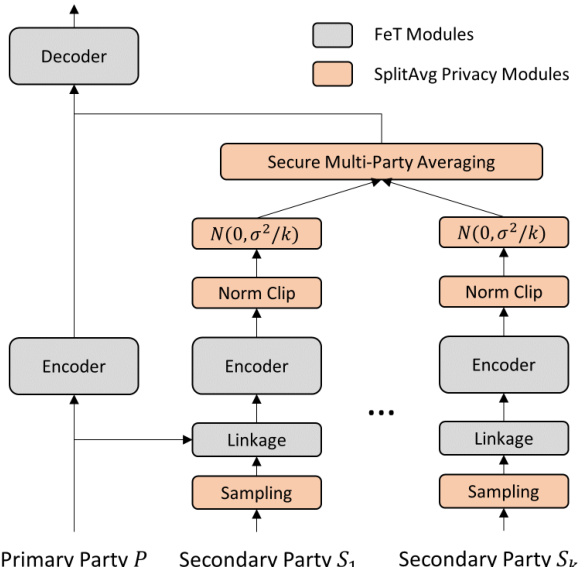

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of SplitAvg, a multi-party privacy-preserving VFL framework that integrates differential privacy (DP), secure multi-party computation (MPC), and norm clipping to enhance the privacy of representations. It shows how the secondary parties’ representations are processed with norm clipping and distributed Gaussian noise before secure multi-party averaging with the primary party. The resulting aggregated data is then used by the decoder in the FeT model.

read the caption

Figure 5: Differentially private split-sum neural network

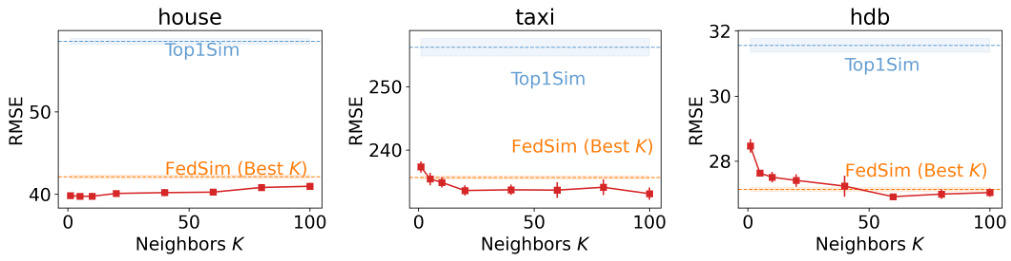

🔼 This figure displays the impact of varying the number of neighbors (K) on the performance of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model. The results are shown across three different real-world datasets (house, bike, and hdb). The performance is measured using Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE). The figure reveals that FeT’s performance generally improves as K increases, but there is a point of diminishing returns. Importantly, FeT consistently outperforms baseline models (Top1Sim and FedSim) at larger K values, highlighting its effectiveness in fuzzy Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 6: Effect of Different Number of Neighbors K on FeT Performance

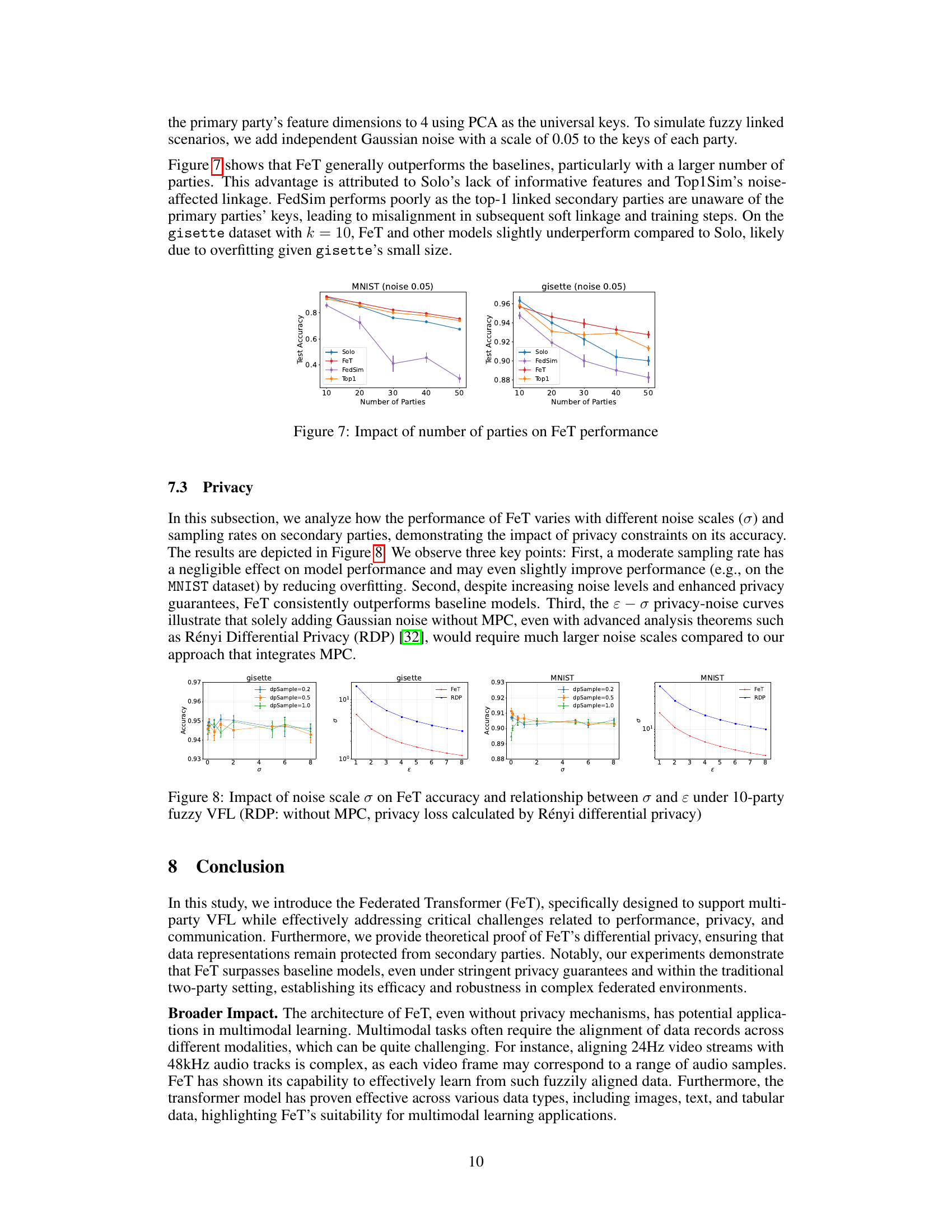

🔼 This figure displays the impact of the number of parties on the performance of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model and its baselines (Solo, FedSim, and Top1Sim) for both MNIST and gisette datasets. It shows how the test accuracy of each model changes as the number of parties increases from 10 to 50. The results illustrate FeT’s superiority in multi-party scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 7: Impact of number of parties on FeT performance

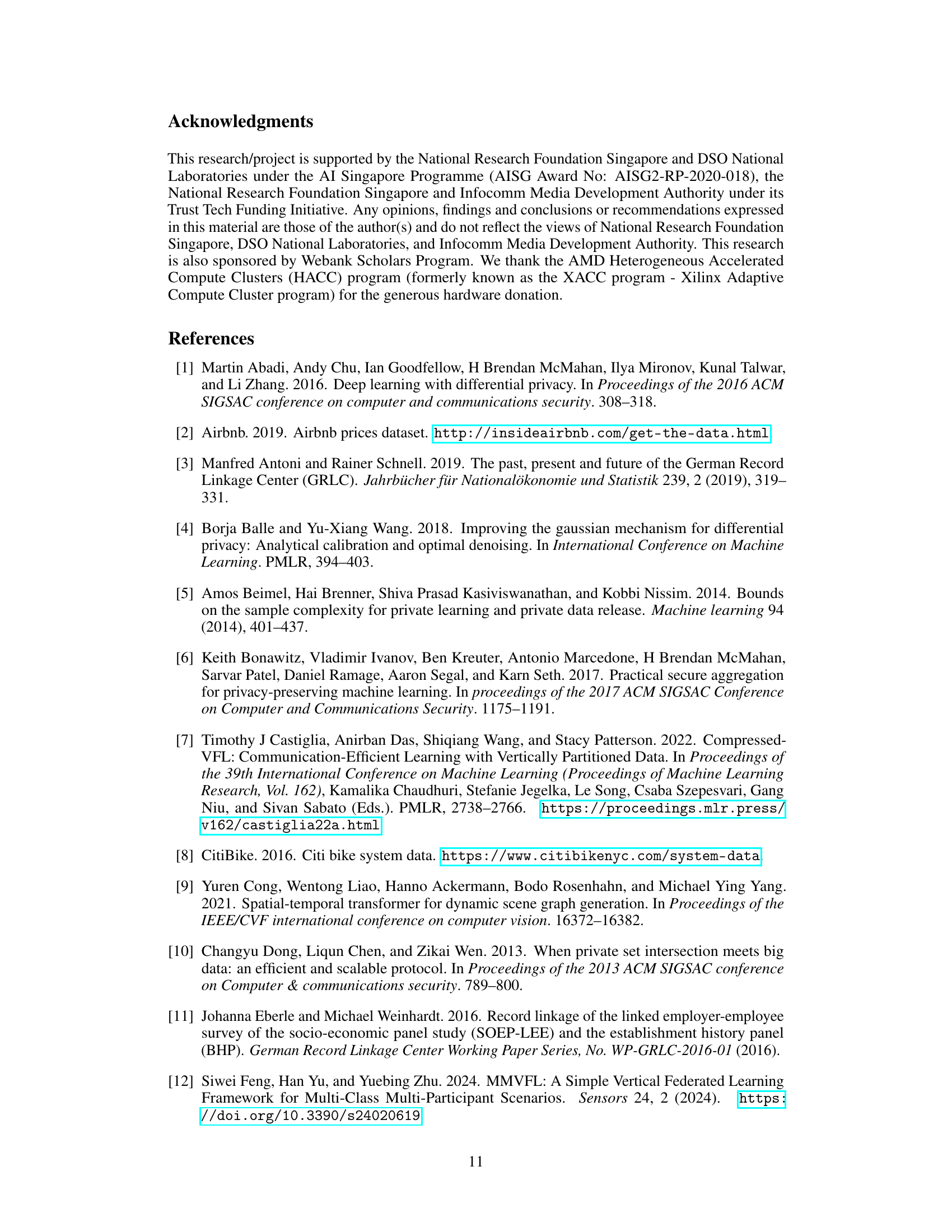

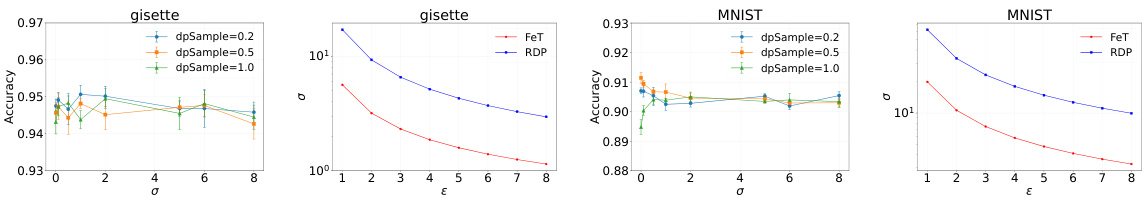

🔼 This figure analyzes the performance of FeT under different privacy levels controlled by noise scale (σ) and sampling rate on secondary parties. The left two subfigures show accuracy vs. noise scale (σ) on gisette and MNIST datasets, while the right two subfigures show the relationship between privacy parameter (ε) and noise scale (σ). It demonstrates FeT’s robustness to increased privacy constraints, even outperforming RDP (without MPC) methods, and highlights the effectiveness of the SplitAvg privacy framework.

read the caption

Figure 8: Impact of noise scale σ on FeT accuracy and relationship between σ and ε under 10-party fuzzy VFL (RDP: without MPC, privacy loss calculated by Rényi differential privacy)

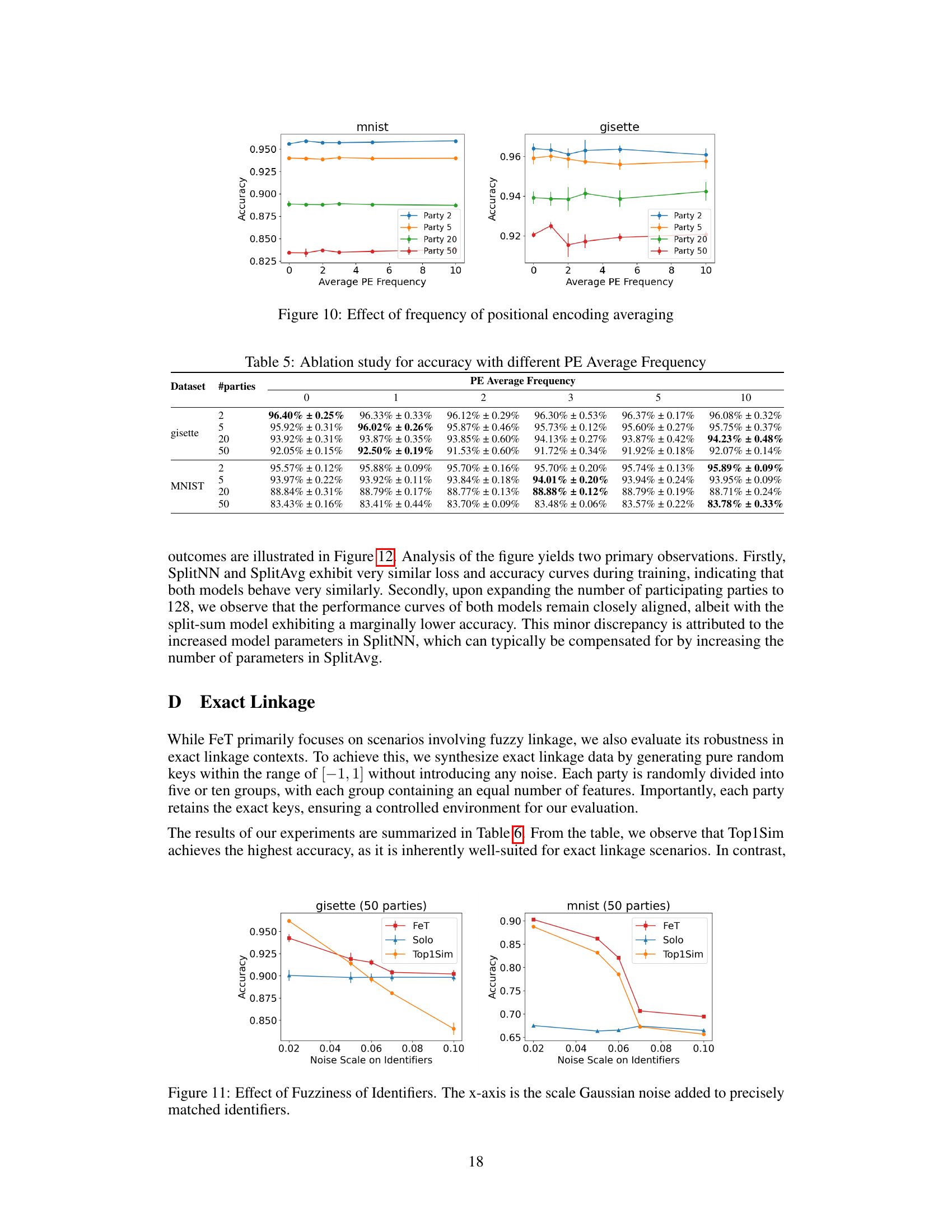

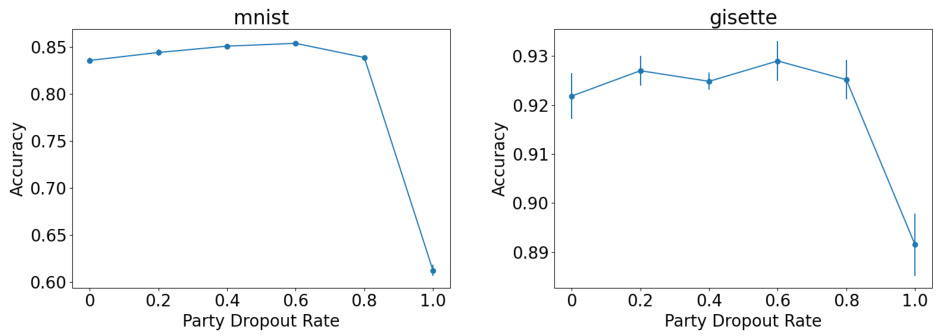

🔼 This figure shows the effect of the party dropout rate on the performance of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model. The left subplot shows the accuracy on the MNIST dataset, while the right subplot shows the accuracy on the gisette dataset. The x-axis represents the party dropout rate, ranging from 0 to 1, while the y-axis represents the test accuracy. The results indicate that a moderate party dropout rate (around 0.6) improves the model’s generalization ability without significantly reducing the accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 9: Effect of party dropout rate on FeT

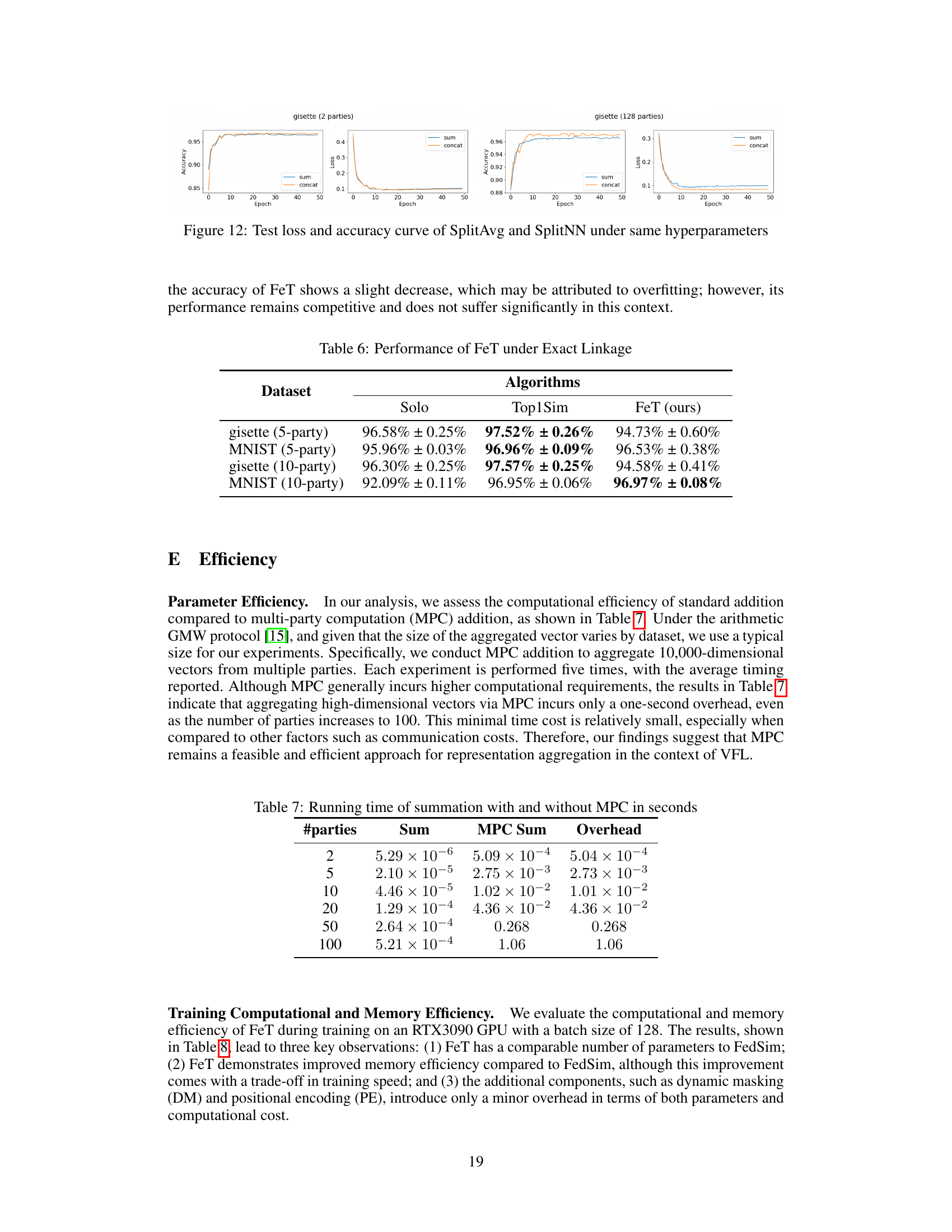

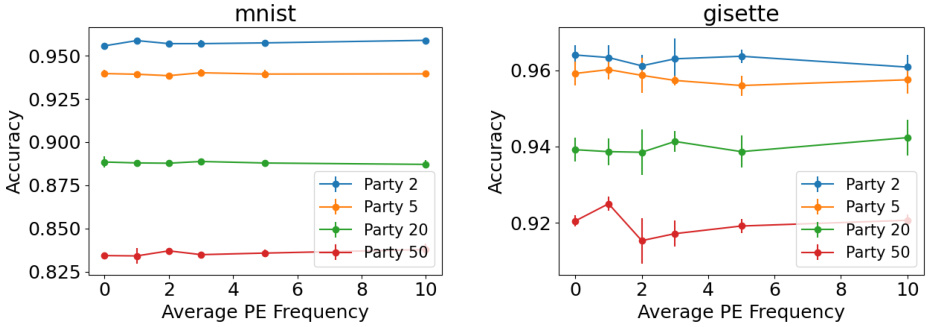

🔼 This figure displays the results of an ablation study on the effect of positional encoding averaging frequency on the performance of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model. The x-axis represents the average positional encoding frequency, and the y-axis represents accuracy. Separate lines show the performance on two datasets (MNIST and gisette) across various numbers of secondary parties (2, 5, 20, and 50). It demonstrates the impact of positional encoding averaging on model accuracy for different numbers of parties and datasets.

read the caption

Figure 10: Effect of frequency of positional encoding averaging

🔼 This figure shows the impact of the number of parties on the performance of FeT and baseline models on the MNIST and gisette datasets. The accuracy is plotted against the number of parties, revealing FeT’s superior performance, especially with a larger number of parties. The underperformance of FeT and other models compared to Solo on the Gisette dataset with k=10 is attributed to overfitting due to the small size of the Gisette dataset.

read the caption

Figure 7: Impact of number of parties on FeT performance

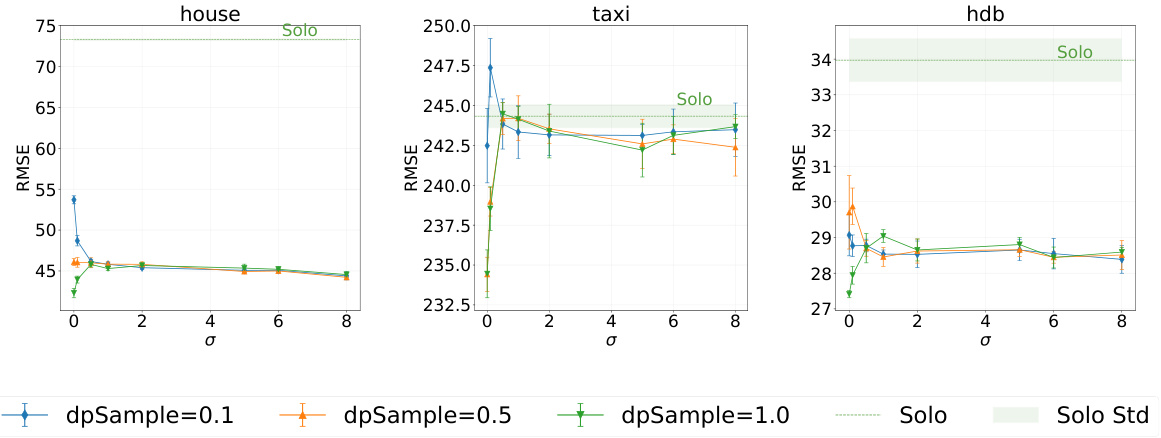

🔼 This figure shows the results of an experiment evaluating the performance of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model under different noise scales (σ) and secondary sampling rates. The x-axis represents the noise scale (σ), and the y-axis represents the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) for regression tasks or accuracy for classification tasks. Separate graphs are shown for three different datasets: house, taxi, and hdb. Each graph shows three lines, corresponding to different secondary sampling rates (dpSample = 0.1, 0.5, and 1.0). Error bars are included. The performance of a baseline model (Solo) is also shown for comparison, highlighting the impact of privacy-preserving techniques on model performance in multi-party fuzzy Vertical Federated Learning (VFL) settings.

read the caption

Figure 13: Impact of noise scale σ on FeT performance

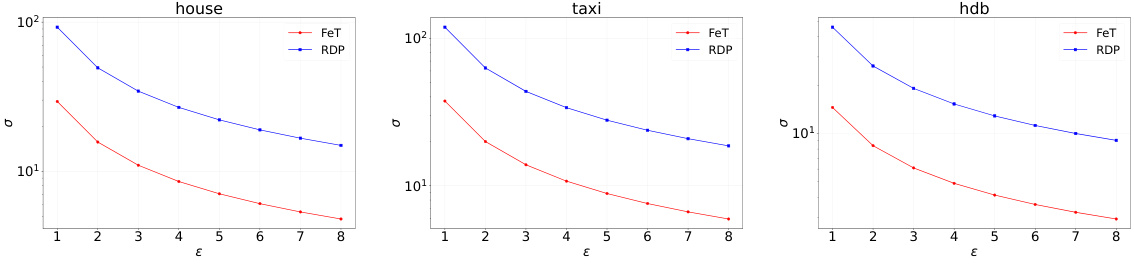

🔼 This figure illustrates the relationship between the privacy parameter ε and the noise scale σ for different real-world datasets (house, taxi, hdb) using the Federated Transformer (FeT) and Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP). It shows how the required noise scale σ changes with different ε values to maintain a certain level of privacy. The plots demonstrate that FeT requires less noise than RDP to achieve the same level of privacy, showcasing its enhanced privacy-preserving capability.

read the caption

Figure 14: Relationship between ε and noise σ

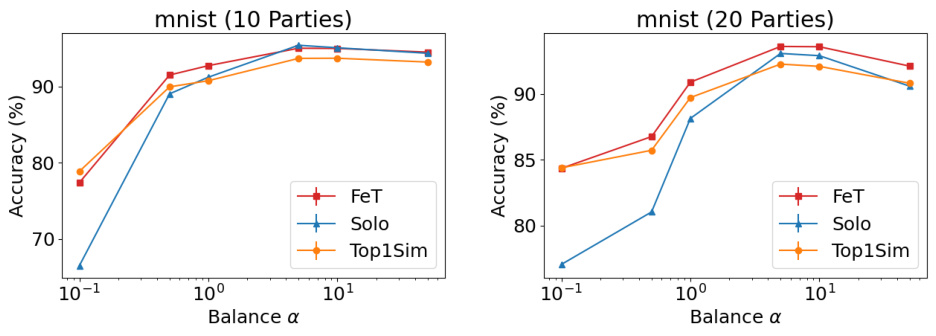

🔼 This figure shows the performance of FeT and baseline methods (Solo and Top1Sim) on the MNIST dataset with varying levels of feature imbalance. The x-axis represents the imbalance factor (α), ranging from 0.1 to 50, where higher values indicate more balanced feature splits across parties. The y-axis shows the test accuracy. The results demonstrate that FeT consistently achieves competitive or superior performance compared to the baseline methods across all levels of imbalance.

read the caption

Figure 15: Performance on feature split with different level of imbalance

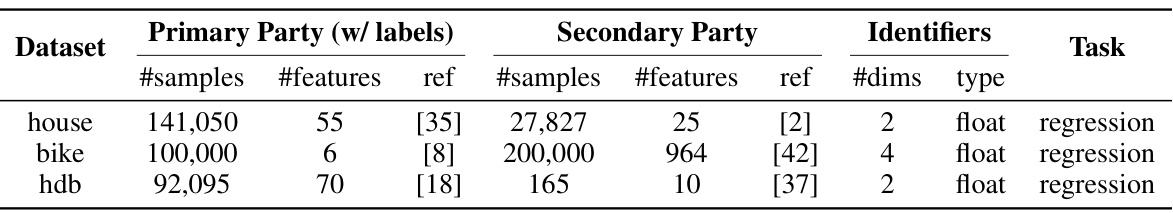

More on tables

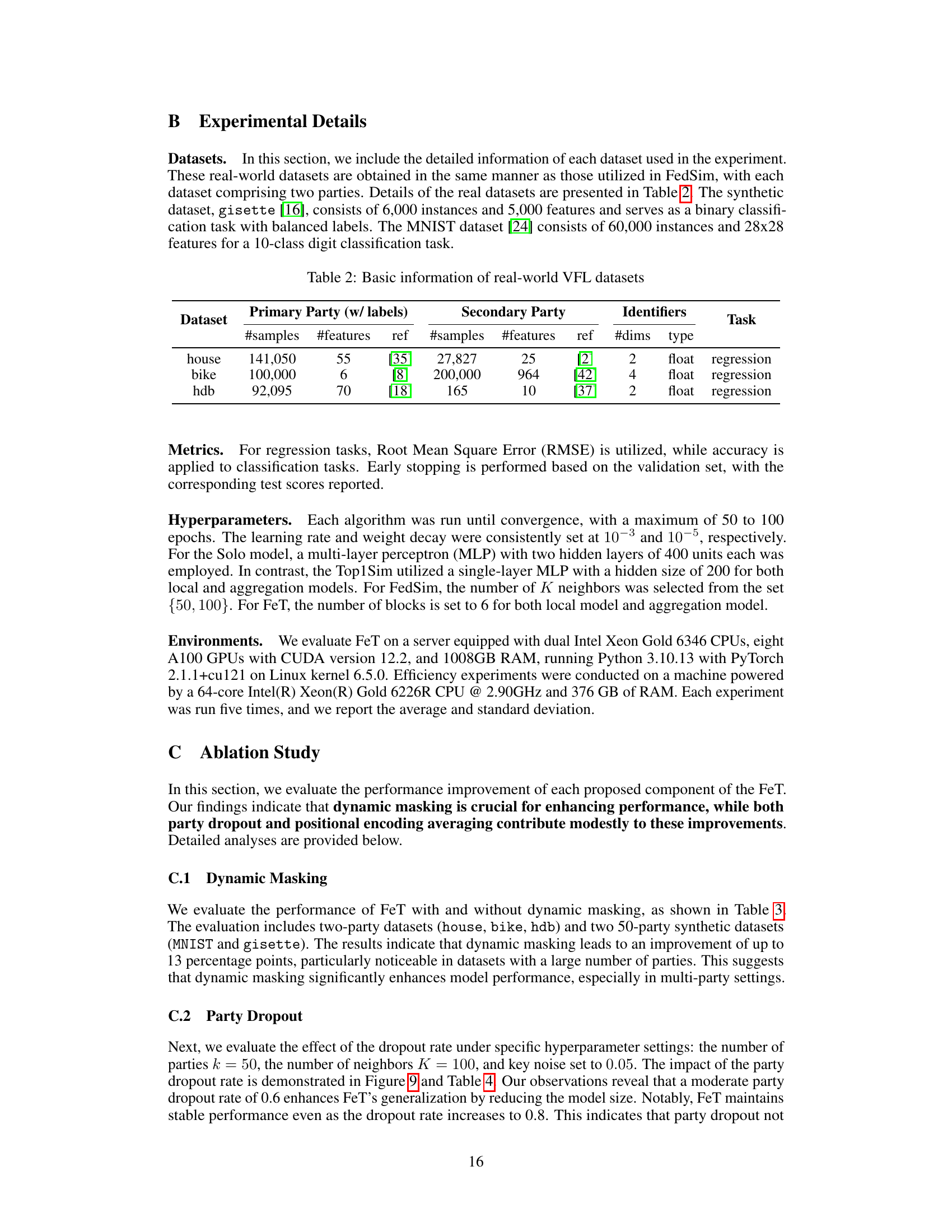

🔼 This table presents the key characteristics of three real-world datasets used in the paper’s experiments to evaluate the performance of the Federated Transformer (FeT) in the context of Vertical Federated Learning (VFL). For each dataset, the table provides the number of samples and features in both the primary party’s dataset (which includes labels) and the secondary party’s dataset. It also indicates the relevant references for each dataset, the number of dimensions for the identifiers used to link the datasets across parties, and the type of task (regression in this case).

read the caption

Table 2: Basic information of real-world VFL datasets

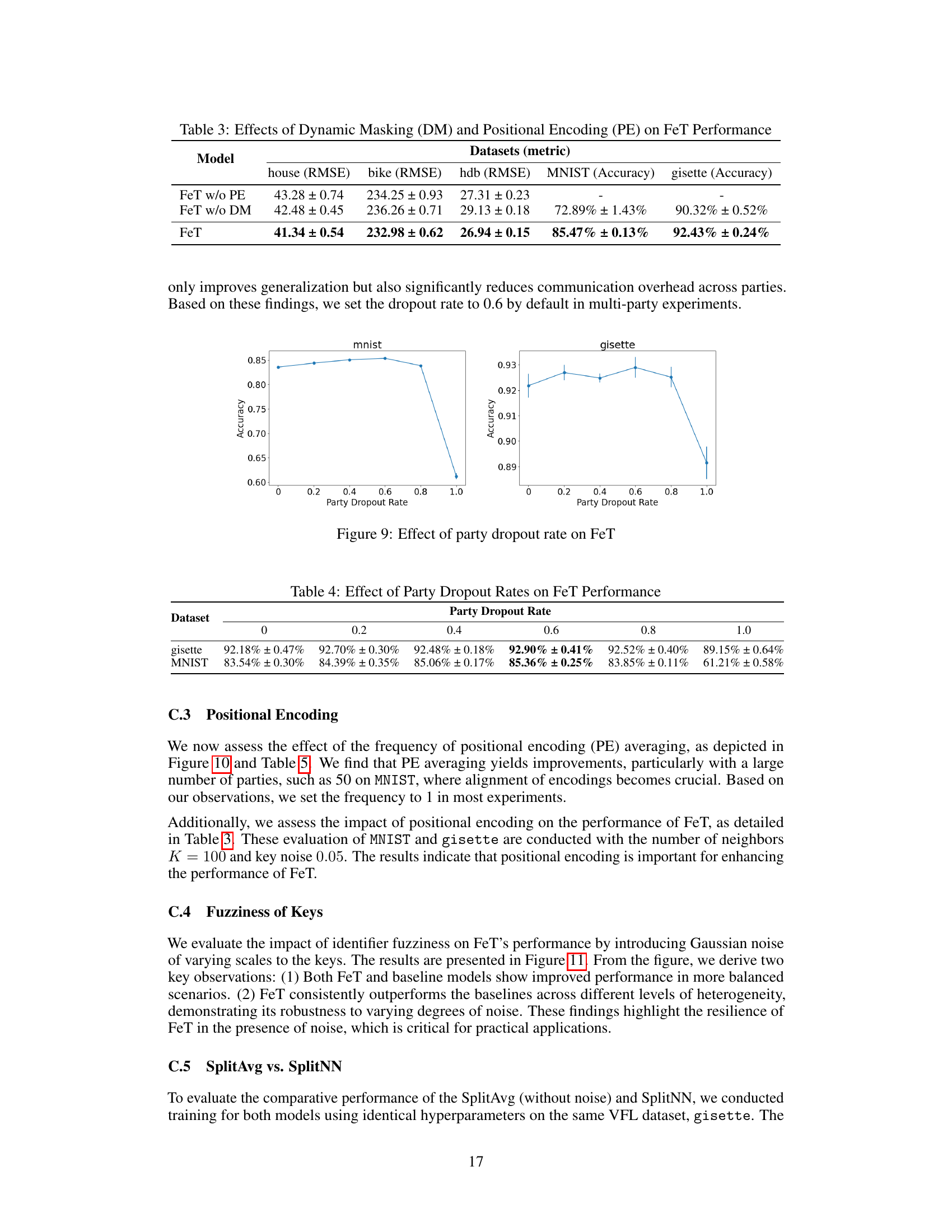

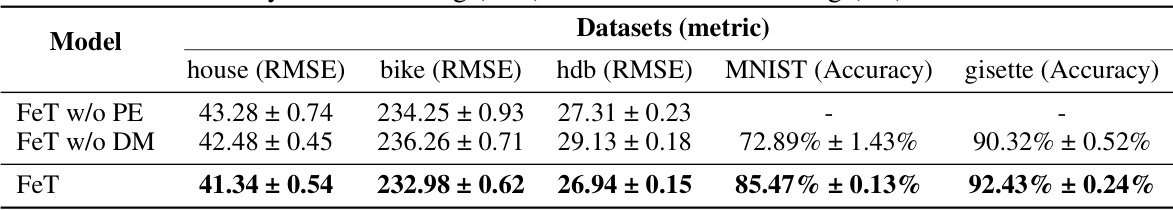

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study evaluating the impact of dynamic masking (DM) and positional encoding (PE) on the performance of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model. It shows the RMSE (Root Mean Squared Error) for regression tasks on three datasets (house, bike, hdb) and accuracy for classification tasks on two datasets (MNIST, gisette). By comparing the performance of FeT with and without DM and PE, the table demonstrates the individual contributions of these components to the overall model performance.

read the caption

Table 3: Effects of Dynamic Masking (DM) and Positional Encoding (PE) on FeT Performance

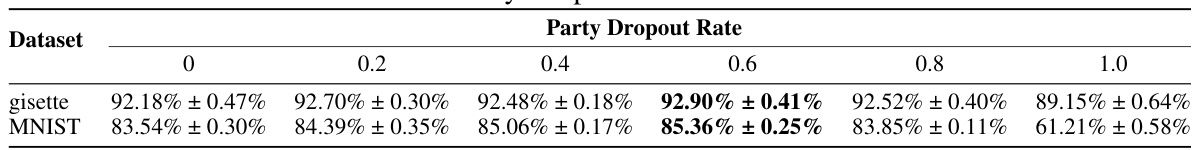

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study evaluating the impact of the party dropout rate on the performance of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model. The study uses two datasets, gisette and MNIST, and varies the party dropout rate from 0 to 1.0. The results show the accuracy achieved on each dataset at each dropout rate, demonstrating the effect of this technique on model generalization and performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Effect of Party Dropout Rate on FeT Performance

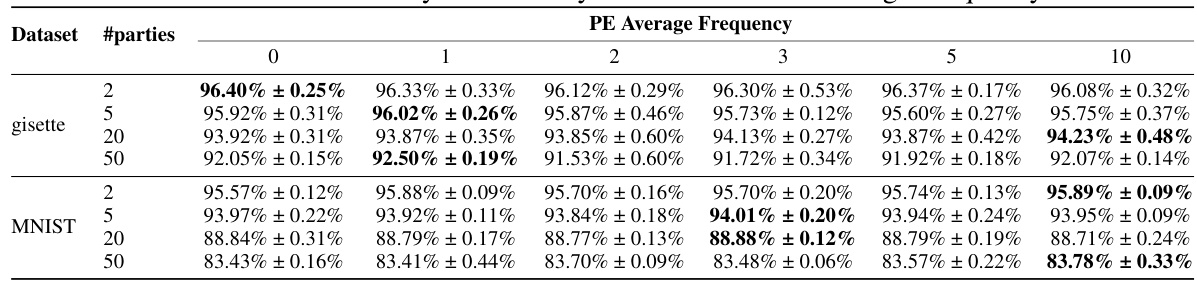

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the effect of positional encoding (PE) averaging frequency on the model’s accuracy. The study is conducted on two datasets (gisette and MNIST) with varying numbers of parties (2, 5, 20, 50). The table shows the accuracy achieved with different PE averaging frequencies (0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 10), allowing for the analysis of how this parameter affects performance under different conditions.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study for accuracy with different PE Average Frequency

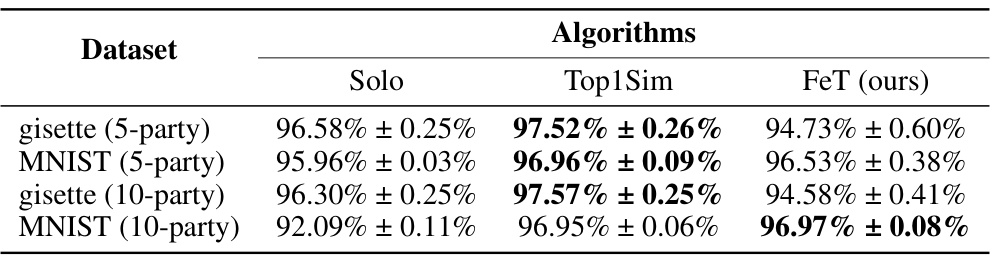

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of FeT against two baselines (Solo and Top1Sim) under the setting of exact linkage, where the keys are precisely matched. It shows the accuracy achieved by each algorithm on two datasets (gisette and MNIST) with different numbers of parties (5 and 10). The results highlight the performance trade-offs between different methods under perfect data alignment, which is a scenario not typically encountered in real-world fuzzy VFL applications.

read the caption

Table 6: Performance of FeT under Exact Linkage

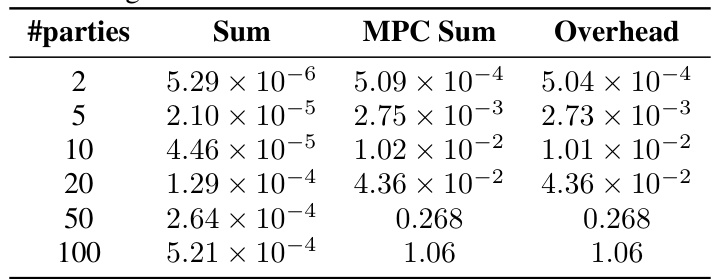

🔼 This table presents the computational efficiency comparison between standard addition and multi-party computation (MPC) addition for aggregating high-dimensional vectors. The results show the running time (in seconds) for different numbers of parties (2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100), using both standard summation and MPC-based summation. The ‘Overhead’ column indicates the additional time cost introduced by using MPC for the aggregation task.

read the caption

Table 7: Running time of summation with and without MPC in seconds

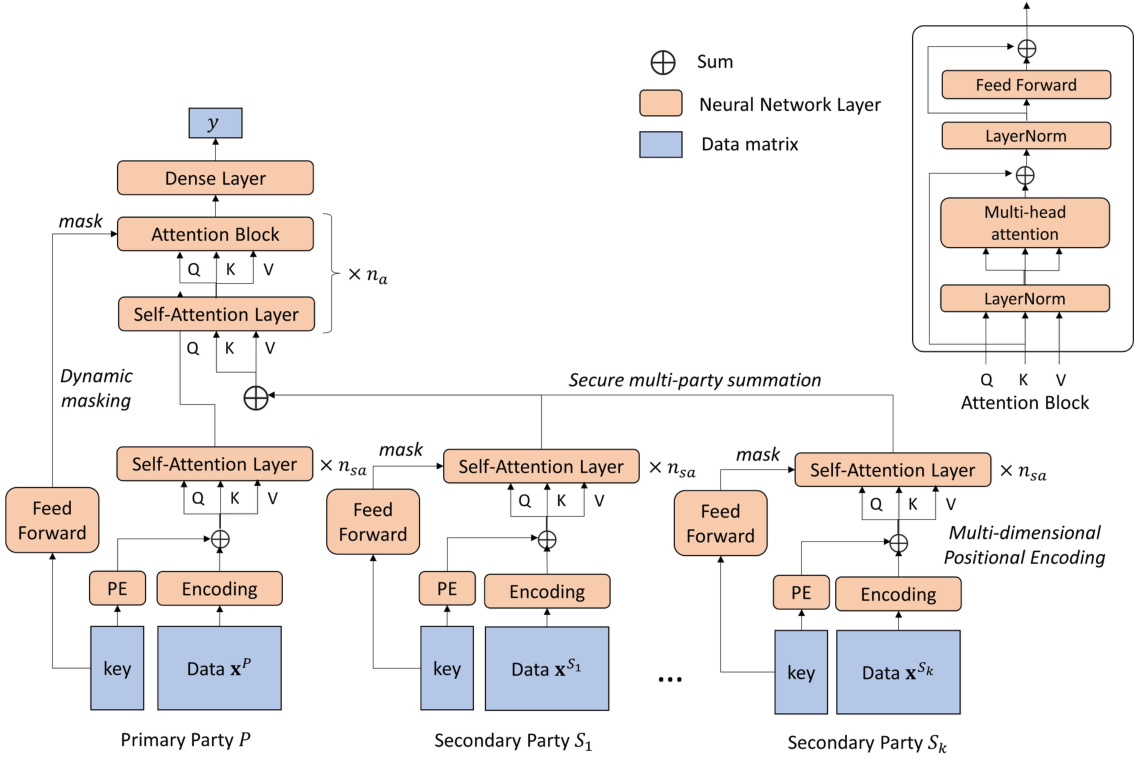

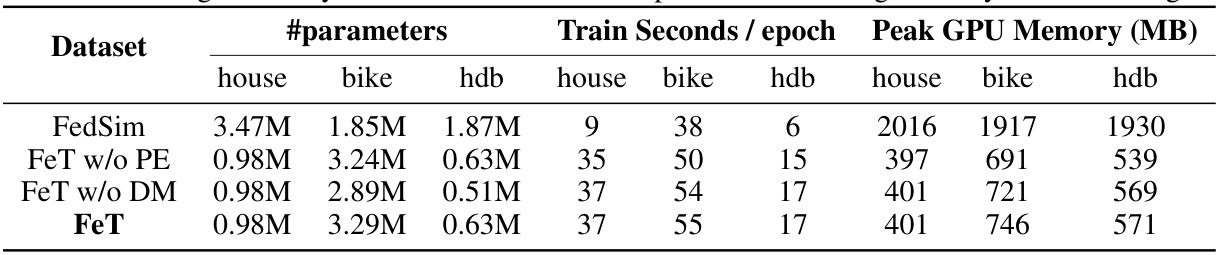

🔼 This table shows a comparison of training efficiency and GPU memory usage for different model configurations. It compares the baseline FedSim model with several versions of the Federated Transformer (FeT) model, each with different components enabled or disabled (positional encoding and dynamic masking). The table details the number of parameters, training time per epoch, and peak GPU memory consumption for each model and dataset (house, bike, hdb).

read the caption

Table 8: Training efficiency of FeT on RTX3090. PE: positional encoding; DM: dynamic masking.

🔼 This table presents the details of the real-world datasets used in the paper’s experiments for two-party fuzzy VFL. It lists the dataset name, the number of samples and features for both the primary (labeled) and secondary (unlabeled) parties, the reference(s) where more information can be found about each dataset, the number of dimensions of the identifiers used to link the datasets, the type of identifier (float), and finally, the type of task (regression).

read the caption

Table 2: Basic information of real-world VFL datasets

Full paper#