TL;DR#

Large language models (LLMs) are trained on massive datasets, raising copyright and privacy concerns. Existing methods to detect if specific text was in an LLM’s training data (membership inference attacks) often fail due to issues such as dataset bias and temporal shifts. This is problematic as it makes proving that copyrighted material was used for training very difficult.

This paper introduces a new approach: dataset inference. Instead of focusing on individual sentences, it assesses whether entire datasets were used for training. The method combines multiple membership inference attacks, focusing on datasets with similar distributions, and uses statistical tests to identify datasets present in an LLM’s training. This approach successfully identifies training datasets and avoids false positives by carefully selecting relevant MIAs and handling distribution differences. The findings significantly improve the ability to identify if copyrighted works were used in LLM training and offer guidelines to enhance future membership inference studies.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it challenges the reliability of existing membership inference attacks against LLMs and proposes a novel dataset inference method that is more robust and realistic for modern copyright concerns. It also offers practical guidelines for future research on membership inference, significantly advancing the field of LLM privacy and accountability.

Visual Insights#

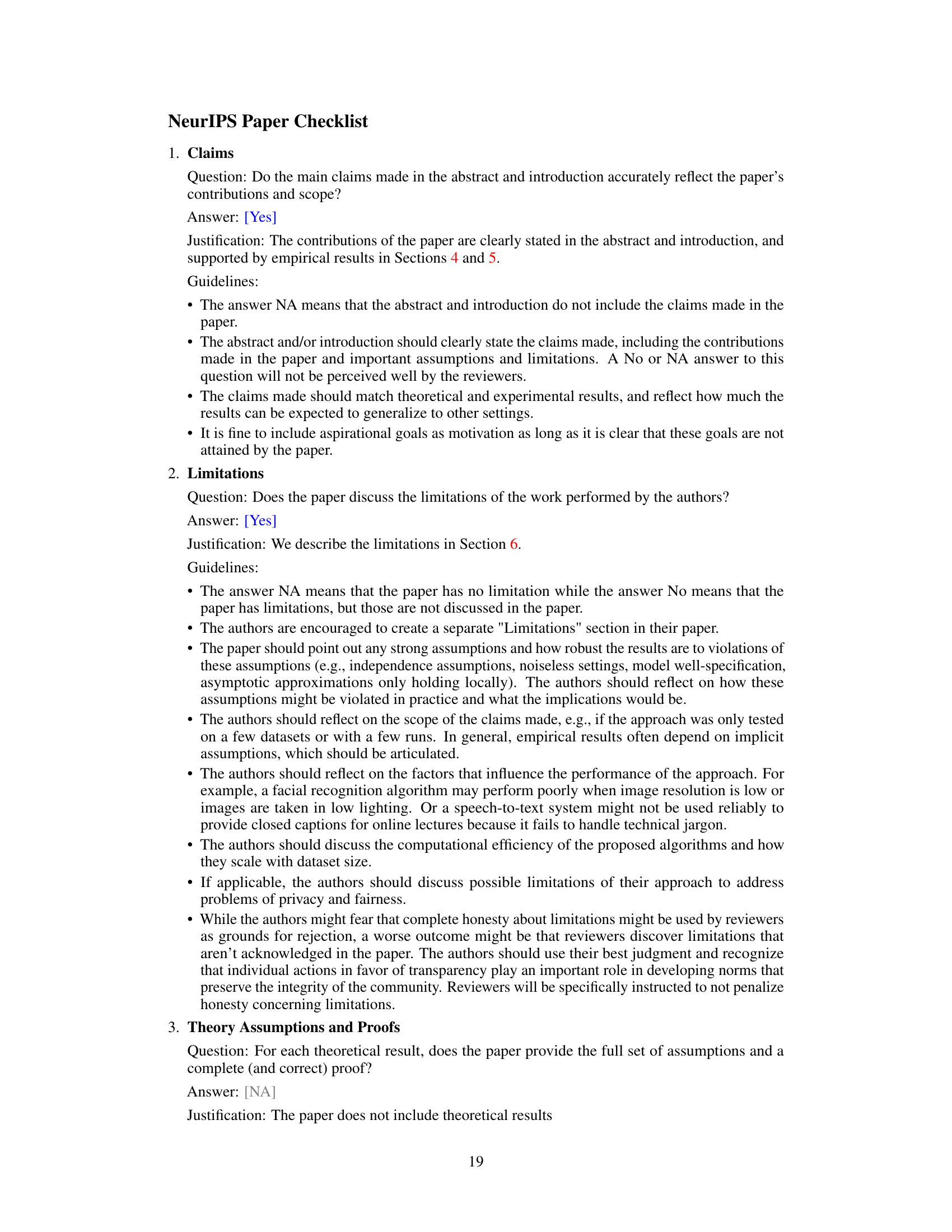

🔼 This figure illustrates the three stages of the proposed LLM dataset inference method. Stage 0 shows the initial setup where a victim claims an LLM was trained on their data. Stage 1 involves using various membership inference attacks (MIAs) to extract features from both suspect and validation datasets. Stage 2 trains a linear model to learn correlations between features and membership status. Finally, Stage 3 uses a t-test to infer dataset membership based on aggregated confidence scores.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

In-depth insights#

LLM Dataset Inference#

The concept of “LLM Dataset Inference” tackles the crucial challenge of determining whether specific datasets were used to train large language models (LLMs). This is particularly important given the legal and ethical implications of using copyrighted or private data in LLM training. Membership inference attacks (MIAs), while seemingly successful at identifying individual data points, are shown to be unreliable due to confounding factors like data distribution shifts. This paper proposes a novel approach to dataset inference, focusing on the distributional properties of entire datasets rather than individual samples. This method leverages the strengths of multiple MIAs, combining their results using a statistical test to robustly distinguish between training and test datasets, demonstrating statistically significant results. The study highlights the inherent limitations of MIAs and advocates for a more effective and realistic approach to dataset attribution in the realm of LLMs.

MIA Limitations#

Membership inference attacks (MIAs) against large language models (LLMs) face significant limitations. The success of many MIAs is often confounded by data distribution shifts, making it difficult to ascertain true membership. MIAs struggle to generalize across different data distributions, implying their results are highly context-dependent. Existing MIAs frequently exhibit a high rate of false positives, especially when applied to LLMs with large training sets. The inherent difficulty in distinguishing between true membership and temporal shifts or stylistic variations in data is a major challenge. Improved methods are necessary to mitigate these limitations, incorporating techniques that explicitly account for data distribution, temporal dynamics, and robustness checks to reduce false positive rates. Ultimately, relying solely on MIAs for copyright or privacy claims involving LLMs remains unreliable without further refinement.

Dataset Inference Method#

The proposed ‘Dataset Inference Method’ offers a novel approach to address the limitations of membership inference attacks (MIAs) in the context of large language models (LLMs). Instead of focusing on individual data points, it leverages the distributional properties of entire datasets, aiming to detect whether a specific dataset was used during training. This shift in perspective is crucial because it reflects real-world copyright infringement scenarios where entire works, not just individual sentences, are at stake. The method’s success hinges on combining multiple MIAs in a statistically robust manner, utilizing a linear regression model to determine the relative importance of different MIA signals, thereby achieving statistically significant results. The ability to aggregate weak signals from various MIAs is key to distinguishing between training and validation datasets, while mitigating the impact of noisy and unreliable signals from individual MIAs. The approach also demonstrates a high degree of accuracy and robustness, with statistically significant p-values and an absence of false positives in distinguishing between different subsets of the Pile dataset. Overall, the dataset inference framework provides a more practical and legally relevant solution for copyright infringement detection compared to traditional MIAs.

Robustness and Generalizability#

A robust and generalizable model is crucial for real-world applications. Robustness refers to the model’s ability to maintain performance despite variations in input data, such as noise or adversarial attacks. Generalizability, on the other hand, focuses on how well the model performs on unseen data drawn from a different distribution than the training data. A thorough evaluation of both aspects is necessary to assess a model’s reliability and practical utility. In the context of large language models (LLMs), achieving robustness and generalizability is particularly challenging due to the sheer scale and complexity of the data used for training. A model that exhibits high robustness and generalizability will be less prone to errors caused by unforeseen variations or biases in the data and demonstrate better reliability. Therefore, rigorous testing involving diverse and challenging datasets is vital to evaluating these critical attributes.

Future Research#

The section on future research in this paper would ideally delve into several crucial aspects. First, it should address the limitations of current membership inference attacks (MIAs) for LLMs, highlighting their susceptibility to confounding factors like temporal distribution shifts. A deeper investigation into developing more robust MIAs that can accurately identify membership regardless of such shifts is essential. Second, the focus should expand beyond individual data point identification to explore the potential of dataset inference techniques in copyright infringement cases. Further research could investigate the effectiveness of various statistical tests for dataset inference under different conditions, as well as exploring methods for handling non-IID datasets. Third, given the success of the proposed dataset inference method, future research should assess its scalability and generalizability for larger LLMs and various types of datasets. The computational cost and resource requirements, along with the reliability under different access levels, need further exploration. Finally, a comprehensive ethical analysis of dataset inference should be undertaken, exploring its potential to safeguard artist rights while carefully examining the potential for misuse and abuse.

More visual insights#

More on figures

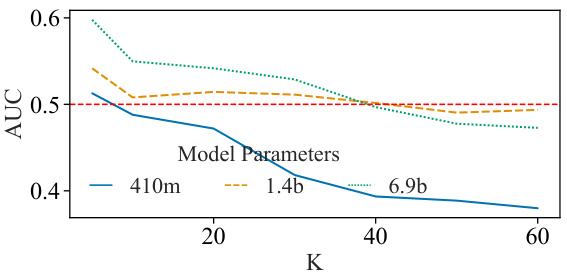

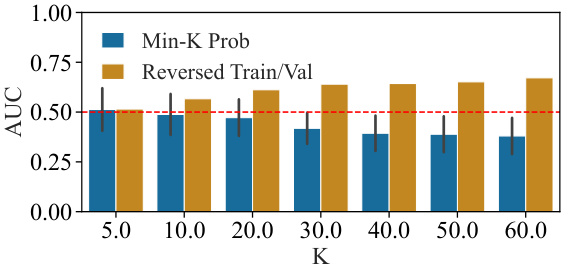

🔼 This figure shows the results of a comparative analysis of the MIN-K% PROB membership inference attack proposed by Shi et al. (2024). Subfigure (a) illustrates the performance of the method across various model sizes, demonstrating that its effectiveness diminishes as model parameters increase. Subfigure (b) highlights a counterintuitive ‘reversal effect,’ where the method shows high performance in identifying non-members when the training and validation sets are reversed, contradicting the claim of successful membership inference. This suggests that the method’s performance is influenced by distribution shift rather than true membership.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparative analysis of the MIN-K% PROB [Shi et al., 2024]. We measure the performance (a) across different model sizes and (b) the observed reversal effect. The method performs close to a random guess on non-members from the Pile validation sets.

🔼 This figure shows a comparative analysis of the MIN-K% PROB membership inference attack proposed by Shi et al. (2024). Subfigure (a) displays the performance of the method across various model sizes, indicating that its accuracy is close to random guessing when tested on non-member sentences from the Pile dataset’s validation sets. Subfigure (b) illustrates a reversal effect, showing high accuracy when the training and validation sets are swapped, suggesting that the method is sensitive to data distribution shifts rather than true membership.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparative analysis of the MIN-K% PROB [Shi et al., 2024]. We measure the performance (a) across different model sizes and (b) the observed reversal effect. The method performs close to a random guess on non-members from the Pile validation sets.

🔼 This figure illustrates the three stages of the proposed LLM dataset inference method. The victim provides a suspect dataset (potentially used in training) and a private validation dataset to the arbiter. Feature aggregation using multiple membership inference attacks (MIAs) is performed on both datasets, followed by training a linear model to learn correlations between features and membership. Finally, a statistical test (t-test) is applied to infer whether the suspect dataset was used in training based on aggregated confidence scores.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

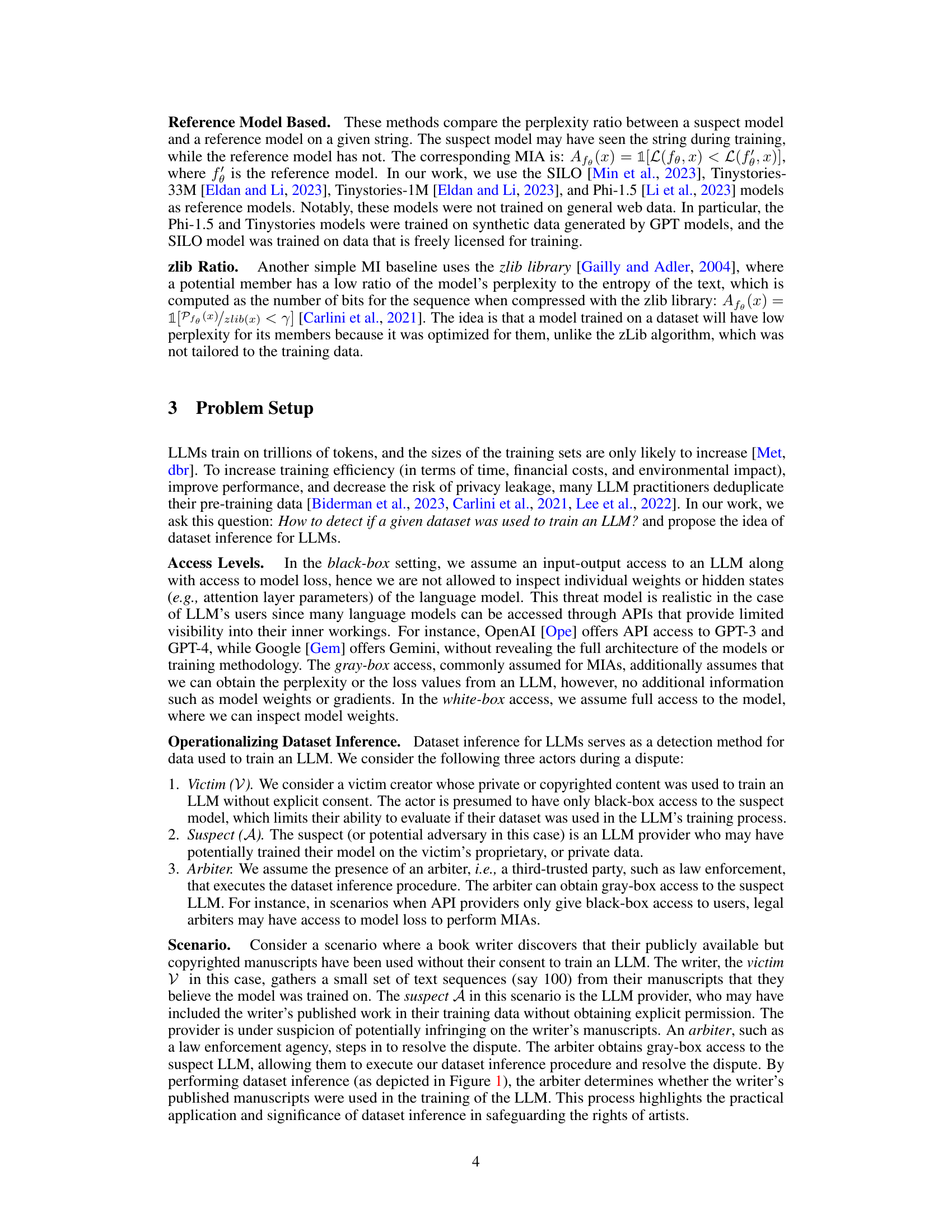

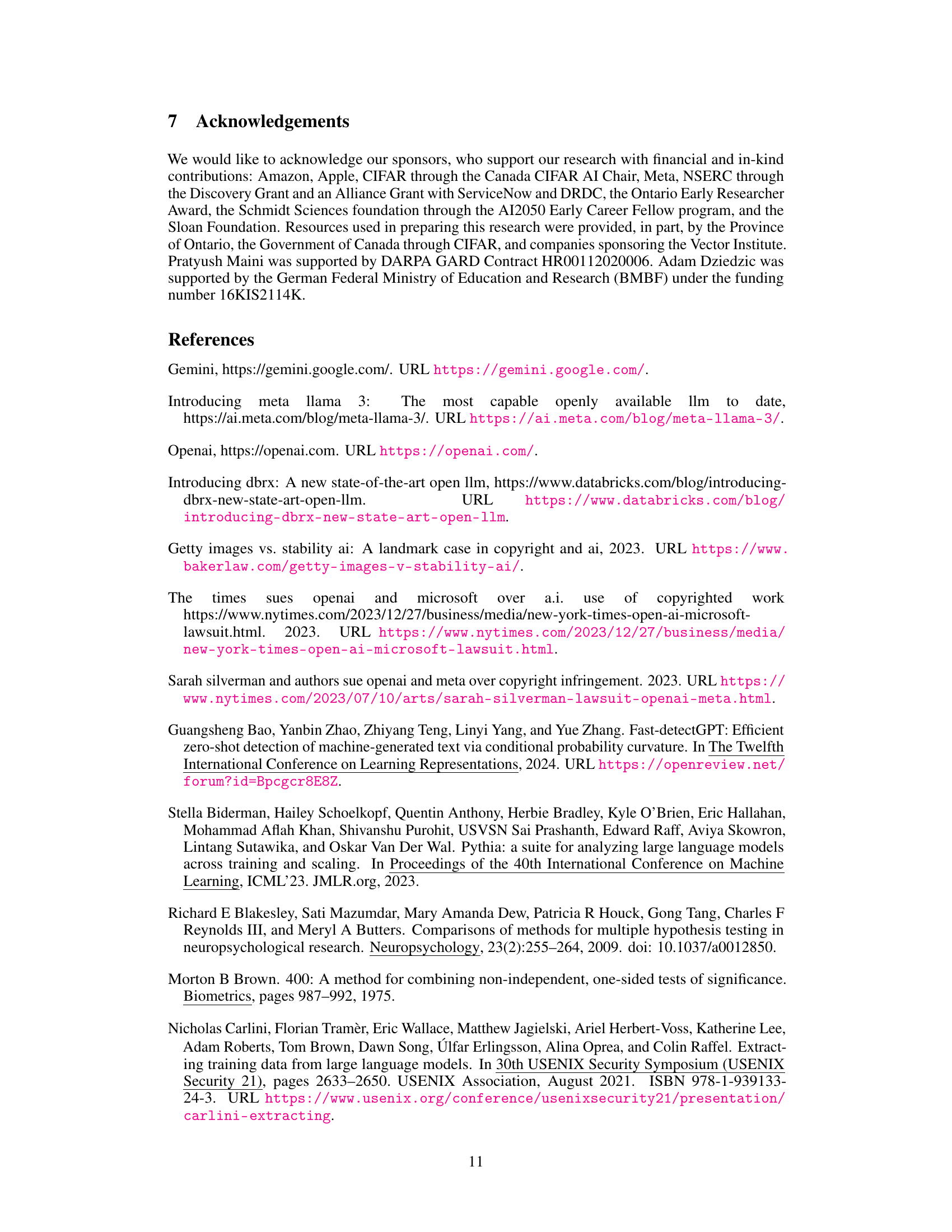

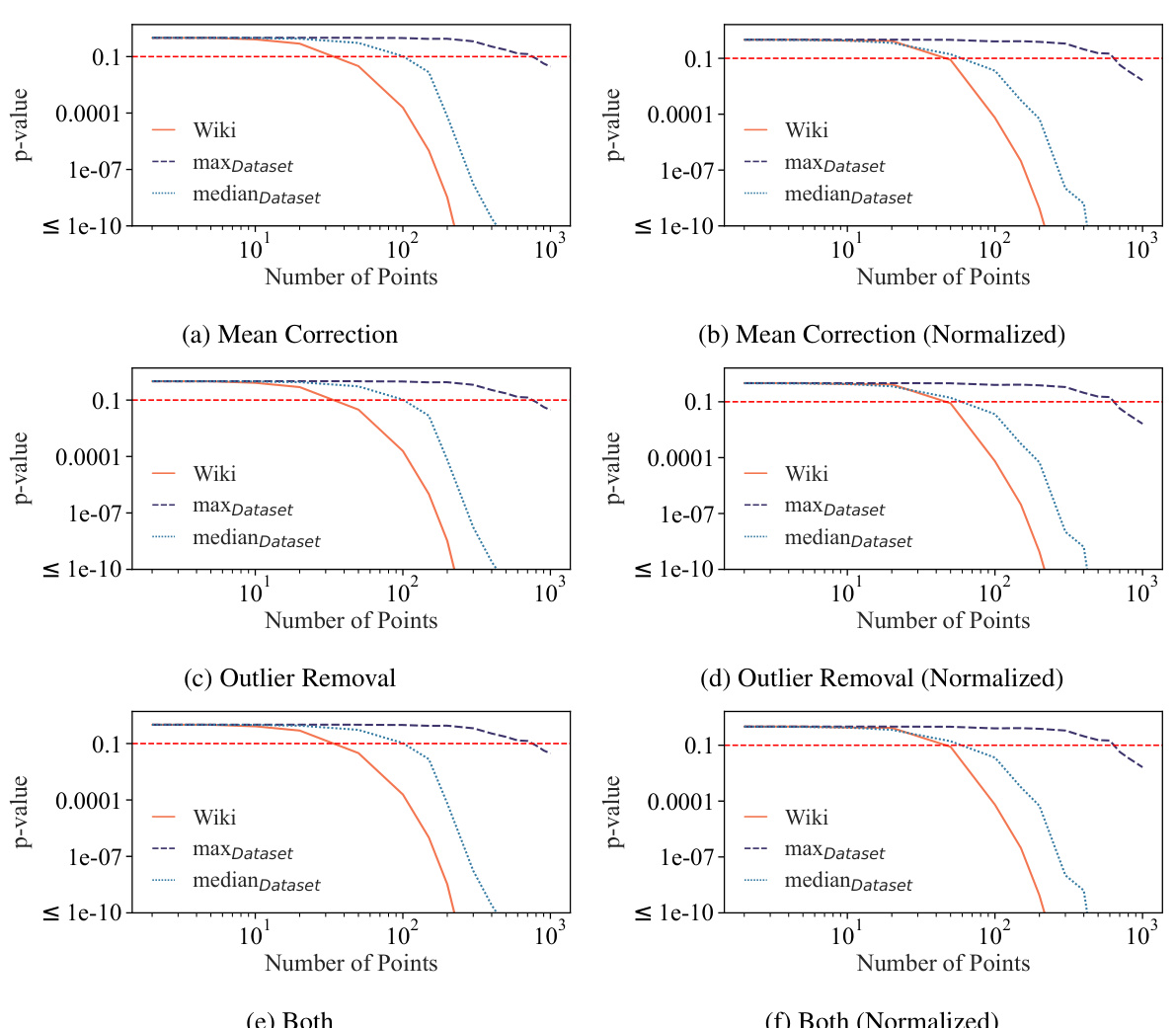

🔼 This figure shows the results of dataset inference experiments conducted on Pythia-12b models using 1000 data points. The experiment aims to distinguish between training and validation splits of the Pile dataset. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed dataset inference method, achieving statistically significant p-values below 0.1 in all cases for distinguishing between training and validation sets. Importantly, no false positives were observed when comparing two validation subsets.

read the caption

Figure 4: p-values of dataset inference By applying dataset inference to Pythia-12b models with 1000 data points, we observe that we can correctly distinguish train and validation splits of the PILE with very low p-values (always below 0.1). Also, when considering false positives for comparing two validation subsets, we observe a p-value higher than 0.1 in all cases, indicating no false positives.

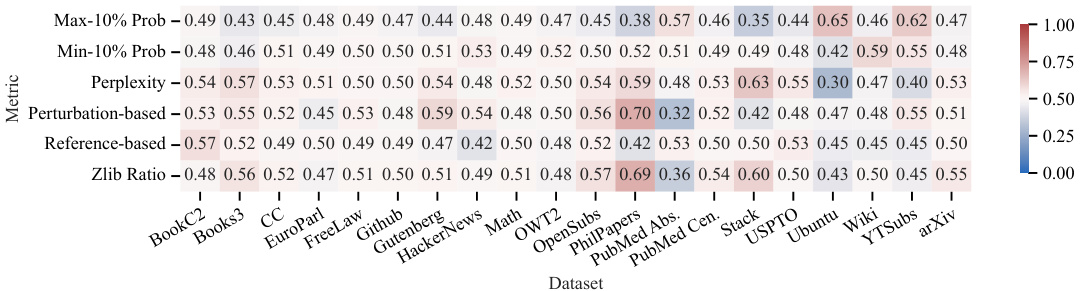

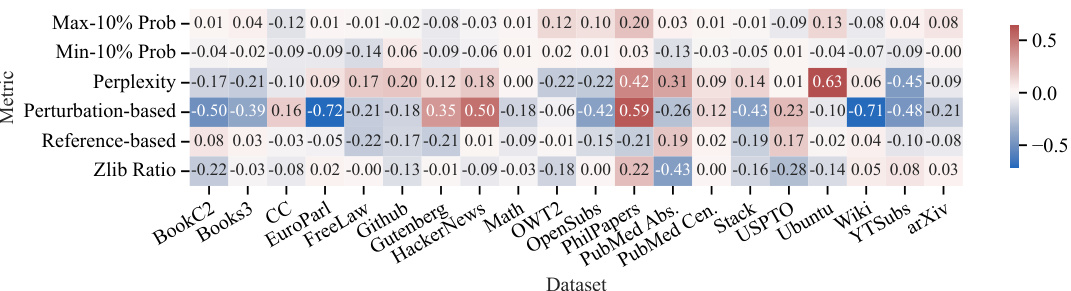

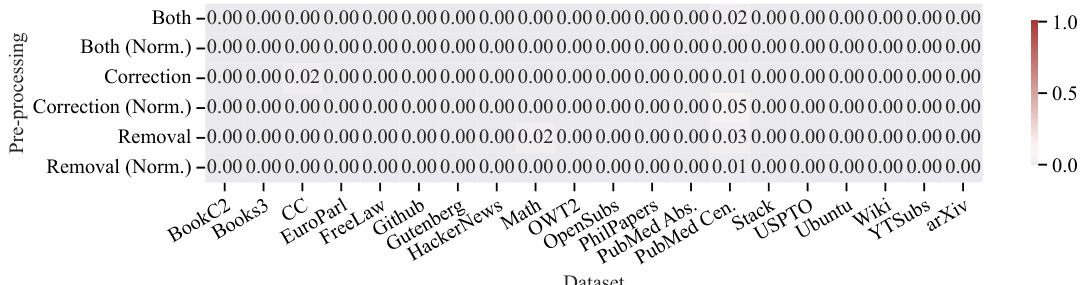

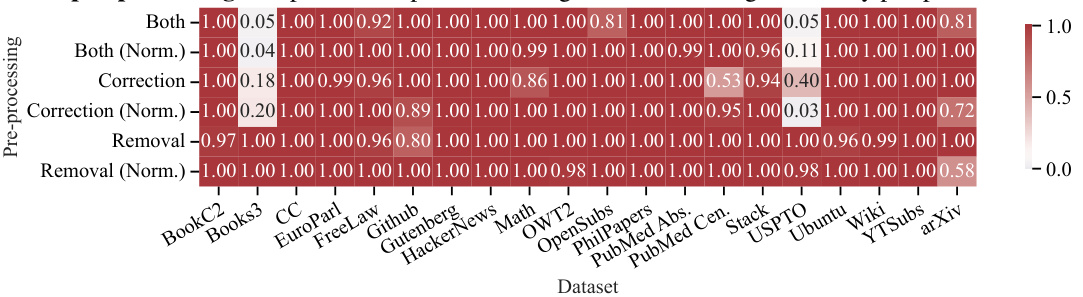

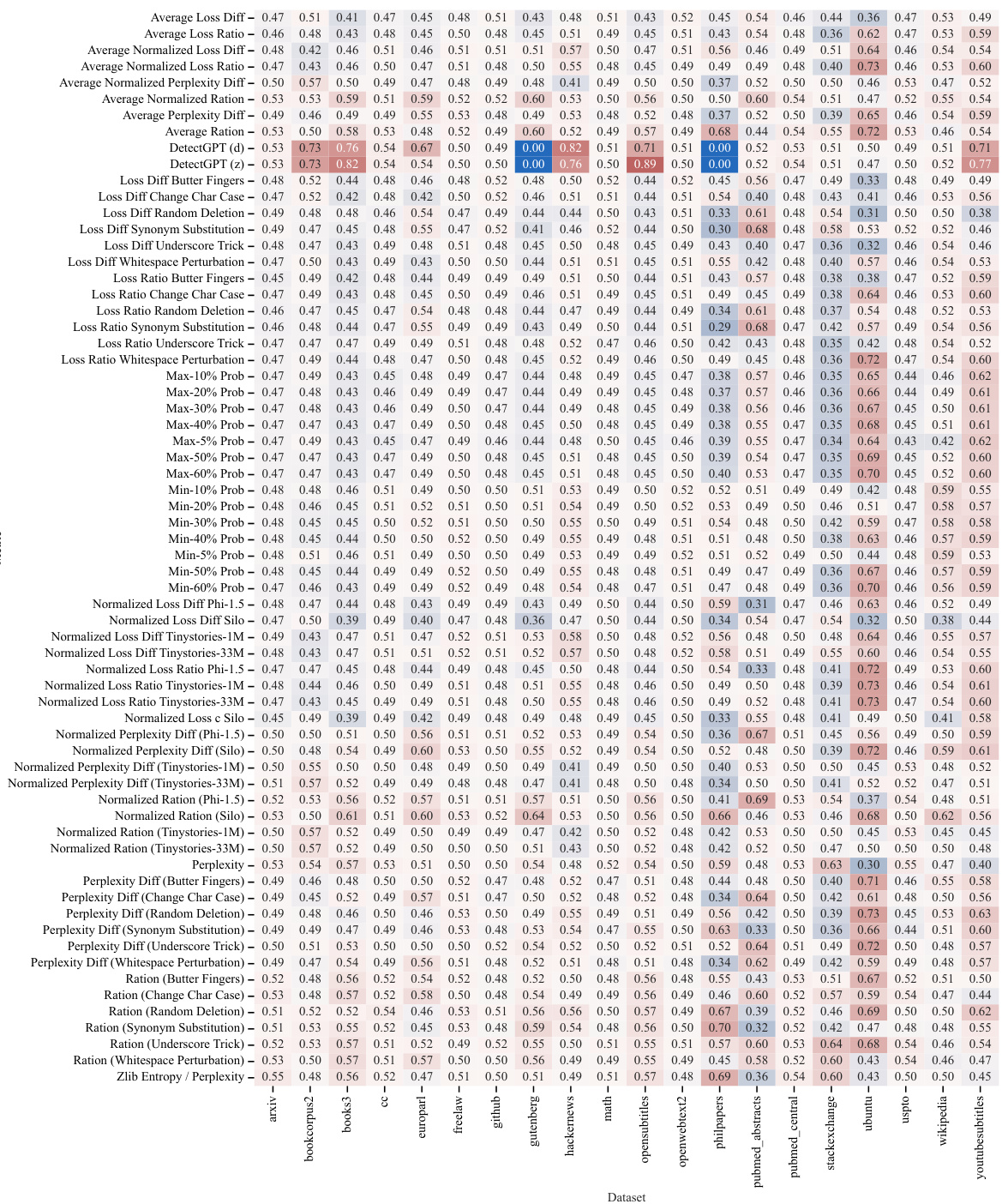

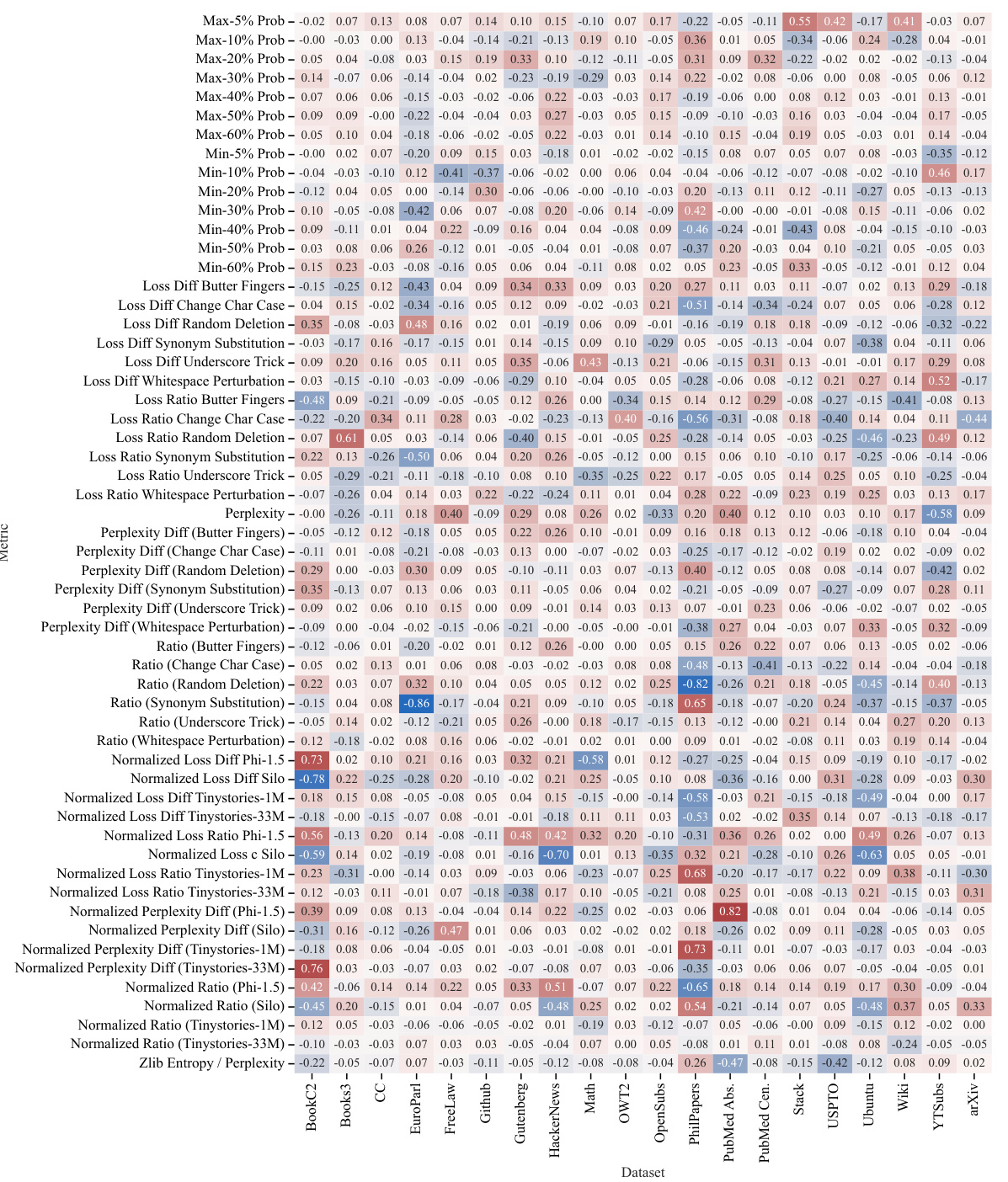

🔼 The figure shows the performance of six different membership inference attack (MIA) methods across twenty different subsets of the Pile dataset. The results highlight the inconsistency of MIA performance across different datasets, demonstrating that no single MIA consistently achieves high Area Under the Curve (AUC) values across various data distributions. This finding underscores the challenges of reliably detecting membership based on individual text sequences within LLMs trained on massive datasets.

read the caption

Figure 3: Performance of various MIAs on different subsets of the Pile dataset. We report 6 different MIAs based on the best performing ones across various categories like reference based, and perturbation based methods (Section 2.1). An effective MIA must have an AUC much greater than 0.5. Few methods meet this criterion for specific datasets, but the success is not consistent across datasets.

🔼 This figure illustrates the three stages of the proposed LLM dataset inference method. Stage 0 sets up the scenario with a victim (data owner) and an LLM provider (suspect). Stage 1 aggregates features from various membership inference attacks (MIAs). Stage 2 trains a linear model to learn correlations between features and membership. Finally, Stage 3 performs a statistical test (t-test) to infer if the suspect dataset was used in the LLM’s training.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

🔼 This figure illustrates the three stages of the proposed LLM dataset inference method. Stage 0 shows the victim approaching the LLM provider with suspect and validation datasets. Stage 1 involves using membership inference attacks (MIAs) to extract features from both datasets. Stage 2 focuses on training a linear model to identify useful MIAs for distinguishing members and non-members. Finally, Stage 3 utilizes the trained model to perform a statistical test on the remaining data to determine whether the suspect dataset was used in training the LLM.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

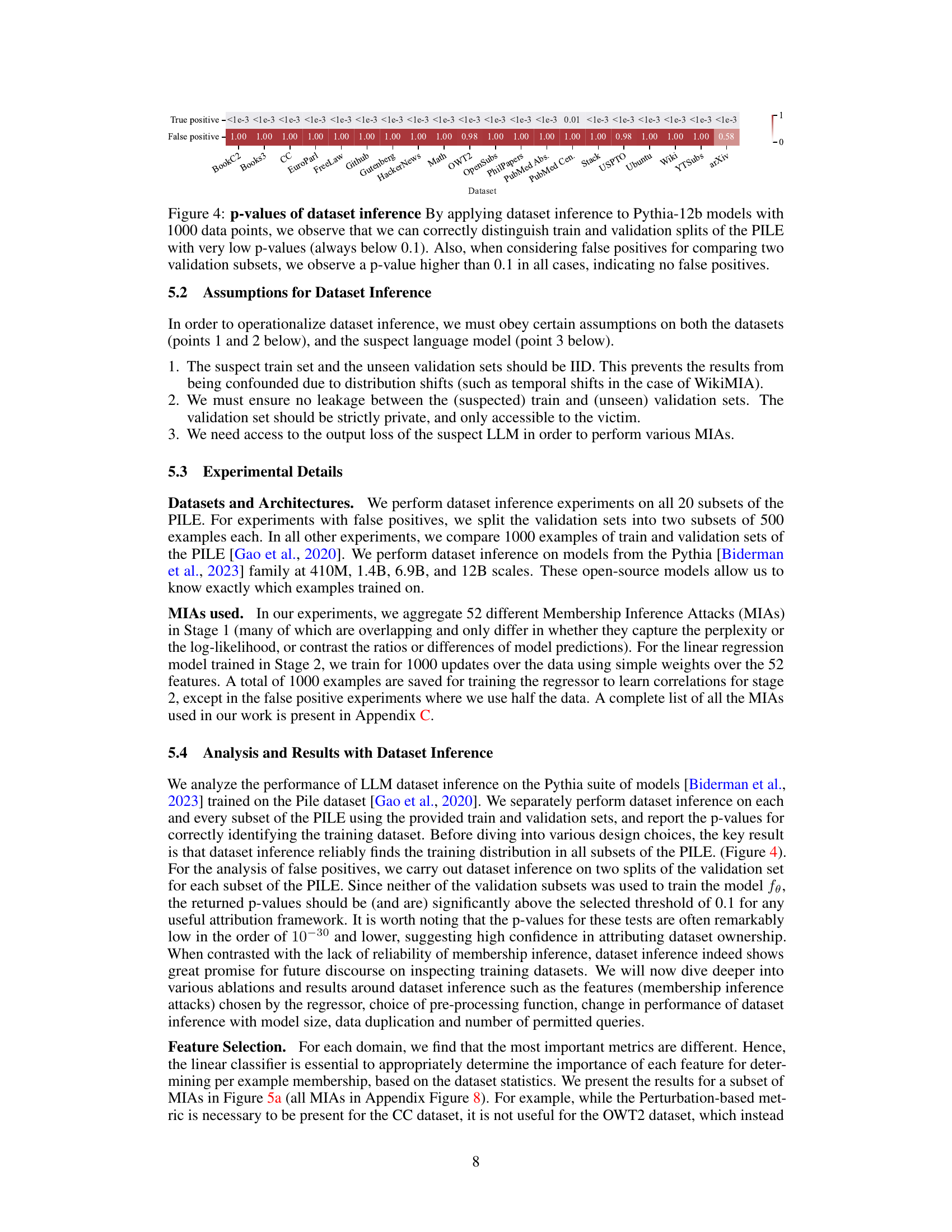

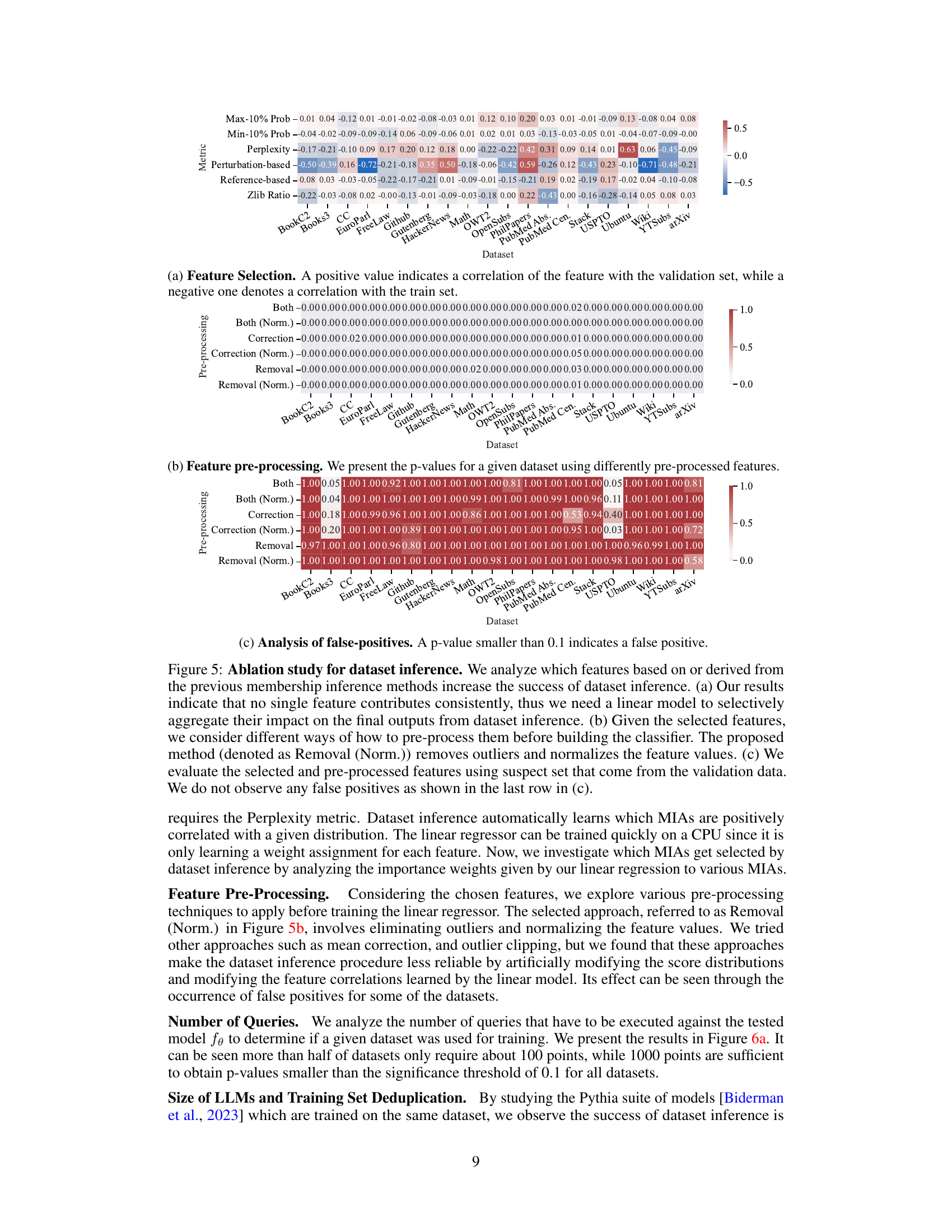

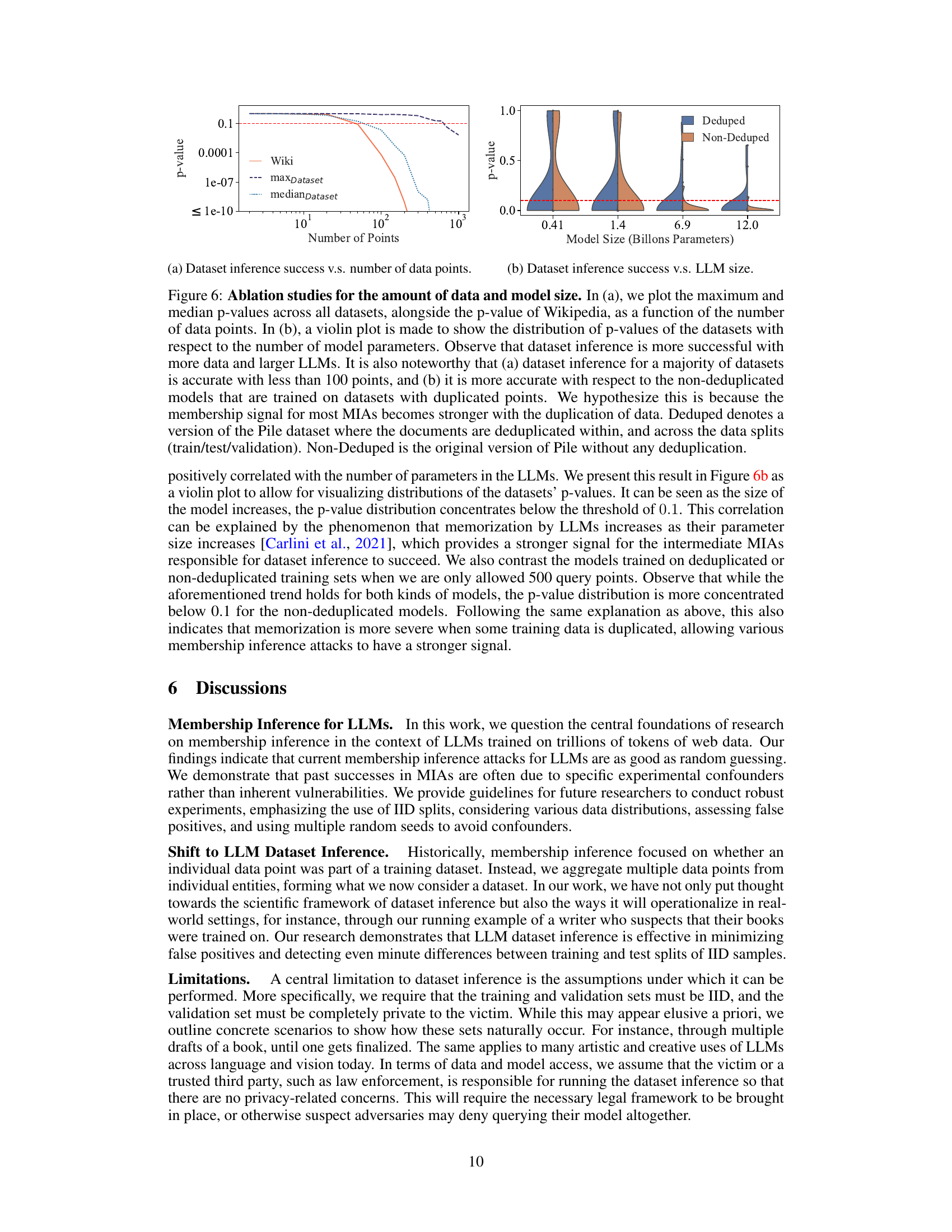

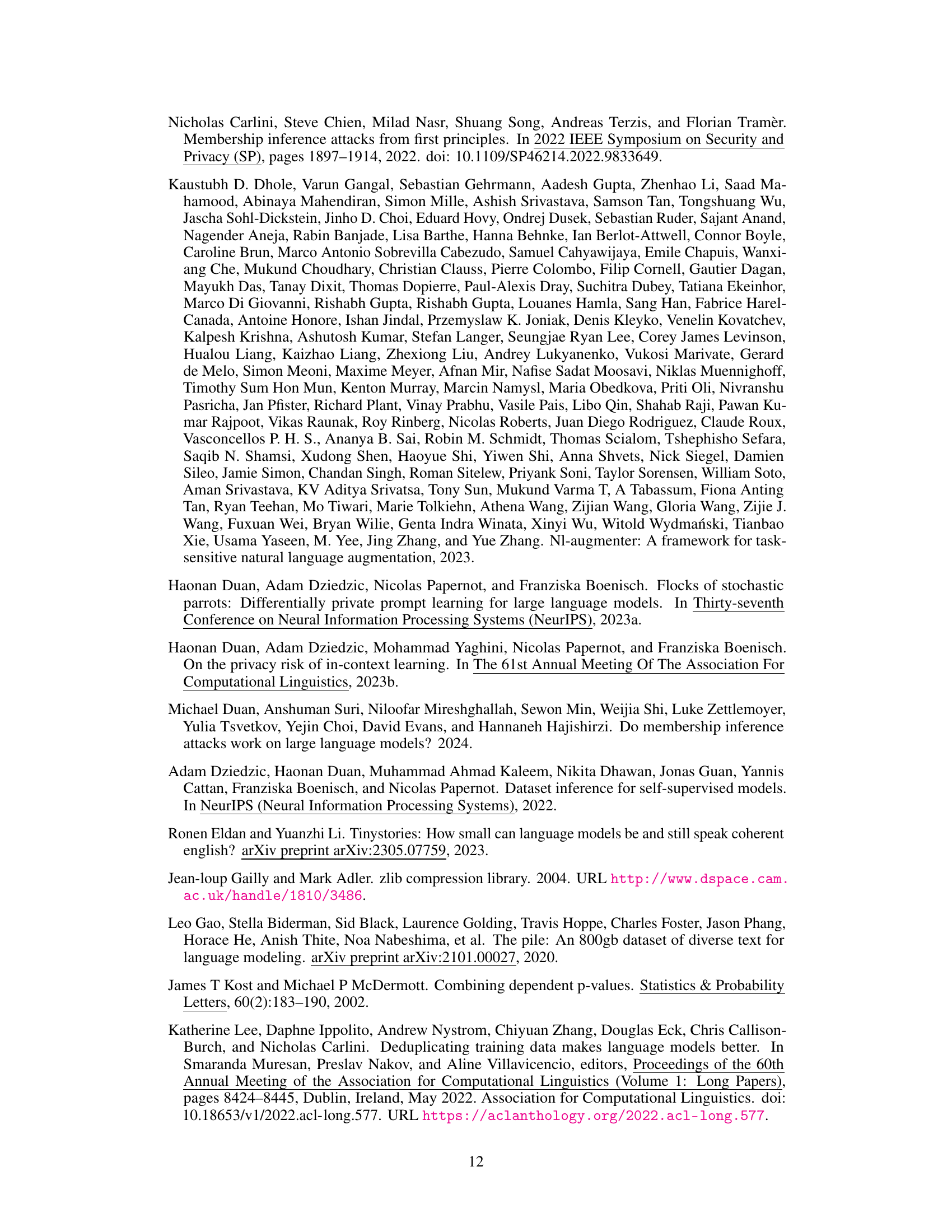

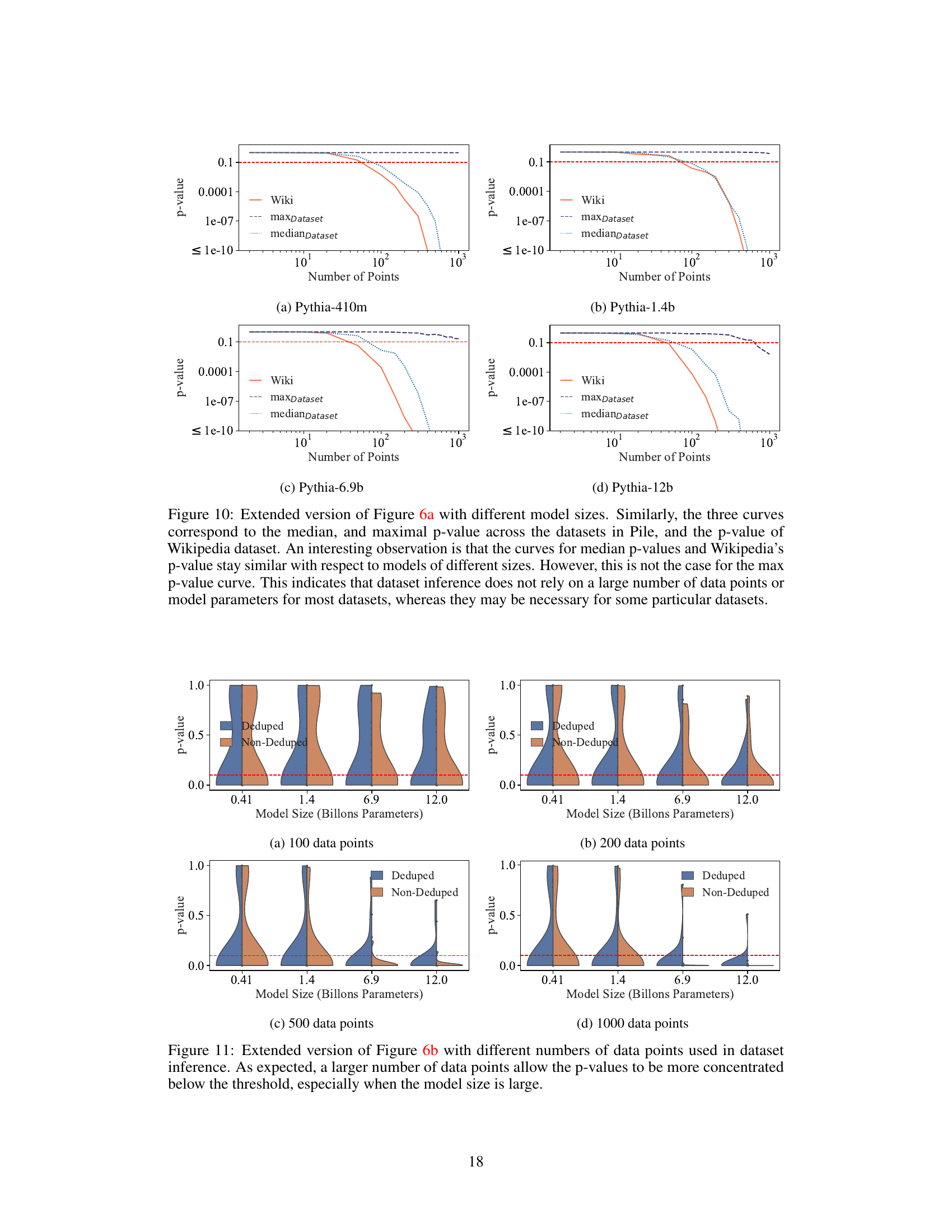

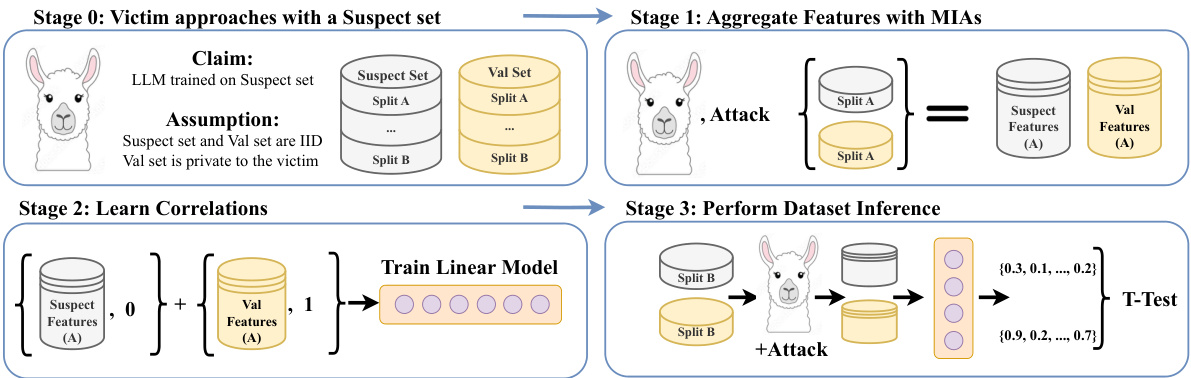

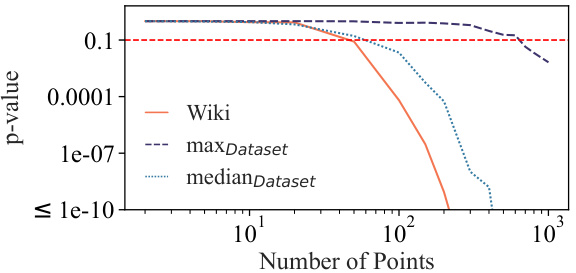

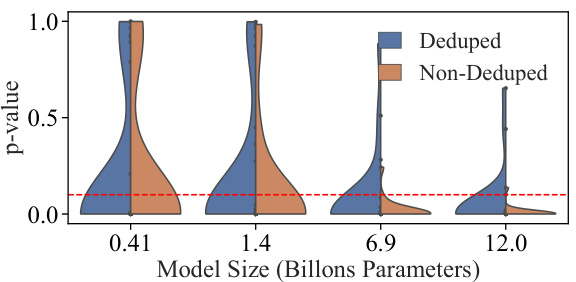

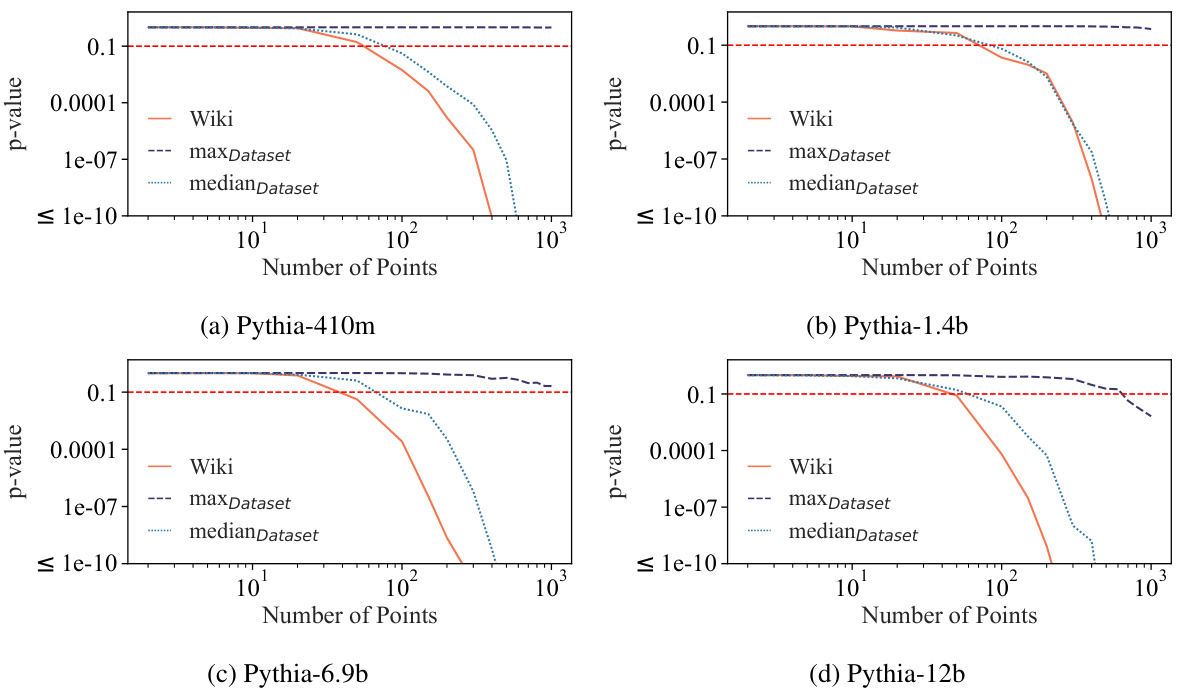

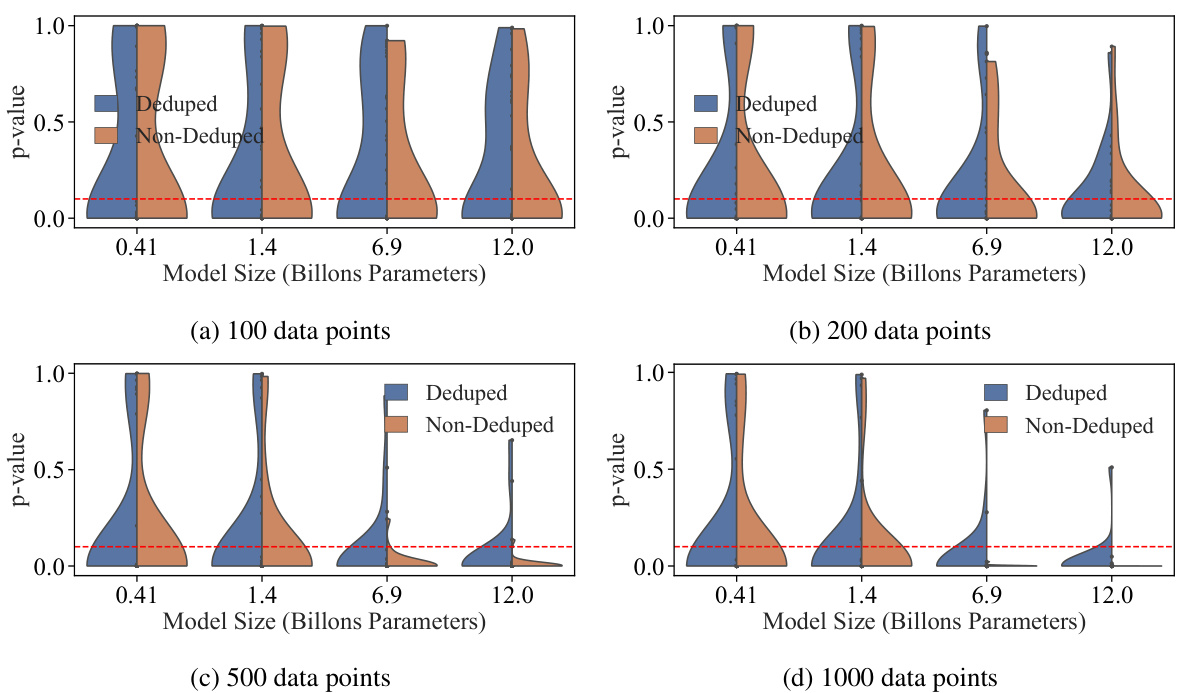

🔼 This figure shows the results of ablation studies on the effect of the number of data points and model size on the success of dataset inference. The left panel (a) plots the maximum and median p-values across all datasets against the number of data points, showing that dataset inference becomes more accurate with more data. The right panel (b) uses violin plots to show the distribution of p-values for different model sizes, demonstrating improved accuracy with larger models. The authors also note that dataset inference is more successful with non-deduplicated datasets (datasets containing duplicate data points).

read the caption

Figure 6: Ablation studies for the amount of data and model size. In (a), we plot the maximum and median p-values across all datasets, alongside the p-value of Wikipedia, as a function of the number of data points. In (b), a violin plot is made to show the distribution of p-values of the datasets with respect to the number of model parameters. Observe that dataset inference is more successful with more data and larger LLMs. It is also noteworthy that (a) dataset inference for a majority of datasets is accurate with less than 100 points, and (b) it is more accurate with respect to the non-deduplicated models that are trained on datasets with duplicated points. We hypothesize this is because the membership signal for most MIAs becomes stronger with the duplication of data.

🔼 This figure shows the results of ablation studies on the number of data points and model size used in dataset inference. The top row shows that the success of dataset inference increases with more data points and larger model sizes. The bottom row uses violin plots to illustrate this further, demonstrating that dataset inference is more successful with non-deduplicated datasets and larger models.

read the caption

Figure 6: Ablation studies for the amount of data and model size. In (a), we plot the maximum and median p-values across all datasets, alongside the p-value of Wikipedia, as a function of the number of data points. In (b), a violin plot is made to show the distribution of p-values of the datasets with respect to the number of model parameters. Observe that dataset inference is more successful with more data and larger LLMs. It is also noteworthy that (a) dataset inference for a majority of datasets is accurate with less than 100 points, and (b) it is more accurate with respect to the non-deduplicated models that are trained on datasets with duplicated points. We hypothesize this is because the membership signal for most MIAs becomes stronger with the duplication of data.

🔼 This figure illustrates the three-stage process of LLM dataset inference. A victim suspects an LLM was trained on their data (suspect set). They provide this data, along with a private validation set (from the same distribution). Both sets are split into partitions A and B. Stage 1 aggregates features from various membership inference attacks (MIAs) on partition A. Stage 2 trains a linear model to correlate features with membership, identifying useful MIAs. Stage 3 uses partition B to perform dataset inference via the selected MIAs, aggregated scores, and a statistical t-test to determine if the suspect dataset was part of the LLM training data.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

🔼 This figure presents a heatmap illustrating the performance of six different membership inference attack (MIA) methods across 20 distinct subsets of the Pile dataset. The goal is to determine if any MIA consistently performs well across various data distributions. The results show that no single MIA achieves high Area Under the Curve (AUC) values across all datasets, highlighting the need for a more robust method.

read the caption

Figure 3: Performance of various MIAs on different subsets of the Pile dataset. We report 6 different MIAs based on the best performing ones across various categories like reference based, and perturbation based methods (Section 2.1). An effective MIA must have an AUC much greater than 0.5. Few methods meet this criterion for specific datasets, but the success is not consistent across datasets.

🔼 This figure illustrates the three-stage process of LLM dataset inference. A victim, possessing a suspect dataset and a private validation dataset (both from the same distribution), claims the LLM was trained using their suspect data. The process involves aggregating features from various membership inference attacks (MIAs), training a linear model to correlate features with membership, and finally using a statistical t-test to determine if the suspect data was used in training. The figure visually depicts the flow of data and the steps involved in each stage.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

🔼 This figure illustrates the three stages of the LLM Dataset Inference method. Stage 0 sets up the scenario where a user suspects an LLM was trained on their data. Stages 1 and 2 use a subset of the user’s data to train a model to identify useful Membership Inference Attacks (MIAs). In Stage 3, the trained model and remaining data are used to perform a statistical test to determine if the LLM was trained on the suspect data.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

🔼 This figure illustrates the three stages of the LLM dataset inference method. The process starts with a victim approaching an LLM provider with a claim about their data being used in training. It then involves aggregating features from various membership inference attacks (MIAs), followed by training a model to learn correlations between these features and membership status. Finally, a statistical test is performed using the trained model to determine whether the suspect data was indeed used for training.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

🔼 This figure illustrates the three-stage process of LLM dataset inference. Stage 0 sets up the scenario where a victim claims an LLM was trained on their data. Stage 1 aggregates features from various Membership Inference Attacks (MIAs). Stage 2 trains a linear model to correlate features with membership. Stage 3 uses a t-test to determine if a dataset was used in training based on aggregated confidence scores.

read the caption

Figure 1: LLM Dataset Inference. Stage 0: Victim approaches an LLM provider. The victim's data consists of the suspect and validation (Val) sets. A victim claims that the suspect set of data points was potentially used to train the LLM. The validation set is private to the victim, such as unpublished data (e.g., drafts of articles, blog posts, or books) from the same distribution as the suspect set. Both sets are divided into non-overlapping splits (partitions) A and B. Stage 1: Aggregate Features with MIAs. The A splits from suspect and validation sets are passed through the LLM to obtain their features, which are scores generated from various MIAs for LLMs. Stage 2: Learn Correlations (between features and their membership status). We train a linear model using the extracted features to assign label 0 (denoting potential members of the LLM) to the suspect and label 1 (representing non-members) to the validation features. The goal is to identify useful MIAs. Stage 3: Perform Dataset Inference. We use the B splits of the suspect and validation sets, (i) perform MIAs on them for the suspect LLM to obtain features, (ii) then obtain an aggregated confidence score using the previously trained linear model, and (iii) apply a statistical T-Test on the obtained scores. For the suspect data points that are members, their confidence scores are significantly closer to 0 than for the non-members.

Full paper#