TL;DR#

Many real-world classification tasks involve noisy labels, where the assigned labels are incorrect. This is especially challenging when the noise is instance-dependent (i.e., depends on both the true label and data features). Existing methods often struggle with this problem, lacking theoretical backing and practical effectiveness. This paper tackles this issue by developing a novel theoretical framework that quantifies the transferability of information from noisy to clean data using a measure called Relative Signal Strength (RSS).

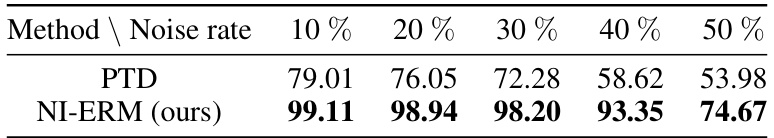

The paper proposes a surprisingly simple approach: Noise-Ignorant Empirical Risk Minimization (NI-ERM). Instead of complex algorithms to correct the noise, NI-ERM directly minimizes the empirical risk as if there were no noise, proving to be nearly optimal under certain conditions. Furthermore, the paper translates this theoretical insight into a practical two-step method combining self-supervised feature extraction with NI-ERM, achieving state-of-the-art performance on the challenging CIFAR-N benchmark dataset. This demonstrates that simple and elegant methods can sometimes outperform more complex approaches in noisy environments.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on robust machine learning and domain adaptation. It provides a novel theoretical framework and practical techniques for handling instance-dependent label noise, a significant challenge in real-world applications. The state-of-the-art results achieved on the CIFAR-N dataset demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed method, paving the way for more robust and reliable machine learning models in noisy environments. The findings could inspire further research into noise-robust algorithms, self-supervised feature extraction, and the theoretical understanding of label noise.

Visual Insights#

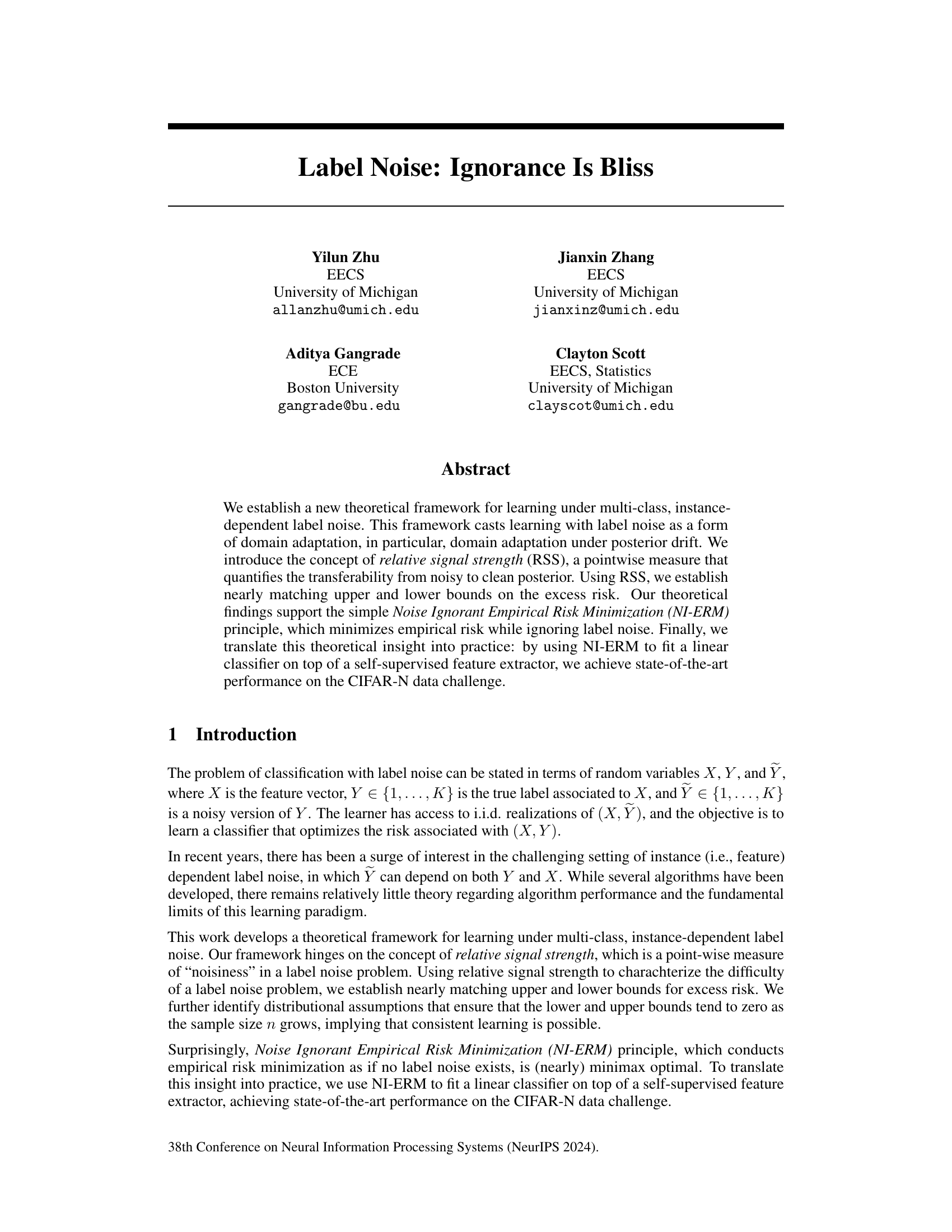

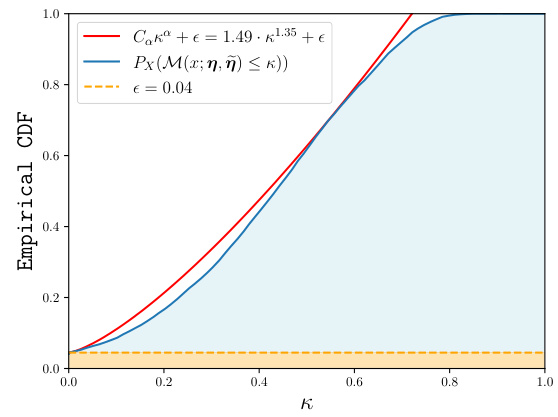

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of relative signal strength (RSS) in binary classification. The left panel shows the clean and noisy class posterior probabilities, P(Y=1|X=x) and P(Ỹ=1|X=x) respectively, as functions of the feature x. The right panel displays the calculated RSS, showing how the ‘signal’ (information about the true label) varies with x. The gray region highlights where the clean and noisy Bayes classifiers disagree (zero signal strength), while the red region indicates where the RSS exceeds 0.4 (high signal strength). The figure demonstrates how RSS quantifies the transferability of information from noisy to clean data, a key concept in the paper’s theoretical framework.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of relative signal strength for binary classification. Left: clean and noisy posteriors [η(x)]₁ = P (Y = 1|X = x) and [ῆ(x)]₁ = P(Ỹ = 1|X = x). Right: relative signal strength corresponding to these posteriors. The gray region, x ∈ (0, 5), is where the true and noisy Bayes classifiers differ, and is also the zero signal region X \ A₀. The red region is A₀.₄, where the RSS is > 0.4. Note that as x ↑ 0, M(x; η, ῆ) ↑ ∞, which occurs since [η(x)]₁ ↑ 1/2, while [ῆ]₁ is far from 1/2. For x → 0+, the predicted labels under η and ῆ disagree, and the RSS crashes to 0.

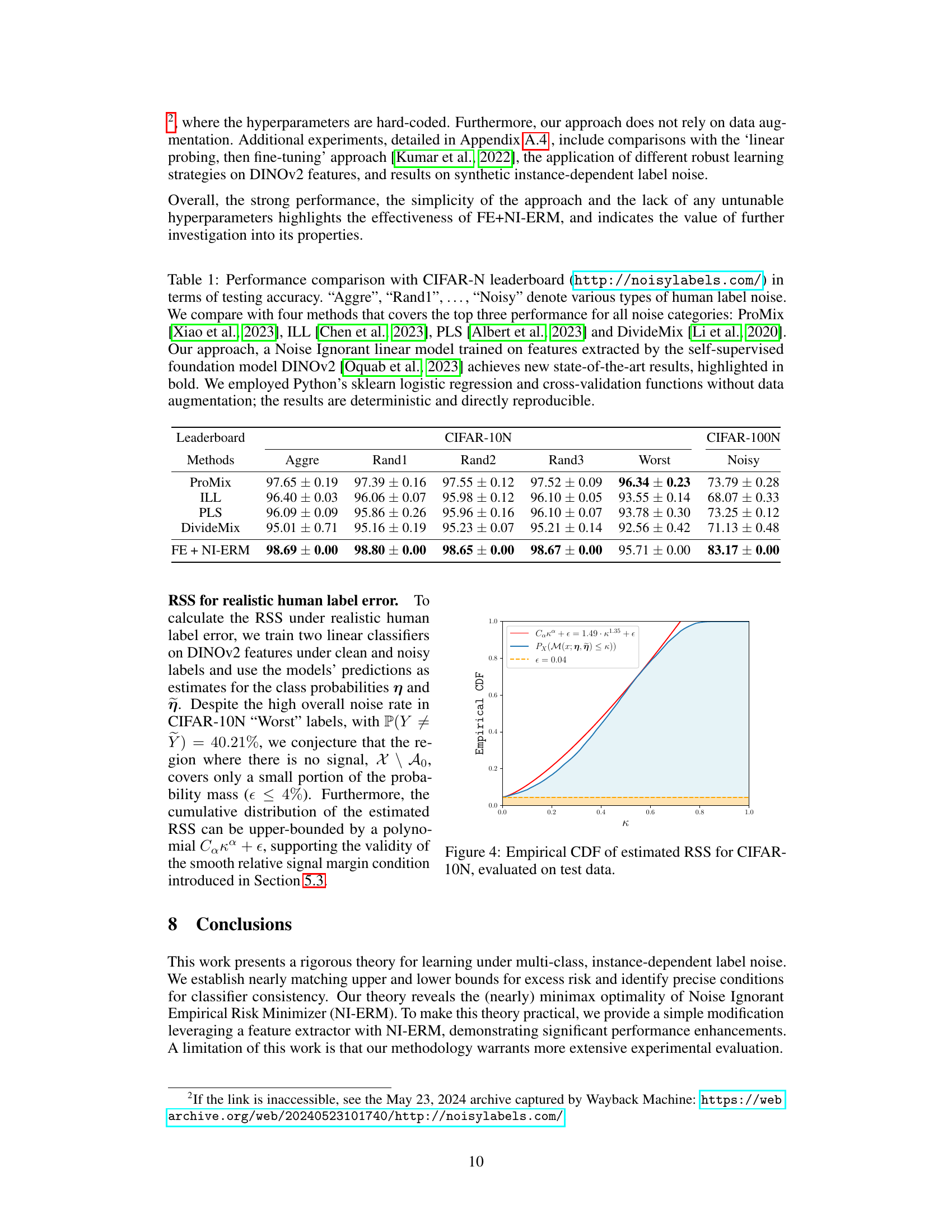

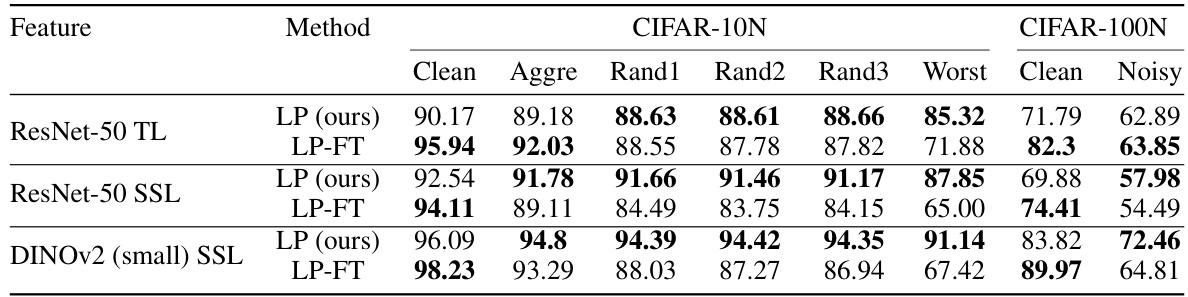

🔼 This table compares the performance of different methods on the CIFAR-N noisy label dataset. It shows the testing accuracy of several state-of-the-art methods on different types of human-labeled noise. The proposed method, FE+NI-ERM, achieves state-of-the-art results, showcasing significant improvements over existing approaches.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison with CIFAR-N leaderboard (http://noisylabels.com/) in terms of testing accuracy. “Aggre”, “Rand1”, . . . , “Noisy” denote various types of human label noise. We compare with four methods that covers the top three performance for all noise categories: ProMix [Xiao et al., 2023], ILL [Chen et al., 2023], PLS [Albert et al., 2023] and DivideMix [Li et al., 2020]. Our approach, a Noise Ignorant linear model trained on features extracted by the self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] achieves new state-of-the-art results, highlighted in bold. We employed Python’s sklearn logistic regression and cross-validation functions without data augmentation; the results are deterministic and directly reproducible.

In-depth insights#

Noise-Ignorant ERM#

The core concept of “Noise-Ignorant ERM” centers on the surprising finding that simply ignoring label noise during empirical risk minimization (ERM) can be surprisingly effective, and even near-optimal under certain conditions. This challenges the conventional wisdom that necessitates complex noise-handling mechanisms. The theoretical framework supporting this approach uses the notion of ‘Relative Signal Strength’ (RSS) to quantify the reliability of noisy labels relative to clean ones. High RSS indicates a strong signal despite noise, allowing NI-ERM to succeed. Conversely, low RSS regions pose fundamental limits to accurate learning. The key is that NI-ERM effectively leverages regions of high RSS while being robust to regions of low RSS, highlighting the importance of considering data characteristics when designing robust learning methods. This insight translates into a practical two-step approach involving feature extraction from clean data followed by NI-ERM training of a simpler classifier. Empirically, this strategy achieves state-of-the-art results, demonstrating the efficacy of the NI-ERM principle.

Relative Signal Strength#

The concept of “Relative Signal Strength” (RSS) offers a novel perspective on understanding and addressing the challenges of multi-class instance-dependent label noise in classification. RSS quantifies the transferability of information from noisy to clean posterior distributions, acting as a pointwise measure of the reliability of noisy labels. By establishing a connection between RSS and the excess risk, the authors demonstrate that high RSS regions enable consistent learning, even with significant label noise, while low RSS regions present inherent learning limitations. This framework provides a theoretical basis for the efficacy of Noise-Ignorant Empirical Risk Minimization (NI-ERM), suggesting that ignoring label noise can be nearly optimal under certain conditions. The utility of RSS lies in its ability to pinpoint data points where noisy labels are most problematic, enabling the design of algorithms that prioritize learning from reliable regions. The concept also facilitates a deeper understanding of the underlying tradeoffs between noise robustness and the level of certainty in predictions.

Minimax Bounds#

Minimax bounds in machine learning establish the optimal performance achievable under specific conditions, particularly in the presence of uncertainty or noise. They provide both upper and lower bounds on the expected risk, representing the best and worst-case scenarios, respectively. In the context of label noise, minimax bounds help characterize how much excess risk is unavoidable, given inherent ambiguity in the training data. The lower bound signifies the irreducible error, indicating that no algorithm can perform better, irrespective of its complexity, due to the limitations imposed by the noisy labels. The upper bound quantifies the best achievable performance given the noise level and problem structure, showcasing the potential for successful learning, even in challenging situations. These bounds provide a crucial theoretical benchmark, allowing researchers to assess the efficiency and optimality of different learning algorithms, and understand the inherent limitations of learning under label noise.

Feature Extraction#

The concept of feature extraction within the context of handling label noise in classification is crucial. The core idea is to separate the process of feature learning from the task of classification. By utilizing a pre-trained model or a self-supervised learning method, features are extracted from the data before any classifier is trained, effectively isolating the feature learning from the effects of noisy labels. This decoupling significantly mitigates overfitting that commonly arises when directly training a model on noisy data. The effectiveness of feature extraction depends on the quality of features learned: strong, discriminative features can ensure good performance even with noisy labels, which aligns with the principle of the paper which advocates a noise-ignorant approach in the final classification stage. Different feature extraction methods present various trade-offs. Transfer learning offers pre-trained features with potential for excellent performance but requires a suitable base model. Self-supervised learning learns features directly from the data and can adapt better to specific noise characteristics but might require substantial computational effort. The optimal choice hinges on the characteristics of the dataset and the available resources, emphasizing the flexible and adaptable nature of this strategy.

Noise Immunity#

The concept of “Noise Immunity” in the context of the provided research paper centers on the remarkable ability of a simple, noise-ignorant learning algorithm to achieve surprisingly high accuracy even when presented with heavily corrupted training labels. This phenomenon, contrary to conventional wisdom, challenges the assumption that noise correction is always necessary for effective learning in noisy environments. The paper theoretically establishes sufficient conditions for this immunity to hold, essentially proving that under certain distributional assumptions about the noise process, the optimal classifier remains unchanged despite label corruption. This immunity is not just a theoretical curiosity; it offers a practically efficient and robust approach to classification tasks with noisy labels, highlighting the potential benefits of simplicity and the surprisingly high information content even in highly noisy data. Further research is warranted to further explore the bounds of this immunity and how to leverage it for real-world applications.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure illustrates the concept of relative signal strength (RSS) in binary classification. The left panel shows the clean and noisy class posterior probabilities as a function of the input feature x. The right panel displays the corresponding RSS values. The gray region represents the area where clean and noisy Bayes classifiers differ (zero RSS), while the red region highlights where RSS exceeds 0.4.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of relative signal strength for binary classification. Left: clean and noisy posteriors [η(x)]₁ = P (Y = 1|X = x) and [ῆ(x)]₁ = P(Ỹ = 1|X = x). Right: relative signal strength corresponding to these posteriors. The gray region, x ∈ (0,5), is where the true and noisy Bayes classifiers differ, and is also the zero signal region X \ A₀. The red region is A₀.₄, where the RSS is > 0.4. Note that as x ↑ 0, Μ(x; η, ῆ) ↑ ∞, which occurs since [η(x)]₁ ↑ 1/2, while [ῆ]₁ is far from 1/2. For x → 0+, the predicted labels under η and ῆ disagree, and the RSS crashes to 0.

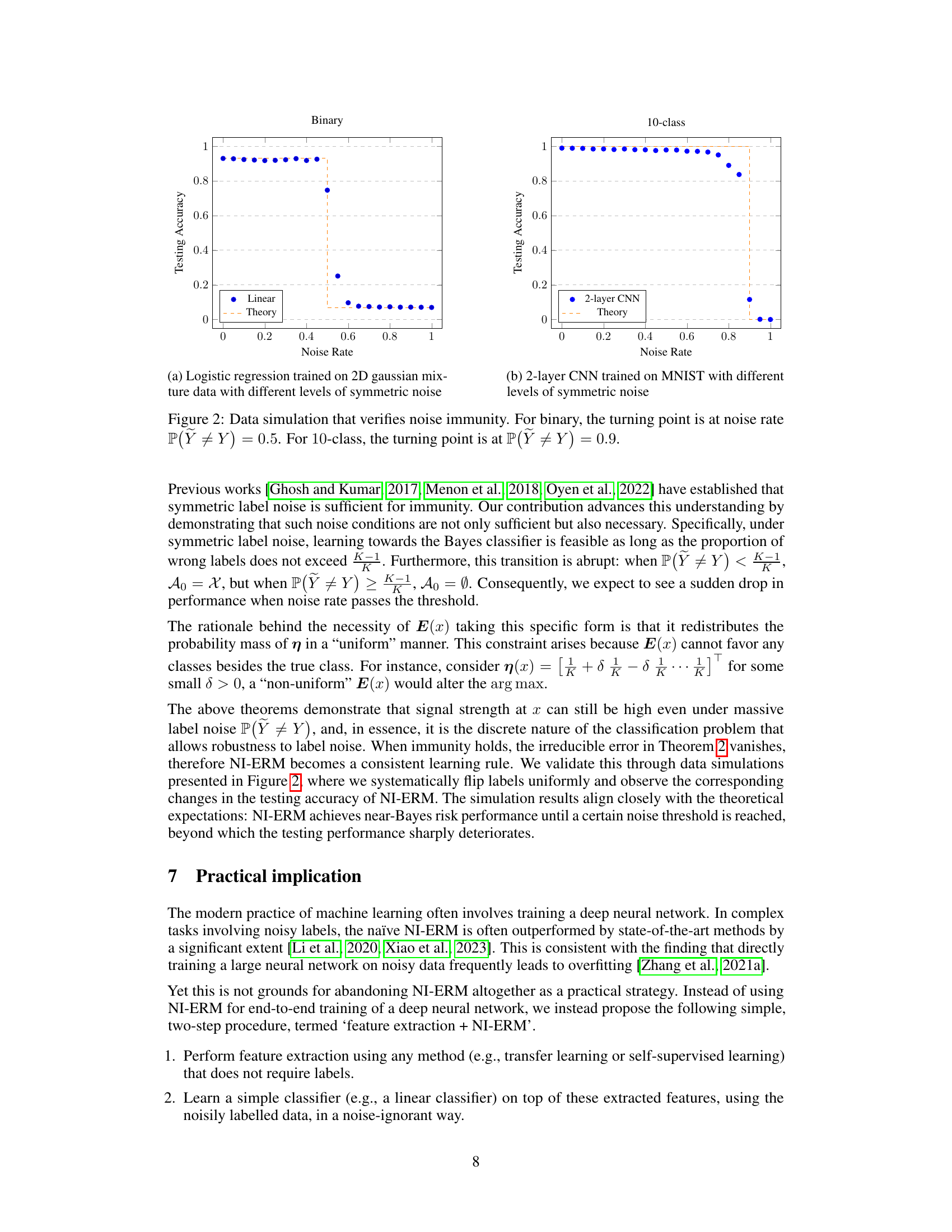

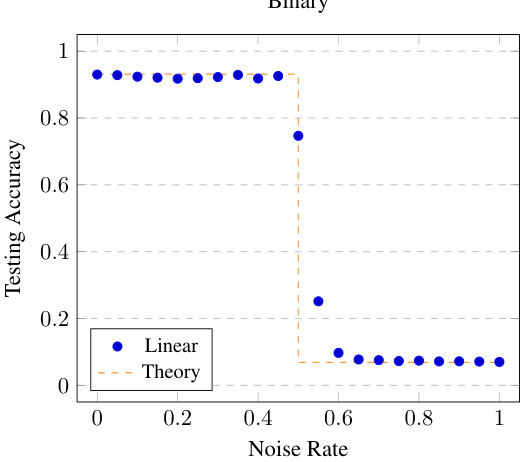

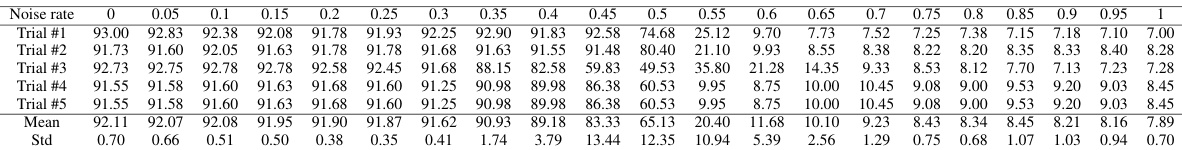

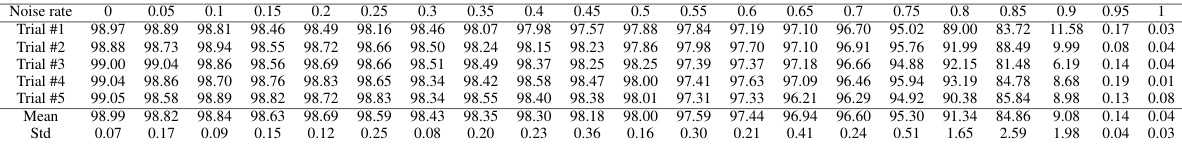

🔼 This figure shows the results of data simulations to verify the theoretical concept of noise immunity. Two experiments are conducted: one with binary classification and another with 10-class classification, both using symmetric label noise. The x-axis represents the noise rate, which is the probability that the noisy label Ỹ is different from the true label Y. The y-axis represents the testing accuracy. The results show a sharp drop in accuracy when the noise rate exceeds a threshold (0.5 for binary and 0.9 for 10-class), confirming the theoretical prediction of noise immunity.

read the caption

Figure 2: Data simulation that verifies noise immunity. For binary, the turning point is at noise rate P(Ỹ ≠ Y) = 0.5. For 10-class, the turning point is at P(Ỹ ≠ Y) = 0.9.

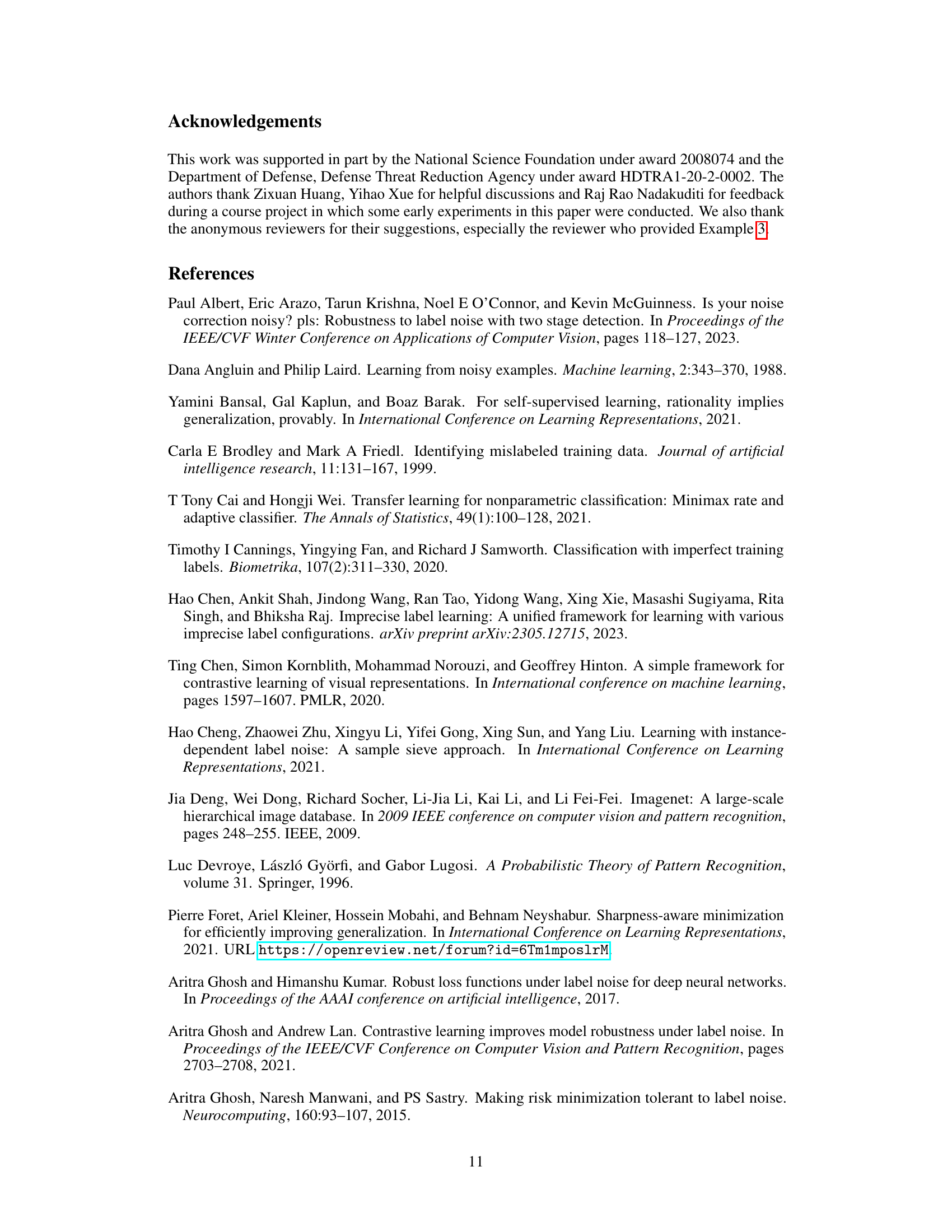

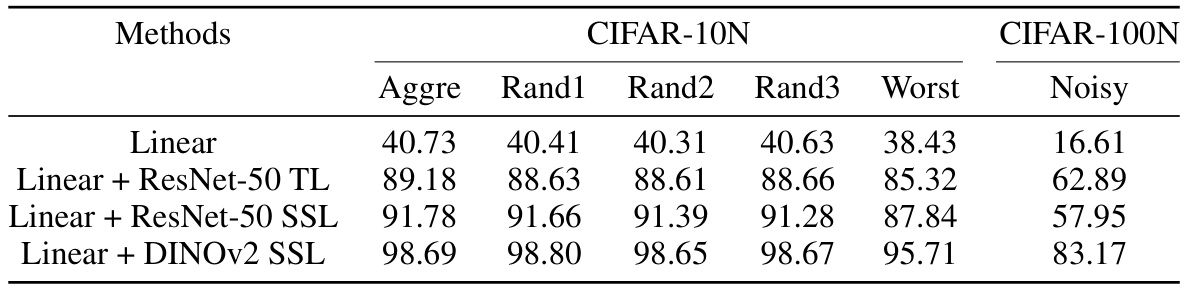

🔼 The figure shows the performance comparison of different models on CIFAR-10 with synthetic and realistic label noise. A linear model is used on top of different feature extractors, showing that using pre-trained models (transfer learning or self-supervised learning) significantly improves performance, especially with high noise levels, while training a deep network directly on noisy data leads to overfitting.

read the caption

Figure 3: A linear model trained on features obtained from either transfer learning (pretrained ResNet-50 on ImageNet [He et al., 2016]), self-supervised learning (ResNet-50 trained on CIFAR-10 images with contrastive loss [Chen et al., 2020]), or a pretrained self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] significantly boosts the performance of the original linear model. In contrast, full training of a ResNet-50 leads to overfitting.

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments conducted to evaluate the performance of different methods for learning with noisy labels on the CIFAR-10 dataset. The methods compared include using a linear model trained on top of features extracted by transfer learning, self-supervised learning, and a pretrained self-supervised model (DINOv2). The figure highlights that using a linear classifier on top of pre-trained feature extractors leads to significantly improved robustness to noisy labels compared to training a ResNet-50 end-to-end.

read the caption

Figure 3: A linear model trained on features obtained from either transfer learning (pretrained ResNet-50 on ImageNet [He et al., 2016]), self-supervised learning (ResNet-50 trained on CIFAR-10 images with contrastive loss [Chen et al., 2020]), or a pretrained self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] significantly boosts the performance of the original linear model. In contrast, full training of a ResNet-50 leads to overfitting.

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of relative signal strength (RSS) in binary classification. The left panel shows the clean and noisy class posterior probabilities, P(Y=1|X=x) and P(Ỹ=1|X=x) respectively, as functions of the feature x. The right panel plots the RSS, which quantifies the difference between the clean and noisy posteriors. The gray region highlights where the clean and noisy Bayes classifiers disagree (zero RSS), while the red region shows where the RSS exceeds 0.4. The figure demonstrates how the RSS can be infinite when the clean posterior is close to 0.5 but the noisy posterior is far from 0.5, and how the RSS drops to zero when the Bayes classifiers disagree.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of relative signal strength for binary classification. Left: clean and noisy posteriors [n(x)]₁ = P (Y = 1|X = x) and [ῆ(x)]₁ = P(Ỹ = 1|X = x). Right: relative signal strength corresponding to these posteriors. The gray region, x ∈ (0,5), is where the true and noisy Bayes classifiers differ, and is also the zero signal region X \ A₀. The red region is A₀.₄, where the RSS is > 0.4. Note that as x ↑ 0, M(x; η, ῆ) ↑ ∞, which occurs since [n(x)]₁ ↑ 1/2, while [ῆ]₁ is far from 1/2. For x → 0+, the predicted labels under η and ῆ disagree, and the RSS crashes to 0.

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of relative signal strength (RSS) in binary classification. The left panel shows the clean and noisy class posterior probabilities (P(Y=1|X=x) and P(Ỹ=1|X=x) respectively) as functions of the feature x. The right panel plots the corresponding RSS values. The gray region highlights where the clean and noisy Bayes classifiers disagree (zero RSS), while the red region shows where the RSS is above 0.4. The figure demonstrates how RSS quantifies the amount of signal (information about the true label) present in the noisy label, relative to the clean label.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of relative signal strength for binary classification. Left: clean and noisy posteriors [n(x)]₁ = P (Y = 1|X = x) and [ῆ(x)]₁ = P(Y = 1|X = x). Right: relative signal strength corresponding to these posteriors. The gray region, x ∈ (0,5), is where the true and noisy Bayes classifiers differ, and is also the zero signal region X \ A₀. The red region is A₀.₄, where the RSS is > 0.4. Note that as x ↑ 0, M(x; η, ῆ) ↑ ∞, which occurs since [η(x)]₁ ↑ 1/2, while [ῆ]₁ is far from 1/2. For x → 0+, the predicted labels under η and ῆ disagree, and the RSS crashes to 0.

More on tables

🔼 This table compares the performance of different methods on the CIFAR-N dataset. It shows the testing accuracy of various methods on different types of human label noise, including the proposed method. The proposed method is a Noise Ignorant linear model trained on DINOv2 features and achieves state-of-the-art results.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison with CIFAR-N leaderboard (http://noisylabels.com/) in terms of testing accuracy. 'Aggre', 'Rand1', ..., 'Noisy' denote various types of human label noise. We compare with four methods that covers the top three performance for all noise categories: ProMix [Xiao et al., 2023], ILL [Chen et al., 2023], PLS [Albert et al., 2023] and DivideMix [Li et al., 2020]. Our approach, a Noise Ignorant linear model trained on features extracted by the self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] achieves new state-of-the-art results, highlighted in bold. We employed Python's sklearn logistic regression and cross-validation functions without data augmentation; the results are deterministic and directly reproducible.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed method (FE+NI-ERM) with other state-of-the-art methods on the CIFAR-N dataset. It shows the test accuracy for different noise types and highlights the superior performance of the proposed method. Note that the results are deterministic and reproducible.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison with CIFAR-N leaderboard (http://noisylabels.com/) in terms of testing accuracy. 'Aggre', 'Rand1', ..., 'Noisy' denote various types of human label noise. We compare with four methods that covers the top three performance for all noise categories: ProMix [Xiao et al., 2023], ILL [Chen et al., 2023], PLS [Albert et al., 2023] and DivideMix [Li et al., 2020]. Our approach, a Noise Ignorant linear model trained on features extracted by the self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] achieves new state-of-the-art results, highlighted in bold. We employed Python's sklearn logistic regression and cross-validation functions without data augmentation; the results are deterministic and directly reproducible.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different methods on the CIFAR-N dataset, focusing on testing accuracy. It includes various types of human label noise and compares the proposed method (Noise Ignorant linear model using DINOv2 features) with four state-of-the-art methods (ProMix, ILL, PLS, and DivideMix). The results show that the proposed method achieves state-of-the-art performance and are deterministic, reproducible.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison with CIFAR-N leaderboard (http://noisylabels.com/) in terms of testing accuracy. 'Aggre', 'Rand1', ..., 'Noisy' denote various types of human label noise. We compare with four methods that covers the top three performance for all noise categories: ProMix [Xiao et al., 2023], ILL [Chen et al., 2023], PLS [Albert et al., 2023] and DivideMix [Li et al., 2020]. Our approach, a Noise Ignorant linear model trained on features extracted by the self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] achieves new state-of-the-art results, highlighted in bold. We employed Python's sklearn logistic regression and cross-validation functions without data augmentation; the results are deterministic and directly reproducible.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different methods on the CIFAR-N dataset, a benchmark for noisy label classification. The methods compared include state-of-the-art techniques and the proposed FE+NI-ERM approach. The table shows the accuracy of each method on various types of human-labeled noise. The proposed method, using a Noise Ignorant linear model with DINOv2 features, achieves state-of-the-art performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison with CIFAR-N leaderboard (http://noisylabels.com/) in terms of testing accuracy. 'Aggre', 'Rand1', ..., 'Noisy' denote various types of human label noise. We compare with four methods that covers the top three performance for all noise categories: ProMix [Xiao et al., 2023], ILL [Chen et al., 2023], PLS [Albert et al., 2023] and DivideMix [Li et al., 2020]. Our approach, a Noise Ignorant linear model trained on features extracted by the self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] achieves new state-of-the-art results, highlighted in bold. We employed Python's sklearn logistic regression and cross-validation functions without data augmentation; the results are deterministic and directly reproducible.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different methods on the CIFAR-N dataset, including the proposed approach. The results are presented as testing accuracy under various types of human-generated label noise. The proposed method (FE+NI-ERM using DINOv2 features) achieves state-of-the-art results.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison with CIFAR-N leaderboard (http://noisylabels.com/) in terms of testing accuracy. 'Aggre', 'Rand1', ..., 'Noisy' denote various types of human label noise. We compare with four methods that covers the top three performance for all noise categories: ProMix [Xiao et al., 2023], ILL [Chen et al., 2023], PLS [Albert et al., 2023] and DivideMix [Li et al., 2020]. Our approach, a Noise Ignorant linear model trained on features extracted by the self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] achieves new state-of-the-art results, highlighted in bold. We employed Python's sklearn logistic regression and cross-validation functions without data augmentation; the results are deterministic and directly reproducible.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different methods on the CIFAR-N dataset which is a benchmark for noisy label problems. The methods are compared in terms of testing accuracy for different types of human-generated label noise. The proposed method (FE+NI-ERM) achieves state-of-the-art results by using a noise-ignorant linear model trained on features extracted by DINOv2, a self-supervised foundation model. The results are deterministic due to not using data augmentation.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparison with CIFAR-N leaderboard (http://noisylabels.com/) in terms of testing accuracy. 'Aggre', 'Rand1', ..., 'Noisy' denote various types of human label noise. We compare with four methods that covers the top three performance for all noise categories: ProMix [Xiao et al., 2023], ILL [Chen et al., 2023], PLS [Albert et al., 2023] and DivideMix [Li et al., 2020]. Our approach, a Noise Ignorant linear model trained on features extracted by the self-supervised foundation model DINOv2 [Oquab et al., 2023] achieves new state-of-the-art results, highlighted in bold. We employed Python's sklearn logistic regression and cross-validation functions without data augmentation; the results are deterministic and directly reproducible.

Full paper#