TL;DR#

Current methods for comparing language encoders often rely on evaluating them on finite datasets, which may not be comprehensive. This can lead to inaccurate assessments of true encoder similarity and fail to capture subtle but important differences in their representational power, hindering efforts to select the best encoders for downstream tasks or improve transfer learning. The common practice of comparing the outputs of two encoders on a shared finite set of inputs is also insufficient to characterize the relationships between them as functions.

This research introduces a novel theoretical framework to quantify language encoder similarity using affine homotopy. The work establishes an extended metric space on language encoders, then examines affine transformations between them as a specific form of S-homotopy. Importantly, it demonstrates that this intrinsic measure of similarity strongly correlates with extrinsic performance across various downstream NLP tasks. This novel approach provides a formal, mathematically rigorous method for comparing encoders that surpasses previous approaches, offering better insights into the underlying structure and relationships between different language encoders.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for NLP researchers because it introduces a novel framework for comparing language encoders, going beyond simple dataset comparisons. It offers theoretical guarantees and provides a more nuanced understanding of encoder similarity, which can lead to better model selection and transfer learning strategies. This is especially important given the recent proliferation of pre-trained language models and the need for efficient ways to compare them. The proposed approach could significantly impact downstream tasks and inspire more robust, higher performing NLP systems.

Visual Insights#

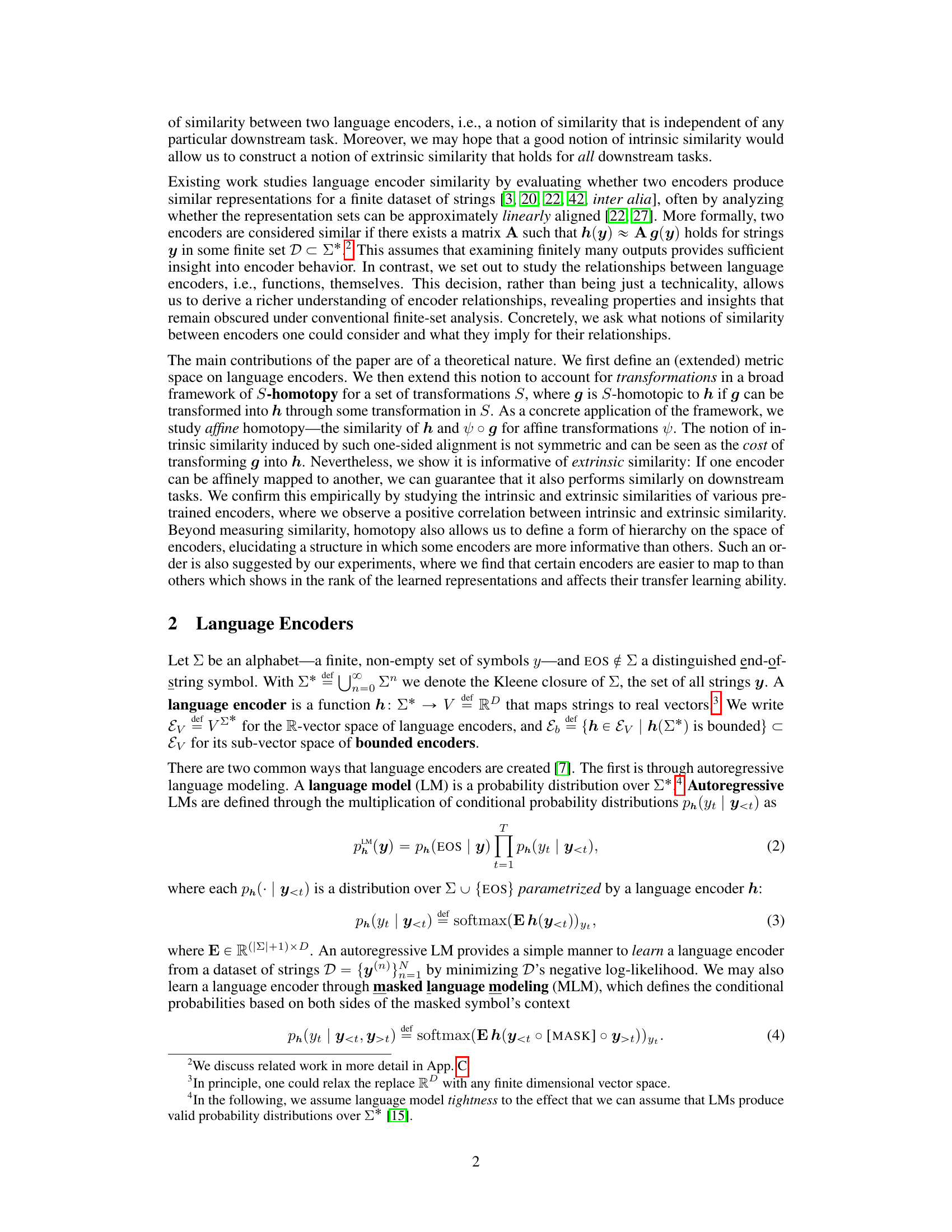

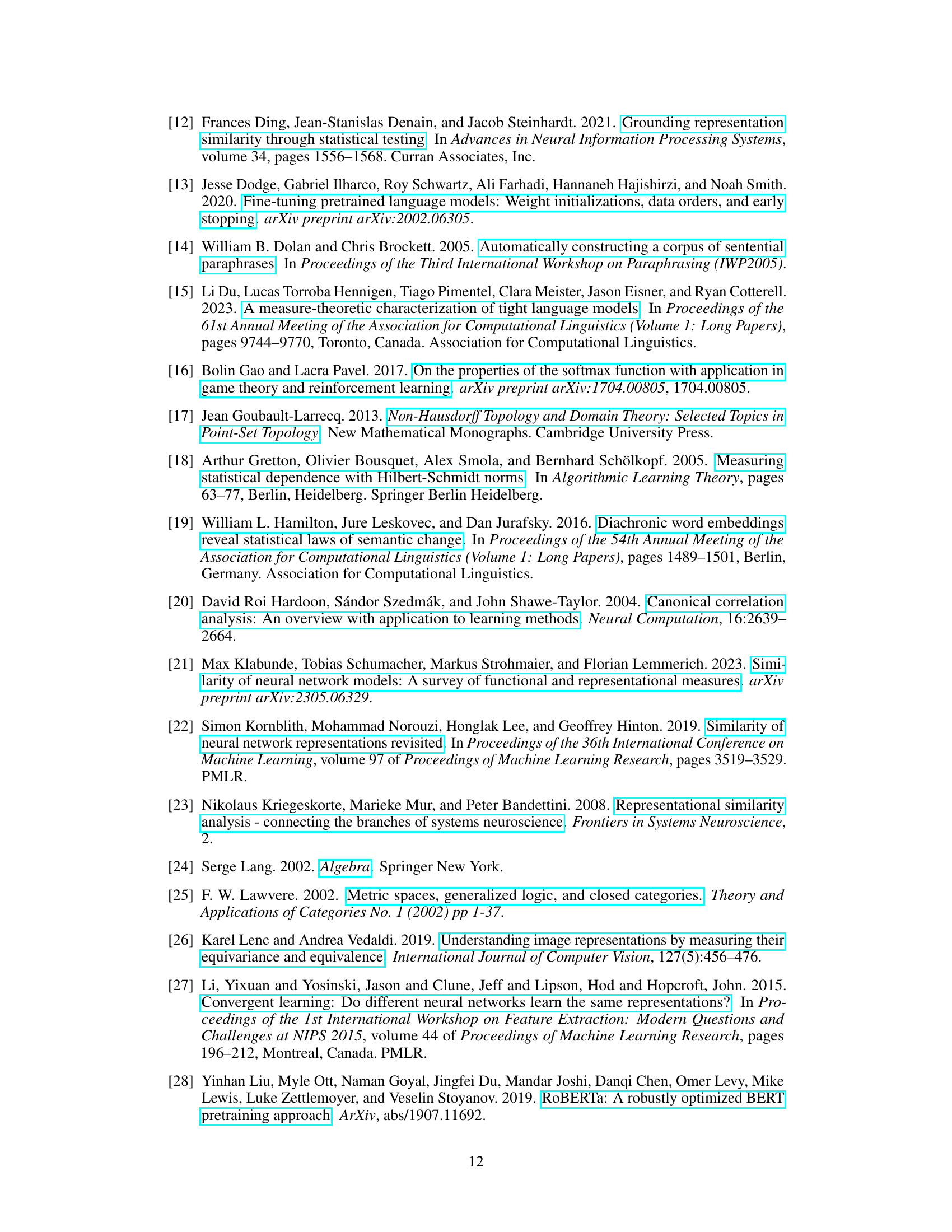

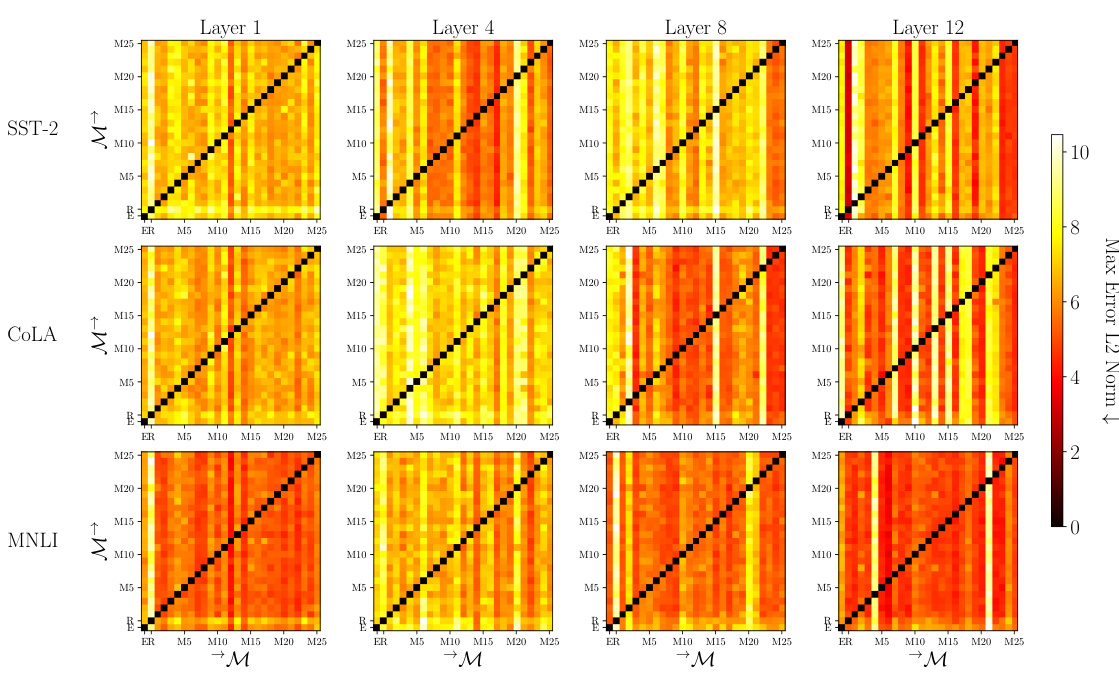

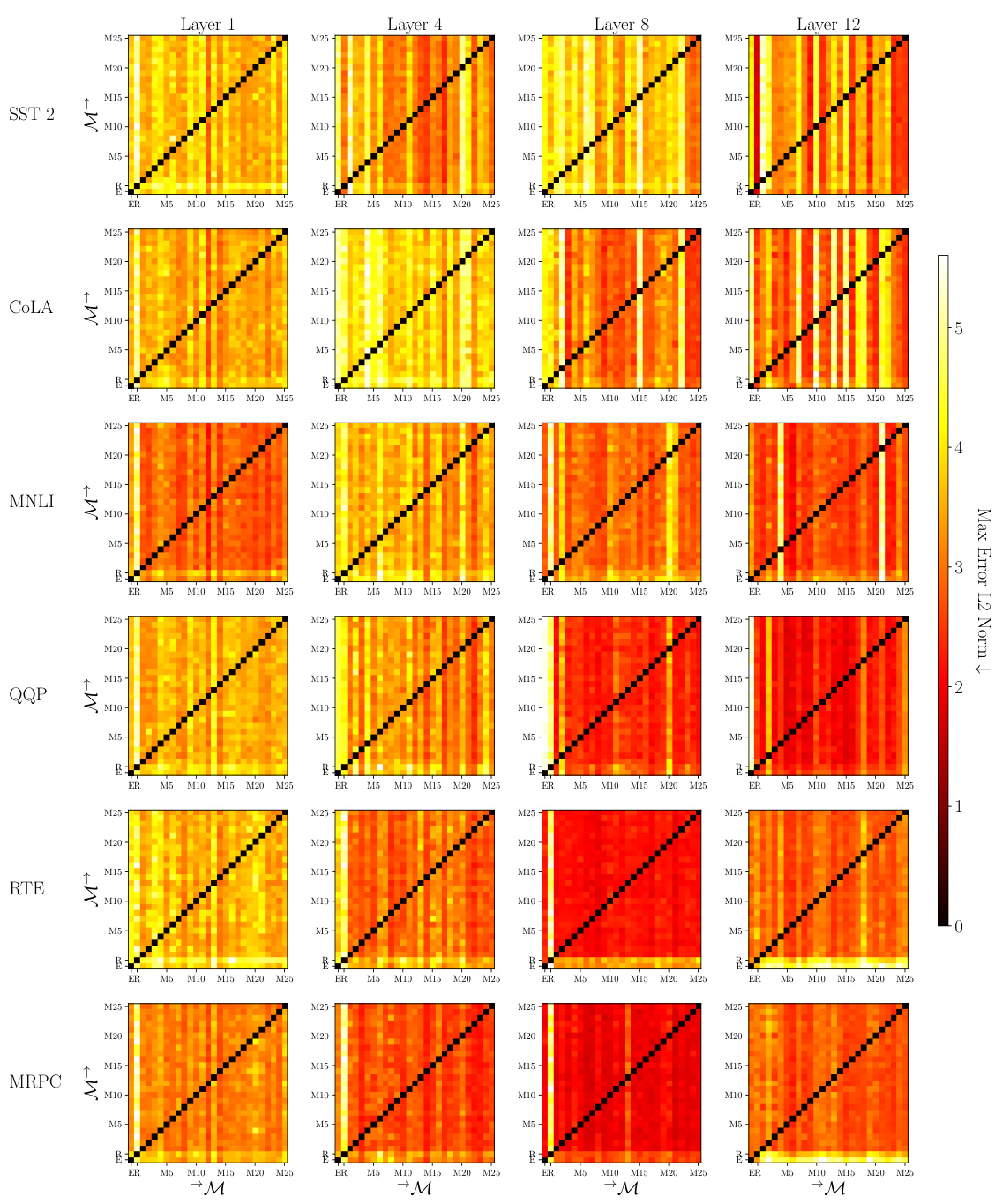

🔼 This figure visualizes the asymmetry in affine mappability between different language encoders (ELECTRA, RoBERTa, and MULTIBERT). It shows the maximum L2 norm error when fitting one encoder’s representations to another using an affine transformation. The results are shown as heatmaps for three different downstream tasks (SST-2, COLA, MNLI) and across different layers of the encoders. Darker colors indicate better fits.

read the caption

Figure 1: Asymmetry between ELECTRA (E), RoBERTa (R), and MULTIBERT encoders (M1-M25) across layers. For each pair of the encoders M(i) and M(j), we generate training set embeddings H(i), H(j) ∈ RN×D for SST-2, COLA, and MNLI. We then fit H(i) to H(j) with an affine map and report the goodness of fit through the max error L2 norm, i.e., an approximation of d(H(i), H(j)) on row i and column j of the grid. Full results across GLUE tasks are shown in Figure 4.

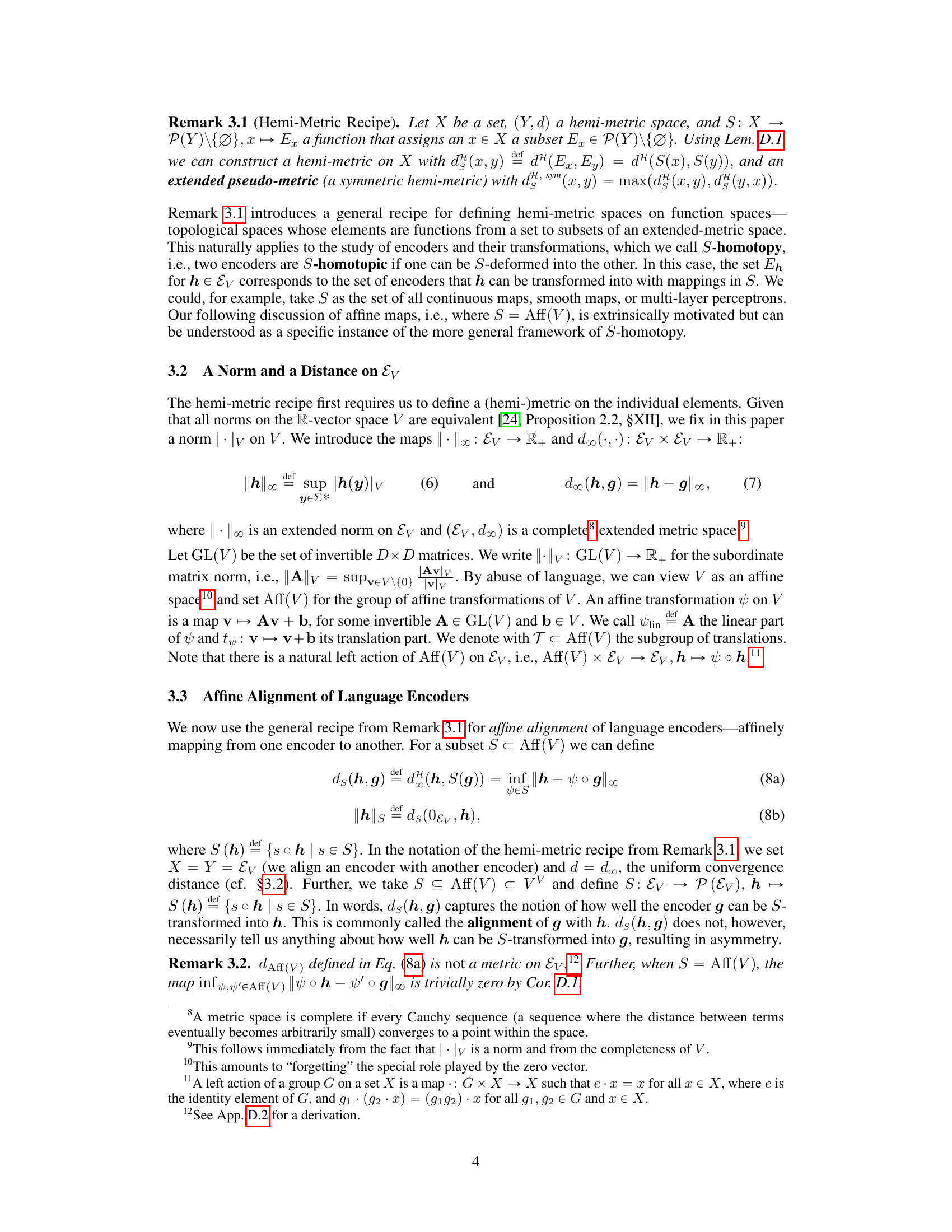

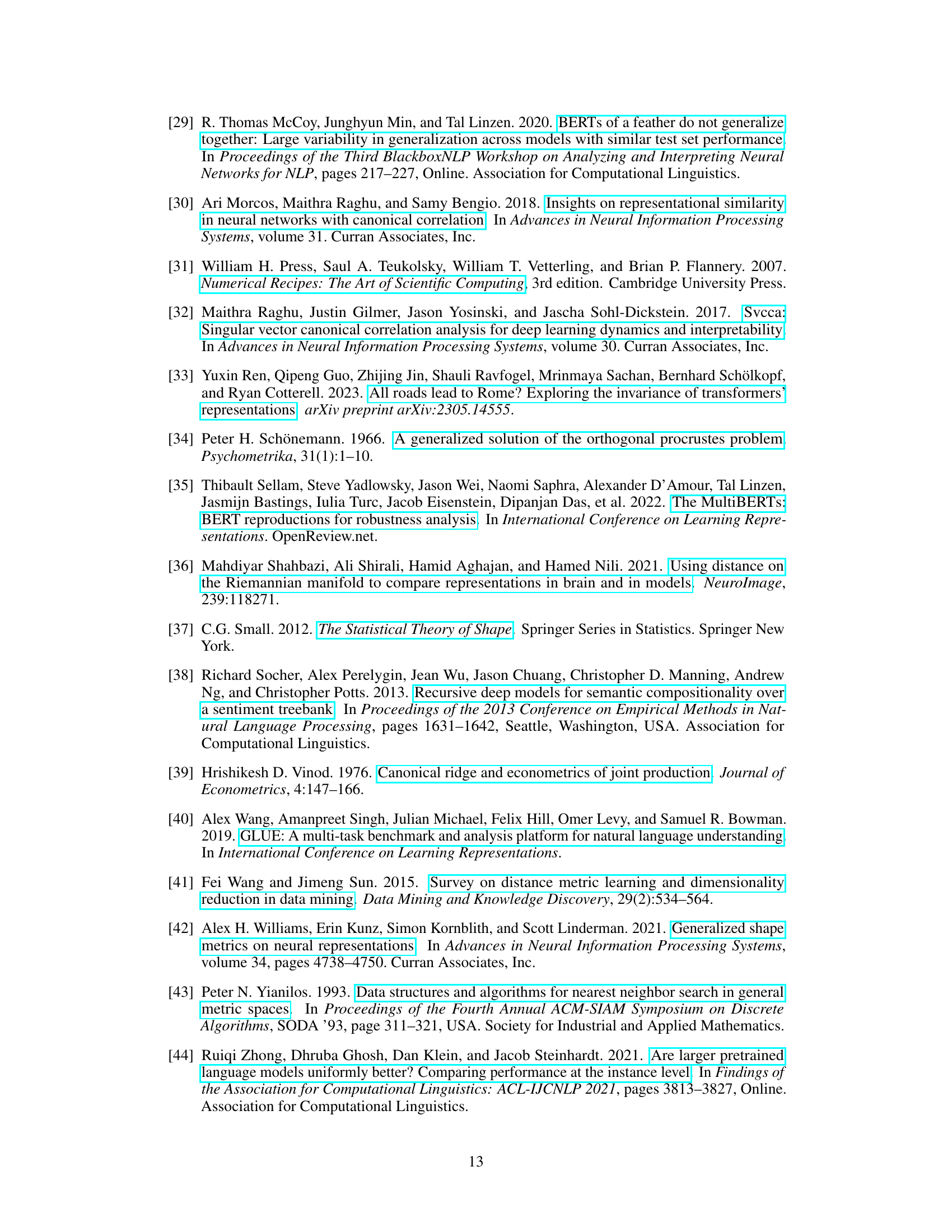

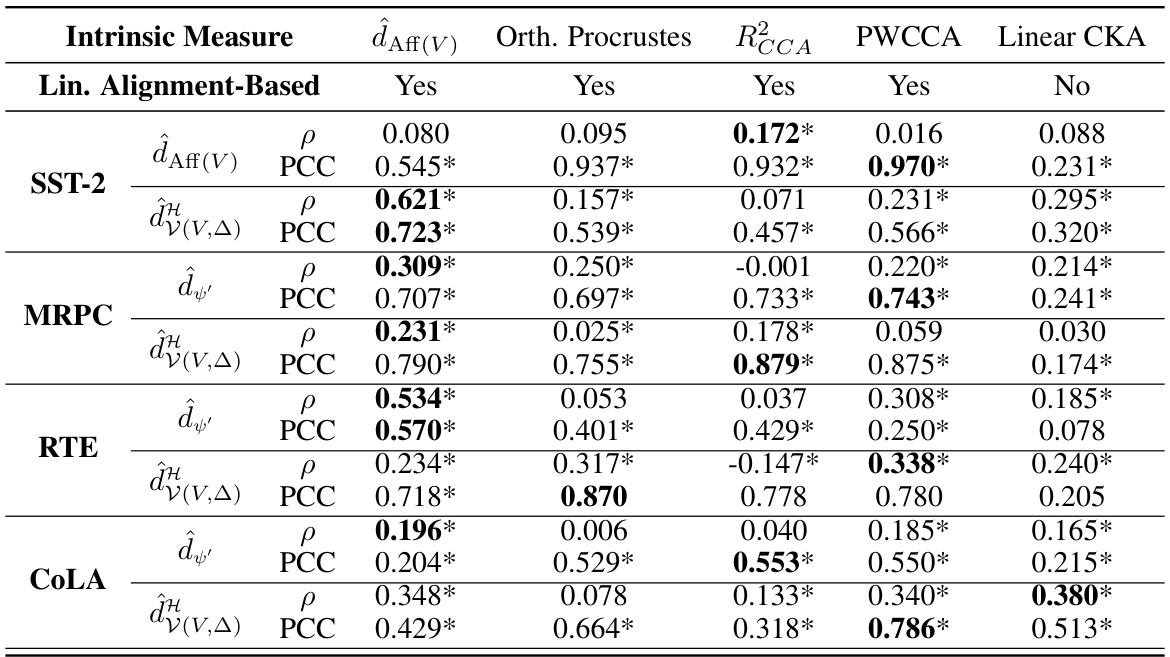

🔼 This table shows the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) between different intrinsic measures and extrinsic similarities across various GLUE datasets. The intrinsic measures are based on methods to quantify similarity of language encoders as functions: dAff(V), Orthogonal Procrustes, RCCA, PWCCA, and Linear CKA. The extrinsic similarities are based on performance on downstream tasks: d’ and d(V,△). The table helps evaluate the strength of the linear relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic similarity measures.

read the caption

Table 1: Spearman's Rank Correlation Coefficient (ρ) and Pearson's Correlation Coefficient (PCC) between intrinsic measures introduced in §6 and the extrinsic similarities d' and d(V,△) across various GLUE datasets. * indicates a p-value < 0.01 (assuming independence).

In-depth insights#

Affine Encoder Space#

The concept of an ‘Affine Encoder Space’ offers a novel perspective on analyzing and comparing language encoders. It leverages the power of affine transformations to define a structured space where encoders are not simply points but functions, capturing their inherent behavior. Affine transformations provide a means to measure the cost of converting one encoder into another, creating an intrinsic measure of similarity that is task-independent. The asymmetry in this alignment process proves significant; the ease of transforming one encoder into another does not guarantee the inverse is equally straightforward. This asymmetry allows for the definition of a partial order within the space, indicating a hierarchy of encoders in terms of their representational power and information richness. Furthermore, this framework provides valuable bounds on extrinsic similarity, correlating intrinsic alignment with downstream task performance. This approach moves beyond simple pairwise comparisons, revealing a richer structure and providing insights into the relationships among encoders and the underlying space they inhabit.

Intrinsic Similarity#

Intrinsic similarity, in the context of language encoders, seeks to measure the similarity between two encoders independently of any specific downstream task. It contrasts with extrinsic similarity, which evaluates how similar encoder outputs perform on particular tasks. A successful intrinsic similarity measure should capture fundamental structural properties of the encoders themselves, providing a task-agnostic understanding of how alike they are. This is crucial for several reasons: it facilitates a more robust comparison of different pre-trained models, identifies potential redundancies within a set of encoders, and helps explain why certain encoders perform well across a range of downstream applications. The choice of an appropriate intrinsic similarity measure is vital, as it can significantly affect the conclusions drawn about the relationships between language encoders. Different methods, such as affine alignment, offer distinct perspectives and trade-offs in quantifying intrinsic similarity, with no single approach perfectly capturing all aspects of the concept.

Affine Homotopy#

The concept of ‘Affine Homotopy’ in the context of language encoders offers a novel perspective on measuring encoder similarity. Instead of relying on task-specific performance metrics, which can be noisy and variable, affine homotopy proposes an intrinsic measure based on the geometric relationships between the encoder functions themselves. This approach involves determining how much an encoder can be transformed into another via affine transformations, effectively quantifying the cost of aligning their output spaces. This intrinsic similarity measure, while inherently asymmetric, demonstrates a correlation with extrinsic similarity, which is task-specific performance. This is a significant finding, suggesting that the proposed metric provides valuable insights into the underlying relationships between different encoders. Furthermore, the concept of affine homotopy allows for the establishment of an order among encoders, revealing a hierarchical structure in the space of pre-trained models. This hierarchical structure is informative of transfer learning capabilities, suggesting that encoders positioned higher in this order tend to perform better on downstream tasks. However, limitations include the reliance on affine transformations, which might not accurately capture complex, non-linear relationships between encoders. Despite this limitation, the framework offers a significant advance in understanding the intrinsic structure and properties of language encoder spaces.

Extrinsic Alignment#

Extrinsic alignment, in the context of language encoders, refers to evaluating the similarity of two encoders based on their performance on downstream tasks. Unlike intrinsic alignment which focuses on inherent properties of the encoders themselves, extrinsic alignment assesses task-specific performance. This approach is crucial because a primary application of pre-trained encoders is their transferability to various NLP problems. Two encoders might exhibit similar intrinsic properties (e.g., similar vector representations for a given dataset), yet still perform differently on specific downstream tasks. Therefore, extrinsic alignment is a vital complement to intrinsic analyses, providing a more practical measure of similarity relevant to real-world applications. While assessing extrinsic similarity necessitates evaluating model performance across diverse downstream tasks, which can be computationally expensive and time consuming, it’s critical for evaluating the true utility of language encoders in practice. The choice between focusing on intrinsic or extrinsic measures depends on the research goal. For instance, research focused on the underlying architecture of language models would benefit from a strong intrinsic approach. In contrast, work oriented toward building practical NLP systems prioritizes extrinsic analysis for a more robust assessment of effectiveness.

Empirical Findings#

An empirical findings section would likely present quantitative results supporting the paper’s claims regarding affine homotopy between language encoders. Key results would demonstrate the correlation between intrinsic (task-independent) and extrinsic (task-dependent) similarity. This might involve comparing performance on downstream tasks (e.g., sentiment analysis) for pairs of encoders exhibiting varying degrees of affine alignment. Visualizations, such as heatmaps or scatter plots, could effectively illustrate the strength and consistency of this correlation across different tasks and layers of the encoders. The analysis might also explore the relationship between intrinsic similarity and encoder rank, possibly showing that encoders with similar ranks exhibit stronger correlations. The study should address limitations such as the potential for linear alignment methods to underrepresent non-linear relationships. Furthermore, the discussion should clarify whether the observed relationships are sensitive to factors like dataset size or the specific downstream tasks selected. Ideally, the section would include statistical significance testing to support all reported findings and justify any conclusions made based on the empirical evidence.

More visual insights#

More on figures

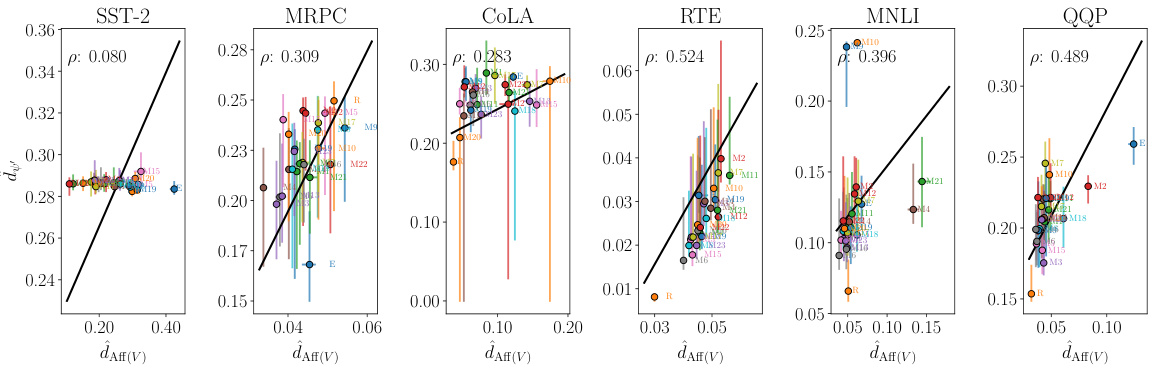

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between intrinsic and extrinsic similarity measures for different language encoders. The intrinsic similarity is measured using the affine alignment method (dAff(V)), while the extrinsic similarity (d’) is calculated based on the performance on downstream tasks. The plot shows a positive correlation between intrinsic and extrinsic similarity, suggesting that encoders that are intrinsically similar also tend to perform similarly on downstream tasks. The data points are grouped by the ‘mappability’ of the encoders, illustrating how easily an encoder can be transformed into another using affine transformations.

read the caption

Figure 2: For ELECTRA (E), RoBERTa (R), and MULTIBERTs (M1-M25), we plot extrinsic (d') against intrinsic similarity (dAff(V)) across GLUE tasks. We group the points by how well we can map to each encoder (M), and display the median, as well as the first and third quartiles as vertical and horizontal lines. We additionally show the linear regression from dAff(V) to d'.

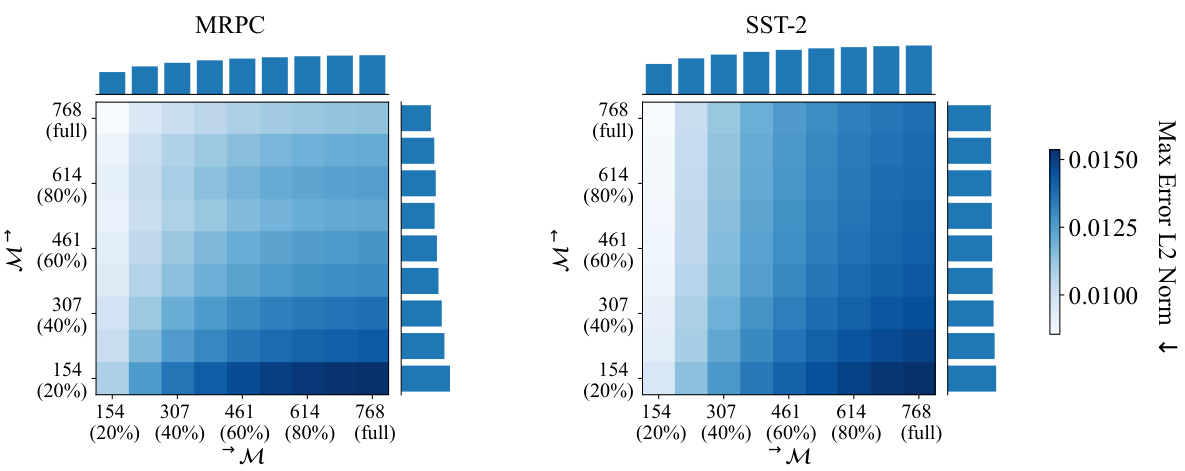

🔼 This figure shows the effect of artificial rank deficiency on the distance between MULTIBERT encoders. By using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) truncation, the authors create rank-deficient versions of the encoders and measure the distance between them. The heatmap shows that the distance is generally symmetric, and the distance between encoders of the same rank becomes easier as the rank decreases.

read the caption

Figure 3: The effect of artificial rank deficiency averaged across MULTIBERTS. For each pair of embeddings H(i) and H(j) from MULTIBERTS M(i) and M(j), we generate additional rank-deficient encoders H(i)X% and H(j)Y% with X, Y ∈ {20%, ..., 90%} of the full rank through SVD truncation. We compute d(H(i)X%, H(j)Y%) for each pair of possible rank-deficiency and finally report the median across all MULTIBERTS on row X and column Y on the grid. We additionally show row-, and column medians.

🔼 This figure visualizes the asymmetry in affine mappability between different language encoders (ELECTRA, RoBERTa, and MULTIBERT) across various layers and GLUE tasks. Each cell in the heatmap represents the error of fitting one encoder’s representation to another using an affine transformation, highlighting the directionality of the similarity measure.

read the caption

Figure 4: Asymmetry between ELECTRA (E), RoBERTa (R), and MULTIBERT encoders (M1-M25) across layers. For each pair of the encoders M(i) and M(j), we generate training set embeddings H(i), H(j) ∈ RN×D for the GLUE tasks SST-2, CoLA, MNLI, QQP, RTE, and MRPC. We then fit H(i) to H(j) with an affine map and report the goodness of fit through the max error L2 norm, i.e., an approximation of d(H(i), H(j)) on row i and column j of the grid.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient (ρ) and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (PCC) between intrinsic and extrinsic similarity measures for various GLUE datasets. The intrinsic measures are based on the methods described in section 6, while the extrinsic measures (d’ and d(V,△)) are defined in section 5. The p-values indicate statistical significance, with * denoting p < 0.01, suggesting a strong correlation between the intrinsic and extrinsic measures for many of the datasets.

read the caption

Table 1: Spearman’s Rank Correlation Coefficient (ρ) and Pearson’s Correlation Coefficient (PCC) between intrinsic measures introduced in §6 and the extrinsic similarities d’ and d(V,△) across various GLUE datasets. * indicates a p-value < 0.01 (assuming independence).

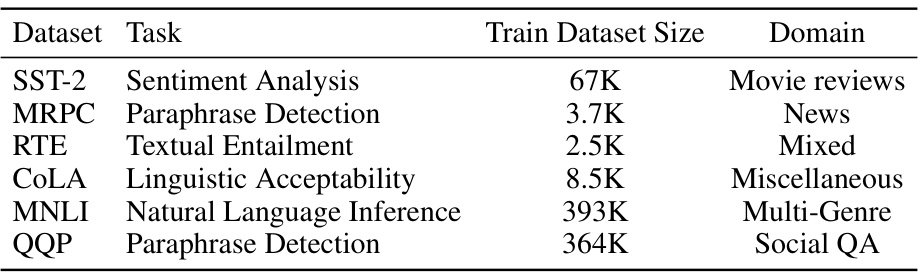

🔼 This table presents the statistics of six datasets from the GLUE benchmark used in the paper’s experiments. For each dataset, it shows the task it addresses (e.g., sentiment analysis, paraphrase detection), the size of the training dataset, and the domain the data comes from (e.g., movie reviews, news, social QA). These details are essential for understanding the scope and context of the experimental evaluation.

read the caption

Table 3: Statistics for the used GLUE benchmark [40] datasets.

Full paper#