TL;DR#

Federated learning (FL) optimizes models collaboratively across distributed clients, but existing optimizers like FedProx often struggle with slow convergence. This is particularly challenging in the ‘interpolation regime’ where models are overparameterized, a common scenario in modern machine learning. The slow convergence significantly limits the practicality and efficiency of FL, hindering its wider adoption.

This paper addresses this challenge by proposing and analyzing several server-extrapolation strategies to boost FedProx’s convergence. The researchers introduce Extrapolated FedProx (FedExProx) along with theoretically sound and adaptive extrapolation methods (FedExProx-GraDS and FedExProx-StoPS). They demonstrate that FedExProx improves upon existing methods by significantly accelerating convergence in convex and strongly convex settings, validating their findings with numerical experiments. The adaptive variants further enhance practicality by removing the need for prior knowledge of specific model parameters.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for Federated Learning (FL) researchers because it tackles the elusive problem of extrapolation, offering theoretical guarantees and practical improvements. Its focus on the interpolation regime, combined with adaptive extrapolation strategies, addresses a significant limitation of current FL optimizers, opening new avenues for enhanced convergence and efficiency.

Visual Insights#

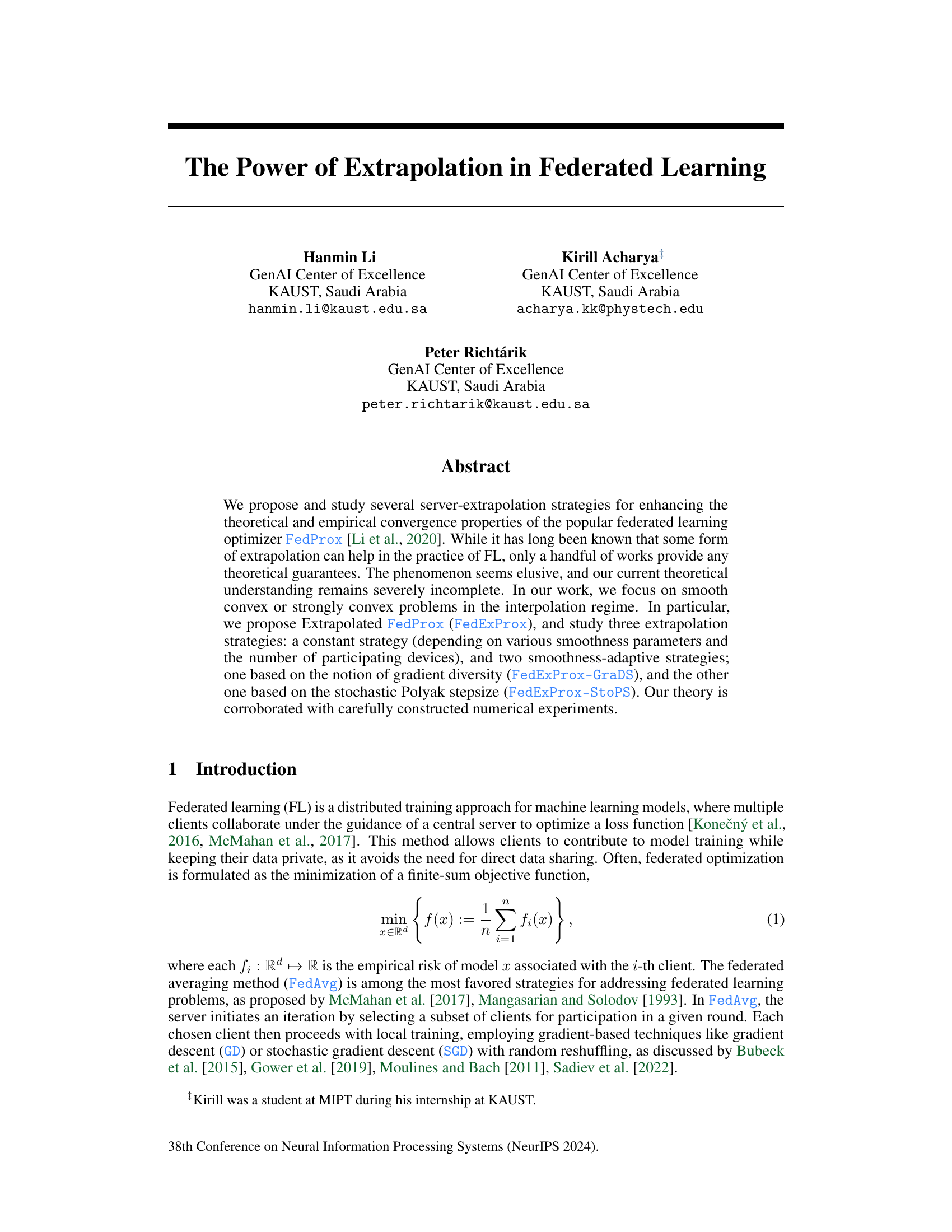

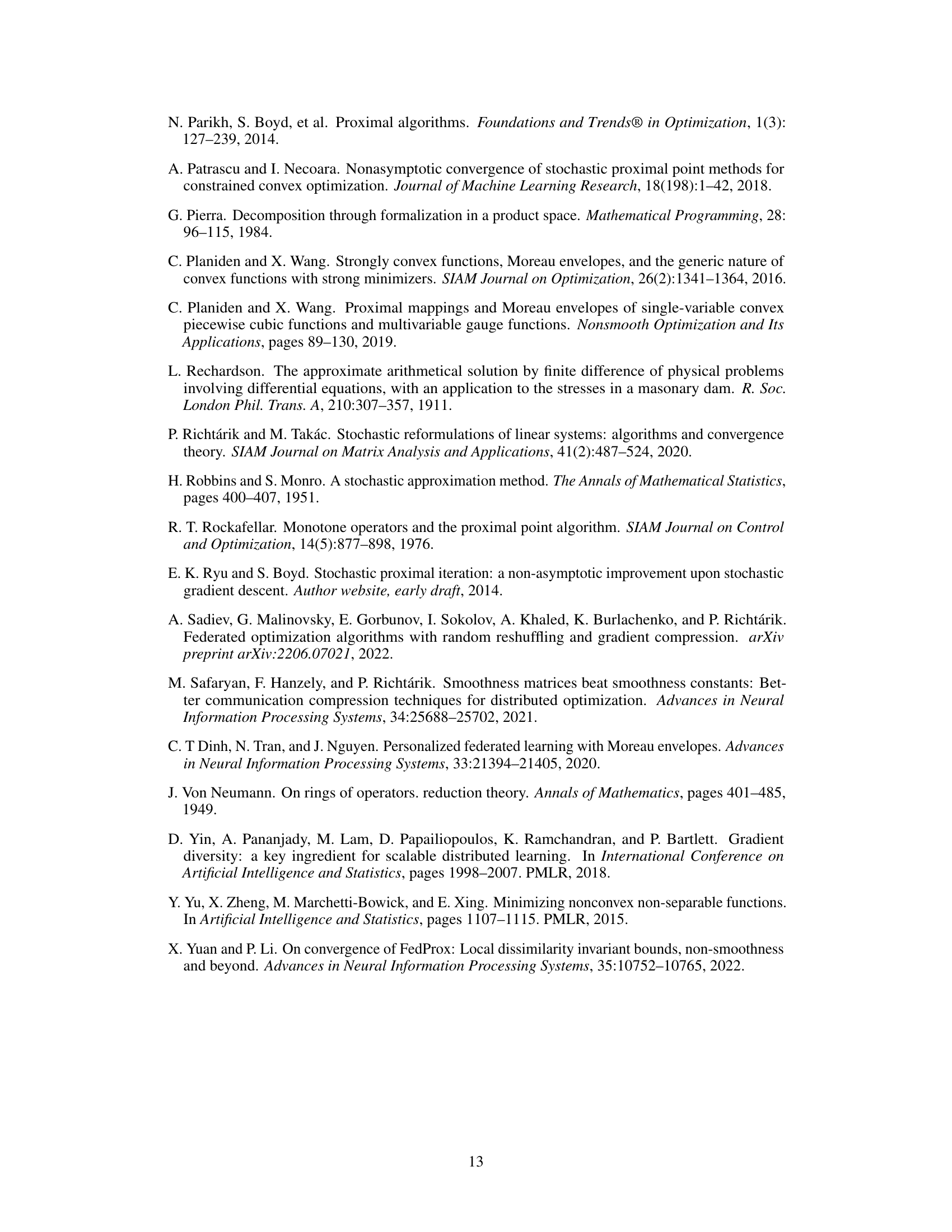

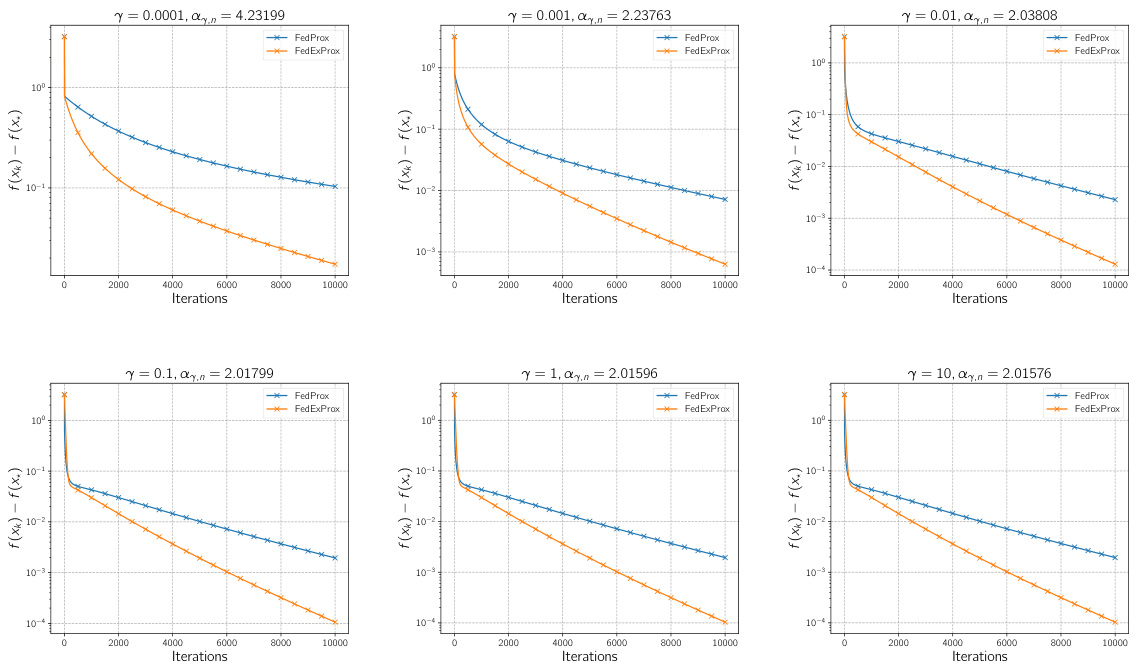

🔼 This figure compares the iteration complexity of FedExProx and FedProx for various local step sizes (γ) in the full participation setting (all clients participate in each round). FedProx is a baseline federated learning optimizer. FedExProx enhances FedProx by incorporating server-side extrapolation. The results demonstrate that FedExProx consistently outperforms FedProx across different step sizes, indicating that the server simply averaging iterates from clients is less effective compared to using extrapolation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of FedExProx and FedProx in terms of iteration complexity in the full participation setting. The notation γ here denotes the local step size of the proximity operator and αγ,n is the corresponding optimal extrapolation parameter computed in (9) in the full participation case. In all cases, our proposed algorithm outperforms FedProx, suggesting that the practice of simply averaging the iterates is suboptimal.

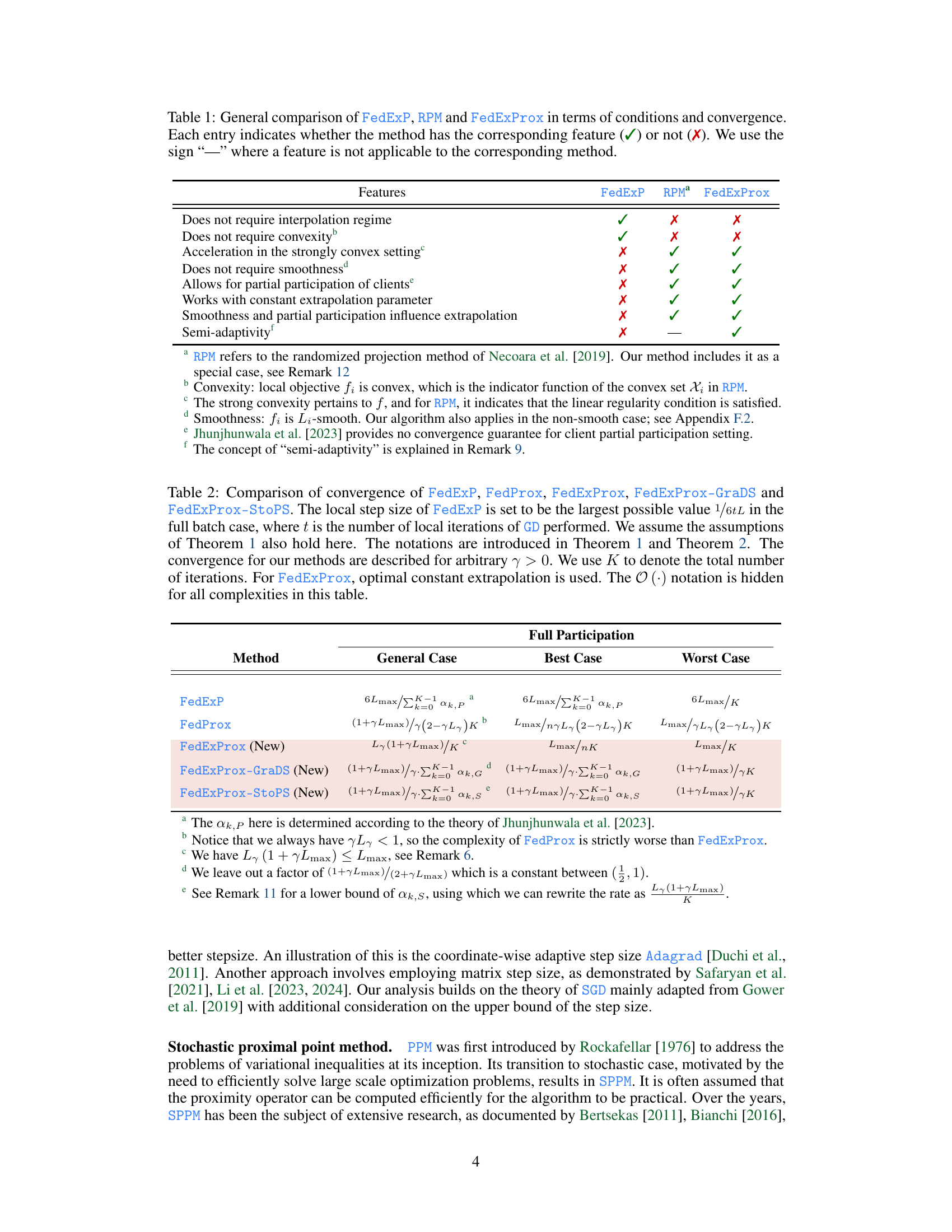

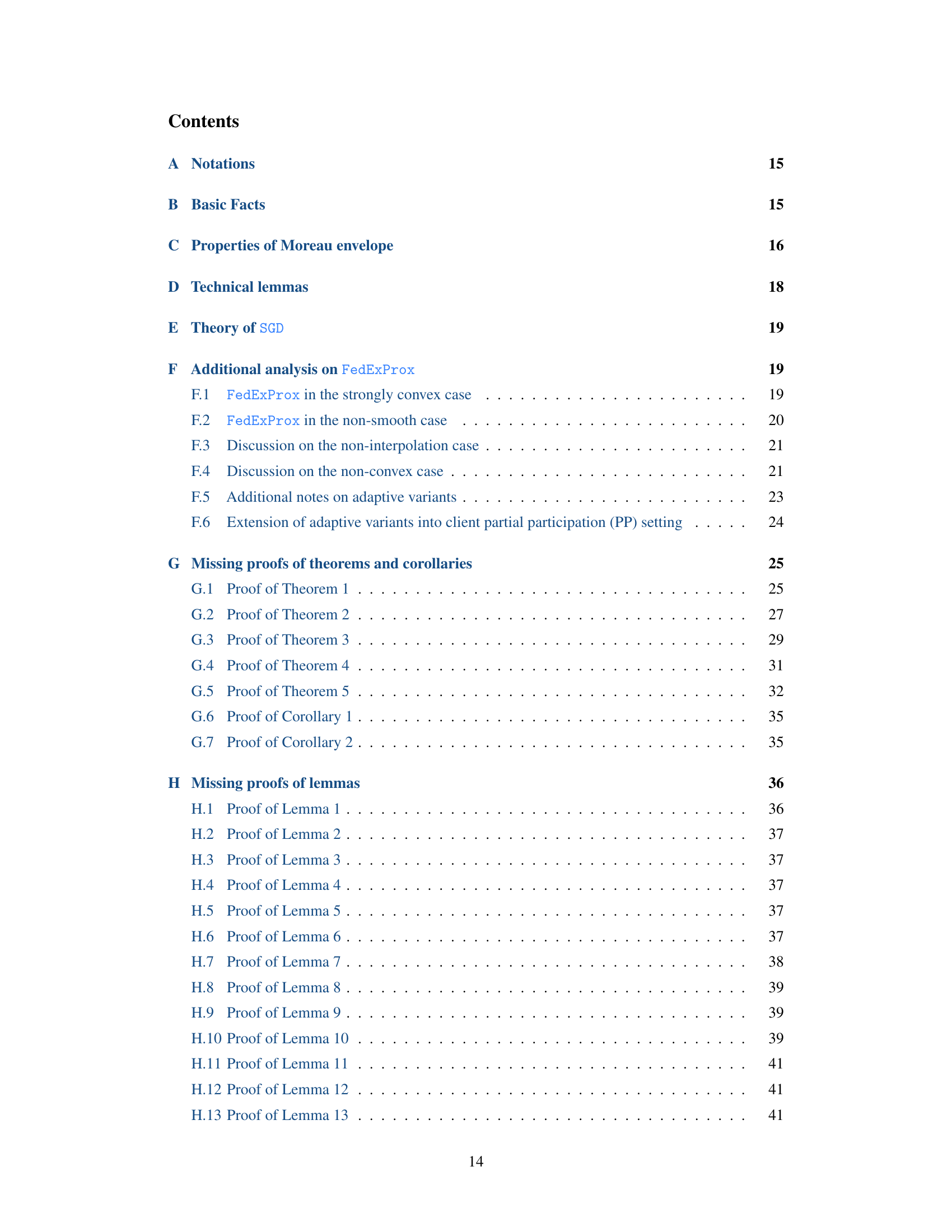

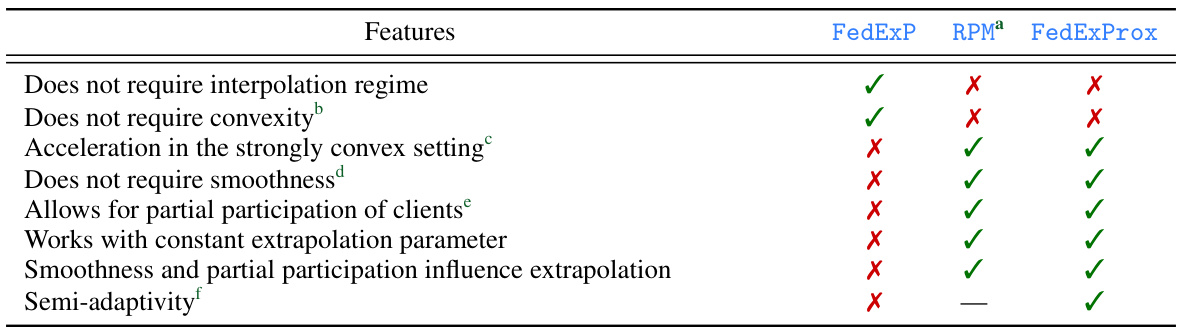

🔼 This table compares three federated learning algorithms: FedExP, RPM, and FedExProx. It highlights key differences across several features: the requirement for an interpolation regime or convexity assumptions, whether they provide acceleration in strongly convex settings, the necessity of smoothness assumptions, the ability to handle partial client participation, and whether they use a constant extrapolation parameter or adaptively determine it based on smoothness or partial participation. Finally, it notes if the algorithm exhibits ‘semi-adaptivity’, a property related to convergence.

read the caption

Table 1: General comparison of FedExP, RPM and FedExProx in terms of conditions and convergence. Each entry indicates whether the method has the corresponding feature (✔) or not (X). We use the sign '-' where a feature is not applicable to the corresponding method.

In-depth insights#

FedProx Extrapolation#

The concept of “FedProx Extrapolation” centers on enhancing the Federated Learning (FL) optimizer FedProx by incorporating extrapolation techniques. FedProx itself addresses the challenges of FL by using a proximal term to stabilize local model updates, but extrapolation aims to further accelerate convergence. The core idea is to project the server’s model update further along the direction suggested by the average of clients’ local updates. This approach leverages the intuition that, in certain settings, moving beyond the immediate average can lead to faster progress toward the optimal solution. The paper likely explores several extrapolation strategies, possibly including constant and adaptive methods. Adaptive strategies dynamically adjust the extrapolation parameter based on observed quantities such as gradient diversity or stochastic Polyak stepsize, aiming to automatically optimize the extrapolation process without requiring manual tuning. Theoretical analysis probably provides convergence rate improvements under assumptions like convexity or strong convexity of the loss function, and numerical experiments demonstrate enhanced performance over standard FedProx.

Adaptive Extrapolation#

Adaptive extrapolation techniques in federated learning aim to dynamically adjust the extrapolation parameter during the learning process, enhancing convergence speed and efficiency. Unlike static extrapolation methods that use a fixed parameter, adaptive methods leverage insights from the data and model to make informed adjustments. Gradient diversity and stochastic Polyak step size are two promising approaches for adaptive extrapolation, offering the potential to eliminate reliance on unknown smoothness constants and improve performance across various settings. These techniques demonstrate a significant advancement in federated learning, particularly in scenarios with heterogeneous data and limited communication bandwidth. Theoretical analysis and empirical results suggest that adaptive extrapolation can achieve faster convergence compared to fixed extrapolation and standard federated learning optimization methods, leading to more efficient and robust model training.

Convergence Analysis#

A rigorous convergence analysis is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness and reliability of any federated learning algorithm. The analysis should consider various factors such as communication efficiency, data heterogeneity, client participation, and algorithm design. A strong convergence analysis will provide theoretical guarantees on the algorithm’s ability to reach a solution within a certain number of iterations or communication rounds. Convergence rates, expressed as a function of problem parameters and algorithm settings, quantify the speed of convergence. It is also important to explore the effects of different extrapolation strategies on convergence behavior, considering both theoretical bounds and empirical results. The analysis must also address practical challenges like dealing with non-convex objective functions, adapting to noisy or unreliable communication environments, and handling partial client participation. Robustness to various settings and scenarios is critical to demonstrating the practical applicability and efficacy of the proposed methods. A comprehensive study would offer comparisons to existing algorithms, demonstrating clear improvements and showcasing the advantages of using server extrapolation strategies.

Numerical Experiments#

A thorough analysis of the ‘Numerical Experiments’ section would involve examining the datasets used, ensuring their relevance and appropriateness for the research questions. The experimental setup, including the metrics employed for evaluation and the methodologies used, needs to be meticulously examined. Reproducibility is key, therefore, clear descriptions of the parameters, hardware, and software are crucial for validating the results. Statistical significance testing and error analysis should be part of this evaluation, verifying the robustness of the findings. Finally, a critical examination of the presented results is crucial, analyzing whether they support the paper’s claims, along with considering any limitations or potential biases in the experimental design or data interpretation. A comparison to existing state-of-the-art approaches would establish the novelty and significance of the contributions. All these combined provide a robust and thorough evaluation of the ‘Numerical Experiments’ section.

Future Research#

The authors suggest several avenues for future work, acknowledging limitations in their current analysis. Extending the theoretical analysis and empirical results beyond the interpolation regime is a critical next step, potentially requiring new variance reduction techniques. Investigating the applicability of server-side extrapolation to non-convex problems presents another significant challenge. A particularly interesting direction lies in exploring the integration of server-side extrapolation with client-specific personalization, creating more customized models. The authors also suggest examining the use of adaptive rules, such as gradient diversity, to optimize the choice of extrapolation parameter in various settings, particularly non-convex and non-interpolated scenarios. Finally, further investigation into the practical computational efficiency of the proposed adaptive extrapolation methods, especially when considering high-dimensional settings or large client participation, would significantly enhance the work’s value.

More visual insights#

More on figures

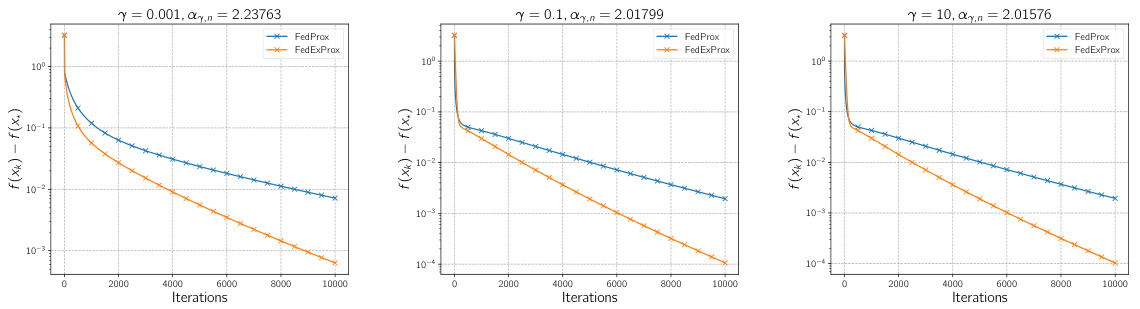

🔼 This figure compares the convergence speed of FedExProx and FedProx in the full participation setting (all clients participate in each round). The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis shows the difference between the function value at the current iteration and the minimum function value (f(xk) - f(x*)). Different plots show the results for various values of the local step size γ (ranging from 0.0001 to 10). The optimal constant extrapolation parameter αγ,n is calculated according to Theorem 1 for each γ. FedExProx consistently outperforms FedProx, indicating that extrapolation leads to faster convergence.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of convergence of FedExProx and FedProx in terms of iteration complexity in the full participation setting. For this experiment γ is picked from the set {0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, 10}, the αγ,η indicates the optimal constant extrapolation parameter as defined in Theorem 1. For each choice of γ, the two algorithms are run for K = 10000 iterations, respectively.

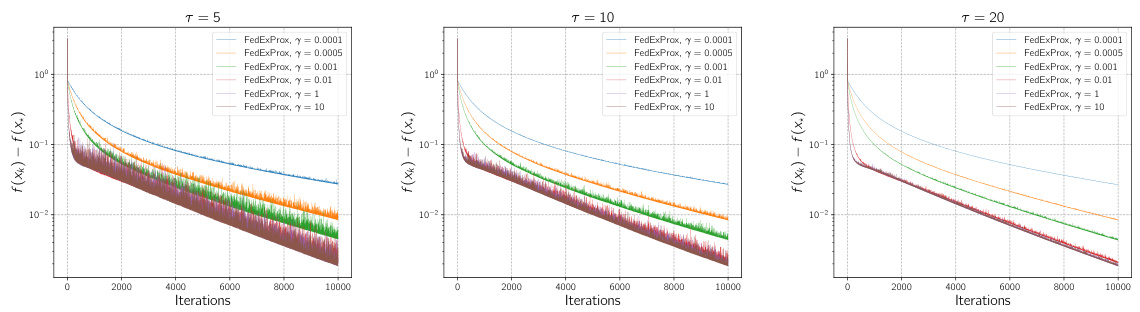

🔼 This figure compares the convergence speed of FedExProx and FedProx under partial client participation. Different local step sizes (γ) and client minibatch sizes (τ) are tested. The optimal constant extrapolation parameter (αγ,τ) from Theorem 1 is used for each combination of γ and τ. The results show FedExProx consistently outperforms FedProx across various settings, indicating that simple averaging of client updates (FedProx) is less efficient than incorporating extrapolation (FedExProx).

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of convergence of FedExProx and FedProx in terms of iteration complexity in the client partial participation setting. For this experiment γ is picked from the set {0.0001, 0.001}, the client minibatch size τ is chosen from {10, 15, 20} and the αγ,τ indicates the optimal constant extrapolation parameter as defined in Theorem 1. For each choice of γ and τ, the two algorithms are run for K = 10000 iterations, respectively.

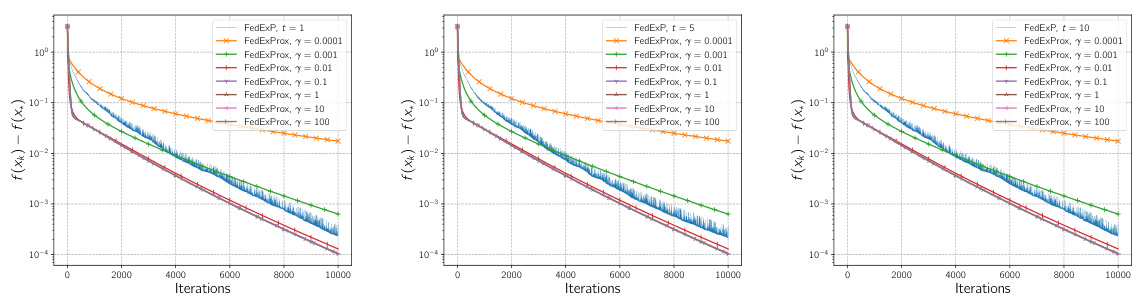

🔼 This figure compares the performance of FedExProx with different step sizes (γ) in the full participation setting. It also includes FedExP as a benchmark, using different numbers of local training iterations (t). The results show the iteration complexity (number of iterations to reach a certain level of suboptimality) for each algorithm and step size. The optimal step size for FedExP is calculated as 1/(6tLmax), where Lmax is the maximum smoothness constant across all local objective functions.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison in terms of iteration complexity for FedExProx with different step sizes γ chosen from {0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 1, 10, 100} in the full participation setting. In the figure, we use FedExP with different iterations of local training t ∈ {1, 5, 10} as a benchmark in the three sub-figures. The local step size for FedExP is set to be the largest possible value 1/(6tLmax), where Lmax = maxi∈[n] Li.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of FedExProx with different step sizes (γ) in the client partial participation setting. Multiple subplots show the results for various minibatch sizes (τ = 5, 10, 20). Each subplot displays curves for several different step sizes, illustrating how the convergence rate changes with varying γ and τ. The y-axis represents the function value suboptimality (f(xk) - f(x*)), and the x-axis represents the number of iterations.

read the caption

Figure 5: Comparison in terms of iteration complexity for FedExProx with different step sizes γ chosen from {0.0001, 0.0005, 0.01, 1, 10} in the client partial participation case. Different client minibatch sizes are used, the minibatch size τ is chosen from {5, 10, 20}.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of three different algorithms: FedExProx, FedExProx-GraDS, and FedExProx-StoPS. All three algorithms aim to minimize a loss function, but they use different extrapolation strategies. The x-axis represents the number of iterations, and the y-axis shows the difference between the current function value and the minimum function value. Different lines represent different step sizes (γ), showing how the convergence rate changes with the choice of step size for each algorithm. The results demonstrate that the adaptive extrapolation methods (FedProx-GraDS and FedExProx-StoPS) generally outperform the basic FedExProx approach, especially when the step size (γ) is sufficiently large.

read the caption

Figure 6: Comparison of FedExProx, FedExProx-GraDS and FedExProx-StoPS in terms of iteration complexity with different step sizes γ chosen from {0.0005, 0.0005, 0.05, 0.5, 1, 5} in the full participation setting.

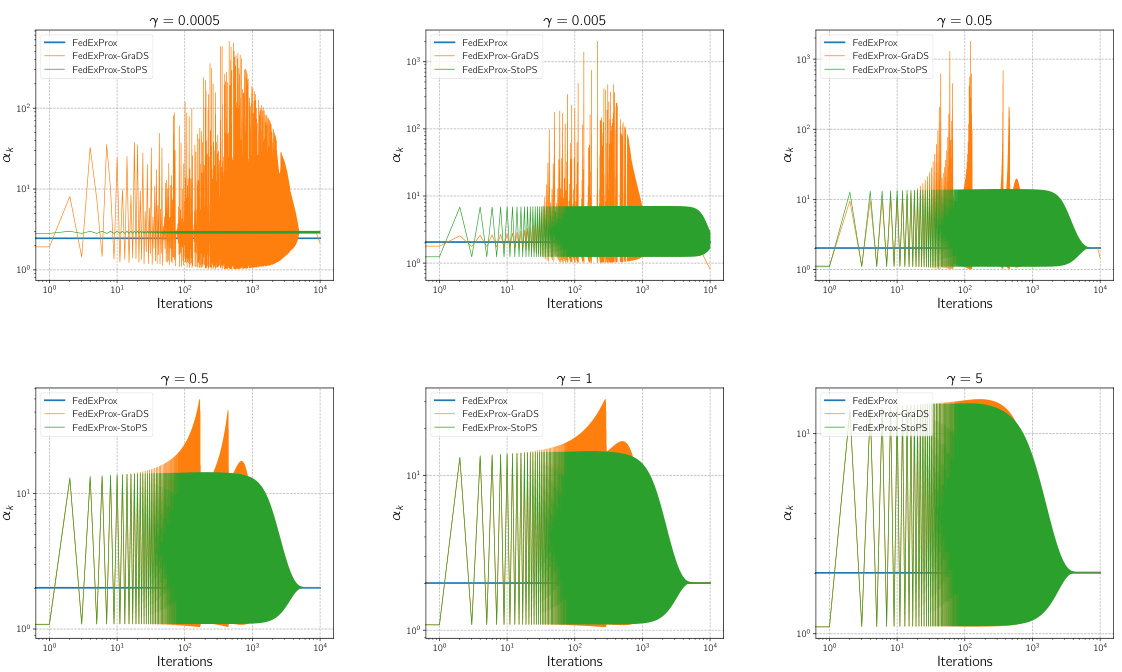

🔼 This figure compares the extrapolation parameter αk used in three different algorithms (FedExProx, FedExProx-GraDS, and FedExProx-StoPS) across various iterations. Different plots show the results for different values of the step size γ (0.0005, 0.005, 0.05, 0.5, 1, 5). The y-axis represents the value of αk (on a logarithmic scale), and the x-axis represents the iteration number. The plots illustrate how the adaptive extrapolation strategies in FedExProx-GraDS and FedExProx-StoPS adjust the extrapolation parameter αk across iterations, in contrast to the constant αk used in FedExProx.

read the caption

Figure 7: Comparison of the extrapolation parameter αk used by FedExProx, FedExProx-GraDS and FedExProx-StoPS in each iteration with different step sizes γ chosen from {0.0005, 0.0005, 0.05, 0.5, 1, 5} in the full participation setting.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of FedExProx and its two adaptive variants (FedProx-GraDS-PP and FedExProx-StoPS-PP) in terms of iteration complexity under various settings. The experiment considers different step sizes (γ) and client minibatch sizes (τ) in a partial client participation scenario. The results show the convergence rate of each algorithm across different parameter settings.

read the caption

Figure 8: Comparison of FedExProx, FedExProx-GraDS-PP and FedExProx-StoPS-PP in terms of iteration complexity with different step sizes γ in the client partial participation (PP) setting. The client minibatch size τ is chosen from {5, 10, 20}, for each minibatch size, a step size γ ∈ {0.001, 0.005, 0.1, 0.5, 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, 500} is randomly selected.

More on tables

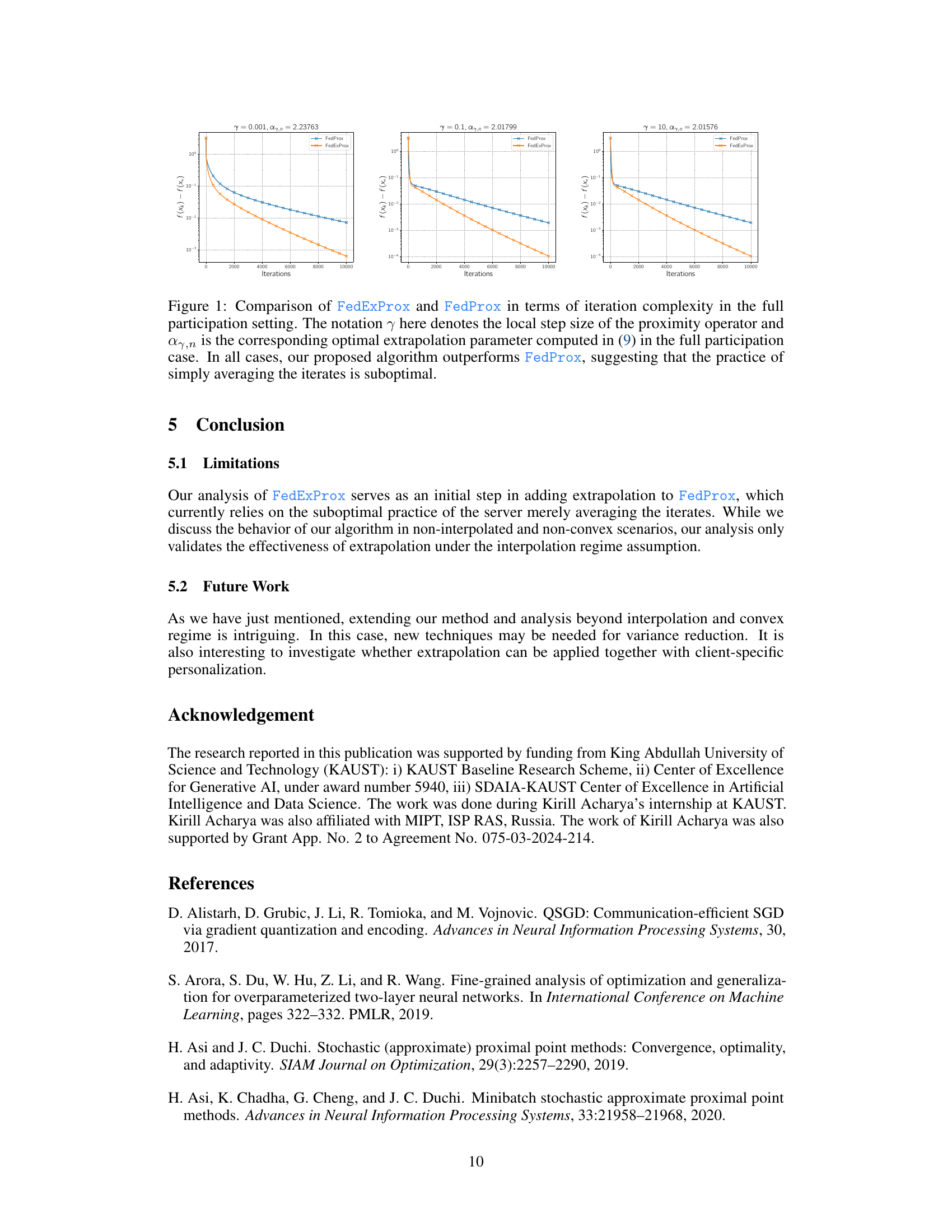

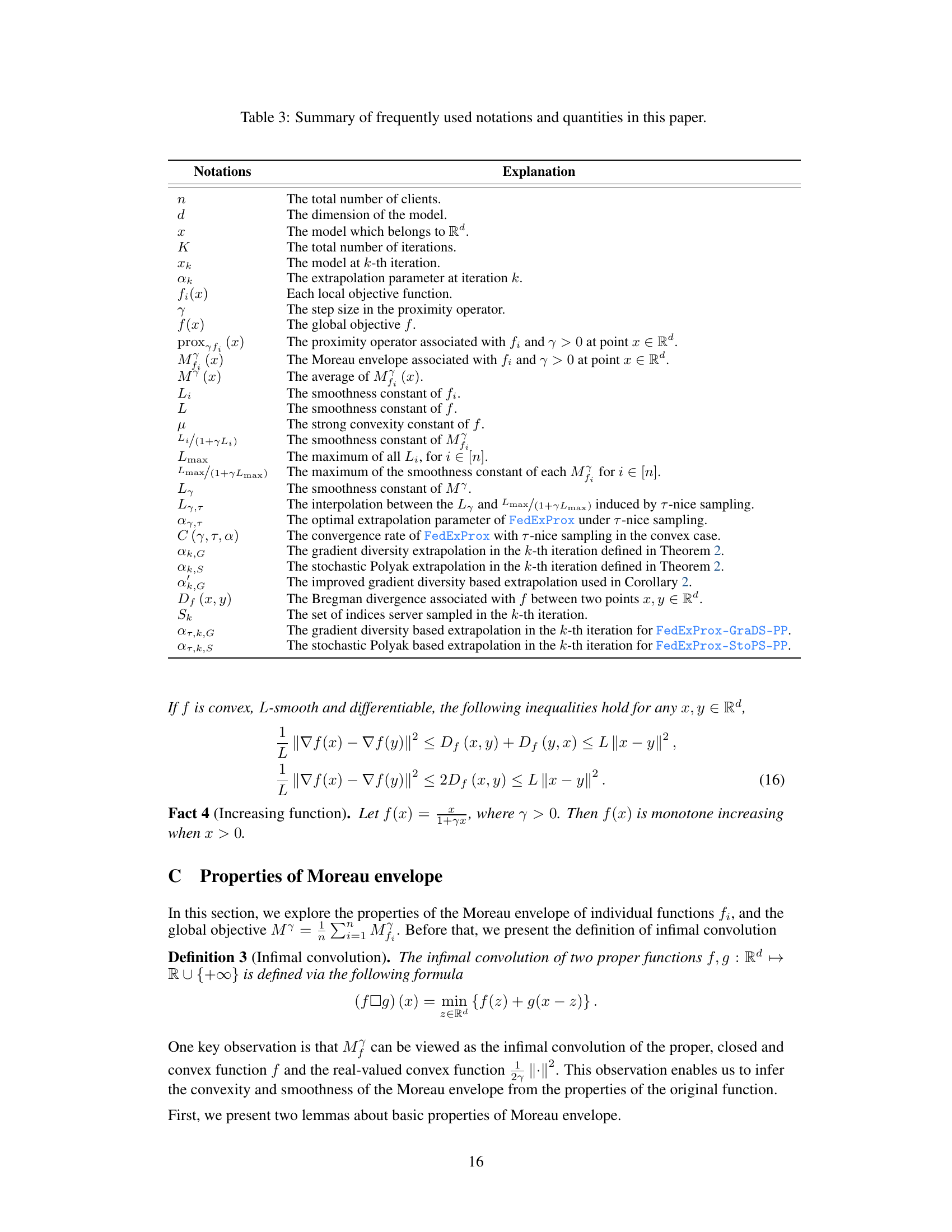

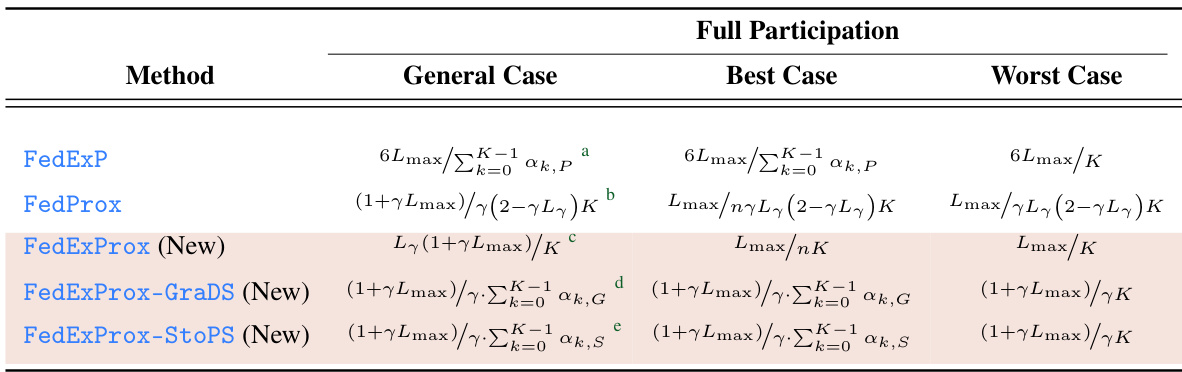

🔼 This table compares the convergence rates of several federated learning optimization methods. It shows the iteration complexity (general, best-case, and worst-case scenarios) for FedExP, FedProx, and the proposed FedExProx variants (FedExProx, FedExProx-GraDS, and FedExProx-StoPS). The table highlights the impact of various factors, including whether the model is strongly convex, the number of participating devices, and the use of adaptive extrapolation strategies. The results demonstrate improved convergence rates for the proposed methods.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of convergence of FedExP, FedProx, FedExProx, FedExProx-GraDS and FedExProx-StoPS. The local step size of FedExP is set to be the largest possible value 1/6tL in the full batch case, where t is the number of local iterations of GD performed. We assume the assumptions of Theorem 1 also hold here. The notations are introduced in Theorem 1 and Theorem 2. The convergence for our methods are described for arbitrary γ > 0. We use K to denote the total number of iterations. For FedExProx, optimal constant extrapolation is used. The O (·) notation is hidden for all complexities in this table.

🔼 This table compares three different federated learning methods: FedExP, RPM, and FedExProx. It highlights key features and requirements of each method, such as whether they require the interpolation regime, convexity, smoothness, and constant extrapolation parameters. It also indicates whether each method supports partial client participation and adaptive extrapolation strategies. The table helps readers understand the differences and trade-offs among the three methods.

read the caption

Table 1: General comparison of FedExP, RPM and FedExProx in terms of conditions and convergence. Each entry indicates whether the method has the corresponding feature (✔) or not (X). We use the sign '-' where a feature is not applicable to the corresponding method.

🔼 This table compares three methods: FedExP, RPM, and FedExProx, highlighting their requirements and convergence properties. It shows whether each method needs an interpolation regime, convexity, smoothness, allows partial client participation, uses a constant extrapolation parameter, and has semi-adaptivity. It provides a concise summary of the key differences between the algorithms.

read the caption

Table 1: General comparison of FedExP, RPMa and FedExProx in terms of conditions and convergence. Each entry indicates whether the method has the corresponding feature (✓) or not (✗). We use the sign “—” where a feature is not applicable to the corresponding method.

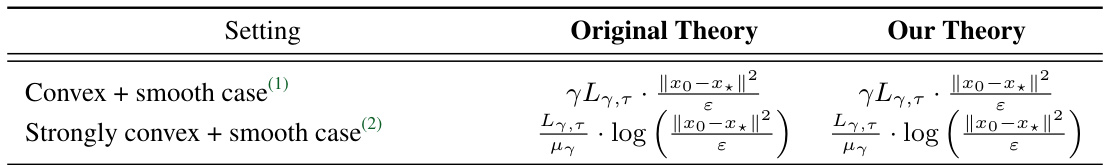

🔼 This table summarizes the iteration complexities of FedExProx, FedExProx-GraDS, and FedExProx-StoPS in different participation settings (full participation, partial participation, and single client). The complexities are given in Big O notation and depend on parameters such as the smoothness constant (Lmax or Ly), the step size (γ), and the extrapolation parameter (αk). The table provides a concise comparison of the convergence rates of the proposed algorithms and highlights the impact of different participation strategies on the overall iteration complexity.

read the caption

Table 5: Summary of convergence of new algorithms appeared in our paper in the convex setting. The O(·) notation is hidden for all complexities in this table. For convergence in the full client participation case, results of Theorem 1 and Theorem 2 are used where the relevant notations are defined. For convergence in the partial participation, the results of Theorem 5 are used.

Full paper#