TL;DR#

Current instruction-following AI agents face challenges in sample efficiency and generalizability due to the high cost and complexity of obtaining expert demonstrations or using LLMs directly for action prediction. This paper addresses these issues by introducing Language Feedback Models (LFMs). LFMs improve sample efficiency by learning from LLM feedback on a small number of trajectories, avoiding costly online LLM queries.

The proposed LFMs method trains a feedback model to identify productive actions based on LLM-provided feedback for each step. This model then guides imitation learning, enabling efficient policy improvement by directly imitating the productive actions. Experiments on multiple instruction-following benchmarks showcase that LFMs significantly outperform baselines in task completion rates while generalizing well to unseen environments. The human-interpretable nature of the LFM feedback further enhances the system’s transparency and usability.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in AI and robotics as it introduces a novel and efficient method for policy improvement in instruction following. Its sample efficiency and cost-effectiveness, achieved through the use of Language Feedback Models (LFMs), directly address major challenges in the field. The research opens new avenues for exploration in grounded instruction following, particularly in environments with complex, long-horizon tasks and limited data. Its focus on human-interpretable feedback further strengthens its impact.

Visual Insights#

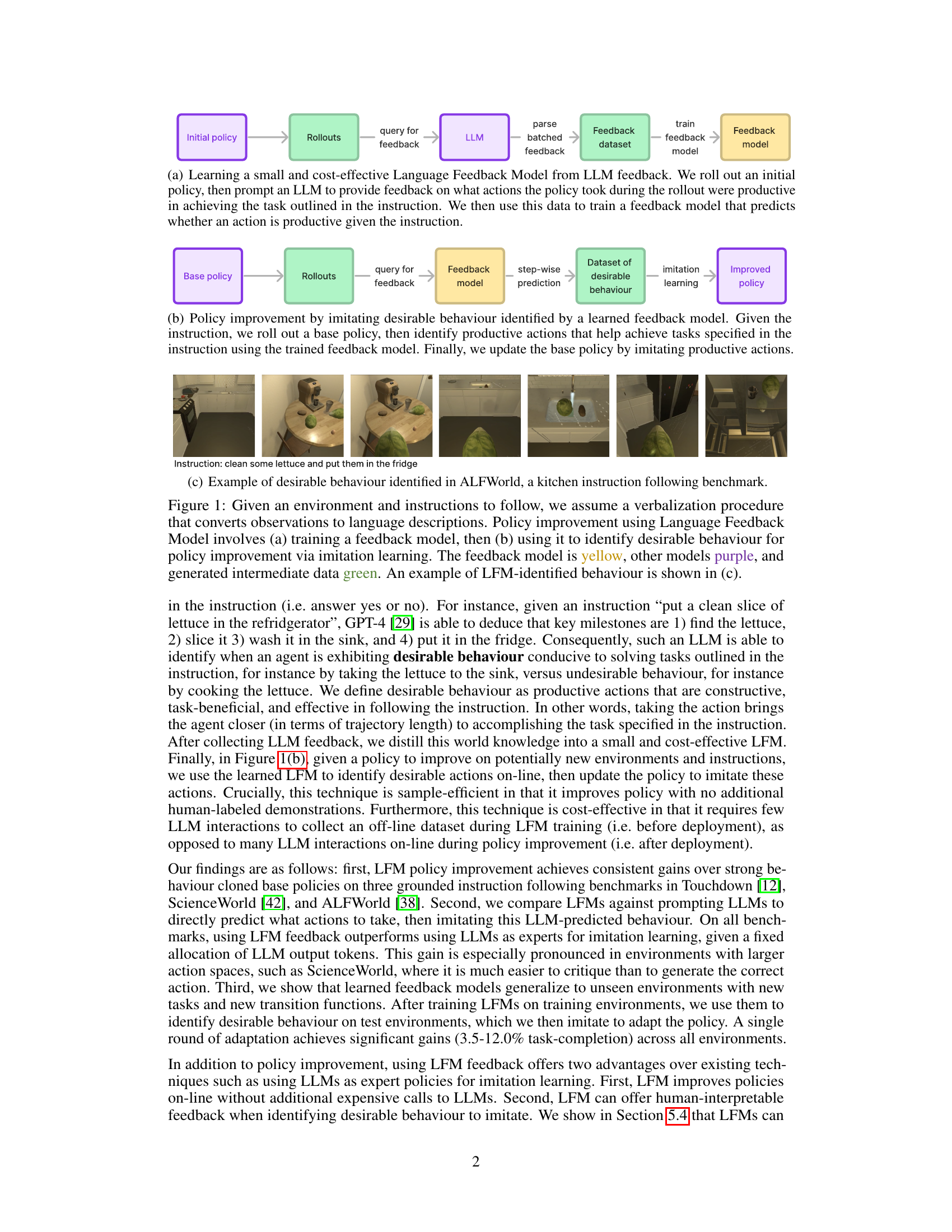

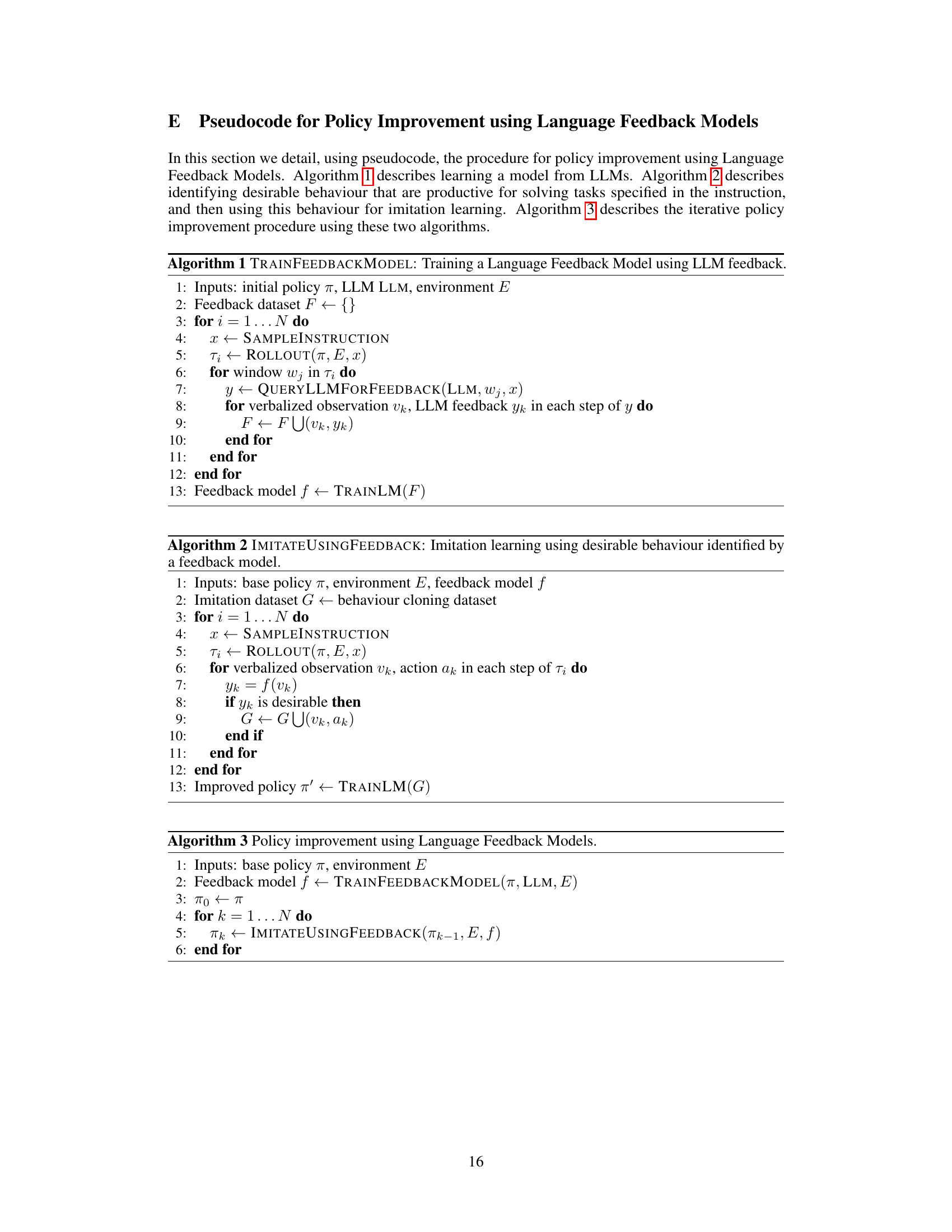

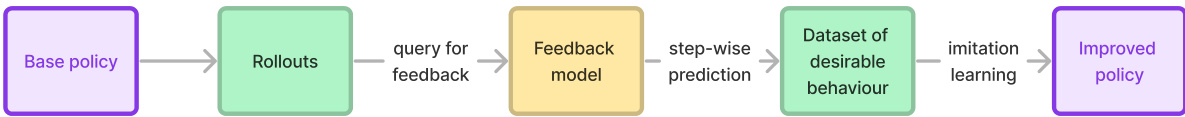

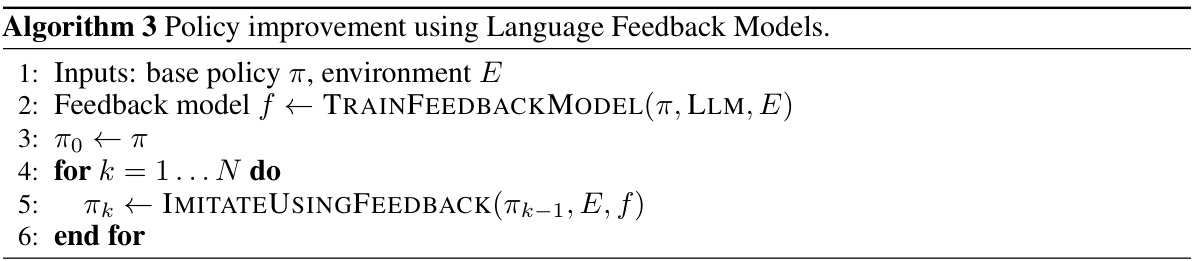

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall process of policy improvement using Language Feedback Models (LFMs). It consists of three parts: (a) Training an LFM using feedback from a Large Language Model (LLM): An initial policy is used to generate rollouts in an environment, these rollouts are then verbalized into language descriptions, and these descriptions are given to the LLM to provide feedback on which actions were productive. This feedback is used to train the LFM. (b) Using the trained LFM to identify desirable behavior: Given an instruction, the base policy generates rollouts and the LFM predicts which actions are productive. These productive actions are used to update the base policy. (c) An example of desirable behavior identified by the LFM: This example shows a kitchen environment where the task is to clean some lettuce and put them in the fridge. The LFM identifies the actions of cleaning the lettuce and putting it in the fridge as productive behavior.

read the caption

Figure 1: Given an environment and instructions to follow, we assume a verbalization procedure that converts observations to language descriptions. Policy improvement using Language Feedback Model involves (a) training a feedback model, then (b) using it to identify desirable behaviour for policy improvement via imitation learning. The feedback model is yellow, other models purple, and generated intermediate data green. An example of LFM-identified behaviour is shown in (c).

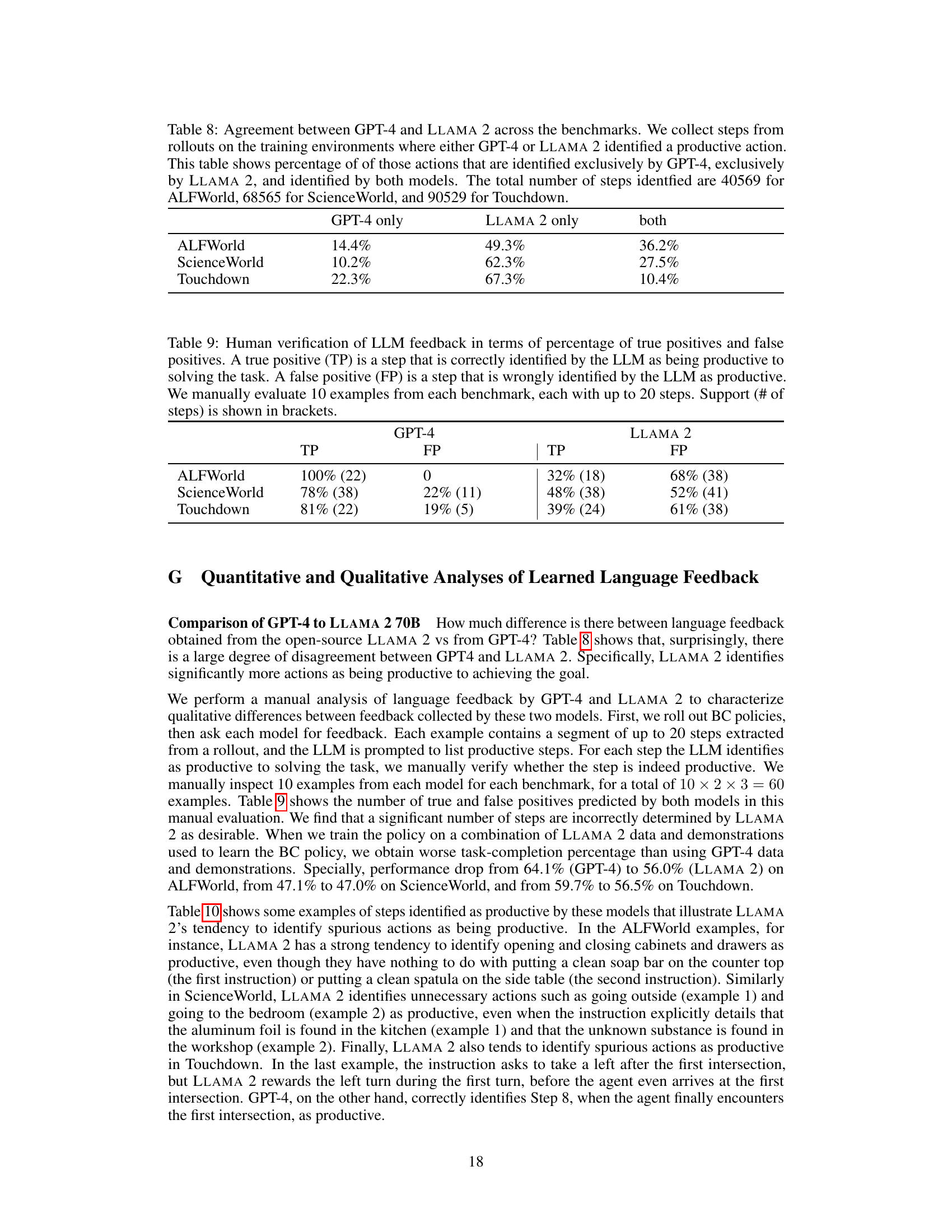

🔼 This table provides examples of how visual observations are converted into language descriptions for three different benchmarks: ALFWorld, ScienceWorld, and Touchdown. For each benchmark, it shows the task, the observations at different time steps (T-1, T-2), and the corresponding actions taken by the agent. The ellipses (’…’) indicate that some parts of the verbalized observations are shortened for brevity.

read the caption

Table 1: Examples of verbalization. We abbreviate long verbalized observations using '...'

In-depth insights#

LLM Feedback Distillation#

LLM Feedback Distillation is a crucial technique for making large language models (LLMs) more efficient and practical for real-world applications. The core idea is to capture the valuable knowledge embedded within often expensive and slow LLM feedback and compress it into a smaller, faster, and more easily deployable model. This distilled knowledge can then be used to guide other machine learning models, significantly reducing the computational cost and latency associated with directly querying the LLM. Key challenges in LLM feedback distillation include effectively representing the high-dimensional feedback from LLMs, designing suitable distillation architectures to capture both accuracy and efficiency, and handling the potential noise and inconsistencies inherent in LLM outputs. Successful distillation requires a careful balance between compression, preserving the quality of feedback and the target application’s requirements. The ultimate goal is to retain the decision-making capabilities of the LLM while reducing the overall resource consumption and improving model accessibility.

LFMs for Policy Boost#

The concept of “LFMs for Policy Boost” presents a compelling approach to enhance the performance of policies in complex, instruction-following tasks. Language Feedback Models (LFMs) offer a sample-efficient and cost-effective method to improve policies by leveraging the knowledge embedded in Large Language Models (LLMs). Instead of relying on expensive, on-line LLM interactions during policy learning, LFMs distill this knowledge into a compact model that can identify desirable behaviors from policy rollouts. This offline training significantly reduces computational costs. The subsequent imitation learning based on LFM-identified desirable behaviors leads to substantial performance gains. Furthermore, the ability of LFMs to generalize to unseen environments through one round of adaptation is a key advantage. The human-interpretable feedback provided by LFMs is another valuable contribution, fostering increased transparency and allowing for human verification. However, challenges remain in handling potentially inaccurate feedback from LLMs and ensuring robust generalization across diverse environments. Future research could explore more sophisticated ways to integrate LLM feedback and address the issue of LLM hallucination to further improve LFM’s effectiveness and reliability.

Generalization & Adaption#

The capacity of a model to generalize to unseen data and adapt to new environments is critical. Generalization assesses a model’s ability to perform well on data outside its training set, reflecting its learned knowledge’s robustness and breadth. Adaptation, on the other hand, focuses on a model’s capacity to quickly adjust and fine-tune its performance for specific, novel environments or tasks. Effective generalization and adaptation are intertwined. A model that generalizes well might still require adaptation to fully optimize performance in a new context. Conversely, a highly adaptable model might fail to generalize if its adaptations aren’t grounded in robust foundational knowledge. In research, assessing both aspects is crucial for creating truly versatile and robust AI systems. The interplay between these two concepts is key; successful generalization reduces the need for extensive adaptation, while strong adaptation capabilities enhance a model’s robustness despite limitations in initial generalization. Therefore, a balanced approach focusing on both aspects is paramount.

Interpretable Feedback#

The concept of “Interpretable Feedback” in the context of AI instruction following is crucial for building trust and facilitating human oversight. Providing not just whether an action is productive, but why, greatly enhances the value of the feedback. This allows humans to verify the AI’s reasoning, identify potential biases, and correct errors more effectively. Human-interpretable feedback allows for a more collaborative human-AI partnership, where humans can guide the AI’s learning process instead of simply relying on opaque automated feedback. A key benefit is the ability to identify and correct potentially harmful or undesired behavior. By examining the explanations for both positive and negative feedback, developers can improve their models and ensure that they align with human values and expectations. This focus on transparency and explainability is essential for responsible AI development, ensuring that AI systems are not only effective but also ethically sound.

Limitations & Future#

This research makes valuable contributions to policy improvement in instruction following, but several limitations warrant attention. The reliance on a robust verbalization procedure to translate visual observations into language descriptions is crucial; however, this process is inherently complex and prone to errors, especially in richly detailed environments. The accuracy of language models themselves is another factor; their propensity for hallucination or inaccurate feedback could significantly impact the effectiveness of the proposed method. Furthermore, the computational cost of training and deploying the resulting models, particularly large language models, presents a scalability challenge. Future work could focus on addressing these limitations. This includes exploring more robust verbalization methods, investigating techniques for mitigating errors in LLM feedback, and developing more efficient, lightweight models that maintain performance. Improving the generalizability of the approach to new and unseen environments is crucial for broader real-world applications. The exploration of more diverse benchmarks, the application to more complex tasks, and methods to quantify uncertainty in predictions are all vital research avenues.

More visual insights#

More on figures

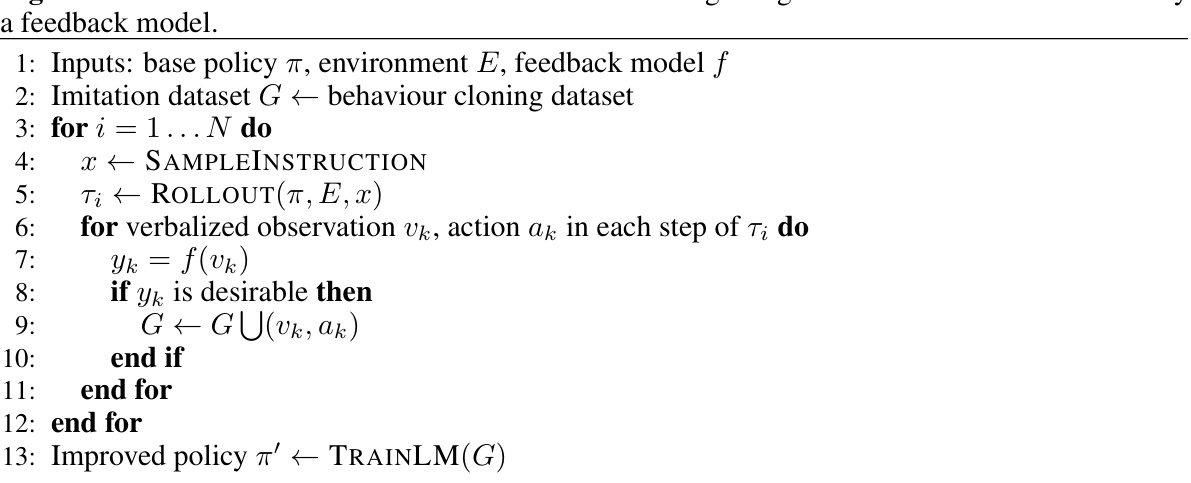

🔼 This figure illustrates the process of policy improvement using Language Feedback Models (LFMs). It starts with an initial policy that is used to generate rollouts in a given environment. These rollouts are then verbalized into language descriptions. An LLM provides feedback on which actions in the trajectories were productive in achieving the task, as indicated by the instructions. This feedback is used to train a Language Feedback Model (LFM). The LFM is then used to identify productive actions from new rollouts of the base policy. Finally, imitation learning is performed using these productive actions to create an improved policy. The figure shows the overall process with subfigures detailing the training of the LFM and the policy improvement steps.

read the caption

Figure 1: Given an environment and instructions to follow, we assume a verbalization procedure that converts observations to language descriptions. Policy improvement using Language Feedback Model involves (a) training a feedback model, then (b) using it to identify desirable behaviour for policy improvement via imitation learning. The feedback model is yellow, other models purple, and generated intermediate data green. An example of LFM-identified behaviour is shown in (c).

🔼 This figure illustrates the policy improvement process using Language Feedback Models (LFMs). It shows three parts: (a) training an LFM using LLM feedback from an initial policy’s rollout; (b) using the trained LFM to identify desirable behavior for imitation learning and updating the base policy; (c) an example of desirable behavior identified by the LFM in a kitchen environment.

read the caption

Figure 1: Given an environment and instructions to follow, we assume a verbalization procedure that converts observations to language descriptions. Policy improvement using Language Feedback Model involves (a) training a feedback model, then (b) using it to identify desirable behaviour for policy improvement via imitation learning. The feedback model is yellow, other models purple, and generated intermediate data green. An example of LFM-identified behaviour is shown in (c).

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall process of policy improvement using Language Feedback Models (LFMs). It’s broken down into three parts: (a) Shows the training of the LFM using Large Language Model (LLM) feedback. An initial policy is rolled out, and an LLM provides feedback on which actions were productive, this data is used to train the LFM which predicts whether an action is productive. (b) Shows the policy improvement process using the trained LFM. The LFM identifies productive actions from a base policy’s rollout, and then these actions are used to improve the base policy using imitation learning. (c) Provides an example of LFM-identified desirable behavior in a kitchen environment, highlighting the practical application of the method.

read the caption

Figure 1: Given an environment and instructions to follow, we assume a verbalization procedure that converts observations to language descriptions. Policy improvement using Language Feedback Model involves (a) training a feedback model, then (b) using it to identify desirable behaviour for policy improvement via imitation learning. The feedback model is yellow, other models purple, and generated intermediate data green. An example of LFM-identified behaviour is shown in (c).

More on tables

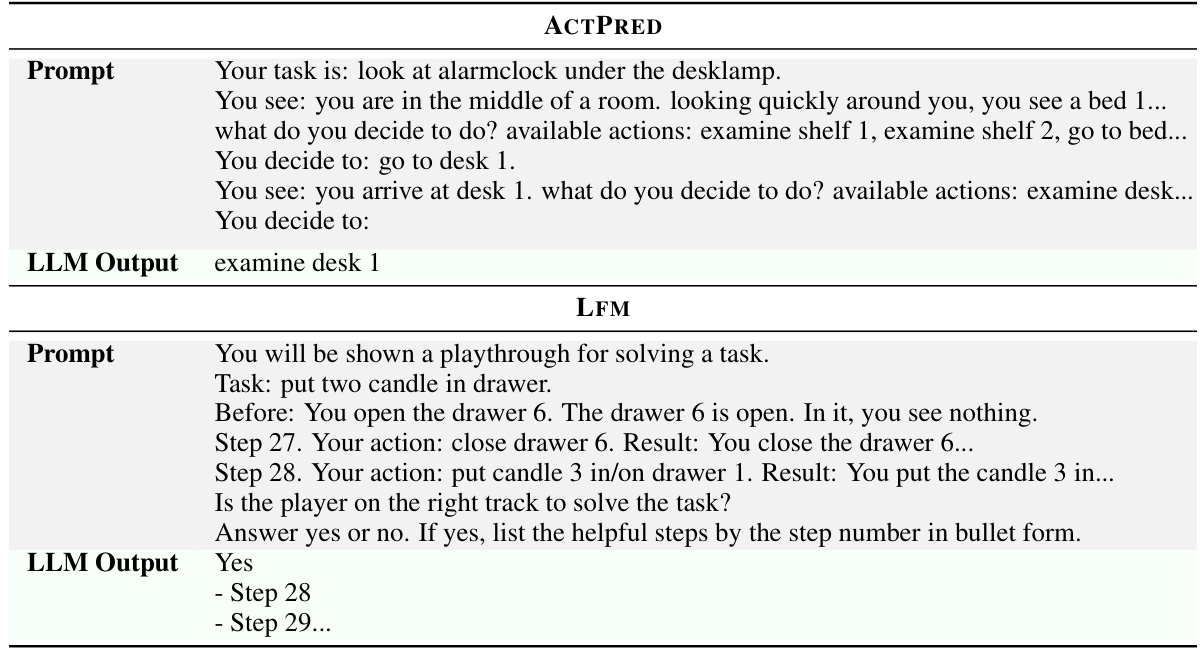

🔼 This table presents the prompts used to collect data from LLMs using two different methods: ACTPRED and LFM. ACTPRED directly prompts the LLM to generate the next action at each step, whereas LFM provides the LLM with a complete trajectory and asks for feedback on which actions were productive. The table shows examples of prompts for both methods and the corresponding LLM outputs.

read the caption

Table 2: LLM prompts used to collect desirable behaviour. ACTPRED uses LLMs to directly generate actions for each step, whereas LFM uses LLMs to generate batch feedback that identify which taken actions were productive. For brevity, we abbreviate long verbalized observations using '...'. “Before” contains the observation before the first step in the batch.

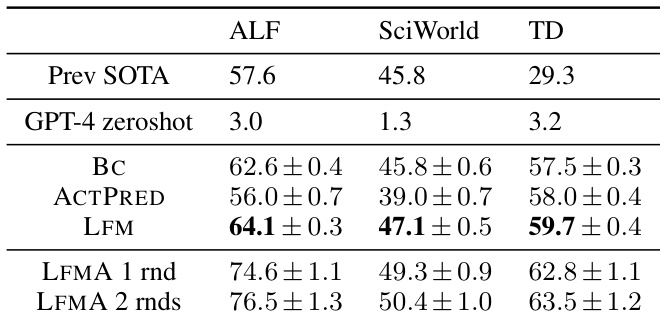

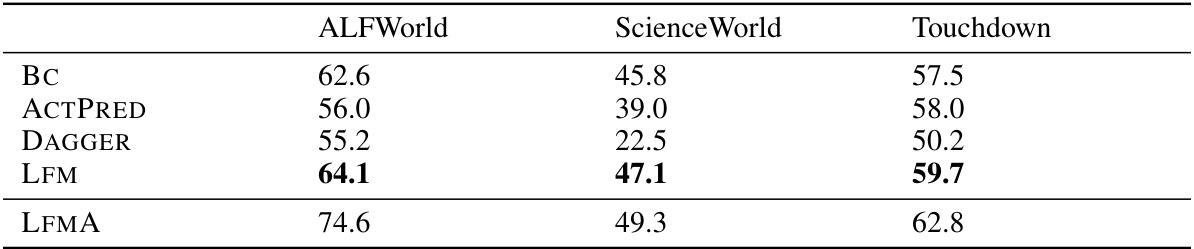

🔼 This table presents the task completion rates for three different instruction-following benchmarks (ALFWorld, ScienceWorld, and Touchdown) using four different methods: Behavior Cloning (BC), Imitation Learning using LLMs as experts (ACTPRED), Imitation Learning using Language Feedback Models (LFM), and LFM with one or two rounds of adaptation (LFMA). It compares the performance of these methods against previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) results and highlights the improvements achieved by using LFMs, particularly after adaptation to new environments. Error bars represent standard deviations across three independent runs.

read the caption

Table 3: Task completion rates of behaviour cloning BC, imitation learning (IL) using LLM expert ACTPRED, and IL using LFM. On held-out test environments, LFM outperforms other methods on all benchmarks. ACTPRED and LFM are limited to 100k output tokens of GPT-4 interactions. Further adaptation to the new environments using LFM results in significant additional gains (LFMA). Errors are standard deviations across 3 seeds. Previous SOTA are Micheli and Fleuret [27] for ALFWorld, Lin et al. [25] for ScienceWorld, and Schumann and Riezler [33] for Touchdown. Unlike Lin et al. [25], our methods do not use ScienceWorld-specific custom room tracking nor action reranking.

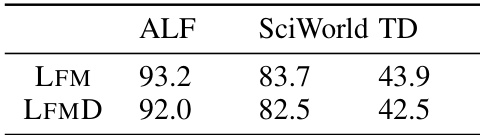

🔼 This table presents the F1 scores achieved by the Language Feedback Model (LFM) and the more detailed version (LFMD) in predicting whether an action taken by the agent is productive or not. The F1 scores are calculated using the Large Language Model (LLM) predictions as the ground truth. The results demonstrate that the performance of the LFM is not significantly affected by providing more detailed feedback, including explanations and summaries.

read the caption

Table 4: Feedback performance of LFM. We measure F1 score of the productive/not-productive predictions made by the learned LFM using the LLM predictions as ground truth. We observe no significant performance degradation when using a much more detailed feedback model (LFMD) that also provides explanations behind the feedback, summaries of agent behaviour, and strategy suggestions.

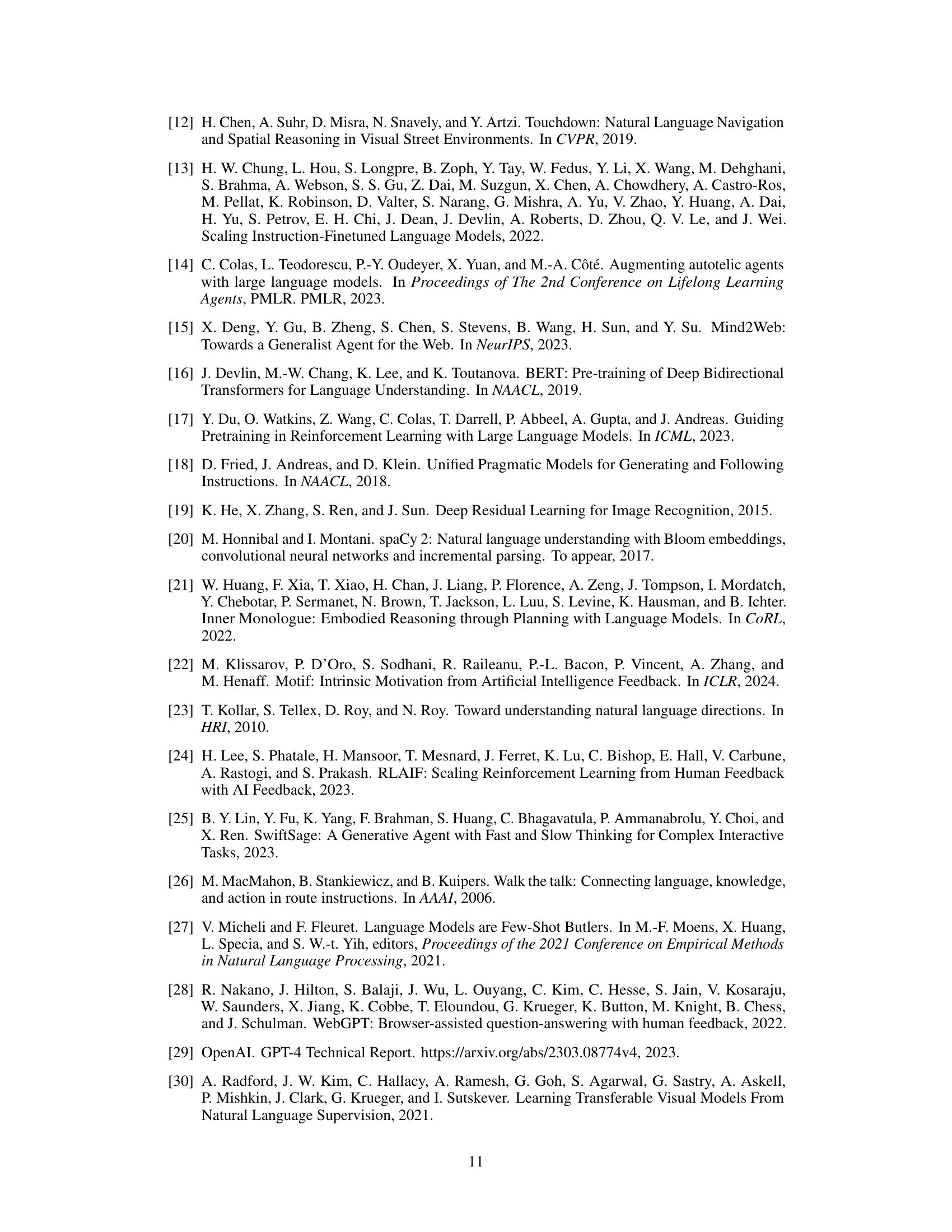

🔼 This table shows statistics for three different benchmarks (ALFWorld, SciWorld, and Touchdown) used in the paper. For each benchmark, it provides the average length (in GPT-2 tokens) of instructions, observations, and actions. It also gives the average trajectory length, the size of the action space, the number of unique actions, instructions, and observations, and the number of demonstrations used for training.

read the caption

Table 6: Statistics from benchmarks as measured by training demonstrations. The are the average number of GPT-2 tokens in the instruction, verbalized observation, and action; the average demonstration steps; the average number of plausible actions in a state; the number of unique actions, instructions, and observations; and finally the number of training demonstrations.

🔼 This table compares the performance of three different methods for improving a behaviour cloning baseline policy: using LLMs as experts to directly predict actions (ACTPRED), using Language Feedback Models (LFM), and further adapting the LFM policy to new unseen environments (LFMA). The results show that LFM outperforms both ACTPRED and the baseline across three different benchmarks, and LFMA provides further significant gains.

read the caption

Table 3: Task completion rates of behaviour cloning BC, imitation learning (IL) using LLM expert ACTPRED, and IL using LFM. On held-out test environments, LFM outperforms other methods on all benchmarks. ACTPRED and LFM are limited to 100k output tokens of GPT-4 interactions. Further adaptation to the new environments using LFM results in significant additional gains (LFMA). Errors are standard deviations across 3 seeds. Previous SOTA are Micheli and Fleuret [27] for ALFWorld, Lin et al. [25] for ScienceWorld, and Schumann and Riezler [33] for Touchdown. Unlike Lin et al. [25], our methods do not use ScienceWorld-specific custom room tracking nor action reranking.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of task completion rates for different methods on three instruction following benchmarks. It shows that using Language Feedback Models (LFM) significantly outperforms baseline methods, including behaviour cloning (BC) and using Large Language Models (LLM) directly to predict actions (ACTPRED). Furthermore, it demonstrates the generalizability of LFMs through one round of adaptation to new environments (LFMA), leading to further performance improvements. The table also includes the previous state-of-the-art (SOTA) results for context.

read the caption

Table 3: Task completion rates of behaviour cloning BC, imitation learning (IL) using LLM expert ACTPRED, and IL using LFM. On held-out test environments, LFM outperforms other methods on all benchmarks. ACTPRED and LFM are limited to 100k output tokens of GPT-4 interactions. Further adaptation to the new environments using LFM results in significant additional gains (LFMA). Errors are standard deviations across 3 seeds. Previous SOTA are Micheli and Fleuret [27] for ALFWorld, Lin et al. [25] for ScienceWorld, and Schumann and Riezler [33] for Touchdown. Unlike Lin et al. [25], our methods do not use ScienceWorld-specific custom room tracking nor action reranking.

🔼 This table presents the task completion rates achieved by different methods on three benchmarks: ALFWorld, ScienceWorld, and Touchdown. It compares the performance of behavior cloning (BC), imitation learning with LLMs as experts for action prediction (ACTPRED), imitation learning with language feedback models (LFM), and a further adaptation using LFM (LFMA). The results show that LFM consistently outperforms other methods across all benchmarks, highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed approach. The LFMA column shows significant performance improvements resulting from adapting the LFM to new environments.

read the caption

Table 3: Task completion rates of behaviour cloning BC, imitation learning (IL) using LLM expert ACTPRED, and IL using LFM. On held-out test environments, LFM outperforms other methods on all benchmarks. ACTPRED and LFM are limited to 100k output tokens of GPT-4 interactions. Further adaptation to the new environments using LFM results in significant additional gains (LFMA). Errors are standard deviations across 3 seeds. Previous SOTA are Micheli and Fleuret [27] for ALFWorld, Lin et al. [25] for ScienceWorld, and Schumann and Riezler [33] for Touchdown. Unlike Lin et al. [25], our methods do not use ScienceWorld-specific custom room tracking nor action reranking.

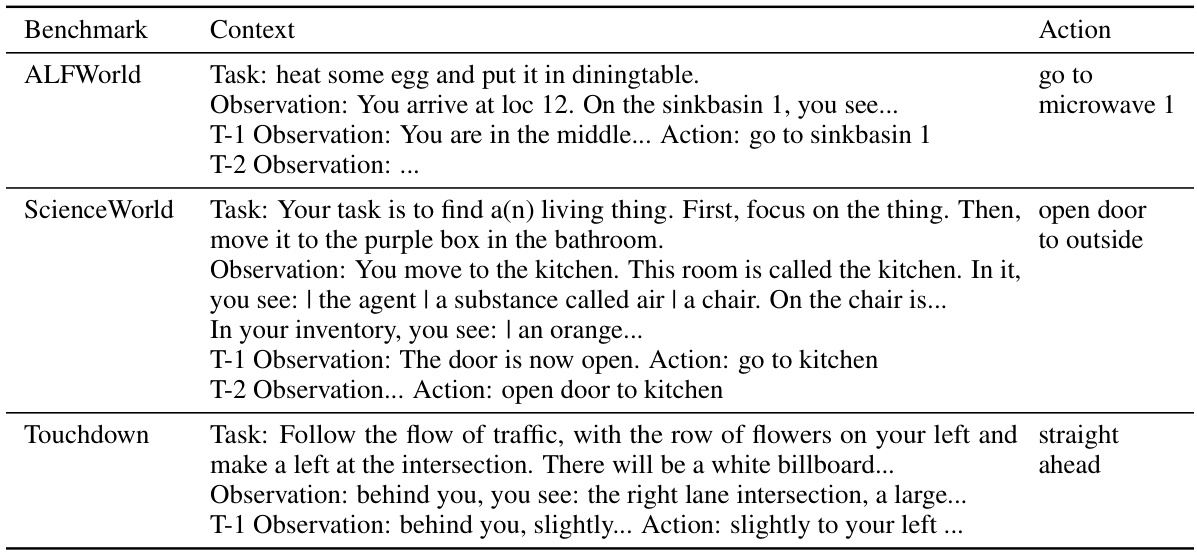

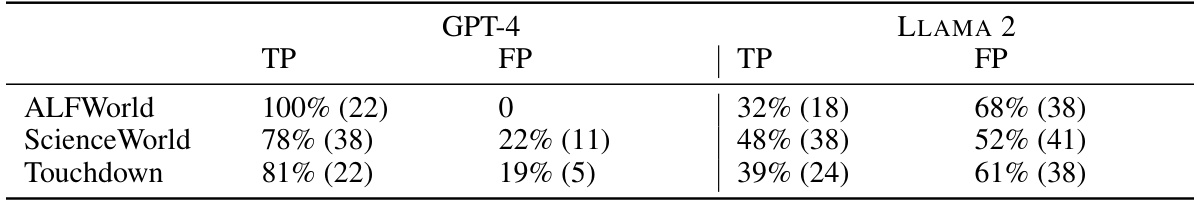

🔼 This table shows the agreement between GPT-4 and LLAMA 2 in identifying productive actions during the training phase. It breaks down the percentage of productive actions uniquely identified by each model and the percentage identified by both. The numbers of steps considered are specified for each benchmark.

read the caption

Table 8: Agreement between GPT-4 and LLAMA 2 across the benchmarks. We collect steps from rollouts on the training environments where either GPT-4 or LLAMA 2 identified a productive action. This table shows percentage of of those actions that are identified exclusively by GPT-4, exclusively by LLAMA 2, and identified by both models. The total number of steps identfied are 40569 for ALFWorld, 68565 for ScienceWorld, and 90529 for Touchdown.

🔼 This table presents the results of a human evaluation of LLM feedback. It shows the percentage of true positives (correctly identified productive steps) and false positives (incorrectly identified productive steps) for GPT-4 and LLAMA 2 across three benchmarks (ALFWorld, ScienceWorld, Touchdown). The evaluation was performed manually on 10 examples per benchmark, with each example containing up to 20 steps. The number of steps used in each evaluation is shown in parentheses.

read the caption

Table 9: Human verification of LLM feedback in terms of percentage of true positives and false positives. A true positive (TP) is a step that is correctly identified by the LLM as being productive to solving the task. A false positive (FP) is a step that is wrongly identified by the LLM as productive. We manually evaluate 10 examples from each benchmark, each with up to 20 steps. Support (# of steps) is shown in brackets.

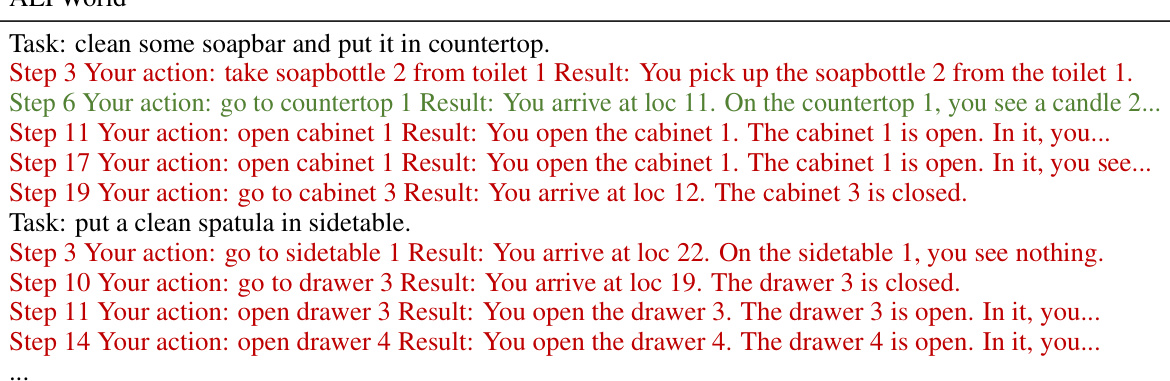

🔼 This table shows examples of steps identified as productive by GPT-4 and LLAMA 2 in three different benchmarks: ALFWorld, ScienceWorld, and Touchdown. For each benchmark, a task is described, and then a sequence of steps taken by an agent is shown. For each step, the agent’s action and the resulting observation are provided. The steps highlighted indicate those judged as productive towards task completion by either GPT-4, LLAMA 2, or both. The Touchdown examples are shortened for brevity.

read the caption

Table 10: Example steps identified as productive by GPT-4, LLAMA 2, and both. Touchdown steps are truncated for brevity.

Full paper#