TL;DR#

Conditional graph generation is vital in diverse scientific areas such as drug and material design, but existing methods struggle with the complexity of intricate interactions between graph structures and their properties. Traditional approaches, like classifier-based and classifier-free guidance, fall short in capturing these nuances, leading to suboptimal results. The vast combinatorial spaces involved pose significant challenges for brute-force techniques.

This paper introduces “Twigs,” a novel score-based diffusion framework that elegantly addresses these challenges. Twigs uses multiple co-evolving diffusion processes, a central ’trunk’ process for graph structures and additional ‘stem’ processes for properties. A key innovation, ’loop guidance,’ skillfully orchestrates information flow between these processes. Extensive experiments demonstrate Twigs’s superior performance across various tasks, significantly outperforming existing methods, proving its potential for complex conditional graph generation problems.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in conditional graph generation, particularly in scientific domains like drug and material design. It introduces a novel framework that significantly improves performance over existing methods, opening new avenues for tackling challenging generative tasks and advancing the field. The proposed loop guidance mechanism offers a new way to manage information flow in multi-process diffusion models, a valuable contribution to the broader score-based diffusion models community.

Visual Insights#

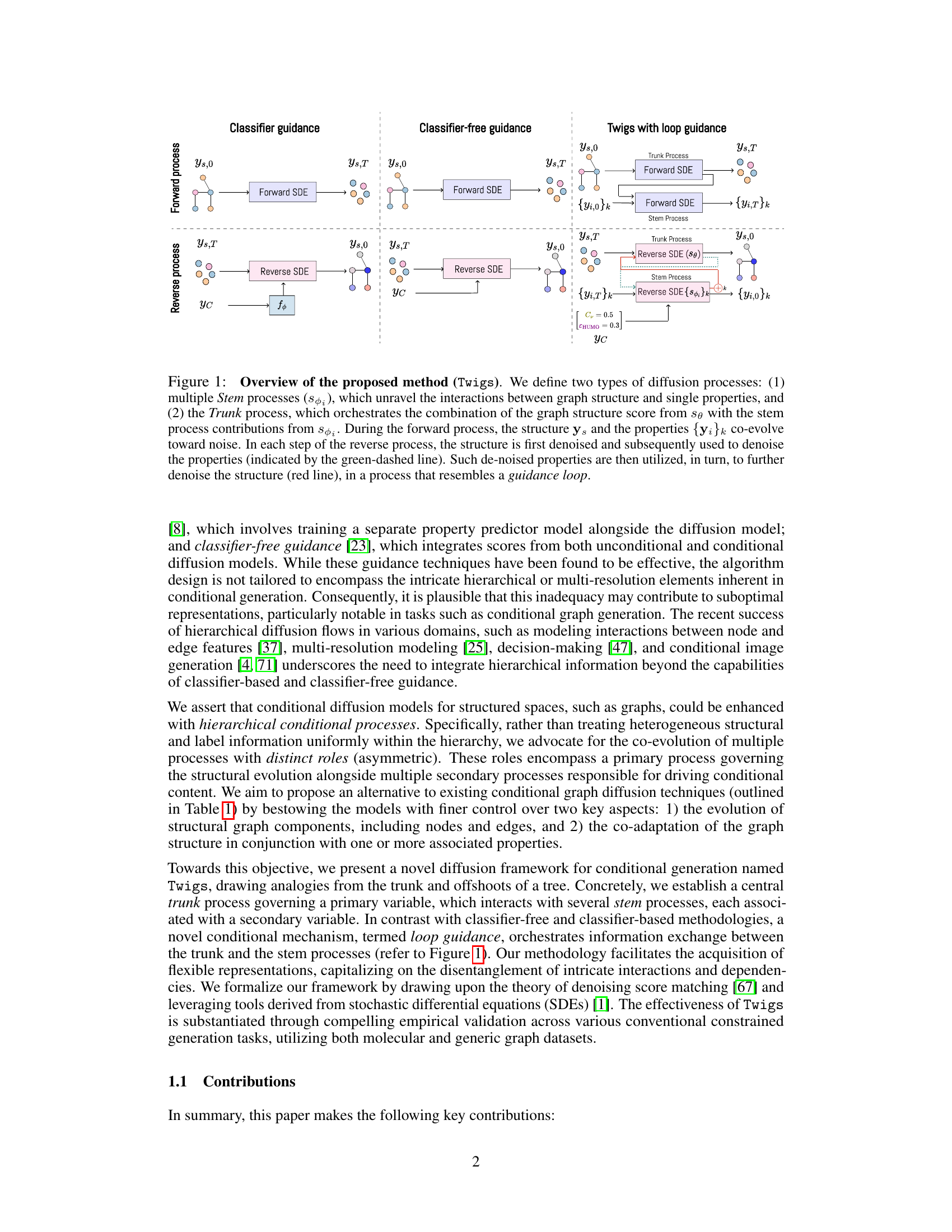

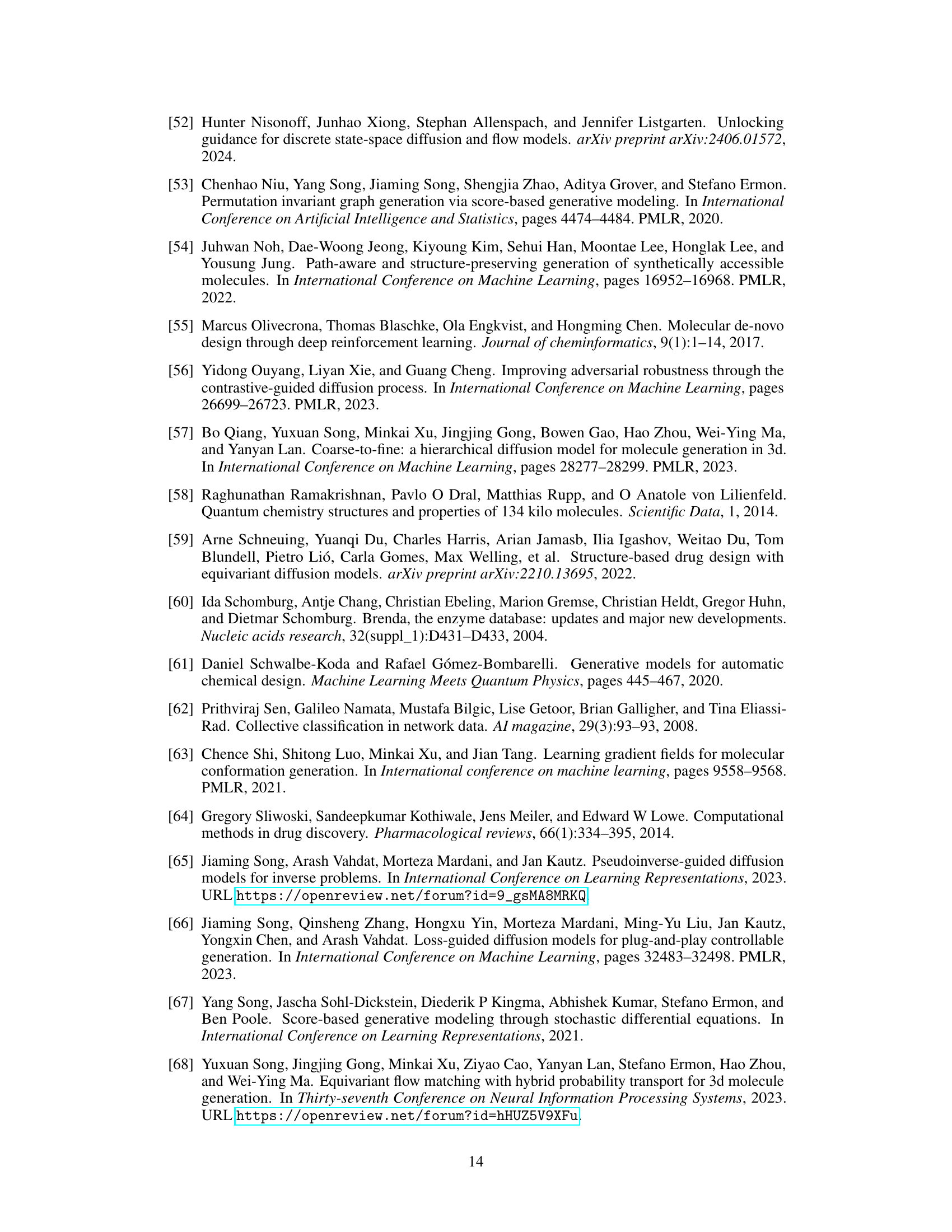

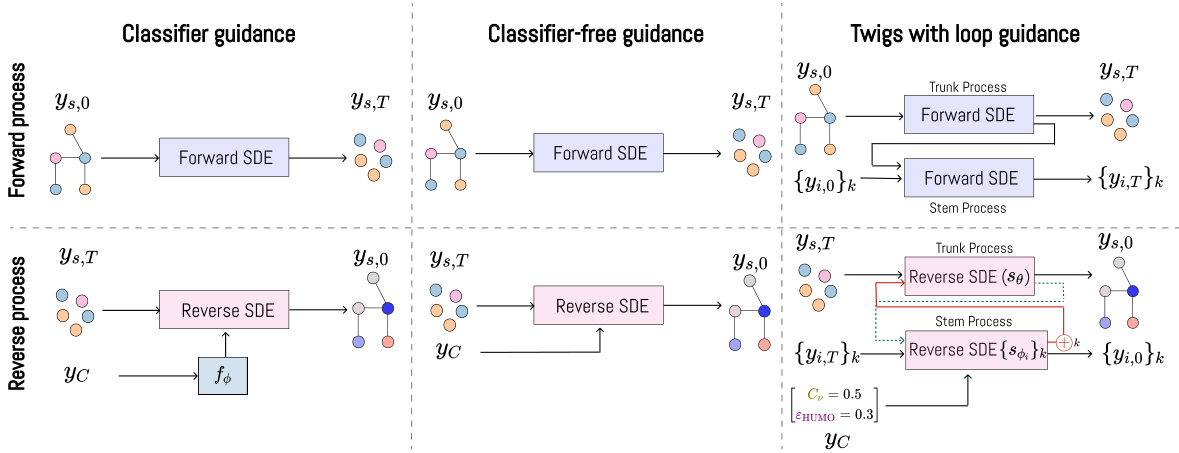

🔼 This figure illustrates the Twigs framework, comparing it to classifier guidance and classifier-free guidance. Twigs uses a central trunk diffusion process for the main variable (e.g., graph structure) and additional stem processes for dependent variables (e.g., graph properties). The key innovation is ’loop guidance’, where information flows between the trunk and stem processes during sampling, allowing for intricate interactions and dependencies.

read the caption

Figure 1: Overview of the proposed method (Twigs). We define two types of diffusion processes: (1) multiple Stem processes (sp₁), which unravel the interactions between graph structure and single properties, and (2) the Trunk process, which orchestrates the combination of the graph structure score from se with the stem process contributions from 84₁. During the forward process, the structure y, and the properties {yi}k co-evolve toward noise. In each step of the reverse process, the structure is first denoised and subsequently used to denoise the properties (indicated by the green-dashed line). Such de-noised properties are then utilized, in turn, to further denoise the structure (red line), in a process that resembles a guidance loop.

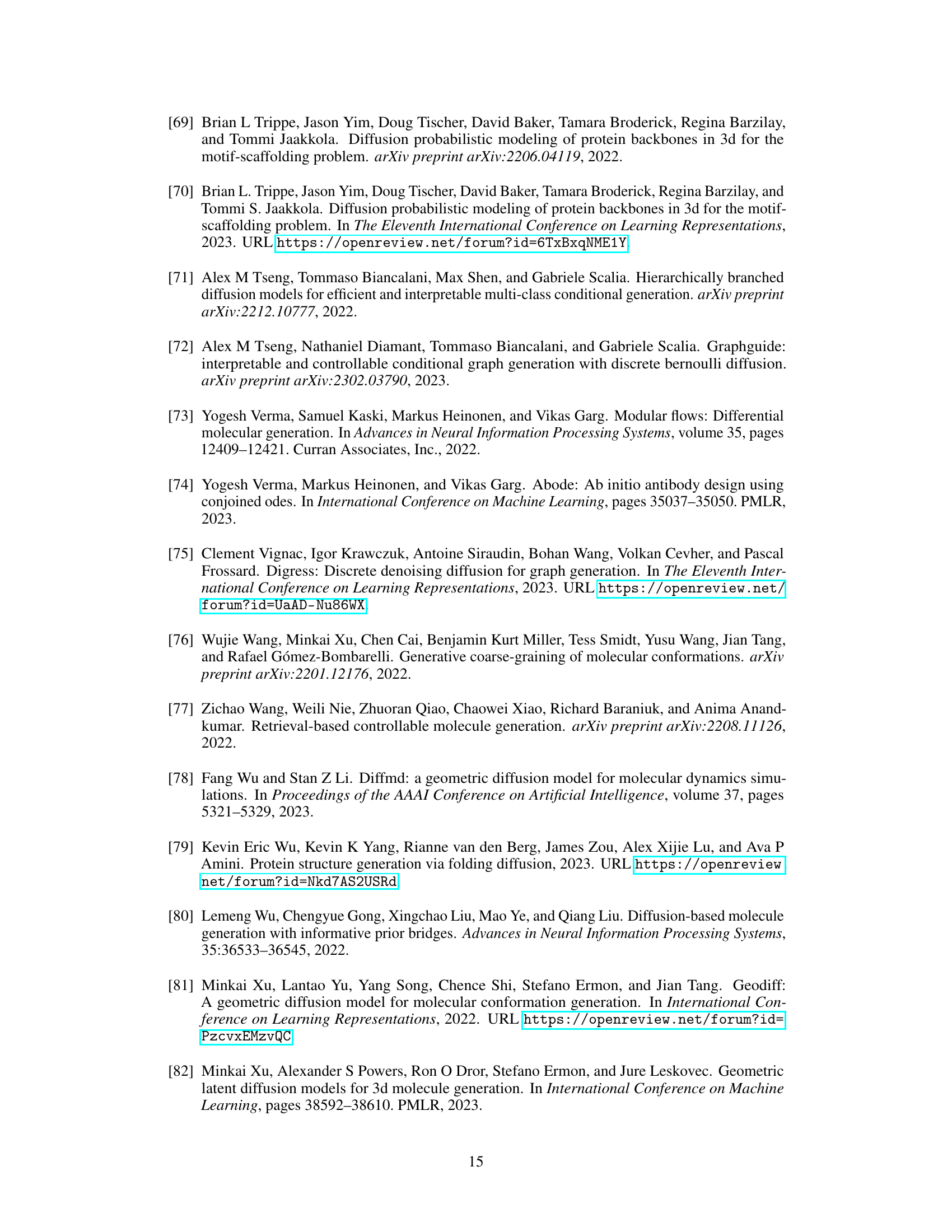

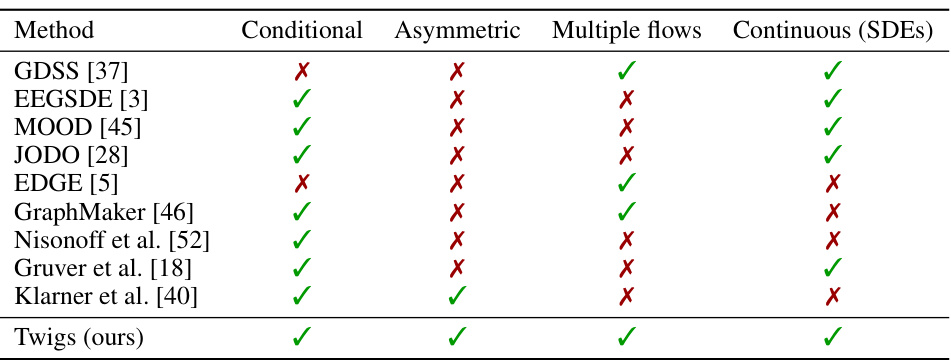

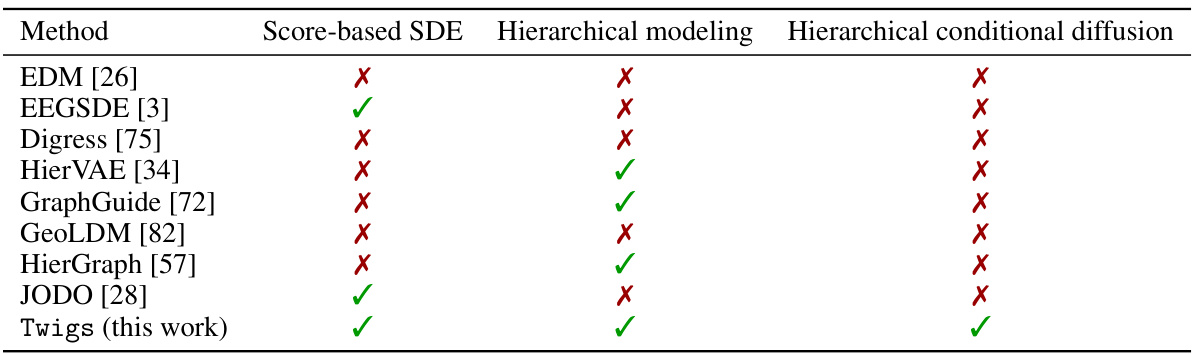

🔼 This table compares Twigs with other related methods focusing on four key aspects: whether they support conditional generation, whether they employ asymmetric processing of multiple flows (i.e. whether they treat different types of graph information differently), whether they use multiple flows to model different graph aspects, and finally whether they rely on stochastic differential equations (SDEs) for continuous modeling. The table highlights that Twigs is unique in its approach, seamlessly incorporating multiple asymmetric property-oriented hierarchical diffusion processes through SDEs.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of related methodologies. Twigs is the first method that enables a seamless orchestration of multiple asymmetric property-oriented hierarchical diffusion processes via SDEs.

In-depth insights#

Loop Guidance#

The concept of “Loop Guidance” in the context of conditional graph generation using diffusion models presents a novel approach to enhance the interaction between multiple diffusion processes. It suggests an iterative refinement where a primary diffusion process (the “trunk”) generates the graph structure, while secondary processes (the “stems”) handle individual properties or labels. The key innovation lies in the cyclical exchange of information between the trunk and stems. The trunk’s updated graph structure influences the stem’s refinement of the properties, and in turn, the improved properties guide further refinements of the graph structure within the trunk. This feedback loop allows for a more nuanced and accurate generation of conditional graphs, moving beyond the limitations of conventional classifier-based or classifier-free methods. Loop guidance enables the discovery of intricate dependencies between the graph structure and its properties, leading to improved results in challenging tasks such as molecular design. The effectiveness of this strategy is supported by the strong empirical performance gains demonstrated in experiments, highlighting the potential of this approach for complex conditional graph generation problems.

Multi-flow SDEs#

Multi-flow stochastic differential equations (SDEs) represent a powerful extension to traditional SDEs, particularly beneficial for modeling complex systems with intertwined processes. Instead of a single flow dictating system evolution, multiple, interacting flows capture diverse dynamics. This approach allows for modeling dependencies between variables, enabling the generation of more realistic and nuanced outcomes compared to single-flow SDEs. Each flow may represent a different aspect of the system, such as separate physical processes, or different levels of granularity in a hierarchical model. The challenge lies in designing the interaction mechanisms between these flows, ensuring proper convergence and avoiding undesirable interference. Techniques such as hierarchical guidance, or co-evolutionary processes, can help to orchestrate the flow interactions and improve performance. The primary benefits of multi-flow SDEs include improved accuracy, increased expressiveness, and the ability to model complex interactions present in many real-world systems. However, this enhancement comes with increased computational complexity compared to single-flow SDEs, posing a significant barrier for scaling and wider adoption.

Conditional Graphs#

Conditional graph generation, a significant area within machine learning, focuses on creating graphs that satisfy specific conditions. This contrasts with unconditional generation, which produces graphs without any constraints. The ‘condition’ could represent various properties, such as node attributes, edge weights, graph topology, or even external factors influencing the graph structure. The challenge lies in learning the complex relationships between these conditions and the resulting graph structure. Effective methods often involve sophisticated deep learning models, capable of encoding both structural information and conditional constraints. Score-based diffusion models have shown promise, offering a powerful approach to sample from complex probability distributions over graph structures. However, challenges remain in dealing with large, diverse graph types and ensuring both efficiency and generation quality. Research into conditional graph generation is driven by numerous applications, including molecular design, material science, and social network analysis, where the ability to generate graphs matching specific requirements is crucial.

Asymmetric Flows#

The concept of “Asymmetric Flows” in the context of a research paper likely refers to a model or system where different components or processes have unequal roles or contributions. This asymmetry might manifest in various ways, such as differing levels of influence, unequal treatment of information, or variable degrees of impact on the overall outcome. For instance, in a generative model, one flow might be primarily responsible for generating the overall structure, while others might add details or refine specific features. The asymmetry can enhance the model’s expressive power and allow for a more nuanced and efficient generation process, as opposed to a symmetric approach where all components share equivalent weight. Analyzing asymmetric flows requires considering how the different parts interact, what information each part prioritizes, and the overall impact of this unequal distribution on system dynamics and results. Understanding these asymmetries is crucial for interpreting the model’s behavior and gaining insight into the underlying mechanisms of the generation process.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for conditional graph generation models could explore more sophisticated guidance mechanisms beyond simple classifier-based or classifier-free approaches. This could involve developing methods that explicitly model the interactions between different graph properties or that incorporate external knowledge sources to guide the generation process. Another area of focus could be on improving the efficiency and scalability of existing methods, particularly for large or complex graphs. This includes research on new architectures and training techniques that reduce computational costs while maintaining or improving performance. Furthermore, investigation into novel applications of conditional graph generation is warranted. While existing applications are promising, exploring new domains like material science, drug discovery, and biological systems modeling could unlock significant new advancements. Finally, there is a need for more rigorous evaluation metrics that accurately capture the quality and utility of generated graphs, going beyond simple structural similarity metrics. Developing metrics that consider graph properties, functionality, and other relevant characteristics will provide a more comprehensive understanding of the model’s capabilities and limitations. Addressing these future directions will advance conditional graph generation towards increasingly realistic and practical graph generation models.

More visual insights#

More on figures

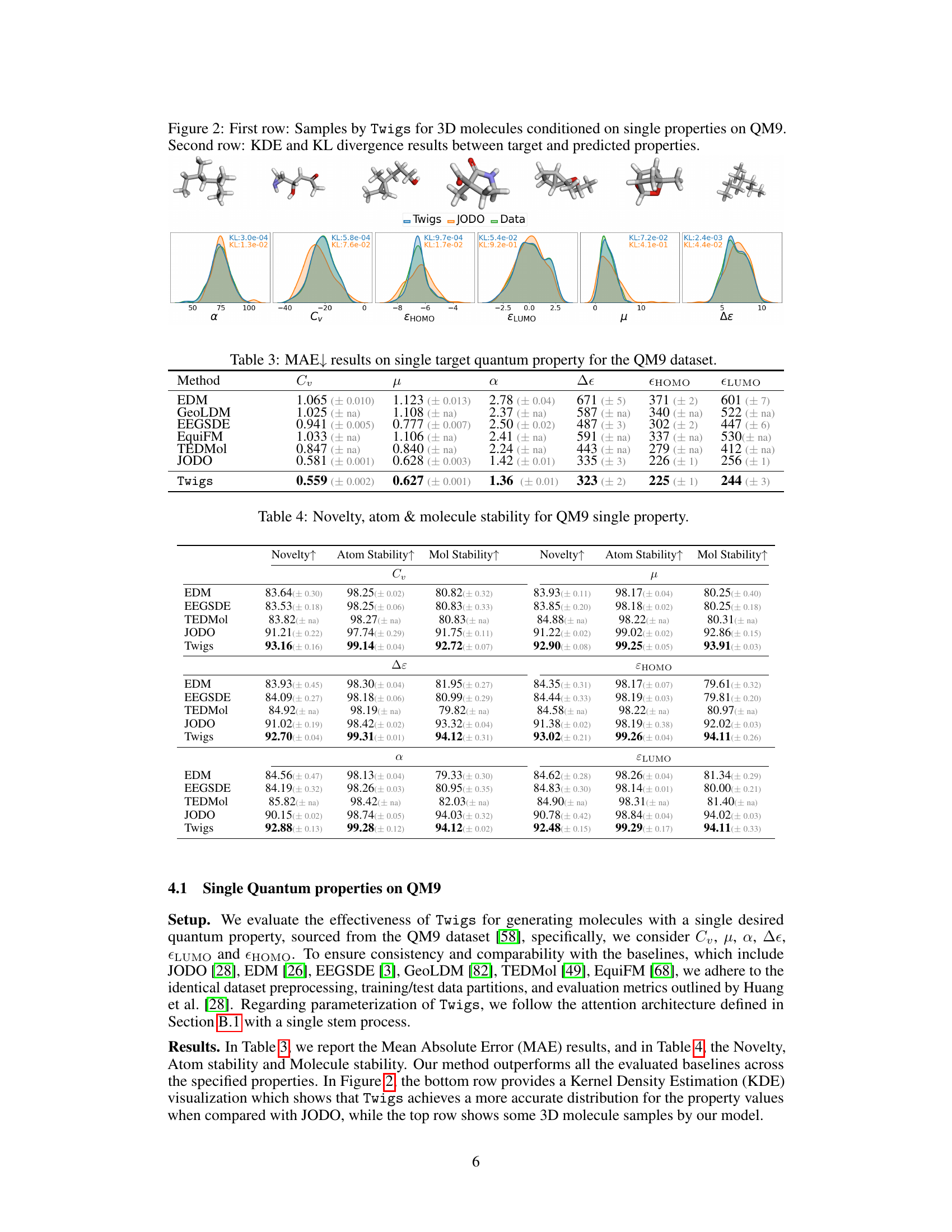

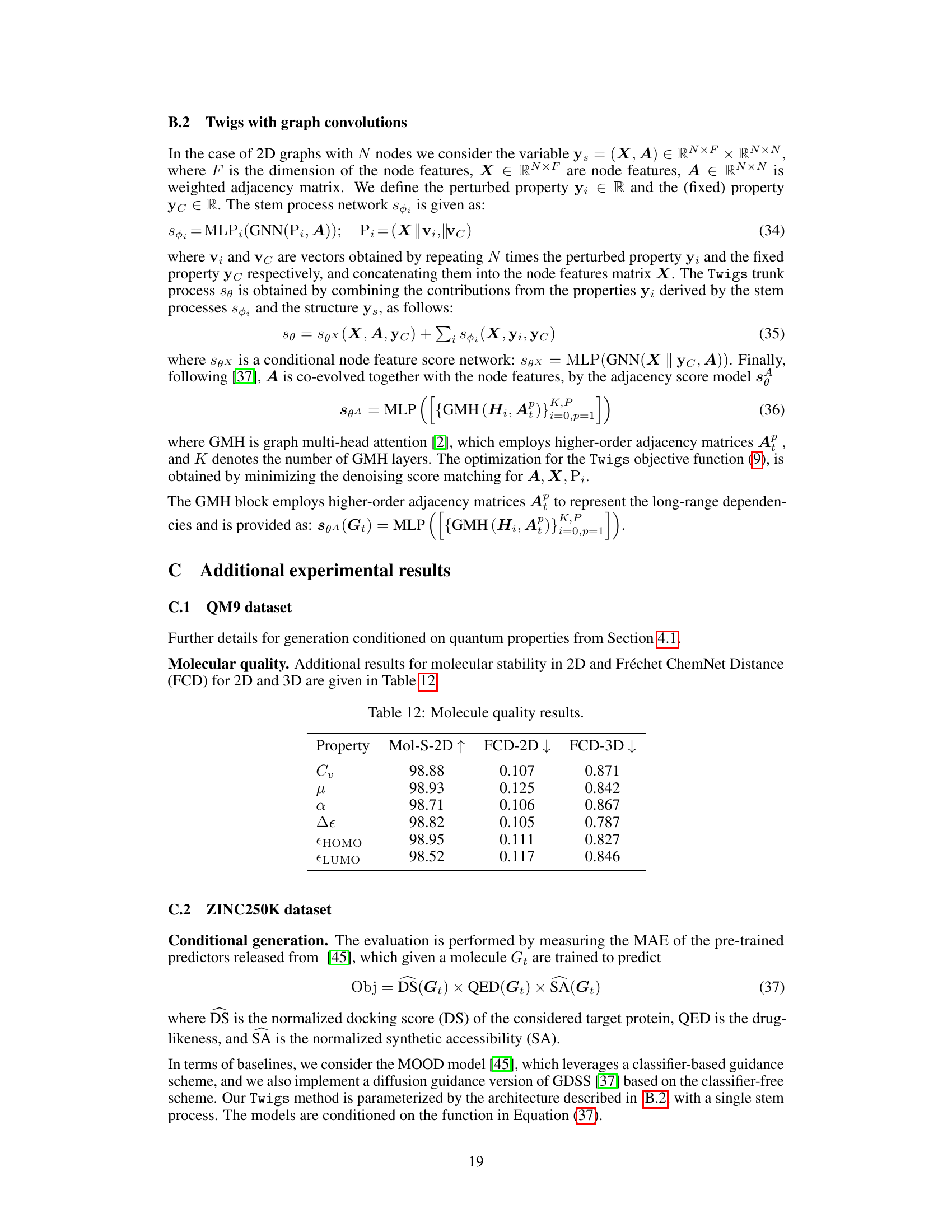

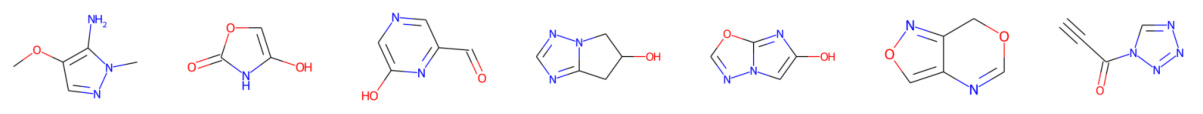

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of generating 3D molecules using the Twigs model, conditioned on individual quantum properties from the QM9 dataset. The top row displays example molecules generated by Twigs, showcasing the model’s ability to generate diverse structures based on specific property constraints. The bottom row presents Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) plots comparing the distribution of predicted properties by Twigs with those from the actual data. KL divergence values quantify the difference between the two distributions for each property, providing a measure of the model’s accuracy in generating molecules with the desired properties.

read the caption

Figure 2: First row: Samples by Twigs for 3D molecules conditioned on single properties on QM9. Second row: KDE and KL divergence results between target and predicted properties.

🔼 This figure shows the results of the Twigs model for generating 3D molecules with a single desired quantum property. The first row displays examples of the generated molecules, demonstrating the model’s ability to generate diverse structures. The second row presents Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) plots and Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence values, which measure the discrepancy between the target and predicted properties. The KDE plots visually compare the probability distribution of the predicted property to the target, while the KL divergence quantifies the difference between these distributions. Lower KL divergence values indicate that the model is better at predicting the desired property. Overall, the figure showcases the model’s ability to generate realistic and accurate molecules with specified properties.

read the caption

Figure 2: First row: Samples by Twigs for 3D molecules conditioned on single properties on QM9. Second row: KDE and KL divergence results between target and predicted properties.

🔼 This figure shows the results of generating 3D molecules using the Twigs model, conditioned on single quantum properties from the QM9 dataset. The top row displays example molecules generated by Twigs for different properties (Cv, μ, α, Δε, EHOMO, ELUMO). The bottom row presents a comparison of the predicted property distributions (using Kernel Density Estimation, KDE) with the actual target distributions for each property. KL divergence values quantify the difference between the predicted and target distributions, indicating the accuracy of the model’s predictions.

read the caption

Figure 2: First row: Samples by Twigs for 3D molecules conditioned on single properties on QM9. Second row: KDE and KL divergence results between target and predicted properties.

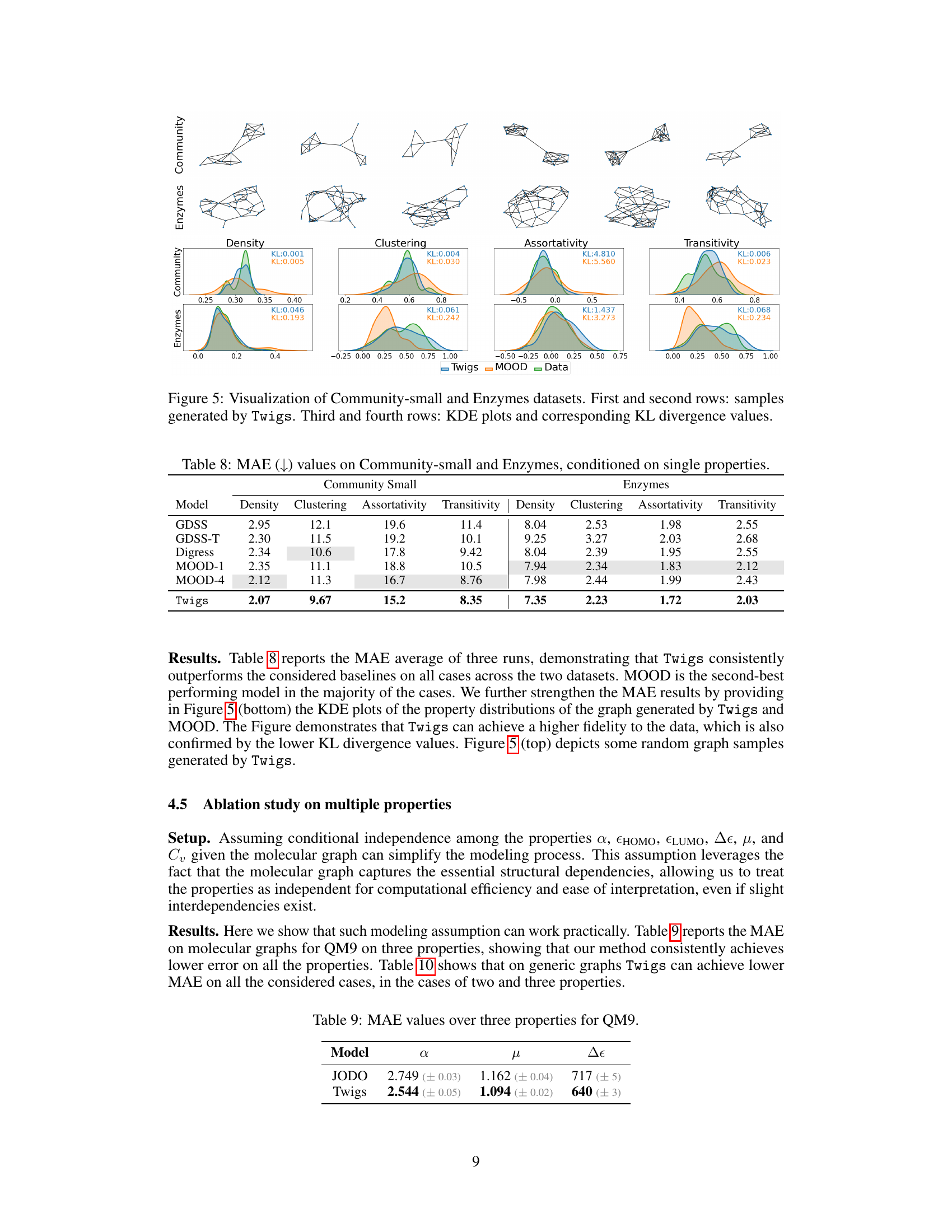

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of applying the Twigs model to the Community-small and Enzymes datasets. The top two rows show example graphs generated by Twigs for each dataset. The bottom two rows present Kernel Density Estimation (KDE) plots, comparing the distributions of four graph properties (Density, Clustering, Assortativity, and Transitivity) generated by Twigs and MOOD against the true data distributions. The KL divergence values quantify the difference between the generated and true distributions for each property.

read the caption

Figure 5: Visualization of Community-small and Enzymes datasets. First and second rows: samples generated by Twigs. Third and fourth rows: KDE plots and corresponding KL divergence values.

More on tables

🔼 The table compares Twigs against other related methods in terms of several key aspects: whether they handle conditional generation, whether they use asymmetric or symmetric processes, whether they use multiple flows, and whether they rely on continuous-time stochastic differential equations (SDEs). Twigs is highlighted as the first approach to seamlessly integrate multiple asymmetric property-oriented hierarchical diffusion processes through SDEs.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of related methodologies. Twigs is the first method that enables a seamless orchestration of multiple asymmetric property-oriented hierarchical diffusion processes via SDEs.

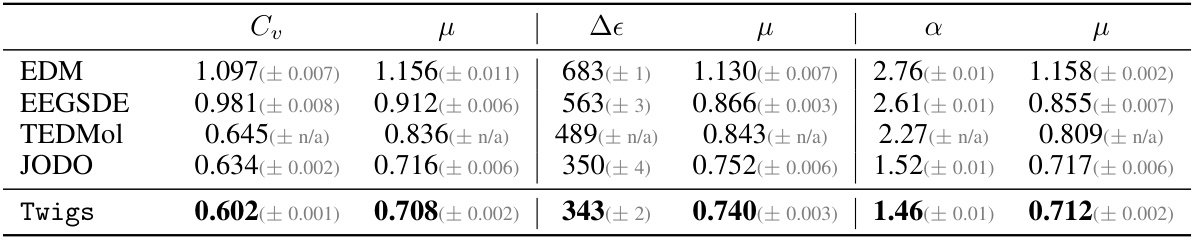

🔼 This table presents the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for various machine learning models in predicting single target quantum properties for molecules in the QM9 dataset. Lower MAE values indicate better performance. The models compared include EDM, GeoLDM, EEGSDE, EquiFM, TEDMol, JODO, and the proposed Twigs method. The properties predicted are Cv, μ, α, Δε, εHOMO, and εLUMO.

read the caption

Table 3: MAE↓ results on single target quantum property for the QM9 dataset.

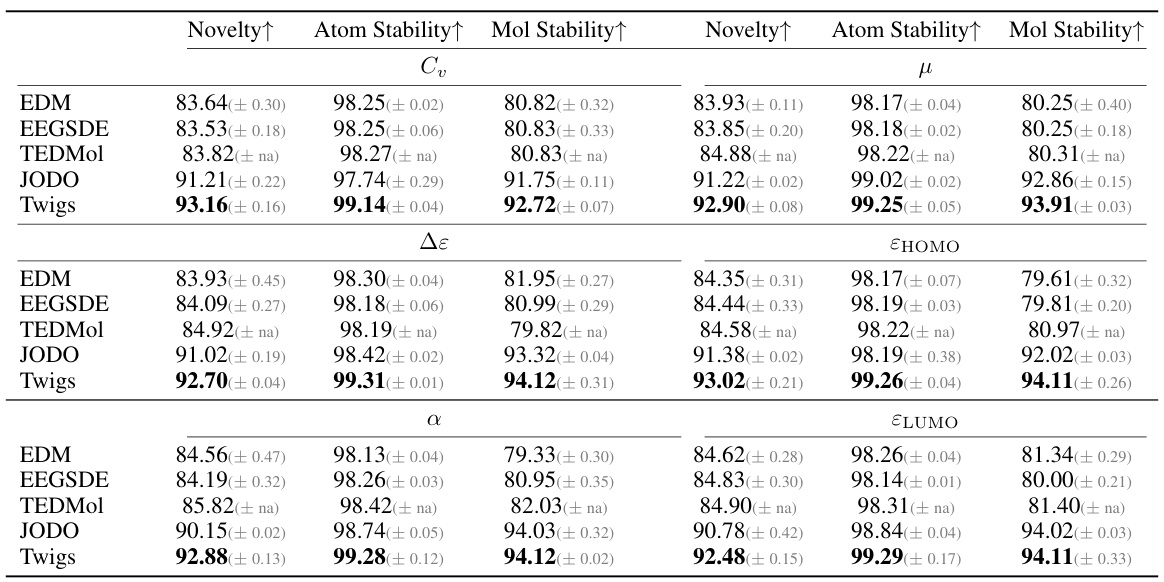

🔼 This table presents the results of evaluating the novelty, atom stability, and molecule stability for the QM9 dataset when generating molecules with a single desired quantum property. The metrics assess how well the generated molecules are novel (different from existing molecules), how stable the atom configurations are, and how stable the overall molecular structures are. The table compares the performance of the proposed Twigs method against several baselines (EDM, EEGSDE, TEDMol, and JODO) across six different quantum properties (Cv, μ, Δε, α, εHOMO, and εLUMO).

read the caption

Table 4: Novelty, atom & molecule stability for QM9 single property.

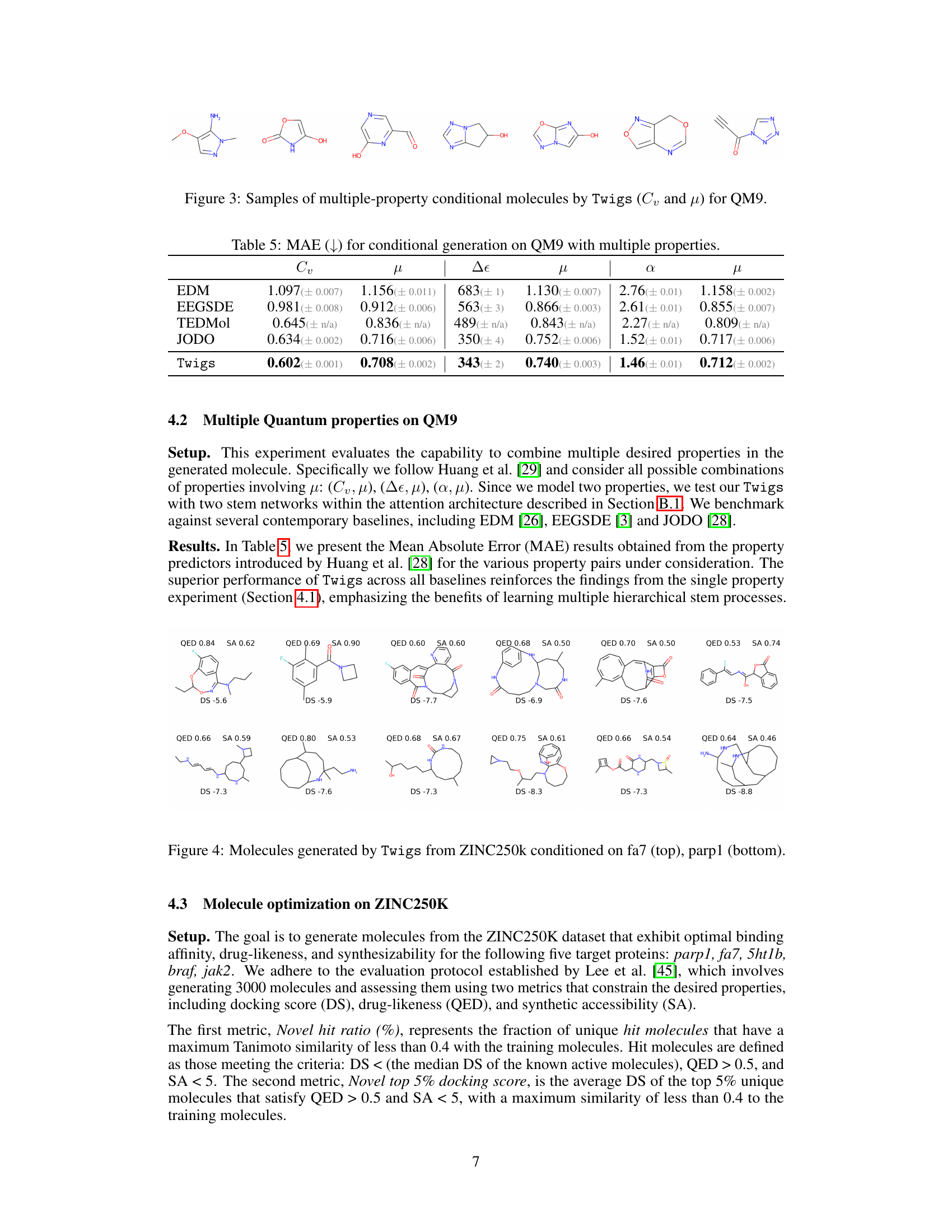

🔼 This table presents the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) results for generating molecules with multiple desired properties on the QM9 dataset. It compares the performance of Twigs against several baselines (EDM, EEGSDE, TEDMol, JODO) across different combinations of properties (Cv, μ, Δε, α, ELUMO, μ). Lower MAE values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 5: MAE (↓) for conditional generation on QM9 with multiple properties.

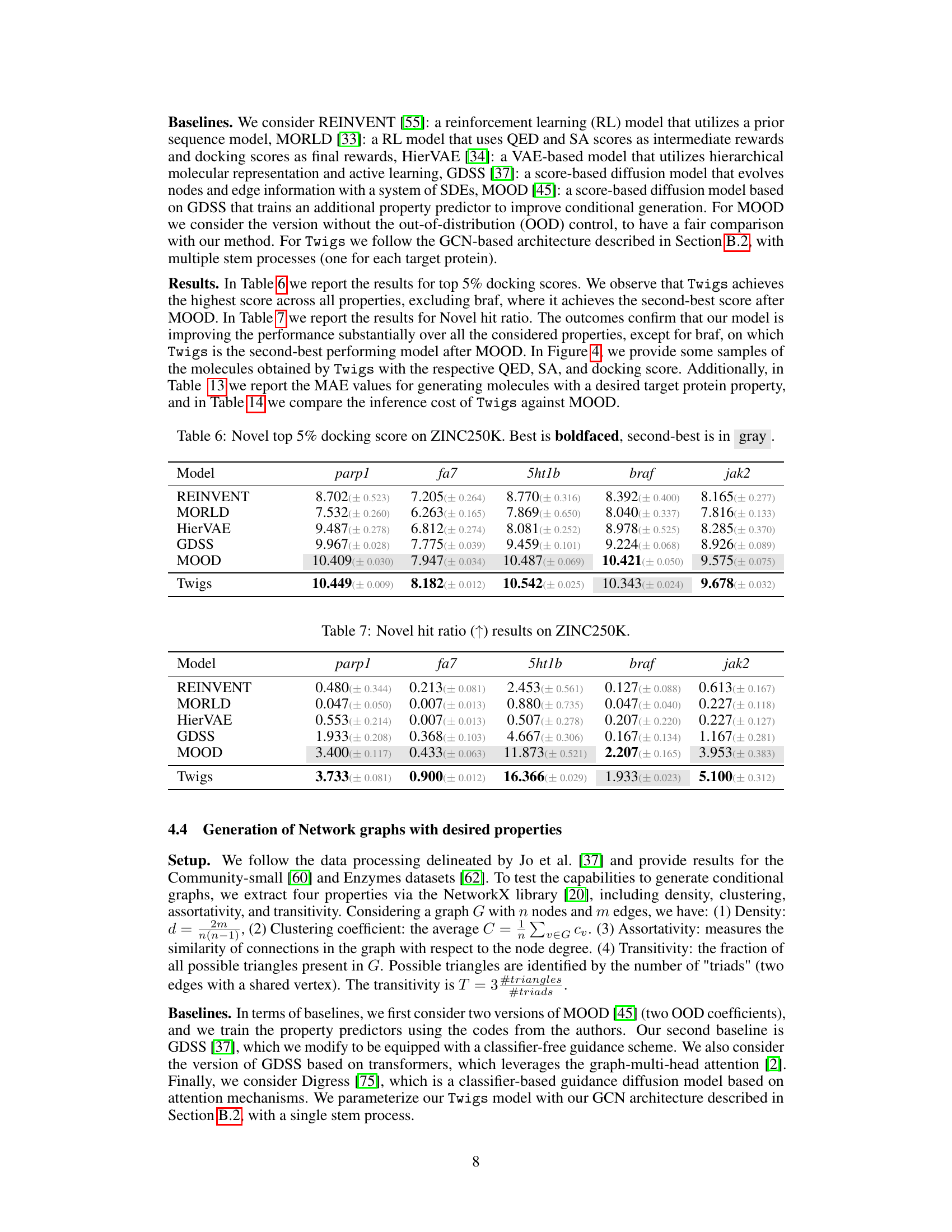

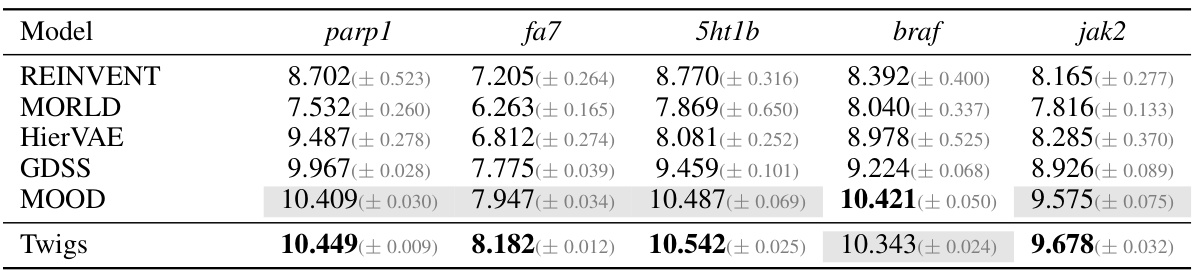

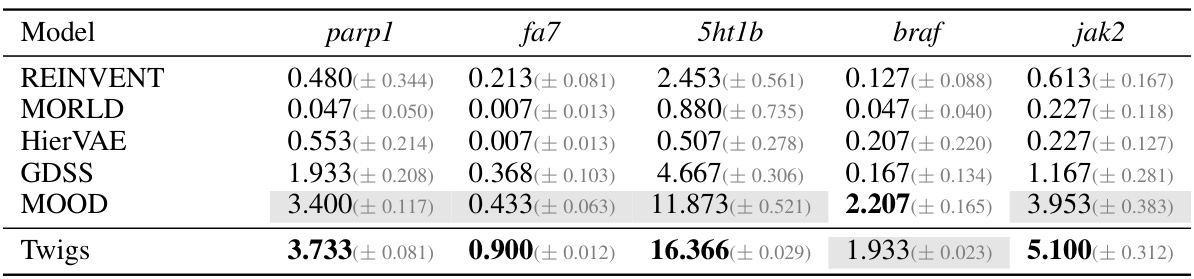

🔼 This table presents the results of the novel top 5% docking score on the ZINC250K dataset. The results are compared across different models (REINVENT, MORLD, HierVAE, GDSS, MOOD, and Twigs). The best performing model for each target protein (parp1, fa7, 5ht1b, braf, and jak2) is shown in bold, while the second best is highlighted in gray. This table shows that Twigs performs very well against other existing methods and provides a robust evaluation of the model’s performance on a large and complex dataset.

read the caption

Table 6: Novel top 5% docking score on ZINC250K. Best is boldfaced, second-best is in gray

🔼 This table presents the results of the ‘Novel hit ratio’ metric on the ZINC250K dataset for molecule generation. The Novel hit ratio measures the percentage of unique molecules generated that have a Tanimoto similarity of less than 0.4 with the training molecules (molecules considered novel). Results are shown for five target proteins (parp1, fa7, 5ht1b, braf, jak2) and several models including REINVENT, MORLD, HierVAE, GDSS, MOOD, and Twigs. Higher values of Novel hit ratio indicate better performance in generating novel molecules.

read the caption

Table 7: Novel hit ratio (↑) results on ZINC250K.

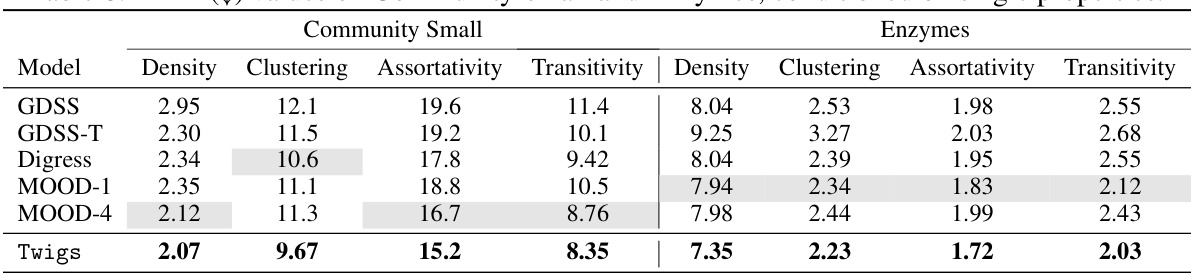

🔼 This table compares the performance of different models (GDSS, GDSS-T, Digress, MOOD-1, MOOD-4, and Twigs) on two datasets (Community Small and Enzymes) when generating graphs with a single desired property. Each model’s performance is evaluated using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for four different graph properties: Density, Clustering, Assortativity, and Transitivity. Lower MAE values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 8: MAE (↓) values on Community-small and Enzymes, conditioned on single properties.

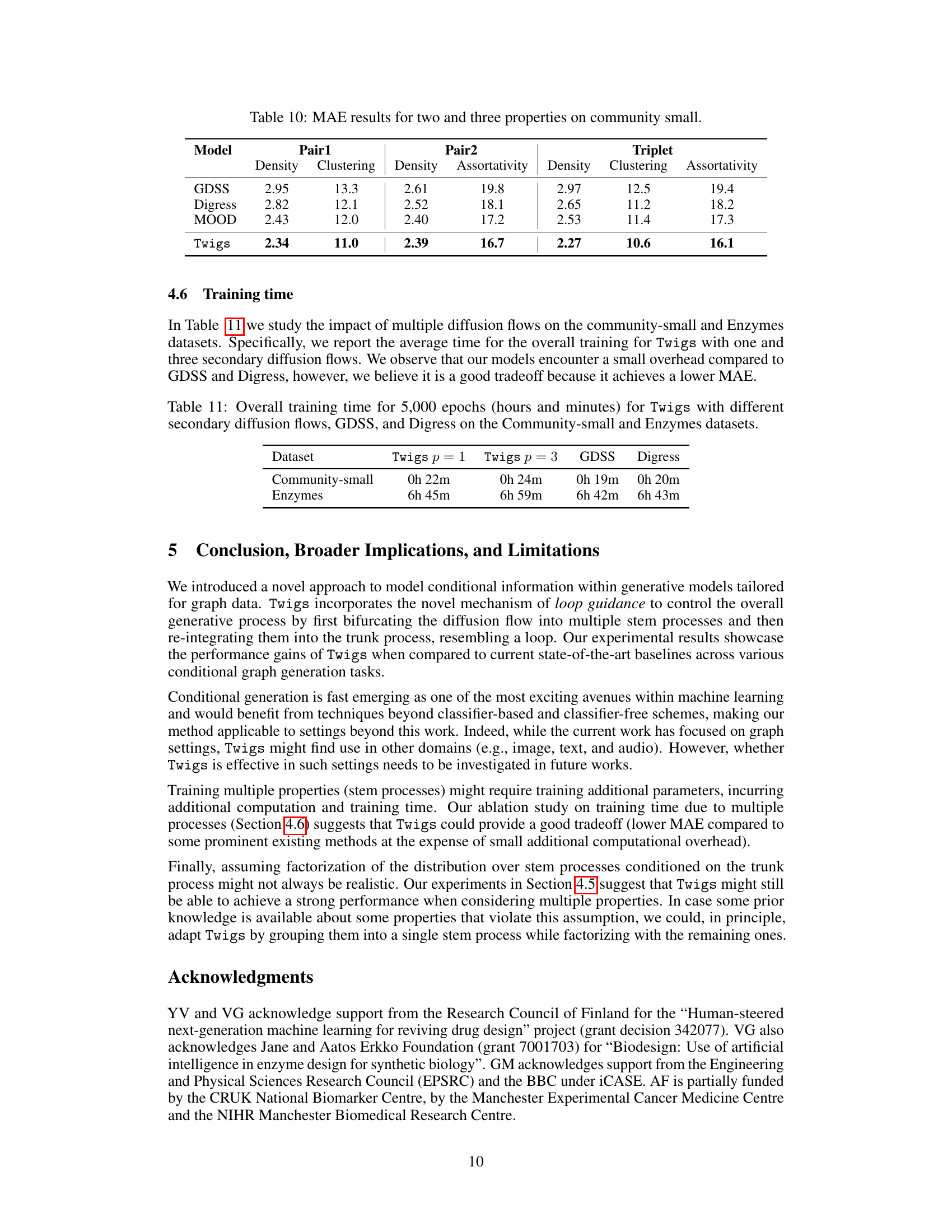

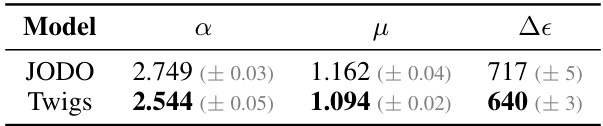

🔼 This table presents the Mean Absolute Error (MAE) results for three properties (α, μ, Δε) on the QM9 dataset. It compares the performance of the JODO and Twigs models, highlighting Twigs’ superior performance in achieving lower MAE values for all three properties.

read the caption

Table 9: MAE values over three properties for QM9.

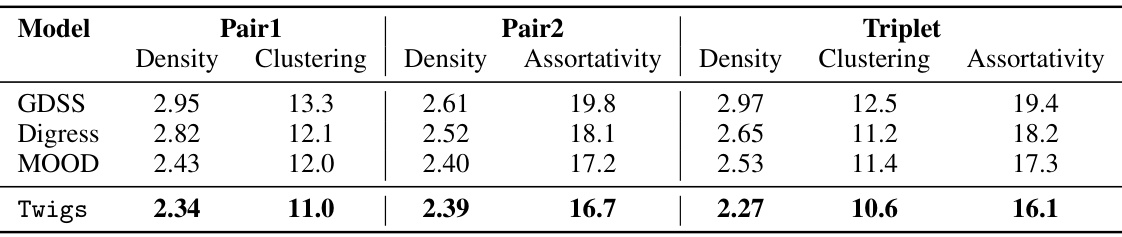

🔼 This table compares the performance of different models (GDSS, Digress, MOOD, and Twigs) on the Community-small dataset for predicting graph properties. Three different sets of properties are considered: Pair1 (Density and Clustering), Pair2 (Density and Assortativity), and Triplet (Density, Clustering, and Assortativity). The MAE (Mean Absolute Error) for each model and property pair is reported. Lower MAE values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 10: MAE results for two and three properties on community small.

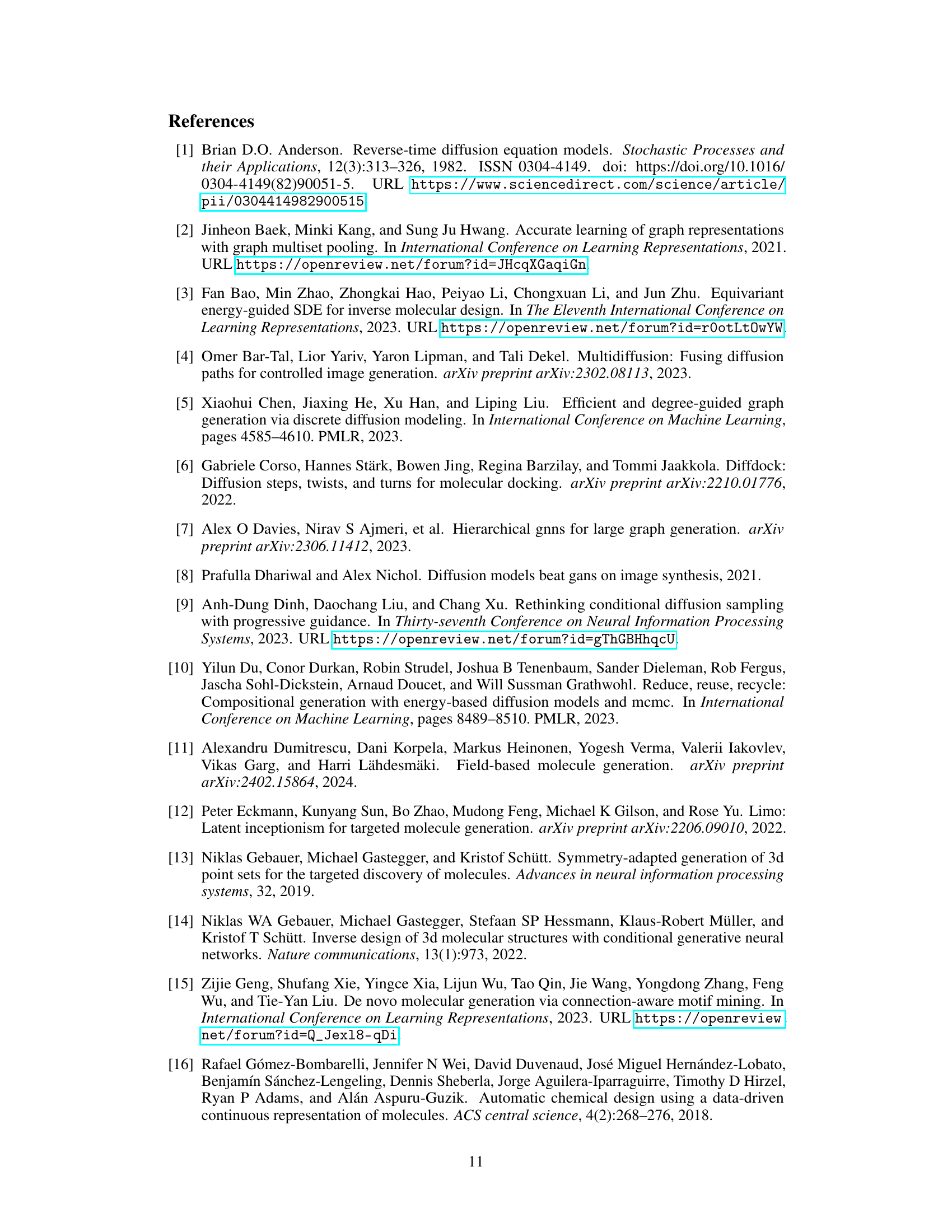

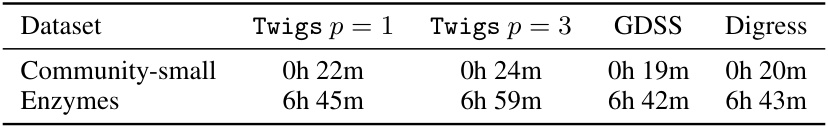

🔼 This table shows the training time taken for different models (Twigs with 1 and 3 secondary diffusion flows, GDSS, and Digress) on two datasets (Community-small and Enzymes) for 5000 epochs. It allows for comparison of the computational cost of the proposed method (Twigs) against existing methods.

read the caption

Table 11: Overall training time for 5,000 epochs (hours and minutes) for Twigs with different secondary diffusion flows, GDSS, and Digress on the Community-small and Enzymes datasets.

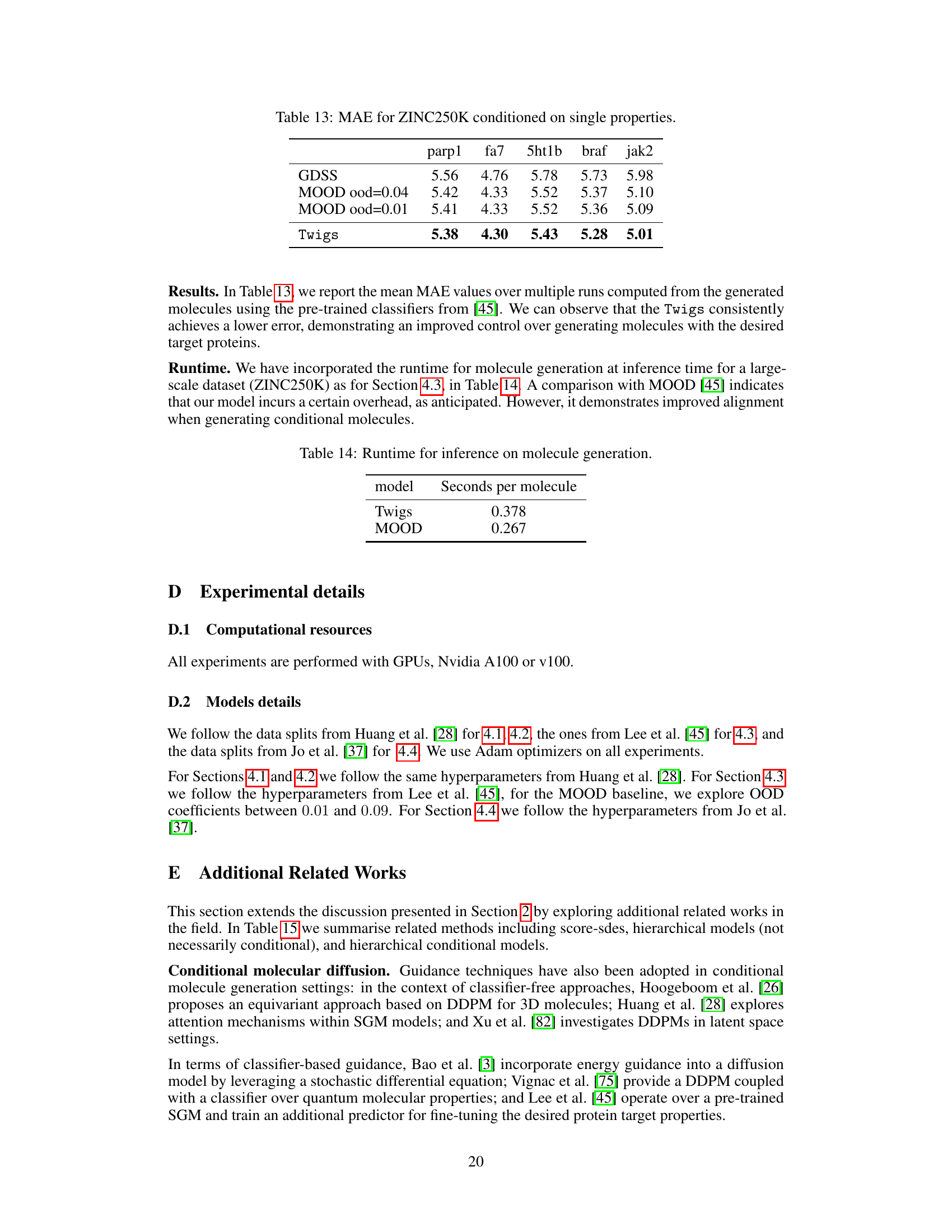

🔼 This table presents additional results for molecular stability in 2D and Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD) for 2D and 3D. It shows the performance of the Twigs model on different molecular properties (Cv, μ, α, Δε, εHOMO, εLUMO), quantified by the Mol-S-2D (higher is better), FCD-2D (lower is better), and FCD-3D (lower is better) metrics. These metrics evaluate the quality of generated molecules in terms of their structural stability and similarity to real-world molecules.

read the caption

Table 12: Molecule quality results.

🔼 This table presents the results of the novel top 5% docking score on the ZINC250K dataset. The best performing model for each target protein is shown in bold, while the second-best is highlighted in gray. The table compares the performance of Twigs against several other methods (REINVENT, MORLD, HierVAE, GDSS, MOOD). It showcases Twigs’ superior performance in most cases, emphasizing its effectiveness in molecule optimization tasks.

read the caption

Table 6: Novel top 5% docking score on ZINC250K. Best is boldfaced, second-best is in gray

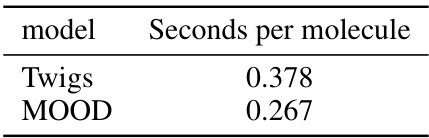

🔼 This table compares the inference time per molecule for the Twigs model and the MOOD model. The results show that Twigs takes slightly longer (0.378 seconds) than MOOD (0.267 seconds) to generate a single molecule.

read the caption

Table 14: Runtime for inference on molecule generation.

🔼 This table compares Twigs with several related methods in terms of their use of conditional generation, asymmetric processes, multiple flows, and continuous SDEs. It highlights that Twigs uniquely combines all of these features, making it a novel approach to conditional graph generation.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of related methodologies. Twigs is the first method that enables a seamless orchestration of multiple asymmetric property-oriented hierarchical diffusion processes via SDEs.

Full paper#