TL;DR#

Current self-supervised learning (SSL) methods often struggle with the complex dynamics of video data, resulting in representations that are less robust to noise and perturbations. Many prioritize invariance, losing valuable temporal information. The problem is that many standard methods for video analysis are not robust and struggle to generalize well, limiting their real-world applications.

This research introduces a novel SSL approach that directly addresses this problem by explicitly optimizing for the “straightness” of temporal trajectories in the learned representations. By encouraging smoother, more linear representations, the method obtains significantly more robust neural embeddings that show improved performance on various tasks including object recognition and prediction, even surpassing previous invariance-based methods in tests with noisy or adversarial data. The key is a novel objective function that quantifies straightness and serves as a regularizer, which can be applied broadly to improve existing SSL techniques.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it introduces a novel self-supervised learning objective that enhances the robustness and predictability of neural representations in video processing. This directly addresses the challenges of handling complex spatiotemporal data and offers a new approach to improving the generalization of models in computer vision, relevant to researchers working on self-supervised learning, video analysis, and robust AI.

Visual Insights#

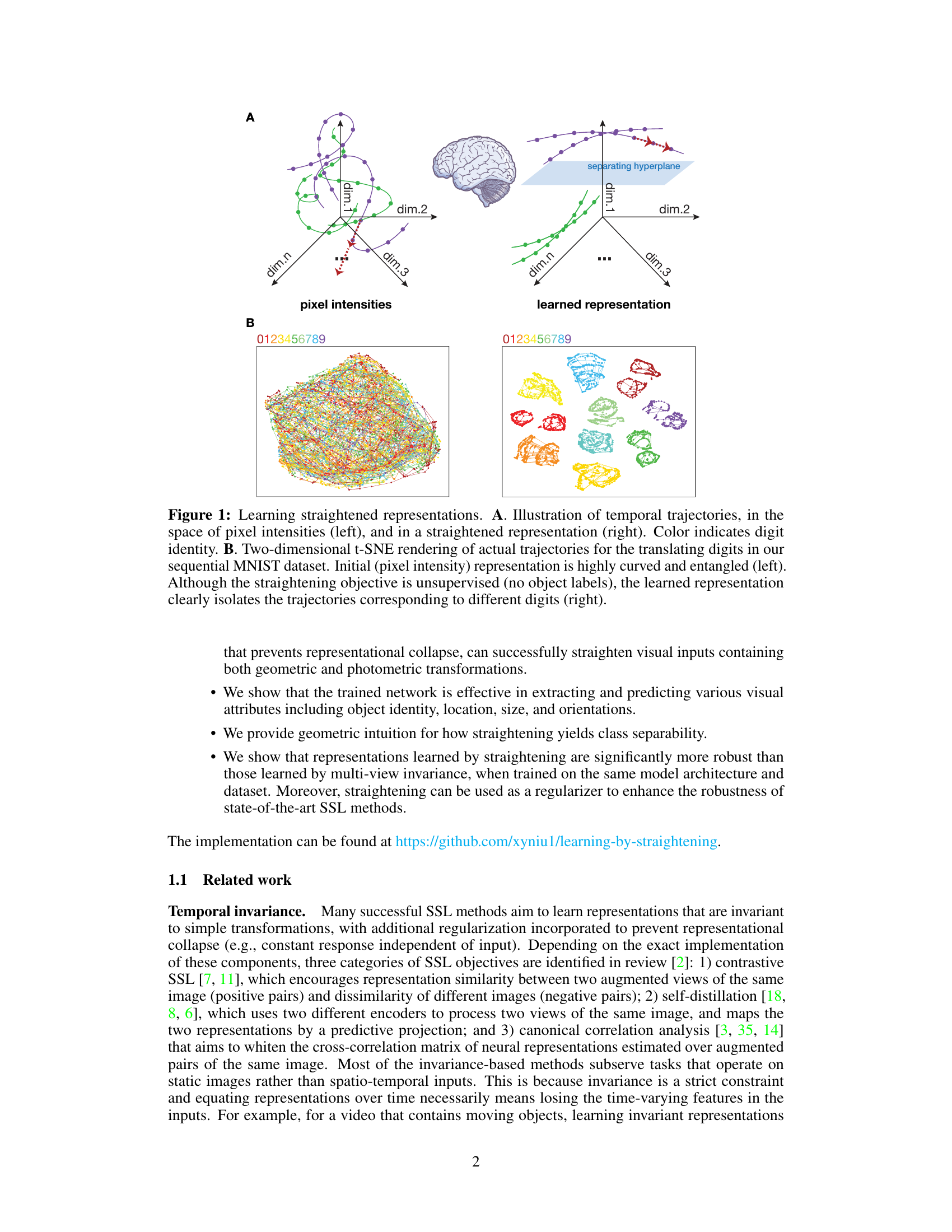

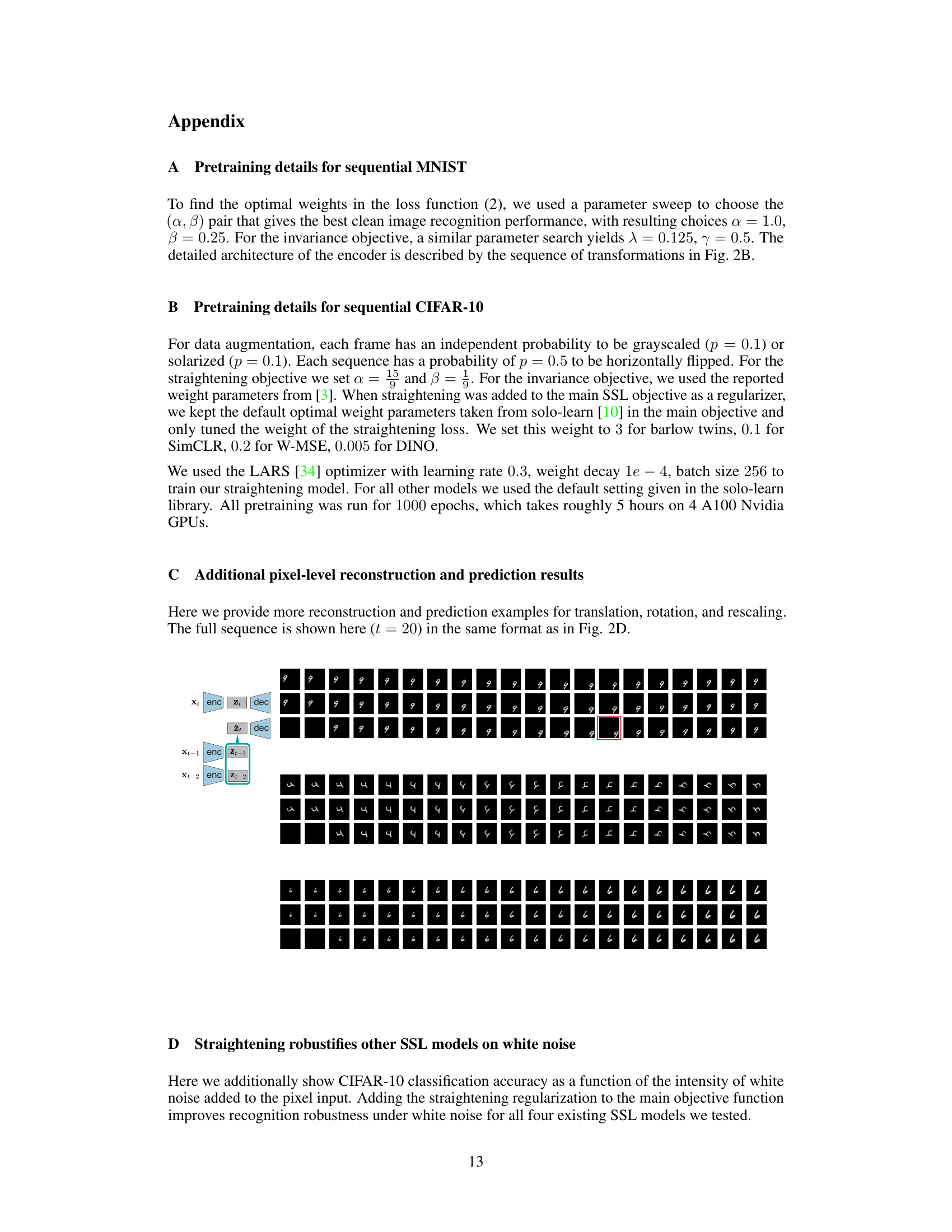

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of straightening in the context of learning visual representations from sequential data. Panel A shows how a sequence of image frames in pixel space (left) can be mapped to a lower-dimensional embedding space (right), where the trajectories are significantly straighter. Panel B provides a concrete example using a dataset of translating digits; the t-SNE plots demonstrate how curved and entangled initial trajectories in pixel space become more clearly separated in the straightened representation.

read the caption

Figure 1: Learning straightened representations. A. Illustration of temporal trajectories, in the space of pixel intensities (left), and in a straightened representation (right). Color indicates digit identity. B. Two-dimensional t-SNE rendering of actual trajectories for the translating digits in our sequential MNIST dataset. Initial (pixel intensity) representation is highly curved and entangled (left). Although the straightening objective is unsupervised (no object labels), the learned representation clearly isolates the trajectories corresponding to different digits (right).

In-depth insights#

Straightening SSL#

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) methods typically focus on learning invariant representations, ignoring temporal dynamics. Straightening SSL offers a novel approach by explicitly aiming for temporal trajectories in the learned representations that are straighter and more predictable. This is motivated by biological findings showing that primate visual systems process information in a way that facilitates prediction through linear extrapolation. The key benefit is enhanced robustness: straightened representations prove significantly more resistant to noise and adversarial attacks compared to invariance-based methods. This is because straightening encourages a more organized and separable representation space, leading to improved generalization. The approach introduces a novel objective function that quantifies and maximizes straightness, coupled with regularization techniques to prevent representational collapse. Furthermore, it can be applied as a regularizer to other SSL methods, suggesting broad utility and acting as a powerful regularizer for enhancing the robustness of existing SSL techniques. This makes straightening a potentially transformative principle in robust unsupervised learning.

Synthetic Video Data#

The use of synthetic video data in this research is a key strength, enabling precise control over data characteristics and facilitating a thorough investigation of the proposed straightening objective. The researchers cleverly generated artificial videos by applying structured transformations to static images from established datasets, rather than using complex and less controlled natural videos. This approach is methodologically sound, allowing them to isolate the impact of straightening on representation learning without confounding factors present in real-world videos. The resulting synthetic sequences mimic real-world properties, yet provide a standardized and repeatable experimental setup. The careful design of the synthetic videos, including the selection of transformations (translation, rescaling, rotation), and their controlled application over time, allows for rigorous evaluation of the straightening objective and comparison with more traditional invariance-based methods. The reliance on synthetic data does, however, introduce a potential limitation. The generalization of findings from synthetic data to real-world scenarios will require further testing with naturalistic video data.

Robustness Benefits#

The research demonstrates that the proposed straightening objective leads to significant robustness benefits in learned representations. Models trained with this objective exhibit superior resistance to both Gaussian noise and adversarial attacks compared to traditional invariance-based methods. This enhanced robustness is attributed to the straightening objective’s ability to capture predictable temporal structures in visual data, effectively disentangling and factoring geometric, photometric, and semantic information. Straightening’s predictive capacity allows for accurate extrapolations, making the learned representations more resilient to various corruptions. The improved robustness translates to enhanced performance across multiple image datasets and diverse evaluation metrics, highlighting straightening as a powerful regularization technique that can improve the reliability and generalizability of self-supervised learning models.

Geometric Intuition#

The concept of ‘Geometric Intuition’ in the context of a research paper about learning predictable and robust neural representations likely refers to visualizing and interpreting the learned representations in a geometric space. Instead of simply relying on numerical metrics, a geometric perspective helps in understanding the organization and separability of different classes or features. The authors might use techniques like t-SNE or UMAP to reduce the dimensionality of the learned embeddings and then visualize them as points in a lower-dimensional space. By examining the clustering of points and the distances between them, valuable insights about the relationships between different classes or features can be obtained. This approach provides a qualitative understanding that complements quantitative analysis and can reveal hidden structures not easily apparent in numerical data alone. A key aspect of this geometric approach would be the examination of trajectories through time for different input sequences. The ‘straightness’ of these trajectories becomes a crucial component. Straight trajectories imply that features are encoded in a linearly separable manner, facilitating easier prediction. This method might demonstrate that straightening facilitates class separability and could lead to the improved robustness of the model to noise and adversarial attacks, as straight lines are generally less sensitive to such perturbations than curved trajectories. In essence, geometric intuition provides a powerful tool to understand and visually interpret the effectiveness of the proposed straightening technique for robust unsupervised learning.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending the straightening objective to other modalities beyond vision, such as audio or sensorimotor data. Investigating the interplay between straightening and other self-supervised learning objectives is crucial, potentially leading to synergistic combinations that surpass individual methods’ performance. A deeper understanding of the underlying theoretical principles driving the success of straightening is also needed. Are there specific architectural properties or data characteristics that particularly benefit from this approach? Finally, applying straightening to more complex real-world scenarios, such as natural videos with highly nonlinear dynamics, would be a significant step towards demonstrating its practical utility for robust, unsupervised representation learning.

More visual insights#

More on figures

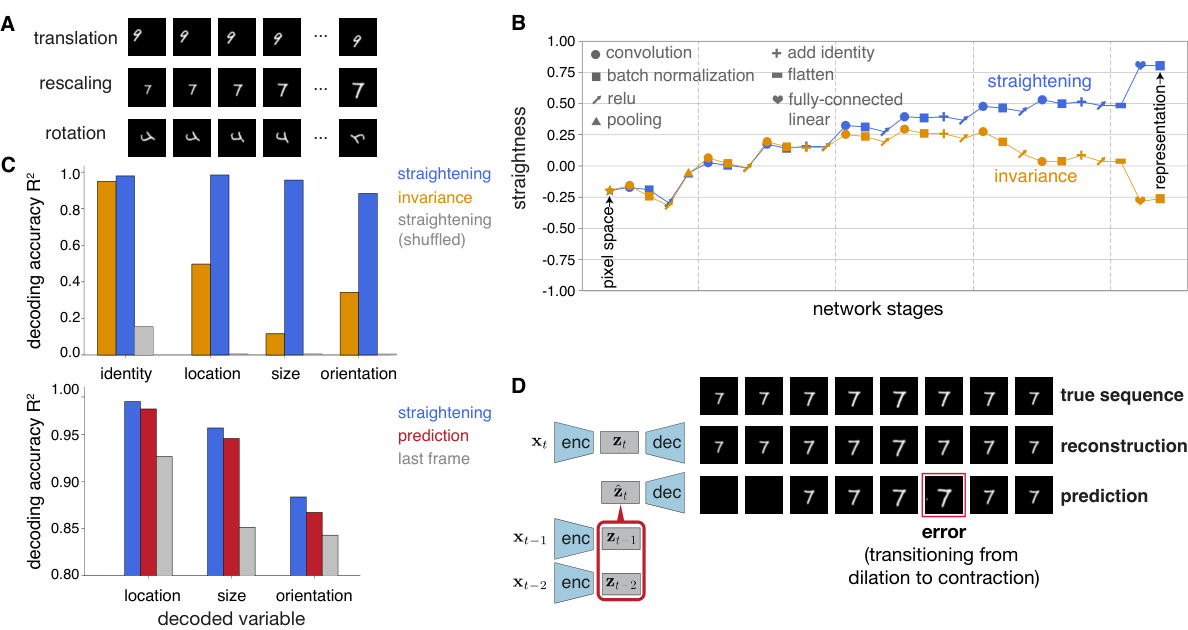

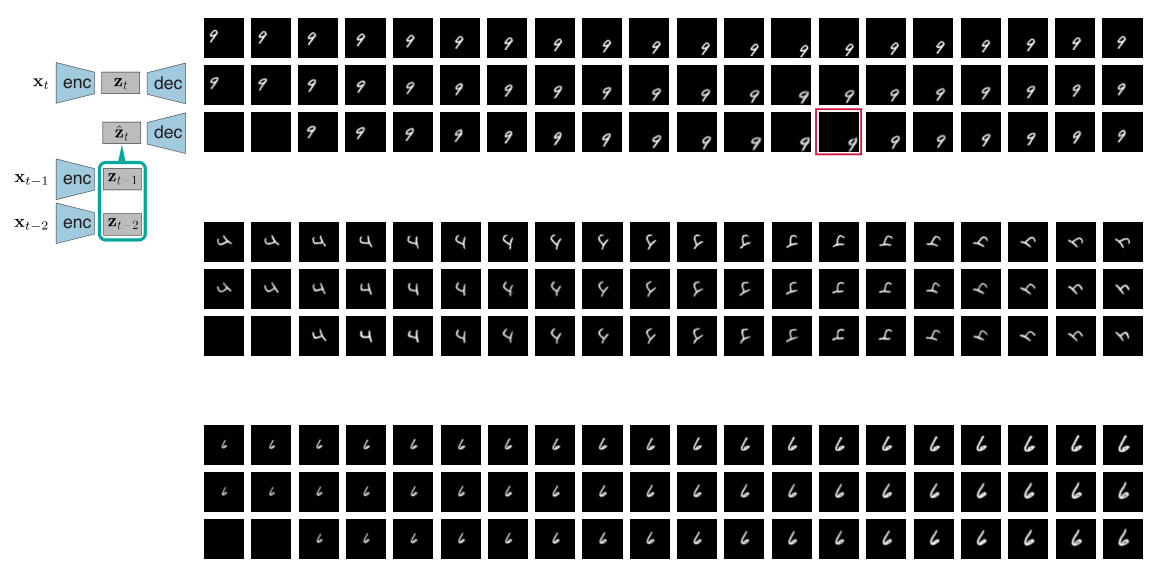

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the straightening objective in learning meaningful representations on the sequential MNIST dataset. Panel A shows examples of the three geometric transformations (translation, rescaling, rotation) used in the dataset. Panel B illustrates the increase in straightness across the different layers of the network, showing that the straightening objective successfully straightens the representations. Panel C shows the accuracy of decoding various variables from the network’s responses, both simultaneously and predictively. Panel D shows the network’s prediction capabilities, comparing reconstruction from simultaneous representation and predictions via linear extrapolation, highlighting the accuracy of the latter.

read the caption

Figure 2: Straightening and its benefits, evaluated on a network trained on sequential MNIST. A. Three example sequences, illustrating the three geometric transformations. B. Emergence of straightness throughout layers of network computation. C. Accuracy in decoding various (untrained) variables from the network responses (top). Accuracy in predicting/decoding variables at the next time step (bottom). Identitity not considered for prediction as it is constant over the sequence. D. Prediction capabilities of the network. Top: example sequence, with dilating/contracting digit. Middle: reconstructions from simultaneous representation. Bottom: predictions (linear extrapolation) based on the representation at the previous two time steps.

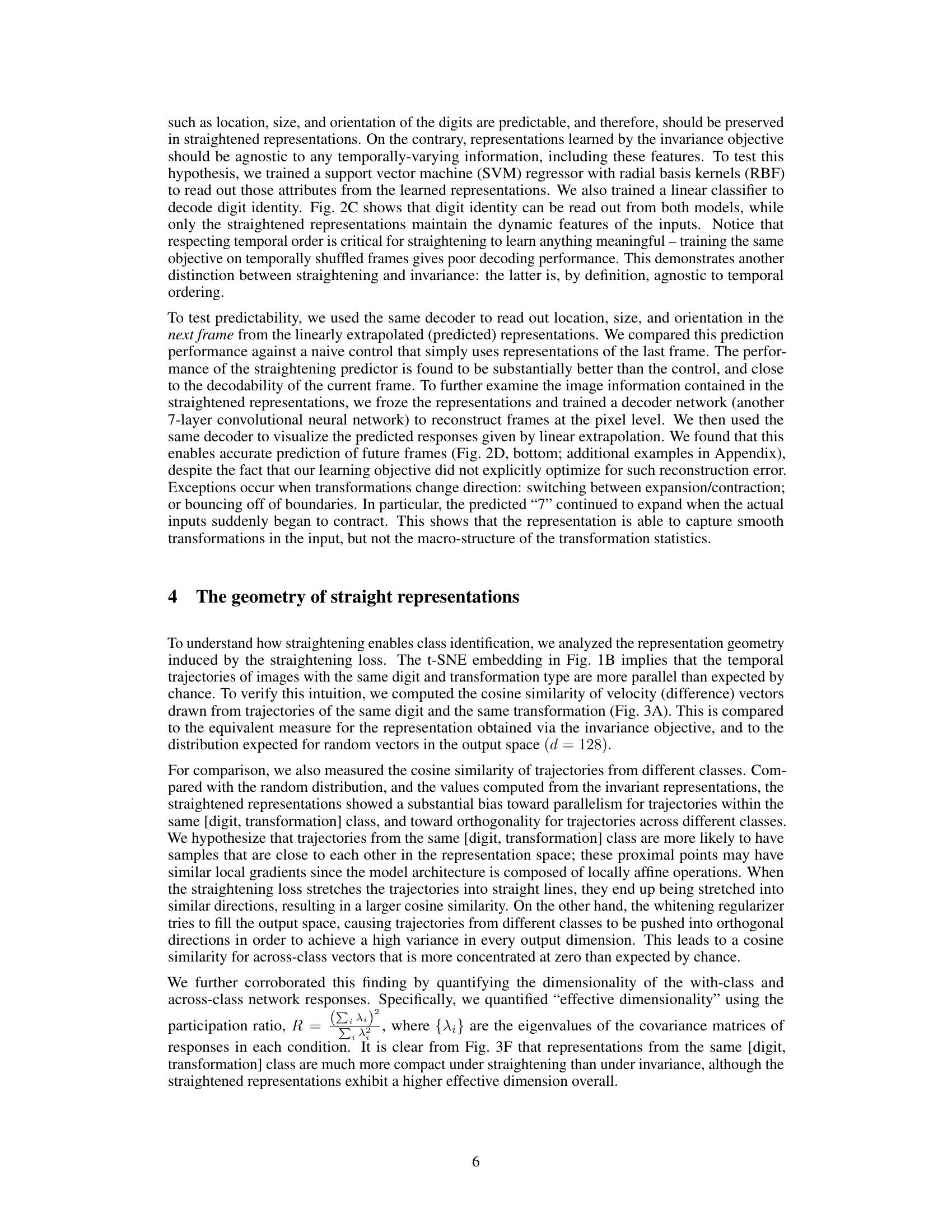

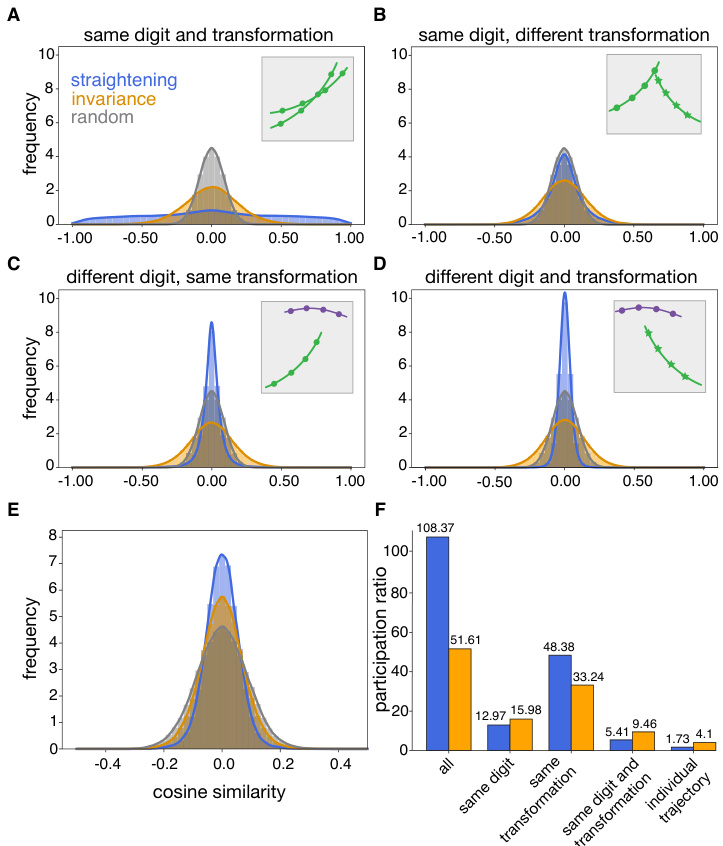

🔼 This figure displays the geometric properties of representations learned by the straightening objective function. Histograms of cosine similarity between successive difference vectors are presented to visualize the parallelism of trajectories for the same digit and transformation, and the orthogonality of trajectories across different digits and transformations. Example trajectories are shown in insets. Finally, the effective dimensionality of the responses is quantified by the participation ratio, showing how representations from the same class are more compact under straightening than under invariance.

read the caption

Figure 3: Geometric properties of the straightened representation. Panels A-E show histograms of cosine similarity (normalized dot product) between pairs of difference vectors, zt − zt−1. Insets show example trajectories in each scenario, where color indicates digit identity. A. same digit and transformation type; B. same digit and different transformation; C. different digit and same transformation; D. different digit and transformation; E. all difference vectors vs. digit classifier vectors. F. Average effective dimensionality, measured with participation ratio, of the set of responses zt in each group.

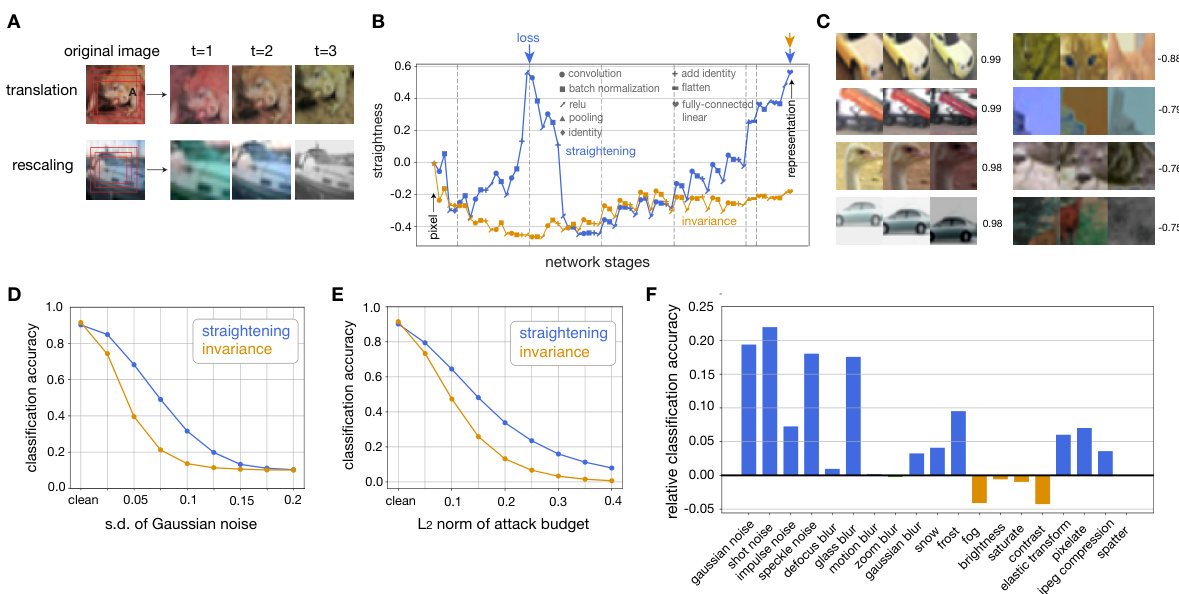

🔼 This figure demonstrates the impact of straightening on the robustness of the learned representations. It shows example synthetic sequences (A), the emergence of straightness through network layers (B), examples of successful and failed straightening (C), the impact of Gaussian noise on classification accuracy (D), adversarial attack robustness (E), and finally, a comparison of the relative classification accuracy of the straightened and invariance-trained networks under various degradations (F).

read the caption

Figure 4: Effect of straightening on representational robustness. A. Two example synthetic sequences from on sequential CIFAR-10 dataset. Top: translation and color shift. Bottom: rescaling (contraction) and color shift, last frame randomly grayscaled. B. Emergence of straightness throughout layers of network computation. Top arrows mark the stages of representation directly targeted for straightening (blue) and invariance (orange). C. Example sequences illustrating successes (left) and failures (right) of straightening. Numbers indicate straightness level ∈ [−1, 1]. D. Noise robustness: classification accuracy as a function of the amplitude of additive Gaussian noise injected in the input. E. Adversarial robustness: classification accuracy as a function of attack budget (see text). F. Relative classification accuracy of straightened network compared to invariance-trained network for various degradations. Color indicates the objective with better performance.

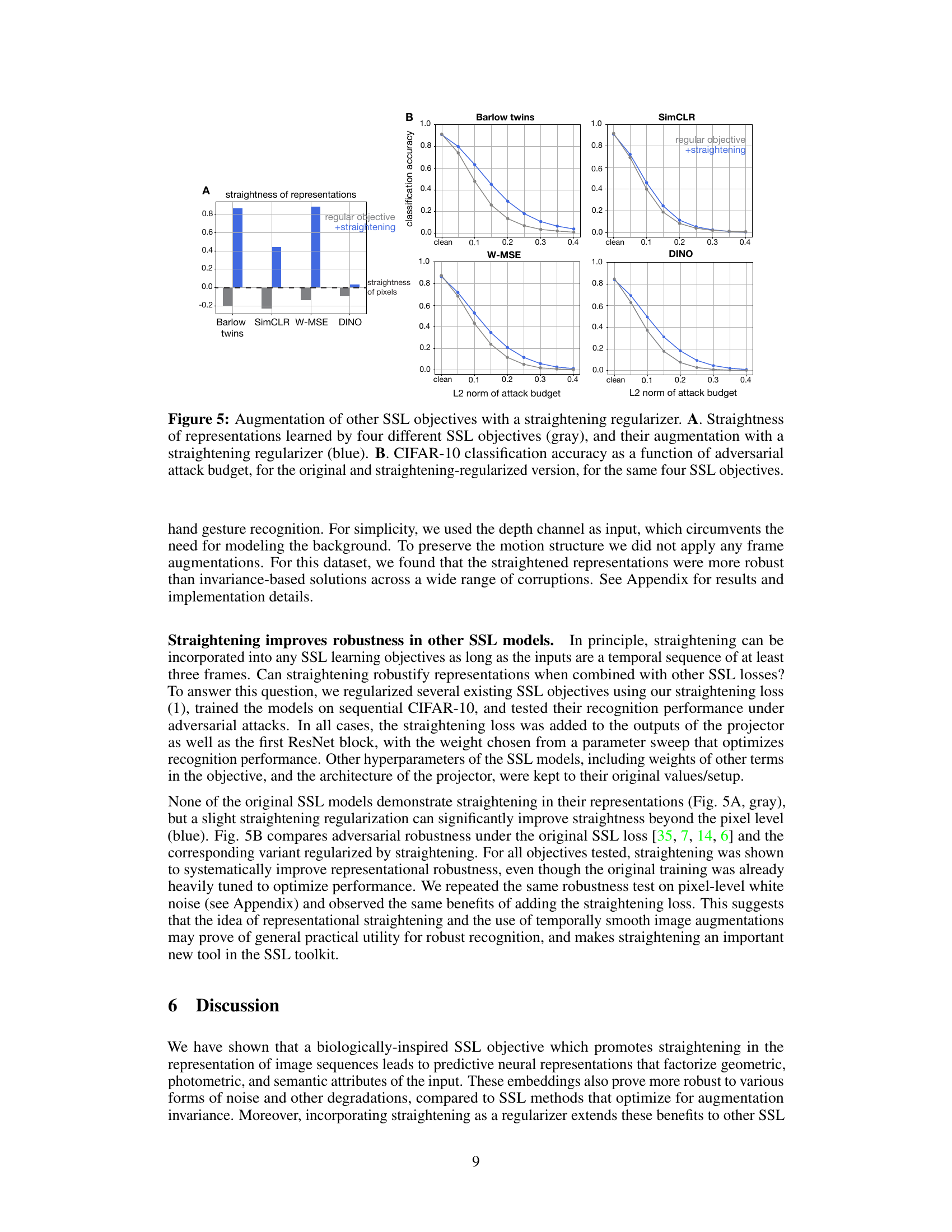

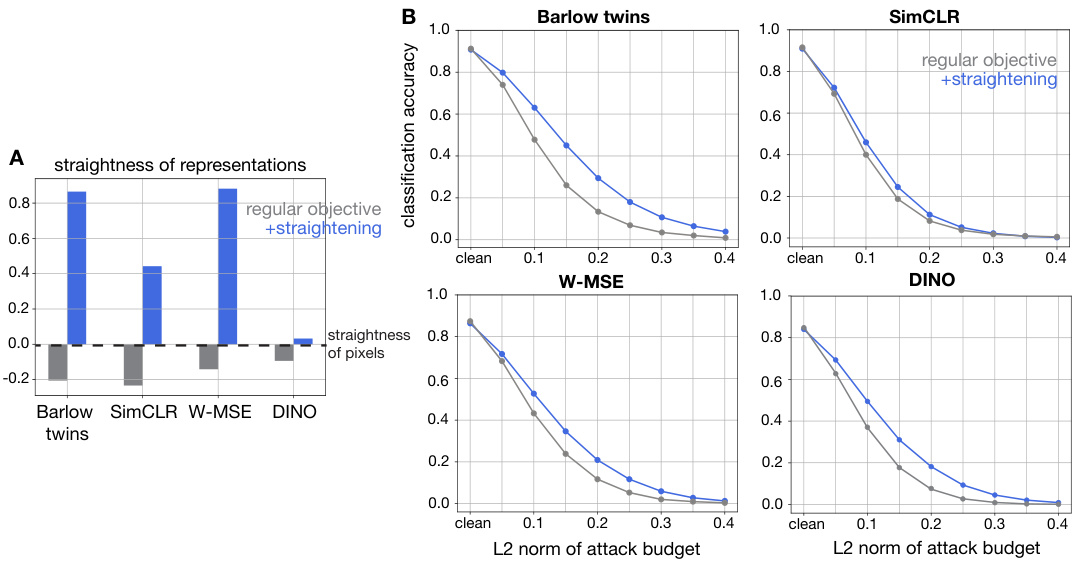

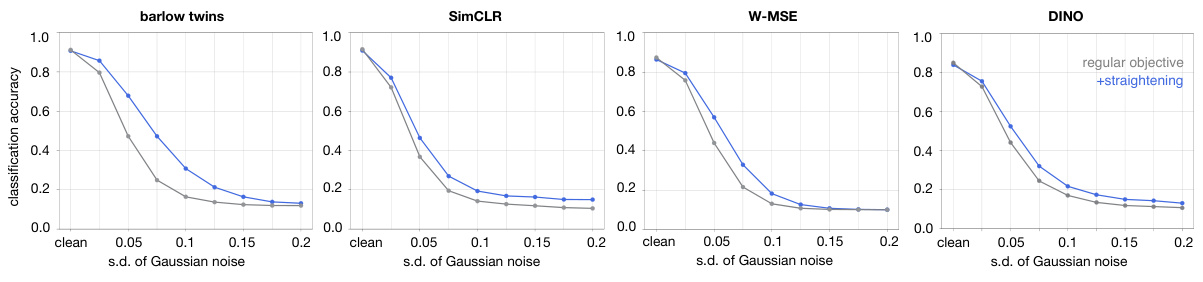

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effect of adding the straightening regularizer to four different self-supervised learning (SSL) objectives. Panel A shows that adding the straightening regularizer increases the straightness of the learned representations for all four SSL objectives. Panel B shows that adding the straightening regularizer improves the adversarial robustness of the learned representations for all four SSL objectives. The results suggest that straightening is a beneficial regularizer that can improve the performance of various SSL objectives.

read the caption

Figure 5: Augmentation of other SSL objectives with a straightening regularizer. A. Straightness of representations learned by four different SSL objectives (gray), and their augmentation with a straightening regularizer (blue). B. CIFAR-10 classification accuracy as a function of adversarial attack budget, for the original and straightening-regularized version, for the same four SSL objectives.

🔼 Figure 2 shows the results of the proposed straightening method applied to sequential MNIST dataset. (A) shows example sequences demonstrating three types of transformations: translation, rescaling, and rotation. (B) illustrates the increase in straightness across network layers during training using the proposed objective function, highlighting the effectiveness of the method. (C) demonstrates the accuracy of decoding various visual attributes (location, size, orientation) from the learned representations. The bottom part of (C) shows the accuracy of predicting future states of these attributes. (D) shows an example sequence (top) along with the simultaneous reconstructions (middle) from its learned representations and predictions based on linear extrapolation from the previous frames (bottom). The figure supports the main claim that the straightening objective leads to better representation that is more predictive and robust.

read the caption

Figure 2: Straightening and its benefits, evaluated on a network trained on sequential MNIST. A. Three example sequences, illustrating the three geometric transformations. B. Emergence of straightness throughout layers of network computation. C. Accuracy in decoding various (untrained) variables from the network responses (top). Accuracy in predicting/decoding variables at the next time step (bottom). Identitity not considered for prediction as it is constant over the sequence. D. Prediction capabilities of the network. Top: example sequence, with dilating/contracting digit. Middle: reconstructions from simultaneous representation. Bottom: predictions (linear extrapolation) based on the representation at the previous two time steps.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of adding a straightening regularizer to four different self-supervised learning (SSL) objectives. Panel A demonstrates that adding the regularizer increases the straightness of the resulting representations. Panel B shows that this added regularization improves the robustness of the resulting models against adversarial attacks, as measured by classification accuracy on the CIFAR-10 dataset.

read the caption

Figure 5: Augmentation of other SSL objectives with a straightening regularizer. A. Straightness of representations learned by four different SSL objectives (gray), and their augmentation with a straightening regularizer (blue). B. CIFAR-10 classification accuracy as a function of adversarial attack budget, for the original and straightening-regularized version, for the same four SSL objectives.

🔼 Figure 6 shows two subfigures. Subfigure A displays three example gesture sequences from the EgoGesture dataset. These sequences demonstrate different types of gestures, some of which can be easily classified from a single frame (e.g., ‘pause’), while others require observing multiple frames to understand the motion (e.g., ‘scroll hand backward’, ‘zoom in with fists’). Subfigure B presents a graph illustrating the robustness of gesture recognition under different levels of Gaussian noise. The graph compares the classification accuracy of models trained with the straightening objective (blue line) against those trained with the invariance objective (orange line). The x-axis represents the standard deviation of added Gaussian noise, while the y-axis shows the classification accuracy. The results indicate that the model trained using the straightening objective outperforms the invariance-trained model in terms of robustness against noise.

read the caption

Figure 6: A. Example gestures. Some gestures can be classified by a single frame (pause), while others must observe multiple frames to recognize the motion (scroll hand backward, zoom in with fists). B. Gesture recognition performance as a function of noise level.

Full paper#