TL;DR#

CLIP, a powerful vision-language model, struggles with images containing both text and visual elements; it often confuses textual and visual information. This can lead to misclassifications and unreliable results in tasks like image recognition and text extraction from images. Existing methods often rely on retraining with specific data or training strategies, which limits their general applicability and efficiency.

MirrorCLIP addresses this by introducing a novel zero-shot framework that disentangles textual and visual factors within CLIP using a simple yet elegant approach. It leverages the difference in the “mirror effect” between text and visual objects: when images are flipped, visual objects maintain their semantic meaning, while text typically becomes nonsensical. By comparing image features before and after flipping, MirrorCLIP generates a disentangling mask which separates textual and visual features. The effectiveness of this method is shown through various experiments, including visualization using CAM, image generation with stable diffusion, and typographic defense benchmarks, which show a significant improvement over existing methods.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it addresses a critical limitation of CLIP, a widely used vision-language model, by improving its robustness when handling images containing both text and visual objects. This is relevant to the growing field of multimodal learning and has implications for various applications like image captioning, visual question answering, and more. The proposed technique is simple yet effective, opening new avenues for enhancing the robustness and reliability of other vision-language models. The zero-shot nature of the method makes it particularly valuable for researchers, as it avoids the need for extensive retraining and offers a general solution.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure demonstrates the zero-shot prediction performance of CLIP on text-visual images before and after applying the proposed disentanglement method. Subfigure (a) shows the text recognition task, highlighting the misclassification of ’eraser’ as ’egg’ before disentanglement and the correct classification after disentanglement. Subfigure (b) shows the image recognition task, illustrating the misclassification of a dog as a cat before disentanglement and the accurate classification after disentanglement. The figure visually represents the effectiveness of the MirrorCLIP framework in disentangling textual and visual features, improving the accuracy of CLIP’s predictions on ambiguous inputs.

read the caption

Figure 1: The zero-shot prediction of CLIP before and after disentanglement, (a): prediction of text recognition, text of “eraser” is misclassified as “egg” before disentanglement, (b): prediction of image recognition, visual object of a dog is misclassified as a cat before disentanglement

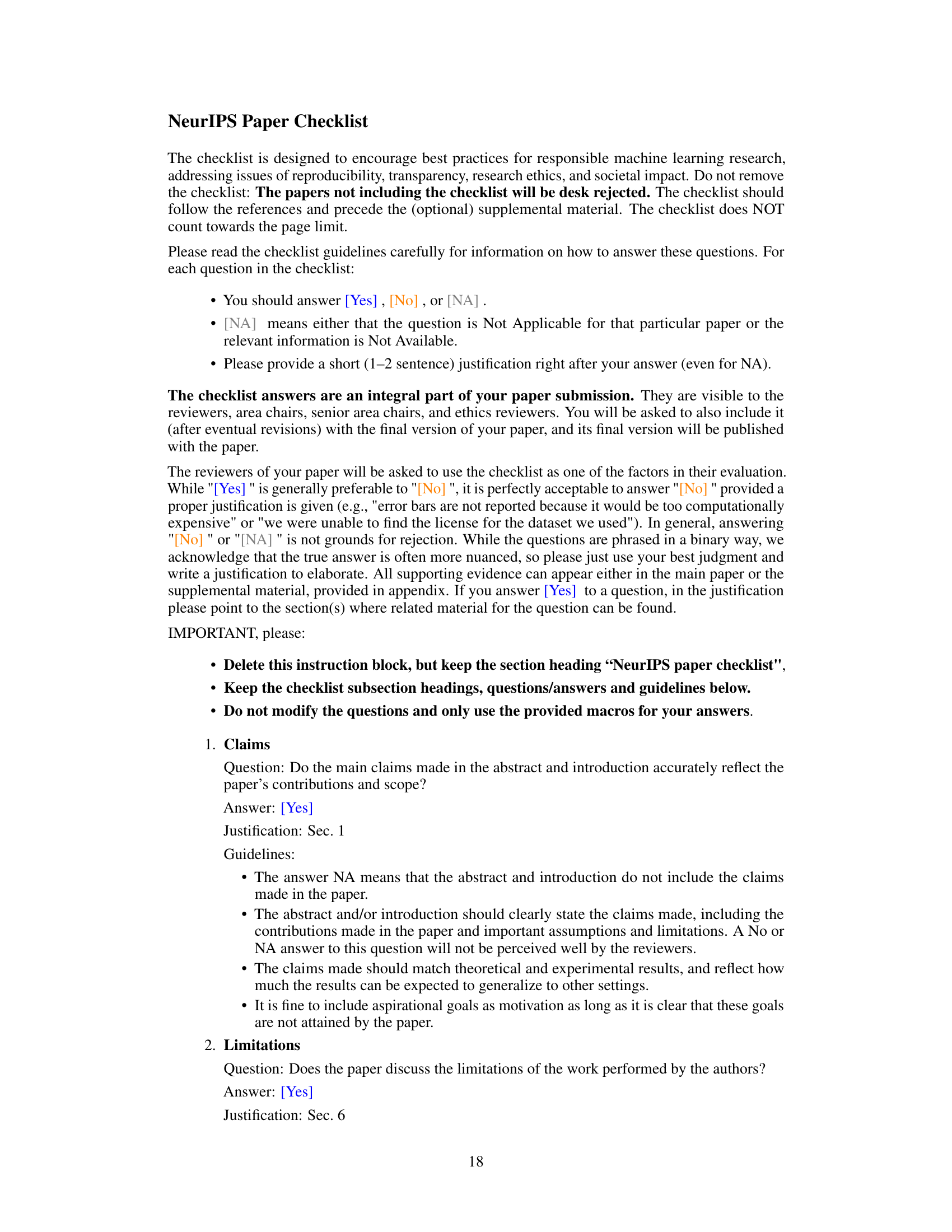

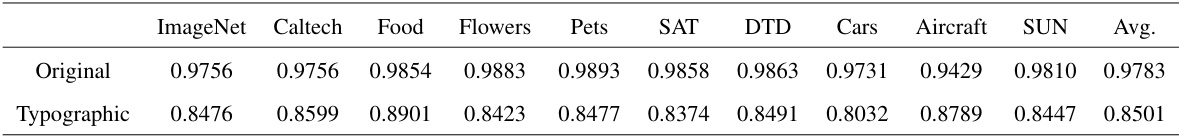

🔼 This table presents the cosine similarity results of image features before and after applying a horizontal flip operation. The data is separated into two groups: ‘Original’ representing images without added text, and ‘Typographic’ representing images with superimposed text, simulating a typographic attack. The cosine similarity values are calculated across ten different datasets (ImageNet, Caltech101, Food101, Flowers102, OxfordPets, EuroSAT, DTD, StanfordCars, FGVCAircraft, SUN397). Lower cosine similarity in the ‘Typographic’ set suggests that the presence of text significantly affects the horizontal flip invariance property of CLIP’s image feature representation, forming a basis for the proposed disentanglement method.

read the caption

Table 1: Cosine similarity of image features before and after flipping on Clean and Typographic datasets.

In-depth insights#

MirrorCLIP: Intro#

MirrorCLIP, as introduced in its introductory section, directly addresses the limitations of the CLIP network in handling text-visual images. CLIP’s struggles stem from its tendency to conflate textual and visual information, leading to misinterpretations. MirrorCLIP’s innovative approach leverages the inherent difference in how visual elements and text behave under a mirror reflection. Visual objects maintain their semantic meaning when flipped, while text becomes nonsensical. This core observation forms the foundation of MirrorCLIP’s zero-shot framework, a method designed to disentangle visual and textual features from the combined input without any need for additional training. This disentanglement is a key innovation, avoiding the need for retraining common to other similar approaches and thereby contributing to enhanced robustness and efficiency. The introduction likely highlights the practical implications of this work, showcasing MirrorCLIP’s potential to improve CLIP’s performance in scenarios involving text-visual images and strengthen its resistance to typographic attacks. The stage is set for a detailed explanation of the MirrorCLIP framework and its evaluation in subsequent sections.

Dual-Stream Disentanglement#

A dual-stream disentanglement approach in a research paper likely involves processing data (e.g., images) through two separate pathways to extract and separate different feature types. One stream might focus on visual features, while the other stream concentrates on textual features. This design is particularly useful when dealing with multimodal data containing both visual and textual information, such as images with text overlays. By processing the data in parallel and comparing the extracted features, the method aims to disentangle the intertwined visual and textual representations, leading to a more refined understanding of each modality individually. The effectiveness relies on the ability of the two streams to capture distinct aspects of the data and the subsequent integration or comparison process to separate them. This approach contrasts with single-stream methods that attempt to perform this separation within a unified framework, and often provides a more robust and accurate result. Applications would likely focus on tasks that benefit from separating visual and textual elements in multimodal data, such as image captioning, visual question answering, or typographic attack defense.

Visual Feature Robustness#

A robust visual feature representation is crucial for the success of any computer vision system. This section would delve into the ways that the proposed method enhances visual feature robustness, likely focusing on its ability to disentangle visual features from textual interference. The analysis would involve examining how well the model performs under various conditions that often challenge traditional methods, such as typographic attacks, noisy images, or images with unusual viewpoints. A discussion of the model’s performance on benchmark datasets exhibiting these challenges would be key. This analysis would also likely compare the performance of the proposed method with the state-of-the-art methods, highlighting any significant improvements in robustness. Quantitative metrics such as accuracy and precision on various datasets should be provided to support the claims of improved robustness, potentially alongside qualitative analysis demonstrating the method’s effectiveness in challenging scenarios. Finally, the analysis might also discuss the theoretical underpinnings that contribute to the model’s robustness, perhaps through detailed explanation of the techniques used for disentanglement and noise reduction.

Textual Feature Analysis#

A hypothetical ‘Textual Feature Analysis’ section in a research paper would deeply investigate the characteristics of textual data extracted from images. This would involve exploring different feature representation techniques, such as word embeddings (e.g., Word2Vec, GloVe) and more advanced methods like BERT or RoBERTa, focusing on the impact of various techniques on downstream tasks like text recognition or image classification. The analysis should include quantitative evaluations, comparing the performance of various feature extraction techniques based on metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. A crucial aspect would be discussing the influence of data preprocessing and noise handling on the quality of extracted features and how different methods address variations in font styles, sizes, and orientations. Qualitative analysis, potentially utilizing visualization techniques such as heatmaps or class activation maps, could provide further insight into feature significance. The analysis should also discuss the trade-offs between the complexity of different methods and their computational costs, ultimately justifying the chosen approach for the study.

Limitations and Future#

A research paper’s “Limitations and Future” section should thoughtfully address shortcomings and propose promising avenues. Limitations might include the scope of datasets used, the model’s performance on edge cases, or computational constraints. The discussion should acknowledge these honestly, avoiding overselling results. Future work could involve expanding the dataset’s diversity, testing the model on more challenging benchmarks, exploring alternative architectures or training methods, or investigating potential biases. Specific suggestions are crucial: exploring the impact of hyperparameter choices, developing robust evaluation metrics, or extending the model’s capabilities to address a broader set of tasks. The discussion should be forward-looking, outlining potential improvements and innovations that build upon the current research. Strong “Limitations and Future” sections demonstrate the authors’ self-awareness and foresight, strengthening the overall impact of the paper.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure demonstrates the mirror effect of CLIP on text and visual features. The left side shows images of a dog and an apple, both before and after horizontal flipping. The cosine similarity between the original and flipped images is close to 1, indicating that CLIP is invariant to horizontal flipping for visual objects. The right side shows the same images, but with text added (cat and earphones). In these images, the cosine similarity is significantly lower after flipping, demonstrating that CLIP is not invariant to horizontal flipping for text features. This difference is crucial for the MirrorCLIP model, as it allows it to distinguish between visual and textual features based on this horizontal flip invariance.

read the caption

Figure 2: The cosine similarity of the image features encoded by the CLIP image encoder before and after horizontal flipping. Adding text to the image leads to a significant decrease in cosine similarity, indicating that CLIP does not exhibit horizontal flip invariance for textual factors.

🔼 This figure presents the results of experiments designed to demonstrate the difference in mirror effects between visual objects and text using CLIP. The left panel (a) shows the cosine similarity of image features before and after horizontal flipping, for both original datasets (containing only images) and typographic datasets (images with added text). A high cosine similarity indicates that the features remain largely unchanged after flipping. The right panel (b) shows the proportion of textual mask generated by MirrorCLIP for each dataset, reflecting the algorithm’s ability to identify text within an image. The significant drop in cosine similarity in the typographic datasets and the increase in textual mask proportion demonstrate the effectiveness of MirrorCLIP in distinguishing text from visual elements based on the horizontal flip invariance of images, but not text.

read the caption

Figure 3: Results of mirror effect experiments, (a) Cosine similarity of image features before and after flipping on Original and Typographic datasets, (b) Proportion of textual mask on Original and Typographic datasets.

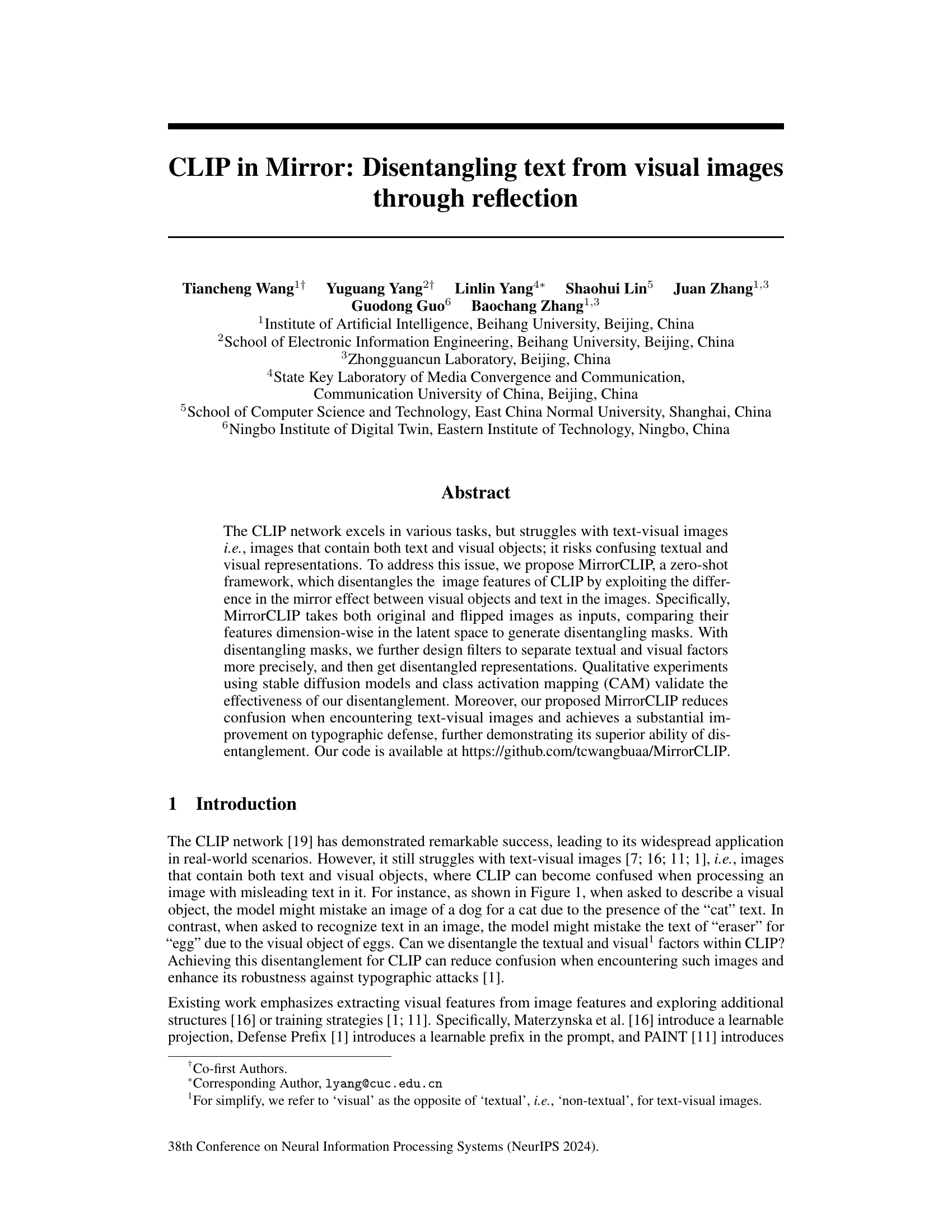

🔼 This figure shows how the disentangling mask is generated and how it changes with the addition of text to an image. (a) illustrates the process of generating the mask by comparing the signs of corresponding elements in the image features before and after horizontal flipping. Positive values indicate visual features, negative values indicate text features. (b) visually demonstrates the mask’s application to sample images, showing a clear increase in the textual mask proportion after text is added to the image.

read the caption

Figure 4: Generation of disentangling mask, (a) The disentangling mask is generated by contrasting the sign of corresponding positions in the image features before and after flipping. (b) Input images and generated disentangling masks (resized from 1 × 512 to 16 × 32). After adding text to the image, the proportion of textual mask increases significantly.

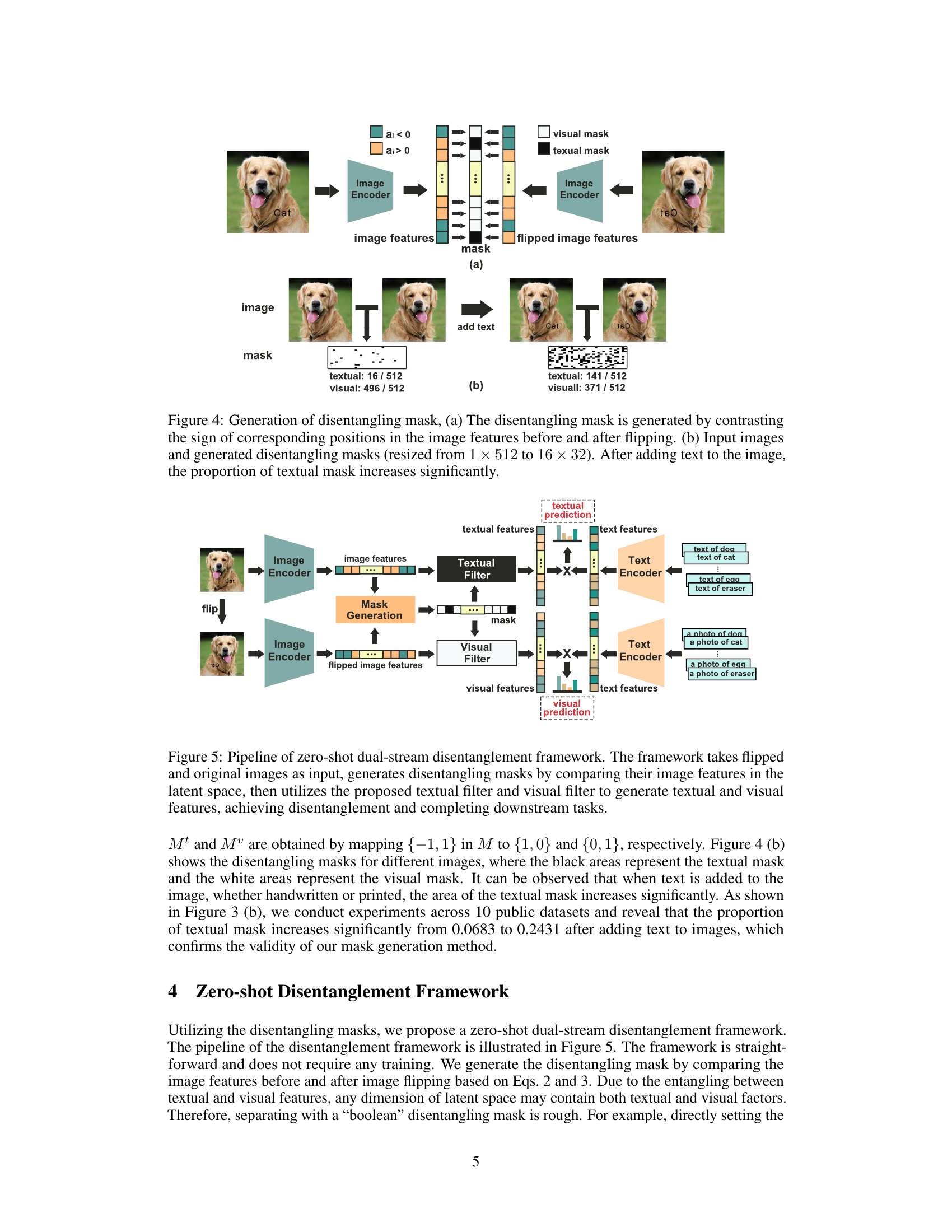

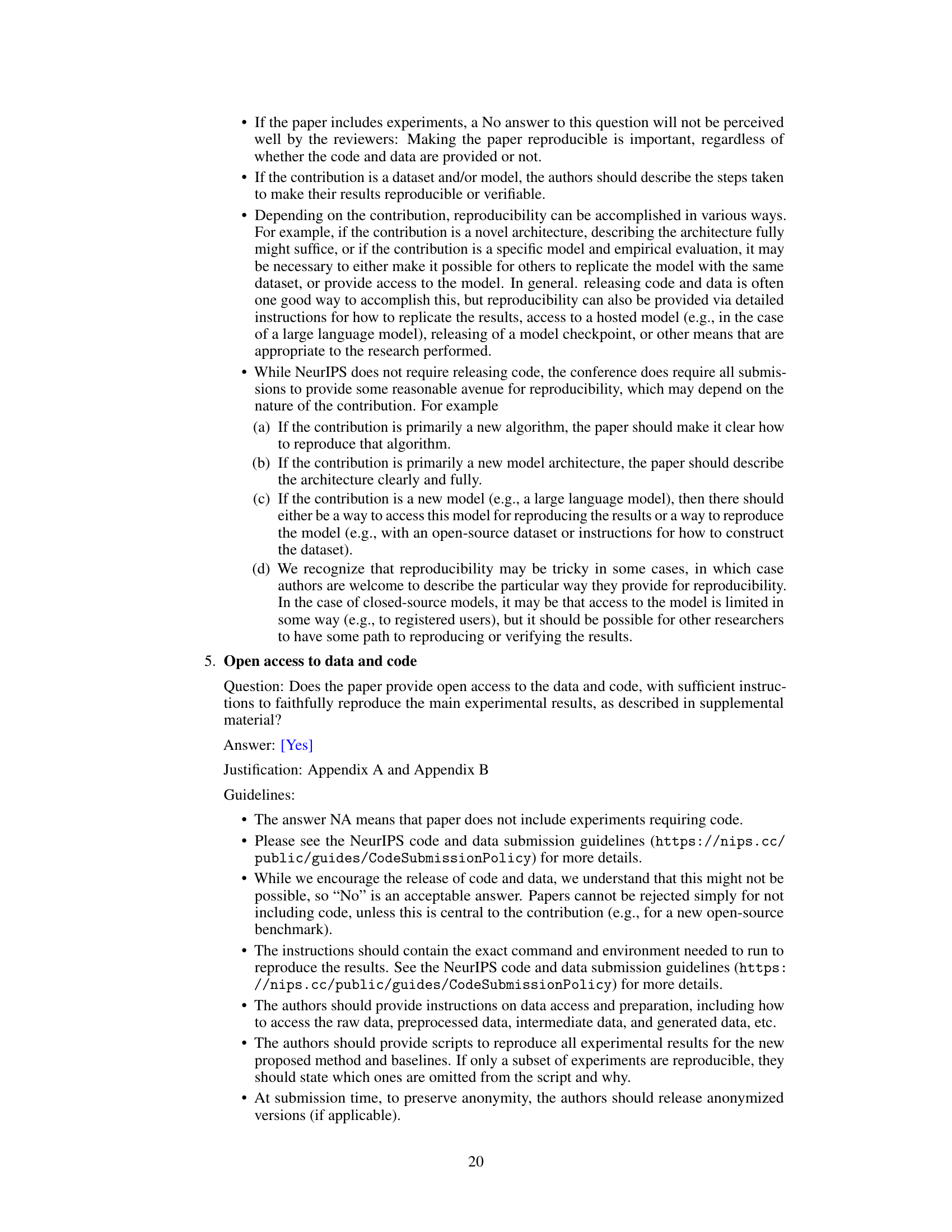

🔼 This figure illustrates the MirrorCLIP framework, a zero-shot method for disentangling textual and visual features from images. It uses both original and flipped versions of an image as input. The image encoders generate features for each, and a mask generation module compares these to identify textual and visual regions. These masks then filter the features, separating textual and visual information which allows for separate textual and visual predictions.

read the caption

Figure 5: Pipeline of zero-shot dual-stream disentanglement framework. The framework takes flipped and original images as input, generates disentangling masks by comparing their image features in the latent space, then utilizes the proposed textual filter and visual filter to generate textual and visual features, achieving disentanglement and completing downstream tasks.

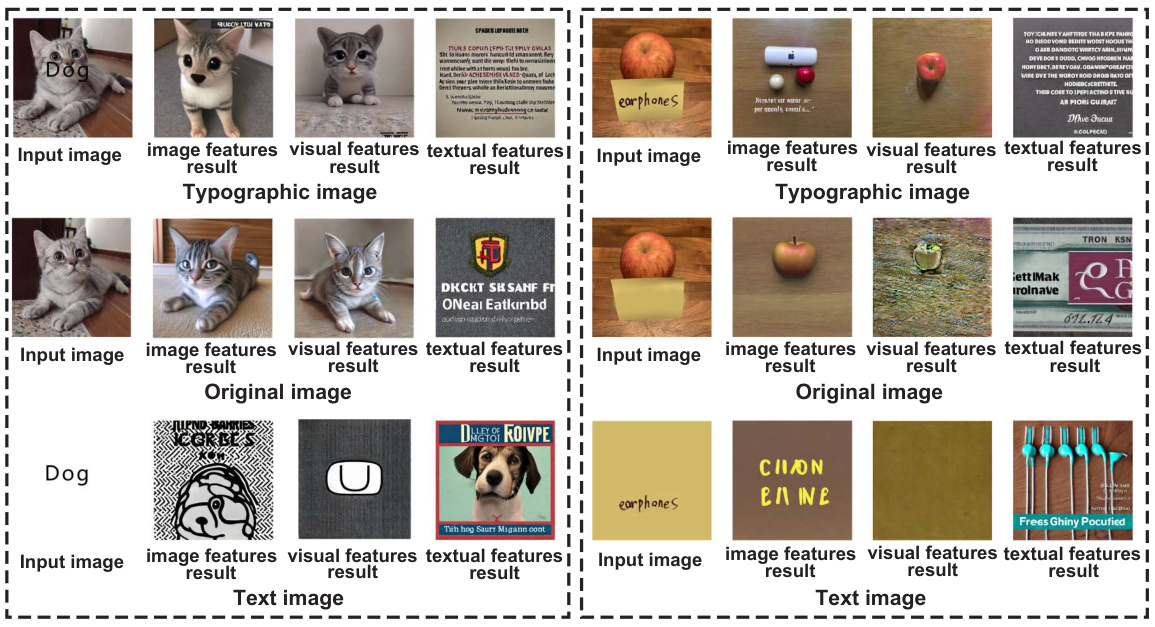

🔼 This figure shows the visualization of textual and visual features using Class Activation Mapping (CAM) for images that have been subjected to typographic attacks. The CAM highlights the regions of the image that contribute most strongly to the classification of the image. The left column shows the input image with overlaid text (a typographic attack). The middle column shows the CAM for the textual features, highlighting the regions corresponding to the added text. The right column shows the CAM for the visual features, highlighting the regions corresponding to the actual image content (the visual object). This demonstrates the effectiveness of the MirrorCLIP framework in separating textual and visual features from images.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visualization for textual and non-textual features for typographic attacked data using class activation map.

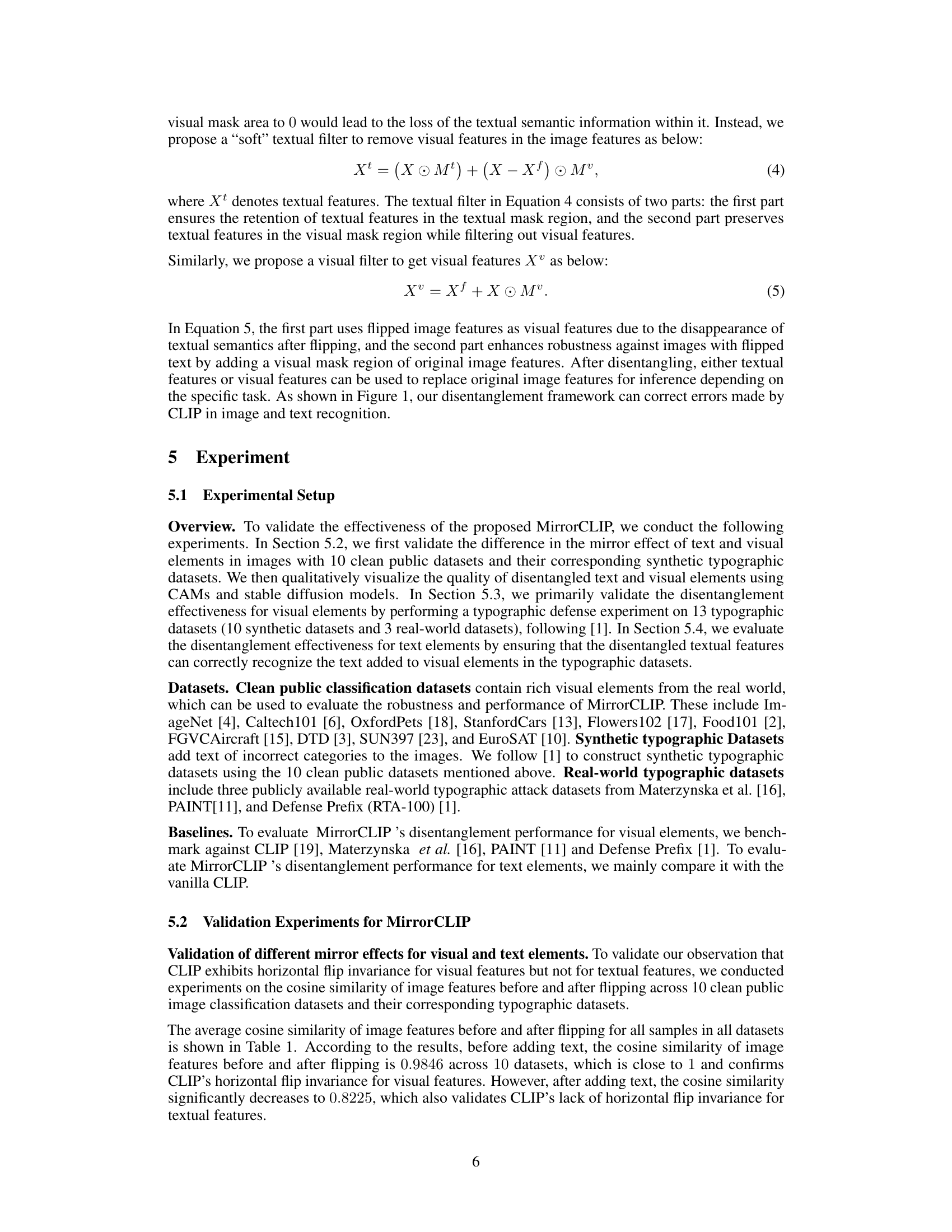

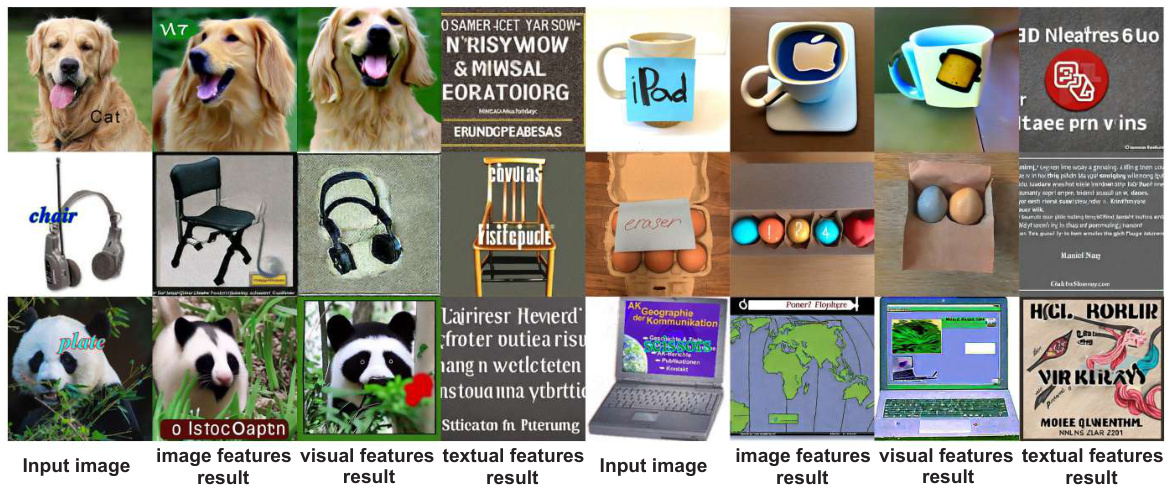

🔼 This figure visualizes the results of image variation experiments using the Stable unCLIP model. It demonstrates the effectiveness of the MirrorCLIP framework in disentangling textual and visual features. The top row shows the input image, the features extracted by the image encoder, the disentangled visual and textual features, and the images generated using only the visual or textual features. The results show that the disentangled visual features generate images similar to the original but without text, while the disentangled textual features generate images containing only text, thus demonstrating the success of the disentanglement process.

read the caption

Figure 7: Results of image variation using Stable unCLIP.

🔼 This figure demonstrates two potential applications of MirrorCLIP. In (a), it shows how MirrorCLIP improves RegionCLIP’s accuracy by disentangling text and visual features. Before using MirrorCLIP, RegionCLIP misclassified a price tag with the text ‘papaya’ as a papaya and a laptop monitor as a television because of the text interference. After using MirrorCLIP, RegionCLIP’s accuracy is improved. In (b), it shows how MirrorCLIP enhances SAM by providing disentangled textual features as prompts, achieving accurate text region segmentation.

read the caption

Figure 8: Potential Application Examples of MirrorCLIP. (a) Using MirrorCLIP to disentangle region features of RegionCLIP, before disentanglement, RegionCLIP mistakenly identified a price tag with text “papaya” as papaya and a laptop monitor as a television set because of the interference of text “television”. (b) Textual features disentangled by MirrorCLIP are used to provide prompts for SAM, achieving text region segmentation.

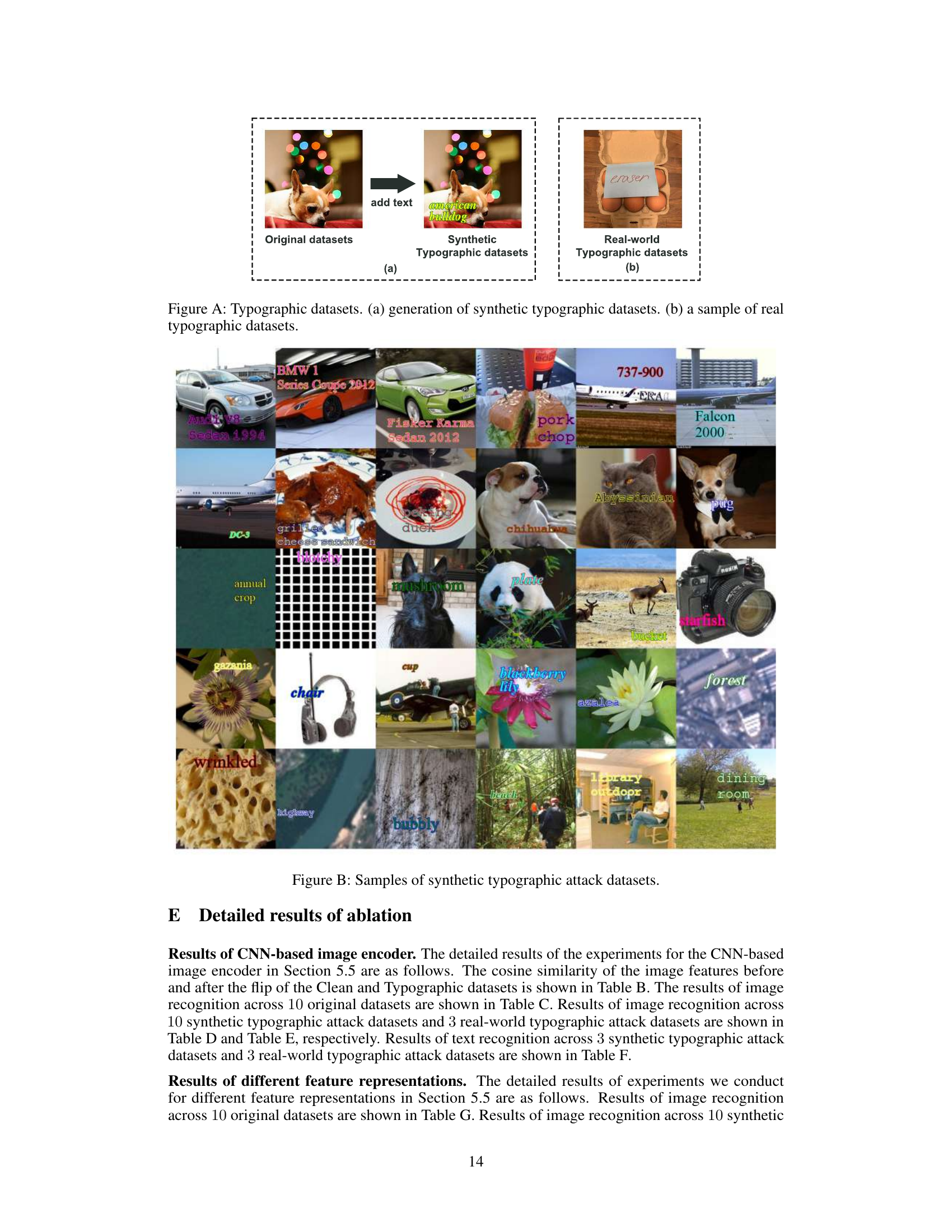

🔼 This figure shows examples of typographic attack datasets used in the paper. Panel (a) illustrates the process of creating synthetic typographic datasets: starting with an original image (e.g., a dog), irrelevant text is added on top. Panel (b) displays examples of real-world typographic datasets, where images already contain overlaid or nearby text that could be misleading to a model performing image recognition.

read the caption

Figure A: Typographic datasets. (a) generation of synthetic typographic datasets. (b) a sample of real typographic datasets.

🔼 This figure shows examples of images from synthetic typographic attack datasets. The original images have been modified by adding text that is irrelevant to the actual visual content of the image. This is done to simulate real-world scenarios where misleading text could confuse a model trying to identify the object in the image. The goal is to test the robustness of the model against these typographic attacks.

read the caption

Figure B: Samples of synthetic typographic attack datasets.

🔼 This figure shows examples of real-world typographic attacks used in the paper’s experiments. These images depict objects with misleading text labels added to them, demonstrating a challenging scenario for image recognition models. The labels are handwritten and purposefully incorrect to mimic real-world situations where visual and textual information may conflict.

read the caption

Figure C: Samples of real-world typographic attack datasets.

🔼 This figure shows the visualization of textual and visual features using Class Activation Mapping (CAM) for images with typographic attacks. The CAM highlights the regions of the image that contribute most strongly to the classification of textual or visual content. For each image, there are three sub-images: the input image with added text, the CAM for the disentangled textual features, and the CAM for the disentangled visual features. This visualizes how effectively MirrorCLIP separates textual and visual regions in text-visual images.

read the caption

Figure 6: Visualization for textual and non-textual features for typographic attacked data using class activation map.

🔼 This figure shows the results of image generation using the Stable unCLIP model with different input conditions. The top row shows the input images, which include images with and without added typographic text. The subsequent rows display the results of image generation using the original image features, disentangled visual features, and disentangled textual features from MirrorCLIP, respectively. The results demonstrate the ability of MirrorCLIP to effectively separate visual and textual features in images, as the visual features generate images similar to the original but without text, while the textual features generate images that only contain text.

read the caption

Figure 7: Results of image variation using Stable unCLIP.

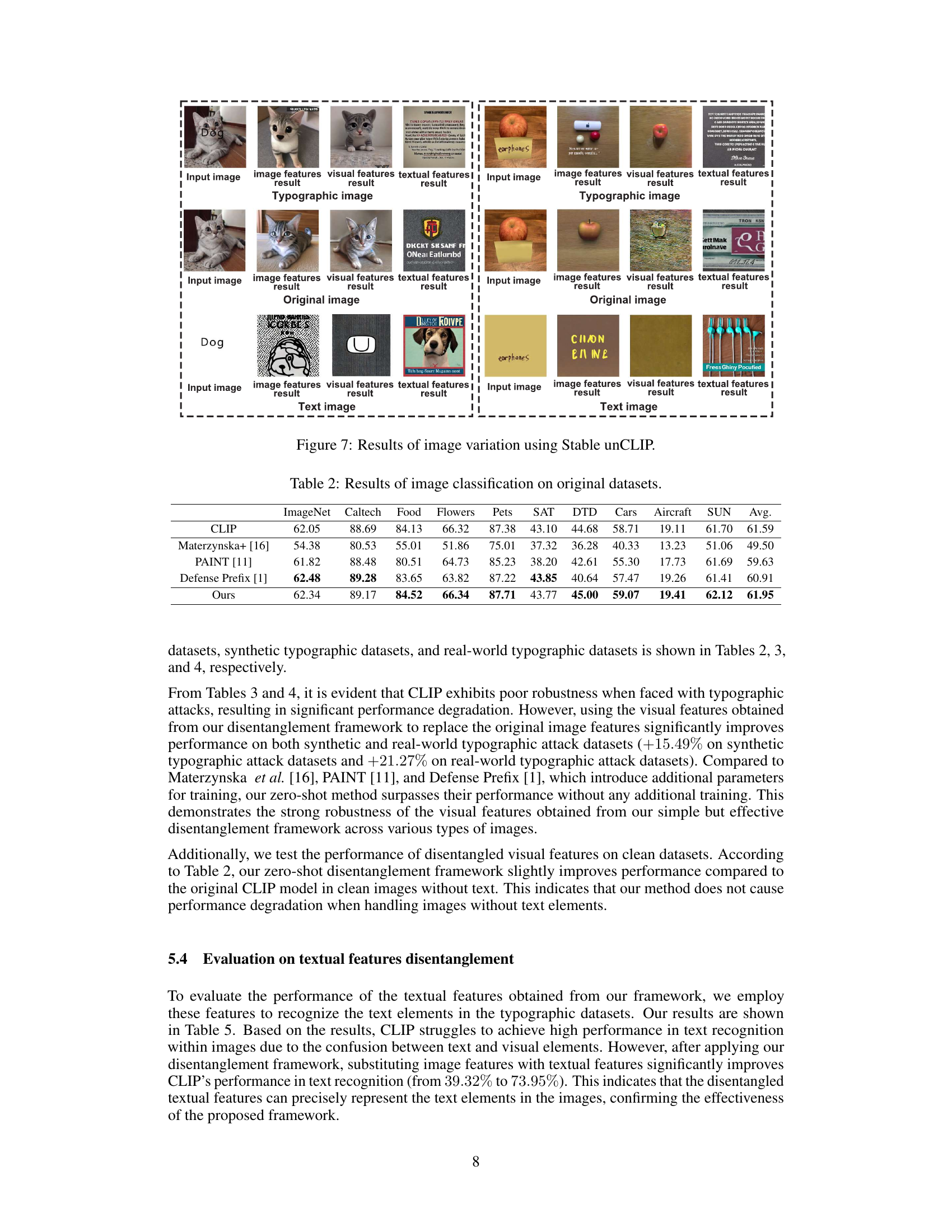

More on tables

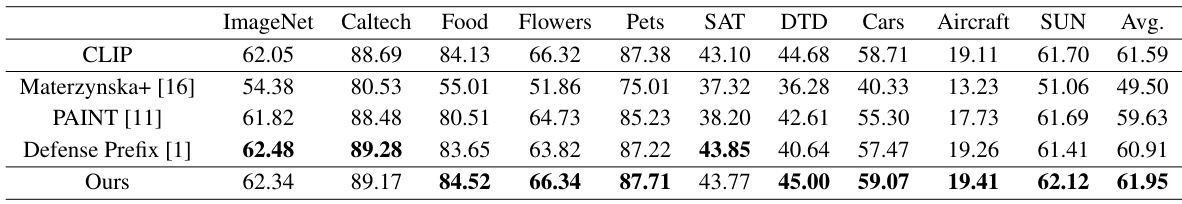

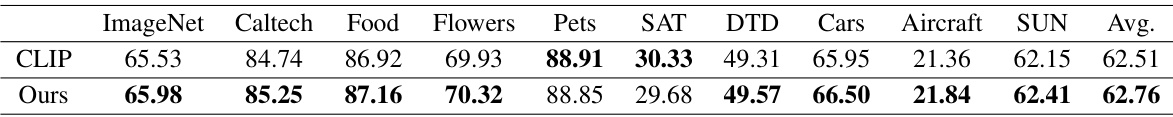

🔼 This table presents the performance of various methods on image classification tasks using original datasets (without typographic attacks). The methods compared include CLIP (the baseline), Materzynska et al. [16], PAINT [11], Defense Prefix [1], and the proposed MirrorCLIP method. The table shows the accuracy achieved by each method across 10 different datasets, providing a comprehensive comparison of their performance on standard image classification benchmarks.

read the caption

Table 2: Results of image classification on original datasets.

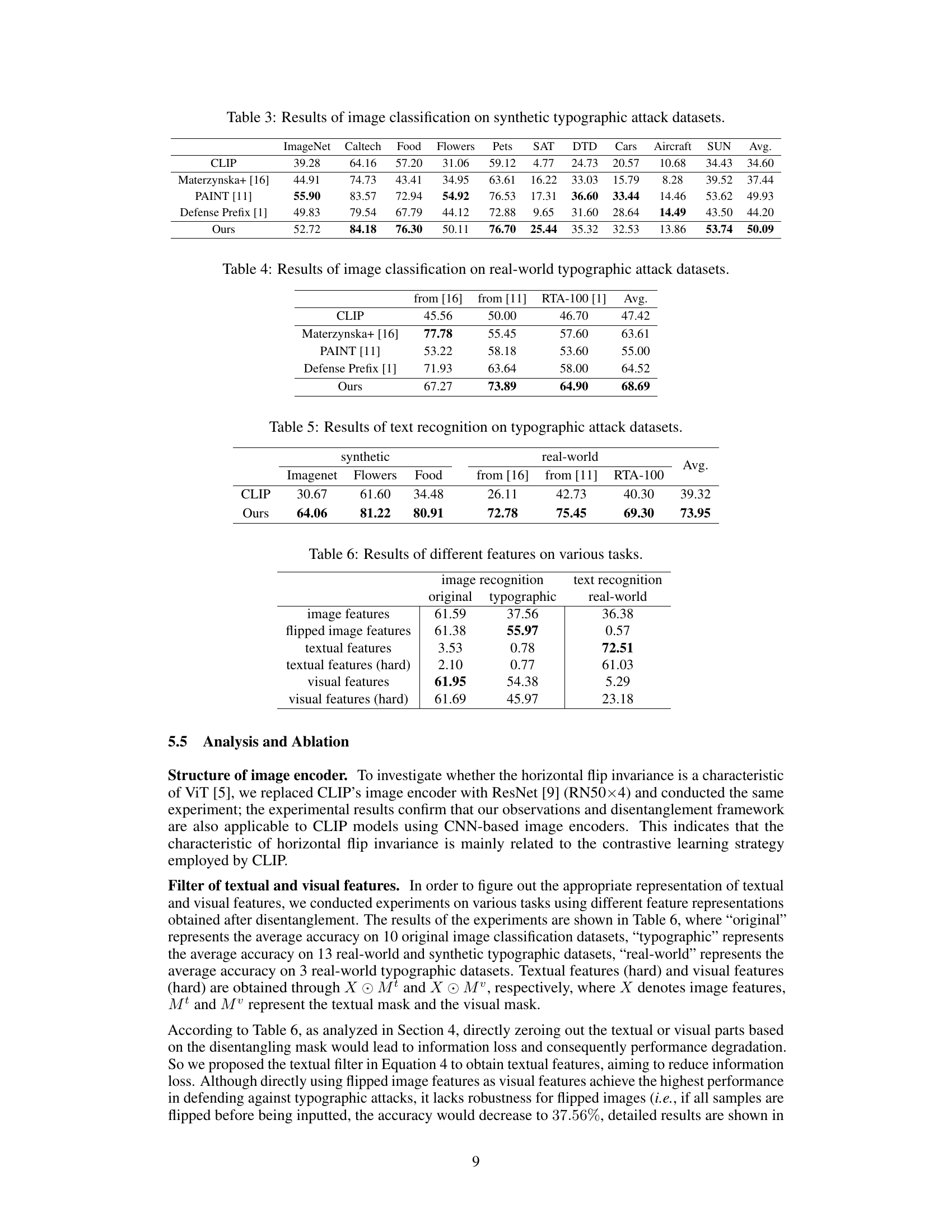

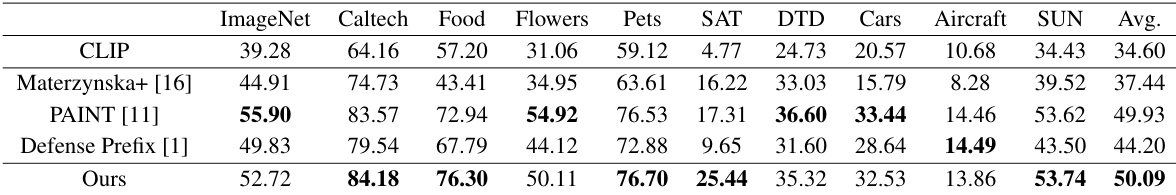

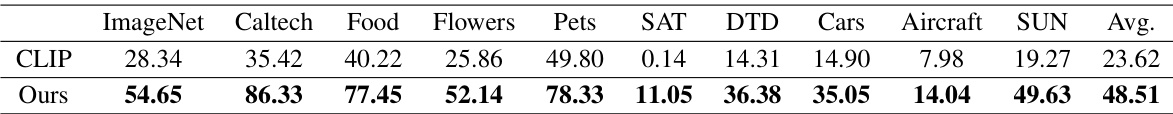

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments conducted on synthetic typographic attack datasets. It compares the performance of several methods, including CLIP, Materzynska et al. [16], PAINT [11], Defense Prefix [1], and the proposed MirrorCLIP method. The results are shown as the average accuracy across various datasets (ImageNet, Caltech, Food, Flowers, Pets, SAT, DTD, Cars, Aircraft, SUN). The table highlights the improvement achieved by MirrorCLIP in defending against typographic attacks, where misleading text is overlaid on images.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of image classification on synthetic typographic attack datasets.

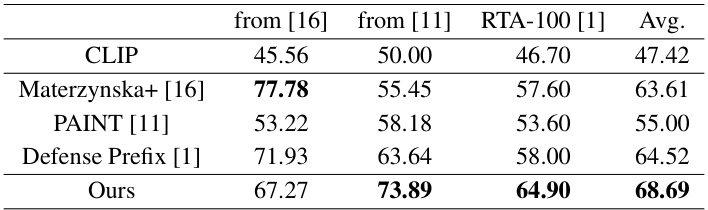

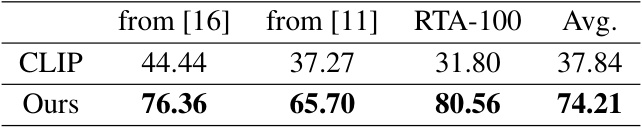

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments conducted on three real-world typographic attack datasets. It compares the performance of different methods, including CLIP, Materzynska et al. [16], PAINT [11], Defense Prefix [1], and the proposed MirrorCLIP method. The results show the accuracy of each method in correctly classifying images that have been tampered with by adding misleading text, demonstrating the effectiveness of MirrorCLIP in handling such adversarial examples.

read the caption

Table 4: Results of image classification on real-world typographic attack datasets.

🔼 This table presents the results of text recognition experiments conducted on typographic attack datasets. It compares the performance of the baseline CLIP model against the proposed MirrorCLIP framework. The results are broken down by dataset (Imagenet, Flowers, Food, and three real-world datasets from [16], [11], and RTA-100) showing a significant improvement in accuracy for MirrorCLIP.

read the caption

Table 5: Results of text recognition on typographic attack datasets.

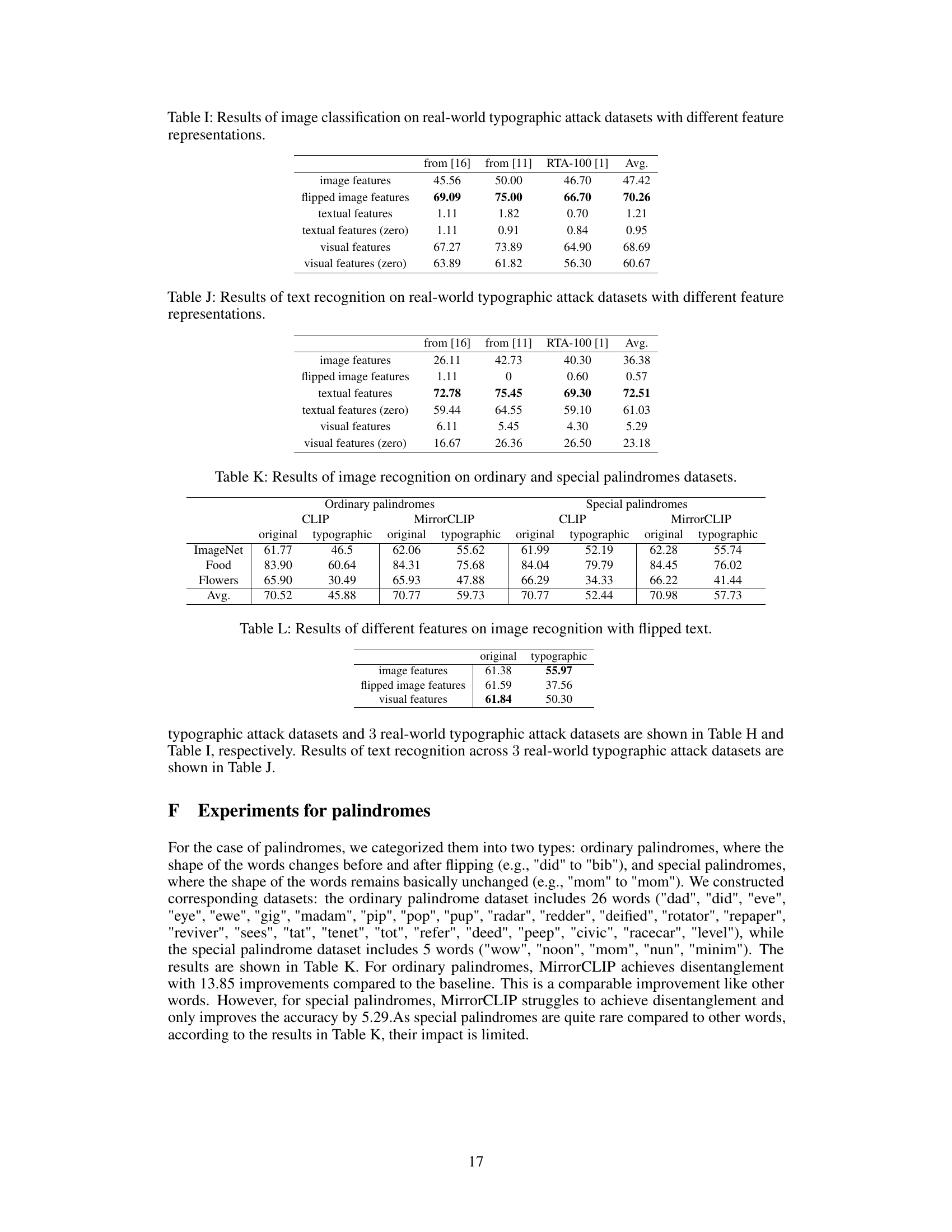

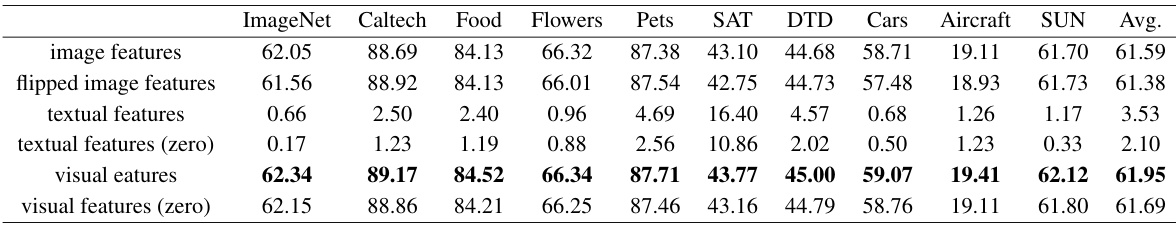

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of different feature representations (image features, flipped image features, textual features, textual features (hard), visual features, visual features (hard)) on three tasks: image recognition (original and typographic images), and text recognition (real-world typographic attacks). The results show the effectiveness of disentangled features on each of these tasks, highlighting that the proposed disentanglement method improves performance, particularly in text recognition.

read the caption

Table 6: Results of different features on various tasks.

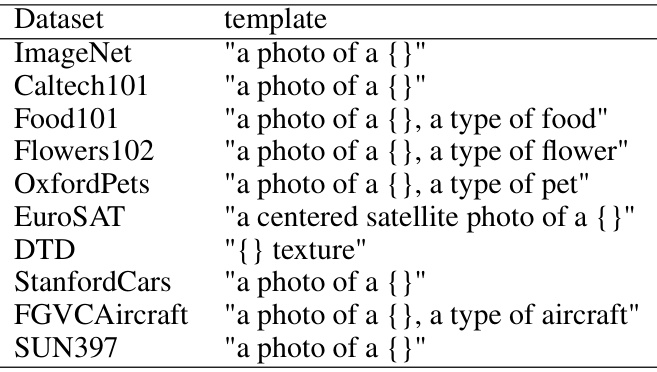

🔼 This table lists the templates used for image recognition in synthetic typographic attack datasets. For each dataset (ImageNet, Caltech101, Food101, Flowers102, OxfordPets, EuroSAT, DTD, StanfordCars, FGVCAircraft, SUN397), a text prompt template is provided that was used with CLIP. These templates are designed to guide CLIP in its image recognition task, especially in the context of typographic attacks where misleading text is superimposed on the image.

read the caption

Table A: Templates of synthetic typographic attack datasets for image recognition

🔼 This table presents the cosine similarity of image features before and after horizontal flipping for both clean and typographic datasets. The experiment uses ResNet50x4 as the image encoder. It shows how the cosine similarity changes after adding text to the images, indicating the difference in the ‘mirror effect’ between visual objects and text. Lower cosine similarity after flipping for typographic images indicates that the textual elements lack horizontal flip invariance in CLIP.

read the caption

Table B: Image features’ cosine similarity before and after flipping on Clean and Typographic datasets with RN50×4 as image encoder.

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments performed on original datasets (without typographic attacks). It compares the performance of the proposed MirrorCLIP method against several baseline methods, including CLIP, Materzynska et al., PAINT, and Defense Prefix. The results are shown for 10 different datasets, showcasing the accuracy of each method in correctly classifying images. The performance is measured as the average classification accuracy across these datasets.

read the caption

Table 2: Results of image classification on original datasets.

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments conducted on synthetic typographic attack datasets. It compares the performance of the proposed MirrorCLIP method against the baseline CLIP model and other state-of-the-art typographic defense methods (Materzynska et al., PAINT, Defense Prefix). The results are shown for 10 different datasets, illustrating the effectiveness of MirrorCLIP in mitigating the impact of typographic attacks on image recognition.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of image classification on synthetic typographic attack datasets.

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments conducted on three real-world typographic attack datasets. It compares the performance of the proposed MirrorCLIP method against the baseline CLIP model and three other state-of-the-art typographic defense methods: Materzynska et al. [16], PAINT [11], and Defense Prefix [1]. The results show that MirrorCLIP significantly improves the accuracy of image classification on these datasets compared to the other methods, highlighting its effectiveness in handling text-visual images.

read the caption

Table 4: Results of image classification on real-world typographic attack datasets.

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments conducted on synthetic typographic attack datasets. It compares the performance of the proposed MirrorCLIP method against the baseline CLIP model. The datasets used are synthetic versions of 10 public datasets, where misleading text has been added to the images. The table showcases a significant improvement in accuracy achieved by MirrorCLIP compared to CLIP, highlighting the effectiveness of its disentanglement technique in mitigating the negative impact of misleading text.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of image classification on synthetic typographic attack datasets.

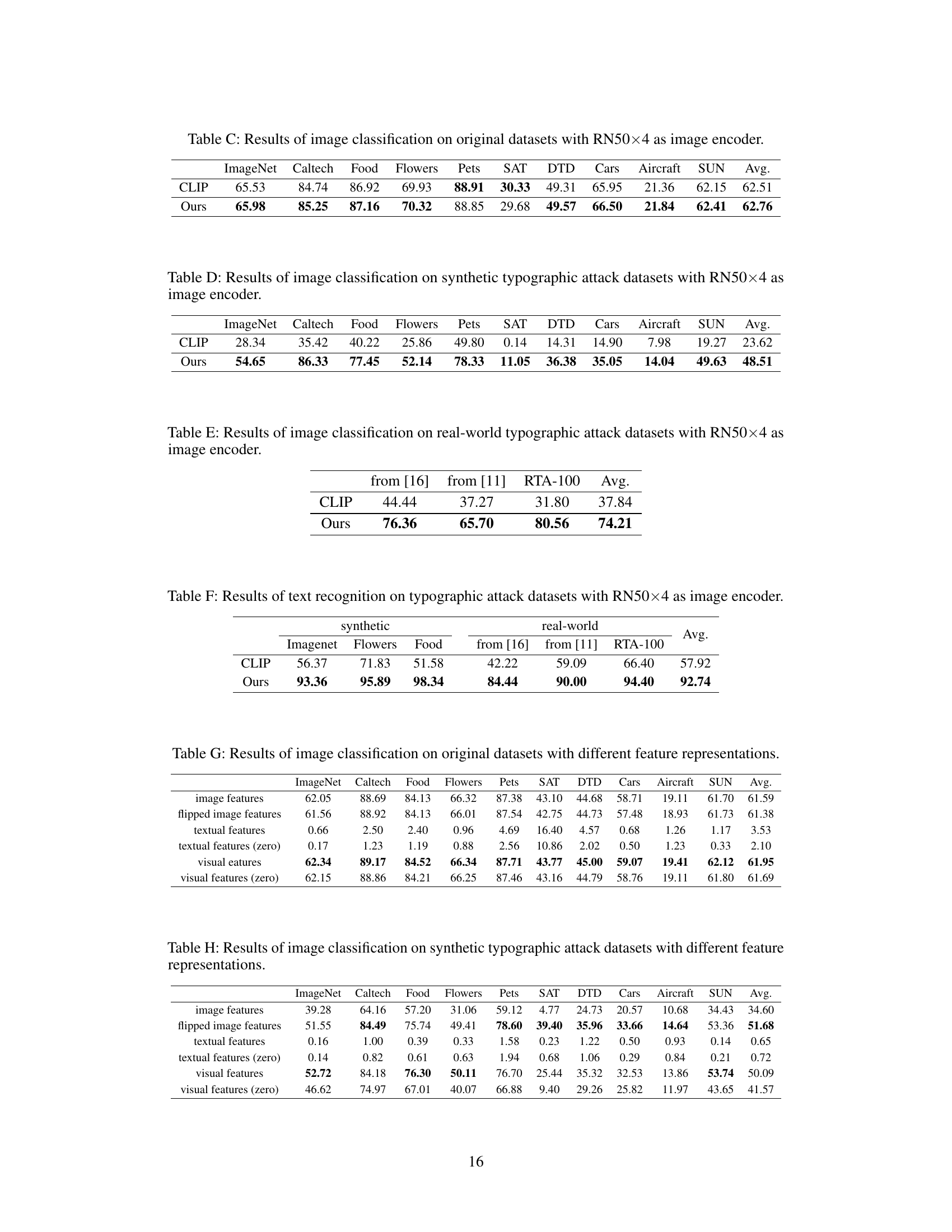

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification on 10 original datasets using different feature representations. The rows represent the performance of image classification using different feature sets: original image features, flipped image features, textual features, textual features (zero), visual features, and visual features (zero). The columns represent the 10 different datasets, and the final column shows the average performance across all datasets. The table compares the effectiveness of each feature set in the context of image recognition.

read the caption

Table G: Results of image classification on original datasets with different feature representations.

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments conducted on synthetic typographic attack datasets. The experiments evaluate the performance of different methods, including the proposed MirrorCLIP and several baselines, in correctly classifying images that have been modified with superimposed text that is typographically designed to mislead the model. The table shows the accuracy of each method on various datasets, highlighting the effectiveness of MirrorCLIP in mitigating the impact of typographic attacks.

read the caption

Table 3: Results of image classification on synthetic typographic attack datasets.

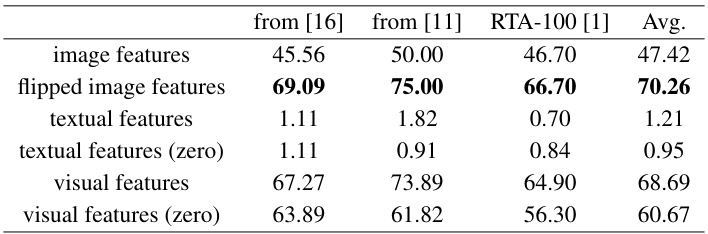

🔼 This table presents the results of image classification experiments conducted on three real-world typographic attack datasets using different feature representations obtained from the proposed MirrorCLIP framework. The datasets represent scenarios where text is superimposed on images, posing a challenge to image recognition models. The features compared are: original image features, flipped image features, textual features (with and without zeroing), and visual features (with and without zeroing). The performance is measured as the accuracy percentage in correctly identifying the images despite textual interference. The comparison highlights the impact of disentangling textual and visual features in improving robustness to typographic attacks.

read the caption

Table I: Results of image classification on real-world typographic attack datasets with different feature representations.

🔼 This table presents the results of text recognition experiments conducted on real-world typographic attack datasets using different feature representations. The representations tested include: original image features, flipped image features, textual features (with and without zeroing), and visual features (with and without zeroing). The performance is evaluated across three different datasets from the literature ([16], [11], RTA-100 [1]). The average accuracy across these three datasets is reported for each feature representation, showing the impact of disentanglement on the performance of text recognition.

read the caption

Table J: Results of text recognition on real-world typographic attack datasets with different feature representations.

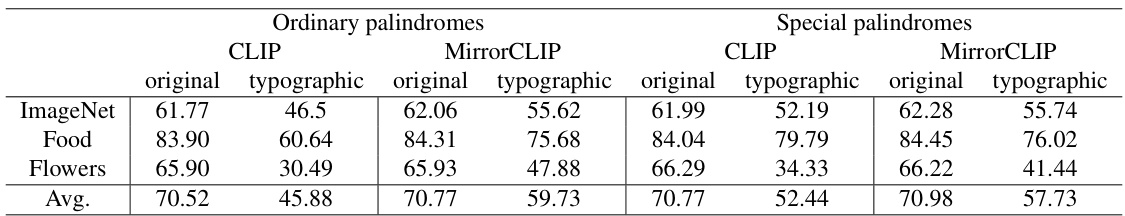

🔼 This table presents the results of image recognition experiments conducted on two types of palindrome datasets: ordinary and special. Ordinary palindromes are those where the word’s visual appearance changes upon horizontal flipping (e.g., ‘did’ to ‘bib’), while special palindromes retain their visual form after flipping (e.g., ‘mom’ to ‘mom’). The results are shown for both CLIP and MirrorCLIP, comparing the accuracy of image recognition on original (non-typographic) and typographic images for each dataset and palindrome type. The ‘Avg.’ row provides average accuracy across the three datasets.

read the caption

Table K: Results of image recognition on ordinary and special palindromes datasets.

🔼 This table presents the results of image recognition experiments using different feature representations (image features, flipped image features, and visual features) on both original and typographic datasets where images have been horizontally flipped. The accuracy for each representation is shown separately for original and typographic images indicating the robustness of each feature representation to the typographic attacks.

read the caption

Table L: Results of different features on image recognition with flipped text.

Full paper#