↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Biological sequence editing is crucial for advancements in medicine and biotechnology, particularly in gene therapy and designing nucleic acid therapeutics. However, existing methods often struggle to optimize biological properties while keeping the number of edits minimal. This is problematic because too many edits can reduce predictability and potentially compromise safety. Current generative models, though promising, typically generate entirely new sequences from scratch, which also poses safety and predictability concerns.

This research addresses these issues by introducing GFNSeqEditor, a new algorithm that leverages generative flow networks. GFNSeqEditor first identifies suboptimal elements within a seed sequence that negatively impact the desired property. It then uses a learned policy to make edits at these locations, generating multiple diverse options. The number of edits can be carefully controlled through hyperparameters. Extensive experiments show GFNSeqEditor outperforms existing state-of-the-art methods across various datasets and tasks, improving the desired biological property with fewer changes.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in synthetic biology and biomedicine. It introduces a novel and efficient sequence editing algorithm, GFNSeqEditor, superior to existing methods, and opening new avenues for drug and gene therapy development by improving sequence properties with fewer alterations, enhancing safety and predictability. Its theoretical analysis and broad applicability across various datasets are significant contributions.

Visual Insights#

This figure shows an example of how the sequence editor works. A DNA sequence (ATGTCCGC) is given as input. The editor identifies positions (2nd and 7th base) that need modification to improve the desired property. The algorithm edits these positions (changing T to C and C to A, respectively) resulting in a new sequence (ACGTCCAC) with an improved property.

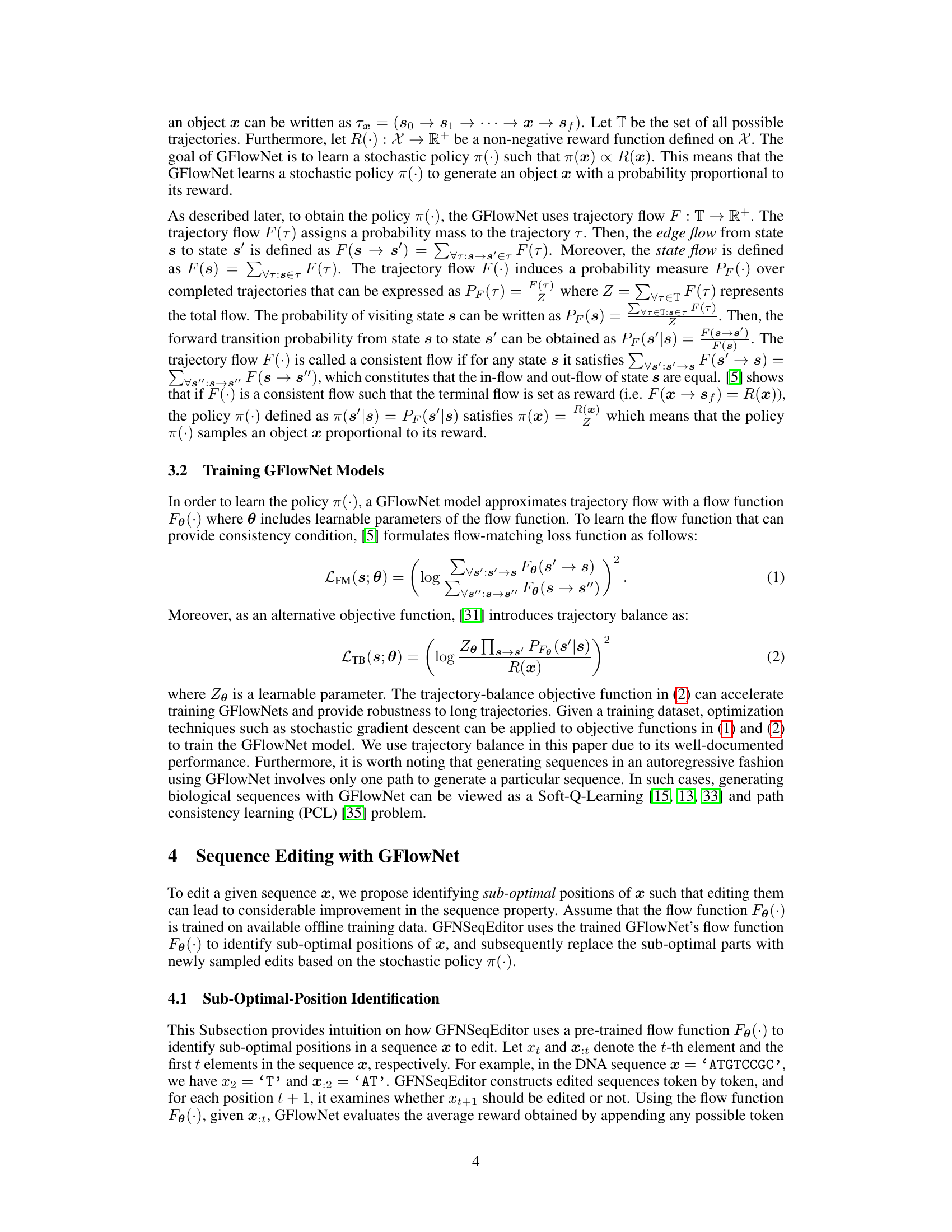

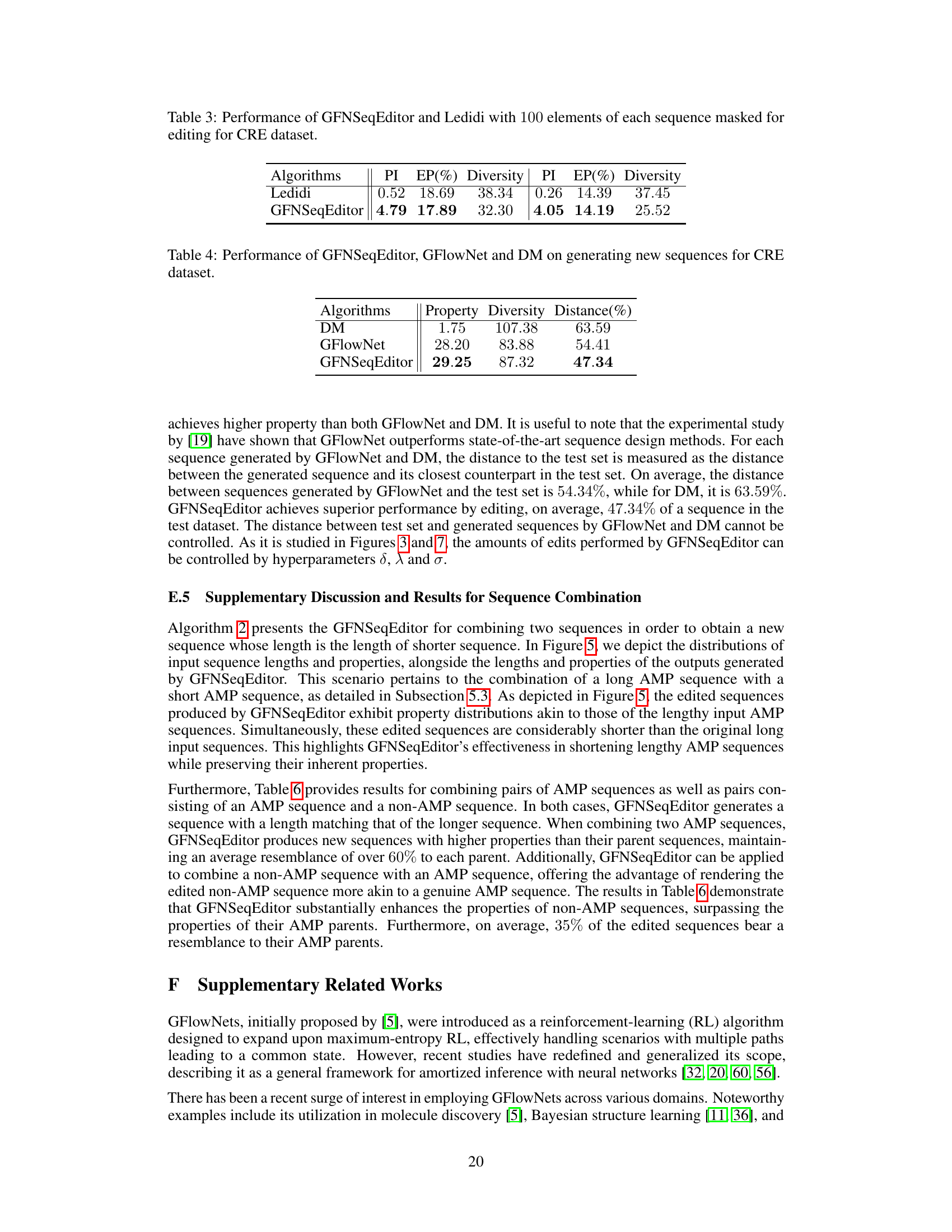

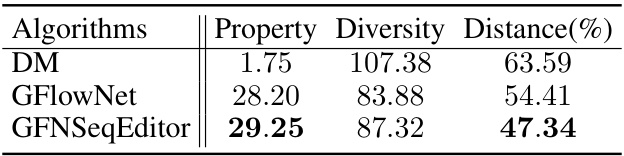

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the GFNSeqEditor algorithm against several baseline methods across three different datasets (TFbinding, AMP, and CRE). The comparison is based on four key metrics: Property Improvement (PI), Edit Percentage (EP), Diversity, and Geometric Mean of Property Improvement and Diversity (GMDPI). Higher values for PI, Diversity, and GMDPI indicate better performance. The Edit Percentage (EP) was kept relatively consistent across all methods for a fair comparison. The table allows for assessing the effectiveness of GFNSeqEditor relative to existing approaches in various biological sequence editing tasks.

In-depth insights#

SeqEdit with GFN#

The heading ‘SeqEdit with GFN’ suggests a methodology for sequence editing leveraging Generative Flow Networks (GFNs). This approach likely uses the inherent ability of GFNs to generate sequential data, adapting them to modify existing sequences rather than creating entirely new ones. The method probably involves a learned policy within the GFN to identify suboptimal sections of a given sequence and suggest edits to improve a specific property. This process would likely be iterative, applying edits sequentially until a satisfactory outcome is reached. A crucial advantage would be the potential to generate diverse sequence modifications compared to traditional optimization methods, leading to a broader exploration of the solution space. However, challenges might involve defining an appropriate reward function within the GFN to guide edits effectively, as well as ensuring computational efficiency. Furthermore, the generalizability of the learned policy to unseen sequences and the handling of sequence length variations need to be thoroughly assessed. Finally, a theoretical analysis is essential to understand the properties of the edited sequences and the process’s limitations.

GFNSeqEditor Analysis#

The GFNSeqEditor Analysis section would likely delve into a rigorous evaluation of the proposed algorithm’s performance and theoretical properties. It would likely begin with a theoretical analysis, deriving bounds on key metrics such as the expected reward improvement and the number of edits made. This would involve proving theorems and providing clear mathematical justifications, demonstrating that the algorithm’s behavior is predictable and controllable through hyperparameters. The analysis would likely then transition into empirical results, showing the algorithm’s performance across a range of datasets and biological tasks. Comparison to state-of-the-art baselines would be crucial, highlighting GFNSeqEditor’s advantages in terms of efficiency and accuracy in enhancing desired biological properties. Finally, the analysis might explore the algorithm’s sensitivity to hyperparameter choices, and potential areas for future work, potentially including robustness analysis and scalability concerns.

Seq Generation Aid#

The ‘Seq Generation Aid’ section likely details how the GFNSeqEditor algorithm enhances existing sequence generation models. Instead of generating sequences from scratch, a process prone to producing unrealistic or unsafe sequences, GFNSeqEditor refines pre-generated sequences, improving their properties. This approach leverages the strengths of generative models for diversity while mitigating their limitations in terms of safety and predictability. The method likely involves identifying sub-optimal parts of a pre-generated sequence and then using GFNSeqEditor’s learned stochastic policy to generate edits, thereby optimizing the sequence for specific biological attributes. This synergistic approach combines the exploration of generative models with the precision of GFNSeqEditor’s editing capabilities, resulting in a higher quality, more desirable sequence. A key strength is the ability to regulate the number of edits using specific hyperparameters, controlling the balance between generating novel sequences and maintaining similarity to the original seed sequence. This is important from both a practical perspective (avoiding unpredictable modifications) and a safety perspective (reducing the risk of unwanted side-effects). The results likely demonstrate improvements over existing de novo sequence generation methods, highlighting the advantages of this hybrid approach.

Ablation Study#

An ablation study systematically removes components of a model to assess their individual contributions. In the context of a sequence editing model like GFNSeqEditor, this might involve removing or altering key aspects such as the sub-optimal position identification function, the stochastic policy for generating edits, or the specific hyperparameters that control exploration-exploitation trade-offs. The results of an ablation study would reveal which components are most crucial for the model’s overall performance. A well-designed ablation study would demonstrate the importance of each component by showing a clear decline in performance when that component is removed. For instance, eliminating the stochastic policy might reduce the model’s ability to generate diverse edits, limiting its capacity to find optimal solutions. Similarly, adjusting the hyperparameters could reveal their impact on the balance between generating highly improved sequences and those that are too dissimilar from the original. The insights gained from an ablation study are valuable for both understanding the inner workings of the model and guiding future improvements. By pinpointing the most critical components, researchers can focus their efforts on refining those elements. This iterative process of ablation and refinement leads to a more robust and efficient model.

Future of SeqEdit#

The future of SeqEdit, or biological sequence editing, is bright, driven by the convergence of AI, high-throughput experimentation, and a deeper understanding of biological systems. Advances in generative models, particularly those based on flow networks like GFlowNets, offer the potential for faster, more efficient, and more precise sequence design. The ability to simultaneously optimize multiple properties, such as binding affinity, expression level, and stability, will become increasingly important. Incorporating more diverse data types like protein-protein interaction networks and structural information into training datasets will lead to more accurate and robust models. Future SeqEdit tools will likely incorporate interactive elements, allowing users to guide the editing process based on real-time feedback from experiments or simulations. Furthermore, there will be a continued emphasis on safe and predictable sequence design. Addressing the risk of off-target effects and unwanted immune responses will be crucial for translating SeqEdit techniques into practical applications in areas such as gene therapy and synthetic biology. Ethical considerations regarding the responsible development and deployment of these powerful technologies will also need to be addressed.

More visual insights#

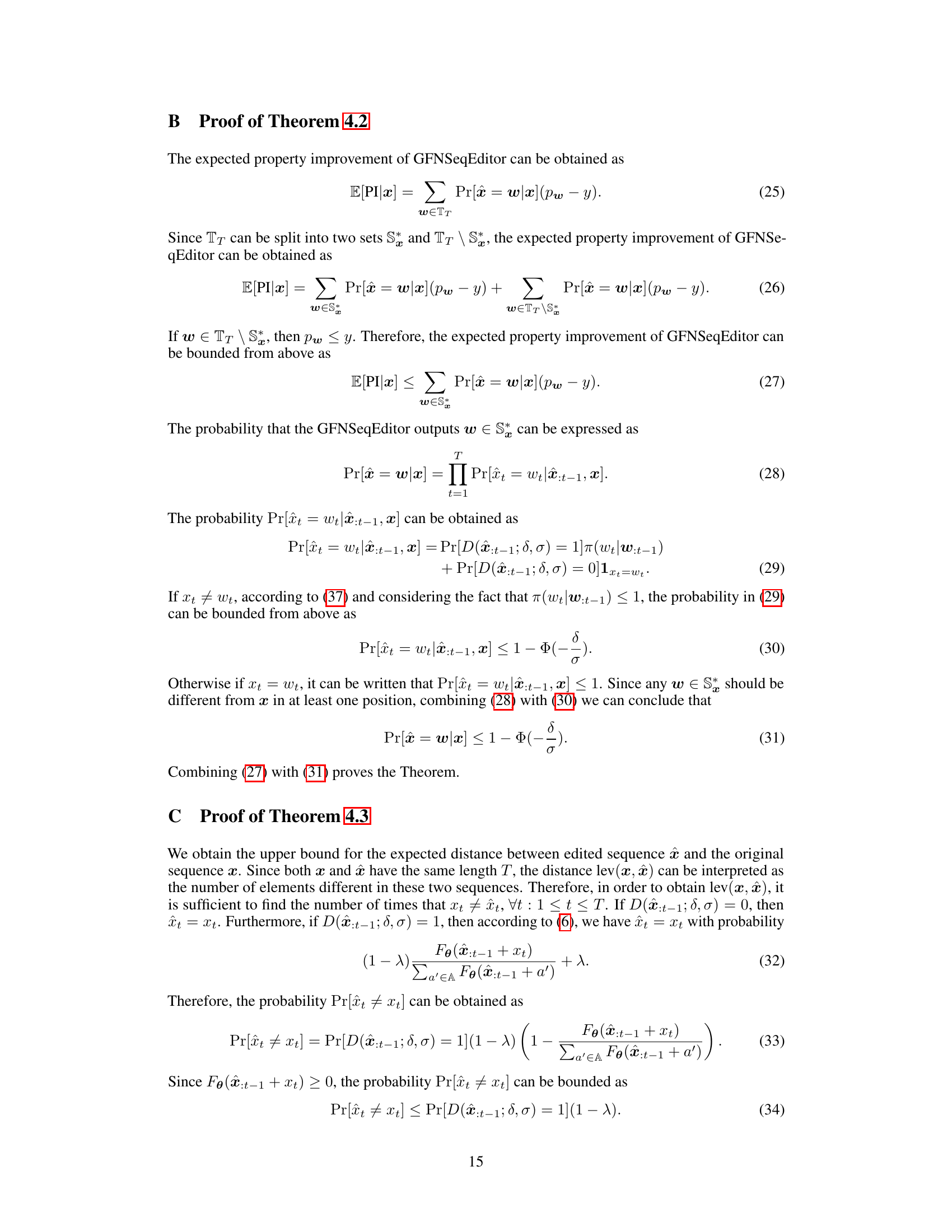

More on figures

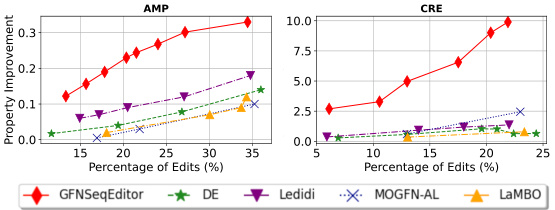

This figure shows the relationship between property improvement and the percentage of edits made to AMP and CRE sequences using different sequence editing methods. GFNSeqEditor consistently demonstrates superior performance across a range of edit percentages compared to other methods including Directed Evolution (DE), LaMBO, MOGFN-AL, and Ledidi. This highlights the effectiveness of GFNSeqEditor in enhancing the desired properties of sequences while controlling the number of edits.

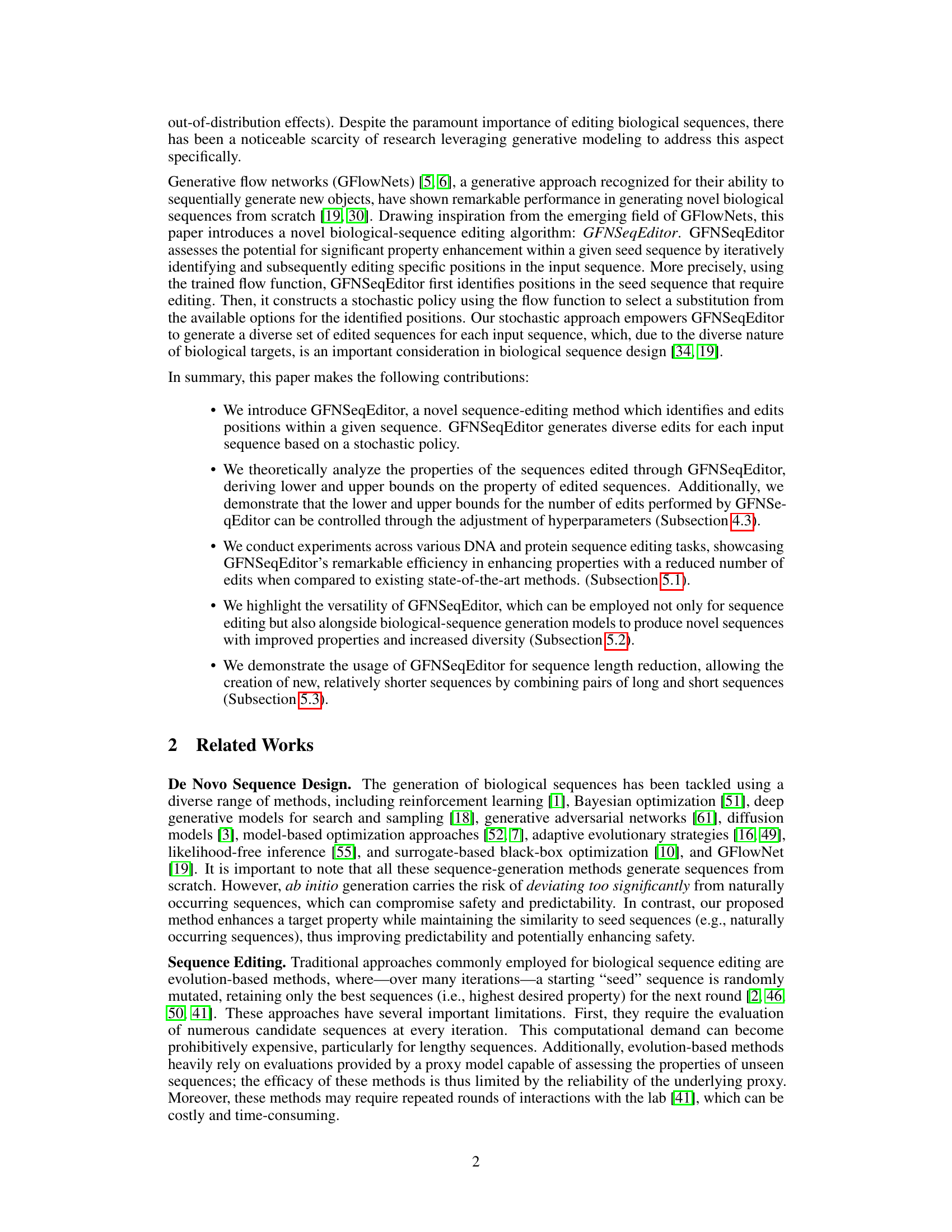

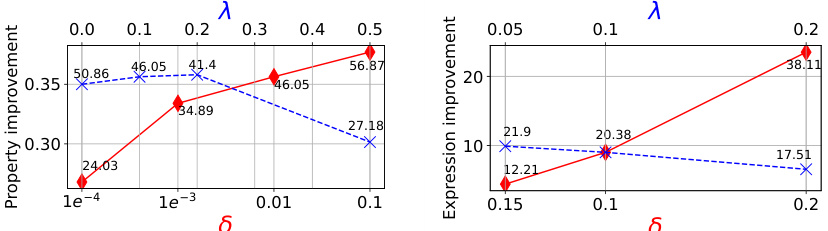

This figure shows how the hyperparameters δ (x-axis) and λ (top-axis) affect the performance of the GFNSeqEditor algorithm on two different datasets: AMP and CRE. The plots display the property improvement achieved by the algorithm as a function of δ and λ for each dataset. Different markers (red and blue) represent different values of λ for each dataset, showing how changes in λ interact with different values of δ. The x-axis represents the percentage of edits made by the algorithm.

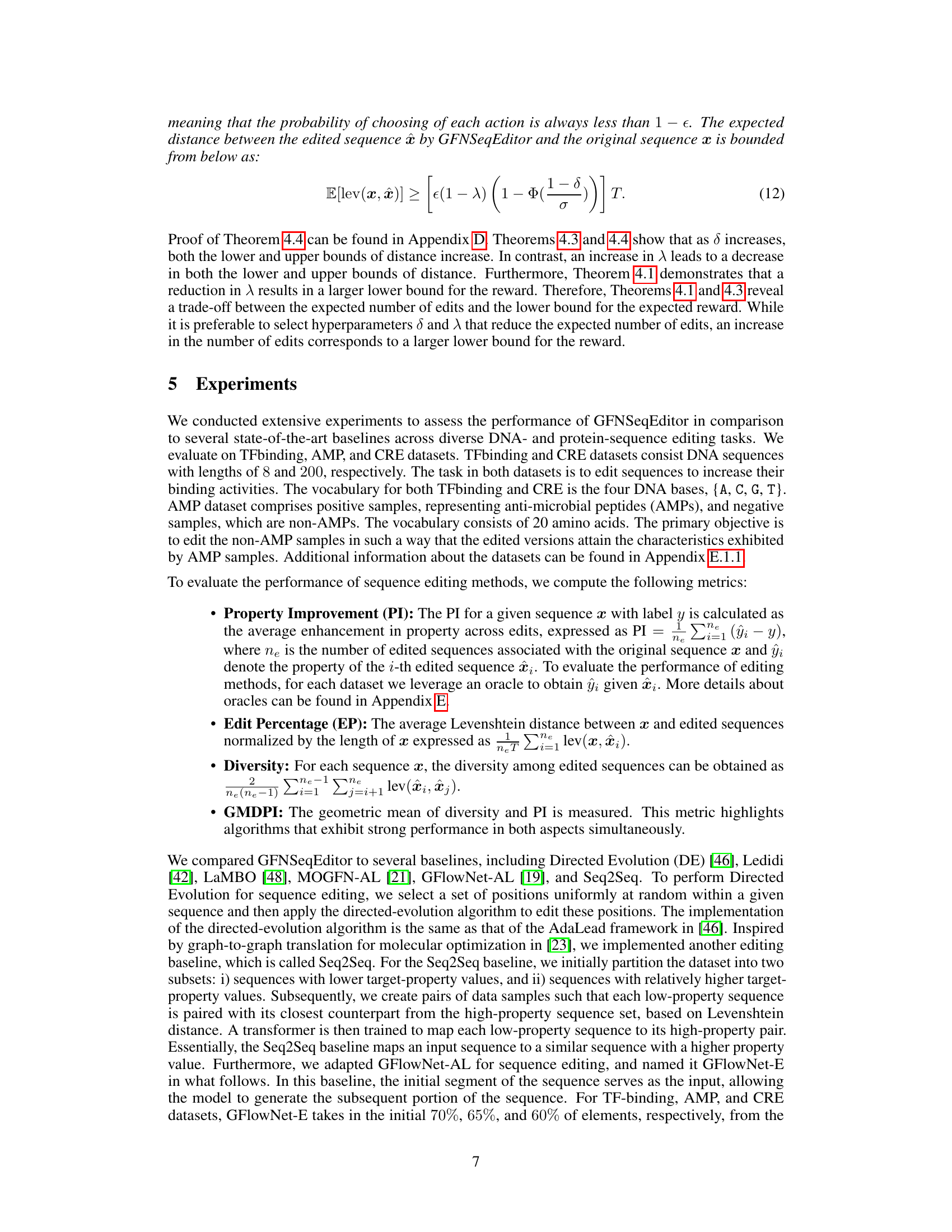

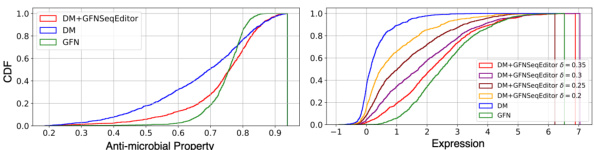

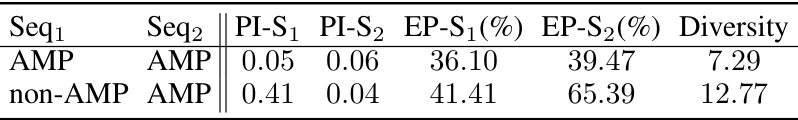

The figure shows the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) plots of the antimicrobial property for AMP and the expression for CRE datasets. The CDF plots compare the performance of three different methods: the diffusion model (DM), the GFlowNet (GFN), and the combination of the diffusion model and GFNSeqEditor (DM+GFNSeqEditor). The right-shifted curves for DM+GFNSeqEditor compared to DM and GFN indicate that this method generates more sequences with higher target properties (antimicrobial property for AMP and expression for CRE).

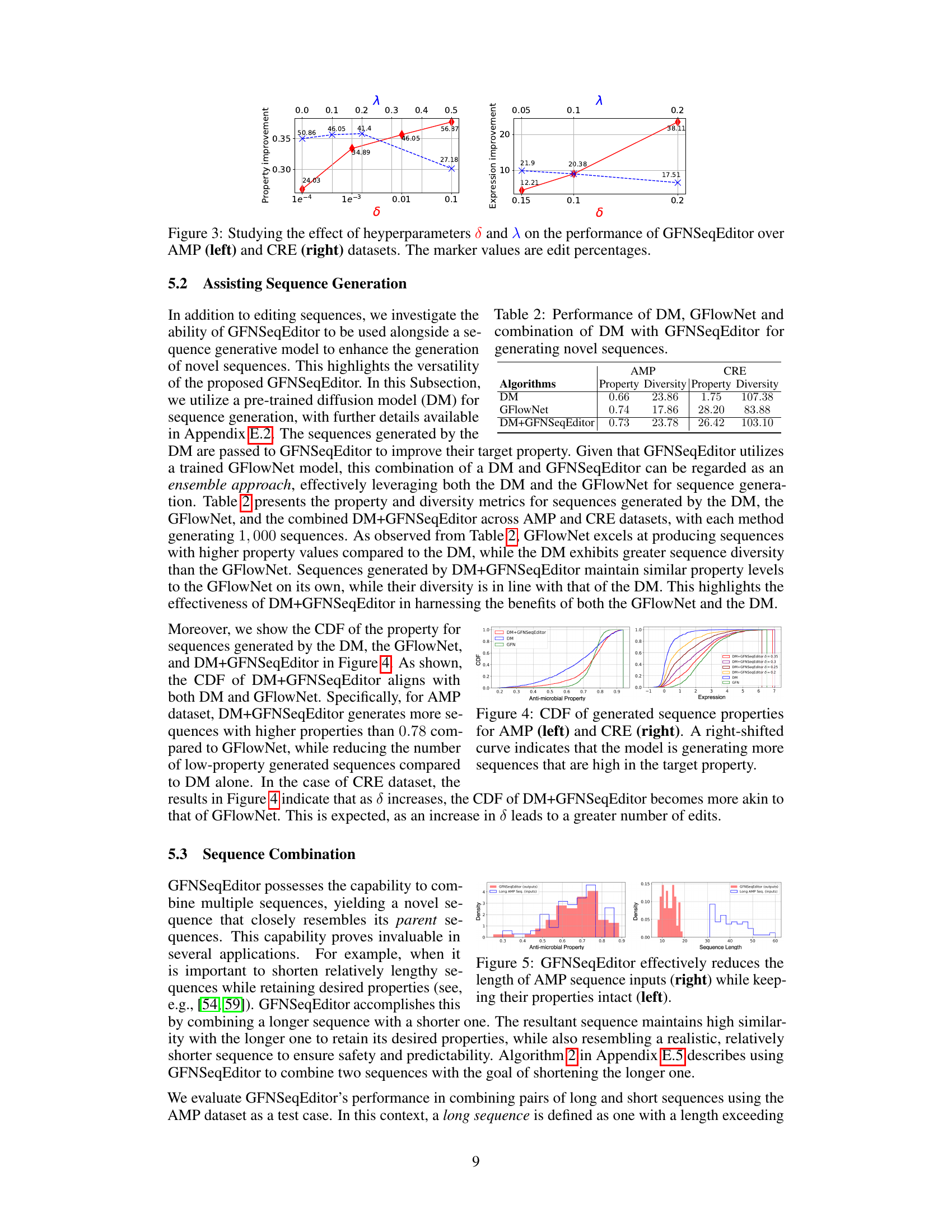

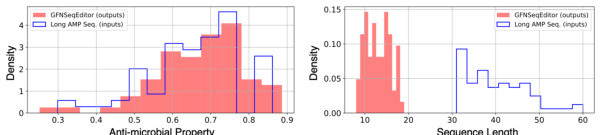

The figure shows the distribution of properties and lengths for original long AMP sequences and the AMP sequences edited by GFNSeqEditor. The left panel demonstrates that GFNSeqEditor maintains the high antimicrobial property of the original sequences while the right panel illustrates that it significantly shortens the length of the sequences. This shows that GFNSeqEditor is able to shorten long sequences and retain desirable properties.

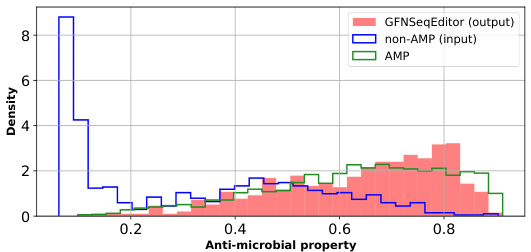

This figure shows the distribution of anti-microbial properties for three groups: the original non-AMP sequences, the AMP sequences, and the sequences generated by GFNSeqEditor after editing the non-AMP sequences. The x-axis represents the anti-microbial property, and the y-axis represents the density of sequences with that property. The figure visually demonstrates that GFNSeqEditor successfully shifts the distribution of the edited non-AMP sequences toward the distribution of the known AMP sequences, indicating its effectiveness in improving the desired property.

This figure shows the impact of the hyperparameter σ on both the diversity of generated sequences and the property improvement achieved by GFNSeqEditor. The plots display how changes in σ affect the trade-off between diversity and property improvement for two datasets, AMP (antimicrobial peptides) and CRE (cis-regulatory elements). The x-axis represents different values of σ, and the y-axes show diversity and property improvement, respectively. The plots demonstrate that increasing σ generally leads to increased diversity but reduced property improvement, suggesting a hyperparameter tuning trade-off.

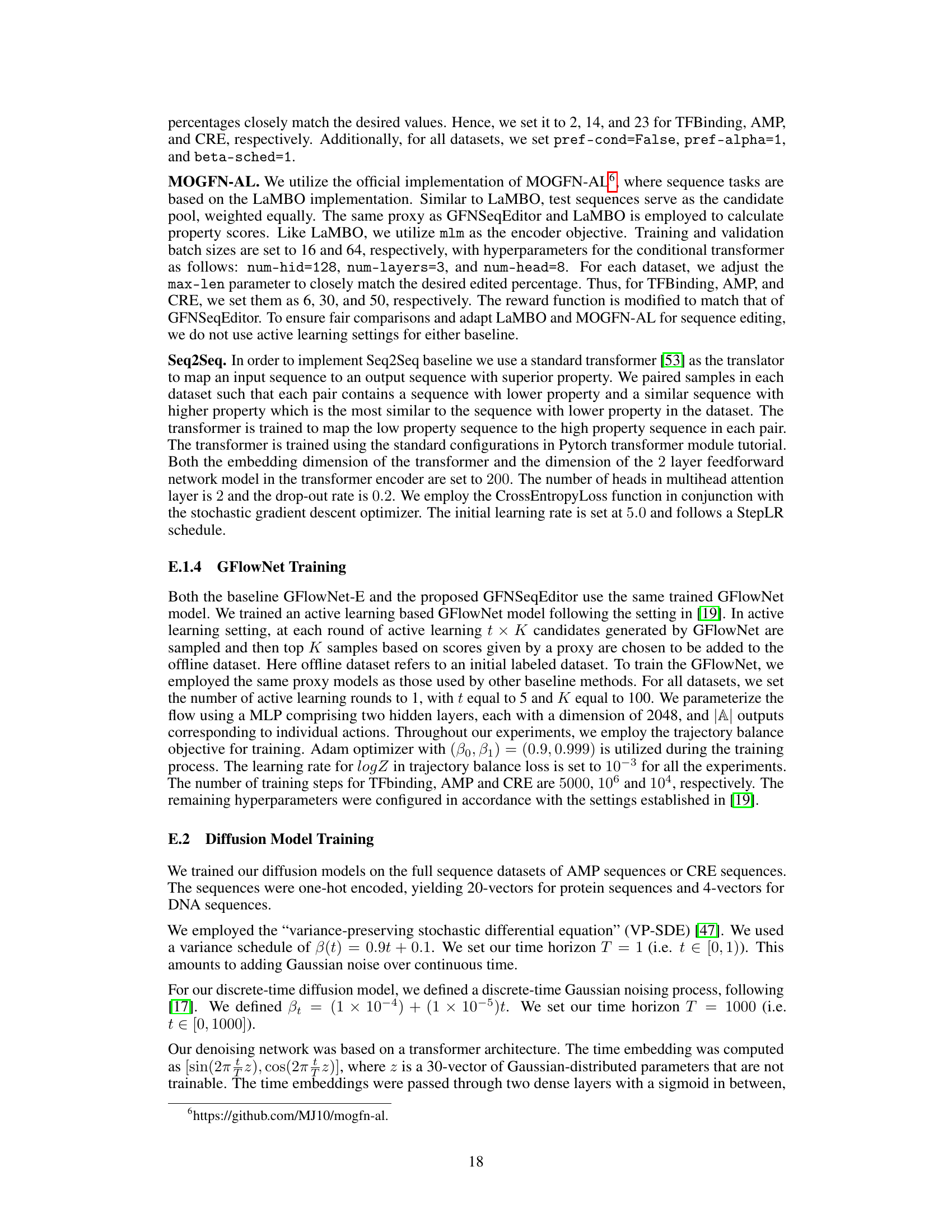

More on tables

This table presents a comparison of the performance of GFNSeqEditor against several baseline methods across three different datasets (TFbinding, AMP, and CRE). The comparison is based on four key metrics: Property Improvement (PI), Edit Percentage (EP), Diversity, and Geometric Mean of Property Improvement and Diversity (GMDPI). Higher values for PI, diversity, and GMDPI indicate better performance. The table highlights GFNSeqEditor’s superior performance in enhancing biological properties while keeping the number of edits relatively low.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the proposed GFNSeqEditor algorithm against several baseline methods for biological sequence editing tasks. The evaluation metrics include property improvement (PI), which measures the increase in the desired property after editing; edit percentage (EP), representing the proportion of edits made; diversity, reflecting the variation among the edited sequences; and geometric mean of property improvement and diversity (GMDPI), combining PI and diversity. The results are shown for three different datasets: TFbinding, AMP, and CRE, each representing a different biological sequence editing problem.

This table compares the performance of the proposed GFNSeqEditor algorithm against several baseline methods for biological sequence editing. The comparison is done across three datasets (TFbinding, AMP, and CRE) using four metrics: Property Improvement (PI), Edit Percentage (EP), Diversity, and Geometric Mean of Property Improvement and Diversity (GMDPI). Higher values for PI, diversity, and GMDPI indicate better performance. The edit percentage (EP) was kept roughly consistent across algorithms for fair comparison.

This table presents a comparison of the performance of the GFNSeqEditor algorithm against several baseline methods across three different datasets (TFbinding, AMP, and CRE). The comparison is based on four key metrics: Property Improvement (PI), Edit Percentage (EP), Diversity, and Geometric Mean of Property Improvement and Diversity (GMDPI). Higher values for PI, Diversity, and GMDPI indicate better performance. The Edit Percentage is kept roughly consistent across all algorithms for a fair comparison.

This table compares the performance of the proposed GFNSeqEditor algorithm to several baseline algorithms on three different datasets: TFbinding, AMP, and CRE. For each dataset and algorithm, it presents four key metrics: Property Improvement (PI), Edit Percentage (EP), Diversity, and Geometric Mean of Property Improvement and Diversity (GMDPI). The goal is to show GFNSeqEditor’s superior performance in improving the desired properties of biological sequences while keeping the number of edits low and ensuring diversity in the results. Higher values for PI, diversity, and GMDPI are preferred.

Full paper#