TL;DR#

Many machine learning applications require models robust to real-world data shifts. Existing methods often assume full knowledge of possible shifts, which is unrealistic. This limits their effectiveness and necessitates a more practical approach. The paper addresses this gap by tackling partially identifiable robustness, where only some aspects of the shifts are known.

This research introduces a new risk measure called the ‘identifiable robust risk’, representing the best achievable robustness under partial information. The authors demonstrate the limitations of existing methods using this new risk measure and propose a new method to achieve optimal robustness in such settings. Their findings offer a more realistic perspective on robustness and provide a more accurate evaluation method, applicable to real-world scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning and related fields because it addresses the critical issue of robustness under partial identifiability, a previously underexplored area. The findings challenge existing assumptions and methods, offering a new framework and risk measure for evaluating and improving robustness in real-world applications where complete information about the data distribution is unavailable. This work opens new avenues for theoretical and empirical investigation, particularly in the areas of causal inference and domain adaptation.

Visual Insights#

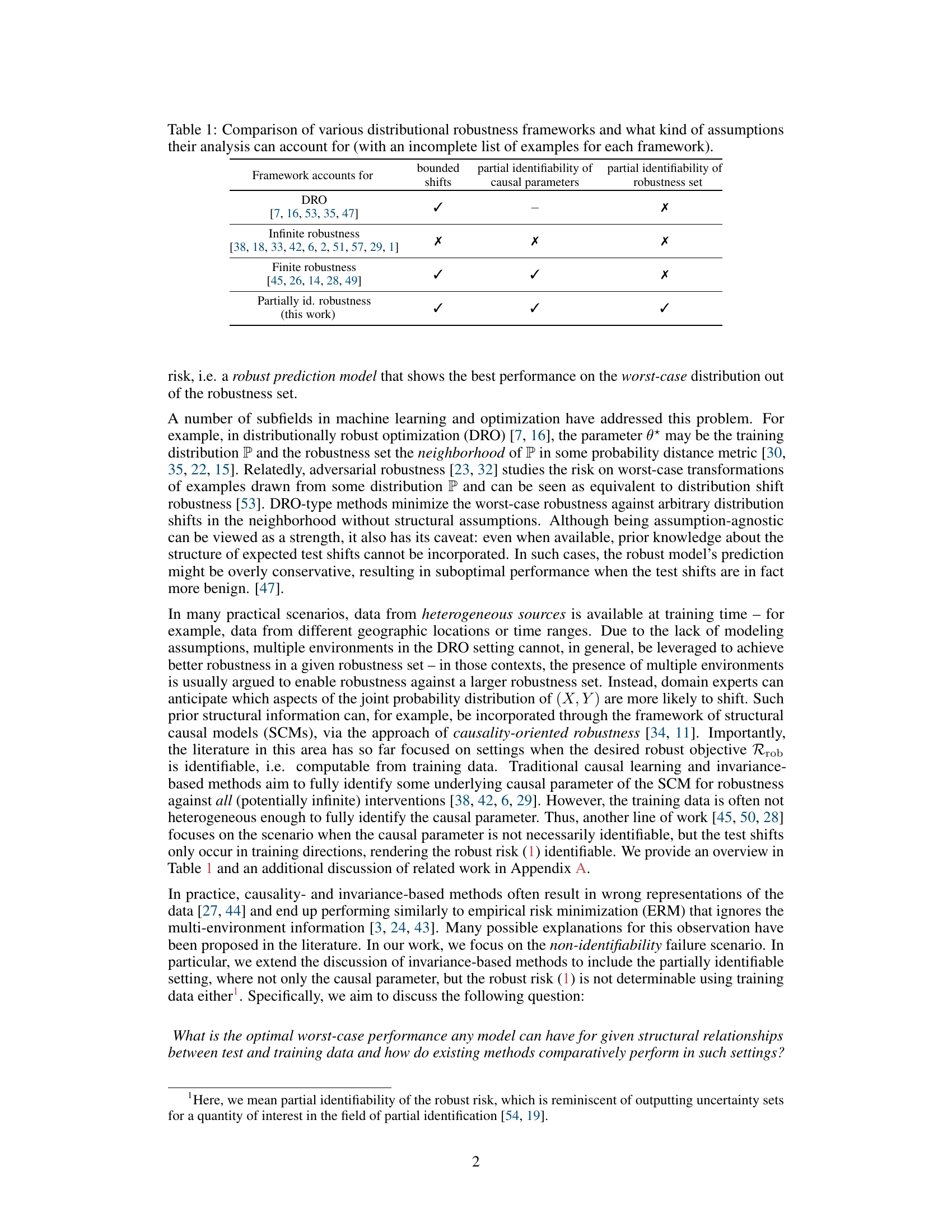

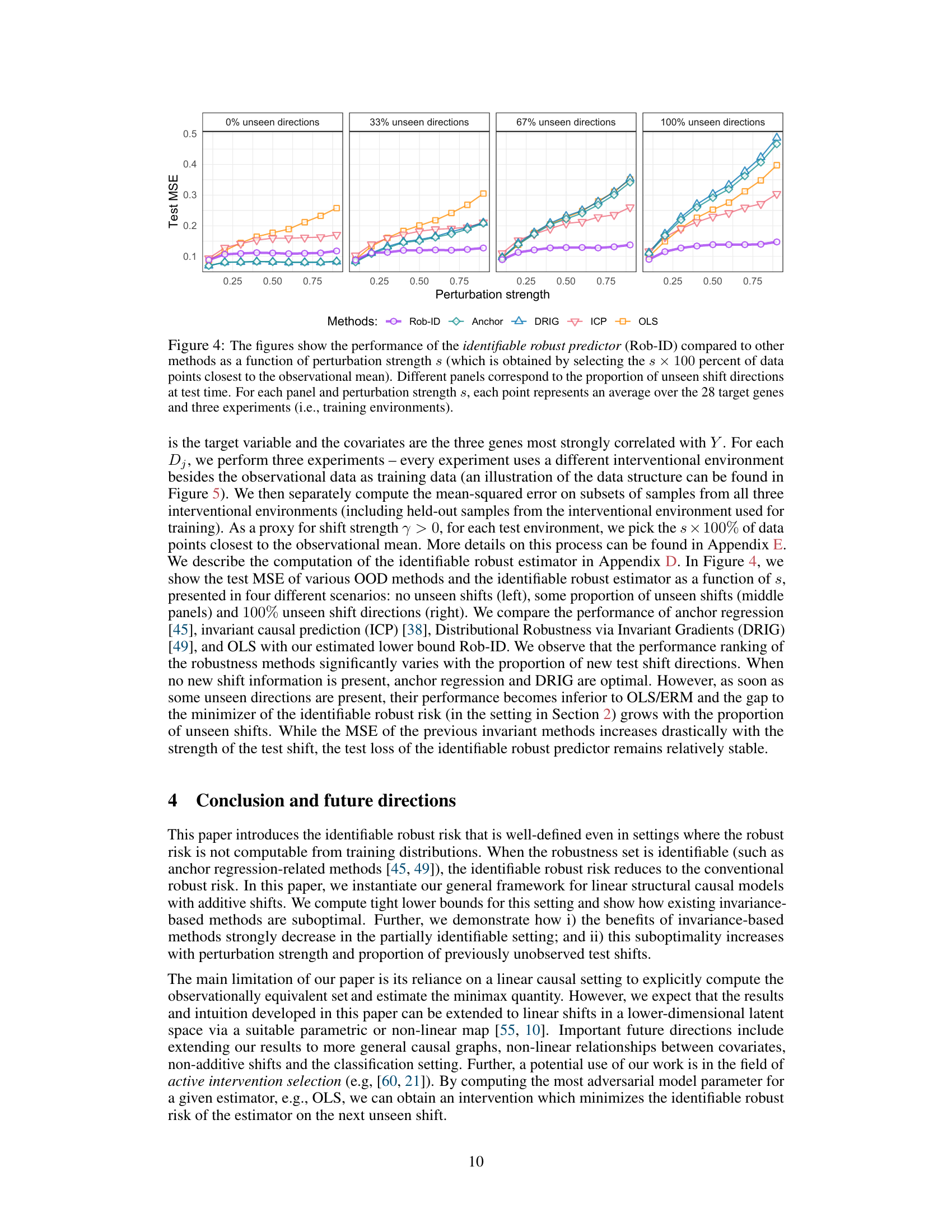

🔼 This figure shows the causal graph and the corresponding structural causal model (SCM) equations for the data generating process. The SCM describes how observed variables (covariates Xe and target variable Ye) are generated from unobserved variables: additive environmental shifts Ae and confounders H. The solid circles represent observed variables, while dashed circles represent unobserved variables. Bidirectional arrows indicate that the relationship between two nodes can be in either direction. This model is used to represent the data and the additive environment shifts that are the basis of the research.

read the caption

Figure 1: (Left) Causal graph corresponding to the SCM in Equation (3). Observed variables (Xe, Ye) are indicated by solid circles while unobserved variables, namely the additive shift Ae and confounders H, are shown in dashed circles. Note that here, bidirectional edges indicate that the relationship between two nodes can be in either direction.

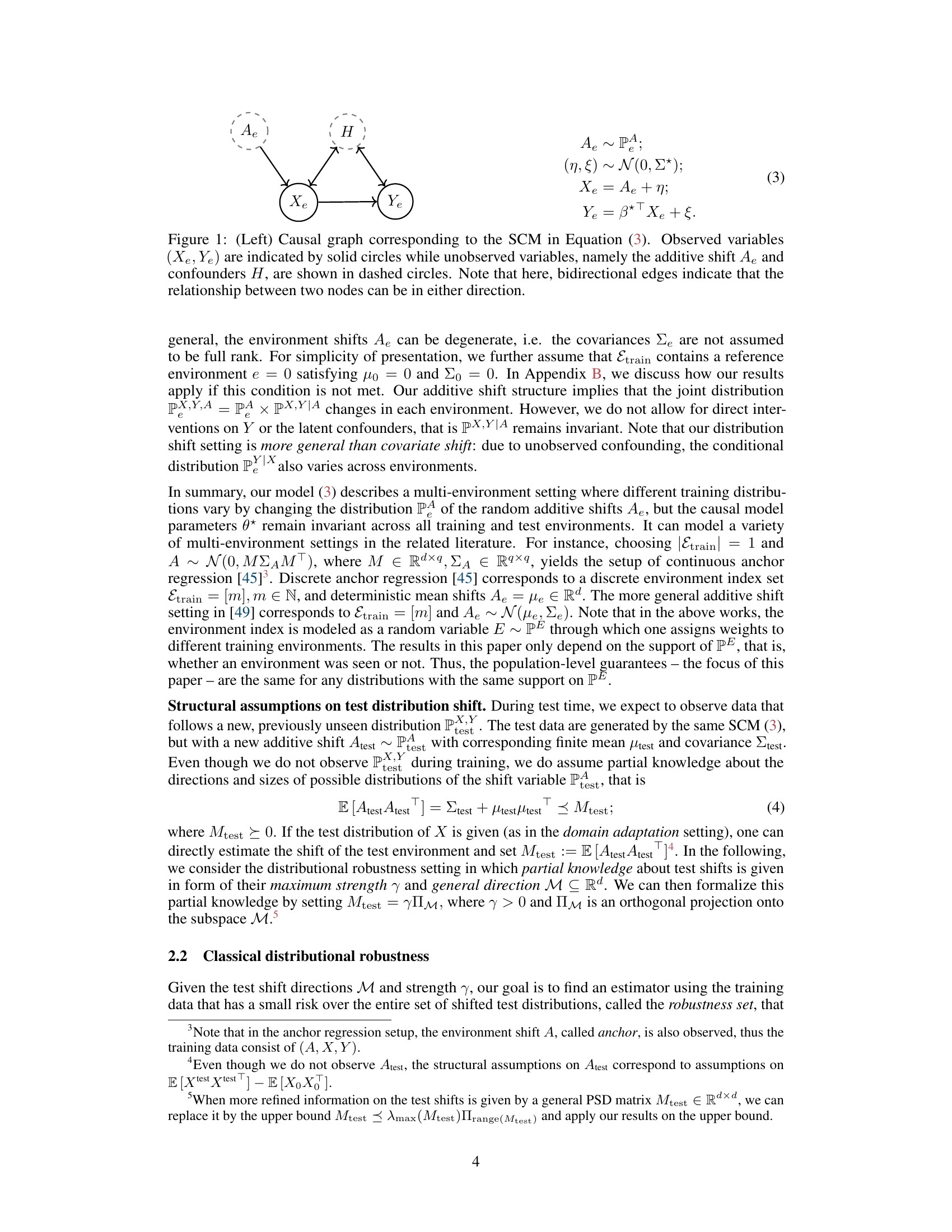

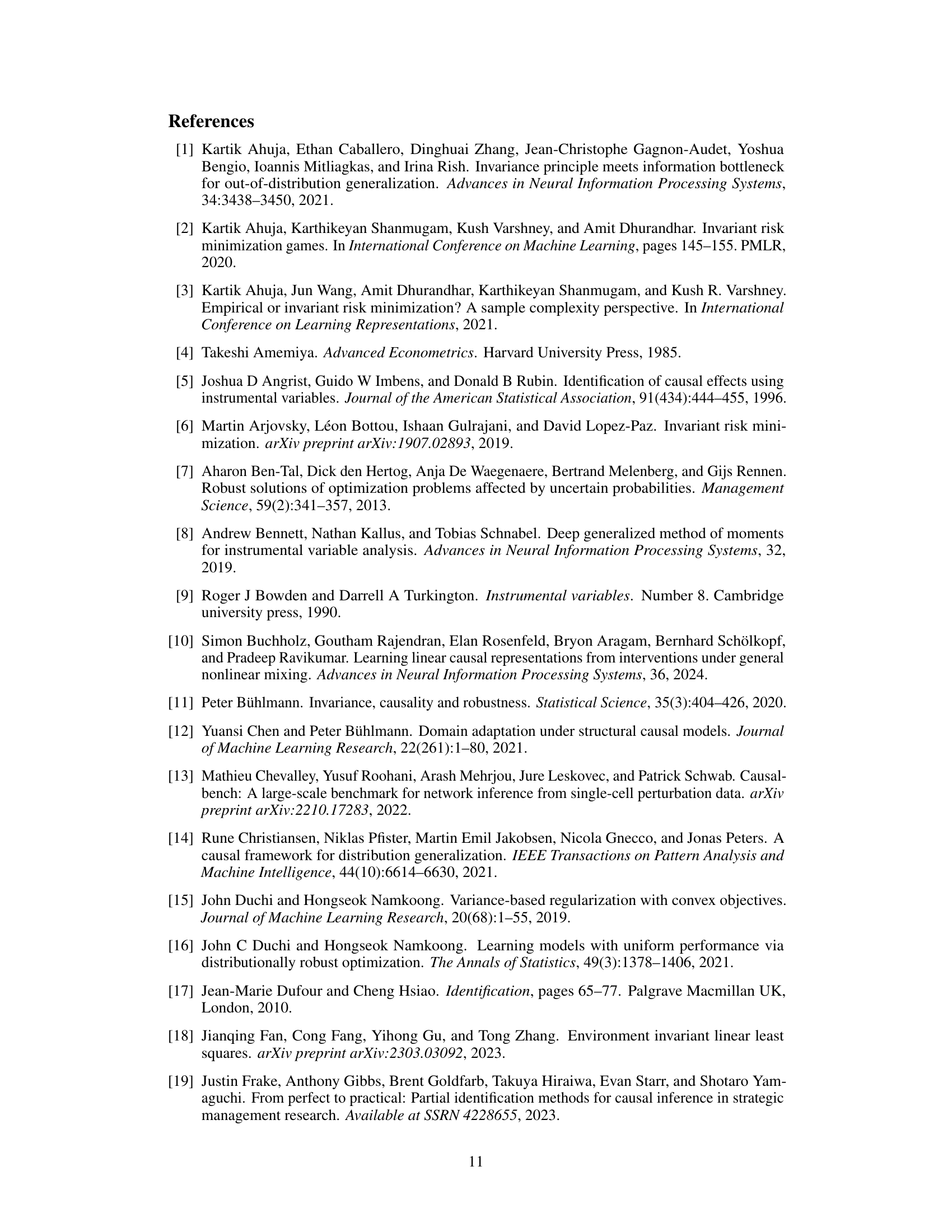

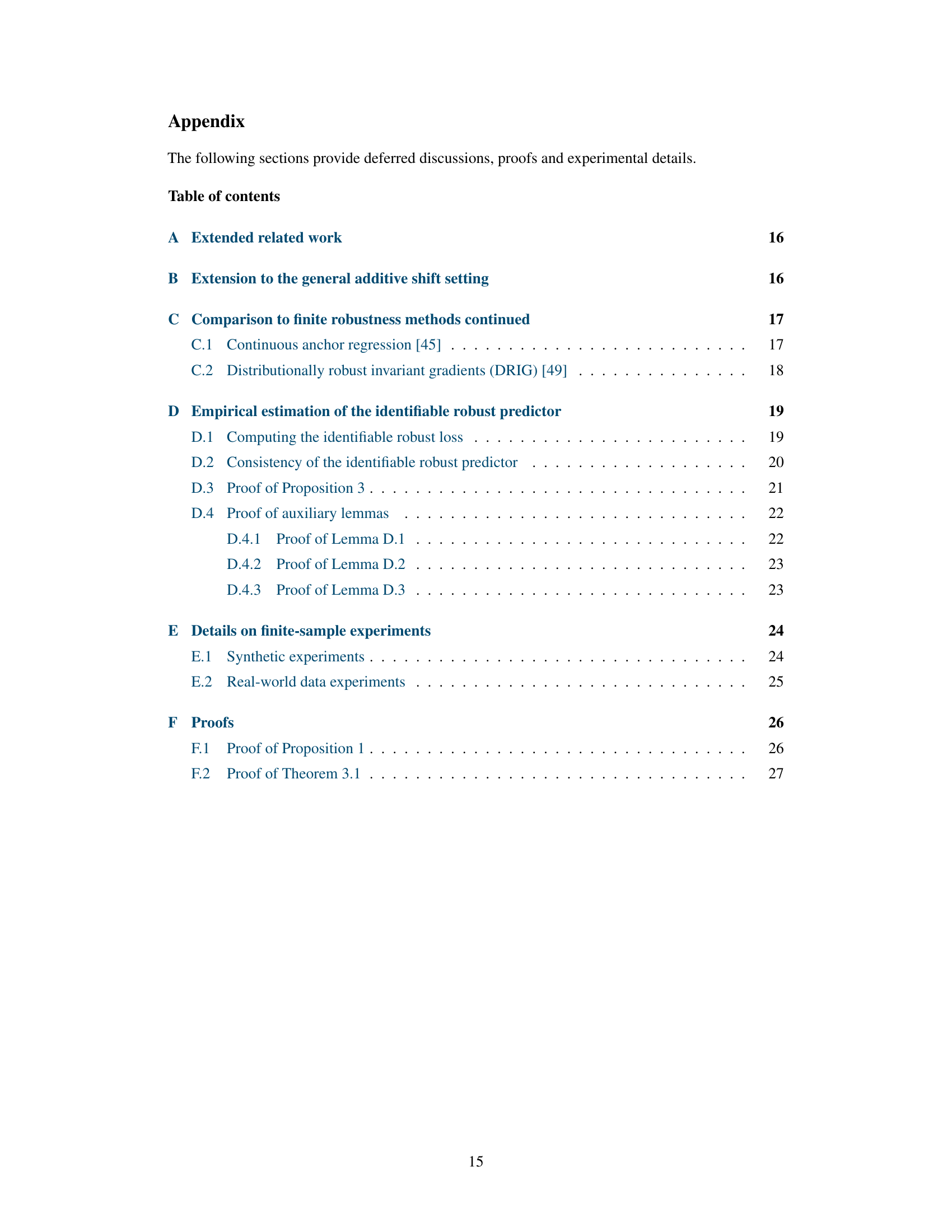

🔼 The table compares four different distributional robustness frameworks: DRO, infinite robustness, finite robustness, and partially identifiable robustness (the authors’ contribution). For each framework, it indicates whether the framework’s analysis can account for bounded shifts, partial identifiability of causal parameters, and partial identifiability of the robustness set. A checkmark (✓) means the framework accounts for the property; an X means it does not. The table helps to situate the authors’ proposed framework (partially identifiable robustness) within the existing literature and highlights its unique contributions.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of various distributional robustness frameworks and what kind of assumptions their analysis can account for (with an incomplete list of examples for each framework).

In-depth insights#

Partial ID Robustness#

The concept of ‘Partial ID Robustness’ introduces a crucial nuance to distributional robustness by acknowledging that the worst-case distribution, or the “robust risk,” might not be fully identifiable from training data. This partial identifiability arises when the available data is insufficient to fully characterize all possible distribution shifts, leading to a set of plausible robust risks. The key contribution here is the introduction of the “identifiable robust risk,” which represents the supremum of all possible true robust risks consistent with the observed training data. This provides an algorithm-independent measure of achievable robustness in partially identifiable scenarios, allowing for a more realistic and less conservative evaluation of methods. The framework also allows for comparing the performance of existing methods in such settings, highlighting their sub-optimality and demonstrating the benefit of considering partial identifiability.

Linear SCMs#

Linear Structural Causal Models (SCMs) offer a powerful framework for analyzing causal relationships, especially within the context of this research paper which focuses on distributional robustness. Linearity simplifies the mathematical treatment, allowing for a more tractable analysis of how interventions or distribution shifts affect the model’s predictions. This simplification, however, comes at a cost. Real-world systems are rarely perfectly linear, and the assumptions of linearity might not fully capture the complex interactions and non-linear dependencies inherent in many real-world scenarios. The paper leverages linear SCMs to gain theoretical insights into the achievable robustness under partially identified robust risks. Specifically, the linear SCM framework allows for the explicit quantification of the identified robust risk and minimax quantities, offering a mathematical foundation for understanding the effect of partially identified robustness. Nonetheless, the use of linear SCMs is a limiting factor because real-world problems often deviate significantly from this linear structure. Further research should investigate how these theoretical findings extend to nonlinear settings.

Minimax Risk#

The concept of “Minimax Risk” in a distributional robustness context centers on finding the optimal strategy for minimizing the worst-case risk under uncertainty. It acknowledges that the true data distribution is unknown, lying within a set of possible distributions. The minimax approach seeks a model that performs well even under the least favorable distribution within this set, thus offering a robust solution against distributional shifts. This approach contrasts with standard risk minimization, which assumes a known or readily estimable distribution. A key challenge is identifying the set of possible distributions accurately. This is tackled by considering partial identifiability of the robust risk, recognizing that the training data may not contain enough information to fully characterize the possible shifts. The minimax framework, when applied to partially identifiable robustness scenarios, seeks the best achievable performance, even though the exact worst-case scenario remains unknown. This framework is particularly relevant in safety-critical applications, where robustness against unseen data distributions is paramount.

Empirical Findings#

An ‘Empirical Findings’ section in a research paper would present the results of experiments designed to test the paper’s core claims. A robust empirical section needs to clearly describe the experimental setup, including data sources, algorithms used, evaluation metrics, and handling of statistical significance. The key is demonstrating alignment between theoretical predictions and actual observations. Any discrepancies should be discussed thoroughly, exploring potential causes such as limitations in the experimental design or assumptions made during the theoretical analysis. A strong section will also compare the performance of the proposed method with existing baselines, providing quantitative evidence of its effectiveness or limitations. Visualizations (graphs and tables) are crucial for communicating results effectively, especially when dealing with complex datasets. The overall presentation should be clear, concise, and easy to interpret, allowing readers to understand the implications of the empirical results for the paper’s claims and broader research context. The quality of the empirical findings is vital to the paper’s credibility and impact, as it directly validates or refutes the theoretical underpinnings.

Future Directions#

The paper’s “Future Directions” section would ideally expand upon the limitations of the current linear causal model framework. Extending the framework to handle nonlinear relationships and more complex causal graphs is crucial for broader applicability. Addressing the challenges of partial identifiability in more realistic scenarios, beyond the linear SCM setting, is also key. This could involve developing new methods for estimating the identifiable robust risk or proposing alternative robustness measures better suited to high-dimensional, non-linear problems. The authors should also explore alternative approaches to characterizing the robustness set and investigate how different types of prior information might improve robustness guarantees. Finally, developing techniques to efficiently handle high-dimensional data and addressing the computational cost of the proposed methods would make the framework more practical for real-world applications. The incorporation of techniques for handling uncertainty in the parameter estimates and exploration of other loss functions would lead to a more robust and broadly applicable framework.

More visual insights#

More on figures

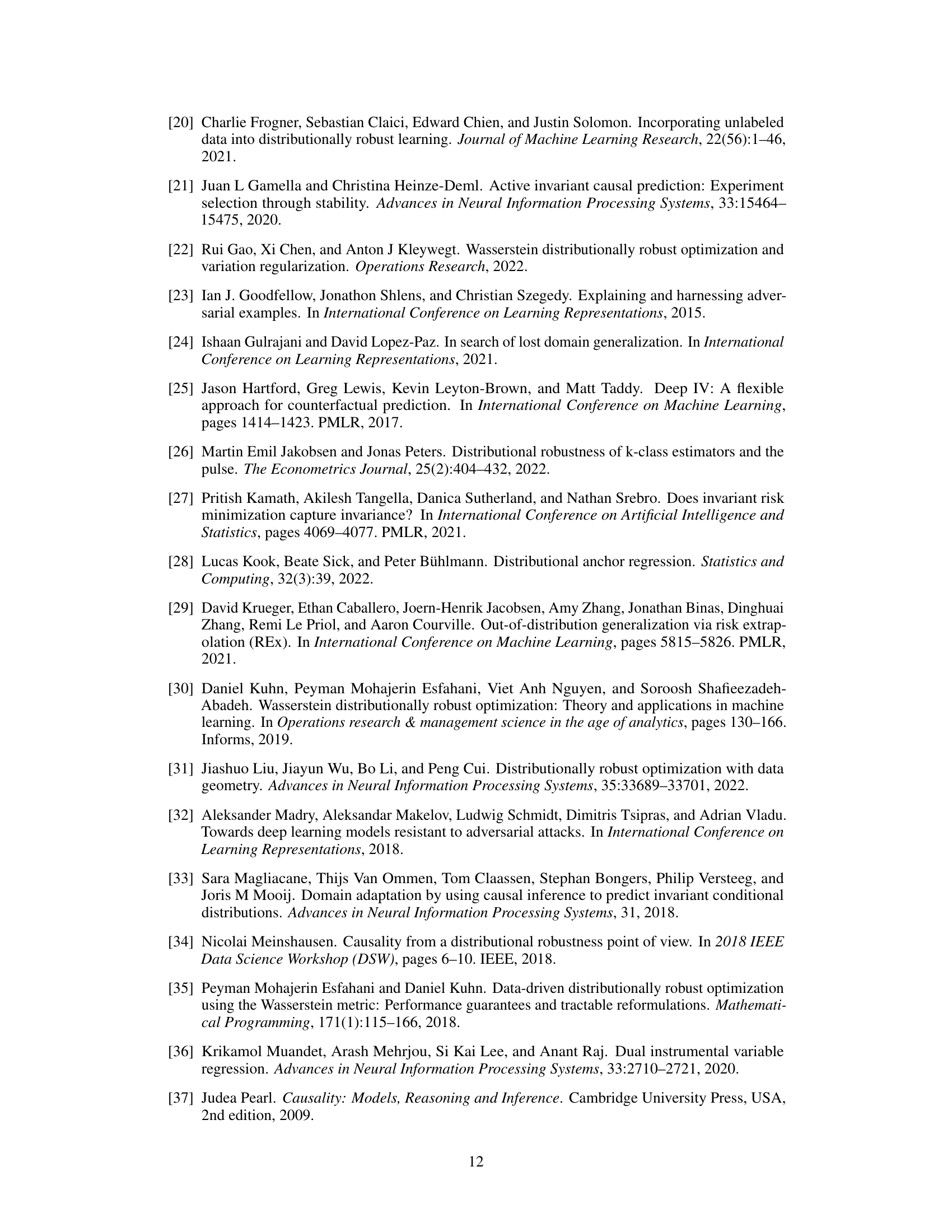

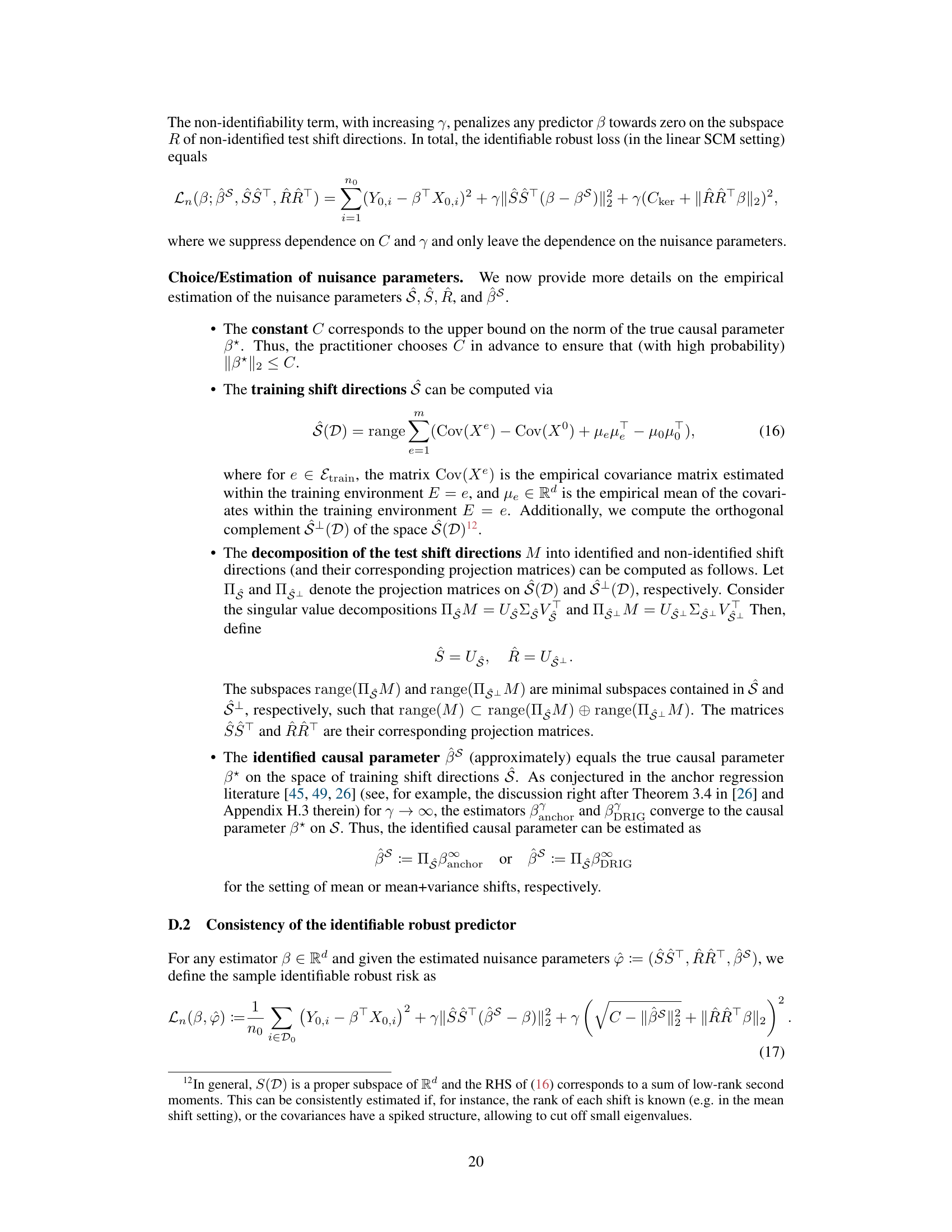

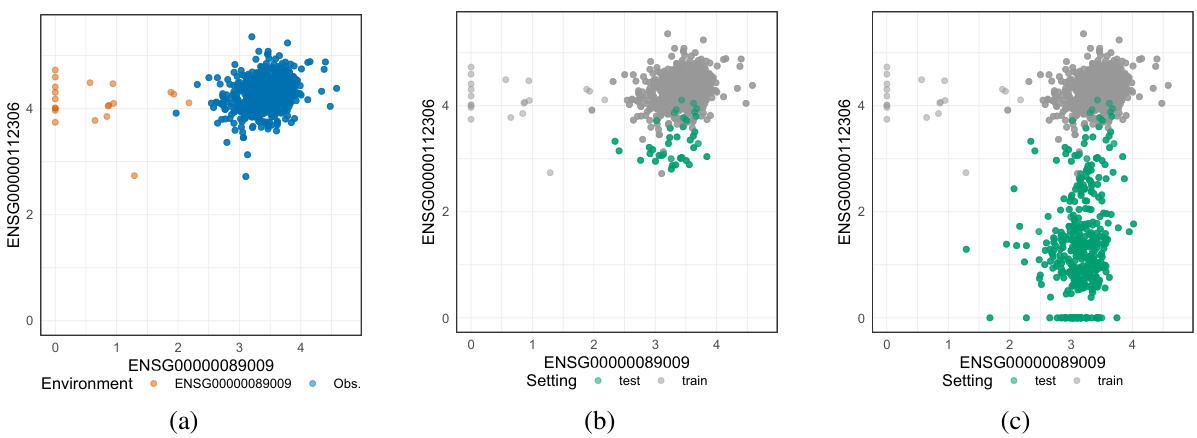

🔼 This figure illustrates the difference between identifiable and partially identifiable robustness settings. In the identifiable setting (a), the test shift directions are fully contained within the span of the training shift directions, resulting in the robust risk being point-identified. However, in the partially identifiable setting (b), test-time shifts introduce new directions, making the robust risk only set-identifiable. The figure shows how the identifiable robust risk is a subset of all possible true robust risks, highlighting the uncertainty introduced by partially identifiable shifts.

read the caption

Figure 2: Relationship between identifiability of the model parameters and identifiability of the robust risk. (a) The classical scenario where the test shift directions Mseen are contained in the span of training shifts so that the robust risk and thus its minimizer are point-identified. (b) The more general scenario of this paper, where the shift directions during test time Mgen can contain new shift directions and the robust risk can only be set-identified.

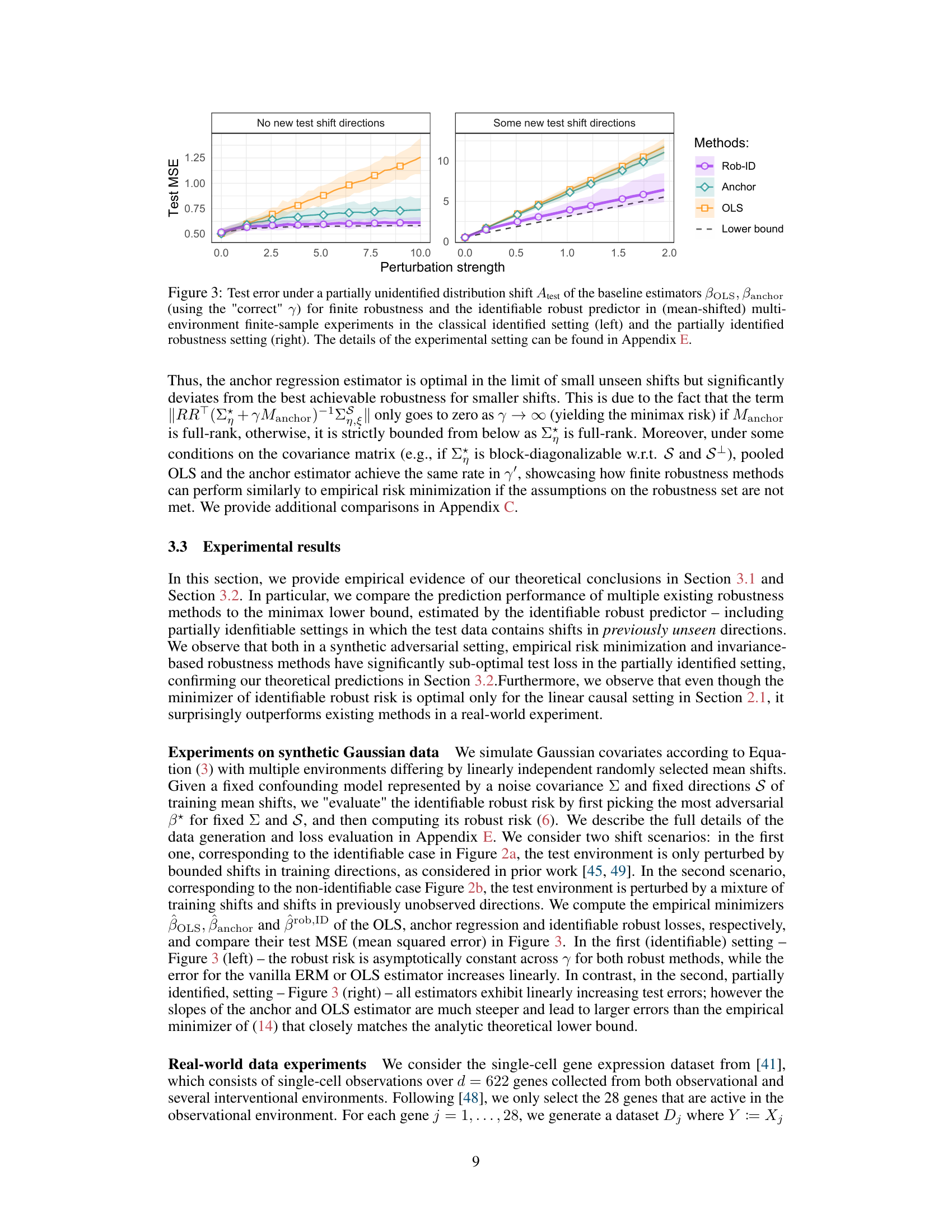

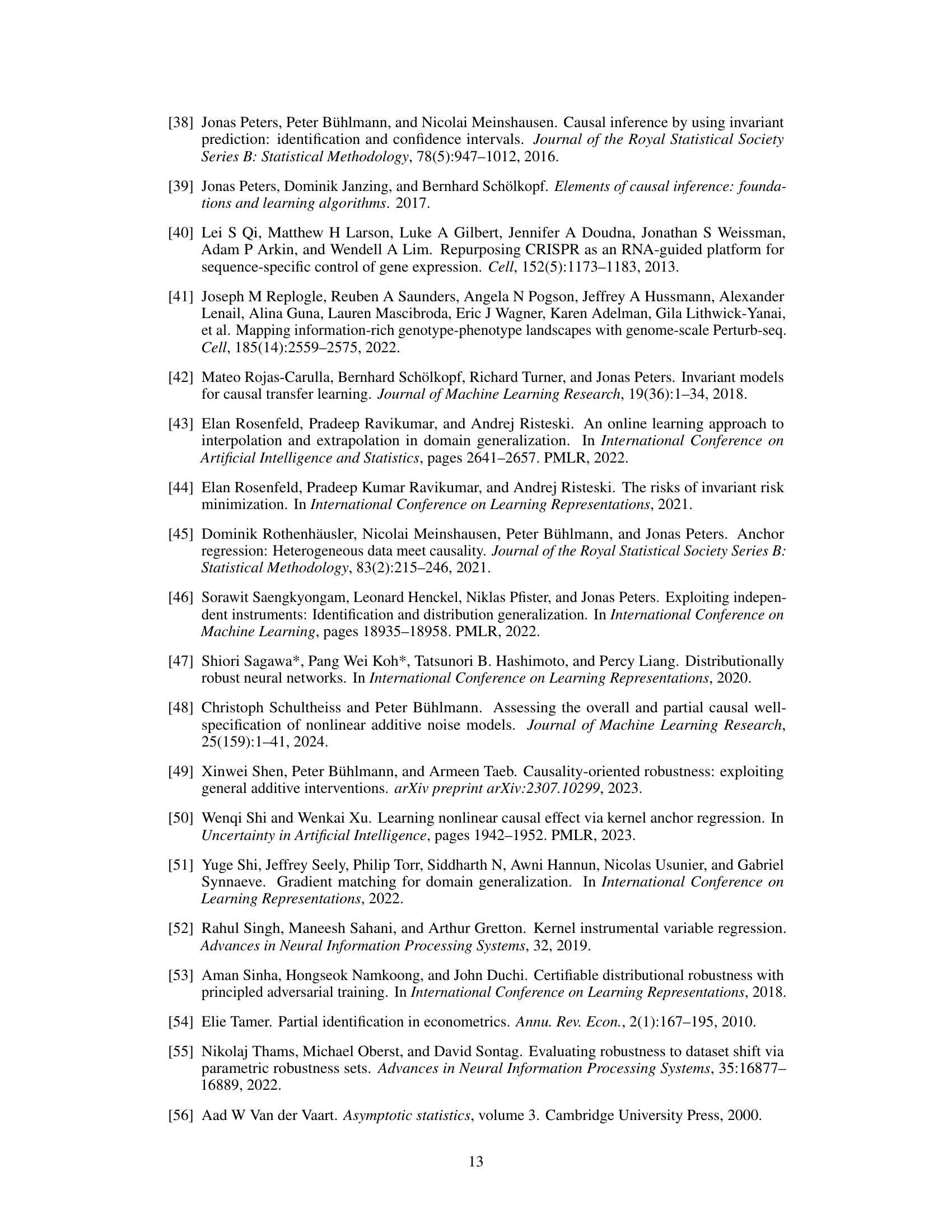

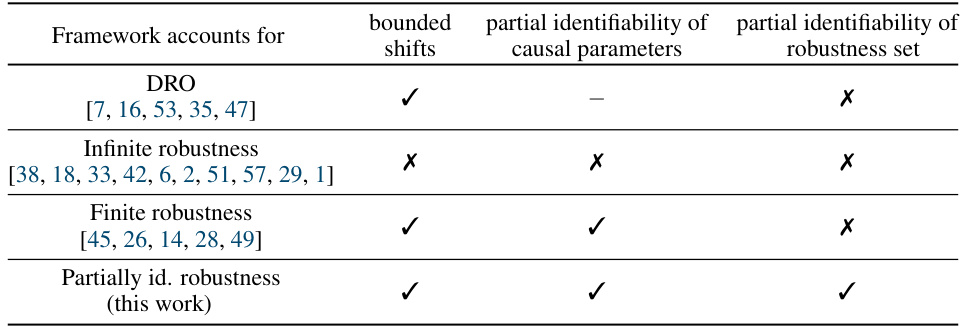

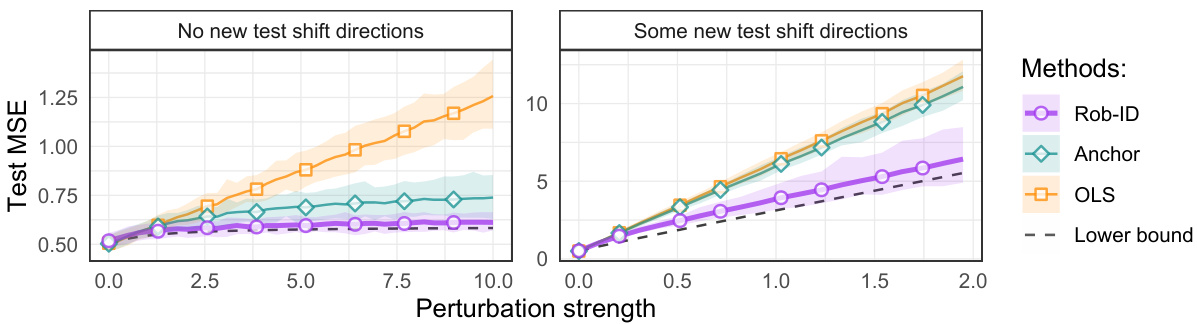

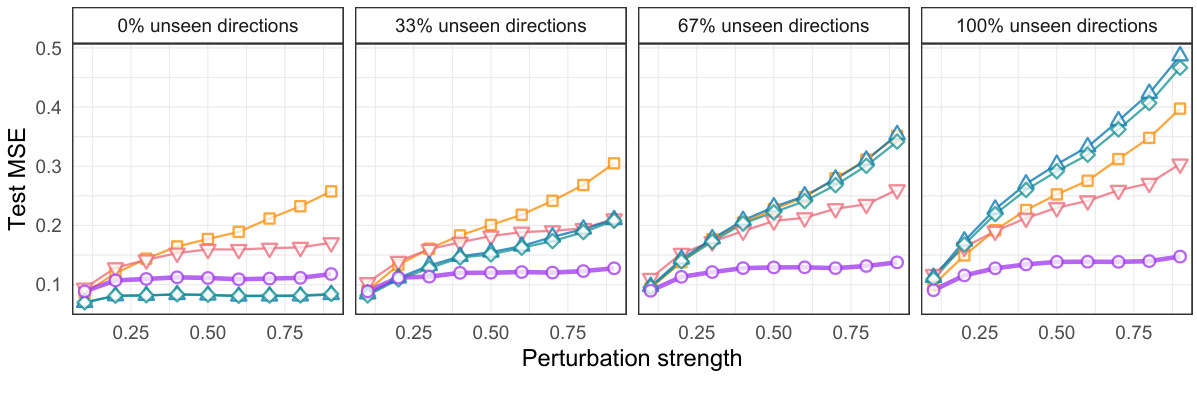

🔼 The figure shows the test error (MSE) of different methods under partially identified distribution shift. In the classical identified setting (left panel), the test shift is only in the directions already seen during training; while in partially identified setting (right panel), the test shift includes new directions not seen during training. The plot compares the identifiable robust predictor with existing methods like OLS and anchor regression, demonstrating the impact of unseen directions on the test error.

read the caption

Figure 3: Test error under a partially unidentified distribution shift Atest of the baseline estimators BOLS, Banchor (using the \'correct\' γ) for finite robustness and the identifiable robust predictor in (mean-shifted) multi-environment finite-sample experiments in the classical identified setting (left) and the partially identified robustness setting (right). The details of the experimental setting can be found in Appendix E.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of several methods (identifiable robust predictor, anchor regression, OLS) on synthetic data under two different settings: one with only previously seen shifts during testing and the other with both previously seen and unseen shifts. The results show that in the presence of unseen test-time shifts, the identifiable robust predictor consistently outperforms the other methods.

read the caption

Figure 3: Test error under a partially unidentified distribution shift Atest of the baseline estimators BOLS, Banchor (using the \'correct\' γ) for finite robustness and the identifiable robust predictor in (mean-shifted) multi-environment finite-sample experiments in the classical identified setting (left) and the partially identified robustness setting (right). The details of the experimental setting can be found in Appendix E.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of three methods (OLS, Anchor regression, and identifiable robust predictor) under two different settings: one where test data shifts are within the span of training shifts, and another where the test data contains unseen shifts. The left panel shows results for the case with only seen shifts, while the right panel shows results for the case with both seen and unseen shifts. The figure demonstrates that the identifiable robust predictor outperforms the other methods when there are unseen shifts, confirming the theoretical results of the paper.

read the caption

Figure 3: Test error under a partially unidentified distribution shift Atest of the baseline estimators BOLS, Banchor (using the \'correct\' γ) for finite robustness and the identifiable robust predictor in (mean-shifted) multi-environment finite-sample experiments in the classical identified setting (left) and the partially identified robustness setting (right). The details of the experimental setting can be found in Appendix E.

Full paper#