TL;DR#

Securely performing inference on transformer models using two-party computation (2PC) is challenging due to the computational cost of matrix multiplications and complex activation functions. Existing 2PC approaches are slow and inefficient because of the heavy use of expensive homomorphic encryption and window encoding. This significantly limits the practical deployment of secure AI in privacy-sensitive applications.

This paper presents Nimbus, a novel framework that addresses these limitations. Nimbus proposes a new client-side outer product protocol for linear layers and a distribution-aware polynomial approximation for non-linear activation functions. These innovations result in considerable performance gains. Experiments show significant improvements in end-to-end performance, particularly a 2.7x to 4.7x speedup in BERT base inference compared to existing methods. The approach offers a substantial improvement for the privacy-preserving deployment of transformer-based AI models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in secure multi-party computation and privacy-preserving machine learning. It offers significant performance improvements for a critical task—secure inference on transformer models—which is vital for deploying AI in privacy-sensitive applications. The techniques presented, particularly the novel COP protocol and distribution-aware polynomial approximation, open new avenues for optimizing secure computation and can accelerate progress in related areas like federated learning and differential privacy.

Visual Insights#

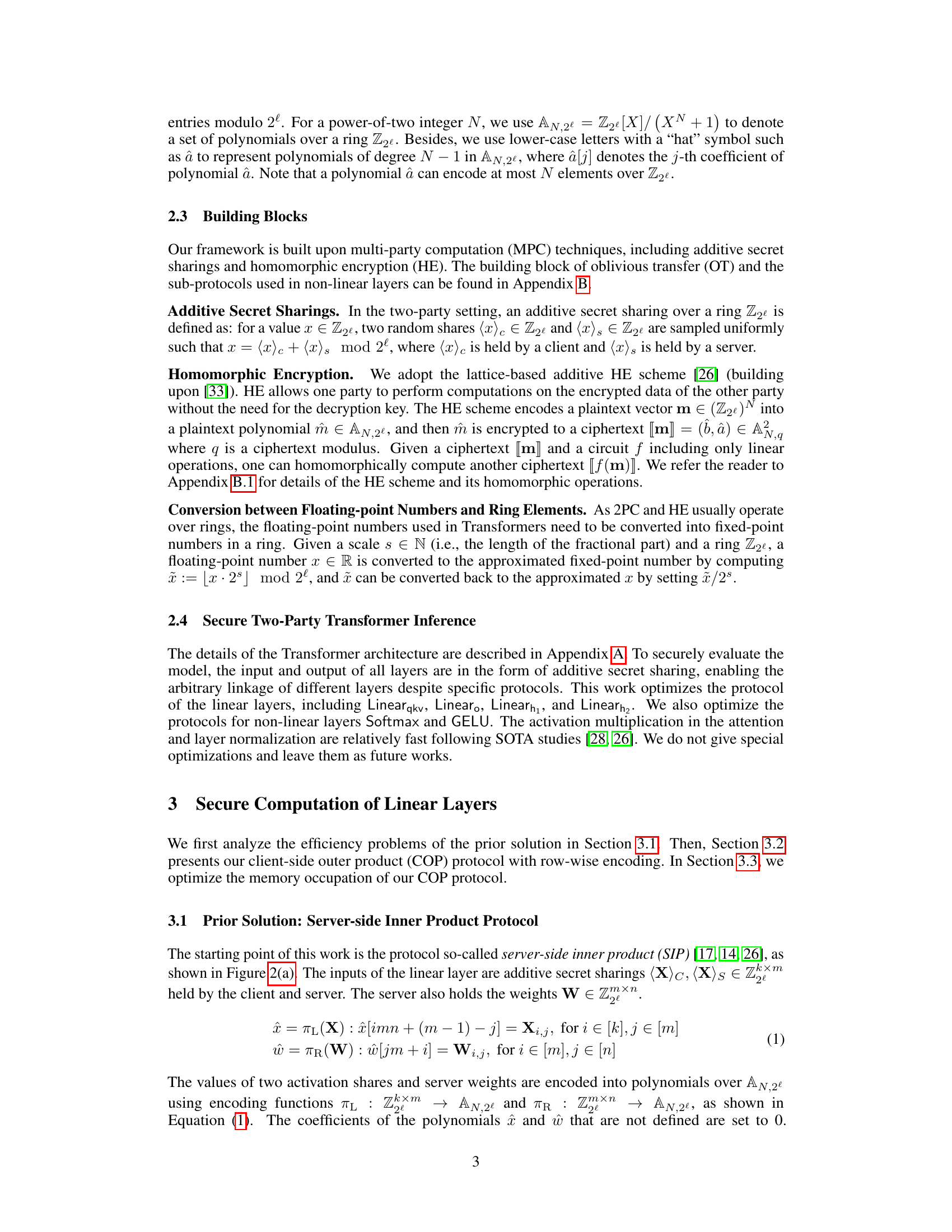

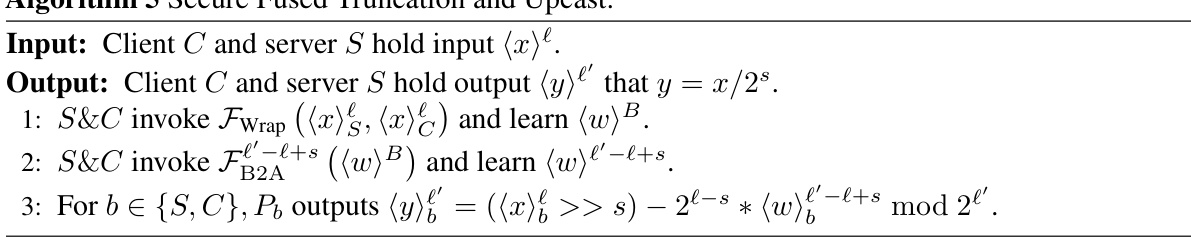

🔼 This figure compares two different protocols for secure matrix multiplication in the context of two-party computation: the Server-side Inner Product (SIP) protocol and the Client-side Outer Product (COP) protocol. The SIP protocol involves multiple rounds of communication and computationally expensive operations like Number Theoretic Transform (NTT) and Inverse NTT (INTT) in both the online and setup phases. The COP protocol, by contrast, leverages the static nature of model weights to shift the computationally expensive steps to the setup phase and reduce communication overhead during the online phase. This results in improved efficiency and latency for secure linear layer computations in transformer models.

read the caption

Figure 2: Two rows represent the client and server operations, respectively. The inefficient parts that are accelerated are marked by dashed boundaries. The input communication is shifted as a one-time setup, and the output ciphertexts are compact. The expensive NTT/INTT operations at the online stage are also reduced.

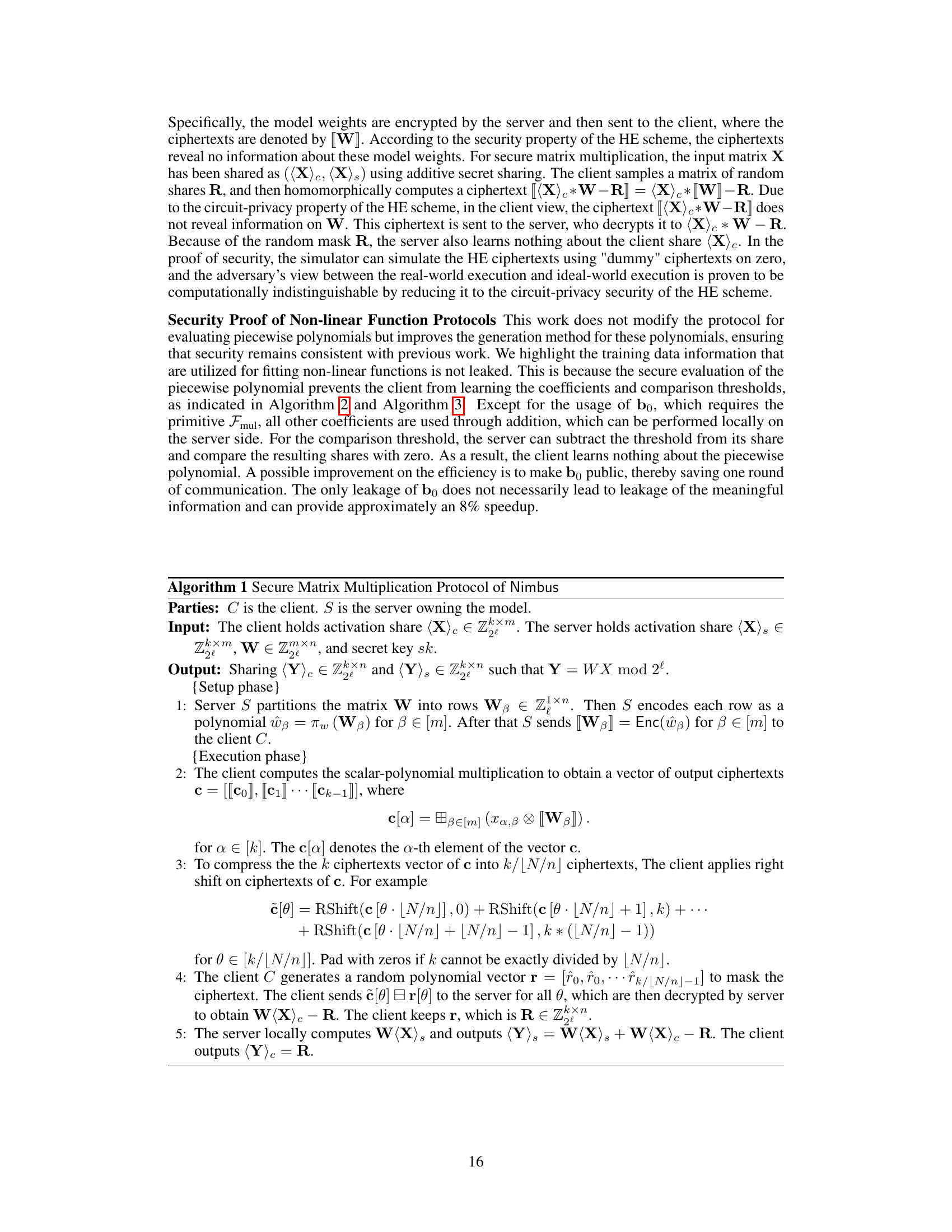

🔼 This table compares the computation and communication complexities of the server-side inner product (SIP) protocol and the proposed client-side outer product (COP) protocol for matrix multiplication in the context of secure two-party computation. It breaks down the comparison by the number of communicated ciphertexts and the computational complexities for both the server and client sides using homomorphic encryption. The complexities are expressed in Big O notation and depend on parameters like matrix dimensions (k, m, n) and window sizes (kw, mw, nw), with N representing the polynomial degree in the homomorphic encryption scheme.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the computation and communication for multiplication of two matrices with dimension k × m and m × n. kw, mw, nw are the window size corresponding to matrix dimensions.

In-depth insights#

Nimbus Framework#

The Nimbus framework, as envisioned, is a secure and efficient two-party inference framework designed for Transformer models. Its core innovation lies in addressing the performance bottlenecks of existing secure two-party computation (2PC) approaches, specifically targeting the computationally expensive matrix multiplications in linear layers and complex non-linear activation functions. The framework achieves this through a novel 2PC paradigm employing a Client-Side Outer Product (COP) protocol. This protocol leverages the static nature of model weights to minimize communication overhead and employs row-wise encoding to enhance efficiency. For non-linear layers, Nimbus cleverly utilizes the input distribution to enable a simpler piecewise polynomial approximation of functions like GELU and Softmax. This optimization is coupled with a novel protocol for efficient ring conversion, further enhancing both accuracy and performance. The overall result is a significant improvement in end-to-end performance for Transformer inference, compared to state-of-the-art methods, showcasing the framework’s potential in practical privacy-preserving applications.

COP Protocol#

The COP (Client-Side Outer Product) protocol is a significant contribution, improving the efficiency of secure matrix multiplication in the linear layers of transformer models. Instead of the conventional server-side approach, where the server performs computationally expensive operations on encrypted data, the COP protocol shifts the computation burden to the client. This is possible due to the static nature of model weights, allowing the server to send encrypted weights during the setup phase. The protocol then leverages row-wise encoding, which optimizes the matrix multiplication using outer products, resulting in compact ciphertexts and reduced communication rounds. The encoding approach directly uses plaintext activation shares from the client and the encrypted weights, avoiding the intermediate steps seen in previous window encoding methods, thus substantially reducing computation and communication costs. This efficiency gain is critical for practical, privacy-preserving transformer inference, making secure deployment of these powerful models more feasible.

Poly Approx#

Polynomial approximation, often abbreviated as ‘Poly Approx,’ is a crucial technique in machine learning, especially when dealing with complex functions like GELU and Softmax. Its core principle is to replace a computationally expensive or intractable function with a simpler polynomial expression. This simplification drastically improves the efficiency of secure two-party inference, a critical aspect of privacy-preserving machine learning. The trade-off, however, is a reduction in accuracy. Therefore, careful consideration is needed to balance the computational gains with the inevitable loss of precision. The success of Poly Approx hinges on two critical factors: the choice of polynomial degree (higher degree yields better accuracy but increases computational cost) and the strategy for fitting the polynomial to the target function (techniques like distribution-aware fitting optimize approximation efficiency by focusing computational resources where they matter most). Effectively, Poly Approx offers a powerful way to manage the inherent tension between accuracy and efficiency in secure computation. Furthermore, the selection of appropriate rings and precision levels in the numerical representation of the polynomials significantly impacts both accuracy and computational cost.

Performance Gains#

Analyzing performance gains in a research paper requires a multifaceted approach. We need to consider what aspects of performance improved, such as speed, accuracy, or resource usage (memory, energy). The magnitude of improvement should be assessed, presented as concrete numbers (e.g., X% faster, Y% more accurate). It’s crucial to understand the baseline against which gains are measured. The baseline should be clearly identified and ideally represent the current state-of-the-art or a relevant comparison. Furthermore, the paper must clearly state the methodology and metrics used to evaluate performance. This ensures reproducibility and allows for critical evaluation of the reported gains. Finally, a discussion of any limitations or trade-offs is essential. Faster performance may come at the cost of reduced accuracy, increased resource consumption, or applicability only to specific scenarios. A complete analysis incorporates all these elements for a holistic understanding of the performance achievements claimed in the paper.

Future Works#

Future work could explore several promising avenues. Extending Nimbus to support more complex Transformer architectures beyond BERT base, such as those with larger context windows or different attention mechanisms, would significantly broaden its applicability. Improving the efficiency of non-linear layer approximations remains crucial; investigating alternative low-degree polynomial approximations or exploring techniques like function decomposition could lead to more accurate and faster computations. Developing a secure inference framework for Transformer models using different cryptographic primitives beyond the chosen HE scheme would allow for a comparative analysis of performance and security trade-offs. Enhancing the security of the current framework against stronger adversarial models, potentially moving beyond semi-honest adversaries, would greatly enhance the robustness of Nimbus in real-world deployments. Finally, applying Nimbus to real-world privacy-sensitive applications and conducting extensive performance evaluations in diverse network environments would demonstrate its effectiveness and practicality in realistic settings. Further investigation into the memory management of encrypted weights, focusing on optimization for resource-constrained environments is highly beneficial.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the concept of window encoding for matrix multiplication within the context of secure two-party computation using polynomials. The left side shows a simple matrix multiplication example. The right side demonstrates how this multiplication is represented using polynomials in the ring A16,25. The polynomial representation efficiently encodes the matrix multiplication but results in sparse polynomials with many zero coefficients. This sparsity is a key aspect that the paper aims to improve upon.

read the caption

Figure 1: An example of the window encoding of the matrix multiplication using N = 16 and l = 5.

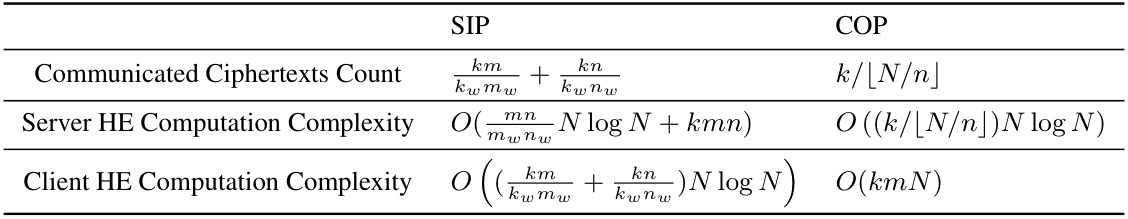

🔼 This figure illustrates the client-side outer product (COP) protocol for secure matrix multiplication. The left panel shows how the row-wise encoding works. The middle panel focuses on the computation of the first row of the output matrix, highlighting the use of scalar-polynomial multiplication. The right panel demonstrates how the output ciphertexts are packed using a right shift to reduce communication overhead.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of our matrix multiplication. Left: Functionality of the matrix multiplication using row-wise encoding. Middle: Computing the first row of the output through the scalar-poly product. Right: Packing two ciphertexts using a right shift for less number of output ciphertext.

🔼 This figure shows the distribution of input values for GELU and Softmax functions in the 4th encoder of the BERTbase model. The x-axis represents the input values, and the y-axis represents the number of times each input value occurred. The GELU distribution is roughly bell-shaped, while the Softmax distribution is heavily skewed towards lower values with a sharp increase near zero. This observation of non-uniform input distribution is exploited in the paper to improve the efficiency of non-linear layer approximations.

read the caption

Figure 4: The input distribution of non-linear functions. The y-axis indicates the occurrence counts.

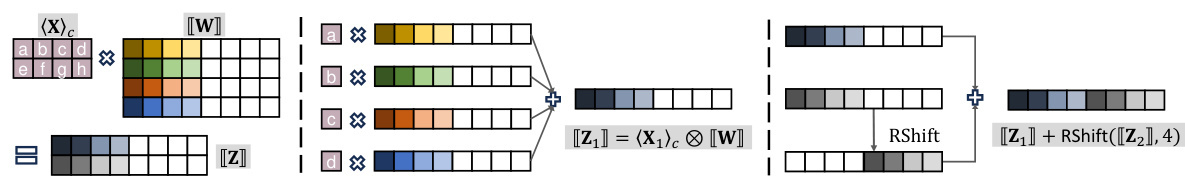

🔼 This figure shows the L2-norm of the output error between the original non-linear functions (exponential and GELU) and their polynomial approximations for different fixed-point precisions. The results are shown separately for two different ring sizes (Z232 and Z264) and for both Nimbus and BumbleBee methods. This visualization helps to understand the trade-off between accuracy and efficiency when choosing the fixed-point precision and ring size for secure computation of non-linear functions in transformer models.

read the caption

Figure 5: The L2-Norm of output error between oracle non-linear functions and approximations.

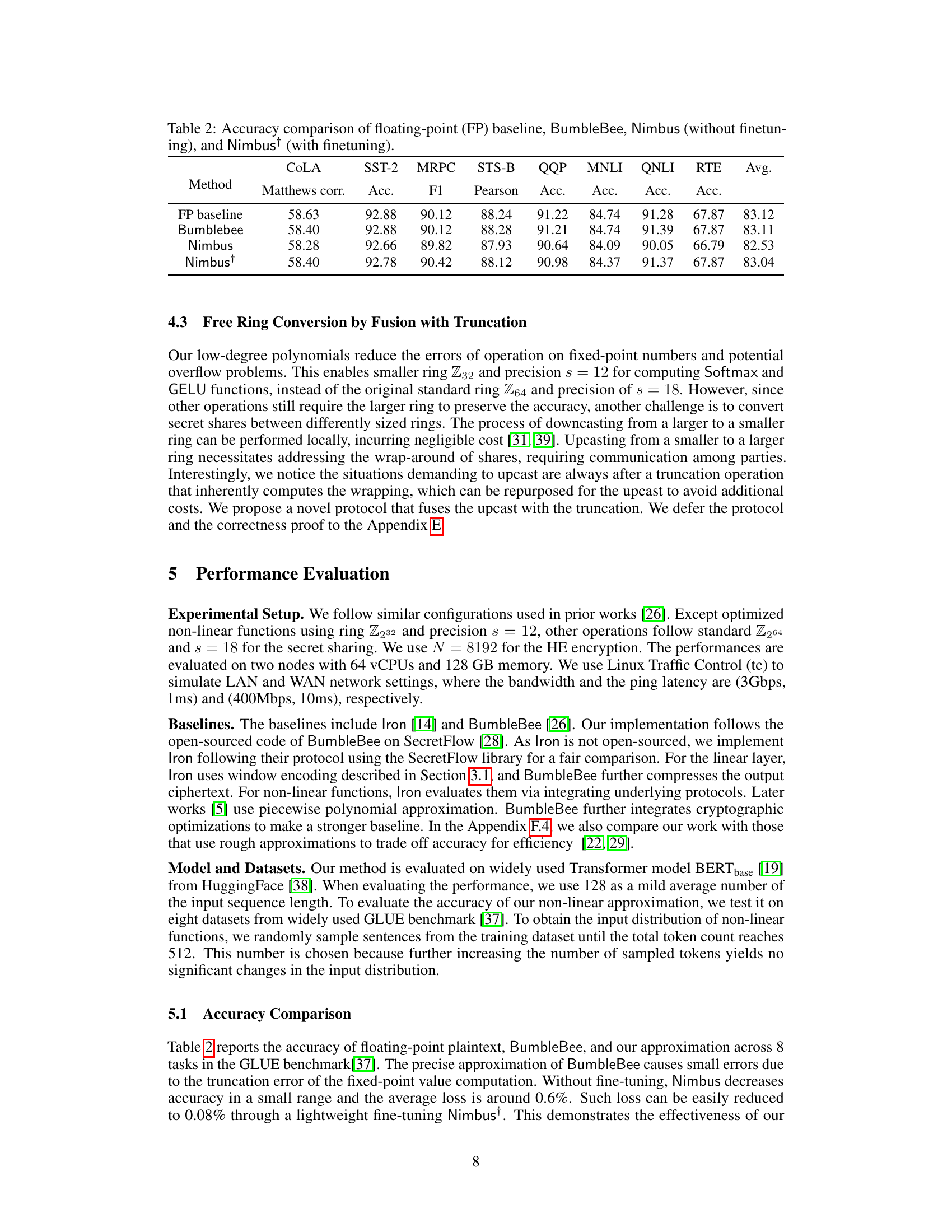

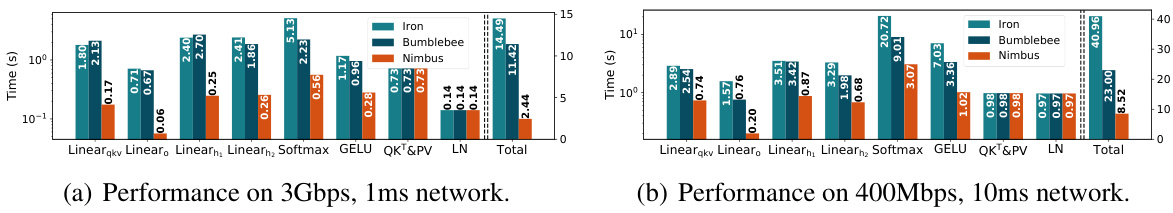

🔼 This figure shows a performance comparison of different secure two-party inference frameworks (Iron, BumbleBee, and Nimbus) on a Transformer block of the BERTbase model. It breaks down the total end-to-end latency into the time spent on different layers (Linear_qkv, Linear_o, Linear_h1, Linear_h2, Softmax, GELU, QKT&PV, and LayerNorm), under two different network settings (3Gbps, 1ms and 400Mbps, 10ms). The bar chart visually represents the latency for each component, allowing for a direct comparison of the efficiency of each framework across all layers and network conditions.

read the caption

Figure 6: The end-to-end latency of a Transformer block of BERTbase and its breakdown

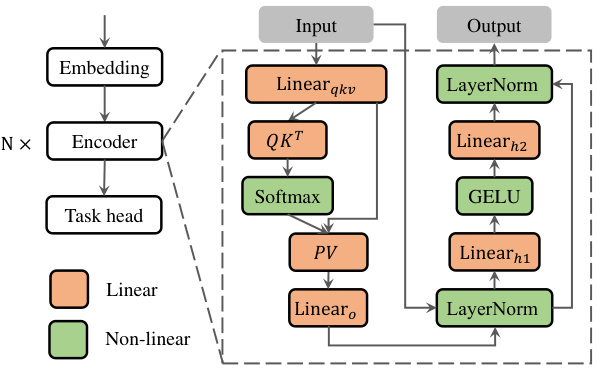

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of a Transformer-based model and provides a breakdown of the latency for each component during private inference. The model consists of an embedding layer, an encoder (with multiple repeated blocks), and a task head. Each encoder block includes a multi-head self-attention mechanism and a feed-forward network (FFN). The self-attention module uses three linear layers (Linear_qkv) to compute query, key, and value tensors, followed by a softmax function, a matrix multiplication of query and key (QKT), and another linear layer (Linear_o). The FFN module consists of two linear layers (Linear_h1 and Linear_h2), with GELU activation between them. Both the self-attention and FFN modules include layer normalization (LayerNorm). The latency is broken down into separate components of the various steps during the inference process, which is useful for performance analysis and optimization.

read the caption

Figure 7: The illustration of the Transformer-based model and the latency breakdown of its private evaluation.

🔼 This figure shows a detailed breakdown of the end-to-end latency for a single Transformer block in the BERTbase model. It compares the performance of three different secure two-party computation (2PC) protocols: Iron, BumbleBee, and Nimbus. The breakdown shows the latency contribution of each layer (Linearqkv, Linear, Linearn, Softmax, GELU, QKT&PV, LN) and the total latency. Two network settings are considered: a LAN (3Gbps, 1ms) and a WAN (400Mbps, 10ms) environment. The figure highlights the significant performance improvements achieved by Nimbus compared to the other two protocols, especially in the linear layers.

read the caption

Figure 6: The end-to-end latency of a Transformer block of BERTbase and its breakdown.

🔼 This figure displays a breakdown of the end-to-end latency for a single Transformer block within the BERTbase model. The breakdown shows the time spent on different components, including linear layers (Linearqkv, Linearo, Linearh1, Linearh2), non-linear layers (Softmax, GELU), attention and layer normalization (QKT&PV, LN), and the total time. The comparison is done under different network settings (3Gbps, 1ms and 400Mbps, 10ms). The results show the relative performance of three different methods (Iron, BumbleBee, and Nimbus).

read the caption

Figure 6: The end-to-end latency of a Transformer block of BERTbase and its breakdown.

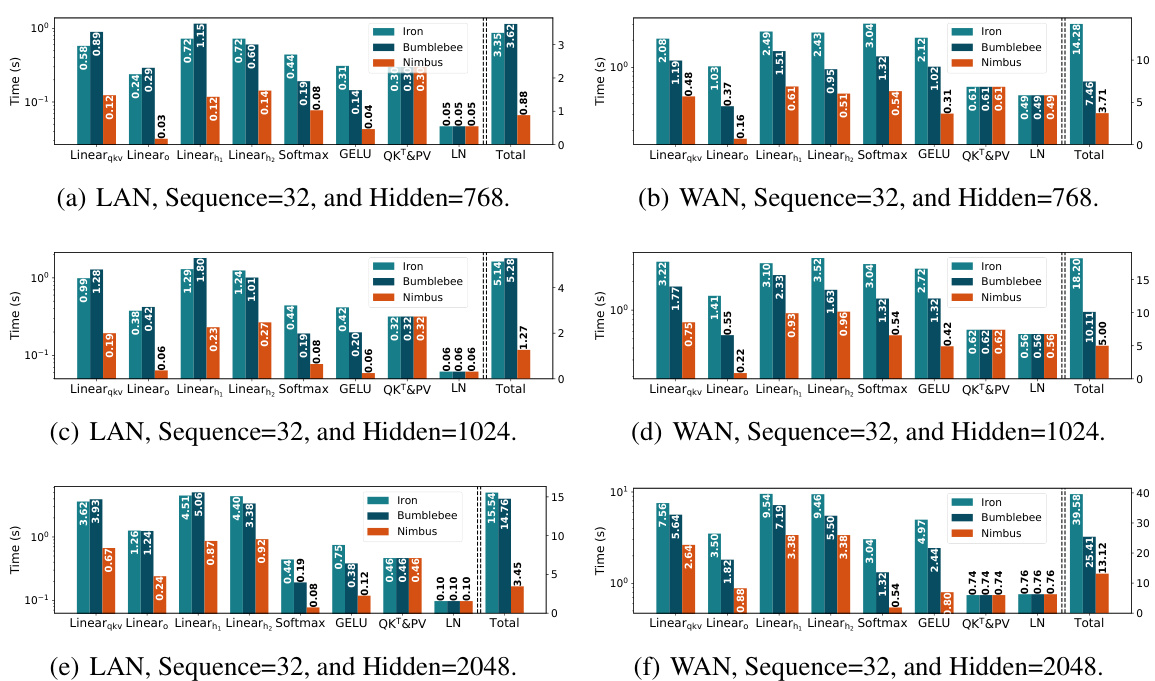

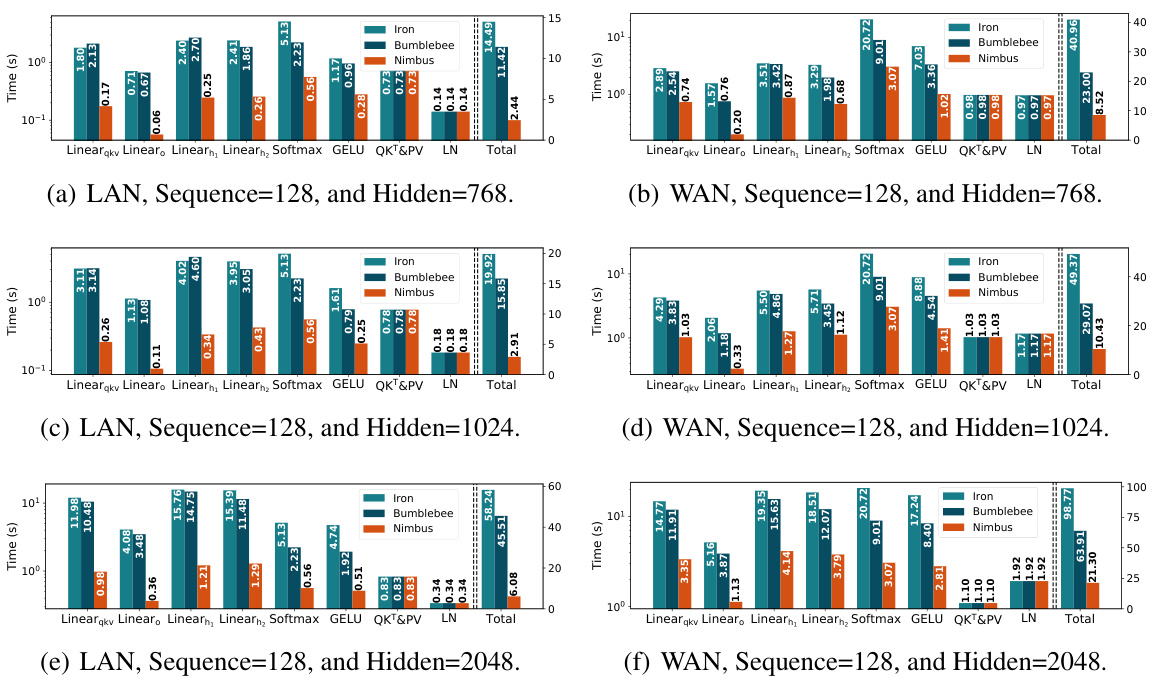

🔼 This figure shows the end-to-end latency breakdown for a single Transformer block within the BERTbase model under different network conditions (LAN and WAN). It compares the performance of three different secure two-party inference methods: Iron, BumbleBee, and Nimbus. The breakdown shows the time spent in different parts of the Transformer block, such as linear layers, non-linear layers (Softmax and GELU), attention mechanisms (QKT&PV), and layer normalization (LN). The results demonstrate the significant performance improvements achieved by the Nimbus framework.

read the caption

Figure 6: The end-to-end latency of a Transformer block of BERTbase and its breakdown.

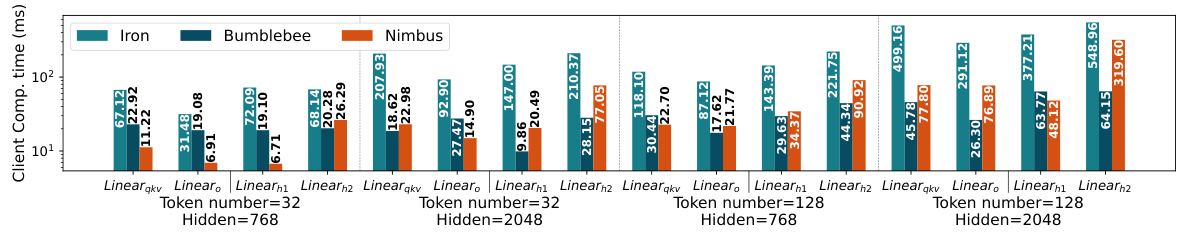

🔼 This figure compares the client computation time of Iron, BumbleBee, and Nimbus across various model sizes (hidden dimensions of 768, 1024, and 2048) and input sequence lengths (32 and 128). The results show that Nimbus significantly reduces the client-side computation time compared to Iron and BumbleBee, demonstrating its efficiency improvement.

read the caption

Figure 11: Under different sequence lengths and hidden sizes, we present comprehensive experiments of client computation time of different methods.

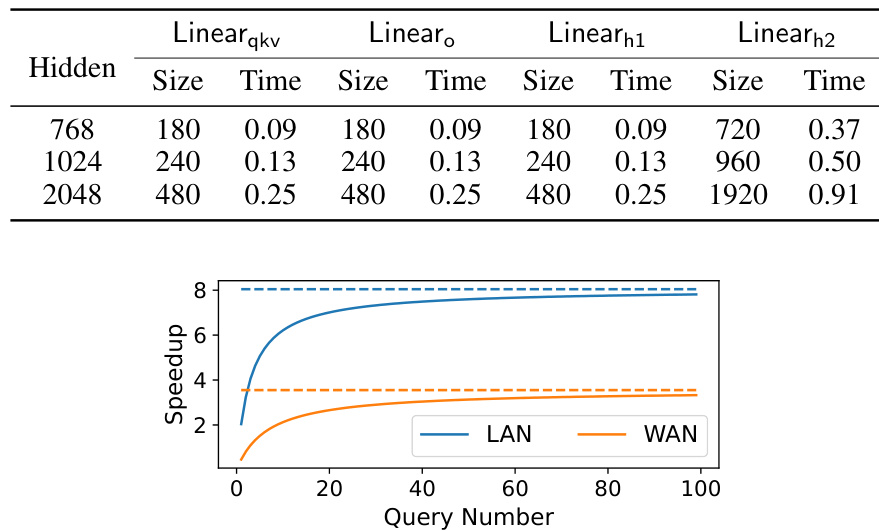

🔼 This figure shows the speedup achieved by Nimbus over BumbleBee when amortized setup time is considered. The x-axis represents the number of queries, and the y-axis represents the speedup. Two lines are plotted, one for LAN and one for WAN network settings. The figure demonstrates how, as the number of queries increases, the amortized overhead of Nimbus’s one-time setup communication becomes less significant, leading to a greater speedup compared to BumbleBee, especially in LAN environment. The point where the speedup crosses above 1 indicates when the amortized setup cost is outweighed by Nimbus’s computational efficiency.

read the caption

Figure 12: The execution+setup speedup over BumbleBee under different queries.

More on tables

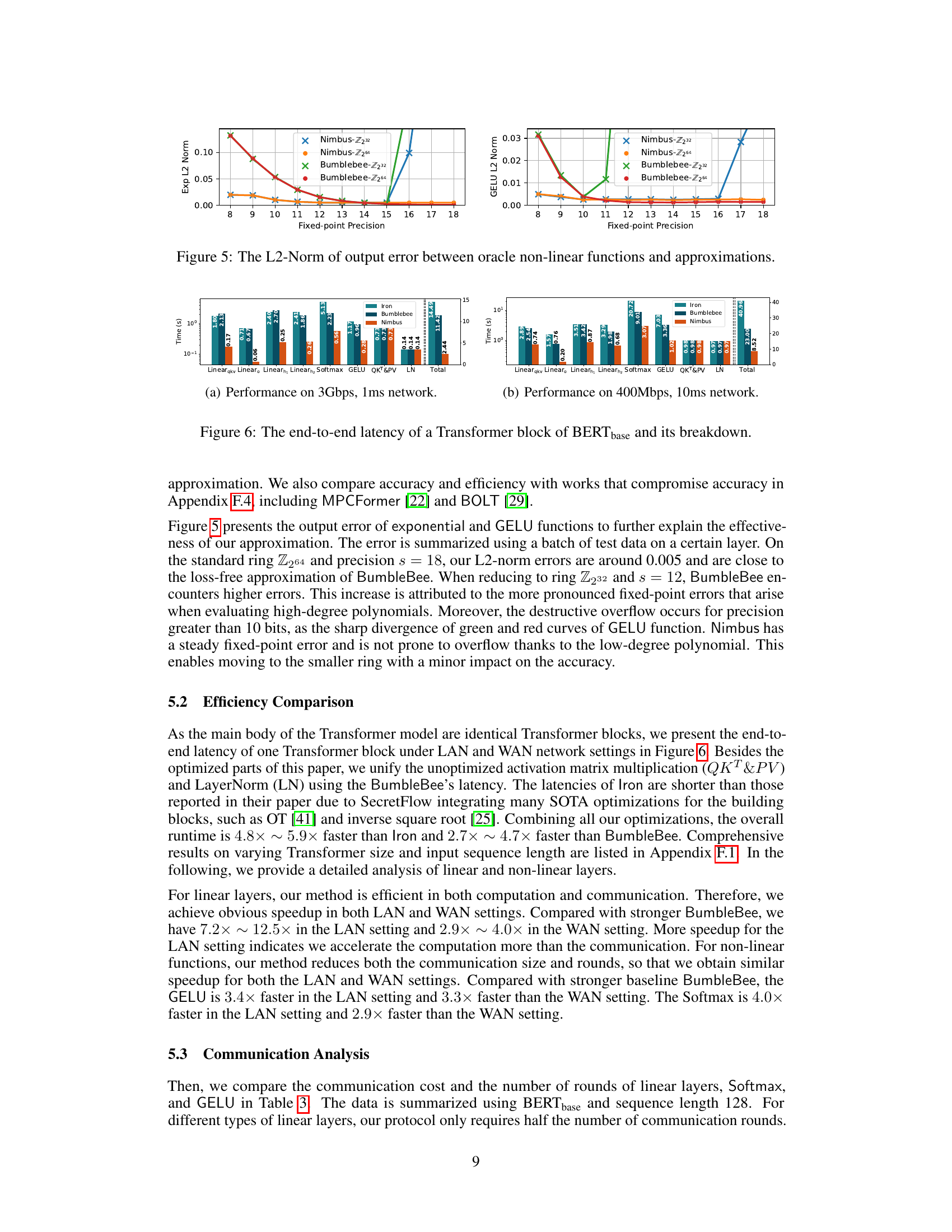

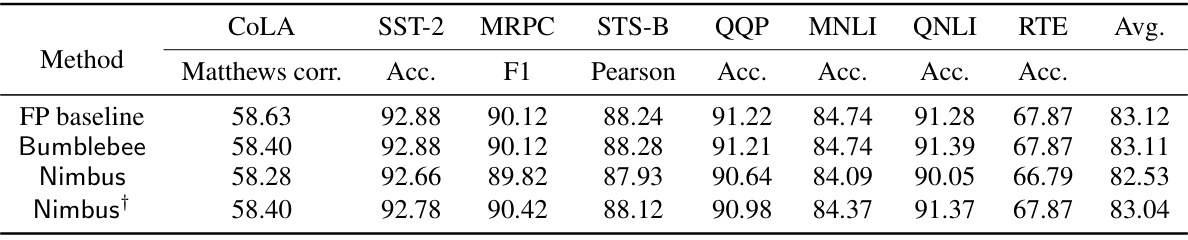

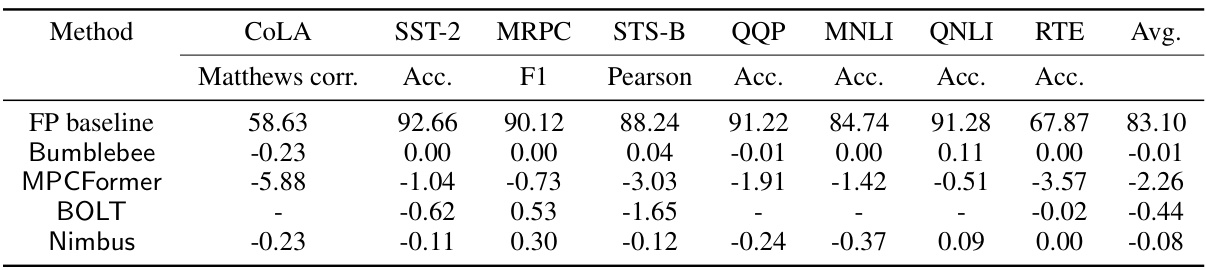

🔼 This table compares the accuracy of four different methods (Floating-point baseline, BumbleBee, Nimbus without finetuning, and Nimbus with finetuning) across eight different tasks (COLA, SST-2, MRPC, STS-B, QQP, MNLI, QNLI, RTE). Each task has multiple metrics (Matthews correlation, Accuracy, F1 score, Pearson correlation, and Accuracy), providing a comprehensive evaluation of the different approaches’ performance in terms of accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Accuracy comparison of floating-point (FP) baseline, BumbleBee, Nimbus (without finetuning), and Nimbus (with finetuning).

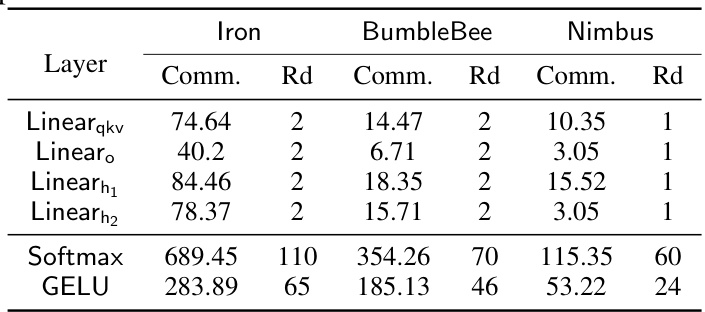

🔼 This table compares the communication costs (in megabytes) and the number of communication rounds required for different layers (Linearqkv, Linearo, Linearh1, Linearh2, Softmax, GELU) of a Transformer block, using three different secure computation methods: Iron, BumbleBee, and Nimbus. It highlights the communication efficiency improvements achieved by Nimbus compared to the other methods. The reduction in communication rounds is particularly notable for the Softmax and GELU layers, showing Nimbus’s enhanced efficiency in handling non-linear functions.

read the caption

Table 3: Communication cost (megabytes) and rounds comparison on one Transformer block.

🔼 This table compares the computational and communication complexities of the server-side inner product (SIP) protocol and the proposed client-side outer product (COP) protocol for matrix multiplication in the context of secure two-party computation. It details the number of communicated ciphertexts and the computational complexity (in Big O notation) for both the server and the client, considering various window sizes (kw, mw, nw) used to partition the input matrices. The COP protocol aims for efficiency improvements by reducing communication and computation.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the computation and communication for multiplication of two matrices with dimension k × m and m × n. kw, mw, nw are the window size corresponding to matrix dimensions.

🔼 This table compares the computational and communication complexities of the server-side inner product (SIP) protocol and the client-side outer product (COP) protocol for matrix multiplication. It shows the number of communicated ciphertexts and the computational complexity for both the server and the client. The COP protocol shows significant improvements in both communication and computation compared to the SIP protocol, particularly with the reduction of the number of communicated ciphertexts.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the computation and communication for multiplication of two matrices with dimension k × m and m × n. kw, mw, nw are the window size corresponding to matrix dimensions.

🔼 This table compares the accuracy of four different methods: a floating-point baseline (FP baseline), BumbleBee, Nimbus (without fine-tuning), and Nimbus (with fine-tuning). The accuracy is measured across eight different tasks from the GLUE benchmark (COLA, SST-2, MRPC, STS-B, QQP, MNLI, QNLI, RTE). Each task uses a different metric (Matthews correlation, accuracy, F1 score, Pearson correlation, accuracy, etc.), reflecting the specific nature of each task. The table shows the relative performance of each method compared to the FP baseline, highlighting the impact of different techniques on the model’s accuracy. The ‘Nimbus†’ row indicates that fine-tuning improved the accuracy of Nimbus.

read the caption

Table 2: Accuracy comparison of floating-point (FP) baseline, BumbleBee, Nimbus (without finetuning), and Nimbus (with finetuning).

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the efficiency of four different methods (BumbleBee, MPCFormer, BOLT, and Nimbus) for performing secure computation of Softmax and GLUE tasks. The comparison is done for two different network settings: LAN (3Gbps, 0.8ms) and WAN (200Mbps, 40ms). The values represent the execution times in seconds.

read the caption

Table 6: Efficiency comparison of BumbleBee, MPCFormer (Quad+2ReLU), BOLT, Nimbus

Full paper#