TL;DR#

Many large machine learning models are trained using distributed systems where multiple clients collaborate. However, some clients may be unreliable or malicious (‘Byzantine’), impacting model accuracy. Existing Byzantine-tolerant methods often assume full participation from all clients, which is impractical in real-world scenarios due to client unavailability or communication constraints. This limits their applicability to large-scale collaborative learning. The paper addresses this limitation by developing a novel algorithm that can effectively handle both Byzantine clients and partial client participation.

The proposed method, Byz-VR-MARINA-PP, cleverly utilizes gradient clipping within a variance-reduction framework to limit the impact of Byzantine clients. This approach is shown to work even when a majority of sampled clients are Byzantine, which represents a significant improvement over existing methods. Furthermore, the algorithm incorporates communication compression, enhancing its efficiency. Rigorous theoretical analysis demonstrates that Byz-VR-MARINA-PP achieves state-of-the-art convergence rates, making it both robust and efficient. The study also proposes a heuristic for adapting other Byzantine-robust methods to handle partial participation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in distributed machine learning because it directly addresses the critical issue of Byzantine fault tolerance in the context of partial client participation. This work provides the first method with provable guarantees of robustness and efficiency even when a majority of sampled clients are malicious or unreliable. This significantly advances the field’s ability to design robust and practical distributed learning systems for large-scale applications.

Visual Insights#

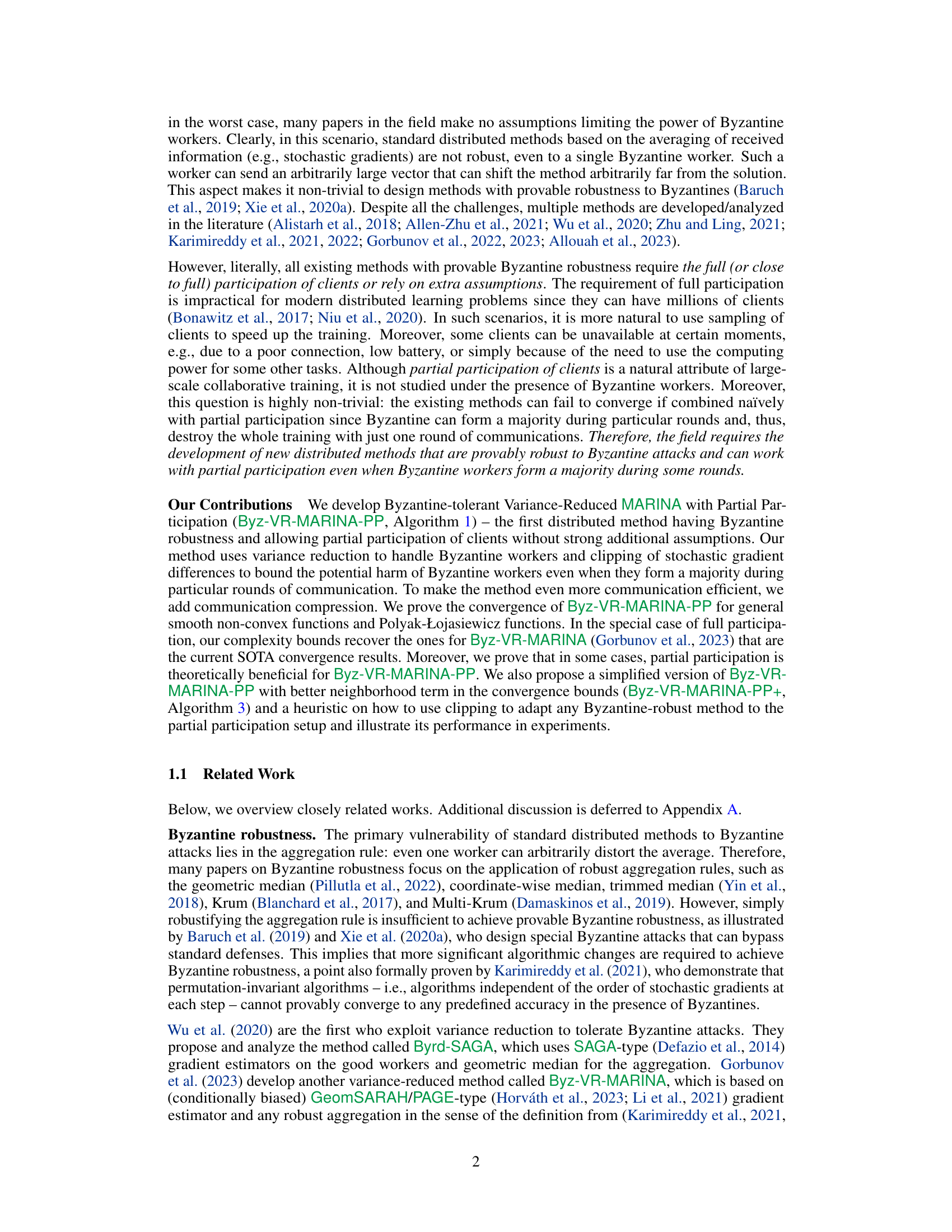

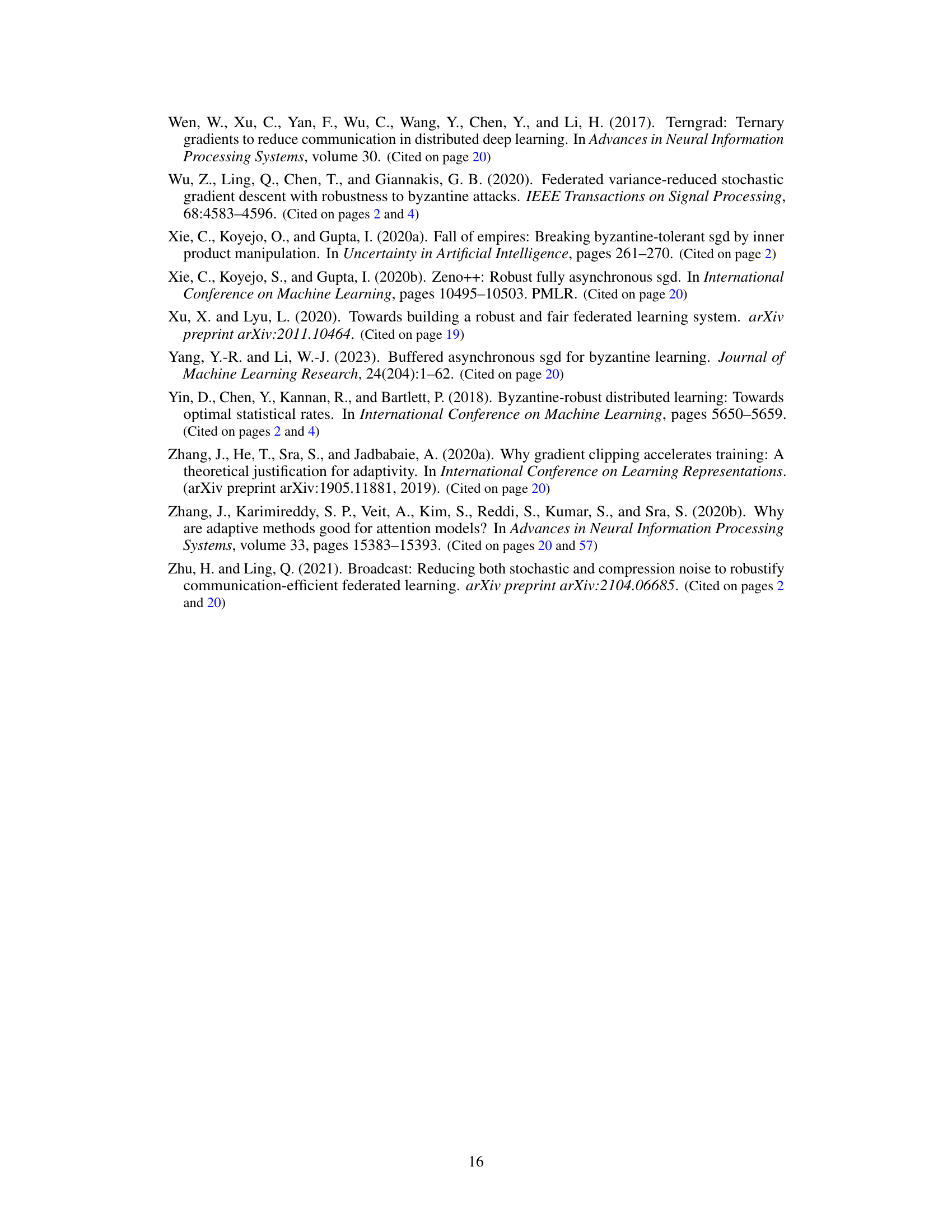

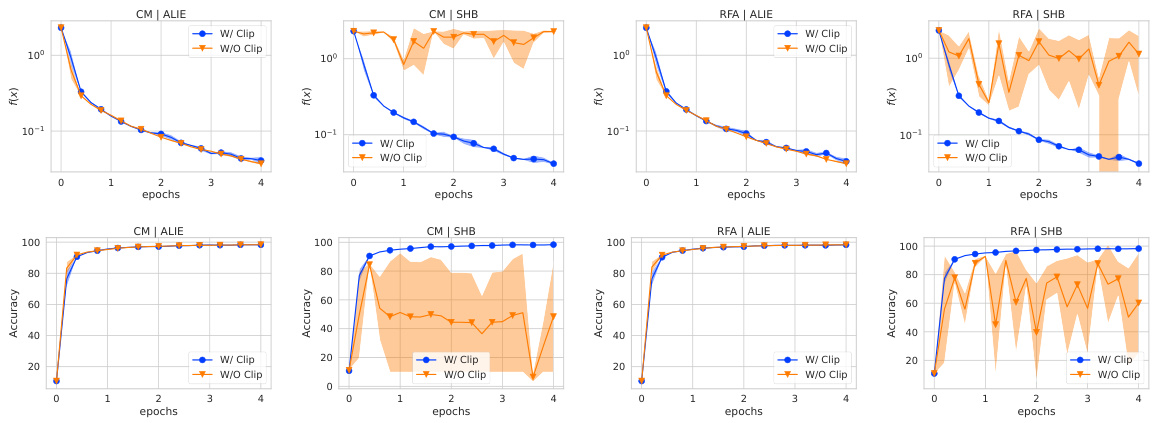

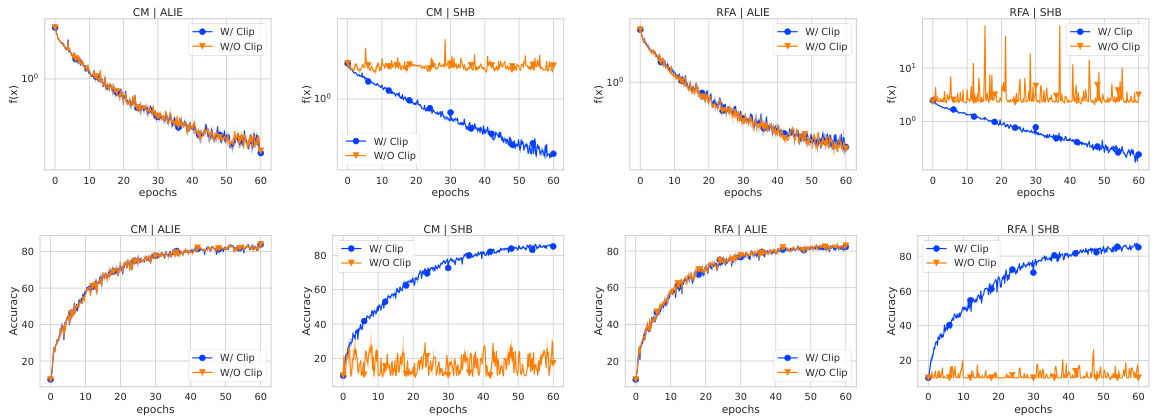

🔼 This figure shows three scenarios comparing the performance of Byz-VR-MARINA-PP in the presence of Byzantine workers. The left panel compares the convergence with and without clipping, highlighting the importance of clipping for robustness. The middle panel contrasts full participation with partial participation (20% of clients), showing that partial participation with clipping can be faster. The right panel demonstrates the effect of varying the clipping multiplier, indicating consistent performance across a range of values.

read the caption

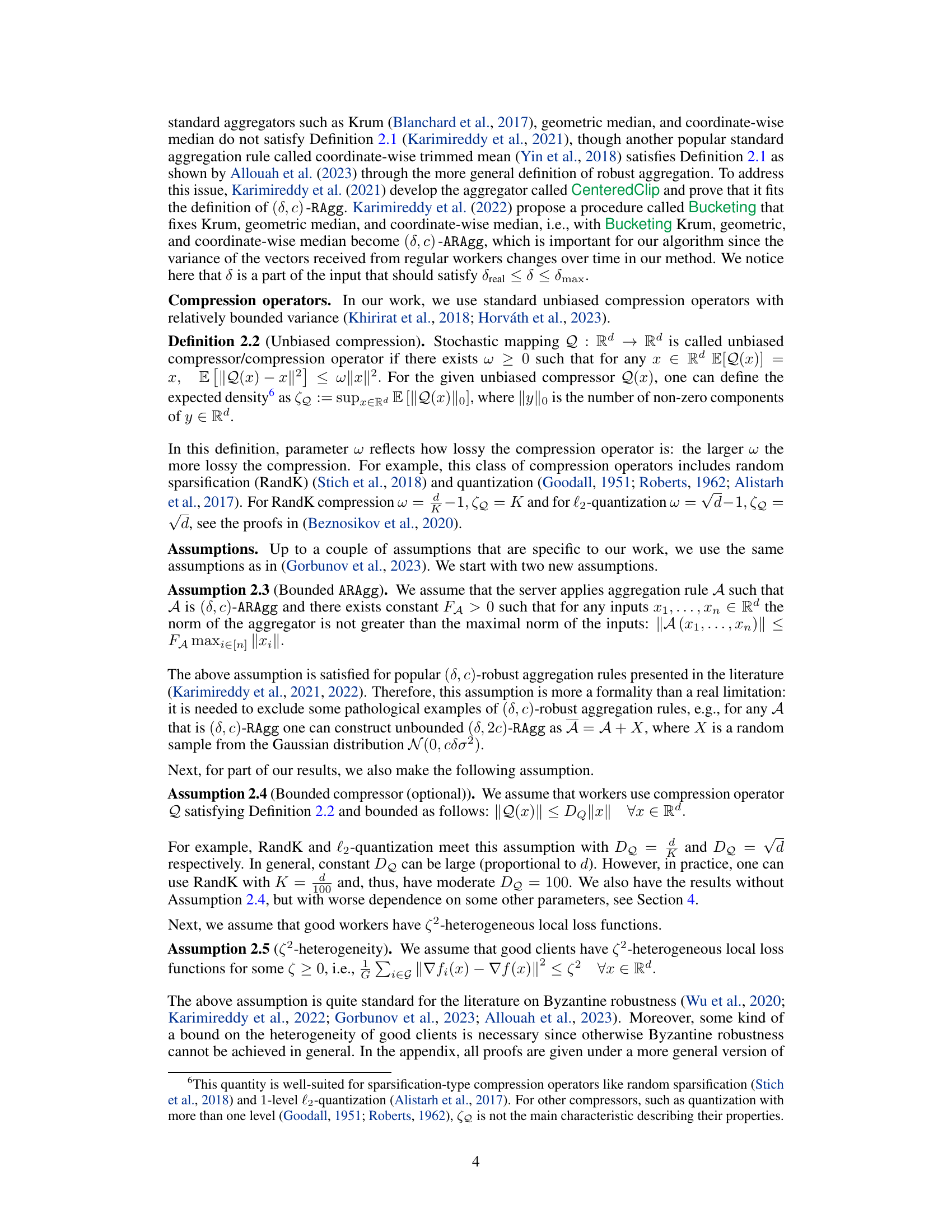

Figure 1: The optimality gap f(xk) − f(x*) for 3 different scenarios. We use coordinate-wise mean with bucketing equal to 2 as an aggregation and shift-back as an attack. We use the a9a dataset, where each worker accesses the full dataset with 15 good and 5 Byzantine workers. We do not use any compression. In each step, we sample 20% of clients uniformly at random to participate in the given round unless we specifically mention that we use full participation. Left: Linear convergence of Byz-VR-MARINA-PP with clipping versus non-convergence without clipping. Middle: Full versus partial participation, showing faster convergence with clipping. Right: Clipping multiplier λ sensitivity, demonstrating consistent linear convergence across varying λ values.

🔼 This algorithm describes the process of robust aggregation by applying a chosen aggregation rule to the averages of vectors. These averages are calculated over buckets created by sampling a random permutation of the input vectors, which improves the robustness of the aggregation.

read the caption

Algorithm 2 Bucketing Algorithm (Karimireddy et al., 2022)

In-depth insights#

Byzantine Tolerance#

Byzantine fault tolerance in distributed systems is a critical concern, especially in machine learning where unreliable or malicious nodes can compromise model accuracy and integrity. Robust aggregation mechanisms are key to mitigating Byzantine attacks, where faulty nodes send incorrect or manipulated data. These mechanisms aim to identify and neutralize the influence of these outliers, ensuring that the model training process converges to a reliable solution. Techniques include geometric median, trimmed mean, and Krum, each offering different tradeoffs in terms of computational cost and robustness to varying levels of Byzantine participation. The effectiveness of these methods is often evaluated theoretically, with the goal of proving convergence under specific conditions, such as bounded noise and a limited fraction of Byzantine workers. Provable Byzantine robustness is a significant achievement, particularly in dynamic environments where the set of participants may change over time. Gradient clipping also plays an important role in Byzantine-tolerant algorithms, helping to control the impact of potentially harmful gradient updates from faulty nodes.

Clipping Mechanisms#

Clipping mechanisms, in the context of robust gradient aggregation for distributed learning, are crucial for mitigating the influence of Byzantine workers. These malicious or faulty nodes can inject arbitrary gradient updates, potentially derailing the training process. By clipping, gradients are constrained within a pre-defined bound, limiting the impact of outliers. The choice of clipping threshold is critical, as setting it too low can hinder convergence while setting it too high may not sufficiently protect against Byzantine attacks. Effective clipping strategies often involve dynamic adjustments of the threshold based on the observed variance or norm of the gradients, balancing robustness and efficiency. Research on optimal clipping techniques is ongoing, with a focus on developing methods that adapt to varying levels of Byzantine influence and data heterogeneity, ensuring both convergence guarantees and resilience to adversarial behaviour in the training process. Provable convergence results under various clipping strategies and Byzantine attack models are important goals in this active area of research.

Partial Participation#

The concept of ‘Partial Participation’ in distributed machine learning tackles the realistic scenario where not all nodes or clients are available for every training round. This is a significant departure from the traditional assumption of full participation, which often simplifies analysis but lacks real-world applicability. Partial participation is crucial for scalability, handling unreliable network connections, and improving efficiency by reducing communication overhead. However, it introduces new challenges, particularly in the presence of Byzantine nodes. Byzantine fault tolerance techniques need to be carefully adapted to work under partial participation to avoid situations where malicious nodes could dominate the aggregation process. Therefore, algorithms designed for partial participation must be provably robust against such attacks, even when a majority of sampled nodes are malicious. Client sampling strategies play a key role, carefully selecting representative nodes from the available subset to ensure robustness and convergence. The theoretical analysis of algorithms operating under partial participation becomes more complex because of the stochasticity arising from node availability and sampling. Convergence results often need to be carefully tailored to reflect these challenges, potentially resulting in different convergence rates than those achieved under full participation.

Convergence Rates#

Analyzing convergence rates in distributed machine learning is crucial for understanding algorithm efficiency and scalability. The rates reveal how quickly an algorithm approaches a solution, considering factors like the number of iterations, data size, and network communication. Faster rates are desirable for practical applications. Theoretical analysis provides convergence bounds, often expressed as Big-O notation, indicating the algorithm’s performance under specific assumptions. Provable convergence rates are critical for establishing algorithm reliability and guaranteeing solution quality. However, real-world conditions rarely perfectly match theoretical assumptions, so empirical evaluation is necessary to validate theoretical findings. Factors such as data heterogeneity, communication delays, and Byzantine failures impact convergence. Therefore, a robust analysis incorporates such factors to provide more realistic rates and demonstrate an algorithm’s resilience. Furthermore, optimizing convergence rates often involves trade-offs between computation, communication, and memory efficiency. Thus, a careful evaluation of these trade-offs is essential for selecting the best algorithm for a given application.

Future Research#

The paper’s conclusion points towards several promising avenues for future research. Improving the convergence bounds is a key area, specifically focusing on reducing the dependence on factors like the compression ratio (w), the number of data samples (m), and the client sample size (C). Another important direction involves rigorously proving the efficacy of the proposed clipping heuristic for a broader range of Byzantine-robust methods, moving beyond the specific algorithm presented. Finally, exploring more complex participation patterns such as non-uniform sampling or allowing for arbitrary client participation would significantly enhance the practical applicability and robustness of the proposed methods. These avenues would expand the applicability to scenarios with dynamic client availability and differing data distributions, adding depth to both theoretical understanding and real-world implementation.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure compares three scenarios to illustrate the performance of Byz-VR-MARINA-PP. The left panel shows the linear convergence with clipping against non-convergence without clipping in a full participation setting. The middle panel contrasts full participation with partial participation, highlighting faster convergence when clipping is employed. The right panel demonstrates the consistent linear convergence across varying clipping multipliers (λ), showing robustness to parameter tuning.

read the caption

Figure 1: The optimality gap f(xk) − f(x*) for 3 different scenarios. We use coordinate-wise mean with bucketing equal to 2 as an aggregation and shift-back as an attack. We use the a9a dataset, where each worker accesses the full dataset with 15 good and 5 Byzantine workers. We do not use any compression. In each step, we sample 20% of clients uniformly at random to participate in the given round unless we specifically mention that we use full participation. Left: Linear convergence of Byz-VR-MARINA-PP with clipping versus non-convergence without clipping. Middle: Full versus partial participation, showing faster convergence with clipping. Right: Clipping multiplier λ sensitivity, demonstrating consistent linear convergence across varying λ values.

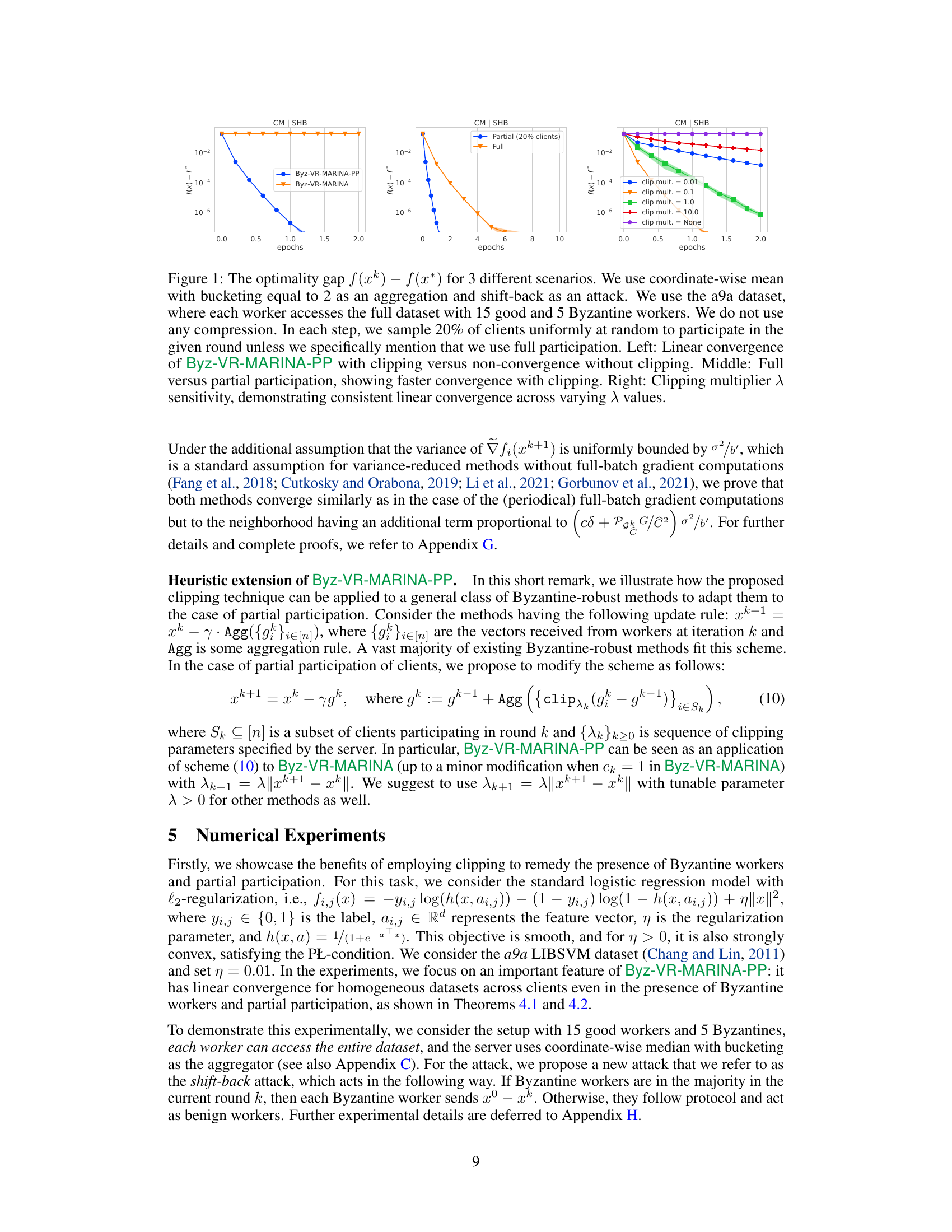

🔼 This figure demonstrates the effectiveness of the proposed Byz-VR-MARINA-PP algorithm under different scenarios. It shows three sets of experiments comparing the optimality gap (difference between current and optimal objective function values) over epochs of training. The left panel compares the algorithm’s performance with and without clipping, showcasing linear convergence with clipping and failure to converge without. The middle panel shows that partial participation leads to faster convergence compared to full participation when using clipping. The right panel displays the algorithm’s robustness to different clipping multiplier values, demonstrating consistent linear convergence.

read the caption

Figure 1: The optimality gap f(xk) − f(x*) for 3 different scenarios. We use coordinate-wise mean with bucketing equal to 2 as an aggregation and shift-back as an attack. We use the a9a dataset, where each worker accesses the full dataset with 15 good and 5 Byzantine workers. We do not use any compression. In each step, we sample 20% of clients uniformly at random to participate in the given round unless we specifically mention that we use full participation. Left: Linear convergence of Byz-VR-MARINA-PP with clipping versus non-convergence without clipping. Middle: Full versus partial participation, showing faster convergence with clipping. Right: Clipping multiplier λ sensitivity, demonstrating consistent linear convergence across varying λ values.

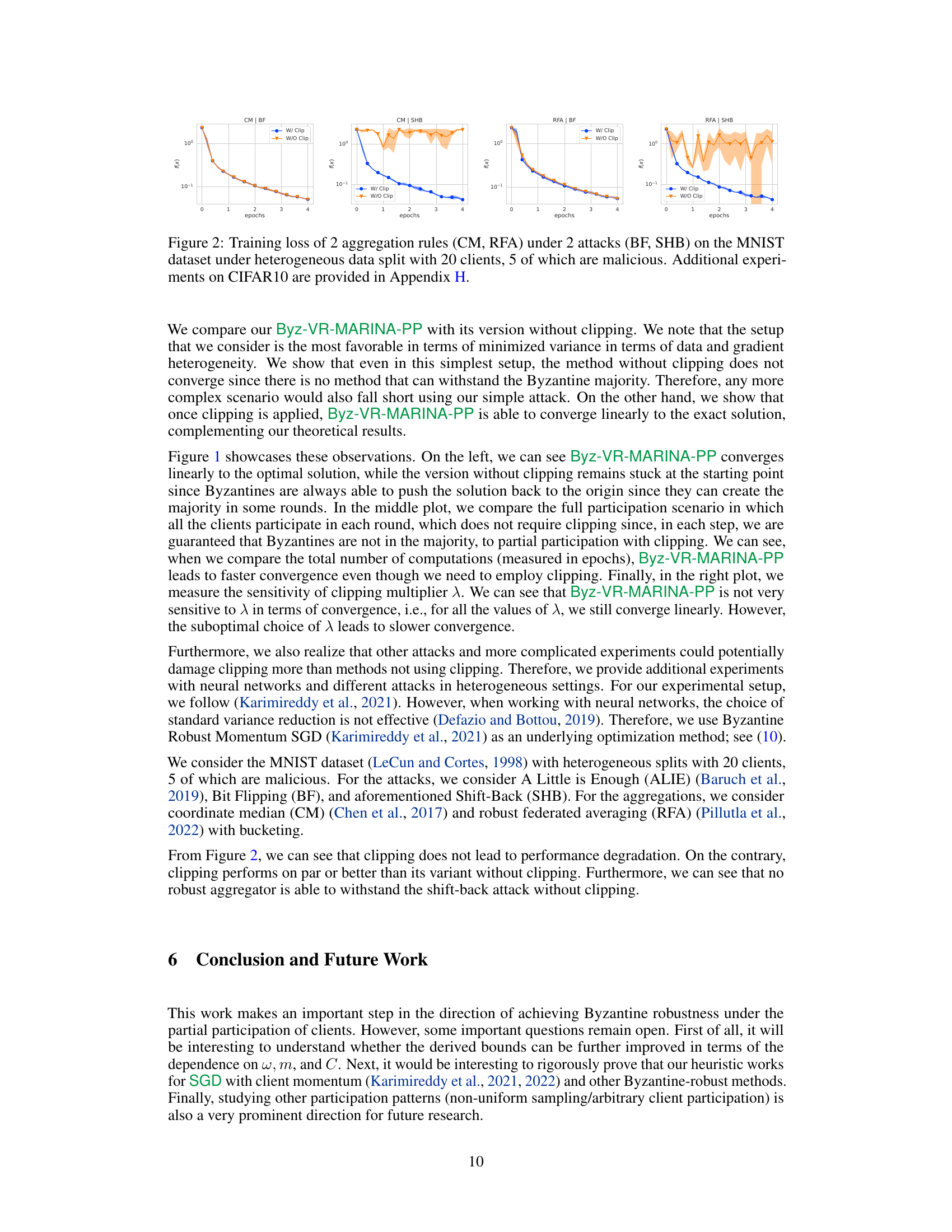

🔼 This figure shows the optimality gap, which is the difference between the current function value and the optimal function value, in three different experimental scenarios. The first scenario compares the linear convergence rate of the Byz-VR-MARINA-PP algorithm with and without gradient clipping, showing the critical role of clipping for convergence when facing Byzantine workers. The second scenario contrasts the convergence speed under full participation versus partial participation, highlighting the benefit of partial participation when combined with clipping. The third scenario examines the sensitivity of convergence to the clipping multiplier (λ), demonstrating consistent linear convergence across a range of λ values.

read the caption

Figure 1: The optimality gap f(xk) − f(x*) for 3 different scenarios. We use coordinate-wise mean with bucketing equal to 2 as an aggregation and shift-back as an attack. We use the a9a dataset, where each worker accesses the full dataset with 15 good and 5 Byzantine workers. We do not use any compression. In each step, we sample 20% of clients uniformly at random to participate in the given round unless we specifically mention that we use full participation. Left: Linear convergence of Byz-VR-MARINA-PP with clipping versus non-convergence without clipping. Middle: Full versus partial participation, showing faster convergence with clipping. Right: Clipping multiplier λ sensitivity, demonstrating consistent linear convergence across varying λ values.

Full paper#