↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Traditional predict-then-optimize methods struggle with the discontinuity of decision losses, hindering the use of gradient-based optimization. Existing surrogates often have approximation errors that don’t vanish, leading to suboptimal policies, particularly in real-world scenarios where models are often misspecified. This paper tackles these issues.

This research proposes Perturbation Gradient (PG) losses. PG losses connect the expected downstream decision loss to the directional derivative of a plug-in objective. This allows for approximation via zeroth-order gradient techniques, resulting in Lipschitz continuous surrogates that can be optimized efficiently. Crucially, the approximation error of PG losses vanishes as the number of samples increases, guaranteeing asymptotically optimal policies even when the underlying model is incorrect. Experiments show PG losses outperform existing methods, particularly under model misspecification.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in decision-making under uncertainty because it introduces a novel family of surrogate losses that overcome the limitations of existing methods, especially in misspecified settings. This significantly improves the accuracy and efficiency of predict-then-optimize approaches, opening up new avenues for research and applications in various fields.

Visual Insights#

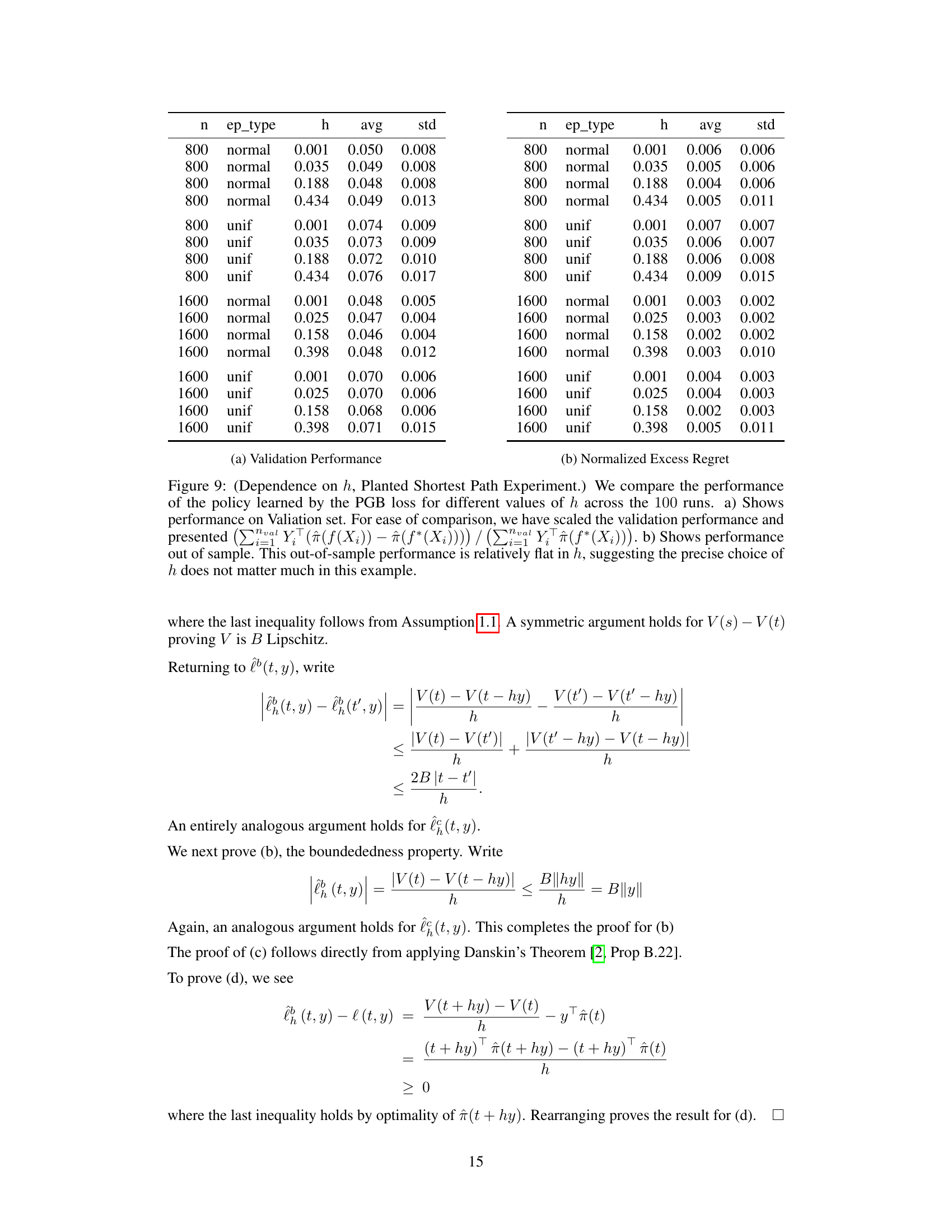

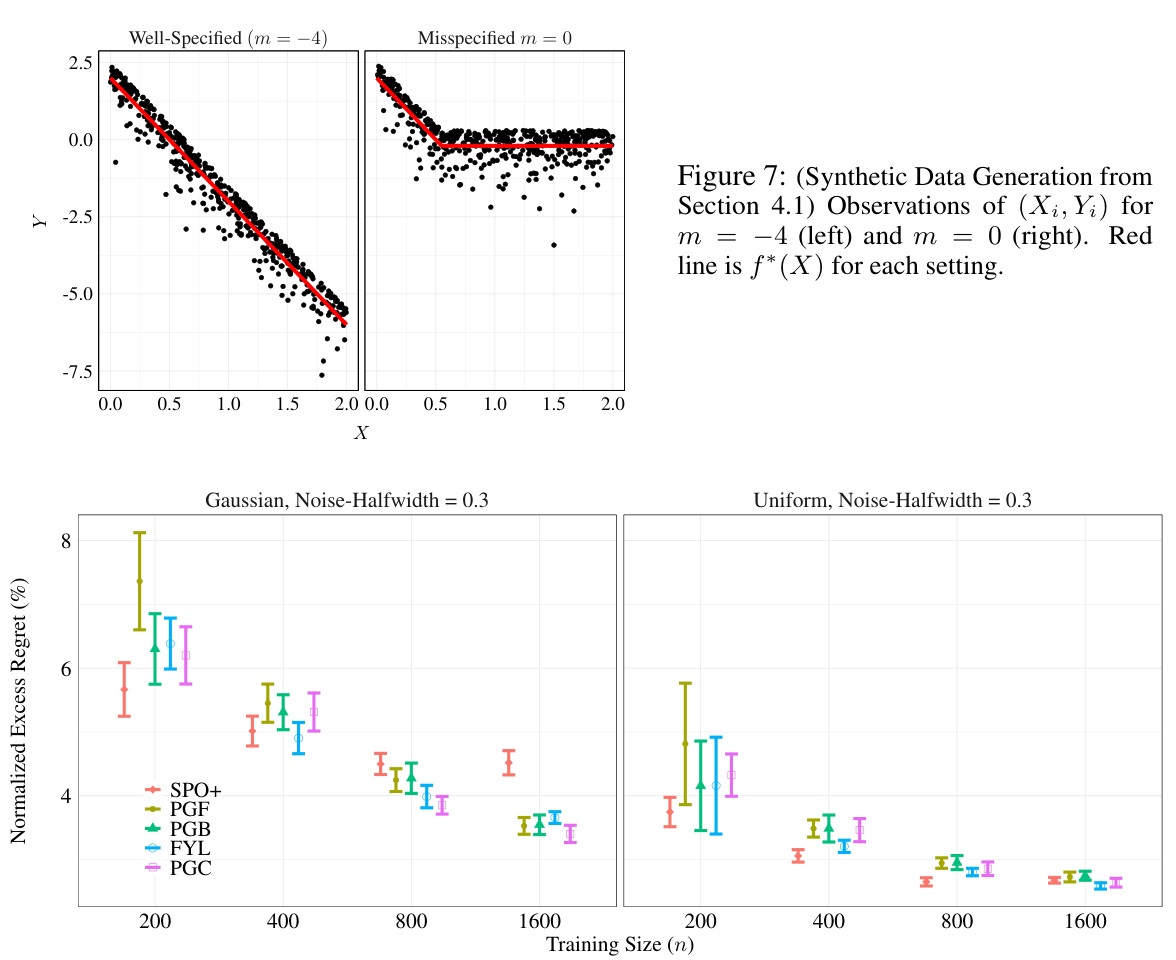

The figure shows the convergence of different methods for minimizing excess regret under misspecification. The x-axis represents the training size (n), and the y-axis represents the normalized excess regret. The proposed Perturbation Gradient (PGB) loss significantly outperforms other methods (DBB, ETO, FYL, SPO+) by exhibiting vanishing excess regret as the training size increases. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals based on 100 trials. The experiment uses a misspecified setting where a=1 and m=0, as described in Section 4.1 of the paper.

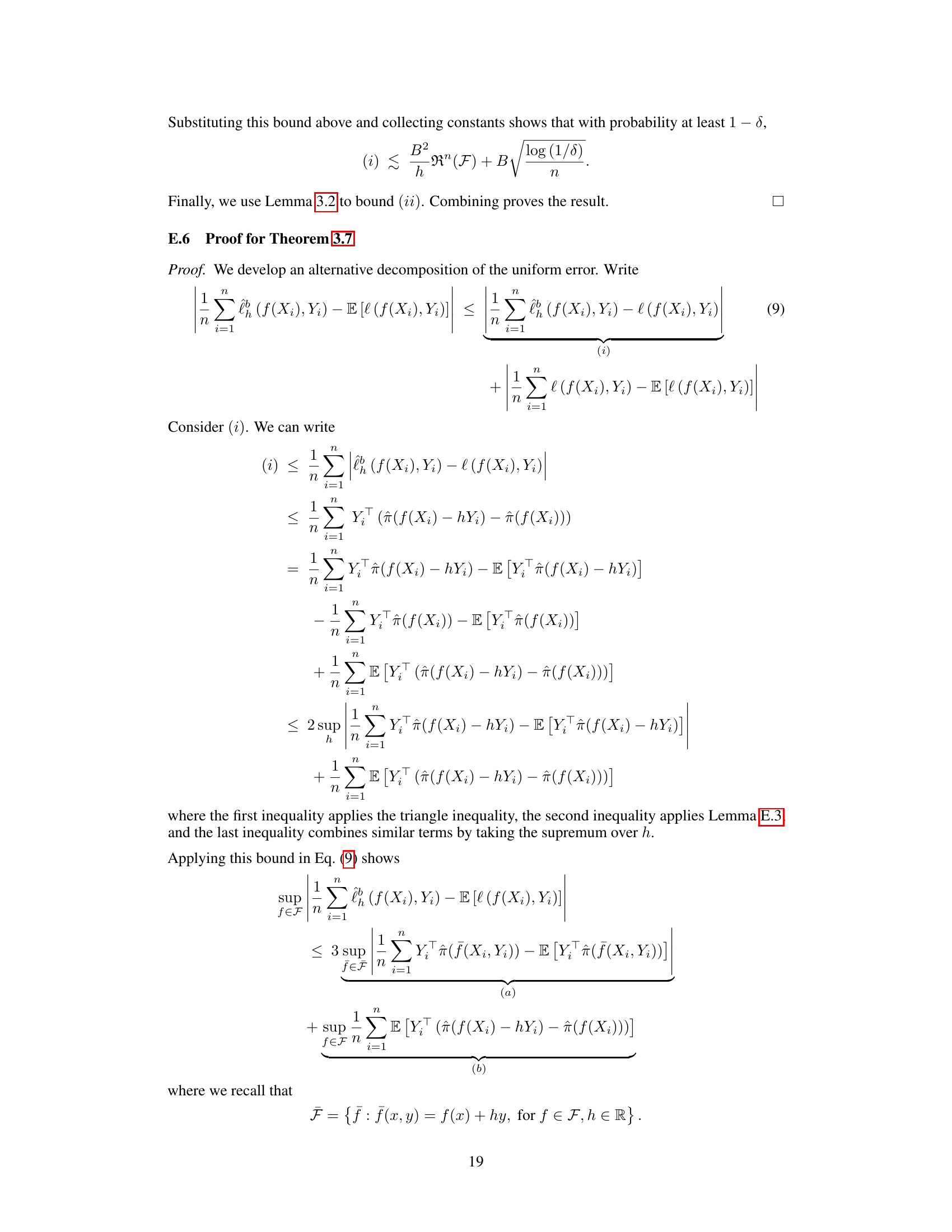

This table presents the results of an experiment that studies the effect of the hyperparameter h on the performance of the PGB loss in a planted shortest path problem. The experiment is performed 100 times for each setting of the hyperparameter. The table shows the average and standard deviation of the validation performance and the out-of-sample performance for different values of h and sample sizes. The out-of-sample performance is relatively insensitive to h, suggesting that the choice of h is not critical in this problem.

In-depth insights#

Directional Gradients#

The concept of “Directional Gradients” in the context of decision-focused learning suggests a novel approach to optimizing prediction models. Instead of relying solely on traditional gradient-based methods which might struggle with the inherent discontinuity of decision losses, this method leverages directional derivatives. This allows for the approximation of the expected downstream loss through zeroth-order gradient techniques, resulting in smoother, more easily optimized surrogate loss functions. The authors highlight the advantages of using this method in misspecified settings, where the true underlying model is unknown. Crucially, the approximation error of their proposed method is shown to vanish as the number of data samples grows, guaranteeing asymptotic convergence to a best-in-class policy even in these challenging scenarios. This contrasts with existing methods that often make strong assumptions about the true model, limiting their performance when these assumptions are violated. The use of directional gradients thus offers a robust and theoretically sound approach to learning effective decision-making policies.

Surrogate Losses#

The concept of “Surrogate Losses” in the context of decision-focused learning is crucial because the true downstream decision loss is often non-convex, discontinuous, and computationally expensive to optimize directly. Surrogate losses offer differentiable approximations that facilitate the use of efficient gradient-based optimization methods. The effectiveness of a surrogate loss hinges on its ability to closely approximate the true loss while maintaining computational tractability. The paper introduces a novel family of surrogate losses called Perturbation Gradient (PG) losses designed to address the limitations of existing methods. A key advantage of PG losses is that their approximation error vanishes asymptotically, ensuring that optimizing the surrogate converges to the optimal policy. The theoretical guarantees, especially in misspecified settings, are a significant contribution. The Lipschitz continuity and difference-of-concave properties of PG losses enable the use of off-the-shelf optimization algorithms, making the approach practical. Empirical evaluations demonstrate that PG losses significantly outperform existing methods, particularly when the underlying model is misspecified. The choice of zeroth-order gradient approximation (e.g., backward vs. central differencing) is explored as an additional point that impacts performance.

Regret Bounds#

Regret bounds, in the context of decision-focused learning, quantify the performance gap between a learned policy and an optimal policy. Tight bounds are crucial as they provide theoretical guarantees on the algorithm’s effectiveness. The paper likely explores different regret bounds under various assumptions, such as well-specified vs. misspecified settings. Well-specified settings, where the true data-generating process is within the model’s hypothesis class, often lead to tighter bounds and faster convergence rates. However, misspecified settings are more realistic and challenging, with the paper likely demonstrating that the proposed method still achieves asymptotically optimal performance even with misspecification. The type of regret bound, such as high-probability bounds or expected regret, also influences the analysis. High-probability bounds provide guarantees that hold with a certain probability, while expected regret bounds provide an average-case guarantee. The analysis likely investigates the dependence of the regret bound on various factors, like sample size (n), the complexity of the hypothesis class, and potentially the problem’s structure. The results will show how the proposed method’s regret diminishes as these parameters change, showcasing its effectiveness.

Misspec. Robustness#

The concept of ‘Misspec. Robustness’ in the context of decision-focused learning highlights a critical challenge: developing methods that perform well even when the underlying predictive model is inaccurate. This is crucial because real-world problems rarely conform perfectly to assumed models. The paper’s focus on this is commendable as it acknowledges a significant limitation in many existing approaches. Existing methods often assume a well-specified setting where the predictive model accurately reflects reality. However, the misspecified setting is more realistic and thus achieving robustness in this scenario is essential for practical applications. A key contribution is demonstrating that the proposed Perturbation Gradient (PG) losses are superior in this context because their approximation error vanishes as data increases, guaranteeing asymptotic optimality. This is significant because it directly addresses the core issue of misspecification, demonstrating the efficacy of PG losses even when other decision-aware methods fail.

Future: Non-convex#

The heading ‘Future: Non-convex’ suggests an exploration of non-convex optimization within a research area, likely machine learning or a related field. This is significant because many real-world problems are inherently non-convex, unlike the simplified convex formulations often used for theoretical analysis. A focus on non-convexity implies the researchers are tackling more realistic, complex scenarios. The discussion might delve into the challenges of finding global optima in non-convex landscapes, and it could explore advanced optimization techniques like simulated annealing, genetic algorithms, or specialized gradient descent methods. Furthermore, the section may address the trade-offs between computational cost and solution quality inherent in non-convex optimization. Finally, a ‘Future: Non-convex’ section hints at the ongoing and important research needed to develop more effective algorithms for solving these challenging problems. This is likely to include exploring the application of novel theoretical tools and empirical strategies.

More visual insights#

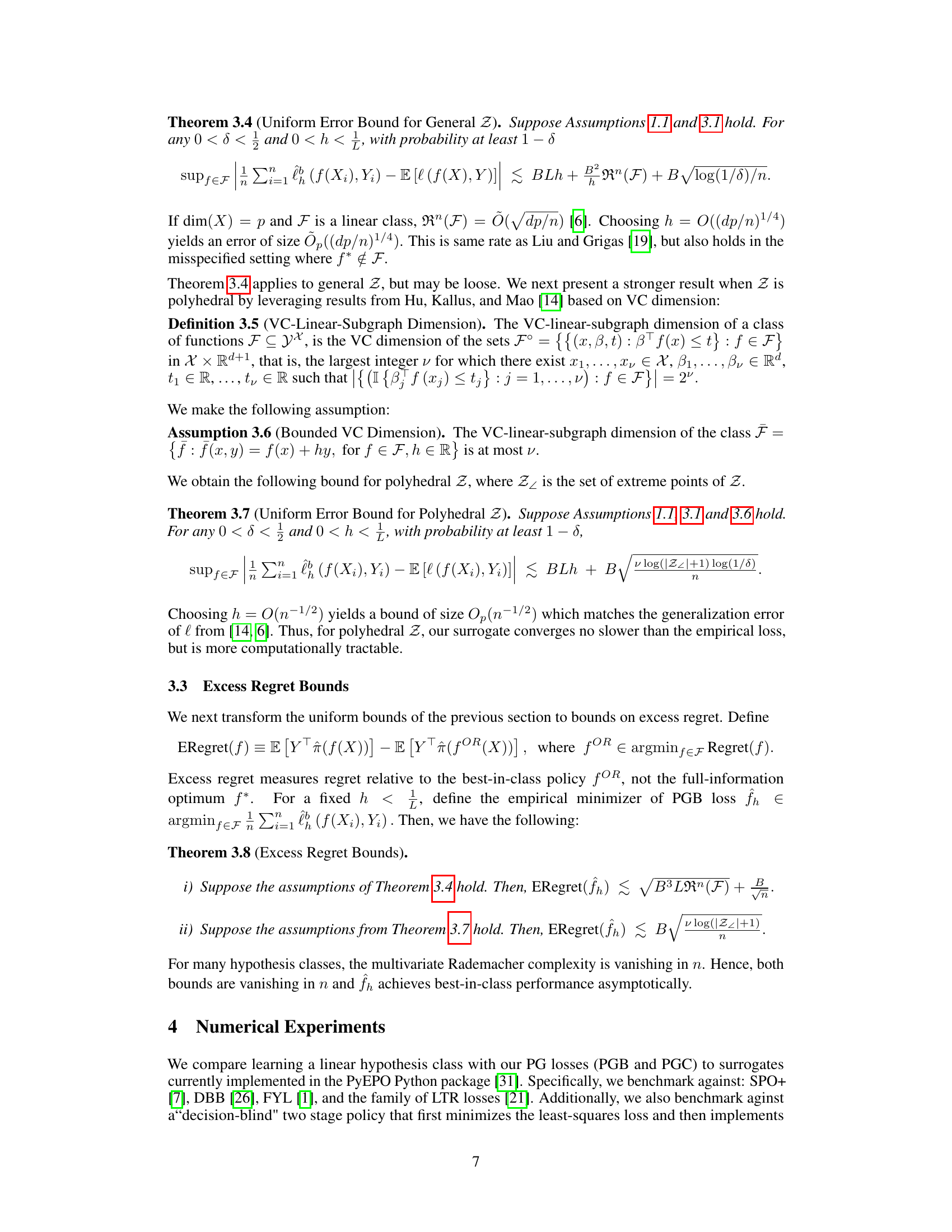

More on figures

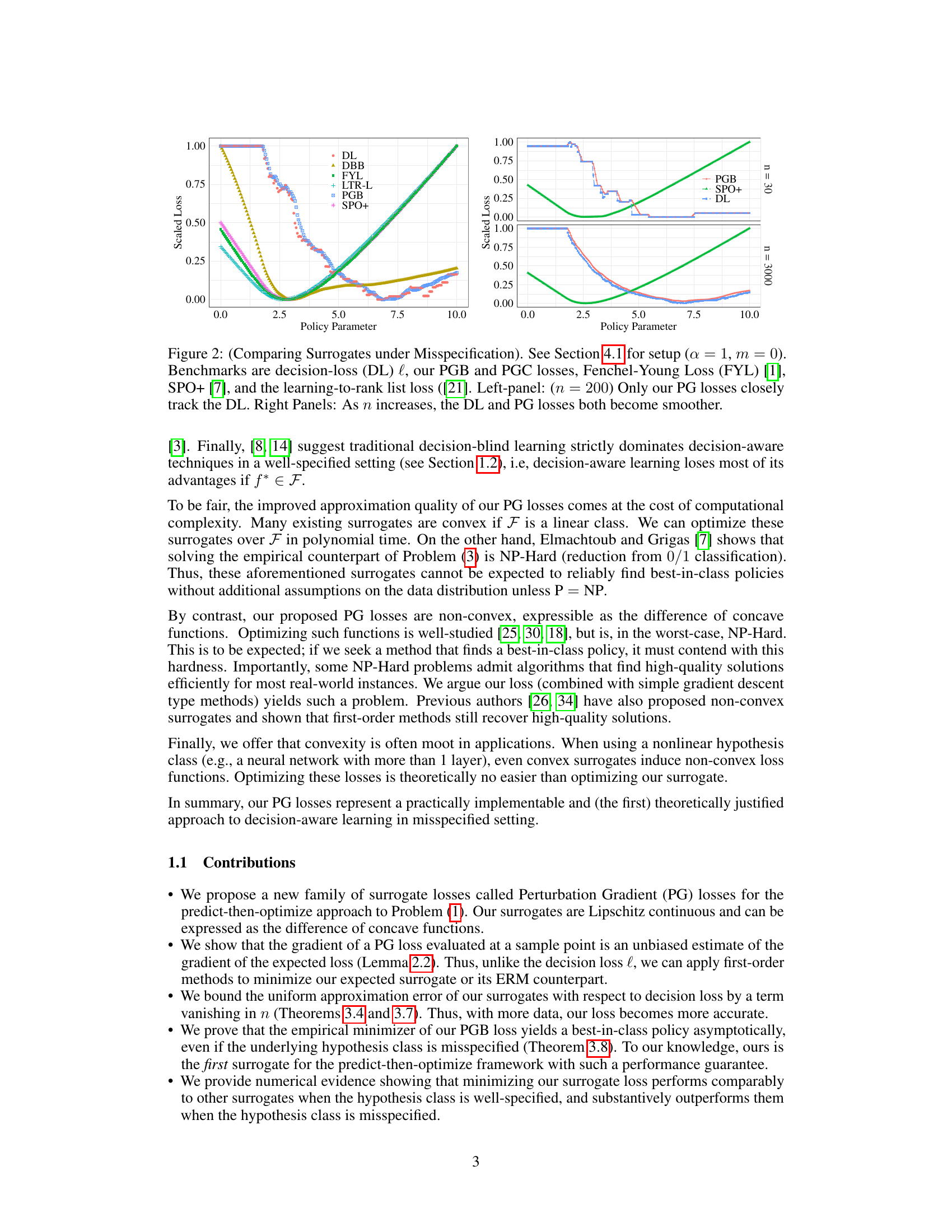

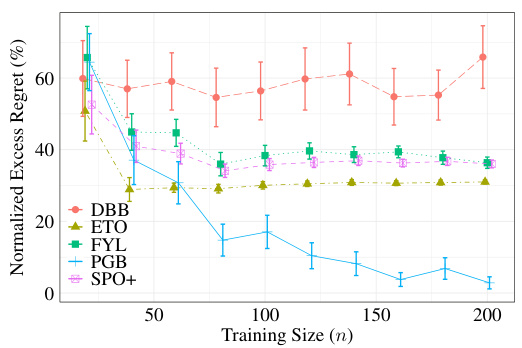

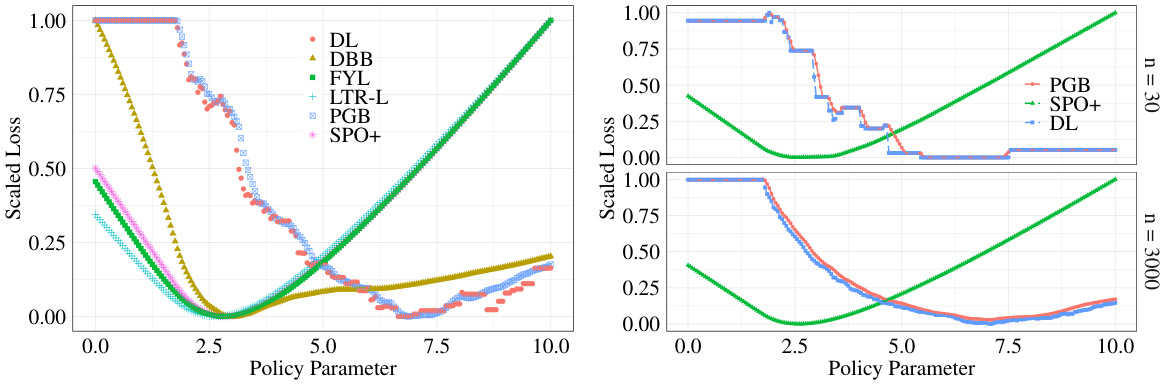

This figure compares different surrogate losses under misspecified settings. The left panel shows that for a small sample size (n=30), only the proposed Perturbation Gradient (PG) losses (PGB and PGC) track the decision loss (DL) closely. The right panel demonstrates that as the sample size increases (n=3000), the DL and PG losses become smoother, while other methods deviate significantly from the DL, indicating that the PG losses are more robust to misspecification as data increases. The figure highlights the improved approximation of PG losses compared to existing approaches under misspecification.

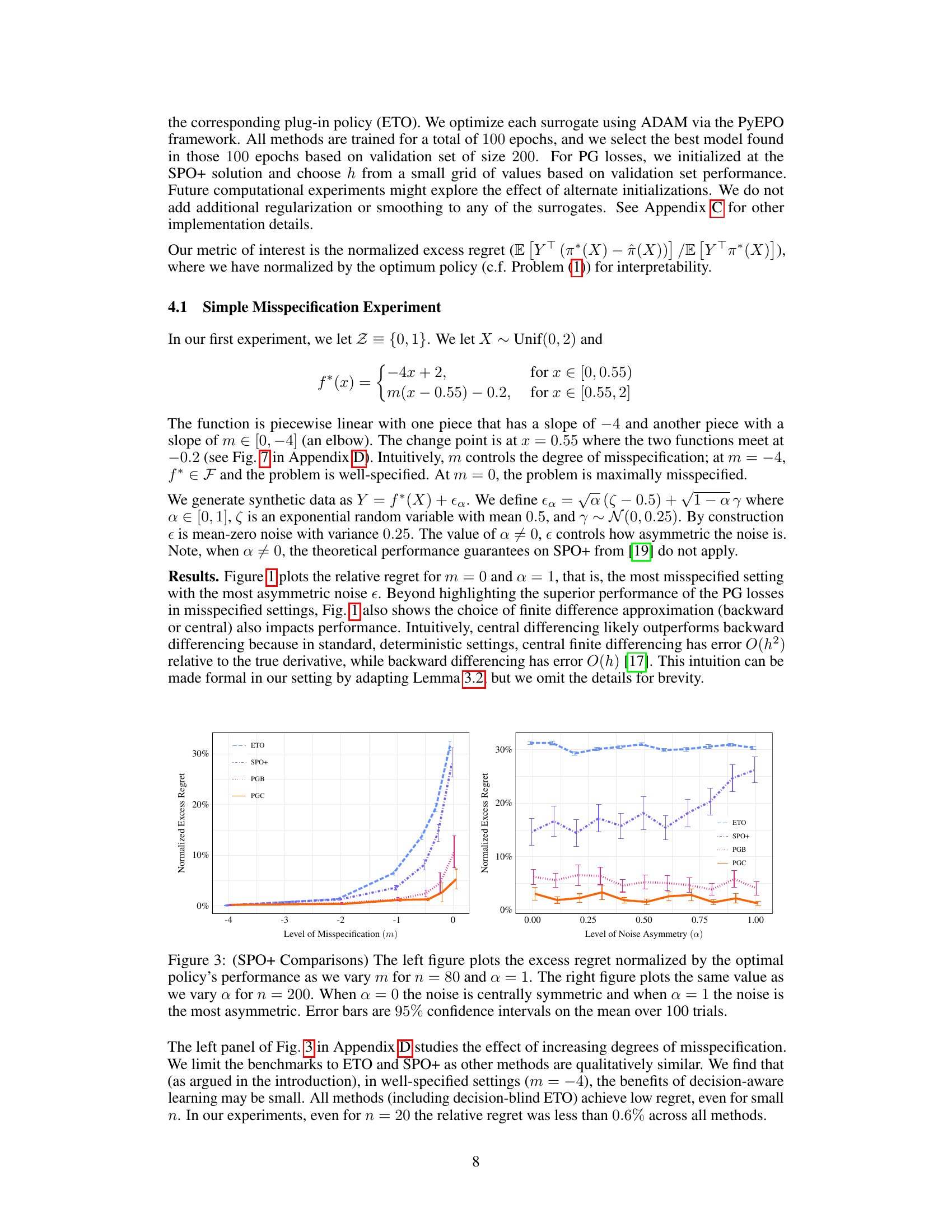

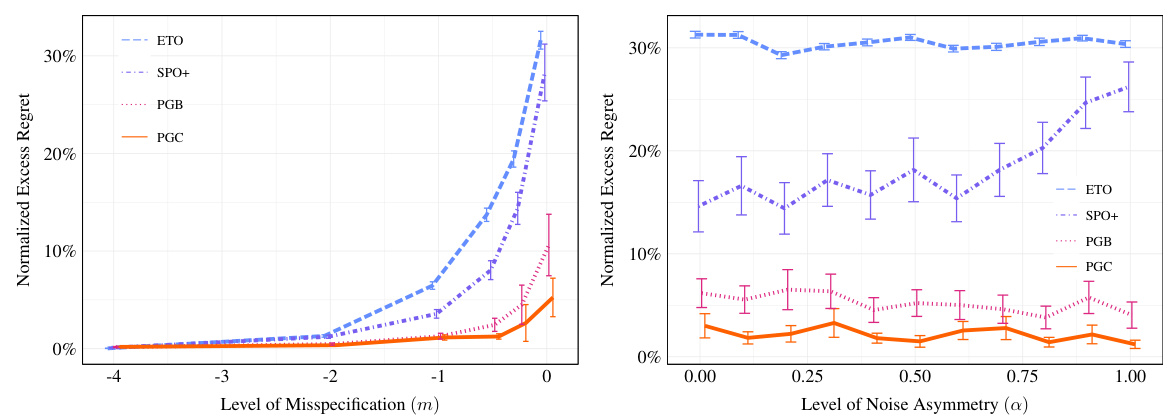

This figure compares the performance of SPO+ with other methods (ETO, PGB, and PGC) under different misspecification levels (m) and noise asymmetry levels (a). The left panel shows that as misspecification increases, the excess regret for decision-aware methods increases more slowly than for decision-blind methods. The right panel shows that the performance of SPO+ is significantly impacted by noise asymmetry, whereas the PG losses remain relatively robust.

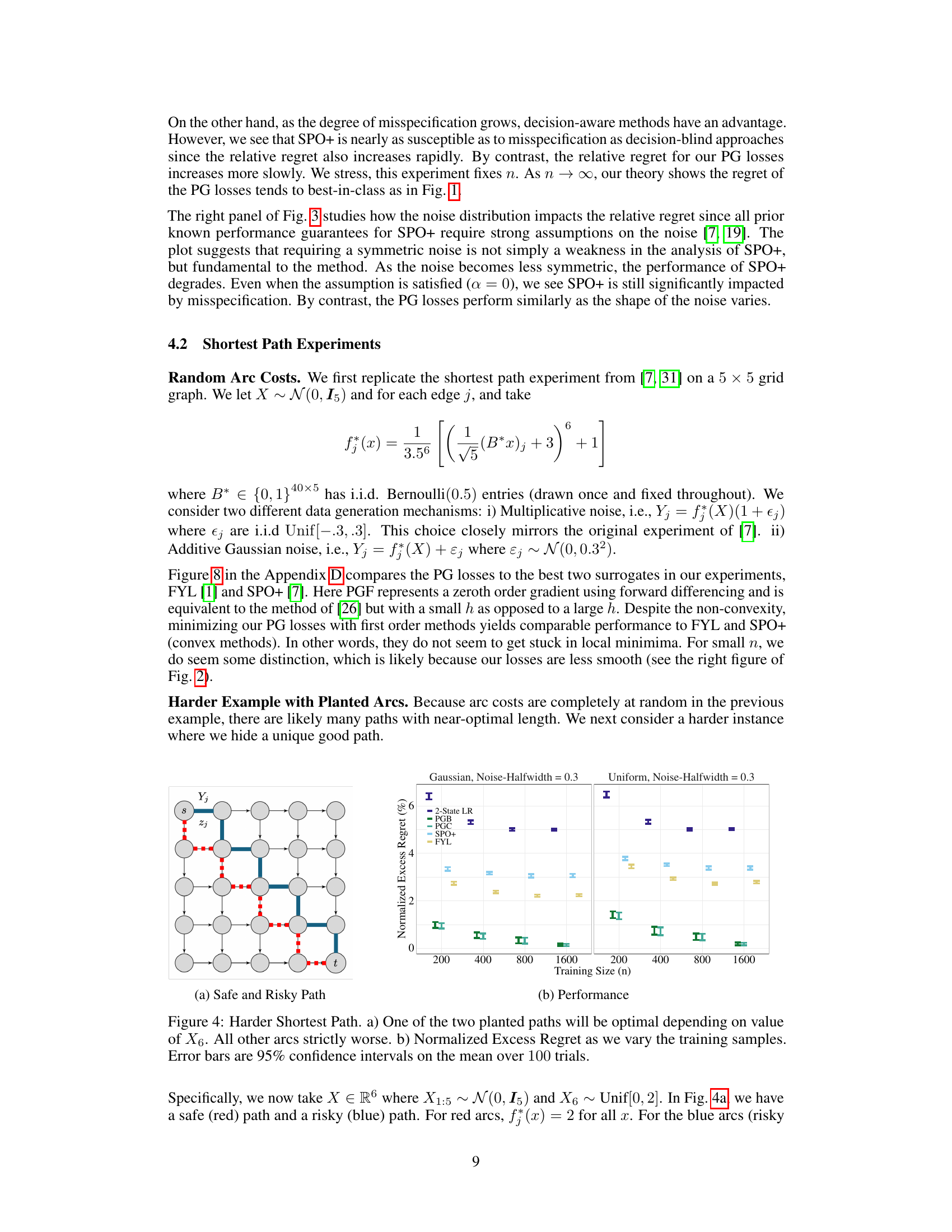

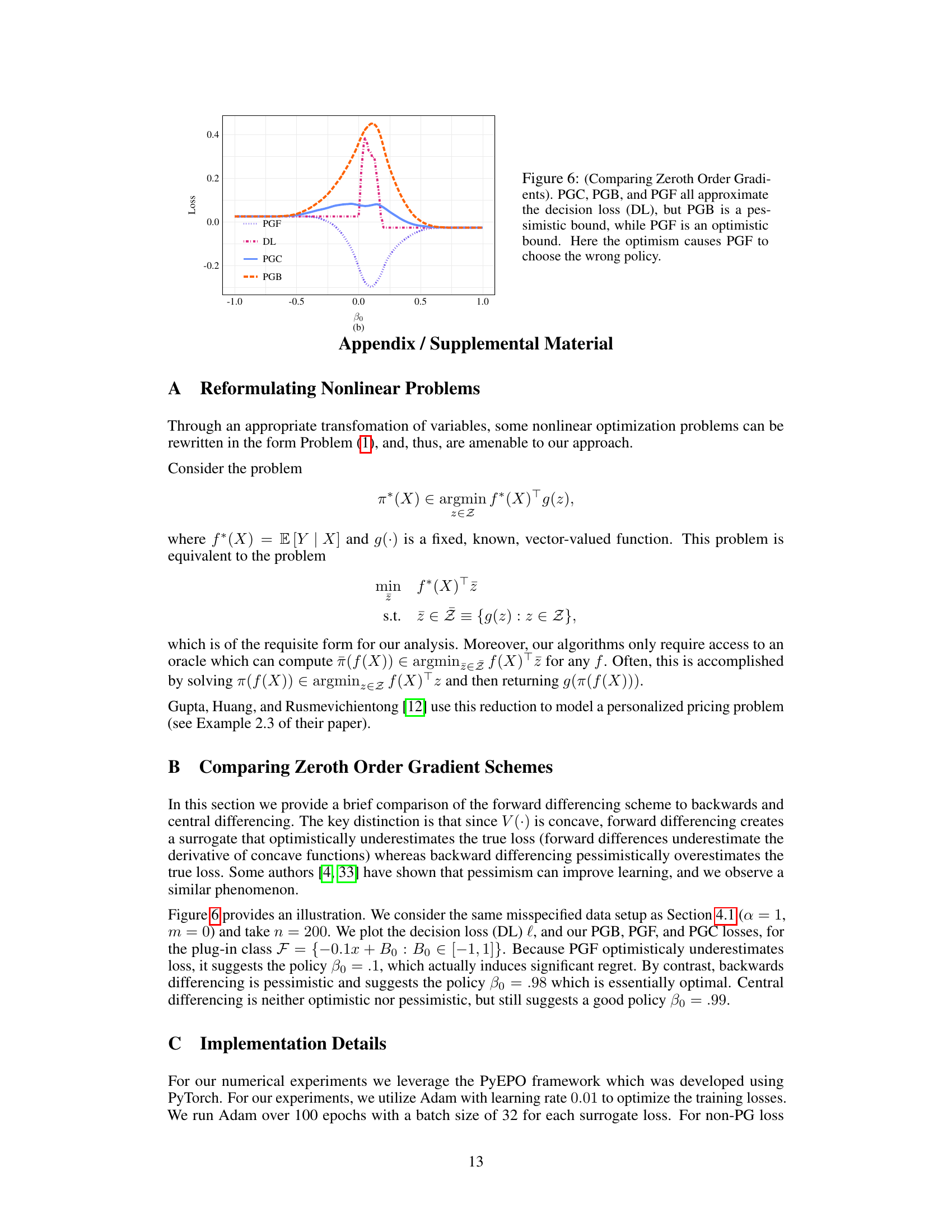

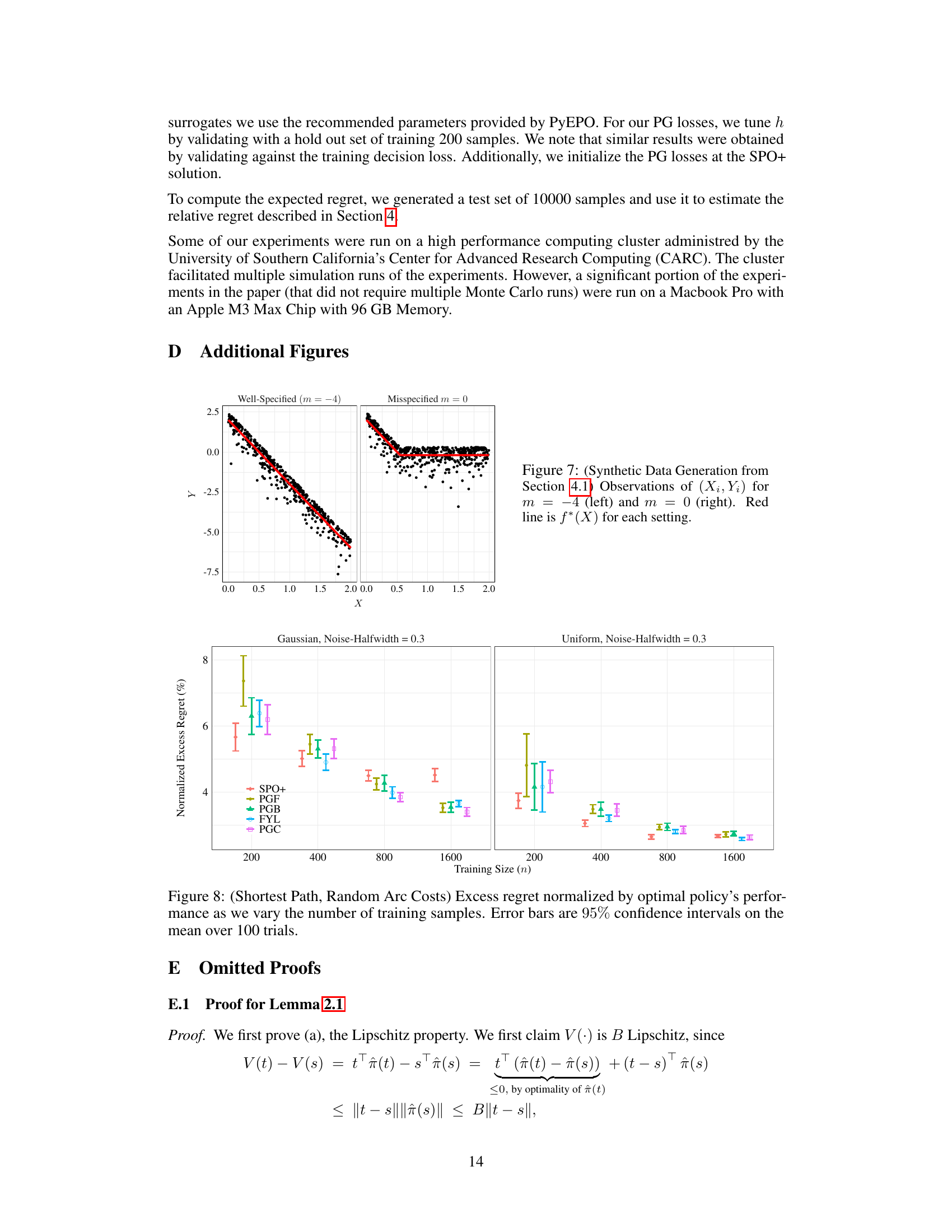

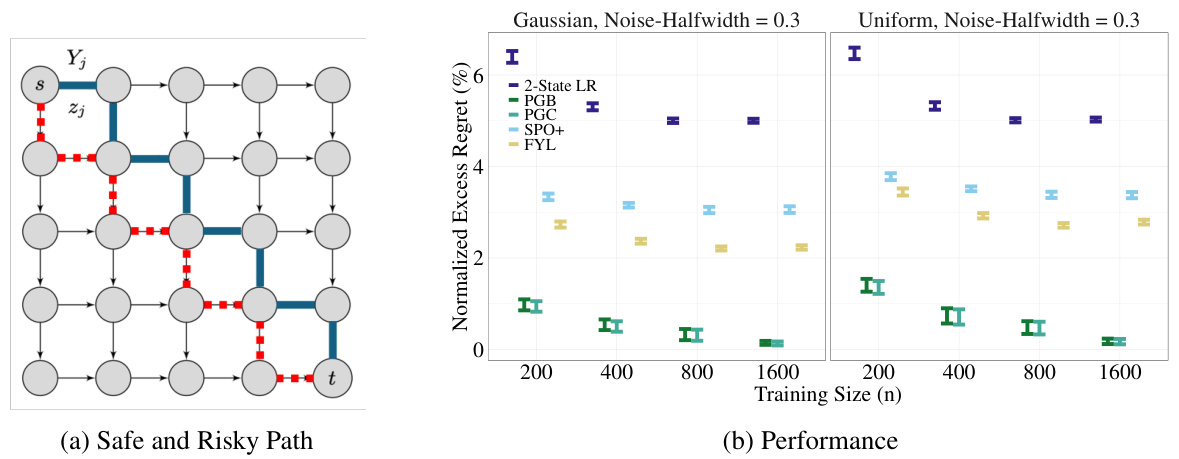

This figure shows the results of a shortest path experiment on a 5x5 grid graph with planted arcs, where one of two paths is optimal depending on the value of X6 (a random variable). Subfigure (a) illustrates the graph structure with safe (red) and risky (blue) paths. Subfigure (b) compares the normalized excess regret of various methods (2-State LR, PGB, PGC, SPO+, FYL) as the training sample size (n) increases for two noise distributions: Gaussian and uniform. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals over 100 trials. The experiment demonstrates that the performance of the proposed PG losses (PGB, PGC) are more robust against misspecification than other methods in scenarios with a more complex structure.

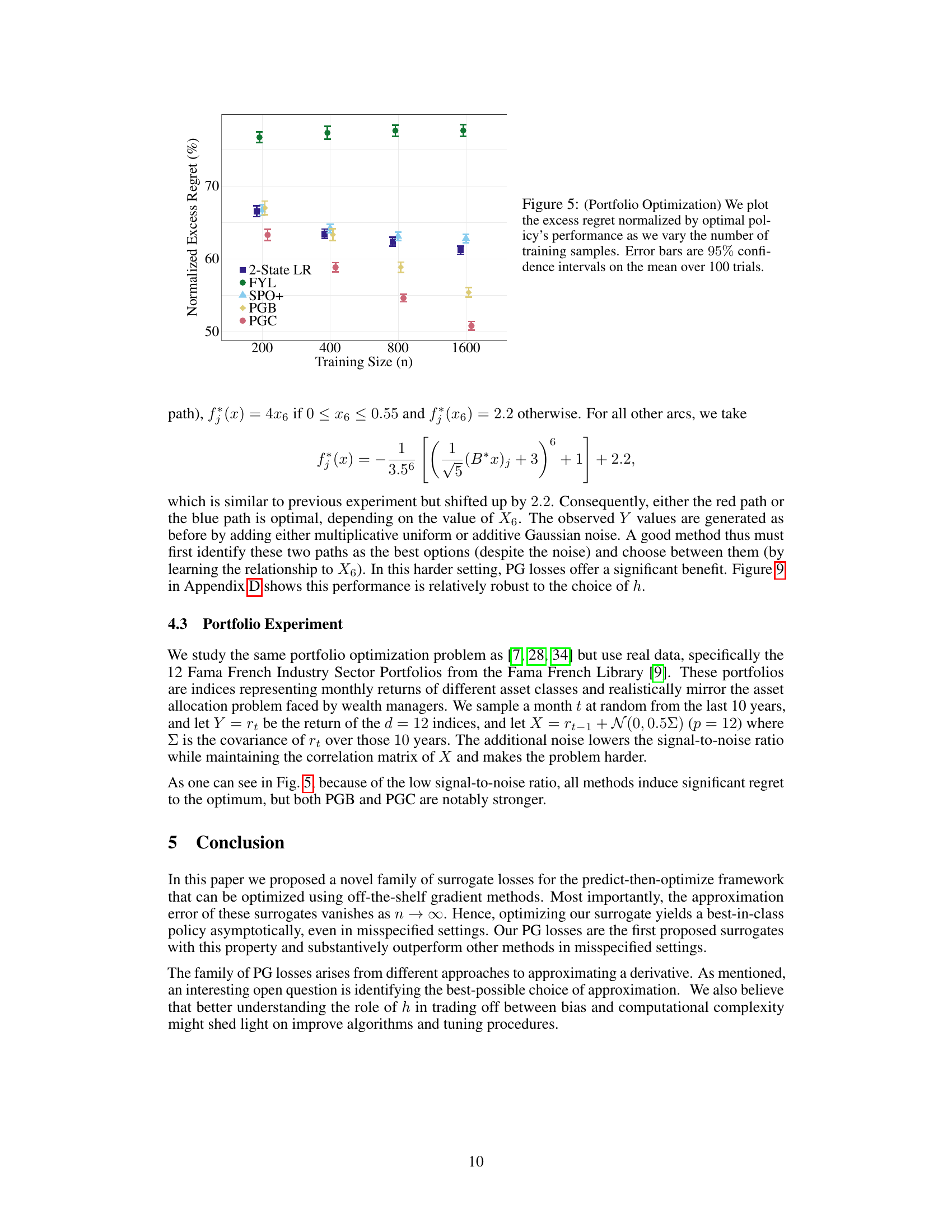

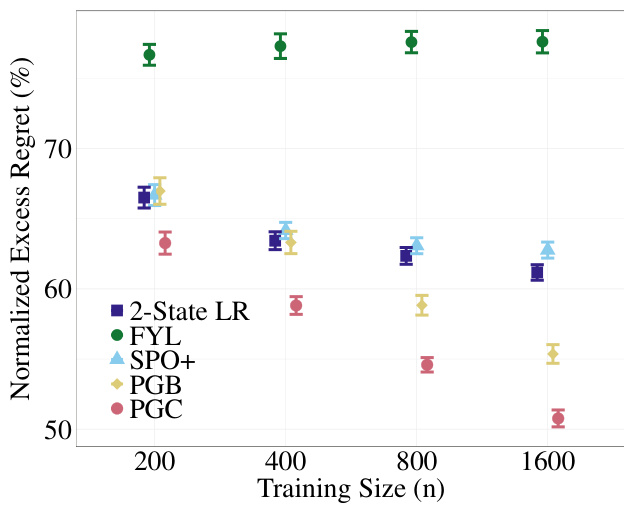

The figure shows the normalized excess regret of different methods for portfolio optimization as the training sample size increases. The normalized excess regret is calculated by dividing the excess regret by the optimal policy’s performance. The plot compares the performance of PGB and PGC losses against other decision-aware surrogates (2-State LR, FYL, SPO+) and the decision-blind approach (ETO). Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals based on 100 trials. This experiment utilizes real-world data (Fama French Industry Sector Portfolios) making the results especially relevant to practical applications.

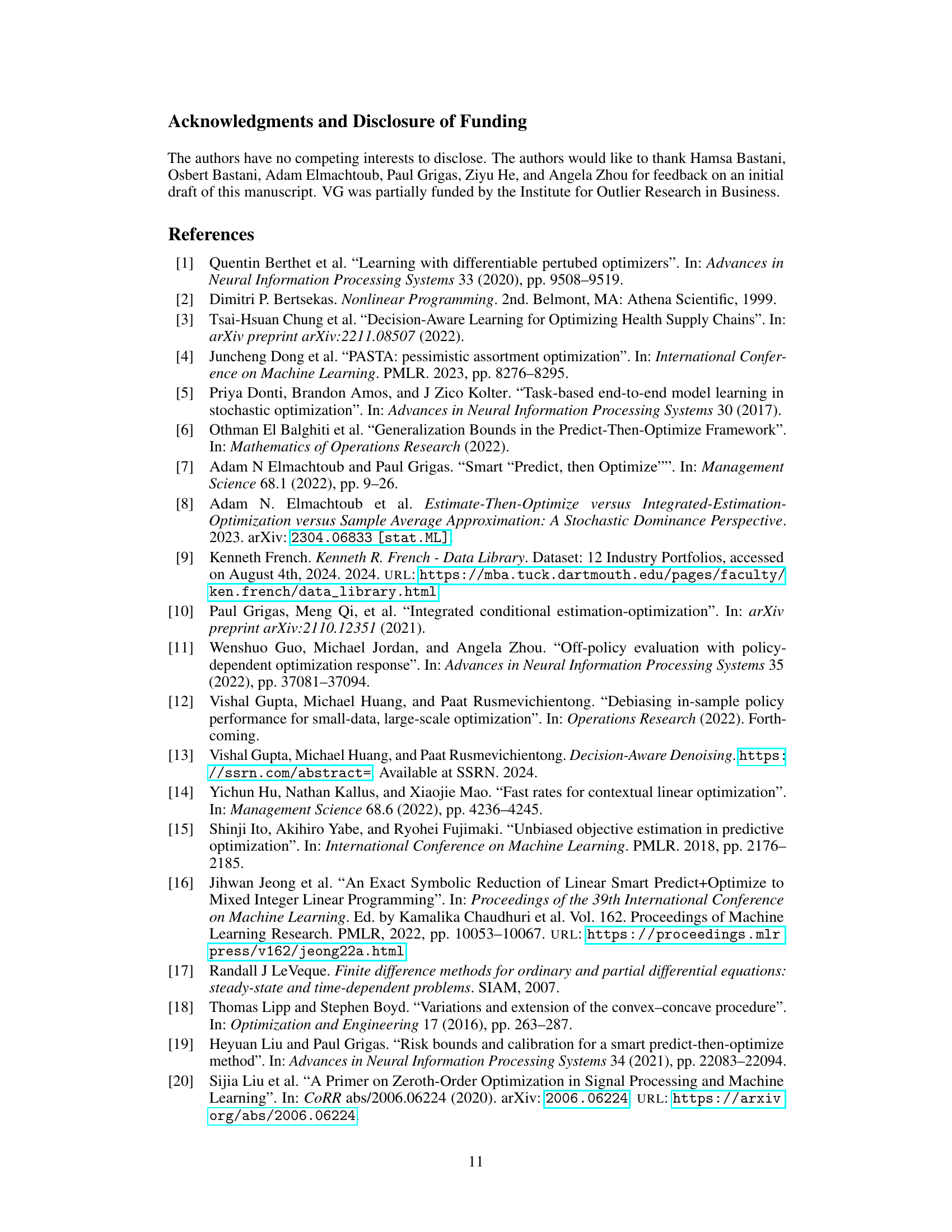

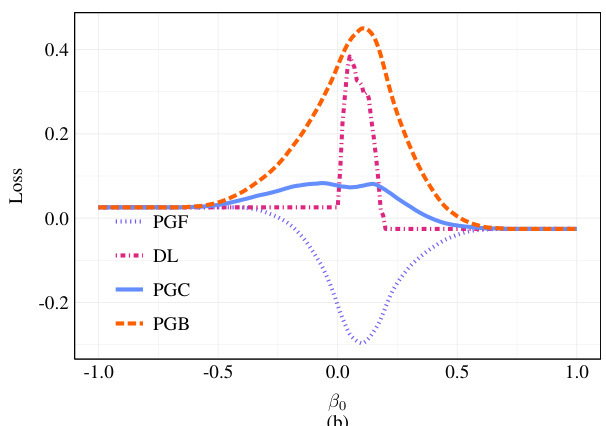

This figure compares three different zeroth-order gradient methods (PGF, PGB, PGC) for approximating the decision loss function (DL). It demonstrates that the choice of approximation method significantly impacts the quality of the approximation. PGB provides a pessimistic approximation, consistently underestimating the DL. PGF offers an optimistic approximation, sometimes overestimating the DL to the point of selecting an entirely incorrect policy. In contrast, PGC produces a more accurate approximation, closely tracking the DL function.

This figure shows the synthetic data generated for the experiments in Section 4.1. The left panel shows data generated under the well-specified setting (m = -4), where the underlying function f* is within the hypothesis class. The right panel shows data from the misspecified setting (m = 0), where f* lies outside of the hypothesis class. The red line in each panel represents the true function f*(X). The scatter plots show the observed data points (Xi, Yi). The difference in the scatter plots illustrates the impact of misspecification on the observed data.

Full paper#