TL;DR#

Interpretable deep learning in relational domains remains a challenge. Concept Bottleneck Models (CBMs) lack relational reasoning capabilities, while relational models such as Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) often sacrifice interpretability. This research introduces Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs), a novel framework combining the strengths of CBMs and GNNs. R-CBMs represent a family of models capable of handling relational data while providing interpretable predictions.

R-CBMs effectively address the limitations of existing methods. The proposed approach matches the generalization performance of traditional black-box models for relational learning, while supporting concept-based explanations. R-CBMs also prove robust across various challenging settings such as limited data or out-of-distribution scenarios. The experimental results highlight the efficacy and versatility of R-CBMs across several relational tasks, from image classification to link prediction. The findings demonstrate the practical potential of the R-CBM framework for building more transparent and reliable AI systems for relational domains.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in relational deep learning and explainable AI. It bridges the gap between powerful but opaque relational models (like GNNs) and interpretable but limited concept-based models (like CBMs). By proposing Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs), the work offers a novel approach to achieving both high performance and interpretability in complex relational settings. This opens up new avenues for building more trustworthy and understandable AI systems.

Visual Insights#

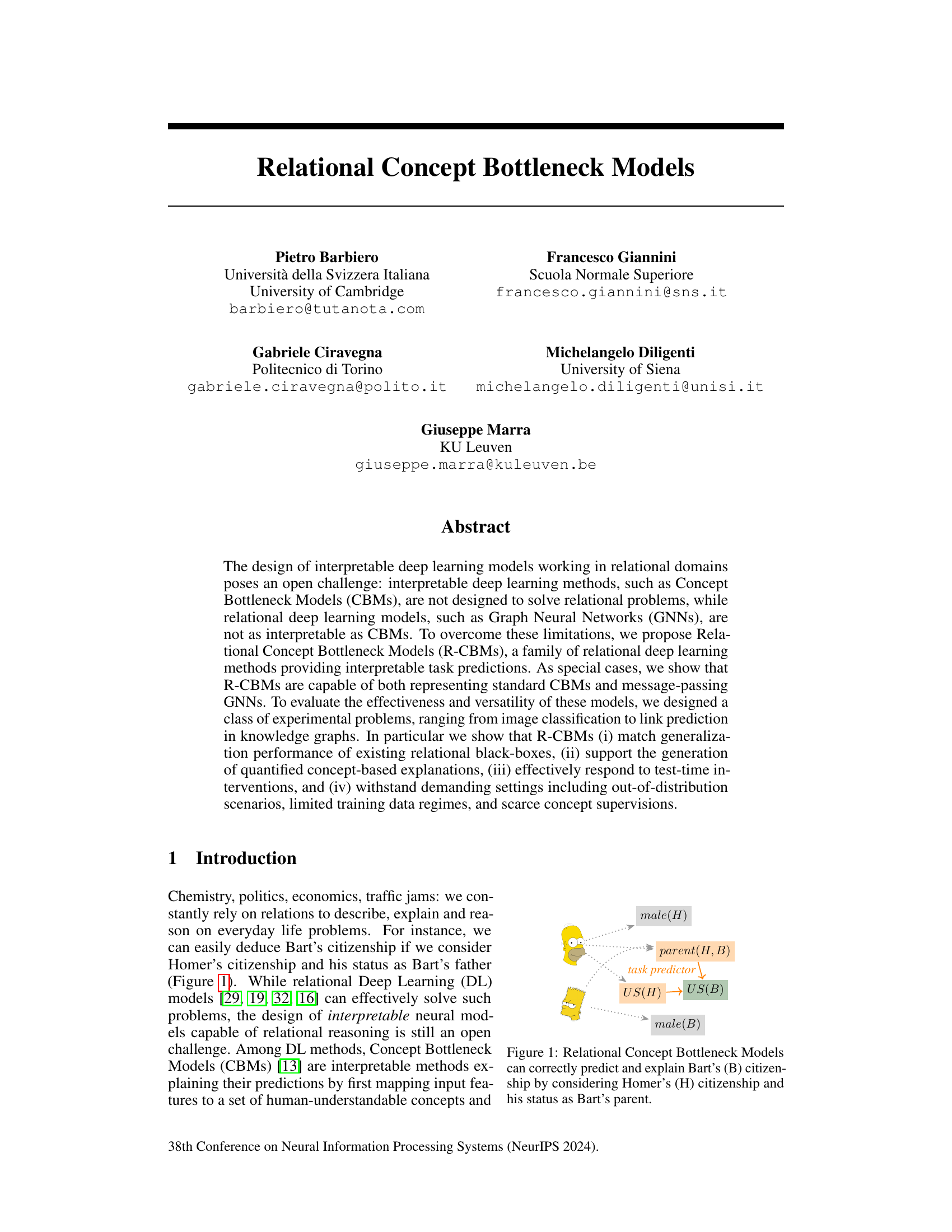

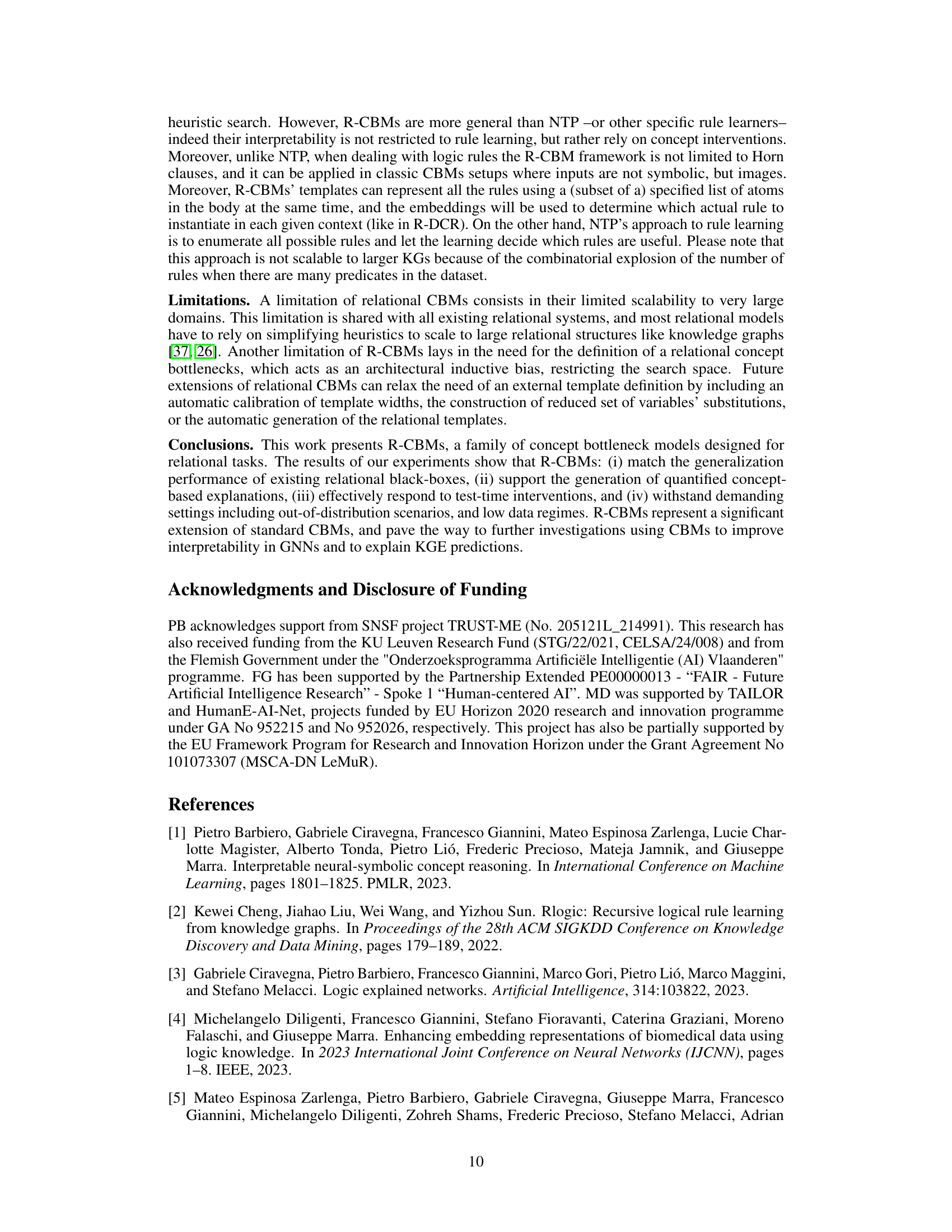

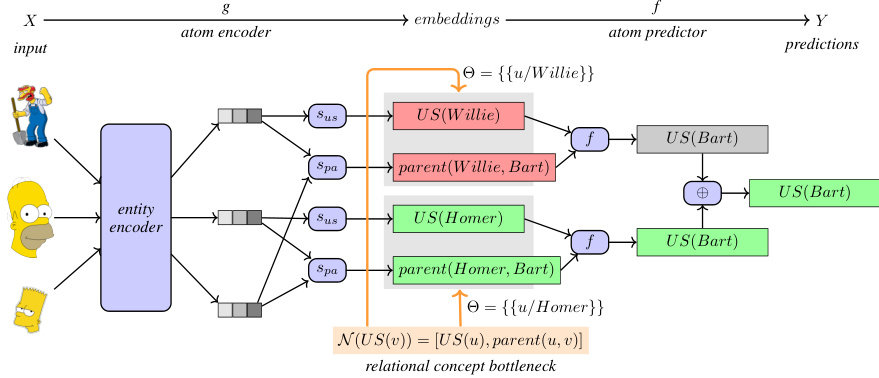

🔼 This figure illustrates the basic architecture of Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs). It shows Homer (H) and Bart (B) as input entities with their features (male(H), parent(H, B), US(H), male(B)). These features are processed through an atom encoder and a task predictor to predict Bart’s citizenship (US(B)). The model uses relational information (e.g., parent relationship) to infer Bart’s citizenship based on Homer’s citizenship and the parent relationship. The orange arrow indicates the inference process from Homer’s features to Bart’s citizenship prediction.

read the caption

Figure 1: Relational Concept Bottleneck Models can correctly predict and explain Bart's (B) citizenship by considering Homer's (H) citizenship and his status as Bart's parent.

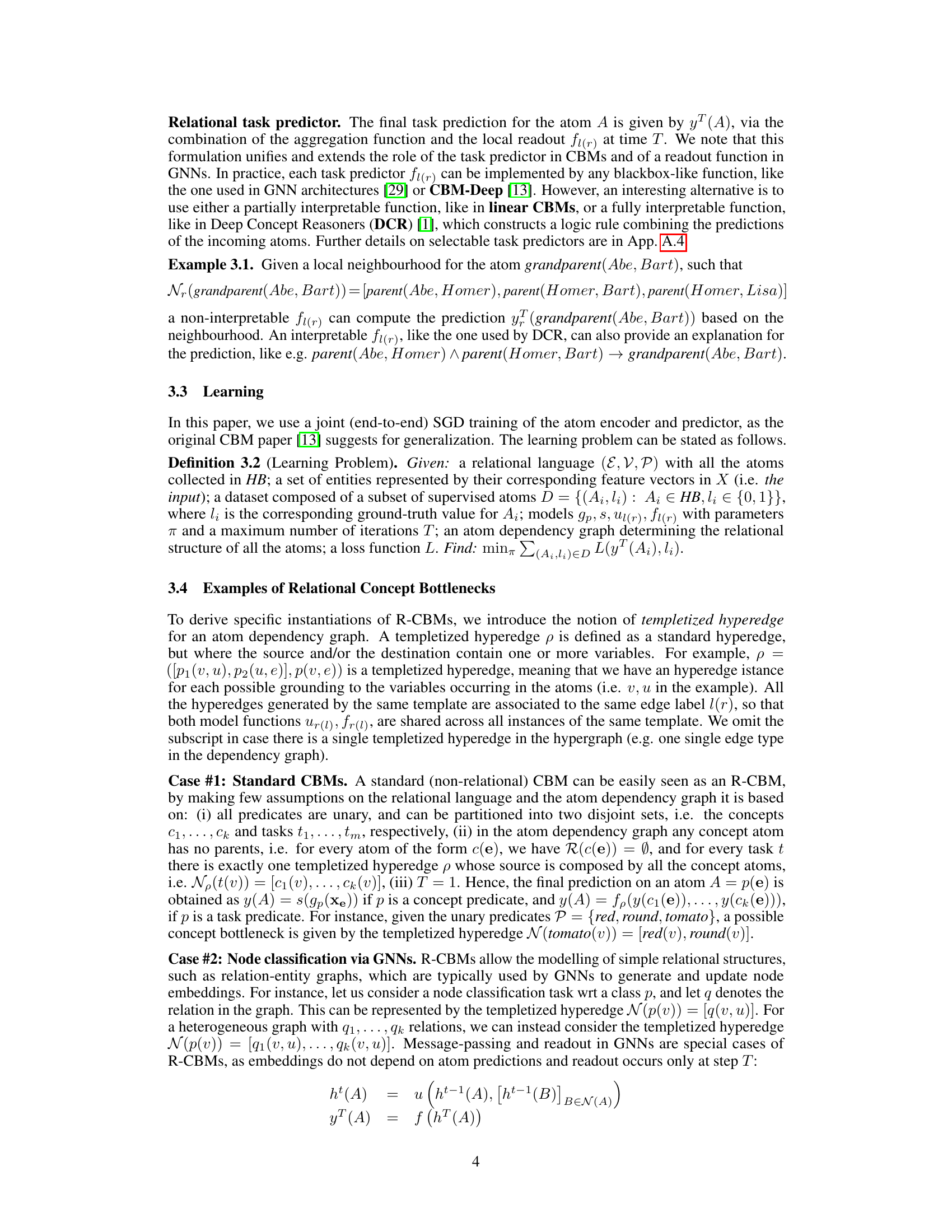

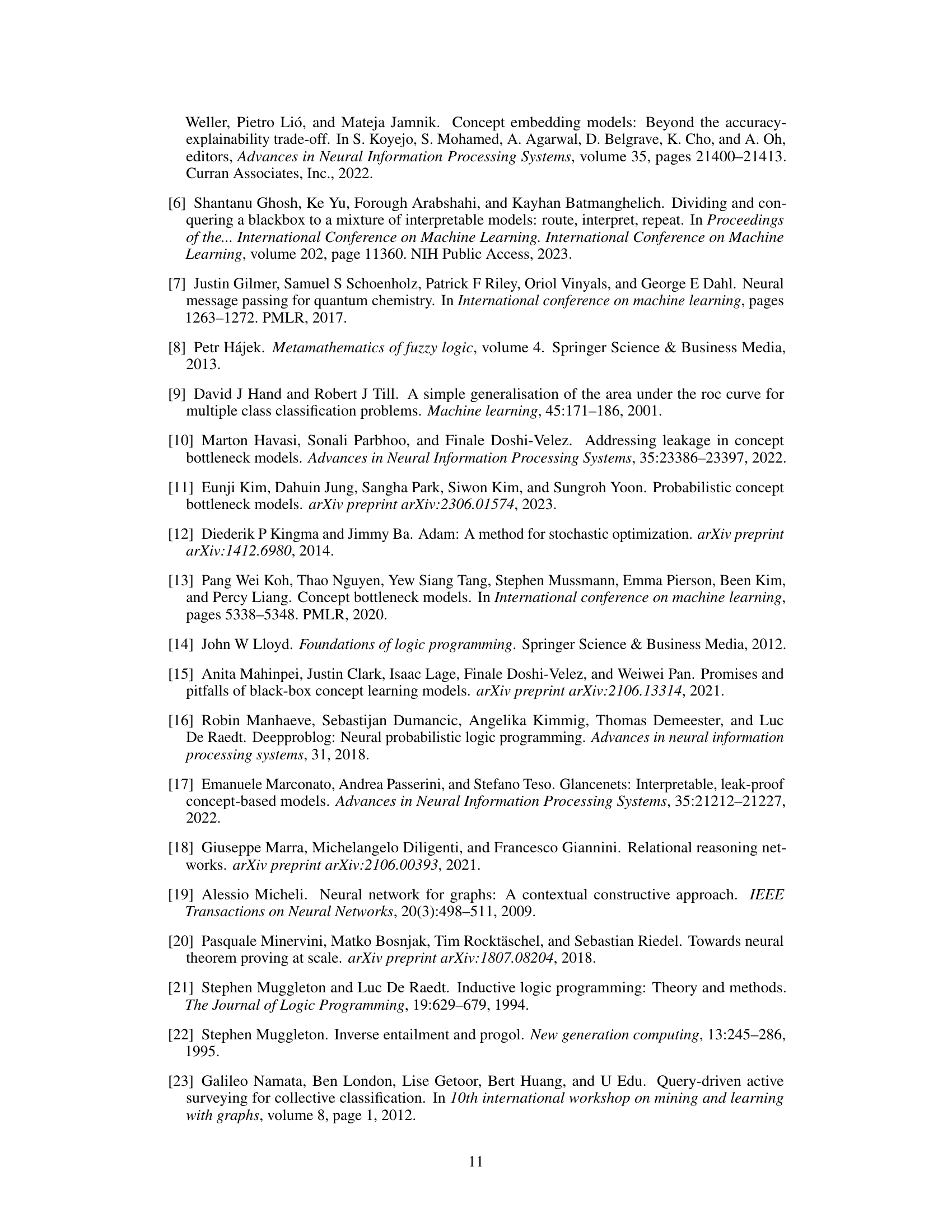

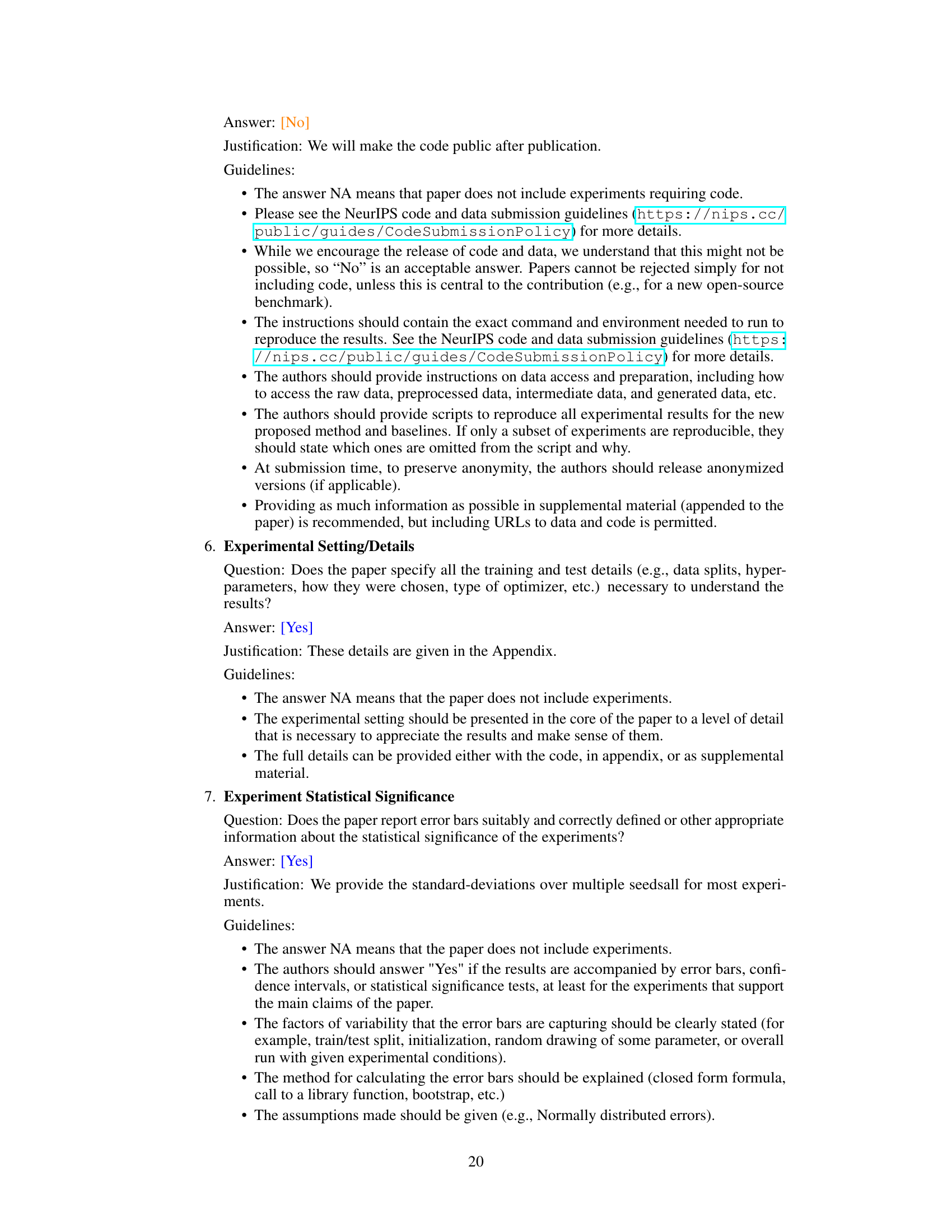

🔼 This table compares the performance of various models, including R-CBMs and standard CBMs, on several relational tasks. It shows that R-CBMs generalize well across different datasets and task types. The table also indicates where certain models were not applicable (A) or took too long to train (OOT). The performance metrics used vary depending on the specific task (ROC-AUC, Accuracy, MRR).

read the caption

Table 1: Models' performance on task generalization. R-CBMs generalize well in relational tasks. A indicates methods that cannot be applied due to the dataset structure. OOT indicates out-of-time training due to large domains.

In-depth insights#

Relational CBMs#

Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs) offer a novel approach to integrating the interpretability of Concept Bottleneck Models (CBMs) with the relational reasoning capabilities of Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). R-CBMs address the limitations of traditional CBMs in handling relational data by extending the concept of a bottleneck to relational structures, represented as hypergraphs where nodes are atoms and hyperedges represent relational concept bottlenecks. This allows R-CBMs to model complex dependencies between multiple entities, unlike standard CBMs which process single entities. A key strength is the ability to derive first-order logic explanations from the model’s predictions, enhancing interpretability. The paper demonstrates that R-CBMs achieve comparable generalization performance to relational black-box models across various tasks while maintaining their interpretability. Their effectiveness is further shown through resilience to out-of-distribution scenarios and robustness to limited training data. The flexible architecture allows for both standard CBM and GNN-like behaviors, highlighting the versatility of R-CBMs as a powerful tool for relational deep learning.

Interpretable Models#

The concept of “Interpretable Models” is central to the responsible development and deployment of machine learning systems, especially in high-stakes applications. Explainability is paramount; understanding why a model makes a specific prediction is crucial for building trust and ensuring accountability. Concept Bottleneck Models (CBMs), for instance, represent one approach to achieving interpretability by mapping input features to a set of human-understandable concepts, thereby providing insights into the model’s decision-making process. However, traditional CBMs often struggle with relational data, a limitation addressed by the paper’s introduction of Relational CBMs (R-CBMs). R-CBMs offer a powerful framework for integrating relational reasoning capabilities with interpretability, enhancing our ability to understand model behavior in complex domains, such as knowledge graphs and chemistry. This is a significant advance, as bridging the gap between interpretability and the ability to handle complex relational structures is a key challenge in the field. Furthermore, the effectiveness of R-CBMs is demonstrated through rigorous empirical evaluations, emphasizing the importance of both theoretical soundness and practical performance in the pursuit of interpretable models.

Intervention Effects#

The concept of ‘Intervention Effects’ in a research paper likely explores how external manipulations or changes affect the system or model under study. This could involve various methods, such as modifying input features, removing or adding data points, or altering model parameters. Analyzing these effects reveals crucial insights into the model’s robustness, its reliance on specific factors, and its overall behavior. Positive intervention effects might demonstrate improvements in accuracy or efficiency, highlighting beneficial aspects of the model’s design or training. Negative intervention effects, conversely, might reveal vulnerabilities or unexpected sensitivities. A comprehensive analysis should include a range of interventions, quantification of the observed changes, and thoughtful discussion of the underlying reasons behind those effects. The ultimate goal is to build a stronger, more robust, and better-understood system through targeted interventions.

Generalization#

The study’s findings on generalization reveal a significant advantage for relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs) over traditional CBMs, especially in relational tasks. Standard CBMs struggle to generalize, exhibiting performance only slightly better than random guessing. This limitation stems from their inability to handle multiple entities simultaneously, a crucial aspect of relational problems. In contrast, R-CBMs demonstrate robust generalization, achieving performance comparable to, and sometimes exceeding, that of black-box relational models such as GNNs. This superior performance is consistent across diverse tasks and datasets, highlighting the effectiveness of R-CBMs’ design for relational reasoning. Moreover, R-CBMs maintain their strong generalization even in challenging scenarios such as out-of-distribution settings and low data regimes, further emphasizing their versatility and adaptability. The results suggest that R-CBMs offer a powerful alternative for tackling complex relational tasks while providing interpretability absent in traditional black-box methods.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this Relational Concept Bottleneck Model (R-CBM) work could explore scalability enhancements for handling extremely large knowledge graphs, a current limitation. Addressing this would involve investigating more efficient graph traversal techniques and potentially exploring distributed or approximate inference methods. Another avenue is to relax the need for predefined relational concept bottlenecks, perhaps by developing methods to automatically learn or discover these structures from data, improving the model’s adaptability to diverse relational problems. Further investigation into the theoretical properties of R-CBMs, including a deeper analysis of their expressiveness and limitations in comparison to other relational learning models, is warranted. Finally, exploring more complex aggregation strategies beyond the max operation for combining atom predictions could lead to improved performance and interpretability. This may involve considering weighted aggregations or other sophisticated fusion techniques, particularly for tasks requiring nuanced evaluations of multiple relational concepts.

More visual insights#

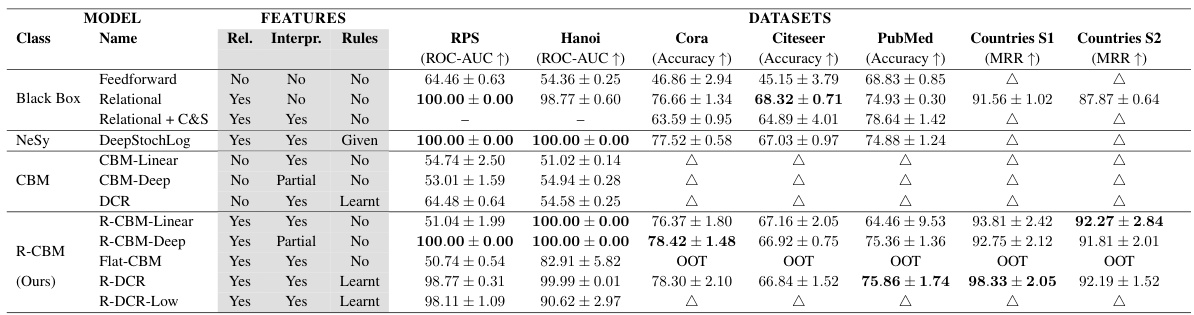

More on figures

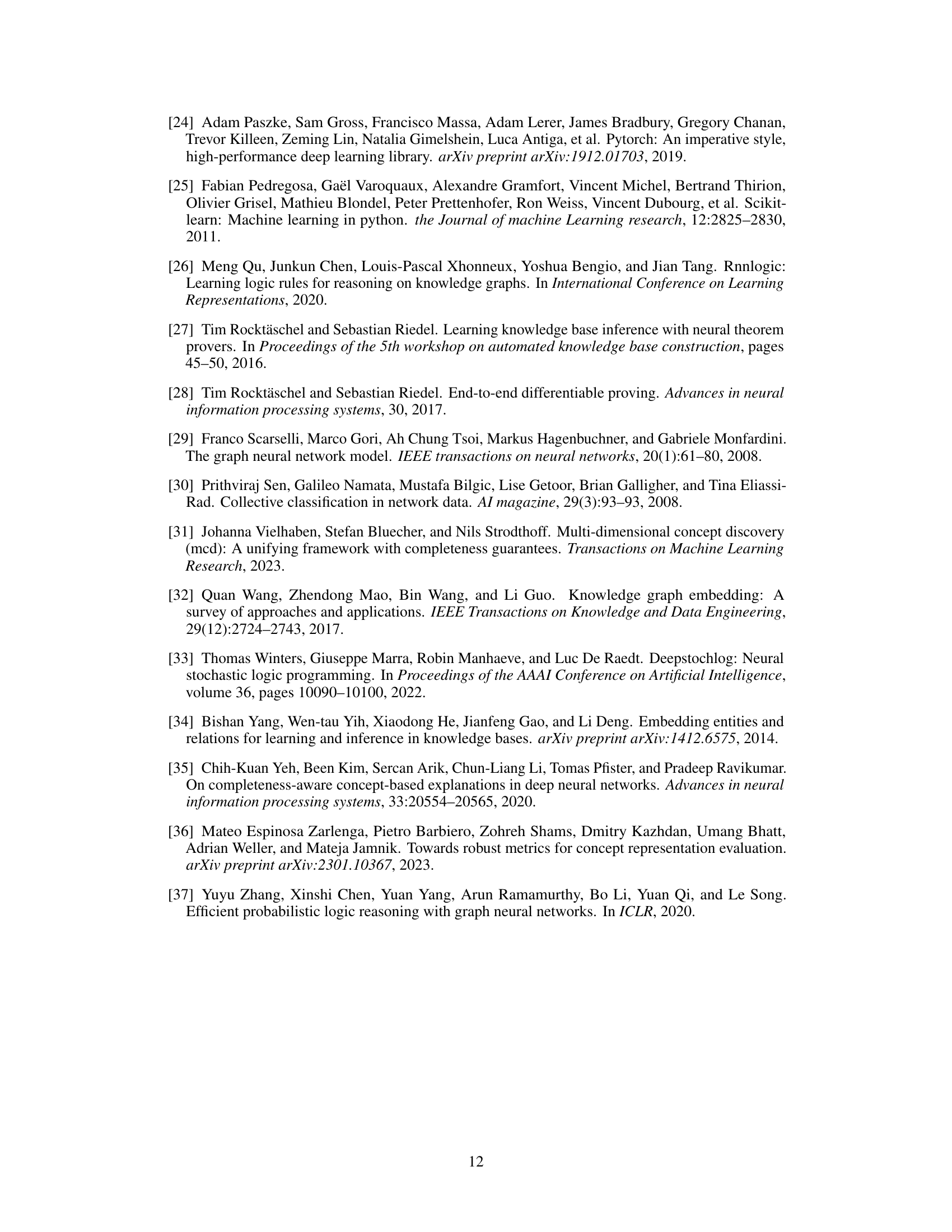

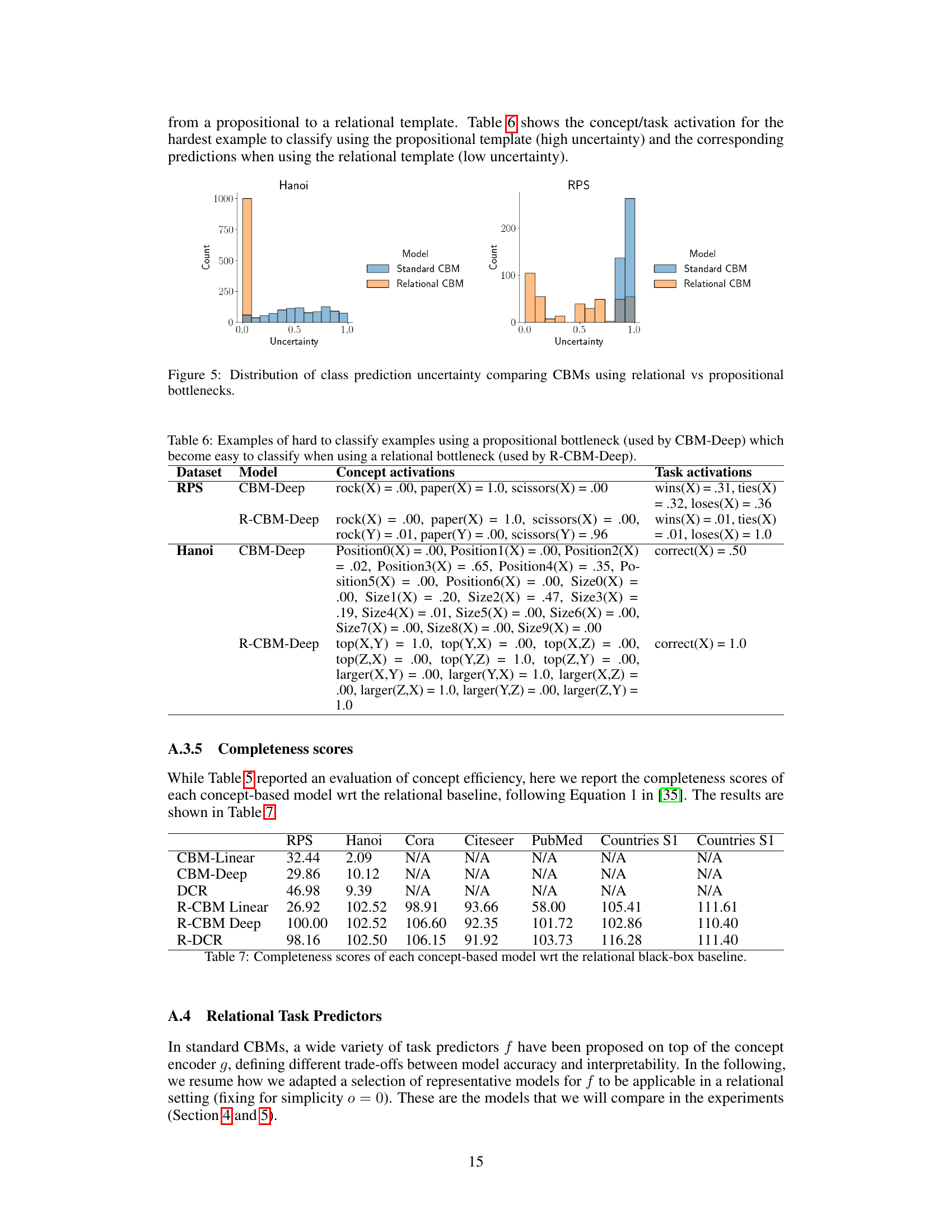

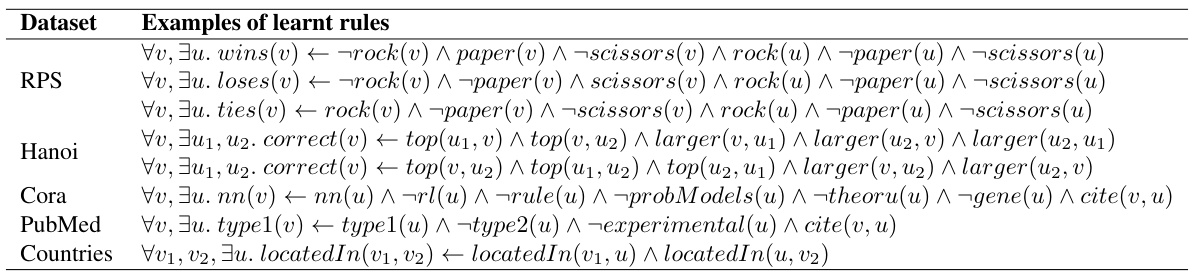

🔼 This figure illustrates the atom dependency graph used in Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs). Each node represents a ground atom, and hyperedges (directed) represent the dependencies between atoms. The figure shows that a target atom, p4(b), can be predicted from two different sets of source atoms, represented by different colored hyperedges. This exemplifies how R-CBMs consider multiple dependency paths when making predictions, unlike standard CBMs that only process one input at a time. The orange hyperedges represent one pathway to predict p4(b) whereas the violet hyperedges represent an alternative pathway.

read the caption

Figure 2: The graph represents the dependencies among the atoms. Here, the atom p4(b) can be predicted either from the orange [p3(b), p2(a, b), p1(b, a)] or violet [p1(b, c), p2(c, b)] tuples of neighbours. We used different colors to identify different hyperedges.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs). It shows how input entities are encoded into ground atoms representing facts or relationships (i). These atoms then pass through a relational bottleneck which selectively chooses relevant concept atoms based on possible variable substitutions (ii). A task predictor processes these selected atoms generating predictions for the task (iii), and finally, an aggregator combines these predictions to arrive at a final prediction (iv). The red and green colors indicate whether the ground atom is labelled true or false.

read the caption

Figure 3: In R-CBMs (i) the atom encoder g maps input entities to a set of ground atoms (red/green indicate the ground atom label false/true), (ii) the relational bottleneck guides the selection of concept atoms by considering all the possible variable substitutions in Θ, (iii) the atom predictor f maps the selected atoms into a task prediction, and (iv) the aggregator combines all evidence into a final task prediction.

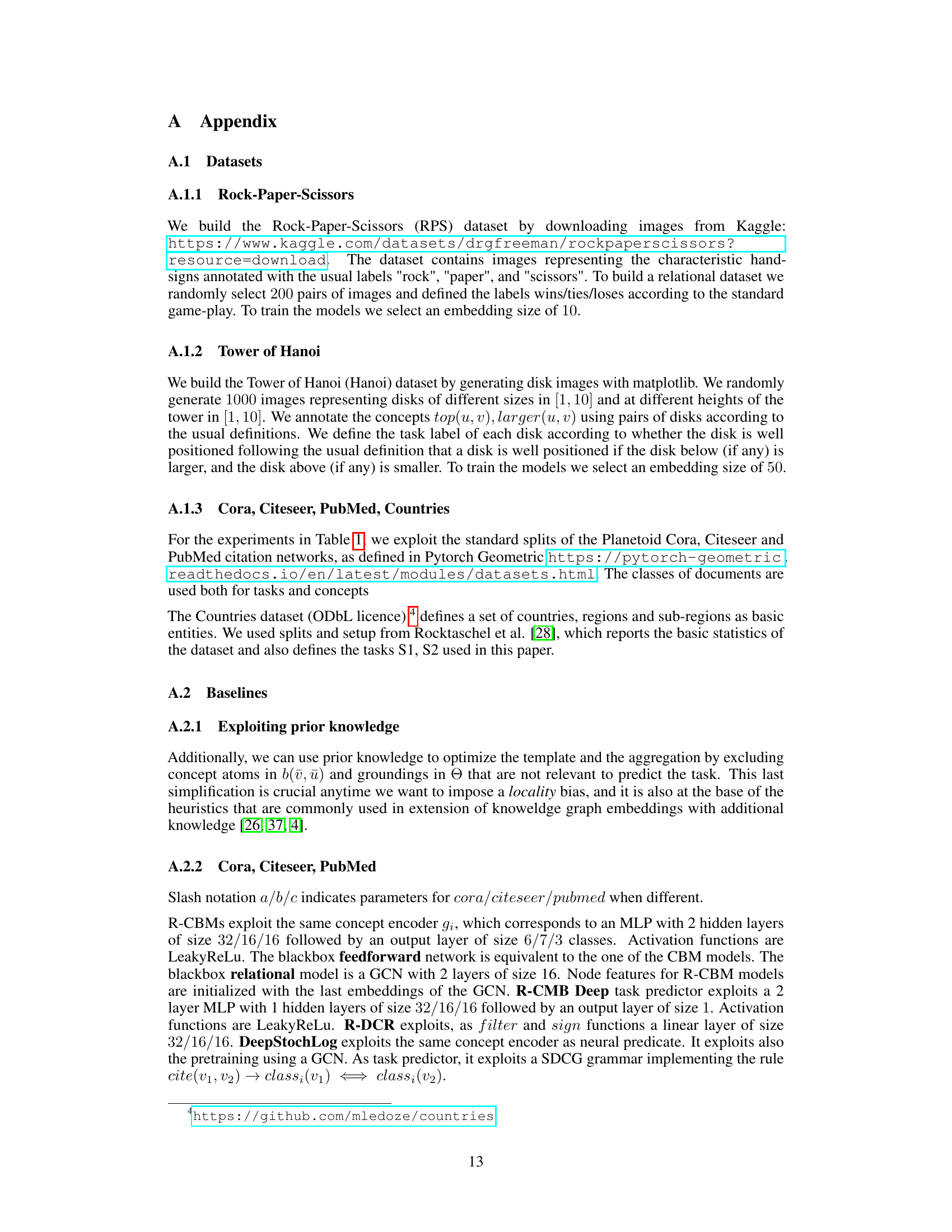

🔼 This figure shows the results of an out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization experiment using the Tower of Hanoi dataset. The x-axis represents the number of disks in the test set, while the y-axis represents the task AUC (Area Under the ROC Curve). Different models are compared: R-CBM, Relational Black Box, Flat-CBM, and CBM. The results demonstrate that R-CBMs are significantly more robust to OOD scenarios, maintaining high performance even when the test set has a larger number of disks (more complexity) than the training set. Other models’ performance degrades sharply in these OOD scenarios.

read the caption

Figure 4: Model generalization on Hanoi OOD on the number of disks. Only R-CBMs are able to generalize effectively to settings larger than the ones they are trained on.

🔼 This figure illustrates the architecture of Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs). It shows how the model processes input entities, maps them to ground atoms, uses a relational bottleneck to select relevant concept atoms, predicts task outcomes based on selected atoms, and finally aggregates these predictions for the final output. The use of red and green to indicate true/false ground atom labels highlights the interpretability aspect of the model.

read the caption

Figure 3: In R-CBMs (i) the atom encoder g maps input entities to a set of ground atoms (red/green indicate the ground atom label false/true), (ii) the relational bottleneck guides the selection of concept atoms by considering all the possible variable substitutions in Θ, (iii) the atom predictor f maps the selected atoms into a task prediction, and (iv) the aggregator combines all evidence into a final task prediction.

More on tables

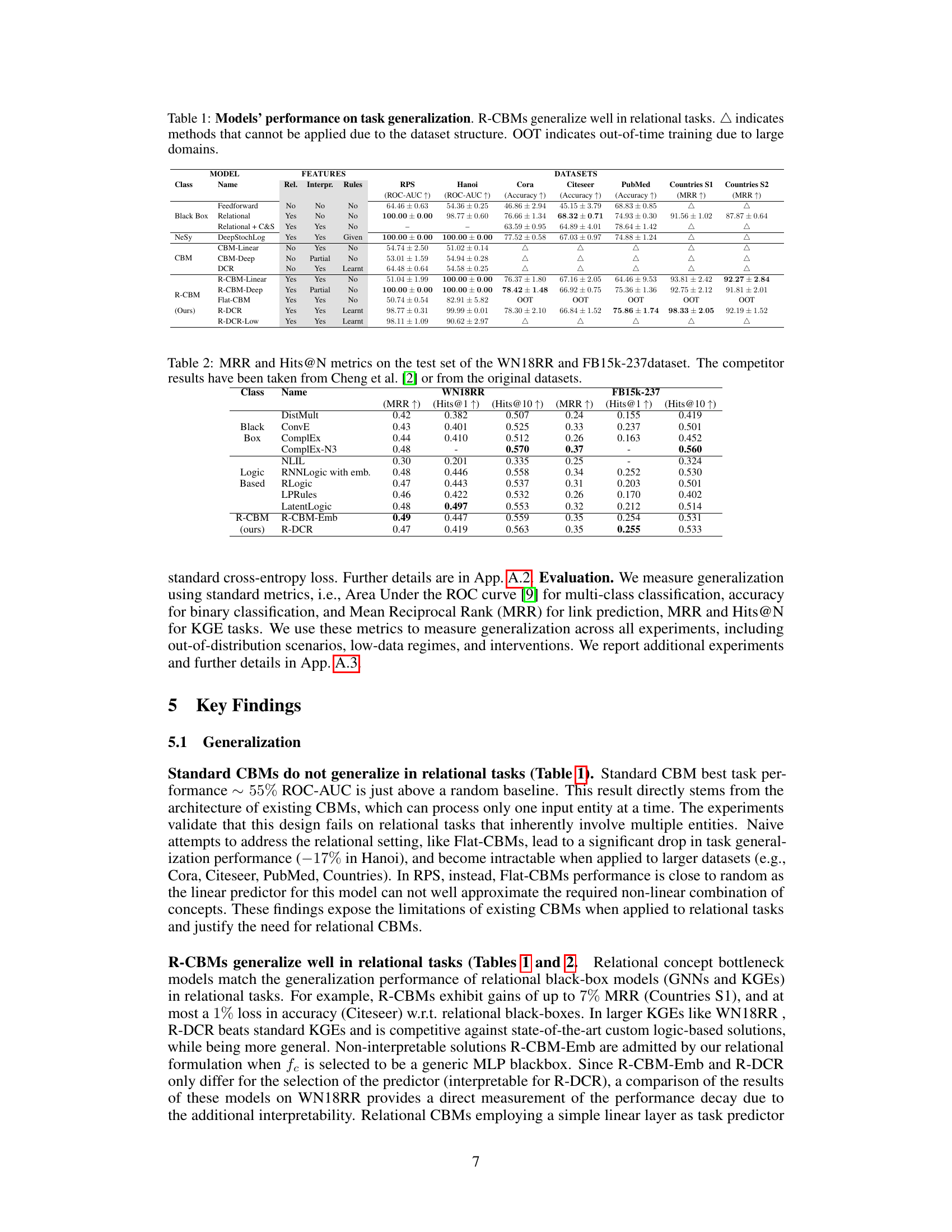

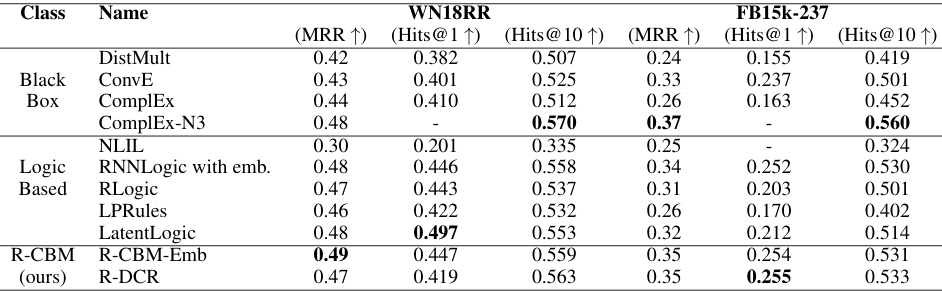

🔼 This table compares the performance of Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs) with other state-of-the-art methods on two knowledge graph datasets, WN18RR and FB15k-237. The metrics used are Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR) and Hits@N (the proportion of correct answers within the top N predictions). The table shows that R-CBMs achieve competitive performance compared to existing approaches.

read the caption

Table 2: MRR and Hits@N metrics on the test set of the WN18RR and FB15k-237dataset. The competitor results have been taken from Cheng et al. [2] or from the original datasets.

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the effectiveness of different Concept Bottleneck Models (CBMs) in responding to human interventions. The experiments involved introducing adversarial examples that caused concept encoders to mispredict concepts. The table shows the performance (in terms of AUC) of different models before and after the interventions. The results demonstrate that Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs) are more effective at responding to interventions than standard CBMs.

read the caption

Table 3: CBMs response to interventions. R-CBMs effectively respond to human interventions.

🔼 This table presents the performance of various models on task generalization across different datasets. It compares the performance of Relational Concept Bottleneck Models (R-CBMs) against standard CBMs, black-box relational models, and other relational methods. The datasets represent diverse relational tasks, including image classification, link prediction, and node classification. The table highlights the ability of R-CBMs to generalize well to relational tasks, even outperforming other methods in several instances. The ‘A’ indicates that some methods were not applicable to certain datasets due to structural constraints, while ‘OOT’ denotes instances where training ran out of time due to the scale of the dataset.

read the caption

Table 1: Models' performance on task generalization. R-CBMs generalize well in relational tasks. A indicates methods that cannot be applied due to the dataset structure. OOT indicates out-of-time training due to large domains.

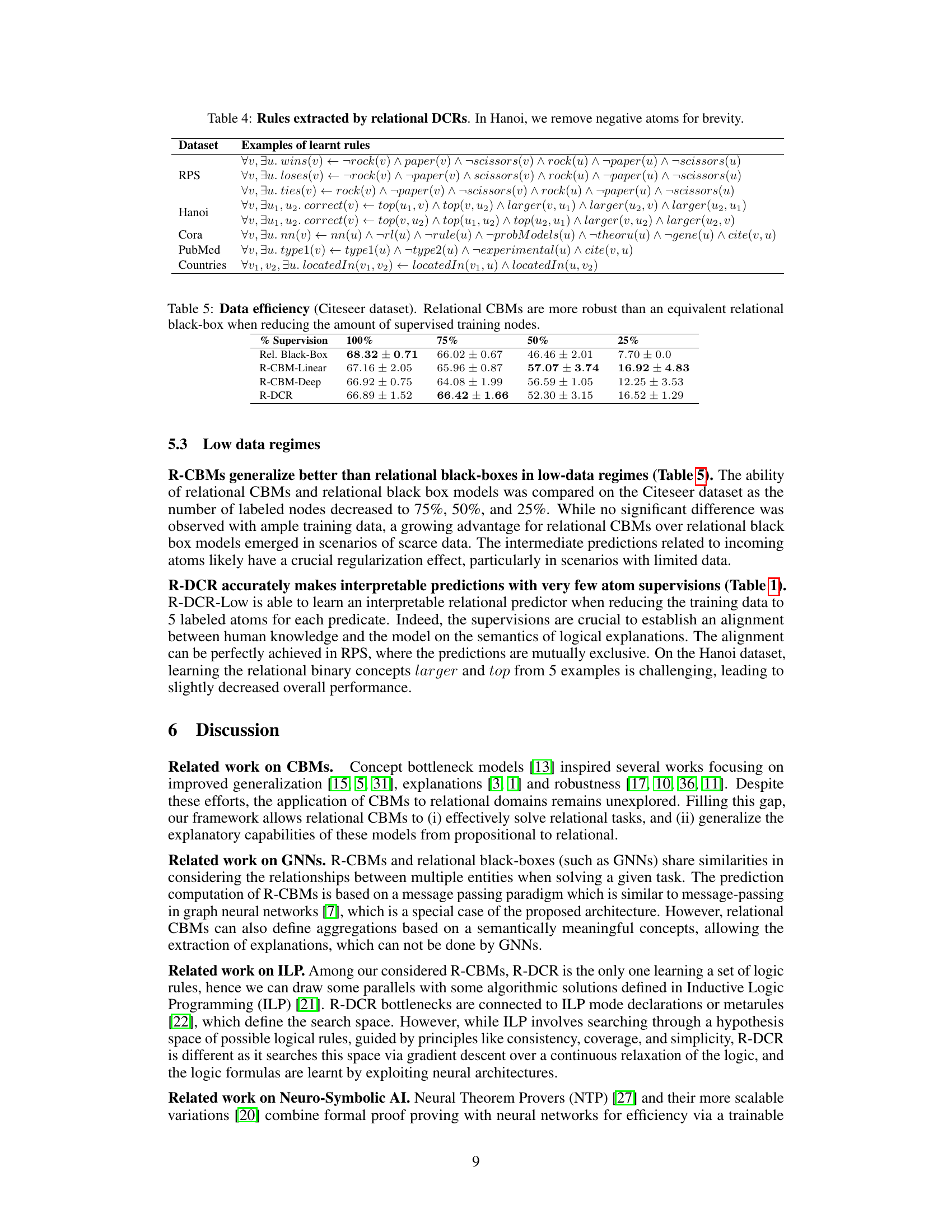

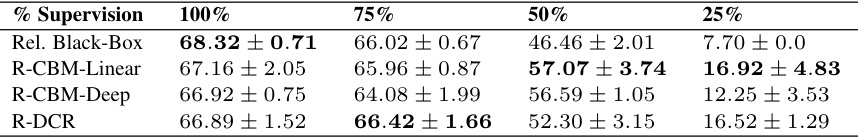

🔼 This table presents the results of an experiment evaluating the performance of relational CBMs and relational black-box models on the Citeseer dataset with varying amounts of supervised training data (100%, 75%, 50%, and 25%). The goal was to assess the robustness of each model type under data scarcity conditions. The table shows that relational CBMs, particularly R-DCR, maintain relatively high accuracy even when the amount of supervised training data is significantly reduced. This contrasts with the relational black-box model, which exhibits a much sharper decline in performance as the amount of supervision decreases.

read the caption

Table 5: Data efficiency (Citeseer dataset). Relational CBMs are more robust than an equivalent relational black-box when reducing the amount of supervised training nodes.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of various models (including R-CBMs and baselines) on several relational tasks (RPS, Hanoi, Cora, Citeseer, PubMed, Countries S1, Countries S2). The metrics used for evaluation vary depending on the task type (ROC-AUC for RPS and Hanoi; accuracy for Cora, Citeseer, PubMed; MRR for Countries S1 and S2). The table highlights the superior generalization capabilities of R-CBMs compared to standard CBMs and other relational black-box methods, demonstrating their effectiveness even in scenarios with out-of-distribution data and limited training time.

read the caption

Table 1: Models' performance on task generalization. R-CBMs generalize well in relational tasks. A indicates methods that cannot be applied due to the dataset structure. OOT indicates out-of-time training due to large domains.

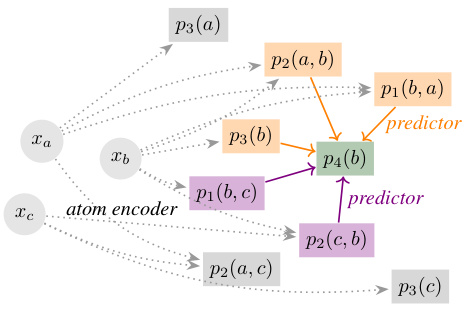

🔼 This table presents the completeness scores for various concept-based models compared to a relational black-box baseline. Completeness score is a metric evaluating how well a model captures the underlying concepts. Higher scores indicate better concept coverage. The table shows the scores for different datasets (RPS, Hanoi, Cora, Citeseer, PubMed, Countries S1, Countries S2) and different models (CBM-Linear, CBM-Deep, DCR, R-CBM Linear, R-CBM Deep, R-DCR). It helps to assess the effectiveness of different model architectures in representing and utilizing concepts for prediction tasks.

read the caption

Table 7: Completeness scores of each concept-based model wrt the relational black-box baseline.

Full paper#