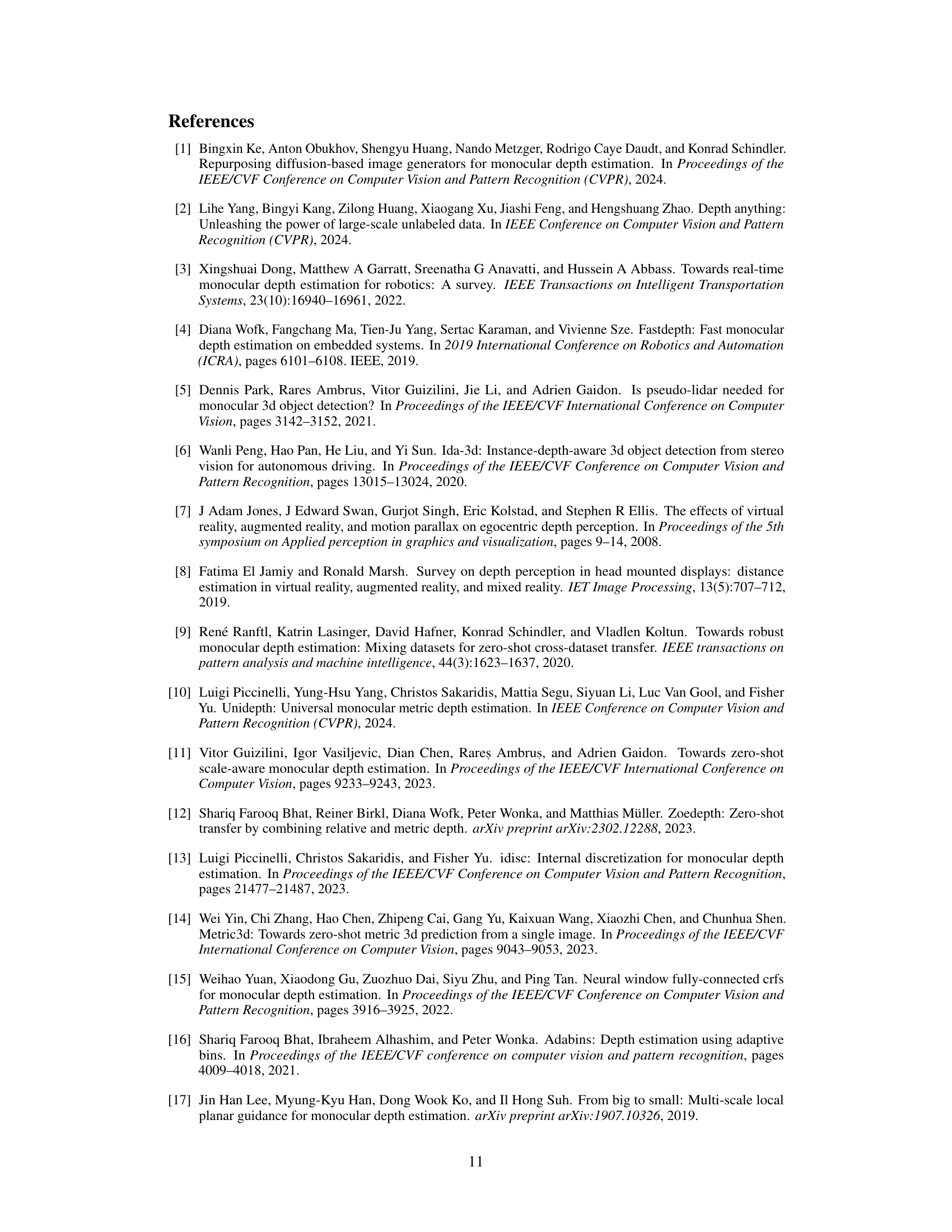

TL;DR#

Monocular metric depth estimation (MMDE) is crucial for 3D scene understanding from images, but existing methods struggle with generalizing to unseen scenes due to reliance on scene-specific scale priors learned during training. This scene dependency limits their practical applicability and requires extensive labeled data for training. The problem is further complicated by the scale ambiguity inherent in monocular relative depth estimation (MRDE), a related task that estimates relative depths.

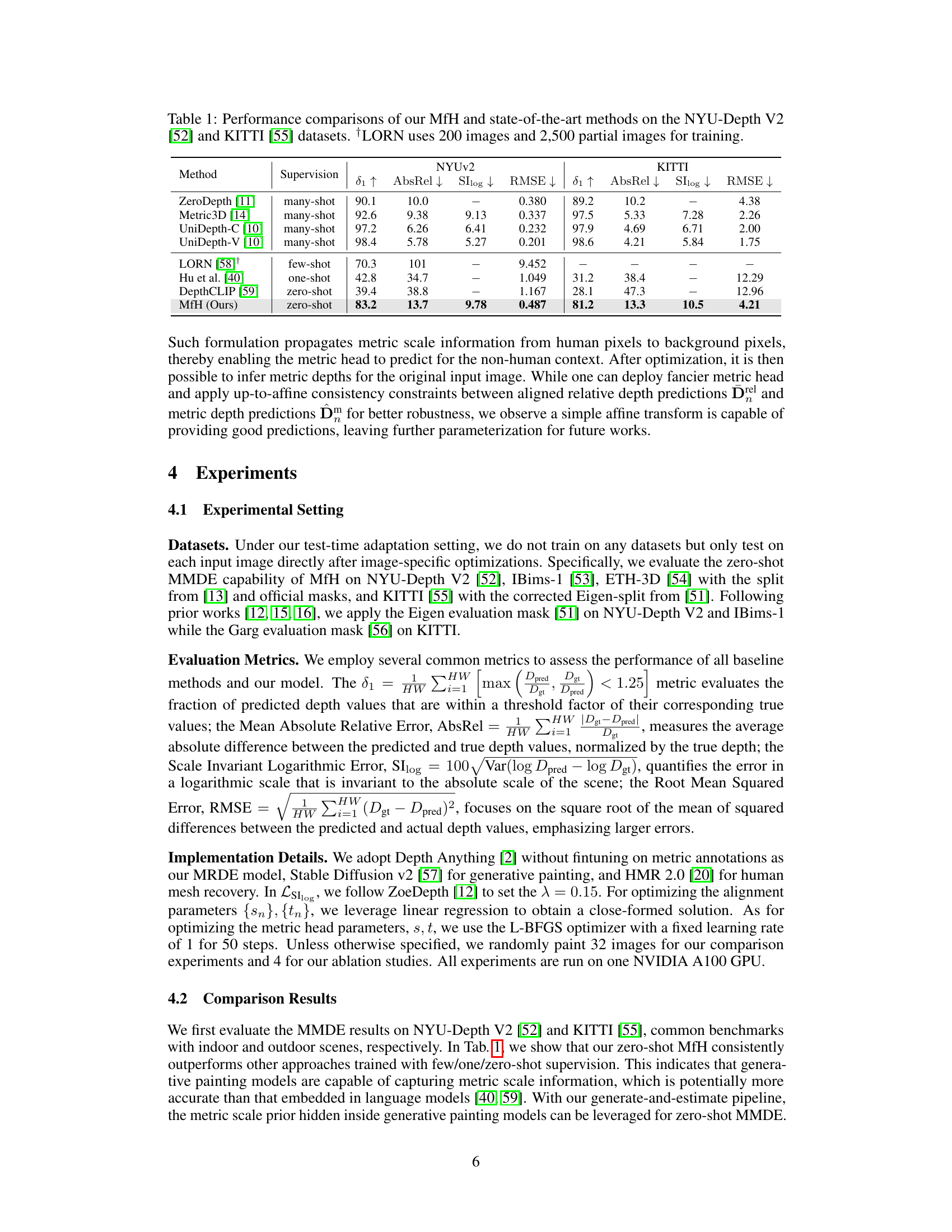

To tackle these issues, the paper introduces Metric from Human (MfH). MfH cleverly uses humans as universal landmarks, leveraging generative painting models to generate humans within the input image. It then employs human mesh recovery (HMR) to extract human dimensions, which are used to estimate a scene-independent metric scale prior. This approach bridges generalizable MRDE to zero-shot MMDE without requiring any metric depth annotation during training. Experimental results show that MfH significantly outperforms other MMDE methods in zero-shot settings, demonstrating its superior generalization ability and highlighting the potential of integrating generative models and human priors for robust depth estimation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to zero-shot monocular metric depth estimation, a challenging problem in computer vision. It offers a solution that avoids scene-dependent training, leading to better generalization and improved performance on unseen data. This opens avenues for research on test-time adaptation and the integration of generative models into computer vision tasks.

Visual Insights#

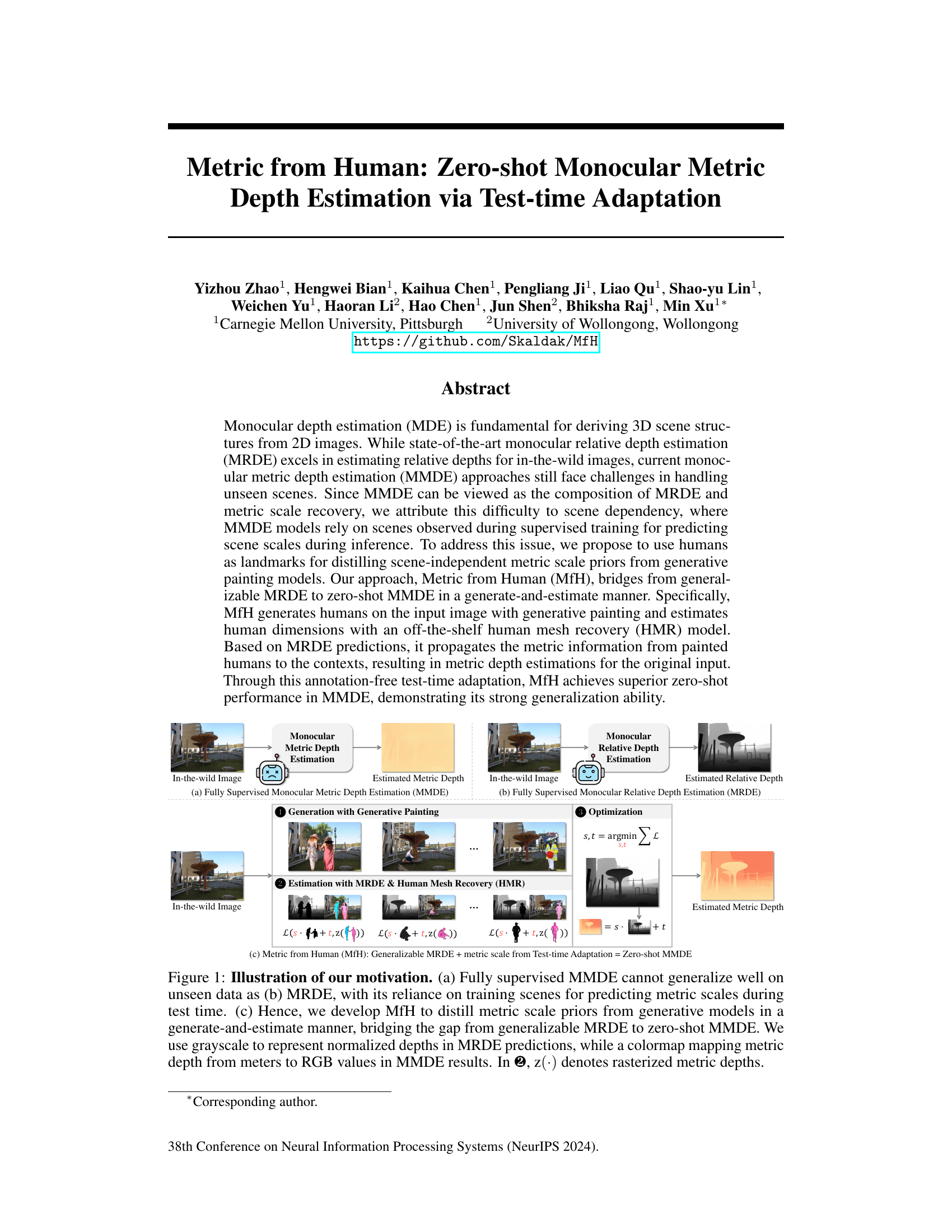

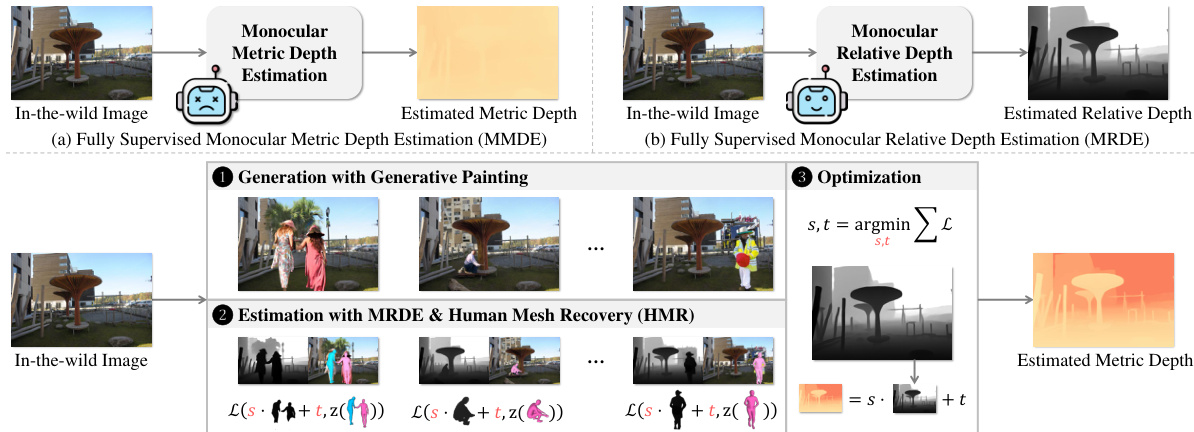

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the Metric from Human (MfH) method. It compares three approaches: (a) Traditional fully supervised monocular metric depth estimation (MMDE), which struggles to generalize to unseen scenes due to its reliance on training data. (b) Fully supervised monocular relative depth estimation (MRDE), which excels at estimating relative depths and generalizes well but lacks absolute depth information. (c) The proposed MfH method, which leverages human mesh recovery and generative painting to distill metric scale information at test time. This allows MfH to bridge the gap between the generalizability of MRDE and the accuracy of MMDE, achieving strong zero-shot performance.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our motivation. (a) Fully supervised MMDE cannot generalize well on unseen data as (b) MRDE, with its reliance on training scenes for predicting metric scales during test time. (c) Hence, we develop MfH to distill metric scale priors from generative models in a generate-and-estimate manner, bridging the gap from generalizable MRDE to zero-shot MMDE. We use grayscale to represent normalized depths in MRDE predictions, while a colormap mapping metric depth from meters to RGB values in MMDE results. In �, z(·) denotes rasterized metric depths.

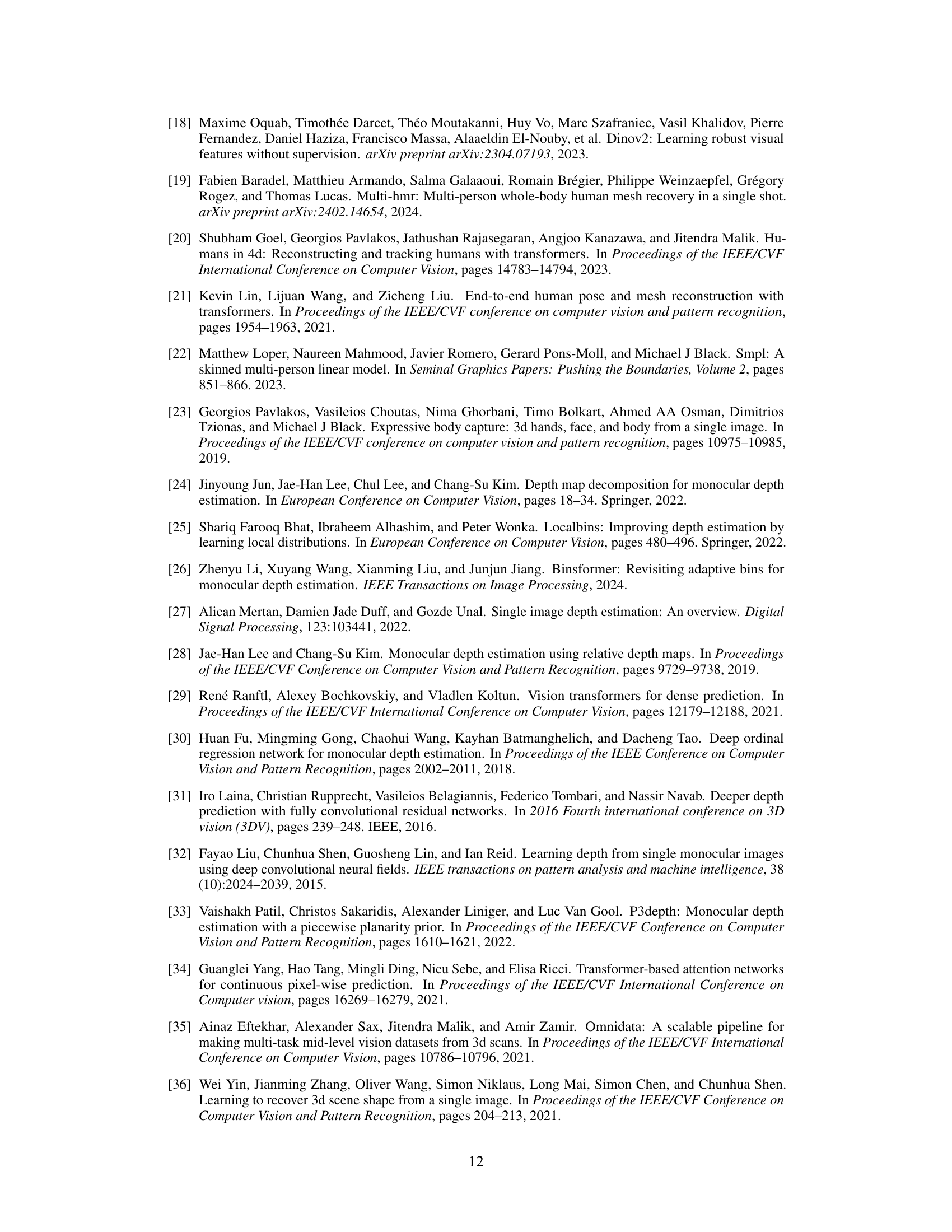

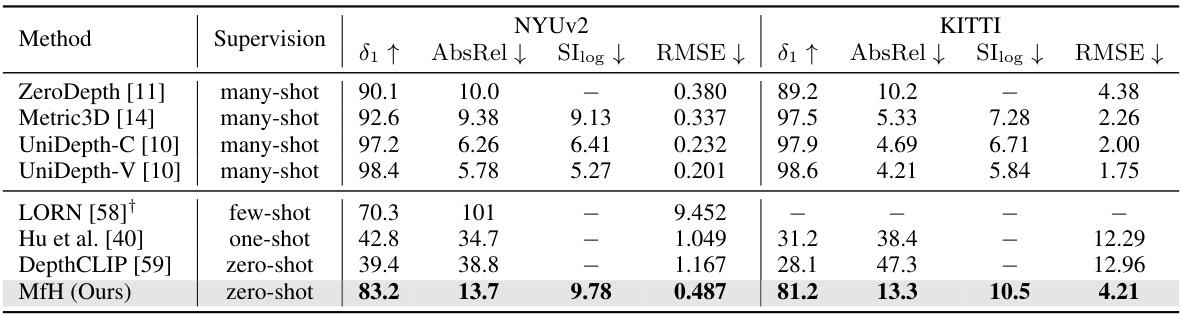

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed method (MfH) against several state-of-the-art methods on two benchmark datasets for monocular depth estimation: NYU-Depth V2 and KITTI. The comparison includes metrics such as 81, AbsRel, SIlog, and RMSE, highlighting the zero-shot capability of MfH against methods trained with varying amounts of data (many-shot, few-shot, one-shot). The table shows that MfH achieves competitive results even without any training data for metric depth.

read the caption

Table 1: Performance comparisons of our MfH and state-of-the-art methods on the NYU-Depth V2 [52] and KITTI [55] datasets. †LORN uses 200 images and 2,500 partial images for training.

In-depth insights#

Zero-Shot MMDE#

Zero-shot monocular metric depth estimation (MMDE) tackles a significant challenge in computer vision: accurately estimating depth from a single image without relying on training data specific to the scene. Existing MMDE methods typically struggle with unseen scenes, requiring extensive fine-tuning for each new environment. Zero-shot MMDE aims to overcome this limitation by leveraging generalizable knowledge. This could involve using scene-independent metric scale priors, perhaps derived from generative models or inherent object properties (like the consistent size of humans). A promising approach is to use humans as reliable scale references, painting them into the image using generative methods and then leveraging human mesh recovery models to estimate their dimensions. This provides a known scale from which to infer the metric scale of the entire scene. Success hinges on the accuracy of both the generative painting and human mesh recovery processes. In essence, zero-shot MMDE seeks to make MMDE more robust and widely applicable by circumventing the need for scene-specific training data, instead relying on transferring information from generalizable sources.

Human-Based Priors#

The concept of “Human-Based Priors” in a research paper suggests leveraging human knowledge or perception to inform or improve a machine learning model’s performance. This approach is particularly useful when dealing with tasks where obtaining large amounts of labeled data is difficult or expensive. By incorporating human-centric data, such as human body dimensions or scene understanding, the model can learn more robust and generalizable representations. For instance, using humans as landmarks to infer metric scale in monocular depth estimation circumvents the need for scene-specific training data and improves zero-shot generalization. This strategy exploits humans’ inherent understanding of scale and proportions, translating it into a prior that guides the model’s predictions. A key consideration is the method of integrating human priors; carefully designed techniques are necessary to ensure that human input does not introduce biases or limitations into the model. The effectiveness of human-based priors depends on the quality and relevance of human input, the way it’s integrated with model parameters, and the overall model architecture. Therefore, a thorough analysis of potential biases and limitations is crucial to assess the validity and robustness of the proposed approach.

Generative Painting#

Generative painting, within the context of this research, is a crucial technique for creating synthetic human figures within real-world images. This process is not about creating photorealistic images but rather about generating plausible human forms that provide consistent and measurable metric information. The key is that these painted humans act as reliable landmarks, providing consistent scale across diverse scenes. By utilizing generative painting, the model avoids the limitations of scene-dependent learning common in monocular metric depth estimation methods. This makes the process robust to variations in background and scene context. The choice of generative painting model is important, as the ability to render humans with accurate proportions and plausible size relative to the environment directly impacts the accuracy of the derived metric scale. The generated images are then used with a human mesh recovery model to extract precise metric dimensions, thus providing the necessary metric scale information to translate relative depth estimations into absolute metric depths. This process is completely annotation-free, happening at test time, making it a highly effective zero-shot method for monocular metric depth estimation.

Test-Time Adaptation#

Test-time adaptation, as a crucial concept, modifies a pre-trained model’s behavior without additional training. It’s particularly valuable for situations with limited data or when adapting to new domains is necessary. The core idea is to leverage existing model parameters and tune them based on new inputs, effectively personalizing the model’s response for specific tasks. This approach has many advantages, especially in scenarios with limited data where retraining the whole model is not feasible or when there is a need to customize the model’s response to particular inputs. However, challenges remain in ensuring the method’s robustness and generalizability across diverse inputs. Careful design and validation are essential to overcome these limitations. Future work should explore more sophisticated methods for adapting models at test time, incorporating techniques such as meta-learning and transfer learning.

MMDE Generalization#

Monocular metric depth estimation (MMDE) models struggle with generalization to unseen scenes, a problem not as prevalent in relative depth estimation. This limitation stems from MMDE’s reliance on scene-specific scale priors learned during training. These models essentially memorize relationships between training scenes and their corresponding scales, failing when presented with novel scenes. Addressing this requires moving beyond scene-dependent supervised learning and instead leveraging scene-independent scale priors. This could involve incorporating universal landmarks (e.g., humans) whose dimensions offer consistent scale information regardless of the scene’s context, thereby creating zero-shot or few-shot MMDE methods with improved generalization. Generative models offer a promising avenue for extracting scene-independent scale priors by generating consistent objects and estimating their sizes to provide metric information in a test-time adaptation scheme. The success of this approach hinges on the generalizability of the generative model and the robustness of the method for estimating the object’s size.

More visual insights#

More on figures

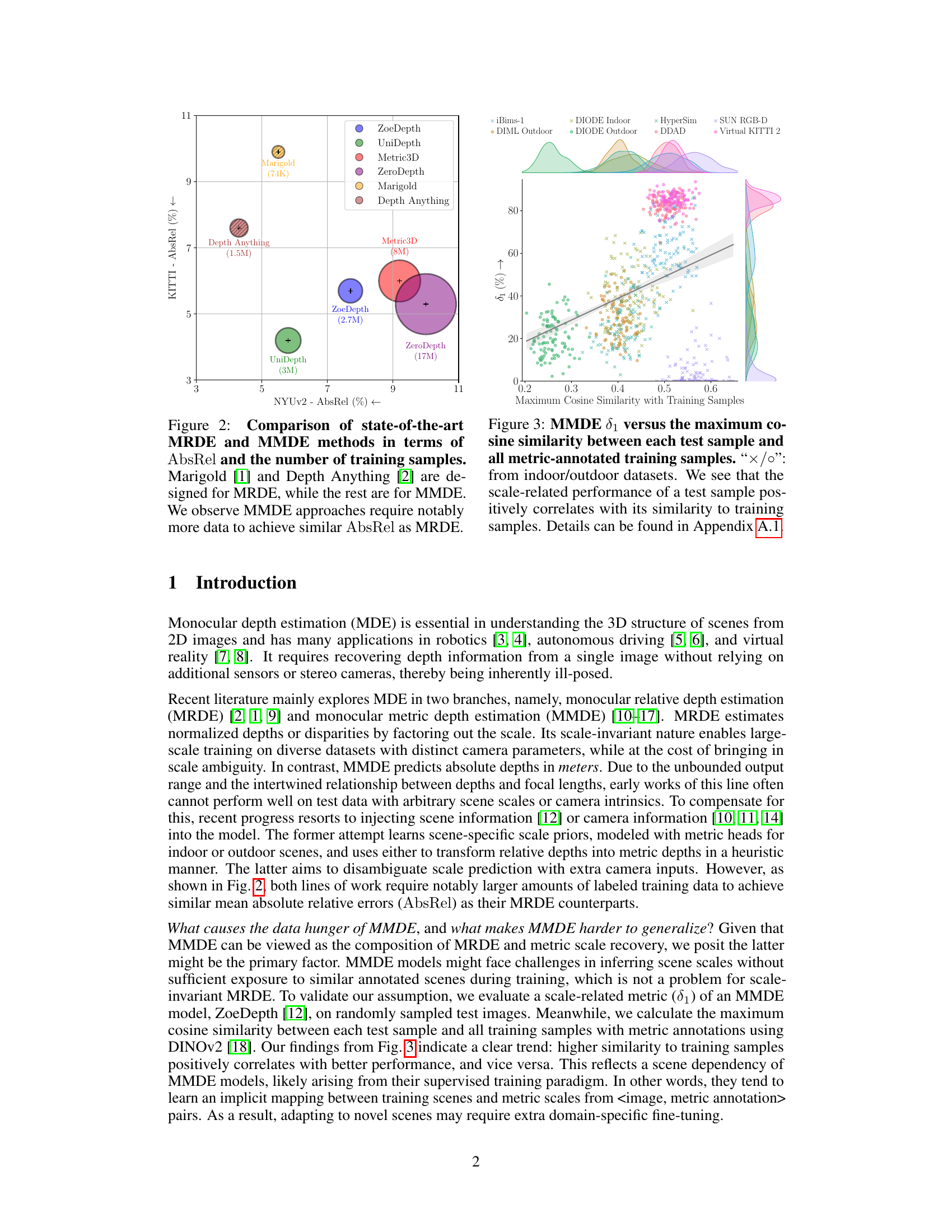

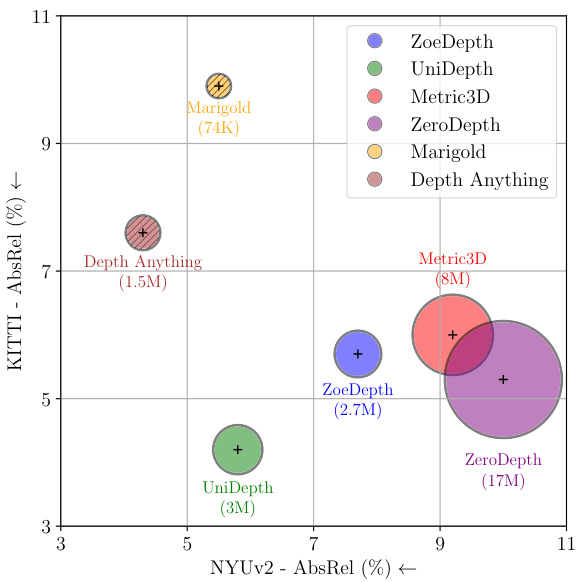

🔼 This figure compares the performance of various monocular depth estimation (MDE) methods. It highlights the difference between monocular relative depth estimation (MRDE) and monocular metric depth estimation (MMDE) approaches. The x-axis represents the Absolute Relative Error (AbsRel) on the NYU-v2 dataset, while the y-axis represents the AbsRel on the KITTI dataset. Each point represents a different MDE method, and the size of the point indicates the amount of training data used for that method. The figure clearly shows that MMDE methods require significantly more training data than MRDE methods to achieve comparable performance. This finding supports the paper’s argument that the scene dependency inherent in MMDE models makes them more data-hungry and harder to generalize.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of state-of-the-art MRDE and MMDE methods in terms of AbsRel and the number of training samples. Marigold [1] and Depth Anything [2] are designed for MRDE, while the rest are for MMDE. We observe MMDE approaches require notably more data to achieve similar AbsRel as MRDE.

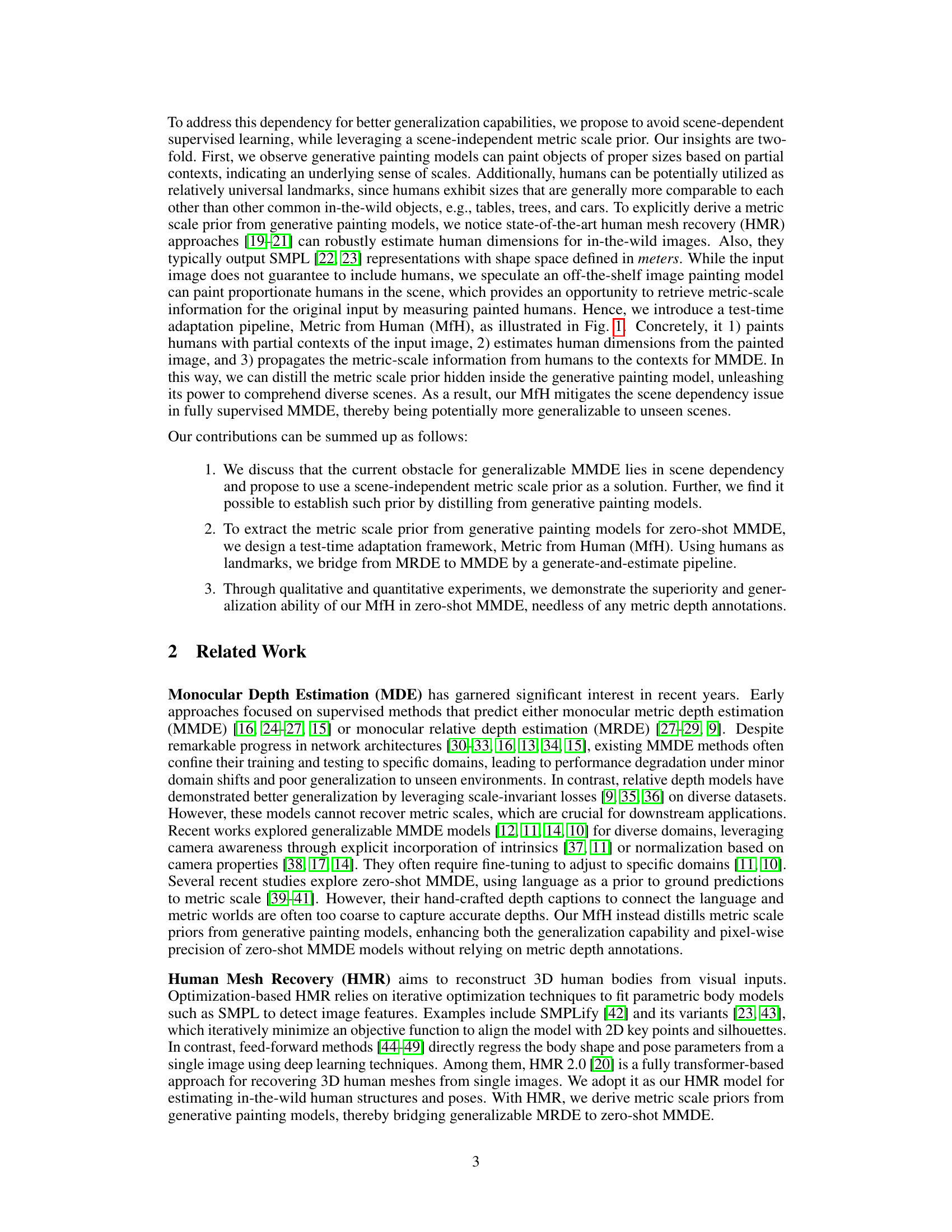

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between the performance of a monocular metric depth estimation (MMDE) model (measured by the scale-invariant metric δ₁) and the similarity of each test sample to the training samples. The x-axis represents the maximum cosine similarity between a test sample and all training samples with metric annotations. The y-axis represents the δ₁ metric for each test sample. The plot demonstrates a positive correlation, indicating that MMDE models perform better on test samples that are more similar to the training data. This supports the claim of scene dependency for MMDE methods, as discussed in the paper.

read the caption

Figure 3: MMDE 81 versus the maximum cosine similarity between each test sample and all metric-annotated training samples. '×/o': from indoor/outdoor datasets. We see that the scale-related performance of a test sample positively correlates with its similarity to training samples. Details can be found in Appendix A.1.

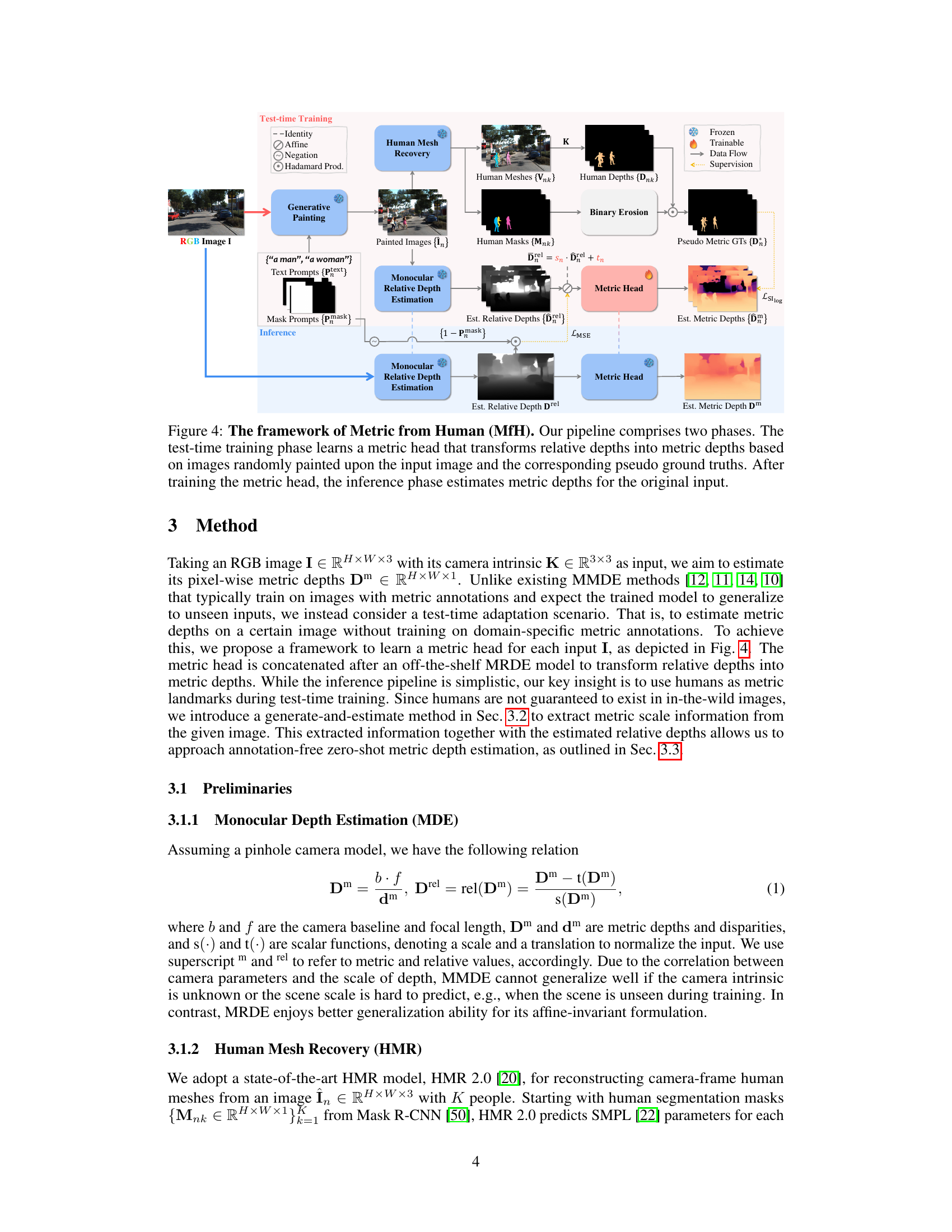

🔼 The figure illustrates the Metric from Human (MfH) framework, which consists of two main phases: test-time training and inference. In the test-time training phase, the input image is processed using generative painting to create multiple versions with randomly placed humans. Human Mesh Recovery (HMR) is then used to estimate the depth of these painted humans. These human depths, along with relative depth estimations from a Monocular Relative Depth Estimation (MRDE) model, are used to train a metric head. The metric head learns to transform relative depths into metric depths. In the inference phase, the original input image is processed by the MRDE model to obtain relative depths, which are then fed into the trained metric head to produce final metric depth estimations.

read the caption

Figure 4: The framework of Metric from Human (MfH). Our pipeline comprises two phases. The test-time training phase learns a metric head that transforms relative depths into metric depths based on images randomly painted upon the input image and the corresponding pseudo ground truths. After training the metric head, the inference phase estimates metric depths for the original input.

🔼 This figure illustrates the pipeline of Metric from Human (MfH), which consists of two main phases: test-time training and inference. In the test-time training phase, the model learns a metric head to transform relative depth maps into metric depth maps. This training uses pseudo ground truth metric depth maps generated from randomly painted versions of the input image, where humans are added as metric landmarks. The inference phase then uses the learned metric head to process the original image and produce the final metric depth map.

read the caption

Figure 4: The framework of Metric from Human (MfH). Our pipeline comprises two phases. The test-time training phase learns a metric head that transforms relative depths into metric depths based on images randomly painted upon the input image and the corresponding pseudo ground truths. After training the metric head, the inference phase estimates metric depths for the original input.

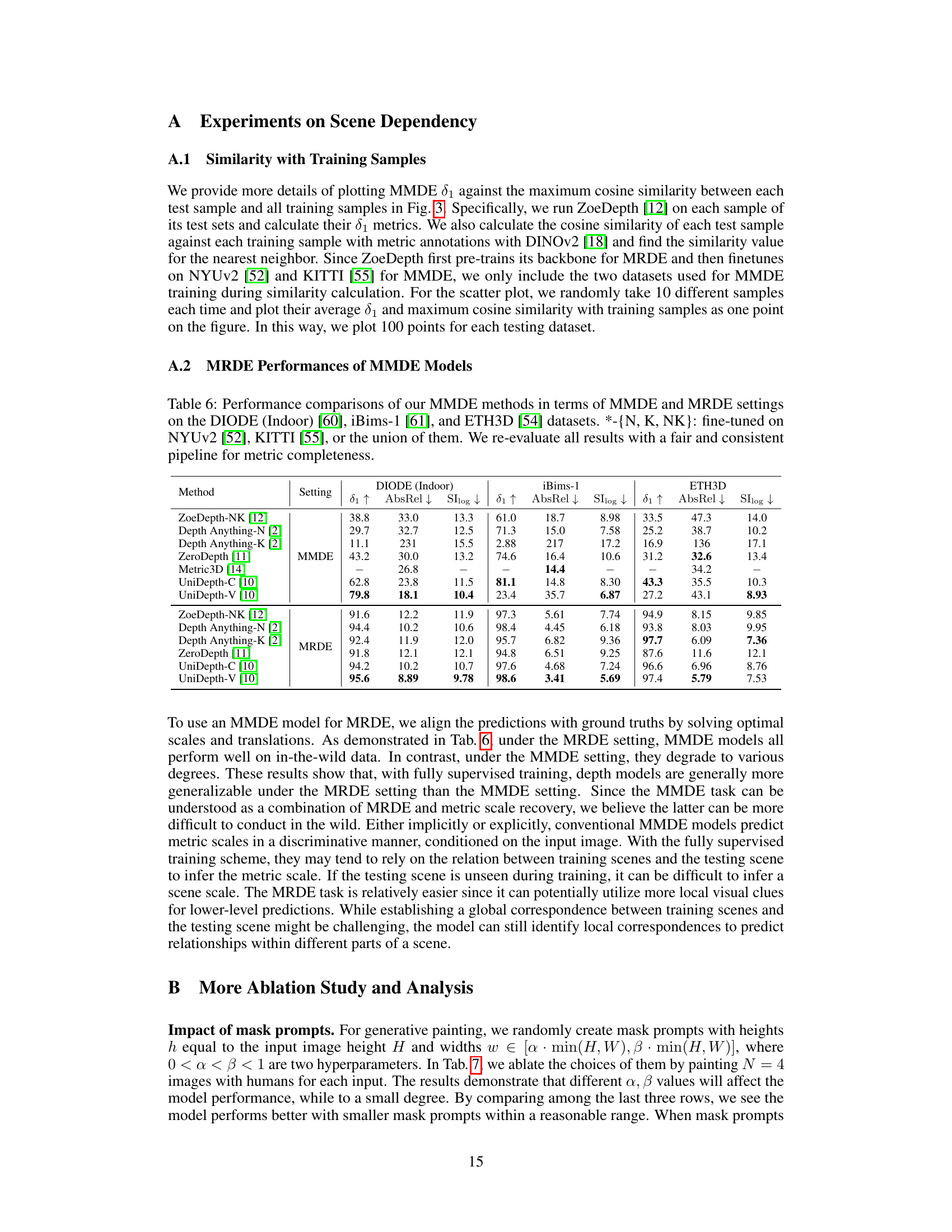

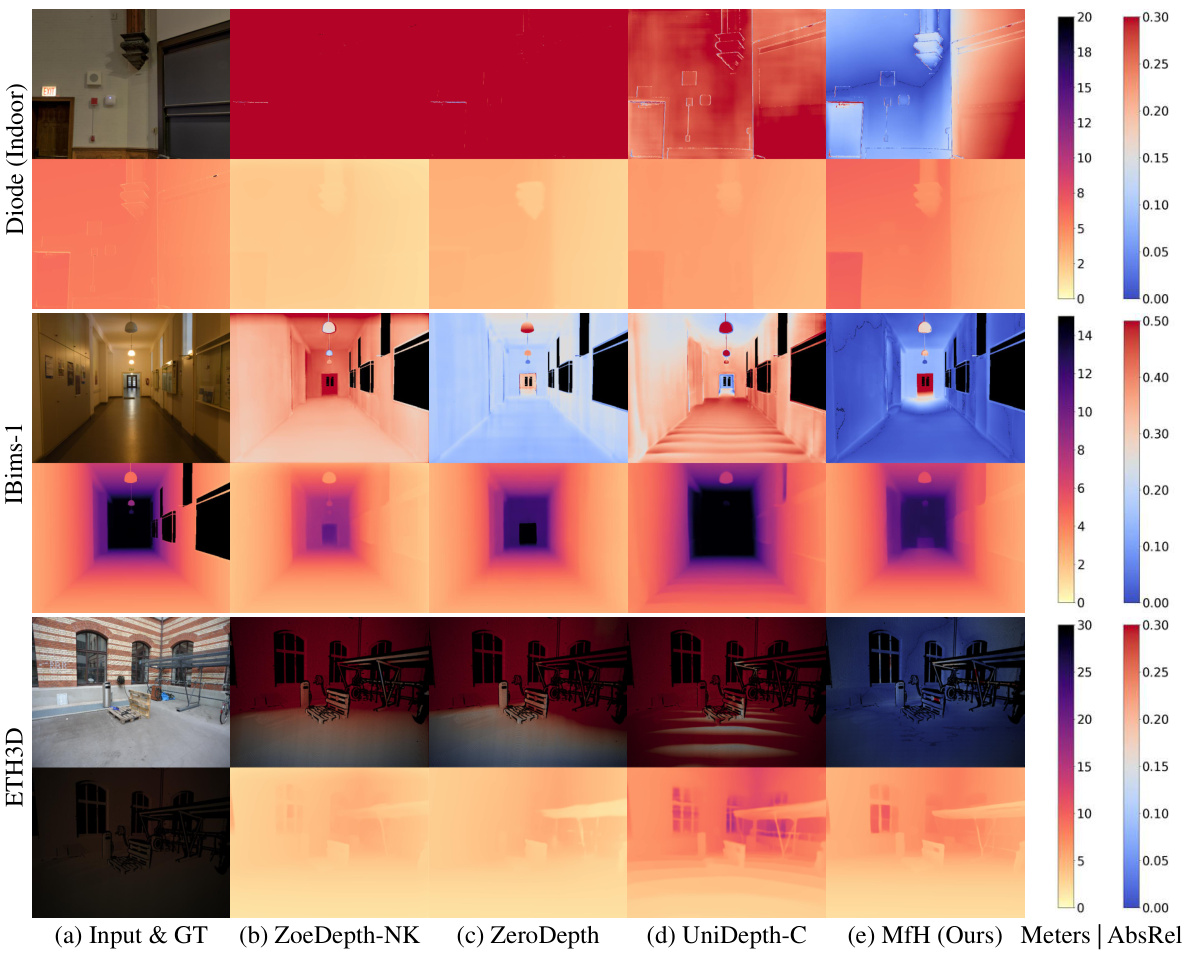

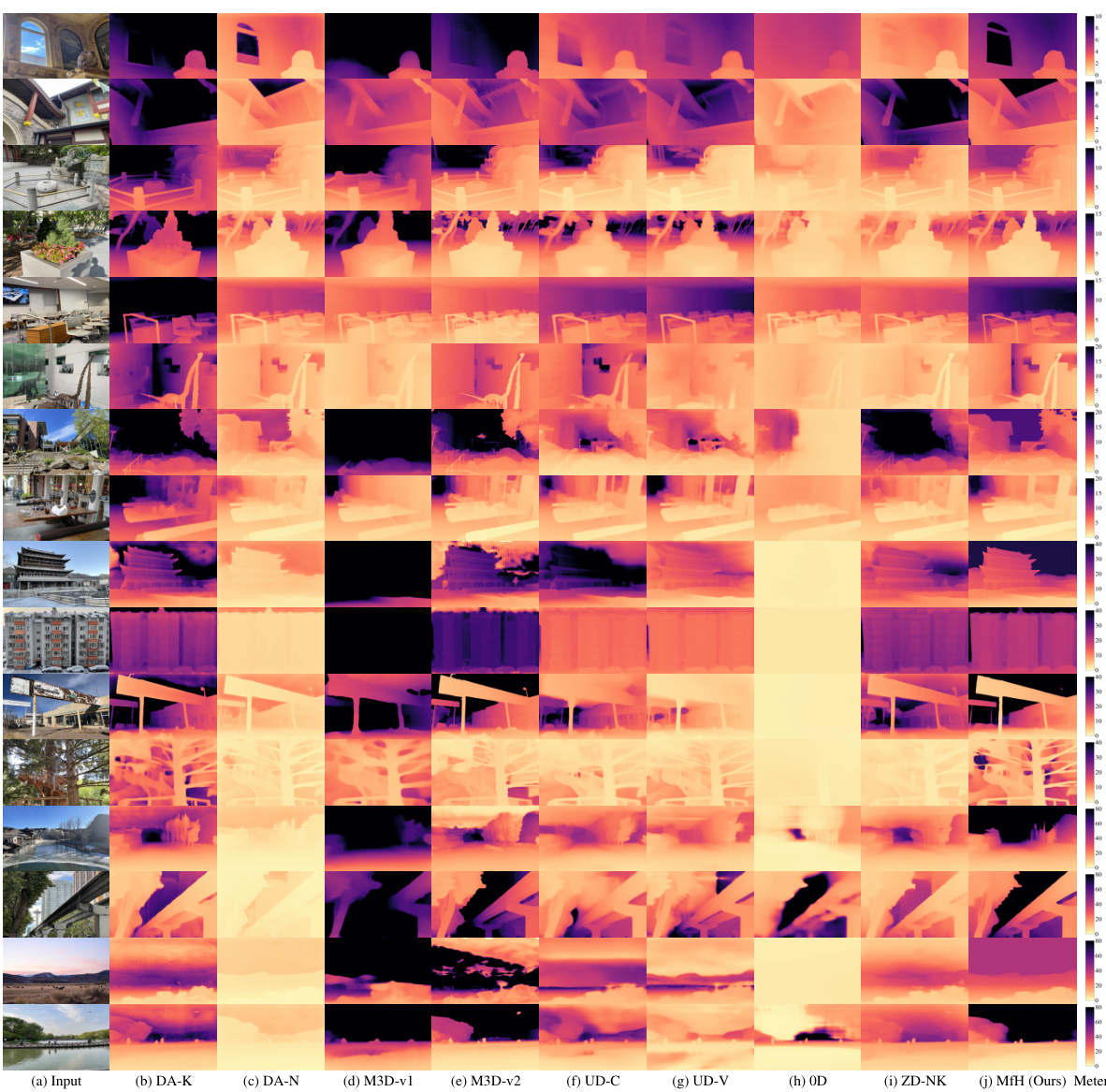

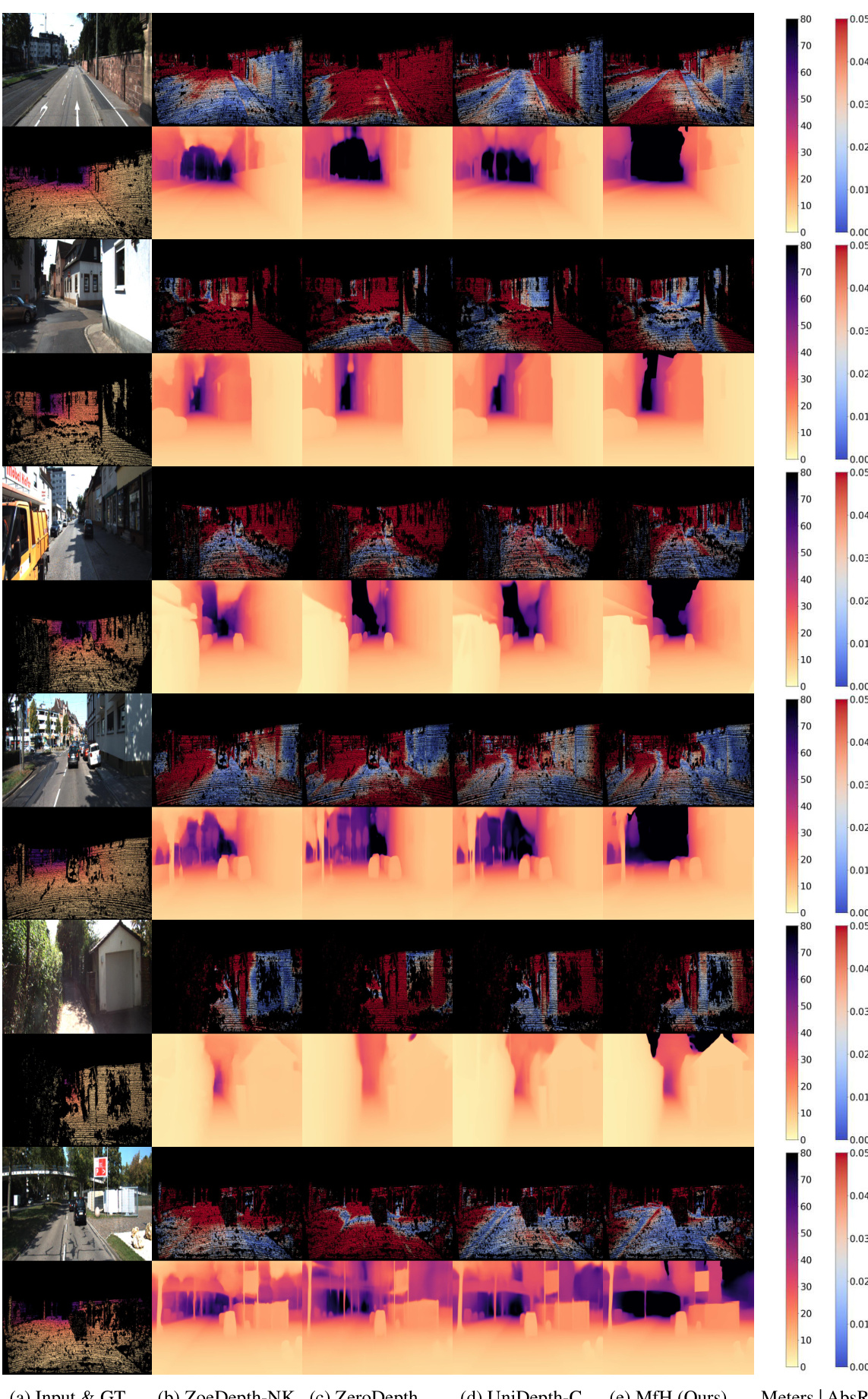

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison of the proposed MfH method against other state-of-the-art methods for monocular metric depth estimation on several datasets (ETH3D, IBims-1, and DIODE (Indoor)). Each pair of rows shows a test image and its corresponding ground truth (GT) depth map, along with the predicted depth maps from ZoeDepth-NK, ZeroDepth, UniDepth-C, and MfH. The absolute relative error (AbsRel) is also displayed for each method, enabling a visual comparison of depth estimation accuracy.

read the caption

Figure 7: Zero-shot qualitative results. Each pair of consecutive rows corresponds to one test sample. Each odd row shows an input RGB image alongside the absolute relative error map, while each even row shows the ground truth metric depth and predicted metric depths.

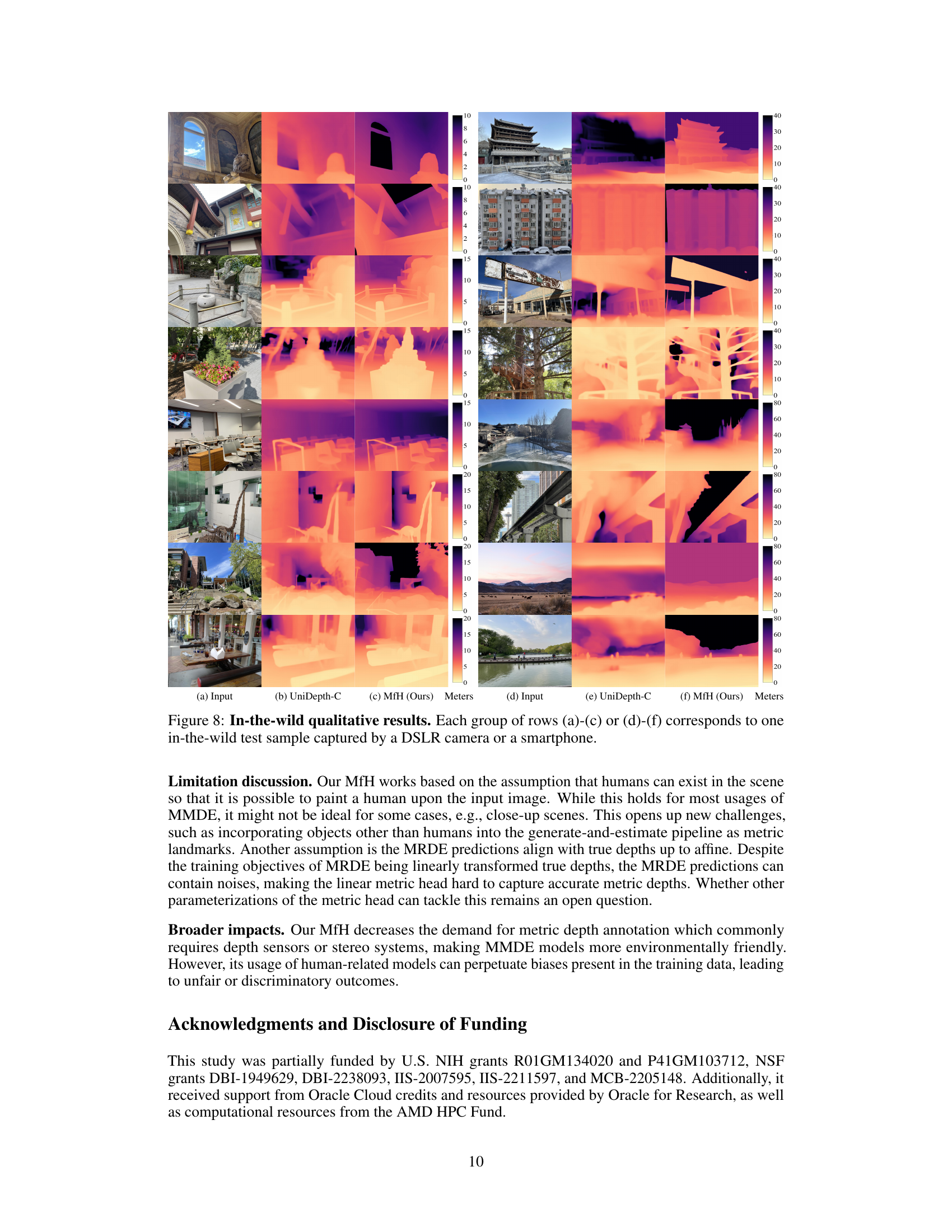

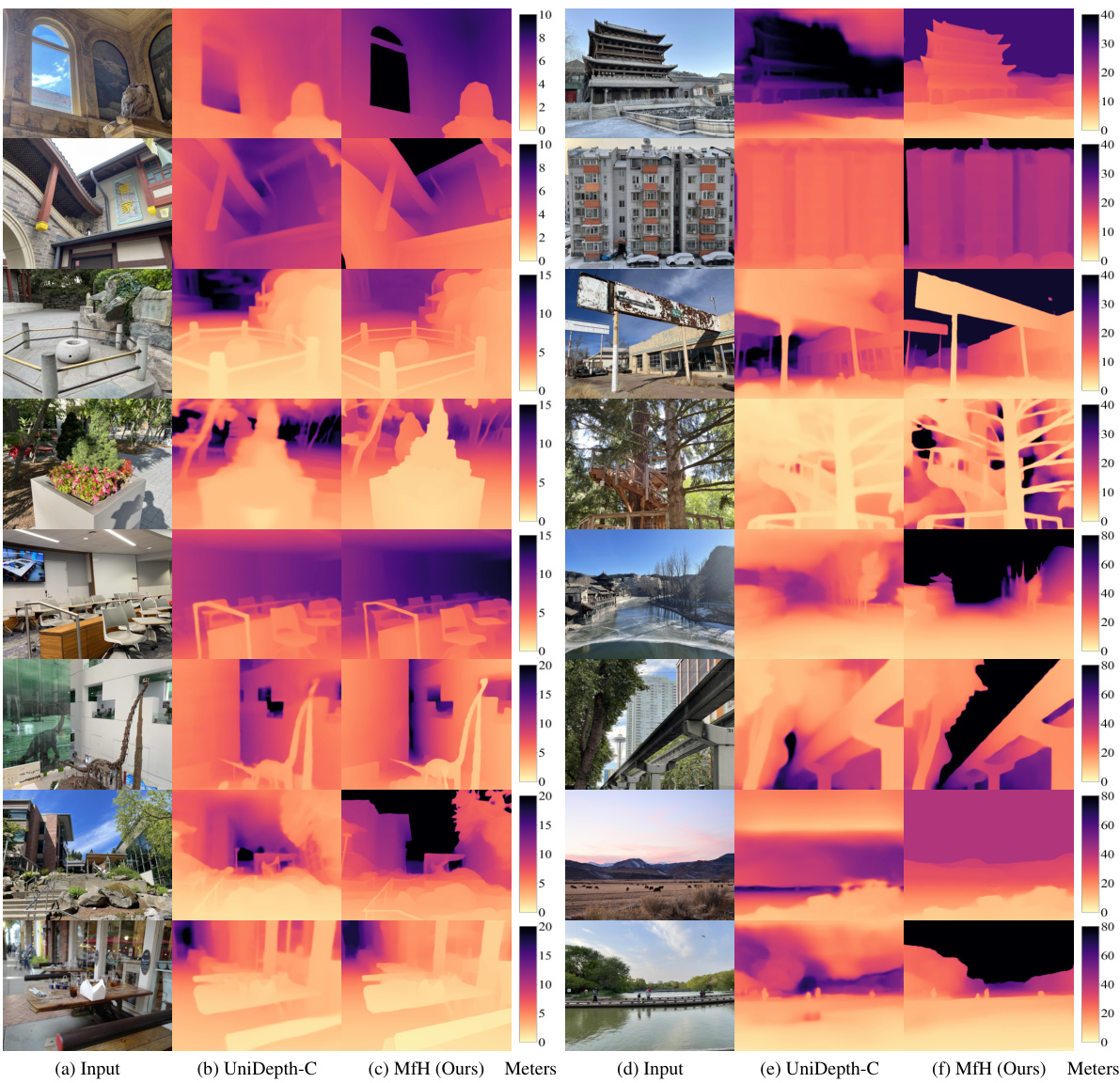

🔼 This figure shows qualitative results of the proposed MfH method and UniDepth-C on in-the-wild images captured by DSLR cameras or smartphones. Each row shows an input image along with its depth estimations from both methods. The colormaps represent the depth values in meters, making it easy to compare the performance visually. This qualitative evaluation shows the generalization ability of MfH, its ability to estimate depth on images outside the training distribution. It highlights the difference in the outputs between the two methods.

read the caption

Figure 8: In-the-wild qualitative results. Each group of rows (a)-(c) or (d)-(f) corresponds to one in-the-wild test sample captured by a DSLR camera or a smartphone.

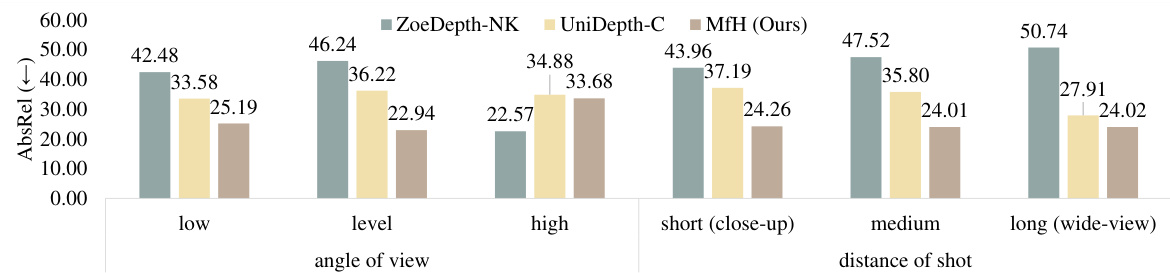

🔼 This figure compares the performance of three different monocular depth estimation methods (ZoeDepth-NK, UniDepth-C, and MfH) across various shot types on the ETH3D dataset. The x-axis categorizes shot types based on angle of view (low, level, high) and distance of shot (short, medium, long), while the y-axis represents the average absolute relative error (AbsRel). The bars show that MfH generally outperforms the other methods across most shot types, indicating its robustness and generalizability.

read the caption

Figure 9: AbsRel (↓) comparisons for different types of shots on the ETH3D dataset.

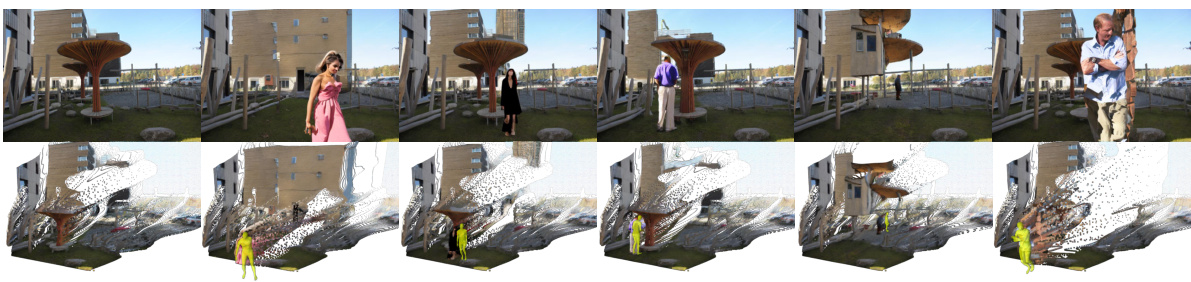

🔼 This figure illustrates examples of successful and unsuccessful applications of the Metric from Human (MfH) method during the pseudo ground truth generation phase. The top three rows showcase failure cases, highlighting instances where the generative painting model produces unrealistic or inaccurate human depictions (e.g., non-human objects with human features, disproportionate humans, overlapping human meshes). The bottom three rows present success cases, demonstrating realistic human representations and accurate scale relationships between humans and the scene, leading to reliable pseudo ground truths for training the metric depth estimation model.

read the caption

Figure 10: Success cases and failure cases of MfH during the process of pseudo ground truth generation. The first three rows show failure cases, while the last three rows show success ones.

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison of zero-shot monocular metric depth estimation methods on various test samples. Each pair of rows displays an input RGB image and its corresponding ground truth and estimated metric depths. The absolute relative error map is included to visualize the performance of each method.

read the caption

Figure 7: Zero-shot qualitative results. Each pair of consecutive rows corresponds to one test sample. Each odd row shows an input RGB image alongside the absolute relative error map, while each even row shows the ground truth metric depth and predicted metric depths.

🔼 The figure shows the framework of Metric from Human (MfH), a method for zero-shot monocular metric depth estimation. It consists of two phases: test-time training and inference. During the training phase, a metric head is trained using images generated by applying a generative painting model to the input image. Human meshes are recovered from the painted images using a Human Mesh Recovery model, and pseudo ground truth metric depths are created from them. The metric head transforms relative depths (obtained from a pre-trained monocular relative depth estimation model) into metric depths, trained using the SIlog loss function. In the inference phase, the trained metric head is used to estimate metric depths for the original input image.

read the caption

Figure 4: The framework of Metric from Human (MfH). Our pipeline comprises two phases. The test-time training phase learns a metric head that transforms relative depths into metric depths based on images randomly painted upon the input image and the corresponding pseudo ground truths. After training the metric head, the inference phase estimates metric depths for the original input.

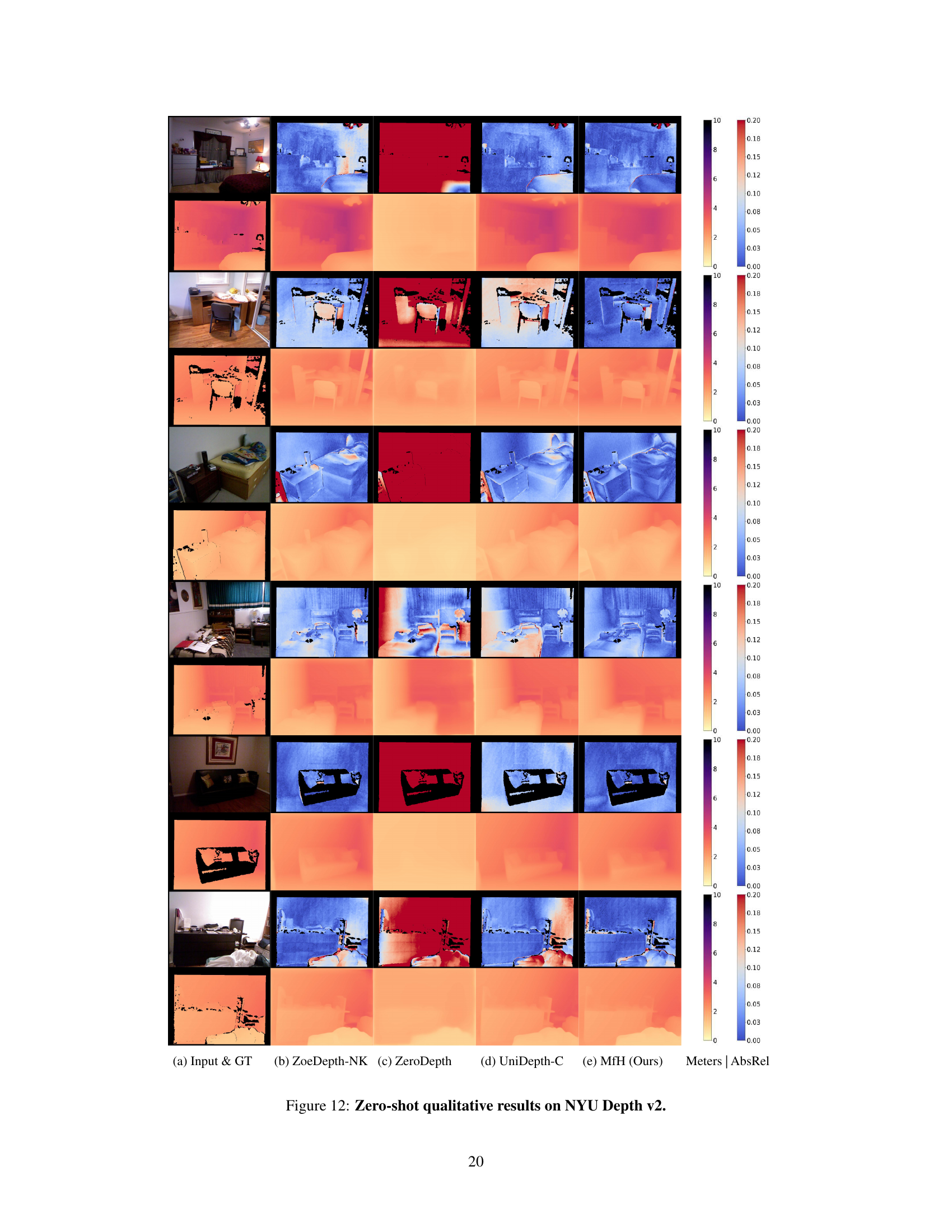

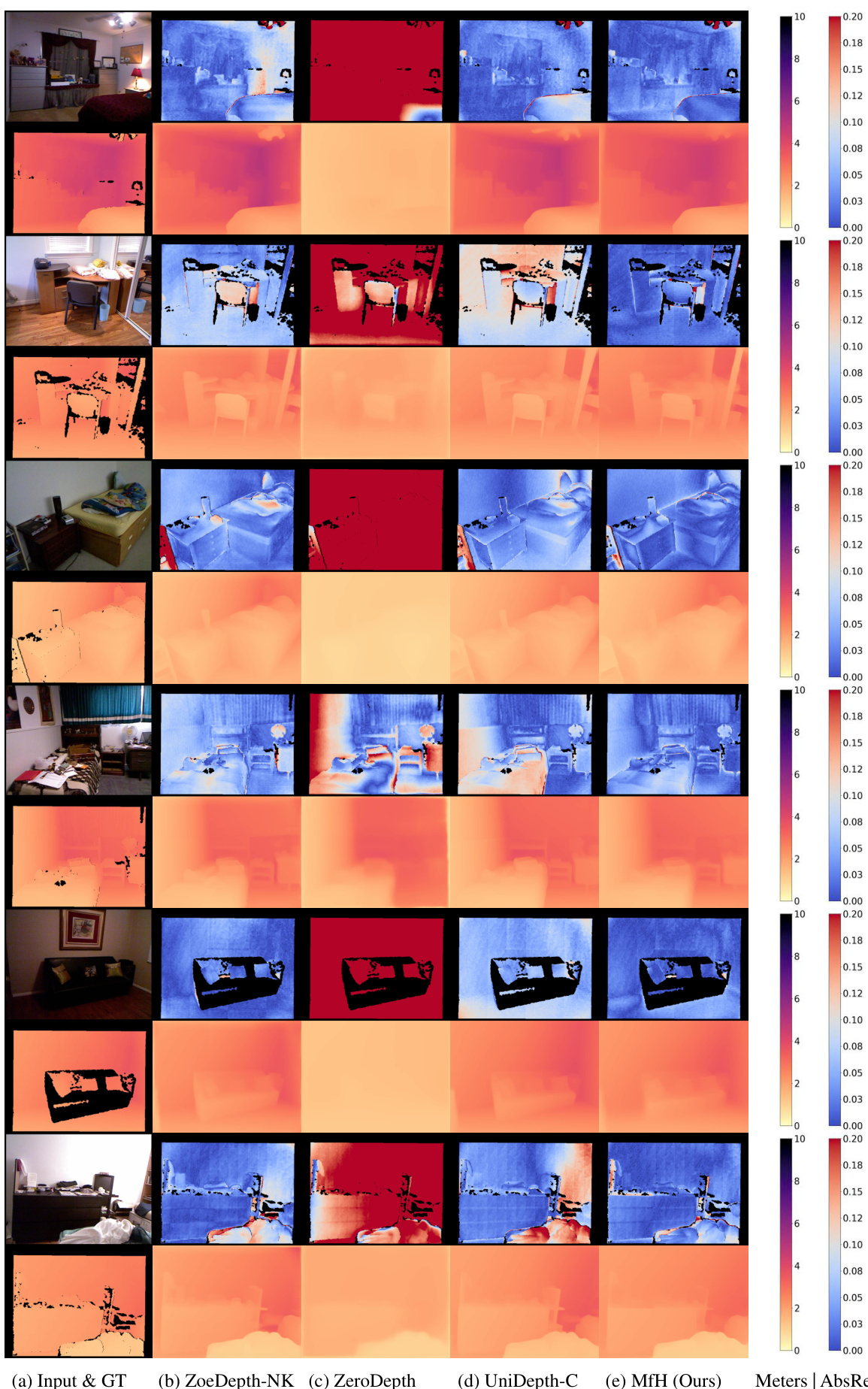

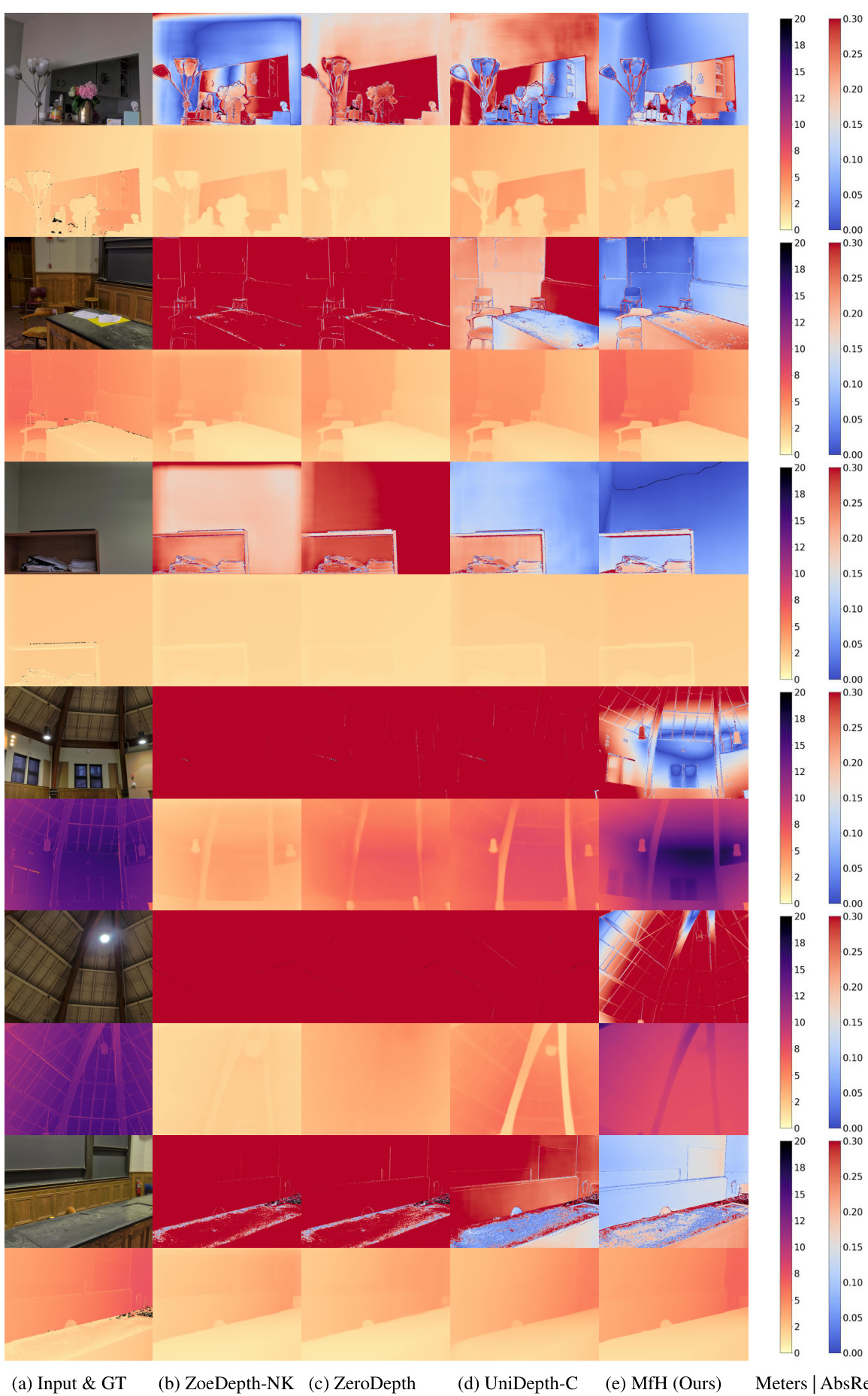

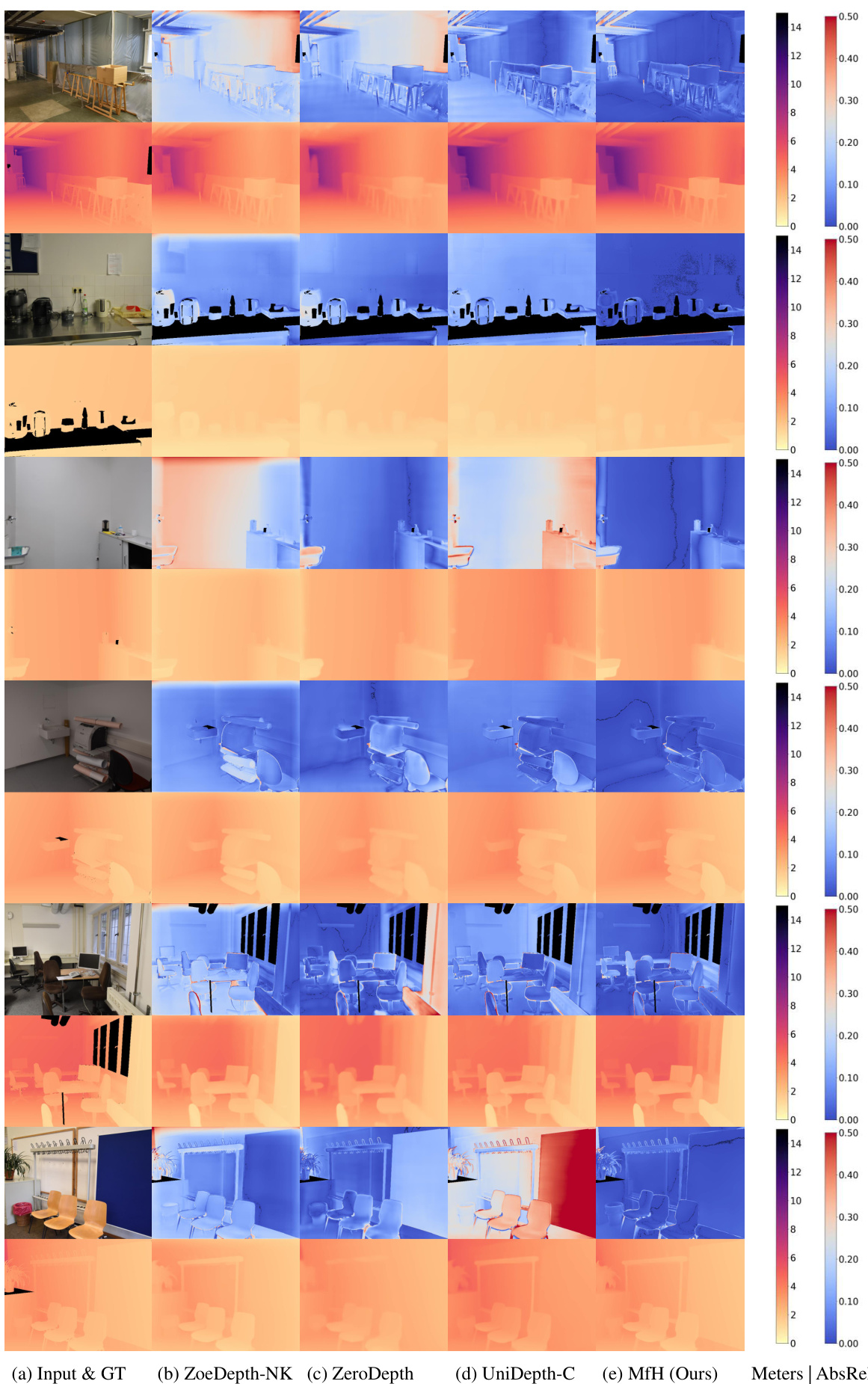

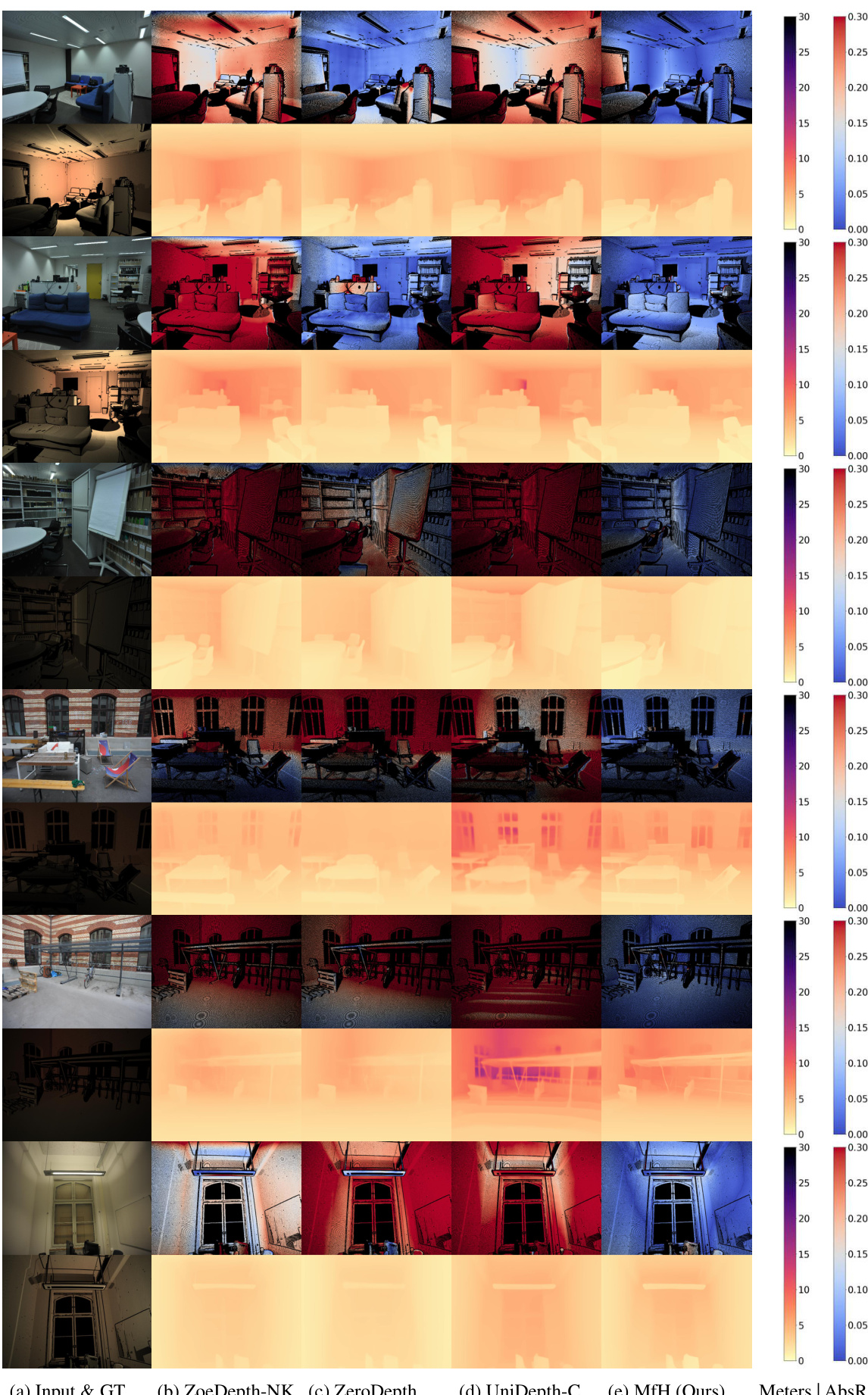

🔼 This figure shows a comparison of zero-shot qualitative results on the NYU Depth V2 dataset. Each row represents a different test image. The first column shows the input image and ground truth depth map, while the subsequent columns display the depth estimations from ZoeDepth-NK, ZeroDepth, UniDepth-C, and the proposed MfH method, respectively. A color bar indicates the mapping of metric depth values to color intensities for better visualization. Each column also includes the absolute relative error (AbsRel) map, illustrating the difference between the predicted depth and ground truth.

read the caption

Figure 12: Zero-shot qualitative results on NYU Depth v2.

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the proposed method, Metric from Human (MfH). It compares three approaches: (a) fully supervised MMDE, which struggles to generalize to unseen scenes; (b) fully supervised MRDE, which excels at estimating relative depths but lacks metric scale information; and (c) the proposed MfH, which leverages generative painting models and human mesh recovery to estimate metric scale priors from humans and transfers this information to the input scene, enabling zero-shot MMDE.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of our motivation. (a) Fully supervised MMDE cannot generalize well on unseen data as (b) MRDE, with its reliance on training scenes for predicting metric scales during test time. (c) Hence, we develop MfH to distill metric scale priors from generative models in a generate-and-estimate manner, bridging the gap from generalizable MRDE to zero-shot MMDE. We use grayscale to represent normalized depths in MRDE predictions, while a colormap mapping metric depth from meters to RGB values in MMDE results. In �, z(·) denotes rasterized metric depths.

🔼 This figure shows a qualitative comparison of the zero-shot monocular metric depth estimation performance of different methods on the NYU Depth V2 dataset. Each row presents a sample image along with the ground truth depth map (GT), results from ZoeDepth-NK, ZeroDepth, UniDepth-C, and MfH (the proposed method). The absolute relative error (AbsRel) is visualized as a colormap for each prediction, providing a visual assessment of the accuracy of each method in predicting metric depth.

read the caption

Figure 12: Zero-shot qualitative results on NYU Depth v2.

🔼 This figure presents a qualitative comparison of zero-shot monocular metric depth estimation results on the NYU Depth V2 dataset. For each test sample, it shows the input image alongside ground truth depth, as well as the estimated depth maps produced by four different methods: ZoeDepth-NK, ZeroDepth, UniDepth-C and the proposed MfH. The absolute relative error maps (AbsRel) are also displayed, providing a visual representation of the accuracy of each method. The color scheme in the AbsRel maps indicates error magnitude, with warmer colors representing higher errors and cooler colors representing lower errors. This allows for a visual assessment of how well each method generalizes to unseen data, and showcases the superior performance of MfH in this zero-shot setting.

read the caption

Figure 12: Zero-shot qualitative results on NYU Depth v2.

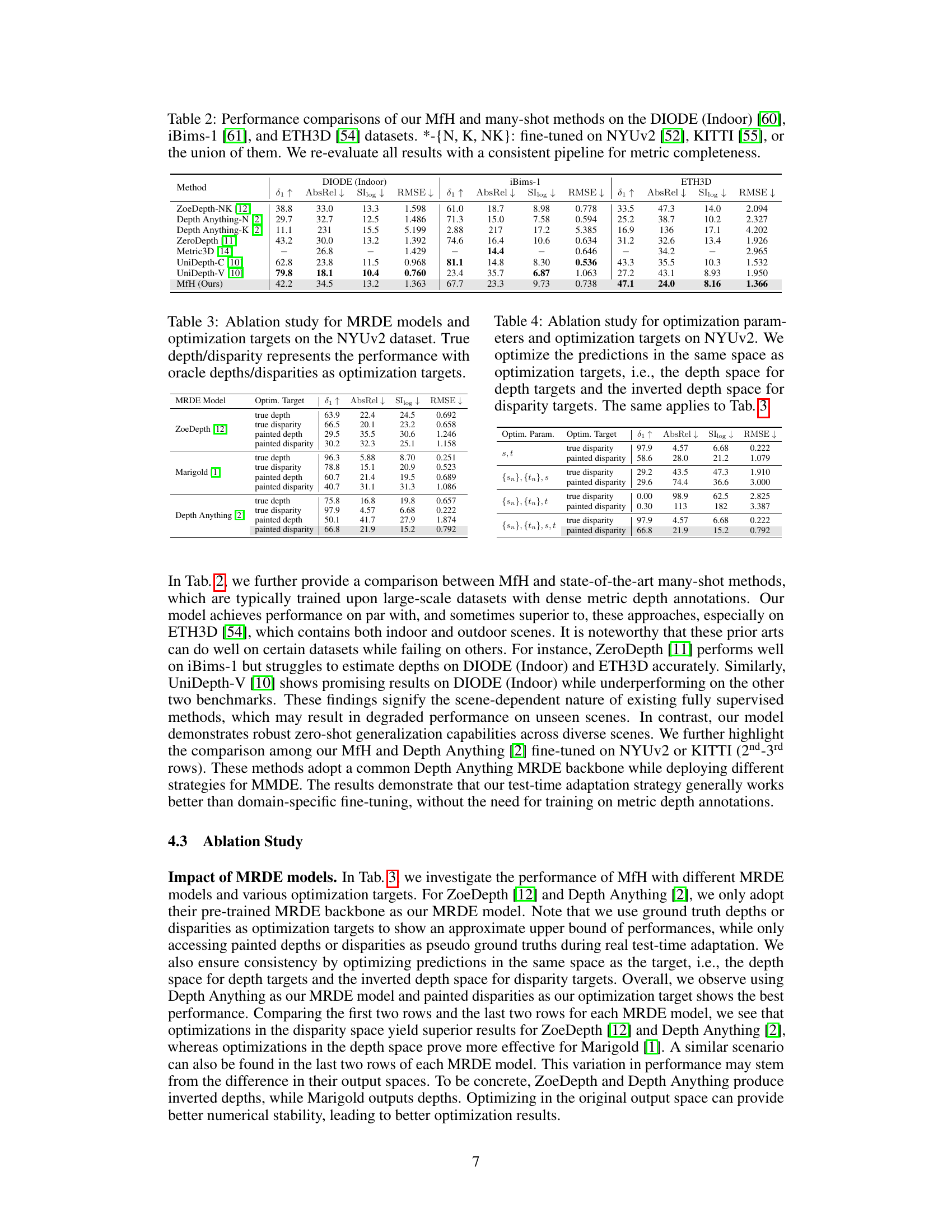

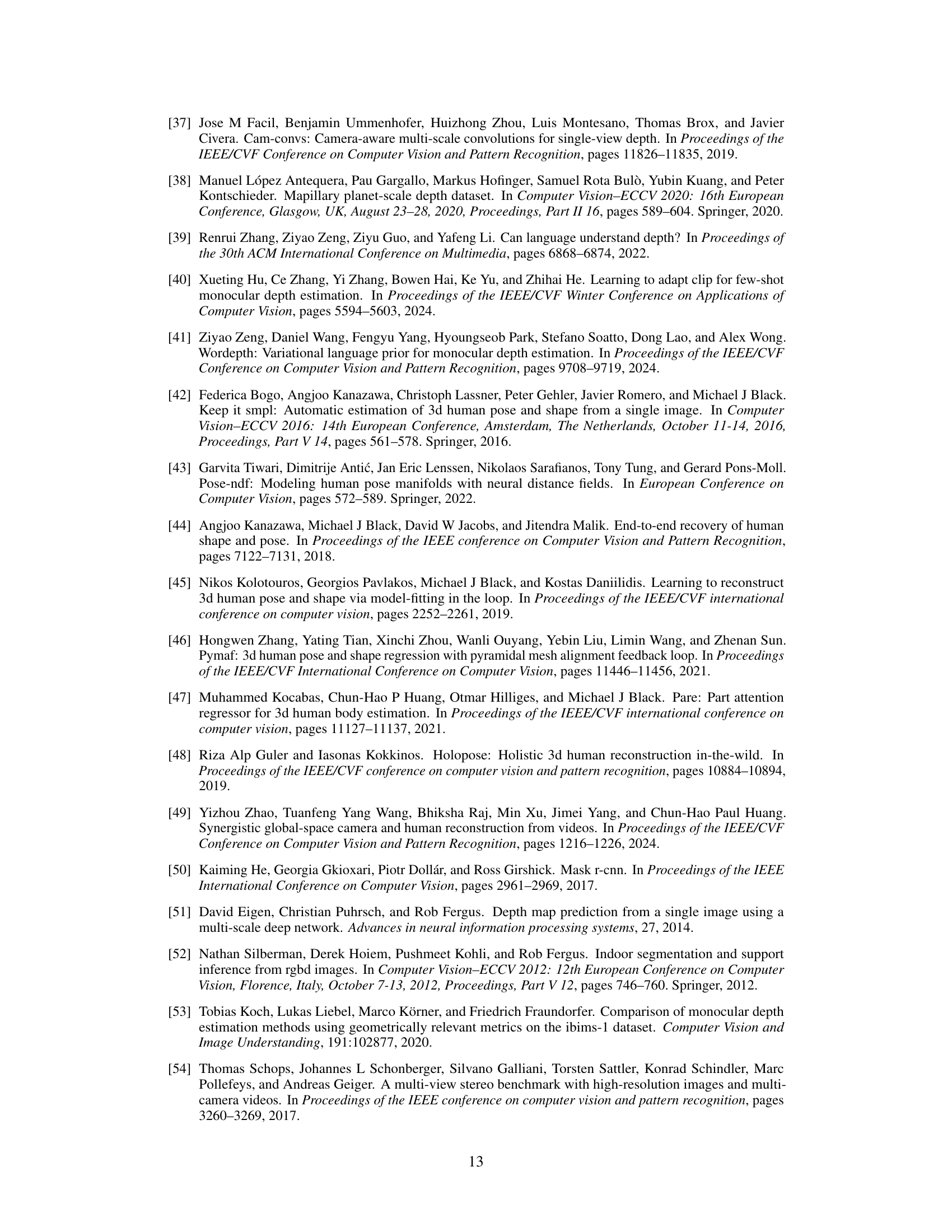

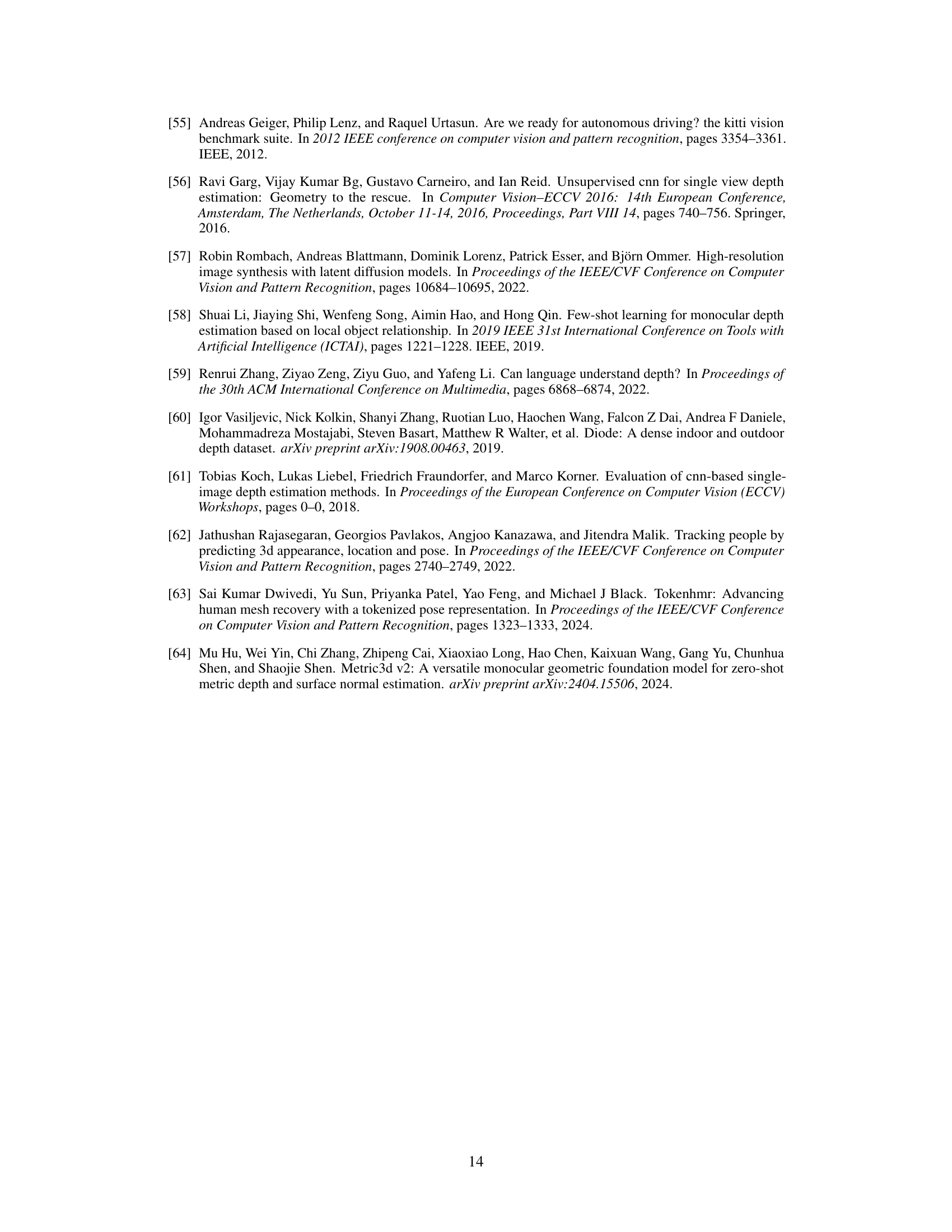

More on tables

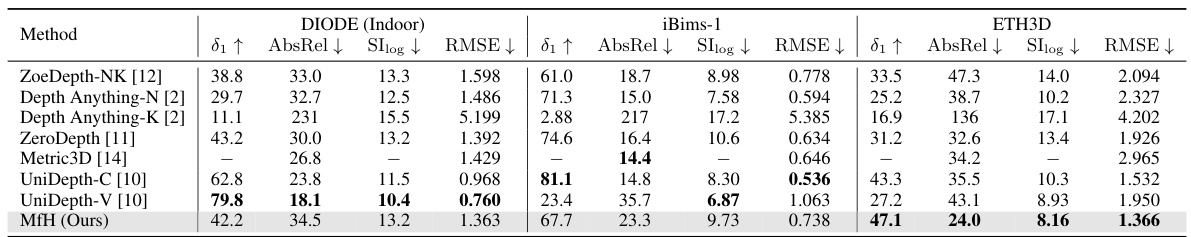

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed MfH method against several state-of-the-art many-shot methods on three different datasets: DIODE (Indoor), iBims-1, and ETH3D. The many-shot methods were fine-tuned on either NYUv2, KITTI, or a combination of both. The results are presented using several metrics such as 81, AbsRel, SIlog, and RMSE, allowing for a comprehensive comparison across different datasets and methods.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance comparisons of our MfH and many-shot methods on the DIODE (Indoor) [60], iBims-1 [61], and ETH3D [54] datasets. *-{N, K, NK}: fine-tuned on NYUv2 [52], KITTI [55], or the union of them. We re-evaluate all results with a consistent pipeline for metric completeness.

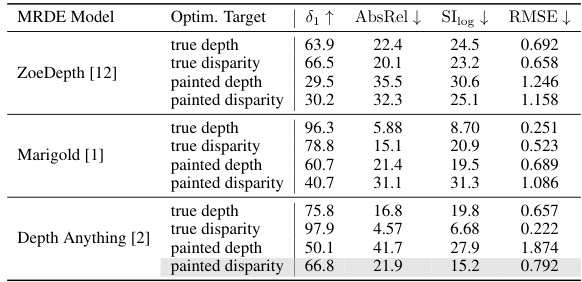

🔼 This table presents an ablation study evaluating the impact of different monocular relative depth estimation (MRDE) models and optimization targets on the NYUv2 dataset. It compares the performance using ground truth depths and disparities as targets against the results using depths and disparities generated from the proposed method’s generate-and-estimate pipeline. The metrics used for evaluation include 81, AbsRel, SIlog, and RMSE, providing a comprehensive assessment of the effects of model selection and target type on depth estimation accuracy.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation study for MRDE models and optimization targets on the NYUv2 dataset. True depth/disparity represents the performance with oracle depths/disparities as optimization targets.

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the optimization parameters and targets of the proposed method. It shows the performance of the model when using different combinations of optimization parameters and targets (true disparity, painted disparity). The results show that using all parameters (s,t,{sn},{tn}) and painted disparity as the optimization target yields the best performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study for optimization parameters and optimization targets on NYUv2. We optimize the predictions in the same space as optimization targets, i.e., the depth space for depth targets and the inverted depth space for disparity targets. The same applies to Tab. 3

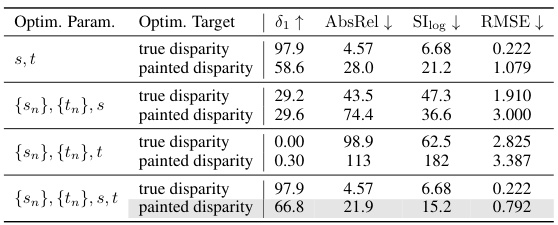

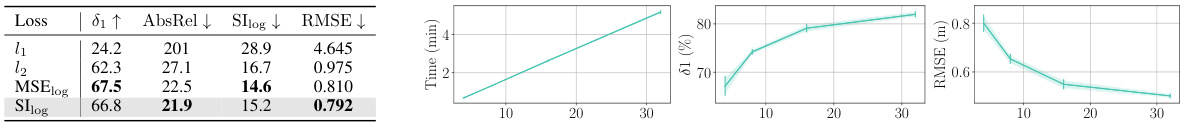

🔼 This table presents an ablation study on the effect of different loss functions on the model’s performance on the NYUv2 dataset. It compares the performance metrics (δ1, AbsRel, SIlog, RMSE) achieved using different loss functions (l1, l2, MSElog, SIlog) during test-time training of the metric head. The results show that loss functions incorporating an l2 term, particularly those using log-space, generally yield better performance.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation study for loss functions on NYUv2.

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed MfH method against several state-of-the-art many-shot methods on three datasets: DIODE (Indoor), iBims-1, and ETH3D. The performance is evaluated using three metrics: 81, AbsRel, and SIlog. The table also indicates whether the compared methods were fine-tuned on NYUv2, KITTI, or a combination of both. The results demonstrate MfH’s competitive performance, particularly on ETH3D, even compared to those methods trained on larger datasets.

read the caption

Table 2: Performance comparisons of our MfH and many-shot methods on the DIODE (Indoor) [60], iBims-1 [61], and ETH3D [54] datasets. *-{N, K, NK}: fine-tuned on NYUv2 [52], KITTI [55], or the union of them. We re-evaluate all results with a consistent pipeline for metric completeness.

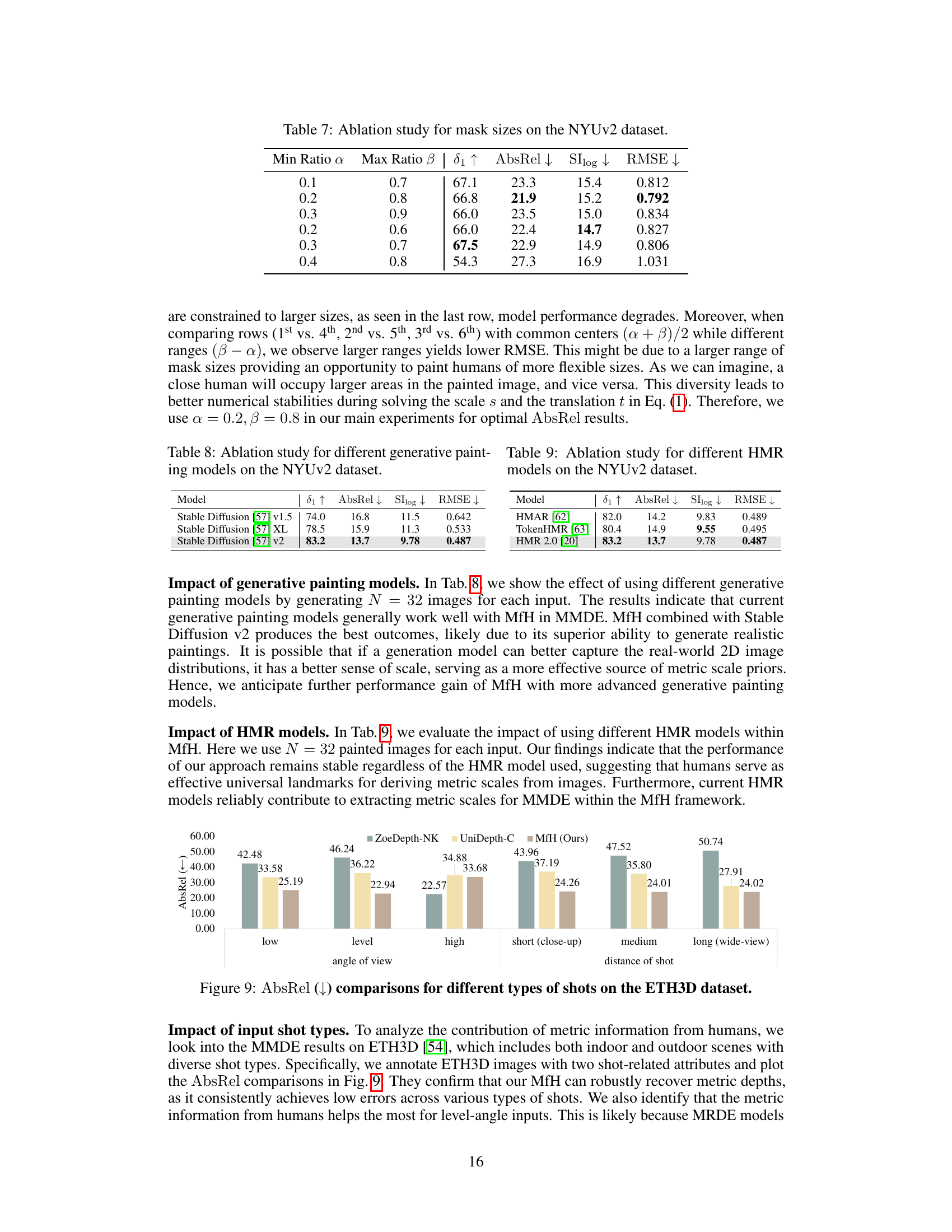

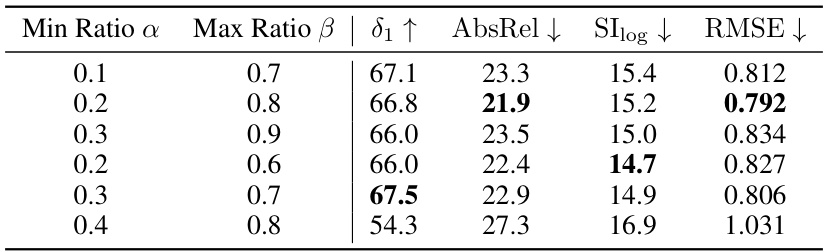

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on the effect of different mask sizes used in the generative painting process on the performance of the model. The results are evaluated using the metrics 81, AbsRel, SIlog, and RMSE on the NYUv2 dataset. The table shows that varying the minimum and maximum ratios of mask sizes affects the performance, with optimal performance achieved at a minimum ratio of 0.2 and a maximum ratio of 0.8.

read the caption

Table 7: Ablation study for mask sizes on the NYUv2 dataset.

🔼 This table presents the ablation study on different generative painting models used in the proposed method. The results are evaluated using four metrics: 81, AbsRel, SIlog, and RMSE on the NYUv2 dataset. It shows the impact of different generative painting models on the overall performance of the method, highlighting the best-performing model.

read the caption

Table 8: Ablation study for different generative painting models on the NYUv2 dataset.

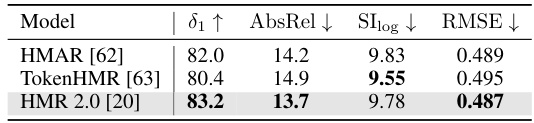

🔼 This table presents the ablation study of different human mesh recovery (HMR) models used in the proposed Metric from Human (MfH) framework. The performance is evaluated using four metrics: 81, AbsRel, SIlog, and RMSE on the NYU Depth V2 dataset. The results show that the performance of MfH is relatively stable regardless of the HMR model used, suggesting that humans serve as effective universal landmarks for deriving metric scales from images.

read the caption

Table 9: Ablation study for different HMR models on the NYUv2 dataset.

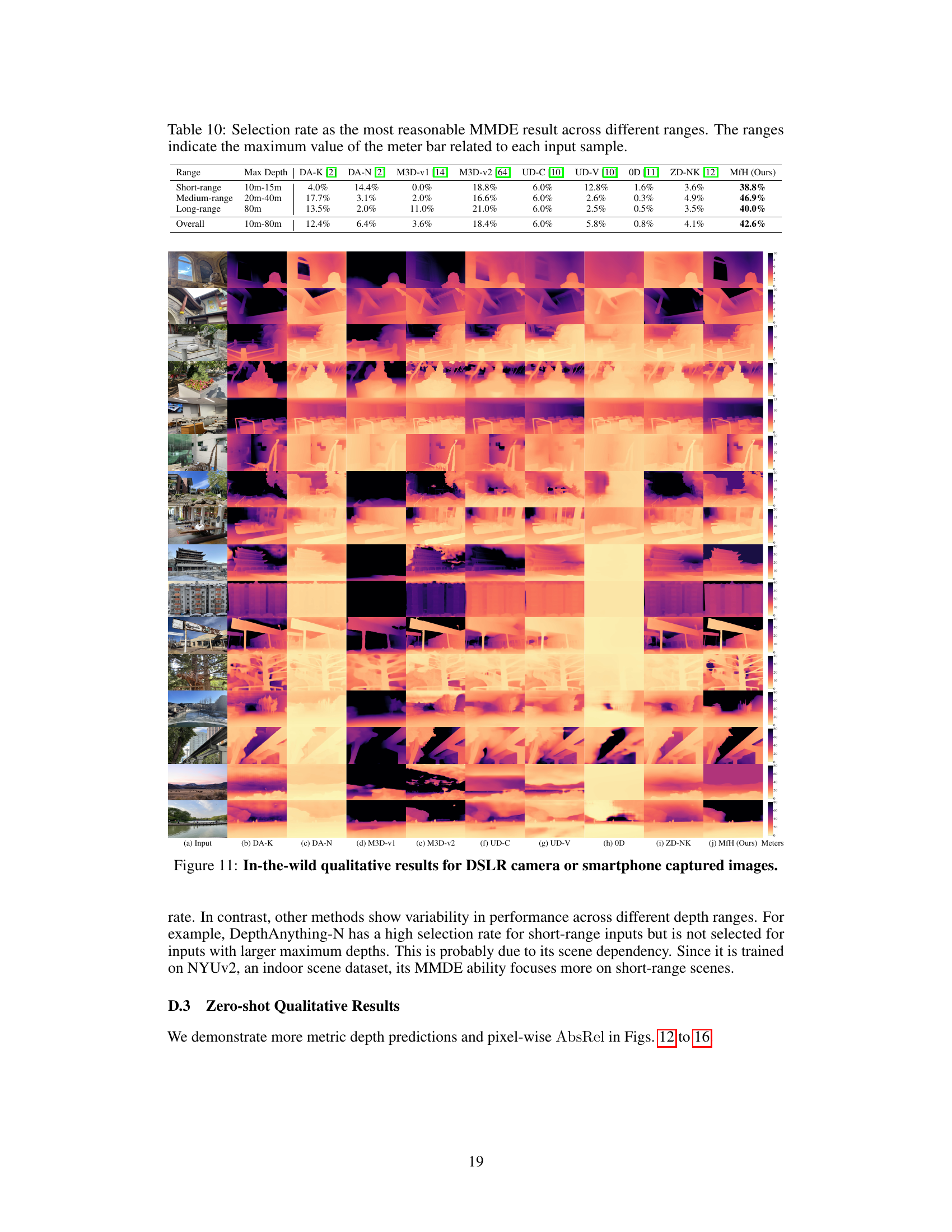

🔼 This table presents the results of a user study comparing different monocular metric depth estimation (MMDE) methods. Participants were shown input images and MMDE results from several methods and asked to select the most reasonable one. The table shows the percentage of times each method was selected, broken down by short, medium, and long depth ranges. The results show that the proposed MfH method achieved the highest selection rate across all ranges, demonstrating its robustness.

read the caption

Table 10: Selection rate as the most reasonable MMDE result across different ranges. The ranges indicate the maximum value of the meter bar related to each input sample.

Full paper#