TL;DR#

Overparameterized neural networks’ generalization ability is often attributed to a “simplicity bias”, where they initially learn simple classifiers before tackling complex ones. However, this bias wasn’t well understood in transformers trained with self-supervised methods. This paper investigates whether transformers trained on natural language data also show this sequential learning behavior. Existing methods to analyze this phenomenon face the challenge of analyzing higher-order interactions due to high computational costs.

This research introduces a novel framework to address this issue. By training transformers with factored self-attention and using Monte Carlo sampling, the study generates “clones” of the original dataset with varying levels of interaction complexity. Experiments using these clones on standard BERT and GPT models reveal a clear simplicity bias: transformers first learn low-order interactions, then progressively learn higher-order ones. The saturation point in error for low-degree interactions highlights this sequential learning. This finding significantly improves our understanding of transformer learning and opens new avenues for optimization.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for NLP researchers because it reveals a novel “simplicity bias” in transformers, demonstrating that they sequentially learn interactions of increasing complexity. This understanding can guide the design of more efficient and effective transformer models, and it opens up new avenues for studying how interactions of different orders in data impact learning, advancing the field beyond current limitations.

Visual Insights#

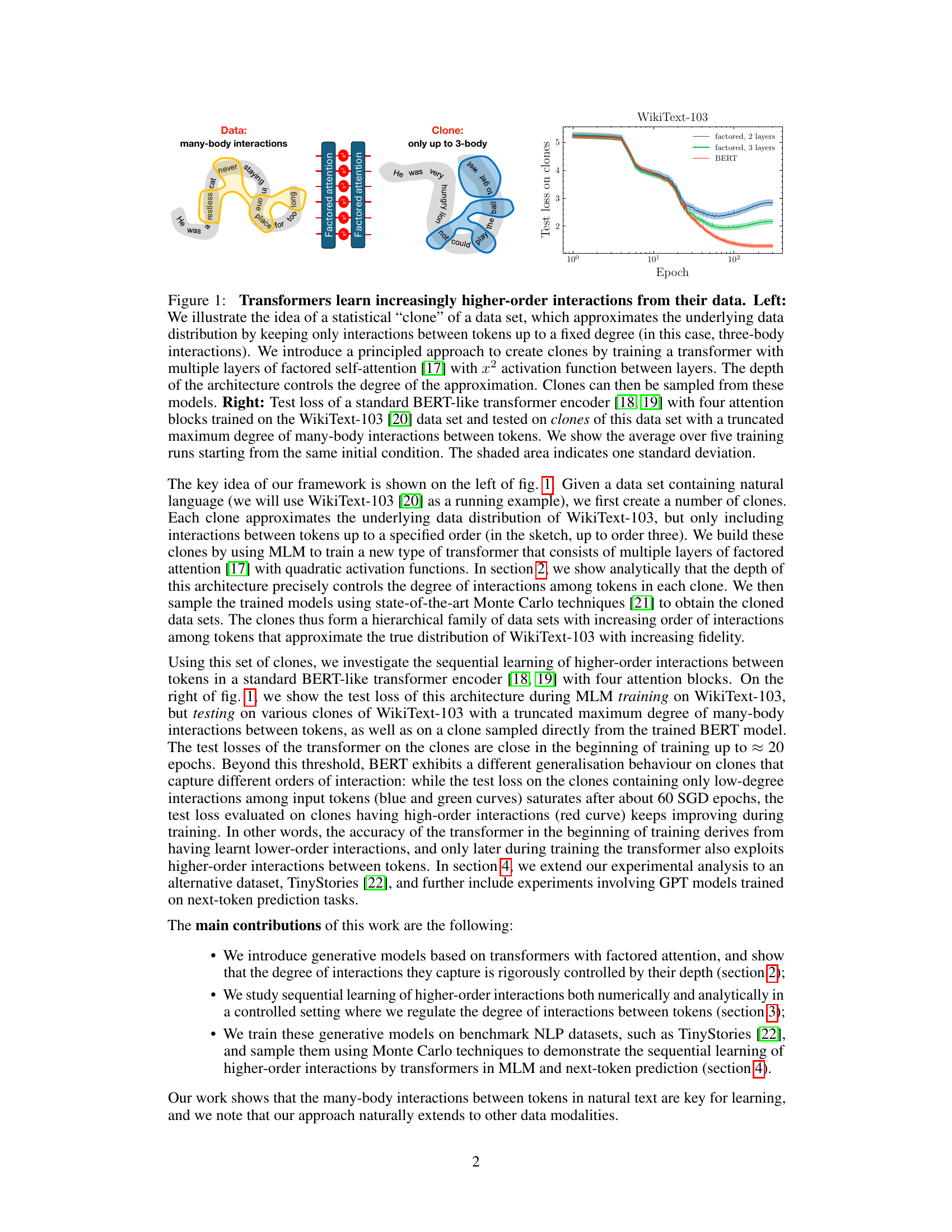

🔼 This figure demonstrates that transformers learn higher-order interactions sequentially. The left panel illustrates the creation of ‘clones’ of a dataset, which are simplified versions that only include interactions up to a specified order (here, three-body interactions). These clones are generated using a transformer with factored self-attention and a quadratic activation function, where the depth of the network controls the maximum interaction order. The right panel shows the training loss of a standard BERT-like transformer on WikiText-103, tested on clones with varying maximum interaction orders. The results indicate that the transformer initially learns low-order interactions, reaching a saturation point in the loss before continuing to learn higher-order interactions, highlighting the sequential nature of its learning process.

read the caption

Figure 1: Transformers learn increasingly higher-order interactions from their data. Left: We illustrate the idea of a statistical “clone” of a data set, which approximates the underlying data distribution by keeping only interactions between tokens up to a fixed degree (in this case, three-body interactions). We introduce a principled approach to create clones by training a transformer with multiple layers of factored self-attention [17] with x² activation function between layers. The depth of the architecture controls the degree of the approximation. Clones can then be sampled from these models. Right: Test loss of a standard BERT-like transformer encoder [18, 19] with four attention blocks trained on the WikiText-103 [20] data set and tested on clones of this data set with a truncated maximum degree of many-body interactions between tokens. We show the average over five training runs starting from the same initial condition. The shaded area indicates one standard deviation.

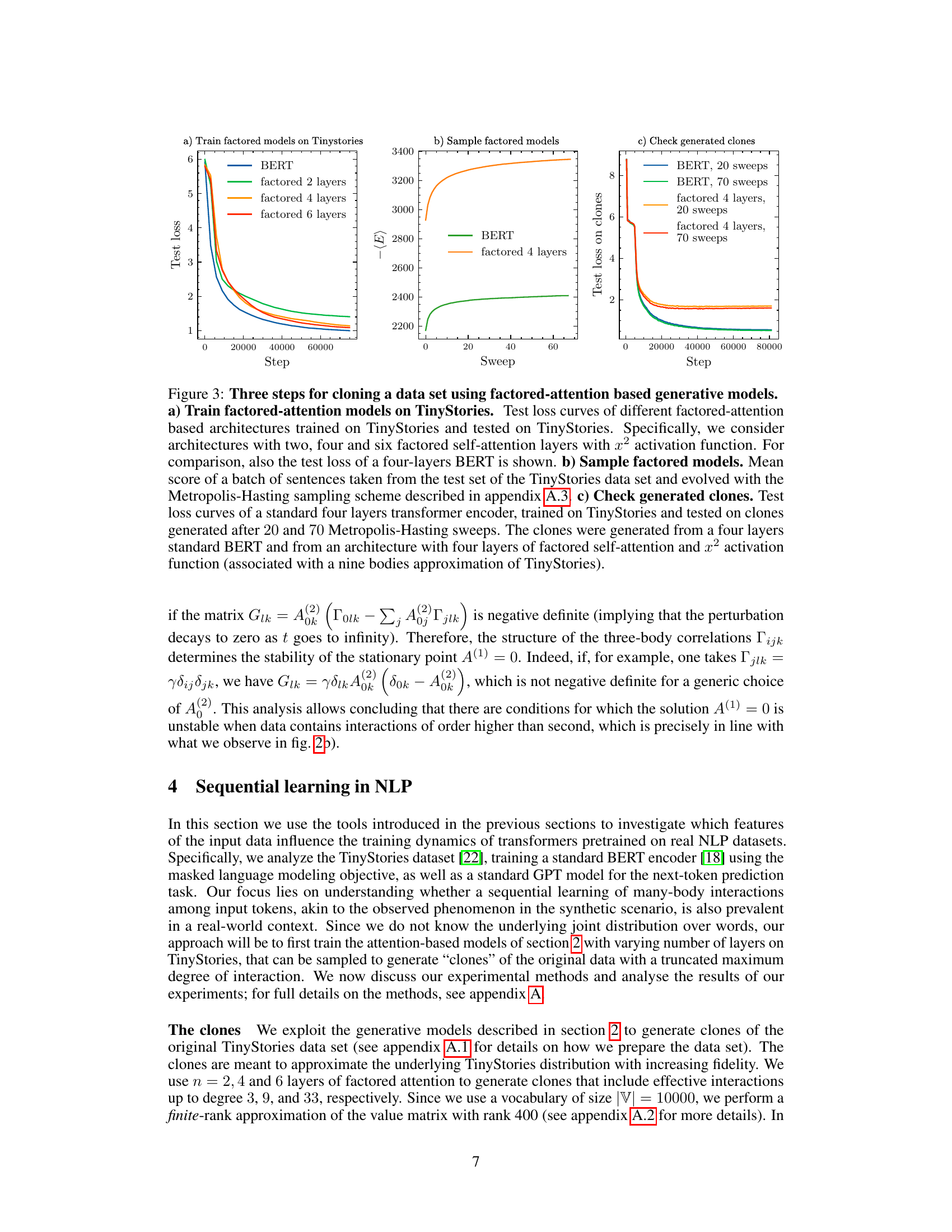

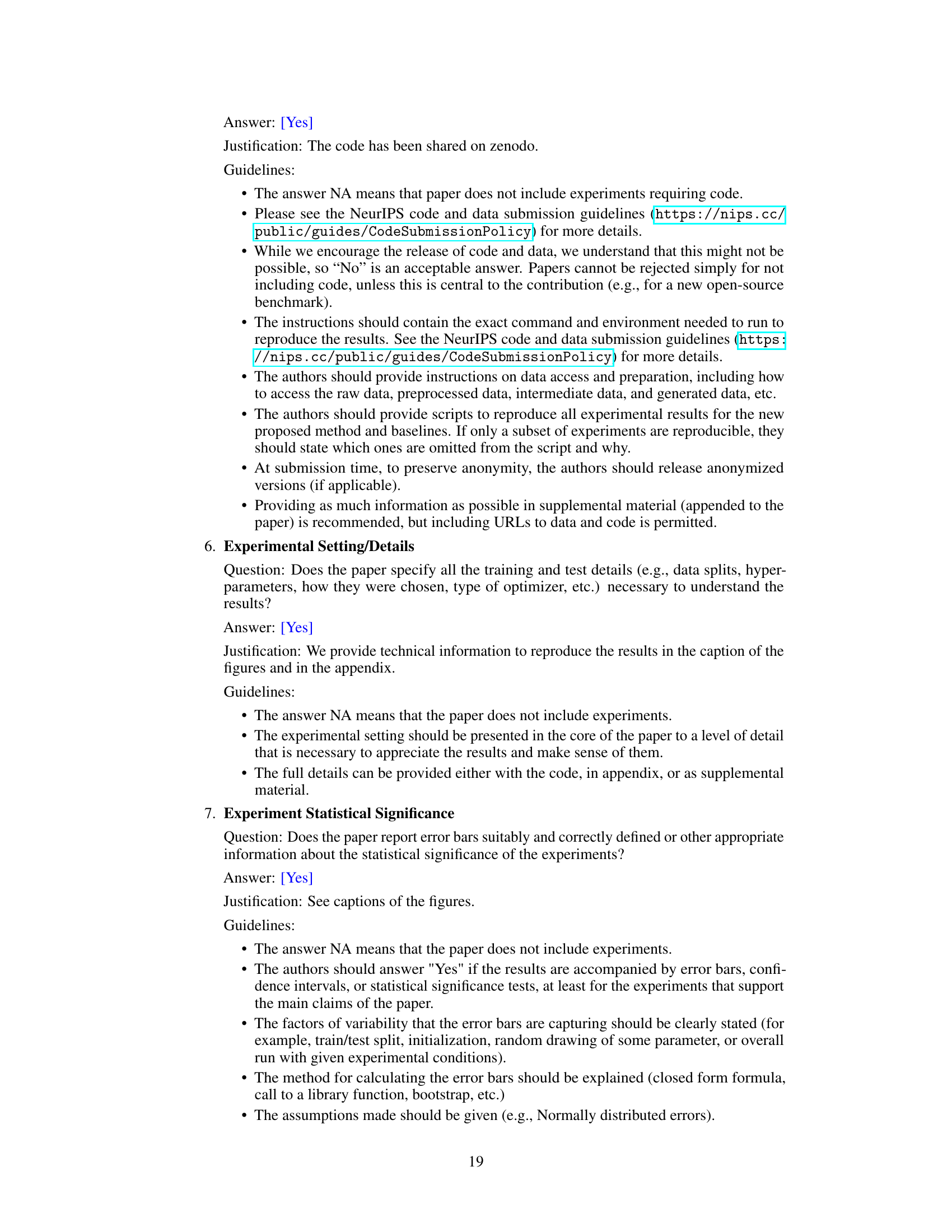

🔼 This table shows examples of how the original text from the TinyStories dataset is modified after applying Monte Carlo sampling using different architectures (factored with 2 and 4 layers, and BERT). It illustrates the effect of varying the model’s capacity to capture higher-order interactions on the generated text.

read the caption

Table 1: Sampling the clones. In the first row, we show part of a sentence taken from the test set of TinyStories. The second, third and fourth rows show how the original text is modified after 20 sweeps of Monte Carlo sampling associated to two and four layers factored architectures and BERT architectures, respectively.

In-depth insights#

Simplicity Bias#

The concept of “Simplicity Bias” in the context of deep learning, particularly concerning transformer models, centers on the observation that these models tend to initially learn simpler patterns and representations before progressing to more complex ones. This isn’t a conscious choice, but rather an emergent property of the training process. The paper explores this by showing how transformers initially prioritize lower-order interactions (e.g., individual words or bigrams) within natural language data, before gradually incorporating higher-order relationships between words. This sequential learning is not random; it’s a structured progression demonstrating a bias towards simplicity. The study leverages a novel methodology to create controlled datasets which isolate different orders of interaction, offering strong evidence to support this “Simplicity Bias”. The findings are significant because they provide insights into the generalization capabilities of these overparameterized models and suggest the importance of examining the learning trajectory, not just the final performance. By carefully controlling the complexity of input data, the research reveals a more nuanced understanding of how these powerful models actually learn.

Transformer Clones#

The concept of “Transformer Clones” presents a novel approach to analyzing the learning dynamics of transformer models. By creating these clones, which are simplified versions of the original dataset with controlled levels of interaction complexity, researchers gain a powerful tool to dissect how transformers learn. The clones allow for a systematic investigation of the sequential learning of many-body interactions, revealing that transformers initially focus on simpler relationships before gradually incorporating higher-order dependencies. This method offers valuable insights into the “simplicity bias” hypothesis, suggesting that transformers prioritize learning easier patterns first, and this is crucial for understanding generalization capabilities. The process of generating clones itself is significant, requiring careful design of the clone generation model to accurately capture the desired level of interaction complexity. Therefore, the creation and utilization of Transformer Clones offers a new way to examine and potentially improve upon the design and training of transformer-based models.

Sequential Learning#

The concept of “sequential learning” in the context of transformer models centers on the observation that these models don’t learn all aspects of a complex task simultaneously. Instead, they exhibit a phased learning process, progressing from simpler to more complex representations. This is especially evident when considering many-body interactions among input tokens; initial training focuses on lower-order interactions (e.g., unigrams, bigrams), with higher-order interactions learned only in later stages. This sequential acquisition of knowledge is not pre-programmed but emerges from the model’s dynamics during training. This sequential learning is a form of simplicity bias, enabling the model to avoid overfitting while progressively improving performance on more challenging, nuanced aspects of the language. The researchers demonstrate this through clever data manipulation using “clones” — synthetic datasets with controlled interaction complexity. By testing model performance across these clones, they reveal the gradual transition from basic to more sophisticated pattern recognition during training. This insight is crucial for understanding how over-parameterized neural networks generalize effectively and could inform future improvements in training efficiency and model architecture.

Factored Attention#

Factored attention, a simplified variant of standard self-attention, offers a powerful mechanism for controlling the complexity of learned interactions in transformer networks. By design, it makes the attention weights independent of the input tokens, resulting in a more interpretable model that directly captures interactions up to a specific order. This contrasts with standard self-attention, where the interaction orders are implicitly determined during training. The depth of a factored attention network directly correlates with the highest order of interactions it can capture, allowing researchers to build models that systematically learn increasingly complex representations. This approach simplifies the process of studying the learning dynamics of transformers by providing a rigorous way to analyze how these higher-order interactions contribute to performance. The ability to create ‘clones’ of datasets with controlled interaction orders is a valuable contribution, enabling focused studies of how models generalize to various levels of complexity and offering significant advantages in analytical tractability and experimental control.

Future Directions#

The study’s “Future Directions” section could explore several promising avenues. Improving the sampling methods used to generate data clones is crucial for enhancing the accuracy and reliability of the results. This could involve investigating advanced Monte Carlo techniques or developing entirely new methods tailored to the complexities of high-dimensional data distributions. Extending the analytical framework to higher-dimensional embedding spaces and more complex activation functions would enhance the theoretical understanding of the observed sequential learning behavior. This could unlock further insights into the specific role of different architectural elements in shaping the learning dynamics. Finally, applying this innovative approach to diverse data modalities beyond NLP, such as image data or biological sequences, could reveal the universality and limitations of the distributional simplicity bias observed in transformers. This would broaden the impact of the research and lead to more generalizable conclusions about the learning processes within deep neural networks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the results of experiments using a multi-layer factored self-attention architecture with a quadratic activation function (x²). Panel (a) illustrates the architecture. Panel (b) displays the test loss learning curves for models with 1, 2, and 3 layers, trained on a synthetic dataset with four-body interactions. The dashed lines represent the convergence values of the test loss for 2, 3, and 4-body interaction models. Finally, Panel (c) depicts the Mean Square Displacement (MSD) of the weights across layers in the 3-layer model, showcasing the sequential activation of layers during training.

read the caption

Figure 2: a) Multi-layer factored self-attention architecture with x² activation function. b) Test loss learning curves of one, two and three factored self-attention layers with x² activation function. The models were trained on a synthetic data set generated from a four-body Hamiltonian. The dashed horizontal lines correspond to the convergence value of the loss for two, three and four bodies energy based models trained on the same data set. c) Mean Square Displacement of the weights across different layers in a three-layers factored attention architecture. In these experiments, the size of the vocabulary was set to |V| = 10 and the sequence length to L = 20. We used a training set of M = 25600 samples, training the models with SGD, choosing a mini-batch size of 256. The initial learning rate is chosen to be 0.1.

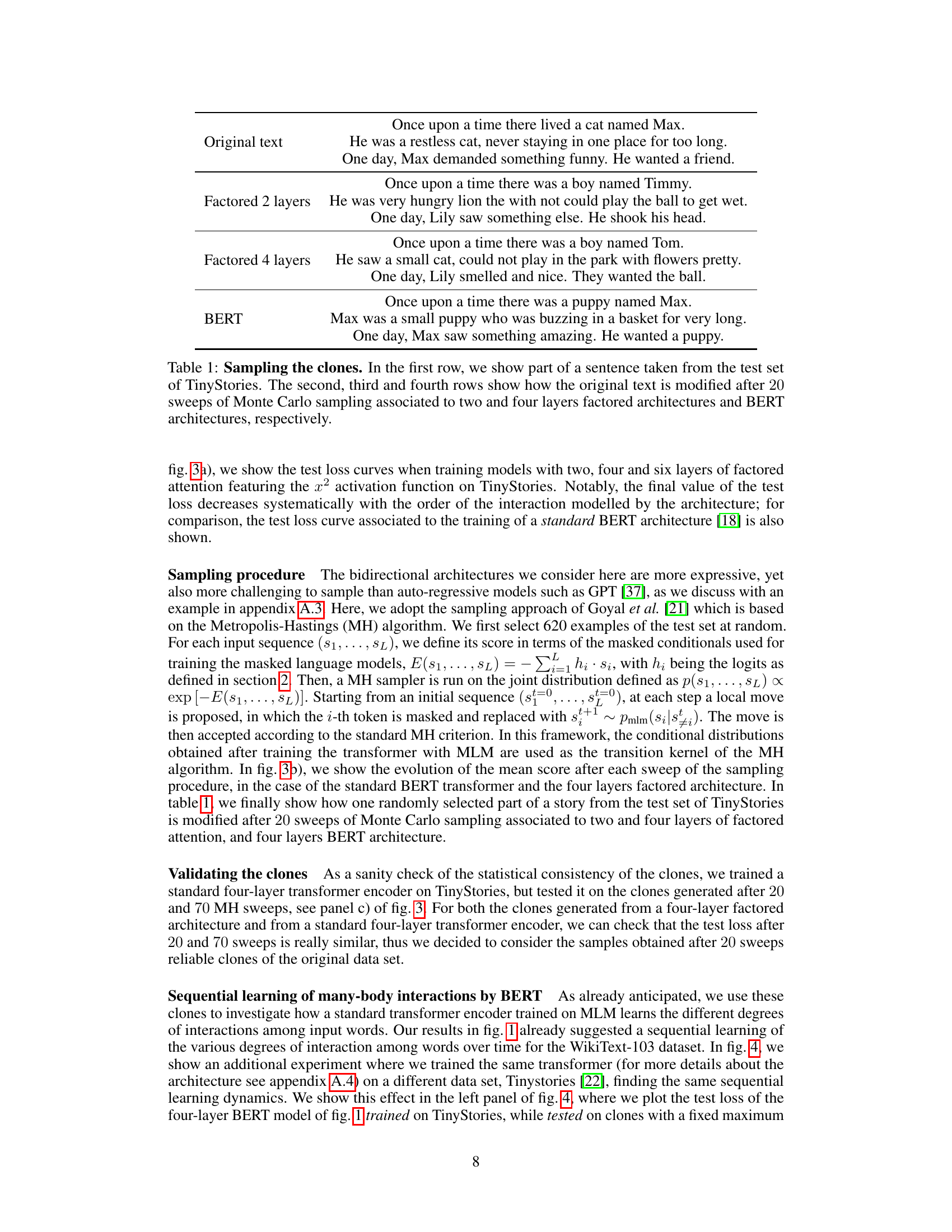

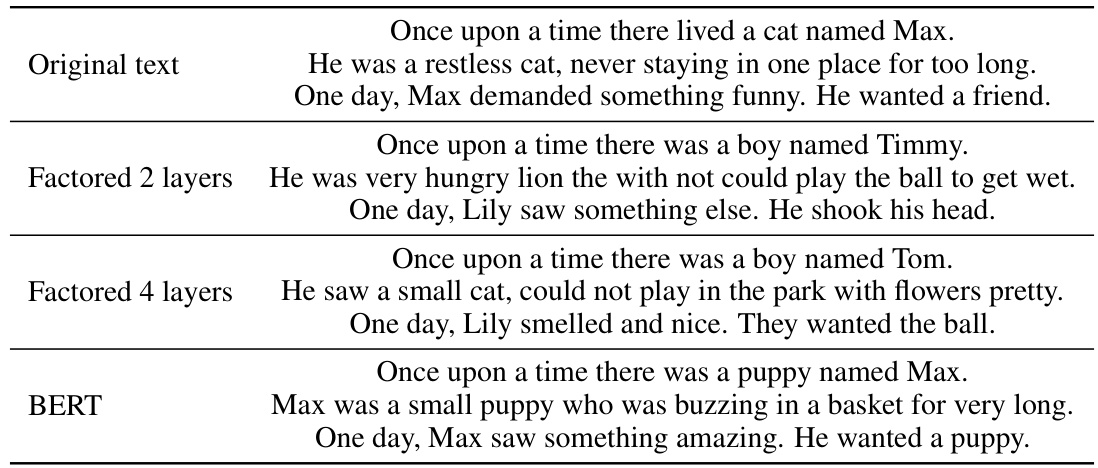

🔼 This figure shows the three steps involved in cloning a dataset using factored-attention-based generative models. Panel (a) compares the performance of different models (BERT and models with varying layers of factored attention) trained on the TinyStories dataset and evaluated on the original TinyStories dataset. Panel (b) illustrates the sampling process used to generate the clones. Finally, panel (c) presents the performance of these different models trained on the original TinyStories and evaluated on the generated clones.

read the caption

Figure 3: Three steps for cloning a data set using factored-attention based generative models. a) Train factored-attention models on TinyStories. Test loss curves of different factored-attention based architectures trained on TinyStories and tested on TinyStories. Specifically, we consider architectures with two, four and six factored self-attention layers with x² activation function. For comparison, also the test loss of a four-layers BERT is shown. b) Sample factored models. Mean score of a batch of sentences taken from the test set of the TinyStories data set and evolved with the Metropolis-Hasting sampling scheme described in appendix A.3. c) Check generated clones. Test loss curves of a standard four layers transformer encoder, trained on TinyStories and tested on clones generated after 20 and 70 Metropolis-Hasting sweeps. The clones were generated from a four layers standard BERT and from an architecture with four layers of factored self-attention and x2 activation function (associated with a nine bodies approximation of TinyStories).

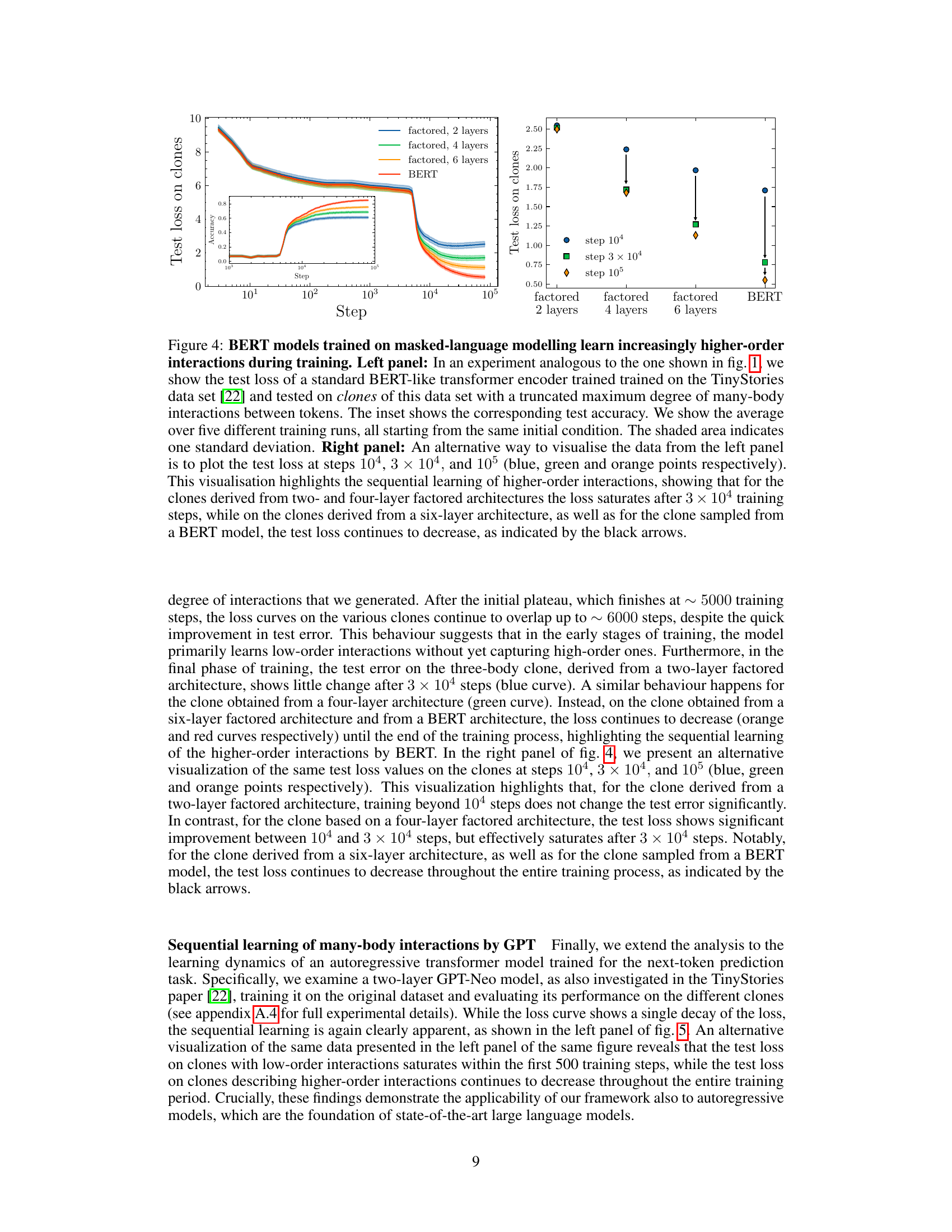

🔼 This figure shows the results of training a BERT model on the TinyStories dataset and evaluating its performance on clones of the dataset with varying degrees of many-body interactions. The left panel shows the test loss curves over training steps for BERT and for clones generated using factored self-attention models with 2, 4, and 6 layers. The inset shows the corresponding test accuracy. The right panel provides an alternative visualization, highlighting the sequential learning of higher-order interactions by BERT.

read the caption

Figure 4: BERT models trained on masked-language modelling learn increasingly higher-order interactions during training. Left panel: In an experiment analogous to the one shown in fig. 1, we show the test loss of a standard BERT-like transformer encoder trained trained on the TinyStories data set [22] and tested on clones of this data set with a truncated maximum degree of many-body interactions between tokens. The inset shows the corresponding test accuracy. We show the average over five different training runs, all starting from the same initial condition. The shaded area indicates one standard deviation. Right panel: An alternative way to visualise the data from the left panel is to plot the test loss at steps 104, 3 × 104, and 105 (blue, green and orange points respectively). This visualisation highlights the sequential learning of higher-order interactions, showing that for the clones derived from two- and four-layer factored architectures the loss saturates after 3 × 104 training steps, while on the clones derived from a six-layer architecture, as well as for the clone sampled from a BERT model, the test loss continues to decrease, as indicated by the black arrows.

🔼 This figure shows the results of an experiment where a BERT model was trained on the TinyStories dataset and tested on different clones of the dataset, where each clone has a different maximum order of interactions between tokens. The left panel shows the test loss curves for different models (BERT and factored attention with 2, 4, and 6 layers), indicating that BERT continues to improve even after other models plateau. The right panel provides an alternative visualization, emphasizing that higher-order interactions are learned sequentially.

read the caption

Figure 4: BERT models trained on masked-language modelling learn increasingly higher-order interactions during training. Left panel: In an experiment analogous to the one shown in fig. 1, we show the test loss of a standard BERT-like transformer encoder trained trained on the TinyStories data set [22] and tested on clones of this data set with a truncated maximum degree of many-body interactions between tokens. The inset shows the corresponding test accuracy. We show the average over five different training runs, all starting from the same initial condition. The shaded area indicates one standard deviation. Right panel: An alternative way to visualise the data from the left panel is to plot the test loss at steps 104, 3 × 104, and 105 (blue, green and orange points respectively). This visualisation highlights the sequential learning of higher-order interactions, showing that for the clones derived from two- and four-layer factored architectures the loss saturates after 3 × 104 training steps, while on the clones derived from a six-layer architecture, as well as for the clone sampled from a BERT model, the test loss continues to decrease, as indicated by the black arrows.

Full paper#