↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current biologically plausible models of cortical learning often use a combination of bottom-up (BU) and top-down (TD) processing, but they often fail to integrate TD’s role in visual attention. This is a significant limitation, as the human visual system uses top-down signals to guide attention. Moreover, existing models face challenges with backpropagation, which is crucial for effective learning. These issues necessitate a new learning model that combines BU and TD processing effectively.

This research presents a new model that addresses these limitations. It uses a cortical-like combination of BU and TD processing to integrate both learning and visual guidance, achieving this through novel connectivity, processing cycles, and a ‘Counter-Hebb’ learning mechanism that approximates backpropagation. The model shows significant improvements in learning efficiency and achieves competitive performance on standard multi-task learning benchmarks.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is highly relevant to researchers in neuroscience and AI, particularly those working on biologically plausible learning models and vision-language models. It offers a novel approach to combining bottom-up and top-down processing, which could significantly impact both theoretical understanding and practical applications. The proposed model’s success in integrating learning and visual guidance opens exciting new avenues for investigation in model development and improving the model’s learning efficiency.

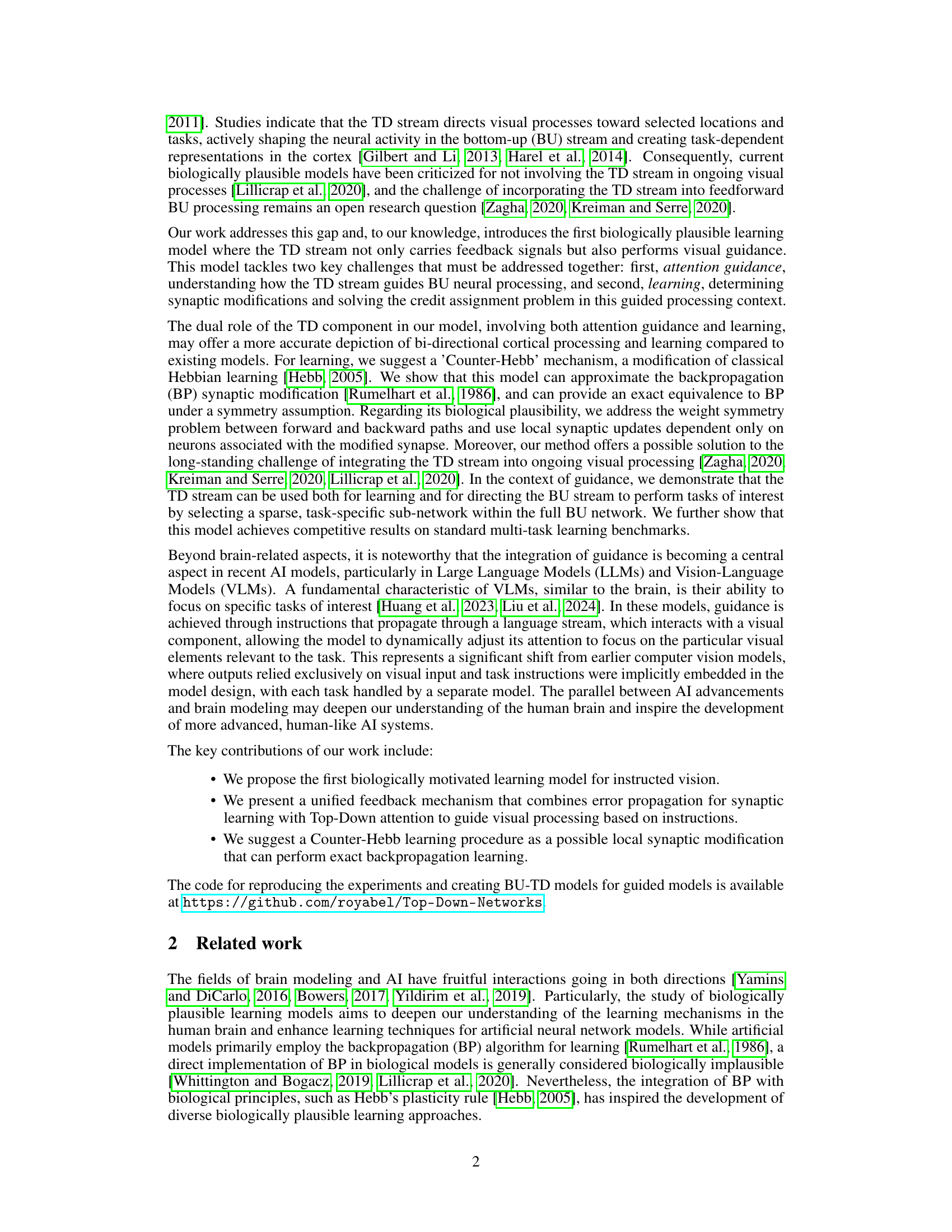

Visual Insights#

The figure compares the classical Hebb rule and the proposed Counter-Hebb rule for synaptic weight updates. The Hebb rule updates a synapse based on the pre- and post-synaptic neuron activations. The Counter-Hebb rule incorporates lateral connectivity, using the activation of a ‘counter neuron’ in the opposite stream to modify the synapse, effectively providing feedback signals from the top-down pathway for synaptic modification.

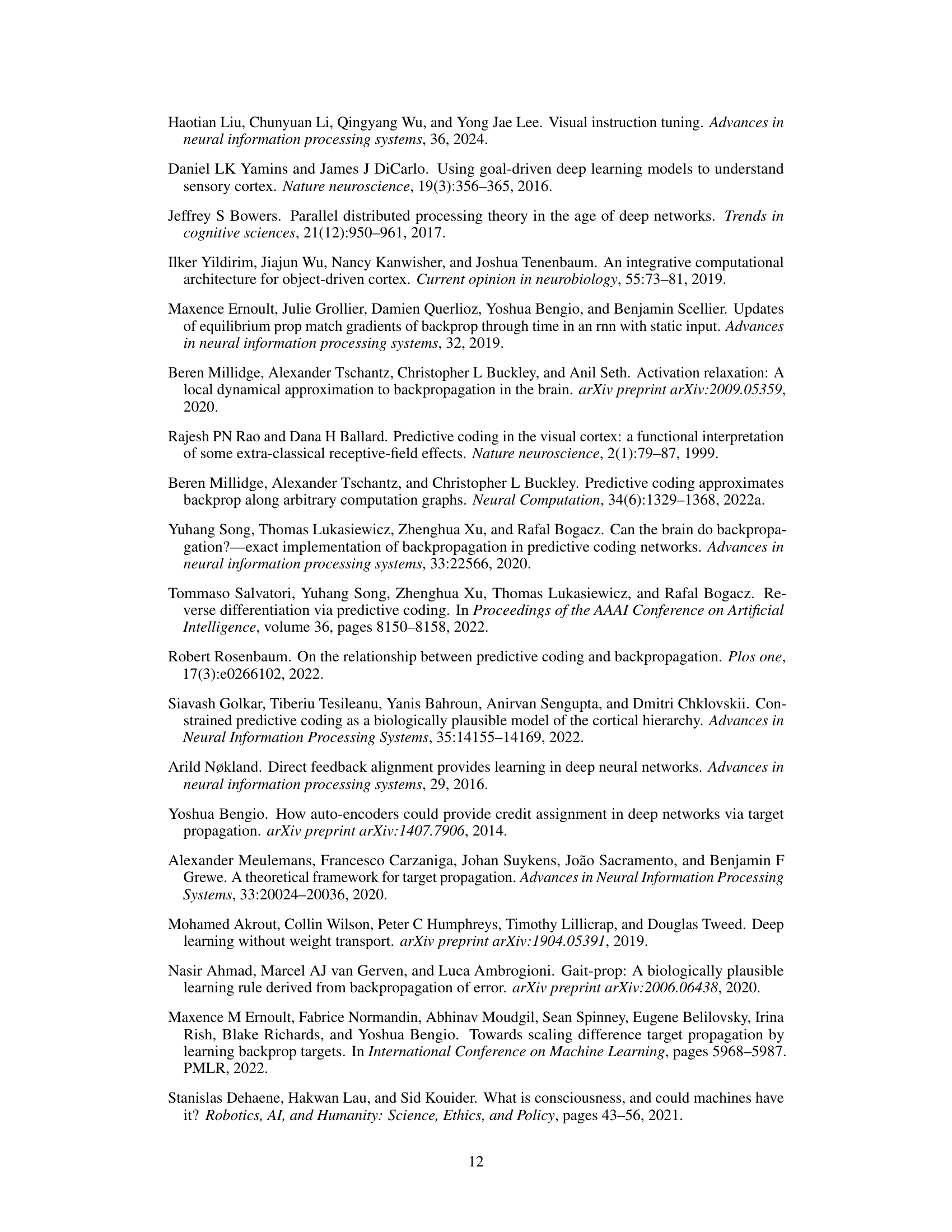

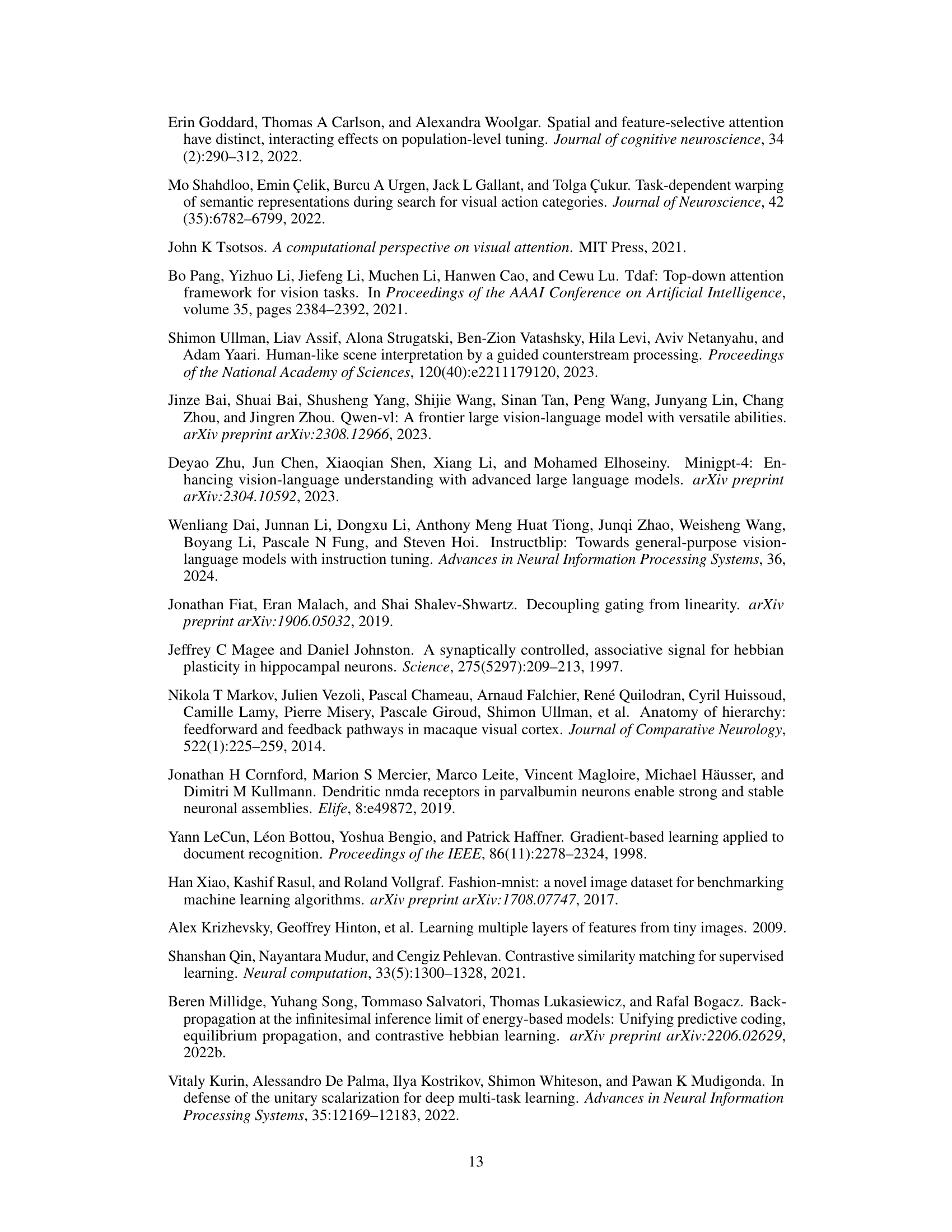

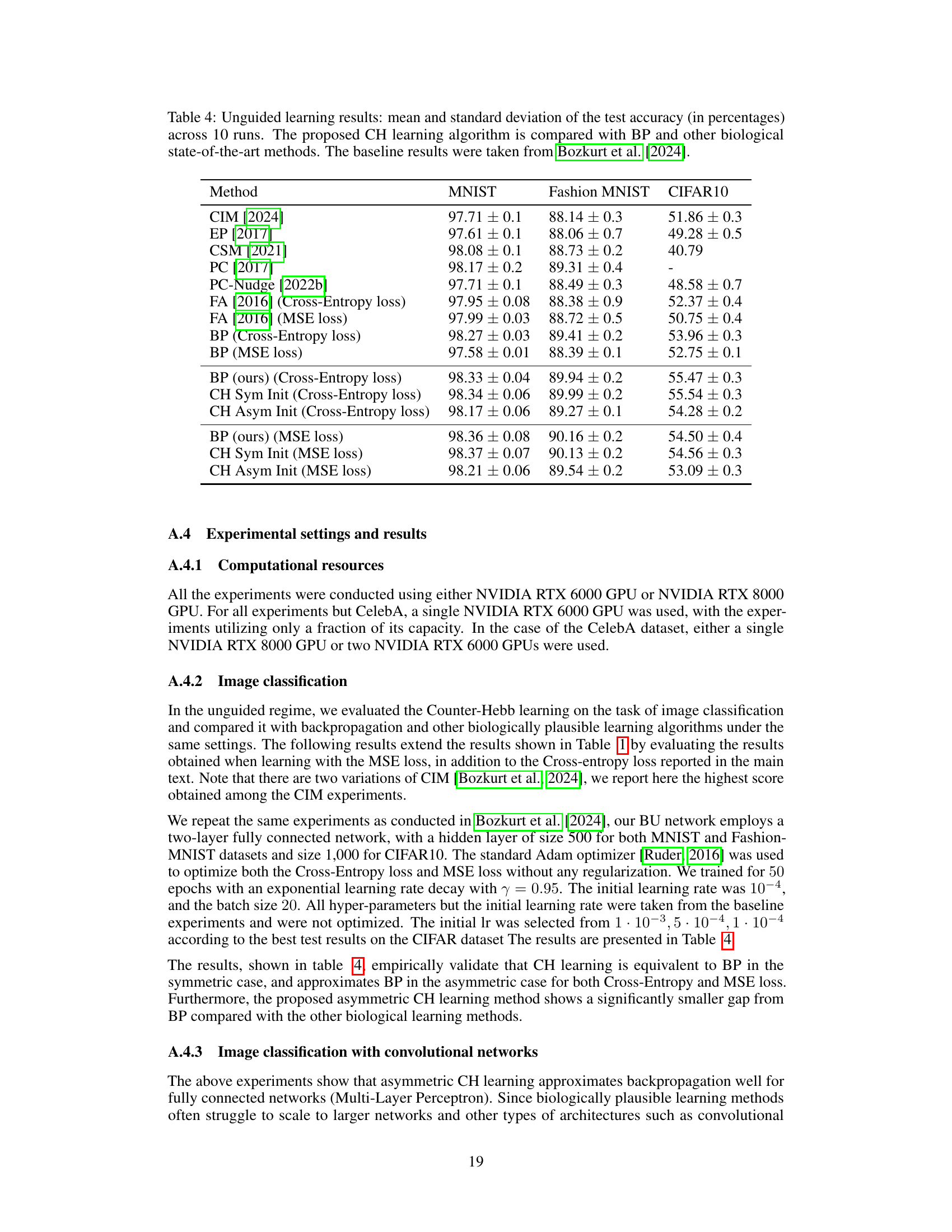

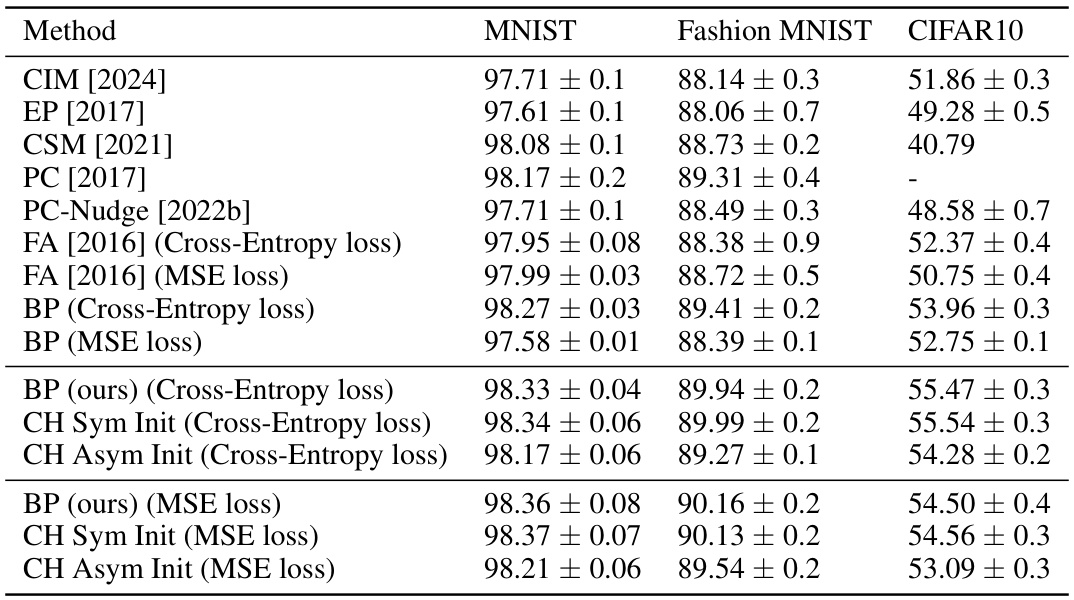

This table presents the results of unguided learning experiments on standard image classification benchmarks (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR10). It compares the performance of the proposed Counter-Hebb (CH) learning algorithm with backpropagation (BP) and other biologically plausible learning methods. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the test accuracy across 10 runs for each method and dataset.

In-depth insights#

Bio-Plausible Learning#

Bio-plausible learning aims to bridge the gap between neuroscience and artificial intelligence by creating learning models inspired by the biological mechanisms of the brain. It moves beyond simply replicating brain structure and instead focuses on mimicking learning processes. This often involves replacing computationally expensive algorithms like backpropagation with more biologically realistic alternatives such as Hebbian learning or predictive coding. A core challenge is addressing the ‘credit assignment problem’, which refers to how the brain determines which synapses should be strengthened or weakened during learning. Bio-plausible models often incorporate bottom-up and top-down processing pathways, similar to the brain’s cortical structure, enabling more efficient learning. The ultimate goal is to develop efficient and robust AI systems that are both powerful and interpretable, drawing inspiration from the brain’s remarkable learning capabilities. However, modeling the complexity of the brain remains a significant challenge, and many bio-plausible approaches involve simplifying assumptions or focus on specific aspects of learning.

Counter-Hebb Rule#

The Counter-Hebb rule, a proposed modification of Hebbian learning, presents a novel approach to synaptic plasticity. Instead of relying solely on pre- and post-synaptic neuron co-activation, it incorporates feedback signals from a “counter neuron” in the opposing (top-down or bottom-up) network. This mechanism elegantly approximates backpropagation, a computationally expensive algorithm crucial for deep learning, potentially offering a more biologically plausible alternative. The strength of this approach lies in its ability to integrate both learning and attention guidance, addressing a key limitation of many biological models. By dynamically adjusting weights based on counter-neuron activity, the Counter-Hebb rule achieves task-dependent visual processing, effectively guiding neural activity towards relevant regions of interest. This integration is further enhanced by a novel processing cycle that leverages the top-down stream twice, creating an elegant framework for instructed vision. However, the rule’s biological plausibility and performance in complex scenarios remain open questions requiring further investigation. Weight symmetry appears crucial for optimal equivalence to backpropagation, a constraint that might pose challenges in biological implementations.

Guided Visual Proc.#

The heading ‘Guided Visual Processing’ suggests a focus on how top-down signals influence and direct the flow of visual information processing. This is in contrast to traditional feedforward models that only consider bottom-up input. The research likely explores how attention mechanisms and task-specific goals shape the neural activity in visual areas. A key aspect might involve demonstrating the efficiency and accuracy gains from incorporating top-down guidance. It would also probably examine the biological plausibility of proposed models by comparing them to known neural pathways and mechanisms in the brain, particularly in the visual cortex. The effectiveness of the model on various benchmark tasks might be compared with purely bottom-up approaches. The ultimate aim of this section would be to show how incorporating biologically-inspired top-down guidance can improve the performance and efficiency of visual processing models, potentially leading to more human-like vision systems.

Weight Symmetry#

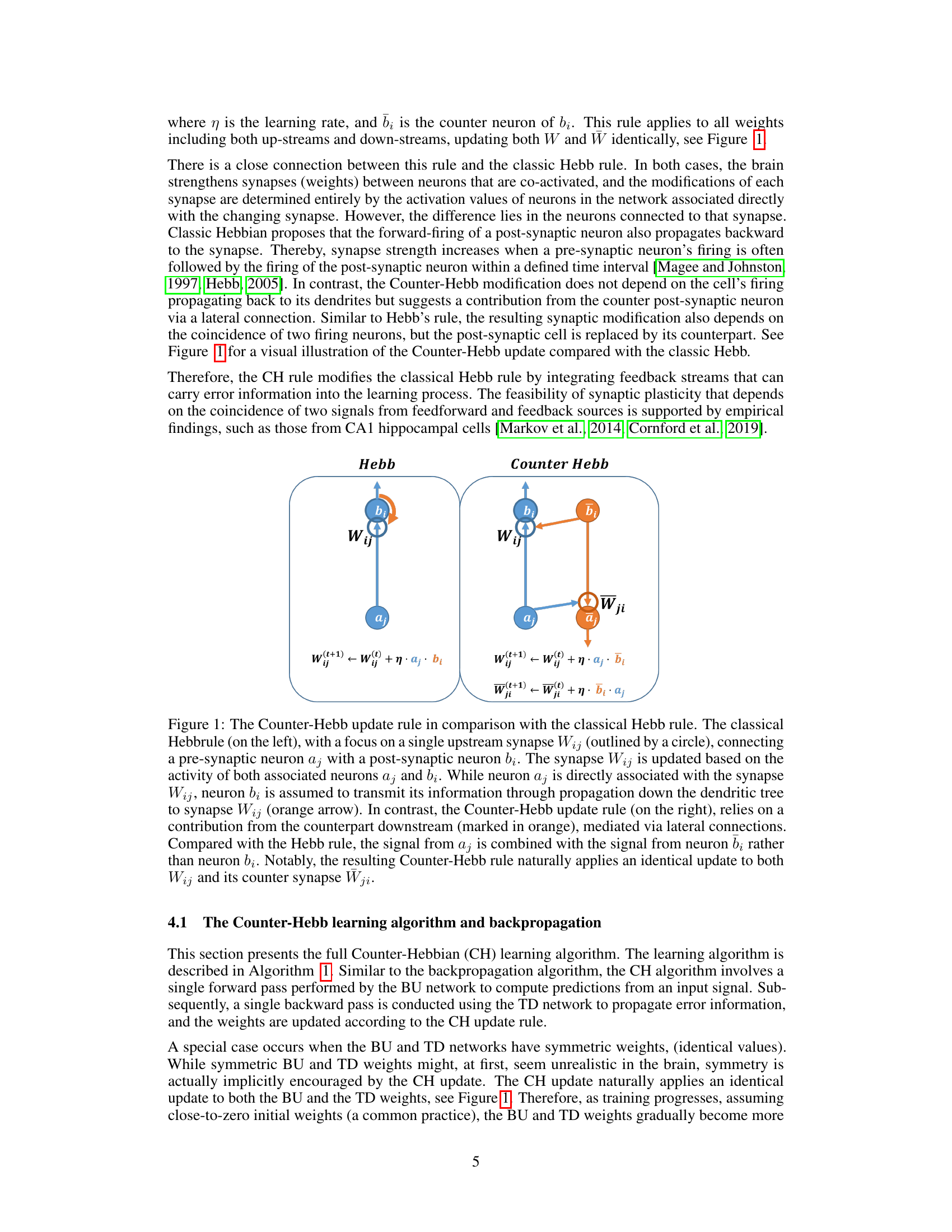

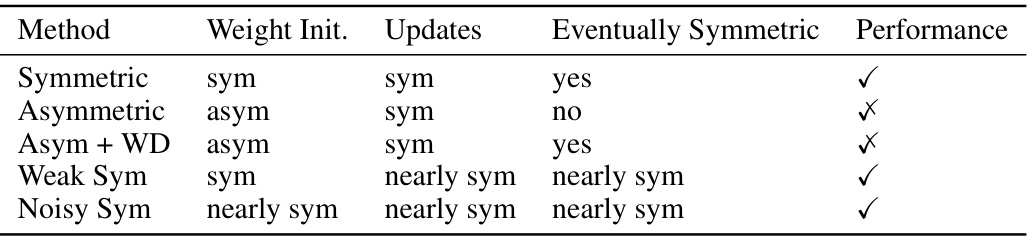

The concept of weight symmetry is crucial for understanding the trade-off between biological plausibility and computational efficiency in neural network learning. Backpropagation, a cornerstone of modern deep learning, relies on symmetric weights, making it biologically implausible. The research explores alternative learning rules, like Counter-Hebbian learning, which offer local updates and approximate backpropagation’s performance, particularly with symmetric weight initializations. However, asymmetric weights, more biologically realistic, pose a challenge to efficient learning; this study investigates the impact of weight symmetry (or lack thereof) on learning performance, revealing that initial symmetry is more critical than achieving symmetry later in training. The analysis of the effects of noise on weight symmetry provides valuable insights into the robustness of the proposed Counter-Hebbian learning method, showing its resilience to realistic biological imperfections and suggesting promising directions for biologically-inspired deep learning.

Future Directions#

Future research directions stemming from this biologically-inspired learning model could explore several key areas. Extending the model to handle more complex tasks and datasets is crucial, requiring investigation into more sophisticated attention mechanisms and potentially hierarchical architectures to better model the human visual system’s depth. Exploring the impact of different neural architectures and activation functions on the model’s performance and biological plausibility warrants attention. Improving the efficiency of the Counter-Hebb learning rule and exploring other biologically plausible learning algorithms would also advance the field. Furthermore, directly comparing the model’s performance to other cutting-edge AI methods on various benchmarks is vital. Finally, bridging the gap between theoretical models and practical applications by developing a robust, scalable, and potentially real-time implementation of the proposed system remains a significant goal.

More visual insights#

More on figures

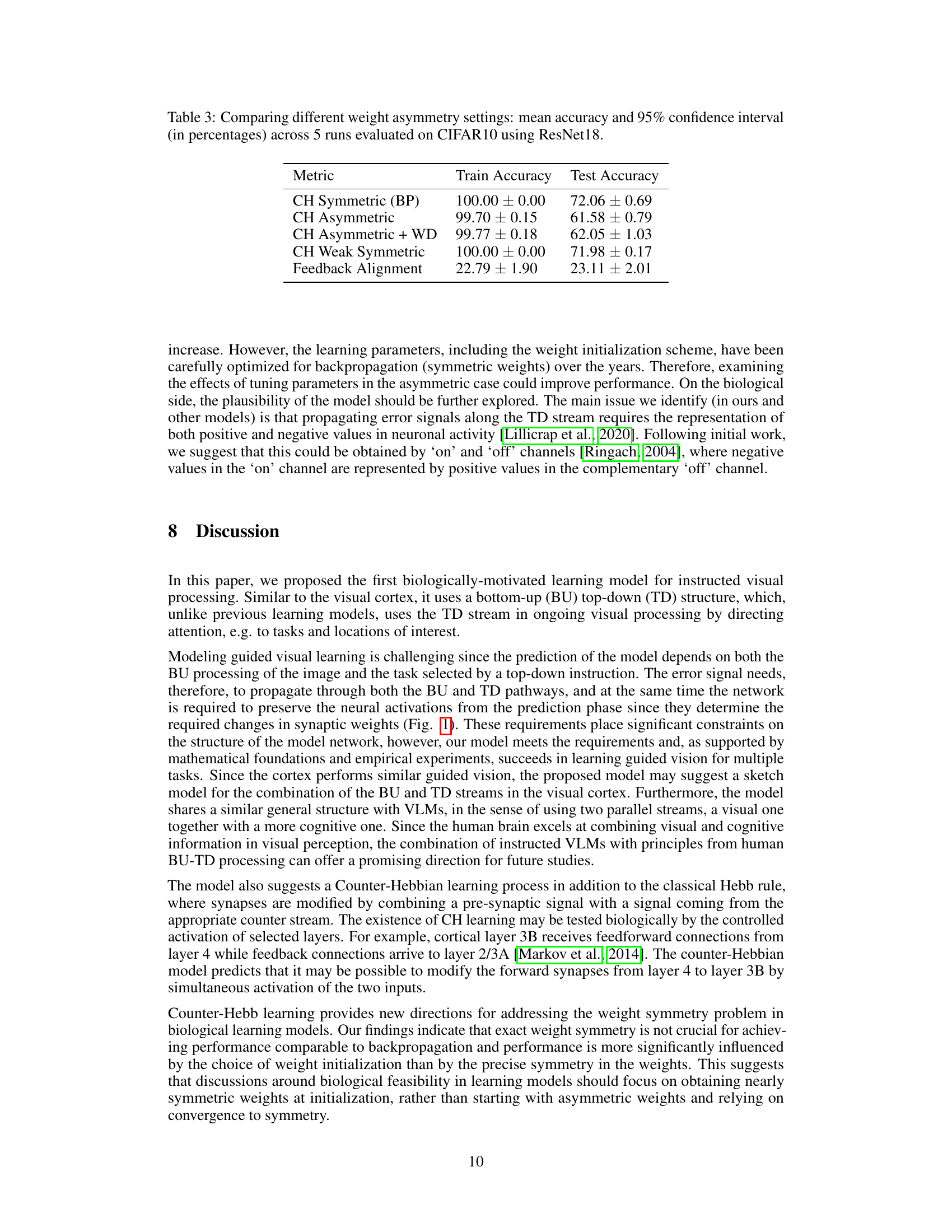

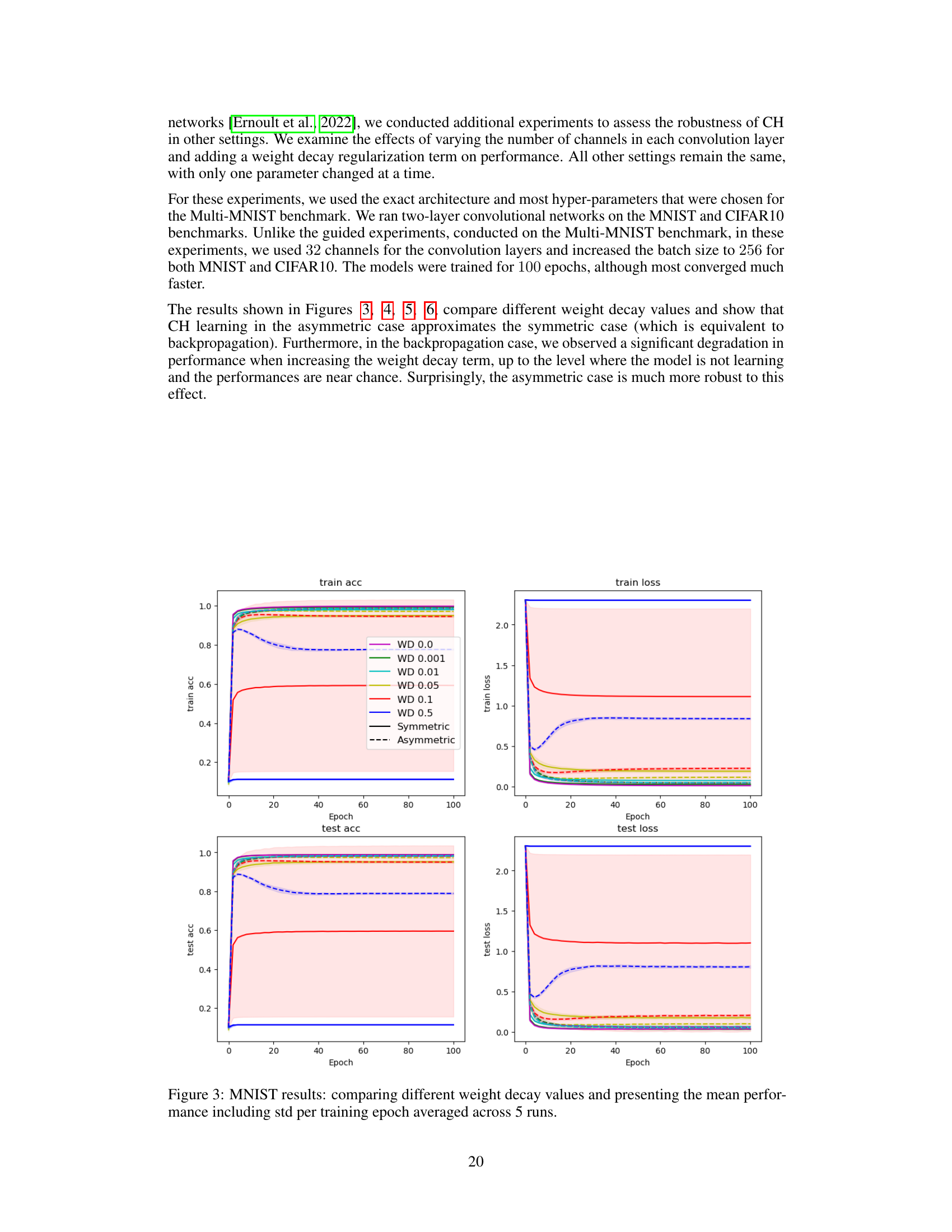

This figure illustrates the three steps of the instruction-based learning algorithm. First, a top-down (TD) pass uses the instruction head to propagate the task representation along the TD network, activating a task-specific sub-network. Next, a bottom-up (BU) pass uses the prediction head with ReLU and GaLU activation to process the input image based on the selected sub-network. Finally, another TD pass uses the prediction head with GaLU to propagate the error signal and update the weights using the Counter-Hebb rule. In inference, only the first two steps are used.

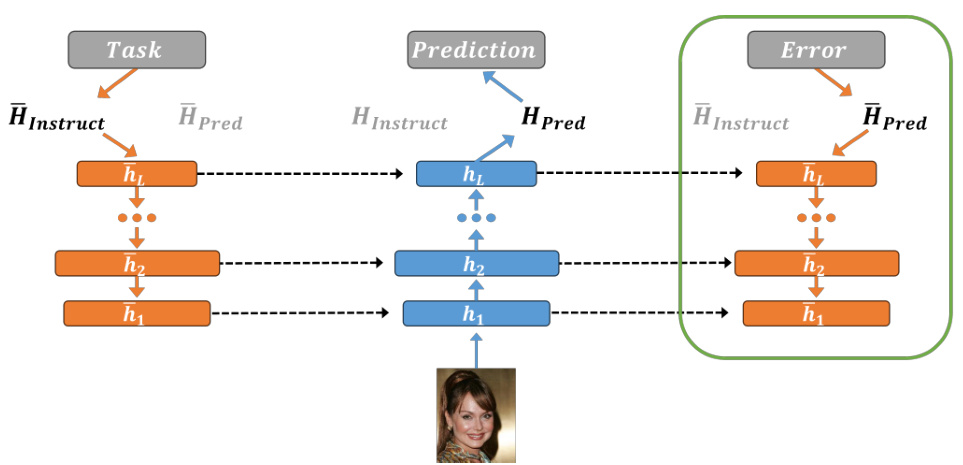

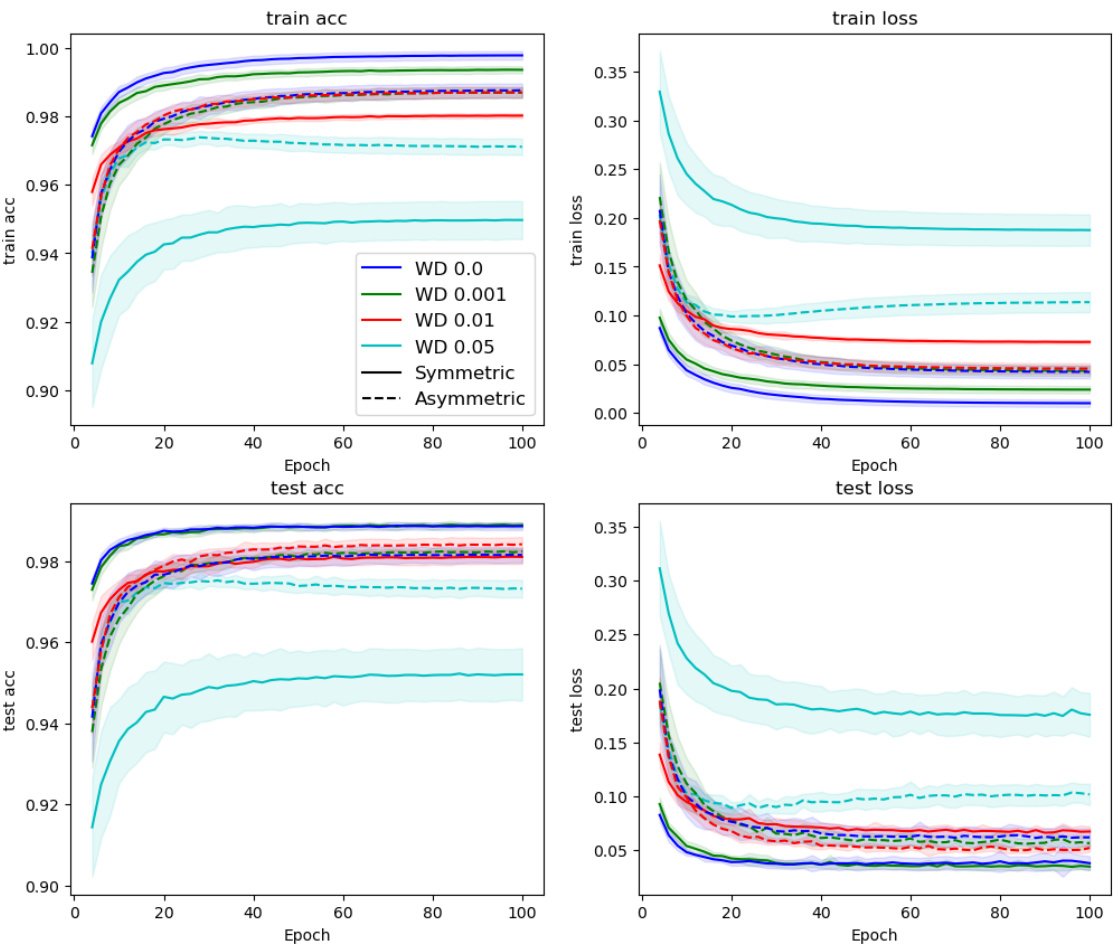

This figure shows the training and testing accuracy and loss curves for the MNIST dataset using different weight decay values. The results are averaged over five runs, with standard deviations shown as shaded areas. It illustrates the impact of weight decay on the convergence and performance of the Counter-Hebb learning algorithm, comparing it to symmetric and asymmetric weight scenarios.

This figure shows the training and testing accuracy and loss for a MNIST image classification task using different weight decay values. The results are averaged over five runs, and error bars represent the standard deviation. It compares the performance of the Counter-Hebb learning algorithm with different levels of weight decay (WD) and contrasts these results to the performance of both a symmetric (identical BU and TD weights) and asymmetric (different BU and TD weights) model, highlighting the effect of weight symmetry and weight decay on the model’s ability to learn.

This figure shows the training and testing accuracy and loss for different weight decay values on the MNIST dataset. It compares the performance of the symmetric (equivalent to backpropagation) and asymmetric versions of the Counter-Hebb learning algorithm. The shaded area represents the standard deviation across the 5 runs. The results illustrate the impact of weight decay on the convergence and generalization performance of the learning algorithm.

This figure displays the training and testing accuracy and loss for the MNIST dataset across different weight decay values. It compares the performance of symmetric and asymmetric models, providing a visual representation of how weight decay affects the learning process and model performance.

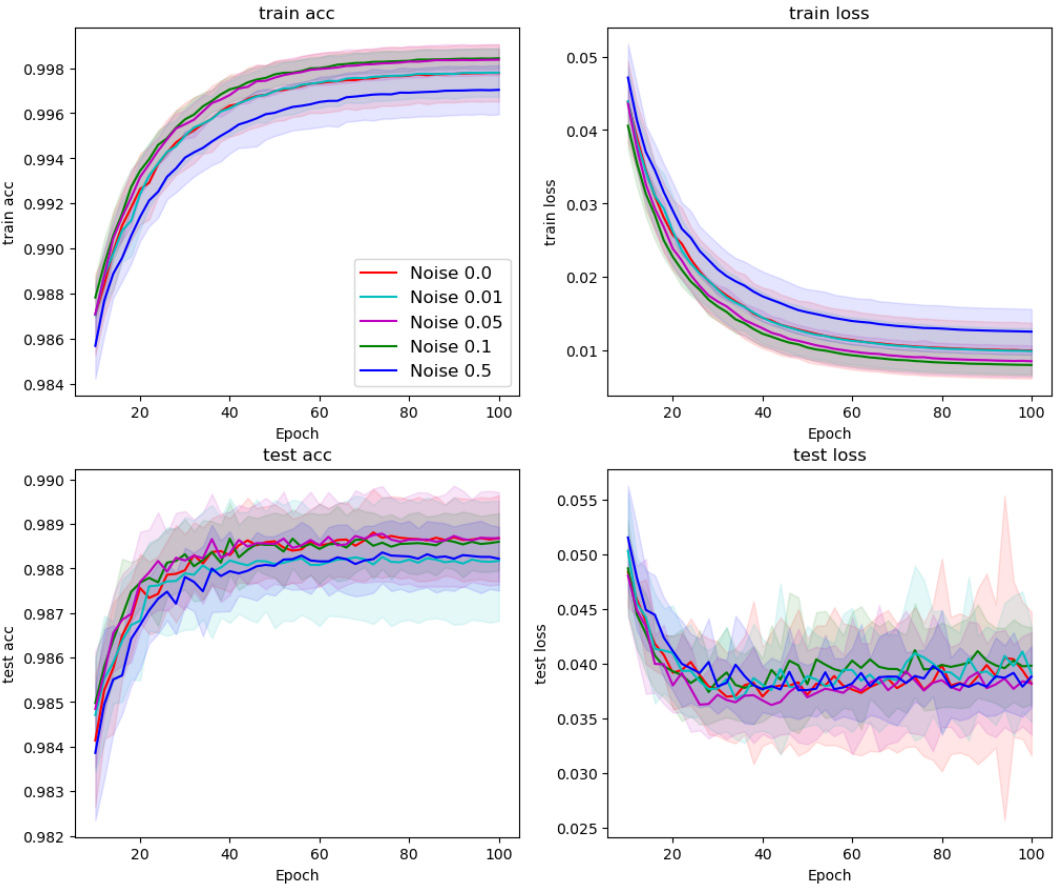

The figure shows the training and testing accuracy and loss for MNIST image classification using different weight decay values. The results are averaged over 5 runs, and the standard deviation is also shown. Different weight decay values result in different training and testing performance, with the optimal setting found somewhere in between the extremes of no weight decay (WD 0.0) and high weight decay (WD 0.5). The plots illustrate how different weight decay levels impact the learning process, showing a tradeoff between preventing overfitting and ensuring sufficient learning.

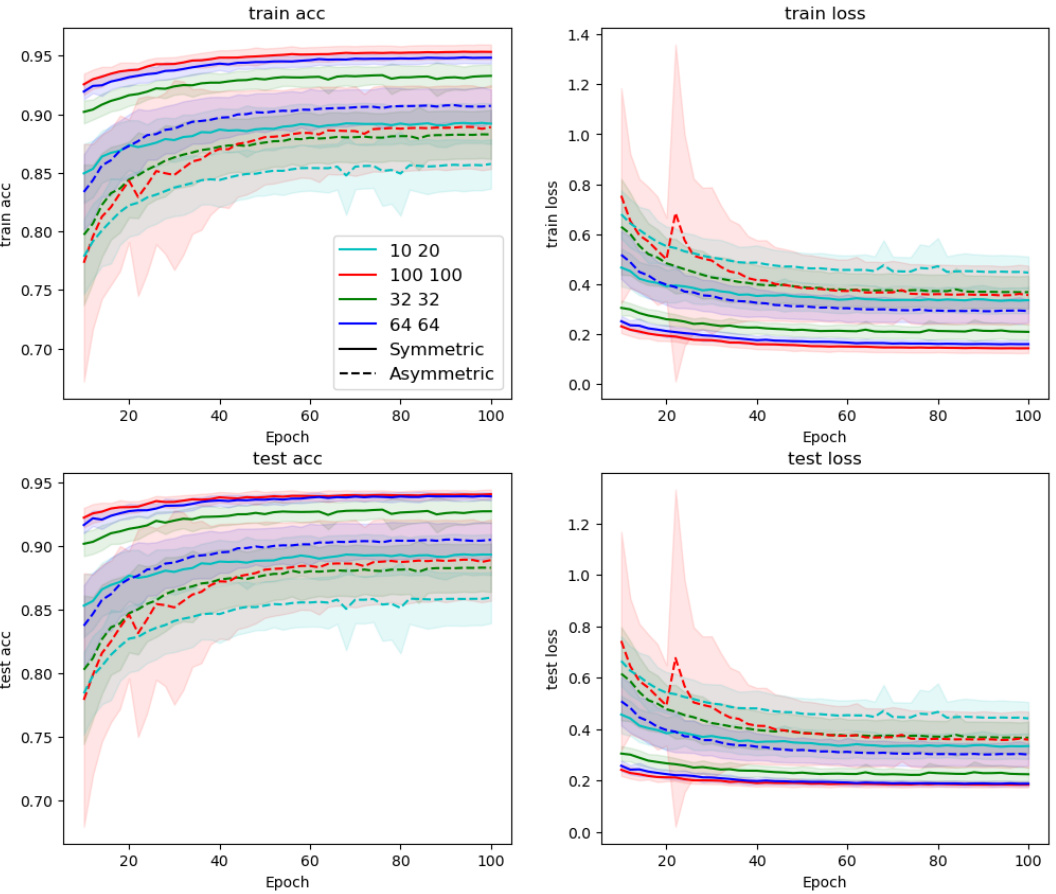

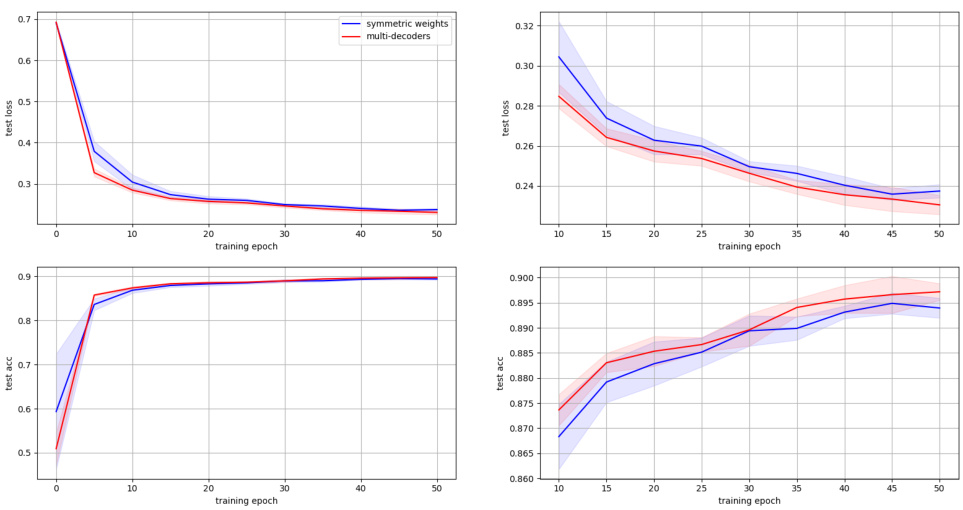

The figure displays the training and testing accuracy and loss for the Multi-MNIST dataset using the proposed Counter-Hebb learning method, comparing different numbers of channels in the first and second convolutional layers. The left plots show the training and testing accuracy over epochs, while the right plots display the corresponding training and testing loss. The results are presented for both symmetric and asymmetric weight settings, providing insights into the impact of network architecture on model performance for this multi-task learning setting.

The figure shows the training and testing accuracy and loss curves for a MNIST image classification task using a model trained with different weight decay values. The results are averaged over 5 runs, and error bars represent the standard deviation. The plot helps to visualize how different weight decay values affect the training dynamics and generalization performance of the model. Different lines represent different weight decay values, and separate plots are provided for training and testing metrics.

The figure shows the results of applying the Counter-Hebb learning algorithm to the Multi-MNIST dataset. It compares the performance of the model with varying numbers of channels in the convolutional layers. The left panel shows the test accuracy and the right shows the test loss. The results indicate how the model’s performance changes with different numbers of channels for both symmetric and asymmetric weight initializations. The results highlight the influence of model capacity and weight symmetry on the model’s ability to learn and generalize.

This figure shows the results of the Multi-MNIST experiment, comparing the performance of the model with different numbers of channels in the convolutional layers. The left plots display training and test accuracy, while the right plots show training and test loss. The different line colors represent models with varying numbers of channels in the first and second convolutional layers. The dashed lines represent models with asymmetric weights, while the solid lines depict models with symmetric weights. The figure illustrates how model capacity affects performance and highlights the impact of weight symmetry.

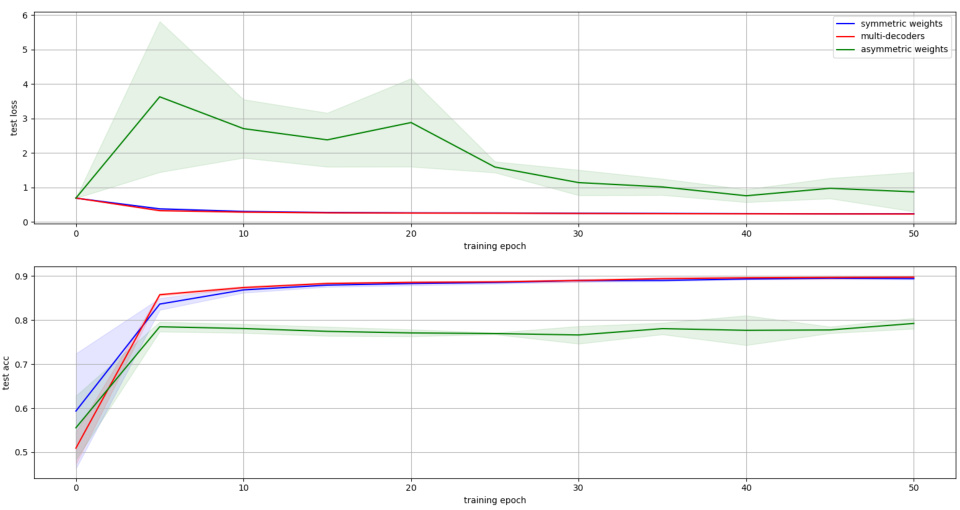

This figure shows the performance of the CelebA experiment across different weight symmetry settings. The x-axis represents the training epoch, sampled every 5 epochs. The y-axis shows the average task accuracy and loss on the test set. Three lines represent the performance of the three different symmetry settings: symmetric weights (blue), multi-decoders (red), and asymmetric weights (green). The shaded regions around the lines indicate the standard deviation. The results indicate that symmetric weights generally perform better, closely followed by the multi-decoder setup, while the asymmetric weight setting lags behind.

The figure shows the results of the CelebA experiment. The mean and standard deviation of the average task accuracy and loss on the test set are plotted for each training epoch. The results are sampled every 5 epochs. The figure helps to visualize the training process and the performance of the model over time.

This figure presents the results of experiments conducted on the MNIST dataset to evaluate the impact of different weight decay values on model performance. The plot shows the training and testing accuracy and loss over epochs. Multiple lines represent different weight decay values, and shaded regions illustrate standard deviations across 5 runs. The figure helps to understand the effect of weight decay (a regularization technique) on model performance and generalization.

This figure illustrates the instruction-based learning algorithm used in the paper. It shows how the model uses the top-down (TD) and bottom-up (BU) streams to achieve both guidance and learning in a single process. In inference, task instructions guide the visual process, while in training, the Counter-Hebb learning rule adjusts synaptic weights based on both prediction errors and task instructions.

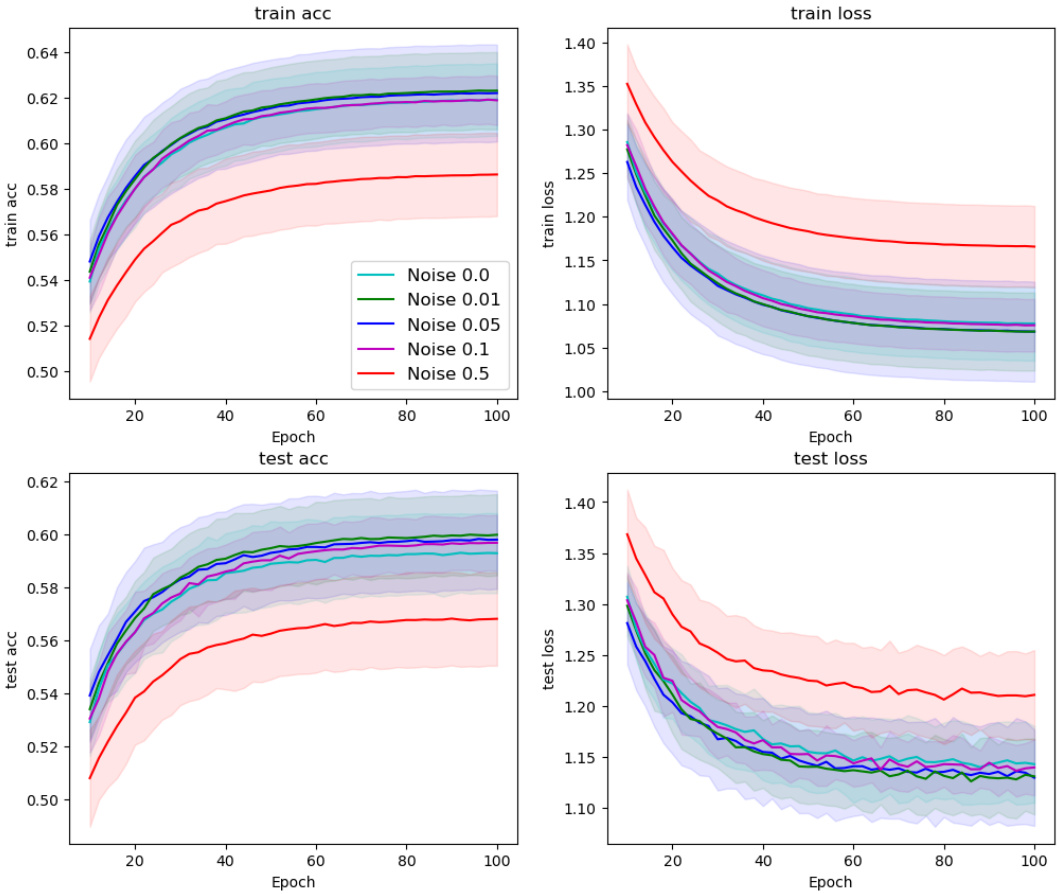

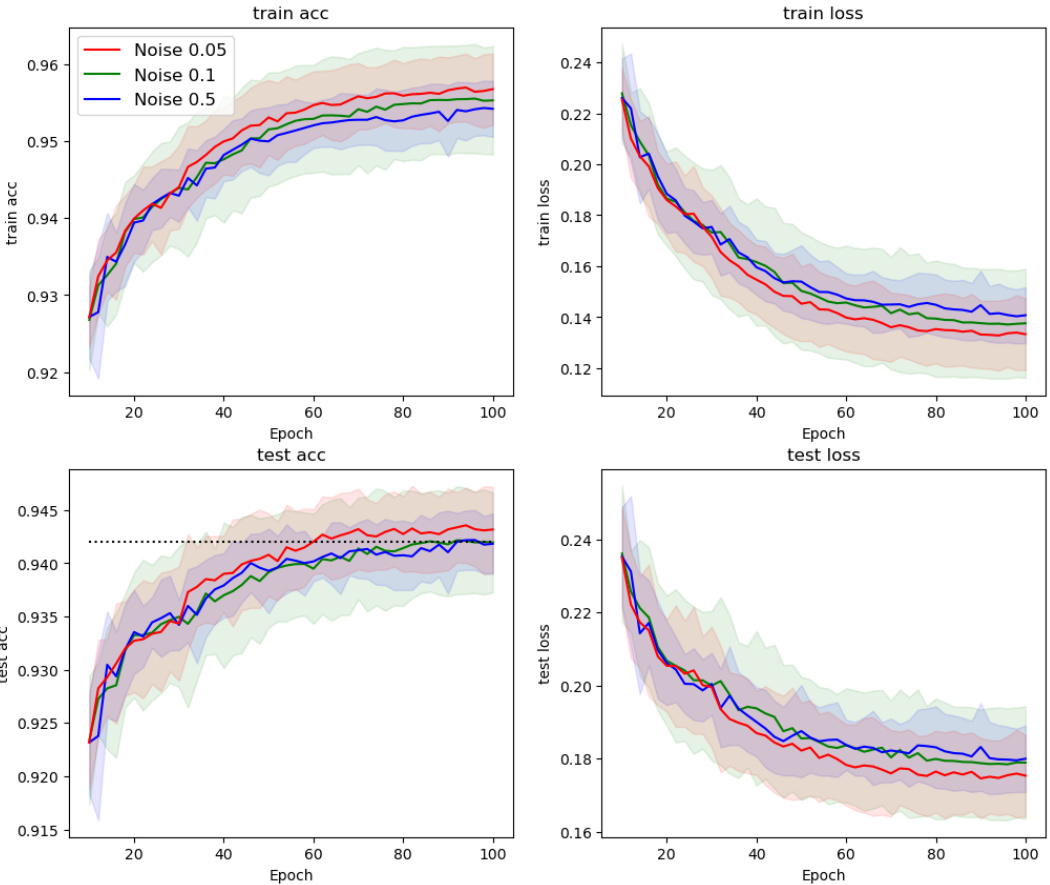

This figure shows the results of applying the Counter-Hebb learning algorithm with varying levels of noise added to the weight updates in the Multi-MNIST dataset. The x-axis represents training epochs, and the y-axis shows the average task accuracy and loss. Different colored lines represent different levels of noise (0.05, 0.1, 0.5). The dashed line represents the performance of the symmetric case, where no noise is added to the weight updates. The figure demonstrates the robustness of the Counter-Hebb learning algorithm to noise in weight updates, even with a significant amount of noise, as the performance is similar to the symmetric case. This suggests that exact weight symmetry is not critical for achieving performance comparable to backpropagation.

The figure compares the performance of different weight symmetry settings (symmetric, asymmetric, asymmetric with weight decay, noisy symmetric, weak symmetric) using ResNet18 on the CIFAR10 dataset. It shows training accuracy and loss for each setting across 5 runs, demonstrating how weight symmetry affects performance and convergence. The symmetric case serves as a baseline for comparison, while other settings explore the tradeoff between biological plausibility and accuracy. Note that Feedback alignment is also presented for comparison.

The figure compares different weight symmetry settings using ResNet18 on CIFAR10 dataset. It shows the training and testing accuracy and loss across epochs for various conditions: symmetric, asymmetric, asymmetric with weight decay, noisy symmetric, and weak symmetric. The results illustrate the impact of weight symmetry (or lack thereof) on model performance and learning dynamics.

This figure illustrates the three passes of the instruction-based learning algorithm: TD->BU->TD. The first two passes generate a prediction given an image and task, while the final TD pass (in green) is for learning. The TD network guides the BU process using task instructions. ReLU non-linearity on the task activates a task-specific sub-network within the BU network. The BU processing uses both ReLU and GaLU, with GaLU gating based on the TD network, ensuring processing focuses only on the relevant sub-network. Learning uses a final TD pass and the counter-Hebbian rule to adjust weights based on neural activity, eliminating the need for backpropagation.

More on tables

This table presents the results of unguided learning experiments on MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, and CIFAR10 datasets. It compares the performance of the proposed Counter-Hebb (CH) learning algorithm against backpropagation (BP) and other biologically-plausible learning methods. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of the test accuracy across 10 runs for each method and dataset.

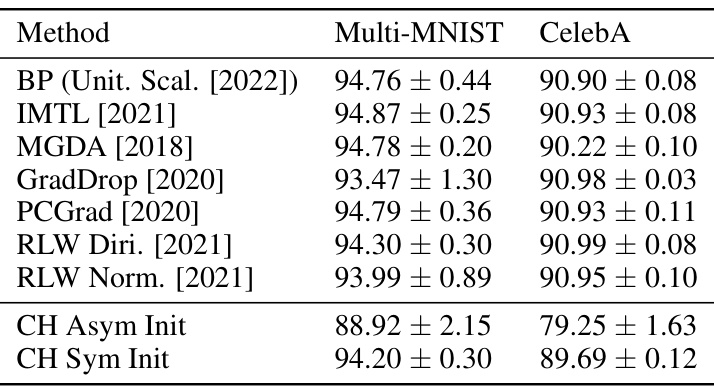

This table presents the results of guided visual processing experiments using the Counter-Hebb (CH) learning algorithm. It compares the average task test accuracy (with 95% confidence intervals) achieved by the CH method against several state-of-the-art non-biological multi-task learning methods on two benchmark datasets: Multi-MNIST and CelebA. The number of runs for each dataset is also specified.

This table compares the performance of the Counter-Hebb learning algorithm under different weight symmetry settings on the CIFAR10 dataset using a ResNet18 architecture. It shows the training and test accuracy with standard deviations for: a symmetric model (equivalent to backpropagation), an asymmetric model, an asymmetric model with weight decay, a weakly symmetric model, and a feedback alignment model. The results highlight the impact of weight symmetry on the model’s performance and learning.

This table compares the performance of the proposed Counter-Hebb (CH) learning algorithm against backpropagation (BP) and other biologically-plausible learning methods on three standard image classification benchmarks (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, and CIFAR-10). The results show the mean and standard deviation of test accuracy across 10 runs. It demonstrates the competitiveness of CH learning with other state-of-the-art approaches.

The table presents the results of unguided learning experiments on standard image classification benchmarks (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR10). It compares the performance of the proposed Counter-Hebb (CH) learning algorithm against backpropagation (BP) and other biologically-plausible learning methods. The mean and standard deviation of the test accuracy are shown for each method and dataset. Baseline results for comparison are from Bozkurt et al. (2024).

This table presents the results of unguided learning experiments on standard image classification benchmarks (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, CIFAR10). It compares the performance of the proposed Counter-Hebb (CH) learning algorithm with backpropagation (BP) and other biologically plausible learning methods. The table shows the mean and standard deviation of test accuracy across 10 runs for each method and dataset.

Full paper#