TL;DR#

Conformal Prediction (CP) is a valuable framework for uncertainty estimation but lacks theoretical connections to other uncertainty measures. Existing CP training methods are often ad-hoc and may not generalize well. This research addresses these issues by leveraging information theory to connect CP with other uncertainty notions.

The core contribution is the introduction of three novel upper bounds on intrinsic uncertainty using data processing and Fano’s inequalities. These bounds lead to principled training objectives and mechanisms to incorporate side information. Experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed methods across centralized and federated learning scenarios, showing significant improvements in prediction efficiency.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning and information theory because it bridges the gap between conformal prediction and information theory, providing novel theoretical tools for uncertainty quantification. It introduces principled training objectives that generalize previous approaches and offers a systematic way to incorporate side information, resulting in more efficient and reliable uncertainty estimations. This opens exciting avenues for further research in uncertainty quantification and other related fields.

Visual Insights#

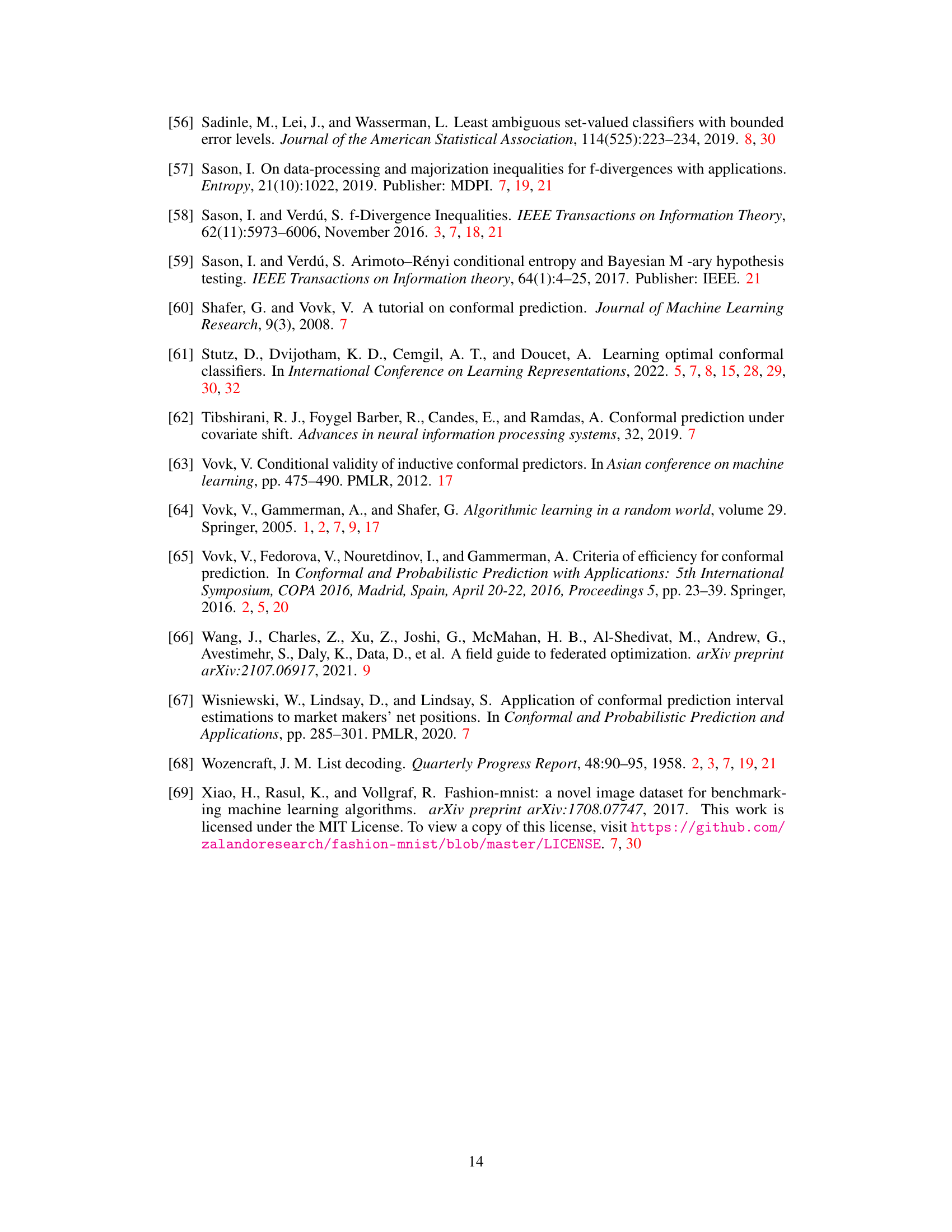

🔼 This figure shows a graphical model representing the Split Conformal Prediction (SCP) process. It details the relationships between the calibration dataset (Deal), input features (X), target variable (Y), model prediction (Ŷ), prediction set (C(X)), and the event indicating whether the true label is contained within the prediction set (E). The nodes represent variables, with square nodes representing deterministic functions and round nodes representing stochastic functions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Graphical model of SCP. Deal is a calibration set, C(X) the prediction set, Ŷ = f(X) the model prediction, and E the event {Y ∈ C(X)} . Square and round nodes are, respectively, deterministic and stochastic functions of their parents.

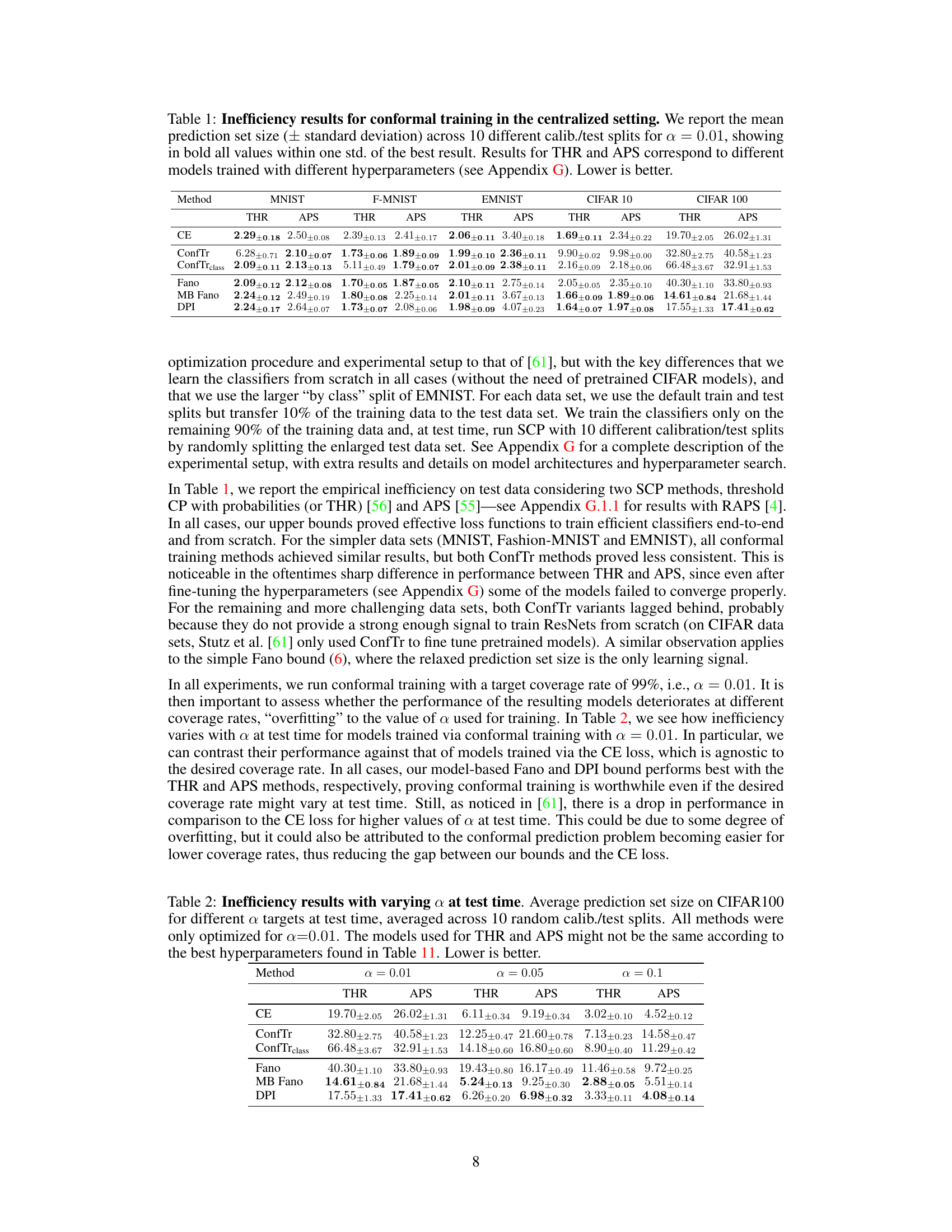

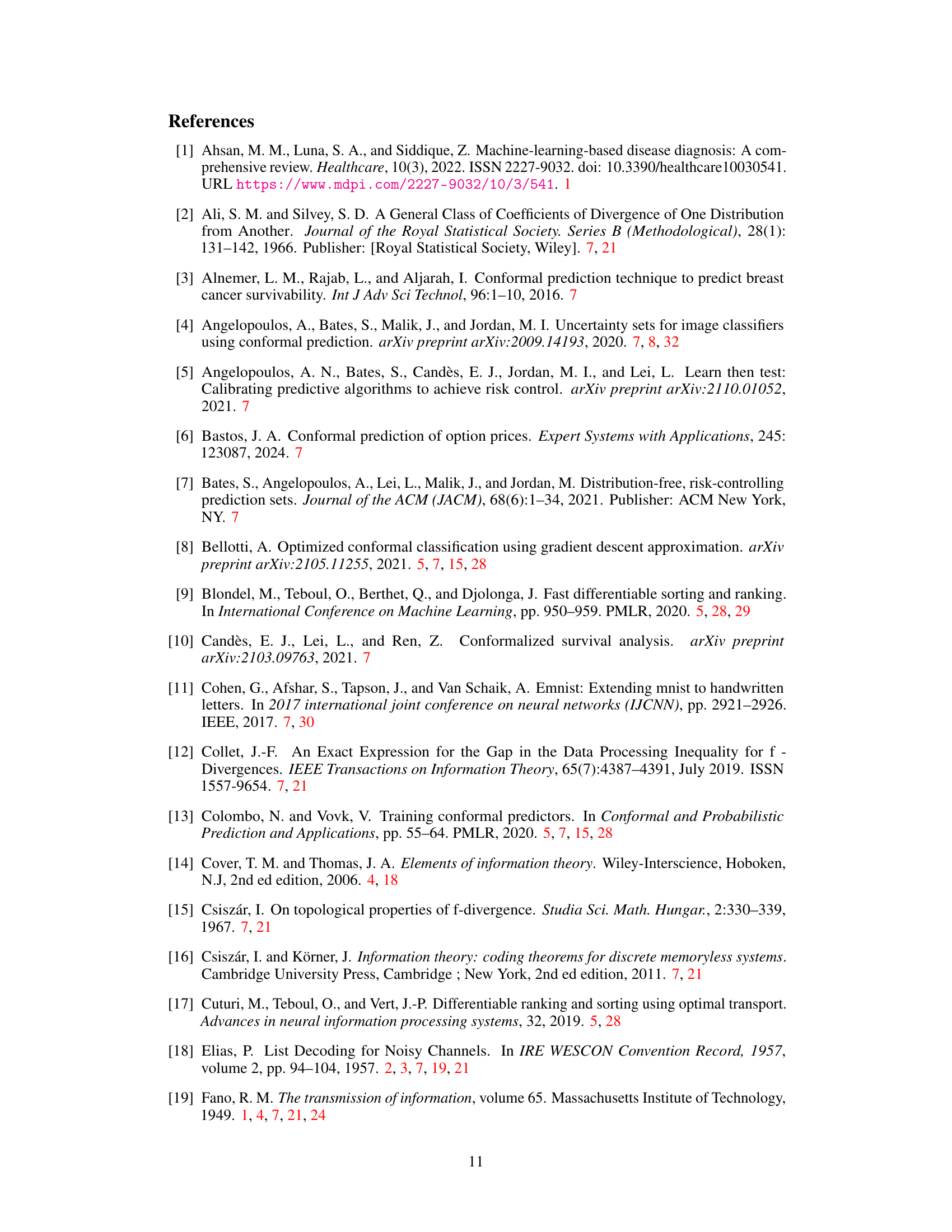

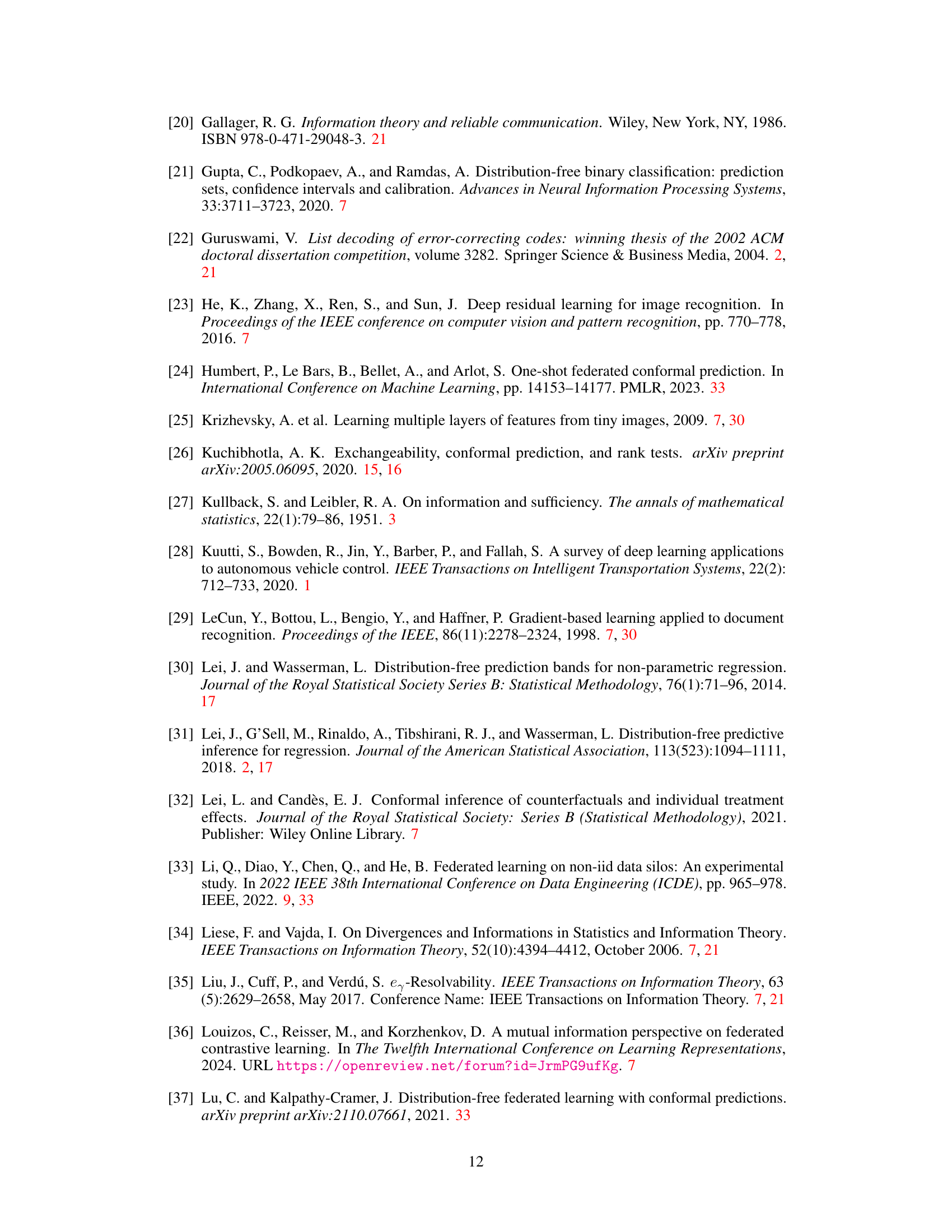

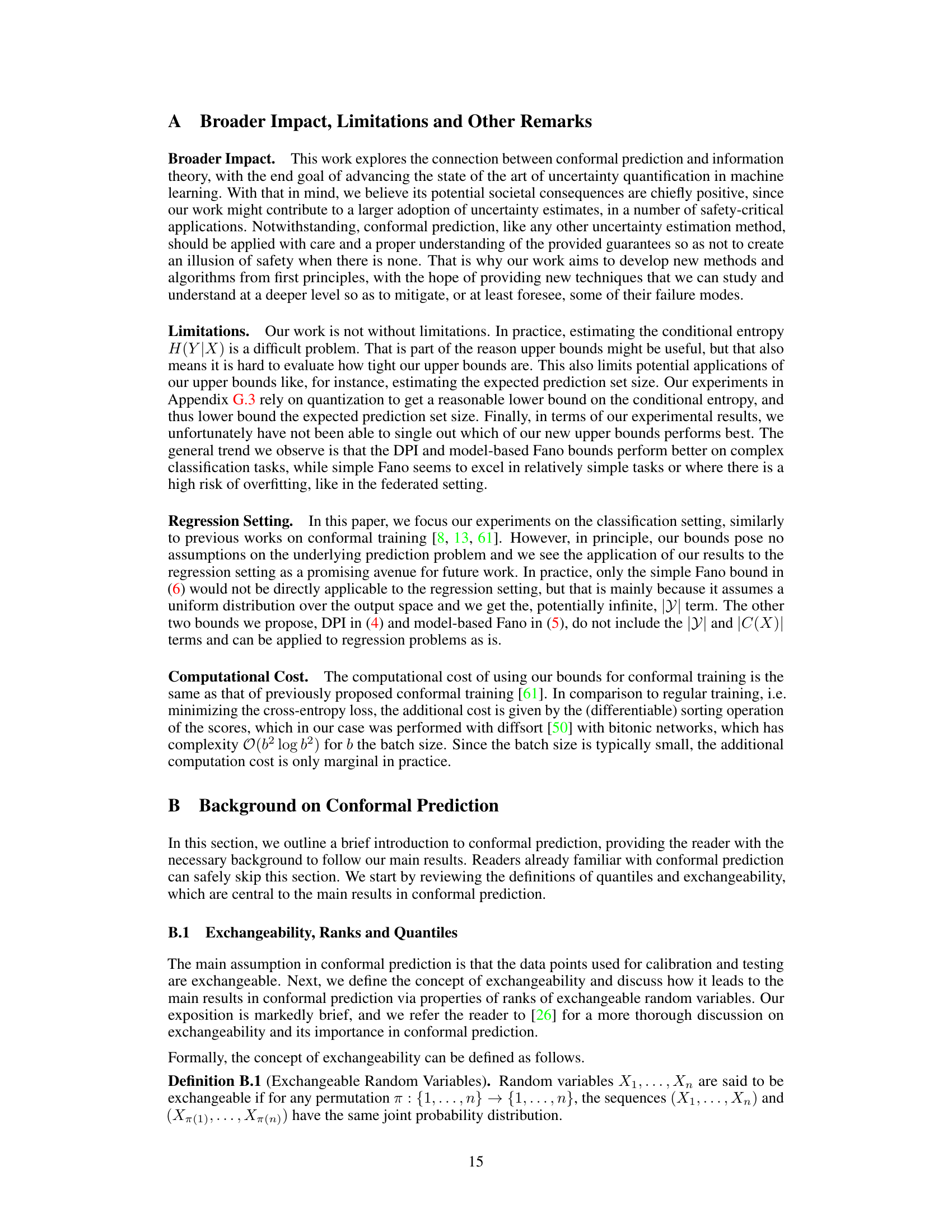

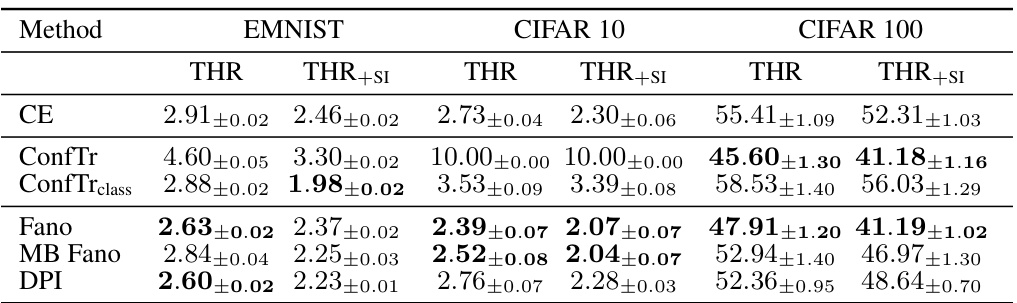

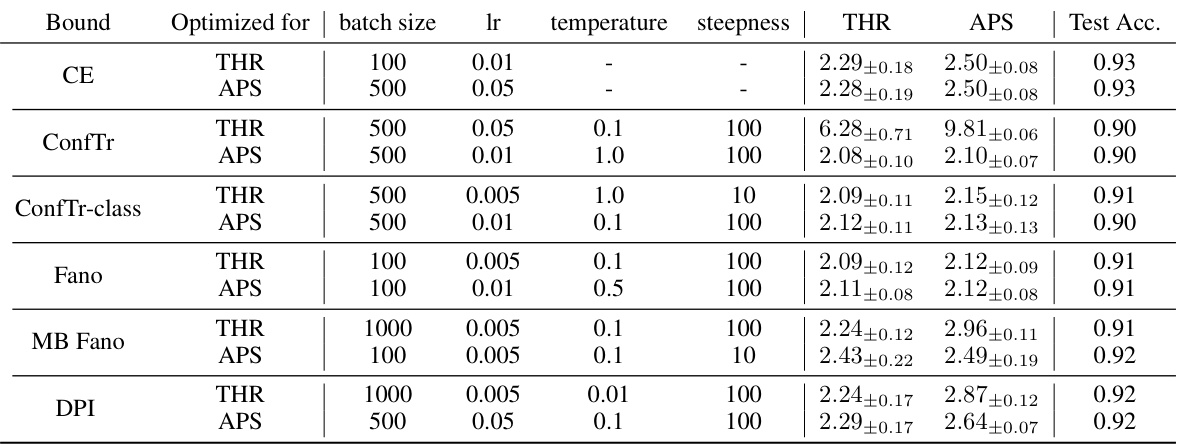

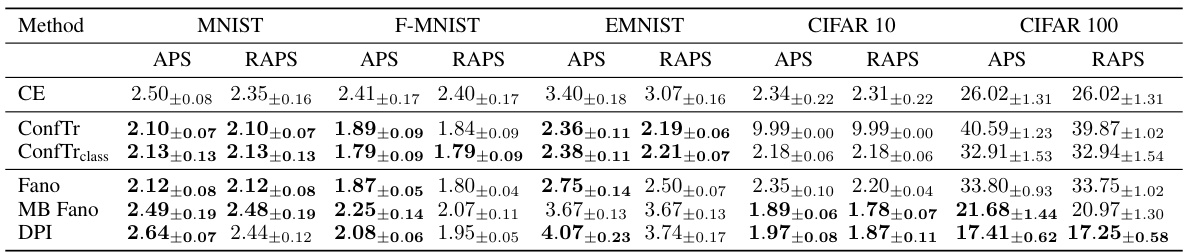

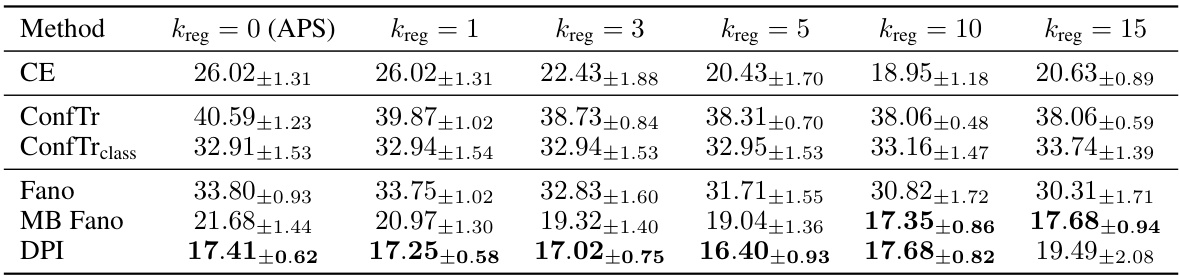

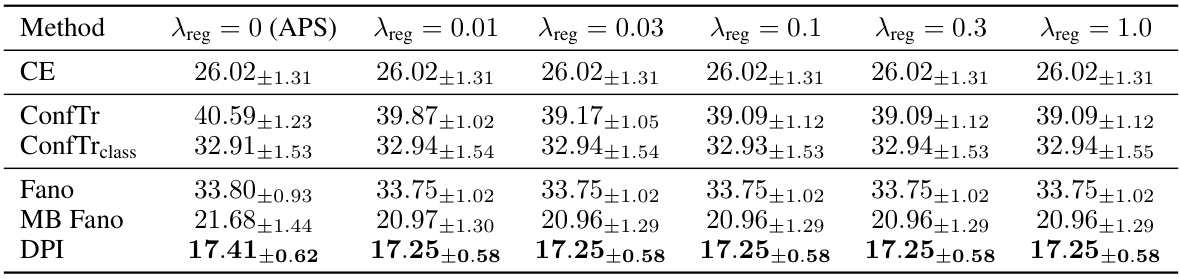

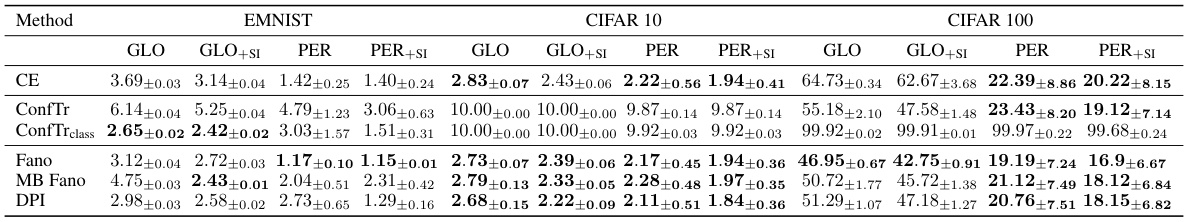

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (average prediction set size) results for various conformal training methods on five datasets: MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100. The methods compared include cross-entropy (CE) loss, ConfTr, ConfTrclass, Fano, Model-Based Fano, and DPI bounds. Two different conformal prediction methods, THR and APS, are used to calculate the inefficiency. Lower values indicate better performance, meaning smaller prediction sets which correspond to more efficient use of the model.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

In-depth insights#

Info Theory & CP#

The fusion of information theory and conformal prediction (CP) presents a powerful synergy. Information theory provides a framework for quantifying uncertainty, offering a principled way to analyze prediction set sizes in CP. Conversely, CP’s distribution-free nature complements information theory’s need for robust, assumption-free results. This intersection allows for more refined training objectives, leading to CP models with superior predictive efficiency. By leveraging information-theoretic inequalities, tighter bounds on intrinsic uncertainty can be established, providing new insights into model performance. Furthermore, this theoretical framework offers principled methods to incorporate side information, thereby improving CP’s predictive power, especially relevant in scenarios like federated learning where data is distributed among multiple devices. This connection promises advances in uncertainty quantification and model training, paving the way for more reliable and efficient machine learning systems.

Conformal Training#

The concept of ‘Conformal Training’ presents a novel approach to enhance the efficiency of conformal prediction. Instead of treating conformal prediction as a post-processing step applied to a pre-trained model, conformal training integrates conformal prediction directly into the model training process. This allows for the optimization of the model’s parameters to minimize prediction set size, thus improving the quality of uncertainty estimates. The core idea involves making the conformal prediction process differentiable, facilitating end-to-end training. This is achieved through the use of techniques like relaxing hard thresholding operations in conformal prediction using smooth approximations such as the logistic sigmoid function. By incorporating this differentiable version into the loss function, the model learns to produce predictions that are inherently more amenable to conformal prediction, resulting in tighter and more informative prediction sets. The key advantage lies in the potential to create classifiers specifically designed for efficient conformal prediction, leading to better generalization and more reliable uncertainty quantification in practical applications.

Side Info Impact#

The concept of incorporating side information to enhance conformal prediction is explored in the paper. Side information, supplementary data related to the prediction task, is leveraged to reduce uncertainty and refine prediction sets. The study demonstrates that by including relevant side information, the conditional entropy of the target variable given the inputs is reduced, resulting in more precise and efficient predictions. This is achieved by utilizing a Bayesian approach to update the predictive model with side information, effectively improving predictive efficiency. The results highlight the potential of this approach in scenarios where side information is readily available, such as in federated learning. The method is theoretically sound, incorporating information-theoretic inequalities, and is validated empirically across various datasets and settings. A key advantage is the seamless integration of side information, requiring only minimal modifications to the standard conformal prediction pipeline. The impact analysis shows improved prediction accuracy and reduced average prediction set size when side information is incorporated. The effectiveness of using side information is particularly prominent in settings with complex data dependencies and challenges such as data heterogeneity and limited data availability in the federated learning settings.

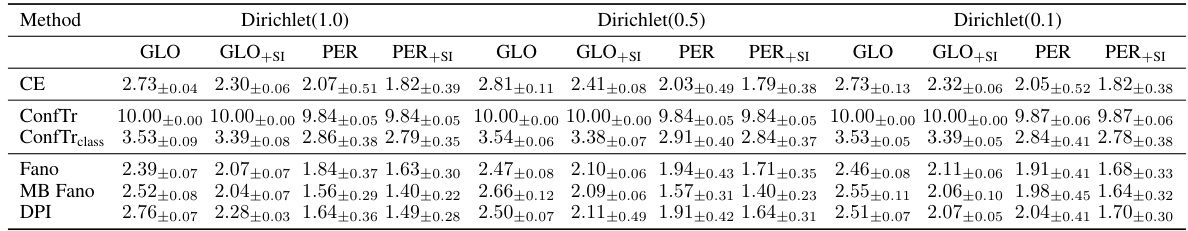

Federated Learning#

The section on Federated Learning (FL) in this research paper explores the application of conformal prediction in distributed settings, where data resides on multiple devices. A key challenge addressed is training a global model while maintaining data privacy; the authors propose using the device ID as side information. This allows the incorporation of local data characteristics into the global model, improving prediction efficiency without direct data sharing. The authors demonstrate that the information-theoretic framework of conformal prediction provides a theoretically sound basis for this approach. They also investigate the impact of data heterogeneity among devices on model performance. The experiments highlight the effectiveness of incorporating side information in the federated setting, showing improved predictive efficiency compared to traditional centralized conformal training. The use of side information is particularly advantageous in scenarios with strict data privacy requirements, making this methodology particularly relevant for FL and similar privacy-sensitive settings.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could explore several promising avenues. Extending the theoretical framework to regression tasks would broaden the applicability of the information-theoretic perspective on conformal prediction. Investigating tighter upper bounds on conditional entropy is crucial to improve the accuracy of uncertainty quantification. Developing more robust and efficient conformal training algorithms that are less sensitive to hyperparameter choices is also important for practical application. Finally, exploring the use of side information in more complex settings like federated learning with non-IID data would unlock the potential of this technique in diverse real-world scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on tables

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency results for different conformal training methods in a centralized setting. Inefficiency is measured as the average prediction set size. The results are averaged over 10 different calibration and test data splits, using a target error rate (α) of 0.01. The table shows results for two different conformal prediction methods (THR and APS), each with different model hyperparameters, and several different training objectives (CE, ConfTr, ConfTrclass, Fano, MB Fano, DPI). Lower values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

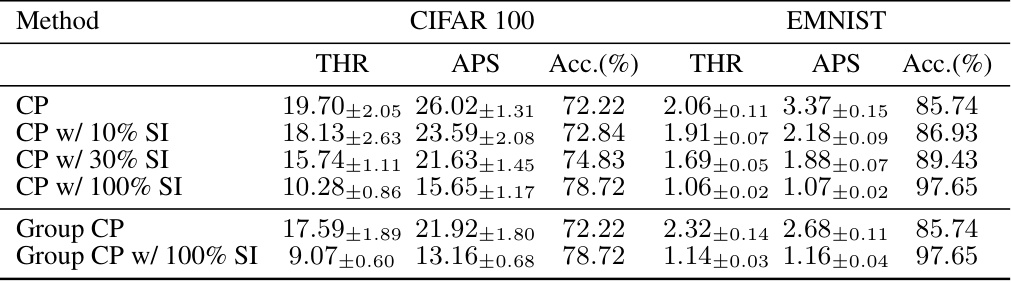

🔼 This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the impact of side information on the efficiency of conformal prediction. Two different scenarios are tested: standard split conformal prediction (SCP) and group-balanced CP (Mondrian CP). The results show how adding side information, whether 10%, 30%, or 100% of the data, affects the inefficiency (measured by the average prediction set size) of both THR and APS methods for both CIFAR100 and EMNIST datasets.

read the caption

Table 3: Inefficiency results with side information. We report the mean prediction set size (± std.) across 10 different calib./test splits for a = 0.01. The side information is the superclass assignment for CIFAR100 and whether the class is a digit / uppercase letter / lowercase letter for EMNIST.

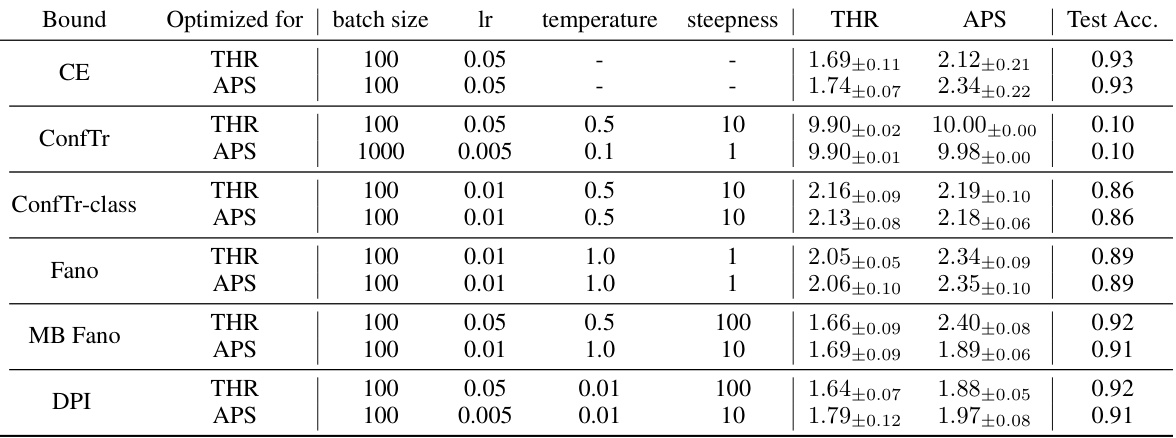

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (average prediction set size) results for conformal training in a federated learning setting, using the THR method. The results are shown for different conformal training objectives (CE, ConfTr, ConfTrclass, Fano, MB Fano, DPI) with and without side information (+si). The table shows the mean and standard deviation across 10 different calibration/test splits for a target error rate (alpha) of 0.01. Lower values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 4: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the federated setting with THR. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) of the global federated model across 10 different calib./test splits for a = 0.01 and using THR. We use +si to indicate the inclusion of side information. We show in bold all values within one standard deviation of the best result. Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (average prediction set size) of different conformal prediction methods for training classifiers in a centralized setting. Results are shown for multiple datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100), using two different conformal prediction methods (THR and APS). Lower values indicate better performance (smaller prediction sets). Bold values indicate results within one standard deviation of the best result for each dataset and method. Hyperparameter settings are explained in Appendix G.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency results for different conformal training methods in a centralized setting. Inefficiency is measured as the average prediction set size, with lower values indicating better performance. The results are averaged over 10 different train/test splits with a target error rate of 1%. The table compares various methods including the cross-entropy loss (CE) and the proposed methods (DPI, Fano, MB Fano). Different models (THR and APS) with various hyperparameters are used for comparison, with details found in Appendix G.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the results of conformal training experiments conducted in a centralized setting. It compares the average prediction set size, a measure of inefficiency, across various methods (CE, ConfTr, ConfTr-class, Fano, MB Fano, DPI). The experiment used a significance level of α = 0.01, and the results are averaged across 10 different train-test splits. The table shows that different methods result in different efficiency levels, with lower values indicating better performance. The THR and APS results reflect the use of different model hyperparameters.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (mean prediction set size) of different conformal prediction training methods on five datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100). It compares the performance of using cross-entropy loss (CE), ConfTr, ConfTr-class, and the proposed methods (Fano, MB Fano, DPI) for training classifiers. The results are averaged across 10 different train/test splits, and values within one standard deviation of the best result are highlighted. THR and APS denote different model architectures with varied hyperparameters.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (mean prediction set size) of different conformal prediction training methods on five datasets: MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100. The inefficiency is calculated across ten different calibration/test splits with a target coverage rate of 99% (α=0.01). Results are shown for two different conformal prediction methods, THR (threshold with probabilities) and APS (adaptive prediction sets), with different hyperparameters indicated by THR and APS. Lower values indicate better performance (more efficient prediction sets).

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (average prediction set size) of different conformal prediction training methods on five datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100). The results are shown for two different conformal prediction methods (THR and APS) and various training objectives, including cross-entropy and the information-theoretic bounds introduced in the paper. Lower values indicate better efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (average prediction set size) of different conformal prediction methods on five datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100). Inefficiency is calculated across 10 different train-test splits for a target error rate of α = 0.01. The methods compared include using cross-entropy loss, ConfTr, ConfTr-class, and three new upper bounds proposed in the paper (DPI, Fano, MB Fano). THR and APS represent results from different models trained with different hyperparameters, and bold values indicate results within one standard deviation of the best performance. Lower numbers are better indicating higher efficiency.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (average prediction set size) results for different conformal prediction training methods on five datasets: MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100. The methods compared include cross-entropy (CE) loss, ConfTr, ConfTrclass, and the three information-theoretic bounds proposed in the paper (Fano, MB Fano, DPI). Results are shown for two conformal prediction methods, THR and APS. Lower inefficiency values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the results of conformal training experiments conducted in a centralized setting. The mean prediction set size, a measure of inefficiency, is reported for ten different train/test splits, using a target error rate (α) of 0.01. The results are shown for different conformal training methods, including two versions of ConfTr and three new information-theoretic bounds introduced in the paper. For the THR and APS methods, results from different models trained with varying hyperparameters are included (details in Appendix G). Lower values indicate higher efficiency (smaller prediction sets).

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the results of conformal training experiments conducted in a centralized setting. The table shows the average prediction set size (a measure of inefficiency, with lower values indicating better performance) for various methods across 10 different calibration/test dataset splits. The methods are compared for different datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100). Results for THR and APS (different models) highlight the impact of hyperparameter tuning.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (average prediction set size) results for different conformal training methods on five datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100). The methods compared include cross-entropy loss (CE), ConfTr, ConfTrclass, Fano, Model-Based Fano, and DPI bounds, each using two different conformal prediction methods (THR and APS). Lower values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (average prediction set size) of different conformal prediction training methods on several datasets. Inefficiency is a measure of how concise the prediction sets are. The results are averages across 10 separate train/test splits and the standard deviations are reported for each experiment to show the variability. Lower values of inefficiency are better, indicating more concise and informative prediction sets. Different model types (THR, APS) and hyperparameter settings are used for more comprehensive evaluation.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (mean prediction set size and standard deviation) of different conformal prediction training methods across various datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, CIFAR-100). The methods compared include cross-entropy (CE) loss, ConfTr, ConfTrclass, Fano, model-based Fano, and DPI bounds. The results are obtained from 10 different calibration/test splits, with bold values indicating results within one standard deviation of the best result. THR and APS represent different models trained with different hyperparameters, detailed in Appendix G.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

🔼 This table presents the inefficiency (mean prediction set size) results for different conformal training methods on five datasets (MNIST, Fashion-MNIST, EMNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100). It compares the performance of using cross-entropy loss, ConfTr, ConfTrclass, and three information-theoretic upper bounds (DPI, Fano, MB Fano) as training objectives. The results are averaged over 10 different train/test splits, and statistically significant results are highlighted.

read the caption

Table 1: Inefficiency results for conformal training in the centralized setting. We report the mean prediction set size (± standard deviation) across 10 different calib./test splits for α = 0.01, showing in bold all values within one std. of the best result. Results for THR and APS correspond to different models trained with different hyperparameters (see Appendix G). Lower is better.

Full paper#