TL;DR#

Federated learning (FL) applied to large language models (LLMs) faces challenges due to heterogeneous client resources and data distributions. Traditional FL methods suffer from a “bucket effect,” limiting performance to the capabilities of least-resourced participants. This restricts the potential of clients with ample resources.

This paper introduces FlexLoRA, a novel aggregation scheme that dynamically adjusts local LORA ranks, allowing for dynamic adjustment of local LORA ranks. It fully leverages heterogeneous client resources by synthesizing a full-size LoRA weight from individual client contributions and using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) for weight redistribution. Experiments across thousands of clients performing heterogeneous NLP tasks validate FlexLoRA’s efficacy. The federated global model consistently outperforms state-of-the-art FL methods in downstream NLP tasks across various heterogeneous distributions.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in federated learning and large language models because it presents FlexLoRA, a novel approach that significantly improves the efficiency and performance of federated fine-tuning for LLMs. It addresses the challenges of heterogeneous data and resources across clients, offering a practical and effective solution for real-world applications. The theoretical analysis and extensive empirical results provide valuable insights for further research and development in this rapidly evolving field. The proposed method is easily integrable with existing frameworks and opens new avenues for cross-device, privacy-preserving federated tuning of LLMs.

Visual Insights#

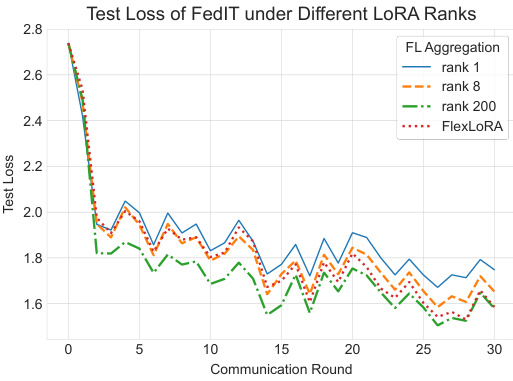

🔼 This figure compares the test loss of FlexLoRA and FedIT (a baseline federated learning method) across different communication rounds. Three different LoRA ranks (1, 8, and 200) are used for both methods. The graph shows that FlexLoRA demonstrates adaptability even in scenarios with highly imbalanced client resources (extreme heavy tail), where the majority of clients have a high LoRA rank, while a few have a low rank. As the number of communication rounds increases, FlexLoRA’s performance gets closer to FedIT’s performance at the highest LoRA rank (200).

read the caption

Figure 1: Test loss of FlexLoRA and FedIT [43] across communication rounds under LORA ranks of 1, 8, and 200. FlexLORA demonstrates adaptability in an “extreme heavy tail” scenario and increasingly aligns with the performance of FedIT at the highest LORA rank as rounds progress. Implementation details are in Appendix A.

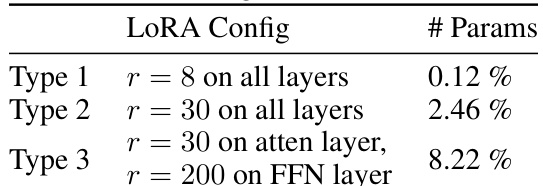

🔼 This table lists four different LoRA configurations used to create heterogeneous resource distributions in the experiments. Each configuration specifies the rank (r) of the LoRA matrices used for fine-tuning different layers of the model. Type 1 uses a low rank (r=8) on all layers, Type 2 uses a medium rank (r=30) on all layers, Type 3 uses a medium rank on attention layers and a high rank (r=200) on feed-forward network (FFN) layers, and Type 4 uses a high rank (r=200) on all layers. The percentage of parameters tuned by each configuration relative to the total number of parameters is also provided. This variation in ranks and parameter counts simulates the diversity of resources available in real-world federated learning settings.

read the caption

Table 1: The LoRA configurations that compose heterogeneous resource distributions, detailed in Figure 3.

In-depth insights#

FlexLoRA: A New FL Scheme#

FlexLoRA presents a novel federated learning (FL) scheme designed to address the limitations of existing methods in efficiently fine-tuning large language models (LLMs). Unlike traditional FL approaches that suffer from the “bucket effect,” restricting resource-rich clients to the capabilities of the least-resourced, FlexLoRA allows dynamic adjustment of local LoRA ranks. This enables clients to fully leverage their resources, contributing models with broader, less task-specific knowledge. The key innovation lies in its heterogeneous aggregation scheme, synthesizing a full-size LoRA weight from individual client contributions of varying ranks, then employing Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) for weight redistribution. This ensures that all clients, regardless of resource capacity, contribute effectively to a more generalized global model, leading to improved downstream task performance and robust generalization to unseen tasks and clients. FlexLoRA’s simplicity and plug-and-play nature make it easily adaptable to existing LoRA-based FL methods, enhancing their effectiveness and providing a practical path toward scalable, privacy-preserving federated tuning for LLMs.

Heterogeneous FL Tuning#

Heterogeneous Federated Learning (FL) tuning presents a significant challenge in adapting Large Language Models (LLMs) to diverse client scenarios. Data heterogeneity, where clients possess vastly different datasets, and resource heterogeneity, encompassing variations in computational power and network bandwidth, hinder the efficacy of standard FL approaches. Strategies must account for these disparities to prevent the ‘bucket effect’, where powerful clients are bottlenecked by weaker ones, and to ensure all clients contribute effectively. Dynamic rank adaptation within parameter-efficient fine-tuning methods is crucial, enabling clients with more resources to employ larger models while maintaining generalization across varied tasks. Successful strategies would need to synthesize contributions from heterogeneous clients into a coherent global model, possibly leveraging techniques such as weighted averaging and singular value decomposition (SVD) to address the varying dimensionality of local model updates. The ideal solution would balance the benefits of task-specific local tuning with the necessity of maintaining robust global generalization.

SVD Weight Redistribution#

The concept of “SVD Weight Redistribution” within a federated learning framework for large language models (LLMs) is crucial for efficiently leveraging heterogeneous client resources. Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) is employed to decompose the aggregated global LoRA weight, which is initially a synthesis of various locally-trained weights with potentially different ranks. This decomposition allows for a more efficient and controlled redistribution of information back to individual clients, thereby addressing the “bucket effect” prevalent in traditional federated learning where low-resource clients constrain the model’s overall performance. The redistribution based on SVD enables clients to receive a tailored subset of the global knowledge that aligns with their computational capabilities, ensuring optimal utilization of available resources. The process thus allows the global model to absorb information from high-resource clients without negatively impacting the performance of low-resource clients. This dynamic adaptation via SVD is a key innovation for improving the effectiveness and scalability of federated LLM fine-tuning in heterogeneous environments.

Generalization Analysis#

A robust generalization analysis section in a machine learning research paper is crucial. It should not only present theoretical bounds but also provide empirical evidence supporting the claims. A rigorous mathematical framework, such as extending Baxter’s model, is vital for establishing theoretical guarantees on generalization performance. Key assumptions, like Lipschitz continuity of loss functions, must be clearly stated and justified. The analysis should demonstrate how model characteristics, such as the rank of low-rank matrices in the case of parameter-efficient fine-tuning, influence generalization error. The analysis should ideally connect these theoretical findings to empirical results by showing how different model configurations (e.g., various LORA ranks) lead to observable differences in generalization performance across diverse datasets and unseen tasks. Ideally, it should explicitly address the impact of data heterogeneity and client resource limitations on generalization. This would involve demonstrating how the approach handles the variability in data distributions and client resources, and how it mitigates potential issues like the “bucket effect” in federated learning settings. A strong generalization analysis section should offer a thorough and persuasive case for the model’s ability to generalize effectively beyond the training data.

Future Work: Scaling FL#

Future work in scaling federated learning (FL) for large language models (LLMs) presents exciting opportunities and significant challenges. Addressing the inherent heterogeneity of client devices and network conditions is crucial. This includes developing more robust aggregation techniques that handle varying computational capabilities and data distributions effectively. Improving communication efficiency is also paramount, as LLMs demand substantial bandwidth. Strategies like efficient compression algorithms or model-agnostic meta-learning could offer solutions. Beyond these technical hurdles, research into privacy-preserving techniques that safeguard sensitive user data within the distributed setting remains a key priority. The exploration of decentralized or blockchain-based consensus mechanisms could further improve robustness and fairness. Developing more sophisticated incentive mechanisms to encourage wide participation from a diverse set of clients could enhance the overall effectiveness and scalability of the FL system. Finally, exploring the integration of FL with other promising areas such as transfer learning and continual learning would accelerate progress toward achieving truly scalable and practical FL for LLMs.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the FlexLoRA aggregation scheme. The server side first averages the local LoRA weights from multiple clients, each with potentially different ranks (r1 < r2 < … < rj). These local weights are obtained after individual clients perform local training with their own data and tasks (Translation, Sentiment Analysis, Q&A are shown as examples). Then, a full-size LoRA weight is synthesized from these averaged weights. This full-size LoRA is then decomposed using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) before being distributed back to each client to update their local models. The difference in local rank is used to balance the trade-off between task-specific optimization and generalization. This allows clients with more resources to contribute more broadly generalized knowledge.

read the caption

Figure 2: Illustration of FlexLoRA. The server initially constructs a full-size LoRA weight, which is then averaged across client-contributed weights with different ranks. The aggregated global weights are decoupled via SVD and sent back to clients.

🔼 This figure illustrates the composition of heterogeneous resource distributions used in the experiments. Four types of LoRA configurations (Type 1 to Type 4) with different numbers of parameters are considered. The bars show the proportion of each LoRA configuration type in four different resource distribution scenarios: Uniform, Heavy-tail-light, Heavy-tail-strong, and Normal. The uniform distribution has equal proportions of all four types. The heavy-tail distributions have a larger proportion of either Type 1 or Type 4, reflecting the scenario where many clients have limited or abundant resources respectively. The Normal distribution has a dominant proportion of Type 2 and Type 3, indicating a more balanced distribution of client resources.

read the caption

Figure 3: Heterogeneous resource distributions containing different ratios of various LoRA configuration types.

🔼 This figure displays the test loss curves for FlexLoRA and FedIT across multiple communication rounds, under varying LoRA ranks (1, 8, and 200). It highlights FlexLoRA’s adaptability, especially in scenarios with highly heterogeneous resource distribution (heavy-tail), where it gradually converges to the performance of FedIT at the largest rank.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test loss of FlexLoRA and FedIT [43] across communication rounds under LORA ranks of 1, 8, and 200. FlexLORA demonstrates adaptability in an “extreme heavy tail” scenario and increasingly aligns with the performance of FedIT at the highest LORA rank as rounds progress. Implementation details are in Appendix A.

🔼 This figure shows the test loss curves for FlexLoRA and FedIT under different LORA ranks (1, 8, and 200) across multiple communication rounds. The ’extreme heavy tail’ scenario highlights FlexLoRA’s adaptability when dealing with significantly varying client resources (some with very low rank and some with high rank). FlexLoRA’s performance improves over time and converges towards the performance of FedIT at a higher LORA rank, illustrating the algorithm’s ability to leverage diverse client resources effectively.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test loss of FlexLoRA and FedIT [43] across communication rounds under LORA ranks of 1, 8, and 200. FlexLORA demonstrates adaptability in an “extreme heavy tail” scenario and increasingly aligns with the performance of FedIT at the highest LORA rank as rounds progress. Implementation details are in Appendix A.

🔼 This figure compares the test loss of FlexLoRA and FedIT over communication rounds for different LORA ranks (1, 8, and 200). It shows that FlexLoRA adapts well even in scenarios with highly unequal client resource distributions (the ’extreme heavy tail’ scenario), performing comparably to FedIT with higher LORA ranks as training progresses.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test loss of FlexLoRA and FedIT [43] across communication rounds under LORA ranks of 1, 8, and 200. FlexLORA demonstrates adaptability in an “extreme heavy tail” scenario and increasingly aligns with the performance of FedIT at the highest LORA rank as rounds progress. Implementation details are in Appendix A.

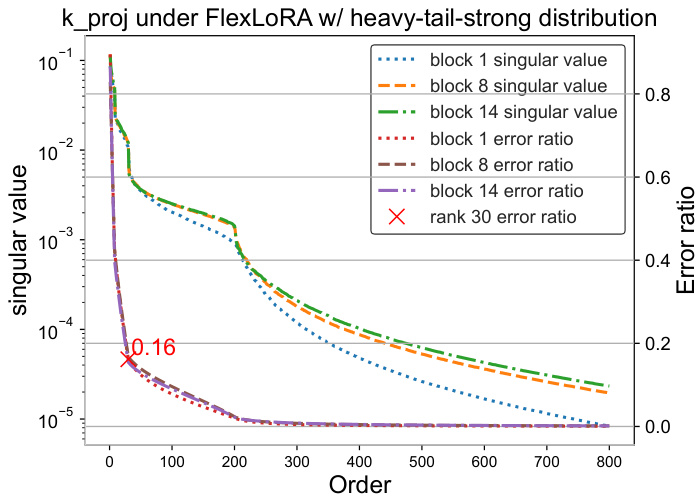

🔼 This figure shows the impact of FlexLoRA on model performance using different LoRA ranks. In 6(a), the test loss curves for FedIT with and without FlexLoRA are compared at LoRA ranks 8 and 200. The results show similar performance at rank 8 but differing performance at rank 200, highlighting the impact of FlexLoRA. In 6(b), singular value distributions and approximation errors are depicted for qproj weights, demonstrating the impact of using SVD in FlexLoRA for weight decomposition.

read the caption

Figure 6: The sub-figure 6(a) shows that FedIT with LoRA rank 8 has comparable test loss curves for standard and FlexLoRA integration. At rank 200, though, standard FedIT differs from other versions. 6(b) depicts singular value distributions and approximation errors, where the red cross indicates the average error for rank 30 qproj weights in specific blocks. Further details are in Appendix H.

🔼 The figure shows the test loss curves for FlexLoRA and FedIT under different LoRA ranks (1, 8, and 200) across multiple communication rounds. It highlights FlexLoRA’s adaptability, particularly in scenarios with highly heterogeneous resource distributions (the ’extreme heavy tail’ scenario). As the number of communication rounds increases, FlexLoRA’s performance increasingly aligns with that of FedIT at the highest LORA rank. This demonstrates FlexLoRA’s ability to effectively leverage heterogeneous client resources.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test loss of FlexLoRA and FedIT [43] across communication rounds under LORA ranks of 1, 8, and 200. FlexLORA demonstrates adaptability in an “extreme heavy tail

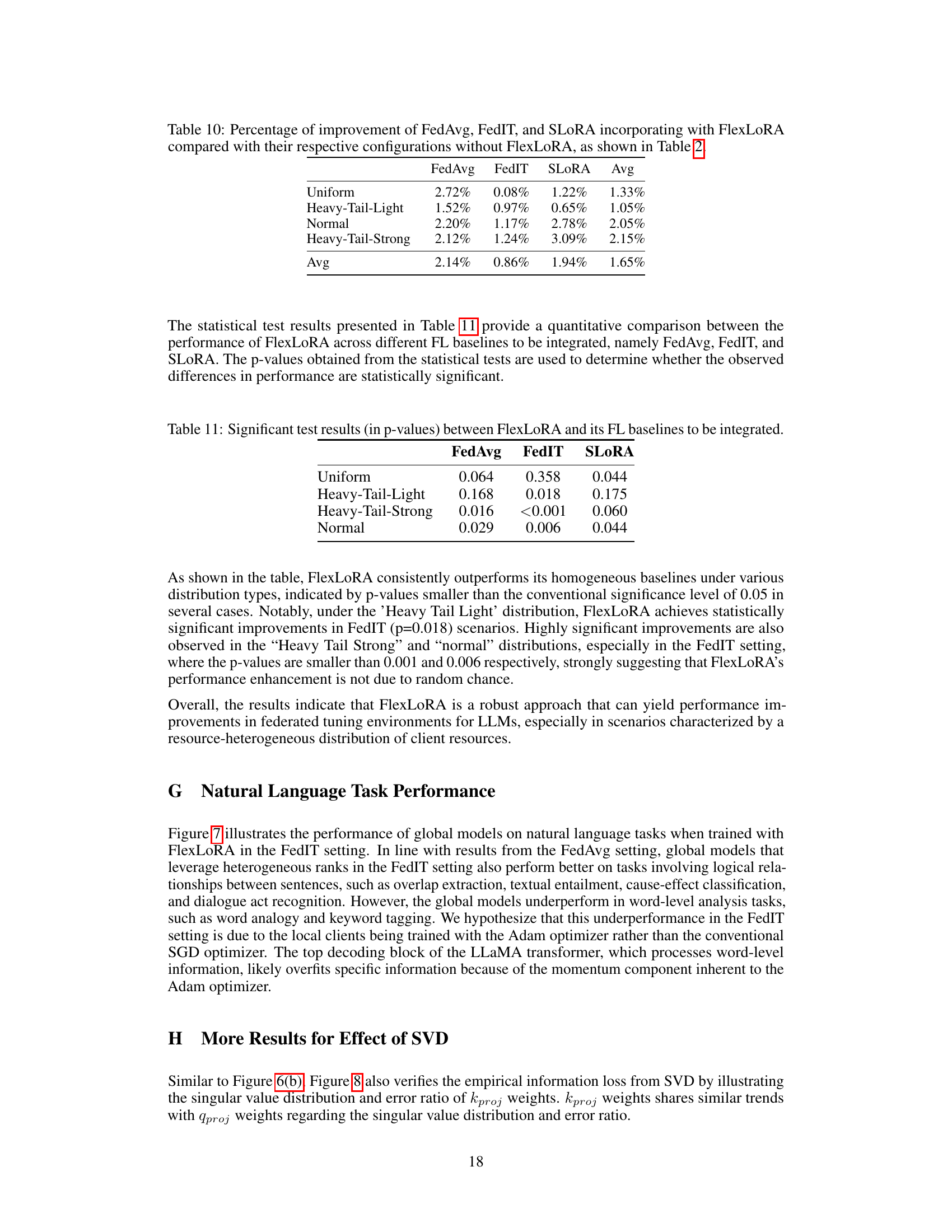

🔼 This figure shows the singular value distribution and approximation error for kproj weights in FlexLoRA with a heavy-tail-strong resource distribution. It demonstrates that using the top 30 singular values provides a good approximation (error ratio of approximately 0.16).

read the caption

Figure 8: Distribution of singular values and the approximation error ratio between the top i-th singular value approximated kproj weights and the actual full-rank kproj weights. The red cross denotes the average error for weights with rank 30 of kproj across blocks 1, 8, and 14.

🔼 This figure shows the test loss curves for FlexLoRA and FedIT with different LoRA ranks (1, 8, and 200) across multiple communication rounds. FlexLoRA adapts well to scenarios with heterogeneous resource distribution (heavy tail scenario), while FedIT’s performance is constrained by the lowest LoRA rank among clients. As the number of communication rounds increases, FlexLoRA’s performance improves and converges towards that of FedIT at the highest LORA rank.

read the caption

Figure 1: Test loss of FlexLoRA and FedIT [43] across communication rounds under LORA ranks of 1, 8, and 200. FlexLORA demonstrates adaptability in an “extreme heavy tail

More on tables

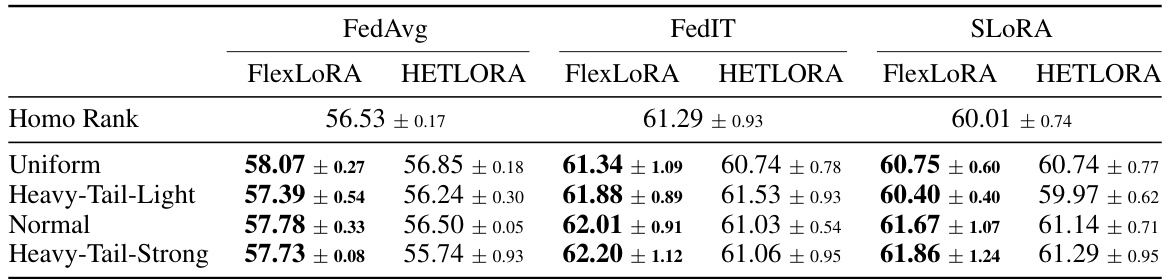

🔼 This table compares the performance of different federated learning methods on unseen clients, assessing their ability to generalize to new data distributions. It shows the average Rouge-L scores for several baselines (FedAvg, FedIT, SLORA) with homogeneous LoRA ranks, and the same baselines enhanced with FlexLoRA and HETLORA, across different resource distribution scenarios (Uniform, Heavy-Tail-Light, Normal, Heavy-Tail-Strong). The results highlight the improved generalization performance of FlexLoRA across various scenarios.

read the caption

Table 2: The weighted average Rouge-L scores of unseen clients provide insights into the global model's generalization ability. Results from baseline methods with homogeneous ranks (Line 3, denoted as Homo Rank) are compared with those incorporating FlexLoRA and HETLORA across various resource distributions (Line 4~7). The significant test are presented in Appendix F.

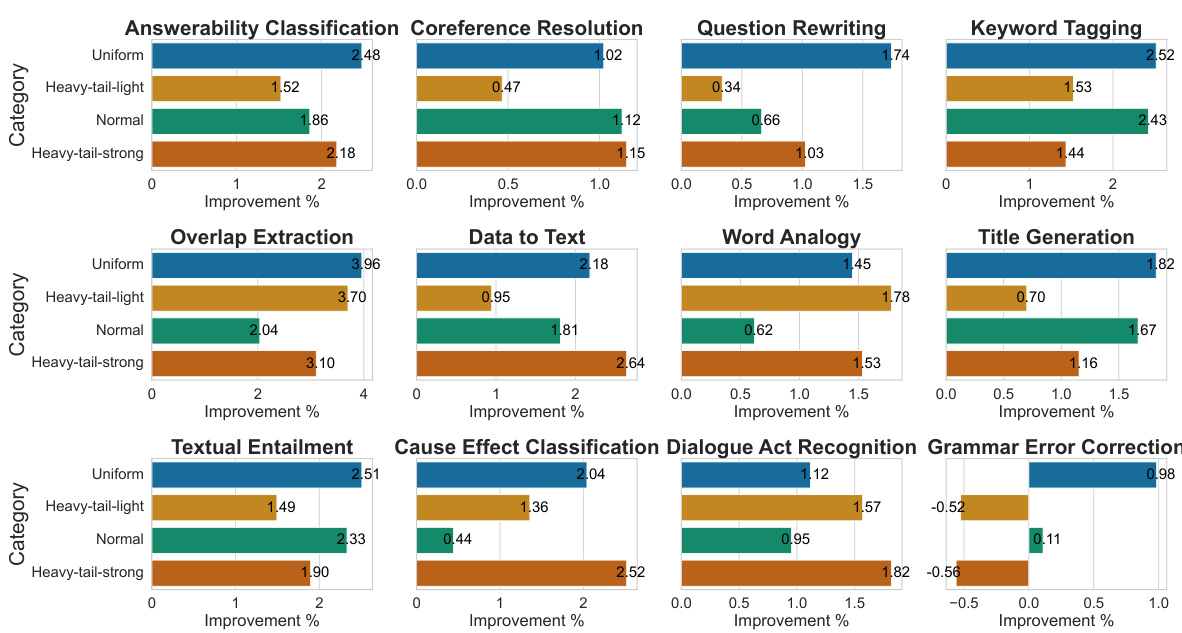

🔼 This table presents the average percentage improvement achieved by integrating FlexLoRA across different resource distributions for three baseline methods: FedAvg, FedIT, and SLORA. The improvements are calculated across 12 NLP task categories. A more detailed comparison is shown in Figure 4.

read the caption

Table 3: Average percentage improvement of FlexLoRA over baseline methods (FedAvg, FedIT, SLORA) across different resource distributions, calculated over 12 NLP task categories. More detailed comparison is presented in Figure 4.

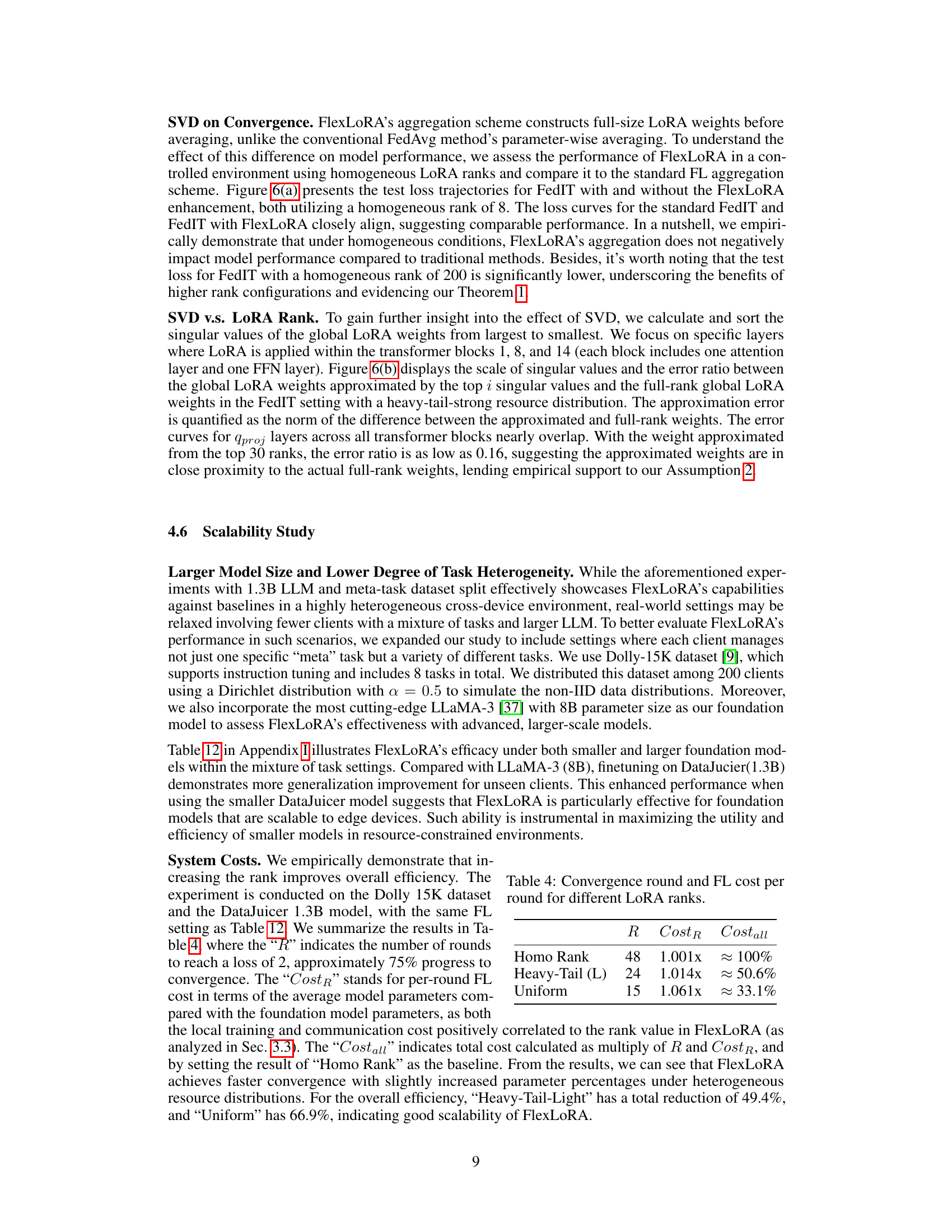

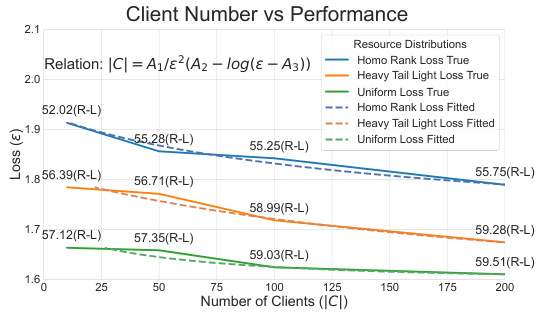

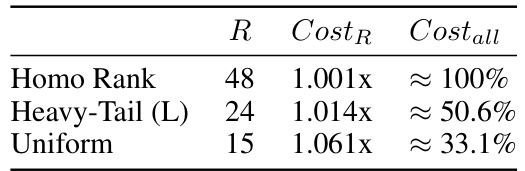

🔼 This table shows the number of communication rounds (‘R’) needed to reach a loss of 2 (approximately 75% progress to convergence) and the per-round FL cost (‘CostR’) relative to the homogeneous rank baseline (1.001x ≈ 100%). The total cost (‘Costall’) is also shown, representing the product of ‘R’ and ‘CostR’. The results illustrate FlexLoRA’s efficiency gains under different resource distributions (Homo Rank, Heavy-Tail (L), Uniform).

read the caption

Table 4: Convergence round and FL cost per round for different LoRA ranks.

🔼 This table compares four different LoRA configurations (Type 1-4) with full finetuning in terms of the percentage of trainable parameters, memory cost, and the speedup achieved. Type 1 uses a rank of 8 across all layers, Type 2 uses a rank of 30, Type 3 uses a rank of 30 for attention layers and 200 for feed-forward network (FFN) layers, and Type 4 uses a rank of 200 across all layers. The table shows that using LoRA significantly reduces the number of trainable parameters and memory consumption compared to full finetuning, with the speedup increasing as the rank increases.

read the caption

Table 5: Trainable parameters and memory cost for different LoRA configurations, and the corresponding efficiency improvement compared with full finetuning.

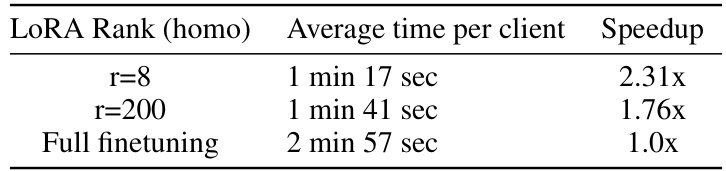

🔼 This table shows the average time per client to complete one communication round for different LoRA ranks (8 and 200) and for full finetuning. It demonstrates the speedup achieved by using LoRA compared to full finetuning. A lower time and higher speedup indicate a more efficient training process.

read the caption

Table 6: Speedup of LoRA tuning for each communication round.

🔼 This table provides example inputs, outputs, and explanations for a ‘Cause Effect Classification’ task from the Natural Instructions dataset. It shows how the task is defined, including positive and negative examples to illustrate the expected input-output relationships. The table also includes a sample instance and the valid output format.

read the caption

Table 7: Illustration of the original data structure for tasks in natural instruction dataset [39].

🔼 This table shows an example of how the data is structured in the natural instruction dataset used in the paper. It illustrates the format of the input, output, and category for a specific task, namely ‘Cause Effect Classification.’ The example shows how two sentences are provided as input, and the task is to determine whether the second sentence is the cause or effect of the first. The output shows the correct label (‘cause’) for this specific example, along with the task category.

read the caption

Table 7: Illustration of the original data structure for tasks in natural instruction dataset [39].

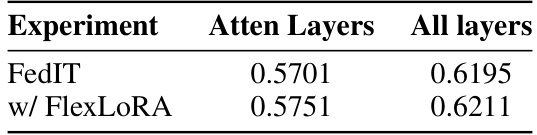

🔼 This table shows the impact of adding LoRA to different layers (attention layers only vs. all layers) on the zero-shot Rouge-L score of the global model in a federated learning setting. The results are compared for the standard FedIT method and the same method augmented with FlexLoRA (a proposed aggregation method). A uniform client resource distribution was used for the FlexLoRA experiment.

read the caption

Table 9: Impact of choosing different layers to apply LoRA module. The results are zero-shot Rouge-L score of the global model. For the experiment that uses FlexLoRA for aggregation, the client resource distribution is uniform.

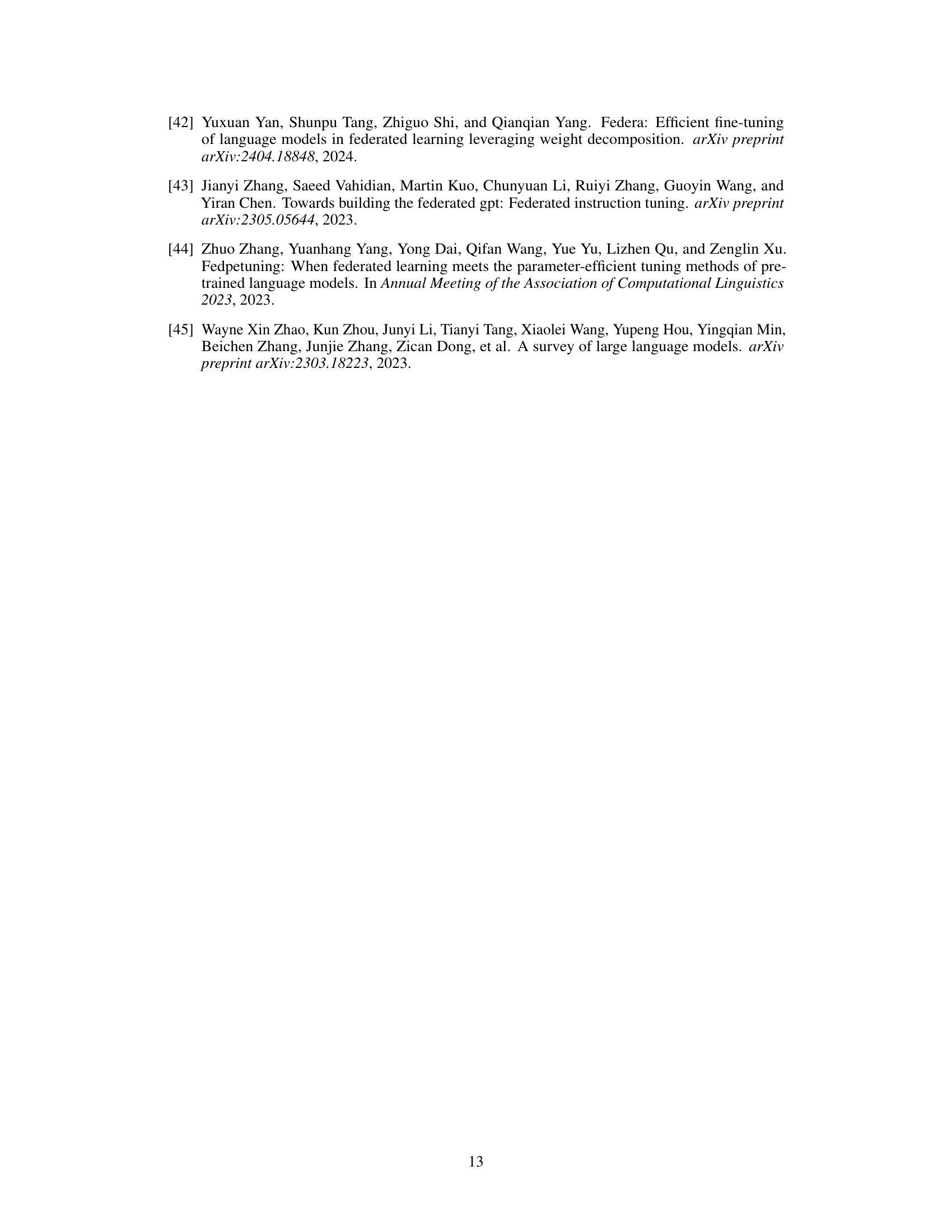

🔼 This table shows the percentage improvement achieved by integrating FlexLoRA into three different federated learning baselines (FedAvg, FedIT, SLORA) across four different resource distributions (Uniform, Heavy-Tail-Light, Normal, Heavy-Tail-Strong). The average improvement across all baselines and distributions is also provided. It offers a concise summary of the performance gains obtained by incorporating FlexLoRA to highlight its effectiveness in enhancing the generalization ability of federated global models.

read the caption

Table 10: Percentage of improvement of FedAvg, FedIT, and SLORA incorporating with FlexLoRA compared with their respective configurations without FlexLoRA, as shown in Table 2.

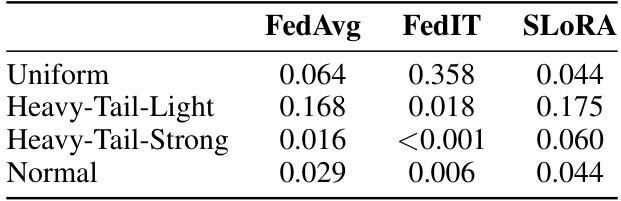

🔼 This table presents the p-values from statistical significance tests comparing the performance of FlexLoRA against three federated learning baselines (FedAvg, FedIT, and SLORA) across four different resource distributions. Low p-values (typically below 0.05) indicate statistically significant differences, suggesting that FlexLoRA’s performance improvements are not due to random chance. The results show FlexLoRA’s consistent outperformance across various scenarios.

read the caption

Table 11: Significant test results (in p-values) between FlexLoRA and its FL baselines to be integrated.

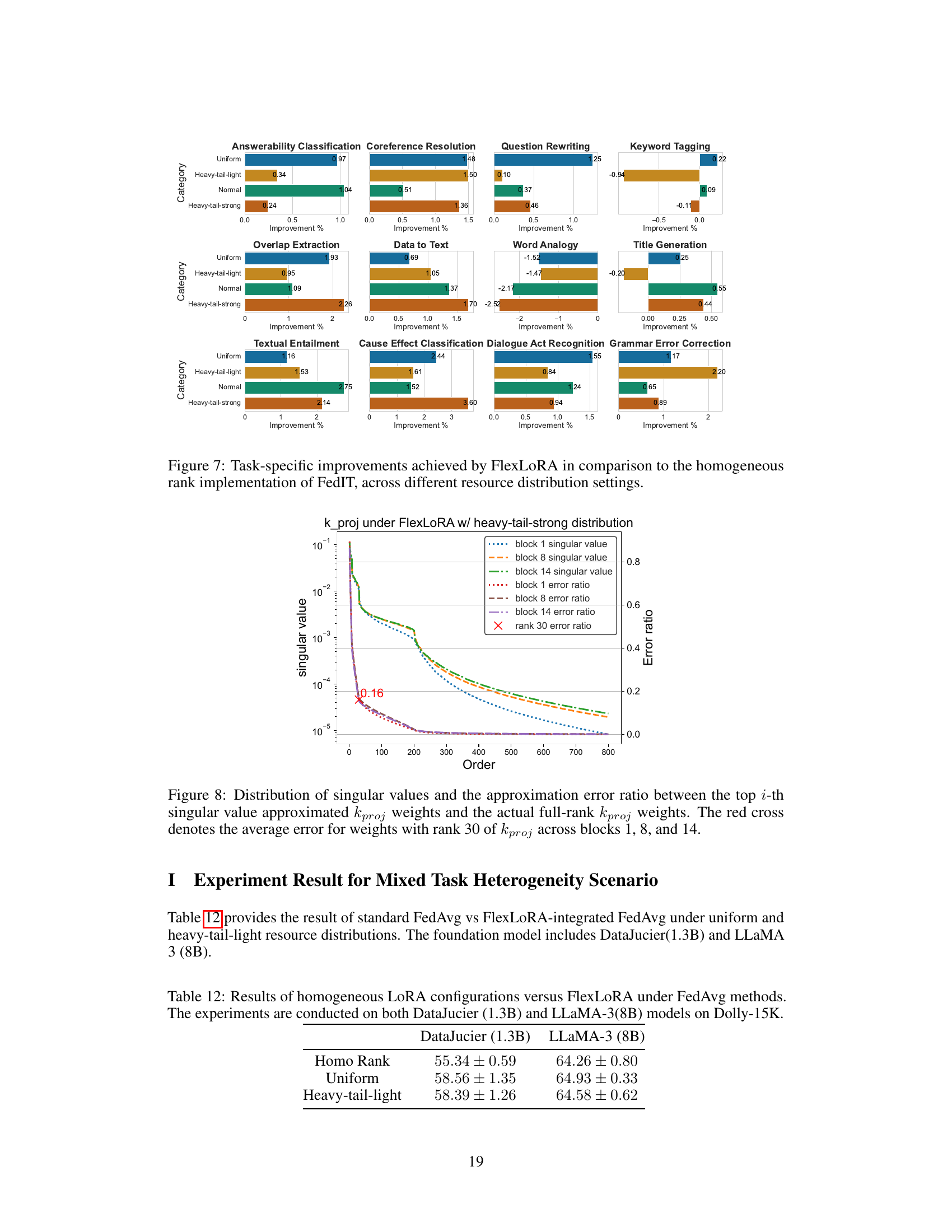

🔼 This table presents the results of comparing the performance of standard FedAvg with FlexLoRA integrated FedAvg under different resource distributions (uniform and heavy-tail-light) and using two different base models (DataJucier 1.3B and LLaMA-3 8B). It shows the average Rouge-L scores achieved by each method, highlighting the impact of FlexLoRA on model generalization across diverse resource conditions.

read the caption

Table 12: Results of homogeneous LoRA configurations versus FlexLoRA under FedAvg methods. The experiments are conducted on both DataJucier (1.3B) and LLaMA-3(8B) models on Dolly-15K.

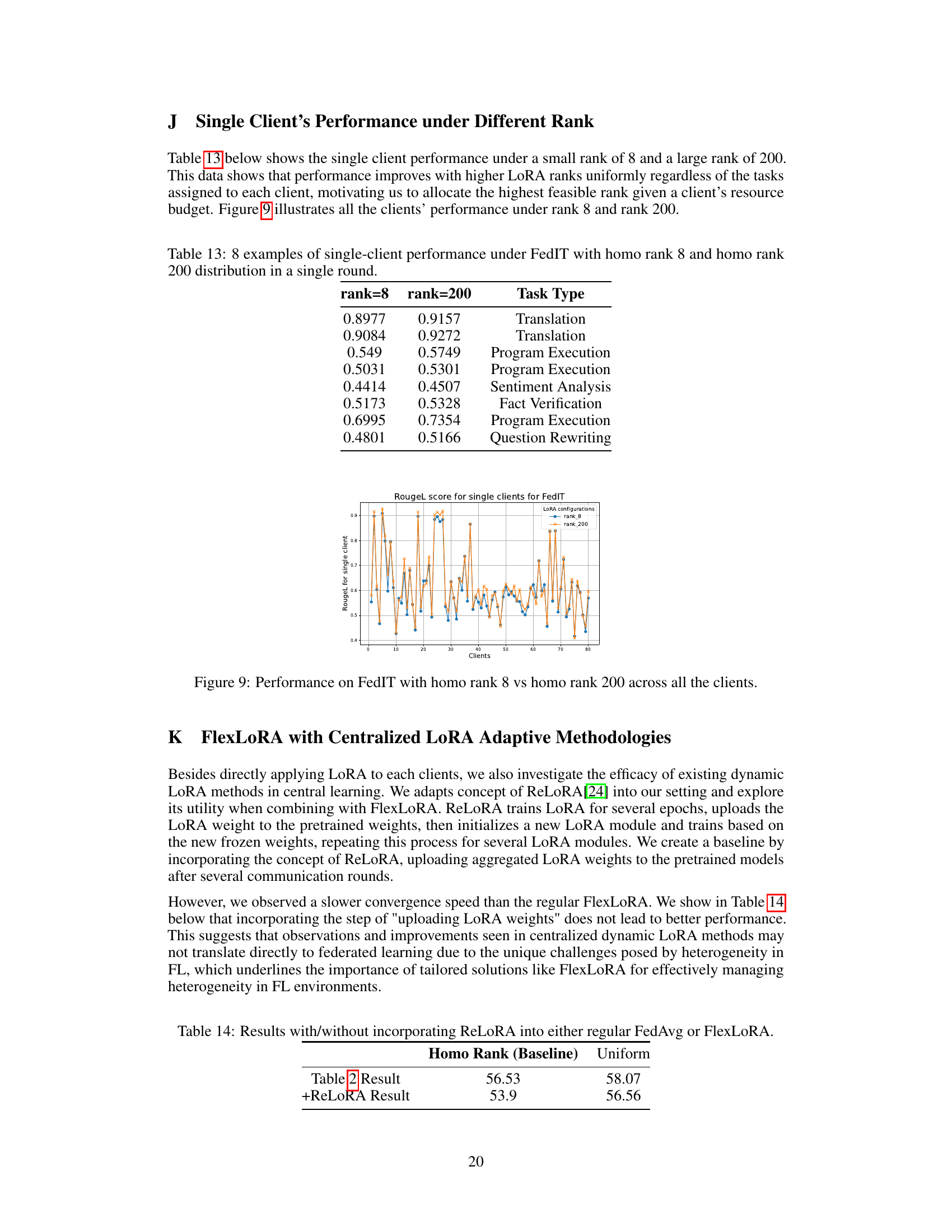

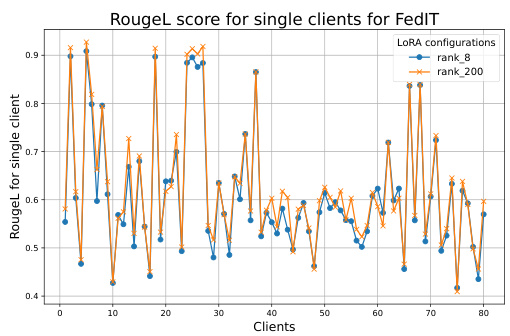

🔼 This table presents eight examples illustrating the performance of individual clients under the Federated IT (FedIT) framework using homogeneous LoRA ranks of 8 and 200. Each row shows a different client’s performance on a specific NLP task, showcasing the impact of the LoRA rank on individual client performance in a single round of the FedIT process. The results highlight the potential for improvement when higher ranks are utilized.

read the caption

Table 13: 8 examples of single-client performance under FedIT with homo rank 8 and homo rank 200 distribution in a single round.

🔼 This table presents the weighted average Rouge-L scores achieved on unseen clients using different federated learning (FL) methods. It compares the performance of methods with homogeneous LoRA ranks (a baseline) to methods incorporating the proposed FlexLoRA and HETLORA approaches. The comparison is made across various resource distributions (uniform, heavy-tail light, normal, heavy-tail strong). The results highlight the global model’s generalization ability as measured by its performance on unseen clients.

read the caption

Table 2: The weighted average Rouge-L scores of unseen clients provide insights into the global model's generalization ability. Results from baseline methods with homogeneous ranks (Line 3, denoted as Homo Rank) are compared with those incorporating FlexLoRA and HETLORA across various resource distributions (Line 4~7). The significant test are presented in Appendix F.

Full paper#