↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Current methods for providing feedback on human motion often lack personalization and scalability, limiting their effectiveness in sports coaching and motor skill learning. Traditional approaches require large amounts of annotated data and struggle to generalize across various actions. The lack of intelligent coaching systems that provide real-time corrective feedback highlights a significant need for improved technologies in areas such as rehabilitation and skill training.

CigTime addresses these limitations by using a novel approach combining motion editing and large language models. It generates corrective instructions by comparing source and target motion sequences, creating a dataset of motion triplets. A large language model is then fine-tuned on this data to generate corrective texts. The approach significantly outperforms baselines in generating high-quality instructions, improving user performance across diverse applications. This innovative framework shows promising results and opens the door for personalized and adaptive feedback in various scenarios.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it introduces a novel approach to generating corrective instructions for human motion, a crucial aspect of motor skill learning and sports coaching. It bridges the gap between motion editing and language models, creating a framework for generating personalized, effective feedback that could revolutionize how we teach and learn physical skills. Its innovative data collection method reduces reliance on manual annotations, making it scalable and potentially applicable to various applications. This approach opens new avenues for research in human-computer interaction and AI-powered coaching systems.

Visual Insights#

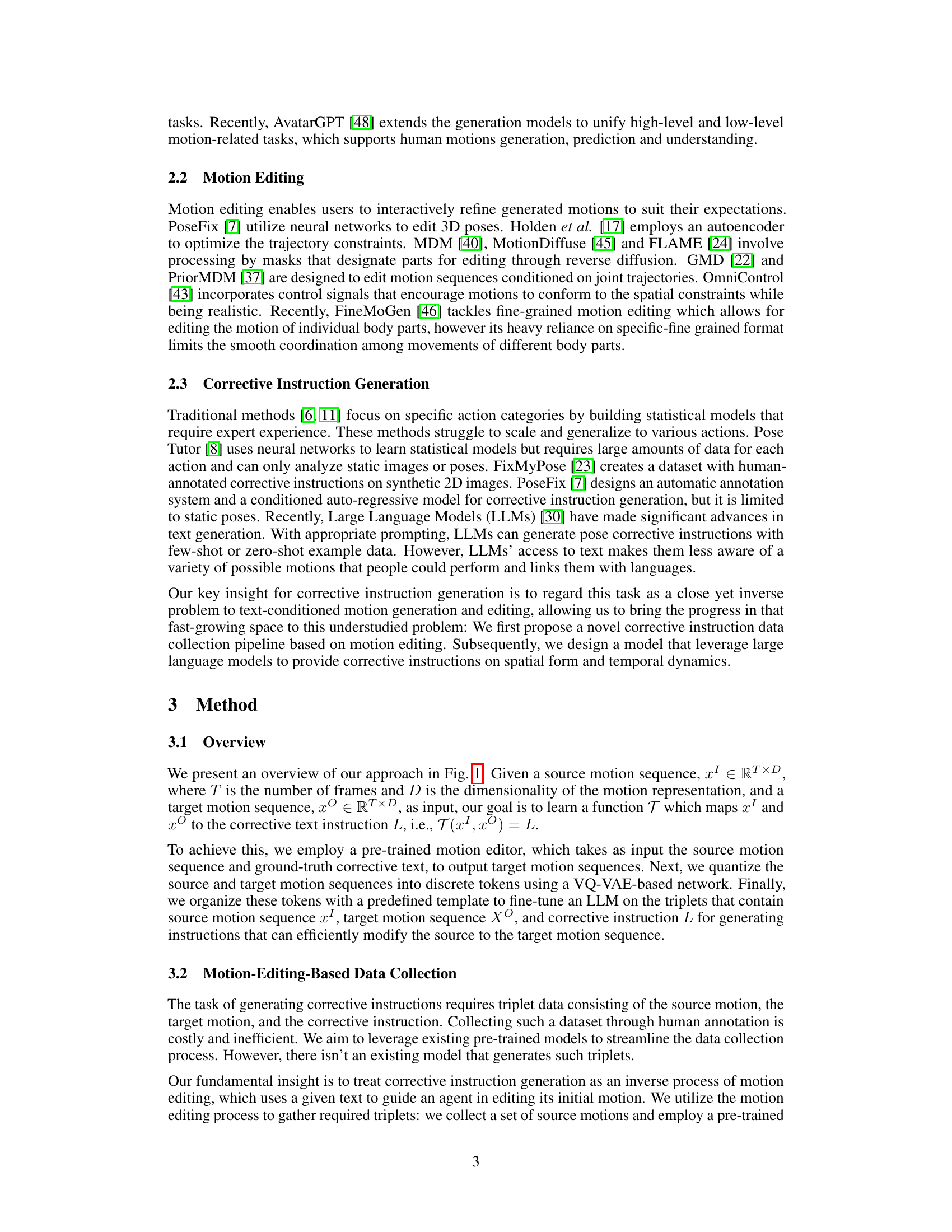

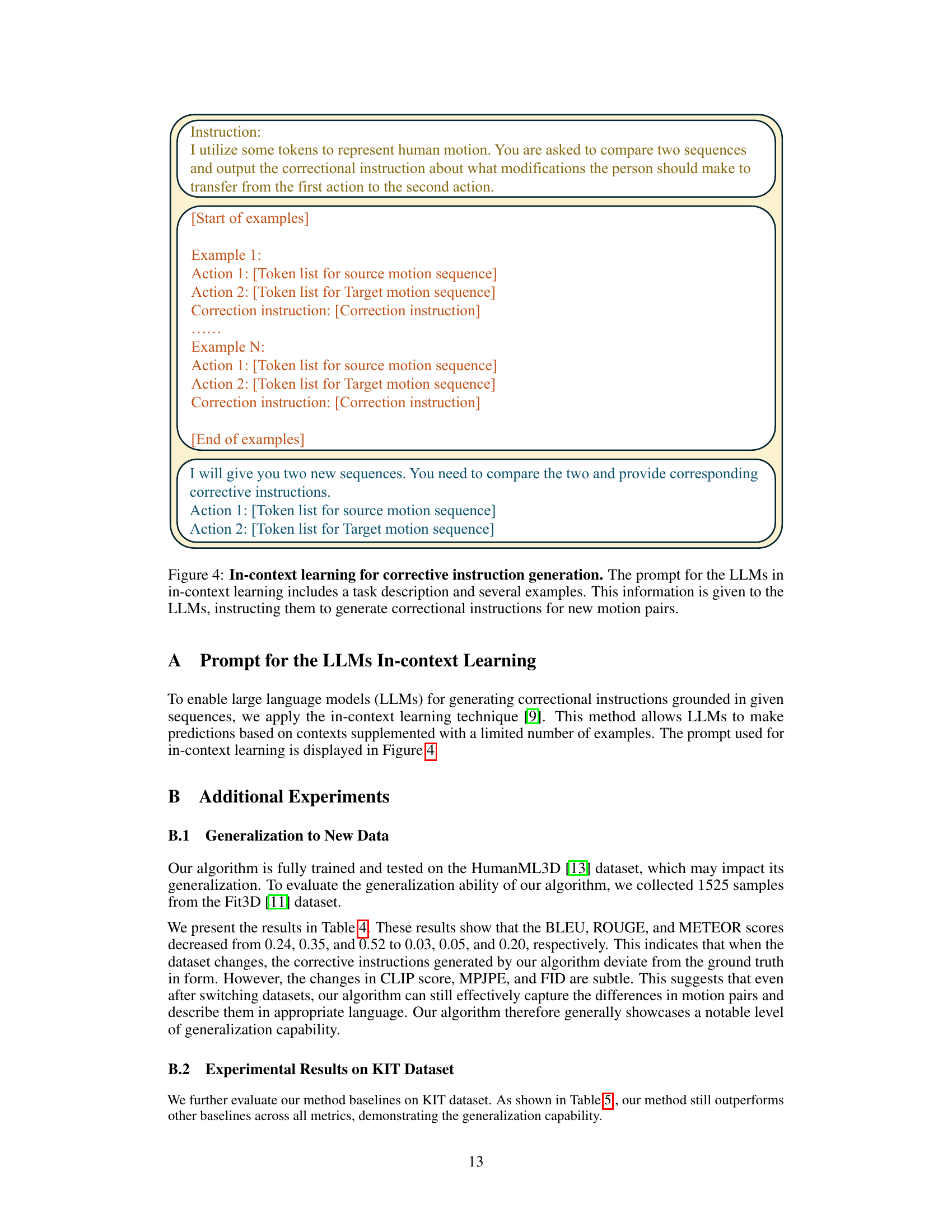

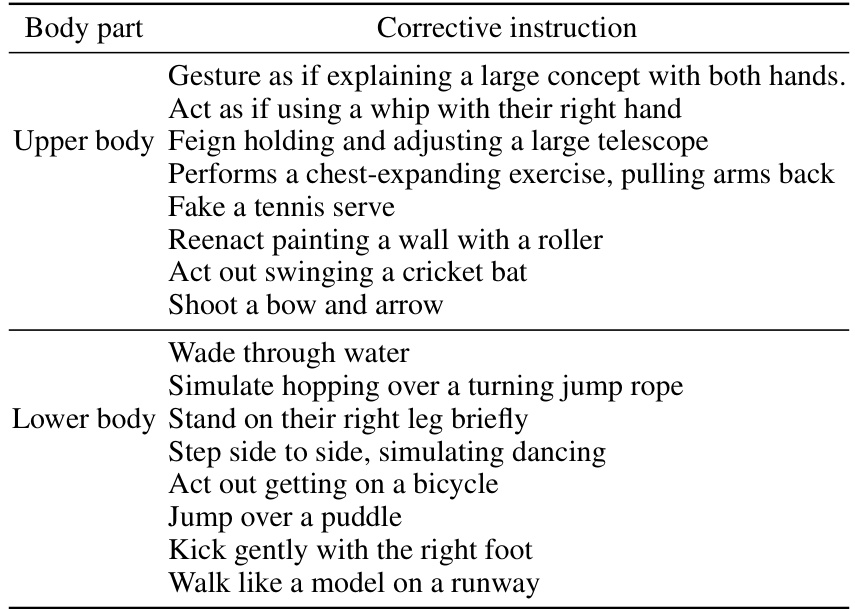

This figure illustrates the overall architecture of the CigTime model. It shows how source motion and corrective instructions are used as input to a motion editor, which produces a target motion. The source and target motions are then tokenized and fed into a large language model (LLM) to generate precise corrective instructions. An example is given showing corrective instruction generation for the action of lifting weights using the upper body.

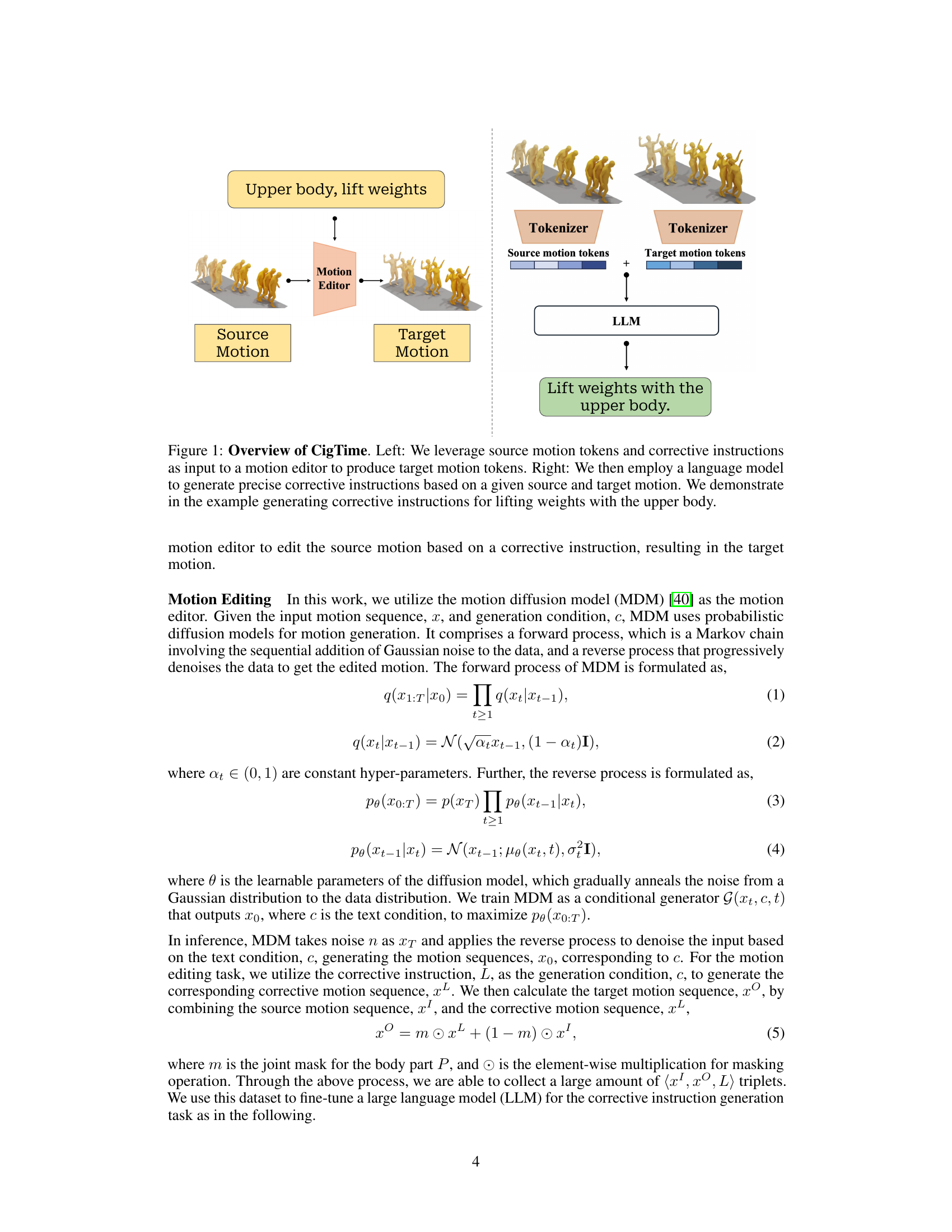

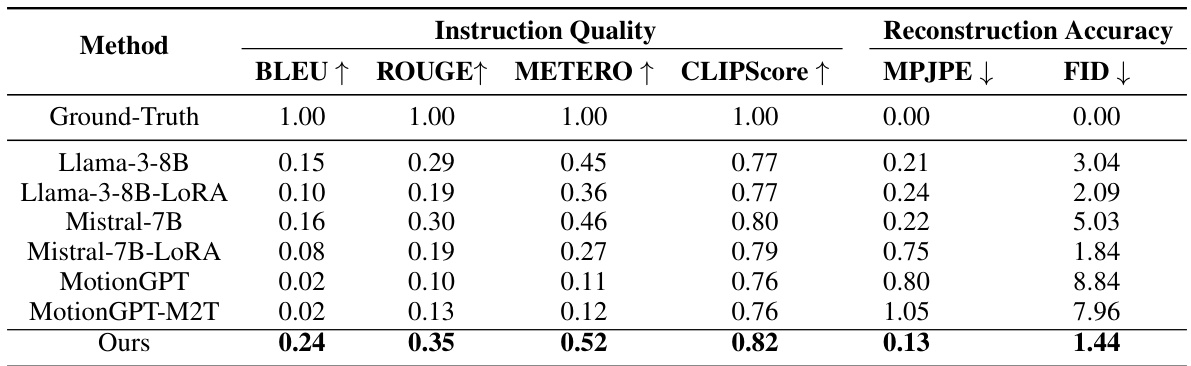

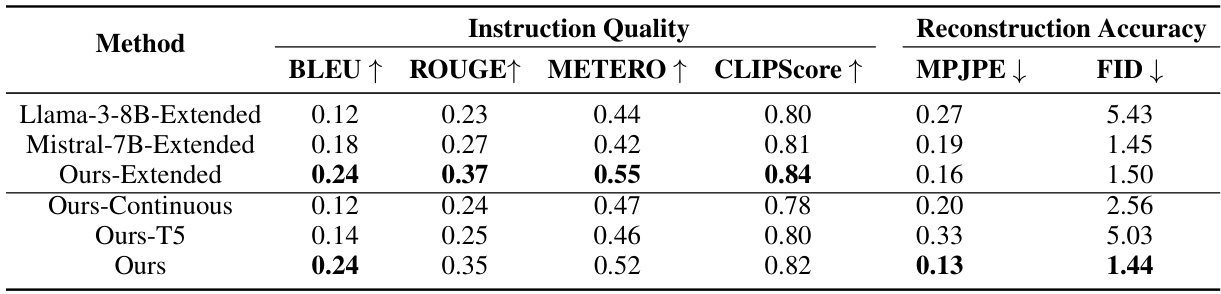

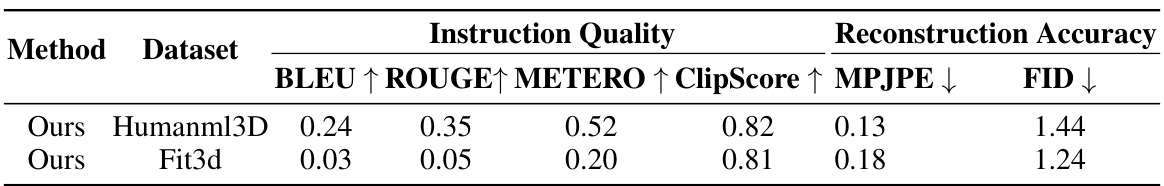

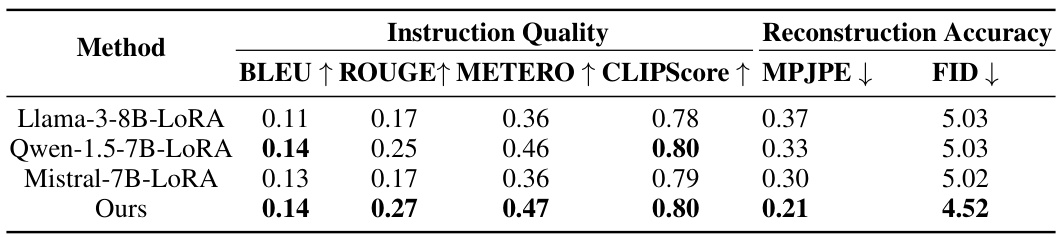

This table compares the performance of the proposed CigTime model against several baseline models on the task of corrective instruction generation for human motion. The evaluation metrics include both instruction quality (BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, CLIPScore) and reconstruction accuracy (MPJPE, FID). The results show that CigTime significantly outperforms all the baselines across all metrics, demonstrating its effectiveness in generating high-quality corrective instructions.

In-depth insights#

Inverse Motion Editing#

Inverse motion editing, as a concept, presents a fascinating challenge within the field of AI and motion capture. It flips the traditional approach of motion generation, where text or other inputs are used to create motion, to instead focus on modifying existing motion to meet a specific goal. This is essentially a corrective process, aiming to transform an initial movement into a desired one. The core difficulty lies in determining not just what changes are needed, but also how to translate those changes into clear, actionable instructions. This requires a deep understanding of the nuances of human movement, going beyond simple pose adjustments to encompass the complex interplay of timing, dynamics, and overall fluidity. Successfully achieving inverse motion editing would thus have significant impact on various fields, such as sports coaching, physical therapy, and even animation. The potential for personalized feedback and targeted instruction is particularly noteworthy, leading to more efficient and effective skill development.

LLM Fine-tuning#

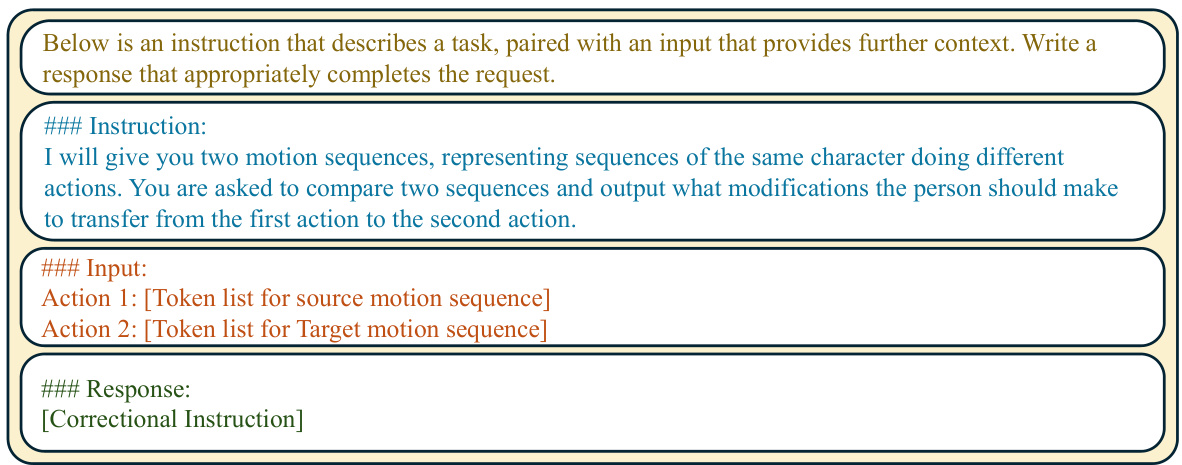

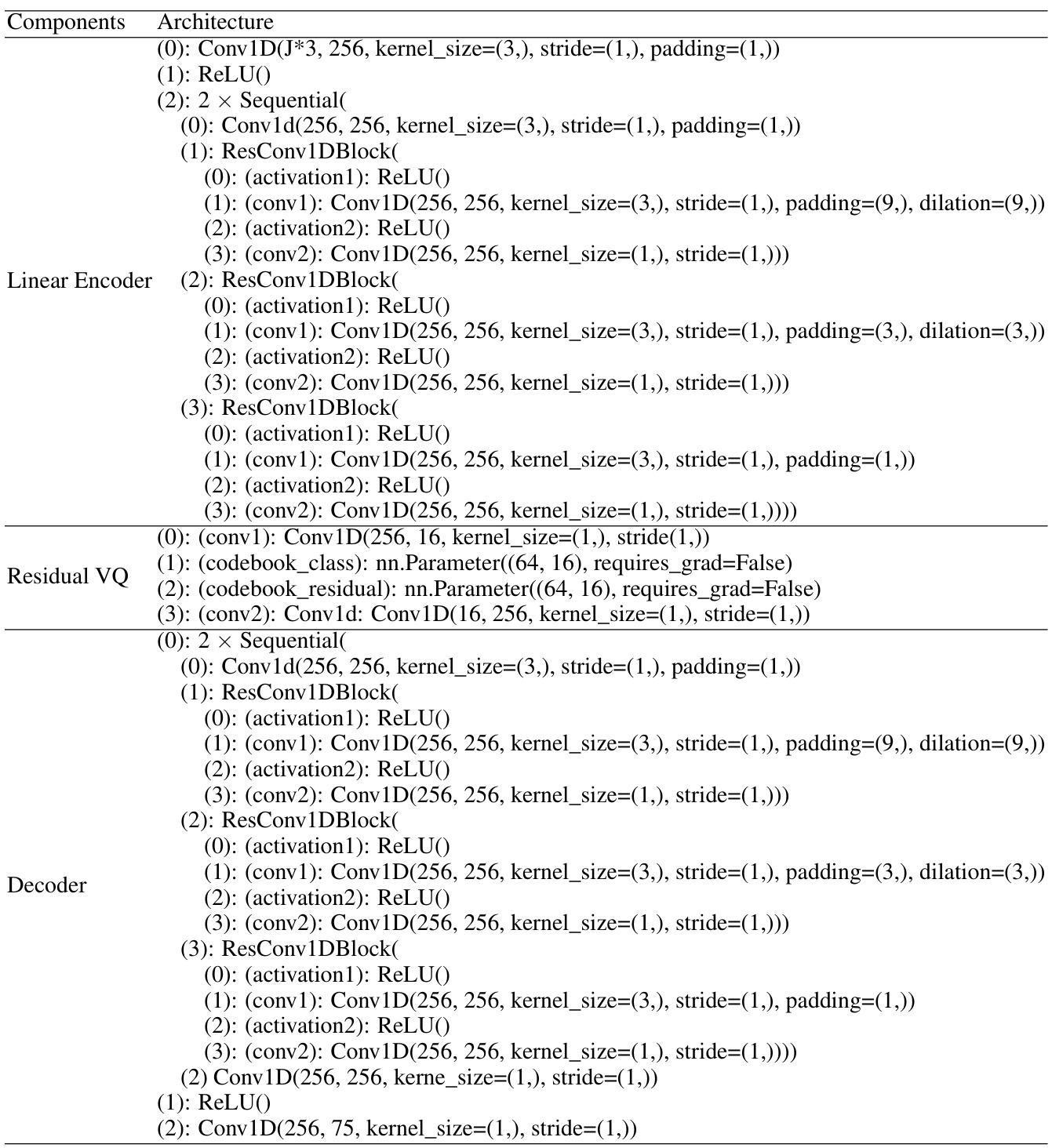

Fine-tuning large language models (LLMs) for corrective instruction generation in the context of motion correction is a crucial aspect of the proposed CigTime framework. The approach leverages a motion editing pipeline to create a dataset of motion triplets: source motion, target motion, and corrective instruction. This data-centric approach bypasses the need for extensive manual annotation, a significant improvement over traditional methods. The core of the fine-tuning process involves representing source and target motion sequences as discrete tokens via a VQ-VAE based network. This tokenization, in combination with a template defining the input structure for the LLM, helps establish a structured and efficient learning process. The LLM is then fine-tuned using a cross-entropy loss function, which directly optimizes the model to produce precise and actionable instructions. The use of pre-trained motion editors to generate the dataset allows the LLM to learn the complex relationship between motion discrepancies and corresponding corrective text. Furthermore, the use of discrete tokens makes the LLM more robust to the temporal dynamics inherent in human motion sequences. The choice to fine-tune an existing LLM, rather than training a model from scratch, also reflects an efficient strategy that leverages prior knowledge. In essence, the LLM fine-tuning process lies at the heart of CigTime’s ability to translate motion differences into helpful, user-focused instructions.

Motion-Editing Data#

The effectiveness of any motion-based model hinges on the quality of its training data. A section on ‘Motion-Editing Data’ would be crucial for detailing how this data was generated and what considerations were made. This would likely involve explaining the use of a pre-trained motion editor to modify source motions based on generated instructions, producing target motions. The methodology for creating motion triplets (source, target, and instruction) should be rigorously described. This might involve discussing the specific motion editing techniques and the rationale behind their selection. Further points of interest would be the scale of the dataset (size and diversity of motions and instructions are key), the process for ensuring data quality (noise reduction, outlier removal), and the procedures to avoid biases in the data. Addressing data annotation is vital, whether it was manually or automatically performed and the degree of human involvement. Finally, any limitations of the data collection pipeline (such as a bias towards specific types of motion or instructions) should be transparently acknowledged to ensure the robustness and generalizability of the subsequent model.

Generalization Limits#

The concept of “Generalization Limits” in the context of a research paper about corrective instruction generation through inverse motion editing is crucial. It would explore the boundaries of the model’s ability to adapt to unseen data. Key considerations would include the diversity of motions within the training dataset, impacting the model’s ability to generalize to new, unseen motion types; the impact of different motion capture technologies or data preprocessing techniques employed, leading to variations in the data representation which could affect generalization performance; and the robustness of the corrective instructions to noise or variations in the input motion data, determining if the generated instructions remain accurate and useful across different degrees of input noise or variations in motion capture quality. The paper could also address whether the language model’s ability to generate effective instructions generalizes across different languages or cultural contexts, and if there are potential limitations in handling high-level instructions that require complex reasoning and understanding of underlying motion patterns. Finally, it would examine the extent to which the model’s performance on specific action categories influences its overall generalization capacity, exploring whether biases in the training data or the inherent difficulty of certain motion types limit the model’s broad applicability.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore several promising avenues. Expanding the dataset to include a wider range of motion types, skill levels, and athletic disciplines is crucial for improving the model’s generalizability. Incorporating contextual information, such as the environment or the user’s goals, would enhance the quality and relevance of the corrective instructions. Addressing the temporal dynamics of motion more effectively is also needed. Current methods handle individual frames, limiting the capacity to interpret motion sequences holistically. Furthermore, integrating real-time feedback mechanisms could transform this technology into a powerful adaptive coaching tool. This would involve combining the instruction generation system with motion capture and provide immediate responses to the user’s movements. Finally, investigating ethical considerations is paramount. Addressing issues around potential misuse, bias, and data privacy is crucial for responsible development and deployment of such technology, ensuring it promotes well-being and inclusivity.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure shows a schematic overview of the CigTime framework. The left side illustrates how source motion tokens (representing the user’s current movement) and corrective instructions are fed into a motion editor. This editor then produces target motion tokens, which reflect the desired movement. The right side shows how a language model uses the source and target motion tokens to generate precise text-based instructions guiding the user toward the desired motion. An example is provided showing corrective instructions for the action of lifting weights.

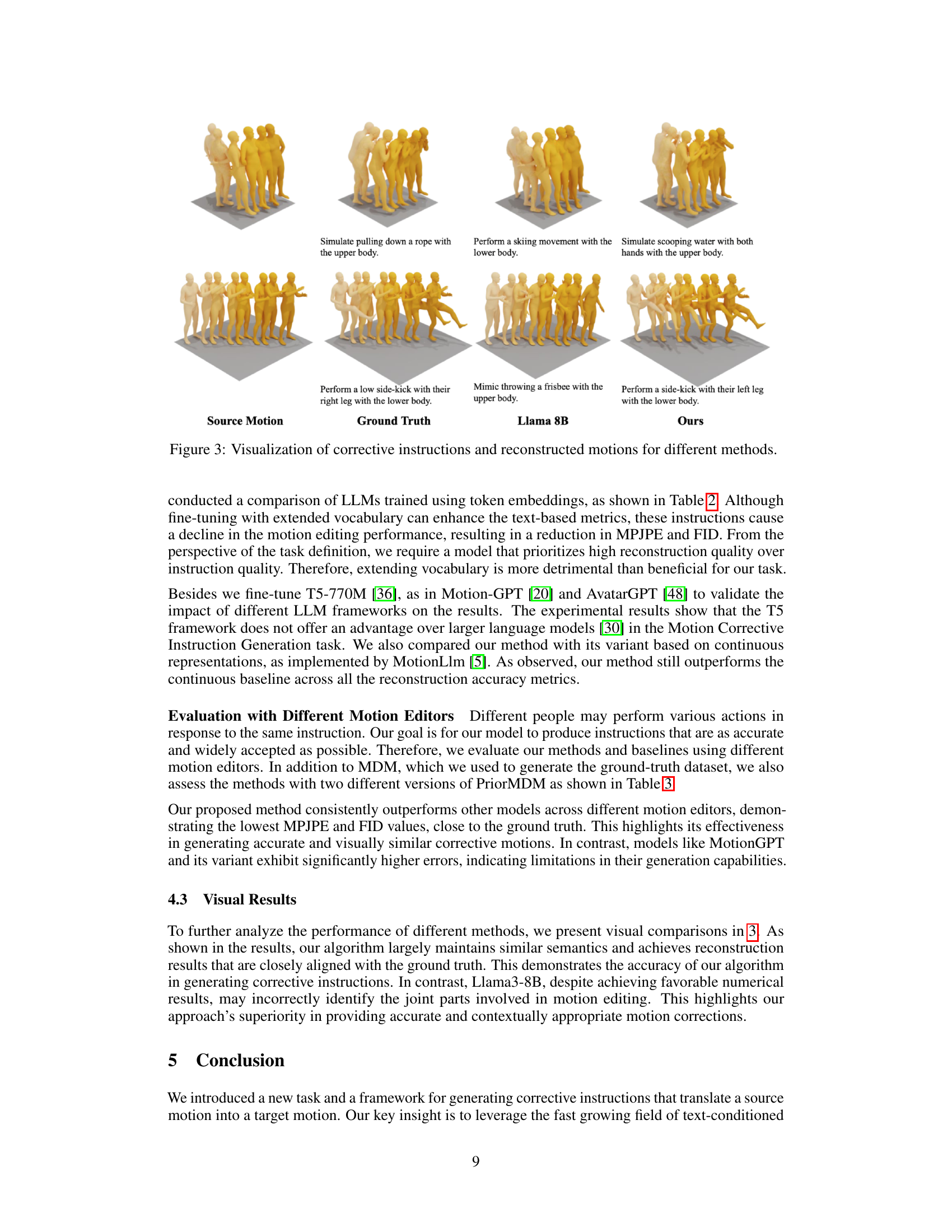

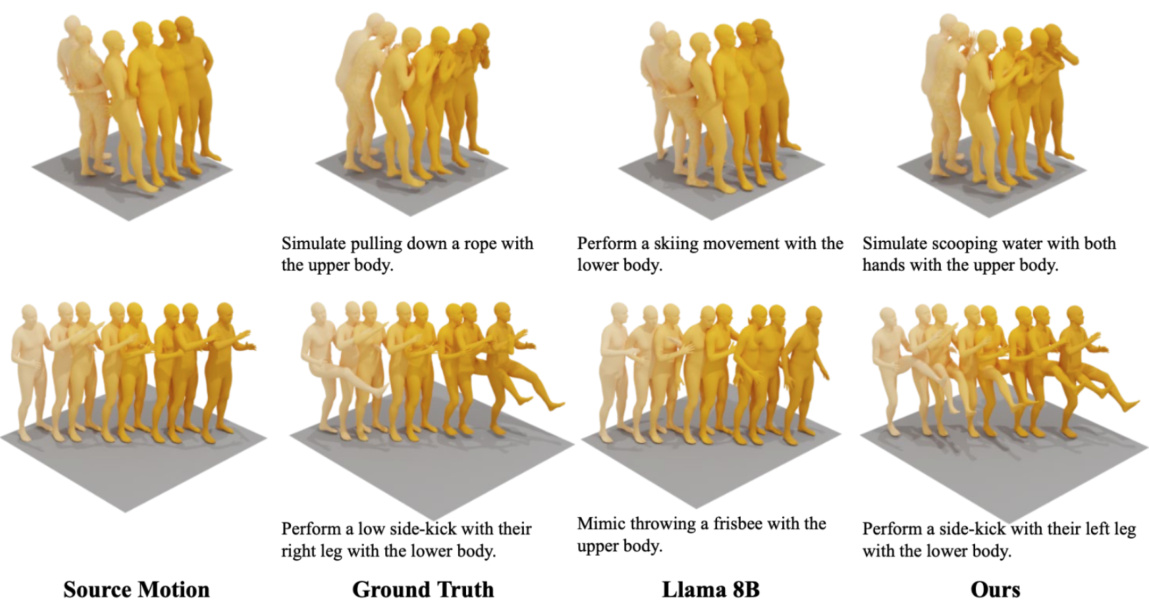

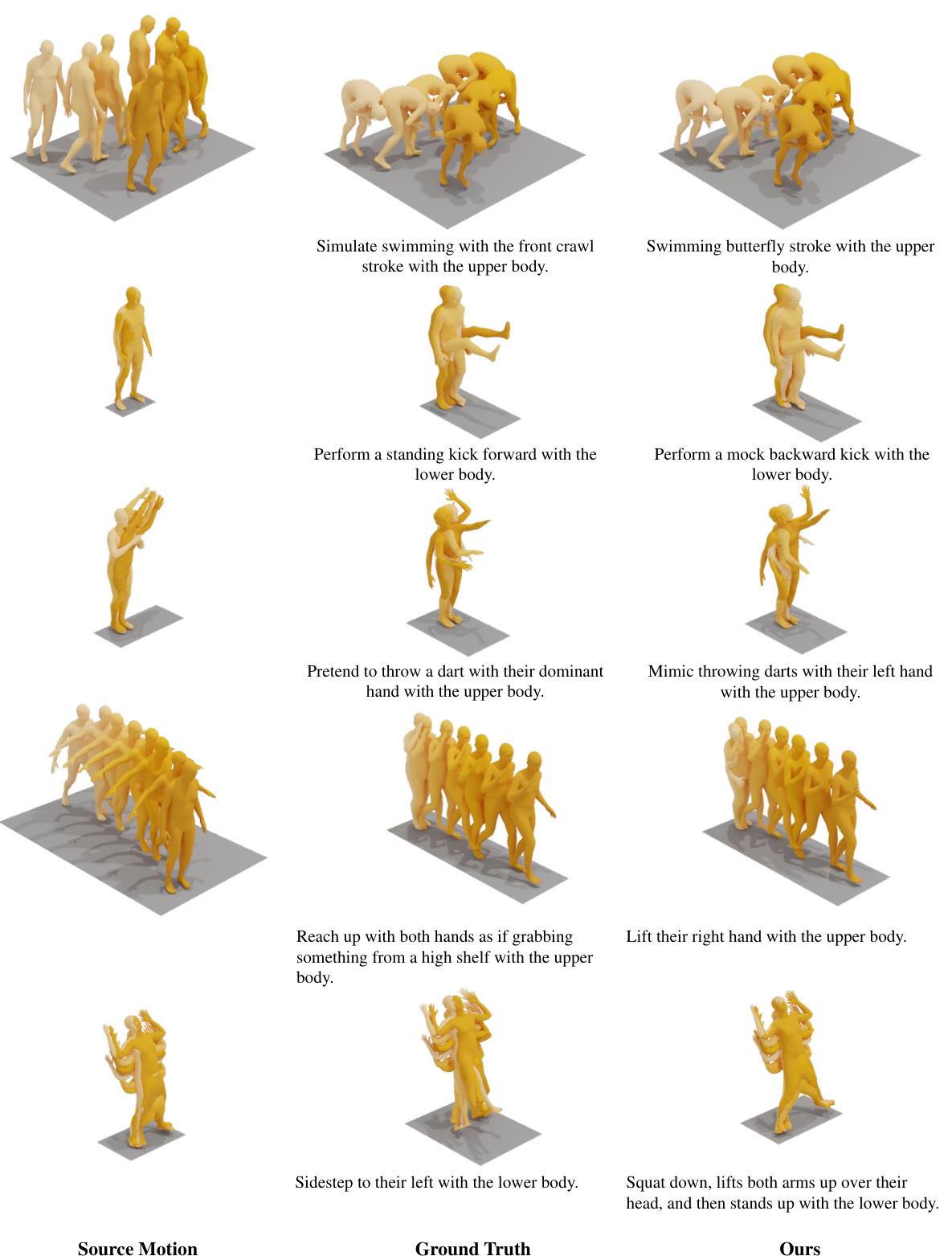

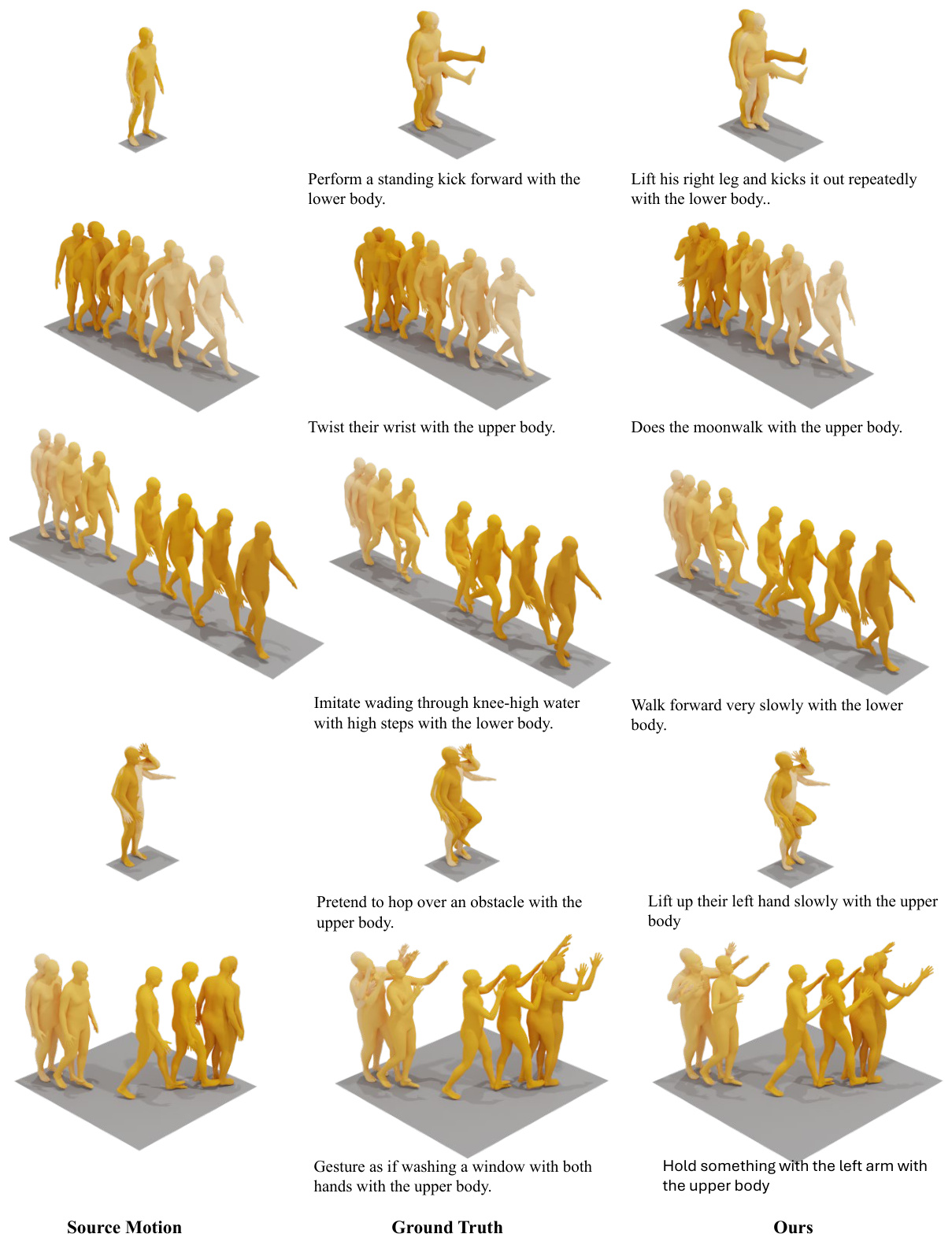

This figure visualizes the corrective instructions and reconstructed motions generated by different methods, including the ground truth, Llama 8B, and the proposed CigTime model. It shows three example motion pairs (source and target motions) for different actions involving the upper and lower body. The visualizations demonstrate the quality and accuracy of the generated corrective instructions and the resulting reconstructed motions compared to the ground truth.

This figure illustrates the CigTime framework. The left side shows how source motion tokens and corrective instructions are fed into a motion editor to generate target motion tokens. The right side shows how a language model generates precise corrective instructions from the source and target motion tokens. An example is provided demonstrating how to generate instructions for lifting weights using the upper body.

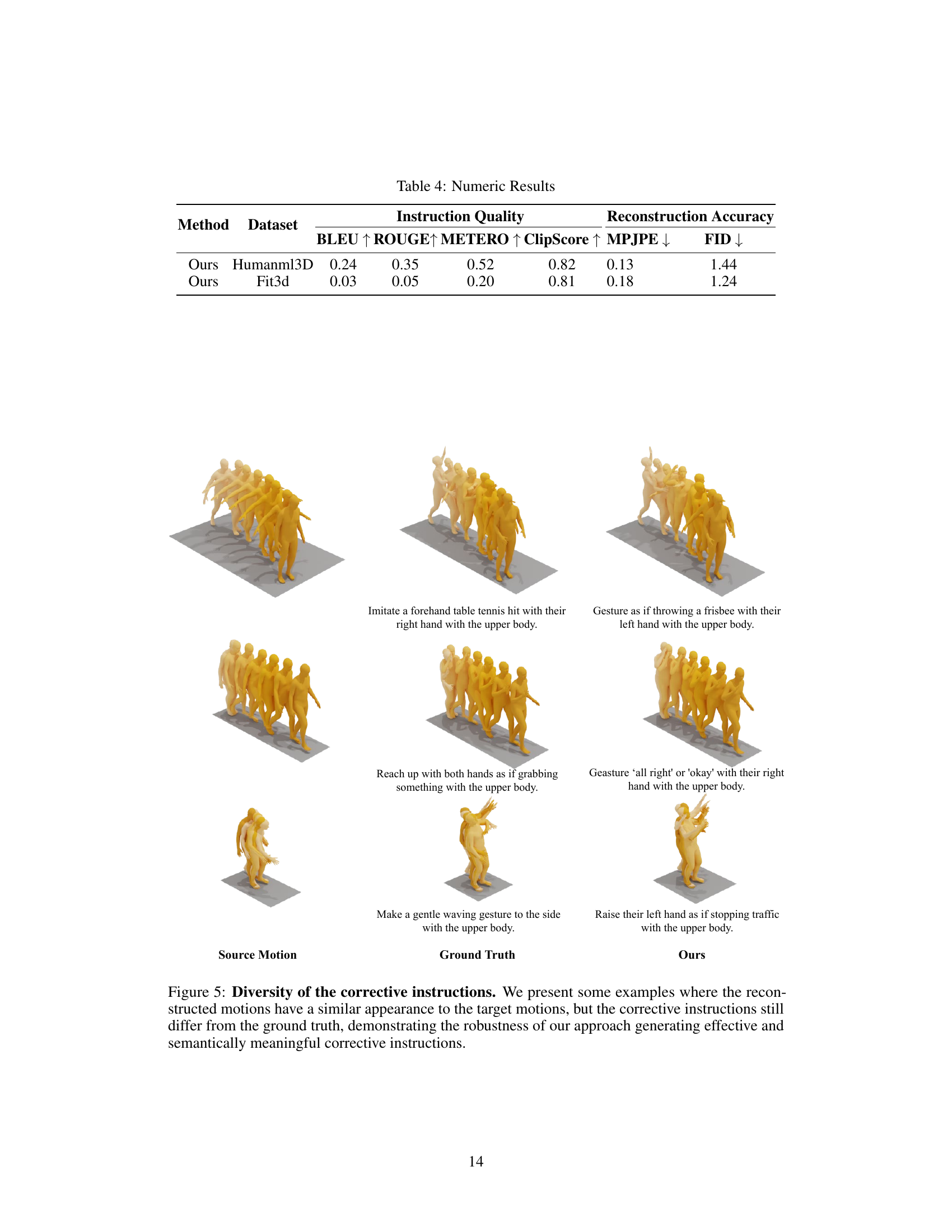

This figure showcases examples where the generated motion closely matches the target motion despite differences in the corrective instructions given. It highlights the model’s ability to produce effective corrections even when the instructions aren’t verbatim matches to the ground truth.

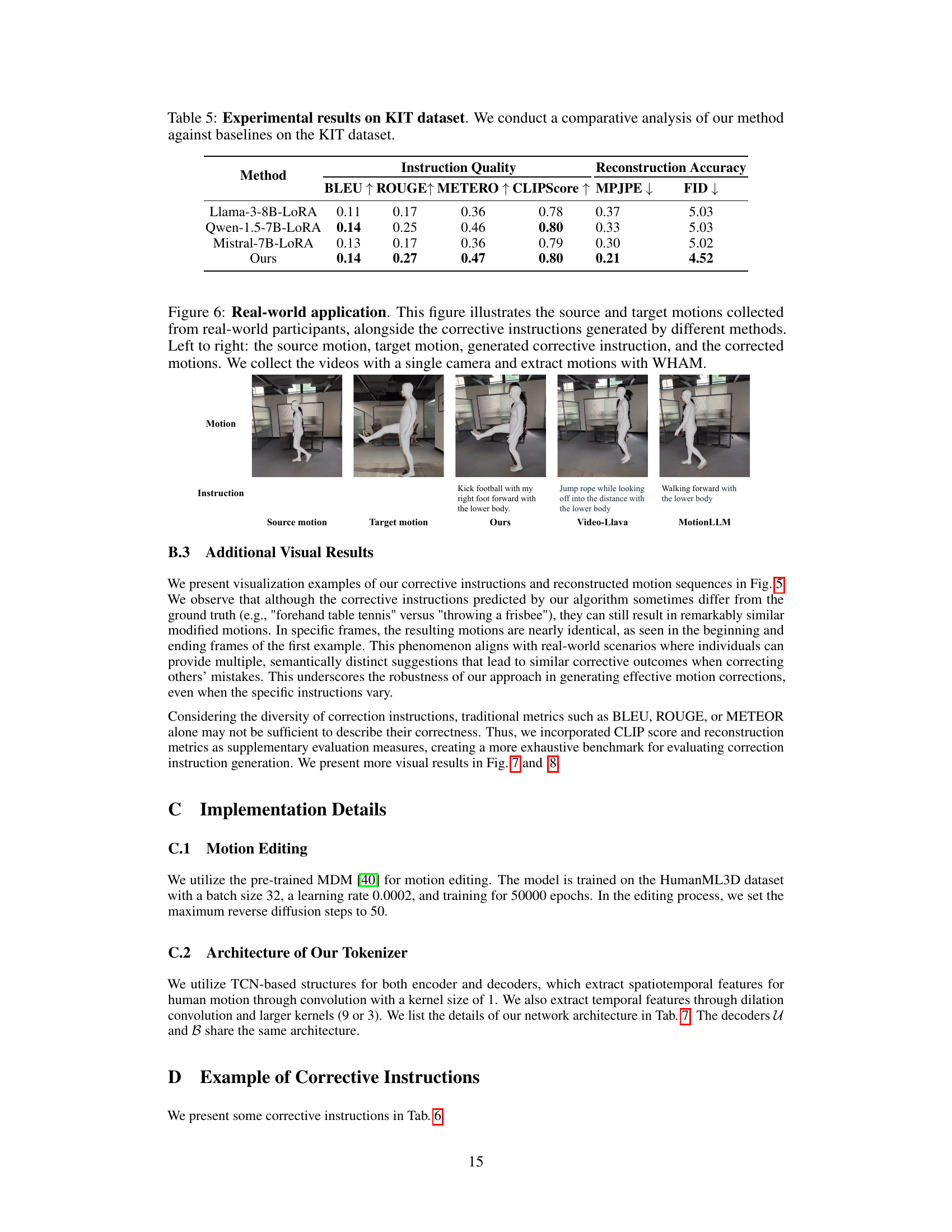

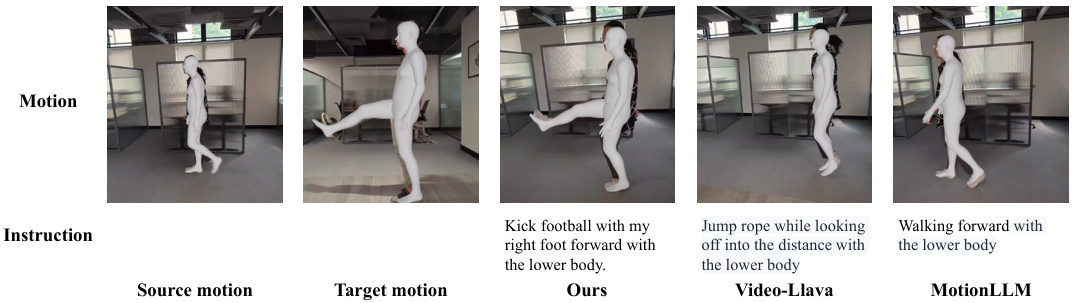

This figure showcases a real-world application of the proposed method. It demonstrates the process using videos recorded with a single camera. WHAM (an algorithm) extracts motion data from these videos. The figure presents pairs of source and target motions, along with the corrective instruction generated by the CigTime model and other baselines (Video-Llama and MotionLLM). The results show the corrected motions obtained using each approach.

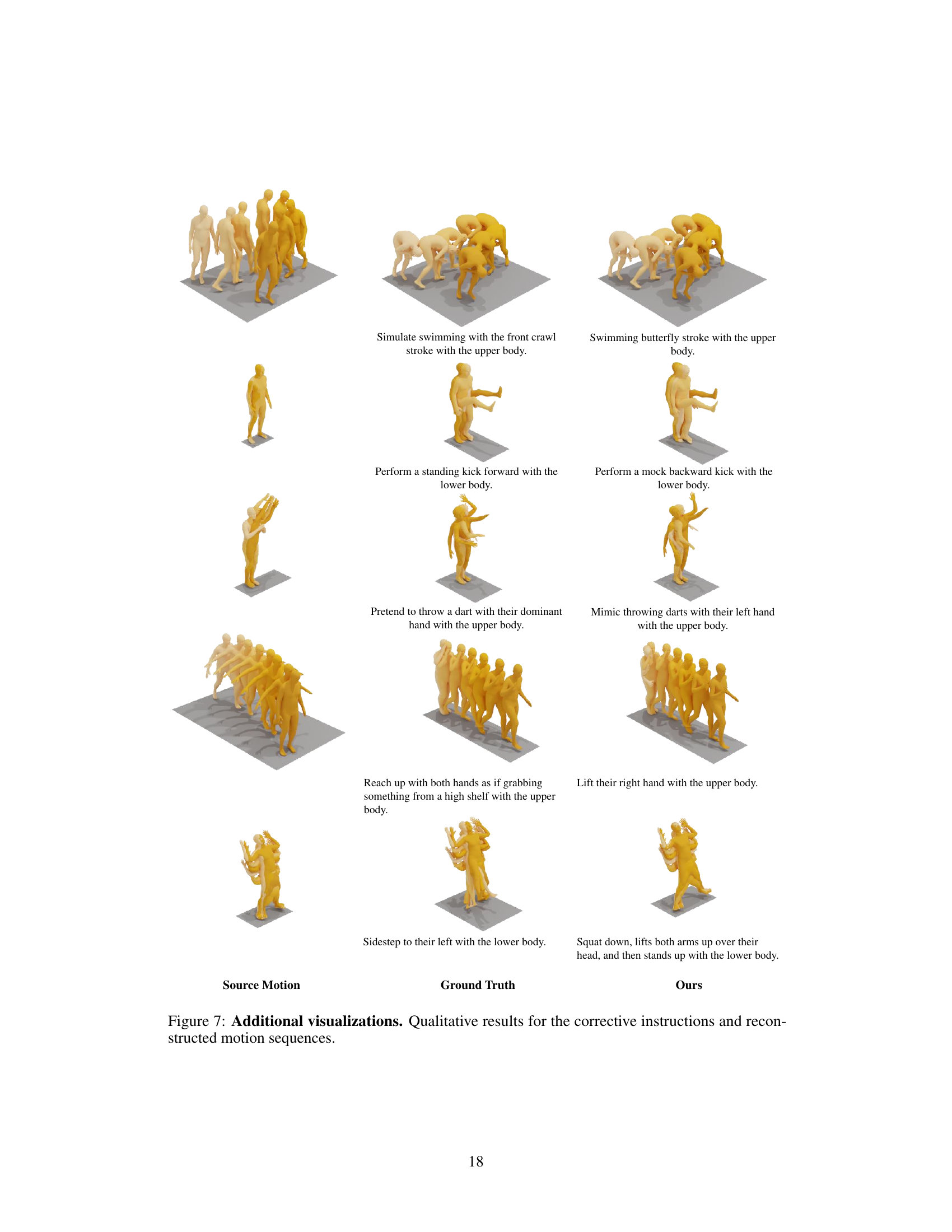

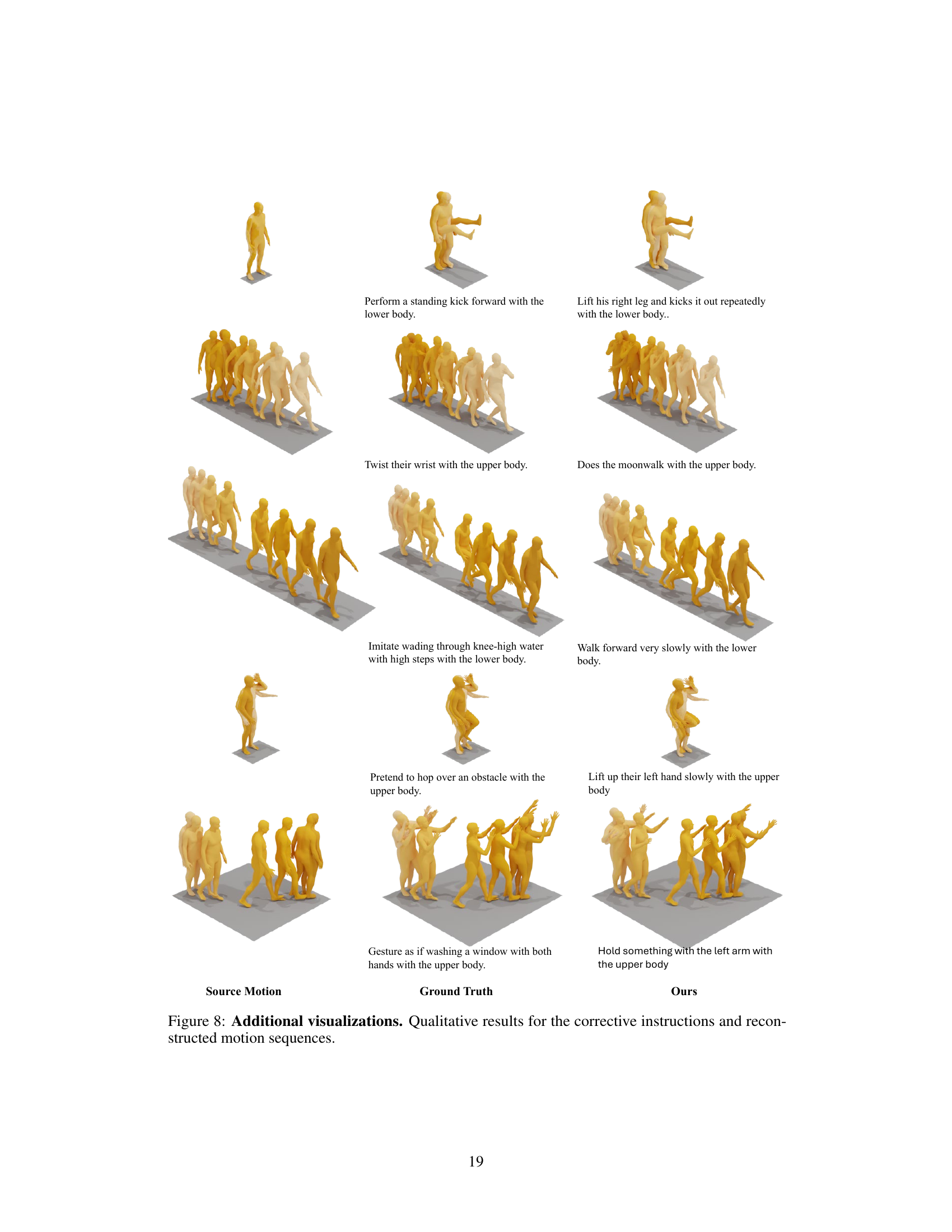

This figure presents several examples of how the CigTime model generates corrective instructions and the resulting motion sequences. For each example, it shows the original source motion, the desired target motion (ground truth), the corrective instructions generated by CigTime, and the reconstructed motion sequence after applying the instructions. The figure aims to visually demonstrate the effectiveness of CigTime in generating accurate and semantically meaningful instructions that lead to corrected motions.

This figure visualizes several examples of the corrective instruction generation process. It shows the source motion (the initial, incorrect movement), the ground truth target motion (the ideal, correct movement), and the motion generated by the CigTime model after applying the corrective instructions generated by the model. Each row represents a different motion pair and demonstrates how the model attempts to guide the user from an incorrect motion toward the correct one. The visualization highlights the system’s ability to generate diverse, plausible, and semantically meaningful corrective instructions, even when there may be multiple ways to achieve the same result.

More on tables

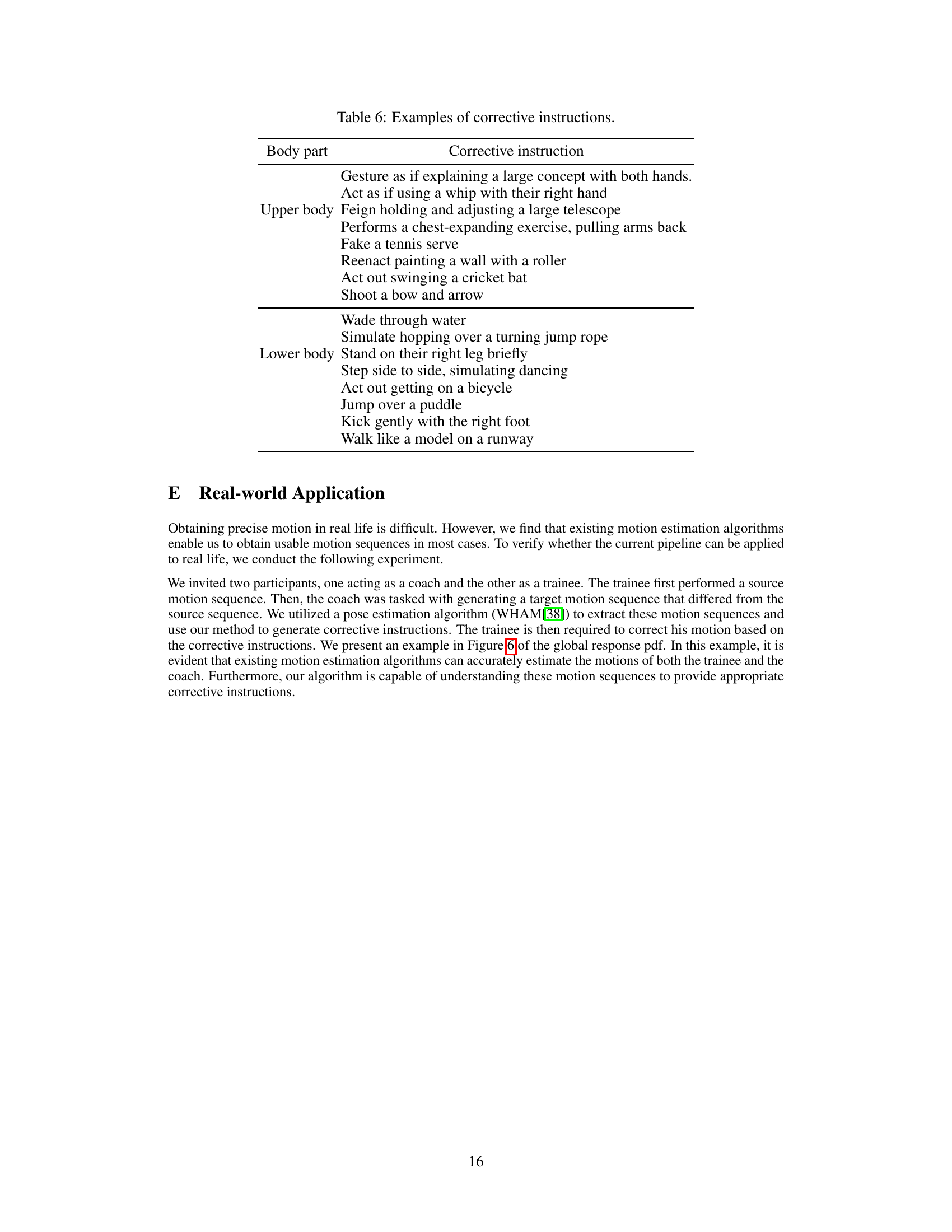

This table compares the performance of the proposed CigTime model against several baselines on the task of corrective instruction generation for human motion. The baselines include several large language models (LLMs) and motion-language models. The results are presented in terms of instruction quality metrics (BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, CLIPScore) and reconstruction accuracy metrics (MPJPE, FID). The table demonstrates that CigTime significantly outperforms all baselines, showcasing its effectiveness in this task.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method (CigTime) against various baselines for corrective instruction generation in human motion. It uses metrics reflecting both the quality of generated instructions (BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, CLIPScore) and the accuracy of reconstructing target motion (MPJPE, FID). The results demonstrate a significant improvement of CigTime over the baselines.

This table compares the proposed method (CigTime) against several baseline methods for corrective instruction generation. The baselines include large language models (LLMs) like Llama-3-8B, and motion-language models such as MotionGPT. The comparison uses metrics evaluating both the quality of the generated instructions (BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, CLIPScore) and the accuracy of reconstructing the target motion based on the generated instructions (MPJPE, FID). The results show CigTime significantly outperforms all baselines across all metrics.

This table compares the performance of the proposed CigTime model against various baseline models for corrective instruction generation. The baselines include large language models (LLMs) like Llama, Qwen, and Mistral, both with and without LoRA adaptation, and motion-language models like MotionGPT (with and without M2T adaptation). The comparison is based on instruction quality metrics (BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, CLIPScore) and reconstruction accuracy metrics (MPJPE, FID). The results show that CigTime significantly outperforms all baselines.

This table compares the performance of the proposed method, CigTime, against several baselines for corrective instruction generation. The baselines include large language models (LLMs) such as Llama-3-8B, and motion-language models like MotionGPT. The table presents quantitative results using metrics like BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, CLIPScore, MPJPE, and FID to evaluate both the quality of the generated instructions and the accuracy of the motion reconstruction after applying those instructions. The results show CigTime significantly outperforms all baselines across all metrics.

This table compares the performance of the proposed CigTime method against several baseline methods for generating corrective instructions for human motion. The baselines include large language models (LLMs) like Llama-3-8B, and motion-language models such as MotionGPT. The comparison uses metrics related to instruction quality (BLEU, ROUGE, METEOR, CLIPScore) and reconstruction accuracy (MPJPE, FID) to assess how well each method generates instructions that lead to the desired motion correction.

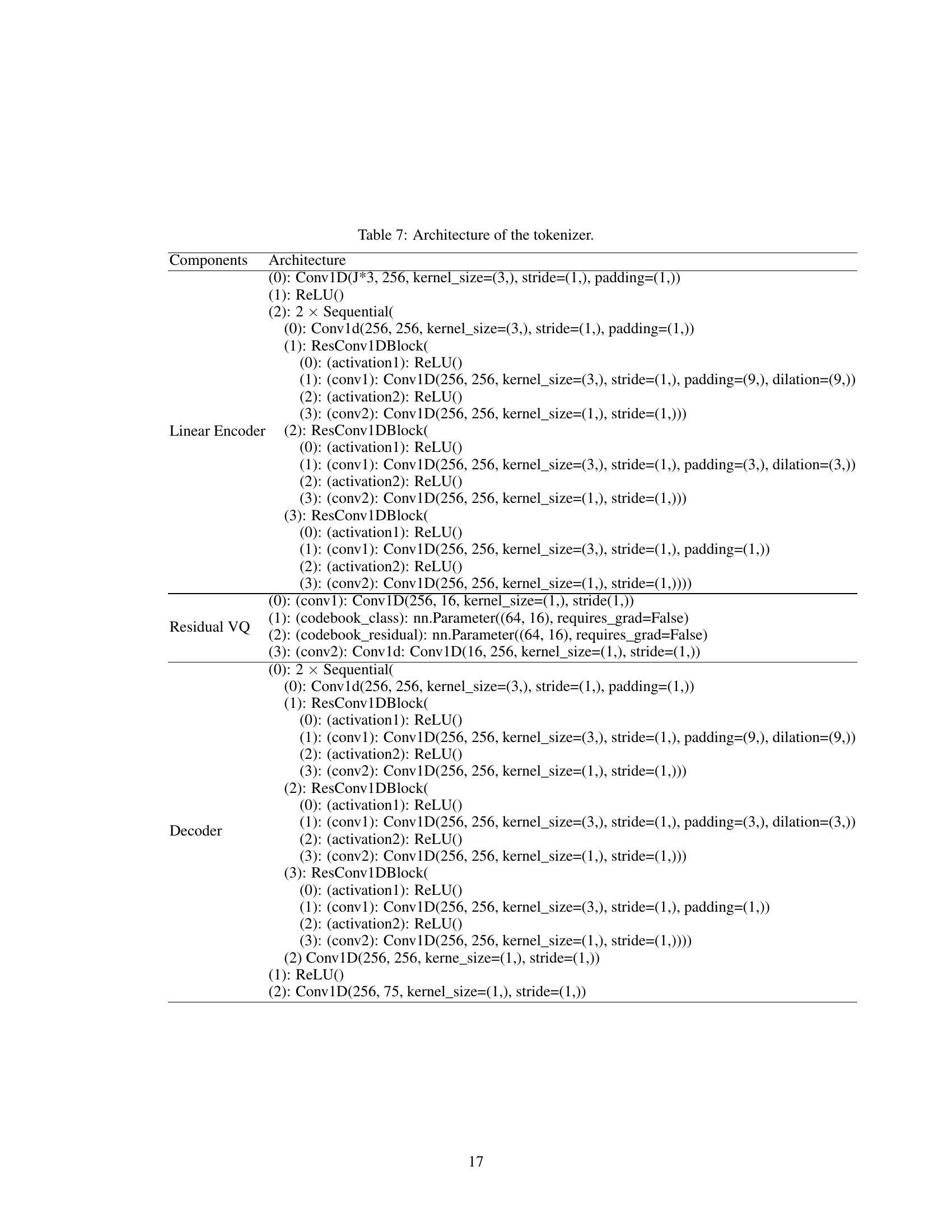

Full paper#