TL;DR#

Prior methods for controlling simulated humanoids to grasp and move objects often use disembodied hands or focus on limited scenarios, hindering their applicability. These methods struggle with the complexity of humanoid control, especially for dexterous manipulation involving diverse objects and trajectories. Additionally, obtaining and utilizing paired full-body motion and object trajectory data for training is challenging.

Omnigrasp tackles these issues using reinforcement learning and a novel universal and dexterous humanoid motion representation. This representation improves sample efficiency and allows the learning of grasping policies for a large number of objects without requiring paired full-body motion and object trajectory datasets. The learned controller demonstrates high success rates in grasping and following complex trajectories, showcasing its scalability and generalization capabilities. The method’s simplicity in reward and state design along with excellent performance makes it a substantial advance in the field.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is significant because it presents Omnigrasp, a novel approach to controlling simulated humanoids for object manipulation. It addresses the limitations of previous methods by using a universal and dexterous motion representation that significantly improves sample efficiency and generalizability. The work opens up new avenues for research in realistic human-object interaction within virtual environments and has potential implications for robotics and animation.

Visual Insights#

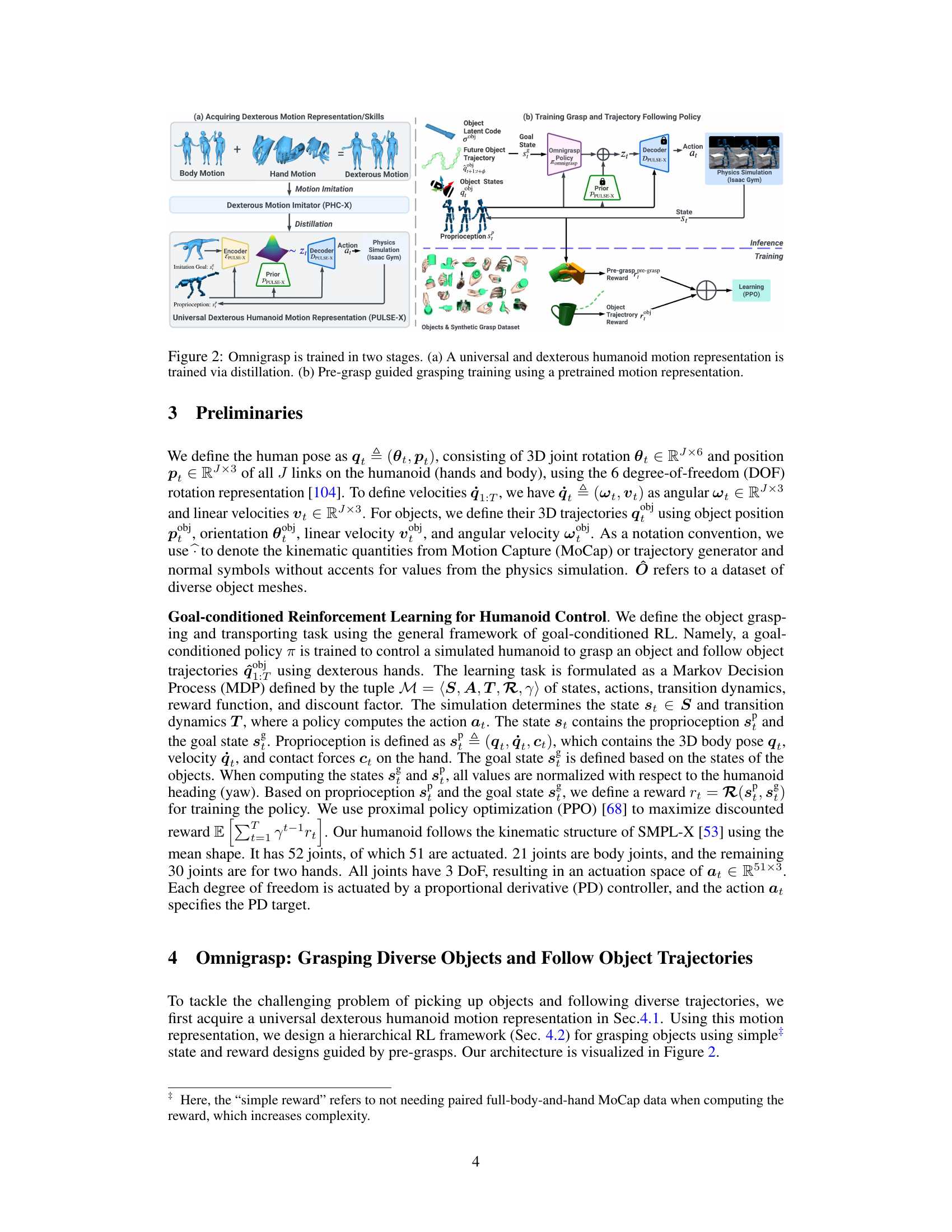

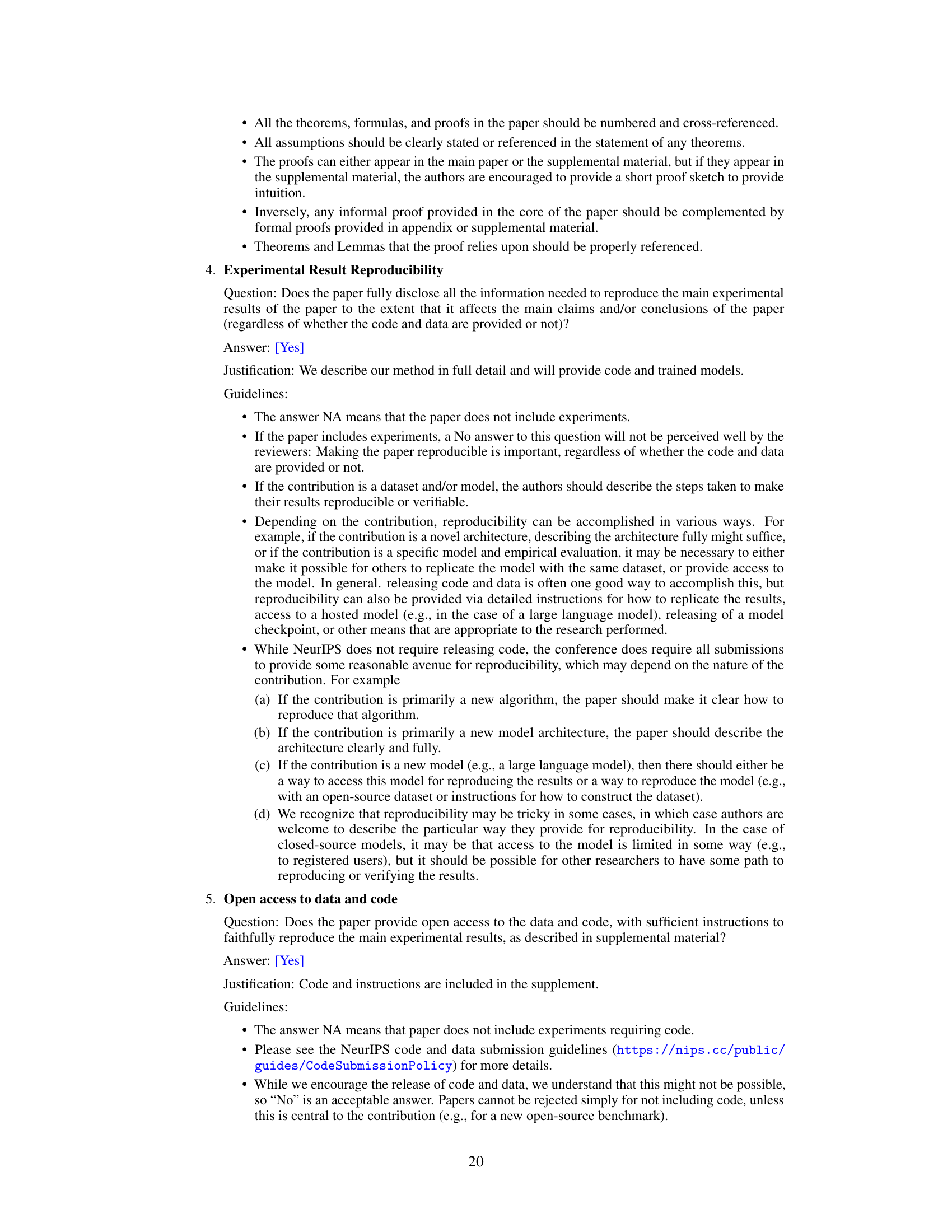

🔼 This figure shows the results of the Omnigrasp method, which controls a simulated humanoid to grasp diverse objects and follow complex trajectories. The top row shows the humanoid picking up and holding various objects, showcasing the diversity of objects the method can handle. The bottom row provides a closer look at the trajectory following. Green dots represent the reference trajectory, while pink dots represent the actual object trajectory, demonstrating the precision and accuracy of the method in guiding the object along the desired path.

read the caption

Figure 1: We control a simulated humanoid to grasp diverse objects and follow complex trajectories. (Top): picking up and holding objects. (Bottom): green dots - reference trajectory; pink dots - object trajectory.

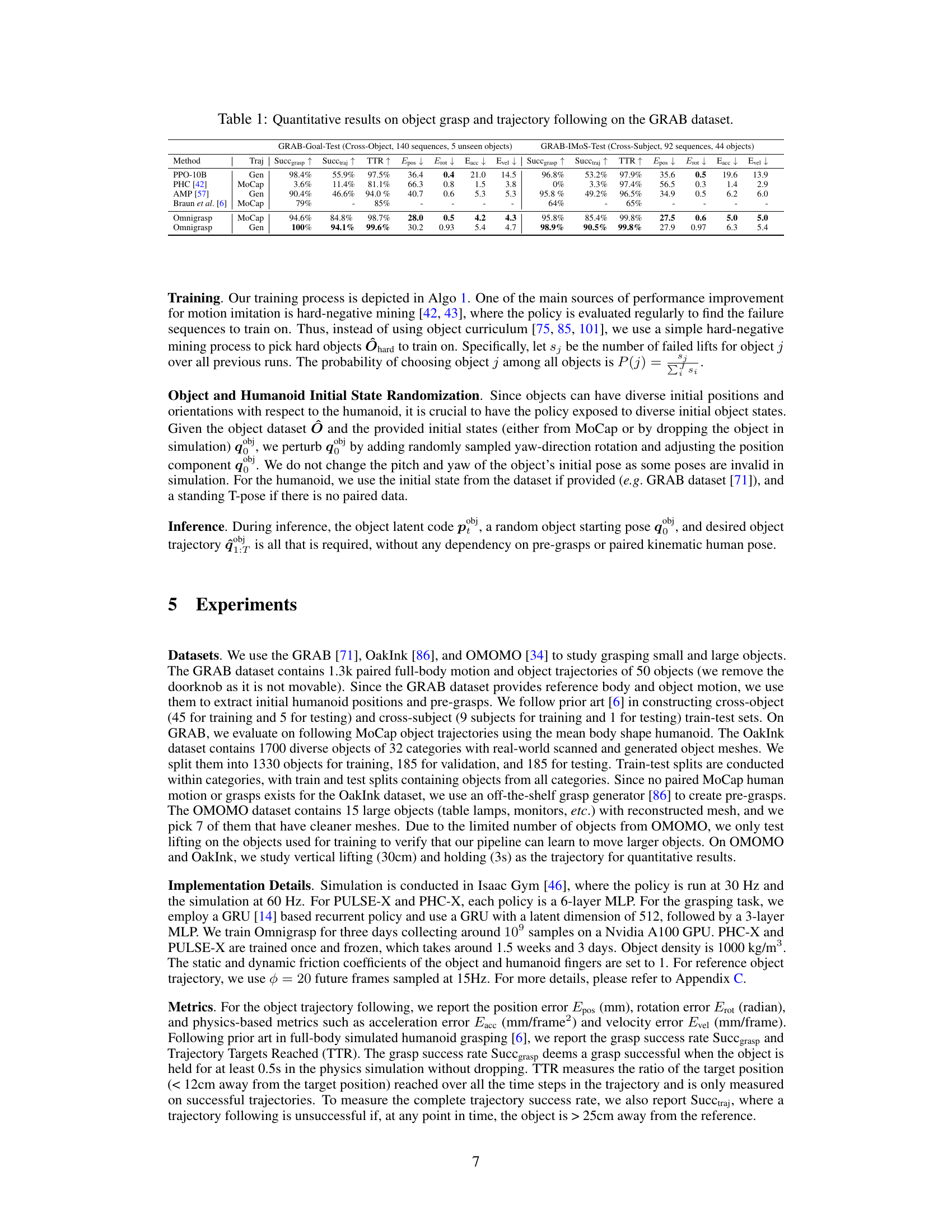

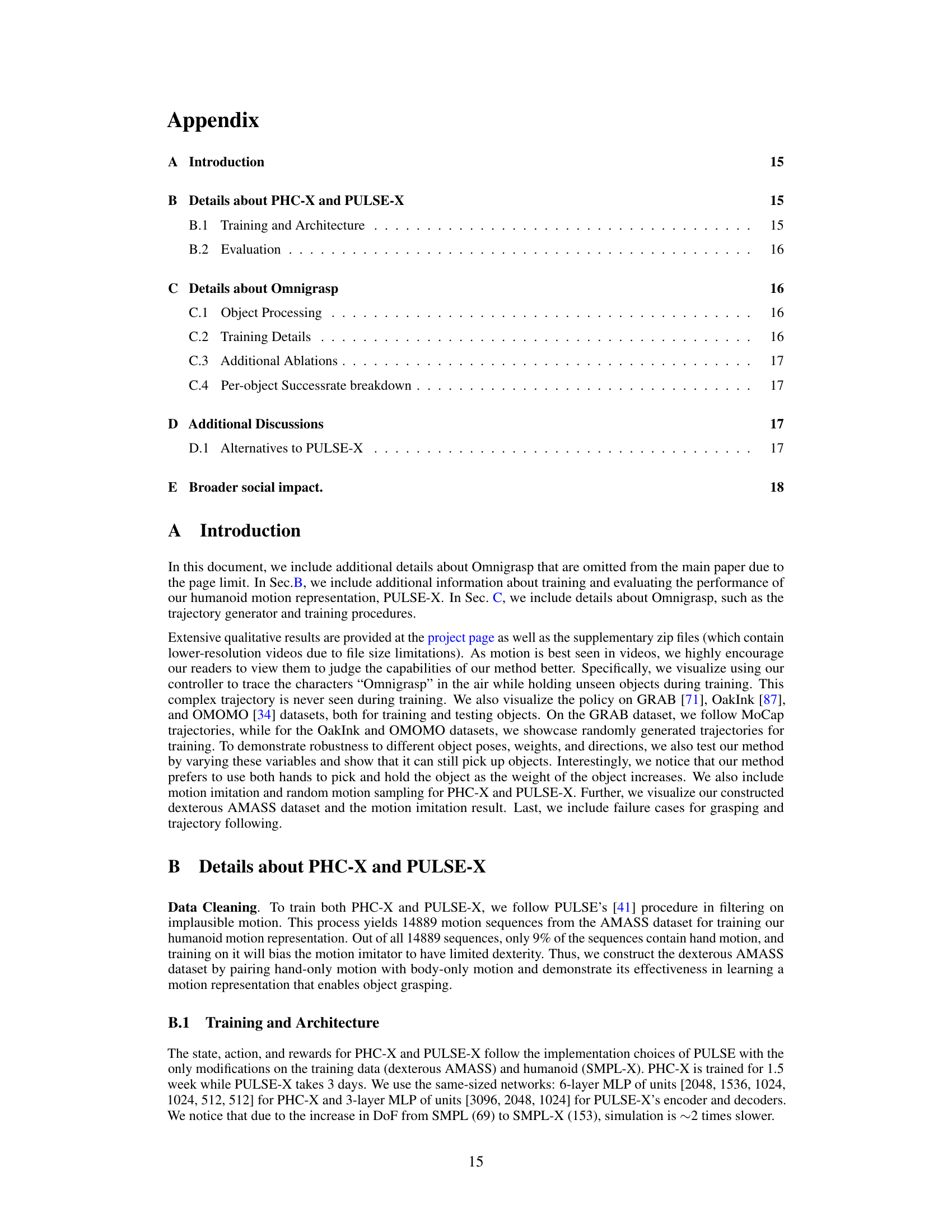

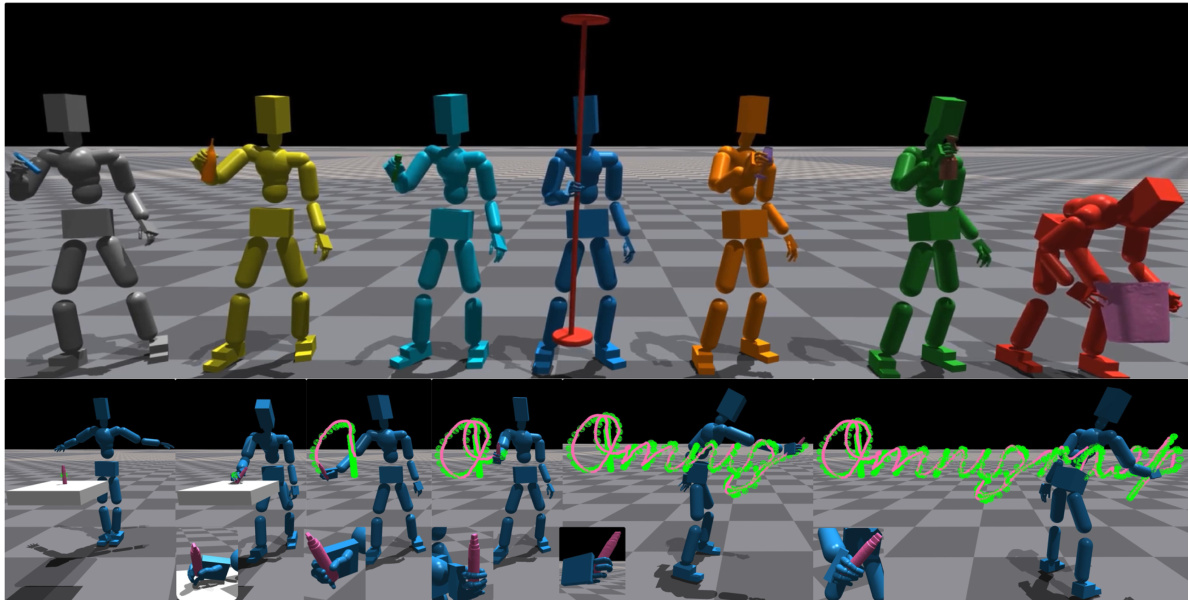

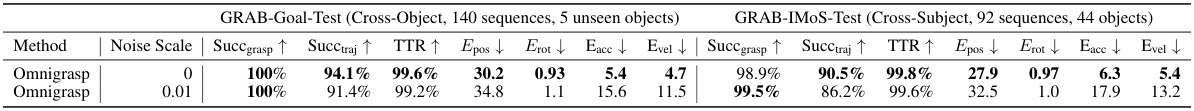

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for object grasping and trajectory following on the GRAB dataset. It shows the success rates for grasping (Succgrasp), successfully reaching trajectory targets (Succtraj), trajectory time taken (TTR), and various error metrics such as position error (Epos), rotation error (Erot), acceleration error (Eacc), and velocity error (Evel). The methods compared include PPO-10B, PHC, AMP, Braun et al., and two variants of the Omnigrasp method (one trained with MoCap data and one with generated data). The results are separated into two sections: GRAB-Goal-Test (cross-object) and GRAB-IMOS-Test (cross-subject).

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on object grasp and trajectory following on the GRAB dataset.

In-depth insights#

Dexterous Grasping#

Dexterous grasping, the ability of a robot hand to manipulate objects with dexterity and precision, is a significant challenge in robotics. Many existing methods simplify the problem by using disembodied hands or focusing on simple, pre-defined trajectories, limiting their real-world applicability. However, recent work focuses on using simulated humanoids to achieve more realistic and complex grasping. This approach offers several advantages: The inclusion of a full body allows for more natural movements and improved stability, unlike disembodied hands. Learning a controller directly on a high-degree-of-freedom humanoid can be difficult, but this challenge is often overcome through the use of advanced techniques, such as reinforcement learning (RL) and the use of pre-trained motion representations to guide the exploration process. A key challenge is the diversity of objects and trajectories. While some methods can grasp a limited set of objects successfully, scaling to a large number of diverse objects requires robust generalization techniques, often achieved by using feature representations that capture shape or other relevant object properties. Advances in the field, as reflected in recent research, leverage universal and dexterous motion representations and pre-grasp guided manipulation to overcome many of these limitations. These improvements significantly increase sample efficiency and enable the successful grasping and transportation of diverse objects along complex, randomly generated trajectories. Future work should focus on improving the robustness of these systems for real-world deployment and extending capabilities to include in-hand manipulation and more complex tasks.

RL for Humanoids#

Reinforcement learning (RL) presents a powerful paradigm for controlling humanoid robots, offering a data-driven approach to learn complex behaviors directly from interaction with the environment. The high dimensionality and complex dynamics of humanoids pose significant challenges for traditional control methods, making RL particularly attractive. However, sample inefficiency remains a major hurdle, demanding innovative techniques like curriculum learning, reward shaping, and efficient exploration strategies to accelerate training. Furthermore, transfer learning from simulation to the real world is crucial for practical applications, but bridging the reality gap due to model inaccuracies and sensor noise requires careful consideration. The choice of representation, whether it be joint angles, end-effector positions, or a higher-level abstraction, significantly impacts learning efficiency and generalization. Finally, developing methods for safe and robust RL is paramount for both simulated and real-world humanoids, requiring techniques to handle unexpected situations and prevent damage.

Motion Representation#

Effective motion representation is crucial for learning complex humanoid skills. A universal and dexterous representation, like PULSE-X, improves sample efficiency by providing a compact and expressive action space. Leveraging a pre-trained motion representation allows the model to learn grasping and trajectory following with simpler reward and state designs, avoiding the need for large datasets of paired full-body and object motions. The choice of representation directly impacts sample efficiency and the ability to learn complex, human-like movements. A well-designed motion representation, such as one that captures articulated finger movements, is key to enabling dexterous manipulation. The motion representation’s ability to generalize to unseen objects and trajectories significantly influences the overall performance and scalability of the system. A key advantage is reduced exploration complexity, resulting in faster learning and improved success rates. Therefore, careful design and selection of the motion representation are critical for efficient and effective humanoid control learning.

Scalability & Limits#

A crucial aspect of evaluating any novel method in robotics, particularly one involving complex tasks such as grasping and trajectory following, is its scalability and inherent limitations. Scalability refers to the system’s ability to generalize to new, unseen objects and diverse, complex trajectories beyond those encountered during training. In this context, a key question revolves around the controller’s capacity to adapt to vastly different object shapes, sizes, weights, and material properties without substantial retraining or performance degradation. Limits on the other hand, relate to the inherent constraints or bottlenecks of the proposed system; these could be computational (processing power, memory, training time), physical (dexterity limitations, sensor accuracy, actuation limits), or data-related (requirement for large labeled datasets). A truly robust and practical solution must address these factors, striving for high scalability while acknowledging and clearly defining its performance boundaries. The balance between generality and specificity, between what the system can handle effectively and where it begins to fail, is fundamental to a holistic assessment of the method.

Future of Omnigrasp#

The future of Omnigrasp hinges on addressing its current limitations and expanding its capabilities. Improving trajectory following accuracy is crucial, potentially through incorporating more sophisticated reward functions or advanced control techniques. Enhancing grasping diversity to handle a wider range of object shapes and sizes requires exploring more robust grasp planning and execution methods. Addressing the limitations of bi-manual manipulation is key; further research is needed to improve coordination between both hands for complex tasks. Sim-to-real transfer, a significant challenge, should be a major focus; techniques like domain randomization and robust policy learning are essential for bridging the gap between simulation and real-world robotics. Finally, exploring integration with vision-based systems will be critical for enabling Omnigrasp to operate autonomously in real-world environments, removing the dependence on pre-provided object meshes and trajectories. Ultimately, achieving seamless generalization to completely unseen objects and environments is the ultimate goal.

More visual insights#

More on figures

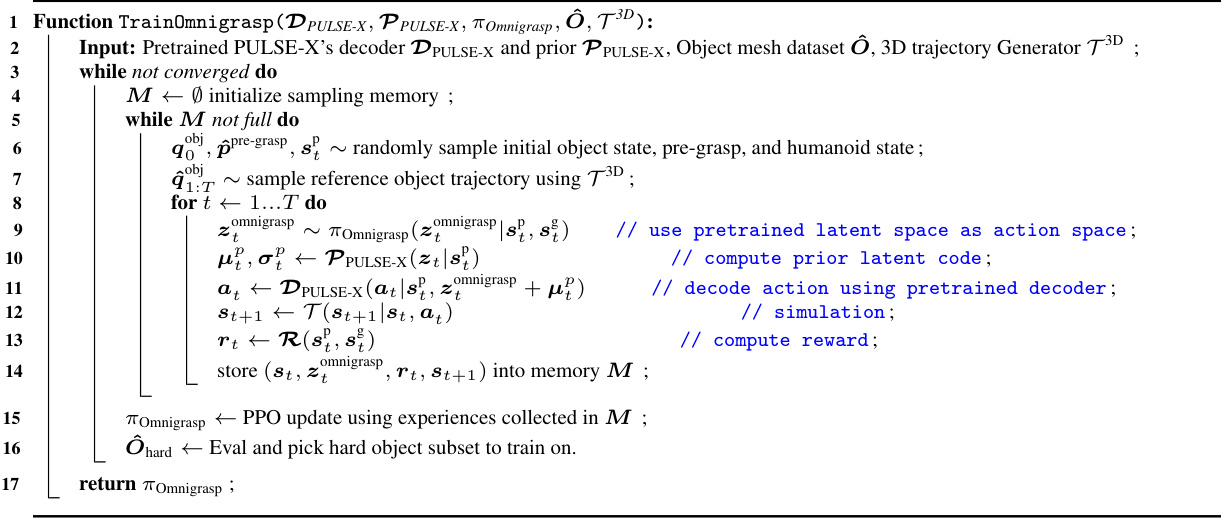

🔼 This figure illustrates the two-stage training process of Omnigrasp. The first stage (a) focuses on creating a universal and dexterous humanoid motion representation using a technique called distillation. This representation is then used in the second stage (b) to train a policy that enables the humanoid to grasp and follow trajectories using pre-grasp guidance. The figure shows the flow of information and the different components involved in each stage, including the use of a pretrained motion imitator and a physics simulator.

read the caption

Figure 2: Omnigrasp is trained in two stages. (a) A universal and dexterous humanoid motion representation is trained via distillation. (b) Pre-grasp guided grasping training using a pretrained motion representation.

🔼 This figure illustrates the two-stage training process of Omnigrasp. The first stage (a) focuses on learning a universal and dexterous humanoid motion representation using a technique called distillation. This representation serves as the foundation for the grasping policy. The second stage (b) trains a grasping policy that leverages the pre-trained motion representation. This stage uses a pre-grasp guided approach, meaning the policy is trained to initially position its hand for a successful grasp before attempting to lift the object.

read the caption

Figure 2: Omnigrasp is trained in two stages. (a) A universal and dexterous humanoid motion representation is trained via distillation. (b) Pre-grasp guided grasping training using a pretrained motion representation.

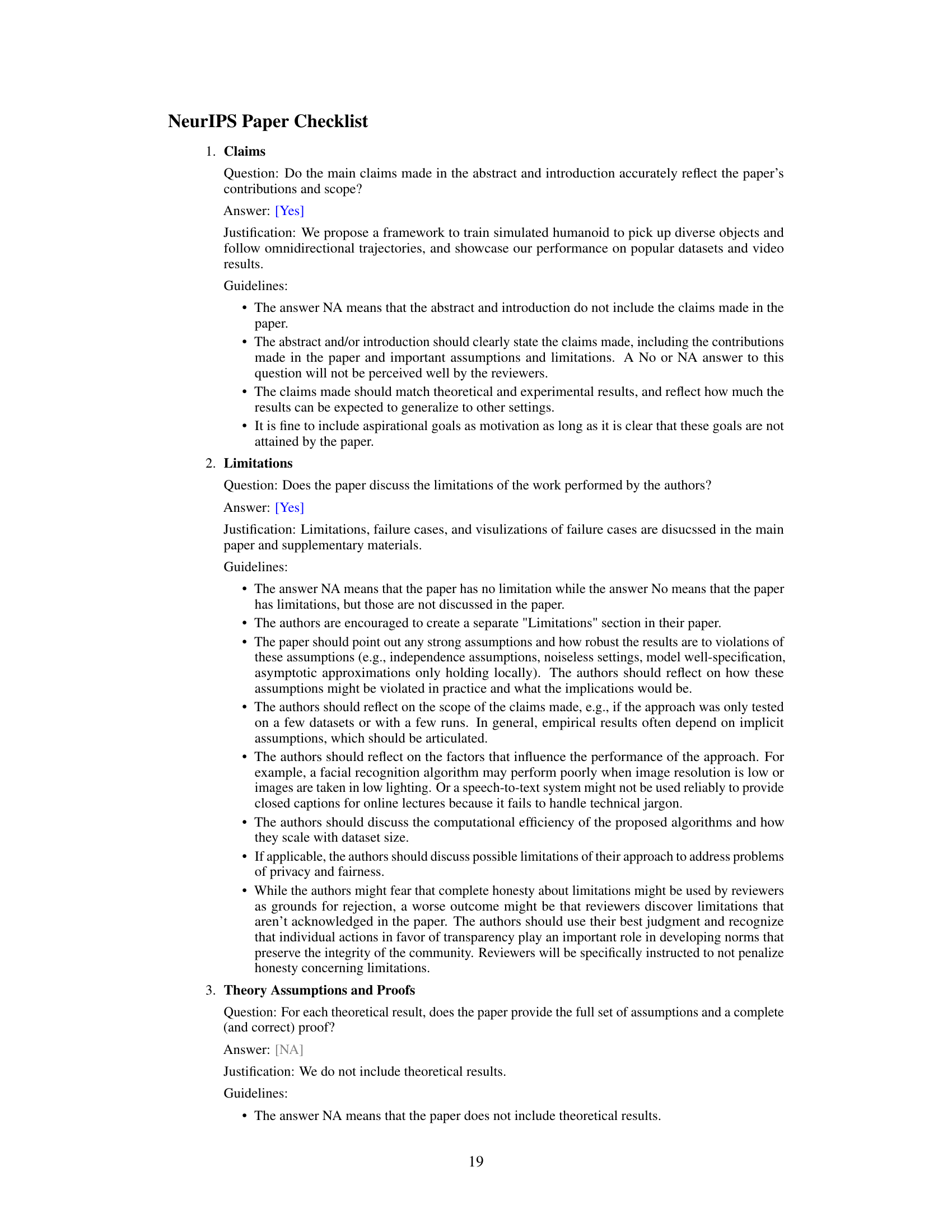

🔼 This figure shows qualitative results of the Omnigrasp approach on three different datasets: GRAB, OakInk, and OMOMO. For each dataset, several examples are shown of the simulated humanoid grasping and manipulating objects, following trajectories indicated by green dots (reference trajectory). The images demonstrate the method’s ability to handle diverse object shapes and to generalize to unseen objects (OakInk). The supplementary videos provide a more comprehensive view of the results.

read the caption

Figure 3: Qualitative results. Unseen objects are tested for GRAB and OakInk. Green dots: reference trajectories. Best seen in videos on our supplement site.

🔼 This figure shows the Omnigrasp system in action. The top row displays several examples of a simulated humanoid successfully grasping various objects. The bottom row illustrates the ability of the system to precisely follow complex trajectories: green dots represent the desired trajectory, and pink dots track the actual trajectory of the object being manipulated by the humanoid. This showcases the system’s control over both grasping and precise object movement.

read the caption

Figure 1: We control a simulated humanoid to grasp diverse objects and follow complex trajectories. (Top): picking up and holding objects. (Bottom): green dots - reference trajectory; pink dots - object trajectory.

More on tables

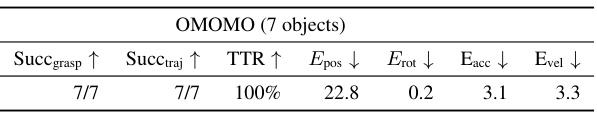

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the Omnigrasp method on the OakInk dataset. It shows the success rates for grasping (Succgrasp), successfully completing the trajectory (Succtraj), the time to reach the target (TTR), and various error metrics (position error Epos, rotation error Erot, acceleration error Eacc, and velocity error Evel). The results are broken down by the training data used: OakInk only, GRAB only, and a combination of both GRAB and OakInk. This allows for a comparison of the model’s performance when trained on a single dataset versus a combination of datasets, demonstrating the generalization capability of the model.

read the caption

Table 3: Quantitative results on OakInk with our method. We also test Omnigrasp cross-dataset, where a policy trained on GRAB is tested on the OakInk dataset.

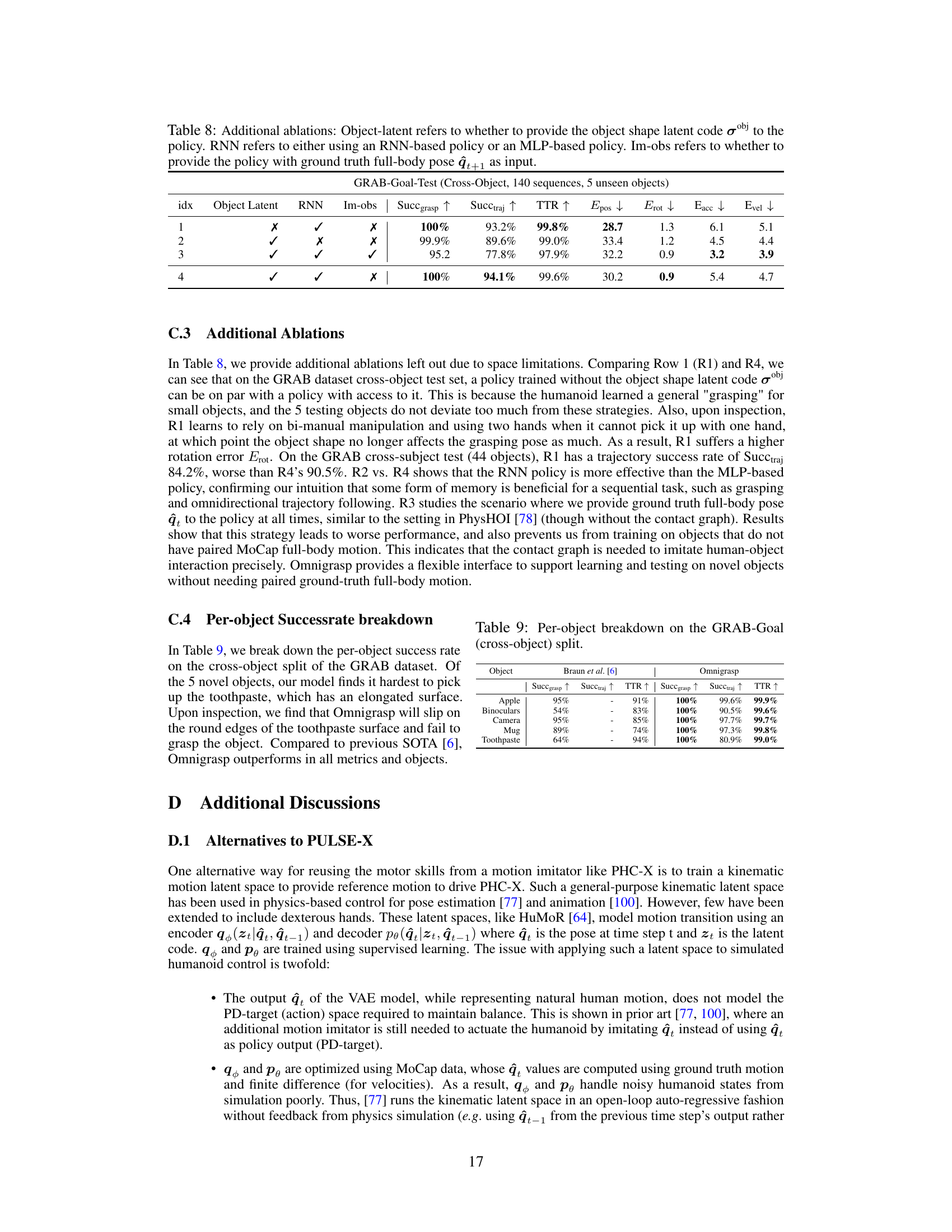

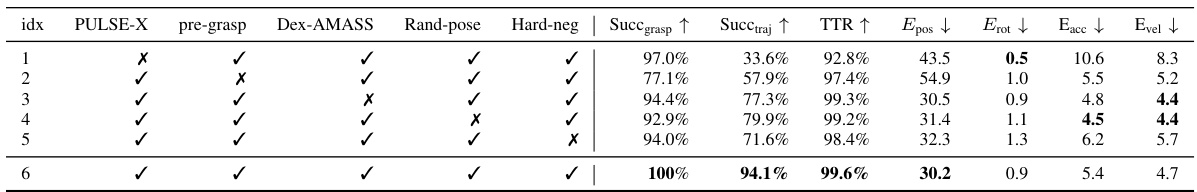

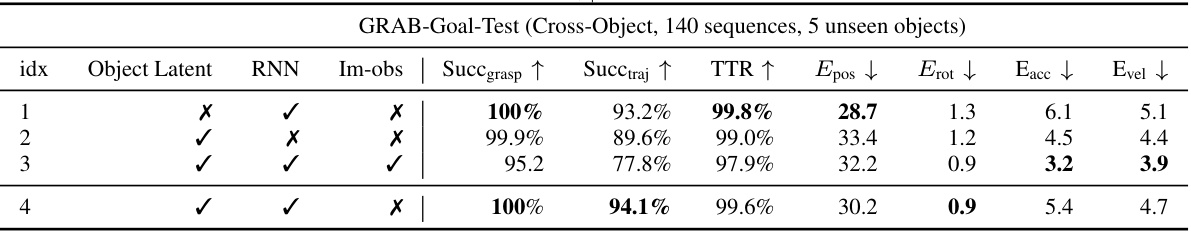

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study on the Omnigrasp training process. It evaluates the impact of several key components: using the PULSE-X latent motion representation, incorporating pre-grasp guidance in the reward, training PULSE-X on a dataset with articulated fingers (Dex-AMASS), randomizing the object’s initial pose, and employing hard-negative mining. Each row represents a different configuration, showing the effects on several metrics including grasp success rate, trajectory success rate, and error metrics.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation on various strategies of training Omnigrasp. PULSE-X: whether to use the latent motion representation. pre-grasp: pre-grasp guidance reward. Dex-AMASS: whether to train PULSE-X on the dexterous AMASS dataset. Rand-pose: randomizing the object initial pose. Hard-neg: hard-negative mining.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of Omnigrasp’s performance against other methods on the GRAB dataset for object grasping and trajectory following tasks. It shows success rates for grasping and trajectory completion (Succgrasp, Succtraj), time to reach the target (TTR), and errors in position, rotation, acceleration, and velocity (Epos, Erot, Eacc, Evel). The results are categorized by different methods and whether they use motion capture (MoCap) data or synthetically generated data.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on object grasp and trajectory following on the GRAB dataset.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for object grasping and trajectory following on the GRAB dataset. It shows the success rates for grasping (Succgrasp), successfully completing the trajectory (Succtraj), time to reach the target (TTR), and errors in position (Epos), rotation (Erot), acceleration (Eacc), and velocity (Evel). The results are broken down by method and whether the trajectory is generated from motion capture (MoCap) or synthetically (Gen). The table helps to evaluate the performance of Omnigrasp compared to other state-of-the-art methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on object grasp and trajectory following on the GRAB dataset.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of different methods for object grasping and trajectory following on the GRAB dataset. It includes metrics such as grasp success rate, trajectory success rate, time to reach the target, positional error, rotational error, acceleration error, and velocity error. The methods compared include PPO-10B, Gen, PHC [42], MoCap, AMP [57], Braun et al. [6], and Omnigrasp (using both MoCap and generated data). The results highlight the superior performance of Omnigrasp across various metrics.

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on object grasp and trajectory following on the GRAB dataset.

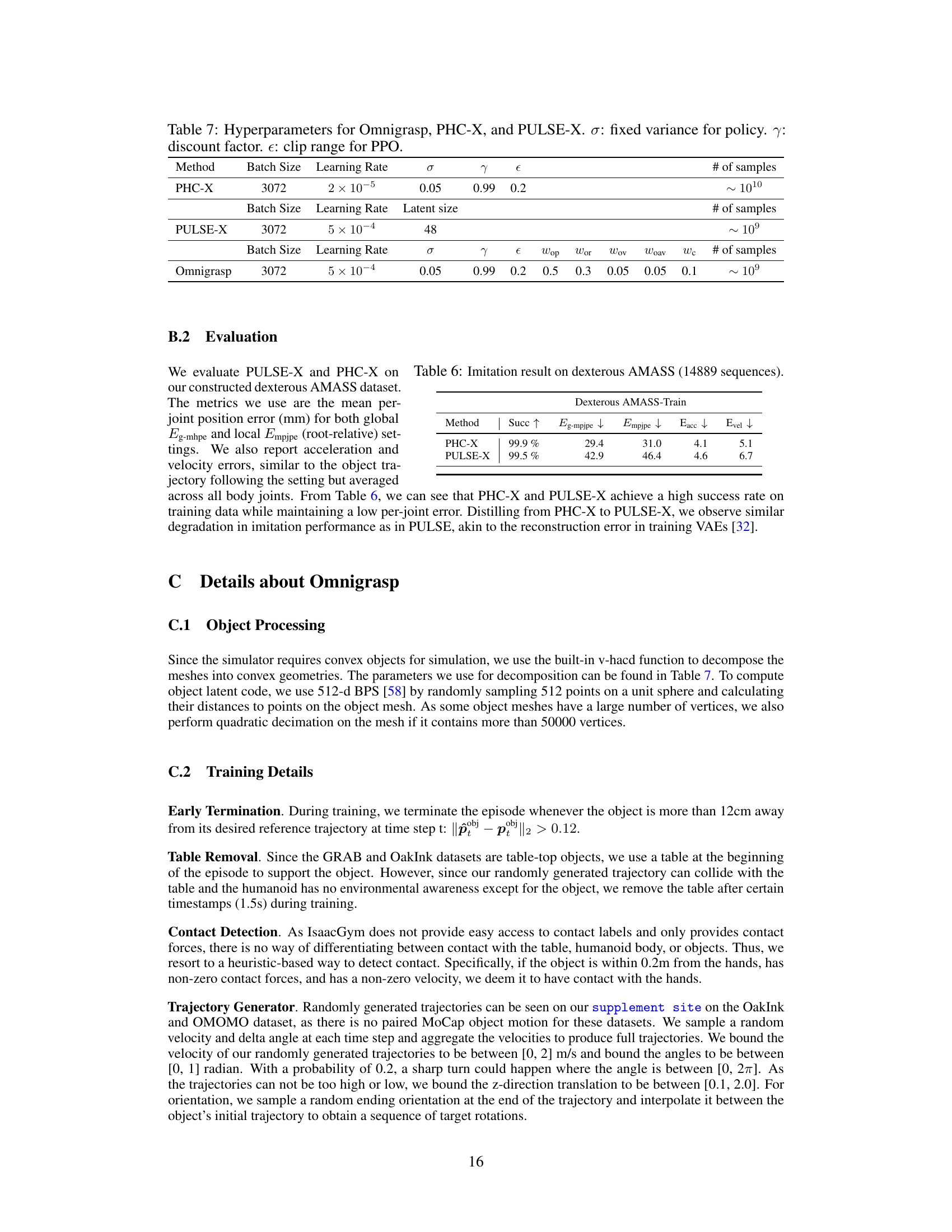

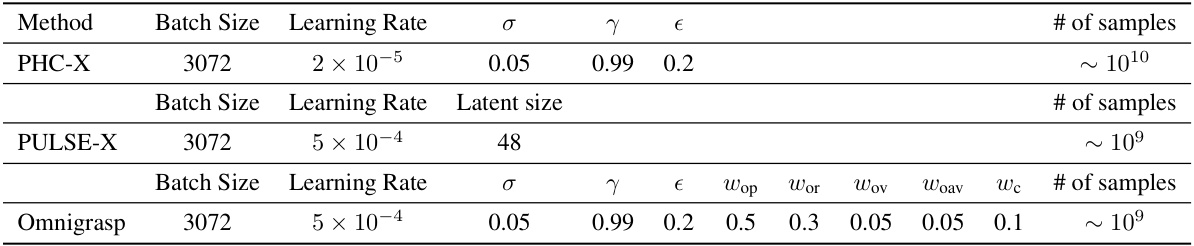

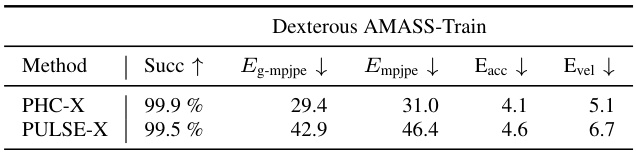

🔼 This table presents the quantitative results of the imitation task using the dexterous AMASS dataset. It compares the performance of two methods: PHC-X and PULSE-X. The metrics used include success rate (Succ), global mean per-joint position error (Eg-mpjpe), local mean per-joint position error (Empjpe), acceleration error (Eacc), and velocity error (Evel). Lower values for error metrics indicate better performance. The results show that both methods achieve a high success rate, but PHC-X has lower error values.

read the caption

Table 6: Imitation result on dexterous AMASS (14889 sequences).

🔼 This table presents the results of ablation studies on the Omnigrasp training process. It shows the impact of several key components: using the universal motion representation (PULSE-X), incorporating pre-grasp guidance in the reward, training PULSE-X on the extended AMASS dataset, randomizing object initial poses, and utilizing hard-negative mining. The performance metrics (grasp success rate, trajectory following success rate, etc.) are compared across different combinations of these components, revealing their individual contributions to the overall success of the Omnigrasp system.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation on various strategies of training Omnigrasp. PULSE-X: whether to use the latent motion representation. pre-grasp: pre-grasp guidance reward. Dex-AMASS: whether to train PULSE-X on the dexterous AMASS dataset. Rand-pose: randomizing the object initial pose. Hard-neg: hard-negative mining.

🔼 This table presents a quantitative comparison of Omnigrasp’s performance against other methods on the GRAB dataset for object grasping and trajectory following tasks. It shows success rates for grasping (Succgrasp), successfully reaching trajectory targets (Succtraj), trajectory time to reach (TTR), and error metrics for position (Epos), rotation (Erot), acceleration (Eacc), and velocity (Evel). The comparison includes results for different training methods (MoCap vs. generated trajectories) and baselines (PPO-10B, PHC [42], AMP [57], Braun et al. [6]).

read the caption

Table 1: Quantitative results on object grasp and trajectory following on the GRAB dataset.

Full paper#