TL;DR#

Conic optimization is essential for solving many real-world problems, but traditional methods can be slow and computationally expensive. Learning-based approaches offer the potential for faster solutions, but often lack strong theoretical guarantees. This paper addresses the challenges by focusing on learning dual solutions. Existing learning methods typically focus on learning primal (feasible) solutions. The need for dual solution methods is to validate the learned primal solutions and gain stronger theoretical support.

The proposed Dual Lagrangian Learning (DLL) method systematically leverages conic duality theory and machine learning to learn dual-feasible solutions. It introduces a novel dual conic completion procedure, differentiable conic projection layers, and a self-supervised learning framework based on Lagrangian duality. DLL provides closed-form dual completion for many problem types, eliminating the need for computationally expensive implicit layers. Empirical results show that DLL significantly outperforms a state-of-the-art baseline method and achieves 1000x speedups over traditional interior-point solvers with optimality gaps under 0.5% on average.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel and efficient methodology for learning dual solutions in conic optimization, a crucial aspect of many real-world problems. It offers significant speedups over traditional solvers and provides strong feasibility guarantees, opening new avenues for research in combining machine learning and optimization.

Visual Insights#

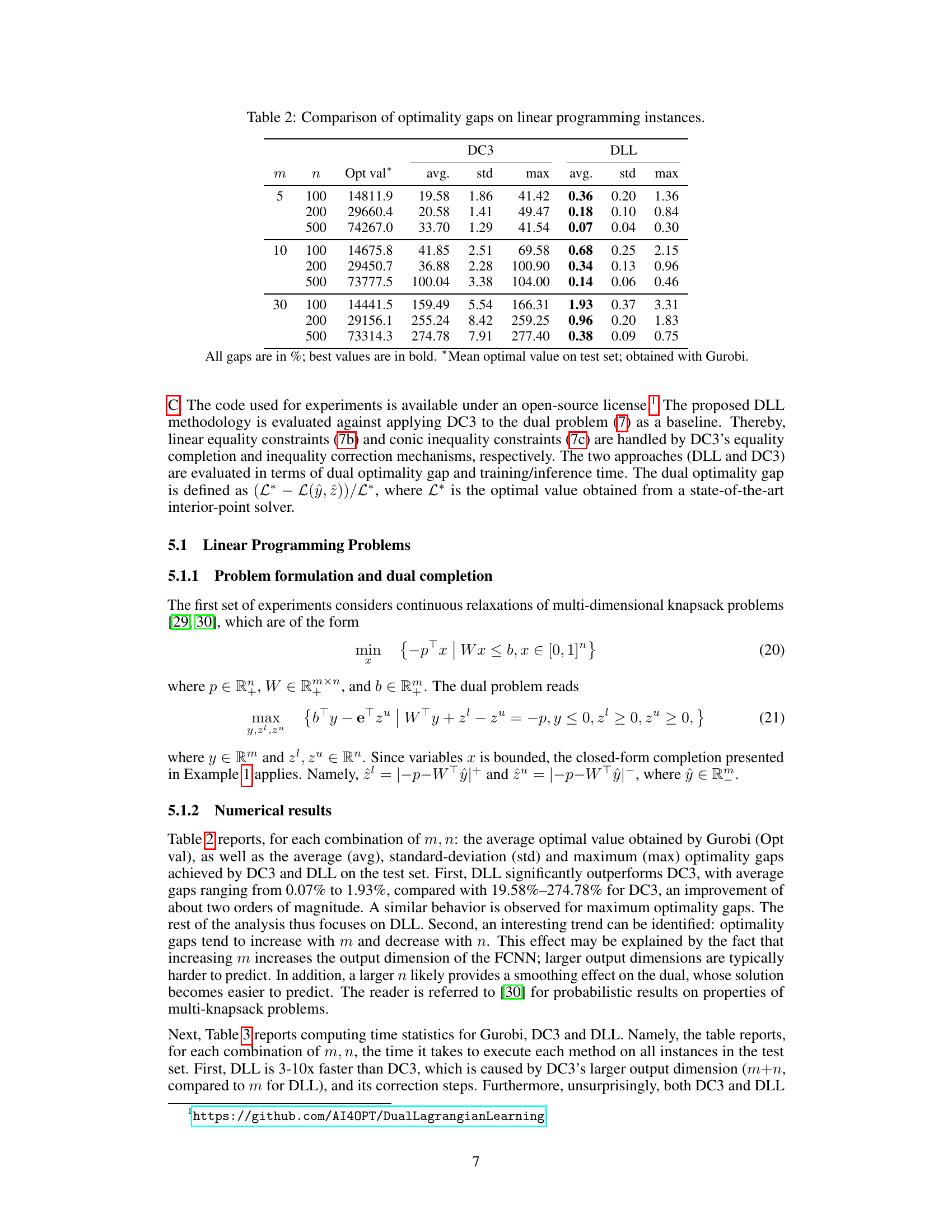

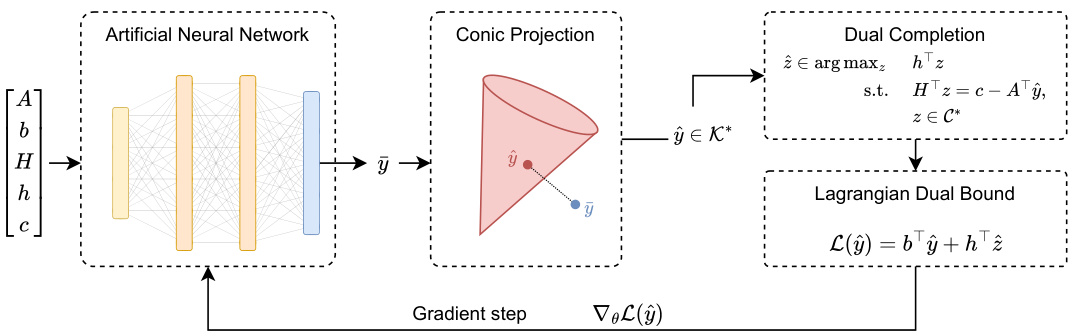

🔼 The figure illustrates the Dual Lagrangian Learning (DLL) scheme. It shows how a neural network, given input data (A, b, H, h, c), predicts a dual variable y. This y is then projected onto the feasible region K* using a conic projection layer to produce a conic feasible ŷ. Then, a dual completion procedure completes ŷ into a full dual feasible solution (ŷ, ẑ). The model is trained by maximizing the Lagrangian dual bound L(ŷ) using a gradient step. The figure also highlights the three fundamental building blocks of DLL: (1) dual conic completion, (2) conic projection layers, and (3) a self-supervised learning algorithm.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the proposed DLL scheme. Given input data (A, b, H, h, c), a neural network first predicts y ∈ Rn. Next, a conic projection layer computes a conic-feasible ŷ ∈ K*, which is then completed into a full dual-feasible solution (ŷ, ẑ). The model is trained in a self-supervised fashion, by updating the weights θ to maximize the Lagrangian dual bound L(ŷ).

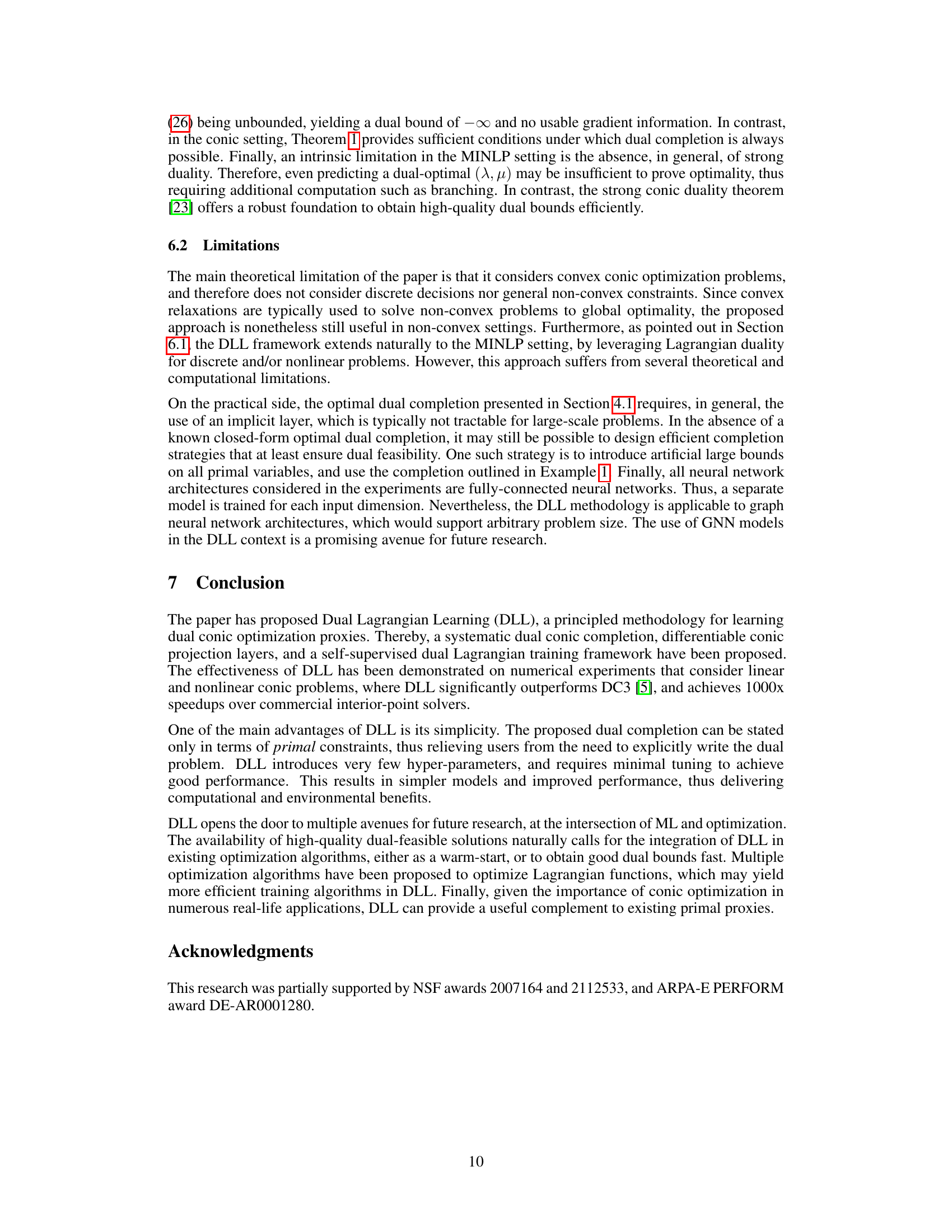

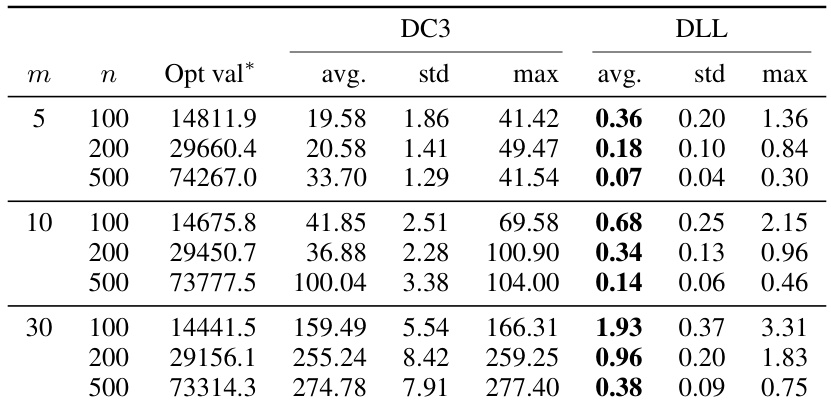

🔼 This table compares the performance of the proposed Dual Lagrangian Learning (DLL) method and the baseline method DC3 on linear programming instances. It shows the average, standard deviation, and maximum optimality gaps for both methods across different problem sizes (m and n). The optimality gap is calculated as the difference between the optimal objective value and the dual bound obtained by the method, divided by the optimal objective value. The results demonstrate that DLL significantly outperforms DC3 in terms of accuracy, achieving much lower optimality gaps.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of optimality gaps on linear programming instances.

In-depth insights#

Conic Duality Learning#

Conic duality learning presents a novel approach to tackling optimization problems by leveraging the power of conic duality and machine learning. It’s a principled methodology that addresses a gap in existing techniques, which largely focus on learning primal solutions. The core idea is to learn dual-feasible solutions, providing valid Lagrangian dual bounds and effectively certifying the quality of learned primal solutions. This approach offers the significant benefit of providing quality certificates for learned solutions, a feature lacking in many existing primal-only methods. The framework combines the representational power of neural networks with the theoretical guarantees of conic duality. Efficient dual conic completion techniques are central, providing dual-feasible solutions, even for complex problem structures, and differentiable conic projection layers ensure the feasibility of the learned solutions. The self-supervised learning aspect further enhances its efficacy, enabling training without requiring labeled dual solutions. Overall, this method promises to provide more reliable and trustworthy solutions to a wide range of optimization challenges.

Dual Conic Completion#

The concept of “Dual Conic Completion” presented in the research paper is a crucial technique for ensuring the feasibility and quality of dual solutions in conic optimization problems. The core idea revolves around systematically constructing a complete dual solution from a partially known dual solution that only satisfies some but not all constraints. The method is important because it guarantees the feasibility of the learned dual solution, which is a critical requirement for obtaining valid dual bounds. It leverages conic duality and exploits properties of conic optimization to efficiently and effectively complete the dual solution without resorting to computationally expensive iterative methods. The closed-form solutions provided for specific types of conic problems further enhance the efficiency and practicality of the approach, making it readily applicable in various settings. The approach directly impacts model training, allowing self-supervised learning of a high-quality dual proxy. This dual proxy enables robust verification of primal solution quality and opens avenues for leveraging dual information in optimization algorithms.

Projection Layers#

Projection layers are crucial in neural networks designed for constrained optimization problems, as they ensure that the network’s output remains within the feasible region defined by the constraints. The choice of projection method significantly impacts the efficiency and effectiveness of the model. Euclidean projections, while straightforward, can be computationally expensive, especially for high-dimensional problems or complex constraint sets. Radial projections, offering a potentially faster alternative, require careful selection of the ray, impacting accuracy. The paper highlights a need for differentiable projection layers to enable efficient backpropagation during training. Closed-form solutions for projections, where available, are highly desirable to avoid the computational overhead of iterative methods. This is especially relevant for conic optimization, where specialized cones such as second-order cones and positive semidefinite cones exist, each potentially requiring unique projection strategies.

Lagrangian Training#

Lagrangian training, in the context of machine learning for optimization, is a powerful technique for learning dual solutions to conic optimization problems. It leverages the Lagrangian dual function, which provides a lower bound on the optimal primal solution value. By designing a self-supervised learning framework based on Lagrangian duality, models are trained to maximize this dual bound. This approach offers several advantages, including the generation of valid dual bounds, which certify the quality of learned primal solutions and provide a measure of suboptimality. Furthermore, it can result in significant computational speedups compared to traditional methods like interior point solvers. Conic duality theory is critical here; it provides a structured way to learn dual-feasible solutions, guaranteeing quality and feasibility. A key element is often the use of differentiable conic projection layers which maintain dual feasibility during model training. However, limitations exist, notably the current focus on convex conic optimization problems. Future research might explore extending these methods to non-convex settings or to handle the complexities of mixed-integer programming problems.

MINLP Extensions#

The heading ‘MINLP Extensions’ suggests a discussion on extending the proposed methodology to Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP) problems. This is a significant step, as MINLPs are considerably more complex than the conic optimization problems initially addressed. The challenges would involve handling the non-convexity and integer variables inherent in MINLPs, which necessitate different optimization techniques than those suitable for convex conic problems. The authors might explore the use of Lagrangian relaxations, branch-and-bound methods, or other suitable approaches for handling integer constraints and non-convexity within the developed framework. Adapting the dual completion and conic projection methods to this more challenging problem domain would be crucial. Furthermore, the success of such an extension would likely depend on the structure of the MINLP; specific problem classes might be more amenable to this approach than others. Successfully extending to MINLPs would significantly broaden the applicability of the proposed methodology and highlight its robustness.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 The figure illustrates the Dual Lagrangian Learning (DLL) methodology. It shows the process of taking input data (A, b, H, h, c), using a neural network to predict a dual variable (y), projecting it onto a feasible space (ŷ ∈ K*), completing it to a full dual-feasible solution (ŷ, z), and then training the model to maximize the Lagrangian dual bound, using a self-supervised learning approach.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the proposed DLL scheme. Given input data (A, b, H, h, c), a neural network first predicts y ∈ Rn. Next, a conic projection layer computes a conic-feasible ŷ ∈ K*, which is then completed into a full dual-feasible solution (ŷ, 2). The model is trained in a self-supervised fashion, by updating the weights θ to maximize the Lagrangian dual bound L(ŷ).

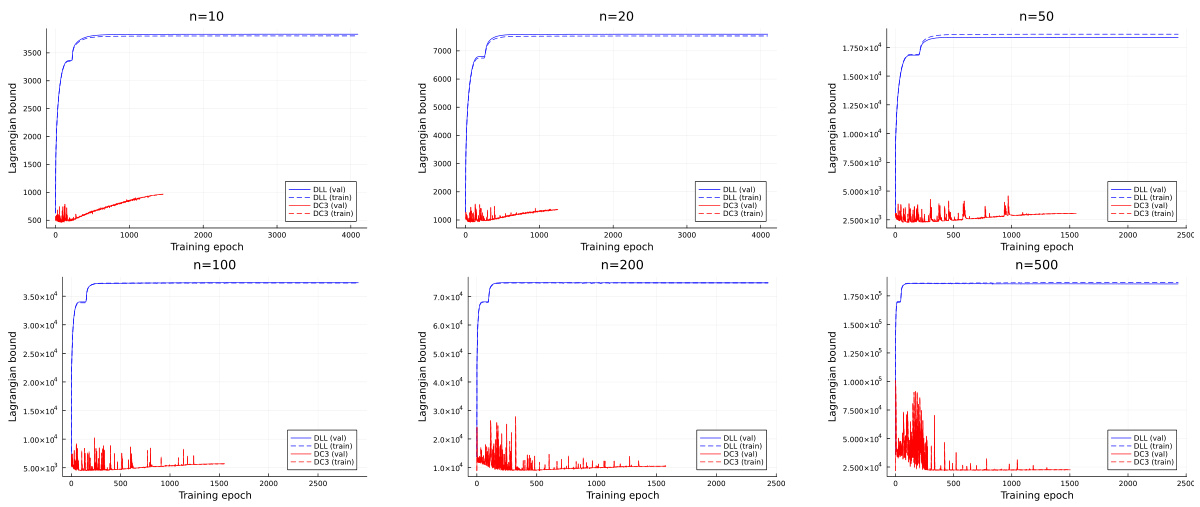

🔼 This figure shows the convergence plots of the average Lagrangian dual bound for both DLL and DC3 models on the training and validation sets. The plots illustrate the Lagrangian dual bound as a function of the number of training epochs for different problem sizes (n=10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500). It highlights the faster convergence speed of DLL compared to DC3, especially evident in larger problems.

read the caption

Figure 2: Production planning instances: convergence plots of average Lagrangian dual bound on training and validation sets for DLL and DC3 models, as a function of the number of training epochs.

More on tables

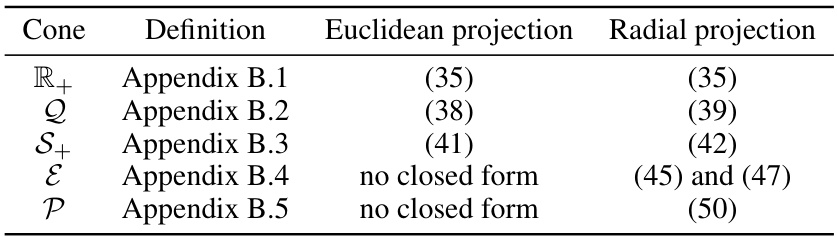

🔼 This table summarizes the Euclidean and radial projection methods for five standard cones used in conic optimization: the non-negative orthant (R+), the second-order cone (Q), the positive semi-definite cone (S+), the exponential cone (Ɛ), and the power cone (P). For each cone, it references the appendix section providing the detailed definition and the equation numbers in the paper that describe the Euclidean and radial projection formulas. Note that closed-form solutions are not available for the Euclidean projections of the exponential and power cones.

read the caption

Table 1: Overview of conic projections for standard cones

🔼 This table compares the performance of DC3 and DLL on linear programming instances in terms of optimality gap. For different problem sizes (m and n), it shows the average, standard deviation, and maximum optimality gap achieved by each method. Optimality gap is calculated as (L* − L(ŷ, 2))/L*, where L* is the optimal value obtained using Gurobi.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of optimality gaps on linear programming instances.

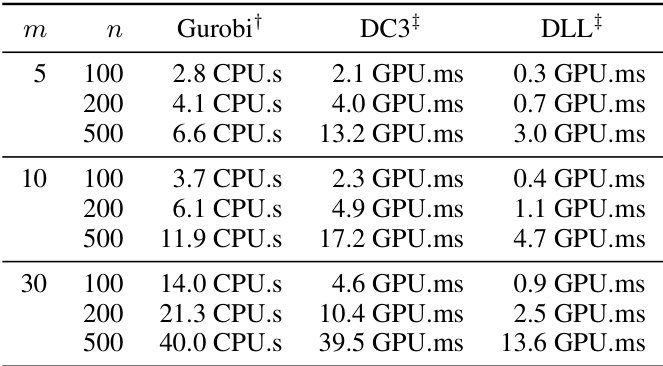

🔼 This table compares the computation time of three different methods: Gurobi (a commercial interior-point solver), DC3 (a state-of-the-art learning-based method), and DLL (the proposed method) for solving linear programming problems. The table shows the time taken to solve all instances in a test set for different problem sizes (m and n represent the number of resources and items respectively). It demonstrates that DLL significantly outperforms both Gurobi and DC3 in terms of speed, highlighting its efficiency. Note that the times for Gurobi are CPU times, while the times for DC3 and DLL are GPU times.

read the caption

Table 3: Computing time statistics for linear programming instances

🔼 This table compares the performance of DC3 and DLL on production planning instances in terms of optimality gap. For different problem sizes (n), it shows the average, standard deviation, and maximum optimality gap achieved by each method. The results demonstrate that DLL significantly outperforms DC3, achieving much smaller optimality gaps on average and across all instances.

read the caption

Table 4: Comparison of optimality gaps on production planning instances.

🔼 This table compares the computation times for solving linear programming instances using three different methods: Gurobi (a commercial interior-point solver), DC3 (a state-of-the-art learning-based method), and DLL (the proposed Dual Lagrangian Learning method). The table shows the time taken to solve all instances in the test set for different problem sizes (represented by the number of variables (n) and constraints (m)). Times are reported for CPU computation for Gurobi, and GPU computation for DC3 and DLL. The results demonstrate the significant speedup achieved by DLL compared to both Gurobi and DC3.

read the caption

Table 3: Computing time statistics for linear programming instances

Full paper#