TL;DR#

Molecular multi-task learning often faces data heterogeneity issues. Different molecular properties have datasets with varying accuracies and data sources, hindering model training and prediction. For example, accurate equilibrium structures are expensive to compute, leading to reliance on lower-accuracy data for larger datasets. This limits the performance of multi-task models. Existing multi-task learning methods are insufficient to overcome these limitations.

This paper introduces a novel approach to address this heterogeneity by using ‘physical consistency’ between molecular properties (e.g., energy and structure). The authors propose consistency training approaches. These ensure that predictions from different tasks align with known physical laws, enabling information exchange and accuracy improvements. The method successfully leverages more accurate energy data to improve structure prediction and integrates data from force and off-equilibrium structures, demonstrating the broad applicability of this approach to heterogeneous molecular data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to handling data heterogeneity in molecular multi-task learning, a significant challenge in the field. The proposed consistency training methods, which leverage physical laws to bridge information gaps between tasks, offer a powerful way to improve model accuracy and unlock the potential of diverse molecular datasets. This work opens up new avenues for research on integrating heterogeneous data and improving the accuracy of molecular property predictions, impacting various areas like materials science and drug discovery.

Visual Insights#

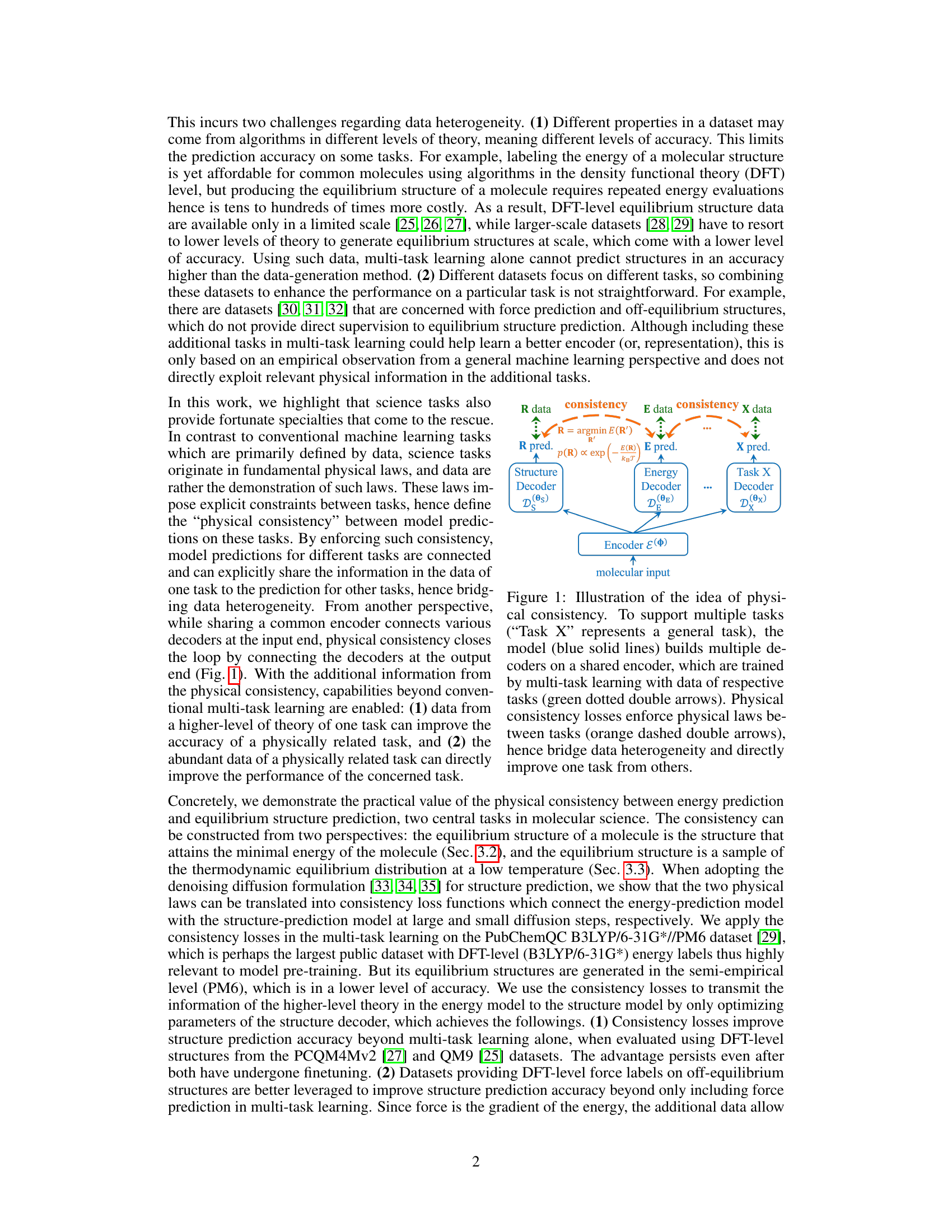

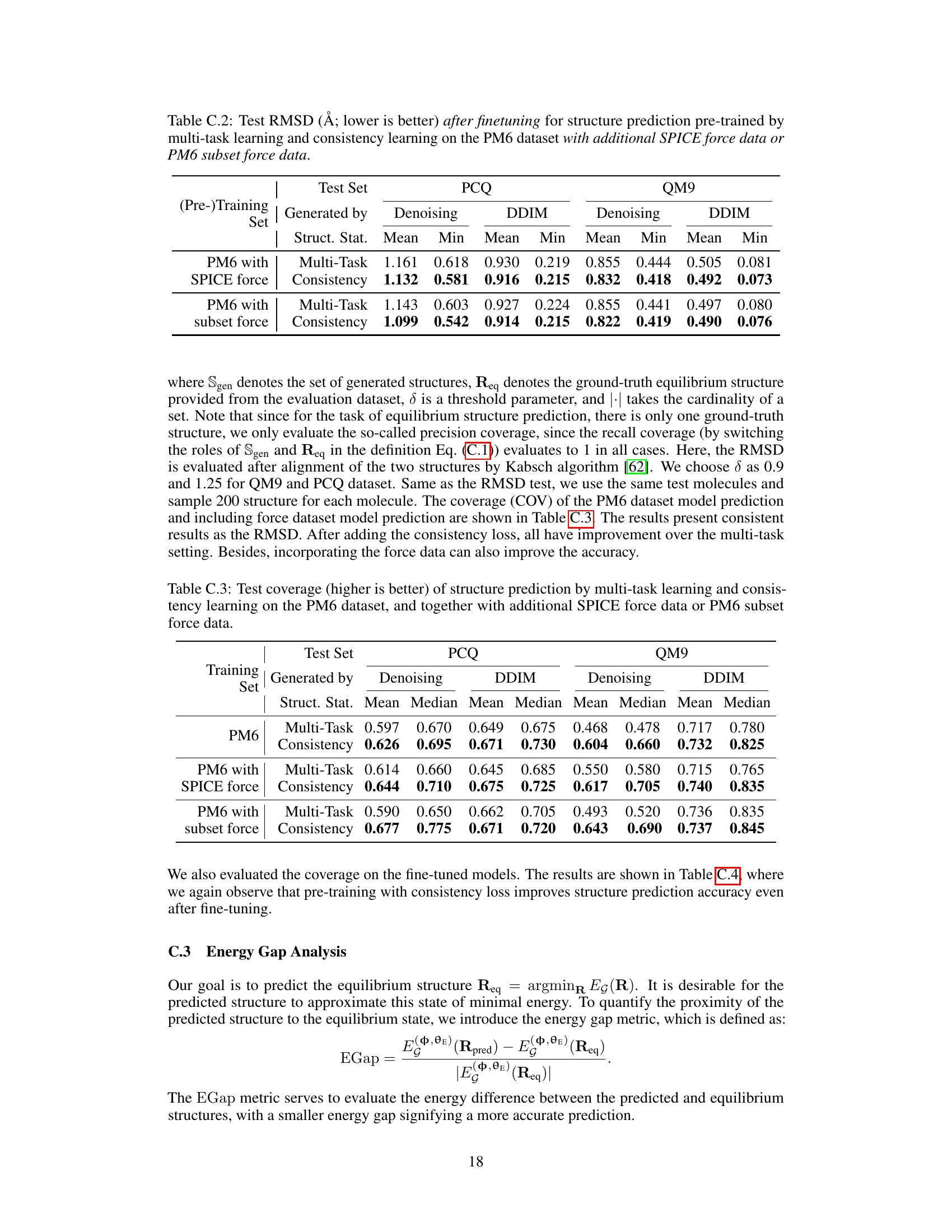

🔼 This figure illustrates the core idea of the paper: using physical consistency to bridge heterogeneous data in molecular multi-task learning. A shared encoder processes molecular input, feeding into multiple decoders (for different tasks like structure, energy, and a general task X). Multi-task learning connects these decoders at the input. Crucially, physical consistency losses are introduced, connecting the decoders at the output by explicitly enforcing physical relationships between predictions of different tasks. This allows information from one task (e.g., high-accuracy energy data) to directly improve the accuracy of another (e.g., structure prediction). The orange dashed arrows represent these consistency losses that enforce physical laws and bridge the data heterogeneity.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the idea of physical consistency. To support multiple tasks ('Task X' represents a general task), the model (blue solid lines) builds multiple decoders on a shared encoder, which are trained by multi-task learning with data of respective tasks (green dotted double arrows). Physical consistency losses enforce physical laws between tasks (orange dashed double arrows), hence bridge data heterogeneity and directly improve one task from others.

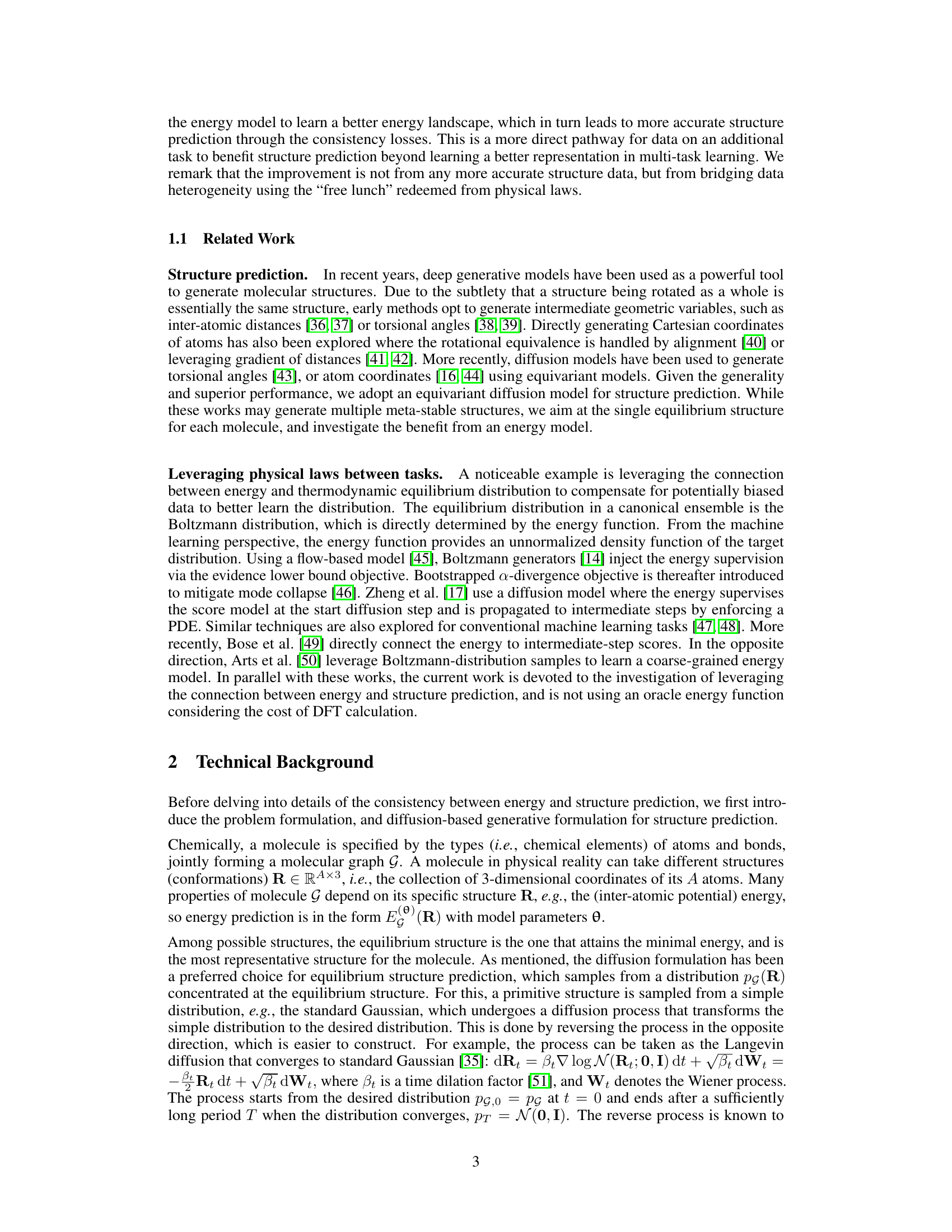

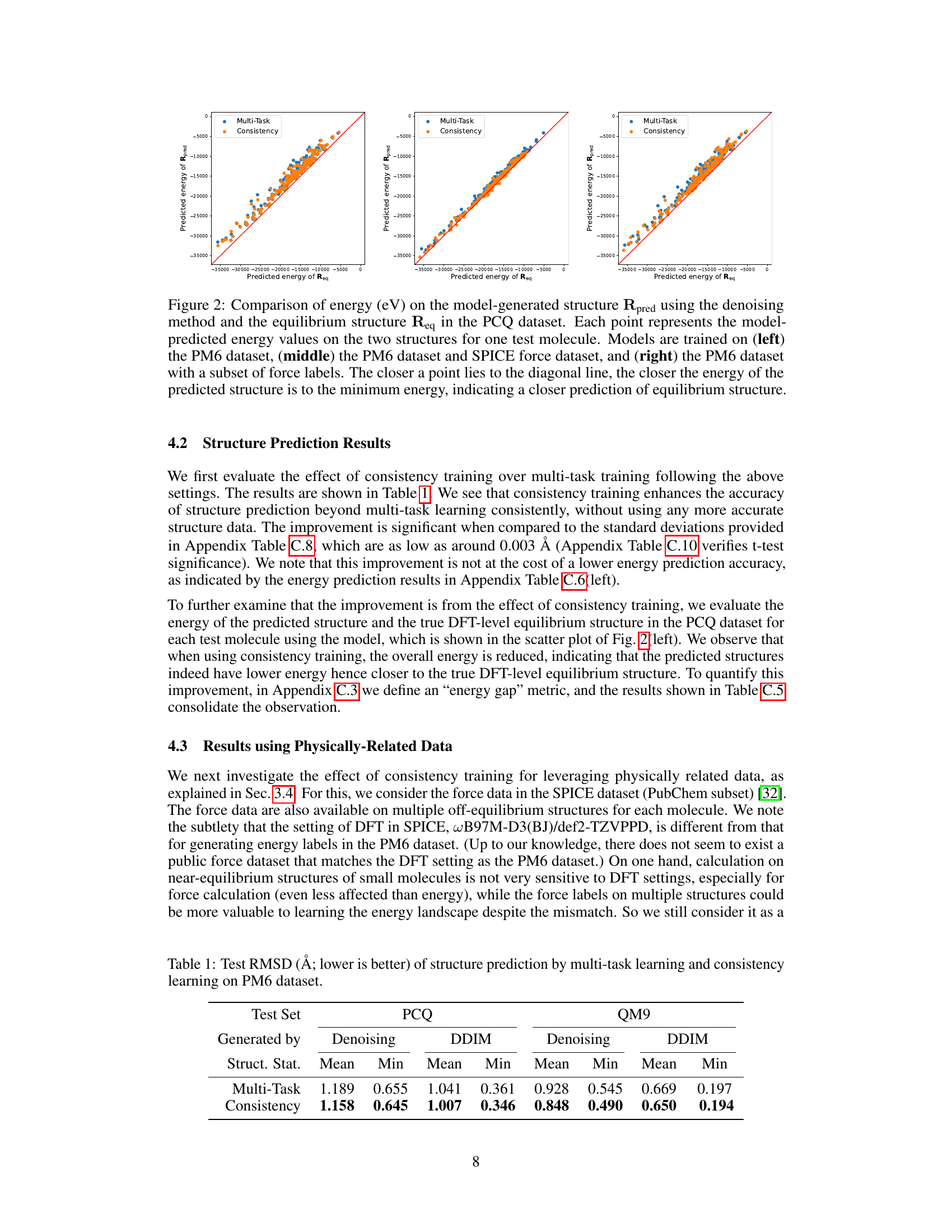

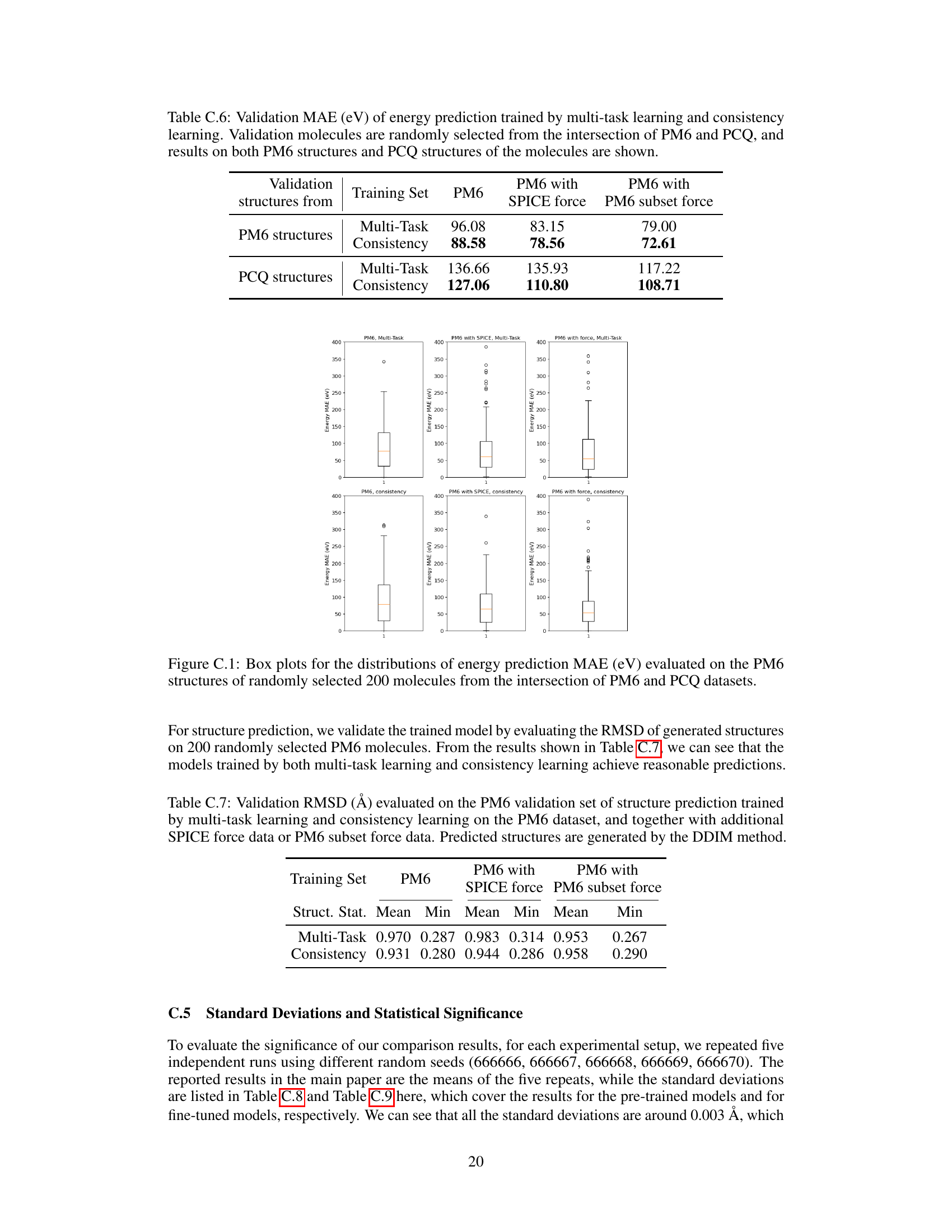

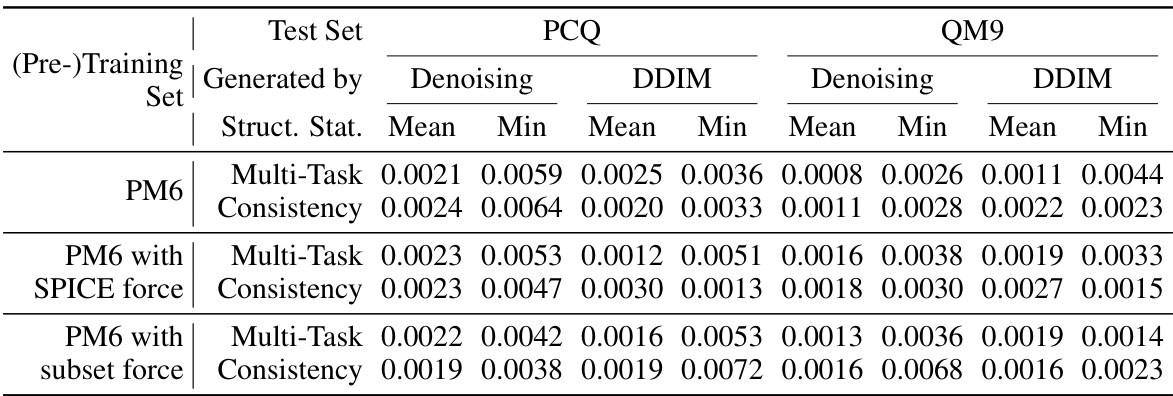

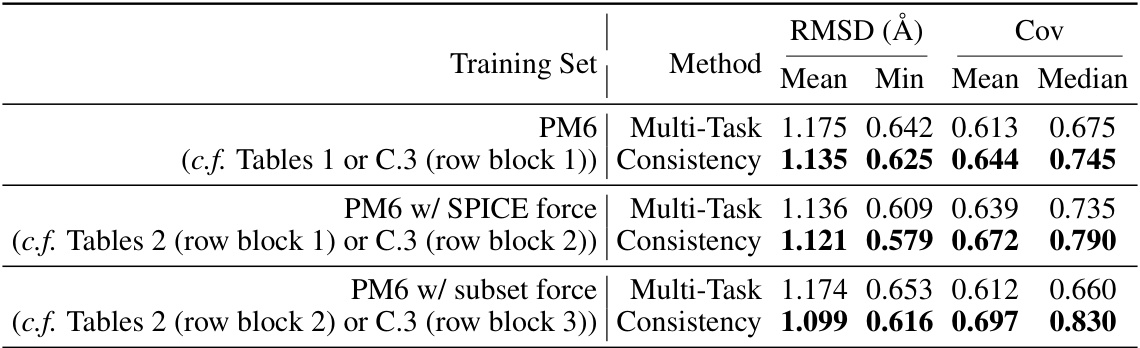

🔼 This table presents the results of structure prediction using two different methods: multi-task learning and consistency learning. The evaluation metric is the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) in Angstroms (Å), with lower values indicating better performance. The data is from the PM6 dataset. The table compares the mean and minimum RMSD values achieved by each method using two different structure generation approaches (Denoising and DDIM) and two different test datasets (PCQ and QM9).

read the caption

Table 1: Test RMSD (Å; lower is better) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on PM6 dataset.

In-depth insights#

Data Heterogeneity#

The concept of data heterogeneity is central to this research paper, focusing on the challenges posed by inconsistencies in molecular datasets used for multi-task learning. The authors highlight that different molecular properties (e.g., equilibrium structure, energy) often have data generated via methods with varying accuracy and computational cost. This leads to datasets where the quality and quantity of data vary significantly across tasks. Bridging this gap is crucial for effective multi-task learning, as using data of differing quality directly could hinder model accuracy. The authors propose a novel method to address these challenges by explicitly leveraging the physical relationships between different molecular properties. This approach allows information from more accurate data sources to improve the accuracy of predictions for less accurate ones, thus effectively mitigating the problem of data heterogeneity and significantly improving the performance of multi-task learning models.

Consistency Training#

The core idea behind consistency training in this context is to leverage the inherent physical relationships between different molecular properties to improve model accuracy and address data heterogeneity. Instead of treating each molecular property (e.g., energy, structure) as an independent task, the approach enforces consistency between model predictions for these related properties. This is achieved by designing loss functions that directly connect the outputs of different prediction models. For instance, the equilibrium structure is linked to the minimum energy, and the Boltzmann distribution provides a connection between structure and energy at various temperatures. These consistency losses effectively allow information exchange between tasks, improving the accuracy of predictions where data is limited or noisy, particularly in scenarios with data from different levels of theory. The method’s strength lies in its ability to bridge information gaps between tasks using physical laws, going beyond conventional multi-task learning approaches which rely solely on shared representations.

Physical Consistency#

The concept of ‘Physical Consistency’ in the context of molecular multi-task learning is a novel approach to bridge the gap between heterogeneous data originating from different levels of theory or focusing on different molecular properties. The core idea revolves around leveraging the inherent physical laws governing molecular behavior to explicitly connect and constrain predictions across various tasks. Instead of relying solely on shared representations in a multi-task learning framework, this method introduces consistency losses that directly enforce the relationships dictated by physics. This allows for information exchange between tasks, such as using high-accuracy energy data to improve lower-accuracy structure prediction, or integrating force data to enhance structure prediction models. Two consistency losses are introduced - one related to the optimality of equilibrium structures at minimum energy, and another related to the thermodynamic Boltzmann distribution of structures at a given temperature. These are applied to refine structure prediction models without altering the energy model, demonstrating a unique capability to effectively leverage the rich interdependencies of molecular properties and simulations. The method shows impressive results in enhancing the accuracy of structure prediction in molecular science by bridging data heterogeneity through physical laws.

Equilib. Structure Pred.#

The heading ‘Equilib. Structure Pred.’ likely refers to equilibrium structure prediction, a crucial task in computational chemistry and materials science. This section likely details methods for predicting the most stable 3D arrangement of atoms in a molecule. Accuracy is paramount, as the equilibrium structure dictates many properties. The paper likely discusses challenges, such as the high computational cost of obtaining accurate experimental data and the limitations of existing machine learning models for this task. Novel approaches to overcome these limitations, potentially involving multi-task learning with other properties (energy, force fields), or techniques like denoising diffusion models are probably introduced. Physical consistency between different molecular properties, such as the relationship between energy and structure, may be leveraged to improve predictions. The methods described might leverage relationships between energy (easily predicted) and equilibrium structure (costly to compute) to boost accuracy. Finally, evaluation metrics (like RMSD) and comparisons to state-of-the-art methods are expected to show significant improvement.

Future Work#

Future research could explore extending the consistency training framework to encompass additional molecular properties beyond energy and structure, such as dipole moments, polarizability, or other relevant descriptors. Integrating more diverse datasets, including those with varying levels of theoretical accuracy or different focuses (e.g., force fields, off-equilibrium structures), would further enhance the model’s robustness and predictive power. Investigating the impact of different consistency loss functions, potentially incorporating more sophisticated physical relationships, is warranted. Exploring alternative model architectures specifically designed to handle heterogeneous data and exploit physical constraints could lead to more efficient and accurate predictions. Finally, a thorough exploration of the computational cost-effectiveness of consistency training methods across various datasets is needed to optimize the training process and maximize the benefits of this approach. The broad applicability of consistency training across diverse scientific domains should also be investigated, evaluating its potential in problems where data heterogeneity presents significant challenges.

More visual insights#

More on figures

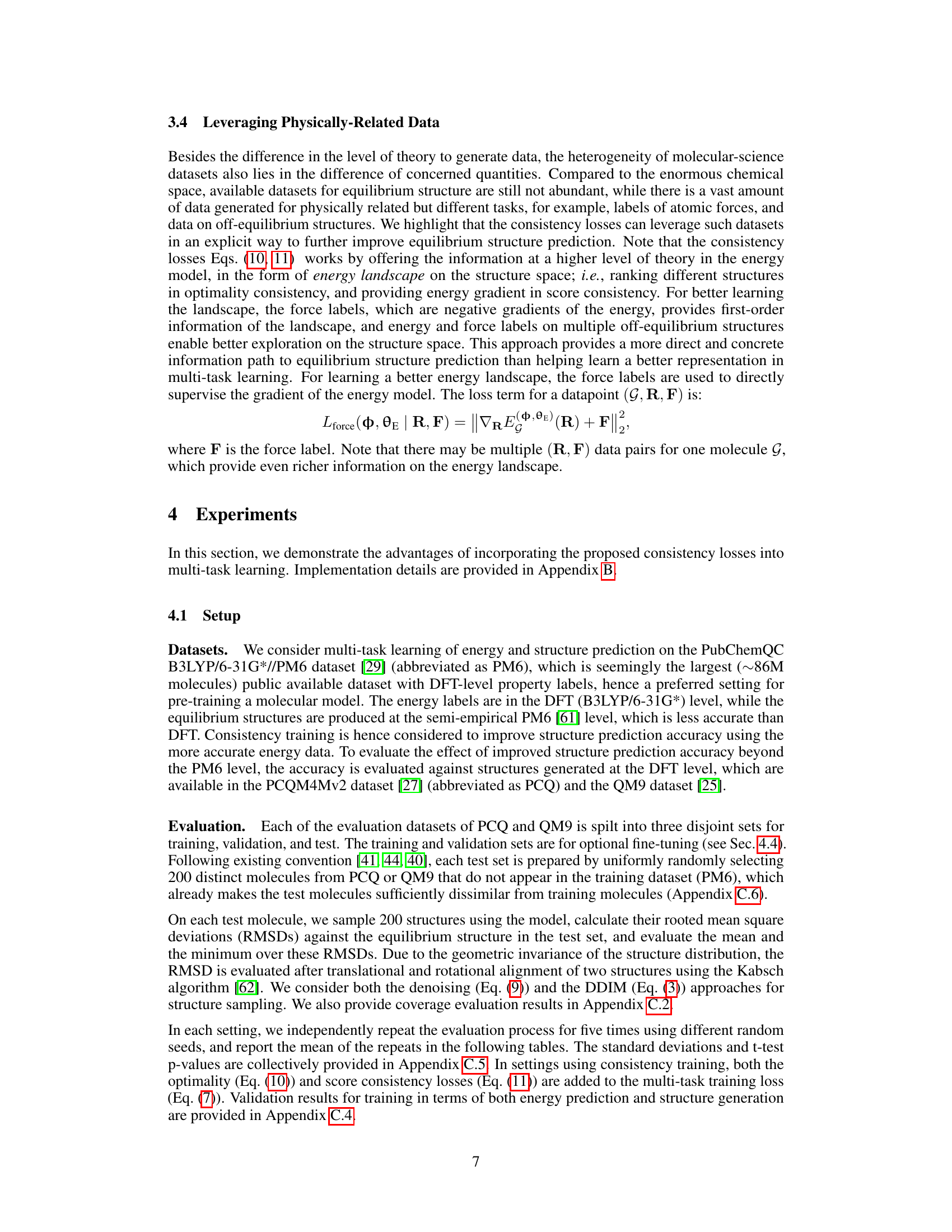

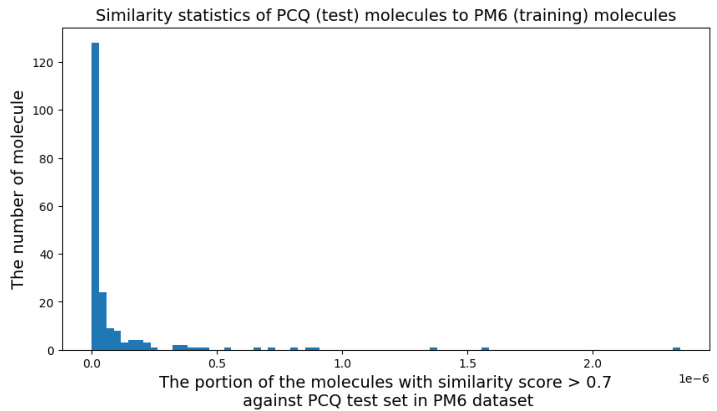

🔼 This figure compares the energy of the predicted equilibrium structure (Rpred) against the energy of the actual equilibrium structure (Req) for molecules in the PCQ dataset. Each point represents a molecule, with its x-coordinate showing the predicted energy of Req and its y-coordinate showing the predicted energy of Rpred. Three subplots show results from models trained under different conditions: (left) Only using PM6 dataset, (middle) using PM6 dataset and SPICE force dataset, and (right) using PM6 dataset and a subset of force labels. The closer the points are to the diagonal line, the better the model predicts the equilibrium structure.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of energy (eV) on the model-generated structure Rpred using the denoising method and the equilibrium structure Req in the PCQ dataset. Each point represents the model-predicted energy values on the two structures for one test molecule. Models are trained on (left) the PM6 dataset, (middle) the PM6 dataset and SPICE force dataset, and (right) the PM6 dataset with a subset of force labels. The closer a point lies to the diagonal line, the closer the energy of the predicted structure is to the minimum energy, indicating a closer prediction of equilibrium structure.

🔼 This figure compares the energy of model-generated equilibrium structures (Rpred) with the true equilibrium structures (Req) from the PCQ dataset. Each point represents a molecule, plotting its predicted energy against its true energy for both Rpred and Req. The plots illustrate the impact of different training data (PM6 only, PM6 + SPICE forces, PM6 + subset of force labels) on the accuracy of predicting equilibrium structures. Points closer to the diagonal indicate more accurate structure predictions, demonstrating how different training data affect the ability of the model to find the minimum energy structure.

read the caption

Figure 2: Comparison of energy (eV) on the model-generated structure Rpred using the denoising method and the equilibrium structure Req in the PCQ dataset. Each point represents the model-predicted energy values on the two structures for one test molecule. Models are trained on (left) the PM6 dataset, (middle) the PM6 dataset and SPICE force dataset, and (right) the PM6 dataset with a subset of force labels. The closer a point lies to the diagonal line, the closer the energy of the predicted structure is to the minimum energy, indicating a closer prediction of equilibrium structure.

🔼 The figure illustrates the concept of physical consistency in multi-task learning for molecular properties. A shared encoder processes molecular input, feeding into multiple decoders for different properties (e.g., energy, structure, Task X). Multi-task learning connects the decoders at the input, while physical consistency losses connect them at the output, enforcing relationships between predicted properties based on physical laws. This allows information exchange between tasks, improving prediction accuracy, particularly leveraging higher-accuracy data to improve less-accurate predictions.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the idea of physical consistency. To support multiple tasks ('Task X' represents a general task), the model (blue solid lines) builds multiple decoders on a shared encoder, which are trained by multi-task learning with data of respective tasks (green dotted double arrows). Physical consistency losses enforce physical laws between tasks (orange dashed double arrows), hence bridge data heterogeneity and directly improve one task from others.

More on tables

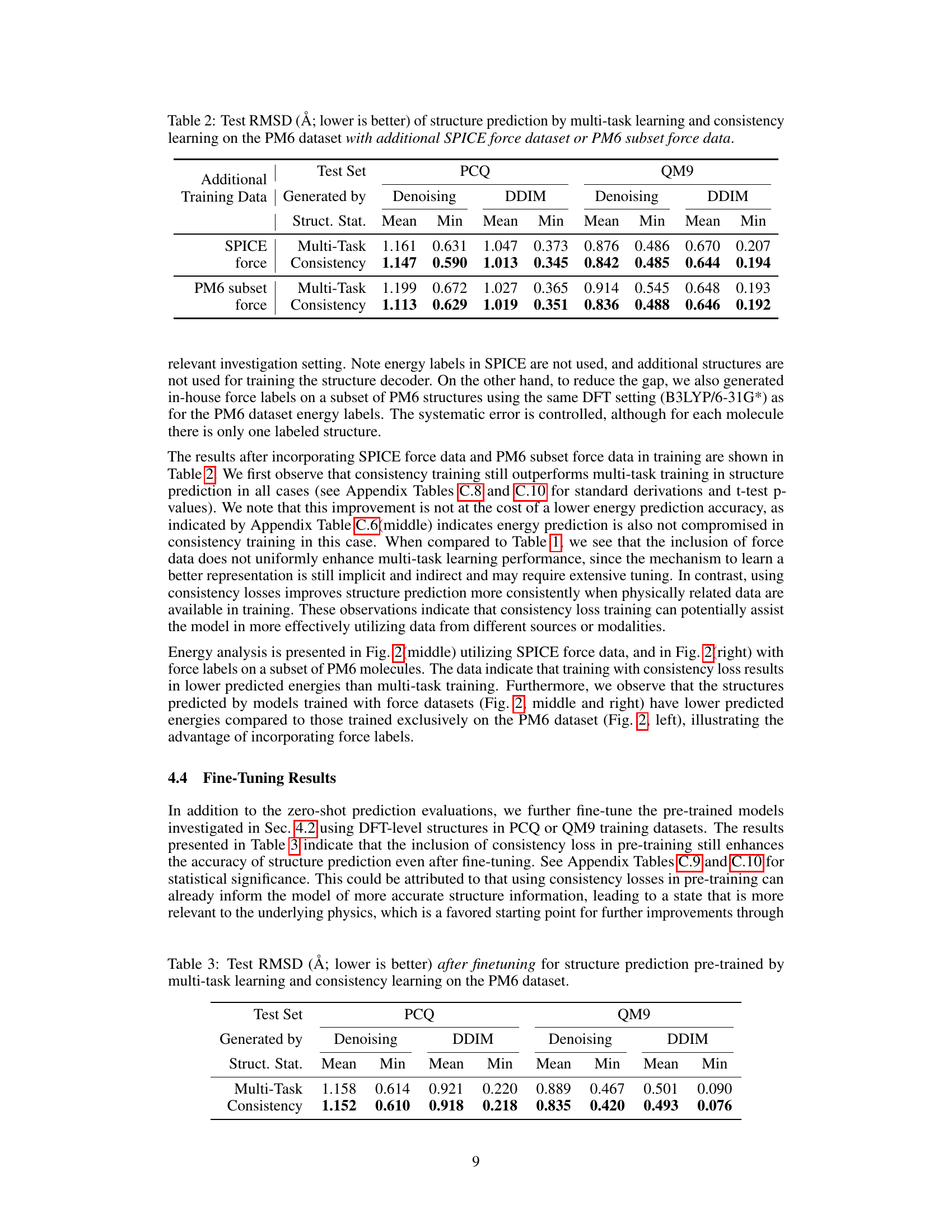

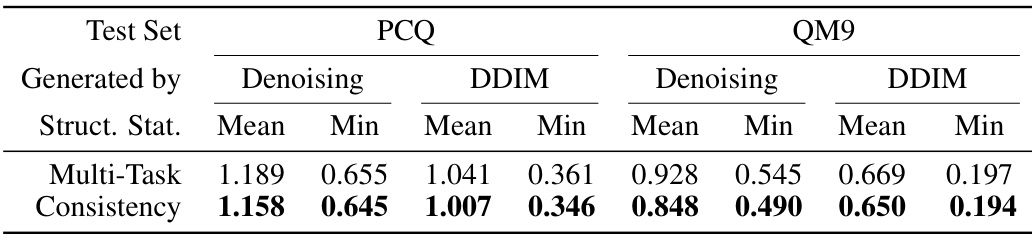

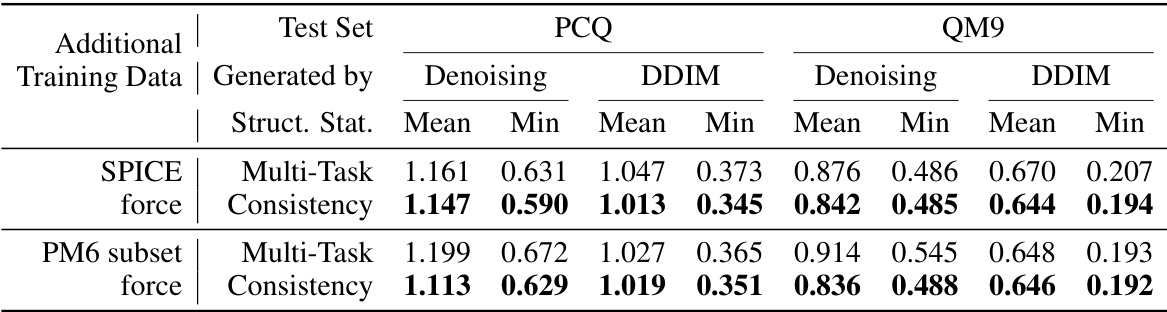

🔼 This table presents the results of structure prediction experiments using multi-task learning and consistency learning methods. The experiment is performed on the PM6 dataset augmented with either the complete SPICE force dataset or a subset of force data from the PM6 dataset. The table shows the mean and minimum Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) values for two different structure generation methods (Denoising and DDIM) on two different test sets (PCQ and QM9). Lower RMSD values indicate better prediction accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Test RMSD (Å; lower is better) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on the PM6 dataset with additional SPICE force dataset or PM6 subset force data.

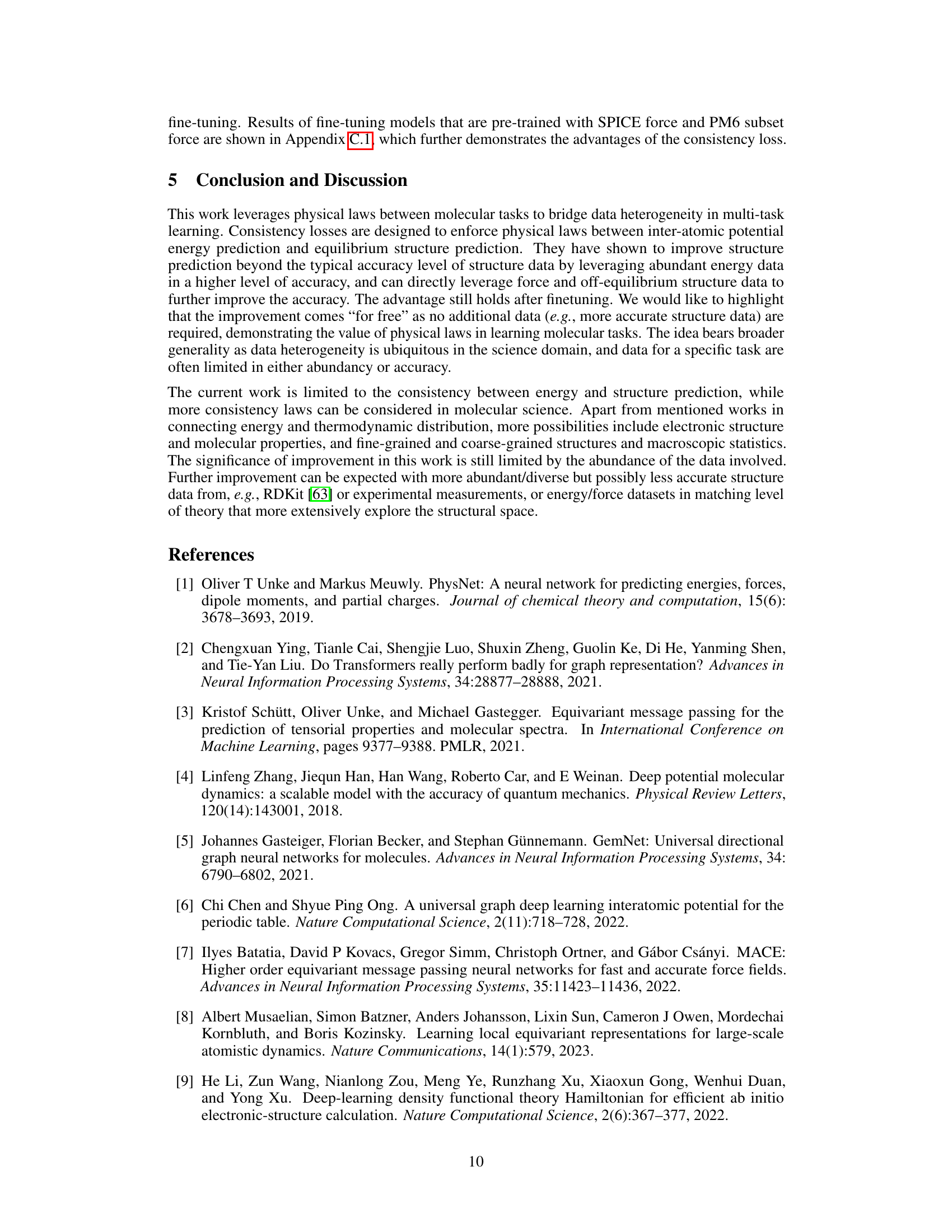

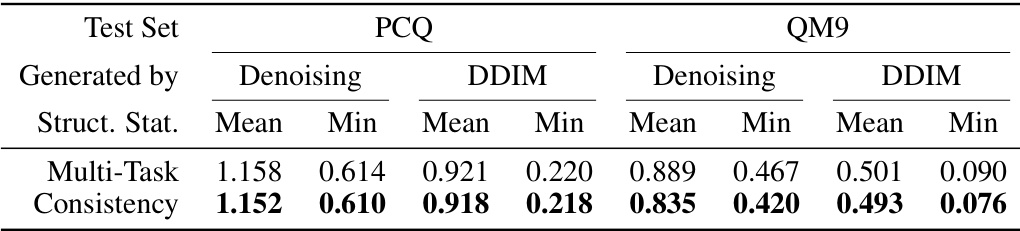

🔼 This table presents the results of the test Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) in Angstroms after fine-tuning the model. Lower RMSD values indicate better performance. The models were pre-trained using two different methods: multi-task learning and consistency learning, both on the PM6 dataset. The test RMSD is calculated using two different sampling methods: denoising and DDIM, for both PCQ and QM9 datasets.

read the caption

Table 3: Test RMSD (Å; lower is better) after finetuning for structure prediction pre-trained by multi-task learning and consistency learning on the PM6 dataset.

🔼 This table presents the results of structure prediction using two different methods: multi-task learning and consistency learning. The metric used is Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD), a measure of the difference between the predicted structure and the actual structure. Lower RMSD values indicate higher accuracy. The experiment was conducted on the PM6 dataset. The table shows the mean and minimum RMSD values achieved using both methods, with separate results for two different structure generation methods (Denoising and DDIM) and two different test datasets (PCQ and QM9).

read the caption

Table 1: Test RMSD (Å; lower is better) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on PM6 dataset.

🔼 This table presents the results of structure prediction using multi-task learning and consistency learning methods. It shows the mean and minimum Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) values for two different test sets (PCQ and QM9) when additional force data (either from the SPICE dataset or a subset of the PM6 dataset) are included in the training. Lower RMSD values indicate better prediction accuracy.

read the caption

Table 2: Test RMSD (Å; lower is better) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on the PM6 dataset with additional SPICE force dataset or PM6 subset force data.

🔼 This table shows the mean and minimum Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) in Angstroms for structure prediction on the PCQ and QM9 test sets. Two methods are compared: multi-task learning and consistency learning. Results are shown for both denoising and DDIM structure generation methods. Lower RMSD values indicate better performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Test RMSD (Å; lower is better) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on PM6 dataset.

🔼 This table presents the results of structure prediction experiments using two different methods: multi-task learning and consistency learning. The experiments were conducted on the PM6 dataset, and the performance is measured by the root mean square deviation (RMSD) in Angstroms. Lower RMSD values indicate better prediction accuracy. The table shows the mean and minimum RMSD values across different test sets generated by denoising and DDIM methods for both learning approaches. This allows for comparing the performance of multi-task learning against the performance of consistency learning in predicting molecular structures.

read the caption

Table 1: Test RMSD (Å; lower is better) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on PM6 dataset.

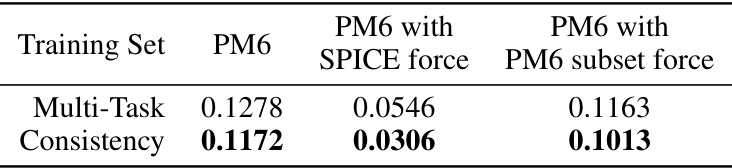

🔼 This table presents the energy gap (EGap) metric for structure predictions made using multi-task learning and consistency learning methods. The EGap metric quantifies the difference between the predicted structure’s energy and the equilibrium structure’s energy, providing insight into the accuracy of structure prediction. Lower EGap values indicate a more accurate prediction. The table shows results for different training scenarios, including training only on the PM6 dataset and training with additional force data (SPICE and PM6 subset).

read the caption

Table C.5: Comparison of averaged EGap between structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning. Lower EGap values suggest that the energy of the predicted structure is closer to the theoretical minimum energy.

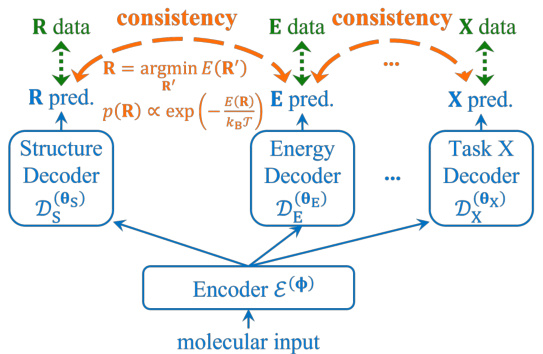

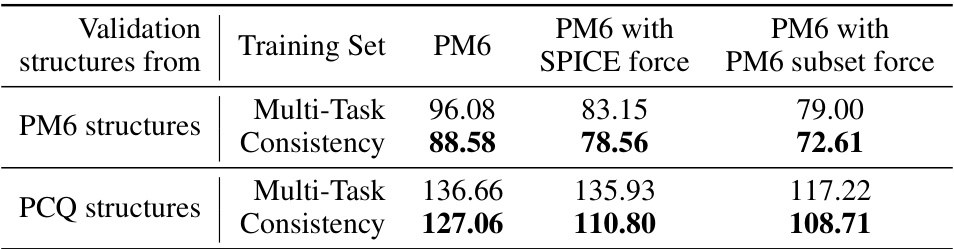

🔼 This table presents the mean absolute error (MAE) in eV for energy prediction on validation sets. The validation molecules are randomly selected from the intersection of the PM6 and PCQ datasets. The MAE is calculated for both PM6 and PCQ structures, allowing for a comparison of prediction accuracy when using structures from different theoretical levels. The table compares the performance of multi-task learning and consistency learning approaches.

read the caption

Table C.6: Validation MAE (eV) of energy prediction trained by multi-task learning and consistency learning. Validation molecules are randomly selected from the intersection of PM6 and PCQ, and results on both PM6 structures and PCQ structures of the molecules are shown.

🔼 This table presents the validation results for structure prediction using different training methods. The validation set is the PM6 dataset. The metrics used are Mean and Min RMSD, representing the average and best RMSD, respectively. The training methods include multi-task learning and consistency learning, with and without additional SPICE force data or a subset of PM6 force data. The structures were generated using the DDIM method.

read the caption

Table C.7: Validation RMSD (Å) evaluated on the PM6 validation set of structure prediction trained by multi-task learning and consistency learning on the PM6 dataset, and together with additional SPICE force data or PM6 subset force data. Predicted structures are generated by the DDIM method.

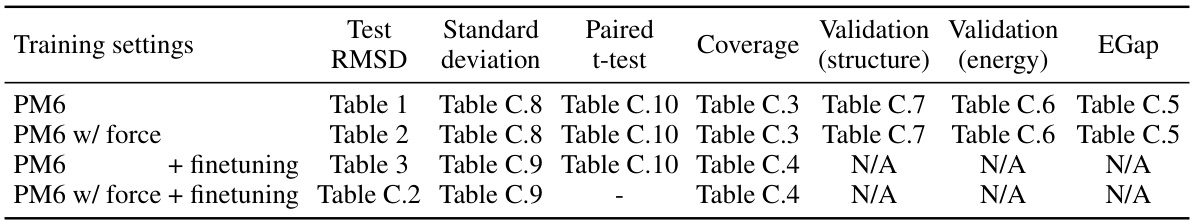

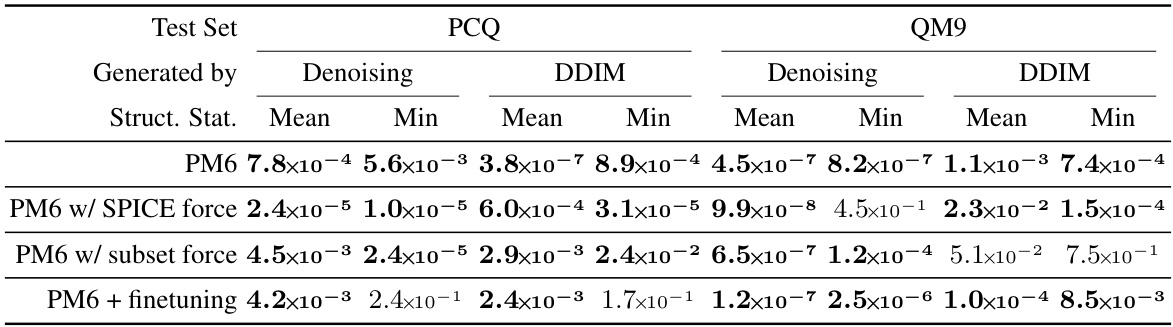

🔼 This table presents the standard deviations of the test RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) values obtained from five independent experiments using different random seeds. The results are categorized by training settings (PM6 only, PM6 with SPICE force data, PM6 with PM6 subset force data) and model type (Multi-Task learning, Consistency learning). The data for each category is further broken down by the method used for structure generation (Denoising, DDIM) and the evaluation dataset (PCQ, QM9). It provides a measure of the variability in the results and supports the statistical significance of the findings presented in Tables 1 and 2.

read the caption

Table C.8: Standard deviations for the test RMSD (Å) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on the PM6 dataset (corresponding to Table 1), and together with additional SPICE force data or PM6 subset force data (corresponding to Table 2).

🔼 This table presents the standard deviations of the test root mean square deviation (RMSD) in Angstroms for structure prediction experiments. The results are broken down by training methodology (multi-task learning vs. consistency learning), dataset (PCQ and QM9), and structure generation method (denoising and DDIM). Each training method includes results obtained using the PM6 dataset alone, the PM6 dataset with additional SPICE force data, and the PM6 dataset with a subset of force data. The table provides a detailed statistical breakdown of the results presented in Tables 1 and 2 of the main paper, allowing for a more nuanced understanding of the variability and significance of the findings.

read the caption

Table C.8: Standard deviations for the test RMSD (Å) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on the PM6 dataset (corresponding to Table 1), and together with additional SPICE force data or PM6 subset force data (corresponding to Table 2).

🔼 This table presents the results of paired t-tests performed to assess the statistical significance of the differences in structure prediction RMSD between multi-task learning and consistency learning. The p-values indicate the probability of observing the results under the null hypothesis that there is no difference between the two methods. Bold values indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05). Results are shown for different training scenarios: pre-training on the PM6 dataset alone, pre-training with additional force data, and pre-training followed by fine-tuning. The table helps determine if the improvements observed in the main paper are statistically meaningful.

read the caption

Table C.10: Paired t-test p-values on structure prediction RMSD means over 5 repeats (standard deviations are shown in Tables C.8 and C.9) corresponding to the results in Table 1 (row 1, pre-training on PM6), Table 2 (rows 2 and 3, pre-training on PM6 together with force labels), and Table 3 (row 4, pre-training on PM6 then finetuning). Values lower than the 0.05 significance threshold are shown in bold.

🔼 This table presents the results of structure prediction experiments using two different methods: multi-task learning and consistency learning. The experiments were conducted on the PM6 dataset, and the performance is evaluated based on the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) in Ångstroms, with lower values indicating better prediction accuracy. The table allows for comparison of the mean and minimum RMSD achieved by each method, highlighting the impact of the consistency learning approach.

read the caption

Table 1: Test RMSD (Å; lower is better) of structure prediction by multi-task learning and consistency learning on PM6 dataset.

Full paper#