TL;DR#

Model inversion (MI) attacks pose a serious threat to the privacy of deep learning models by reconstructing training data. Existing defenses often fall short due to their reliance on regularization, leaving them vulnerable to advanced attacks. This is a significant concern, especially in domains handling sensitive information like healthcare and finance.

To tackle this challenge, the researchers propose Trap-MID, a novel defense mechanism that cleverly uses ’trapdoors’ to deceive MI attacks. A trapdoor is a hidden feature engineered into the model, which produces a specific output when a certain input ’trigger’ is present. During an MI attack, the adversary will mainly focus on the trapdoor triggers, essentially extracting less actual private information. Trap-MID demonstrates effectiveness against a range of state-of-the-art MI attacks, surpassing existing defenses in performance while maintaining high model utility. The approach is computationally efficient and requires no additional data.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers working on the privacy and security of deep learning models. It introduces a novel defense mechanism against model inversion attacks, a significant threat to sensitive data used in training. The proposed method, Trap-MID, offers a computationally efficient and data-efficient solution without the need for additional data or complex training procedures. This makes it highly relevant to current research trends focusing on privacy-preserving AI, and opens new avenues for developing more robust and effective defenses against evolving attack techniques. Its data-efficient and computationally-light nature also expands the applicability to resource-constrained environments.

Visual Insights#

🔼 The figure illustrates the core idea of Trap-MID and its training process. (a) shows that Trap-MID introduces a trapdoor into the model, creating a shortcut for model inversion attacks. This trapdoor information misleads the attacks towards the trapdoor information rather than the private data, protecting the privacy of the private data distribution. (b) provides a detailed description of the Trap-MID training pipeline, illustrating how the trapdoor is integrated into the model, including the classification loss, trapdoor loss, and discriminator loss.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the intuition behind Trap-MID and our training pipeline.

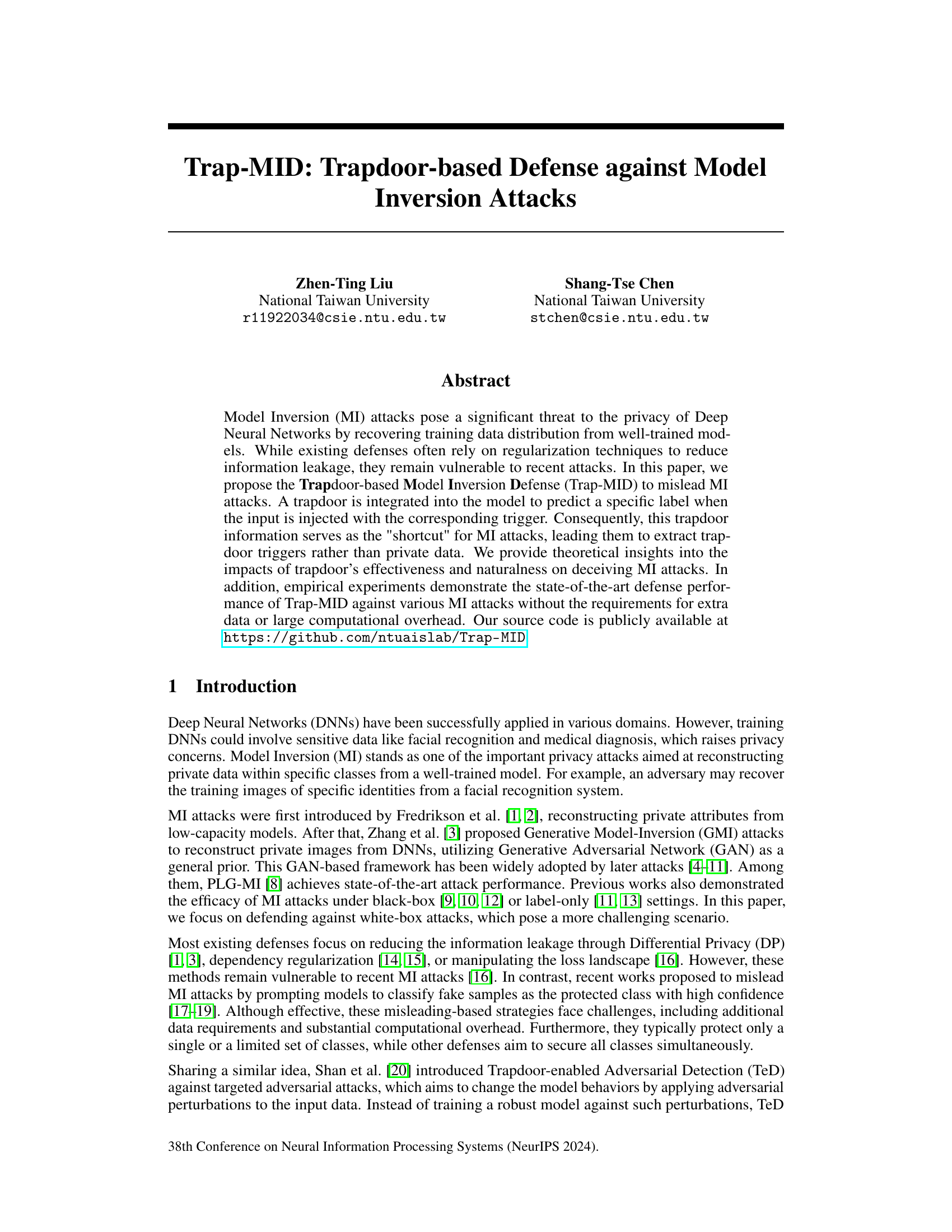

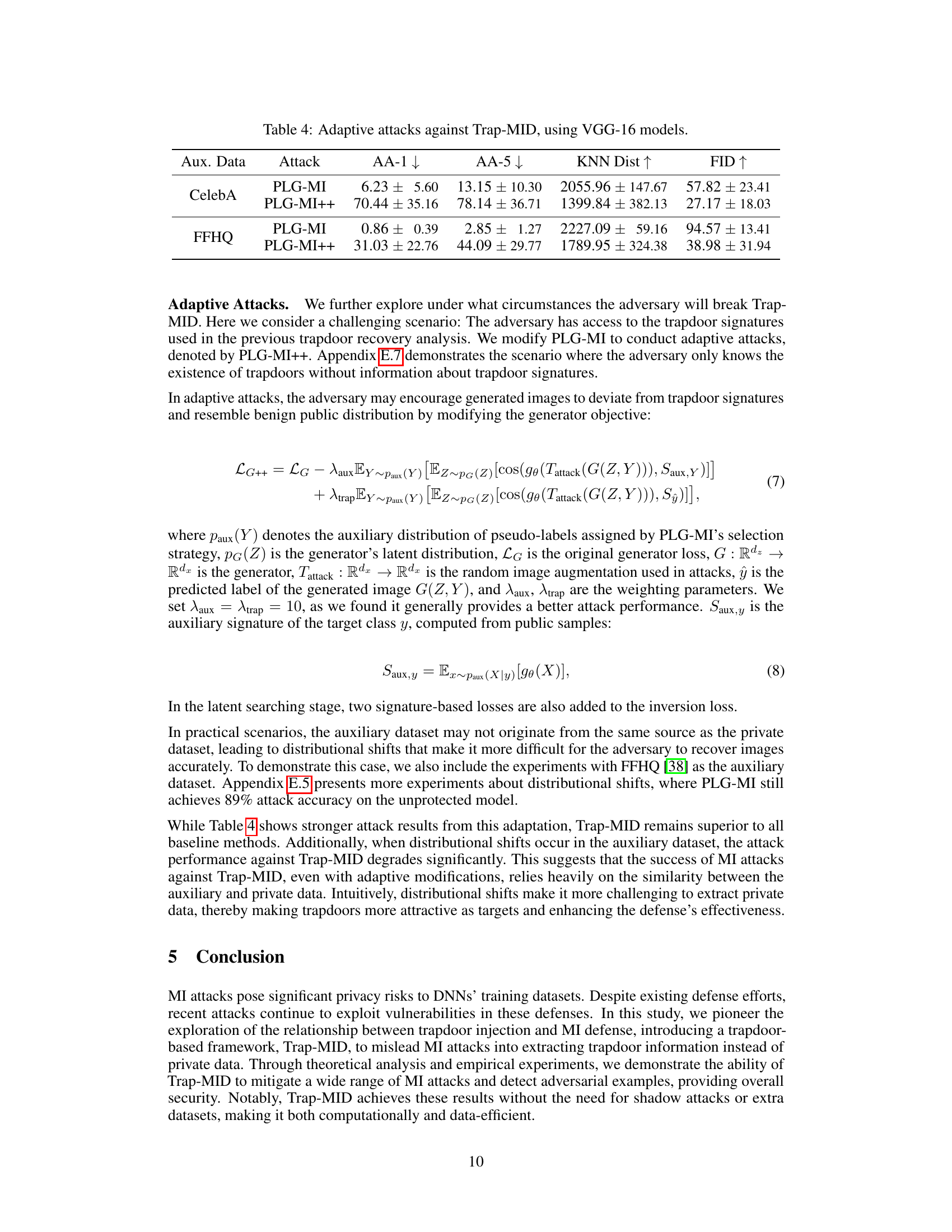

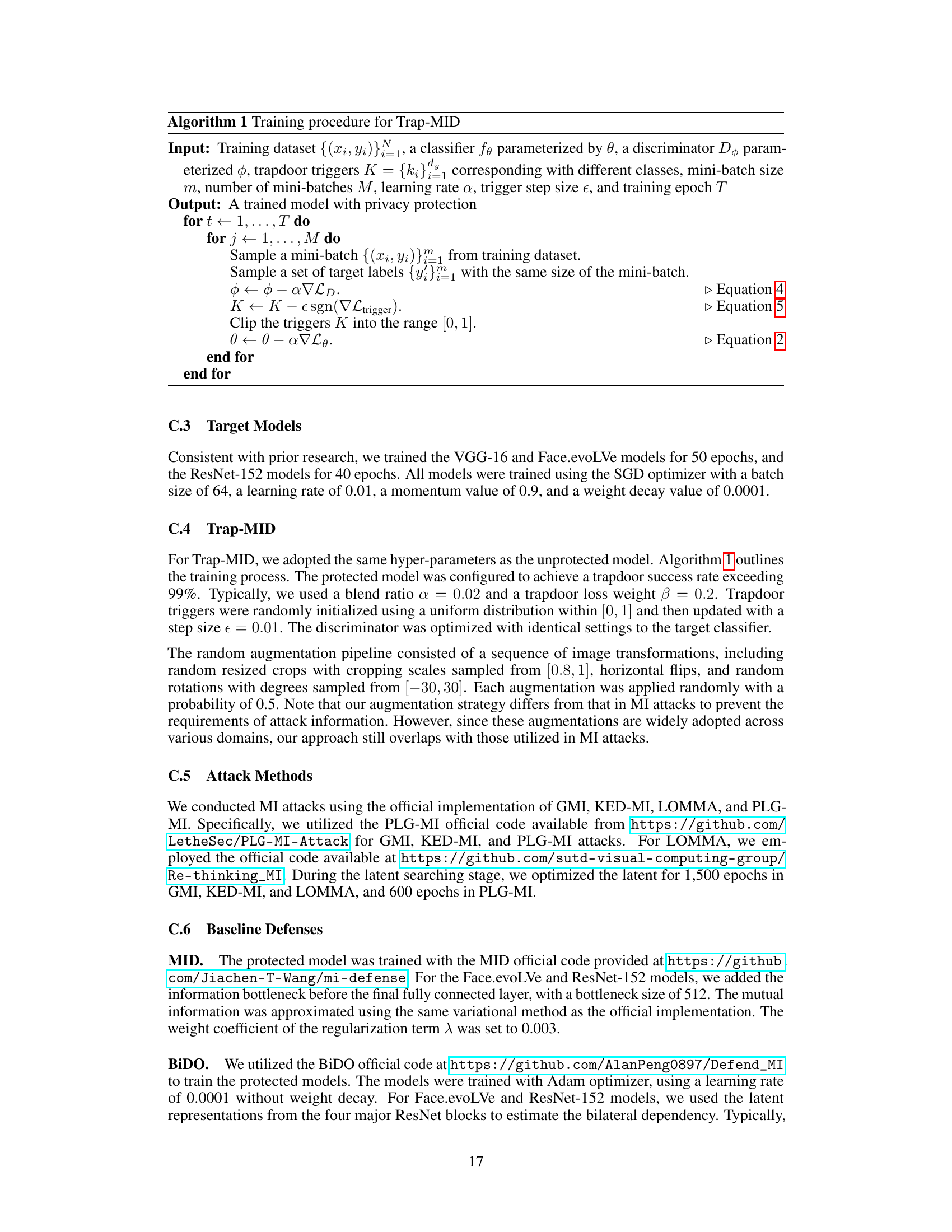

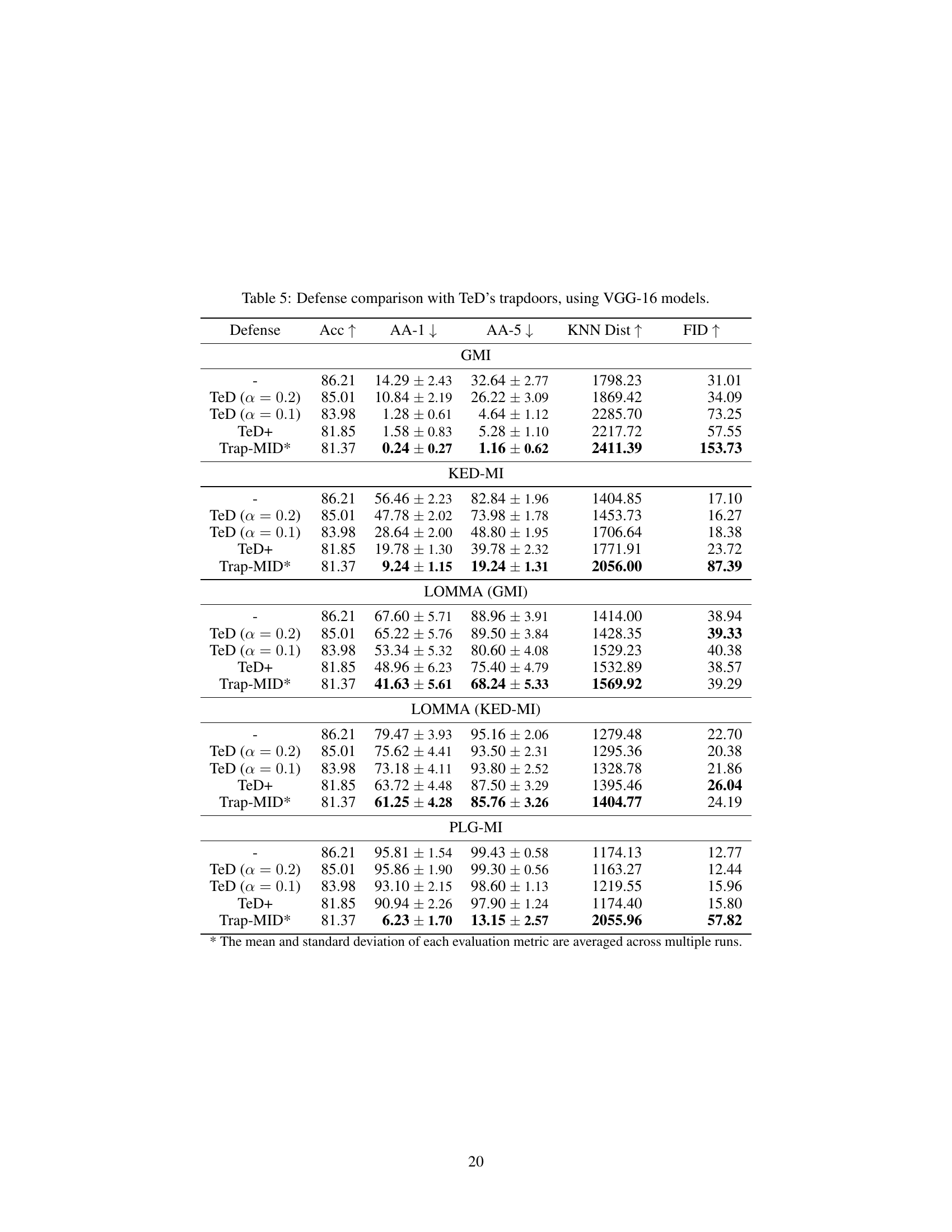

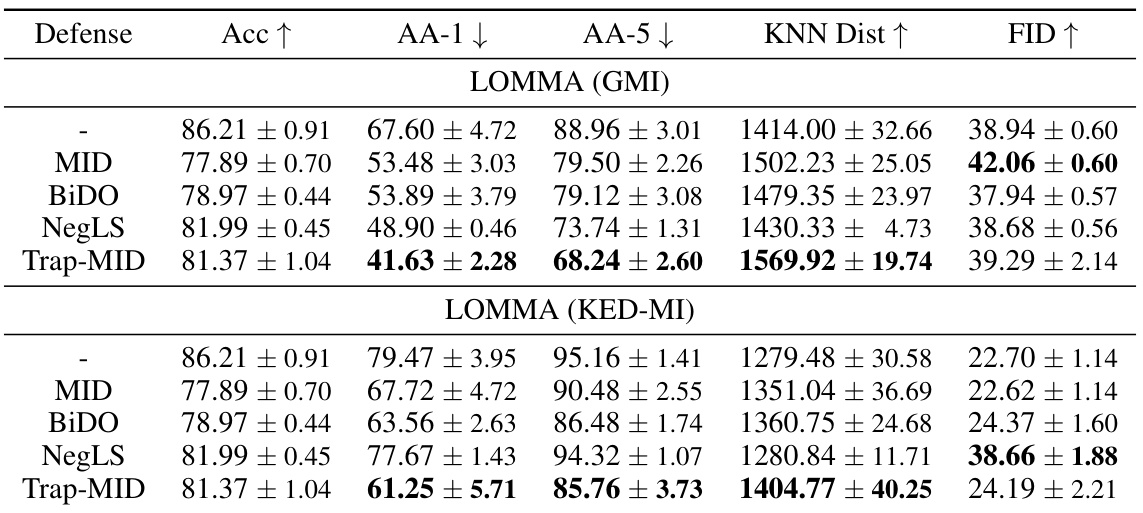

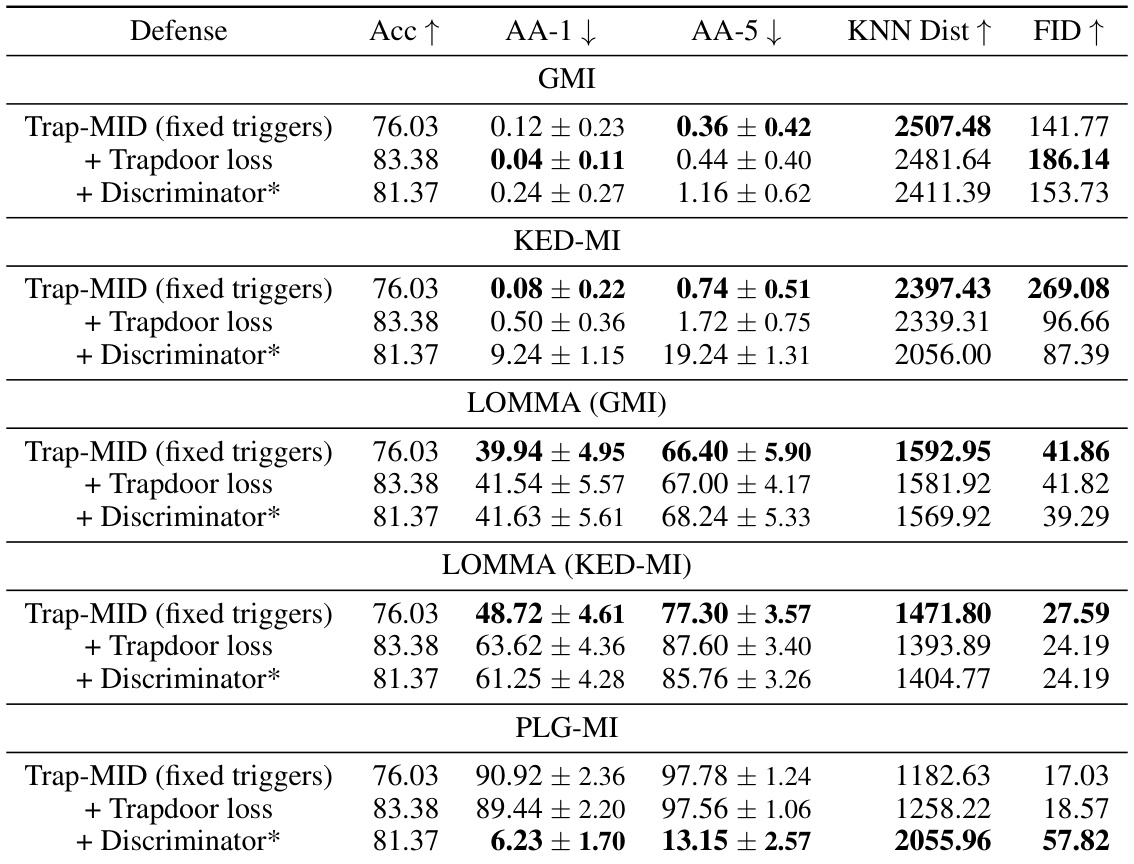

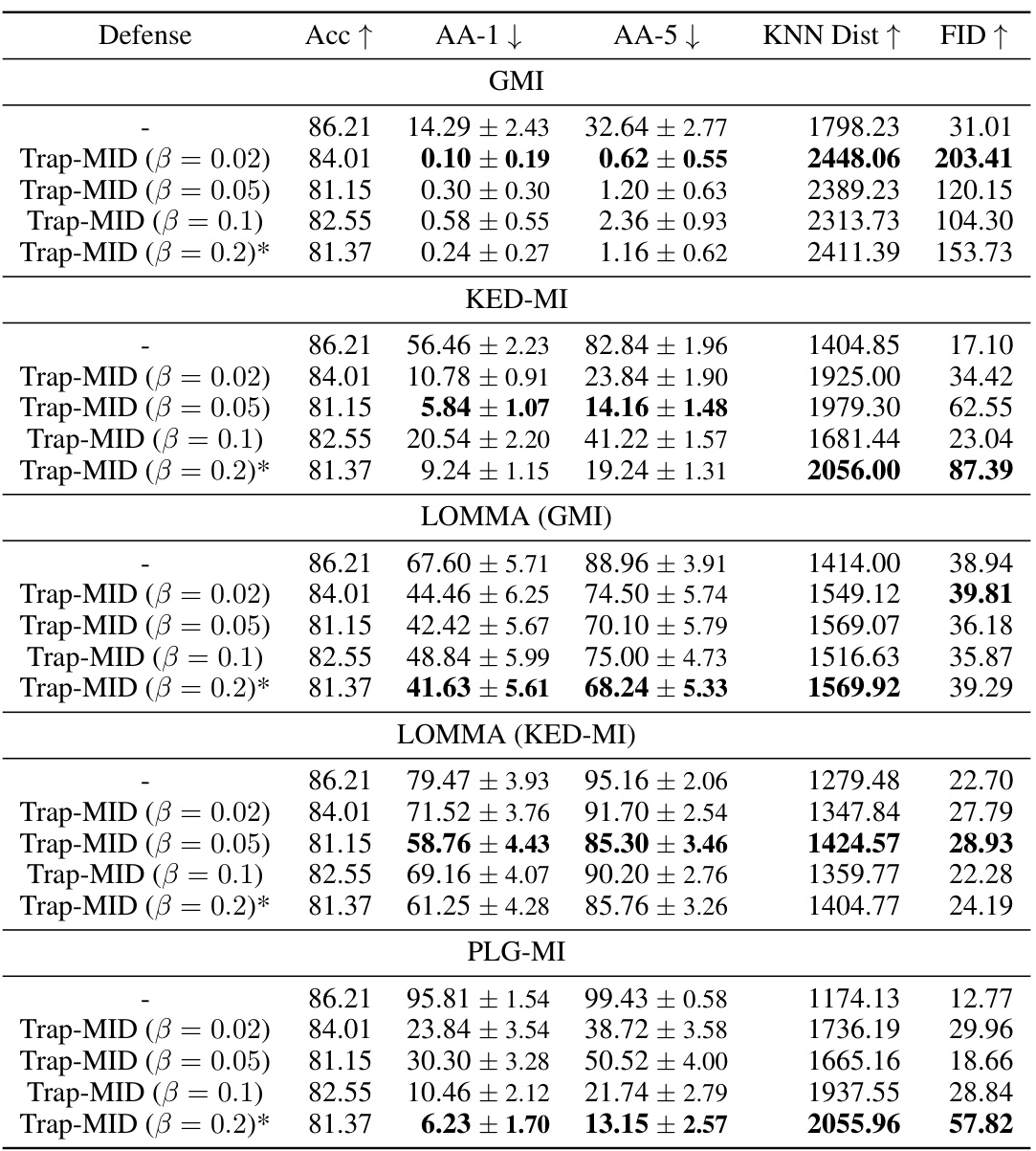

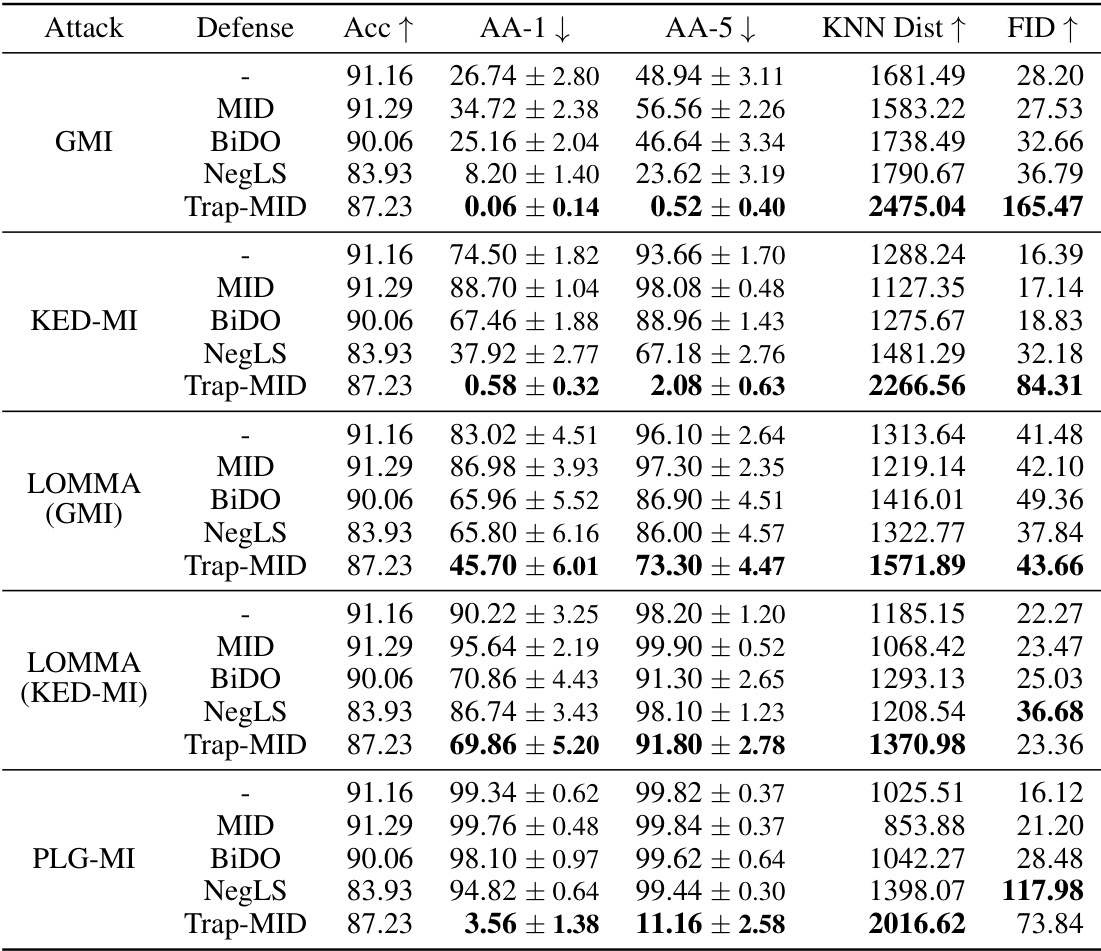

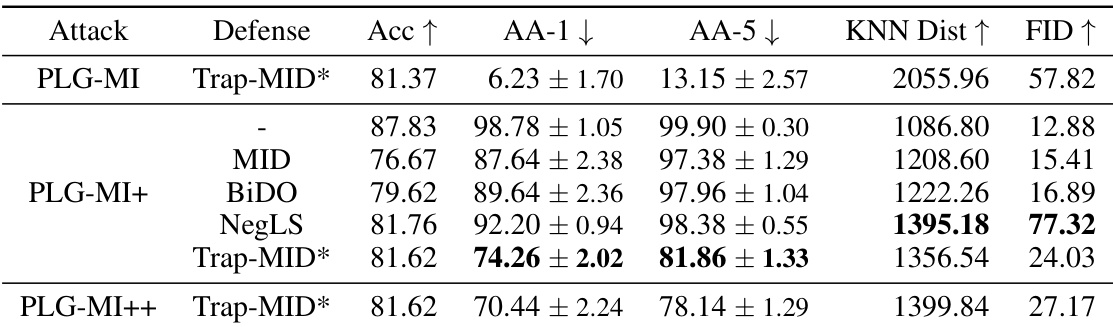

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different defense mechanisms against three different model inversion (MI) attacks: Generative Model Inversion (GMI), Knowledge-Enhanced Distributional Model Inversion (KED-MI), and Pseudo Label-guided Model Inversion (PLG-MI). The defenses compared include MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID. The table shows the attack accuracy (AA), K-Nearest Neighbor Distance (KNN Dist), and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) for each defense method against each attack. Higher values for KNN Dist and FID indicate better defense performance. Lower values for AA indicate better defense performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

In-depth insights#

Trapdoor Defense#

Trapdoor defense mechanisms, as explored in the provided research, represent a novel approach to mitigating model inversion (MI) attacks. The core idea is to introduce ’trapdoors’ into the model, intentionally creating vulnerabilities that mislead MI attacks. These trapdoors act as shortcuts, guiding the attacker to recover the easily accessible trapdoor information instead of the sensitive training data. The effectiveness of this technique hinges on two crucial properties of the trapdoors: their effectiveness in triggering the desired response and their naturalness, which helps in blending seamlessly into the model’s behavior, and avoiding detection. Theoretical analysis supports this approach by demonstrating the impact of trapdoor effectiveness and naturalness on the success of MI attacks. Experimental results showcase the superiority of trapdoor-based defense compared to existing methods by achieving state-of-the-art performance, without substantial computational overhead or the need for additional data. However, limitations exist, such as sensitivity to hyperparameter tuning and the potential for adaptive adversaries to circumvent the defense, suggesting that more research is warranted to strengthen this promising new defense strategy.

MI Attack Deception#

Model inversion (MI) attacks reconstruct training data from deep learning models, posing a significant privacy risk. A core strategy to defend against MI attacks is deception, diverting the attacker’s reconstruction efforts away from sensitive data. This involves misleading the attacker into recovering less informative or irrelevant information. Trapdoors, strategically integrated into the model, are a promising deception technique. They create a ‘shortcut’ for the MI process, leading the attack to reconstruct trigger-related features instead of private data. The effectiveness of a trapdoor depends on its naturalness (how seamlessly it integrates) and effectiveness (how reliably it triggers the desired response). These factors are crucial for making the injected trapdoor credible and difficult to detect. Careful design and integration are therefore vital to deceive the attack, while maintaining model utility.

Theoretical Insights#

A dedicated ‘Theoretical Insights’ section would delve into the fundamental mechanisms of Trap-MID. It would formally define key concepts like trapdoor effectiveness (quantifying how well the trapdoor misleads attacks) and trapdoor naturalness (measuring how realistically the triggered samples resemble benign data). The analysis would likely involve establishing a mathematical relationship between these properties and the success rate of the model inversion attacks. Information-theoretic bounds might be derived, offering a guarantee on the model’s privacy under specific conditions. Additionally, the section might explore the impact of different trigger injection techniques, analyzing how variations in methods affect both effectiveness and naturalness, offering guidelines for optimal trapdoor design. Finally, it could discuss potential limitations of the theoretical model, such as assumptions regarding the attacker’s capabilities or data distribution, and suggest directions for future research.

Empirical Results#

An Empirical Results section in a research paper would present quantitative findings to support the study’s claims. It should begin with a clear description of the experimental setup, including datasets, models, evaluation metrics, and attack methods used. Detailed tables and figures would present key performance indicators (KPIs), such as attack accuracy and FID scores, comparing the proposed defense (e.g., Trap-MID) against existing defenses and various attacks. The discussion should highlight statistically significant differences between the proposed and existing methods, analyzing trends and patterns in the results. Crucially, the results should be carefully interpreted, acknowledging any limitations or unexpected outcomes. The section should focus on providing a balanced and objective presentation of the empirical evidence, clearly stating the strengths and weaknesses of the proposed approach compared to the state-of-the-art. Visualizations, such as reconstructed images from model inversion attacks, are important for qualitative analysis and demonstrating the effectiveness of the defense. Finally, the section should conclude with a summary of the key empirical findings, reinforcing the main contributions of the research paper.

Future Works#

The authors suggest several avenues for future research, primarily focusing on enhancing Trap-MID’s robustness and expanding its applicability. Improving the efficiency of the trapdoor generation process is crucial, potentially through more efficient trigger design or optimization techniques, to reduce computational overhead and make the approach more suitable for large-scale applications. Addressing the limitations of current trigger designs, such as their vulnerability to transformations, is another important area to explore. Further investigation into how Trap-MID interacts with other defense mechanisms, such as those employing differential privacy or generative adversarial networks, could lead to more effective and robust defense strategies. Finally, extending Trap-MID to other domains and data modalities beyond image recognition represents a significant opportunity. The theoretical connection established between trapdoor injection and MI attacks opens promising avenues for developing similarly effective defenses for different forms of sensitive data, such as text or graph data.

More visual insights#

More on figures

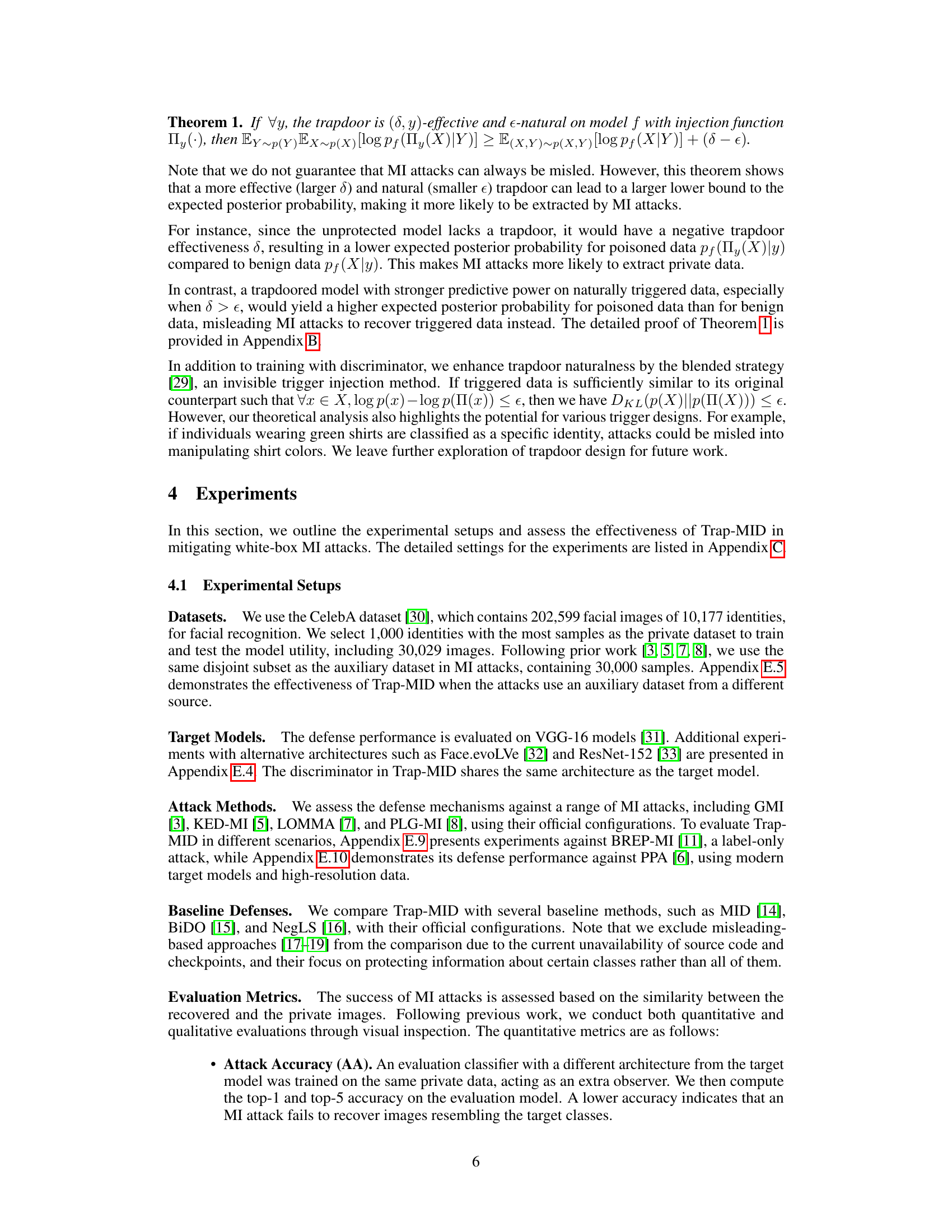

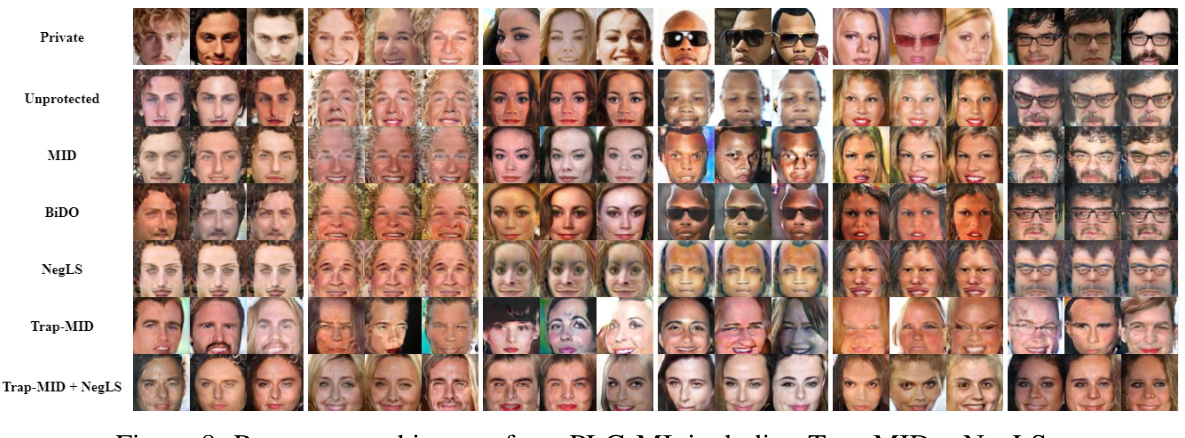

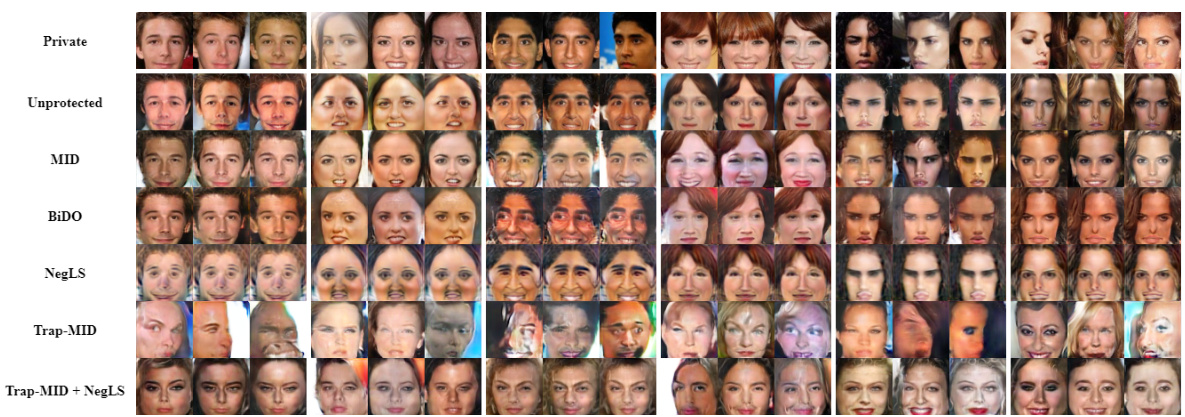

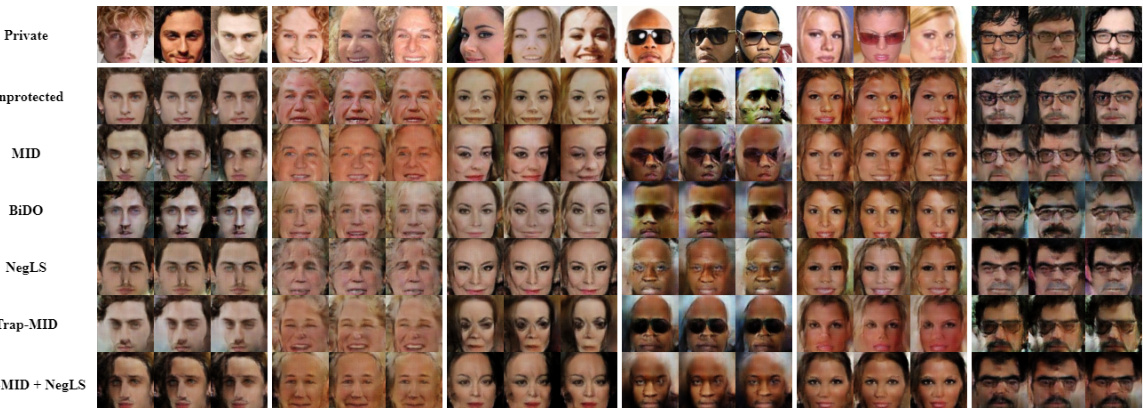

🔼 This figure shows the reconstructed images generated by the state-of-the-art model inversion attack, PLG-MI, against different defense methods. The first row displays the original private images from the training dataset. The subsequent rows illustrate the reconstructed images produced by the unprotected model and different defense methods, including MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID. By visually comparing the reconstructed images with the original private images, one can assess the effectiveness of each defense method in protecting the privacy of the training data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Reconstructed images from PLG-MI.

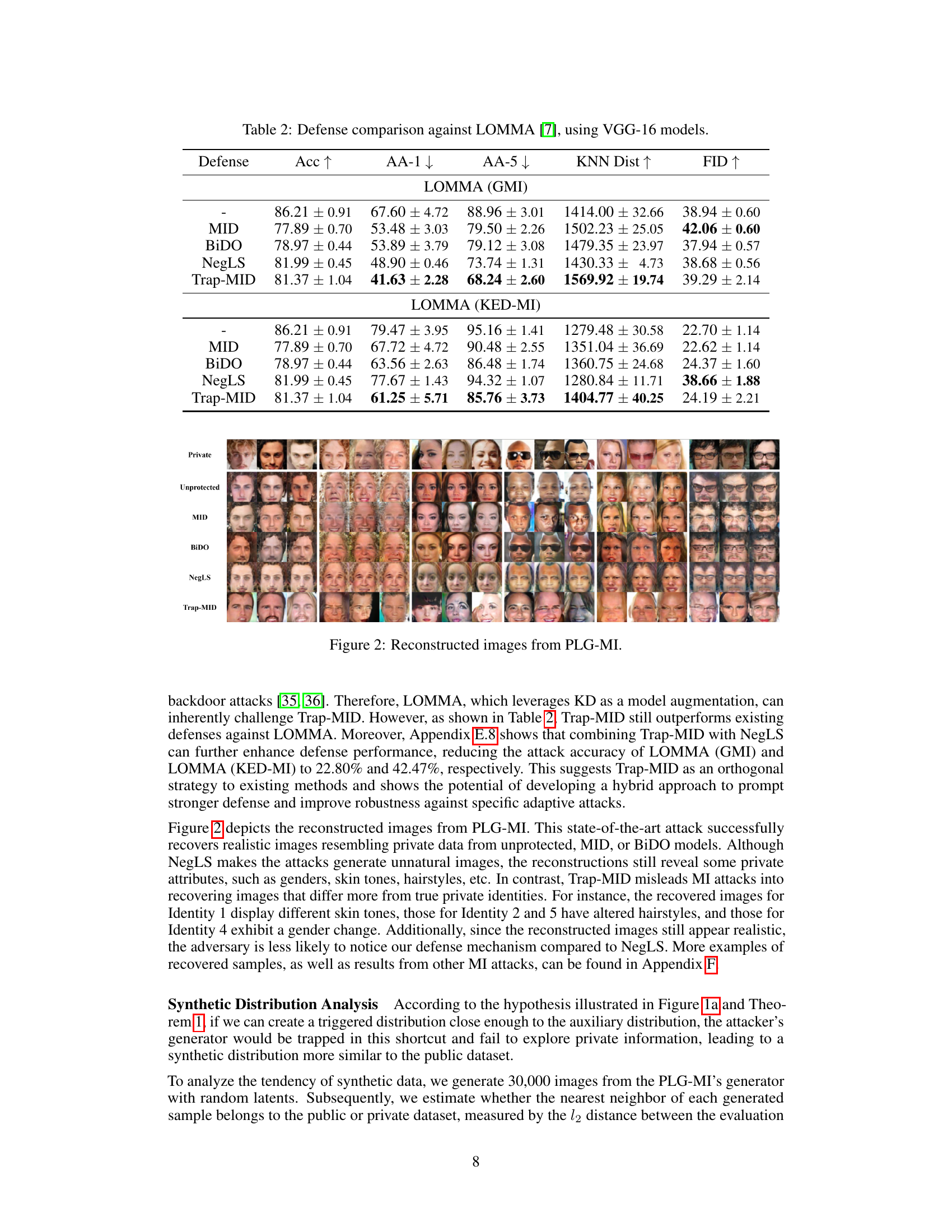

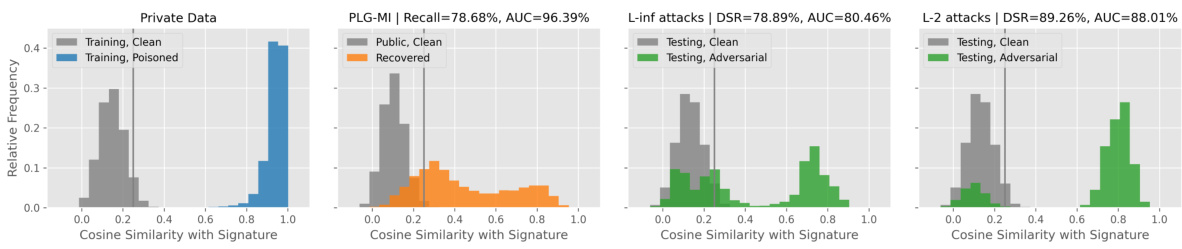

🔼 This figure visualizes the effectiveness of Trap-MID in misleading MI attacks by showing the cosine similarity between trapdoor signatures and generated samples from various attacks (PLG-MI, L-inf, L-2). The results demonstrate that Trap-MID successfully directs MI attacks toward trapdoor triggers, leading to a different distribution of recovered samples.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of trapdoor detection.

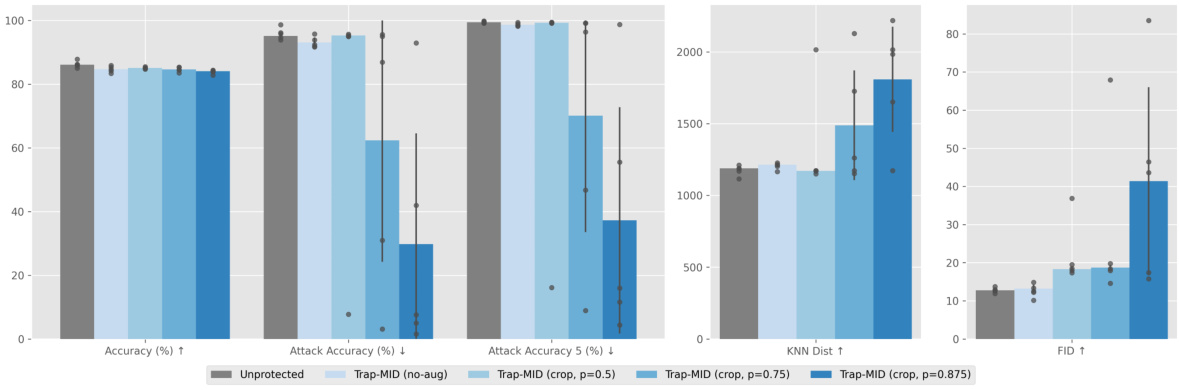

🔼 The figure shows the results of comparing different augmentation strategies against the PLG-MI attack using VGG-16 models. The strategies include no augmentation, random cropping, random cropping and rotation, and random cropping, flipping, and rotation. The metrics used for comparison are attack accuracy (top 1 and top 5), KNN distance, and FID. The results show that Trap-MID with more augmentations is more robust against the PLG-MI attack.

read the caption

Figure 5: Defense comparison with different augmentation against PLG-MI, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This figure compares the defense performance of Trap-MID against the PLG-MI attack using different augmentation probabilities during training. It shows that increasing the probability of applying augmentations (random resized crop in this case) generally improves the robustness of Trap-MID against the attack, reducing attack accuracy and improving metrics like KNN distance and FID. The results suggest that stronger and more frequent augmentations better reveal and address the weaknesses of the trapdoor mechanism, resulting in more stable and effective defense.

read the caption

Figure 6: Defense comparison with different augmentation probabilities against PLG-MI, using VGG-16 models.

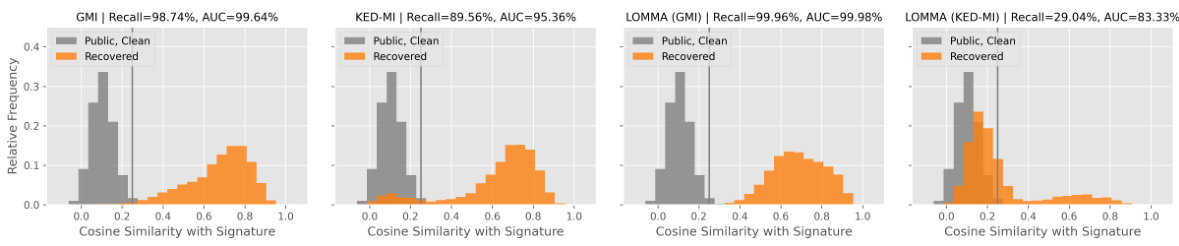

🔼 The figure shows four histograms illustrating the effectiveness of trapdoor detection against different MI attacks (GMI, KED-MI, LOMMA (GMI), LOMMA (KED-MI)). For each attack, two histograms are shown: one for the cosine similarity of clean public data with the trapdoor signature, and one for the cosine similarity of recovered data (generated by the MI attack) with the trapdoor signature. The histograms illustrate that the recovered data from Trap-MID shows a greater similarity to the trapdoor signature compared to the clean public data, thus deceiving the MI attacks.

read the caption

Figure 3: Illustration of trapdoor detection.

🔼 This figure shows the reconstructed images from the state-of-the-art model inversion attack, PLG-MI, using different defense methods. Each row represents a different defense method: unprotected, MID, BiDO, NegLS, Trap-MID, and Trap-MID combined with NegLS. Each column shows a different identity, with the corresponding private image on the top row. The figure visually demonstrates Trap-MID’s superior performance in misleading MI attacks by generating images that are significantly less similar to the private images compared to other methods.

read the caption

Figure 2: Reconstructed images from PLG-MI.

🔼 This figure shows the reconstructed images generated by the state-of-the-art model inversion attack, PLG-MI, targeting different defense methods. The top row displays the original private images. Subsequent rows show the reconstructed images from the unprotected model, MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID. The results from Trap-MID demonstrate that it successfully misleads the PLG-MI attack into producing images visually dissimilar from the actual private data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Reconstructed images from PLG-MI.

🔼 This figure shows the reconstructed images generated by the state-of-the-art model inversion attack, PLG-MI. It compares the quality of the reconstructed images from different defense methods, including no defense, MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID. The figure visually demonstrates the effectiveness of Trap-MID in generating less realistic and less similar images to the private data compared to other methods, showcasing its ability to mislead the attack.

read the caption

Figure 2: Reconstructed images from PLG-MI.

🔼 This figure shows the reconstructed images from PLG-MI attack. It compares the reconstructed images of private data from different defense methods against PLG-MI attack. It demonstrates that Trap-MID outperforms other baseline defense methods in misleading the PLG-MI attack and thus better preserving privacy by generating images less similar to the private data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Reconstructed images from PLG-MI.

🔼 This figure shows the reconstructed images from the PLG-MI attack under different defense methods. The top row displays the original private images. Subsequent rows show images reconstructed by the PLG-MI attack without any defense (Unprotected), and with the following defenses applied: MID, BiDO, NegLS, Trap-MID, and Trap-MID combined with NegLS. The images visually demonstrate the effectiveness of Trap-MID in preventing the reconstruction of realistic and private-looking images compared to the other defense methods.

read the caption

Figure 2: Reconstructed images from PLG-MI.

🔼 This figure displays the results of applying the PLG-MI attack (a state-of-the-art model inversion attack) to reconstruct images from a facial recognition model that has been protected using different methods. The top row shows the original private images. Subsequent rows showcase the reconstructed images obtained using various defense mechanisms, including MID, BiDO, NegLS, Trap-MID, and Trap-MID combined with NegLS. The images illustrate the effectiveness of each defense strategy in preventing the successful reconstruction of private data.

read the caption

Figure 2: Reconstructed images from PLG-MI.

More on tables

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different defense mechanisms against three different model inversion attacks (GMI, KED-MI, and PLG-MI) using the VGG-16 model. The table shows the attack accuracy (AA-1 and AA-5), KNN distance, and FID for each defense method, allowing for a quantitative comparison of their effectiveness in mitigating these attacks. Lower values for AA-1 and AA-5, and higher values for KNN distance and FID generally indicate better defense performance. The defense methods compared include MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID.

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

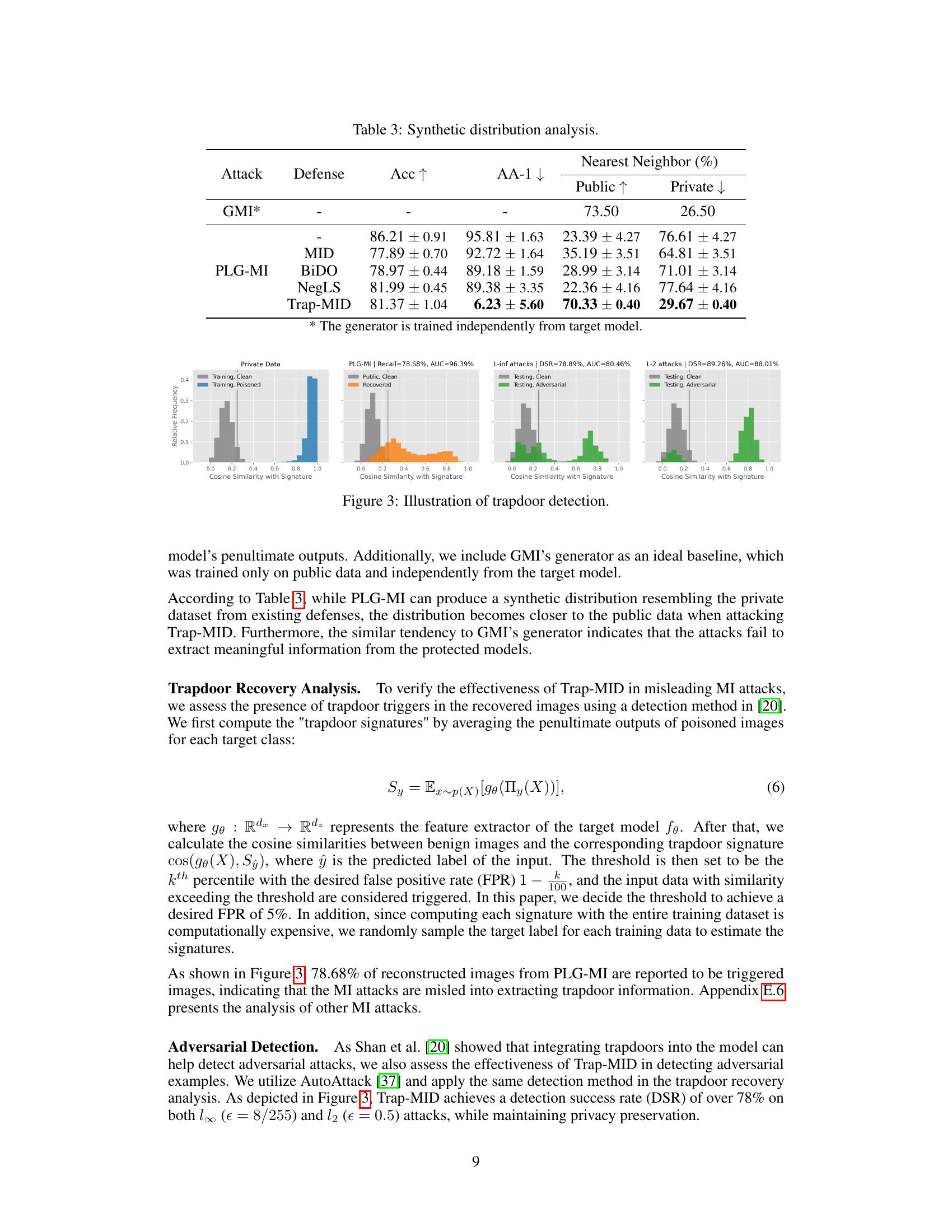

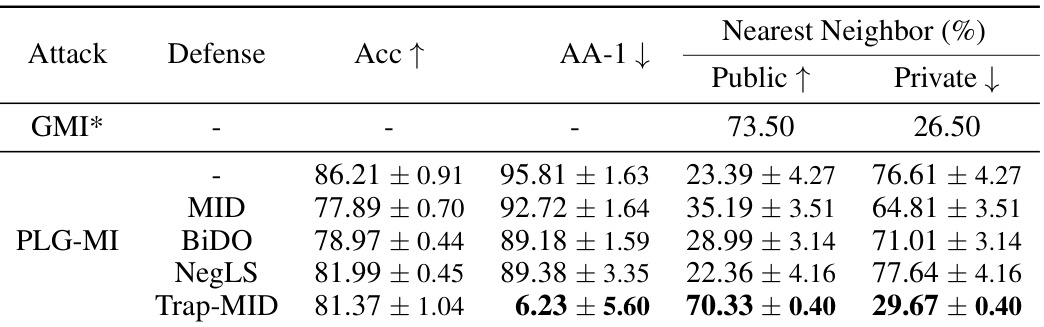

🔼 This table presents the results of an analysis conducted to determine whether the generator used in the PLG-MI attack primarily reconstructs images from the public or private data distribution after training with Trap-MID. It shows the attack accuracy, along with the percentage of nearest neighbors found in the public and private datasets for each generated image, across multiple attack methods. The goal is to understand how effective Trap-MID is at causing the attack to leverage public data instead of private data.

read the caption

Table 3: Synthetic distribution analysis.

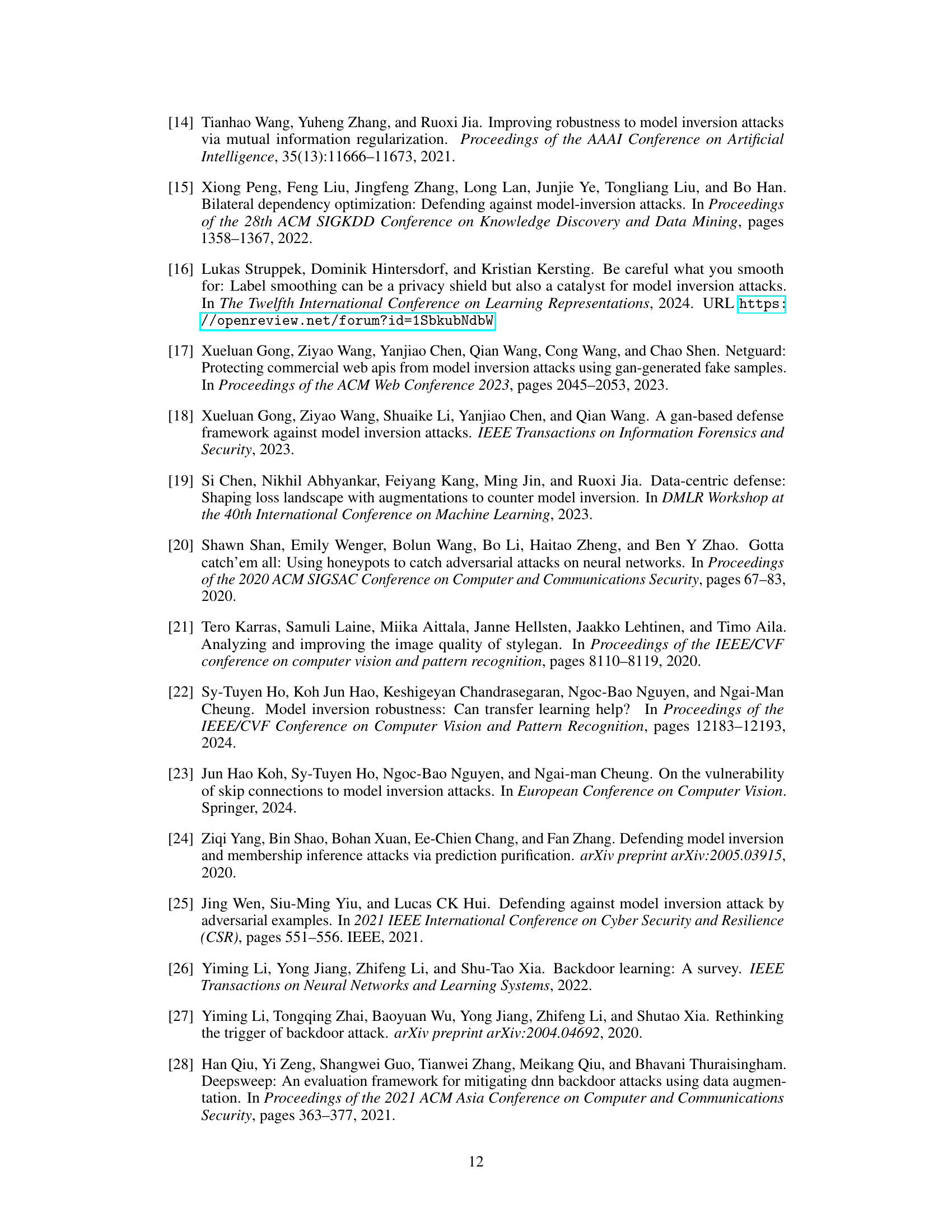

🔼 This table presents the results of adaptive attacks against Trap-MID using VGG-16 models. The adaptive attacks leverage knowledge of the trapdoor signatures. The table shows the attack accuracy (AA-1, AA-5), KNN distance, and FID for CelebA and FFHQ datasets under both PLG-MI and the modified PLG-MI++ adaptive attack.

read the caption

Table 4: Adaptive attacks against Trap-MID, using VGG-16 models.

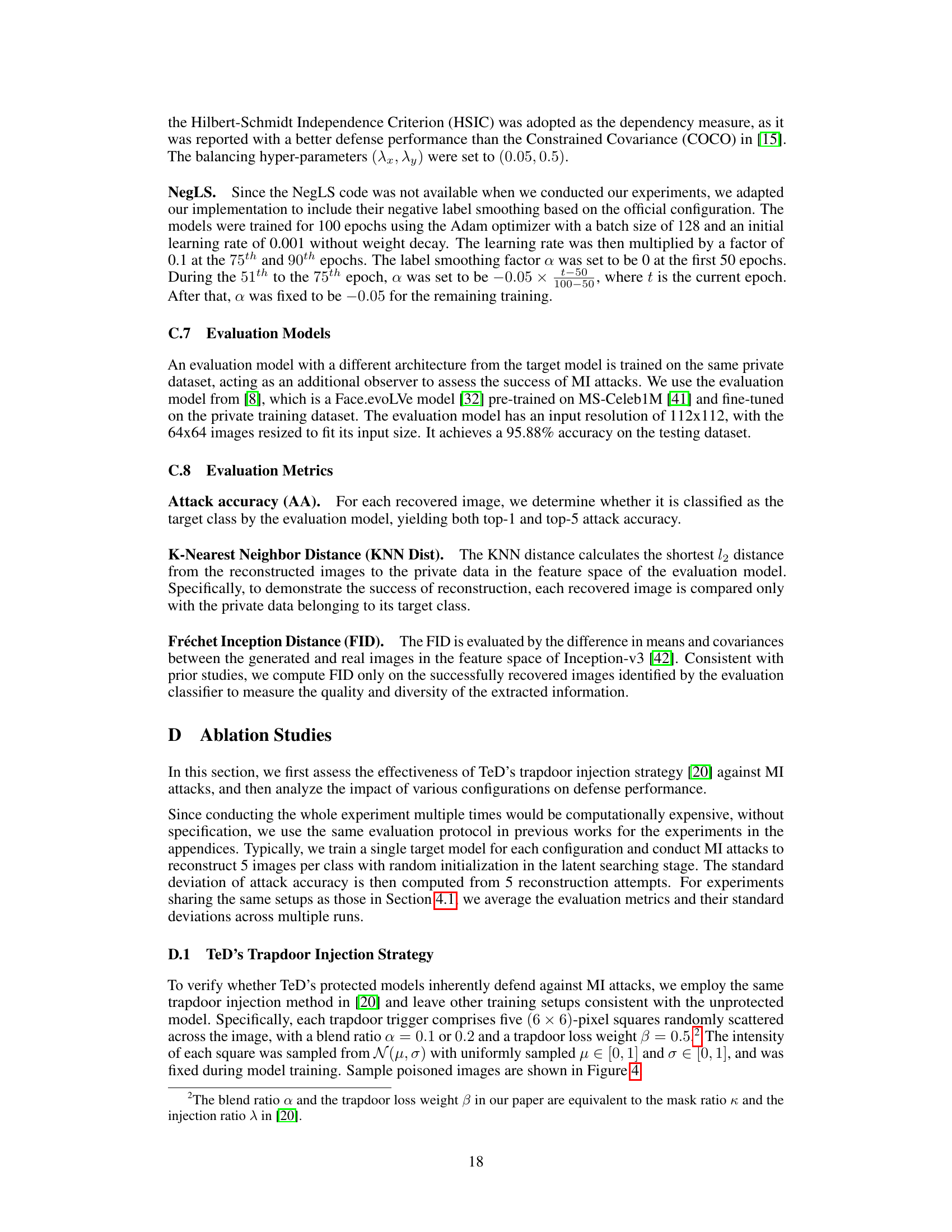

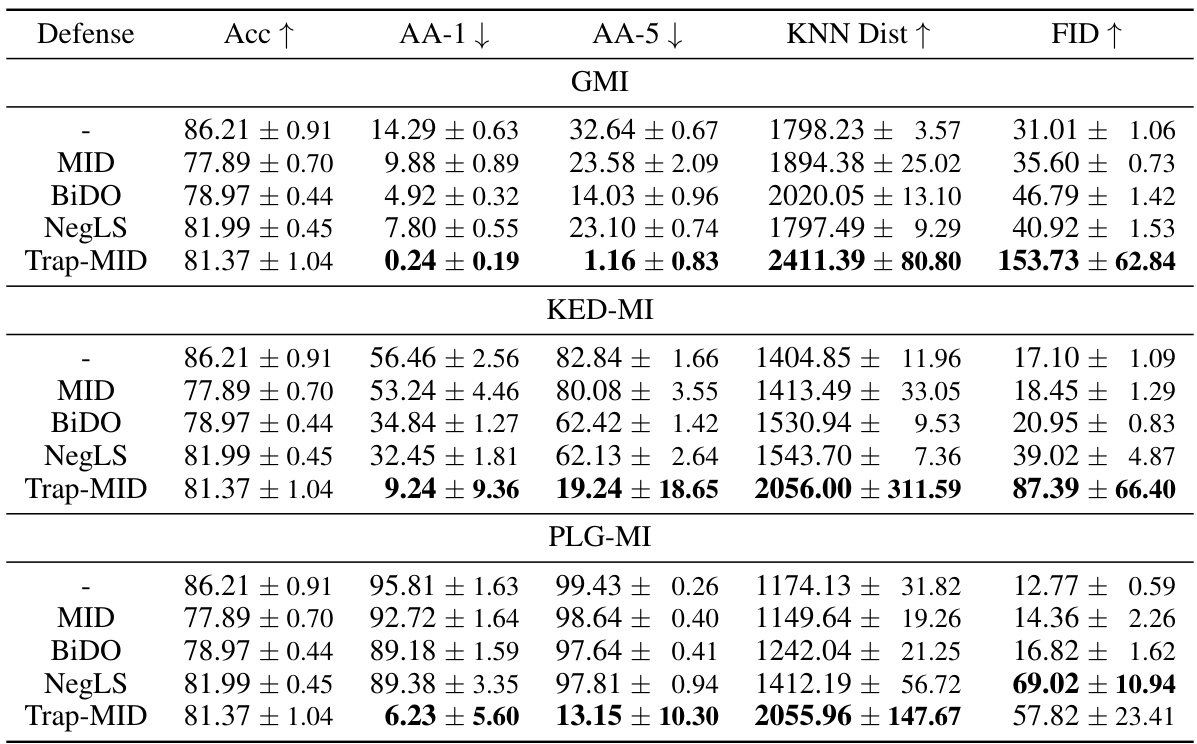

🔼 This table compares the defense performance of Trap-MID against various model inversion attacks (GMI, KED-MI, LOMMA, and PLG-MI) with different trigger injection methods, including TeD’s method and Trap-MID’s method. It shows the attack accuracy (AA-1 and AA-5), KNN distance, and FID for each attack method and defense strategy. The results demonstrate the superiority of Trap-MID in mitigating these attacks.

read the caption

Table 5: Defense comparison with TeD's trapdoors, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different defense mechanisms against various model inversion (MI) attacks using the VGG-16 model. The table shows the performance of different defense methods (MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID) in terms of accuracy, attack accuracy (AA-1, AA-5), KNN distance, and FID. The results demonstrate the relative effectiveness of each defense against different MI attack variations (GMI, KED-MI, and PLG-MI).

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the defense performance of Trap-MID against various model inversion attacks (GMI, KED-MI, LOMMA, and PLG-MI) using different blend ratios (α). The blend ratio controls the strength of the trapdoor injection. The results show how different blend ratios affect the accuracy of the model and its ability to defend against MI attacks. Lower blend ratios generally result in better defense performance but might slightly reduce the overall accuracy.

read the caption

Table 7: Defense comparison with different blend ratios, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different defense mechanisms against various model inversion (MI) attacks using the VGG-16 model. The table shows the attack accuracy (AA-1 and AA-5), K-Nearest Neighbor Distance (KNN Dist), and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) for each defense method. Lower attack accuracy, higher KNN distance, and higher FID indicate better defense performance. The defenses compared include MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID, with Trap-MID showing superior performance across all attacks.

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of the training times required for different defense methods, namely, no defense, MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID, all using VGG-16 models. It shows that Trap-MID has a significantly longer training time than the other methods.

read the caption

Table 9: Training time comparison, using VGG-16 models.

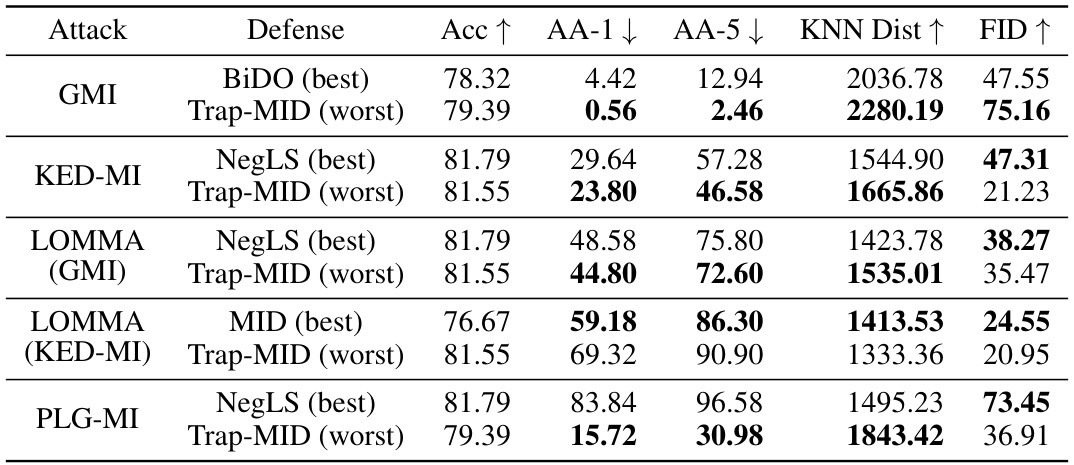

🔼 This table compares the worst-case performance of the Trap-MID defense against various model inversion attacks with the best-case performance of existing defenses (MID, BiDO, NegLS). It shows that even in its worst-case scenarios, Trap-MID outperforms other defenses in terms of attack accuracy (AA-1, AA-5), KNN distance, and FID, demonstrating its robustness.

read the caption

Table 10: The worst-case performance of Trap-MID compared to the best-case performance of existing defenses, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different defense methods against the PLG-MI attack, using a VGG-16 model. It provides a detailed comparison using several metrics beyond simple attack accuracy. These include: Accuracy, FaceNet feature distance (face), Improved Precision and Recall, Density, and Coverage. These metrics offer a more comprehensive assessment of the effectiveness of the defenses by examining various aspects of the reconstructed images’ similarity to the original private data.

read the caption

Table 11: Defense comparison against PLG-MI, using VGG-16 models and measuring with additional evaluation metrics.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different defense mechanisms against various model inversion (MI) attacks using VGG-16 models. The table shows the performance of different defenses in terms of accuracy, attack accuracy (top-1 and top-5), KNN distance, and FID. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed Trap-MID defense compared to existing methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Trap-MID against several state-of-the-art model inversion (MI) attacks, using a VGG-16 model. It shows the attack accuracy (AA-1 and AA-5), KNN distance, and FID for various defenses (MID, BiDO, NegLS, and Trap-MID) against three different MI attacks (GMI, KED-MI, and PLG-MI). The metrics provide a quantitative measure of how well each defense protects against MI attacks.

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different defense methods against the PLG-MI attack when using the FFHQ dataset as the auxiliary dataset for the attack. It shows the attack accuracy (AA-1 and AA-5), KNN distance, and FID for each defense method, providing a comprehensive evaluation of their effectiveness in mitigating privacy leakage.

read the caption

Table 14: Defense comparison against PLG-MI with FFHQ dataset, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different defense mechanisms against three model inversion attacks (GMI, KED-MI, and PLG-MI) using the VGG-16 model. It shows the attack accuracy (AA-1 and AA-5), KNN distance, and FID for each defense method. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of Trap-MID in mitigating MI attacks compared to other baselines (MID, BiDO, and NegLS).

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different defense methods against various model inversion (MI) attacks using VGG-16 models. It shows the attack accuracy (AA-1 and AA-5, representing top-1 and top-5 accuracy, respectively), KNN distance (a measure of similarity between reconstructed and private data), and FID (Fréchet Inception Distance, a measure of image quality and diversity). Lower AA-1, AA-5, and higher KNN Dist, FID values indicate better defense performance.

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table presents a comparison of different defense methods against various model inversion (MI) attacks using VGG-16 models. It shows the attack accuracy (AA-1 and AA-5), K-Nearest Neighbor distance (KNN Dist), and Fréchet Inception Distance (FID) for each defense method. The table helps to illustrate the effectiveness of each defense against different MI attacks and highlights the performance of Trap-MID in comparison to existing methods.

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

🔼 This table compares the performance of different defense methods against BREP-MI attacks, which is a label-only attack. The table shows the accuracy (Acc) of each defense method when the attacker tries to recover 300 identities, the number of initial iterations required for successful recovery and the top-1 attack accuracy (AA-1) which measures how well the attack reconstructs images.

read the caption

Table 18: Defense comparison against BREP-MI, using untargeted attacks to recover 300 identities.

🔼 This table compares the performance of Trap-MID against other defense methods (MID, BiDO, and NegLS) when facing various model inversion (MI) attacks (GMI, KED-MI, and PLG-MI). It shows the attack accuracy (AA-1, AA-5), KNN distance, and FID values for each defense method and attack. Higher values for KNN distance and FID indicate that the recovered images are less similar to the private images.

read the caption

Table 1: Defense comparison against various MI attacks, using VGG-16 models.

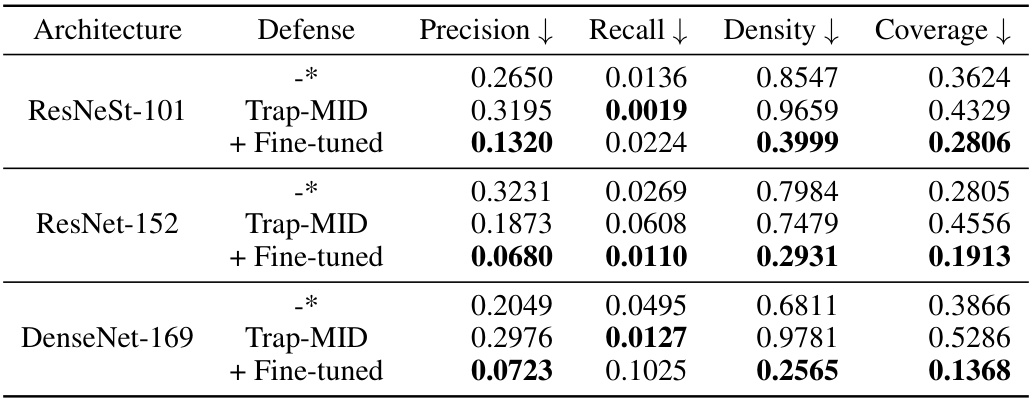

🔼 This table presents additional evaluation metrics for the defense performance against PPA attacks. The metrics include Precision, Recall, Density, and Coverage, all calculated in the InceptionV3 feature space. Lower values generally indicate better defense performance. The table shows the results for three different model architectures (ResNeSt-101, ResNet-152, and DenseNet-169) with and without Trap-MID and fine-tuning.

read the caption

Table 20: Additional evaluation results of the defense performance against PPA.

Full paper#