↗ OpenReview ↗ NeurIPS Homepage ↗ Chat

TL;DR#

Language-guided robotic manipulation is challenging due to the complexity of tasks and the difficulty in bridging high-level instructions to low-level robot actions. Previous methods struggle with directly mapping instructions to actions, leading to poor generalization and fragility to environmental changes. They also suffer from high computational redundancy.

PIVOT-R tackles these issues by introducing a primitive-driven waypoint-aware world model that predicts key waypoints in manipulation tasks. A lightweight action prediction module then uses these waypoints to generate precise actions. Furthermore, an asynchronous hierarchical executor improves efficiency by running different modules at optimal frequencies. The results demonstrate that PIVOT-R outperforms existing methods on the SeaWave benchmark, highlighting the effectiveness of its approach.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it significantly improves the performance and efficiency of language-guided robotic manipulation. The asynchronous hierarchical executor and waypoint-aware world model are novel approaches that address limitations of previous methods. This opens avenues for research into more efficient and robust robotic systems that can effectively understand and execute complex instructions.

Visual Insights#

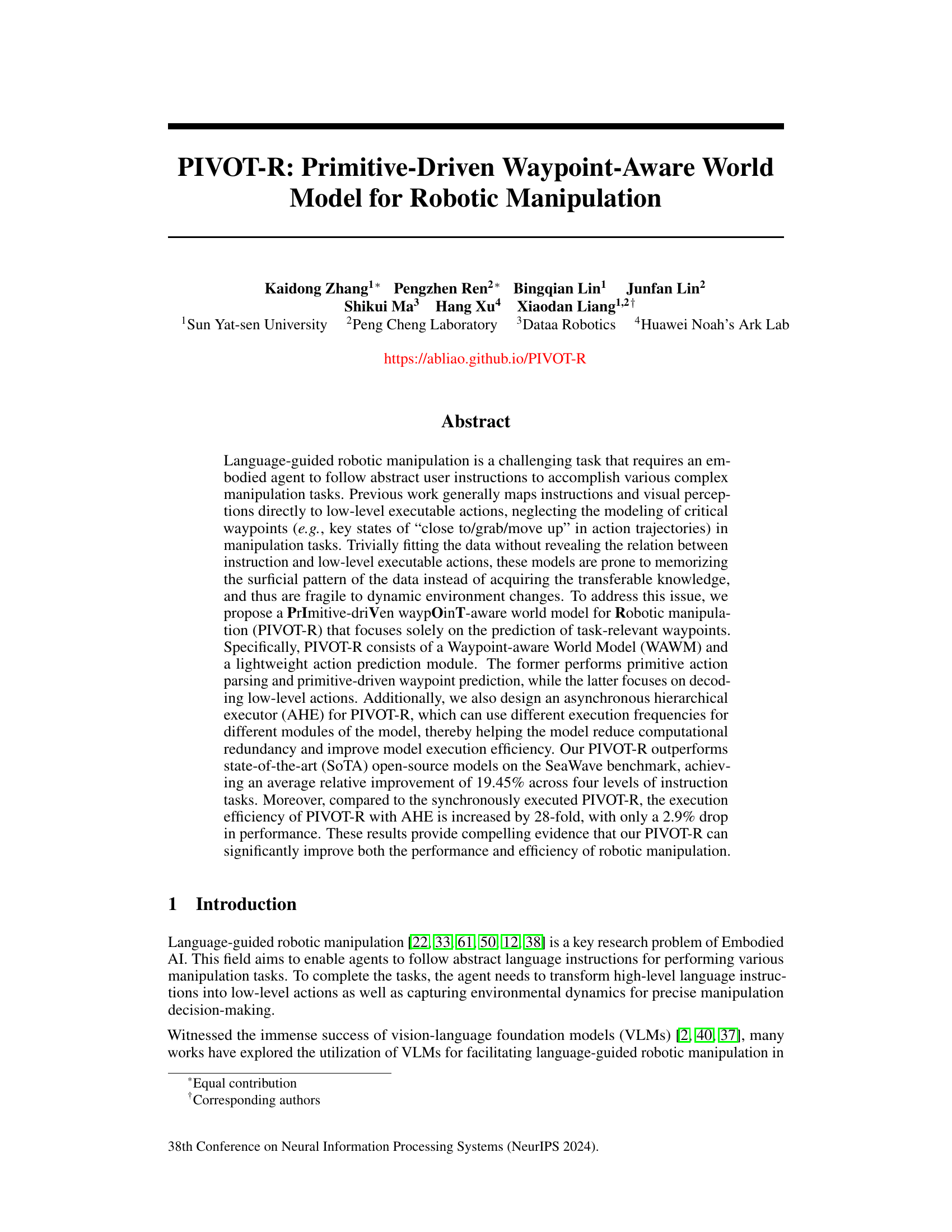

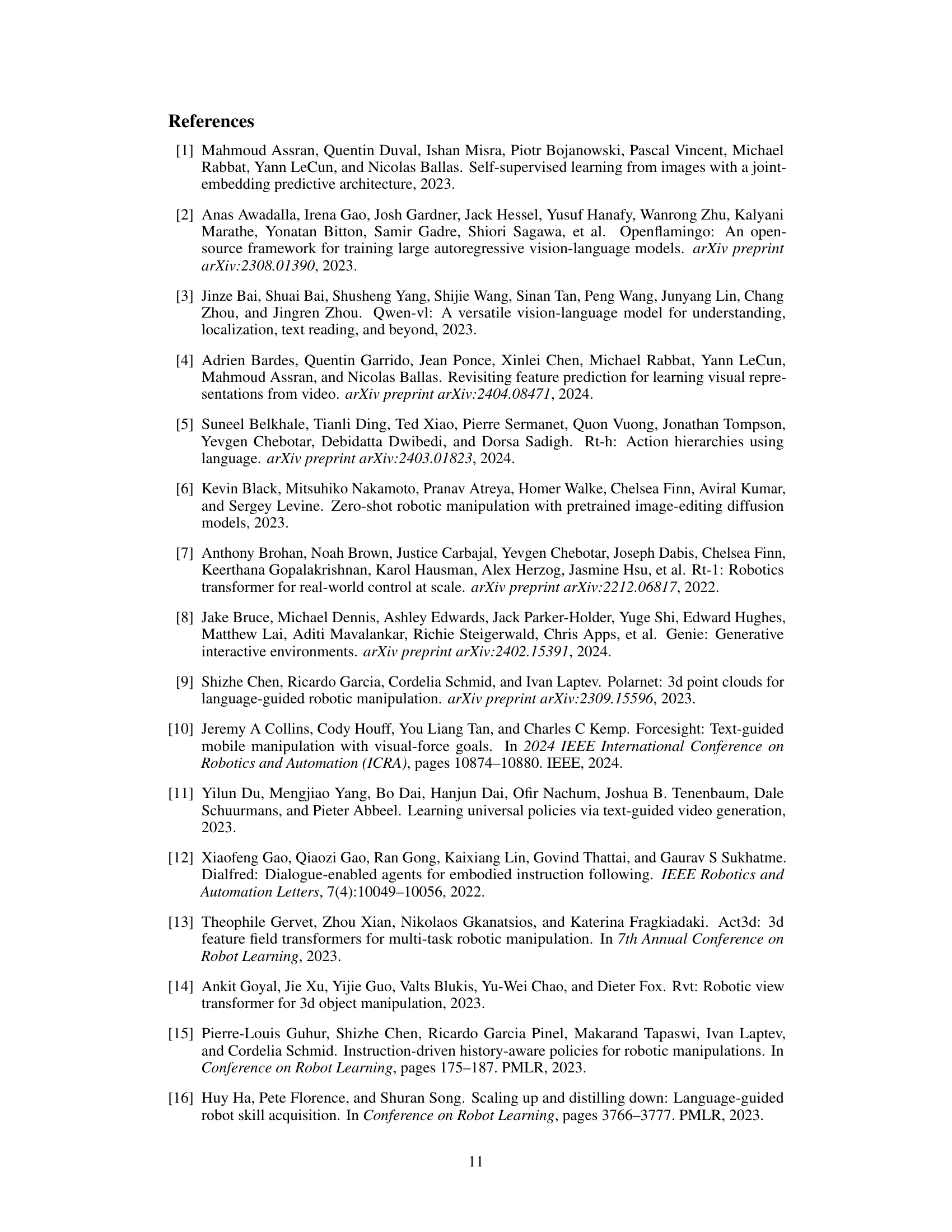

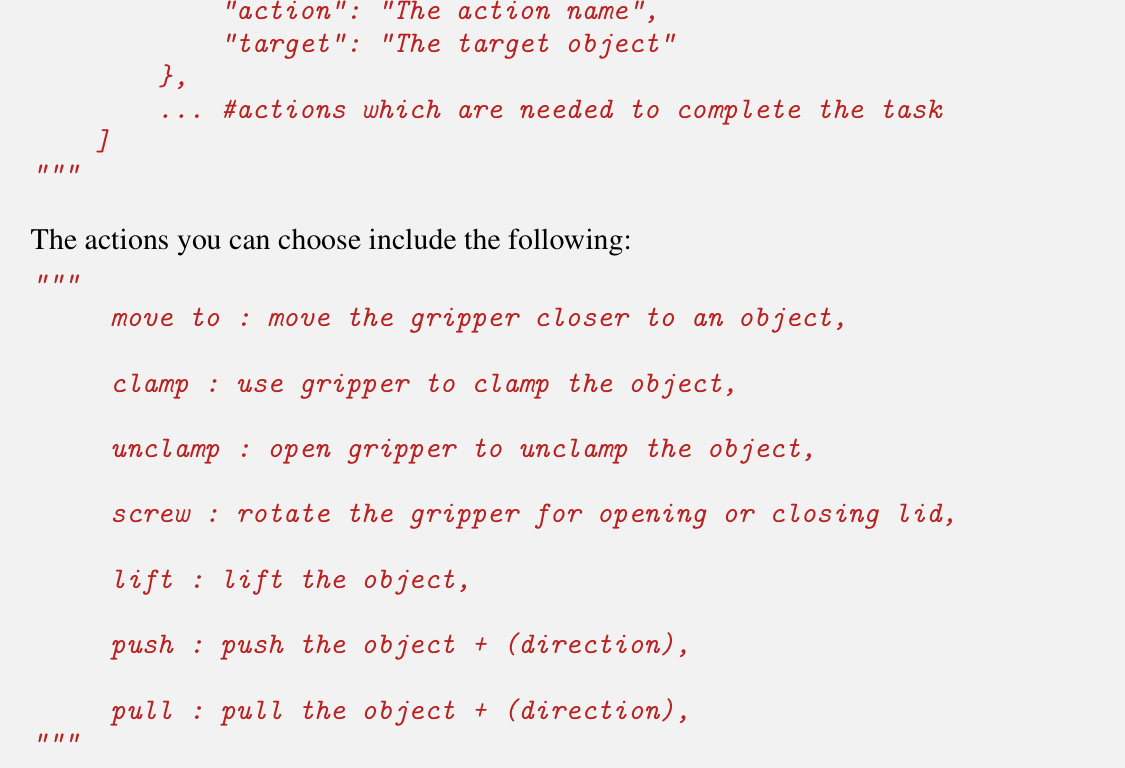

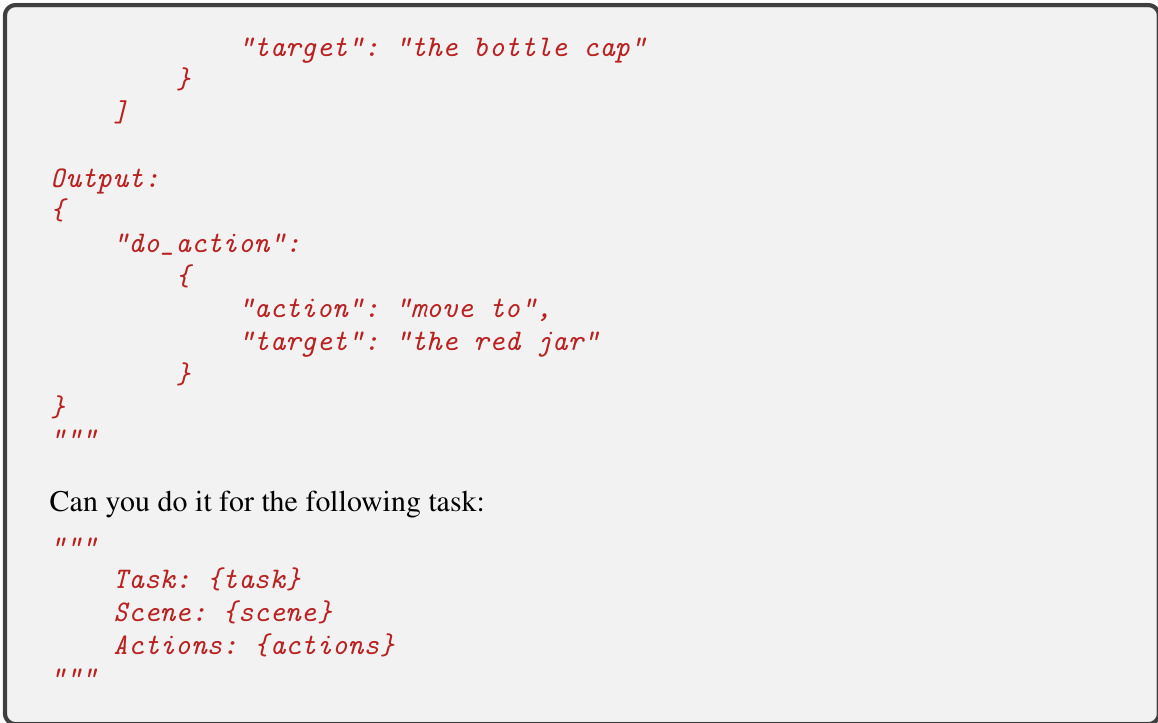

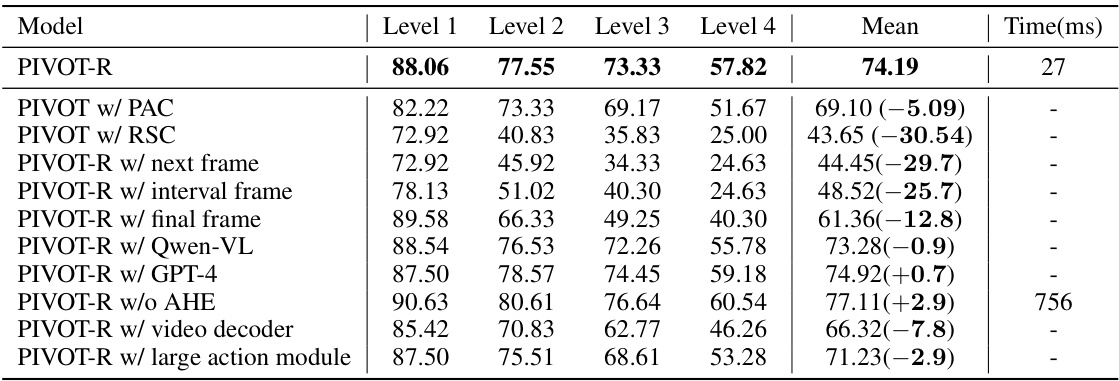

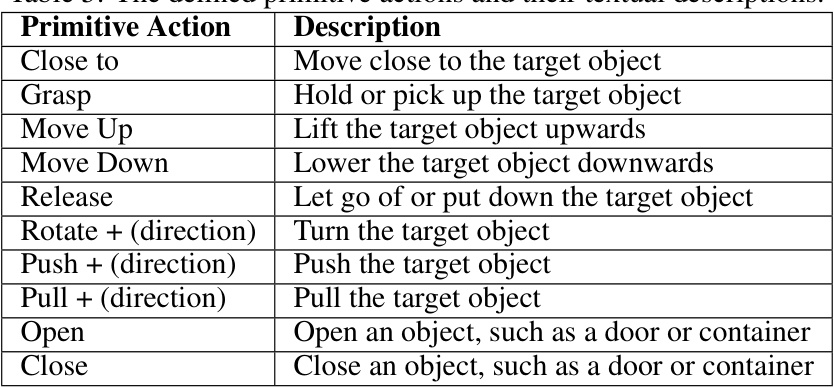

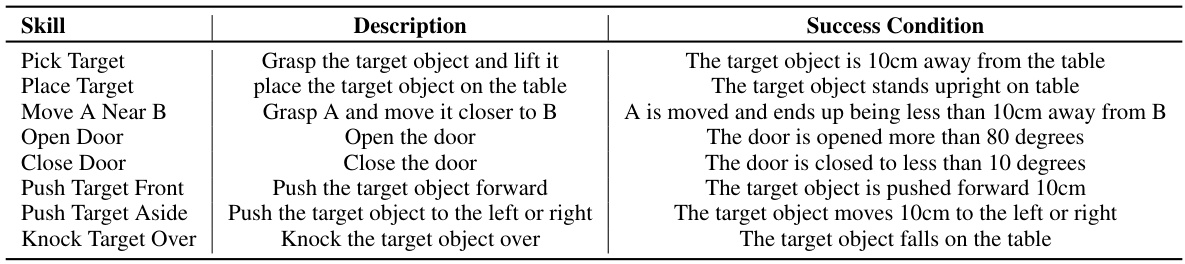

This figure compares the architecture of PIVOT-R with traditional sequentially executed robot manipulation models. Traditional models process visual input and instructions sequentially through multiple modules (VLM, world model, action head) at every timestep, leading to redundancy and difficulty in predicting key manipulation waypoints. In contrast, PIVOT-R uses an asynchronous hierarchical executor and focuses solely on predicting task-relevant waypoints, improving efficiency and reducing redundancy. The waypoints guide a lightweight action prediction module for low-level action decoding.

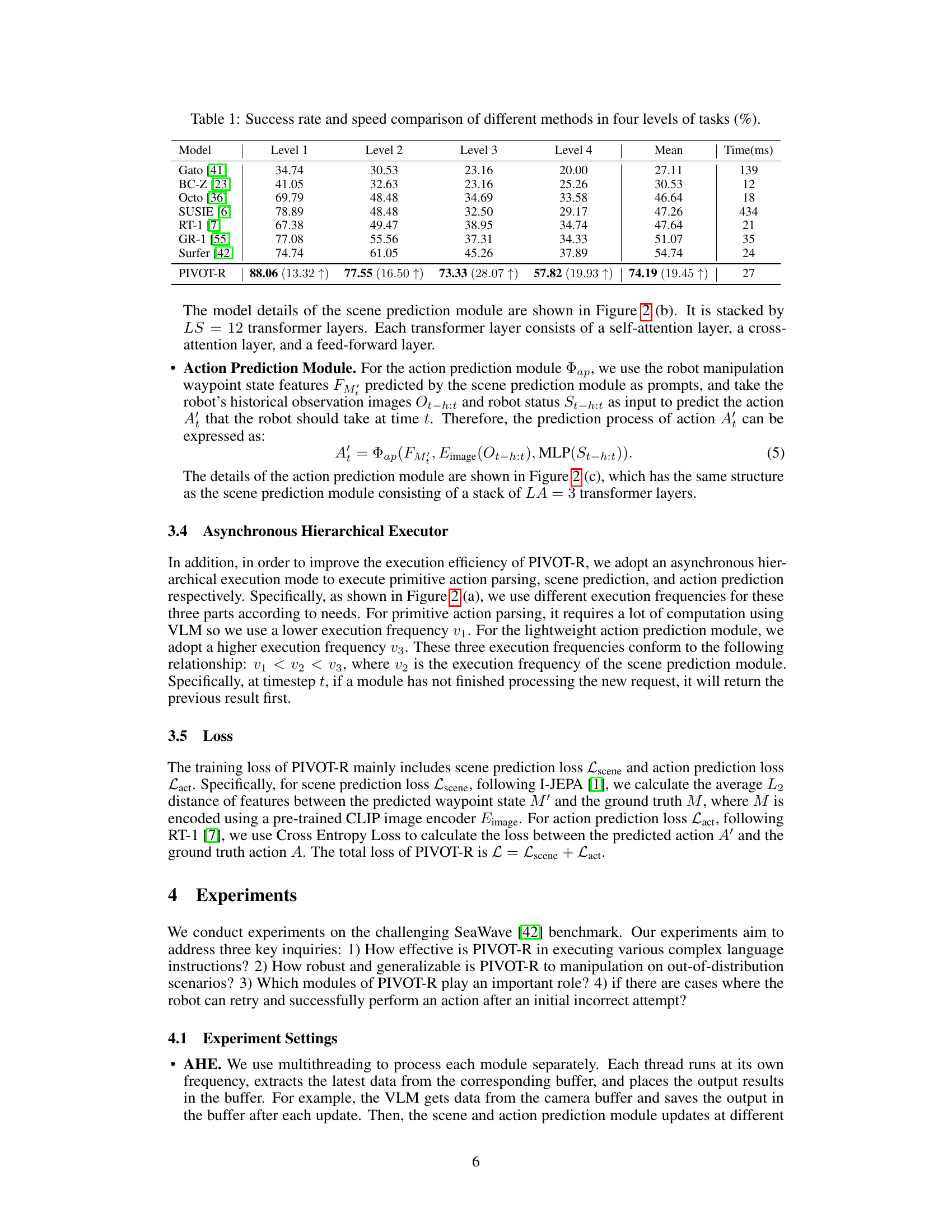

This table compares the performance of different models (Gato, BC-Z, Octo, SUSIE, RT-1, GR-1, Surfer, and PIVOT-R) across four levels of robotic manipulation tasks. For each model, it shows the success rate (percentage of tasks successfully completed) for each task level and the average success rate across all levels. It also provides the average time (in milliseconds) taken for each model to complete a single step in the manipulation tasks. The numbers in parentheses indicate the relative improvement of PIVOT-R compared to the best-performing baseline model.

In-depth insights#

Waypoint Modeling#

Waypoint modeling in robotics is crucial for bridging the gap between high-level instructions and low-level actions. Effective waypoint selection is key, focusing on task-relevant states rather than simply modeling every timestep. This allows the robot to prioritize critical points in the action trajectory, improving efficiency and robustness. A well-designed waypoint model should incorporate contextual information from both language instructions and visual perception. The model needs to understand the semantics of the instructions to identify meaningful waypoints, like “grasp the object” or “move to the table.” Integration with world models is advantageous, providing a richer understanding of the environment and enabling more accurate waypoint predictions. Furthermore, a robust waypoint model should be capable of handling dynamic environments, adapting to unexpected changes and uncertainties. Ultimately, the success of waypoint modeling hinges on its ability to generalize across tasks and scenes, requiring thorough evaluation and potentially the incorporation of techniques like transfer learning.

Async. Execution#

Asynchronous execution, in the context of a robotic manipulation system, offers a powerful mechanism to enhance efficiency and responsiveness. By decoupling the execution of different modules (such as perception, planning, and action), asynchronous execution allows for parallel processing, where computationally intensive tasks can proceed concurrently without blocking less demanding ones. This is particularly valuable in dynamic environments where real-time responsiveness is crucial. The benefits include reduced latency, as modules can operate at their own optimal frequency, potentially leading to faster reaction times and improved overall system throughput. Careful design is needed, however, to manage data dependencies and synchronization between asynchronously running modules. A well-implemented asynchronous system can significantly reduce computational redundancy and streamline the robotic workflow; poorly designed ones risk introducing errors or inconsistencies.

SeaWave Results#

The SeaWave results section would ideally present a thorough evaluation of the proposed PIVOT-R model against existing state-of-the-art (SOTA) methods. A strong analysis would involve quantitative metrics like success rates across various task difficulty levels, along with qualitative observations illustrating the model’s behavior in diverse scenarios. Crucially, the results should be statistically sound, possibly with error bars or confidence intervals to demonstrate significance. Comparison to baselines is essential, showcasing PIVOT-R’s improvement or limitations. Any ablation studies removing specific components would provide insight into their individual contributions. Finally, a discussion on generalization ability, including performance on unseen tasks or environments, and an analysis of potential failures or limitations would be vital for a comprehensive assessment of the model’s efficacy and robustness.

Generalization#

The concept of generalization in the context of a research paper, especially one involving AI models, is crucial. It refers to the model’s ability to perform well on unseen data or tasks that differ from those it was trained on. High generalization capacity is a key indicator of a robust and effective model, as it signifies its ability to adapt and make accurate predictions in real-world scenarios. A model with poor generalization might overfit to its training data, showing high performance on training samples but significantly reduced accuracy on new, unseen data. Factors influencing generalization include the quality and diversity of training data, the model’s architecture, and the regularization techniques used. An in-depth analysis of a paper’s approach to generalization would explore the specific methods employed to mitigate overfitting, such as dropout or weight decay, and would analyze the performance metrics reported for both training and testing datasets. The evaluation should cover various scenarios to assess the model’s adaptability in real-world, diverse conditions. A strong focus on generalization is vital as it demonstrates the practical value and wider applicability of any AI model.

Future Work#

Future research directions stemming from this paper could involve several key areas. Extending the model’s capacity to handle more complex manipulation tasks is crucial. This could involve incorporating more sophisticated reasoning capabilities to manage multi-step instructions, incorporating more challenging environments, and increasing the complexity of the tasks to include multi-object interactions, particularly those requiring nuanced spatial reasoning or dexterous manipulation. Additionally, improving the model’s robustness to unseen situations and disturbances is paramount. Investigating techniques for improving the model’s generalization to novel environments and its ability to handle unexpected events (e.g., objects falling or being knocked over) would significantly enhance its practical applicability. Finally, assessing the model’s performance and limitations in real-world settings is essential. This requires rigorous testing in uncontrolled environments, along with analyses to identify scenarios where the model struggles. Furthermore, exploration of alternative execution strategies could lead to efficiency improvements, potentially through the optimization of the asynchronous execution methods. The integration of advanced planning techniques would also improve performance on complex manipulation tasks.

More visual insights#

More on figures

This figure compares PIVOT-R with other robot manipulation models. (a) shows a sequential model where modules are executed at every timestep, leading to redundancy and weak waypoint prediction. (b) illustrates PIVOT-R, which focuses on predicting task-relevant waypoints using an asynchronous hierarchical executor for improved efficiency and performance.

This figure shows the overall architecture of PIVOT-R, highlighting its three main modules: the asynchronous hierarchical executor (AHE), the waypoint-aware world model (WAWM), and the action prediction module. The AHE coordinates the execution of the modules at different frequencies to optimize efficiency. The WAWM uses a pre-trained Vision-Language Model (VLM) for primitive action parsing and scene prediction, focusing on key waypoints in the manipulation task. The action prediction module then generates the low-level actions based on these waypoints. The figure also provides a detailed breakdown of the scene and action prediction module architectures, illustrating the components used within each module (e.g., self-attention, cross-attention, feed-forward layers).

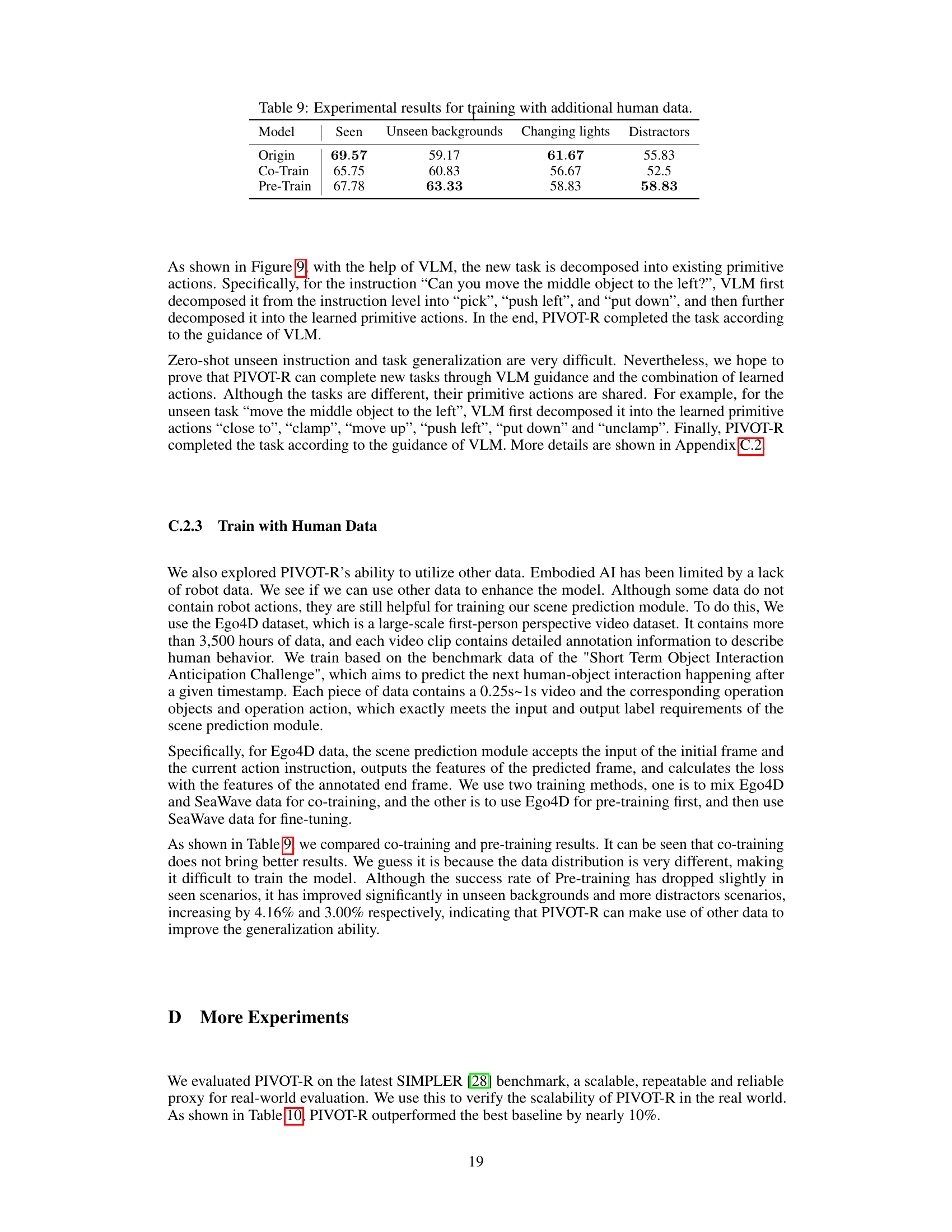

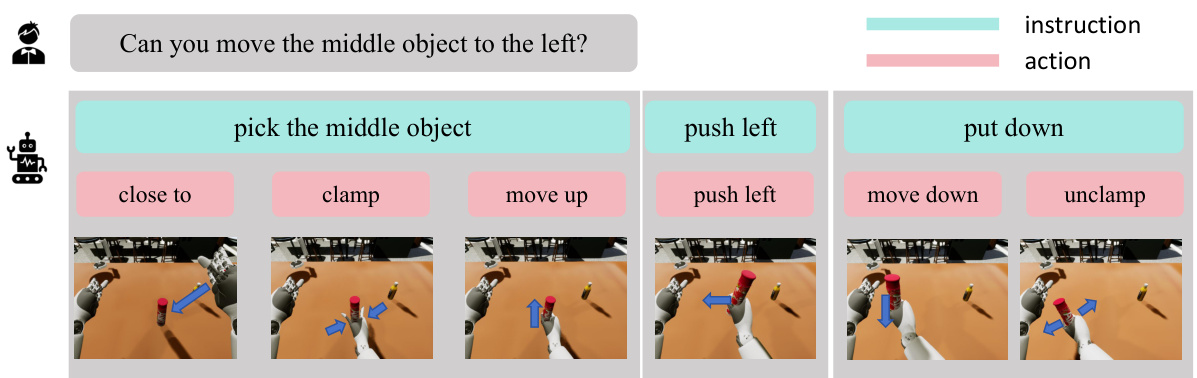

This figure demonstrates a step-by-step execution of a robotic manipulation task using the PIVOT-R model. Each image shows a different stage of the task, with text indicating the primitive action being performed at that stage. Blue arrows illustrate the movement direction. This visualization helps illustrate the model’s ability to break down complex tasks into smaller, manageable primitive actions.

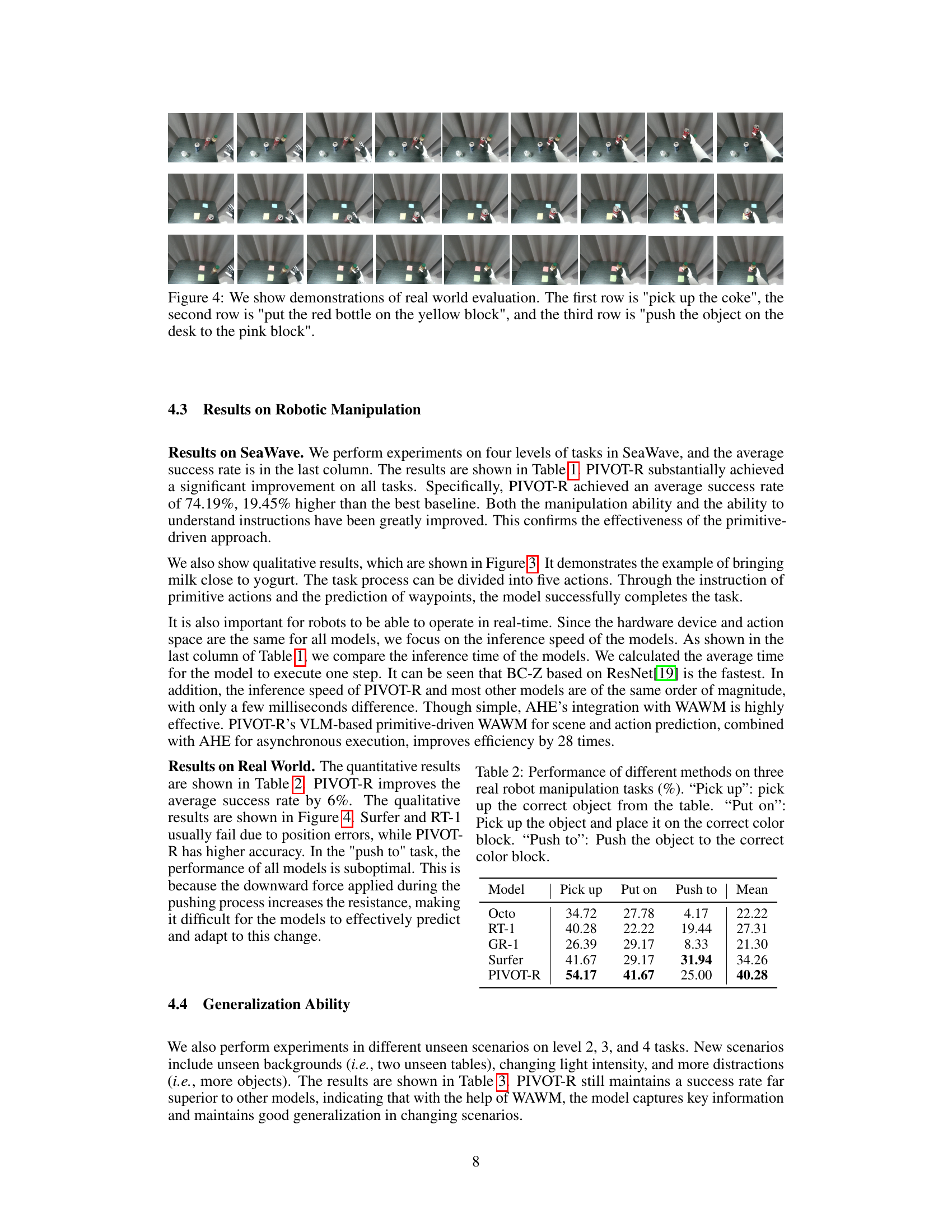

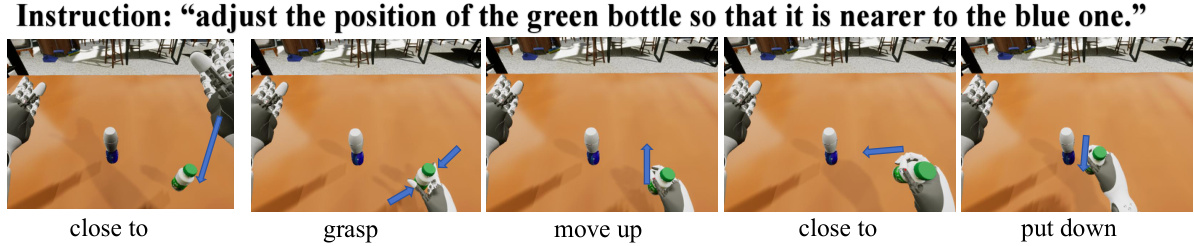

This figure presents three example scenarios from real-world robot manipulation experiments using PIVOT-R. Each row shows a different task: picking up a coke can, placing a red bottle on a yellow block, and pushing an object towards a pink block. The images visually depict the robot’s actions during the execution of these tasks, offering a qualitative assessment of the model’s performance in real-world settings.

This figure shows three scenarios of robotic manipulation: a successful retry after an initial failure, a failed retry, and an unrecoverable failure. The successful retry illustrates the robot’s ability to recover from minor errors, while the failed retry and unrecoverable failure highlight situations where the error is more significant and beyond the robot’s recovery capabilities.

This figure shows various scenes from the SeaWave benchmark dataset used in the paper. The left column displays the scene from a first-person perspective (as if the robot were viewing it), while the right column offers a third-person perspective. Each row depicts the same scene, demonstrating different viewpoints of the simulation environment used for training and evaluating the robotic manipulation model. This helps showcase the visual complexity and variability in the environments the model has to handle.

This figure shows a feature analysis that explores the spatial distance relationships between predicted features (FMt) and real-time observed features (F0t) relative to milestone features (FMt). The L2 distance between F0t and FMt is shown to decrease as the task progresses, while the L2 distance between FMt and FMt shows smaller variances in long-term series analysis, indicating more stable predictions. This stability and convergence towards the milestones are highlighted as critical for the accuracy and reliability of model manipulation.

This figure demonstrates an example where the model successfully completes a task despite receiving an instruction that is outside of its training data (out-of-distribution). The Vision-Language Model (VLM) successfully parses the instruction, transforming it into a learned task instruction, which enables the model to perform the task correctly. This highlights the model’s ability to generalize beyond its training data by leveraging the reasoning capabilities of the VLM.

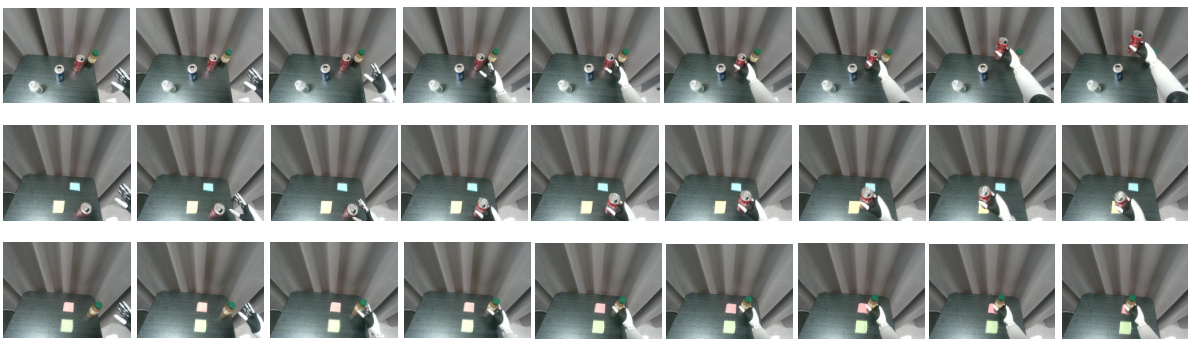

This figure shows an example of how PIVOT-R handles unseen tasks. The instruction is to move a middle object to the left. PIVOT-R decomposes this complex instruction into a sequence of learned sub-tasks (pick the middle object, push left, put down), which are then further broken down into primitive actions (close to, clamp, move up, push left, move down, unclamp). The images show the robot executing these actions sequentially to complete the task. This demonstrates the model’s ability to generalize beyond its training data by combining known skills to solve novel problems.

This figure shows the overall architecture of the PIVOT-R model, which consists of a waypoint-aware world model (WAWM) and an action prediction module. The WAWM uses a pre-trained vision-language model (VLM) for low-frequency primitive action parsing, providing waypoint indications for the scene prediction module. The scene prediction module then models world knowledge using waypoints and manipulation trajectories. Finally, a lightweight action prediction module handles high-frequency action prediction and execution. The three modules operate asynchronously via an asynchronous hierarchical executor (AHE).

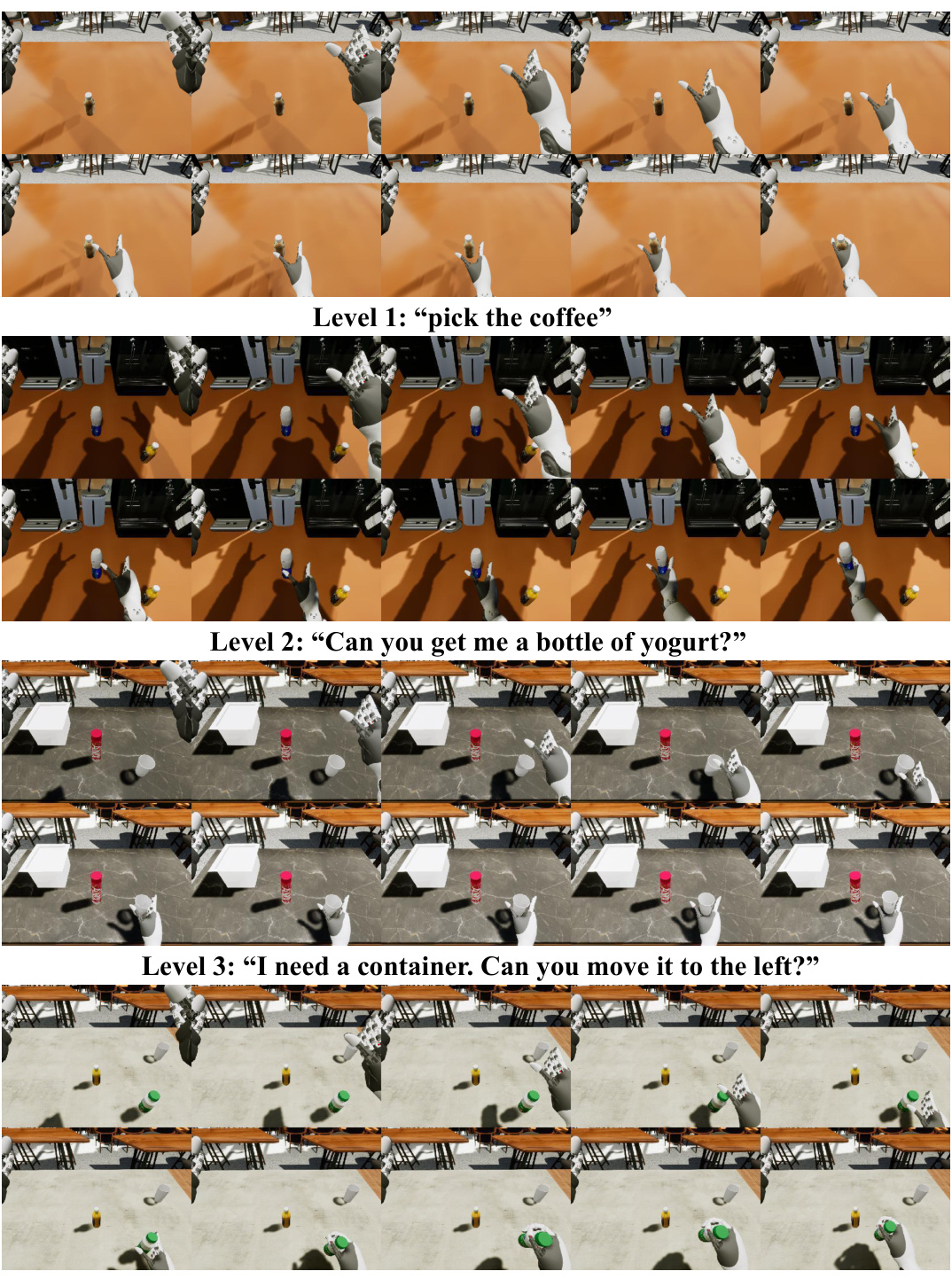

This figure shows example rollouts of the PIVOT-R model on four different levels of tasks from the SeaWave benchmark. Each row represents a different level of complexity in the instructions, with Level 1 being the simplest and Level 4 being the most complex. The images depict the robot’s actions in attempting to complete the tasks based on the given natural language instructions. The figure visually demonstrates the model’s ability to handle various levels of instruction complexity.

This figure provides a detailed overview of the PIVOT-R architecture. It shows how the three main modules (primitive action parsing, scene prediction, and action prediction) work together asynchronously using an asynchronous hierarchical executor. The waypoint-aware world model uses a pre-trained vision-language model (VLM) for primitive action parsing and waypoint prediction to guide the scene and action prediction modules.

This figure shows the overall architecture of PIVOT-R, a primitive-driven waypoint-aware world model for robotic manipulation. It highlights the three main modules: a Waypoint-Aware World Model (WAWM), which uses a pre-trained Vision-Language Model (VLM) for primitive action parsing and scene prediction; an action prediction module for low-level action decoding; and an Asynchronous Hierarchical Executor (AHE) that manages the execution frequency of each module to optimize efficiency. The WAWM focuses on predicting task-relevant waypoints, which are then used by the action prediction module to generate the final robot actions.

This figure shows the overall architecture of PIVOT-R, a primitive-driven waypoint-aware world model for robotic manipulation. It highlights the three main modules: the Waypoint-Aware World Model (WAWM), the scene prediction module, and the action prediction module. The asynchronous hierarchical executor (AHE) coordinates the interaction between the modules, allowing them to operate at different execution frequencies for improved efficiency. WAWM utilizes a pretrained Vision-Language Model (VLM) to parse user instructions and predict waypoints which guide the scene and action prediction modules.

This figure presents a detailed overview of the PIVOT-R architecture, highlighting its key components: a Waypoint-Aware World Model (WAWM) and an Action Prediction module. It illustrates how these modules interact asynchronously through a hierarchical executor (AHE). The WAWM uses a pre-trained Vision-Language Model (VLM) for primitive action parsing, providing waypoint cues to a scene prediction module that models world knowledge. Finally, a lightweight action prediction module generates actions.

This figure provides a detailed overview of the proposed PIVOT-R architecture, illustrating the interaction between its key components: the Waypoint-Aware World Model (WAWM) and the Action Prediction Module. The diagram highlights the asynchronous nature of the system, with different modules operating at varying frequencies. The WAWM uses a pre-trained Vision-Language Model (VLM) for primitive action parsing and scene prediction guided by waypoints, while the Action Prediction Module focuses on high-frequency action prediction and execution. Overall, the figure depicts a hierarchical, efficient system designed for robotic manipulation.

This figure shows the overall architecture of the PIVOT-R model, which consists of three main modules: a Waypoint-Aware World Model (WAWM), a scene prediction module, and an action prediction module. These modules work asynchronously, with different frequencies, to improve efficiency. The WAWM parses user instructions using a pre-trained vision-language model (VLM) to identify key waypoints in the manipulation task, which are then used by the scene prediction module to predict the scene. Finally, the action prediction module uses these predictions to generate low-level actions for the robot.

More on tables

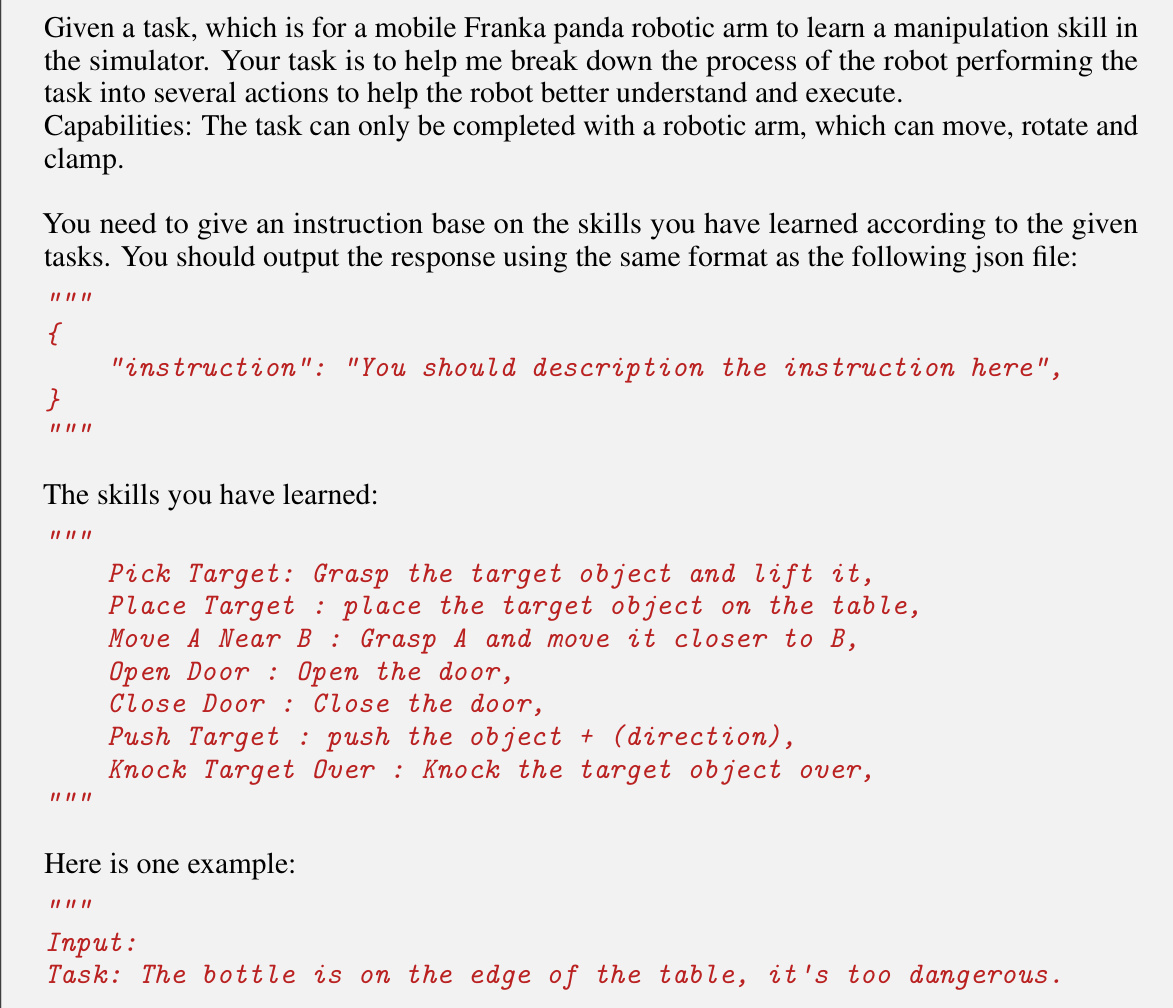

This table presents the performance comparison of different robotic manipulation models on three real-world tasks: picking up an object, placing an object on a colored block, and pushing an object to a colored block. The performance metric is the success rate (percentage) for each task, averaged across multiple trials. The table shows that PIVOT-R outperforms other state-of-the-art methods, indicating the effectiveness of the proposed approach.

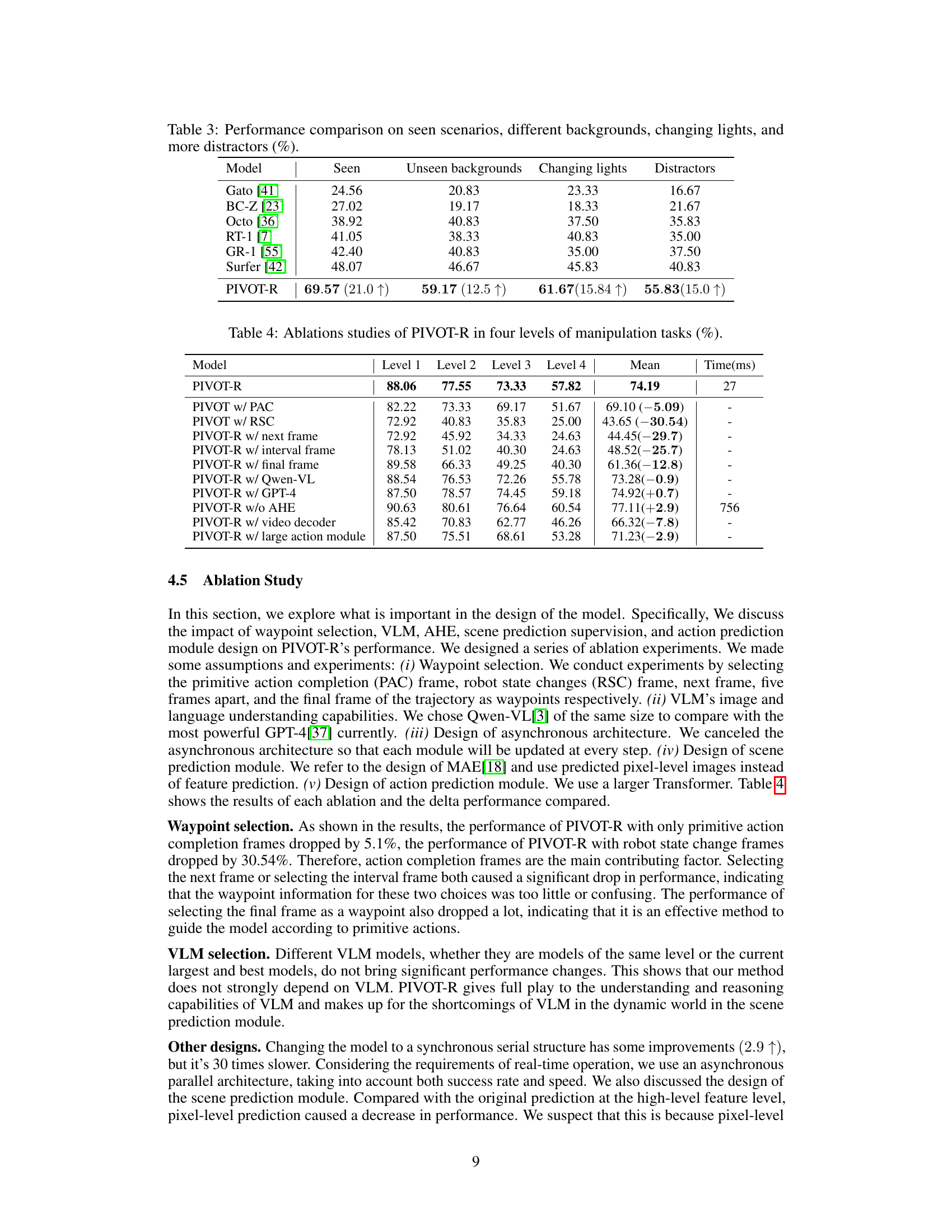

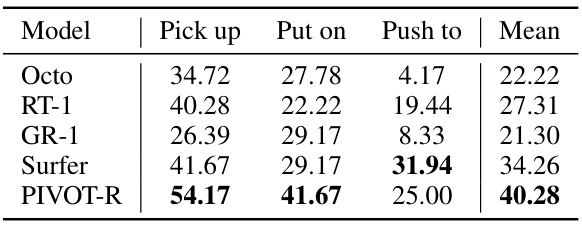

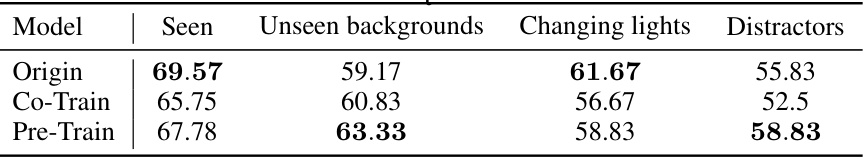

This table presents the results of experiments evaluating the generalization ability of different models, including PIVOT-R, across various scenarios. It compares the success rates of the models under four different conditions: seen scenarios (standard testing conditions), unseen backgrounds, changing lighting conditions, and increased distractions. The results show how well the models generalize beyond the training data and their resilience to environmental variability.

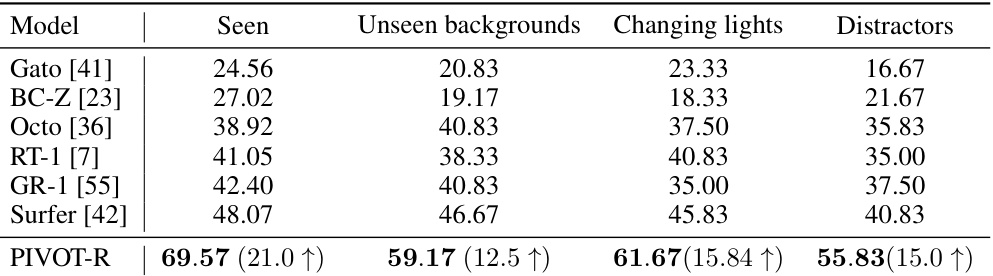

This table presents a comparison of the success rates and inference times of various models on four levels of robotic manipulation tasks from the SeaWave benchmark. Each level represents increasing complexity in the language instructions provided to the robot. The table shows the average success rate across all four levels, along with the average time taken (in milliseconds) for each model to perform a single manipulation step. This allows for a comparison of not only the performance of different models but also their efficiency. The values in parentheses indicate the relative improvement or decrease in performance compared to the best baseline model.

This table presents a comparison of the success rates and inference speeds of various robotic manipulation models across four different difficulty levels. It shows the performance of several state-of-the-art (SOTA) models and the proposed PIVOT-R model. The success rate indicates the percentage of times each model successfully completed a given manipulation task, while the inference speed (in milliseconds) reflects the time taken for the model to execute a single step in the task. The table highlights the relative improvement achieved by PIVOT-R compared to the other models.

This table presents a comparison of the success rates and inference speeds of various models on four different levels of robotic manipulation tasks from the SeaWave benchmark. It shows the average success rate across all four levels for each model, allowing for a comparison of overall performance. The time column indicates the average inference time in milliseconds per step for each model.

This table presents a comparison of the success rates and inference speeds of various models on four different levels of robotic manipulation tasks from the SeaWave benchmark. Higher success rates indicate better performance in completing the tasks, and lower inference times represent greater efficiency. The table shows that PIVOT-R outperforms other state-of-the-art models in terms of both success rate and efficiency.

This table compares the success rates and speeds of various models (Gato, BC-Z, Octo, SUSIE, RT-1, GR-1, Surfer, and PIVOT-R) across four different levels of manipulation tasks in the SeaWave benchmark. Each level represents an increase in complexity in terms of the instructions given to the robot. The table shows PIVOT-R’s significant performance improvement compared to other models, as well as its inference speed.

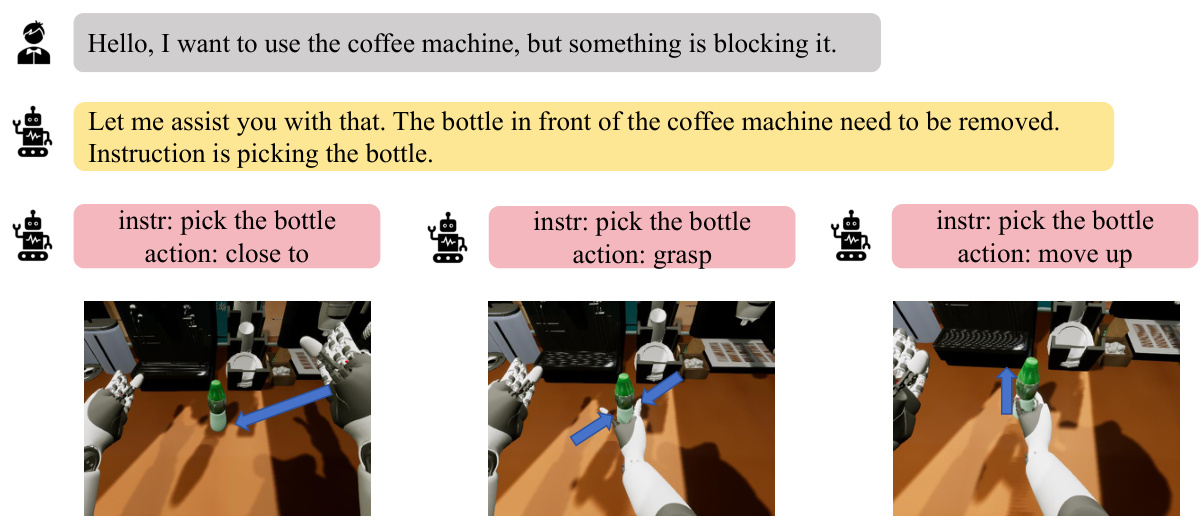

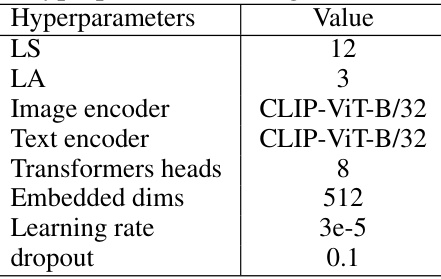

This table presents the results of experiments where additional human data was used to train the PIVOT-R model. It compares the model’s performance (success rate) on four different levels of tasks across various scenarios (seen, unseen backgrounds, changing lights, distractors). Three training methods are compared: original training (Origin), co-training (Co-Train), and pre-training (Pre-Train). The table shows that incorporating additional human data may improve model generalization in certain scenarios, although the co-training approach did not show significant improvements.

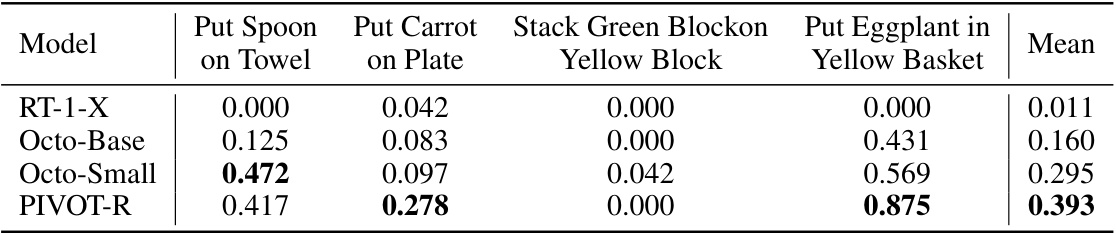

This table presents the success rate of four different models (RT-1-X, Octo-Base, Octo-Small, and PIVOT-R) on four subtasks within the SIMPLER benchmark. The benchmark is designed to be scalable, reproducible, and a reliable stand-in for real-world testing, focusing on tasks involving the manipulation of various objects (spoon, carrot, green block, eggplant). The results show the success rate for each model on each subtask, with the average success rate across all four tasks also provided. This data helps to evaluate the performance and generalization abilities of the models in a controlled environment.

Full paper#