TL;DR#

In-context learning, where models solve tasks based on input prompts without retraining, has been mainly explored with transformer models. However, the reliance on attention mechanisms limits the applicability of these findings to other architectures. This raises questions about the broader capabilities of other models, like fully recurrent neural networks, in performing this type of learning. This lack of understanding hinders the advancement of these architectures and the development of more efficient and interpretable AI systems.

This paper introduces Linear State Recurrent Language (LSRL), a programming language that compiles directly to fully recurrent architectures. Using LSRL, researchers successfully demonstrate that various fully recurrent networks, including RNNs, LSTMs, and GRUs, can also function as universal in-context approximators. The study also highlights the significance of multiplicative gating in improving the numerical stability of these models, making them more suitable for practical applications. The findings challenge existing assumptions about the capabilities of prompting and opens new research directions in the field of in-context learning and the development of alternative AI model architectures.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it expands the understanding of in-context learning beyond transformer models, a dominant paradigm in AI. It opens avenues for research into fully recurrent architectures, offering new possibilities for efficient and interpretable AI. The introduction of LSRL, a novel programming language, significantly aids in the analysis and development of these models.

Visual Insights#

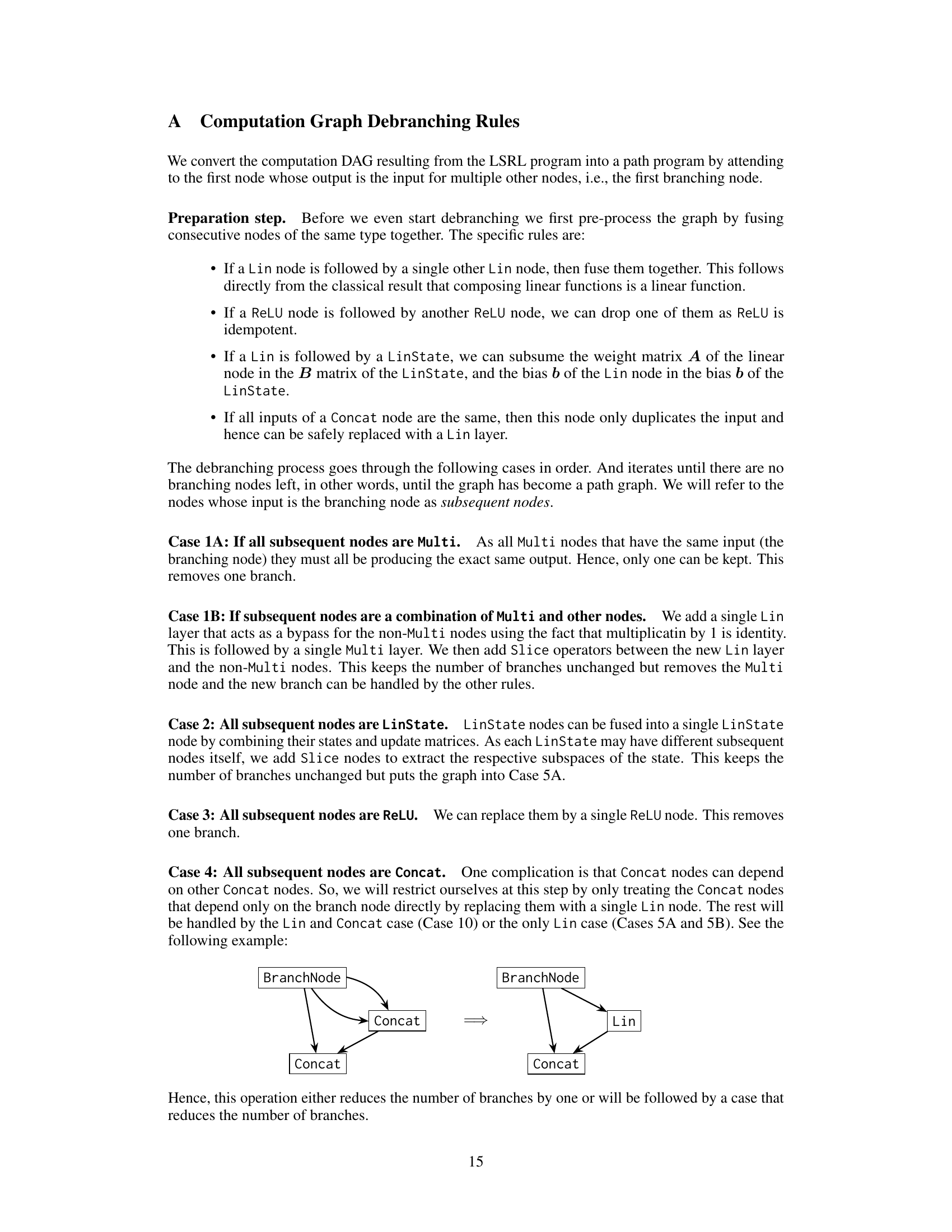

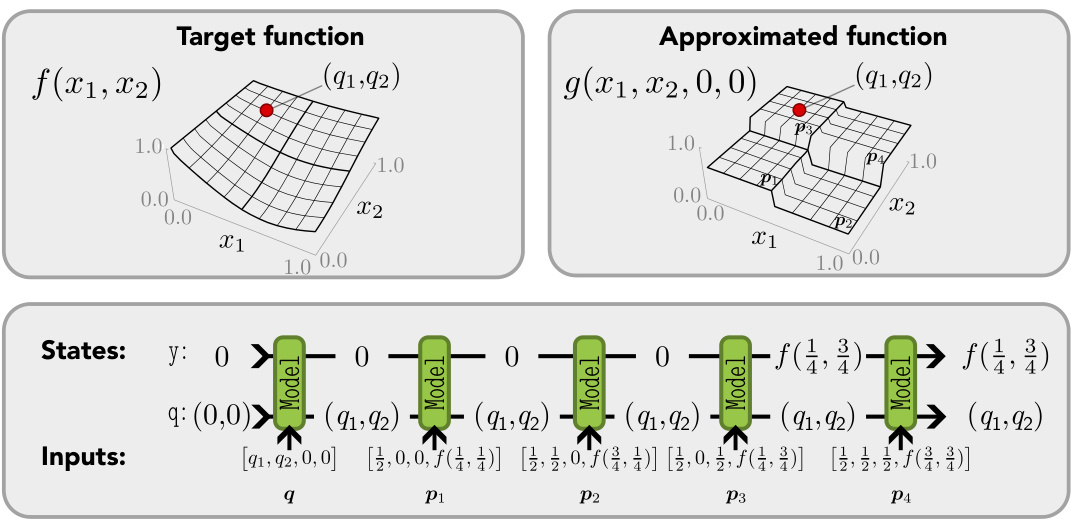

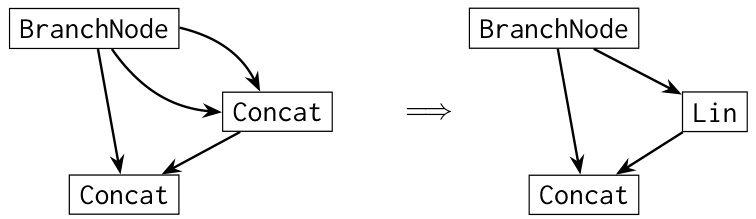

🔼 This figure demonstrates how a simple Linear State Recurrent Language (LSRL) program can be compiled into a Linear Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). The LSRL program checks if there are more 1s than 0s in the input sequence and outputs 1 if true, 0 otherwise. The compilation process simplifies the Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG) representation of the program into a linear path, which directly maps to a single-layer Linear RNN architecture. The figure visually illustrates the program’s structure, the transformation steps, and the resulting RNN with its node types (Input, Concat, ReLU, Linear, LinState).

read the caption

Figure 1: Compilation of an LSRL program to a Linear RNN. An example of a simple LSRL program that takes a sequence of 0s and 1s as an input and outputs 1 if there have been more 1s than 0s and 0 otherwise. The LSRL compiler follows the rules in App. A to simplify the computation DAG into a path graph. The resulting path graph can be represented as a Linear RNN with one layer.

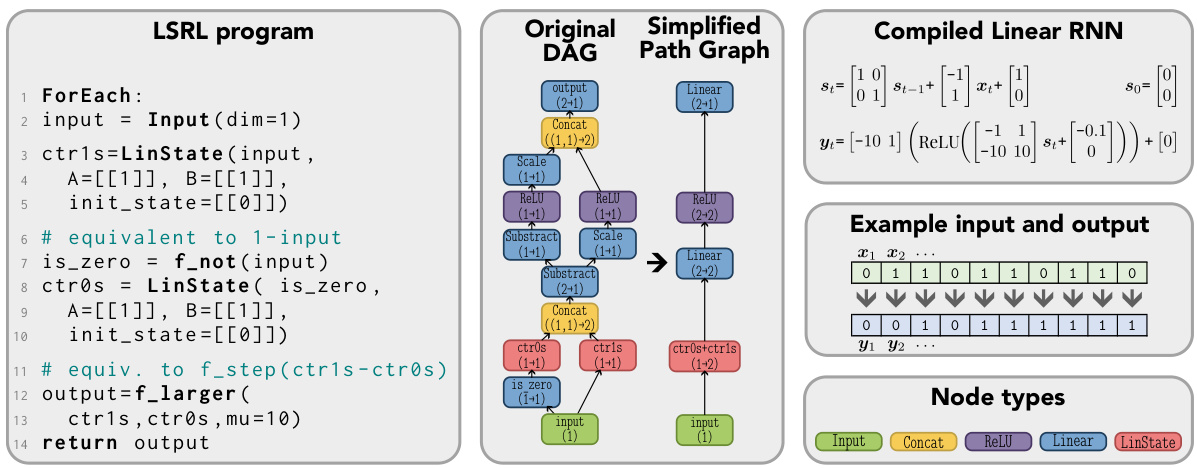

🔼 This figure illustrates the LSRL program’s operation for discrete function approximation. It uses a sequence of tokens representing countries and their capitals as input. The figure traces how the program’s internal variables change over time, highlighting the process of query matching and value retrieval to demonstrate the in-context approximation of the function.

read the caption

Figure 3: Intuition behind the LSRL program for universal in-context approximation for discrete functions in Lst. 2. Our keys and values have length n=3 and represent countries and capitals, e.g., AUStria→VIEnna, BULgaria→SOFia, and so on. The query is CAN for Canada and the final n outputs are OTT (Ottawa). We show the values of some of the variables in Lst. 2 at each step, with the LinState variables being marked with arrows. For cleaner presentation we are tokenizing letters as 0?, 1A, 2B, etc. Vertical separators are for illustration purposes only.

In-depth insights#

Universal Approximation#

The concept of “Universal Approximation” within the context of machine learning, and specifically deep learning models, is a crucial one. It essentially explores the capacity of a given model architecture, such as a neural network, to approximate any continuous function to a desired degree of accuracy, given sufficient training data and capacity. The paper investigates the universal approximation capabilities not of the standard deep learning models, but of fully recurrent models. This is significant because recurrent architectures, unlike transformers, do not inherently leverage attention mechanisms, traditionally considered key to in-context learning and universal approximation. The findings demonstrate that fully recurrent models, when appropriately prompted, achieve universal approximation, indicating that attention is not a necessary condition. This challenges existing assumptions and broadens the understanding of what capabilities are inherent in various model classes. The authors use a novel programming language, LSRL, to facilitate construction and analysis of recurrent models. The practical significance lies in the demonstration of in-context learning in architectures beyond transformers, which opens avenues for efficient and interpretable models. The use of LSRL streamlines this process, enabling further research into fully recurrent architectures and in-context learning behaviors. However, the study also identifies limitations, particularly regarding numerical stability of certain operations. This highlights ongoing challenges and research directions for making these powerful, yet potentially unstable, models reliable for real-world applications.

Recurrent Architectures#

Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs) and their variants, such as LSTMs and GRUs, are fundamental deep learning architectures known for their ability to process sequential data. Unlike feedforward networks, RNNs maintain an internal state that is updated at each time step, allowing them to capture temporal dependencies and context within sequences. LSTMs address the vanishing gradient problem often encountered in standard RNNs by employing sophisticated gating mechanisms to regulate the flow of information. GRUs simplify the LSTM architecture while retaining much of its effectiveness, offering a balance between complexity and performance. Recent research has explored the potential of linear RNNs (also called state-space models or SSMs) which offer advantages in scalability and training stability, though often requiring multiplicative gating for robust performance. These models, along with linear gated architectures like Mamba and Hawk/Griffin, demonstrate that fully recurrent architectures, despite lacking the attention mechanism of transformers, can effectively perform in-context learning and achieve universal approximation properties under the right conditions and prompt engineering.

LSRL Language#

The Linear State Recurrent Language (LSRL) is a novel programming language designed to bridge the gap between high-level programming and low-level recurrent neural network architectures. It offers a more intuitive and interpretable way to construct fully recurrent models, avoiding the complexities of manually specifying weights. By compiling LSRL programs into the weights of various recurrent architectures (RNNs, LSTMs, GRUs, Linear RNNs), LSRL simplifies the design and implementation of these models, enabling researchers to focus on the algorithmic aspects rather than intricate weight manipulation. The language’s syntax is designed to facilitate creating in-context learners and is particularly useful for studying in-context universal approximation capabilities of fully recurrent architectures. This approach promotes greater model interpretability by providing a higher-level abstraction compared to directly working with model weights. A significant advantage of LSRL lies in its ability to clearly demonstrate the role of multiplicative gating in enhancing numerical stability during computation, directly impacting the practical viability of fully recurrent models for real-world tasks. In essence, LSRL empowers researchers to explore the theoretical and practical limits of fully recurrent neural networks within a significantly more accessible and efficient framework.

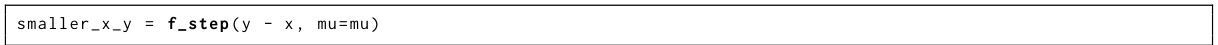

Gated Linear RNNs#

The section on ‘Gated Linear RNNs’ delves into a class of recurrent neural networks that combine the efficiency of linear RNNs with the power of gating mechanisms. This is significant because while linear RNNs offer advantages in training stability and scalability, they lack the expressiveness of their non-linear counterparts like LSTMs and GRUs. The authors explore how gating, specifically multiplicative gating, enhances the capabilities of linear RNNs, allowing them to more effectively approximate complex functions within the in-context learning paradigm. The analysis likely demonstrates that the addition of gating resolves numerical instability issues observed in simpler linear models, thus making them more practical candidates for real-world applications. Moreover, it probably establishes a theoretical link between gated linear RNNs and other architectures such as LSTMs and GRUs, highlighting the underlying mathematical relationships and potentially suggesting more efficient implementations. The discussion likely includes a detailed mathematical treatment of gating’s effect on model expressivity and stability, and possibly a comparison of their performance against related architectures in benchmark tasks.

Future Directions#

Future research could explore extending universal in-context approximation to other model architectures beyond fully recurrent networks. Investigating the impact of different activation functions and gating mechanisms on the stability and performance of these approximators is crucial. Developing more sophisticated programming languages like LSRL to design and analyze in-context learning algorithms within recurrent architectures would enhance our understanding. Improving the numerical stability of conditional operations, particularly in scenarios with high dimensional inputs, is essential for practical applications. Furthermore, research on the theoretical limits of in-context learning is warranted, including a deeper examination of the relationship between prompt length, model capacity, and approximation accuracy. Finally, exploring the implications of universal in-context approximation in areas like model safety, security and alignment will be vital.

More visual insights#

More on figures

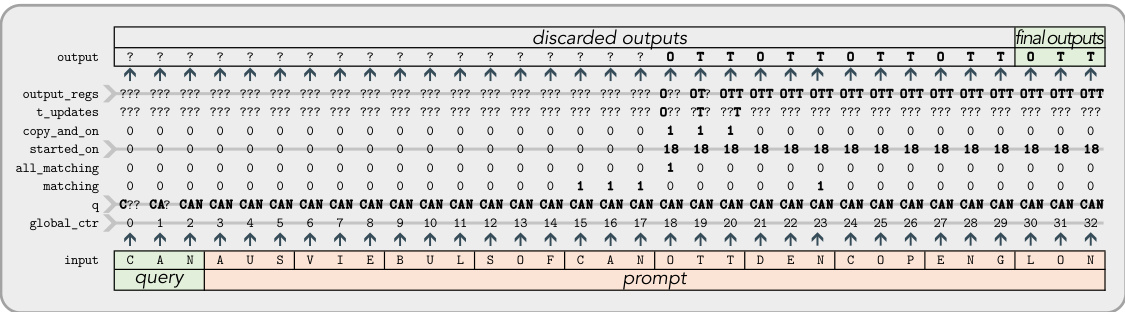

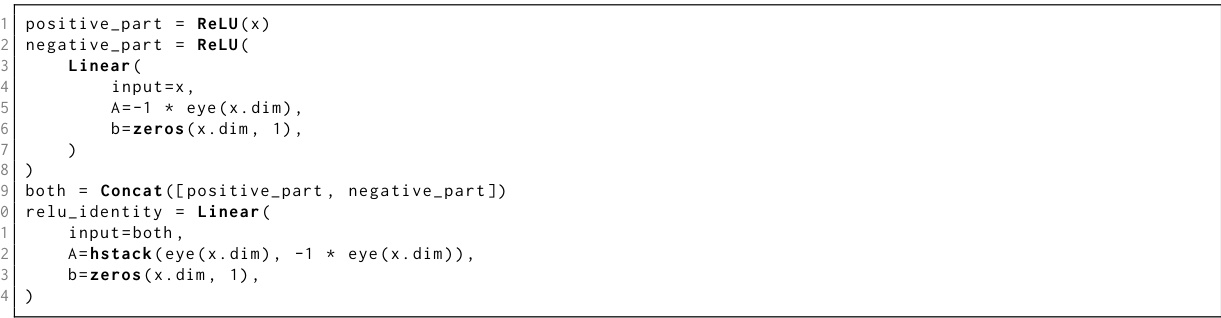

🔼 This figure shows how a simple LSRL program approximates a continuous function. The program discretizes the input space into cells and uses prompt tokens to represent the function’s value in each cell. The query is processed, and the program updates its internal state (LinState variables) based on whether the query falls within a cell and if so, adds the corresponding function value to the output state. The figure illustrates this process step-by-step for a 2D input, 1D output function.

read the caption

Figure 2: Intuition behind the LSRL program for universal in-context approximation for continuous functions in Lst. 1. Our target function f has input dimension din = 2 and output dimension dout = 1. Each input dimension is split into two parts, hence 8 = 1/2. We illustrated an example input sequence of length 5: one for the query and four for the prompt tokens corresponding to each of the discretisation cells. The query (q1, q2) falls in the cell corresponding to the third prompt token. We show how the two LinState variables in the program are updated after each step. Most notably, how the state holding the output y is updated after p3 is processed.

🔼 This figure illustrates how a simple LSRL program approximates a continuous 2D function. The input space is discretized into cells, and each cell’s function value is encoded in the prompt. The query is processed, and the program finds the cell containing the query, outputting the corresponding function value. The figure shows the state updates of the LinState variables in the program.

read the caption

Figure 2: Intuition behind the LSRL program for universal in-context approximation for continuous functions in Lst. 1. Our target function f has input dimension din = 2 and output dimension dout = 1. Each input dimension is split into two parts, hence 8 = 1/2. We illustrated an example input sequence of length 5: one for the query and four for the prompt tokens corresponding to each of the discretisation cells. The query (q1, q2) falls in the cell corresponding to the third prompt token. We show how the two LinState variables in the program are updated after each step. Most notably, how the state holding the output y is updated after p3 is processed.

🔼 This figure illustrates how the LSRL program (Listing 2) works for approximating discrete functions. The program receives a query (CAN for Canada) and a sequence of key-value pairs representing country-capital mappings. The figure demonstrates how the program updates its internal state variables to identify the correct key (CAN) in the prompt and output the corresponding value (OTT for Ottawa). The visualization simplifies token representation for clarity.

read the caption

Figure 3: Intuition behind the LSRL program for universal in-context approximation for discrete functions in Lst. 2. Our keys and values have length n=3 and represent countries and capitals, e.g., AUStria→VIEnna, BULgaria→SOFia, and so on. The query is CAN for Canada and the final n outputs are OTT (Ottawa). We show the values of some of the variables in Lst. 2 at each step, with the LinState variables being marked with arrows. For cleaner presentation we are tokenizing letters as 0?, 1A, 2B, etc. Vertical separators are for illustration purposes only.

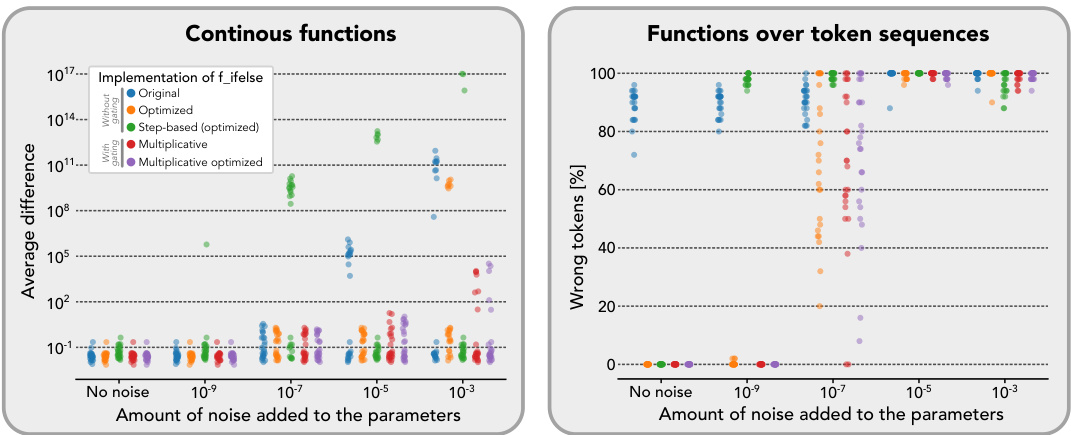

🔼 This figure shows the impact of adding Gaussian noise to the model parameters on the performance of different implementations of the conditional operator. The results indicate that the original implementation is highly sensitive to noise, while versions with multiplicative gates demonstrate significantly improved robustness. The performance is measured by the average difference from target function values for continuous function approximation and wrong tokens for functions on token sequences.

read the caption

Figure 4: Robustness of the various f_ifelse implementations to model parameter noise. We show how the performance of the two universal approximation programs in Lsts. 1 and 2 deteriorates as we add Gaussian noise of various magnitudes to the non-zero weights of the resulting compiled models. As expected, the original f_ifelse implementation in Eq. (7) exhibits numerical precision errors at the lowest noise magnitude. For the token sequence case, numerical precision errors are present in all samples even in the no-noise setting. Hence, the original f_ifelse implementation is less numerically robust while the implementations with multiplicative gating are the most robust. For Lst. 1 (approximating Cvec) we report the Euclidean distance between the target function value and the estimated one over 10 queries for 25 target functions. For Lst. 2 we report the percentage of wrong token predictions over 5 queries for 25 dictionary maps. Lower values are better in both cases.

🔼 This figure demonstrates how a simple Linear State Recurrent Language (LSRL) program is compiled into a Linear Recurrent Neural Network (RNN). The LSRL program is designed to take a sequence of binary inputs (0s and 1s) and output 1 if the cumulative sum of 1s exceeds the sum of 0s, and 0 otherwise. The figure shows the original directed acyclic graph (DAG) representation of the LSRL program, a simplified path graph version, and the equivalent one-layer Linear RNN. This illustrates the compiler’s role in transforming LSRL code into a recurrent neural network architecture.

read the caption

Figure 1: Compilation of an LSRL program to a Linear RNN. An example of a simple LSRL program that takes a sequence of 0s and 1s as an input and outputs 1 if there have been more 1s than 0s and 0 otherwise. The LSRL compiler follows the rules in App. A to simplify the computation DAG into a path graph. The resulting path graph can be represented as a Linear RNN with one layer.

🔼 This figure illustrates how the LSRL program for universal in-context approximation of continuous functions works. It shows a 2D input space discretized into cells, with each cell represented by a prompt token in the input sequence. A query point falls within one of the cells, and the program identifies the corresponding prompt token to determine the function’s output. The diagram tracks the changes in two internal LinState variables as the program processes the input sequence, highlighting how the output variable is updated.

read the caption

Figure 2: Intuition behind the LSRL program for universal in-context approximation for continuous functions in Lst. 1. Our target function f has input dimension din = 2 and output dimension dout = 1. Each input dimension is split into two parts, hence 8 = 1/2. We illustrated an example input sequence of length 5: one for the query and four for the prompt tokens corresponding to each of the discretisation cells. The query (q1, q2) falls in the cell corresponding to the third prompt token. We show how the two LinState variables in the program are updated after each step. Most notably, how the state holding the output y is updated after p3 is processed.

More on tables

🔼 This figure displays the robustness of different implementations of the conditional operator f_ifelse to parameter noise. It shows how the performance of universal approximation programs degrades as Gaussian noise is added to model parameters. The original f_ifelse is less robust than implementations with multiplicative gating, especially with low noise magnitudes. Results are shown for both continuous functions and functions over token sequences, with performance measured by Euclidean distance and wrong token percentage, respectively.

read the caption

Figure 4: Robustness of the various f_ifelse implementations to model parameter noise. We show how the performance of the two universal approximation programs in Lsts. 1 and 2 deteriorates as we add Gaussian noise of various magnitudes to the non-zero weights of the resulting compiled models. As expected, the original f_ifelse implementation in Eq. (7) exhibits numerical precision errors at the lowest noise magnitude. For the token sequence case, numerical precision errors are present in all samples even in the no-noise setting. Hence, the original f_ifelse implementation is less numerically robust while the implementations with multiplicative gating are the most robust. For Lst. 1 (approximating Cvec) we report the Euclidean distance between the target function value and the estimated one over 10 queries for 25 target functions. For Lst. 2 we report the percentage of wrong token predictions over 5 queries for 25 dictionary maps. Lower values are better in both cases.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of adding Gaussian noise to model parameters on the performance of two universal approximation programs. The original implementation of a conditional operator (f_ifelse) shows significant numerical instability, especially at low noise levels, while versions using multiplicative gating are more robust. The results are presented for both continuous functions and functions over token sequences, measuring the error differently for each.

read the caption

Figure 4: Robustness of the various f_ifelse implementations to model parameter noise. We show how the performance of the two universal approximation programs in Lsts. 1 and 2 deteriorates as we add Gaussian noise of various magnitudes to the non-zero weights of the resulting compiled models. As expected, the original f_ifelse implementation in Eq. (7) exhibits numerical precision errors at the lowest noise magnitude. For the token sequence case, numerical precision errors are present in all samples even in the no-noise setting. Hence, the original f_ifelse implementation is less numerically robust while the implementations with multiplicative gating are the most robust. For Lst. 1 (approximating Cvec ) we report the Euclidean distance between the target function value and the estimated one over 10 queries for 25 target functions. For Lst. 2 we report the percentage of wrong token predictions over 5 queries for 25 dictionary maps. Lower values are better in both cases.

🔼 This figure displays the robustness experiments of different implementations of the f_ifelse function against parameter noise. The experiments test two universal approximation programs (from Listings 1 and 2) using continuous functions and token sequences as inputs. The results, displayed as plots, show how different implementations of the f_ifelse functions (original, optimized, step-based, and multiplicative) degrade under different levels of Gaussian noise added to model parameters. It demonstrates the superior numerical stability of the multiplicative gating versions of the conditional operator.

read the caption

Figure 4: Robustness of the various f_ifelse implementations to model parameter noise. We show how the performance of the two universal approximation programs in Lsts. 1 and 2 deteriorates as we add Gaussian noise of various magnitudes to the non-zero weights of the resulting compiled models. As expected, the original f_ifelse implementation in Eq. (7) exhibits numerical precision errors at the lowest noise magnitude. For the token sequence case, numerical precision errors are present in all samples even in the no-noise setting. Hence, the original f_ifelse implementation is less numerically robust while the implementations with multiplicative gating are the most robust. For Lst. 1 (approximating Cvec) we report the Euclidean distance between the target function value and the estimated one over 10 queries for 25 target functions. For Lst. 2 we report the percentage of wrong token predictions over 5 queries for 25 dictionary maps. Lower values are better in both cases.

Full paper#