TL;DR#

Training large language models usually requires massive amounts of data, which often contains sensitive information. Differential privacy (DP) is a technique to protect private data during model training, but applying DP during the initial pre-training stage usually leads to significant performance degradation. This limits the applicability of DP in protecting the large amount of data used in the pre-training phase.

This paper proposes a novel DP continual pre-training strategy to address this issue. The strategy leverages a small amount of public data to mitigate the performance drop caused by DP noise during the pre-training stage, followed by a private continual pre-training phase. Experiments demonstrate that this strategy achieves high accuracy on downstream tasks, outperforming existing DP pre-trained models and being comparable to non-DP pre-trained models.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in differential privacy and machine learning. It addresses the critical challenge of pre-training large models with privacy concerns, offering a novel and effective approach using a small amount of public data. This significantly improves the accuracy and efficiency of differentially private models, opening new avenues for research in privacy-preserving AI and large language models. The proposed DP continual pre-training strategy is easily implementable and has the potential to change the landscape of private AI development.

Visual Insights#

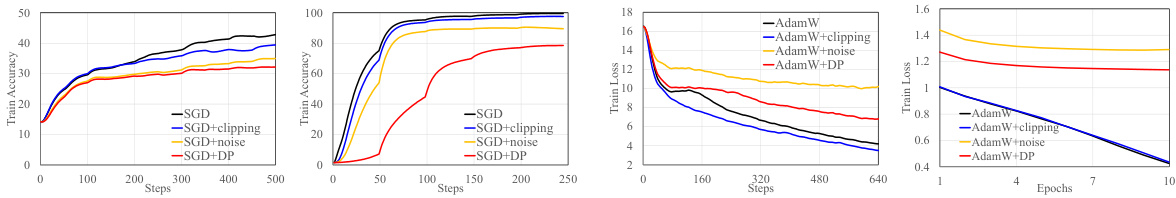

🔼 This figure compares the convergence behavior of different optimization methods across various tasks and training stages. It showcases standard SGD, SGD with gradient clipping, SGD with added noise, and DP-SGD (Differentially Private Stochastic Gradient Descent). The results are shown for both pre-training and fine-tuning phases in different tasks. It illustrates how these methods affect training loss and accuracy over training steps or epochs, providing insights into their efficiency and the impact of differential privacy mechanisms.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison among the convergence of standard SGD, clipped SGD without noise, noisy SGD without clipping, and DP-SGD in different tasks and training stages.

🔼 This table summarizes the key differences between differentially private (DP) pre-training and DP fine-tuning. It highlights that pre-training uses a large dataset and many training iterations, with DP noising being the main cause of performance degradation. In contrast, DP fine-tuning uses a small dataset and fewer iterations, with DP clipping being the primary source of performance issues. The table provides context for the authors’ focus on addressing the challenges associated with DP pre-training.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparing DP pre-training and DP fine-tuning.

In-depth insights#

DP Pre-training#

Differentially Private (DP) pre-training tackles the challenge of training large language models on sensitive data while preserving privacy. The core idea is to incorporate DP mechanisms during the initial pre-training phase, rather than solely focusing on the fine-tuning stage, as is commonly done. This is crucial because pre-training datasets often contain sensitive information. A key finding is that the performance degradation often associated with DP pre-training can be significantly mitigated by incorporating a small amount of public data. This leads to a novel continual pre-training strategy where initial training uses non-private public data, and then transitions to private data leveraging DP mechanisms. This approach achieves accuracy comparable to standard non-private methods on various downstream tasks while offering strong privacy guarantees. The research introduces a theoretical analysis based on Hessian matrices to better understand the effects of DP optimization, revealing insights into the dynamics of per-iteration loss improvement and the role of public data in mitigating DP’s performance limitations. Empirical results demonstrate that the combined strategy surpasses existing DP pre-trained models in accuracy and data efficiency.

Hessian Analysis#

The Hessian analysis section of the research paper likely delves into the use of Hessian matrices to understand the optimization landscape of differentially private (DP) models. The Hessian, a matrix of second-order partial derivatives, provides insights into the curvature of the loss function. This is crucial for analyzing the impact of DP mechanisms (noise addition and gradient clipping) on the convergence of DP training. The authors likely use the Hessian to theoretically explain the challenges in DP pre-training versus DP fine-tuning, which is often more successful. Specifically, the analysis probably demonstrates how the Hessian’s properties (e.g., its trace, eigenvalues, condition number) are affected by DP noise and clipping, leading to slower convergence in the pre-training phase. By analyzing per-iteration loss improvement through the lens of Hessian, the authors may offer a deeper understanding of DP optimization dynamics and provide theoretical justifications for their novel continual pre-training strategy. Key insights may involve identifying an optimal batch size based on Hessian characteristics and linking Hessian properties to downstream task performance. Overall, this section is vital for grounding the paper’s empirical findings in theory and for providing a more rigorous understanding of the impact of DP on model training.

Public Data Use#

The utilization of public data in differentially private (DP) model training is a crucial aspect, significantly impacting the effectiveness and practicality of the approach. A key finding is that the negative effects of DP noise on model training can be substantially mitigated by leveraging a limited amount of public data, acting as a strong non-private initializer. This strategy allows DP training to proceed efficiently with privacy guarantees, improving accuracy and potentially achieving performance levels comparable to non-DP counterparts. The analysis suggests that the initial phase of non-private pre-training, using public data, helps overcome the slow convergence often associated with DP training, highlighting the value of a hybrid approach. The effectiveness of this strategy indicates that carefully balancing private and public data is key for successfully deploying DP models, especially in situations where acquiring substantial private data is difficult or impossible. Future research should focus on optimizing the ratio of private to public data for various model architectures and downstream applications. Additionally, exploring different types of public data and their impact on the privacy-utility tradeoff will be beneficial in refining this promising approach.

DP Optimizer#

Differentially private (DP) optimizers are crucial for training machine learning models while preserving data privacy. They introduce noise or other mechanisms to the training process to limit the amount of information revealed about individual data points. The choice of DP optimizer significantly impacts the trade-off between model accuracy and privacy. Common DP optimizers include variations of stochastic gradient descent (SGD) and Adam, each with different strengths and weaknesses concerning convergence speed and privacy guarantees. Understanding the effect of different hyperparameters like noise scale and clipping bounds on both training efficiency and the privacy-utility trade-off is vital. The analysis of DP optimizers often involves complex mathematical frameworks like Renyi differential privacy, allowing researchers to quantify the privacy level achieved. Research focuses on developing optimizers that are both privacy-preserving and computationally efficient, particularly for large-scale models. The field is actively exploring novel techniques such as continual pre-training with limited public data, to improve the accuracy of DP models while maintaining privacy guarantees. This is a critical area of ongoing research, as the balance between the need for effective machine learning and robust data protection necessitates innovative DP optimization strategies.

Future of DP#

The “Future of DP” hinges on addressing its current limitations. Computational efficiency remains a major hurdle, especially for large models and datasets. Privacy-preserving techniques need further development to minimize the trade-off between privacy and utility. Theoretical advancements are crucial for developing tighter bounds and understanding the behavior of DP mechanisms in complex settings. Practical applications will drive progress, pushing for efficient and effective implementations across diverse domains. Standardization and tooling will improve usability and adoption, while robust privacy accounting methods are essential for reliable privacy guarantees. Ultimately, a stronger focus on user privacy and explainability of DP systems is needed to achieve widespread trust and acceptance.

More visual insights#

More on figures

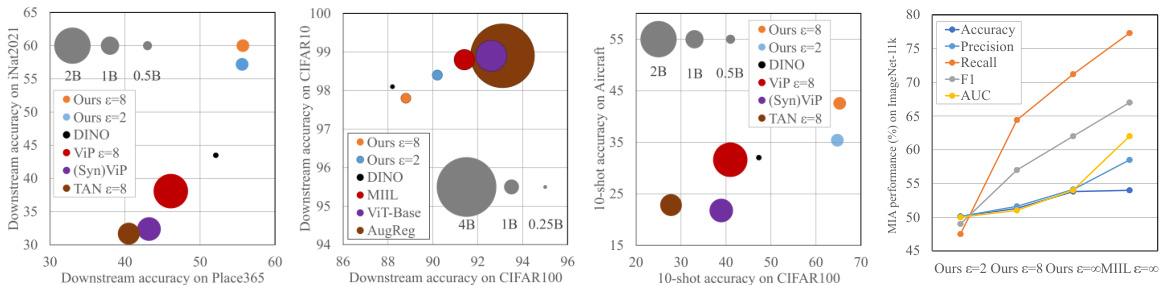

🔼 This figure summarizes the results presented in Section 5 of the paper. It consists of four subfigures. The first three subfigures compare the performance of differentially private (DP) pre-trained models against other state-of-the-art models on various downstream tasks (ImageNet-11k, CIFAR-10, Places365, iNat2021, and Aircraft). The size of the circles in these subfigures represents the amount of data used for pre-training, illustrating data efficiency. The fourth subfigure shows the performance of DP models in resisting membership inference attacks (MIA), a common privacy attack, with lower MIA scores indicating stronger privacy protection.

read the caption

Figure 2: Summary of results in Section 5. First three figures compare the downstream and few-shot performance and the data efficiency (circle's radius proportional to pre-training data size) of the DP pre-trained models; the last figure shows the performance of DP pre-trained models defending against privacy attacks (lower is stronger in defense).

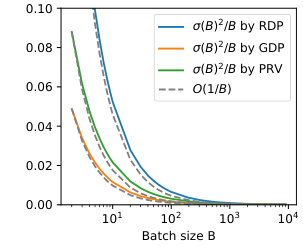

🔼 This figure shows the relationship between batch size (B) and the noise level (σ(B)²/B) for three different privacy accounting methods: RDP, GDP, and PRV. The dashed line represents the theoretical O(1/B) relationship. The graph illustrates how the noise level decreases as the batch size increases, and it shows that the different privacy accounting methods have different noise levels at various batch sizes. This information is crucial for understanding how to set the privacy parameters in differentially private training.

read the caption

Figure 3: Noise levels by privacy accountants.

🔼 This figure illustrates the different clipping functions used in the paper. The x-axis represents the per-sample gradient norm, and the y-axis represents the clipping factor (Ci). The figure shows the behavior of five different clipping functions: AUTO-V, AUTO-S, and three versions of re-parameterized clipping with different sensitivity bounds (R=0.1, R=0.2, R=1). The figure is important because it visually demonstrates how the different clipping functions affect the magnitude of the gradients before they are used in the differentially private optimization process. Different clipping methods impact the convergence of the algorithm in various ways. This figure is crucial for understanding and comparing the different clipping techniques used within the context of differentially private optimization.

read the caption

Figure 4: Per-sample gradient clipping in (3).

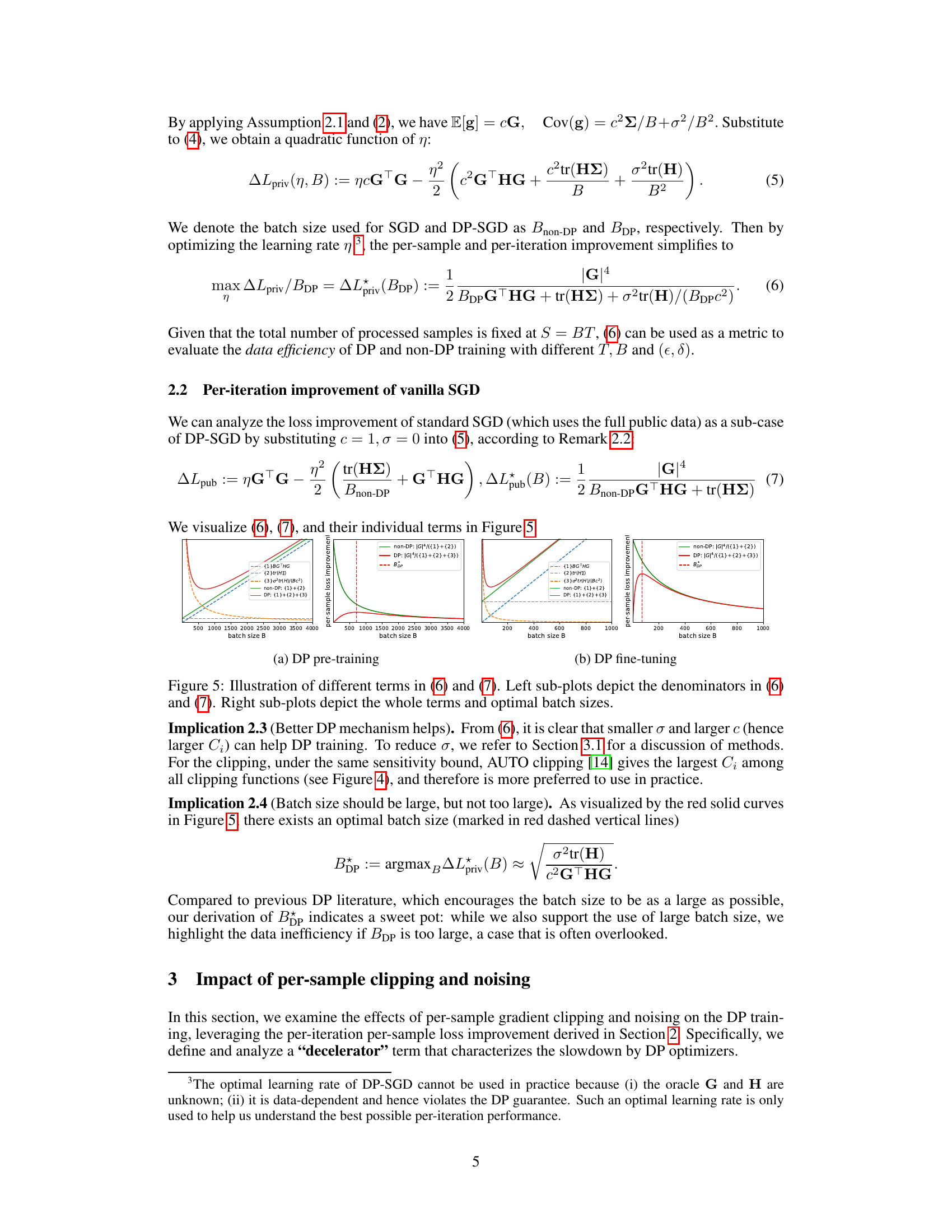

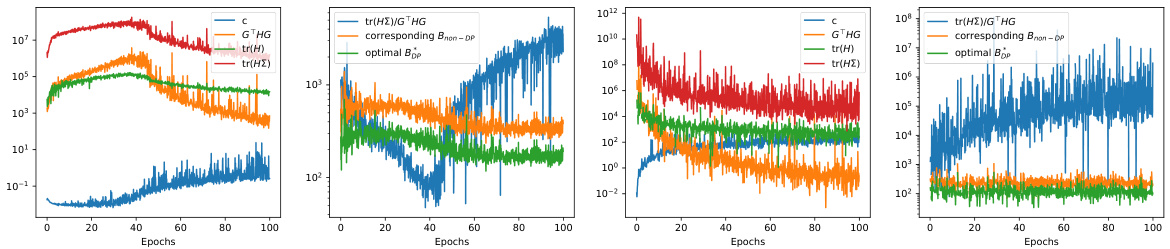

🔼 This figure visualizes the different terms of equations (6) and (7) from the paper, which describe the per-sample loss improvement for DP-SGD and standard SGD, respectively. The left subplots show the denominators of these equations, illustrating how they vary with the batch size (B). The right subplots show the complete per-sample loss improvement calculations, including the optimal batch size (Bop) for each method. The figure helps to visually understand the impact of different terms in the equations on the overall loss improvement, particularly the effect of DP noise and batch size on the rate of convergence.

read the caption

Figure 5: Illustration of different terms in (6) and (7). Left sub-plots depict the denominators in (6) and (7). Right sub-plots depict the whole terms and optimal batch sizes.

🔼 This figure illustrates the different terms of equations (6) and (7) which represent the per-sample loss improvement for DP-SGD and standard SGD. The left subplots show the denominators of the equations, highlighting the impact of different components like Hessian, covariance and noise. The right subplots show the overall per-sample loss improvement with varying batch size, indicating the existence of an optimal batch size that balances noise and convergence speed in DP training.

read the caption

Figure 5: Illustration of different terms in (6) and (7). Left sub-plots depict the denominators in (6) and (7). Right sub-plots depict the whole terms and optimal batch sizes.

🔼 This figure shows the test loss curves for GPT2-small trained on CodeParrot dataset using different pre-training strategies with epsilon=8. The strategies compared are: * Fully Public: Standard training without any differential privacy (DP). * Fully Private: Training with DP applied to the entire dataset. * Only Public: Training only on public data without DP. * Mixed (PubRatio=1%): Training with DP, using 1% public data. * Mixed (PubRatio=10%): Training with DP, using 10% public data. The plot also indicates the ‘SwitchPoint’ - the point at which the model switches from public to private training. The results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed DP continual pre-training strategy.

read the caption

Figure 7: Convergence of GPT2-small on CodeParrot with different pre-training strategies (€ = 8).

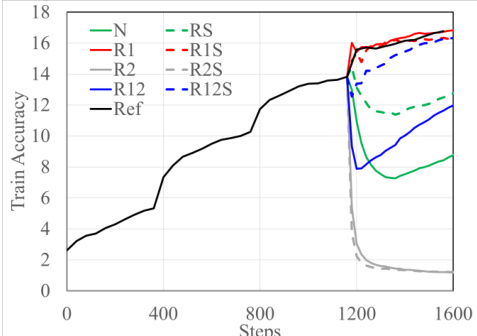

🔼 This figure shows the ablation study result of different strategies of re-initializing the AdamW optimizer states during the training stage switching. The experiment uses ViT-Base model trained from scratch on CIFAR100 dataset. During the first three epochs, it trains with vanilla AdamW, then switches to DP-AdamW and continues for another one epoch. During switching, the learning rate is fixed, and different states are reset to zeros. The graph plots the training accuracy against the steps. It indicates that re-initializing the first-order momentum m (R1) is the best strategy to achieve high performance when switching from public to private training.

read the caption

Figure 8: Ablation study of switching from non-DP to DP training with AdamW on CIFAR100 dataset. When switching (T = 1200), we re-initialize different states in the AdamW optimizer in different linestyles. “R1”, “R2”, and “RS” indicate m, v and t are re-initialized, respectively. “N” indicates no re-initialization, and “Ref” is the reference behavior of continual training with non-DP AdamW.

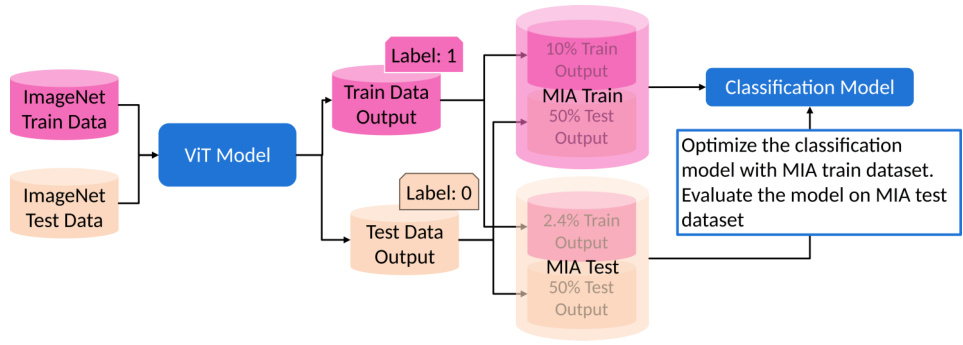

🔼 The figure illustrates the process of a membership inference attack (MIA). ImageNet train and test data are fed into a ViT model. The model’s outputs (logits and loss) for both training and test data are then used to create an MIA train and test dataset. This dataset consists of 10% of the training data and 50% of the test data labeled as ‘1’ (member), and 2.4% of the training data and 50% of the test data labeled as ‘0’ (non-member). A classification model is trained on this MIA dataset to determine whether an image is from the original ImageNet training set or not. The accuracy of this classification model serves as a measure of the privacy protection afforded by the system.

read the caption

Figure 9: The process of membership inference attack (MIA).

More on tables

🔼 This table summarizes the different methods for determining the ratio of privatized and non-privatized gradients (αt) in mixed data training. The methods shown are ‘Ours’ (a piecewise function indicating a switch between public and private training), ‘DPMD’ (a cosine function), ‘Sample’ (a ratio based on the number of public and private samples), ‘OnlyPublic’ (αt = 1, only public data), and ‘OnlyPrivate’ (αt = 0, only private data). Each method offers a different strategy for balancing the use of public and private data during training.

read the caption

Table 2: Summary of αt by mixed data training methods.

🔼 This table compares different pre-training strategies used by various models in the paper. It shows whether the models were trained using standard non-DP methods (black) or DP methods (green). The self-supervised methods are indicated by a †. The number of images used in pre-training is given, noting where the pre-training wasn’t fully private.

read the caption

Table 3: Pre-training strategies of models. Standard non-DP training is marked in black; DP training is in green. † indicates self-supervised without using the labels. “Images ×” is the total number of images used (dataset size × epochs). “Non-privacy” means no DP guarantee on a subset of training data due to the non-DP pre-training phase.

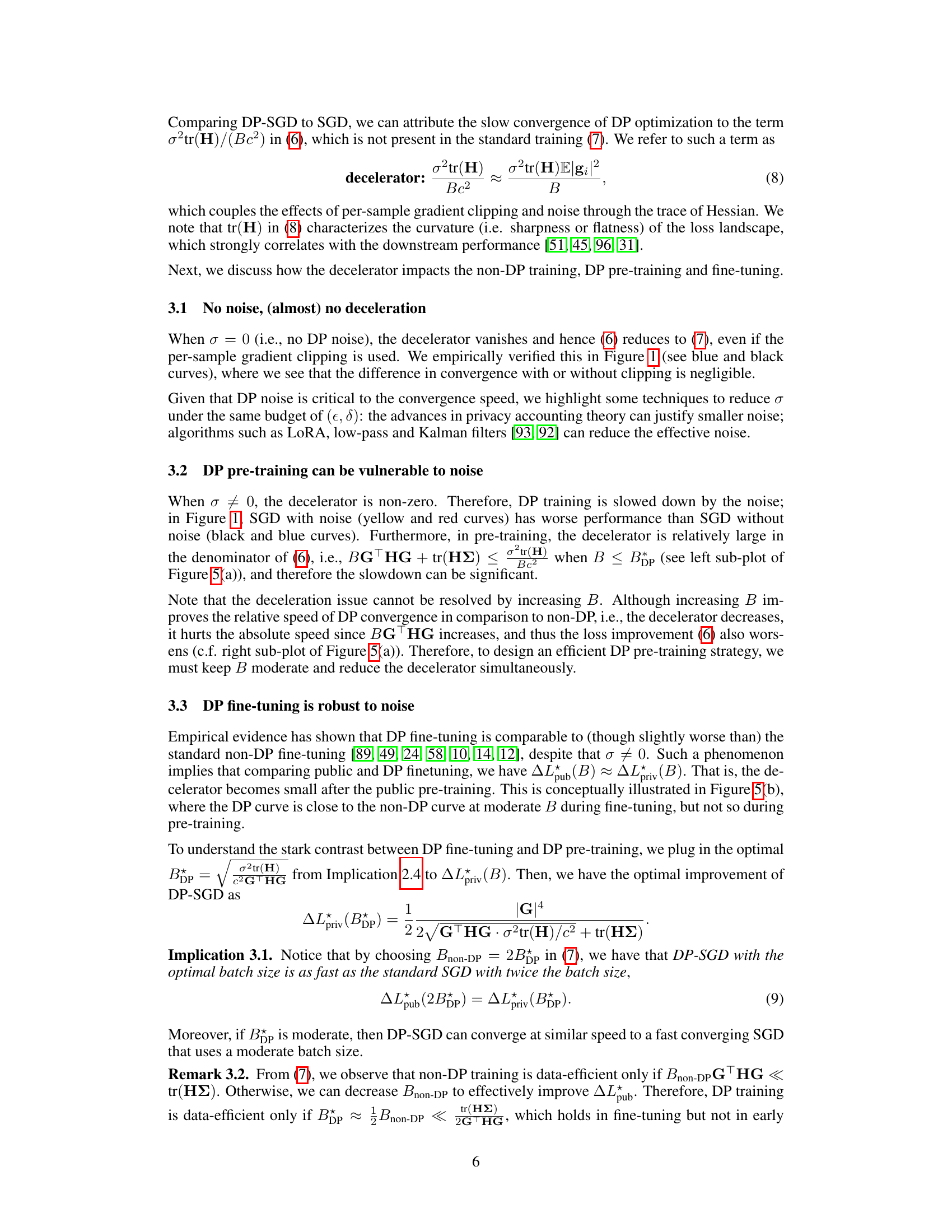

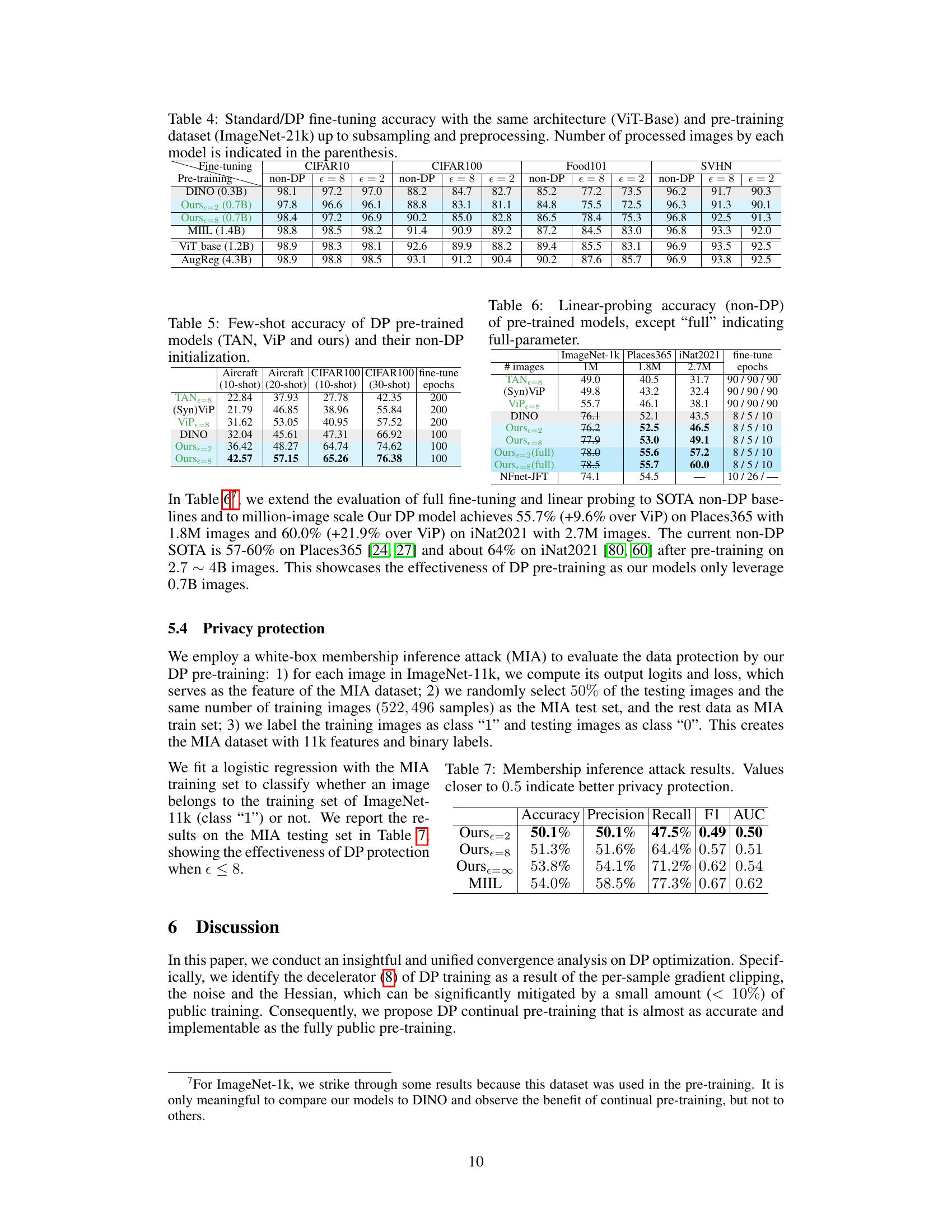

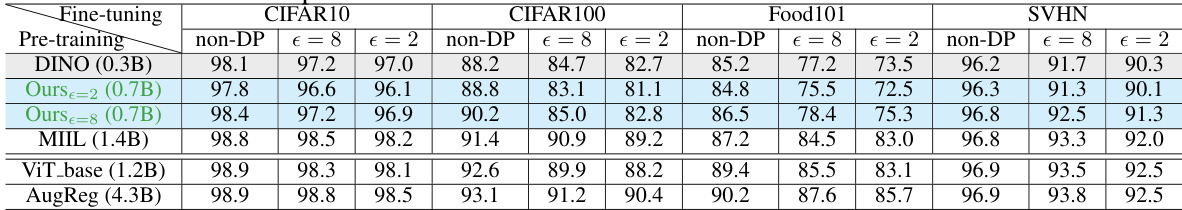

🔼 This table compares the fine-tuning accuracy of different models on four datasets (CIFAR10, CIFAR100, Food101, and SVHN) under standard and differentially private (DP) settings. The pre-training dataset used is ImageNet-21k for all models. The number of processed images during pre-training is also shown. The table showcases the performance of the proposed DP continual pre-training method compared to other state-of-the-art methods. The different epsilon values (ε) for DP training demonstrate the trade-off between privacy and accuracy.

read the caption

Table 4: Standard/DP fine-tuning accuracy with the same architecture (ViT-Base) and pre-training dataset (ImageNet-21k) up to subsampling and preprocessing. Number of processed images by each model is indicated in the parenthesis.

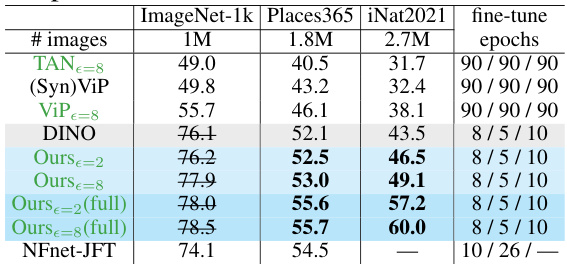

🔼 This table presents the few-shot accuracy results on several downstream tasks for three different differentially private (DP) pre-trained models: TAN, ViP, and the authors’ model. For each model, results are shown for both DP and non-DP initialization methods, and different few-shot settings (10-shot and 20-shot for Aircraft, and 10-shot and 30-shot for CIFAR100) are included.

read the caption

Table 5: Few-shot accuracy of DP pre-trained models (TAN, ViP and ours) and their non-DP initialization.

🔼 This table compares the linear probing accuracy (non-DP) of several pre-trained models on three downstream tasks: Aircraft (10-shot and 20-shot), CIFAR100 (10-shot and 30-shot), and Places365. It shows the performance of models like TAN, ViP, DINO, and the authors’ model (with different epsilon values and with/without full parameter tuning), highlighting the effectiveness of the proposed DP continual pre-training strategy.

read the caption

Table 6: Linear-probing accuracy (non-DP) of pre-trained models, except 'full' indicating full-parameter.

🔼 This table presents the results of a membership inference attack (MIA) to evaluate the privacy protection offered by the proposed differentially private (DP) pre-training methods. The metrics shown are accuracy, precision, recall, F1-score, and AUC, each measuring a different aspect of the model’s ability to prevent inference of training data membership. Values closer to 0.5 indicate stronger privacy protection, as a perfect classifier would achieve 0.5 AUC (random guessing). The results are compared to MIIL, a state-of-the-art non-DP model, demonstrating the effectiveness of the DP approach at epsilon values of 2 and 8.

read the caption

Table 7: Membership inference attack results. Values closer to 0.5 indicate better privacy protection.

🔼 This table compares different pre-training strategies used in various models. It indicates whether the model used differential privacy (DP) during pre-training and provides the dataset used and the number of images processed. It also notes if there was any non-private data used in the pre-training stage.

read the caption

Table 3: Pre-training strategies of models. Standard non-DP training is marked in black; DP training is in green. † indicates self-supervised without using the labels. “Images ×” is the total number of images used (dataset size × epochs). “Non-privacy” means no DP guarantee on a subset of training data due to the non-DP pre-training phase.

🔼 This table compares different pre-training strategies used to train vision transformer models. It highlights whether the training was differentially private (DP) or not, the type of self-supervised learning used, and the total number of images used in the training process. It also notes if there was a non-private phase in the pre-training.

read the caption

Table 3: Pre-training strategies of models. Standard non-DP training is marked in black; DP training is in green. † indicates self-supervised without using the labels. “Images ×” is the total number of images used (dataset size × epochs). “Non-privacy” means no DP guarantee on a subset of training data due to the non-DP pre-training phase.

Full paper#