TL;DR#

Phylogenetic tree inference, crucial for understanding evolutionary relationships, faces challenges due to the complexity of combining continuous (branch lengths) and discrete parameters (tree topology). Traditional methods struggle with slow convergence and computational costs, while existing variational inference approaches often overlook critical sequence features.

PhyloGen tackles these issues by leveraging a pre-trained genomic language model to directly generate and optimize phylogenetic trees without relying on evolutionary models or sequence alignment. This innovative approach jointly optimizes tree topology and branch lengths, demonstrating improved accuracy and efficiency on multiple benchmark datasets. The use of a language model allows PhyloGen to extract richer information from raw sequences than previous methods. This is an important advancement for phylogenetics, making it easier to study complex evolutionary relationships, particularly in clinical and virological applications where rapid and precise analyses are crucial. PhyloGen’s end-to-end approach eliminates the need for evolutionary models and sequence alignment, providing improved flexibility and robustness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is important because it presents a novel approach to phylogenetic inference that is faster and more accurate than traditional methods. It uses a pre-trained language model to generate and optimize phylogenetic trees, eliminating the need for evolutionary models or aligned sequence constraints. This opens up new avenues for research in phylogenetics and related fields, especially for analyzing large datasets and complex evolutionary relationships. The model’s robustness and efficiency make it a valuable tool for researchers, particularly in clinical applications and evolutionary biology.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure compares three different approaches for phylogenetic tree inference: (a) Tree Representation Learning uses pre-generated trees and focuses on learning topology from existing structures. (b) Existing Tree Structure Generation methods independently infer topology and branch lengths from aligned sequences. (c) PhyloGen (the authors’ method) leverages a language model to generate and jointly optimize both topology and branch lengths directly from raw sequences without alignment.

read the caption

Figure 1: Comparison of PhyloTree Tree Inference Methods. (a) The inputs are aligned sequences, and topologies are learned from existing tree structures using methods like SBNs, which rely on MCMC-based methods for pre-generated candidate trees without considering branch lengths directly. (b) The inputs are aligned sequences, and then tree structures and branch lengths are directly inferred by variational inference and biological modules. These methods optimize tree topology and branch lengths separately. (c) The inputs are raw sequences processed by a pre-trained language model to generate species representations. Then, an initial topology is generated through a tree construction module, and the topology and branch lengths are co-optimized by the tree structure modeling module.

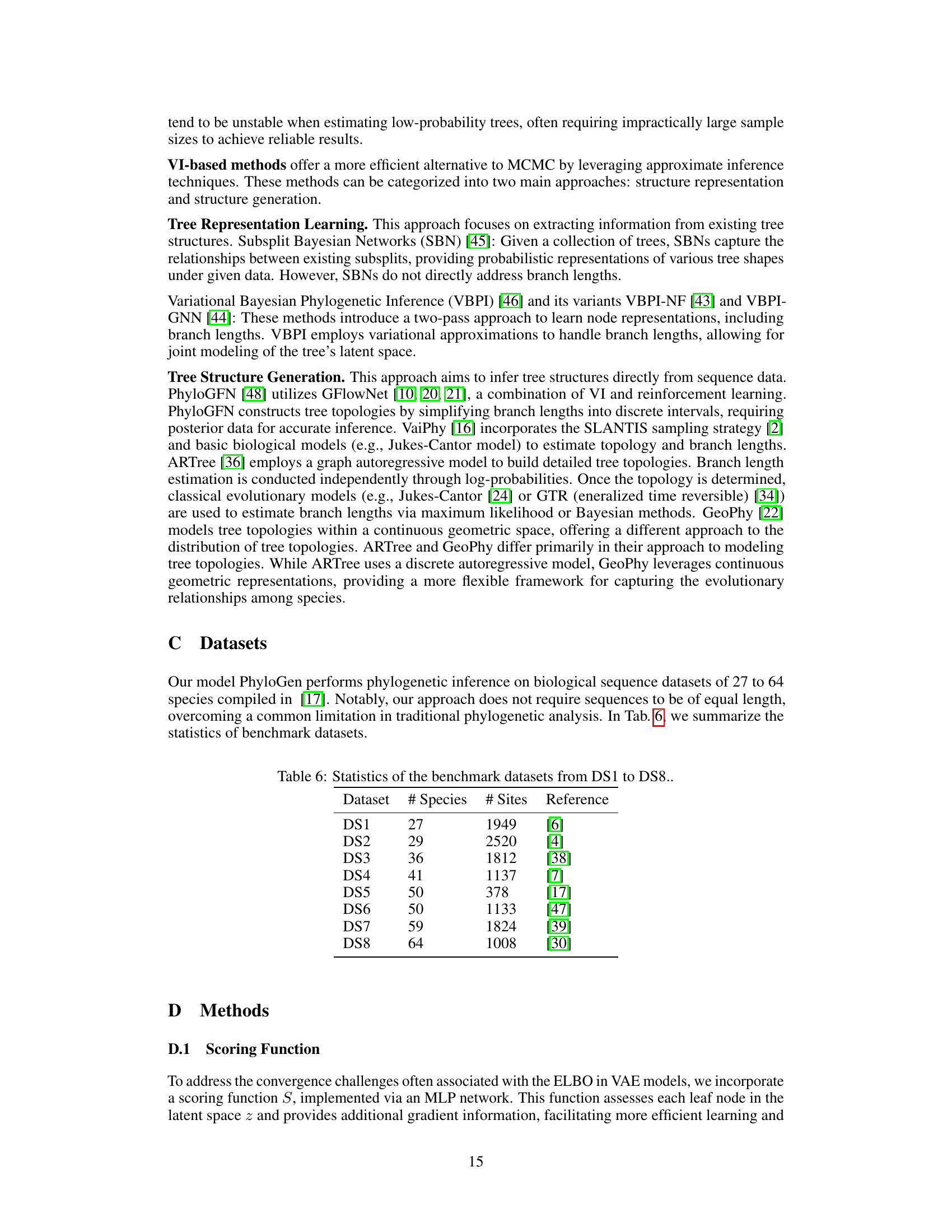

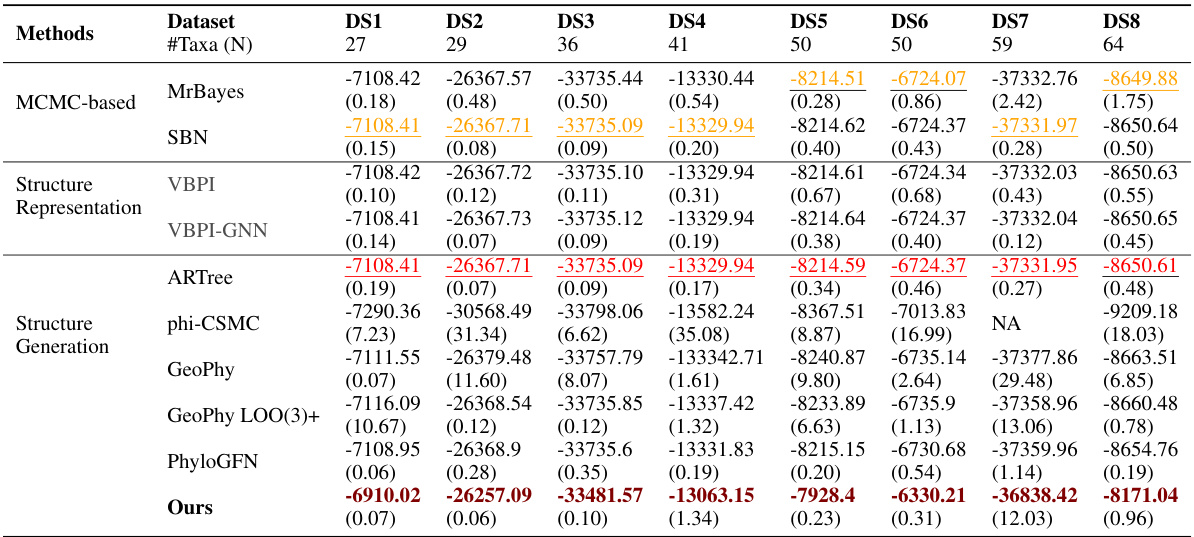

🔼 This table compares the performance of various phylogenetic inference methods on eight benchmark datasets, measured by Marginal Log-Likelihood (MLL). It shows the MLL scores for different methods, categorized as MCMC-based, Structure Representation, and Structure Generation. The best performing method for each dataset is highlighted in bold. The table also highlights that VBPI and VBPI-GNN are not directly comparable to other methods because they use pre-generated topologies.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the MLL (↑) with different approaches in eight benchmark datasets. VBPI and VBPI-GNN use pre-generated tree topologies in training and thus are not directly comparable. Boldface for the highest result, underline for the second highest from traditional methods, and underline for the second highest from tree structure generation methods.

In-depth insights#

PhyloGen: Overview#

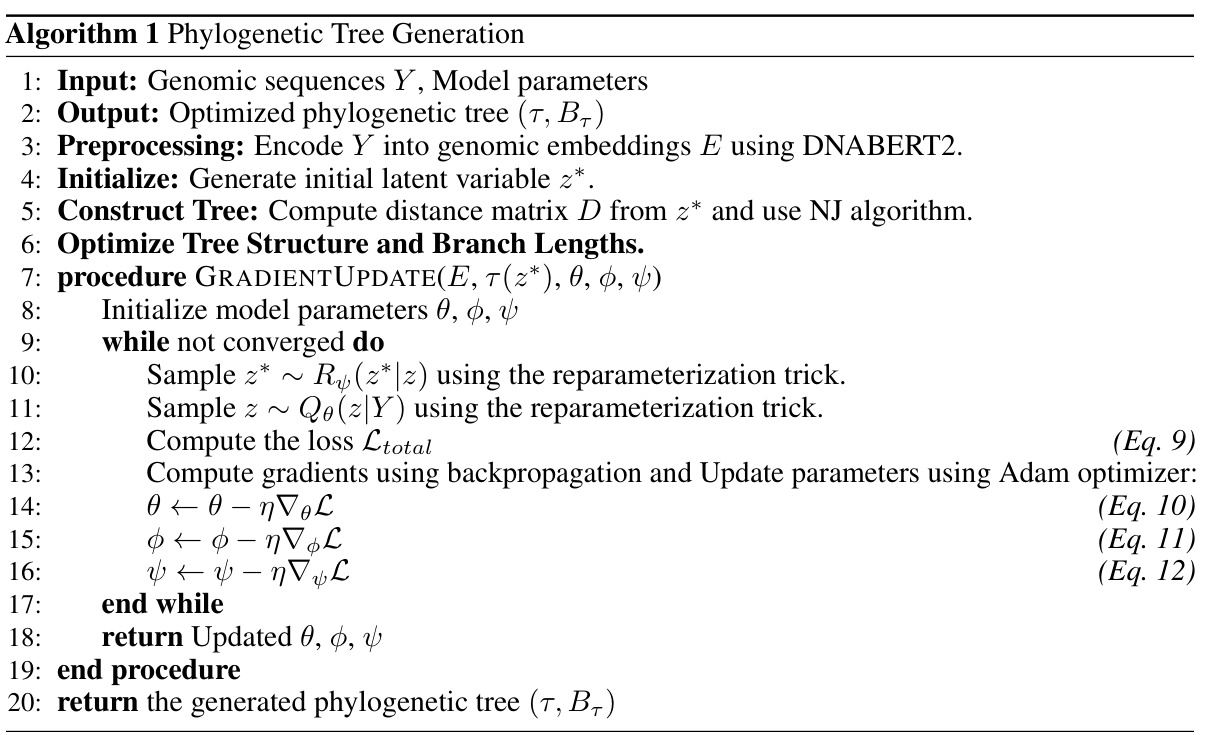

PhyloGen offers a novel approach to phylogenetic inference, moving beyond traditional limitations of MCMC and existing VI methods. It leverages a pre-trained genomic language model to generate and optimize phylogenetic trees, eliminating the need for evolutionary models or aligned sequence constraints. This innovative method views phylogenetic inference as a conditionally constrained tree structure generation problem. By jointly optimizing topology and branch lengths, PhyloGen promises to provide more accurate and robust phylogenetic analyses, particularly when dealing with complex evolutionary relationships and diverse biological sequences. The method’s core lies in its three modules: Feature Extraction, PhyloTree Construction, and PhyloTree Structure Modeling. The unique combination of these modules with the pre-trained language model positions PhyloGen as a significant advancement in the field, potentially offering deeper insights and improved understanding of evolutionary processes.

Language Model Use#

This research leverages a pre-trained genomic language model, DNABERT2, to revolutionize phylogenetic inference. Instead of relying on traditional methods or aligned sequences, PhyloGen uses the language model to generate and optimize phylogenetic trees directly from raw genomic sequences. This innovative approach bypasses the need for evolutionary models or sequence alignment, thereby significantly enhancing the efficiency and accuracy of phylogenetic analysis. The language model acts as a powerful feature extractor, capturing intricate sequence patterns and relationships that inform both tree topology and branch length estimations, leading to a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of evolutionary relationships. By representing species as continuous embeddings, PhyloGen’s generative framework offers increased flexibility and scalability compared to existing methods. This paradigm shift demonstrates the potential of language models to transform complex biological problems.

Model Architecture#

The model architecture of PhyloGen is characterized by its innovative three-module design, moving beyond traditional independent optimization of tree topology and branch lengths. Feature Extraction leverages a pre-trained genomic language model (DNABERT2) to generate rich species embeddings, capturing crucial sequence information. These embeddings then feed into the PhyloTree Construction module, which employs a neighbor-joining algorithm to generate an initial tree topology, represented as topological embeddings. This initial topology is not fixed but rather refined. Finally, the PhyloTree Structure Modeling module co-optimizes tree topology and branch lengths via a sophisticated process involving TreeEncoder, TreeDecoder, and a DGCNN-enhanced branch length learning component. This joint optimization allows PhyloGen to effectively capture the intricate interplay between topological and continuous phylogenetic parameters, which is a significant improvement over existing methods. A crucial aspect of PhyloGen’s architecture is its reliance on a novel scoring function to enhance gradient stability and thereby improve the speed and reliability of model training.

Experiment Results#

An effective ‘Experiment Results’ section would meticulously detail the experimental setup, including datasets, evaluation metrics, and baselines. It should clearly present the quantitative results, using tables and figures to showcase model performance across various settings. Statistical significance should be explicitly addressed, with appropriate measures like p-values or confidence intervals included to support the claims. Crucially, the results must be discussed in a thoughtful manner, identifying trends, unexpected outcomes, and limitations. A thorough analysis that relates the findings back to the paper’s hypotheses and contributions is key. Comparative analysis against baselines is essential, demonstrating the proposed method’s improvements and highlighting areas where it surpasses or falls short. Finally, visualizations, especially if dealing with complex data structures, would significantly aid in conveying the results effectively. The overall goal is to leave the reader with a clear and confident understanding of the methodology’s strengths and weaknesses, supported by robust evidence.

Future Directions#

Future research directions for PhyloGen could focus on several key areas. Improving the scalability of the model to handle larger datasets with thousands of species is crucial. This might involve exploring more efficient tree construction algorithms or implementing parallel processing techniques. Incorporating more complex evolutionary models beyond the current basic models would significantly enhance accuracy and allow for more nuanced phylogenetic analysis. Integrating additional data types such as gene expression data or protein sequences could provide a more holistic view of evolutionary relationships. Addressing the challenge of horizontal gene transfer and other non-tree-like evolutionary processes would necessitate novel approaches that go beyond simple tree-based models. Finally, rigorous validation and benchmarking against a wider range of datasets and existing methods are necessary to establish PhyloGen’s generalizability and reliability across diverse phylogenetic scenarios.

More visual insights#

More on figures

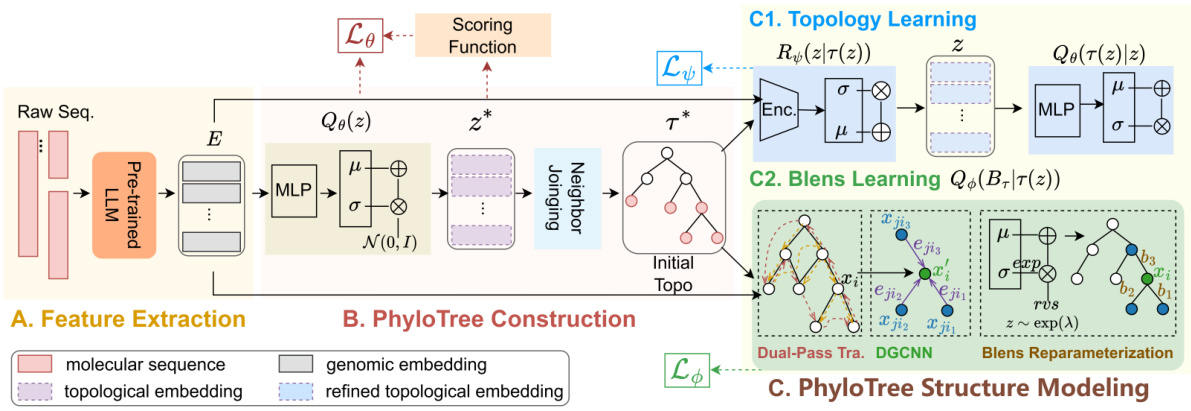

🔼 This figure illustrates the overall framework of PhyloGen, a novel phylogenetic tree inference method. It consists of three main modules: Feature Extraction, PhyloTree Construction, and PhyloTree Structure Modeling. The Feature Extraction module uses a pre-trained language model to extract genome embeddings from raw sequences. The PhyloTree Construction module utilizes these embeddings to generate an initial tree structure using the Neighbor-Joining algorithm. Finally, the PhyloTree Structure Modeling module jointly optimizes the tree topology and branch lengths through two components: a topology learning component and a branch length learning component. The topology learning component refines the initial tree structure by leveraging an encoder and a decoder. The branch length learning component utilizes a dual-pass traversal mechanism and a Dynamic Graph Convolutional Neural Network (DGCNN) to optimize branch lengths. The entire process aims to generate and refine a phylogenetic tree that accurately reflects evolutionary relationships.

read the caption

Figure 2: Framework of PhyloGen. A. Feature Extraction module extracts genome embeddings E from raw sequences Y using a pre-trained language model. B. PhyloTree Construction module uses E to compute topological parameters, which generate an initial tree structure T* via the Neighbor-Joining algorithm. C. PhyloTree Structure Modeling module jointly model T and B, through the topology learning component (TreeEncoder R and TreeDecoder Q) and the branch length (Blens) learning component (dual-pass traversal, DGCNN network, Blens reparameterization).

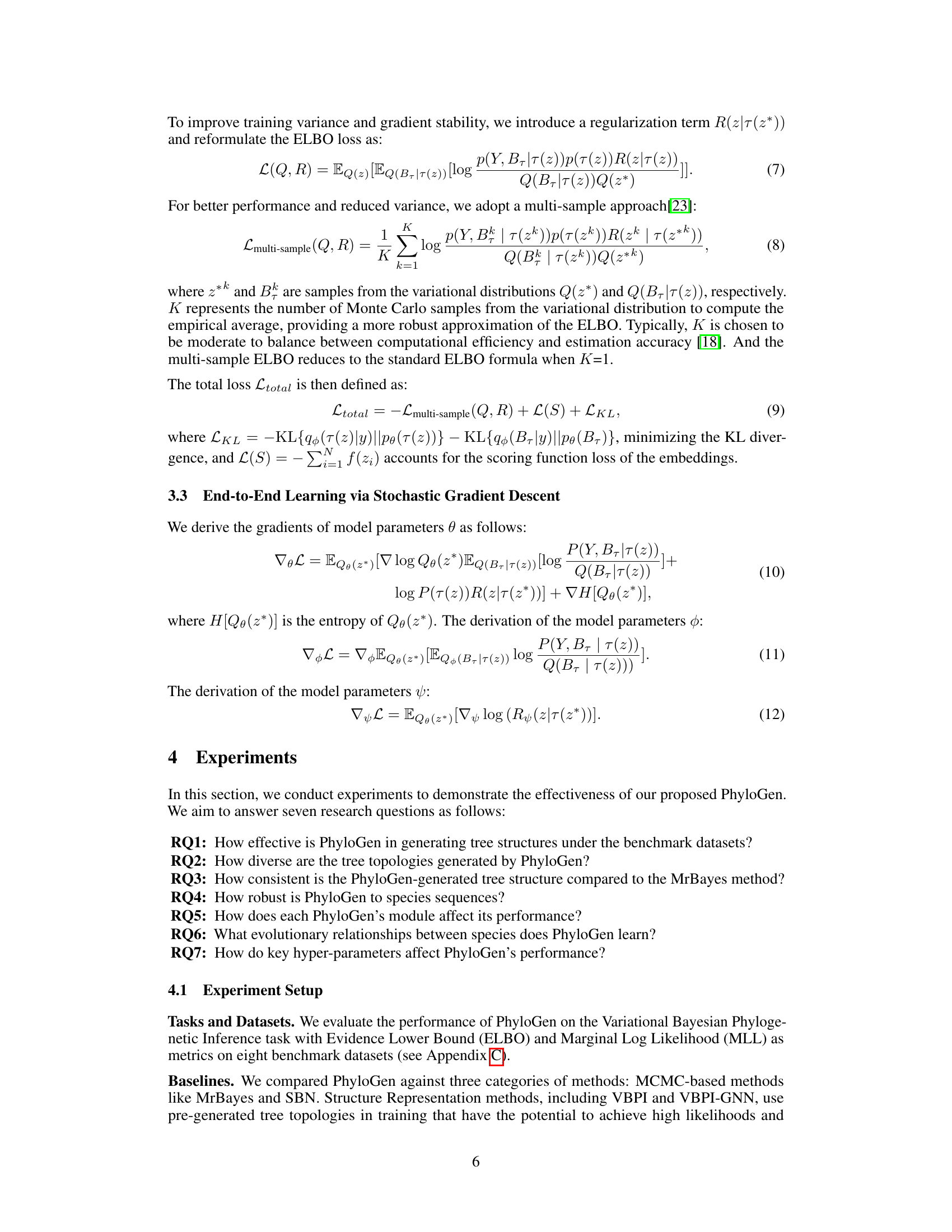

🔼 This figure compares the convergence behavior and stability of the ELBO (Evidence Lower Bound) and a novel scoring function (S) during the training process of the PhyloGen model on dataset DS1. The x-axis represents the training steps, and the y-axis shows the smoothed values of the ELBO and the scoring function. The different colored lines represent different configurations of the scoring function (fully connected, MLP with 2 layers, MLP with 3 layers). The figure aims to demonstrate that the scoring function effectively guides the model’s performance and maintains a consistent optimization trend with the ELBO, thereby improving convergence stability and efficiency. Closer curves indicate better model performance and more stable gradient descent.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of ELBO and Scoring Function over Training Steps on DS1. Closer curves mean better.

🔼 This figure compares the performance of different phylogenetic inference methods (PhyloGen, ARTree, and GeoPhy) on the DS1 dataset using two evaluation metrics: ELBO (Evidence Lower Bound) and MLL (Marginal Log Likelihood). The graphs show the ELBO and MLL values over training steps. PhyloGen demonstrates rapid convergence and significantly better performance compared to the baselines. It highlights PhyloGen’s superior stability and efficiency in phylogenetic tree generation.

read the caption

Figure 4: Comparison of ELBO and MLL Metrics for DS1 Dataset with Different Baselines.

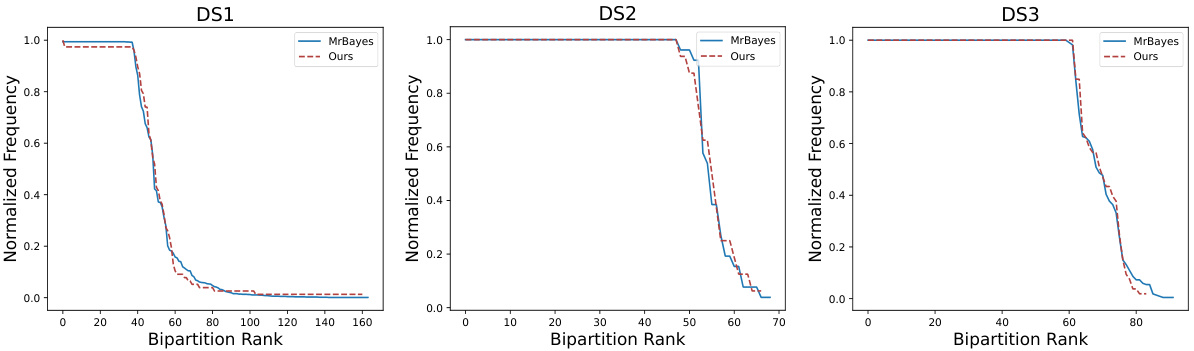

🔼 This figure compares the bipartition frequency distributions of phylogenetic trees generated by PhyloGen and MrBayes for three different datasets (DS1, DS2, and DS3). A bipartition represents a split in the tree, dividing the species into two groups. The x-axis shows the rank of the bipartition (most frequent to least frequent), and the y-axis shows the normalized frequency of that bipartition in the set of trees. The closer the PhyloGen curve is to the MrBayes curve for each dataset, the better, indicating that PhyloGen produces results similar to the established gold-standard method.

read the caption

Figure 5: Comparative Bipartition Frequency Distribution in Tree Topologies for DS1, DS2, and DS3 datasets. The closer the two curves are, the better, which suggests that our method is highly consistent with the gold standard MrBayes approach.

🔼 This figure compares the convergence behavior and stability of the ELBO (Evidence Lower Bound) and a newly introduced scoring function (S) throughout the training process of the PhyloGen model on dataset DS1. The x-axis represents training steps, and the y-axis represents the values of both ELBO and the scoring function. The figure shows that the scoring function closely tracks the ELBO, indicating its effectiveness in guiding the optimization process towards improved performance and stability.

read the caption

Figure 3: Comparison of ELBO and Scoring Function over Training Steps on DS1. Closer curves mean better.

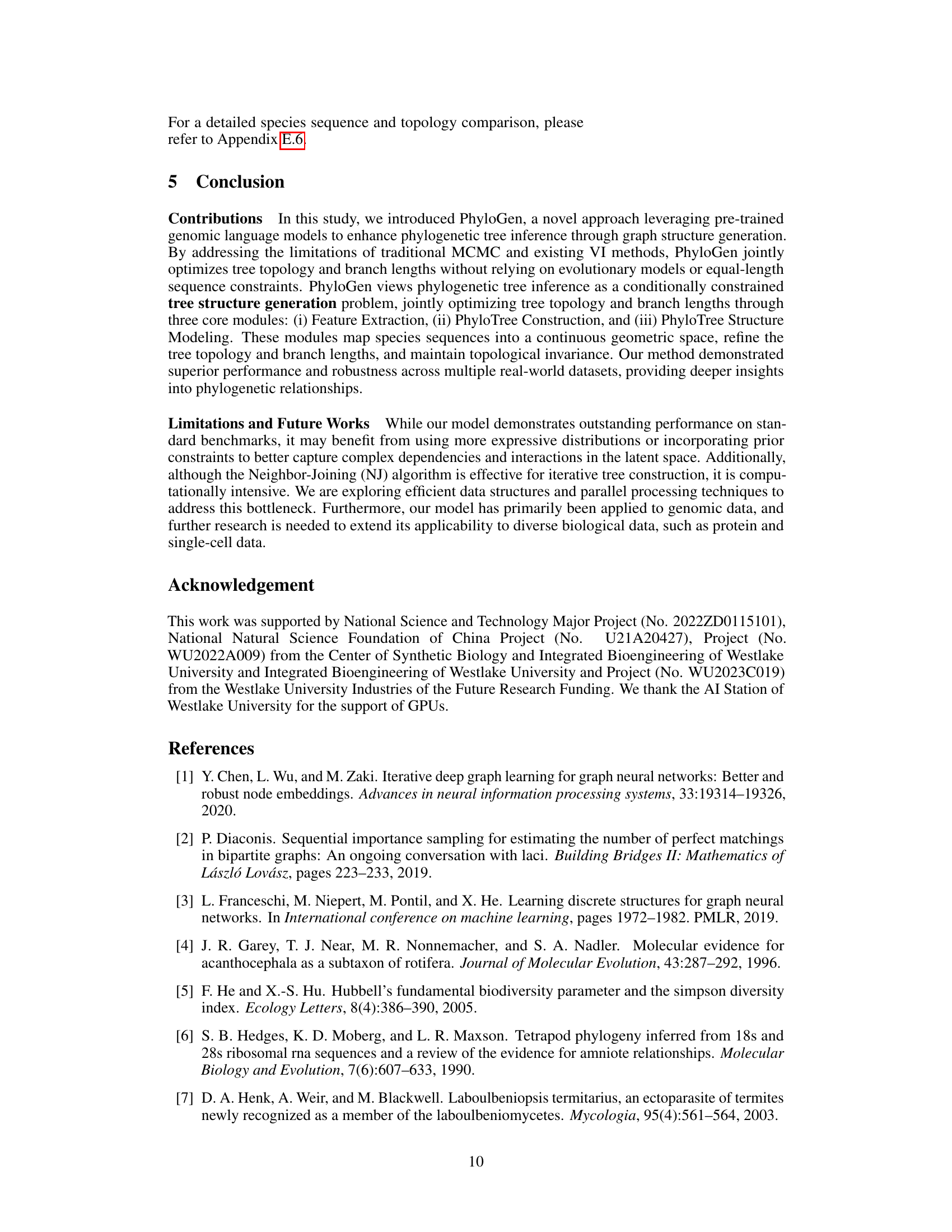

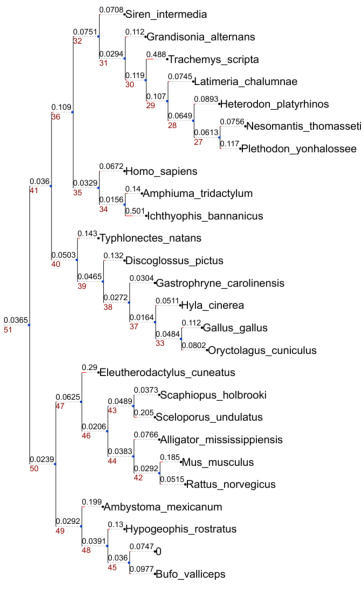

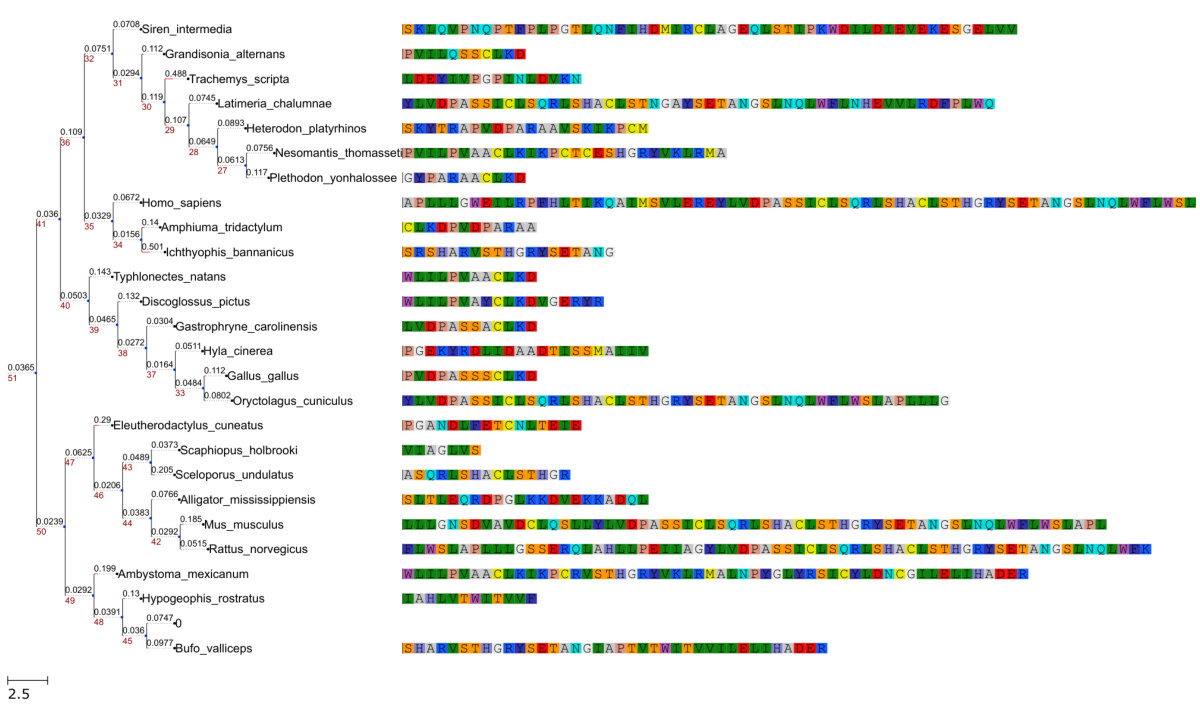

🔼 This figure shows a visualization of phylogenetic trees generated by PhyloGen. The left panel displays a phylogenetic tree for the DS1 dataset, with each leaf node representing a species and branch lengths indicating evolutionary distances. The right panel shows colored sequences representing fragments of the species’ protein sequences, illustrating how PhyloGen avoids requiring uniform sequence length or padding procedures, effectively reflecting actual sequence variation. The color-coding of sequence segments highlights key features that guide tree construction.

read the caption

Figure 9: Visualization of phylogenetic trees. The left side shows a phylogenetic tree constructed from the sequences of the DS1 dataset. Each leaf node represents a specific species, and the text next to the node indicates the species name. On the right side, the colored sequences represent fragments of the species' protein sequences, with different colored blocks corresponding to different amino acid residues. It is worth noting that this method of sequence presentation does not require a uniform sequence length or padding procedure and can effectively reflect actual sequence variations. The scale bar in the lower left corner indicates the ratio between branch length and evolutionary distance. These sequence fragments visualize the key sequence features on which the construction of the phylogenetic tree depends.

🔼 The figure shows the cosine similarity between the scoring function (S) and the evidence lower bound (ELBO) during the training process. Three different configurations of the scoring function (with fully connected layers (FC), 2-layer MLP, and 3-layer MLP) are compared against the ELBO. The plot shows that all three scoring function configurations maintain high similarity (generally above 0.8) with the ELBO throughout training. This suggests that the scoring function is effectively capturing similar information to the ELBO, and thus, it effectively guides the model training towards a more stable and faster gradient descent.

read the caption

Figure 8: Analysis of the Cosine Similarities between Scoring Function and ELBO.

🔼 This figure visualizes phylogenetic trees generated by the PhyloGen model. The left panel shows a tree where each leaf node represents a species from the DS1 dataset, with branch lengths representing evolutionary distances. The right panel shows a color-coded representation of protein sequence fragments for each species, highlighting sequence features used in tree construction. This visualization demonstrates PhyloGen’s ability to handle sequences of varying lengths without padding, directly reflecting actual sequence variations.

read the caption

Figure 9: Visualization of phylogenetic trees. The left side shows a phylogenetic tree constructed from the sequences of the DS1 dataset. Each leaf node represents a specific species, and the text next to the node indicates the species name. On the right side, the colored sequences represent fragments of the species' protein sequences, with different colored blocks corresponding to different amino acid residues. It is worth noting that this method of sequence presentation does not require a uniform sequence length or padding procedure and can effectively reflect actual sequence variations. The scale bar in the lower left corner indicates the ratio between branch length and evolutionary distance. These sequence fragments visualize the key sequence features on which the construction of the phylogenetic tree depends.

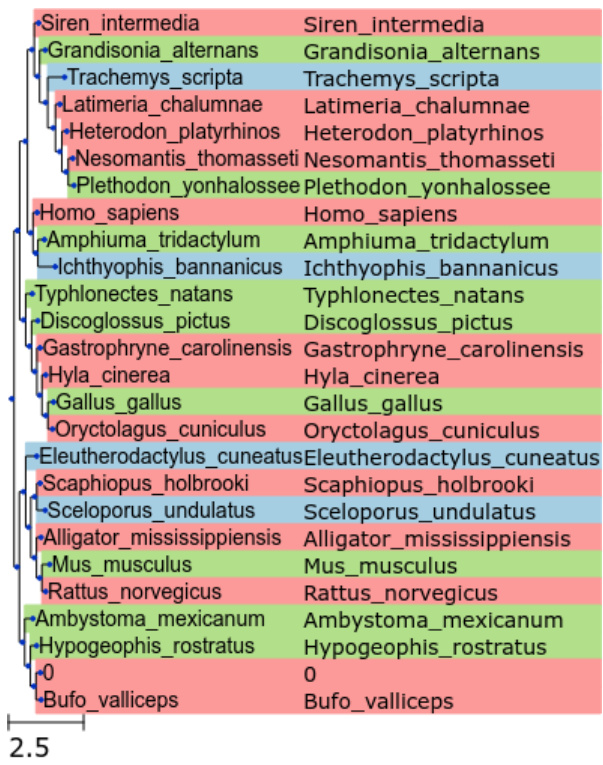

🔼 This figure presents a phylogenetic tree visualization enhanced by a color-coded heatmap. The tree’s structure, based on Newick format data, displays the hierarchical evolutionary relationships between species. Each node’s color represents the level of bipartition support (a measure of confidence) derived from posterior probability analysis: blue for high support (>0.2), green for medium support (>0.1), and red for low support. This visualization method helps to clarify and interpret the phylogenetic relationships shown in the tree.

read the caption

Figure 10: Enhanced visualization of phylogenetic relationships depicted through a coloured heatmap integrated with a phylogenetic tree. The evolutionary tree, structured using Newick format data, illustrates the hierarchical relationships among species. Nodes are distinctly coloured to represent the frequency of bipartition support derived from posterior probability analysis: high support (>0.2) is indicated with blue, medium support (>0.1) with green, and low support with red.

🔼 This figure presents a detailed overview of PhyloGen’s framework. It illustrates three core modules: Feature Extraction, which uses a pre-trained language model to generate genome embeddings from raw sequences; PhyloTree Construction, which uses these embeddings to generate an initial tree structure using the Neighbor-Joining algorithm; and PhyloTree Structure Modeling, which jointly optimizes the tree topology and branch lengths through a topology learning component and a branch length learning component. The topology learning component employs a TreeEncoder and TreeDecoder, while the branch length learning component uses a dual-pass traversal, a DGCNN network, and Blens reparameterization.

read the caption

Figure 2: Framework of PhyloGen. A. Feature Extraction module extracts genome embeddings E from raw sequences Y using a pre-trained language model. B. PhyloTree Construction module uses E to compute topological parameters, which generate an initial tree structure T* via the Neighbor-Joining algorithm. C. PhyloTree Structure Modeling module jointly model T and B, through the topology learning component (TreeEncoder R and TreeDecoder Q) and the branch length (Blens) learning component (dual-pass traversal, DGCNN network, Blens reparameterization).

More on tables

🔼 This table presents three metrics used to evaluate the diversity of tree topologies generated by PhyloGen and two other methods (MrBayes and GeoPhy) on the DS1 dataset. The metrics are: Simpson’s Diversity Index (higher values indicate greater diversity), Top Frequency (lower values indicate better balance among topologies), and Top 95% Frequency (higher values indicate greater diversity in the most frequent topologies). PhyloGen shows the highest diversity index and top 95% frequency and the lowest top frequency, indicating a more balanced and diverse generation of tree topologies.

read the caption

Table 3: Diversity of tree topologies.

🔼 This table presents the ELBO scores achieved by different methods across eight datasets. The ELBO (Evidence Lower Bound) is a metric used in variational inference to evaluate the quality of the approximation to the true posterior distribution. Higher ELBO scores indicate a better approximation and thus better performance of the method. The table highlights the best-performing method for each dataset, along with the second best score from traditional methods and from tree structure generation methods.

read the caption

Table 2: Comparison of ELBO (↑) on eight datasets. GeoPhy is not provided in the original paper and is tested by us. Boldface for the highest result, underline for the second highest result.

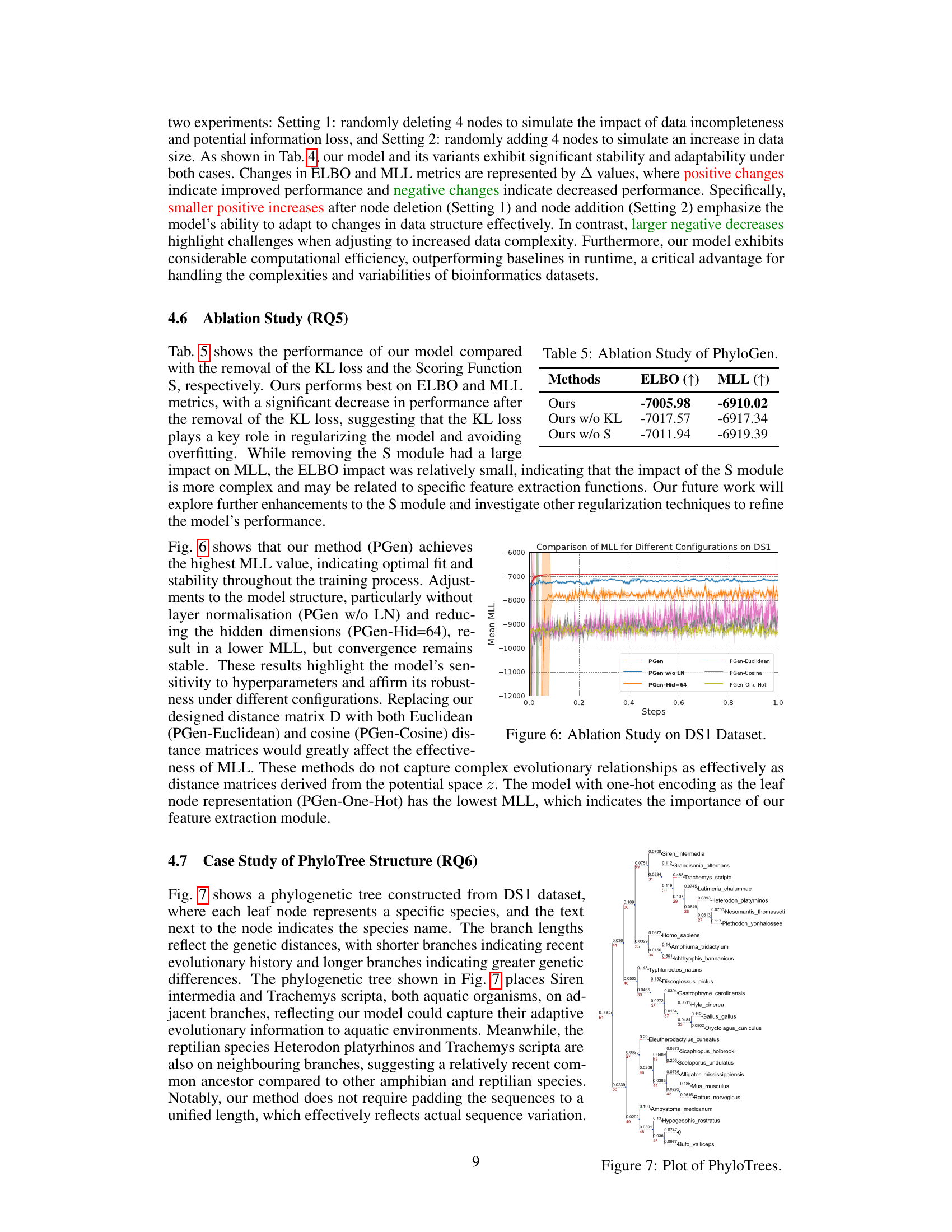

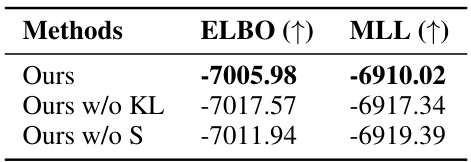

🔼 This table presents the results of an ablation study conducted on the PhyloGen model. The study evaluates the impact of removing key components of the model on its overall performance. Specifically, it compares the performance metrics (ELBO and MLL) of the original PhyloGen model against two variants: one without the KL loss and another without the scoring function (S). The results illustrate the relative contribution of each component to the model’s effectiveness.

read the caption

Table 5: Ablation Study of PhyloGen.

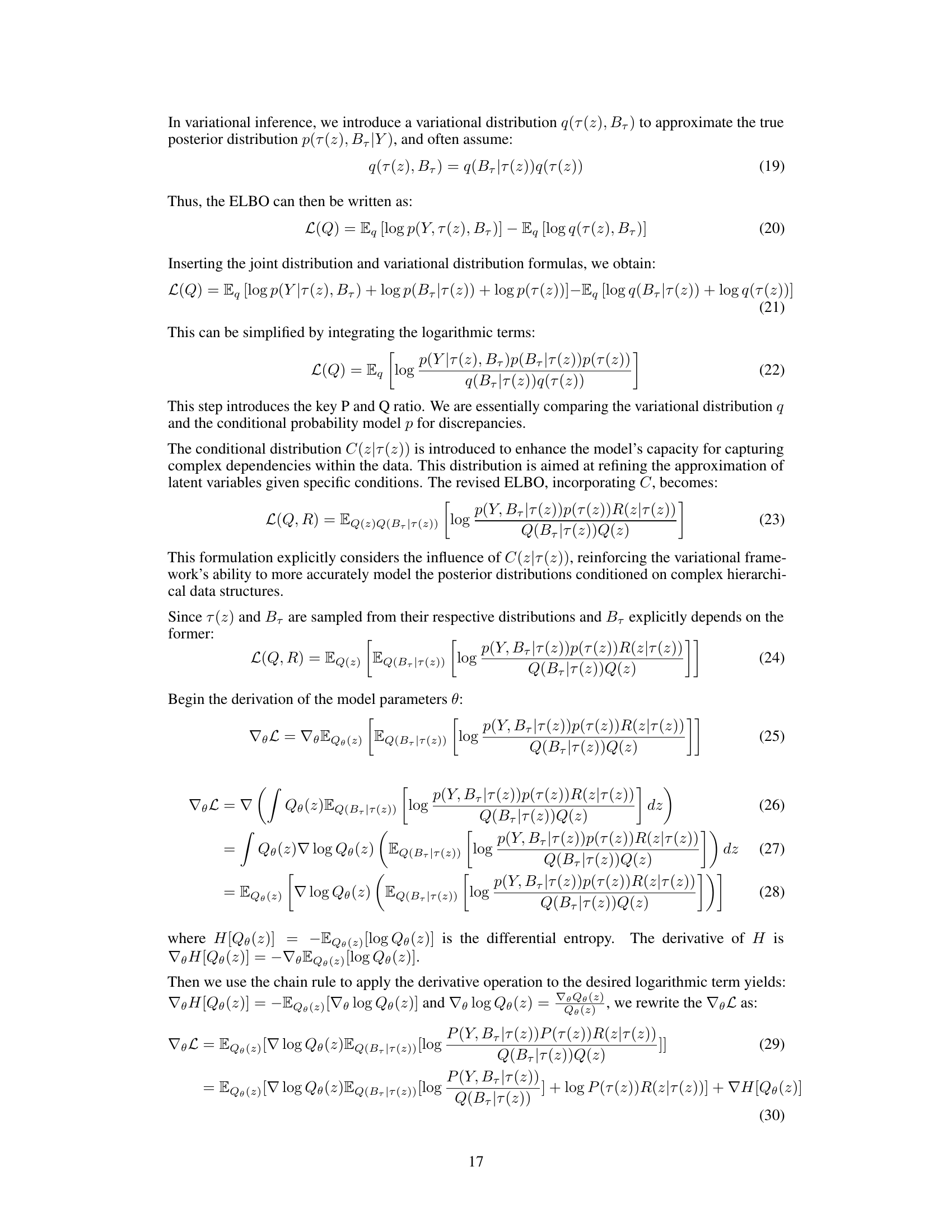

🔼 This table presents the characteristics of eight benchmark datasets (DS1-DS8) used in the PhyloGen experiments. For each dataset, it lists the number of species and the number of sites (presumably representing the length of the biological sequences). It also provides references to the sources from where these datasets were obtained. The datasets vary in size, reflecting the diversity of phylogenetic studies.

read the caption

Table 6: Statistics of the benchmark datasets from DS1 to DS8.

🔼 This table compares the Marginal Log-Likelihood (MLL) scores achieved by different phylogenetic inference methods across eight benchmark datasets. It highlights the performance of PhyloGen (the proposed method) against MCMC-based methods (MrBayes, SBN), structure representation methods (VBPI, VBPI-GNN), and other structure generation methods (ARTree, GeoPhy, PhyloGFN). The table shows that PhyloGen achieves the highest MLL scores on most datasets, indicating superior accuracy in phylogenetic inference.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the MLL (↑) with different approaches in eight benchmark datasets. VBPI and VBPI-GNN use pre-generated tree topologies in training and thus are not directly comparable. Boldface for the highest result, underline for the second highest from traditional methods, and underline for the second highest from tree structure generation methods.

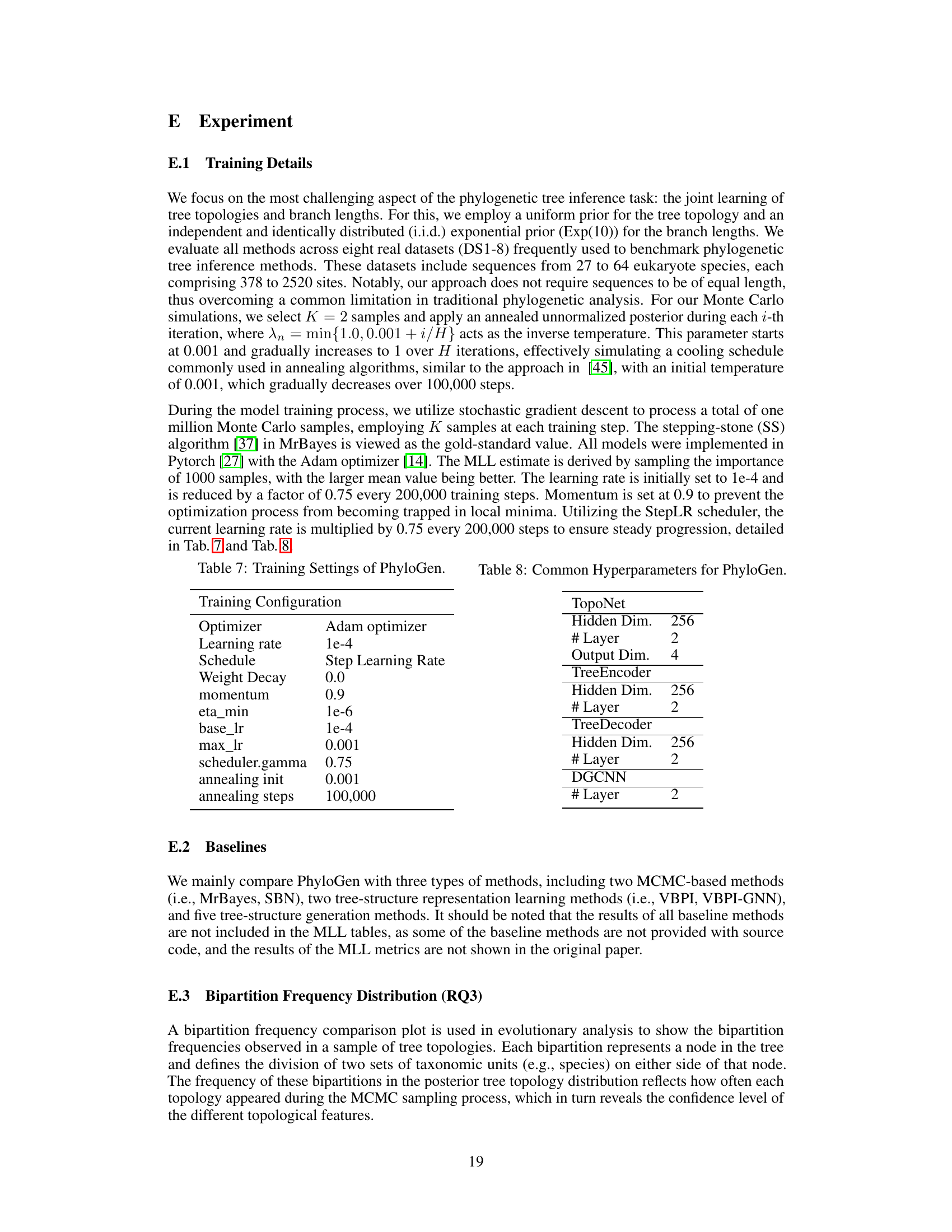

🔼 This table presents the hyperparameters and training settings used for the PhyloGen model. It includes details such as the optimizer used (Adam), the initial learning rate (1e-4), the learning rate scheduling method (Step Learning Rate), weight decay, momentum, minimum learning rate, base learning rate, maximum learning rate, gamma for the scheduler, annealing initialization value, and the total number of annealing steps.

read the caption

Table 7: Training Settings of PhyloGen.

🔼 This table compares the Marginal Log-Likelihood (MLL) scores achieved by different phylogenetic inference methods across eight benchmark datasets. It highlights the performance of PhyloGen (the authors’ method) against other methods categorized as MCMC-based, structure representation learning, and structure generation methods. The table emphasizes that PhyloGen’s performance is superior. The use of pre-generated topologies in some methods is also noted, impacting direct comparability.

read the caption

Table 1: Comparison of the MLL (↑) with different approaches in eight benchmark datasets. VBPI and VBPI-GNN use pre-generated tree topologies in training and thus are not directly comparable. Boldface for the highest result, underline for the second highest from traditional methods, and underline for the second highest from tree structure generation methods.

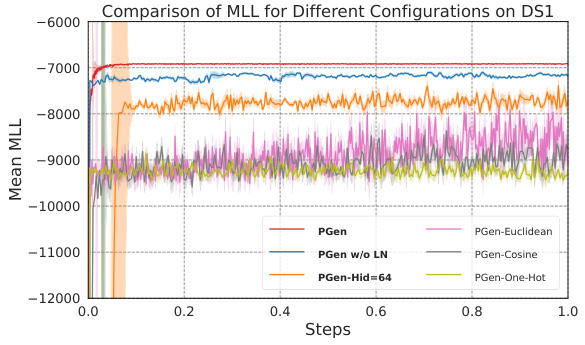

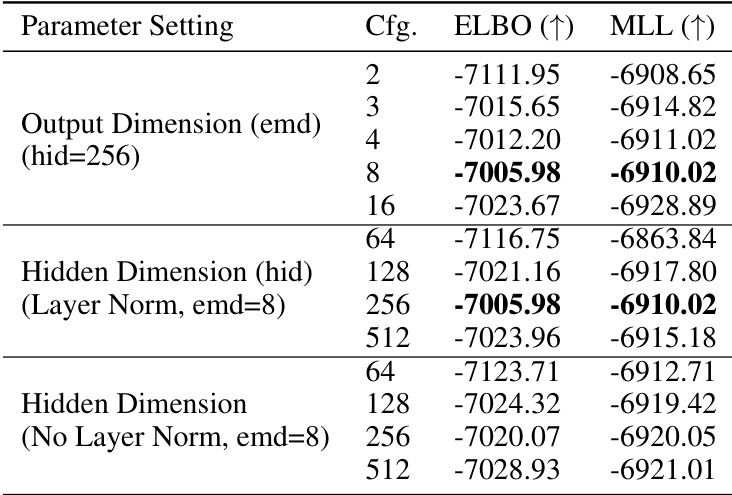

🔼 This table presents the results of a hyperparameter analysis conducted on the PhyloGen model. It shows the impact of different output dimensions, hidden dimensions (with and without layer normalization), on the model’s performance as measured by the ELBO and MLL metrics. The analysis aims to identify the optimal hyperparameter settings for the best performance of the PhyloGen model.

read the caption

Table 9: Hyperparameter Analysis of PhyloGen Performance in Various Parameter Configurations.

Full paper#