TL;DR#

Structured state space models (SSMs) are fundamental to many neural networks, but the use of complex (rather than real) numbers in their parameterization remains poorly understood. This paper addresses this gap by formally demonstrating that while both real and complex SSMs can theoretically express any linear time-invariant mapping, complex SSMs do so far more efficiently. The current use of complex numbers in SSMs is based on empirical evidence alone, and therefore, the paper’s theoretical explanation is significant.

This research uses formal proofs to show that real SSMs often require exponentially larger dimensions or parameter magnitudes to approximate the same mappings achieved by complex SSMs. This issue is further exacerbated when handling common oscillatory mappings. The paper’s controlled experiments validate its theoretical findings, highlighting the substantial performance improvements gained by using complex parameterizations. The results also suggest potential refinements to the theory by incorporating the recently introduced concept of ‘selectivity’ in SSM architectures.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial because it resolves the open problem of theoretically explaining the benefits of complex parameterizations in structured state space models (SSMs), a core component of many prominent neural network architectures. Its findings provide a strong theoretical foundation for future research and guide the design of more efficient and effective neural network architectures. The experiments confirm the theoretical findings and suggest potential avenues for extending the theory, especially considering recent advances in SSMs with selectivity.

Visual Insights#

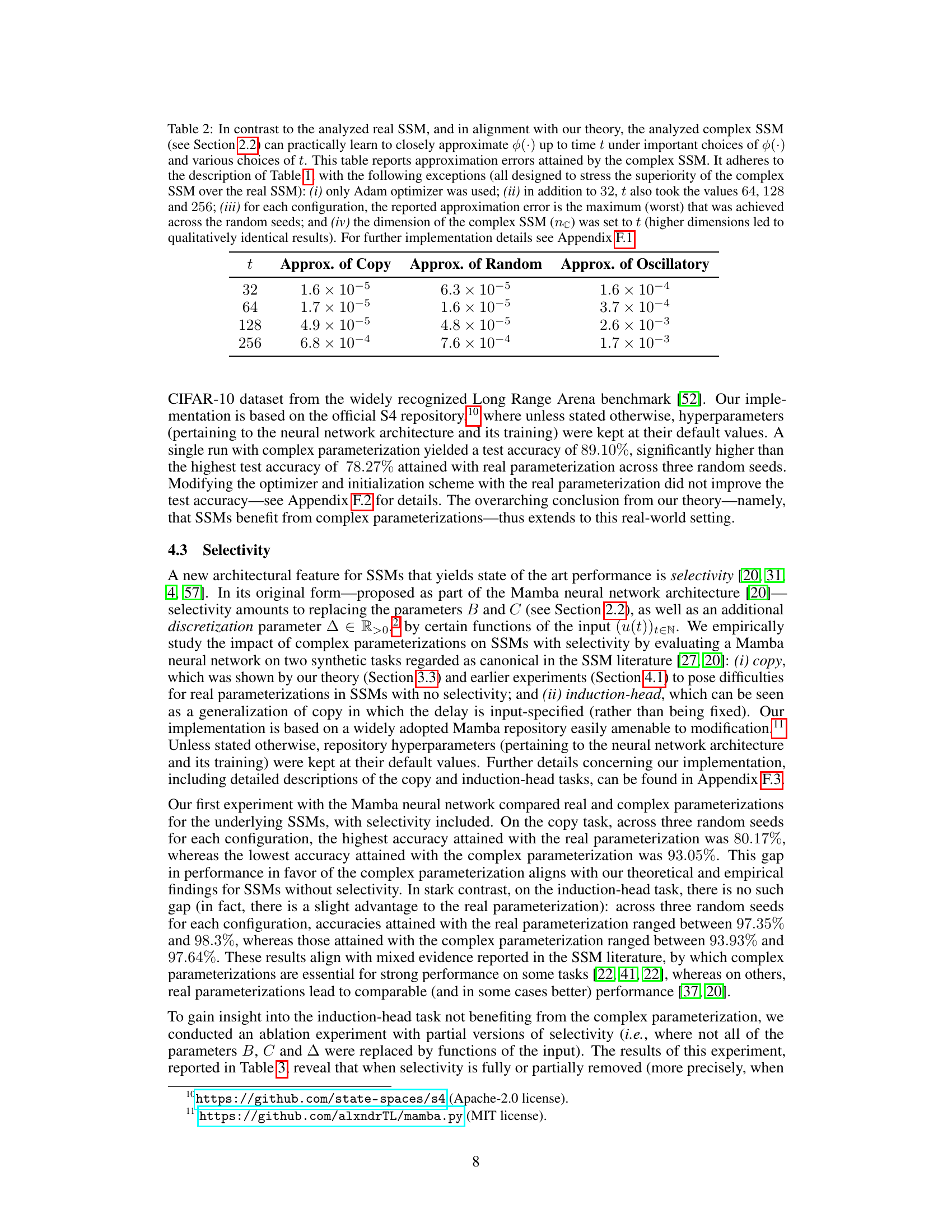

🔼 The figure illustrates the induction-head task, a sequence modeling task where the model must identify and copy a specific subsequence from the input sequence. The input sequence consists of a prefix, a copy token (c), a subsequence X (of length h), more tokens, another copy token (c), and a repeated subsequence X (but not the full length). The output sequence is the subsequence X, shifted to the end of the sequence.

read the caption

Figure 1: Illustration of the induction-head task. See Appendix F.3 for details.

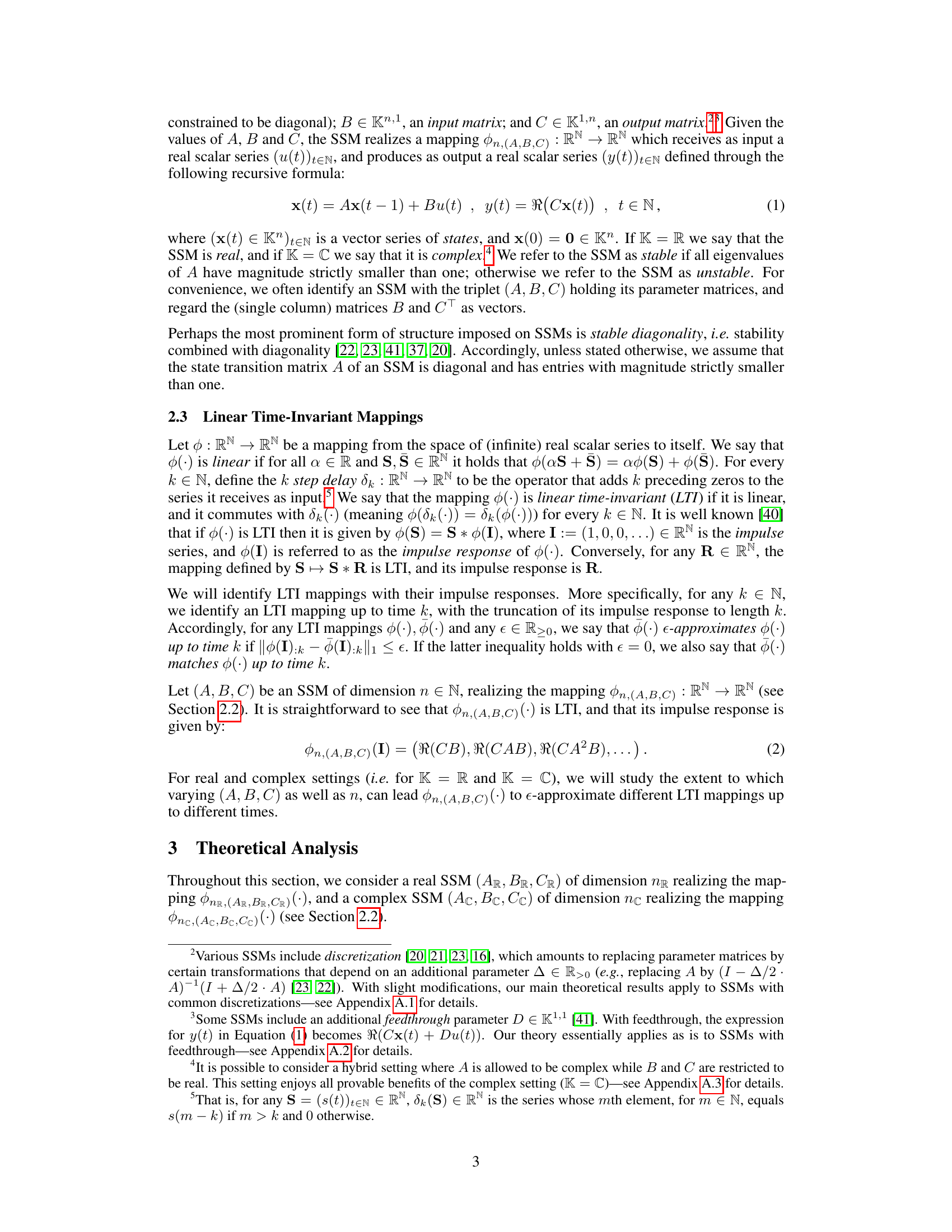

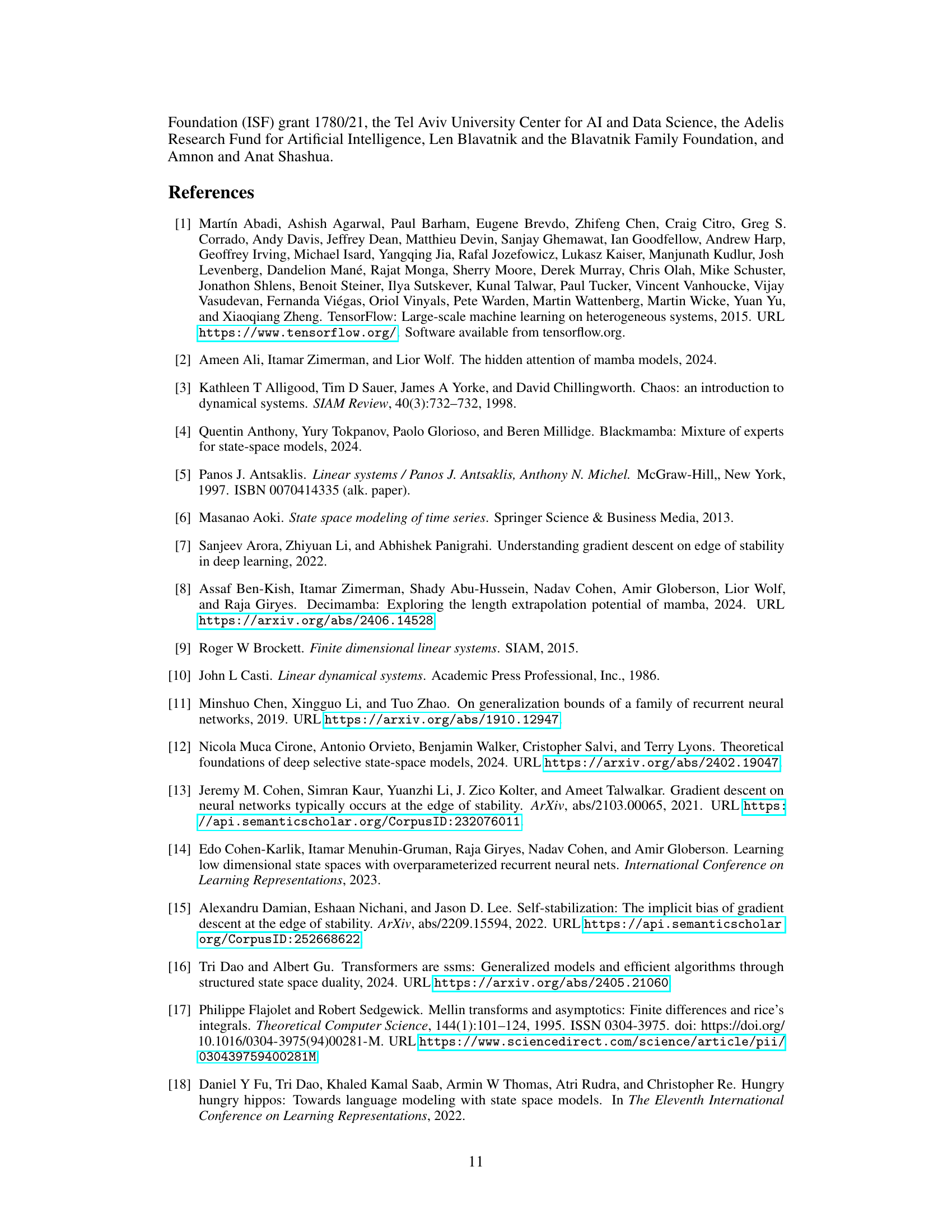

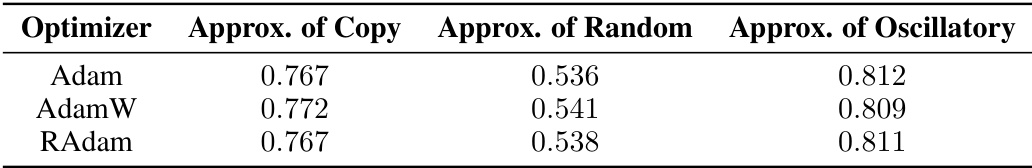

🔼 This table shows the approximation error of a real SSM in approximating three different mappings (copy, random, oscillatory) up to time t=32. Three different optimizers were used, and the minimum error across five random seeds is reported. The dimension of the SSM was 1024.

read the caption

Table 1: In accordance with our theory, the analyzed real SSM (see Section 2.2) cannot practically learn to closely approximate (·) up to time t under important choices of (·), even when t is moderate. This table reports the approximation error attained by the real SSM, i.e. the minimum with which a mapping learned by the real SSM -approximates (·) up to time t (see Section 2.3), when t = 32 and (·) varies over the following possibilities: the canonical copy (delay) mapping from Corollary 1; the random (generic) mapping from Corollary 2; and the basic oscillatory mapping from Corollary 3. Learning was implemented by applying one of three possible gradient-based optimizers-Adam [29], AdamW [36] or RAdam [33]-to a loss as in our theory (see Appendix C). For each choice of (·), reported approximation errors are normalized (scaled) such that a value of one is attained by the trivial zero mapping. Each configuration was evaluated with five random seeds, and its reported approximation error is the minimum (best) that was attained. The dimension of the real SSM (NR) was set to 1024; other choices of dimension led to qualitatively identical results. For further implementation details see Appendix F.1.

In-depth insights#

Complex SSMs#

The concept of “Complex SSMs” introduces a crucial advancement in structured state space models by employing complex-valued parameters instead of real-valued ones. This seemingly simple change unlocks significant advantages in expressiveness and efficiency. Complex SSMs can represent a wider range of dynamical systems, particularly those involving oscillations, with far fewer parameters than their real-valued counterparts. This is particularly relevant for modeling real-world phenomena exhibiting oscillatory behavior. Furthermore, the use of complex numbers leads to improved numerical stability during training and inference, a key challenge in SSMs. The theoretical analysis and empirical results strongly support the benefits of complex parameterizations, demonstrating clear performance gains in various tasks. While the advantages aren’t universal, applying complex numbers to SSMs offers a compelling pathway for enhancing both model capabilities and training efficiency.

Expressiveness Gap#

The concept of “Expressiveness Gap” in the context of structured state space models (SSM) highlights a crucial difference in the ability of real and complex SSMs to represent dynamical systems. Real SSMs, while universal in theory (capable of approximating any linear time-invariant mapping given sufficient dimensionality), struggle to efficiently express oscillatory behaviors. This inefficiency manifests as an exponential scaling of either the model’s dimension or parameter magnitudes. In contrast, complex SSMs achieve the same universality with significantly less computational cost, demonstrating a compelling expressiveness advantage for systems exhibiting oscillations. The gap isn’t simply about theoretical capability but also practical learnability; training real SSMs to match the complex models’ performance requires exponentially more resources, making complex parameterizations much more efficient in practice. This ’expressiveness gap’ underlines a fundamental difference between real and complex number systems in representing certain dynamical systems, with profound implications for the design and training of neural network architectures based on SSMs.

Learnability Limits#

The concept of ‘Learnability Limits’ in the context of the research paper likely explores the boundaries of what can be effectively learned by different types of structured state space models (SSMs). It would delve into the inherent limitations imposed by the choice of parameterization (real versus complex). A key aspect would be the demonstration of exponential barriers to learning for real-valued SSMs when attempting to approximate certain mappings, in contrast to the linear scaling behavior of complex-valued SSMs. This would likely involve analyzing the magnitude of model parameters, required computational resources, or number of training iterations necessary to achieve a desired level of accuracy. The analysis would focus on theoretical justifications, possibly using tools from approximation theory or numerical analysis, and supported by empirical evidence from experiments on various tasks. The section would likely highlight a critical trade-off between model complexity, expressiveness, and the practical feasibility of learning, emphasizing that complex parameterizations, while offering superior expressiveness, aren’t always superior in learnability for all tasks, especially in the presence of architectural features like selectivity.

Selectivity’s Role#

The concept of selectivity, a novel architectural feature enhancing state-of-the-art SSM performance, introduces a nuanced perspective on the benefits of complex parameterizations. Selectivity modifies the input and output matrices (B and C) and a discretization parameter, making them functions of the input itself. This dynamic adjustment allows real SSMs to achieve performance comparable to, or even surpassing, complex SSMs, particularly in tasks such as the induction-head task where input data offers rich frequency information. This suggests selectivity’s capability to mitigate the limitations inherent to real parameterizations. The observed performance discrepancies across different tasks (copy vs. induction-head) highlight the intricate interplay between selectivity, parameterization (real or complex), and task characteristics. Future research should investigate the extension of theoretical frameworks to incorporate selectivity, clarifying its influence and interactions with complex parameterizations to fully delineate the practical advantages of each approach.

Future Research#

Future research directions stemming from this work are manifold. Extending the theoretical framework to incorporate selectivity is crucial, as this architectural feature shows promise in altering the relative benefits of real versus complex parameterizations. A more precise quantification of the expressiveness gap between real and complex SSMs is also needed. Investigating the impact of implicit bias in gradient descent on the choice of parameterization would provide further insight into the practical learning dynamics. Finally, the current empirical findings, while supportive, should be broadened with more diverse real-world datasets and tasks to further confirm the generalizability of the observed benefits. A deeper exploration of the types of oscillations that lead to the exponentiality problem in real SSMs would be particularly valuable, potentially leveraging analytical tools such as the Nørlund-Rice integral. Addressing these points would contribute significantly to a complete understanding of the advantages of complex parameterizations in SSMs and guide future improvements in sequence modeling.

More visual insights#

More on tables

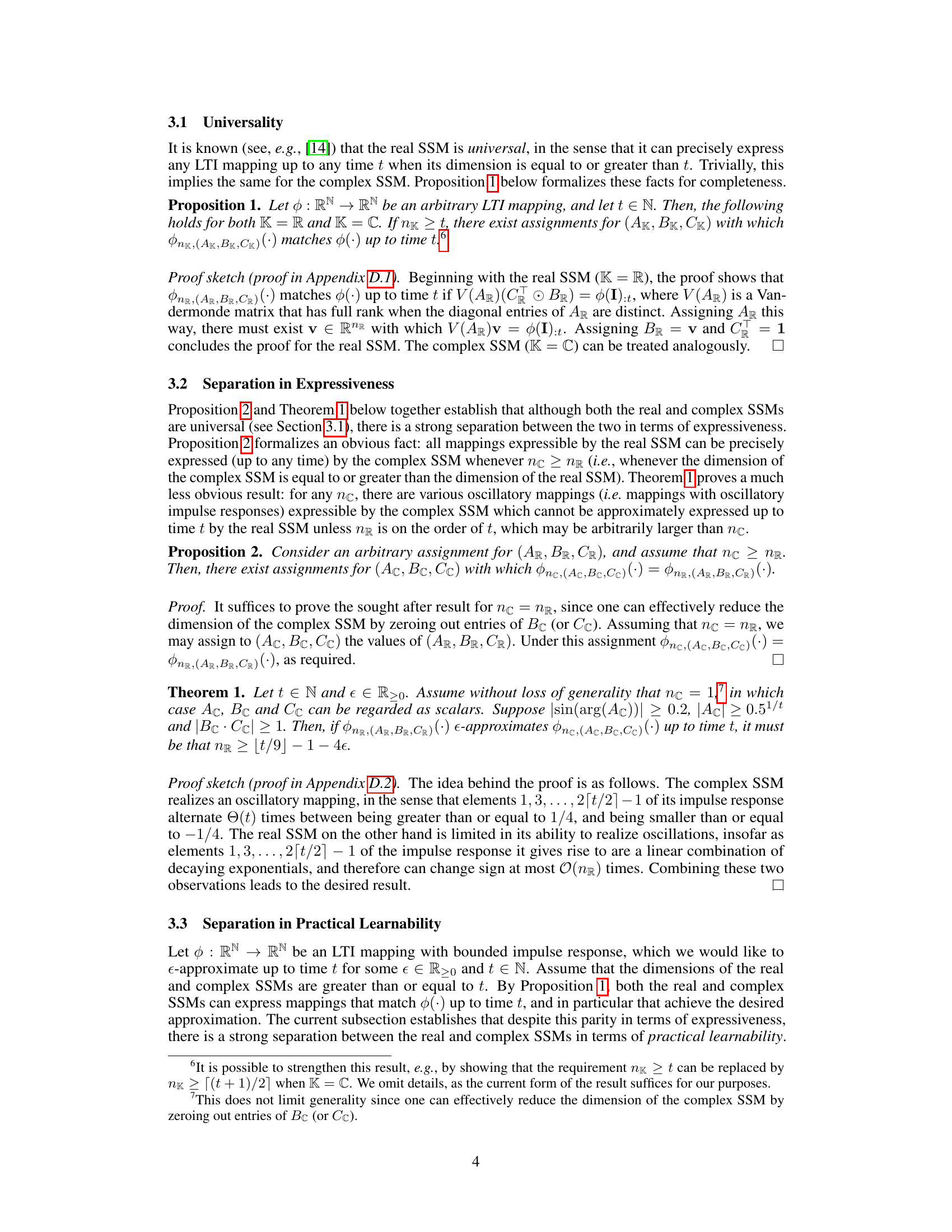

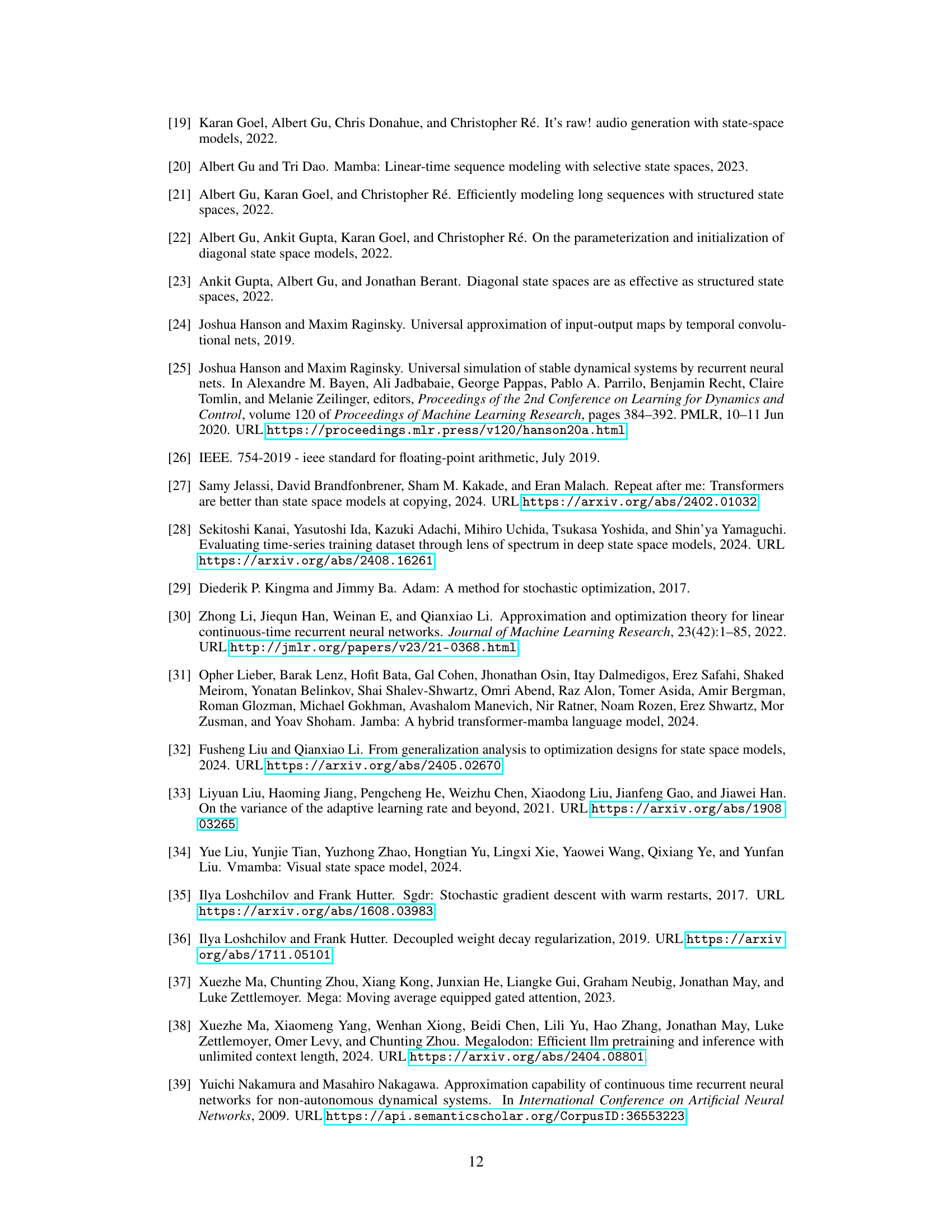

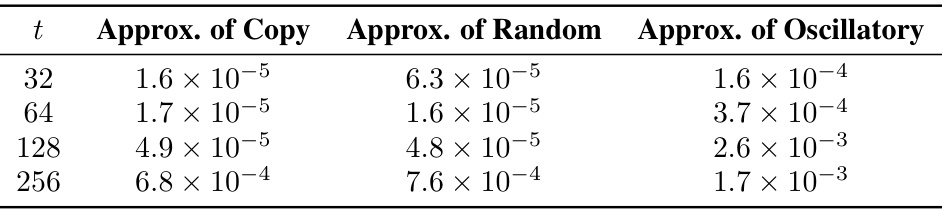

🔼 This table presents the approximation errors achieved by the complex SSM when learning to approximate various mappings up to time t. It contrasts the results with those from the real SSM (Table 1) by using a single optimizer, testing at different times t, reporting the maximum errors instead of minimum, and setting the dimension to t (for better demonstration of complex SSM’s superiority).

read the caption

Table 2: In contrast to the analyzed real SSM, and in alignment with our theory, the analyzed complex SSM (see Section 2.2) can practically learn to closely approximate (·) up to time t under important choices of (·) and various choices of t. This table reports approximation errors attained by the complex SSM. It adheres to the description of Table 1, with the following exceptions (all designed to stress the superiority of the complex SSM over the real SSM): (i) only Adam optimizer was used; (ii) in addition to 32, t also took the values 64, 128 and 256; (iii) for each configuration, the reported approximation error is the maximum (worst) that was achieved across the random seeds; and (iv) the dimension of the complex SSM (nc) was set to t (higher dimensions led to qualitatively identical results). For further implementation details see Appendix F.1.

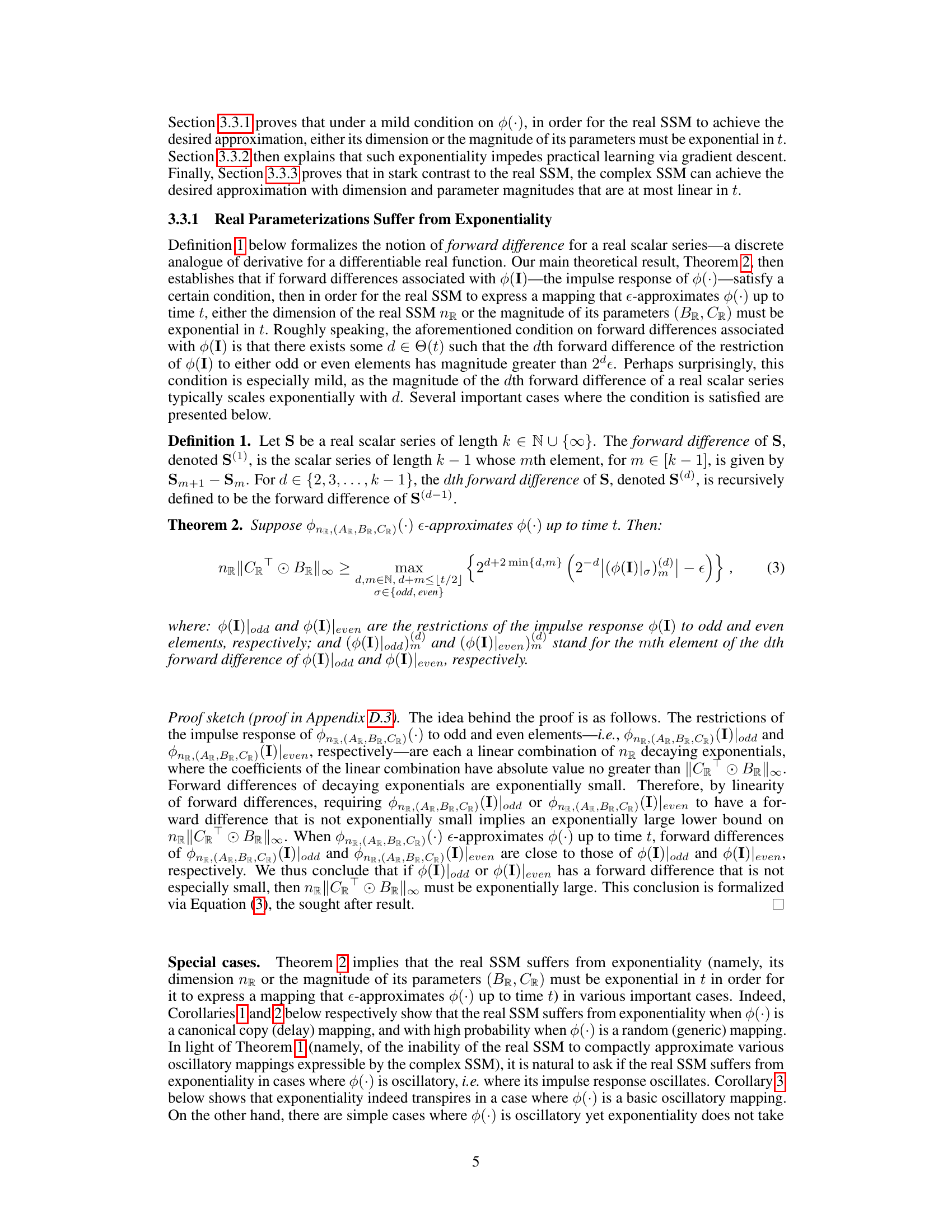

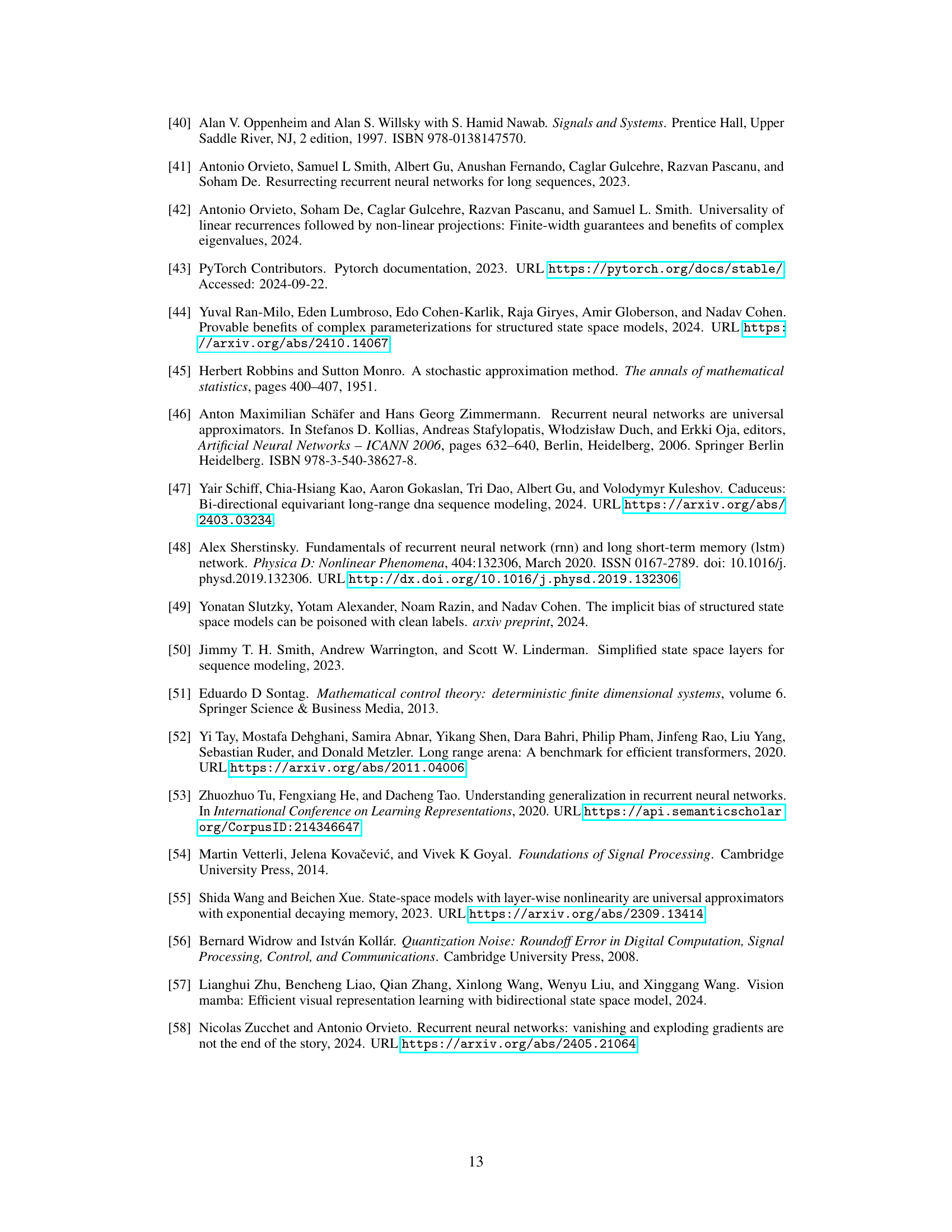

🔼 This table shows the results of an ablation study on the impact of complex parameterizations in SSMs with selectivity. It tests a Mamba neural network on a synthetic induction-head task, varying which parameters (input matrix B, output matrix C, and discretization parameter Δ) utilize selectivity. The table compares the accuracy of real and complex parameterizations under different selectivity configurations.

read the caption

Table 3: Ablation experiment demonstrating that real parameterizations can compare (favorably) to complex parameterizations for SSMs with selectivity, but complex parameterizations become superior when selectivity is fully or partially removed. This table reports test accuracies attained by a Mamba neural network [20] on a synthetic induction-head task regarded as canonical in the SSM literature [27, 20]. Evaluation included multiple configurations for the SSMs underlying the neural network. Each configuration corresponds to either real or complex parameterization, and to a specific partial version of selectivity—i.e., to a specific combination of parameters that are selective (replaced by functions of the input), where the parameters that may be selective are: the input matrix B; the output matrix C; and a discretization parameter Δ. For each configuration, the highest and lowest accuracies attained across three random seeds are reported. Notice that when both B and C are selective, the real parameterization compares (favorably) to the complex parameterization, whereas otherwise, the complex parameterization is superior. For further implementation details see Appendix F.3.

Full paper#