TL;DR#

Current methods for building robust machine learning models, such as adversarial training, often fail to deliver the desired level of robustness and generalization. A major reason behind this issue is the so-called “implicit bias” of optimization algorithms, which may inadvertently constrain the model’s capacity and limit its ability to generalize well. This is particularly problematic when optimization methods are misaligned with the threat models used to evaluate robustness.

This paper delves into the issue of implicit bias in robust empirical risk minimization (ERM). It explores how optimization algorithms and model architectures can cause this “price of implicit bias”, leading to poor generalization. The researchers investigate this through theoretical analysis of linear models, identifying conditions where specific regularizers are optimal for robust generalization. They further demonstrate the effects of implicit bias through simulation with synthetic data and experiments with neural networks, showing how different optimization algorithms lead to varied levels of model robustness.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in adversarial robustness and machine learning because it reveals the detrimental effects of optimization algorithms’ implicit bias on model robustness, a critical issue hindering progress in the field. It provides a theoretical framework and empirical evidence, opening avenues for developing new optimization techniques and improving model generalization.

Visual Insights#

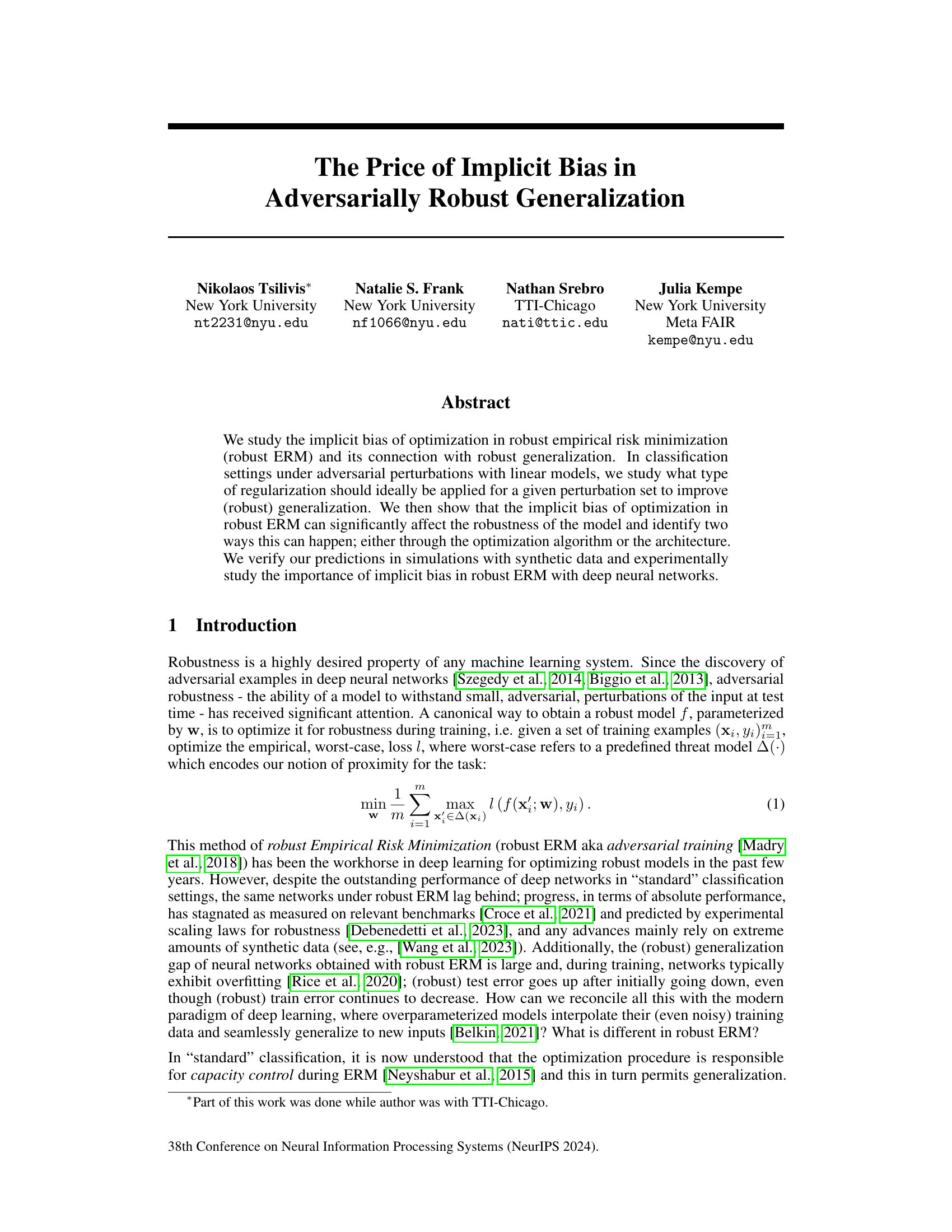

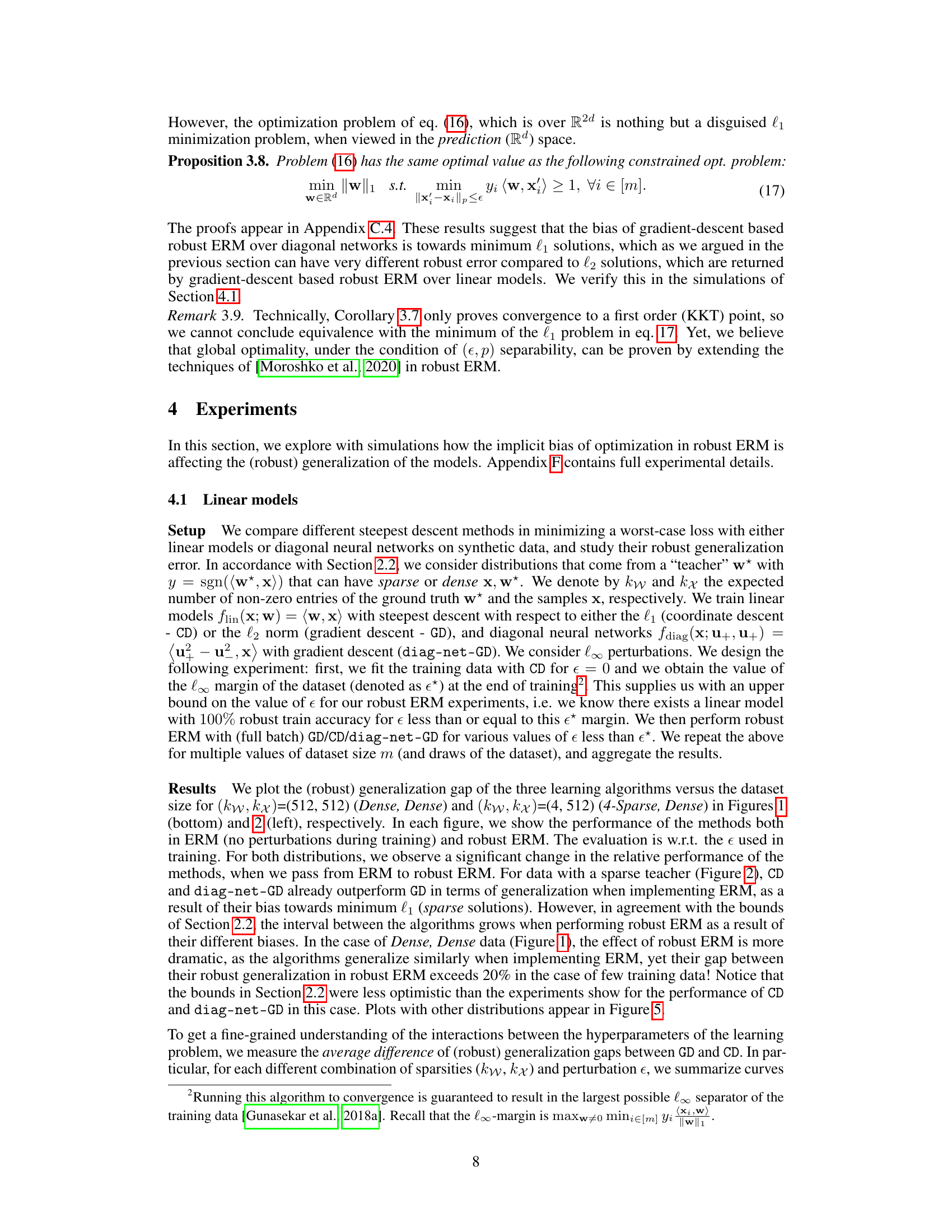

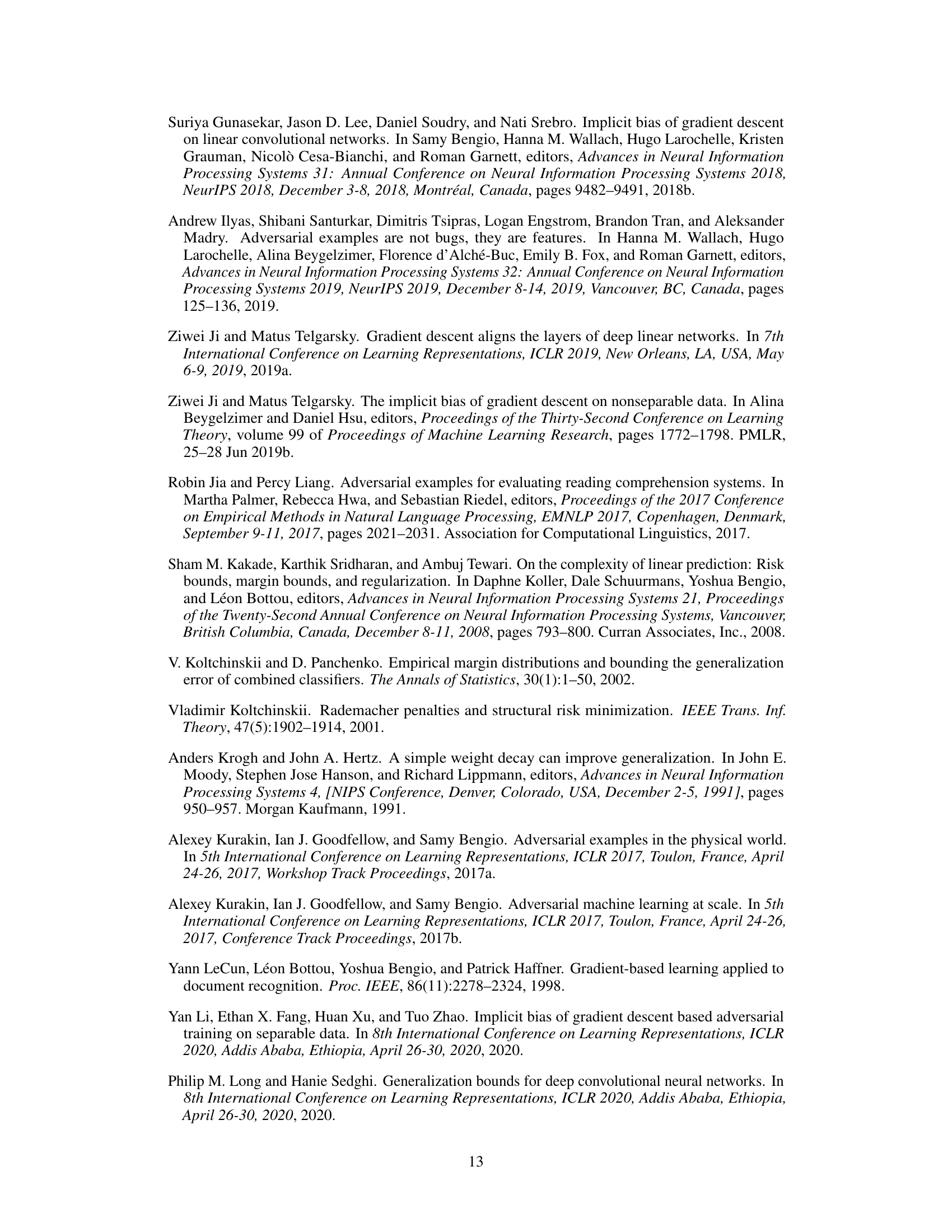

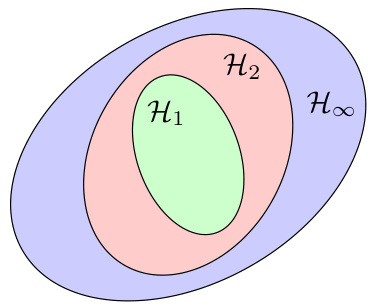

🔼 This figure illustrates the impact of implicit bias on adversarially robust generalization. The top panel shows how different geometric separators (maximizing l2 vs. l∞ distance) affect robustness to l∞ perturbations. The bottom panel presents experimental results on binary classification with linear models under l∞ perturbations, comparing different optimization algorithms (coordinate descent, gradient descent, and gradient descent with diagonal networks). It demonstrates that the choice of optimization algorithm significantly affects the model’s robustness and generalization performance, particularly in robust ERM settings.

read the caption

Figure 1: The price of implicit bias in adversarially robust generalization. Top: An illustration of the role of geometry in robust generalization: a separator that maximizes the l2 distance between the training points (circles) might suffer a large error for test points (stars) perturbed within l∞ balls, while a separator that maximizes the l∞ distance might generalize better. Bottom: Binary classification of Gaussian data with (right) or without (left) l∞ perturbations of the input in Rd using linear models. We plot the (robust) generalization gap, i.e., (robust) train minus (robust) test accuracy, of different learning algorithms versus the training size m. In standard ERM (€ = 0), the algorithms generalize similarly. In robust ERM (€ > 0), however, the implicit bias of gradient descent is hurting the robust generalization of the models, while the implicit bias of coordinate descent/gradient descent with diagonal linear networks aids it. See Section 4 for details.

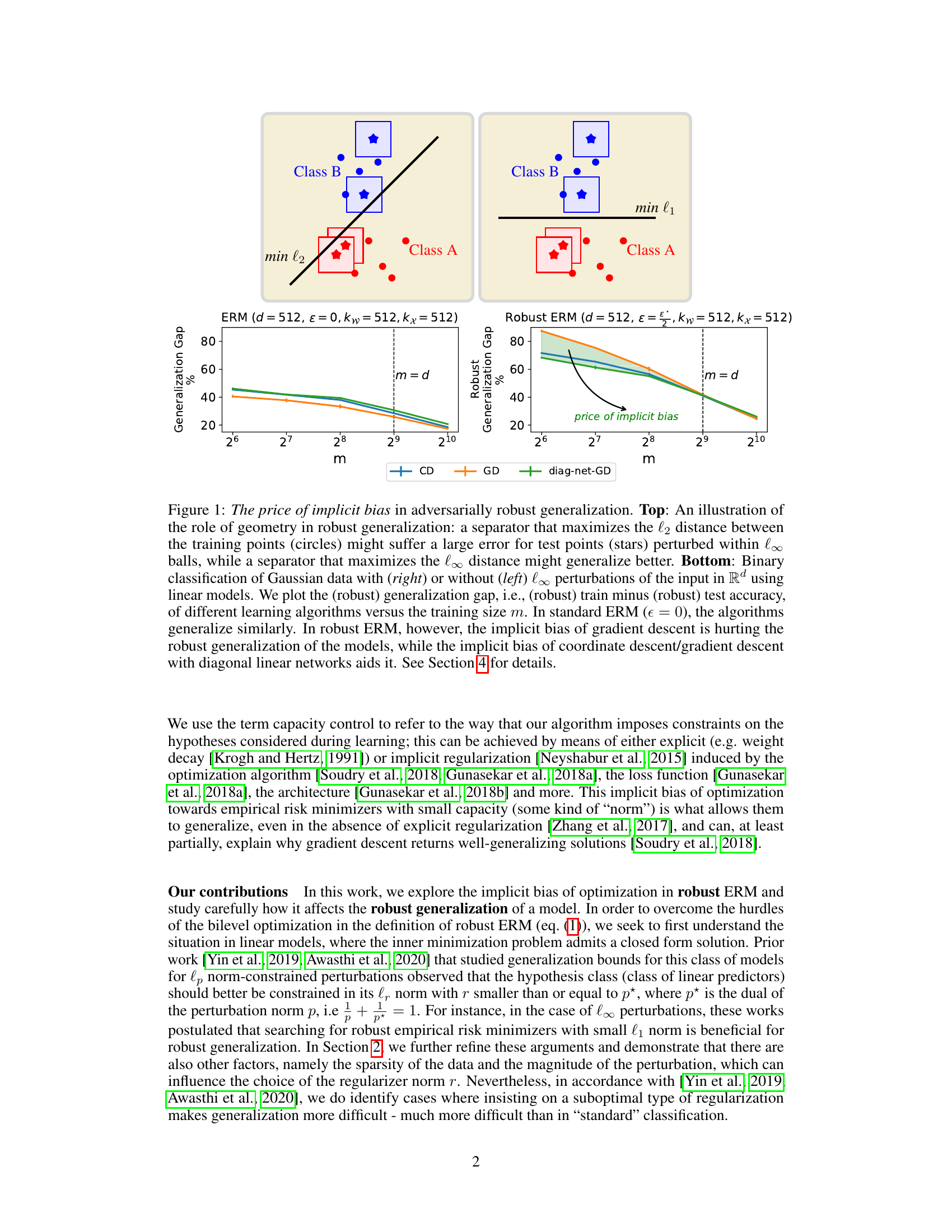

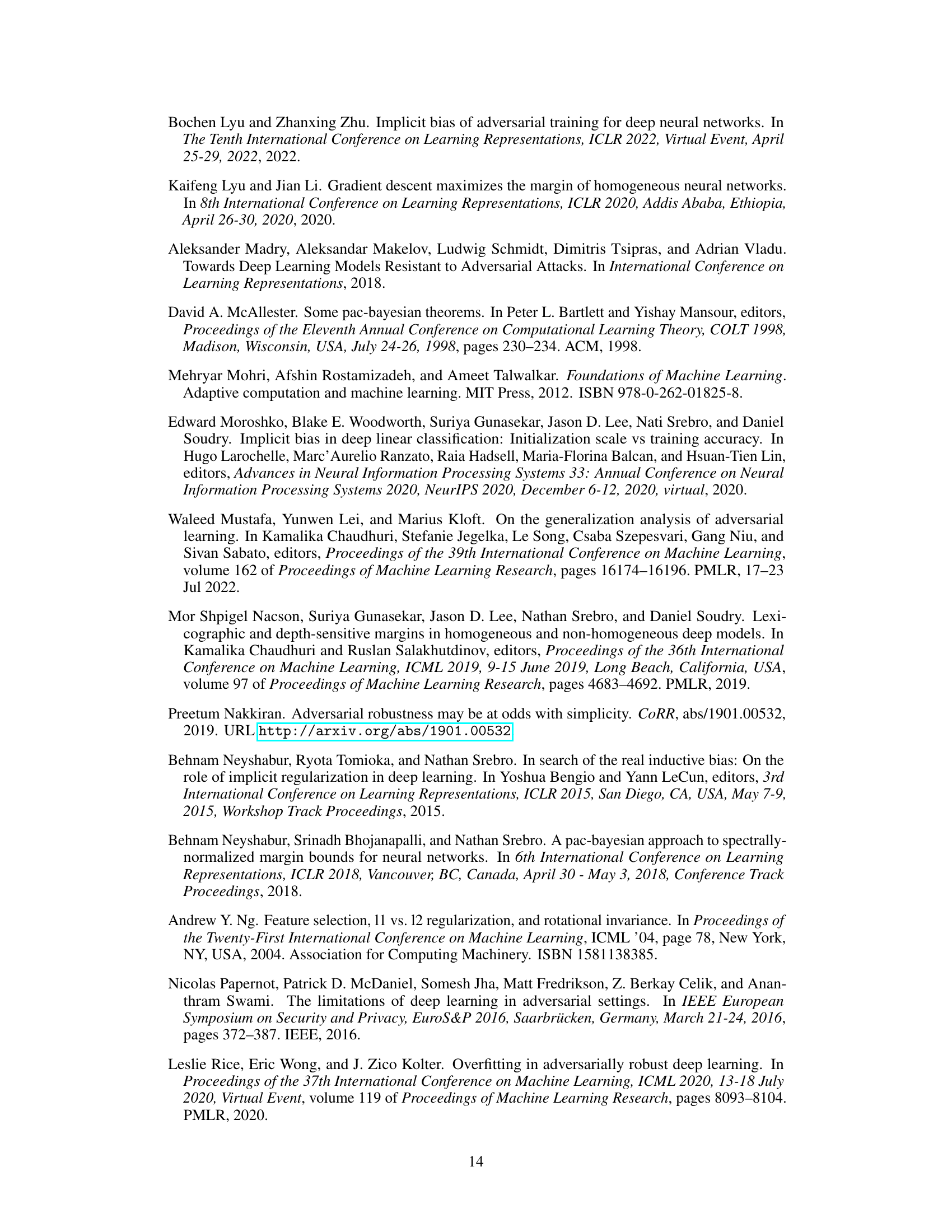

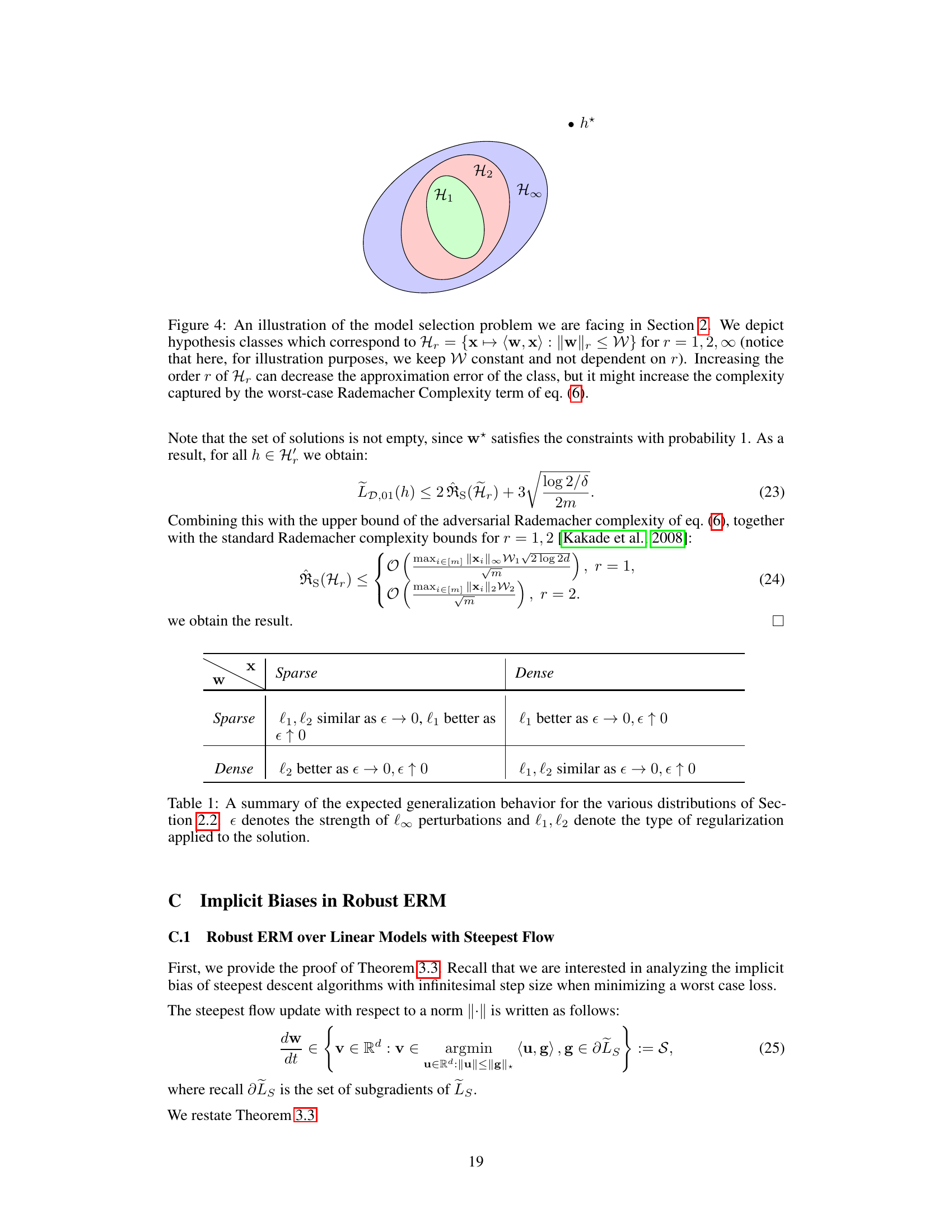

🔼 This table summarizes how different types of regularization (l1 and l2) affect generalization performance under various data sparsity conditions (sparse or dense data and model weights) and perturbation magnitudes (ε). It shows that the optimal choice of regularization depends on these factors and the level of adversarial robustness desired.

read the caption

Table 1: A summary of the expected generalization behavior for the various distributions of Section 2.2. ε denotes the strength of l∞ perturbations and l₁, l₂ denote the type of regularization applied to the solution.

In-depth insights#

Implicit Bias Price#

The concept of “Implicit Bias Price” in the context of adversarially robust generalization highlights the trade-off between the benefits of implicit regularization and the robustness of a model. While implicit bias from optimization algorithms can naturally promote generalization in standard machine learning, it can hinder robust generalization when adversarial perturbations are introduced. The paper argues that the optimization algorithm’s inherent bias might not align with the requirements for robustness imposed by the threat model. This misalignment leads to suboptimal generalization, incurring a cost or “price” in robustness. The price is paid in terms of reduced test accuracy, potentially due to overfitting or model misspecification. The study investigates how this cost manifests in both linear and deep neural network models, suggesting that the choice of optimization algorithm and network architecture significantly influence the implicit bias and its impact on robust generalization. Therefore, carefully considering the optimization algorithm and model design is crucial to minimize the implicit bias price and improve the robustness of machine learning models. This work explores novel ways to mitigate the negative impact of implicit biases, offering valuable insights into the robust generalization problem.

Robust Generalization#

The concept of “robust generalization” in machine learning focuses on the ability of a model to maintain high accuracy not just on the training data but also on unseen data that may differ from the training data, especially in presence of noise or adversarial attacks. Robust generalization is crucial because models are intended to function in real-world scenarios, which are rarely perfectly controlled. The paper investigates how implicit bias during optimization in robust ERM (empirical risk minimization) affects this critical capability. Implicit bias, the unanticipated regularization effects of optimization algorithms, can significantly influence whether a model generalizes robustly or not. The study reveals how this bias, driven by the choice of algorithm or model architecture, can either help or hinder robust generalization, highlighting a delicate interplay between optimization and generalization performance in adversarial settings. Understanding and controlling this implicit bias is thus paramount for developing truly robust and generalizable machine learning systems. The paper explores this challenge in linear models and then extends its observations to deep neural networks, offering crucial insights into this important and complex area.

Linear Model Analysis#

A thorough linear model analysis within a research paper would delve into the impact of implicit bias on robust generalization. It would likely begin by establishing theoretical generalization bounds for adversarially robust classification in linear models, focusing on how different regularization strategies (e.g., L1, L2) affect performance under various perturbation norms (e.g., L∞). Key theoretical findings might show how the choice of regularization interacts with the geometry of the data and perturbation set to impact generalization. The analysis should then demonstrate through simulations how optimization algorithms (like gradient descent and coordinate descent) interact with these regularization effects, leading to specific predictions about which algorithm and regularization combination would work best under which conditions. The simulation results should ideally showcase not only how different algorithms affect robustness but also how that impact varies depending on data properties, such as sparsity. A key takeaway would be the identification of a ‘price of implicit bias’, highlighting instances where the optimization algorithm’s implicit bias negatively impacts generalization due to misalignment with the threat model. This provides a critical link between the geometry of the optimization process, the choice of regularizer, and robust generalization performance in linear settings.

Network Experiments#

In the hypothetical ‘Network Experiments’ section, I’d expect a thorough evaluation of the proposed methods on various network architectures. This would likely involve experiments on fully connected networks (FCNs), convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and potentially graph neural networks (GNNs), depending on the paper’s focus. The experiments should investigate how the implicit bias interacts with different network depths, widths, and activation functions. Robustness to adversarial attacks would be a key metric, likely measured with different perturbation strategies and threat models. The authors would need to demonstrate that their insights on implicit bias are not limited to simple linear models but generalize to more complex network settings. Comparisons against standard training methods would be crucial, highlighting improvements in both accuracy and robustness. A careful analysis of the results, possibly including visualization techniques to illustrate the impact of the implicit bias, would help solidify the findings. Finally, consideration should be given to the computational cost of the proposed methods, particularly in the context of large-scale networks.

Future Work#

The paper’s exploration of implicit bias in robust empirical risk minimization (ERM) opens several avenues for future work. A primary direction is extending the theoretical analysis beyond linear models to encompass more complex architectures like deep neural networks. This would require developing new theoretical tools to handle the challenges posed by non-linearity and high dimensionality. Furthermore, investigating the interaction between different optimization algorithms and the choice of regularization is crucial. The authors’ empirical findings suggest that algorithm-induced bias significantly affects robust generalization, but a deeper understanding of this interplay is needed. Another important direction is to investigate the effects of data characteristics, such as sparsity and dimensionality, on the interplay between implicit bias and robust generalization. The current work touches upon these effects in the context of linear models; however, similar analysis for more complex models is essential to create a comprehensive understanding. Finally, developing robust ERM training techniques that effectively control implicit bias, perhaps through novel optimization algorithms or architectural designs, would be a significant contribution. The paper highlights the negative consequences of misaligned bias and threat models; future research could focus on mitigating these effects.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure shows the impact of implicit bias on adversarially robust generalization. The top panel illustrates how different separators (maximizing l2 vs. l∞ distance) affect generalization under l∞ perturbations. The bottom panel compares the generalization gap (difference between training and test accuracy) of different optimization algorithms (gradient descent, coordinate descent, and gradient descent with diagonal networks) for linear models with and without l∞ perturbations. It demonstrates that the choice of optimization algorithm and network architecture significantly impact robust generalization, highlighting the ‘price of implicit bias’.

read the caption

Figure 1: The price of implicit bias in adversarially robust generalization. Top: An illustration of the role of geometry in robust generalization: a separator that maximizes the l2 distance between the training points (circles) might suffer a large error for test points (stars) perturbed within l∞ balls, while a separator that maximizes the lo distance might generalize better. Bottom: Binary classification of Gaussian data with (right) or without (left) l∞ perturbations of the input in Rd using linear models. We plot the (robust) generalization gap, i.e., (robust) train minus (robust) test accuracy, of different learning algorithms versus the training size m. In standard ERM (€ = 0), the algorithms generalize similarly. In robust ERM, however, the implicit bias of gradient descent is hurting the robust generalization of the models, while the implicit bias of coordinate descent/gradient descent with diagonal linear networks aids it. See Section 4 for details.

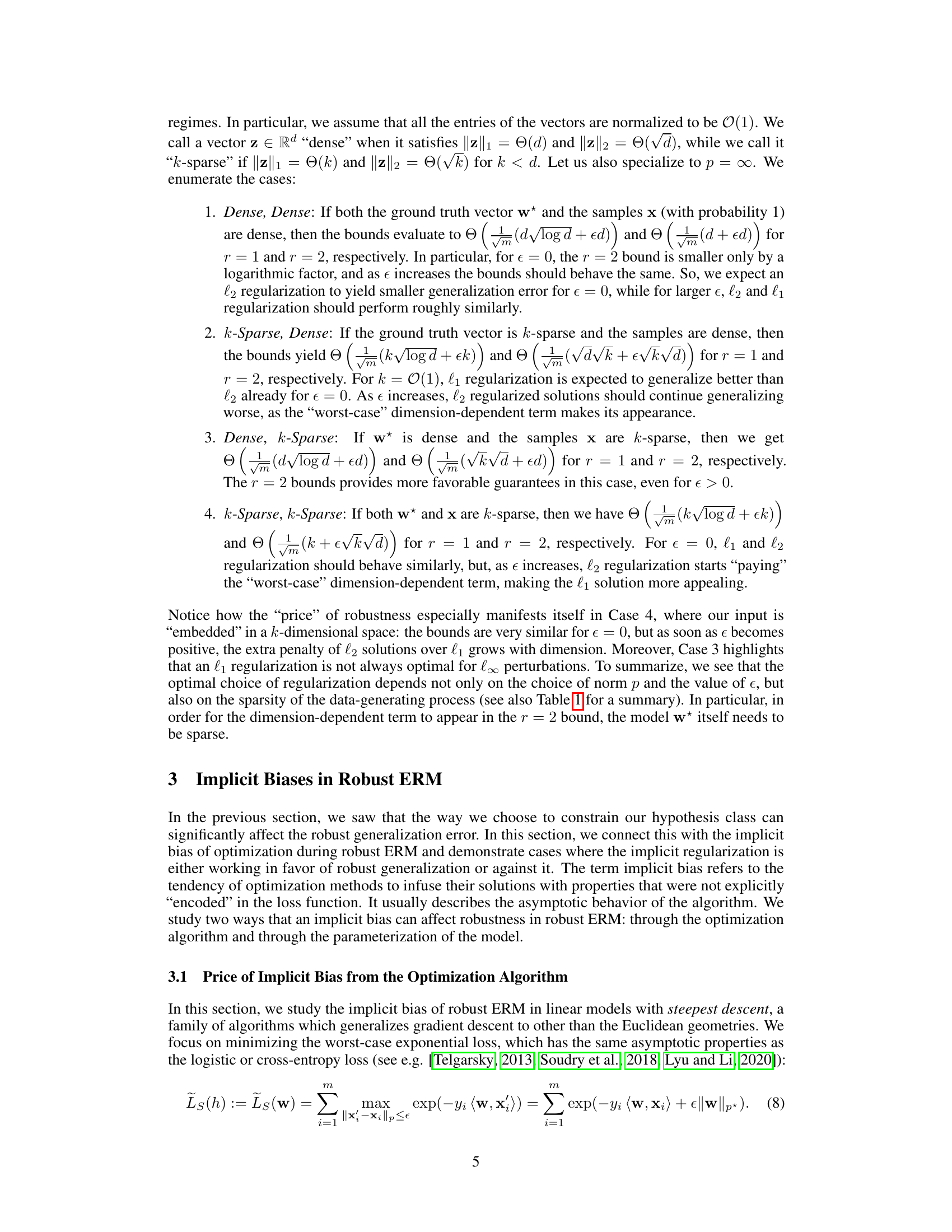

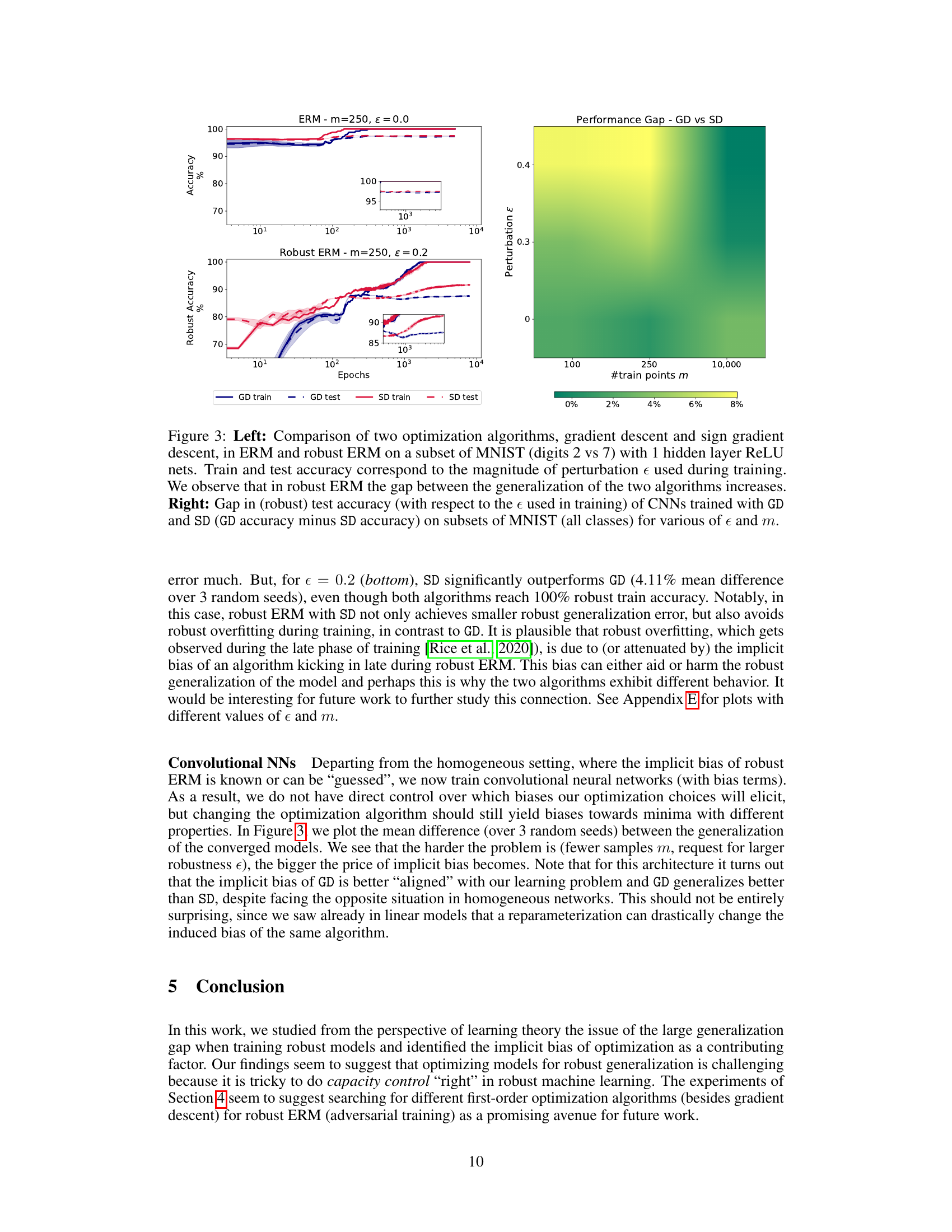

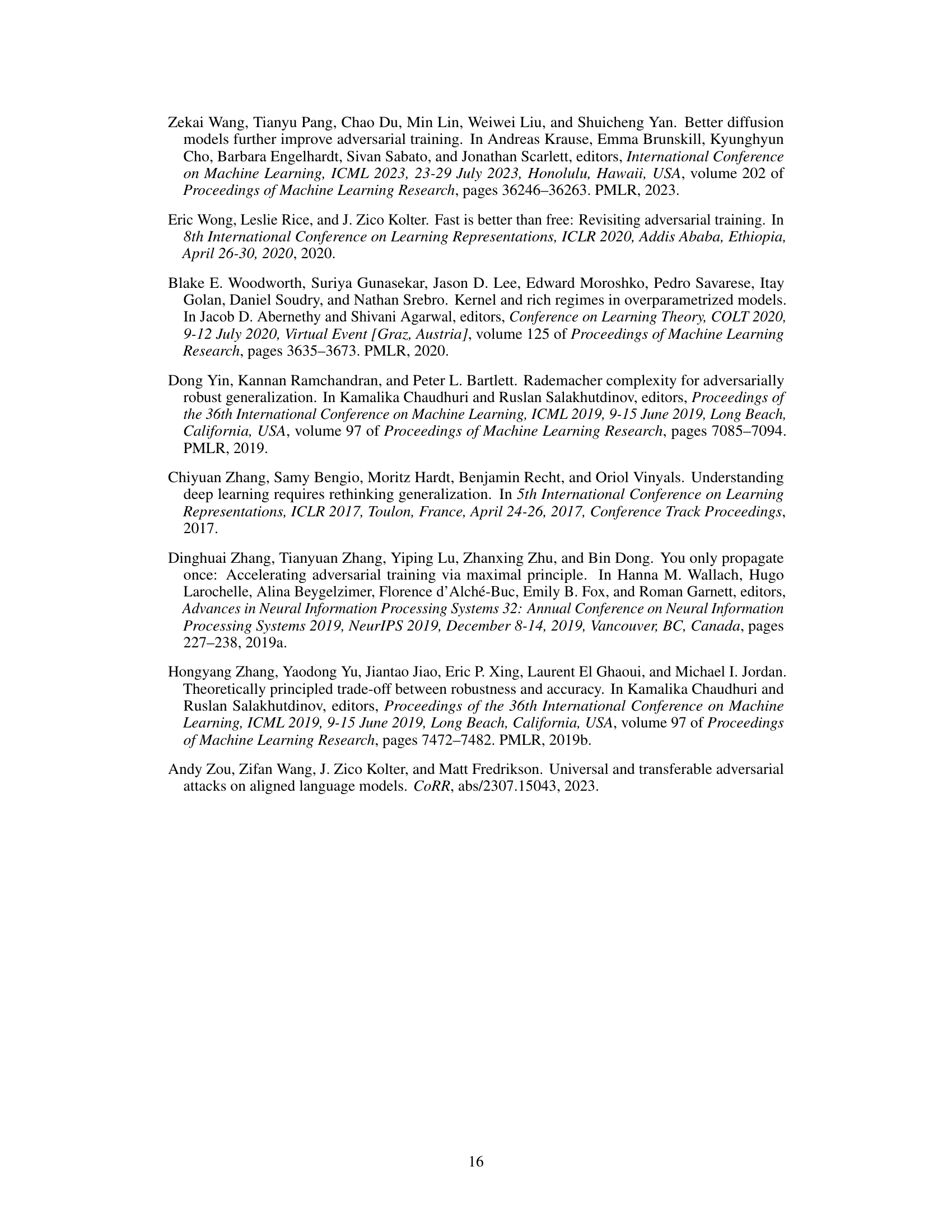

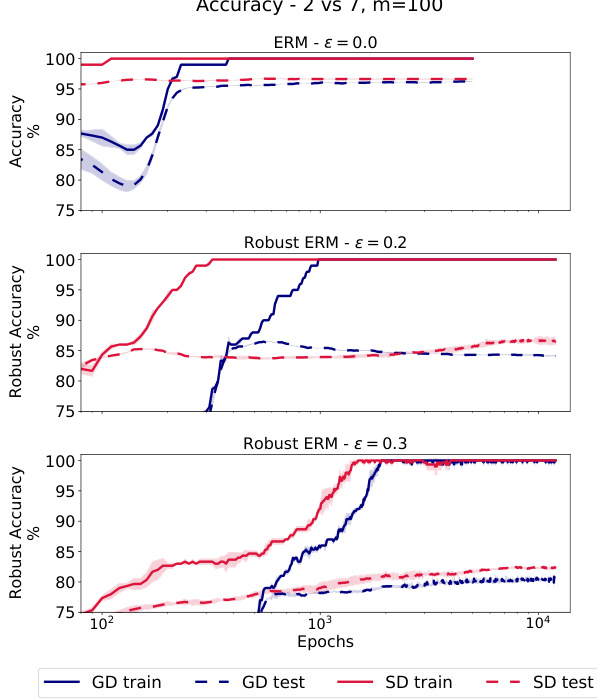

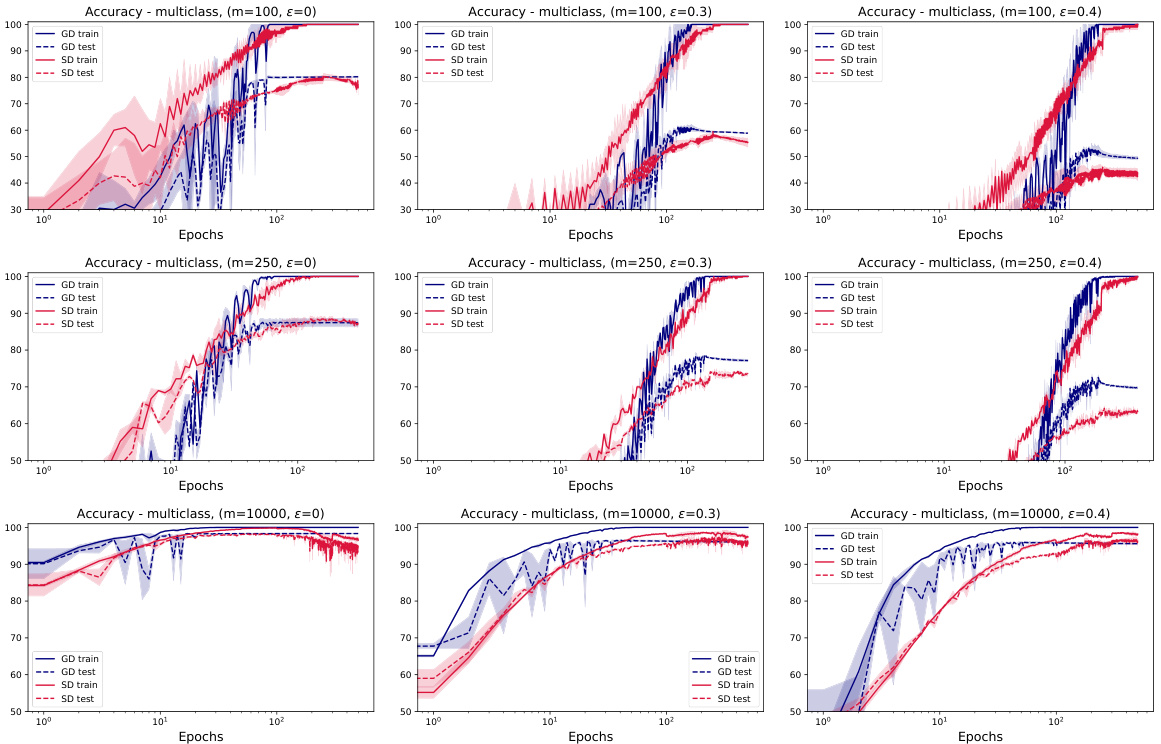

🔼 This figure compares the performance of gradient descent and sign gradient descent on a subset of MNIST. The left panel shows the training and testing accuracy for both algorithms under ERM and robust ERM, demonstrating that the gap in generalization widens for robust ERM. The right panel visualizes the difference in test accuracy between the two algorithms, under different levels of perturbation and training set sizes, confirming that the gap is more pronounced for robust ERM. The experiments utilize ReLU networks with one hidden layer for the left panel and convolutional neural networks for the right.

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: Comparison of two optimization algorithms, gradient descent and sign gradient descent, in ERM and robust ERM on a subset of MNIST (digits 2 vs 7) with 1 hidden layer ReLU nets. Train and test accuracy correspond to the magnitude of perturbation e used during training. We observe that in robust ERM the gap between the generalization of the two algorithms increases. Right: Gap in (robust) test accuracy (with respect to the e used in training) of CNNs trained with GD and SD (GD accuracy minus SD accuracy) on subsets of MNIST (all classes) for various of e and m.

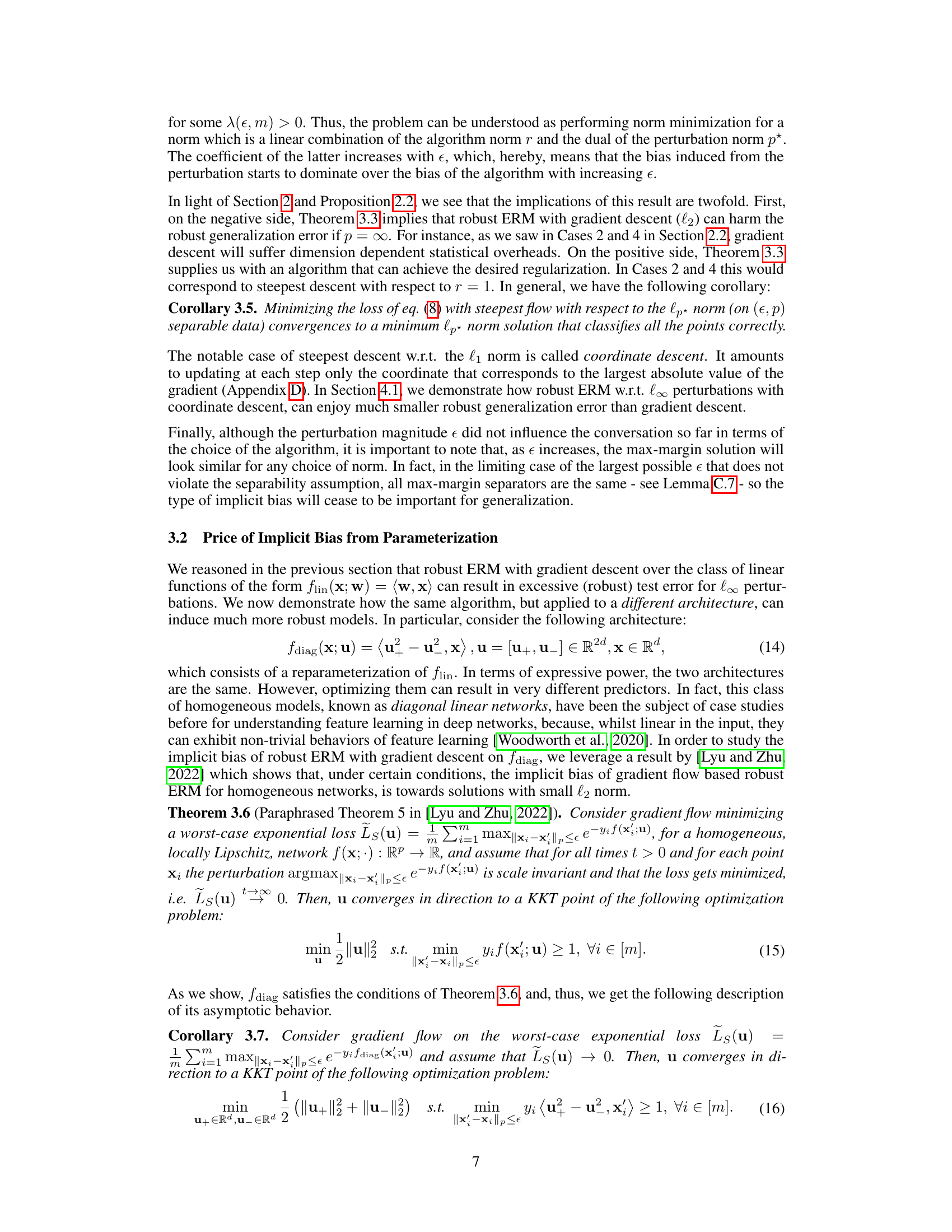

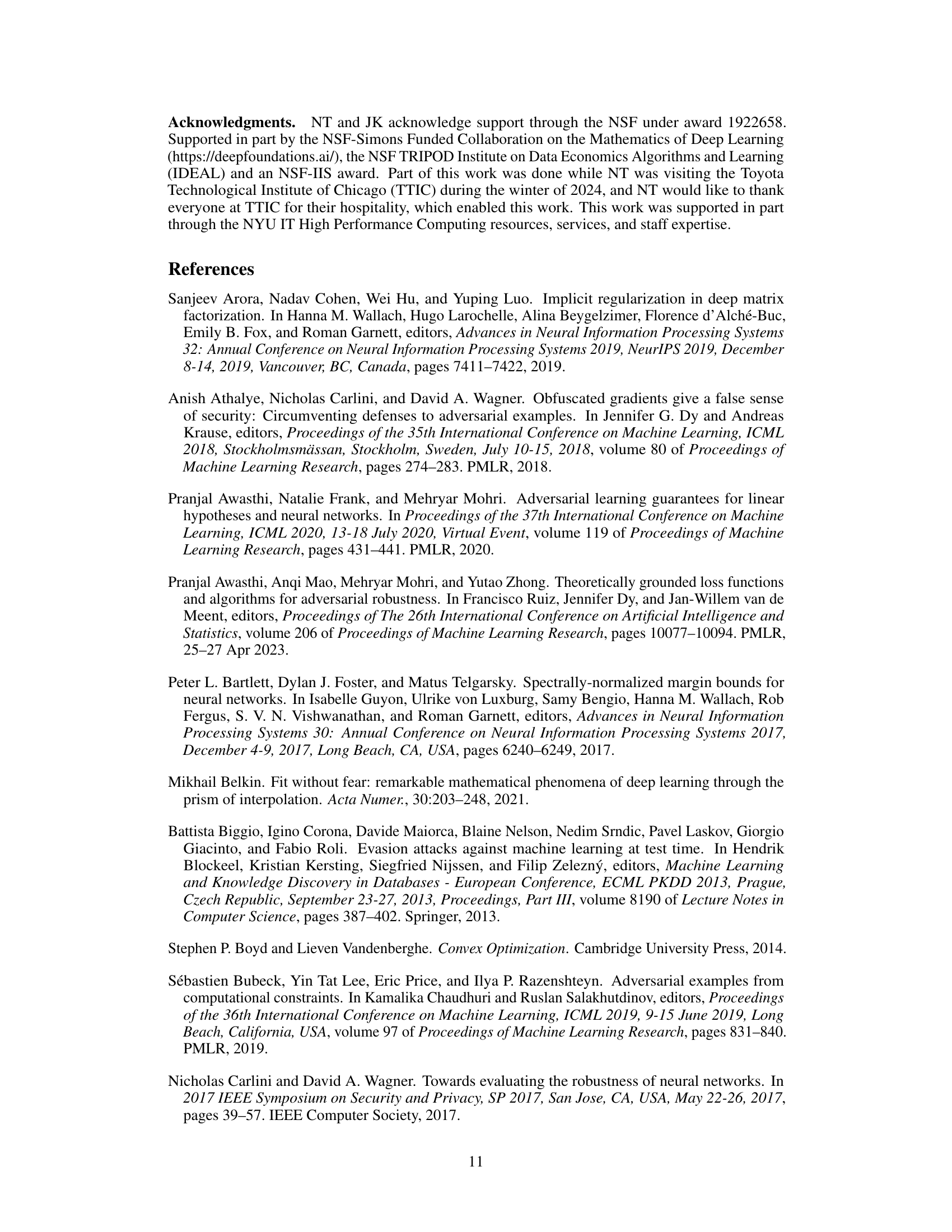

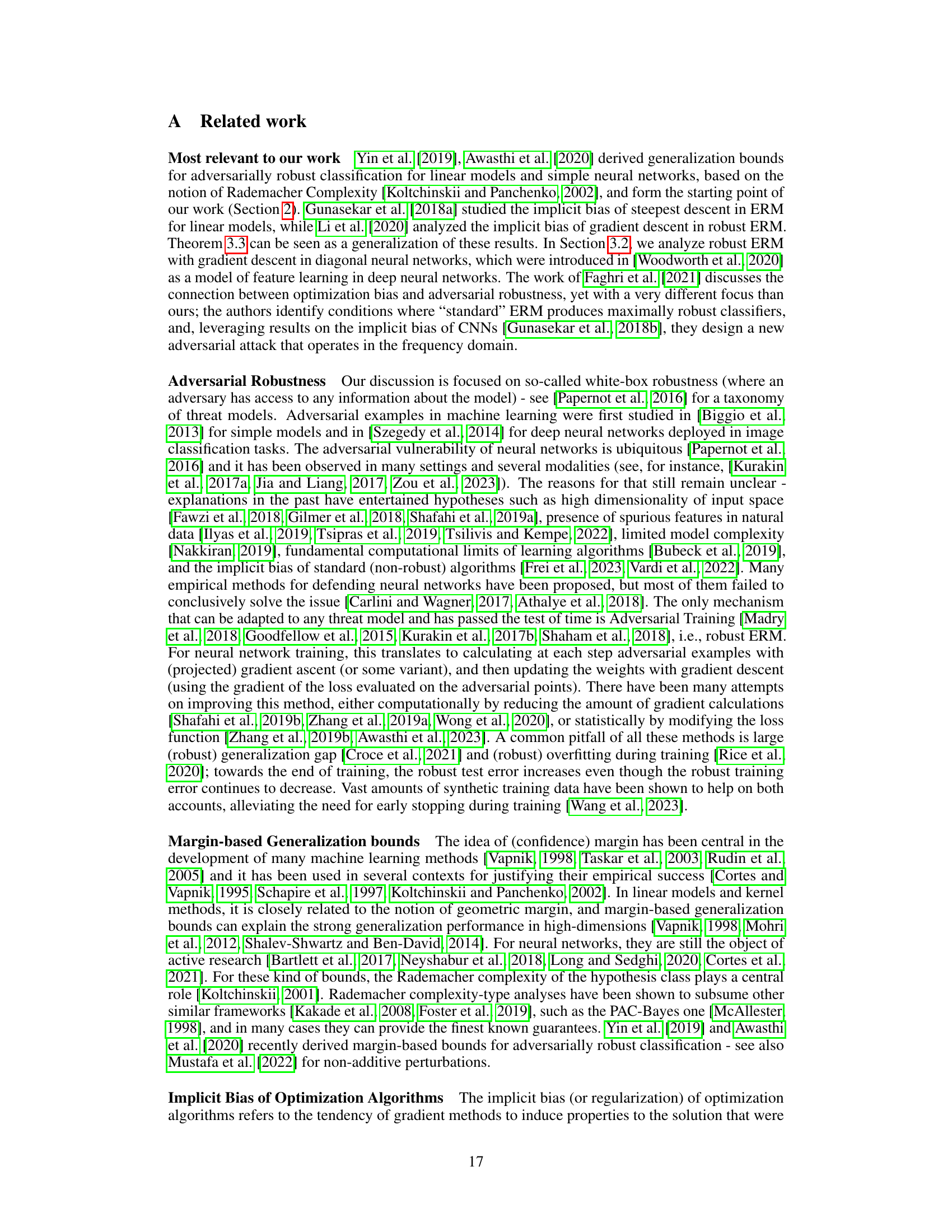

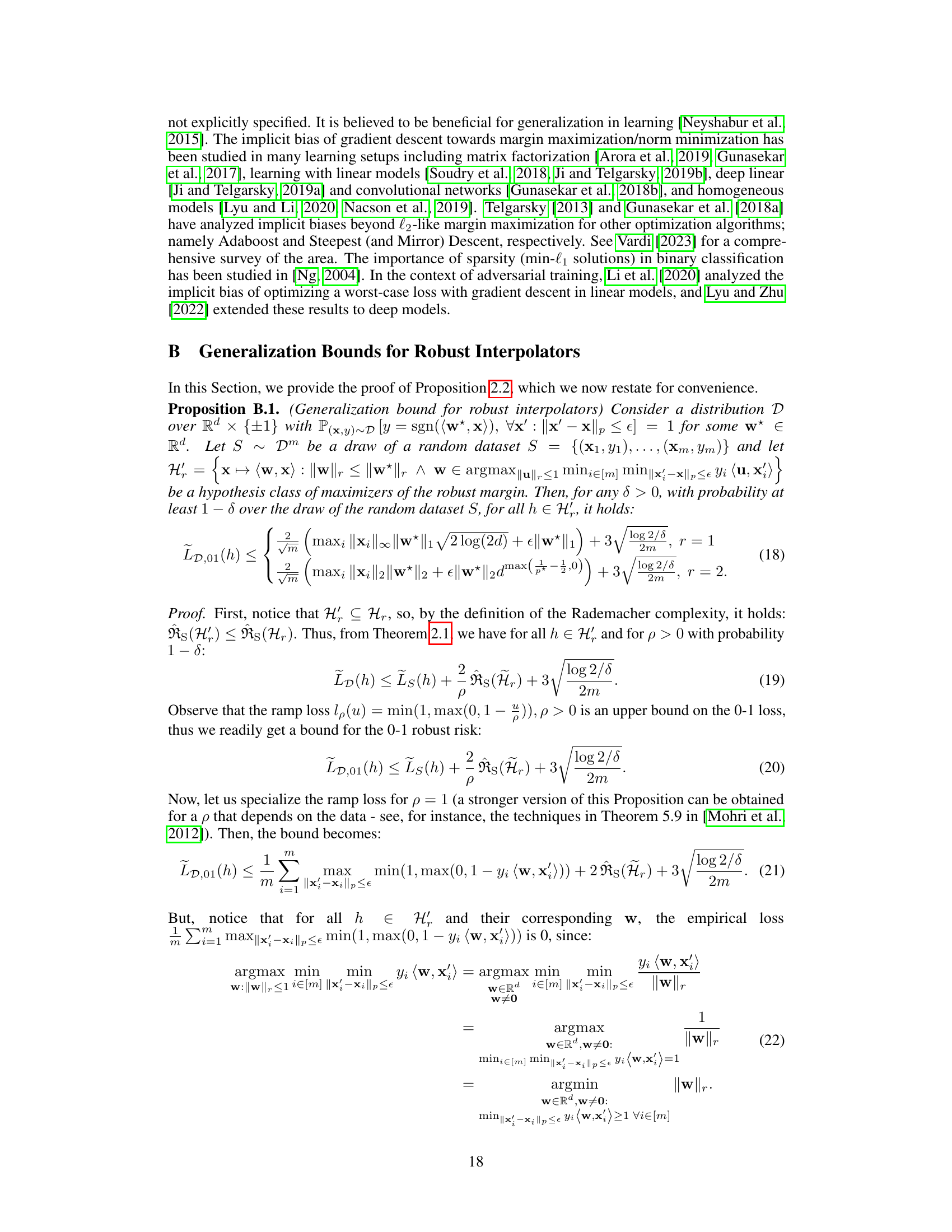

🔼 This figure illustrates the model selection problem discussed in Section 2 of the paper. It shows three hypothesis classes, H1, H2, and H∞, represented by ellipses of increasing size. The size of the ellipse represents the complexity of the hypothesis class, which relates to generalization ability. A smaller, less complex class (H1) may have a larger approximation error but better generalization, while a larger class (H∞) may have smaller approximation error but worse generalization. The optimal hypothesis class balances approximation error and complexity for robust generalization. The figure highlights the trade-off between reducing approximation error and controlling complexity during model selection for robust generalization.

read the caption

Figure 4: An illustration of the model selection problem we are facing in Section 2. We depict hypothesis classes which correspond to Hr = {x ↔ (w,x) : ||w||r < W} for r = 1,2, ∞ (notice that here, for illustration purposes, we keep W constant and not dependent on r). Increasing the order r of Hr can decrease the approximation error of the class, but it might increase the complexity captured by the worst-case Rademacher Complexity term of eq. (6).

🔼 This figure explores the impact of implicit bias on robust generalization. The top panel illustrates how different distance metrics (l2 vs. l∞) affect the generalization ability of a model under adversarial perturbations. The bottom panel shows the generalization gap (difference between training and testing accuracy) for various optimization algorithms (gradient descent, coordinate descent, and gradient descent on diagonal linear networks) in standard and robust ERM settings. It demonstrates that the implicit bias of the optimization algorithm significantly influences robustness and that this impact can differ based on the algorithm and network architecture.

read the caption

Figure 1: The price of implicit bias in adversarially robust generalization. Top: An illustration of the role of geometry in robust generalization: a separator that maximizes the l2 distance between the training points (circles) might suffer a large error for test points (stars) perturbed within l∞ balls, while a separator that maximizes the l∞ distance might generalize better. Bottom: Binary classification of Gaussian data with (right) or without (left) l∞ perturbations of the input in Rd using linear models. We plot the (robust) generalization gap, i.e., (robust) train minus (robust) test accuracy, of different learning algorithms versus the training size m. In standard ERM (€ = 0), the algorithms generalize similarly. In robust ERM (€ > 0), however, the implicit bias of gradient descent is hurting the robust generalization of the models, while the implicit bias of coordinate descent/gradient descent with diagonal linear networks aids it. See Section 4 for details.

🔼 This figure shows the impact of implicit bias on robust generalization. The top part illustrates how different geometric separators (maximizing l2 vs. l∞ distance) affect robustness to l∞ perturbations. The bottom part presents experimental results comparing different optimization algorithms (gradient descent, coordinate descent, and gradient descent with diagonal linear networks) on binary classification tasks with and without l∞ adversarial perturbations. It demonstrates how the choice of optimization algorithm and network architecture significantly impacts robust generalization performance by affecting the implicit bias of the optimization process.

read the caption

Figure 1: The price of implicit bias in adversarially robust generalization. Top: An illustration of the role of geometry in robust generalization: a separator that maximizes the l2 distance between the training points (circles) might suffer a large error for test points (stars) perturbed within l∞ balls, while a separator that maximizes the l∞ distance might generalize better. Bottom: Binary classification of Gaussian data with (right) or without (left) l∞ perturbations of the input in Rd using linear models. We plot the (robust) generalization gap, i.e., (robust) train minus (robust) test accuracy, of different learning algorithms versus the training size m. In standard ERM (€ = 0), the algorithms generalize similarly. In robust ERM (€ > 0), however, the implicit bias of gradient descent is hurting the robust generalization of the models, while the implicit bias of coordinate descent/gradient descent with diagonal linear networks aids it. See Section 4 for details.

🔼 The figure compares the performance of gradient descent (GD) and sign gradient descent (SD) on a subset of the MNIST dataset (digits 2 vs 7) for both standard ERM (ε=0) and robust ERM (ε>0). The left panel shows training and test accuracy curves for both algorithms under different perturbation levels. The right panel shows the difference in test accuracy between GD and SD for various dataset sizes (m) and perturbation levels (ε).

read the caption

Figure 3: Left: Comparison of two optimization algorithms, gradient descent and sign gradient descent, in ERM and robust ERM on a subset of MNIST (digits 2 vs 7) with 1 hidden layer ReLU nets. Train and test accuracy correspond to the magnitude of perturbation ε used during training. We observe that in robust ERM the gap between the generalization of the two algorithms increases. Right: Gap in (robust) test accuracy (with respect to the ε used in training) of CNNs trained with GD and SD (GD accuracy minus SD accuracy) on subsets of MNIST (all classes) for various of ε and m.

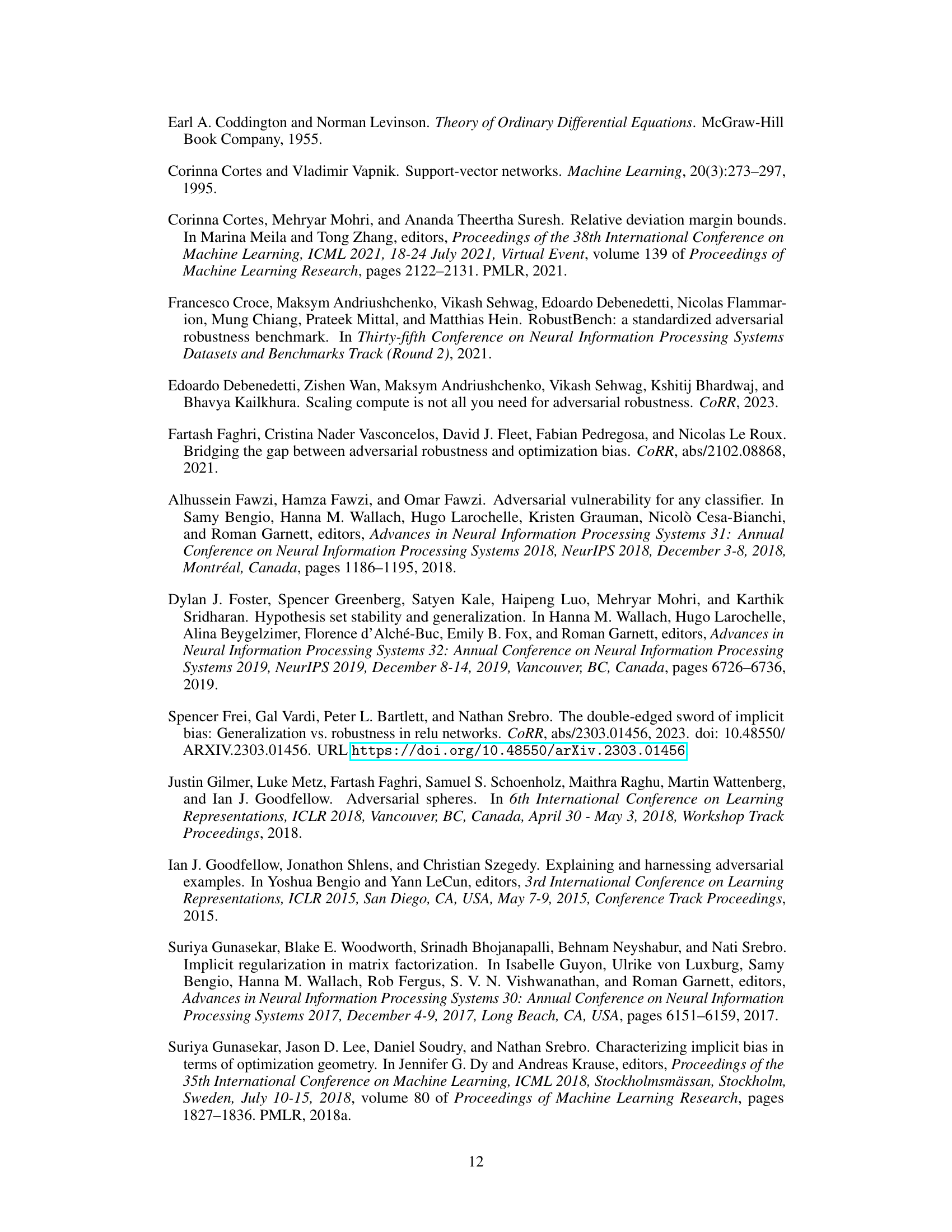

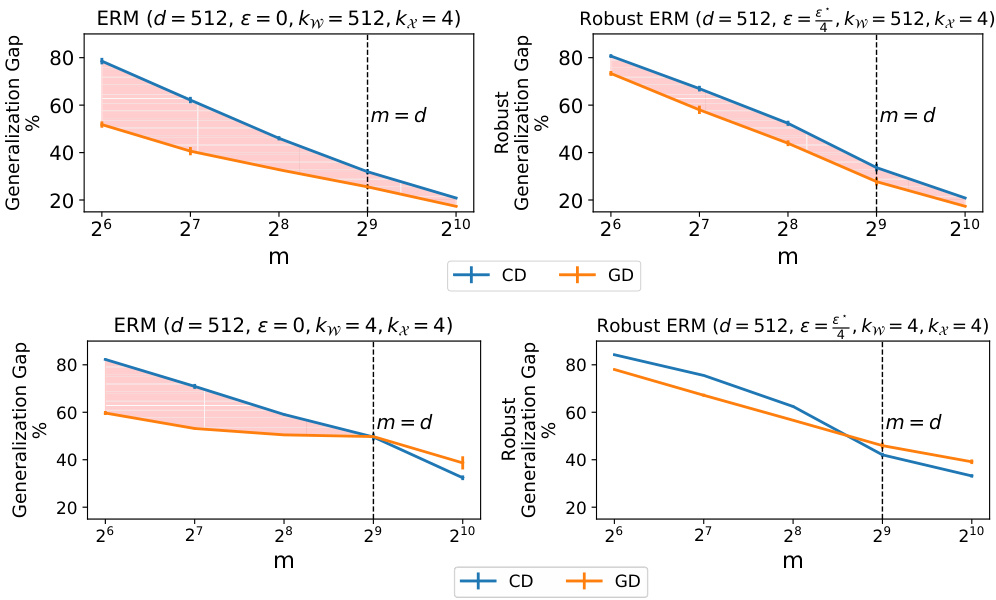

🔼 This figure shows the impact of implicit bias in adversarially robust generalization using linear models. The left panel illustrates the (robust) generalization gap (difference between training and testing accuracy) for three algorithms (Coordinate Descent, Gradient Descent, and Gradient Descent with diagonal networks) under different training set sizes, with and without l∞ input perturbations. The right panel shows the average improvement of Coordinate Descent over Gradient Descent in terms of generalization gap across various teacher and data sparsity levels and perturbation magnitudes.

read the caption

Figure 2: Left: Binary classification of data coming from a sparse teacher w* and dense x, with (bottom) or without (top) l∞ perturbations of the input in Rd using linear models. We plot the (robust) generalization gap, i.e., (robust) train minus (robust) test accuracy, of different learning algorithms versus the training size m. For robust ERM, e is set to be of the largest permissible value e*. The gap between the methods grows when we pass from ERM to robust ERM. Right: Average benefit of CD over GD (in terms of generalization gap) for different values of teacher sparsity kw, data sparsity kx and magnitude of l∞ perturbation e.

Full paper#