TL;DR#

Traditional information retrieval (IR) systems often use large language models (LLMs) as components, leading to knowledge silos and suboptimal performance. LLMs’ potential for deep integration across the entire IR pipeline remains largely untapped. This separation restricts synergy and hinders fully leveraging LLMs’ capabilities.

Self-Retrieval addresses these issues by unifying indexing, retrieval, and reranking within one LLM. This novel architecture achieves superior performance through self-supervised corpus internalization, constrained passage generation, and self-assessment reranking. Experiments on multiple datasets demonstrate that Self-Retrieval significantly outperforms existing methods in both passage-level and document-level retrieval tasks, also enhancing downstream tasks like retrieval-augmented generation.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in information retrieval and large language models because it demonstrates a novel end-to-end architecture that significantly improves retrieval performance and opens up new avenues for research in LLM-driven applications. It challenges the traditional pipeline approach and highlights the potential of a fully integrated LLM-based system for future advancements in IR.

Visual Insights#

🔼 This figure illustrates the Self-Retrieval framework, which is an end-to-end information retrieval architecture. It consists of three main stages: indexing, retrieval, and reranking. The indexing stage uses self-supervised learning to embed the corpus into the LLM. The retrieval stage uses constrained decoding to generate relevant passages from the corpus based on a given query. The reranking stage uses self-assessment scoring to evaluate the relevance of the retrieved passages, allowing for more precise ranking. The figure visually represents the flow of data through each component.

read the caption

Figure 1: The Self-Retrieval framework consists of three key components: (1) corpus indexing through self-supervised learning, (2) passage generation via constrained decoding, (3) passage ranking using self-assessment scoring.

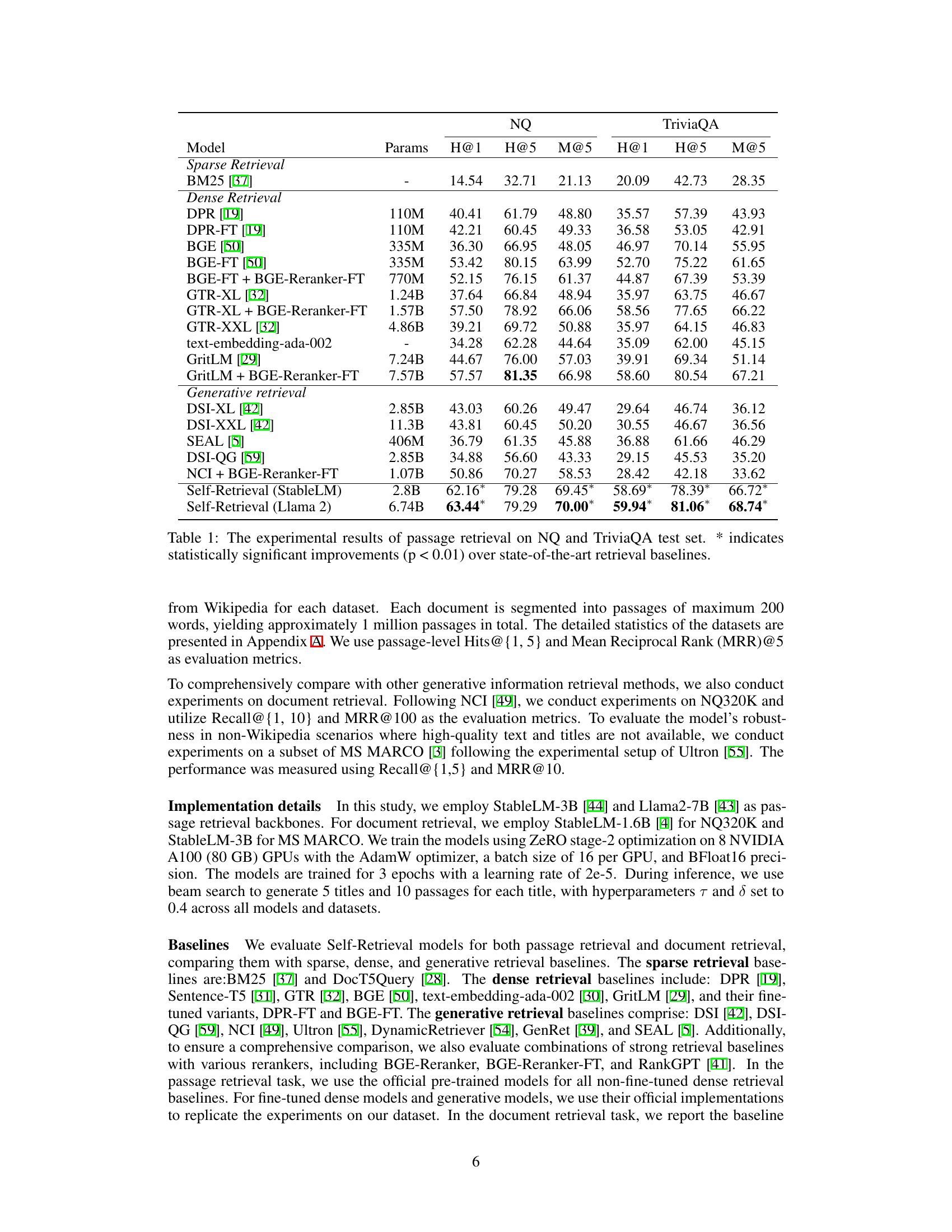

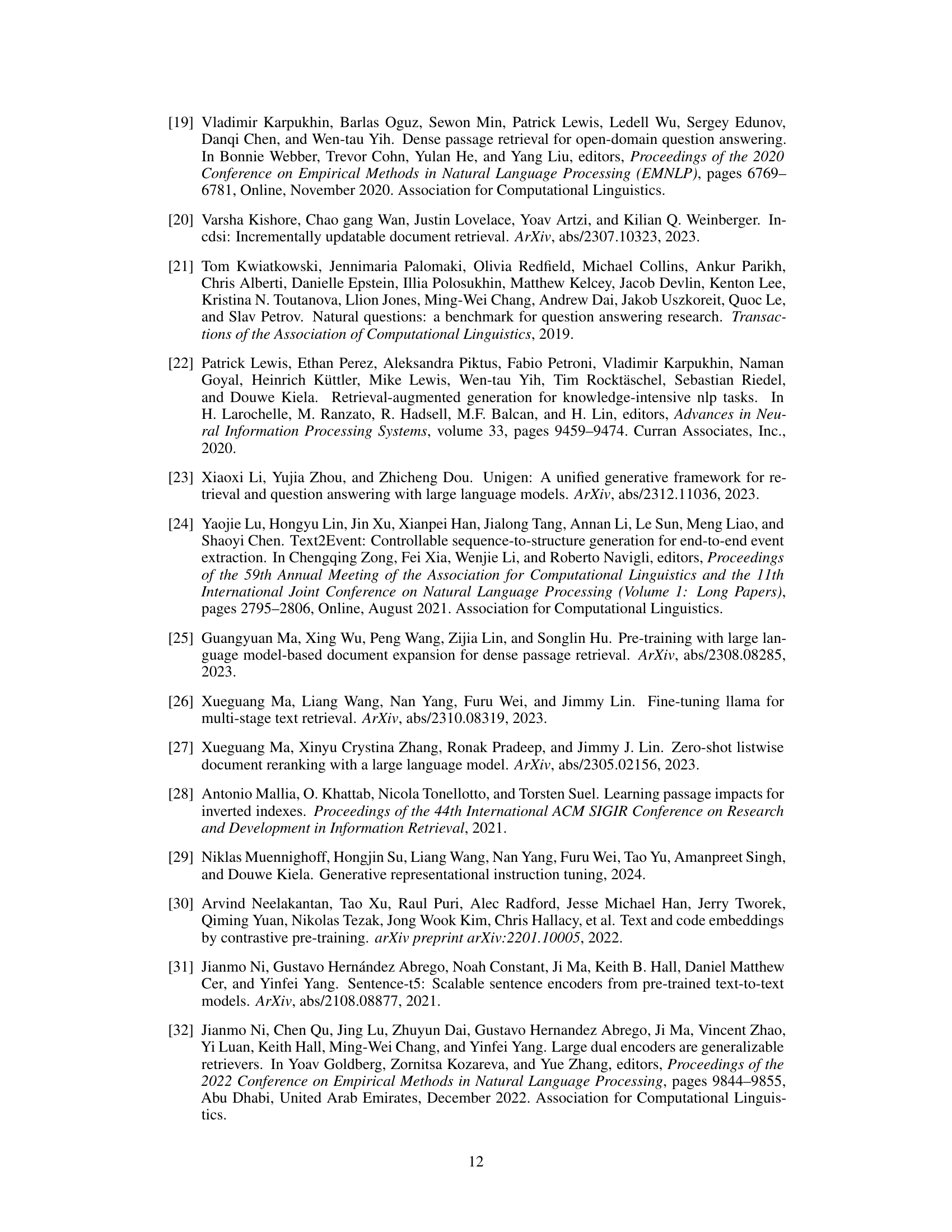

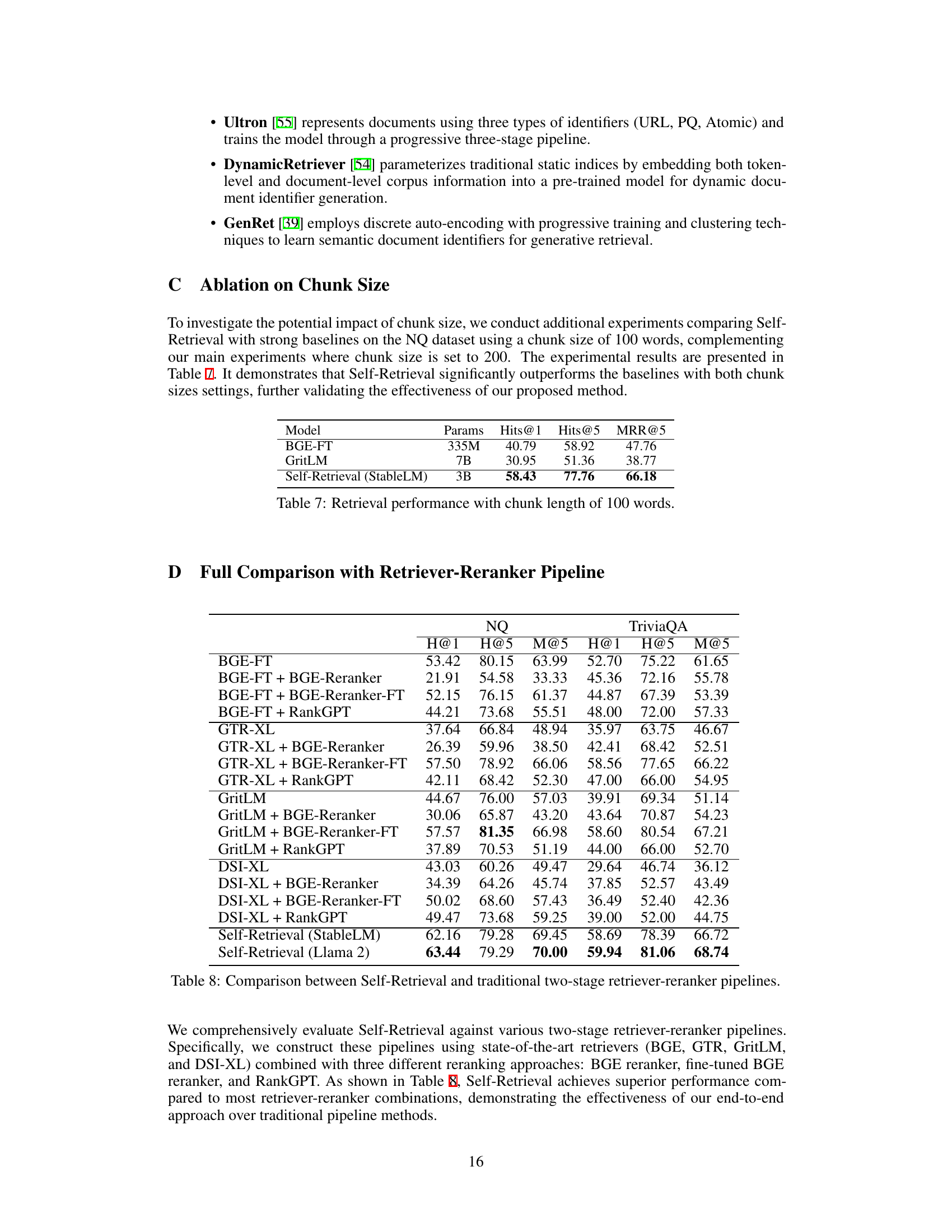

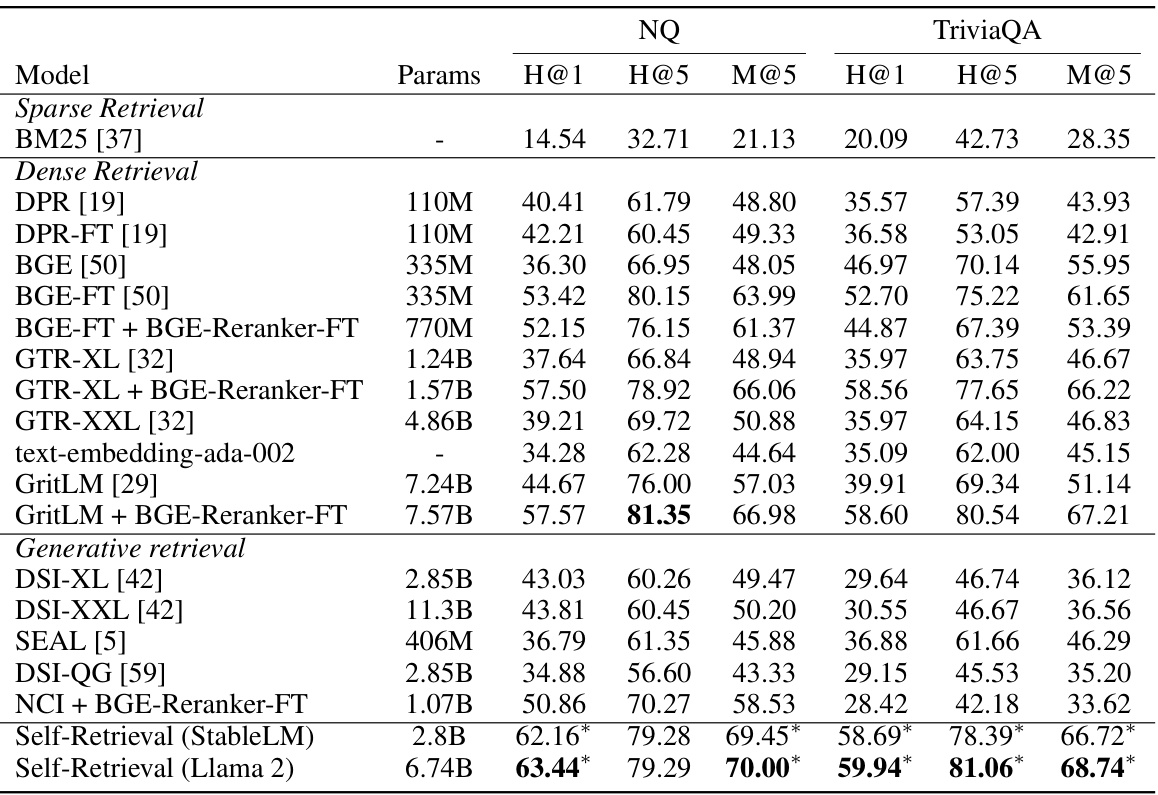

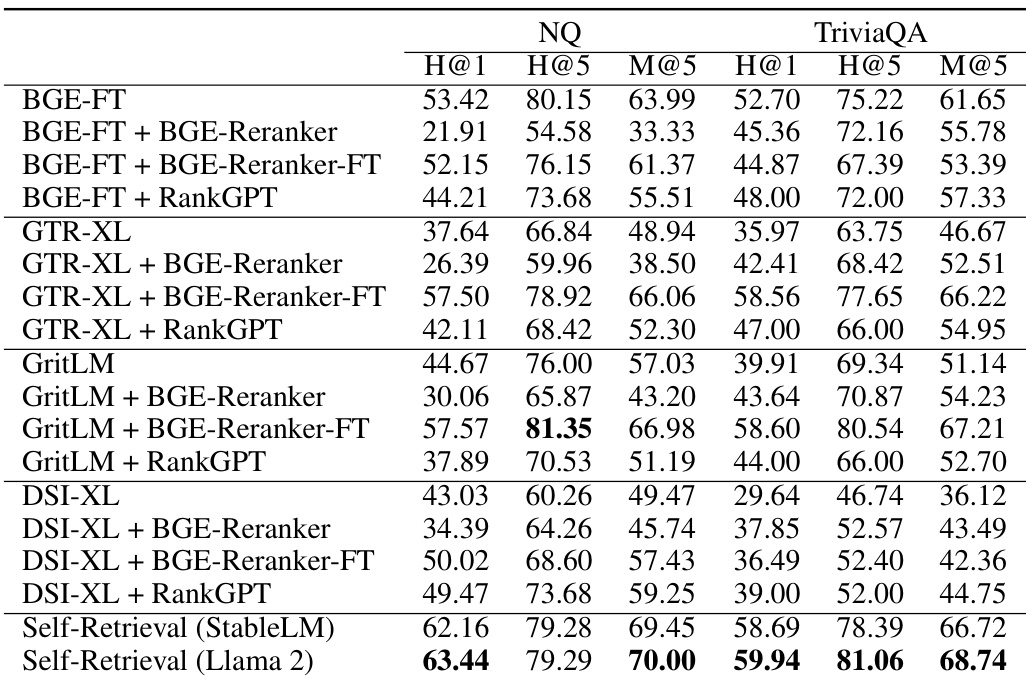

🔼 This table presents the performance of Self-Retrieval and various baseline models on two passage retrieval tasks: Natural Questions (NQ) and TriviaQA. The results are evaluated using Hits@1, Hits@5, and Mean Average Precision@5 (MAP@5) metrics. Self-Retrieval significantly outperforms all baselines, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed method. The asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant improvements (p<0.01).

read the caption

Table 1: The experimental results of passage retrieval on NQ and TriviaQA test set. * indicates statistically significant improvements (p < 0.01) over state-of-the-art retrieval baselines.

In-depth insights#

LLM-driven IR#

LLM-driven IR represents a paradigm shift in information retrieval, leveraging the power of large language models (LLMs) to redefine how we search and access information. Instead of treating LLMs as mere components within traditional IR pipelines, this approach integrates LLMs deeply into all stages of the process—from indexing and retrieval to reranking and answer generation. This allows for a more holistic and semantically rich understanding of queries and documents. A key advantage is the ability to overcome limitations of traditional keyword-based systems by capturing the contextual nuances of language. This facilitates a more natural language interaction, moving beyond exact keyword matching to understand the meaning and intent behind a query. However, challenges remain, including computational cost, potential biases inherited from LLMs, and the need for careful consideration of ethical implications related to data privacy and model transparency. The success of LLM-driven IR hinges on the ability to effectively embed and utilize the knowledge within LLMs while mitigating these inherent limitations. Future research will likely focus on optimizing efficiency, addressing bias, and ensuring responsible deployment of this powerful technology.

Self-Retrieval Arch#

A hypothetical “Self-Retrieval Arch” in a research paper would likely detail a novel information retrieval architecture. It would probably center on a large language model (LLM) that performs all aspects of retrieval end-to-end, eliminating the need for separate indexing, retrieval, and reranking components. This integrated approach would allow the LLM to learn directly from a corpus, leveraging its inherent capabilities in understanding, matching, and generating text. A key innovation would be the internalization of the corpus, perhaps using self-supervised learning to encode the knowledge directly within the LLM’s parameters. Retrieval would be framed as a text generation task, maybe using constrained decoding to ensure accuracy. The method would likely incorporate a self-assessment mechanism for reranking, where the LLM evaluates the relevance of retrieved passages. The architecture’s novelty would lie in its seamless integration and unified approach, potentially leading to significant improvements in efficiency and overall retrieval performance. Its success hinges on the LLM’s ability to manage and effectively utilize the immense volume of data during training and deployment. This differs from existing pipeline architectures by eliminating the bottlenecks caused by separate modules and information transfer.

Corpus Internalization#

Corpus internalization, in the context of large language models (LLMs) for information retrieval, represents a paradigm shift from traditional indexing methods. Instead of relying on external indices or embeddings, the core idea is to encode the entire corpus directly into the LLM’s parameters through self-supervised learning. This approach offers several key advantages. First, it eliminates the need for separate indexing components, streamlining the retrieval process into a unified, end-to-end architecture. Second, it allows for richer semantic understanding as the LLM can access the corpus’s full context directly during retrieval, resulting in potentially more accurate and relevant results. Third, it enhances efficiency by eliminating the overhead of managing external indices, thereby making the system faster and more scalable. However, challenges exist. Internalizing a large corpus requires significant computational resources, making it resource intensive. Further research needs to address how to handle large and dynamic corpora effectively and how to control hallucinations and unwanted memorization. Nevertheless, this innovative approach has the potential to revolutionize information retrieval by leveraging the full power and capabilities of LLMs.

Constrained Decoding#

Constrained decoding, in the context of large language models (LLMs) for information retrieval, is a crucial technique to ensure that the model’s generated outputs align precisely with the existing corpus. Instead of freely generating text, constrained decoding restricts the model’s vocabulary at each step to only include tokens that are valid continuations within the corpus, effectively preventing the generation of hallucinations or fabricated information. This is typically achieved using a trie data structure built from the corpus, where each path represents a unique passage. This approach enforces semantic accuracy by ensuring that the generated text exists within the original dataset, which directly addresses a core challenge of relying solely on LLMs for retrieval: the risk of generating plausible but factually incorrect responses. The method’s effectiveness lies in its ability to maintain faithfulness to the source material while leveraging the power of LLMs for semantic understanding and generation. While computationally more expensive than unconstrained decoding, the benefits of ensuring factual accuracy outweigh the performance cost, especially for applications where reliability and precision are paramount. The use of a trie ensures efficiency by limiting the search space during decoding.

Future of Self-Retrieval#

The future of Self-Retrieval hinges on addressing its current limitations and capitalizing on its strengths. Scaling to larger corpora and more complex queries is crucial, potentially through techniques like efficient indexing mechanisms and hierarchical retrieval strategies. Improving efficiency is vital, requiring exploration of optimization techniques, model quantization, and hardware acceleration. Furthermore, research into more robust and reliable self-assessment scoring methods is necessary to enhance the accuracy of the reranking process. Investigating the integration of Self-Retrieval with other LLMs and exploring its applications in various downstream tasks, including multimodal retrieval and retrieval-augmented reasoning, will unlock its full potential. Finally, addressing potential ethical concerns related to bias and hallucination in LLMs integrated within Self-Retrieval will ensure responsible development and deployment of this powerful technology.

More visual insights#

More on figures

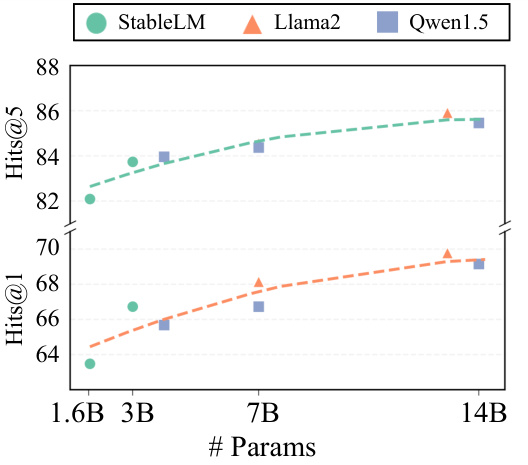

🔼 This figure shows the performance of Self-Retrieval using different sizes of language models (StableLM, Llama2, and Qwen-1.5) on the NQ dataset. The x-axis represents the number of parameters in the model, while the y-axis shows the Hits@1 and Hits@5 metrics. It demonstrates that larger models generally lead to improved performance in Self-Retrieval, showcasing the scaling benefits of the architecture.

read the caption

Figure 2: Impact of model capacity on Self-Retrieval performance.

🔼 This figure compares the reranking performance of three methods: the original retriever’s ranking, the ranking after applying the BGE-reranker, and the ranking produced by Self-Retrieval. The x-axis shows the different retriever models used (DPR-FT, SEAL, and GritLM). The y-axis represents the MRR@5 (Mean Reciprocal Rank at 5) score, indicating the effectiveness of reranking. The chart visually demonstrates the improvement in ranking achieved by both the BGE-reranker and, more significantly, by Self-Retrieval, across all three retriever models.

read the caption

Figure 3: Reranking performance comparison when processing top-100 passages.

🔼 This figure shows the scalability of Self-Retrieval and BGE-FT (a strong baseline) on two different datasets (NQ and TriviaQA) as the number of documents increases from 10k to 200k. It demonstrates how the retrieval performance (Hits@1 and Hits@5) changes with increasing corpus size for both models. The results indicate the robustness of Self-Retrieval even when dealing with significantly larger corpora.

read the caption

Figure 4: Scalability analysis of retrieval performance for Self-Retrieval and BGE-FT across varying corpus sizes.

More on tables

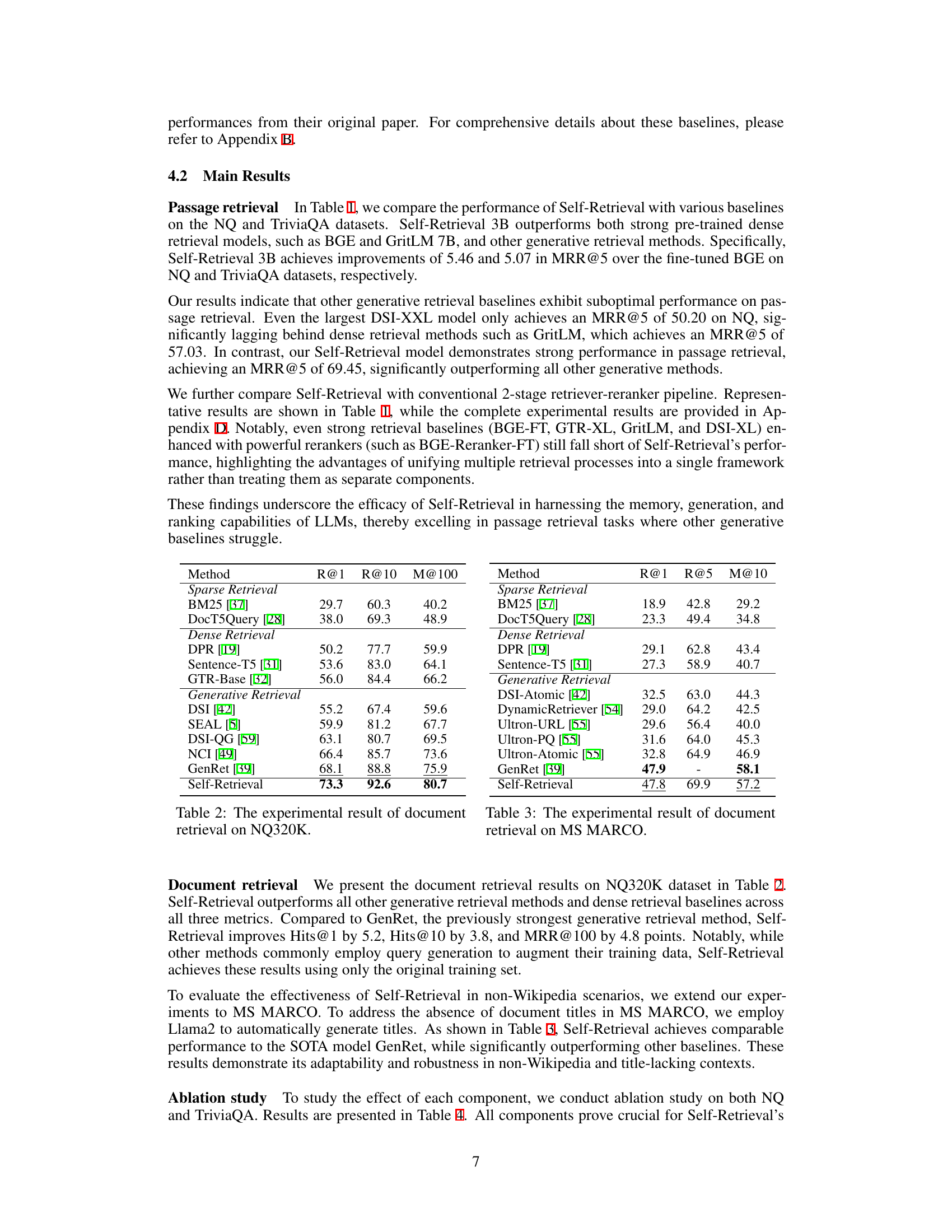

🔼 This table presents the experimental results for document retrieval on the NQ320K dataset. It compares the performance of Self-Retrieval against various baselines, including sparse retrieval methods (BM25, DocT5Query), dense retrieval methods (DPR, Sentence-T5, GTR-Base), and generative retrieval methods (DSI, SEAL, DSI-QG, NCI, GenRet). The results are measured using Recall@1, Recall@10, and MRR@100.

read the caption

Table 2: The experimental result of document retrieval on NQ320K.

🔼 This table presents the results of document-level retrieval experiments on the NQ320K dataset. It compares the performance of Self-Retrieval against several baseline methods, including sparse retrieval techniques (BM25, DocT5Query), dense retrieval techniques (DPR, Sentence-T5, GTR-Base), and other generative retrieval methods (DSI-Atomic, DynamicRetriever, Ultron variants, GenRet). The metrics used for evaluation are Recall@1, Recall@10, and Mean Average Precision@100 (MAP@100). The table demonstrates Self-Retrieval’s competitive performance compared to state-of-the-art methods.

read the caption

Table 2: The experimental result of document retrieval on NQ320K.

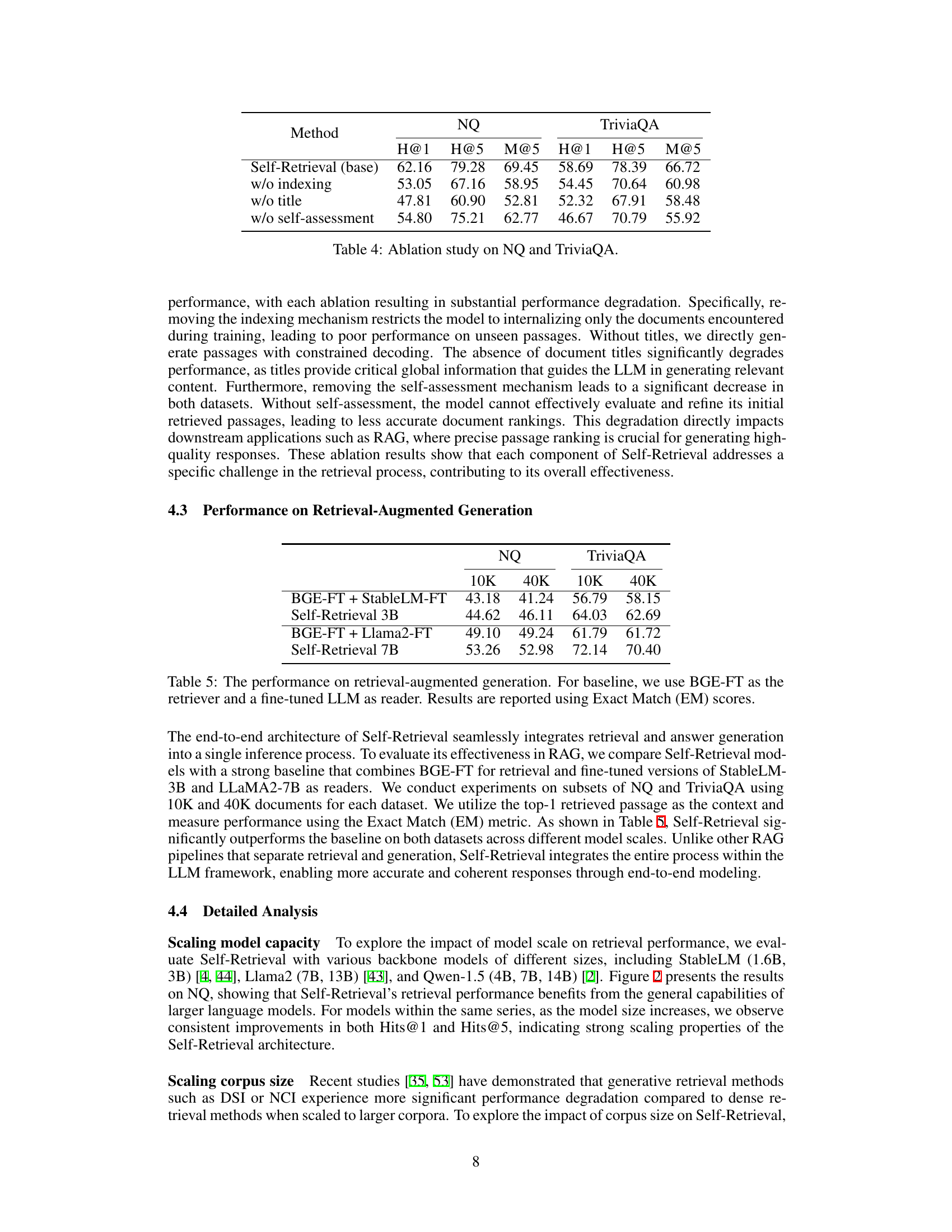

🔼 This table presents the ablation study results on the Natural Questions (NQ) and TriviaQA datasets. It shows the performance of Self-Retrieval model when different components (indexing, title generation, and self-assessment) are removed. The results demonstrate the importance of each component for the overall performance of the Self-Retrieval model.

read the caption

Table 4: Ablation study on NQ and TriviaQA.

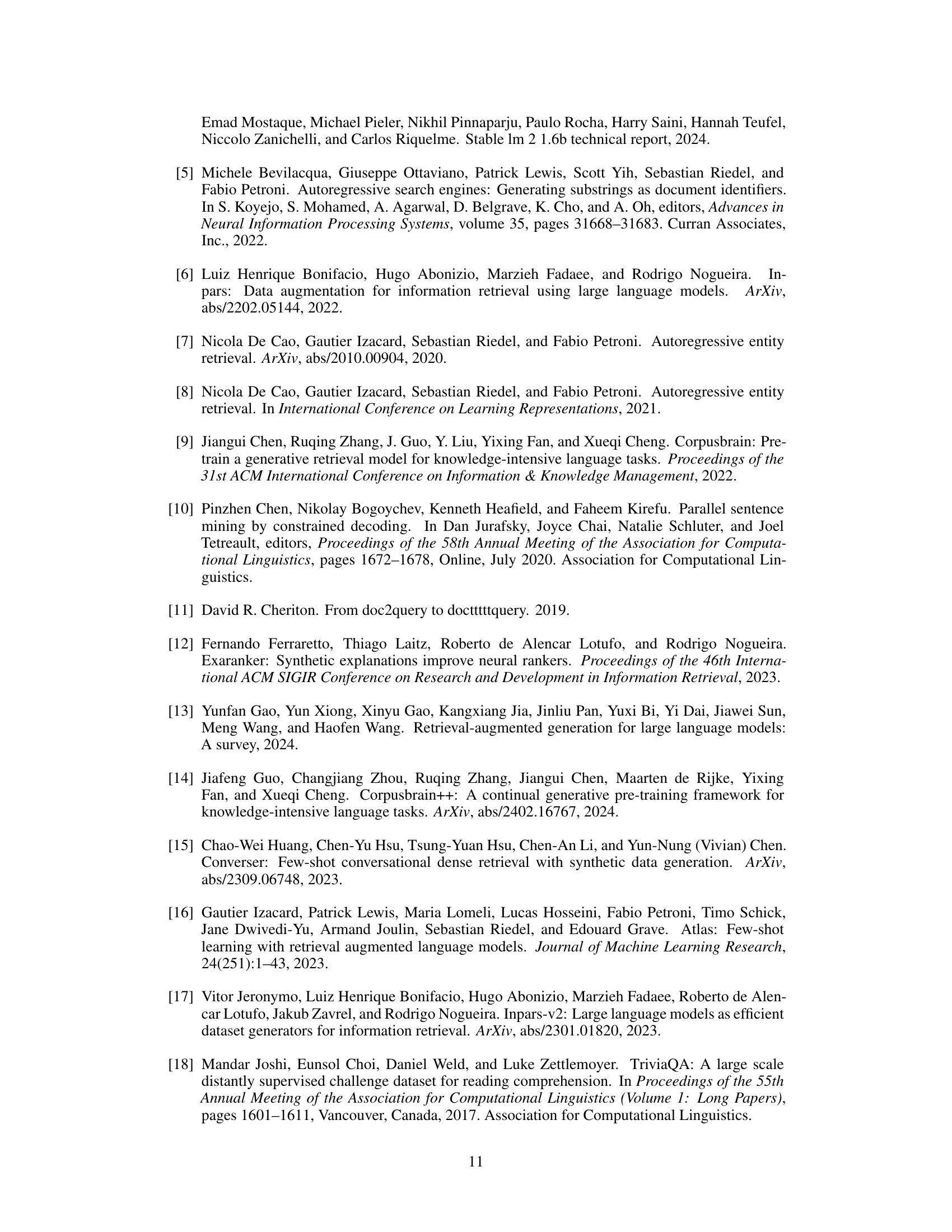

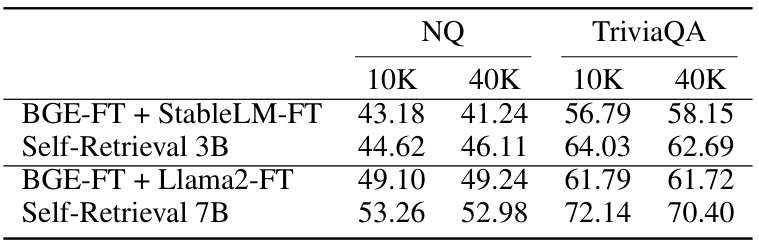

🔼 This table compares the performance of Self-Retrieval with a strong baseline on retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) tasks. The baseline uses BGE-FT for retrieval and a fine-tuned LLM as a reader. Self-Retrieval shows significantly better performance across different model sizes (3B and 7B) and dataset sizes (10K and 40K documents). The results highlight the benefits of Self-Retrieval’s unified architecture for RAG.

read the caption

Table 5: The performance on retrieval-augmented generation. For baseline, we use BGE-FT as the retriever and a fine-tuned LLM as reader. Results are reported using Exact Match (EM) scores.

🔼 This table presents the performance of Self-Retrieval and various baseline models on two datasets, Natural Questions (NQ) and TriviaQA, for passage retrieval task. The results are measured using Hits@1, Hits@5, and Mean Average Precision@5 (MAP@5) metrics. The table highlights Self-Retrieval’s superior performance compared to existing state-of-the-art approaches, with statistically significant improvements marked by asterisks.

read the caption

Table 1: The experimental results of passage retrieval on NQ and TriviaQA test set. * indicates statistically significant improvements (p < 0.01) over state-of-the-art retrieval baselines.

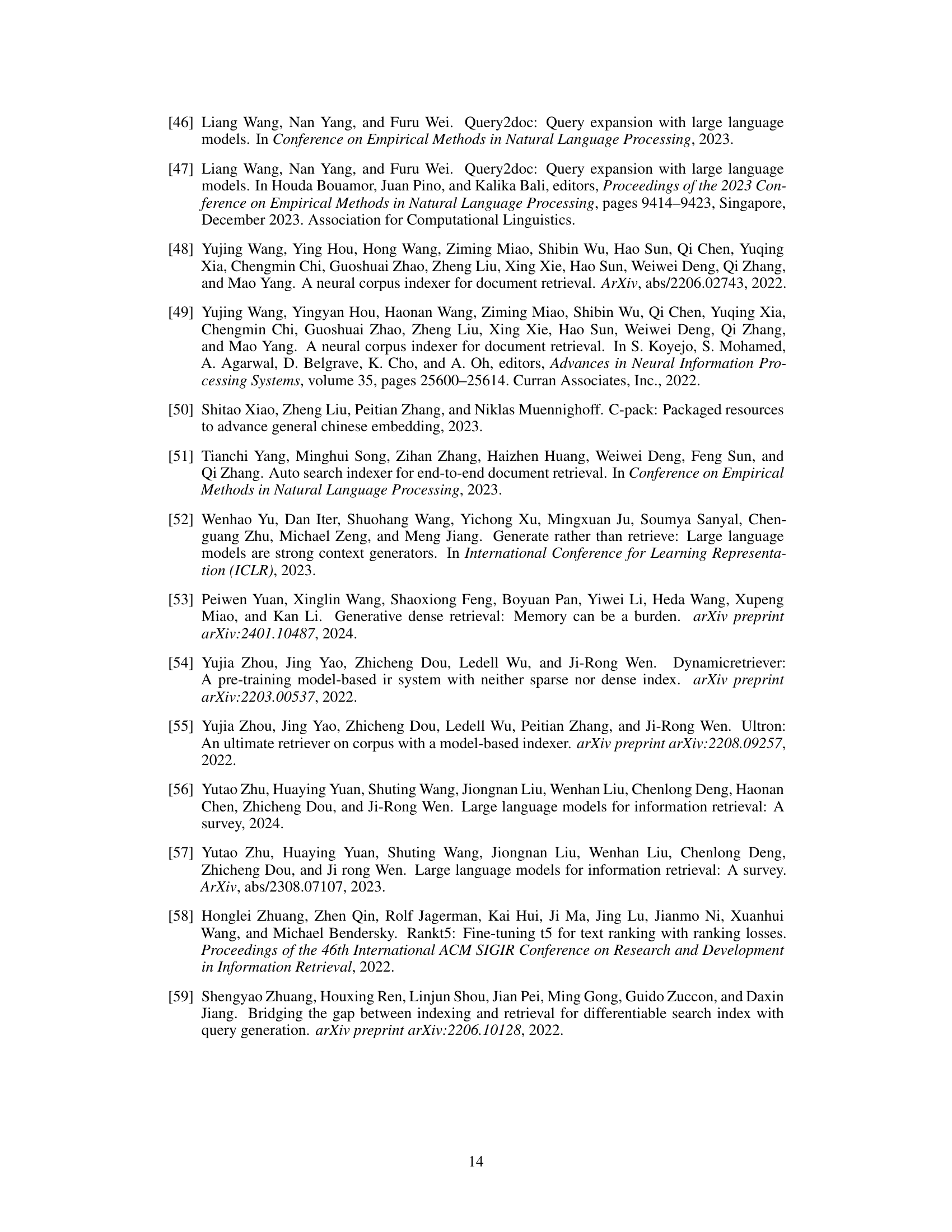

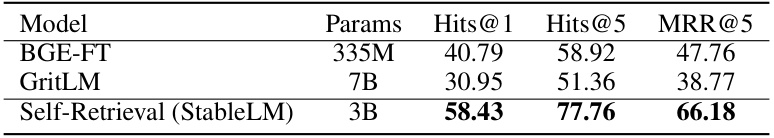

🔼 This table presents the results of retrieval experiments conducted using a chunk size of 100 words instead of the standard 200 words used in the main experiments. It compares the performance of Self-Retrieval (StableLM 3B) against BGE-FT and GritLM, demonstrating the robustness of Self-Retrieval’s performance regardless of the chunk size used.

read the caption

Table 7: Retrieval performance with chunk length of 100 words.

🔼 This table presents the performance comparison of Self-Retrieval with various baselines on two datasets, NQ and TriviaQA, for passage retrieval task. It includes the Hits@1, Hits@5, and Mean Average Precision@5 (MAP@5) metrics for each model. The models are categorized into Sparse Retrieval, Dense Retrieval, and Generative Retrieval. The Self-Retrieval model is shown to significantly outperform other models on both datasets.

read the caption

Table 1: The experimental results of passage retrieval on NQ and TriviaQA test set. * indicates statistically significant improvements (p < 0.01) over state-of-the-art retrieval baselines.

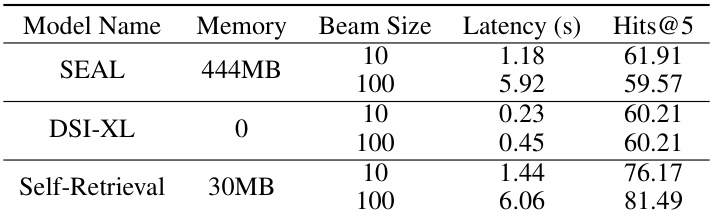

🔼 This table presents the efficiency analysis conducted on the NQ dataset using an NVIDIA A100-80G GPU. It compares Self-Retrieval against SEAL and DSI-XL across different beam sizes (10 and 100), reporting memory usage, latency, and Hits@5. The results show that while Self-Retrieval has slightly higher latency and memory usage compared to DSI-XL, it achieves significantly better performance (Hits@5) with a beam size of 10, demonstrating a good trade-off between efficiency and performance. Additionally, compared to SEAL, Self-Retrieval boasts much lower memory usage, highlighting its efficiency.

read the caption

Table 9: Efficiency analysis.

Full paper#