TL;DR#

Data privacy regulations necessitate the ability to remove data’s influence on trained machine learning models efficiently. Existing methods, like retraining, are computationally expensive. Approximate unlearning offers a compromise, aiming for a model similar to one retrained from scratch after data removal, but with lower computational cost. However, most existing approximate unlearning techniques either lack formal guarantees or are limited to full-batch settings, hindering their practicality.

This research addresses these limitations by proposing a novel unlearning approach. They leverage projected noisy stochastic gradient descent (PNSGD) and establish its first approximate unlearning guarantee under the convexity assumption. The method supports both mini-batch and sequential unlearning, showing significant computational savings compared to retraining in experiments. Their results showcase improved privacy-utility-complexity trade-offs, especially for mini-batch settings.

Key Takeaways#

Why does it matter?#

This paper is crucial for researchers in machine learning and data privacy. It offers a novel and efficient approach to machine unlearning, addressing a critical challenge in complying with data privacy regulations. The rigorous theoretical analysis and empirical results provide strong evidence for the method’s effectiveness and open up new avenues for research in privacy-preserving machine learning techniques. The mini-batch strategy significantly improves computational efficiency, making this approach practical for large datasets.

Visual Insights#

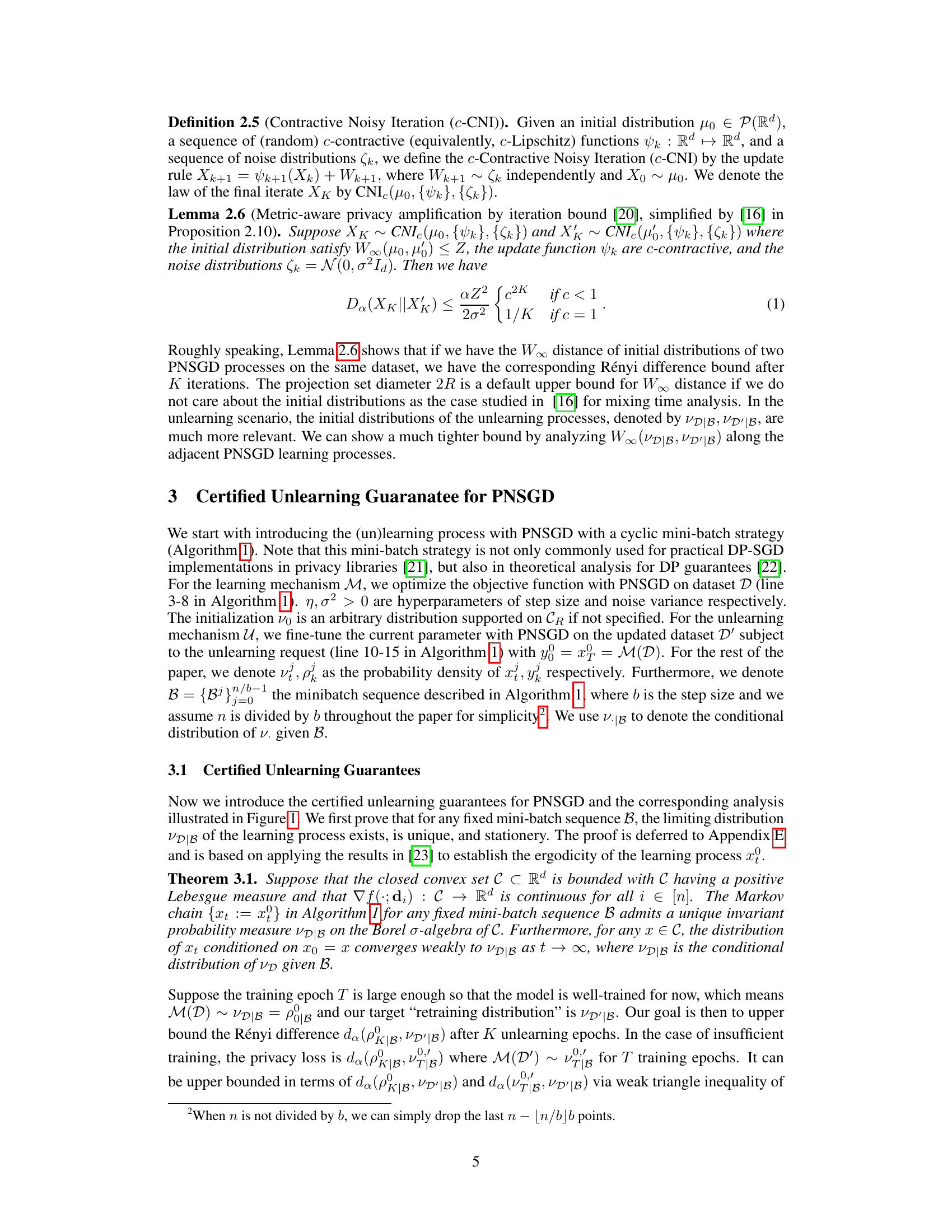

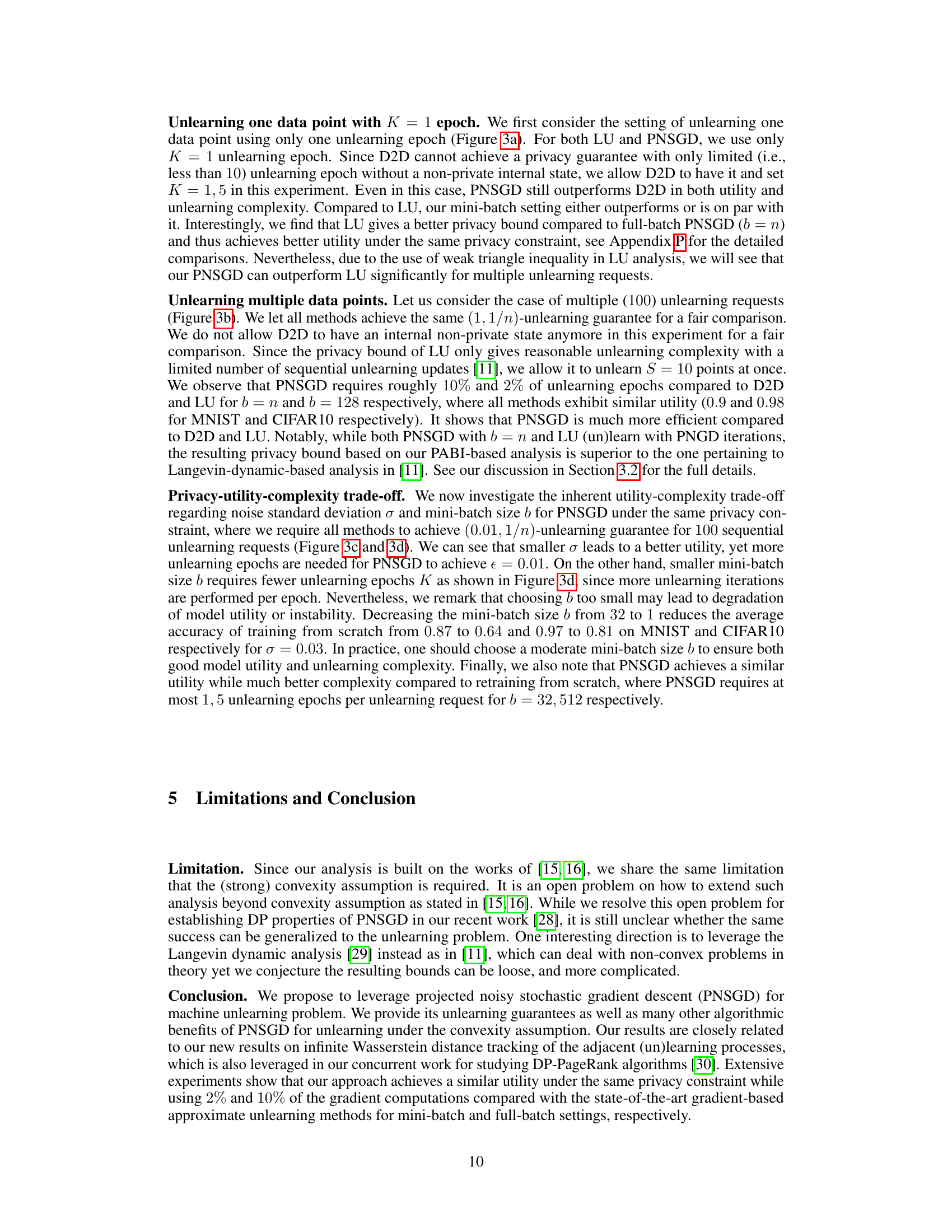

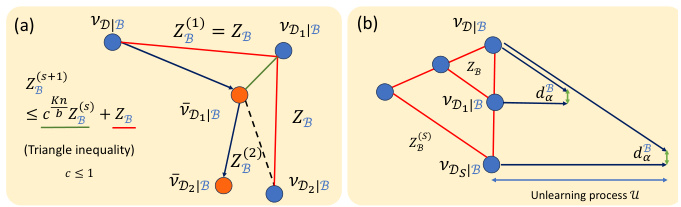

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed PNSGD unlearning framework. The left panel shows a proof sketch outlining the steps involved in establishing unlearning guarantees. The right panel visually represents the (un)learning processes using adjacent datasets (datasets differing by a single data point). It highlights the concept of using the Wasserstein distance between distributions to bound the privacy loss and how the framework handles both learning and unlearning using the same algorithm (PNSGD).

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of PNSGD unlearning. (Left) Proof sketch for PNSGD unlearning guarantees. (Right) PNSGD (un)learning processes on adjacent datasets. Given a mini-batch sequence B, the learning process M induces a regular polyhedron where each vertex corresponds to a stationary distribution VDB for each dataset D. VD|B and VD|B' are adjacent if D, D' differ in one data point. We provide an upper bound ZB for the infinite Wasserstein distance W∞(VD|B, VD'|B'), which is crucial for non-vacuous unlearning guarantees. Results of [16] allow us to convert the initial W∞ bound to Rényi difference bound db, and apply joint convexity of KL divergence to obtain the final privacy loss ɛ, which also take the randomness of B into account.

🔼 This table presents the values for the smoothness constant (L), strongly convex constant (m), Lipschitz constant (M), and RDP constant (δ) for both the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. These constants are crucial for the theoretical analysis of the unlearning guarantees in the paper. The gradient clipping value (M) is also specified.

read the caption

Table 1: The constants for the loss function and other calculation on MNIST and CIFAR-10.

In-depth insights#

Noisy SGD Unlearning#

The concept of ‘Noisy SGD Unlearning’ blends two powerful ideas: stochastic gradient descent (SGD), a cornerstone of modern machine learning, and the principle of noise addition for privacy preservation. SGD’s iterative nature allows for efficient model updates, making it ideal for machine unlearning tasks where the goal is to remove the influence of specific data points. However, directly removing data points from a trained model can reveal sensitive information about those points, hence the addition of noise. By carefully injecting calibrated noise into the SGD updates during the unlearning phase, we can mitigate the risk of data leakage while still achieving reasonably accurate model updates. The noise is crucial in maintaining a level of plausible deniability about which specific data was removed. The effectiveness of this method depends heavily on balancing two factors: the magnitude of the noise (too much noise can overwhelm the unlearning signal) and the complexity of the unlearning process (more complex processes generally require more iterations, increasing the risk of noise accumulation). Thus, a theoretical analysis is essential in determining the right balance for optimal unlearning guarantees. This approach offers a practical solution for situations where privacy is paramount, but it requires careful tuning and analysis.

Mini-batch Analysis#

Mini-batch analysis in machine unlearning is crucial for balancing privacy, utility, and computational efficiency. Smaller mini-batches enhance privacy by increasing the noise inherent in stochastic gradient descent, but this comes at the cost of increased variance and potential instability. Conversely, larger mini-batches reduce variance, improve convergence, and offer computational advantages by requiring fewer gradient computations. The optimal mini-batch size represents a trade-off, and theoretical analysis is vital for characterizing this relationship and providing practical guidance. The analysis should not only establish privacy guarantees (e.g., via Rényi divergence), but also quantify how the choice of mini-batch size impacts utility (model accuracy) and the complexity of model updates. The interaction between the strong convexity assumption of the objective function, the gradient norm, and the step size are essential aspects that need careful consideration when devising such theoretical bounds. Ultimately, the ideal mini-batch strategy will depend on the specific application and the relative priorities assigned to privacy, utility, and computational cost.

Privacy Amplification#

Privacy amplification, in the context of differential privacy, is a crucial technique to enhance the privacy offered by a mechanism. It leverages the fact that applying a differentially private algorithm multiple times does not simply linearly increase the privacy loss. Instead, under certain conditions, the privacy loss can increase sublinearly or even remain effectively constant, leading to a significant improvement in overall privacy. The core idea lies in analyzing the composition of multiple differentially private mechanisms. By carefully considering how the noise injected at each step interacts, sophisticated bounds can be derived that are tighter than naive composition bounds. Common techniques for privacy amplification focus on the properties of the underlying noise distribution and the structure of the data, with methods like Rényi Differential Privacy (RDP) offering refined composition theorems. The choice of privacy metric also plays a significant role, and the trade-offs between different metrics must be carefully evaluated, balancing the mathematical rigor with the practical implications for privacy. Ultimately, privacy amplification is essential for designing privacy-preserving machine learning algorithms that can operate on massive datasets while maintaining strong privacy guarantees.

Convexity Assumption#

The reliance on the convexity assumption is a critical limitation of the presented machine unlearning framework. While enabling elegant theoretical analysis and proving strong unlearning guarantees, this assumption significantly restricts the applicability of the method. Many real-world machine learning problems involve non-convex loss landscapes, rendering the framework unsuitable for these common scenarios. The authors acknowledge this limitation, suggesting the exploration of alternative analytical techniques (like Langevin dynamics) to address non-convexity as a direction for future work. However, it is important to note that extending the theoretical results to non-convex settings is a challenging and non-trivial task. Alternative approaches that relax or bypass the convexity assumption should be investigated to broaden the impact and practical usability of the proposed machine unlearning method. The consequences of violating the convexity assumption are not fully explored, leaving open questions regarding the robustness and performance of the method on real-world, non-convex datasets. Furthermore, future research could focus on developing methods to detect when the convexity assumption is violated and propose appropriate adaptations or fallback mechanisms for these cases.

Future Work#

This research paper on certified machine unlearning via noisy stochastic gradient descent presents a promising approach with strong theoretical guarantees under convexity assumptions. Future work could focus on relaxing the strong convexity assumption, which is a significant limitation, and exploring its applicability to non-convex problems, a common scenario in deep learning. Extending the analysis to more general mini-batch sampling strategies beyond the cyclic one used in this study would be valuable, potentially enhancing practical applicability and performance. Investigating the empirical performance with increasingly large-scale datasets is critical, as theoretical guarantees might not fully translate to real-world scenarios. Furthermore, a comprehensive study of the privacy-utility-complexity trade-off in different settings is needed to understand the practical implications and optimal parameter choices. Finally, exploring the feasibility and efficiency of adapting the proposed algorithm for sequential unlearning scenarios where requests arrive dynamically is vital for practical use, as is the exploration of handling batch updates efficiently and investigating the algorithm’s behavior in adversarial settings.

More visual insights#

More on figures

🔼 This figure illustrates the proposed PNSGD unlearning framework. The left panel shows a proof sketch, highlighting key steps: the convergence of the learning process to a stationary distribution, the bounding of the initial Wasserstein distance between adjacent distributions, the conversion of this distance to a Rényi divergence bound using results from [16], and finally, the calculation of the overall privacy loss. The right panel visually depicts the (un)learning processes as movements between adjacent vertices of a polyhedron, each vertex representing a stationary distribution for a specific dataset. The distance between these vertices, bounded by ZB, is critical to the unlearning guarantee.

read the caption

Figure 1: The overview of PNSGD unlearning. (Left) Proof sketch for PNSGD unlearning guarantees. (Right) PNSGD (un)learning processes on adjacent datasets. Given a mini-batch sequence B, the learning process M induces a regular polyhedron where each vertex corresponds to a stationary distribution VD|B for each dataset D. VD|B and VD'|B are adjacent if D, D' differ in one data point. We provide an upper bound ZB for the infinite Wasserstein distance W∞(VD|B, VD'|B), which is crucial for non-vacuous unlearning guarantees. Results of [16] allow us to convert the initial W∞ bound to Rényi difference bound dB, and apply joint convexity of KL divergence to obtain the final privacy loss ε, which also take the randomness of B into account.

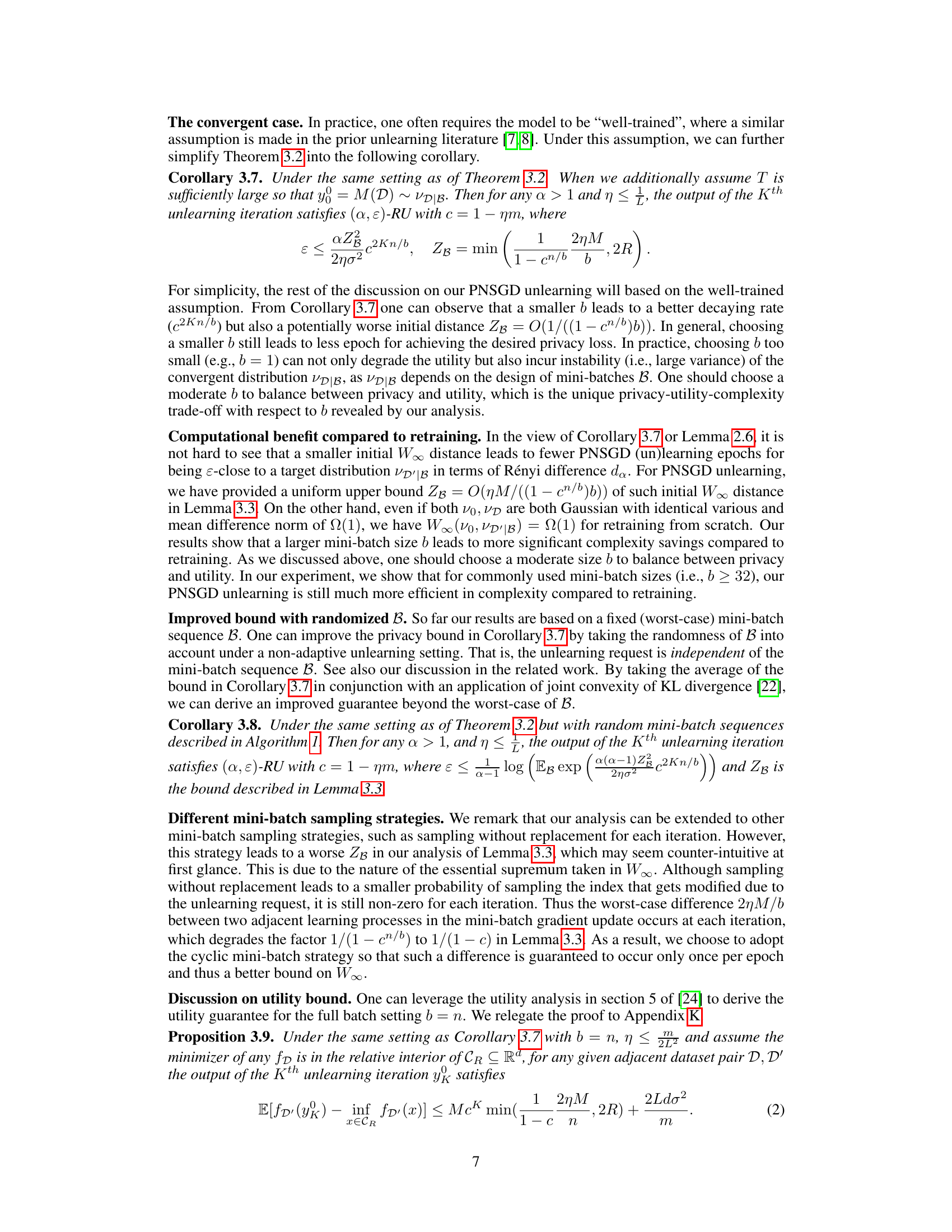

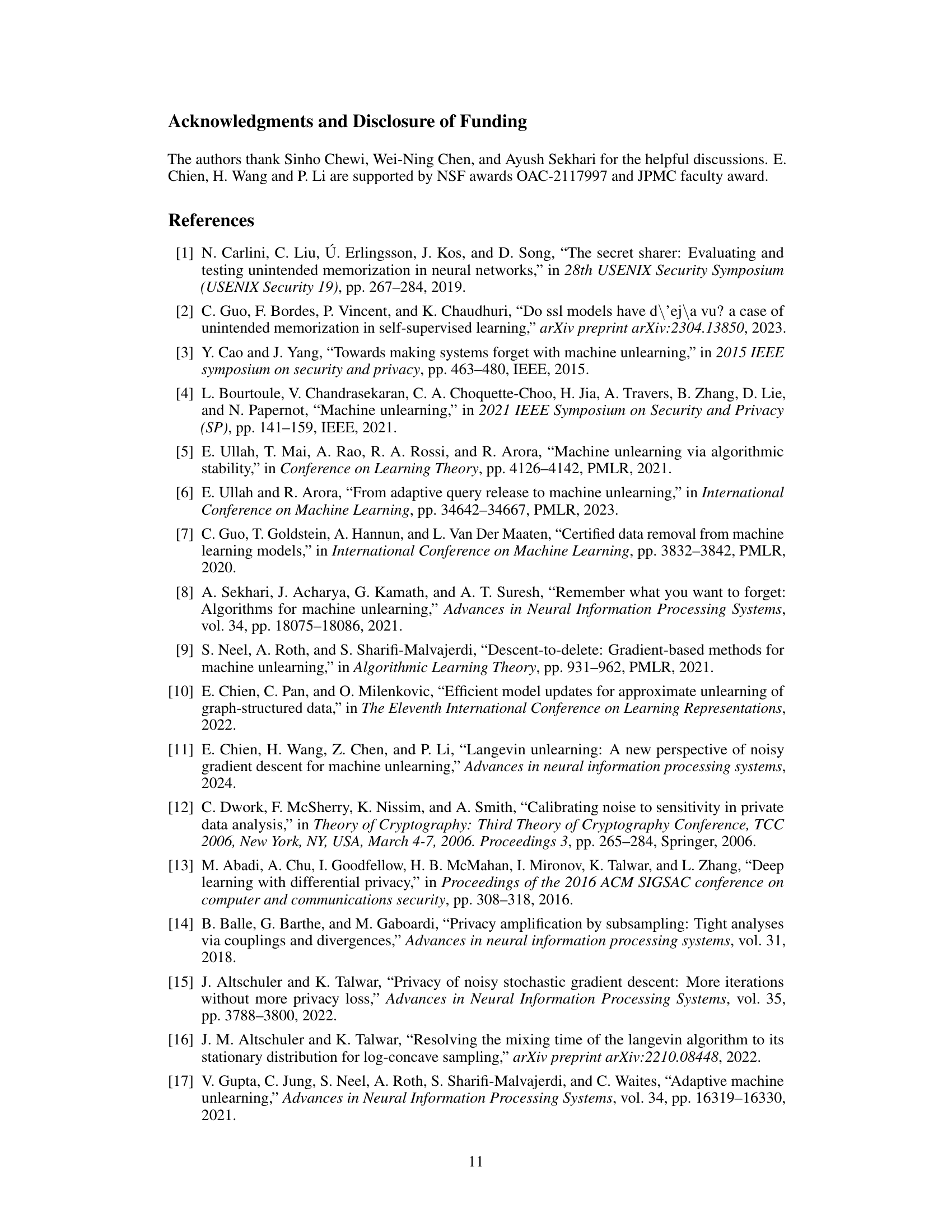

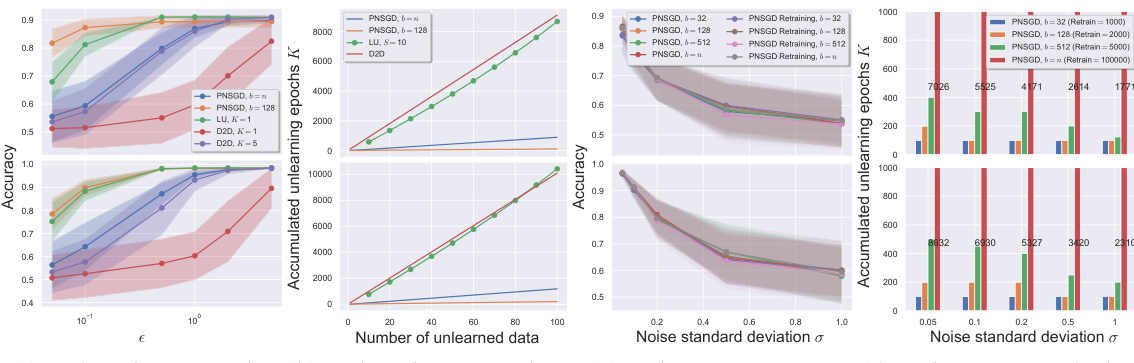

🔼 This figure presents the main experimental results comparing the proposed PNSGD method against existing baselines (D2D and LU) on MNIST and CIFAR10 datasets. It showcases the performance of each method in several scenarios: unlearning a single data point, unlearning multiple data points sequentially, and exploring the trade-off between noise level, accuracy, and computational complexity. The results highlight the efficiency and efficacy of the PNSGD approach, particularly in the context of multiple sequential unlearning requests.

read the caption

Figure 3: Main experiments, where the top and bottom rows are for MNIST and CIFAR10 respectively. (a) Compare to baseline for unlearning one point using limited K unlearning epoch. For PNSGD, we use only K = 1 unlearning epoch. For D2D, we allow it to use K = 1,5 unlearning epochs. (b) Unlearning 100 points sequentially versus baseline. For LU, since their unlearning complexity only stays in a reasonable range when combined with batch unlearning of size S sufficiently large, we report such a result only. (c,d) Noise-accuracy-complexity trade-off of PNSGD for unlearning 100 points sequentially with various mini-batch sizes b, where all methods achieve (ε, 1/n)-unlearning guarantee with ε = 0.01. We also report the required accumulated epochs for retraining for each b.

More on tables

🔼 This table shows the number of burn-in steps (T) used for training the model before unlearning begins, for various mini-batch sizes (b) within the PNSGD unlearning framework. The burn-in period allows the model to converge to a stable state before unlearning commences.

read the caption

Table 2: The Burn-in step T set for different batch sizes for the PNSGD unlearning framework

🔼 This table presents the values of several key constants used in the calculations and experiments in the paper. These constants are related to the properties of the loss function, including its smoothness, strong convexity, and Lipschitz continuity. The values are listed separately for the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets, indicating that these properties may differ depending on the dataset. Gradient clipping is also included with the corresponding value. These values are crucial for setting hyperparameters in the proposed algorithms and for the theoretical analysis of their performance.

read the caption

Table 1: The constants for the loss function and other calculation on MNIST and CIFAR-10.

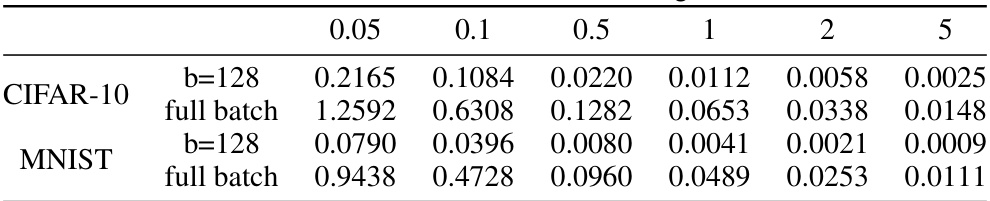

🔼 This table presents the noise standard deviation (σ) values obtained through a binary search for the PNSGD unlearning method. Different values are shown for various mini-batch sizes (b = 32, 128, 512, and full batch) on both the CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets. These σ values are calculated to ensure the algorithm achieves a specified privacy level (€, δ)-unlearning with different target privacy loss (€).

read the caption

Table 3: σ of PNSGD unlearning.

🔼 This table shows the noise standard deviation (σ) values used for the PNSGD unlearning method in experiments with different privacy loss targets (ϵ) and mini-batch sizes (b) for MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. The values were obtained via a binary search to find the smallest σ that satisfies the desired ϵ for a given K.

read the caption

Table 3: σ of PNSGD unlearning.

🔼 This table shows the values of the noise standard deviation (σ) used in the PNSGD unlearning experiments for different target privacy levels (ê) and mini-batch sizes (b) on the MNIST and CIFAR-10 datasets. The results are obtained through a binary search algorithm, finding the smallest σ that satisfies the specified privacy guarantee (ê) and unlearning step budget (K).

read the caption

Table 3: σ of PNSGD unlearning.

🔼 This table shows the noise standard deviation (σ) values obtained using a binary search algorithm for different privacy loss targets (ê) and mini-batch sizes (b), for both the CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets. The values represent the smallest σ required to achieve the target privacy loss within a given number of unlearning steps (K). Full batch refers to the case where b = n (the number of data points).

read the caption

Table 3: σ of PNSGD unlearning.

🔼 This table presents the noise standard deviation (σ) values obtained for the PNSGD unlearning method using a binary search algorithm. The values are shown for different mini-batch sizes (b) and target privacy loss levels (ê) on both the CIFAR-10 and MNIST datasets. The table aids in understanding the privacy-utility trade-off; smaller σ values improve utility but require more unlearning epochs to achieve the specified privacy guarantee.

read the caption

Table 3: σ of PNSGD unlearning.

Full paper#